Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

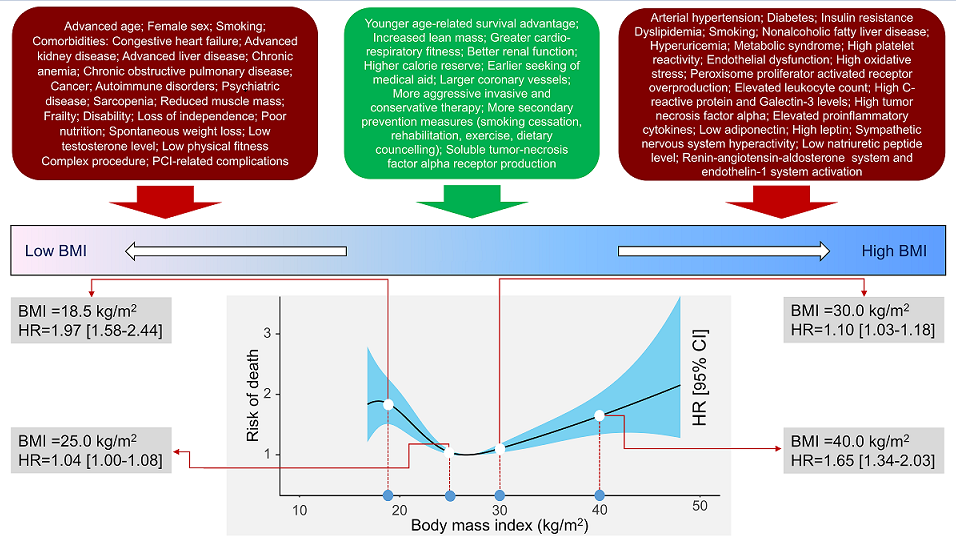

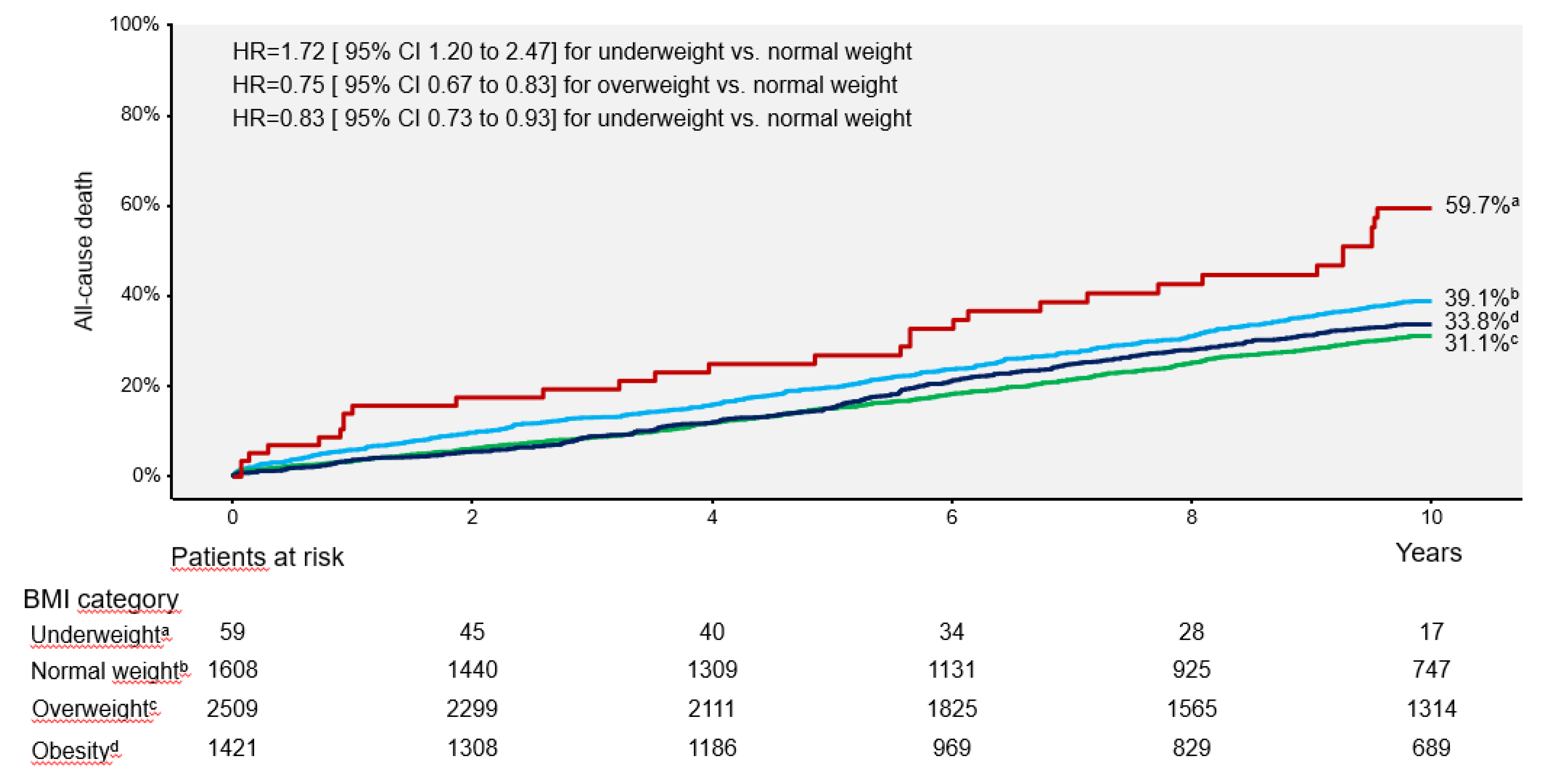

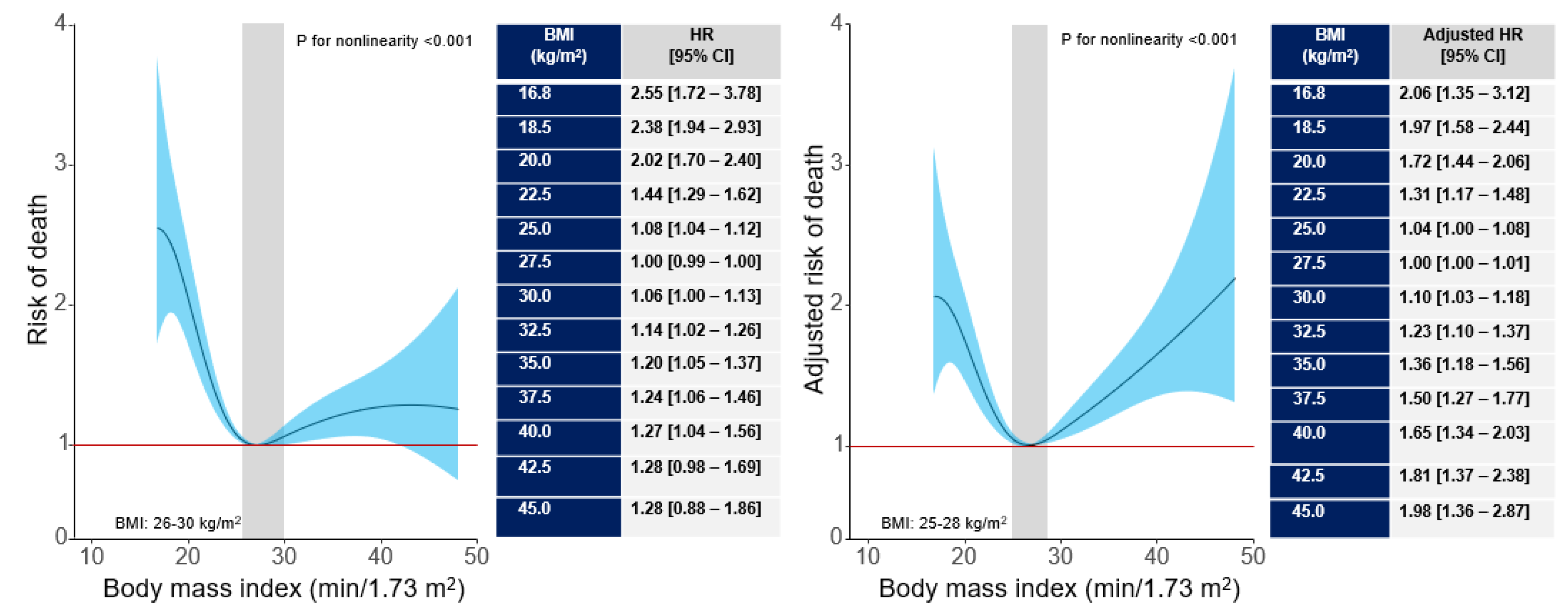

Background and Aims: The association between body mass index (BMI) and long-term outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains poorly inves-tigated. We undertook this study to assess the association between BMI and 10-year out-come after PCI. Methods and Results: This study included 5597 patients with coronary artery disease undergoing PCI. Patients were categorized according to BMI values: un-derweight group (BMI <18.5 kg/m2), normal weight group (BMI between 18.5 kg/m2 and <25 kg/m2), overweight group (BMI between 25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2) and obesity group (BMI ≥30 kg/m2). The primary outcome was 10-year all-cause mortality. At 10 years, deaths of any cause (primary endpoint) occurred in 1754 patients: 31 deaths in the under-weight group (59.7%), 582 deaths (39.1%) in the normal weight group, 710 deaths (31.1%) in the overweight group and 431 deaths (33.8%) in the obesity group (overall P value <0.001; P for nonlinearity <0.001). Nonsurvivors had a significantly lower BMI compared with survivors (26.5 [24.2-29.9] kg/m2 vs. 27.2 [24.8-30.1] kg/m2, P<0.001). Interaction test-ing showed a BMI-by-age interaction demonstrating a stronger association between higher BMI (≥25 kg/m2) and reduced risk of all-cause mortality in patients ≥75 years of age (Pint = 0.009). The association between BMI and all-cause mortality was U-shaped (P for nonlinearity<0.001). C-statistic of the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model for mortality increased from 0.762 [0.751-0.773] with baselines variables only to 0.766 [0.756-0.777], P<0.001) after inclusion of BMI in the model (baseline variables plus BMI). Conclu-sions BMI was associated with 10-year mortality after PCI with a U-shaped relationship.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Study Definitions and Measurements

2.3. Outcomes and Follow-Up

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

3.2. Clinical Outcome

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2023. https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=19. Accessed on August 2th, 2024.

- Afshin, A.; Reitsma, M.B.; Murray, C.J.L. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1496–1497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Formentini, F.S.; Zaina Nagano, F.E.; Lopes Neto, F.D.N.; Adam, E.L.; Fortes, F.S.; Silva, L.F.D. Coronary artery disease and body mass index: What is the relationship? Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 34, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.S.; Ning, H.; Wilkins, J.T.; Allen, N.; Carnethon, M.; Berry, J.D.; et al. Association of Body Mass Index With Lifetime Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Compression of Morbidity. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, R.P.; Bemelmans, W.J.; Hoogenveen, R.T.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Woodward, M.; Knekt, P.; et al. Association of overweight with increased risk of coronary heart disease partly independent of blood pressure and cholesterol levels: a meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies including more than 300 000 persons. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Despres, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Gallo, G. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: An executive document on pathophysiological and clinical links promoted by the Italian Society of Cardiovascular Prevention (SIPREC). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1136340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruberg, L.; Weissman, N.J.; Waksman, R.; Fuchs, S.; Deible, R.; Pinnow, E.E.; et al. The impact of obesity on the short-term and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: the obesity paradox? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, T.; Forhan, M.; Norris, C.M.; Qiu, W.; Padwal, R.; Sharma, A.M.; et al. Differences in Short- and Long-Term Mortality Associated With BMI Following Coronary Revascularization. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.Q.; Sun, X.J.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.Q.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, N.F. Does body mass index truly affect mortality and cardiovascular outcomes in patients after coronary revascularization with percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufner, S.; Joner, M.; Thannheimer, A.; Hoppmann, P.; Ibrahim, T.; Mayer, K.; et al. Ten-Year Clinical Outcomes From a Trial of Three Limus-Eluting Stents With Different Polymer Coatings in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation 2019, 139, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kufner, S.; Ernst, M.; Cassese, S.; Joner, M.; Mayer, K.; Colleran, R.; et al. 10-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Trial of Polymer-Free Versus Durable Polymer Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutlip, D.E.; Windecker, S.; Mehran, R.; Boam, A.; Cohen, D.J.; van Es, G.A.; et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation 2007, 115, 2344–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, Joint ESCAAHAWHFTFftRoMI. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 2525–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vallakati, A.; Einstein, A.J.; Lavie, C.J.; Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; et al. Relationship of body mass index with total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: evidence from a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.G.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, B.K.; Ahn, C.M.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Association between body mass index and clinical outcomes after new-generation drug-eluting stent implantation: Korean multi-center registry data. Atherosclerosis 2018, 277, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, E.W.; Sirker, A.; Kwok, C.S.; Kontopantelis, E.; Ludman, P.F.; De Belder, M.A.; et al. The Relationship of Body Mass Index to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Outcomes: Does the Obesity Paradox Exist in Contemporary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Cohorts? Insights From the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.; Hu, S.; Mi, L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, T. Body mass index and all-cause mortality in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: A dose-response meta-analysis of obesity paradox. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuge, M.; Kimura, K.; Kojima, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Ishihara, M.; Asada, Y.; et al. Impact of body mass index on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Circ. J. 2008, 72, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, H.; Dohi, T.; Shitara, J.; Wada, H.; Doi, S.; Naito, R.; et al. Impact of body mass index on long-term outcomes in Japanese patients following percutaneous coronary intervention: The Juntendo PCI Registry. J. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahim, B.; Redfors, B.; Chen, S.; Thiele, H.; Eitel, I.; Gkargkoulas, F.; et al. BMI, Infarct Size, and Clinical Outcomes Following Primary PCI: Patient-Level Analysis From 6 Randomized Trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.; Zhong, Q.; Wu, R.; Li, Z.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Impact of body mass index on long-term outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention stratified by diabetes mellitus: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndrepepa, G.; Keta, D.; Byrne, R.A.; Schulz, S.; Mehilli, J.; Seyfarth, M.; et al. Impact of body mass index on clinical outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels. 2010, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witassek, F.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Erne, P.; Radovanovic, D. Impact of Body Mass Index on mortality in Swiss hospital patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: does an obesity paradox exist? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2014, 144, w13986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaly, S.; Redfors, B.; Omerovic, E.; Carlsson, L.; Karason, K. Prognostic significance of BMI after PCI treatment in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a cohort study from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. Open Heart 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzeri, C.; Valente, S.; Chiostri, M.; Attana, P.; Picariello, C.; Sorini Dini, C.; et al. Impact of age on the prognostic value of body mass index in ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahli, B.E.; Gebhard, C.; Gick, M.; Herman, C.; Ferenc, M.; Mashayekhi, K.; et al. Impact of body mass index on long-term mortality in women and men undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusion. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 224, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younge, J.O.; Damen, N.L.; van Domburg, R.T.; Pedersen, S.S. Obesity, health status, and 7-year mortality in percutaneous coronary intervention: in search of an explanation for the obesity paradox. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, R.; Maehara, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Mintz, G.S.; Redfors, B.; et al. The obesity paradox revisited: body mass index and -long-term outcomes after PCI from a large pooled patient-level database. EuroIntervention 2020, 15, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanic, V.; Suran, D. Sex differences in the relationship between body mass index and outcome in myocardial infarction. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 366, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscarella, E.; Spitaleri, G.; Brugaletta, S.; Senti Farrarons, S.; Pernigotti, A.; Ortega-Paz, L.; et al. Impact of Body Mass Index on 5-Year Clinical Outcomes in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction After Everolimus-Eluting or Bare-Metal Stent Implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 120, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiegelow, M.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Gislason, G.H.; Andersson, C.; Lyngbaek, S.; Pedersen, S.; et al. Relation of body mass index to risk of stent thrombosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 1592–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarno, G.; Raber, L.; Onuma, Y.; Garg, S.; Brugaletta, S.; van Domburg, R.T.; et al. Impact of body mass index on the five-year outcome of patients having percutaneous coronary interventions with drug-eluting stents. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, I.; Tolg, R.; Hochadel, M.; Bergmann, M.W.; Khattab, A.A.; Schneider, S.; et al. No evidence of “obesity paradox” after treatment with drug-eluting stents in a routine clinical practice: results from the prospective multicenter German DES.DE (German Drug-Eluting Stent) Registry. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 5, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamminen, M.; Lassila, R.; Westerbacka, J.; Vehkavaara, S.; Yki-Jarvinen, H. Obesity is associated with impaired platelet-inhibitory effect of acetylsalicylic acid in nondiabetic subjects. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2003, 27, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, G.; Koltai, K.; Alkonyi, B.; Papp, E.; Keszthelyi, Z.; Kesmarky, G.; et al. Clopidogrel resistance: role of body mass and concomitant medications. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007, 120, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirahama, Y.; Tabata, N.; Sakamoto, K.; Sato, R.; Yamanaga, K.; Fujisue, K.; et al. Validation of the obesity paradox by body mass index and waist circumference in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Int. J. Obes. 2022, 46, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Kawashima, H.; Hara, H.; O’Leary, N.; Gao, C.; Wang, R.; et al. Impact of Body Composition Indices on Ten-year Mortality After Revascularization of Complex Coronary Artery Disease (From the Syntax Extended Survival Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 151, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Body mass index (kg/m2) | P value | |||

| <18.5 (n=59) |

18.5 to <25 (n=1608) |

25 to <30 (n=2509) |

≥30 (n=1421) |

||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 17.7 [17.1–18.2] | 23.4 [22.1–24.4] | 27.3 [26.1–28.4] | 32.2 [31.0–34.6] | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 73.4 [62.5–80.1] | 70.1 [62.8–78.0] | 68.2 [60.8–74.8] | 65.6 [57.4–72.7] | <0.001 |

| Women | 35 (59.3%) | 503 (31.3%) | 466 (18.6%) | 325 (22.9%) | <0.001 |

| History of arterial hypertension | 40 (67.8%) | 1054 (65.5%) | 1688 (67.3%) | 995 (70.0%) | 0.073 |

| History of hypercholesterolemia | 32 (54.2%) | 952 (59.2%) | 1666 (66.4%) | 967 (68.1%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (15.3%) | 345 (21.5%) | 687 (27.4%) | 581 (40.9%) | <0.001 |

| On insulin therapy | 3 (5.08%) | 112 (6.97%) | 198 (7.89%) | 222 (15.6%) | <0.001 |

| On oral antidiabetic drugs | 4 (6.78%) | 176 (10.9%) | 384 (15.3%) | 261 (18.4%) | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.87 [0.78–1.00] | 0.90 [0.80–1.10] | 0.98 [0.80–1.10] | 0.94 [0.80–1.11] | <0.001 |

| Estimated GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 77.0 [58.3–91.6] | 77.5 [59.8–90.1] | 78.0 [61.6–91.6] | 80.1 [62.1–93.2] | 0.006 |

| Current smoker | 20 (33.9%) | 278 (17.3%) | 377 (15.0%) | 262 (18.4%) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 18 (30.5%) | 446 (27.7%) | 719 (28.7%) | 447 (31.5%) | 0.135 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass surgery | 4 (6.8%) | 124 (7.7%) | 267 (10.6%) | 147 (10.3%) | 0.011 |

| Diagnosis at presentation | 0.038 | ||||

| Chronic coronary disease | 36 (61.0%) | 903 (56.2%) | 1517 (60.5%) | 855 (60.2%) | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 23 (39.0%) | 705 (43.8%) | 992 (39.5%) | 566 (39.8%) | |

| Number of coronary arteries narrowed 1 2 3 |

11 (18.6%) 21 (35.6%) 27 (45.8%) |

263 (16.4%) 443 (27.5%) 902 (56.1%) |

358 (14.3%) 684 (27.3%) 1467 (58.5%) |

208 (14.6%) 350 (24.6%) 863 (60.7%) |

0.049 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 54.0 [40.5–60.0] | 56.0 [46.0–62.0] | 56.0 [48.0–62.0] | 56.0 [46.0–61.0] | 0.064 |

| Events | Body mass index (kg/m2) | Hazard ratio [95% confidence interval] | |||||

| <18.5 (n=59) |

18.5 to <25 (n=1608) |

25 to <30 (n=2509) |

≥30 (n=1421) |

<18.5 vs. 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 |

25 to <30 vs. 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 |

>30 vs. 18.5 to <25 kg/m2 |

|

| All-cause death | 31 (59.7) | 582 (39.1) | 710 (31.1) | 431 (33.8) | 1.72 [1.20–2.47] | 0.75 [0.67–0.83] | 0.83 [0.73–0.93] |

| Cardiac death | 14 (27.2) | 355 (24.3) | 441 (19.7) | 266 (21.3) | 1.15 [0.67–1.96] | 0.78 [0.68–0.90] | 0.86 [0.73–1.00] |

| Noncardiac death | 17 (32.5) | 227 (14.7) | 269 (11.4) | 165 (12.4) | 2.33 [1.44–3.76] | 0.75 [0.63–0.89] | 0.82 [0.67–1.01] |

| Myocardial infarction | 6 (10.3) | 104 (6.7) | 152 (6.3) | 75 (5.5) | 1.64 [0.72–3.73] | 0.94 [0.73–1.21] | 0.82 [0.61–1.10] |

| Definite stent thrombosis | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.4) | 28 (1.2) | 18 (1.3) | - | 2.59 [1.13–5.93] | 2.97 [1.24–7.09] |

| Target lesion revascularization | 6 (11.0) | 287 (18.6) | 449 (18.7) | 261 (19.4) | 0.56 [0.25–1.26] | 1.01 [0.87–1.18] | 1.05 [0.89–1.24] |

| Target vessel revascularization | 7 (12.7) | 326 (20.8) | 591 (24.3) | 340 (24.9) | 0.58 [0.27–1.22] | 1.19 [1.04–1.36] | 1.22 [1.05–1.42] |

| Nontarget vessel revascularization | 5 (9.2) | 393 (25.2) | 739 (30.6) | 429 (31.6) | 0.33 [0.14–0.80] | 1.25 [1.10–1.41] | 1.29 [1.12–1.48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).