Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

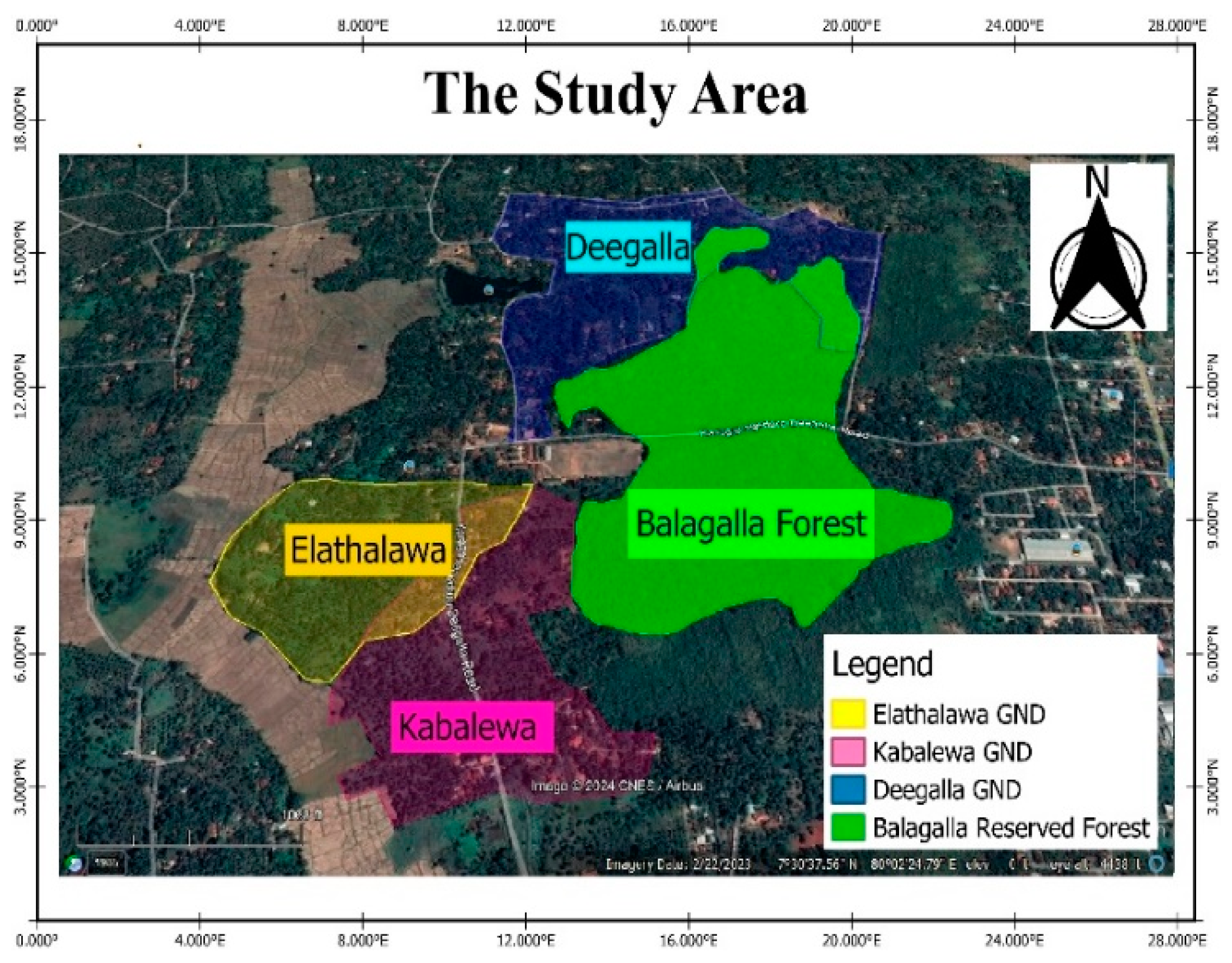

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information of the Respondents

3.2. Crop and Property Damage Caused by Macaques

3.2.1. Types of Damage

3.2.2. Seasonal and Diurnal Variation in Crop Damage

3.2.3. Economic Loss Due to Crop Damage

3.2.4. Economic Loss Inflicted on Coconuts

3.2.5. Economic Loss and the Distance to the Nearest Forest Reserve

| GND | Distance from the forest (m) |

Number of coconuts destroyed / per month during non-fruiting season | Monthly economic loss during the non-fruiting season (LKR) | Number of days macaques visited the plantation / per month during non-fruiting season |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deegalla (2 acres, 120 trees) |

30m | 105 - 220 | 13,200 | 28 |

| Kabalewa (1.5 acres, 90 trees) |

150m | 106 – 154 | 9,240 | 22 - 25 |

| Elathalawa (3 acres, 200 trees) |

200m | 36 - 60 | 3,600 | 15 - 17 |

3.2.6. Currently Used Deterrent Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GND | Gramasewa Niladari Division |

| DCS | Department of Census and Statistics |

| CBSL | Central Bank Sri Lanka |

| HMC | Human Macaque Conflict |

| LKR | Sri Lankan Rupee |

References

- Nahallage, C.A.D.; Huffman, M.A. Macaque–Human interactions in past and present day in Sri Lanka. In Macaque Connections: Corporation and Conflict Between Humans and Macaques; 2013; pp. 135–148.

- Dittus, W.P.J.; Gunathilaka, S.; Felder, M. Assessing Public Perceptions and Solutions to Human-Monkey Conflict from 50 Years in Sri Lanka. Folia Primatol. 2019, 90, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahallage, C.A.D. An ethnological perspective of Sri Lankan primates. Vidyodaya Curr. Res. 2019, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dittus, W. Problems with pest monkeys: Myths and solutions. Loris 2012, 26, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jayarathne, S.D.Y.; Nahallage, C.A.D.; Huffman, M.A. Assessing Public Perceptions toward Toque Macaques in Kuliyapitiya Divisional Secretariat to Mitigate the Human-Macaque Interactions in Sri Lanka. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2023, X, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahallage, C.A.D.; Huffman, M.A. Diurnal primates in Sri Lanka and people’s perception of them. Primate Conserv. 2008, 23, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, R. An historical relation of the island Ceylon in East-Indies; Richard Chefwell: London, UK, 1681. [Google Scholar]

- Ananda, P.A.S. Sinhala Janashruthiya Saha Sathwa Lokaya; Godage Publishers: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2000; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Fungo, B. A review of crop raiding around protected areas: Nature, control, and research gaps. Environ. Res. J. 2011, 5, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M. A conflict of interest between people and baboons: Crop raiding in Uganda. Int. J. Primatol. 2000, 21, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, T.; Cabral, S.J.; Weerakkody, S.N.; Rudran, R. Human monkey conflict in Sri Lanka and mitigation efforts. In Proceedings of the 5th Asian Primate Symp, 2016; University of Sri Jayewardenepura: Nugegoda, Sri Lanka; 2016; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, S.J.; Prasad, T.; Deeyagoda, T.P.; Weerakkody, S.N.; Nadarajah, A.; Rudran, R. Investigating Sri Lanka’s human-monkey conflict and developing a strategy to mitigate the problem. J. Threat. Taxa 2018, 10, 11391–11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahallage, C.A.D.; Dasanayake, D.A.M.; Hewamanna, D.T.; Ananda, D. Utilization of home garden crops by primates and current status of human-primate interface at Galigamuwa Divisional Secretariat Division in Kegalle District, Sri Lanka. J. Threat. Taxa 2022, 14, 20478–20487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Vandercone, R. Temporal patterns of crop raiding by diurnal primates in and around the Kaludiyapokuna Forest Reserve in the dry zone of Sri Lanka. In Proceedings of the 5th Asian Primate Symp, 2016; University of Sri Jayewardenepura: Nugegoda, Sri Lanka; 2016; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL). Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report: Prices, Wages, Employment and Productivity; Central Bank of Sri Lanka: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.M. People, crop and primates: A conflict of interest. In Commensalism and Conflict: The Human–Primate Interface; Peterson, J.D., Wallis, J., Eds.; American Society of Primatologists: Norman, Oklahoma, 2005; pp. 40–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggers, R.L.; Rodriguez, E.; Zaccagnini, M.E. Planning for bird pest problem resolution: A case study. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1998, 42, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, M.E.; Fuashi, N.A.; Mengwi, N.H.; Ebong, E.L.; Awa, P.D.; Daizy, N.F. The control methods used by the local farmers to reduce Weaver bird raids in Tiko farming area, southwest region, Cameroon. 2019.

- Lathiya, S.B.; Khokha, A.R.; Ahmed, S.M. Population Dynamics of Soft-Furred field rat, Millardia meltada, in Rice and wheat Fields in Central Punjab, Pakistan. Turk. J. Zool. 2003, 27, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, M. Pattern of damage by rodent (Rodentia: Muridae) pests in Wheat in conjunction with their comparative densities throughout growth phase of crop. Int. J. Sci. Res. Environ. Sci. 2015, 3, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkie, M.; Dinata, Y.; Nofrianto, A.; Leader-Williams, N. Patterns and perceptions of wildlife crop raiding in and around Kerinci Seblat National Park, Sumatra. Anim. Conserv. 2007, 10, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.M.; Khokhar, A.R. Some observations on wild boar (Sus scrofa) and its control in sugarcane areas of Punjab, Pakistan. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1986, 83, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gobosho, L.; Feyssab, D.H.; Gutemac, T.M. Identification of crop raiding species and the status of their impact on farmer resources in Gera, Southwestern Ethiopia. Int. J. Sci.: Basic Appl. Res. 2015, 22, 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sukumar, R. Ecology of the Asian elephant in southern India. II. Feeding habits and crop raiding patterns. J. Trop. Ecol. 1990, 6, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R. The conflict between humans and elephants in the central African forests. Mammal Rev. 1996, 26, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyo, P.I.; Moss, C.J.; Alberts, S.C. The influence of life history milestones and association networks on crop-raiding behavior in male African elephants. Social Networks 2012, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.M.; Horrocks, J.A.; Baulu, J. The Barbados vervet monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus): Changes in population size and crop damage. Int. J. Primatol. 1996, 17, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton-Treves, L.; Treves, A.; Chapman, C.; Wrangham, R. Temporal patterns of crop-raiding by primates: Linking food availability in croplands and adjacent forest. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998, 35, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.M.; Wallace, G.E. Crop protection and conflict mitigation: Reducing the costs of living alongside non-human primates. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 2569–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockings, K.J.; James, R.A.; Matsuzawa, T. Socioecological adaptations by chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, inhabiting an anthropogenically impacted habitat. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramagamage, P. Large-scale deforestation for plantation agriculture in the hill country of Sri Lanka and its impacts. Hydrol. Process. 1998, 12, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, M.E.; Fuashi, N.A.; Mengwi, N.H.; Ebong, E.L.; Awa, P.D.; Daizy, N.F. The control methods used by the local farmers to reduce Weaver bird raids in Tiko farming area, southwest region, Cameroon. 2019.

- Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behav. 1974, 49, 227–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, R.M. Evaluation of the Wildlife Crop Raiding Impact on Seasonal Crops in Five Farming Communities Adjacent to the Gola Rainforest National Park in Sierra Leone 2013–2014; Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary: Freetown, Sierra Leone, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C.M. Farmers’ perspectives of conflict at the wildlife–agriculture boundary: Some lessons learned from African subsistence farmers. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2004, 9, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Category | Sampling Method used to Select Sample Size | Sample Size of Deegalla GND | Sample Size of Kabalewa GND | Sample Size of Elathalawa GND |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Families Cultivating Commercial Crops / Farmers | Included all the farmers | 135 | 120 | 20 |

| Families Cultivating Home Garden Crops / Villagers | The Krejcie and Morgan Formulae (95% of confidence level & 0.05% margin of error) |

200 | 230 | 170 |

| Crop name | No. of houses | Number of trees planted in home gardens before the onset of HMC (per house) |

Number of trees planted in home gardens with the onset of after HMC (per house) |

Loss of income (LKR/ per month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Areca palm | 345 | 5 - 25 | 10 - 12 | 2500 |

| Sweet potato | 109 | 3 - 10 | 3 - 5 | 500 |

| Ceylon oak | 40 | 2 - 4 | 1 - 2 | 350 |

| Brindle berry | 178 | 3 - 10 | 3 - 4 | 800 |

| Banana | 596 | 2 - 5 | 1 - 2 | 1200 |

| Dwarf olive | 112 | 6 - 8 | 2 - 3 | 1000 |

| Mango | 687 | 6 - 10 | 2- 5 | 4000 |

| Papaya | 744 | 2 - 10 | 3 - 5 | 1500 |

| Maize | 287 | 5 - 6 | 2 - 3 | 600 |

| Passion Fruit | 368 | 4 - 6 | 2 - 3 | 1500 |

| Rambutan | 25 | 1 - 4 | 1 | 350 |

| Wax apple (Jambu) | 99 | 2 -5 | 1 - 2 | 300 |

| Lovi fruit | 129 | 3 - 4 | 1 - 2 | 250 |

| Graviola | 62 | 4 - 6 | 1 - 2 | 350 |

| Wood Apple | 165 | 3 - 5 | 1 - 2 | 250 |

| June plum | 47 | 3 - 6 | 2 - 3 | 300 |

| Cashew | 105 | 3 - 5 | 2 -3 | 400 |

| Orange | 116 | 4 - 6 | 1 -2 | 450 |

| Guava | 242 | 2 -6 | 1 - 2 | 300 |

| Sapodilla | 202 | 5 - 8 | 3 - 4 | 2500 |

| Betel | 404 | 5 - 10 | 5 - 6 | 700 |

| Bird chili | 300 | 20 | 10 - 12 | 800 |

| Brinjal | 229 | 3 - 8 | 2 - 4 | 600 |

| Cassava | 277 | 10 - 25 | 5 -10 | 1500 |

| Cantaloupe | 126 | 3 -6 | 2 -3 | 580 |

| Snake Gourd | 250 | 10 -15 | 4 -5 | 450 |

| Bitter melon | 61 | 10 -15 | 4 - 5 | 350 |

| Drumsticks | 65 | 6 -8 | 2 - 3 | 550 |

| Cowpeas | 185 | 3 -4 | 3 -4 | 380 |

| Ladies' Fingers | 403 | 20 - 40 | 8 -10 | 500 |

| Spinach | 250 | 10 -15 | 5 - 6 | 500 |

| Types of Property damage | Incidence of damages (%) | Monthly cost for repairs or a replacement (LKR) |

| Damage to antennas | 58.6 | 1500 - 2500 |

| Damage to Water Taps and Water Sources | 72.6 | 3500 - 4000 |

| Roof damage | 68.2 | 1000 - 1500 |

| Damage to Garbage Bins | 63.8 | 500 - 1000 |

| Telephone wires / power lines / bulbs | 39.3 | 850 - 1500 |

| Home & vehicle mirrors | 32.2 | 2500 - 3500 |

| Clothes (stealing) | 33.2 | 3500 - 4500 |

| Essential Kitchen Items (Chill bottles, Rice pots etc.) | 40.6 | 1500 - 2500 |

| GND | Distance from the forest (m) |

Number of coconuts destroyed/ per month during the fruiting season | Monthly total economic loss during the fruiting season (LKR) |

Number of days macaques visited the plantation / per month during fruiting season |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deegalla (2 acres, 120 trees) |

30m | 63 – 99 | 5,940 | 23 |

| Kabalewa (1.5 acres, 90 trees) |

150m | 71 - 94 | 5,640 | 18 - 22 |

| Elathalawa (3 acres, 200 trees) |

200m | 12 -20 | 1,200 | 8 - 10 |

| Mitigation Actions | Percentage of method users | Monthly cost (LKR) |

|---|---|---|

| Firecrackers | 90 | 880 – 1200 |

| Covering crops with nets | 23 | 2000 - 2500 |

| Applying black oil to fruit tree trunks | 36 | 1100 - 2500 |

| Using aluminum sheets to wrap around the coconut tree trunks | 41 | 850 – 5000 |

| Acrylic Masks | 79 | 550 - 680 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).