Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

04 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

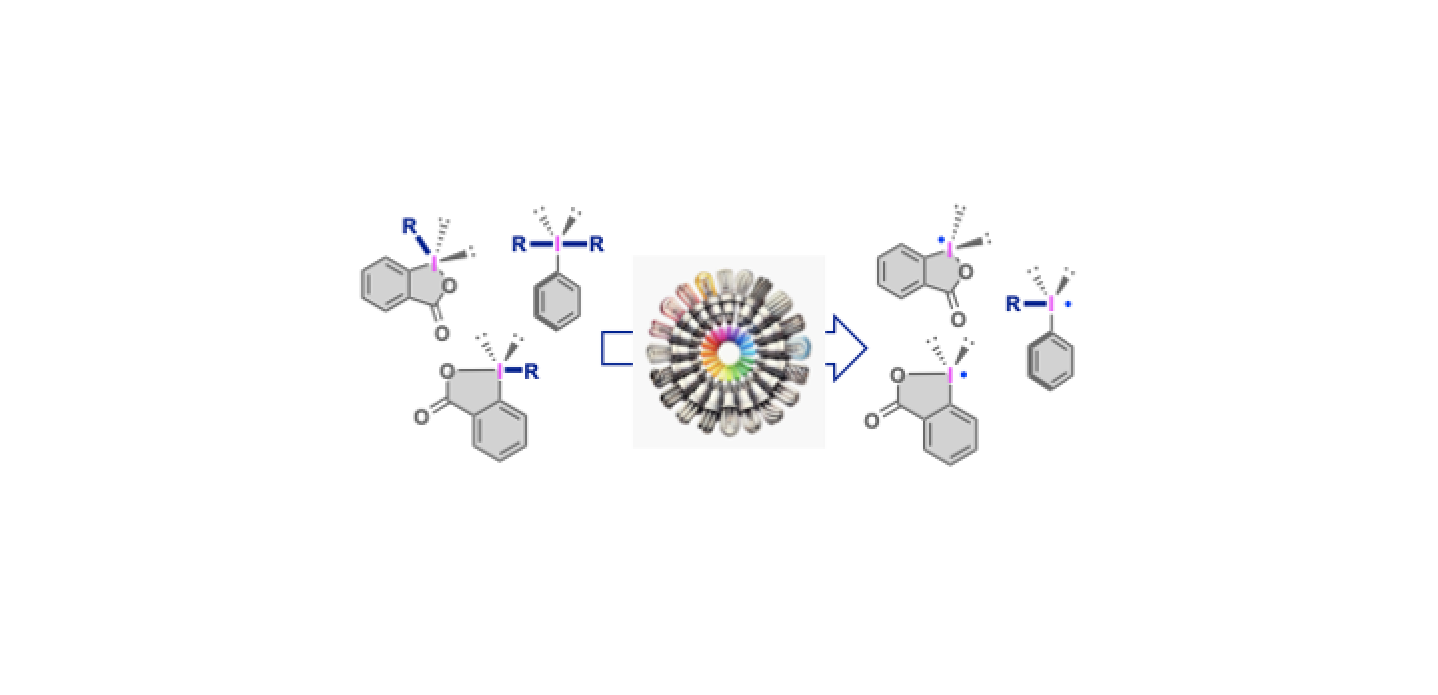

Iodine(III) reagents became a highly relevant tool in organic synthesis due to the great versatility as strong but green oxidants. Several transformations involving the cyclizations as well as functionalization of different organic cores have been broadly described and reviewed. Herein a new facet which involves the participation of these reagents in photochemical transformations exclusively by direct irradition or in photoredox cycles using some transition metals, will be briefly described as well as some plausible further transformations that potentially can be developed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. General Considerations

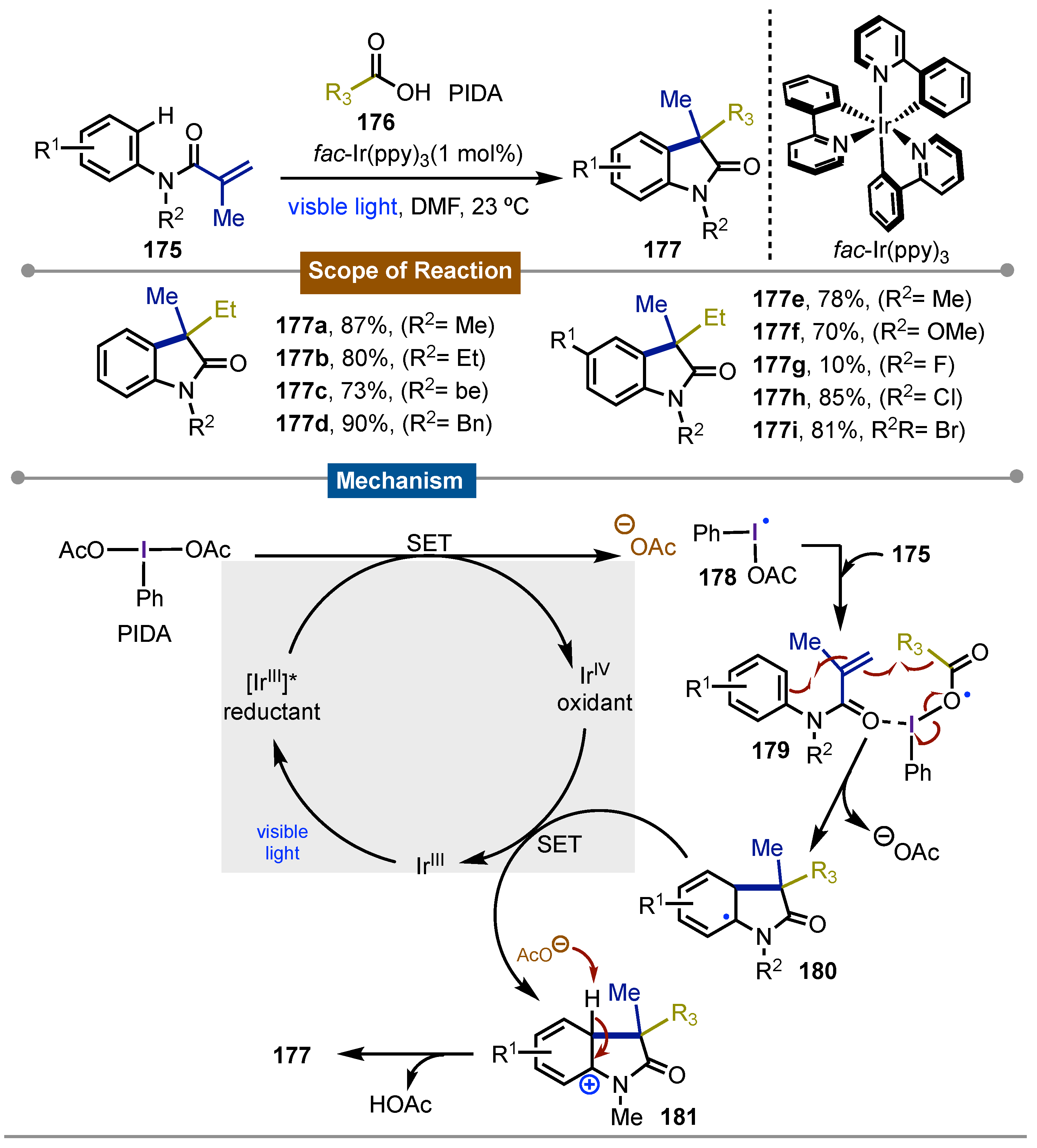

4. Photocatalytic Synthetic Methods using Iodine(III) Reagents

5. Summary and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Satkar, Y.; Juárez Ornelas, K. A.; Mali, N.; Patil, D. B.; Gámez-Montaño, R.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; Lagunas-Rivera, S.; Ortíz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Oxidative Halogenation of Arenes, Olefins and Alkynes Mediated by Iodine(III) Reagents. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2021, 18, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Alonso-Castro, A. J.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Dohi, T.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine (III) reagents for oxidative aromatic halogenation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 5009–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikushima, K.; Elboray, E. E.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Dohi, T. Diaryliodonium (III) salts in one-pot double functionalization of C–IIII and ortho C–H bonds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 3231–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Granados-López, A. J.; González-García, G.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; de León-Solis, C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)-Mediate Oxidative Cyanation, Azidation, Nitration, Sulfenylation and Slenization in Olefins and Aromatic Systems. Curr. Org. Chem. 2022, 26, 1954–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Rivera, R.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Chacón-García, L.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)-Aluminum or -Ammonium Salts for the Oxidative Aromatic Inorganic Functionalization. ChemisrtySelect. 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Nava, M. P.; Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Ibarra-Gutiérrez, J. G.; Chávez-Rivera, R.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III) reagents for the aromatic functionalization with inorganic groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 2024, 166, 134203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahide, P. D.; Ramadoss, V.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Satkar, Y.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Cervera-Villanueva, J. M. J.; Alonso-Castro, Á. J.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; Ramírez-Morales, M. A.; Ruiz-Padilla, A. J.; Deveze-Álvarez, M. A.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. In Situ Formed IIII-Based Reagent for the Electrophilic Ortho-Chlorination of Phenols and Phenol Ethers: The Use of PIFA-AlCl3 System. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkar, Y.; Ramadoss, V.; Nahide, P. D.; García-Medina, E.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Alonso-Castro, A. J.; Chávez-Rivera, R.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Practical, Mild and Efficient Electrophilic Bromination of Phenols by a New I(III)-based reagent: The PIDA–AlBr3 System. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 17806–17812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkar, Y.; Yera-Ledesma, L. F.; Mali, N.; Patil, D.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Ramírez-Morales, P. I.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)-Mediated, Controlled Di- or Monoiodination of Phenols. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 4149–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Quezada, A.; Satkar, Y.; Patil, D.; Mali, N.; Wrobel, K.; González, G.; Zárraga, R.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)/AlX3-mediated electrophilic chlorination and bromination of arenes. Dual Role of AlX3 (X = Cl, Br) for (PhIO)n depolymerization and as the halogen source. Tetrahedron Lett. 2019, 60, 1551–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D. B.; Gámez-Montaño, R.; Ordoñez, M.; Solis-Santos, M.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)-Mediated Electrophilic Chlorination and Catalytic Nitration of N-Tosyl Anilines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202201295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, N.; Ibarra-Gutiérrez, J. G.; Lugo Fuentes, L. I.; Ortíz-Alvarado, R.; Chacón-García, L.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Iodine(III)-Mediated Free-Aniline Iodination through Acetyl Hypoiodite Formation: Study of the Reaction Pathway. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202201067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Solís-Hernández, M.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Divergent role of PIDA and PIFA in the AlX3 (X = Cl, Br) halogenation of 2-naphthol: a mechanistic study. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2024, 20, 1580–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Kato, T.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Maruoka, K. Iodine(III)-Catalyzed Electrophilic Nitration of Phenols via Non-Brønsted Acidic NO2+ Generation. Org. Lett. 2019, 21(5), 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahide, P. D.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Mild, Rapid and Efficient Metal-Free Synthesis of 2-Aryl-4-Aryloxyquinolines via Direct Csp2O Bond Formation by Using Diaryliodonium Salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkar, Y.; Wrobel, K.; Trujillo-González, D. E.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. The Diaryliodonium(III) Salts Reaction With Free-Radicals Enables One-Pot Double Arylation of Naphthols. Front. Chem. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naakajima, M.; Nagaswaa, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Matsuda, Y.; Nemoto, T. Synthesis of Visible-Light–Activated Hypervalent Iodine and Photooxidation under Visible Light Irradiation via a Direct S0→Tn Transition. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 70, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Cano, J. R.; Nahide, P. D.; Ramadoss, V.; Satkar, Y.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Mendoza-Macías, C. L.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of New 3,4-Diarylmaleimides as Enhancers (Modulators) of Doxorubicin Cytotoxic Activity on Cultured Tumor Cells from a Real Case of Breast Cancer. J. Mex.Chem. Soc. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, V.; Alonso-Castro, A. J.; Campos-Xolalpa, N.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Protecting-Group-Free Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 3-Methylkealiiquinone and Structural Analogues. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 10627–10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, V.; Alonso-Castro, A. J.; Campos-Xolalpa, N.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Yahuaca-Juárez, B.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Total synthesis of kealiiquinone: the regio-controlled strategy for accessing its 1-methyl-4-arylbenzimidazolone core. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 30761–30776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Ramadoss, V.; Gámez-Montaño, R.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; Alonso-Castro, A. J. Total synthesis of the linear and angular 3-methylated regioisomers of the marine natural product kealiiquinone and biological evaluation of related Leucetta sp. alkaloids on human breast cancer. Med. Chem. Res. 2019, 28, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahide, P. D.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Chávez-Rivera, R.; Romo-Rodríguez, P.; Solís-Hernández, M.; Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Gámez-Montaño, R.; Deveze-Álvarez, M. A.; Ramírez-Morales, M. A.; Alonso-Castro, A. J.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; Ruiz-Padilla, A. J.; Mendoza-Macías, C. L.; Meza-Carmen, V.; Cortés-García, C. J.; Corrales-Escobosa, A. R.; Núñez-Anita, R. E.; Ortíz-Alvarado, R.; Chacón-García, L.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Novel 2-aryl-4-aryloxyquinoline-based fungistatics for Mucor circinelloides. Biological evaluation of activity, QSAR and docking study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2022, 63, 128649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Ortíz-Alvarado, R.; Chávez-Rivera, R.; Tapia-Juárez, M.; González-Domínguez, M. I.; Ruiz-Padilla, A. J.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; de León-Solís, C.; Solorio Alvarado, C. R. Indomethacin Synthesis, Historical Overview of Their Structural Modifications. ChemistrySelect. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Velázquez, E. D.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Alonso-Castro, Á. J.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; López, J. A.; Meza-Carmen, V.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Metformin, a biological and synthetic overview. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 86, 129241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Velázquez, E. D.; Herrera, M. D.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Ortíz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Synthesis and in vivo Evaluation of Fluorobenzyl Metformin Derivatives as Potential Drugs in The Diabetes Treatment. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Hernández-Velázquez, E. D.; Corrales-Escobosa, A. R.; de León-Solis, C.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Ningalins, Pyrrole-Bearing Metabolites Isolated from Didemnum spp. Synthesis and MDR-Reversion Activity in Cancer Therapy. Chem. Biodiversity. 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Chacón-García, L.; Chávez-Rivera, R.; Navarro-Santos, P.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Tapia-Juárez, M.; Negrete-Díaz, J. V.; Martínez-Morales, J. F.; Deveze-Álvarez, M. A.; Zapata-Morales, J. R.; Solorio Alvarado, C. R. Synthesis and Anti-inflammatory Effect of Simple 2,3-Diarylindoles. On Route to New NSAID Scaffolds. ChemistrySelect. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraire-Soto, I.; Araujo-Huitrado, J. G.; Granados-López, A. J.; Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Herrera, M. D.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.; Reyes-Hernández, C. A.; López-Hernández, Y.; Tapia-Juárez, M.; Negrete-Díaz, J. V.; Chacón-García, L.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; López, J. A. Differential Effect of 4H-Benzo[d] [1, 3]oxazines on the Proliferation of Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 6306–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadoss, V.; Nahide, P. D.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Rentería-Gómez, M.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. A four-step scalable formal synthesis of ningalin C. ARKIVOC. 2016, 2016, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahide, P. D.; Jiménez-Halla, J. O. C.; Wrobel, K.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Ortiz Alvarado, R.; Yahuaca-Juárez, B. Gold(I)-catalysed high-yielding synthesis of indenes by direct Csp3–H bond activation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 7330–7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Quezada, L. A.; Torres-Carbajal, K. R.; Mali, N.; Patil, D. B.; Luna-Chagolla, M.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Tapia-Juárez, M.; Fraire-Soto, I.; Araujo-Huitrado, J. G.; Granados-López, A. J.; Gutiérrez-Hernández, R.; Reyes-Estrada, C. A.; López-Hernández, Y.; López, J. A.; Chacón-García, L.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Synthesis of 4H-Benzo[d][1,3]oxazines and Biological Evaluation of Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 6944–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Núñez, E.; Raducan, M.; Lauterbach, T.; Molawi, K.; Solorio, C. R.; Echavarren, A. M. Evolution of Propargyl Ethers into Allylgold Cations in the Cyclization of Enynes. Angew. Chem, Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6152–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Echavarren, A. M. Gold-Catalyzed Annulation/Fragmentation: Formation of Free Gold Carbenes by Retro-Cyclopropanation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11881–11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Wang, Y.; Echavarren, A. M. Cyclopropanation with Gold(I) Carbenes by Retro-Buchner Reaction from Cycloheptatrienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11952–11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGonigal, P. R.; de León, C.; Wang, Y.; Homs, A.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Echavarren, A. M. Gold for the Generation and Control of Fluxional Barbaralyl Cations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 13093–13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moteki, S. A.; Usui, A.; Zhang, T.; Solorio Alvarado, C. R.; Maruoka, K. Site-Selective Oxidation of Unactivated Csp3-H Bonds with Hypervalent Iodine(III) Reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 13093–13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahuaca-Juárez, B.; González, G.; Ramírez-Morales, M. A.; Alba-Betancourt, C.; Deveze-Álvarez, M. A.; Mendoza-Macías, C. L.; Ortiz-Alvarado, R.; Juárez-Ornelas, K. A.; Solorio-Alvarado, C. R.; Maruoka, K. Iodine(III)-catalyzed benzylic oxidation by using the (PhIO)n/Al(NO3)3 system. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

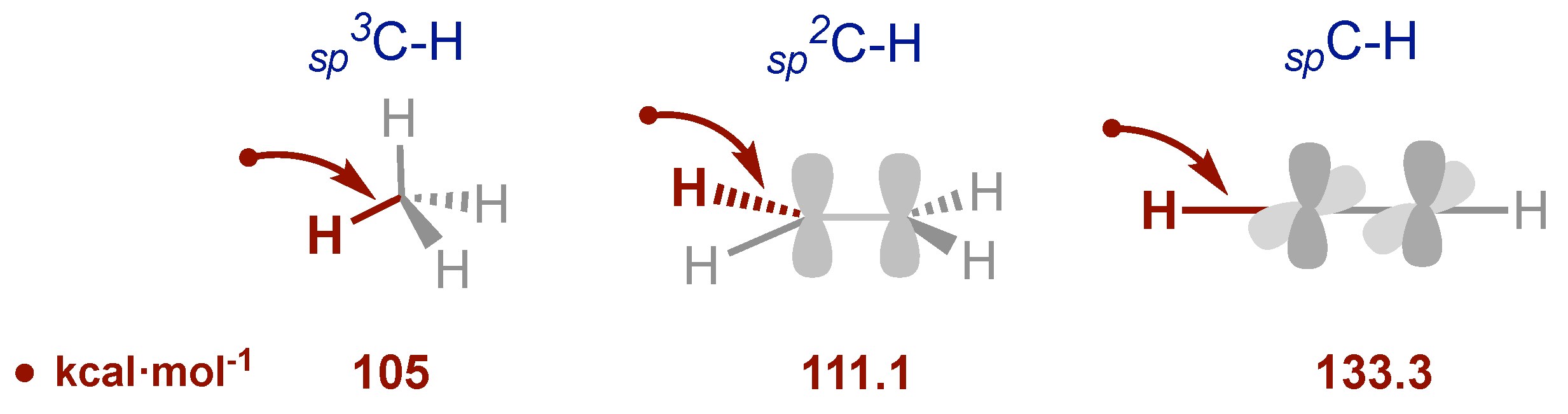

- Xue, X.-S.; Ji, P.; Zhou, B.; Cheng, J. P. The Essential Role of Bond Energetics in C–H Activation/Functionalization. Chem. Rev. 2017; 117, 8622–8648. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, A. C.; Richard, J. S. Advanced Organic Chemistry, 5th ed.; Springer US, 2007; p. 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepión, J. I.; Francisco, C. G.; Hern´ andez, R.; Salazar, J. A. and Suárez, E., Tetrahedron Lett., 1984, 25, 1953-1956.

- Hernández, R.; León, E. I.; Moreno, P.; Riesco-Fagundo, C. and Suárez, E., J. Org. Chem., 2004, 69, 8437-8444.

- Boto, A.; Hernández, D.; Hernández, R. and Suárez, E., J. Org. Chem., 2003, 68, 5310-5319.

- Francisco, C. G.; González, C. C.; Paz, N. R. and Suárez, E., Org. Lett., 2003, 5, 4171-4173.

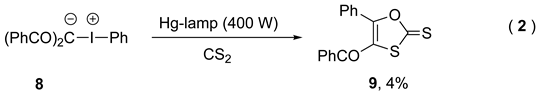

- Papadopoulou, M.; Spyroudis, S.; Varvoglis, A. 1,3-Oxathiole-2-Thiones from the Reaction of Carbon Disulfide with Zwitterionic Iodonium Compounds. J. Org. Chem, 1985, 50, 1509–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

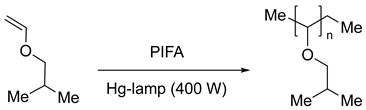

- Georgiev, G.; Spyroudis, S.; Varvoglis, A. Diacetoxyiodobenzene and Bis(Trifluoroacetoxy)Iodobenzene as Photoinitiators for Cationic Polymerisations. Polym. Bull. [CrossRef]

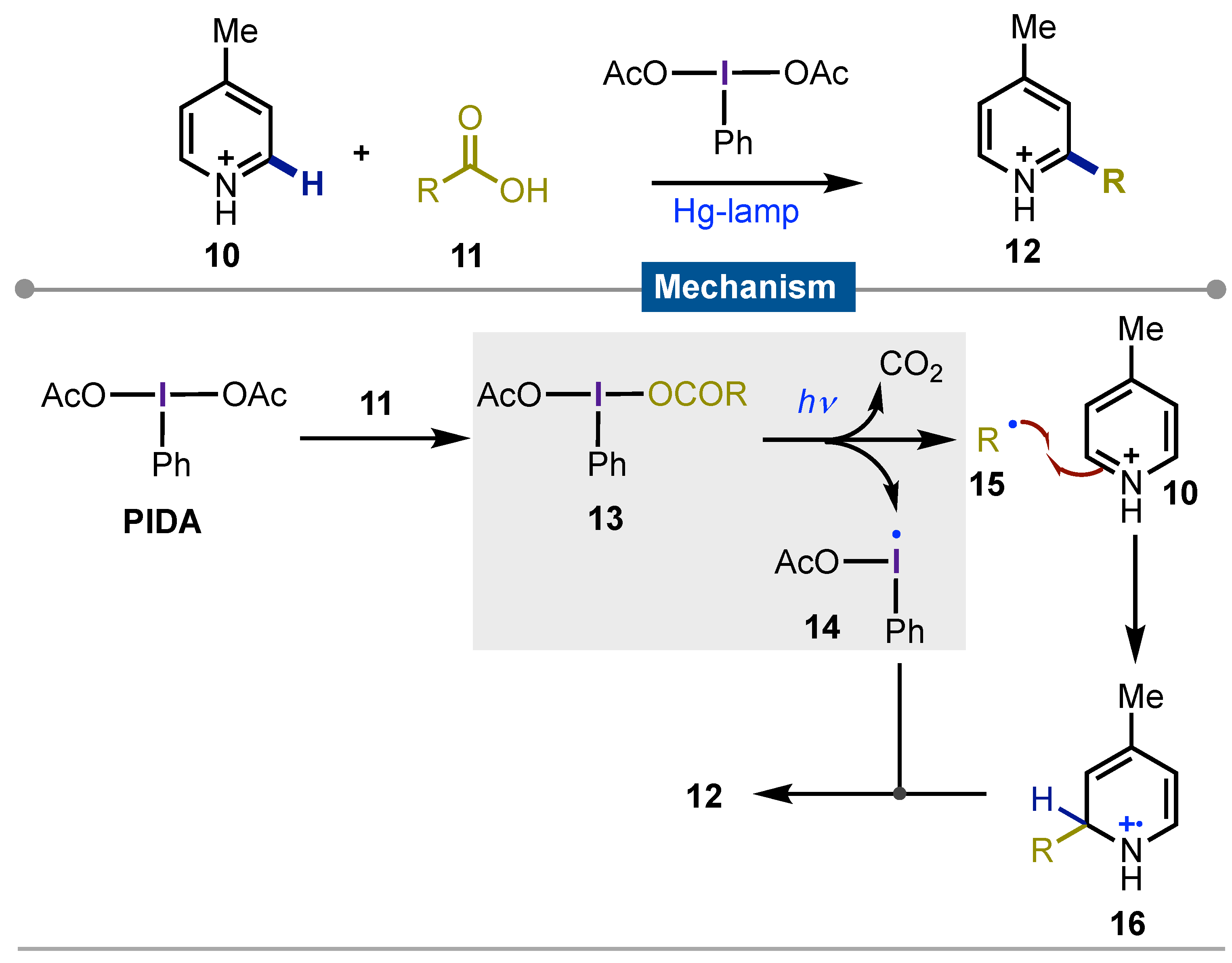

- Minisci, F.; Vismara, E.; Fontana, F.; Claudia Nogueira Barbosa, M. A New General Method of Homolytic Alkylation of Protonated Heteroaromatic Bases by Carboxylic Acids and Iodosobenzene Diacetate. Tetrahedron Lett, 1989, 30, 4569–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

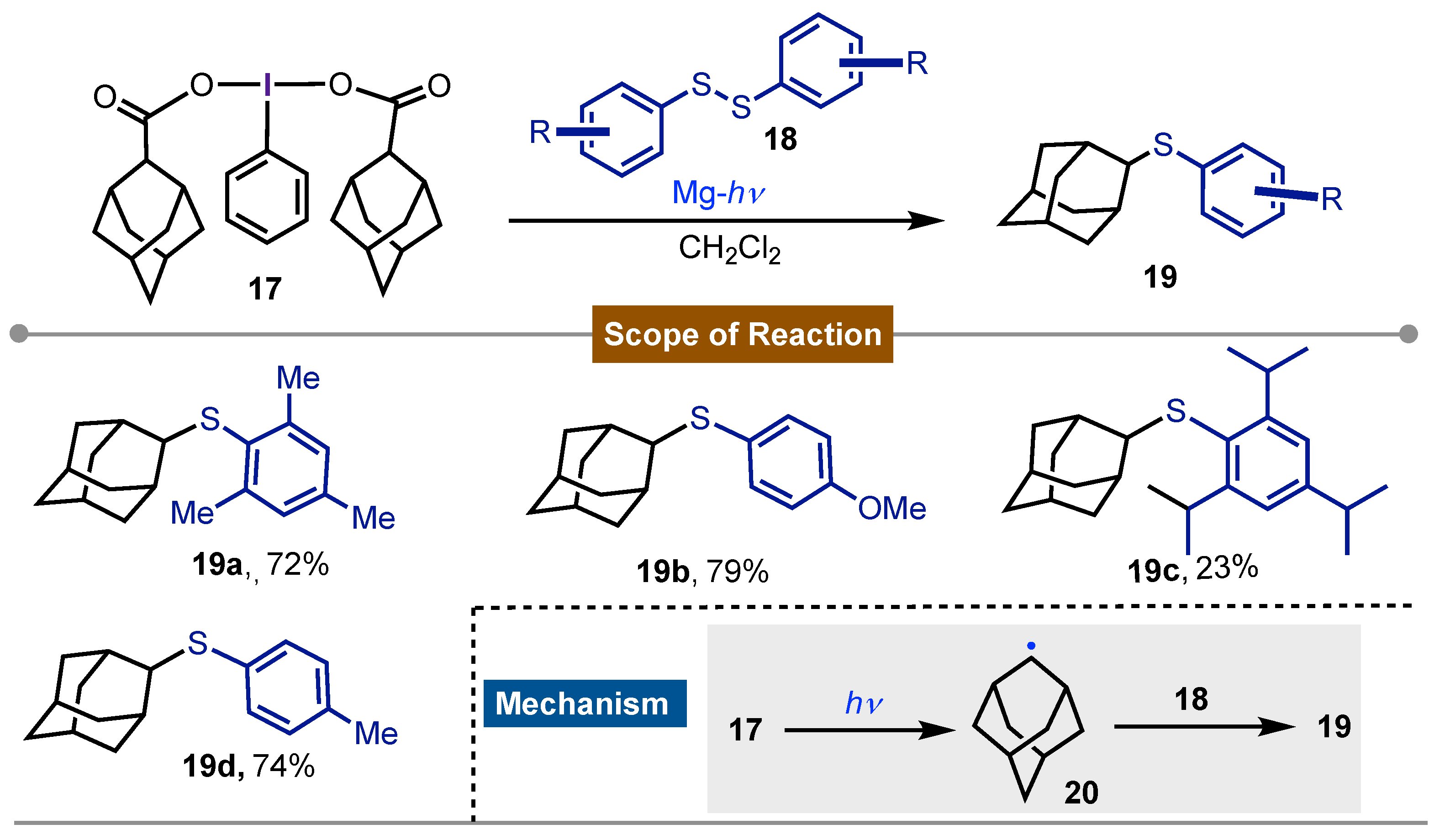

- Togo, H.; Muraki, T.; Yokoyama, M. Preparation of Adamantyl Sulfides with [Bis(1-Adamantanecarboxy)Iodo]Arenes and Disulfides. Synthesis 1995, 1995, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

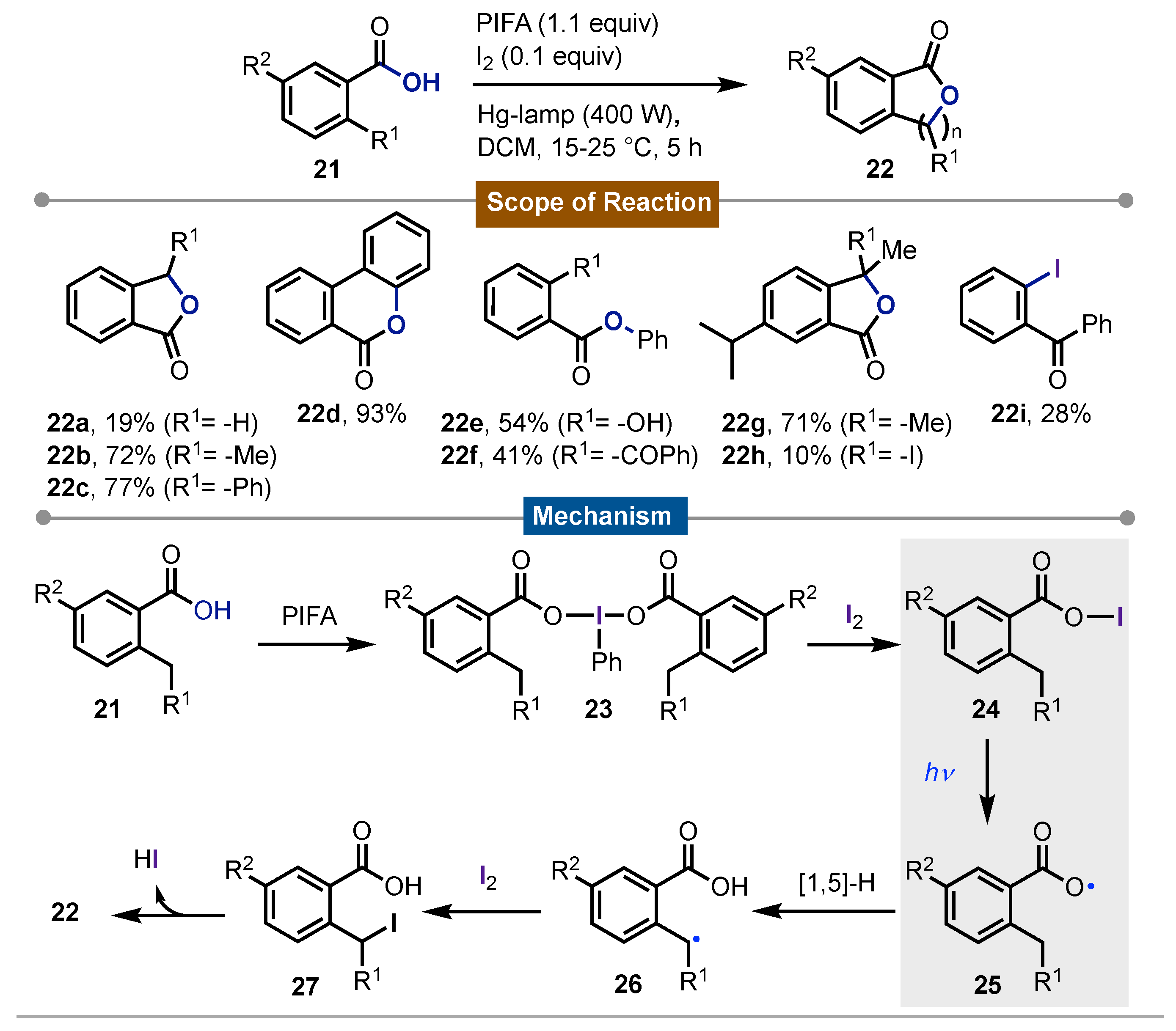

- Togo, H.; Muraki, T.; Hoshina, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yokoyama, M. Formation and Synthetic Use of Oxygen-Centred Radicals with (Diacetoxyiodo)Arenes. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1, 1997, 787–794. [CrossRef]

- Gogonas, E. P.; Hadjiarapoglou, L. P. [3+2]-Cycloaddition Reactions of 2-Phenyliodonio-5,5-Dimethyl-1,3-Dioxacyclohexanemethylide. Tetrahedron Lett, 2000, 41, 9299–9303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

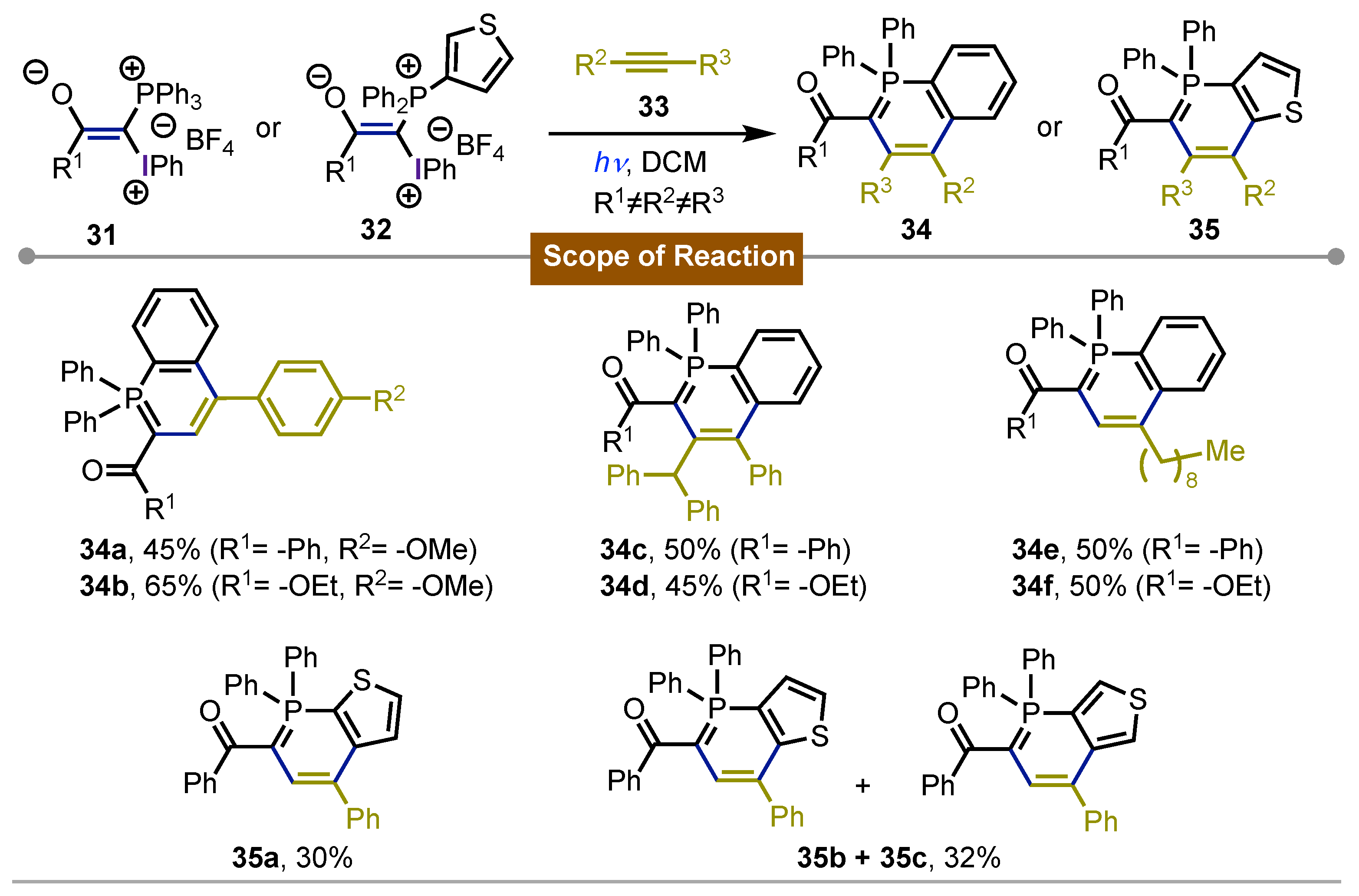

- Matveeva, E. D.; Podrugina, T. A.; Pavlova, A. S.; Mironov, A. V.; Borisenko, A. A.; Gleiter, R.; Zefirov, N. S. Heterocycles from Phosphonium−Iodonium Ylides. Photochemical Synthesis of λ5-Phosphinolines. J. Org. Chem 2009, 74, 9428–9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matveeva, E. D.; Podrugina, T. A.; Taranova, M. A.; Borisenko, A. A.; Mironov, A. V.; Gleiter, R.; Zefirov, N. S. Photochemical Synthesis of Phosphinolines from Phosphonium−Iodonium Ylides. J. Org. Chem 2010, 76, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekipelova, T. D.; Kuzmin, V. A.; Matveeva, E. D.; Gleiter, R.; Zefirov, N. S. On the Mechanism of Photoinduced Addition of Acetonitrile to Phosphonium–Iodonium Ylides. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2012, 26, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekipelova, T. D.; Taranova, M. A.; Matveeva, E. D.; Podrugina, T. A.; Kuzmin, V. A.; Zefirov, N. S. Mechanism and Remarkable Features of Photoinduced Cycloaddition of Phenylacetylene to Mixed Phosphonium-Iodonium Ylide. Dokl. Akad. Nauk 2012, 447, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

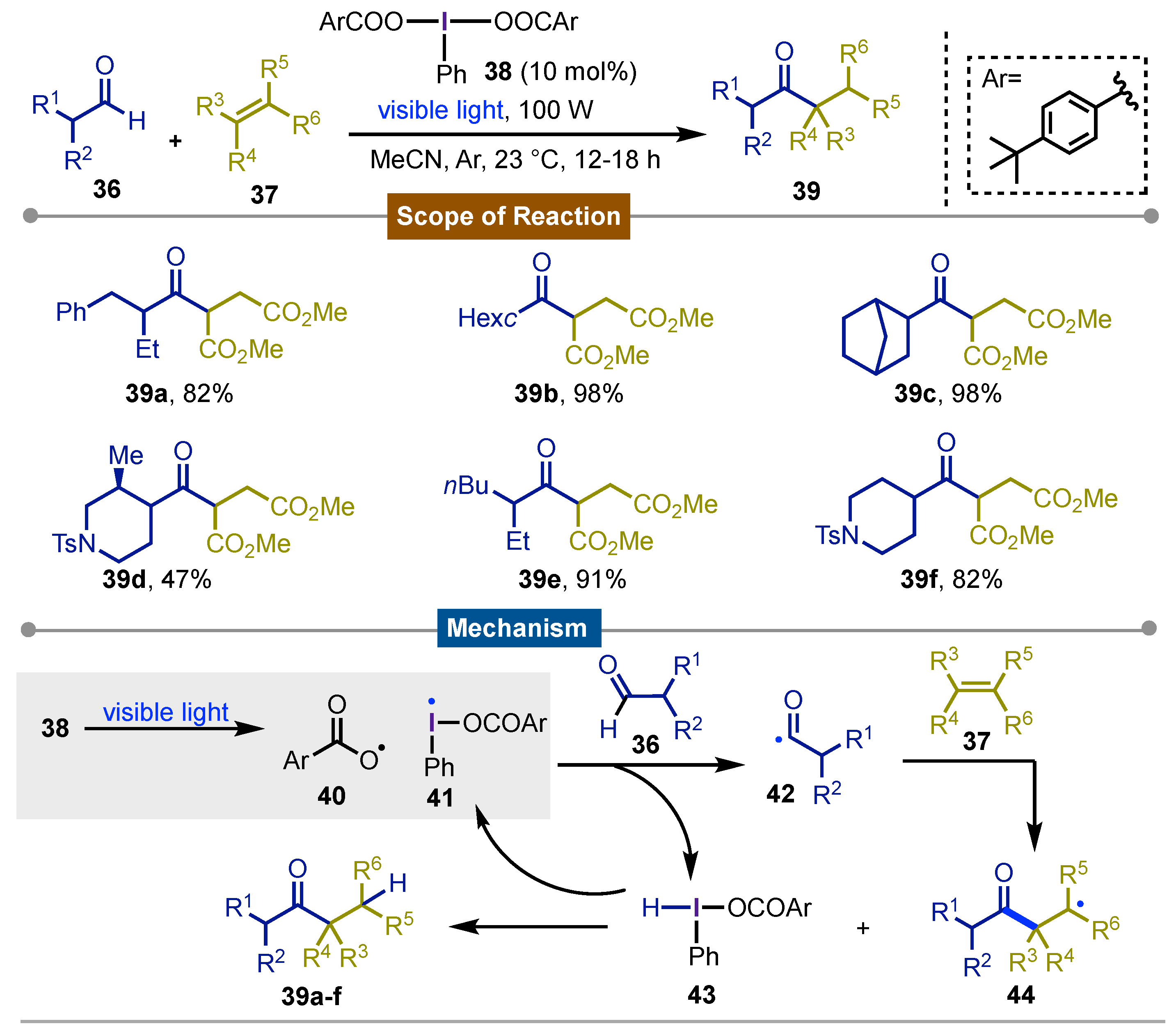

- Moteki, S. A.; Usui, A.; Selvakumar, S.; Zhang, T.; Maruoka, K. Metal-Free CH Bond Activation of Branched Aldehydes with a Hypervalent Iodine(III) Catalyst under Visible-Light Photolysis: Successful Trapping with Electron-Deficient Olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 11060–11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

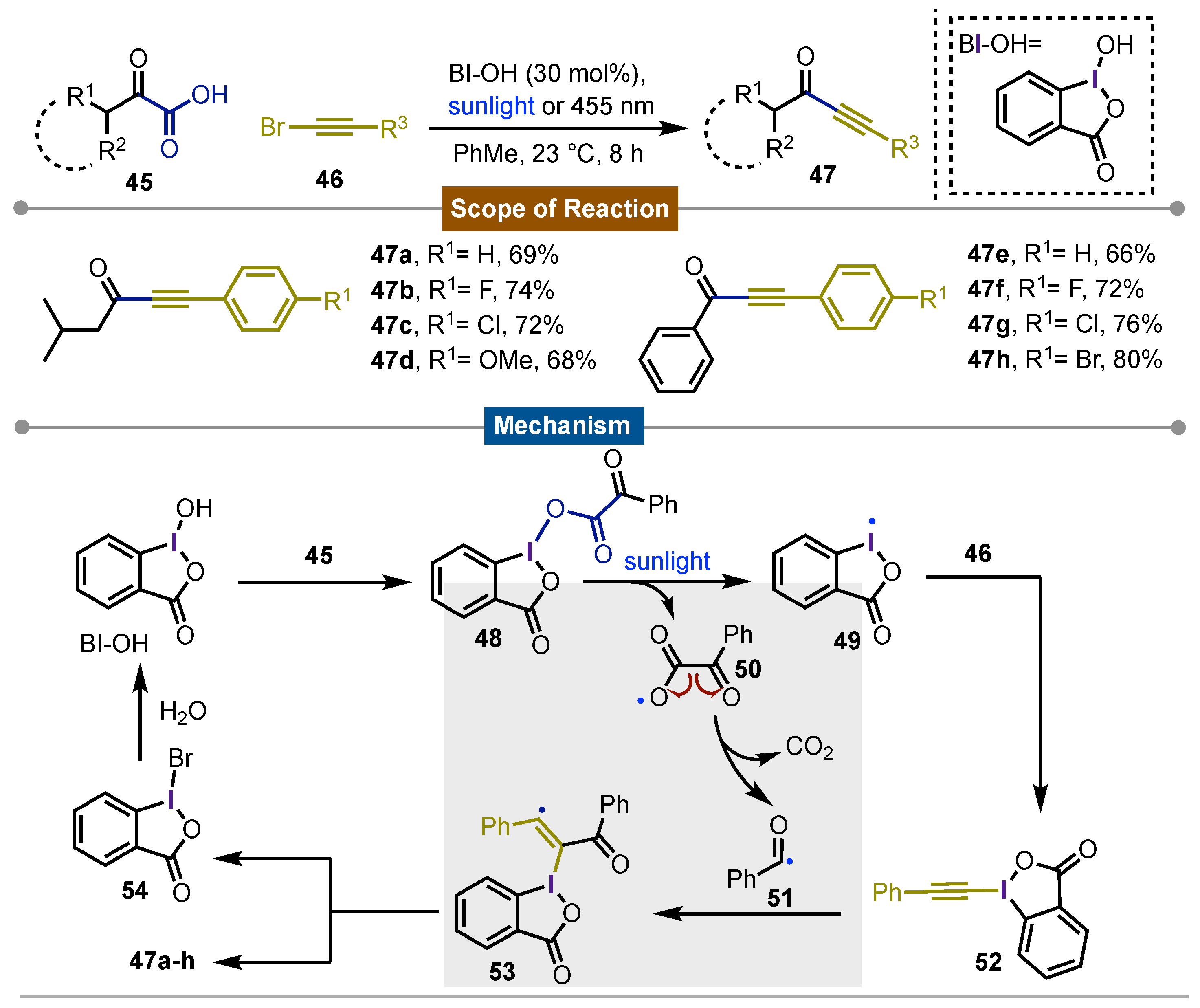

- Tan, H.; Li, H.; Ji, W.; Wang, L. Sunlight-Driven Decarboxylative Alkynylation of α-Keto Acids with Bromoacetylenes by Hypervalent Iodine Reagent Catalysis: A Facile Approach to Ynones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 8374–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

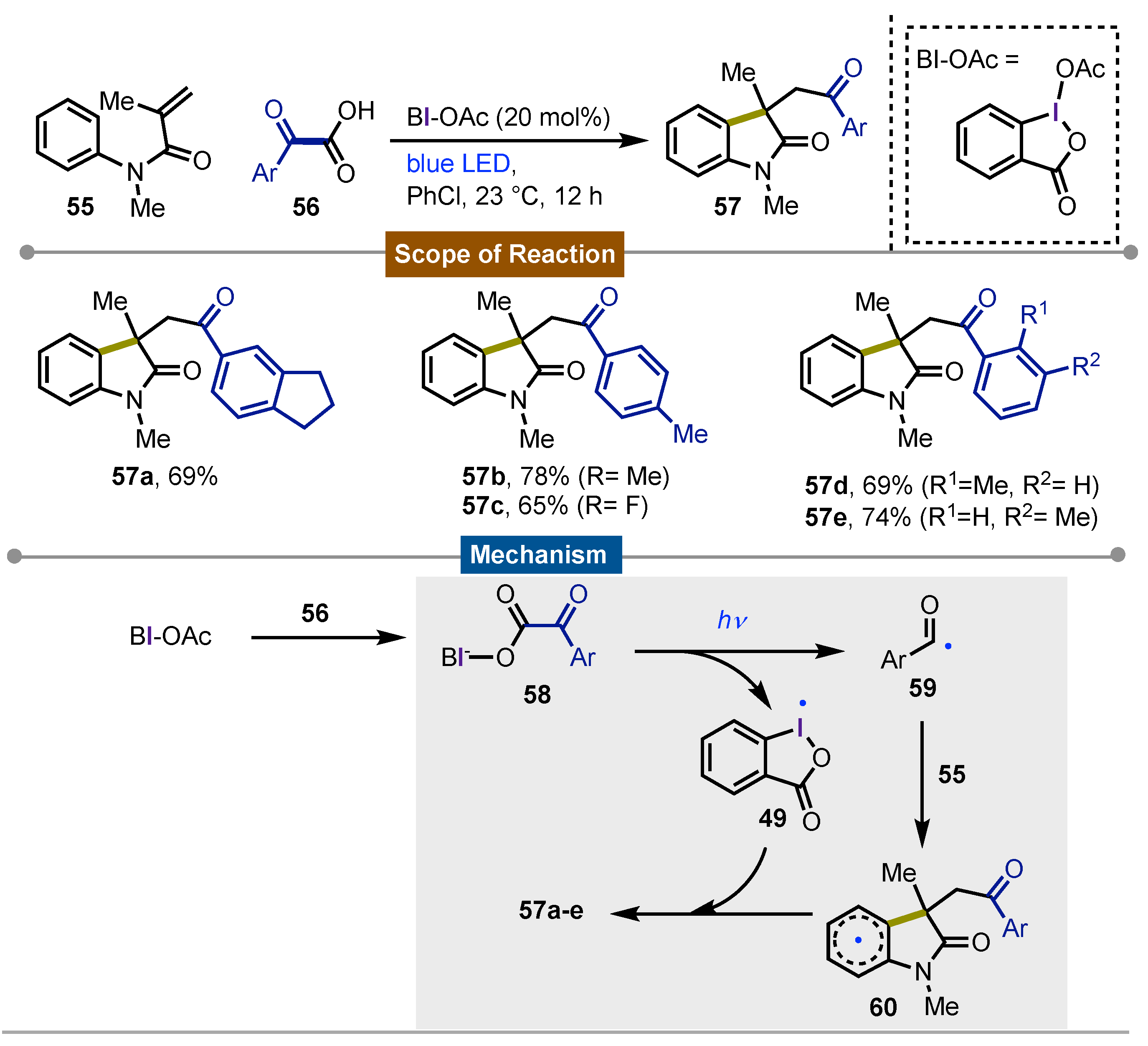

- Ji, W.; Tan, H.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Wang, L. Photocatalyst-Free Hypervalent Iodine Reagent Catalyzed Decarboxylative Acylarylation of Acrylamides with α-Oxocarboxylic Acids Driven by Visible-Light Irradiation. Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 1462–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

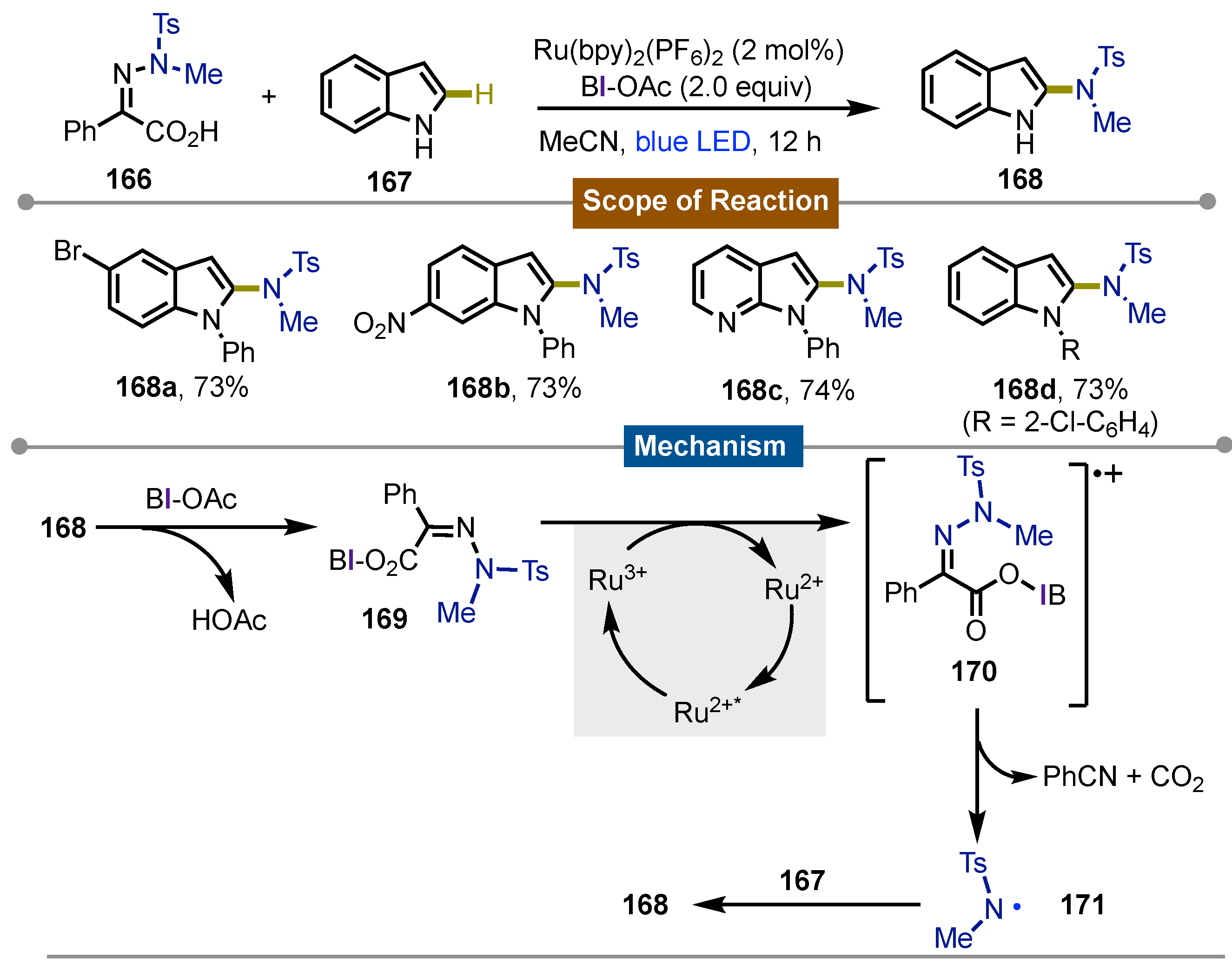

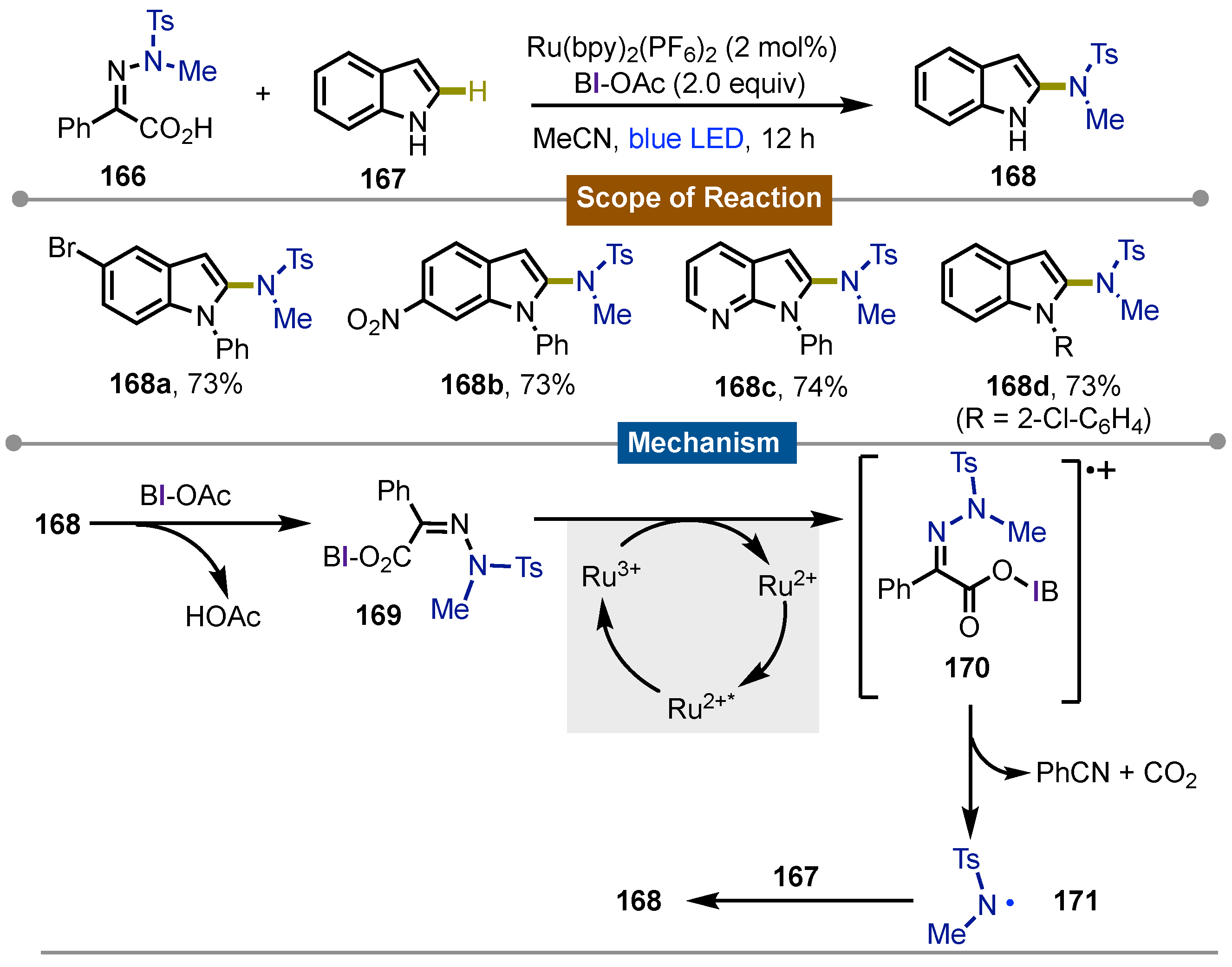

- Lucchetti, N.; Tkacheva, A.; Fantasia, S.; Muñiz, K. Radical C−H-Amination of Heteroarenes Using Dual Initiation by Visible Light and Iodine. Adv. Synth. Catal 2018, 360, 3889–3893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

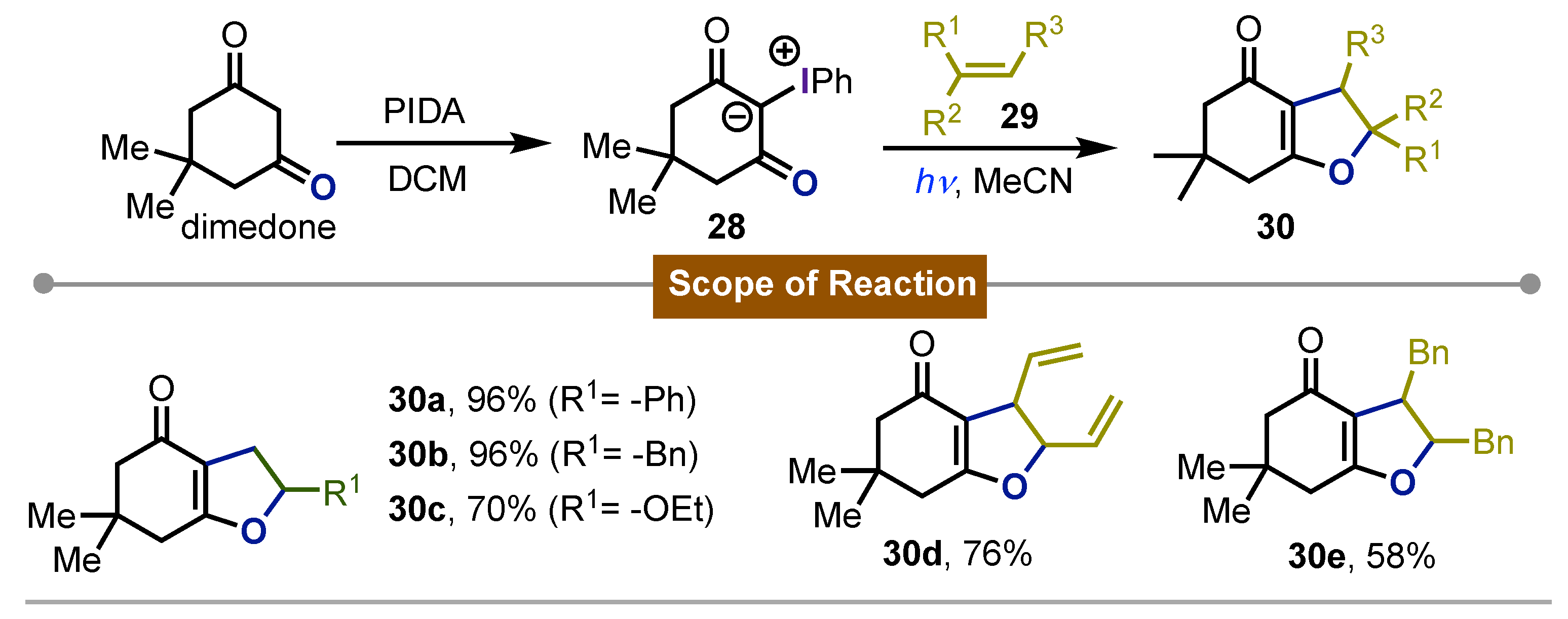

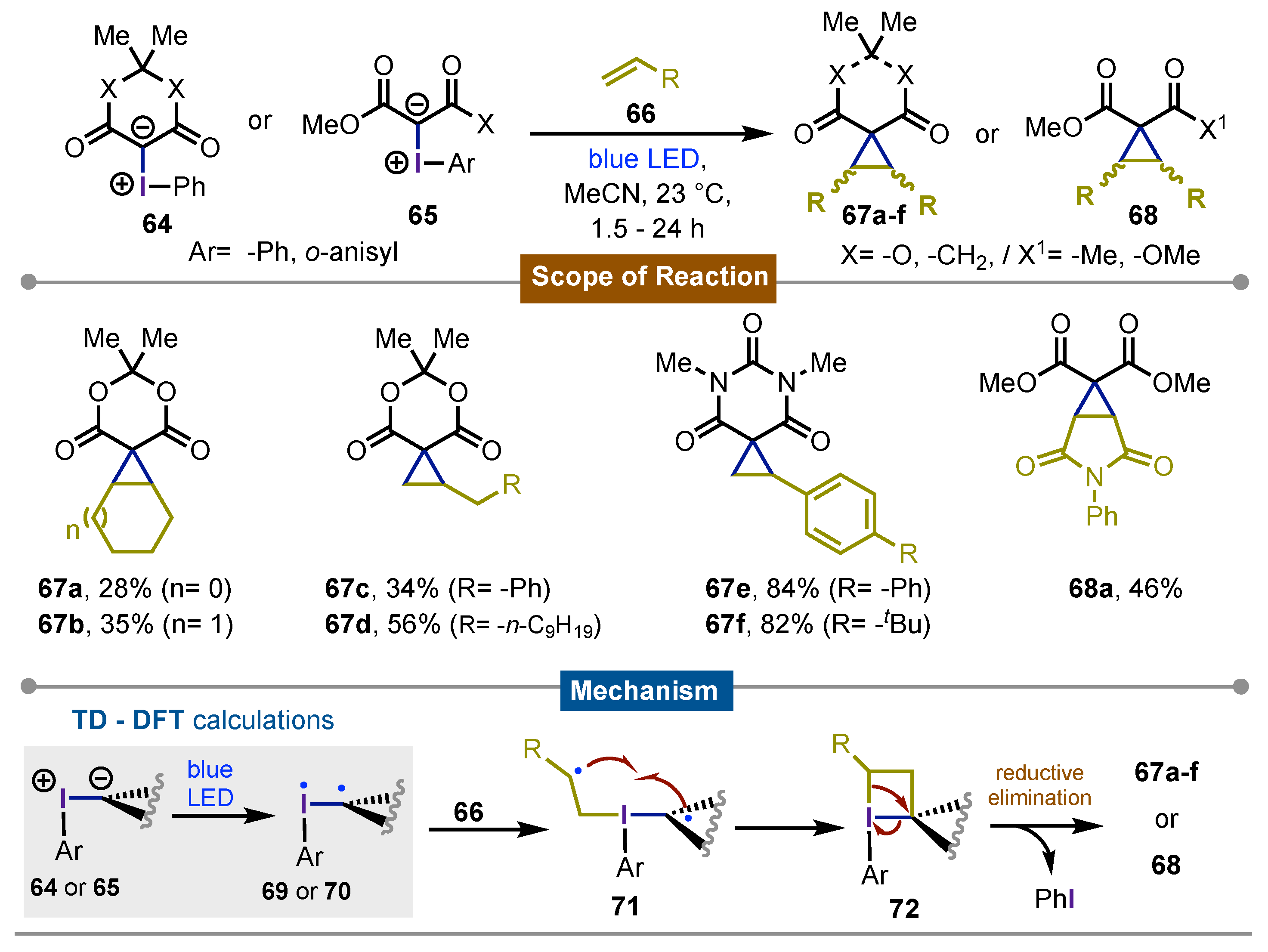

- Chidley, T.; Jameel, I.; Rizwan, S.; Peixoto, P. A.; Pouységu, L.; Quideau, S.; Hopkins, W. S.; Murphy, G. K. Blue LED Irradiation of Iodonium Ylides Gives Diradical Intermediates for Efficient Metal-free Cyclopropanation with Alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 16959–16965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

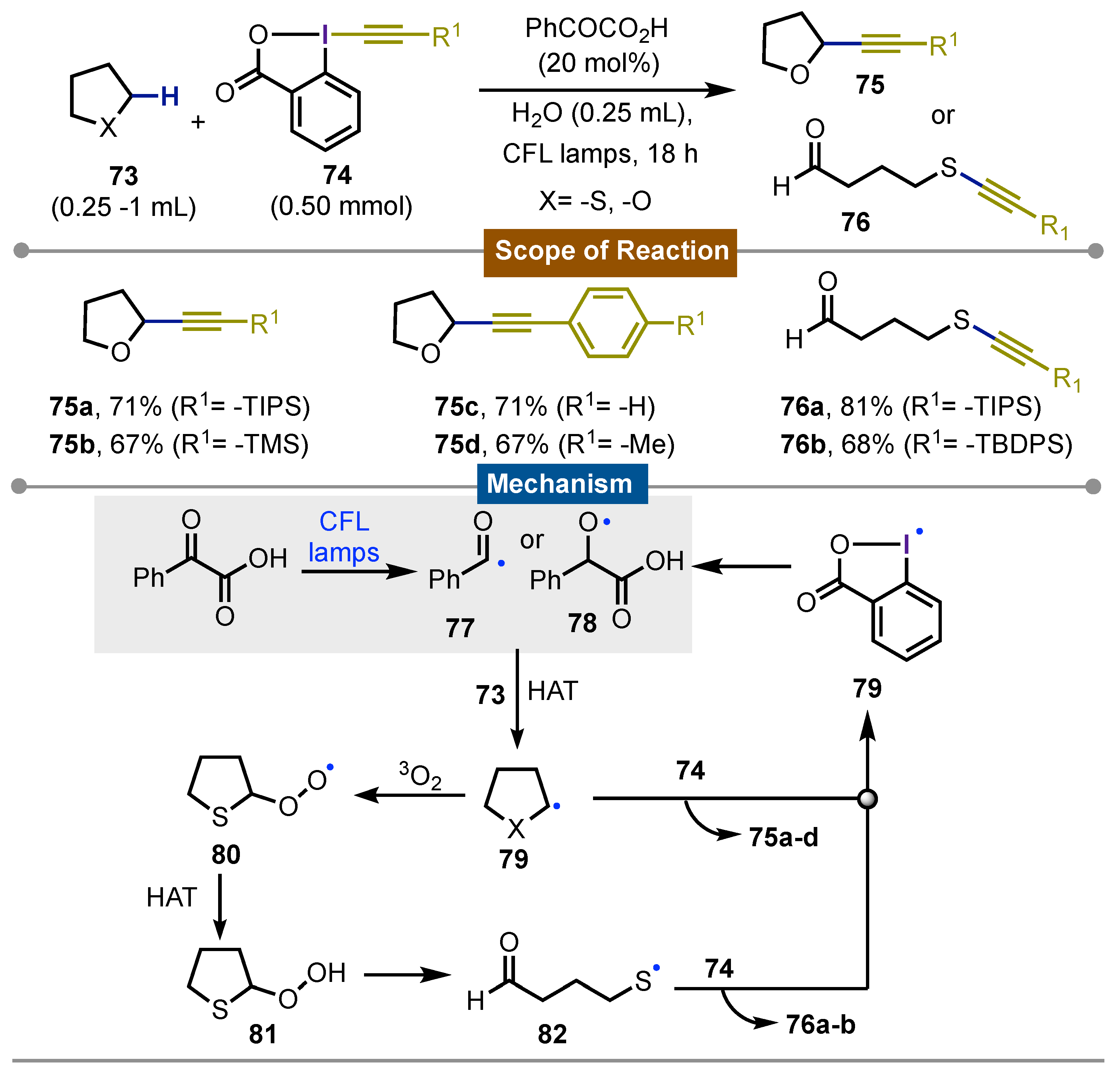

- Voutyritsa, E.; Garreau, M.; Kokotou, M. G.; Triandafillidi, I.; Waser, J.; Kokotos, C. G. Photochemical Functionalization of Heterocycles with EBX Reagents: C−H Alkynylation versus Deconstructive Ring Cleavage. Chem. Eur. J 2020, 26, 14453–14460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

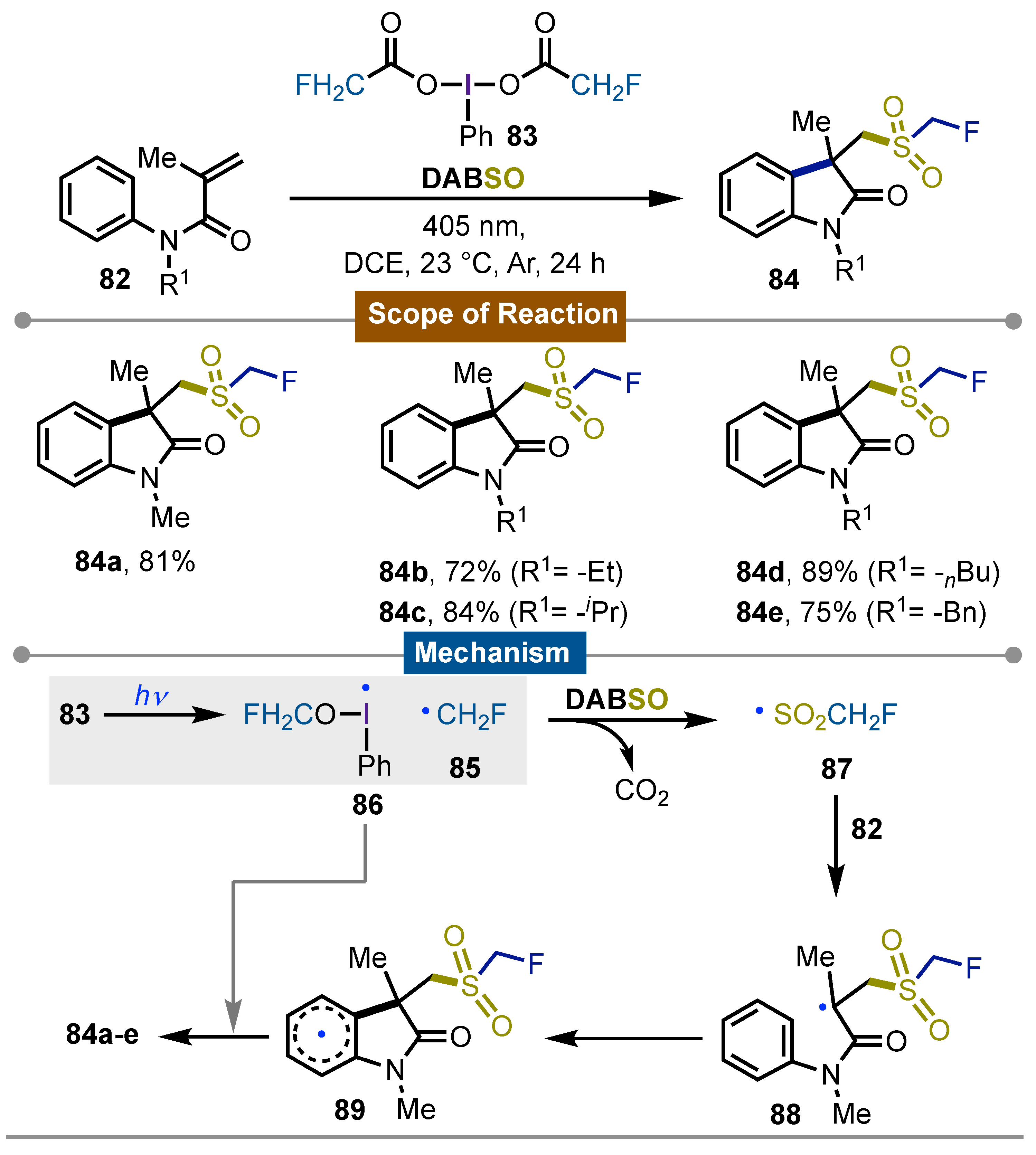

- Induced, Catalyst-Free Monofluoromethyl Sulfonylation of Alkenes with Iodine(III) Reagent and DABSO. Org. Lett 2023, 25, 7062–7066. [CrossRef]

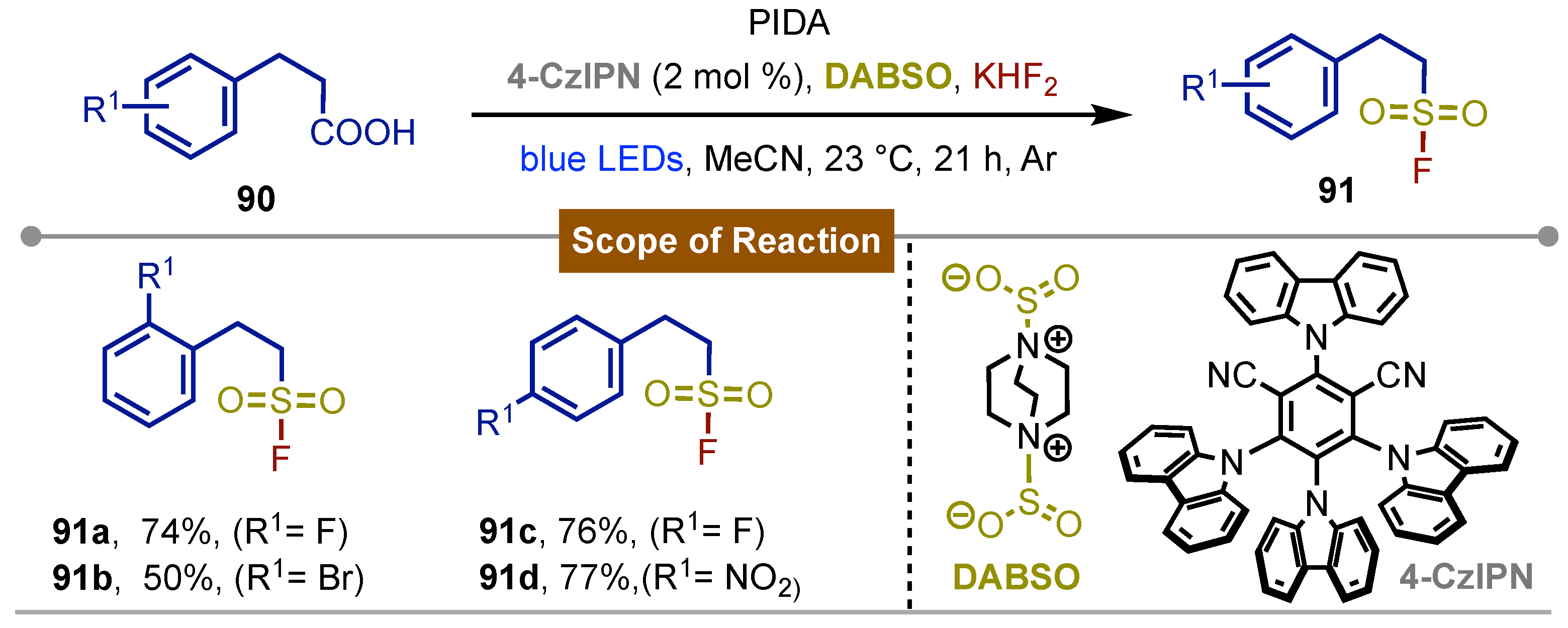

- Ou, C.; Cai, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, C. Aliphatic Sulfonyl Fluoride Synthesis via Decarboxylative Fluorosulfonylation of Hypervalent Iodine(III) Carboxylates. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 6751–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

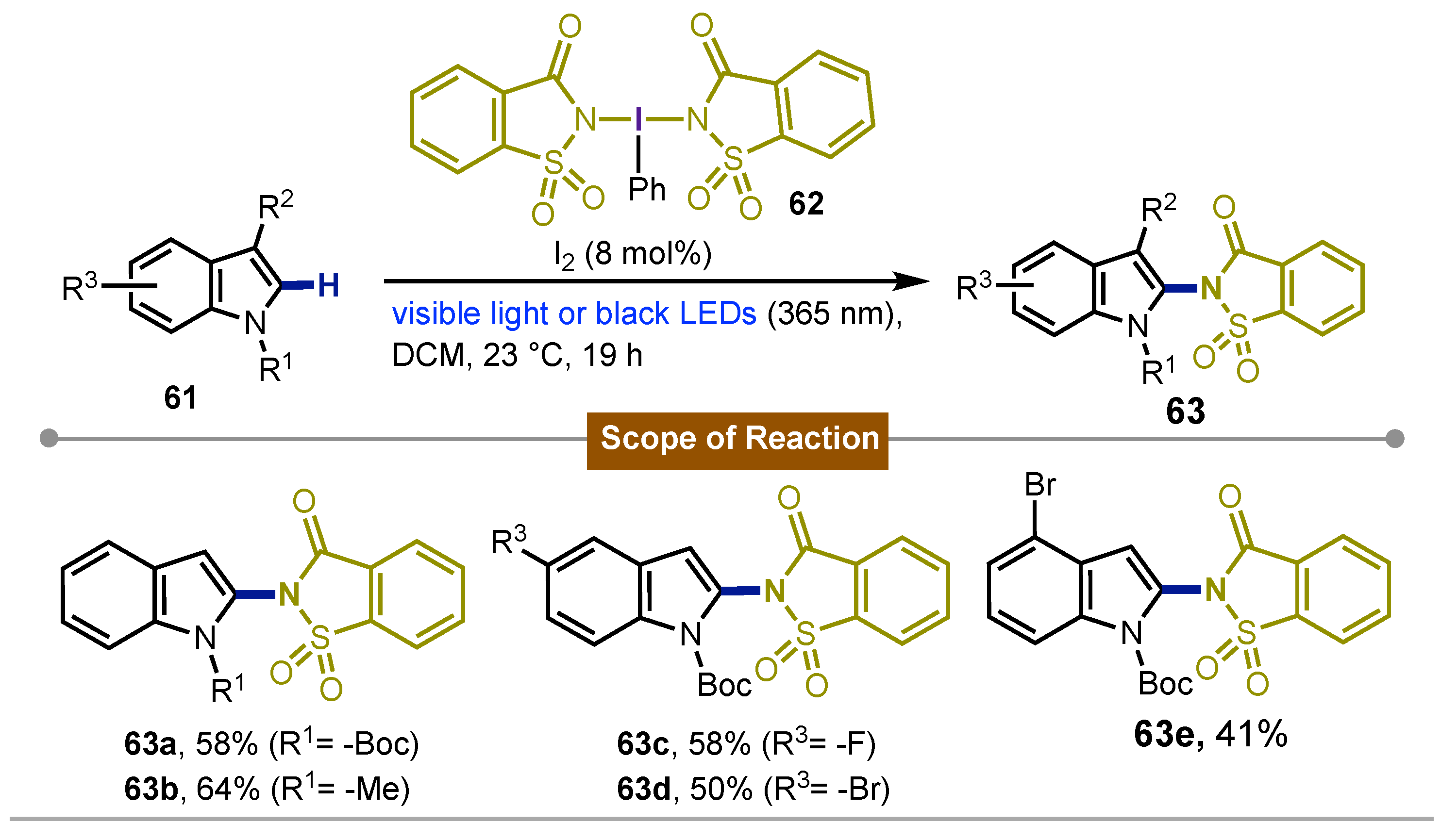

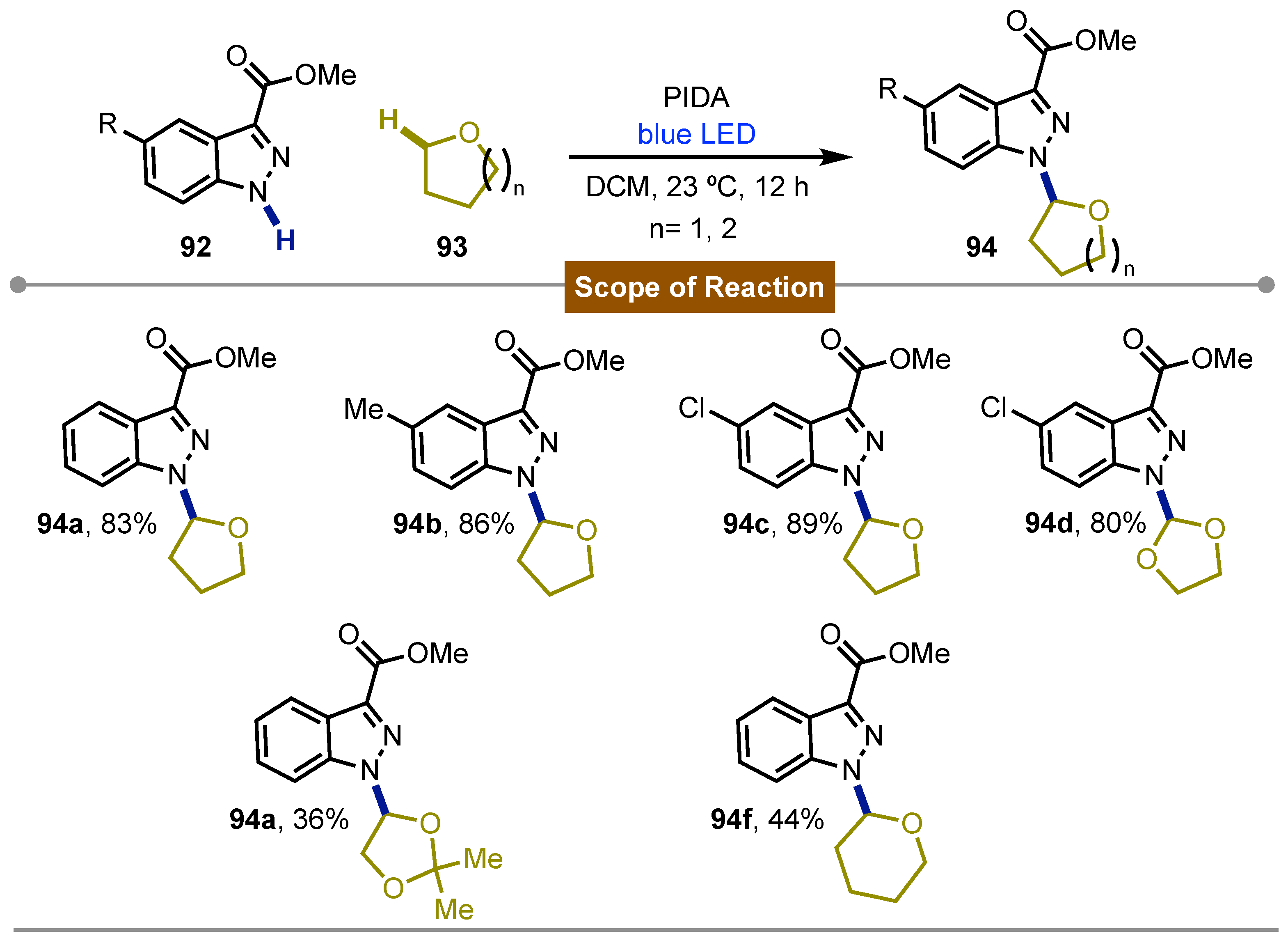

- Han, X.; Yue, W.; Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, J. Iodine(III)-Mediated Photochemical C–H Azolation. Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 9305–9310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

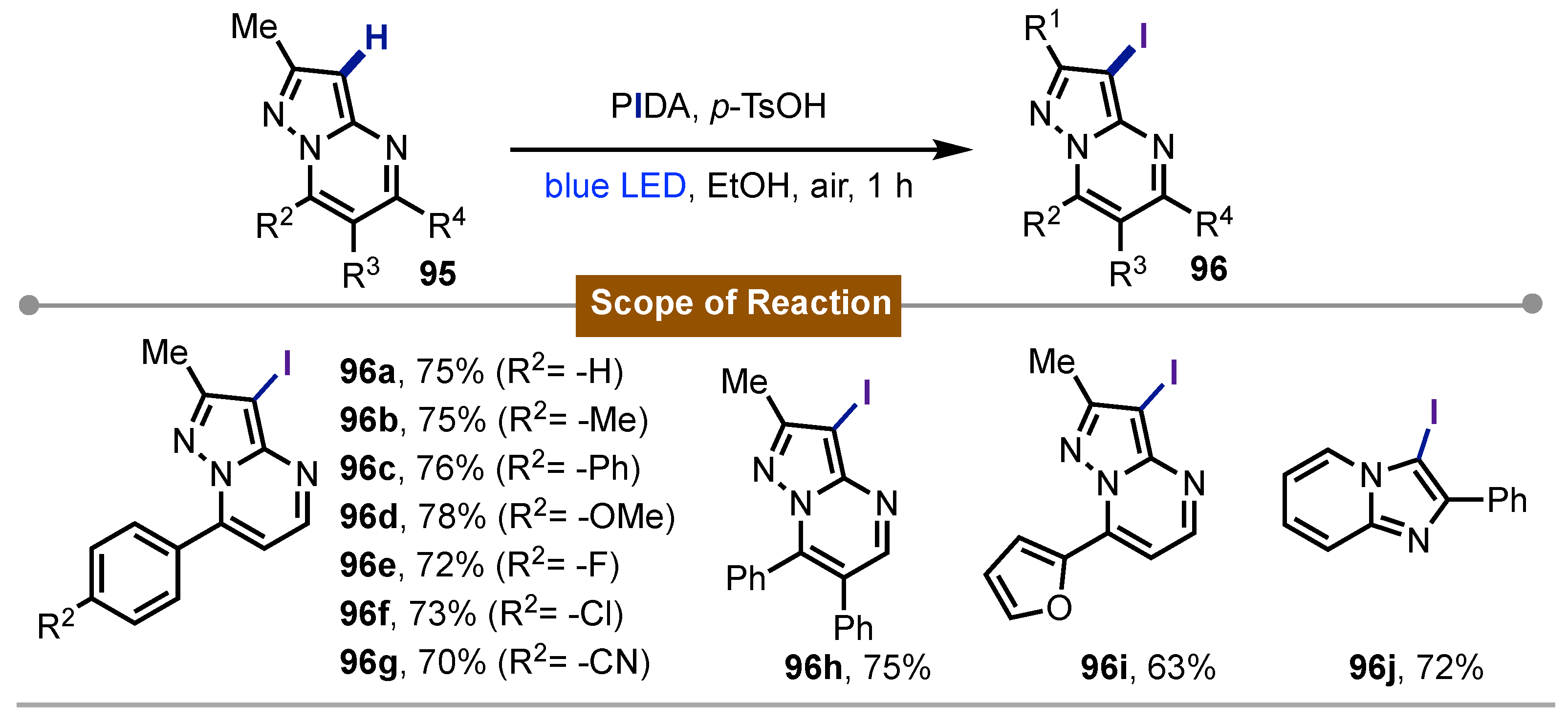

- Paul, S.; Das, S.; Choudhuri, T.; Sikdar, P.; Bagdi, A. K. PIDA as an Iodinating Reagent: Visible-Light-Induced Iodination of Pyrazolo[1,5-a]Pyrimidines and Other Heteroarenes. Chem. Asian J. 2024, e202401101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

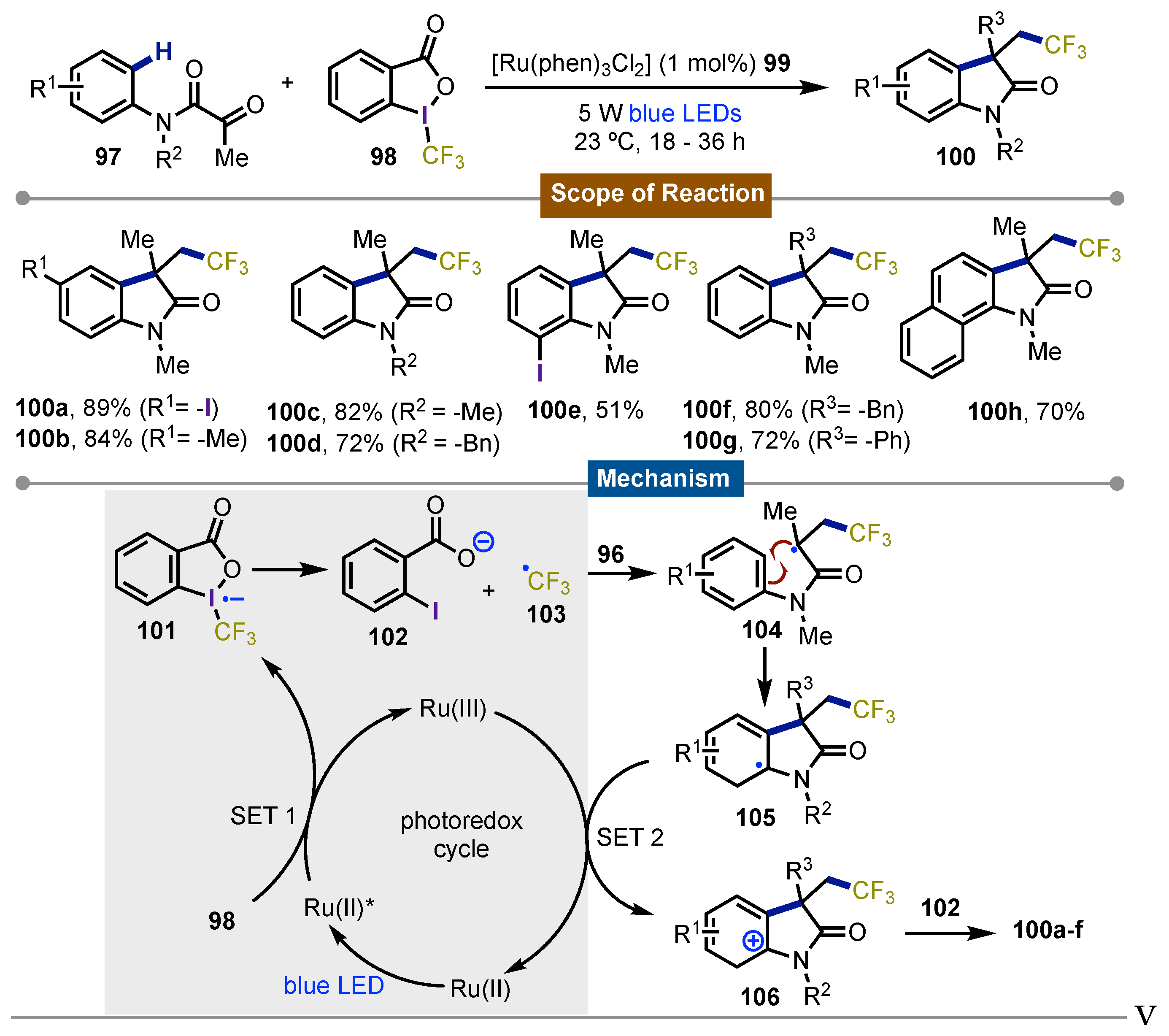

- Xu, P.; Xie, J.; Xue, Q.; Pan, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. Visible-Light-Induced Trifluoromethylation of N-Aryl Acrylamides: A Convenient and Effective Method To Synthesize CF3-Containing Oxindoles Bearing a Quaternary Carbon Center. Chem. Eur. J 2013, 19, 14039–14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

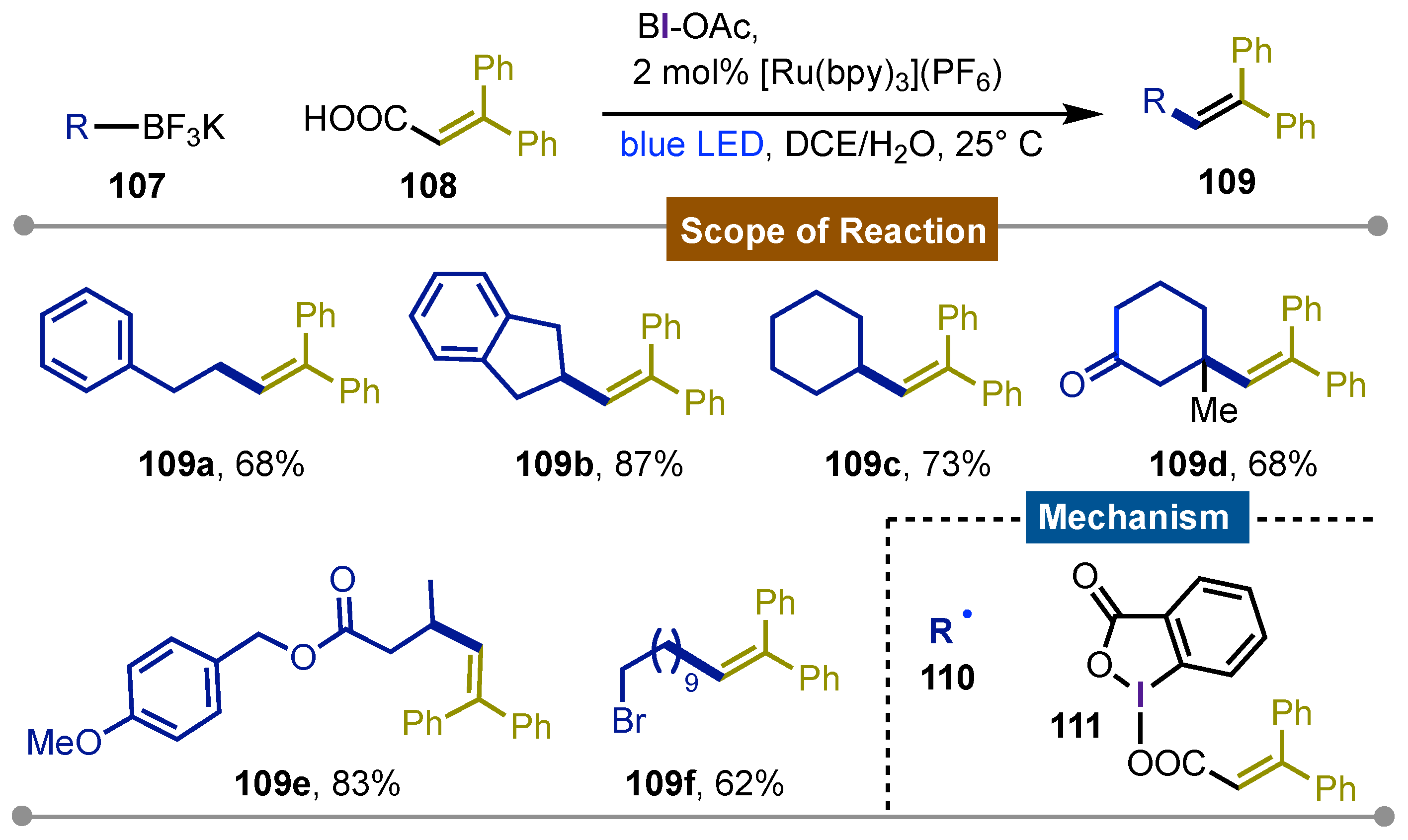

- Huang, H.; Jia, K.; Chen, Y. Hypervalent Iodine Reagents Enable Chemoselective Deboronative/Decarboxylative Alkenylation by Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem 2014, 127, 1901–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

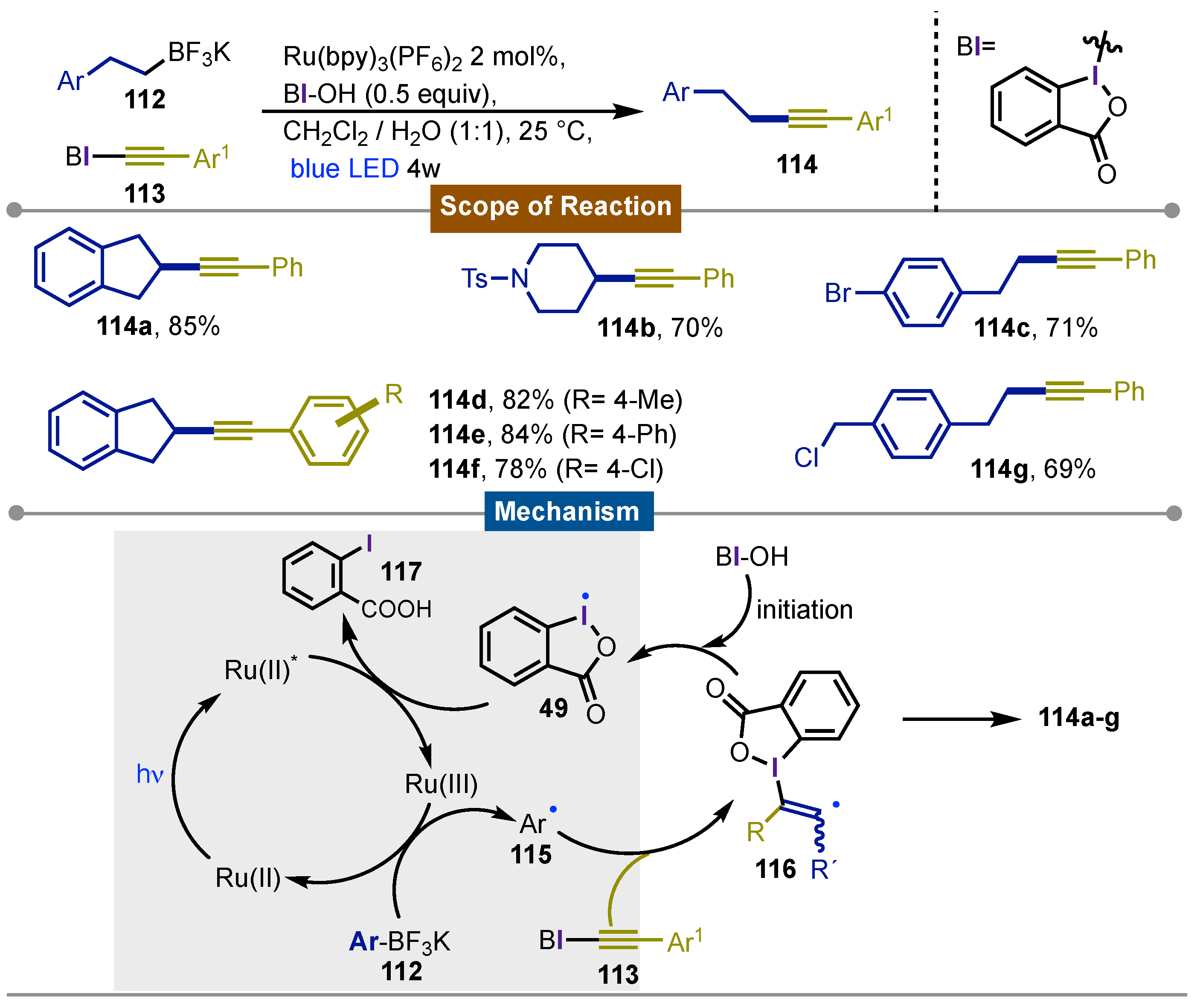

- Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; Gong, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Visible-Light-Induced Chemoselective Deboronative Alkynylation under Biomolecule-Compatible Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2014, 136, 2280–2283. [CrossRef]

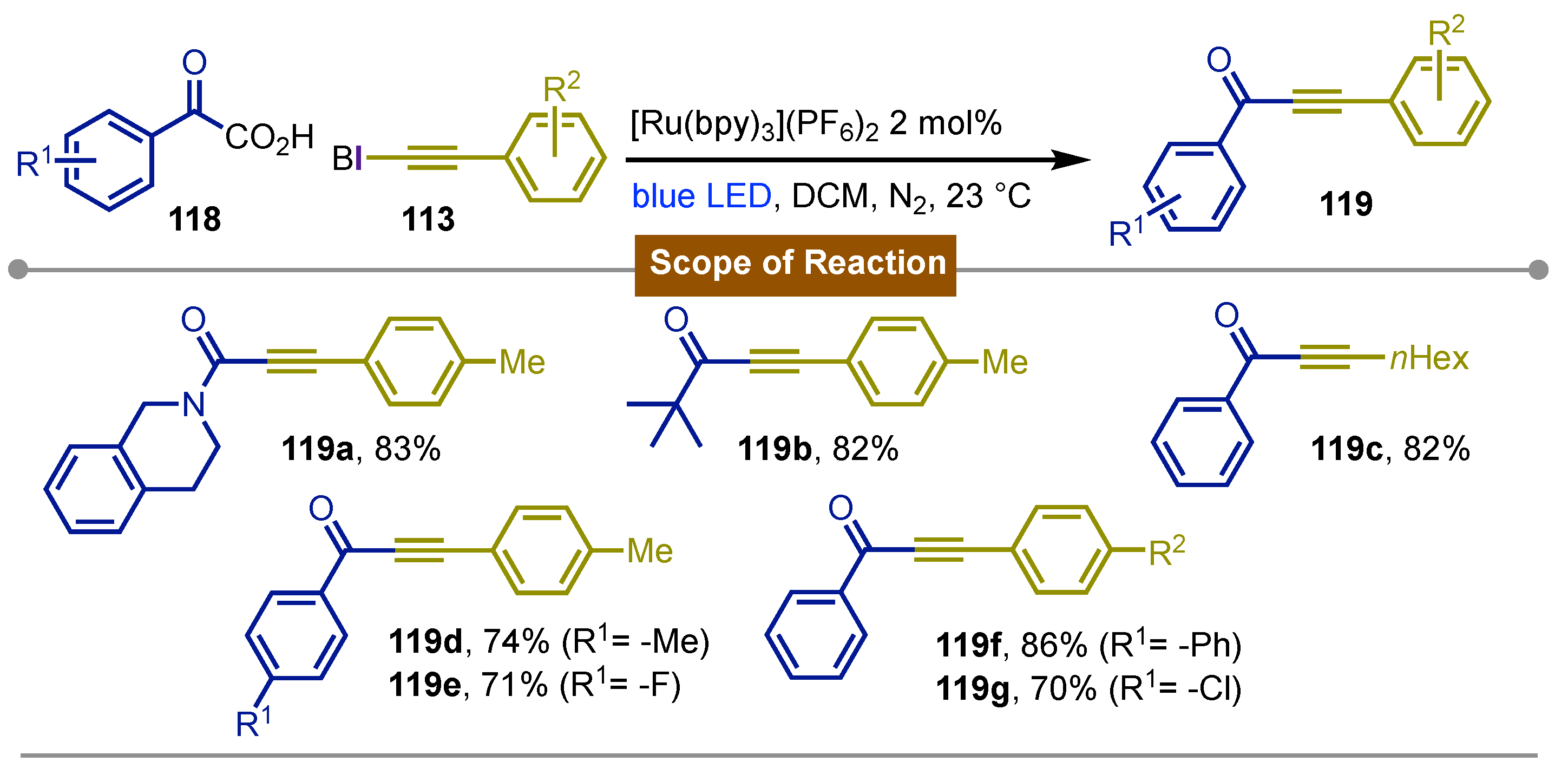

- Huang, H.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Y. Dual Hypervalent Iodine(III) Reagents and Photoredox Catalysis Enable Decarboxylative Ynonylation under Mild Conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 7872–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

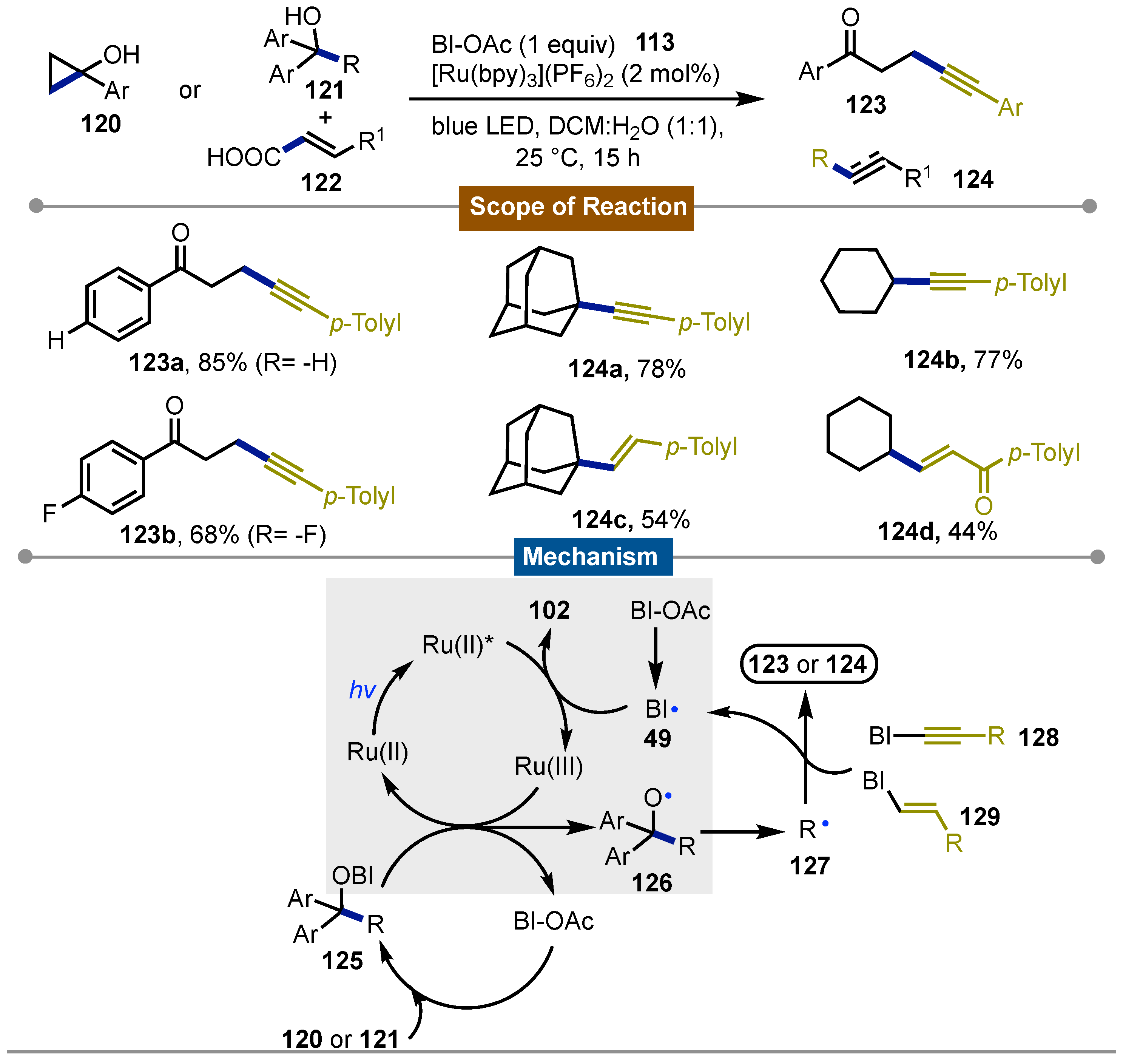

- Jia, K.; Zhang, F.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y. Visible-Light-Induced Alkoxyl Radical Generation Enables Selective C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Cleavage and Functionalizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 1514–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

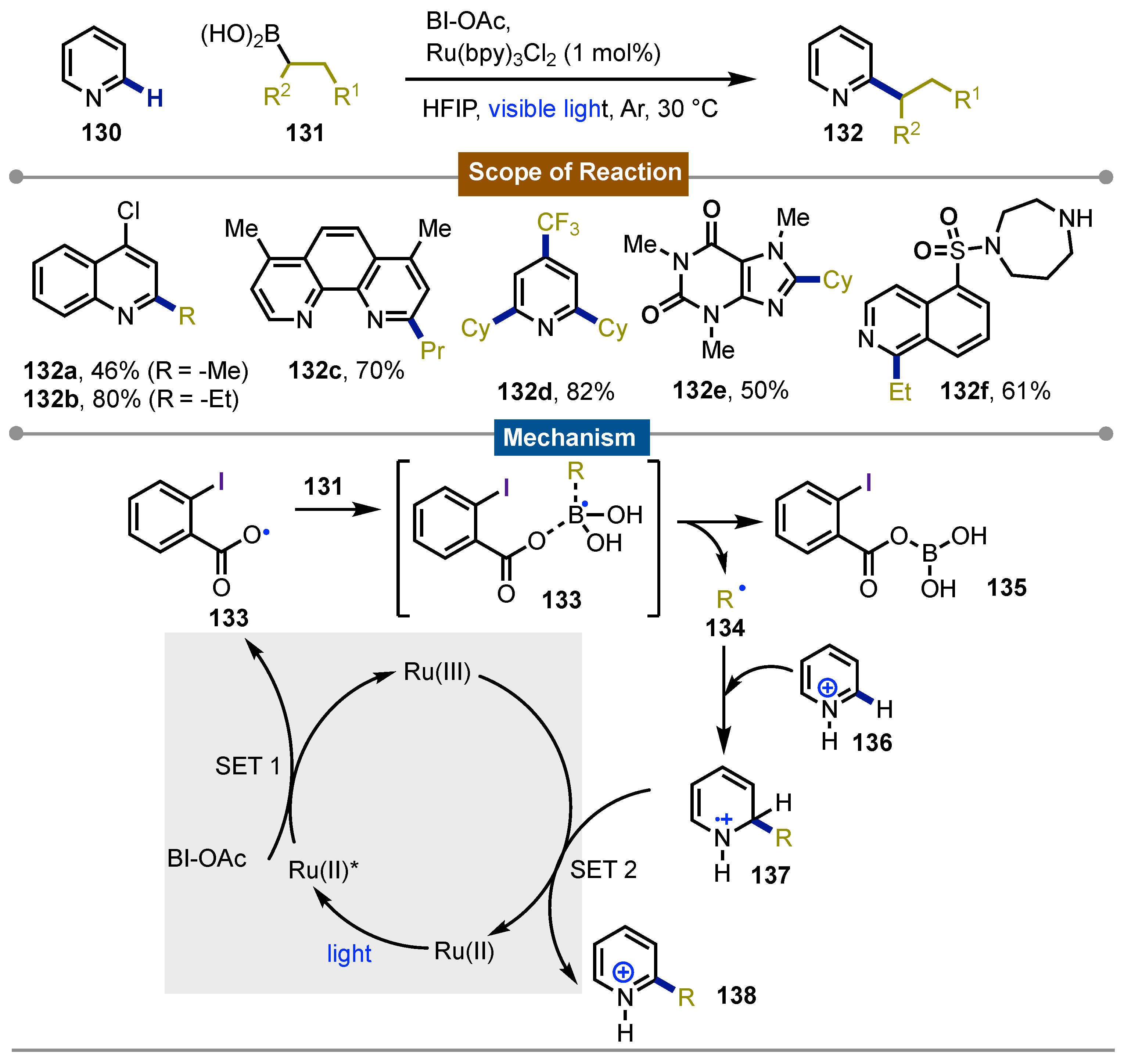

- Li, G.-X.; Morales-Rivera, C. A.; Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; He, G.; Liu, P.; Chen, G. Photoredox-Mediated Minisci C–H Alkylation of N-Heteroarenes Using Boronic Acids and Hypervalent Iodine. Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 6407–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, K.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y. Selective Carbonyl−C(Sp3) Bond Cleavage To Construct Ynamides, Ynoates, and Ynones by Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem 2017, 129, 2518–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Herraiz, A. G.; del Hoyo, A. M.; Suero, M. G. Generating carbyne equivalents with photoredox catalysis. Nature 2018, 554, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

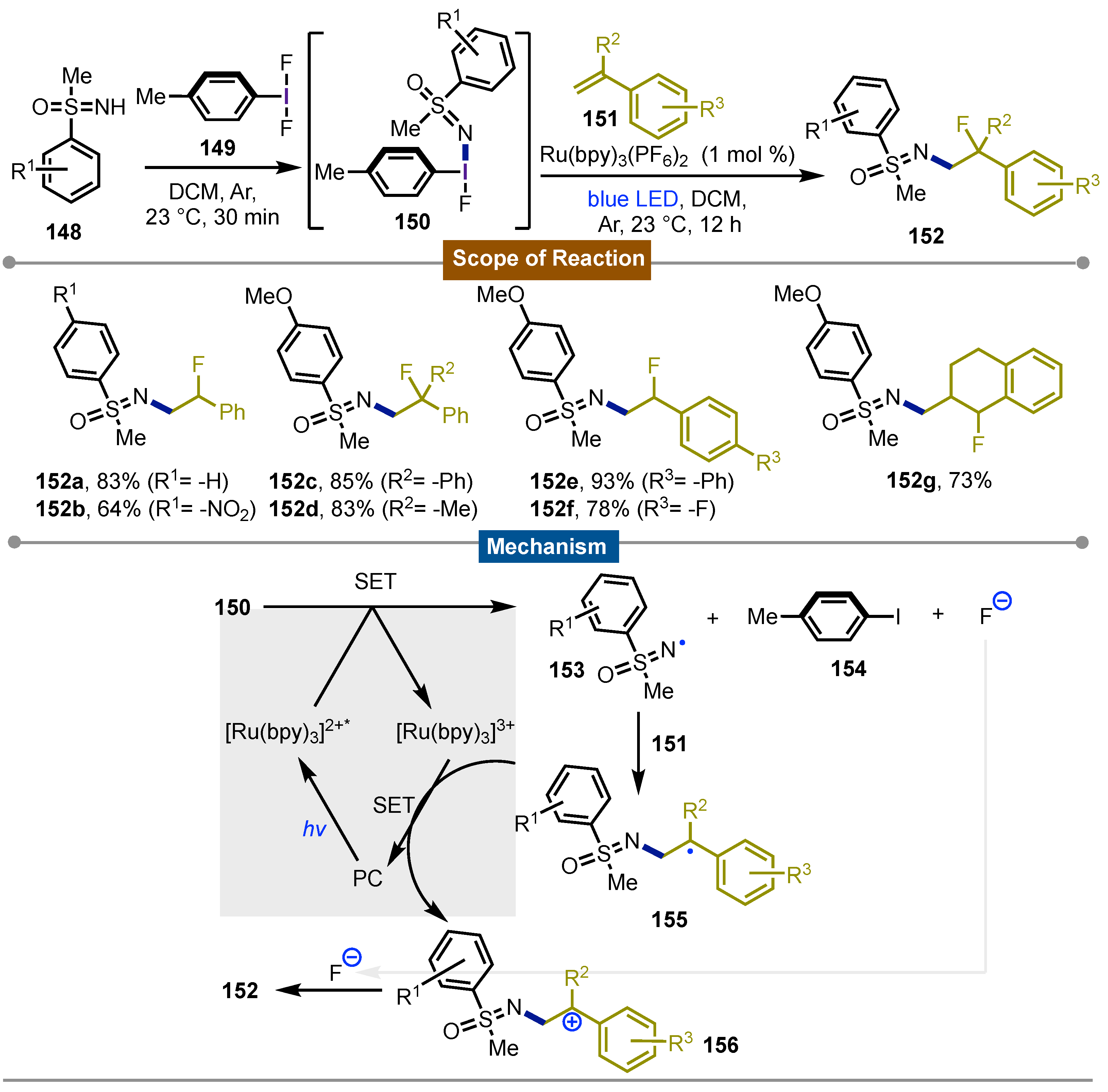

- Wang, C.; Tu, Y.; Ma, D.; Bolm, C. Photocatalytic Fluoro Sulfoximidations of Styrenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2020, 59, 14134–14137. [CrossRef]

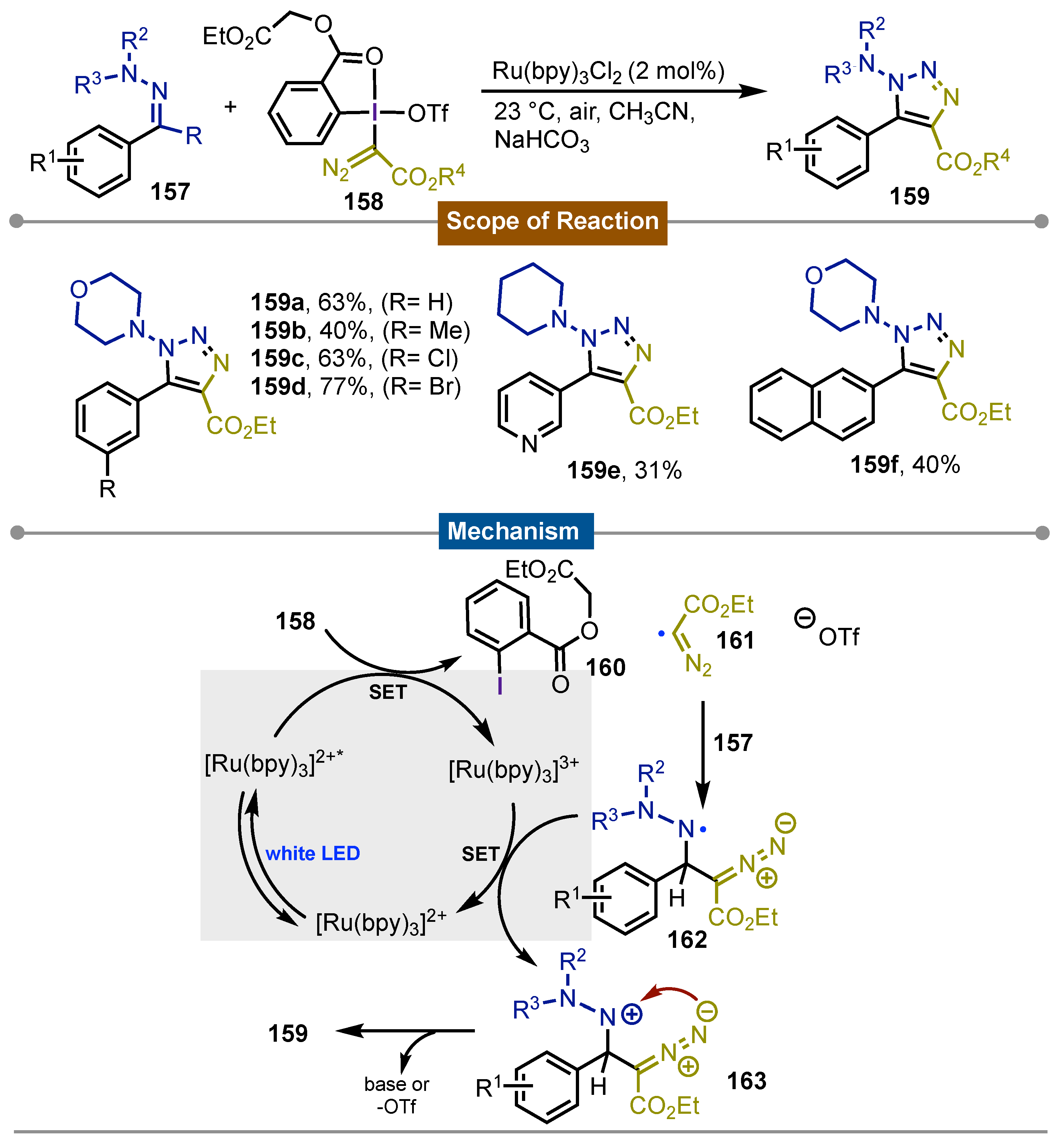

- Dong, J.-Y.; Wang, H.; Mao, S.; Wang, X.; Zhou, M.-D.; Li, L. Visible Light-Induced [3+2] Cyclization Reactions of Hydrazones with Hypervalent Iodine Diazo Reagents for the Synthesis of 1-Amino-1,2,3-Triazoles. Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis 2021, 363, 2133–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

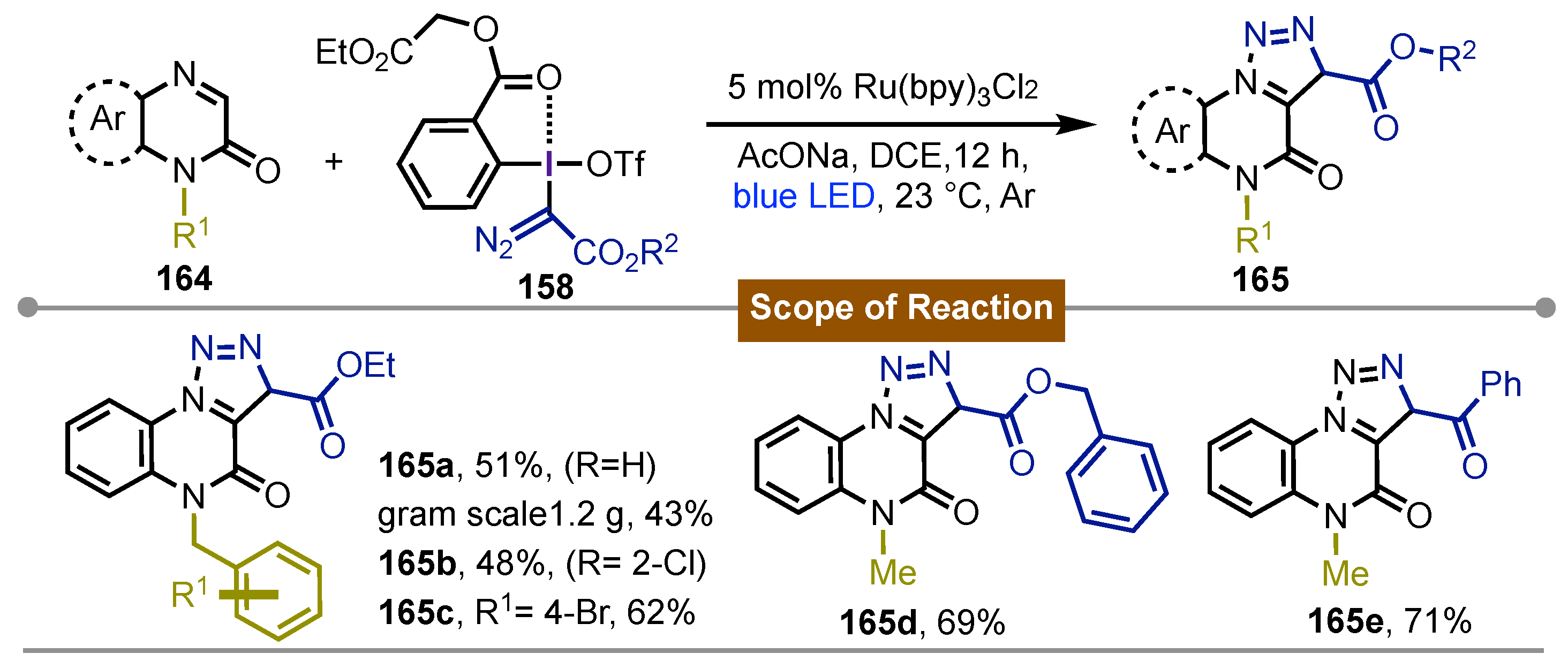

- Wen, J.; Zhao, W.; Gao, X.; Ren, X.; Dong, C.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Li, J. Synthesis of [1,2,3]Triazolo-[1,5-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-ones through Photoredox-Catalyzed [3 + 2] Cyclization Reactions with Hypervalent Iodine(III) Reagents. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2022, 87(6), 4415–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

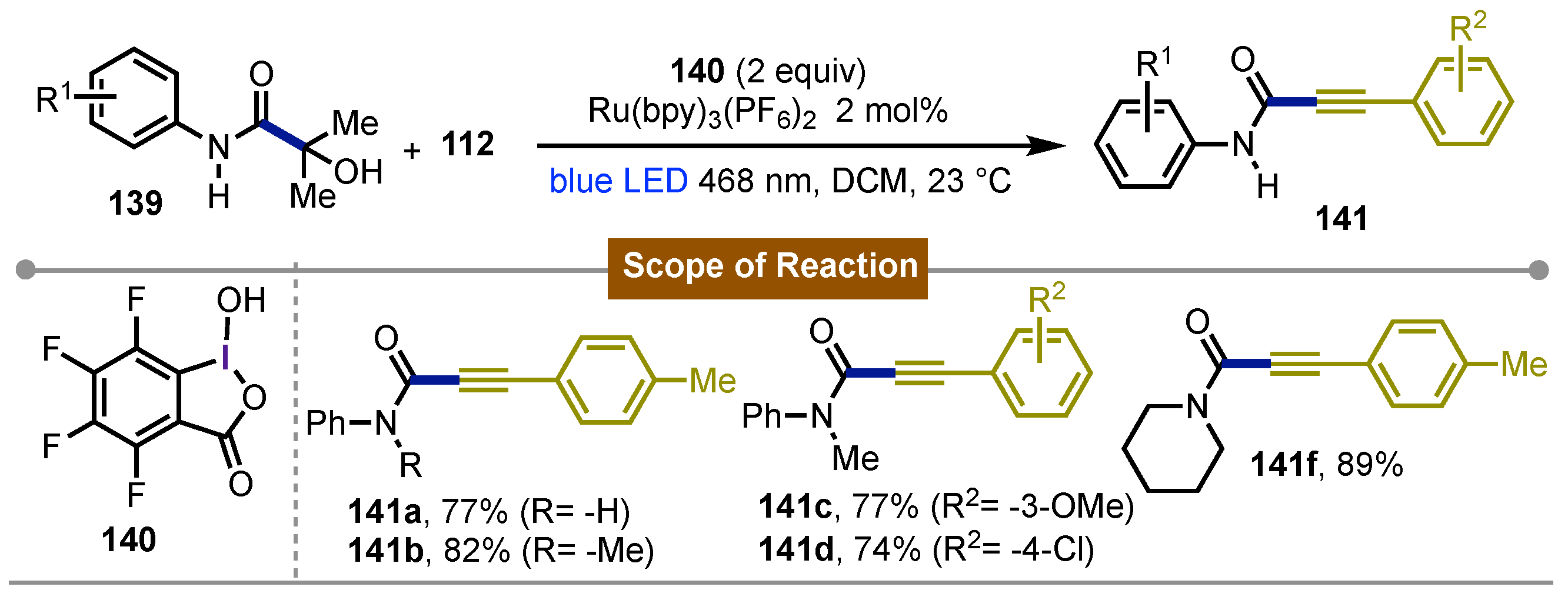

- Pan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zou, P.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. Hypervalent Iodine Reagents Enable C(sp2)–H Amidation of (Hetero)Arenes with Iminophenylacetic Acids. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 6681–6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

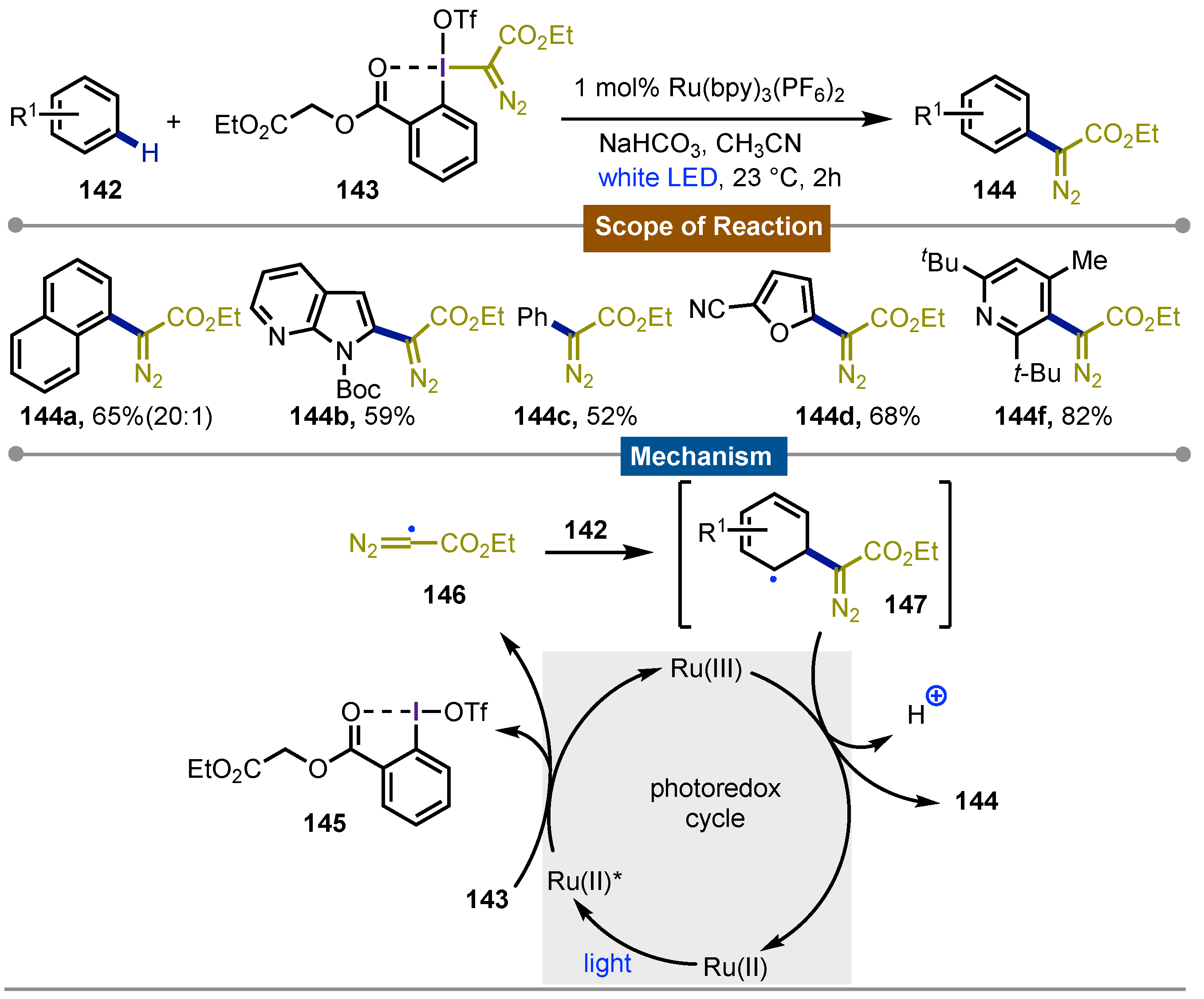

- He, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Rolka, A. B.; Suero, M. G. Alkoxy Diazomethylation of Alkenes by Photoredox-Catalyzed Oxidative Radical-Polar Crossover. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2024, 146, 12294–12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Xu, P.; Li, H.; Xue, Q.; Jin, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. A Room Temperature Decarboxylation/C–H Functionalization Cascade by Visible-Light Photoredox Catalysis. Chem. Commun 2013, 49, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).