1. Introduction

Process monitoring is a cornerstone of manufacturing, ensuring product quality and operational efficiency. Traditionally, this task has been performed by human operators, but reliance on manual oversight introduces inherent limitations, such as susceptibility to errors, subjectivity, fatigue, and a constrained ability to process large volumes of information in fast-paced environments [

1,

2,

3]. These challenges underscore the need for more advanced, automated systems to meet the demands of modern manufacturing.

The emergence of large-scale data availability and increased computational resources has paved the way for data-driven models to transform manufacturing operations [

4,

5,

6]. These models have enabled the emergence of smart manufacturing systems that enhance process monitoring and quality assurance practices [

7]. Within the broader scope of manufacturing, data-driven algorithms play a pivotal role in optimizing processes, improving resource efficiency, and reducing costs. Beyond production lines, artificial intelligence (AI) has become integral to supply chain management by providing precise demand forecasting, inventory control, and disruption mitigation, thereby fostering resilient and efficient operations [

8,

9]. AI also enhances labor productivity, identifies errors, supports informed decision-making, manages risks, and facilitates data-driven strategic initiatives. These capabilities collectively highlight the transformative potential of AI in driving innovation and strategic growth in the manufacturing industry [

10,

11].

The applications of AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), are far-reaching in the manufacturing domain. For example, data analytics on sensor and equipment data facilitates predictive maintenance, enabling manufacturers to proactively identify and resolve issues, minimize downtime, and prevent unexpected equipment failures. Additionally, integrating system data with ML models supports product design, manufacturability analysis, and quality control by enabling rapid and accurate defect detection, ultimately improving product quality and reducing waste [

12]. The capabilities of DL, with its sophisticated neural network architectures, further enhance manufacturing by automatically identifying trends and detecting anomalies [

1]. However, the success of such models depends heavily on the availability of high-quality, labeled datasets, which are often costly and labor-intensive to collect.

Among DL techniques and models, YOLOv8 has emerged as a state-of-the-art solution for instance segmentation, particularly suited to defect detection in manufacturing environments. With its advanced architecture, including CSPDarknet53-based cross-stage partial connections and anchor-free detection mechanisms, YOLOv8 ensures efficient object recognition and robust performance in diverse and challenging industrial settings [

19,

20,

21]. YOLOv8 self-attention mechanism further refines its ability to focus on relevant features, ensuring robust performance even in the presence of occlusions or complex backgrounds [

22]. These advancements make YOLOv8 an ideal choice for addressing the challenges of defect detection in manufacturing.

Despite these advancements, the success of deep learning models relies heavily on high-quality, labeled datasets, which are costly and time-consuming to acquire. Synthetic data offers a promising solution by mimicking real-world data, capturing the nuances required for training deep learning models. Synthetic datasets provide consistency, diversity, and scalability, which are critical for developing robust models for defect detection and other manufacturing tasks [

13]. However, challenges persist in ensuring the representativeness of synthetic data and bridging the gap between synthetic and real-world datasets [

14]. For instance, the inherently two-dimensional nature of many synthetic datasets, created through superimposed images on varied backdrops, often falls short in accurately representing real-world manufacturing conditions [

23,

24]. Another significant challenge is modeling the stochastic and deterministic behaviors of real-world systems, which can impact the reliability of trained models [

25]. Furthermore, limited randomization in synthetic data generation, such as variations in lighting, camera angles, spatial relationships, and defect diversity, reduces generalizability across real-world scenarios [

26,

27].

Efforts to address these limitations include integrating domain randomization techniques and innovative approaches such as rendering 3D models using tools like Blender. For example, Manettas et al. [

24], demonstrated how incorporating variable lighting conditions and diverse backdrops improves the robustness of neural networks trained on synthetic data. These techniques highlight the potential of synthetic data to enhance defect detection while addressing the need for greater realism and diversity in training datasets. Using Blender to render objects onto random backdrops from a vast image dataset provides training robust neural networks capable of discerning context [

28].

This study aims to address these challenges by developing a comprehensive pipeline for defect detection in manufacturing. The pipeline leverages YOLOv8 for instance segmentation and integrates advanced synthetic data generation techniques, including automated labeling and randomization strategies, to enhance model accuracy and generalizability. By bridging the gap between synthetic and real-world data, the proposed framework seeks to improve the reliability of deep learning models in dynamic manufacturing environments, ultimately contributing to the broader vision of smart manufacturing within Industry 4.0.

2. Methods

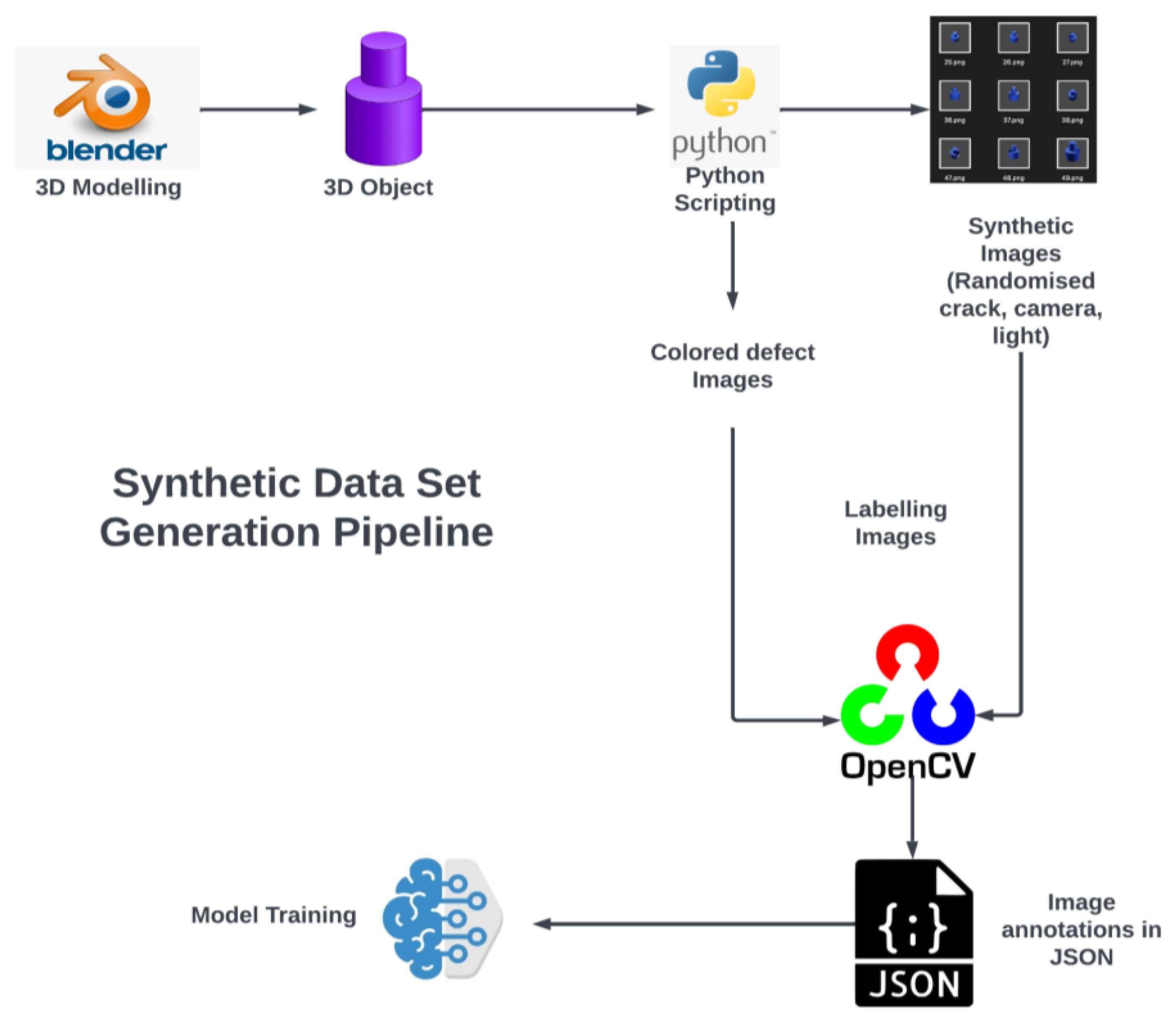

In this section, a detailed overview of the methodology employed in this study is discussed. The primary goal of this study is to propose an approach for creating a pipeline to generate an annotated dataset specifically designed for defect identification using deep learning object detector models. To achieve this, we propose a methodology that combines the use of game engines for data generation with Python programming for scene manipulation and data annotation. The steps and a general overview of the complete proposed pipeline is depicted in Error! Reference source not found..

Figure 1.

Proposed Approach for Synthetic Data Set Pipeline.

Figure 1.

Proposed Approach for Synthetic Data Set Pipeline.

2.1. Object Creation

To generate the desired defective parts, the first step is to create objects that accurately represent the complexity found in real-world manufacturing processes. For this purpose, we use Blender [

34] as the preferred tool for designing 3D models, which will be utilized to setup scenes for defect identification in manufacturing applications.

Blender is the preferred tool due to its numerous advantages. As a free, open-source software, it offers a comprehensive set of features, including 3D modeling, rendering, material physics, and rigging. Additionally, its robust compatibility with Python scripting makes it an effective resource for research, especially when tasks like object creation and scene manipulation are needed to generate various scenarios and simulations.

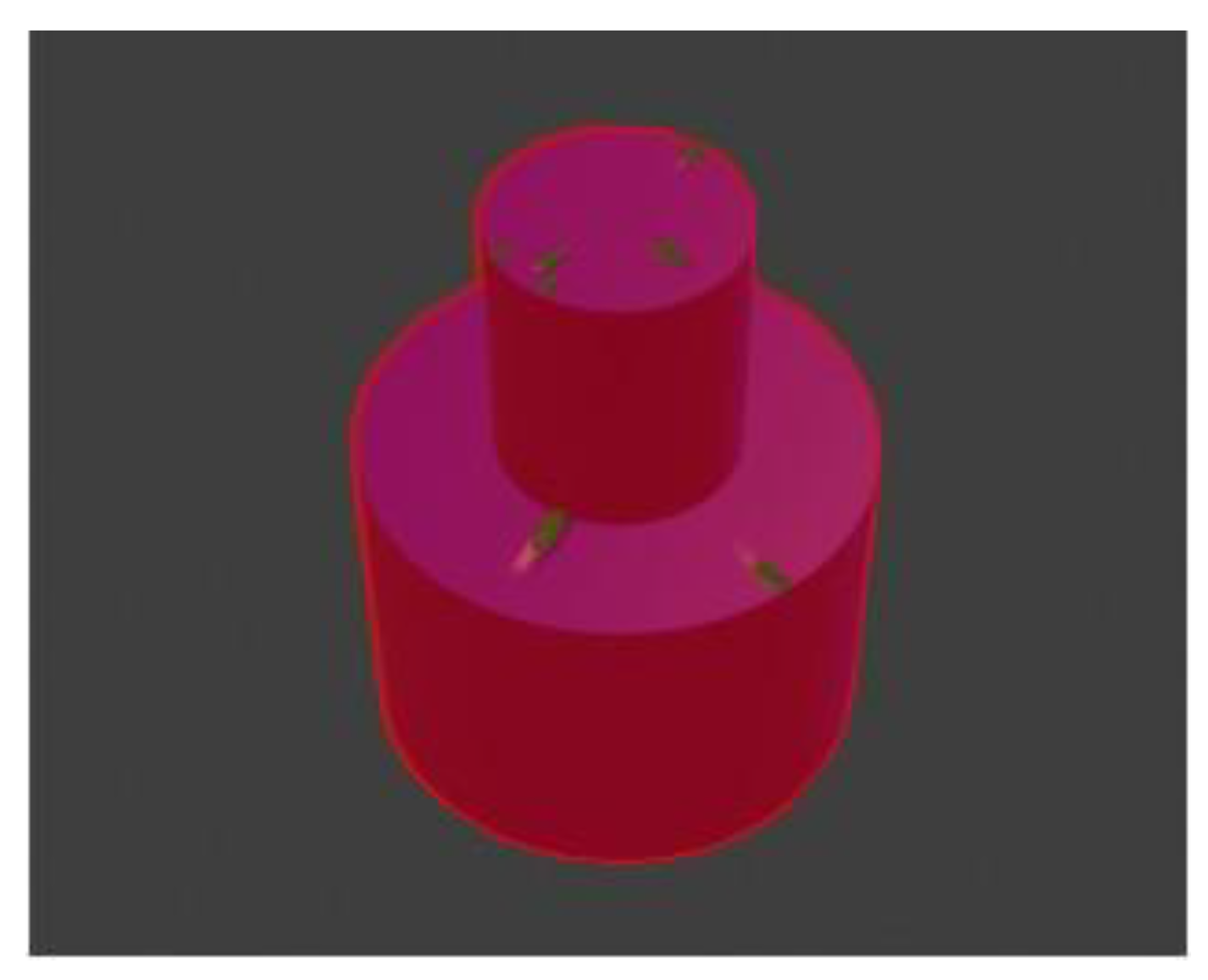

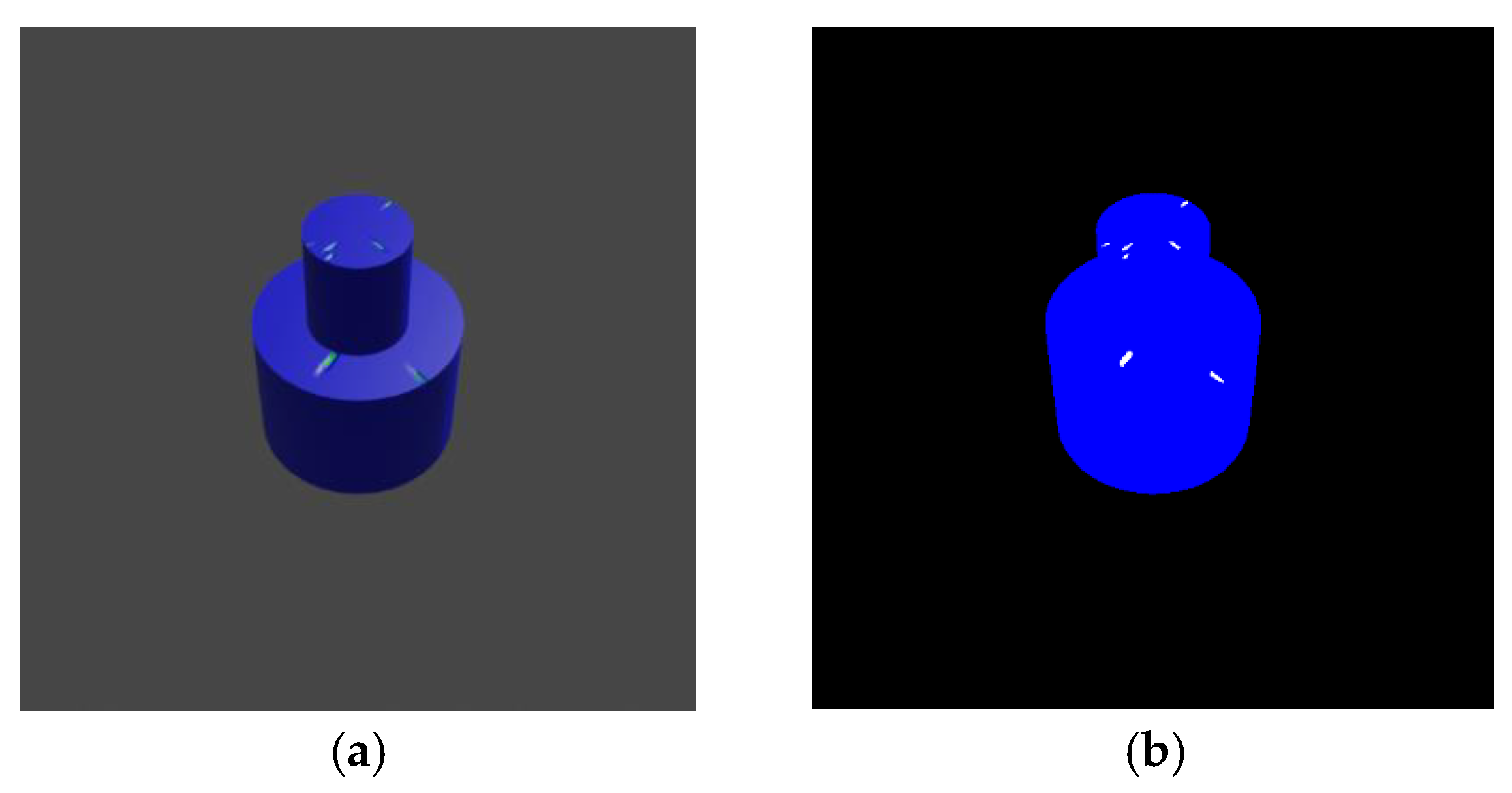

The pipeline for synthetic data generation process was initiated by constructing a basic object configuration as a case study utilizing Blender. The object consists of a cylinder positioned on top of another cylinder. Following the object graphic creating in Blender, we obtained the actual object using a 3D printer. The constructed object's appearance in the Blender scene and its actual realization after being 3D printed are shown in parts (a), and (b) in Error! Reference source not found. respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Object designed in Blender; (b) Object that is 3D printed.

Figure 2.

(a) Object designed in Blender; (b) Object that is 3D printed.

2.2. Synthetic Data Generation with Automated Scene Variation

Having the basic object created, the next step is to create a wide array of photos that represent process variations in real world processes. Therefore, our approach includes implementation of random changes in lighting conditions and camera angles to address this challenge. To accomplish this, we used Python programming within the Blender framework. The Python script we developed is capable of generating the necessary variations in camera angles and lighting conditions to ensure the deep learning models encounter diverse scenarios, enabling them to generalize effectively for the defect detection task.

2.2.1. Alteration in Camera Angles

The Python script enabled the movement of a virtual camera in Blender scene along a circular track around the main object. To incorporate variation, we employed a randomization technique to assign values to the x, y, and z coordinates between predetermined intervals. This method allowed the camera to collect shots from different distances, viewpoints, and orientations while keeping the main subject at the center of the frame.

2.2.2. Alteration in Lighting Conditions

While keeping the first light source stationary to maintain a consistent baseline, the second light source was programmed to move randomly within a predefined range, mimicking the dynamic and unpredictable lighting conditions that can occur in real-world settings. This random movement, similar to the randomization applied to the camera, introduced varying shadow patterns and intensities across the object. By simulating diverse interactions between light and shadow, this approach closely replicated the complex visual conditions encountered in real-world environments. These variations not only enhanced the realism of the synthetic dataset but also provided critical training scenarios for the deep learning models, ensuring they are better equipped to handle diverse and challenging lighting conditions during real-world deployment.

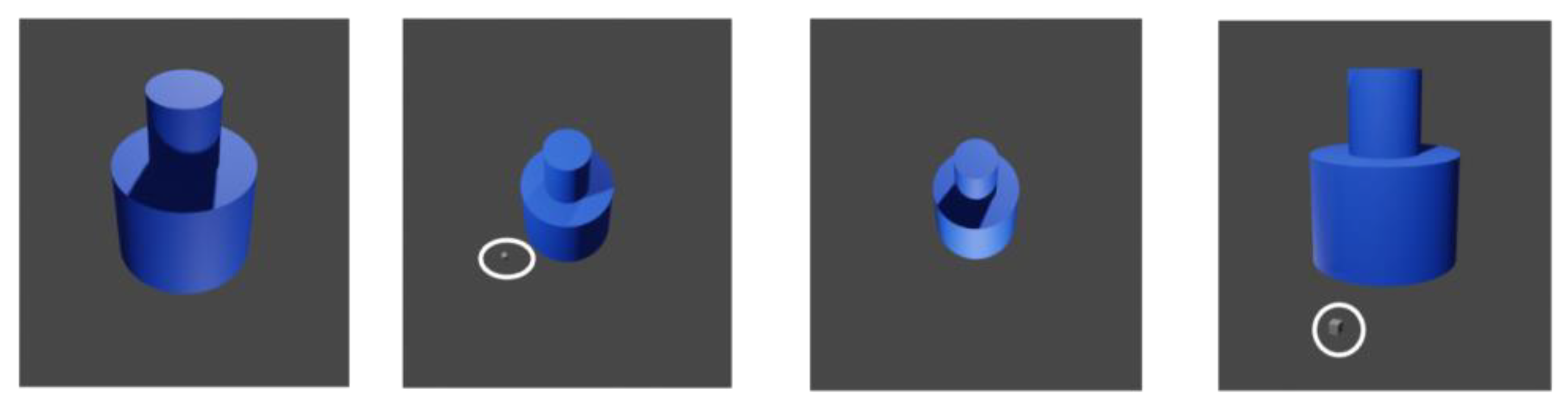

2.2.3. Final Object Configurations

To establish a frame of reference, we incorporated a cube into the scene, indicated by white circles in

. This cube served as a visual anchor, providing a consistent point of comparison across the series of generated images. By maintaining this reference object, we were able to assess the impact of randomization techniques more effectively.

illustrates the outcomes of the image generation process, where the randomization methods outlined in

Section 2.2.1 and

Section 2.2.2 were applied to create diverse variations in lighting and camera angles.

Figure 3.

Images obtained from the automated script.

Figure 3.

Images obtained from the automated script.

2.3. Defect Generation

To simulate manufacturing defects accurately, we generated a range of flawed objects using Blender to represent typical defects encountered in industrial processes. Specifically, the extrusion tool in Blender was employed to create fractures in cylindrical objects, simulating cracks and imperfections. By selecting specific faces on the cylinder model and applying an inward extrusion, we successfully produced a visible, realistic crack pattern. This technique allowed us to manipulate the geometry precisely, creating a visually accurate representation of a defect. By varying the selection of faces and adjusting the extrusion depth, we further enhanced the diversity of defect types, achieving patterns that closely resemble those seen in real-world manufacturing anomalies.

A significant challenge in this process was introducing controlled randomness to the cracks, which is essential for simulating naturally occurring defects. This required a detailed approach to locating the precise areas where fractures would appear, as well as limiting the extent of the damage to maintain structural coherence. Achieving a balance between randomness and realism in the flaw distribution ensures that each defect appears unique yet reproducible for analysis. Additionally, to enhance the defect’s visibility from the camera’s perspective, adjustments were made to the object’s orientation and flaw depth. This step is crucial for ensuring that defects are easily identifiable in automated visual inspections or by deep learning models used in quality control.

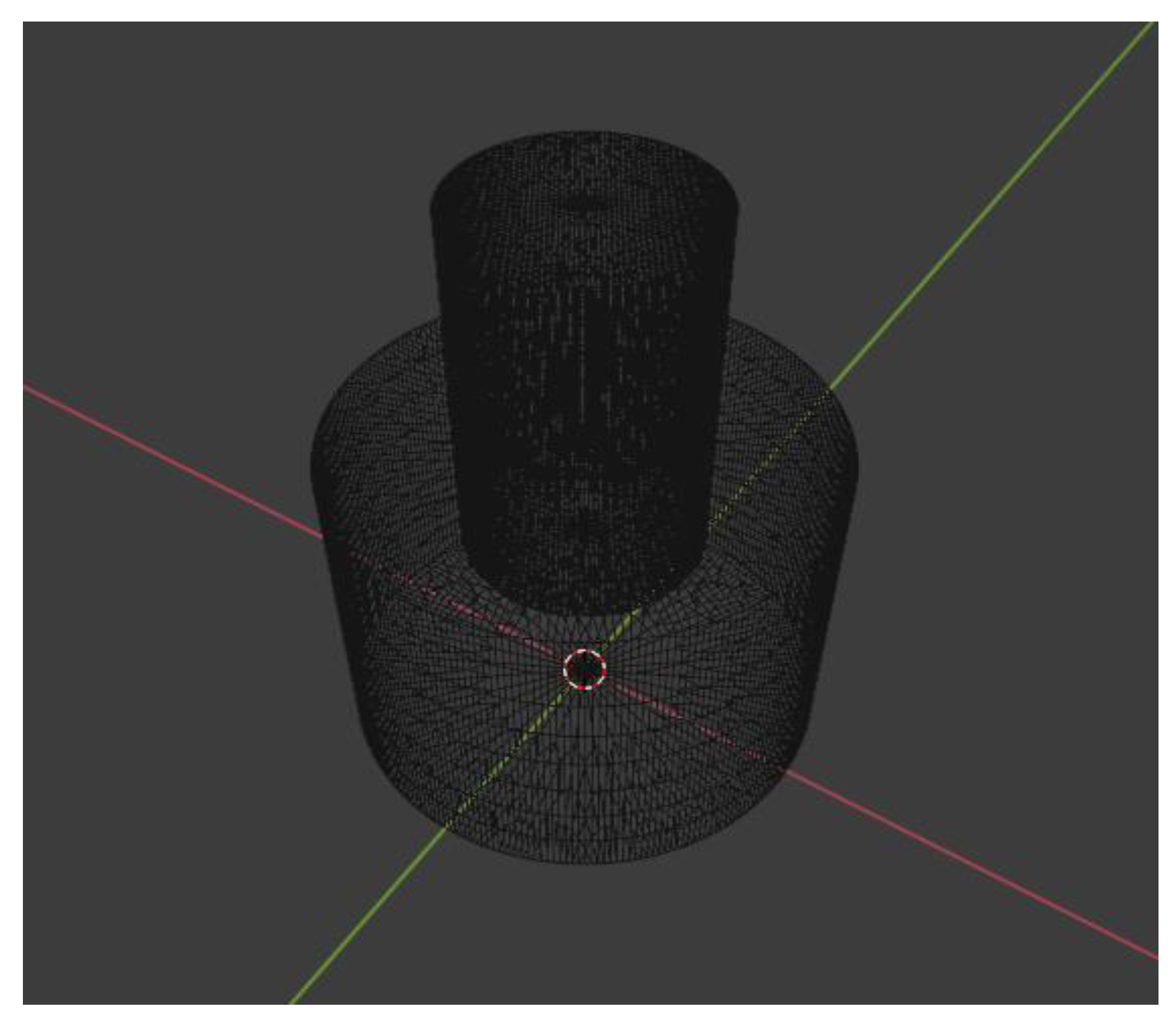

Upon examination, we found that the most efficient method to introduce these defects was through direct face selection on the cylinder’s wireframe model in Blender. The wireframe, depicted in Error! Reference source not found., provides a clear outline of the object’s geometry, facilitating precise selection of areas to modify. This visualization aids in planning and executing targeted alterations, allowing for defect creation while preserving the object’s fundamental shape. By working directly with the wireframe, we achieved better control over defect placement, enhancing the overall accuracy and reproducibility of our defect simulations.

Figure 4.

Object made from wireframes.

Figure 4.

Object made from wireframes.

This approach not only provides a realistic representation of manufacturing defects, but also lays a foundation for future experimentation with automated defect detection methods in virtual environments, aligning closely with industry needs for high-quality defect simulation.

2.3.1. Randomization in Defect and Scene Setup

In our approach, each face within the wireframe structure of the 3D model is assigned a unique index, enabling precise control over defect placement. To introduce variability and randomness into the defect generation process, we implemented a technique that randomly selects face indices along the XY plane. This approach allows for dynamic selection of faces on the model, where we subsequently apply an inward extrusion to create the visual effect of cracks. By manipulating extrusion depth and adjusting the ratio of inward projection, we achieved a range of defect appearances, simulating variations that might naturally occur in manufacturing processes.

To incorporate the automatic defect generation into our already established camera and lighting script, we connected the two components in a completely integrated manner. The randomization process involves not only selecting different faces but also adjusting the number of faces and the depth of extrusion within a predefined range. By defining minimum and maximum values for both parameters, we ensured controlled yet varied defect patterns. This process simulates realistic damage while maintaining consistency across models for dataset reliability. Integrating this method with our camera and lighting script allowed for seamless defect generation and capture. Each defect is photographed under various angles and lighting conditions, creating diverse visual perspectives of each flaw. This integration and running the pipeline in a loop enables the rapid generation of large datasets representing a wide range of defect appearances and conditions.

Using this automated pipeline, we produced a comprehensive dataset featuring defective objects from multiple camera angles and lighting setups. These variations enhance the dataset’s utility for training and testing deep learning models in visual defect detection. Error! Reference source not found. illustrates a sample of the final output, highlighting a generated defect with visible cracking. This method, combining random face selection with controlled extrusion, establishes a flexible yet structured pipeline for defect simulation, introducing a framework for further research and testing in automated quality control applications. This dataset supports model generalization across different defect types and enhances robustness, offering significant potential for improving defect detection systems in manufacturing environments.

Figure 5.

Object with various cracks as generated defects.

Figure 5.

Object with various cracks as generated defects.

2.4. Dataset Preparation

As detailed in

Section 2.2 and

Section 2.3, we successfully generated a dataset comprising both normal and defective objects using the designed pipeline. This pipeline enables the creation of a wide array of images, achieved by systematically varying camera angles, lighting conditions, and the ratio and depth of defects. Such diversity in the image set is essential for robust model training, as it simulates a broad range of real-world conditions that a defect detection system might encounter in a manufacturing setting.

A crucial next step is preparing the raw dataset for developing deep learning models focused on defect detection and classification. This requires comprehensive annotation of the raw data to identify and localize defects accurately. The conventional approach involves manually labeling each image by drawing bounding boxes around defective regions, a labor-intensive process that is often impractical for large datasets. Given the scale of data required for effective deep learning model training, automating the annotation process became a primary objective.

To address this, we explored methods for automatic annotation, aiming to streamline the data preparation workflow and reduce human effort significantly. Automating this step not only enhances the efficiency of dataset generation but also ensures consistent and accurate labeling, which is crucial for high-performance defect detection models. Implementing an effective automatic annotation process represents a valuable contribution of this study, as it provides a scalable solution for creating annotated datasets tailored for deep learning applications in industrial defect detection. This approach optimizes data readiness and supports the development of models capable of generalizing across various defect types and conditions, thereby enhancing the overall reliability of defect detection systems.

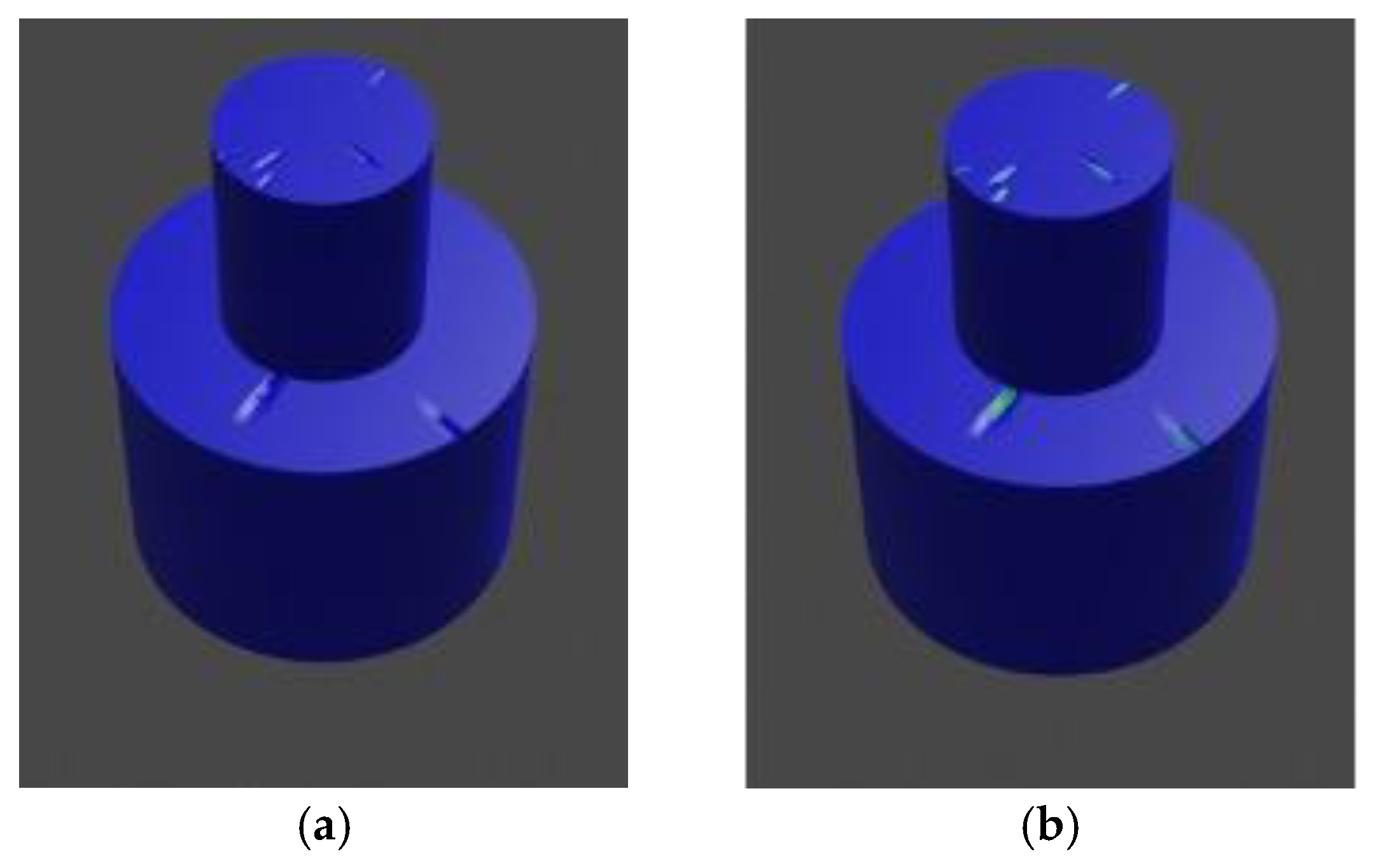

2.4.1. Labeling Challenge

To overcome the challenge associated with manual data labeling, we developed an innovative approach to streamline the process. Specifically, for each image containing a crack defect, we generated a corresponding modified version in which the crack regions were highlighted in green. This strategic alteration enabled precise and systematic identification and labeling of defect areas within the dataset. By employing this method, we ensured a clear visual distinction between defect and non-defect regions, facilitating both automated and manual review processes. The labeled images, where the green-colored areas represent the identified defect regions, are illustrated in Error! Reference source not found. This approach not only enhances labeling efficiency but also supports consistent defect annotation and model training.

Figure 6.

(a) Object with cracks not labeled; (b) Object labeled with green color.

Figure 6.

(a) Object with cracks not labeled; (b) Object labeled with green color.

2.4.2. Automatic Labeling Using OpenCV

To automate the process of image labeling, we developed a Python script utilizing OpenCV's robust image processing capabilities. OpenCV's advanced functions were employed to create an effective color detection algorithm capable of accurately identifying specific colors within images. For images containing crack defects, a range of green hues was carefully defined, with adjustments made to account for variations in lighting and shading to ensure consistent detection across different conditions.

The script efficiently identified the green-colored pixels corresponding to the cracks, enabling precise presentation of defect areas. Additionally, for detecting the cylindrical object within the images, a similar color detection strategy was implemented, focusing on the identification of blue pixels. This dual detection capability ensured that both types of target features, cracks and cylindrical objects, could be accurately recognized within the dataset.

Subsequently, mask images were generated based on the detected pixels to outline the defective areas clearly. To enhance these mask images, OpenCV's dilation functions were applied. This step expanded the boundaries of the detected regions while maintaining their structural integrity, effectively enclosing the regions of interest and enhancing their visibility. These mask images provided an accurate visual representation of the defects, specifically highlighting the affected areas for further analysis. Error! Reference source not found. illustrates the generated mask images, showcasing their effectiveness in representing the identified defects. This approach significantly improved the efficiency and precision of the image labeling process, enabling more reliable analysis and deep learning model training.

3. Data and Deep Learning Modeling Approach

This section provides an overview of the final dataset prepared for modeling, detailing preprocessing steps, data composition, and augmentation methods to ensure robustness. It also presents the deep learning approach, including the chosen architecture, optimization strategies, and training details such as learning rates, loss functions, and regularization techniques. Validation protocols and performance metrics are also outlined to ensure the model's accuracy and reproducibility.

3.1. Generating Final Dataset

This comprehensive dataset now includes both normal and defective objects, with defects present in various locations, proportions, and depths. Each image features alterations in camera angle and lighting conditions, enhancing the dataset’s variability. The use of object masking and a green-coloring approach for automated labeling was essential in ensuring consistent and efficient annotation of defect regions.

To facilitate structured annotations, we utilized the generated mask images (illustrated in

Figure 7-b) to create a

JSON file containing essential metadata for each image. For this process, we referred to online tutorials to construct a custom dataset [

32], adapting Python scripts to suit our specific requirements and integrate with the mask images. The annotation format follows the widely accepted MS COCO dataset structure [

29], including key details such as segmentation data, image ID, category ID, bounding box coordinates, and area measurements. The dataset was labeled for two distinct classes: cracks and objects.

Leveraging an online script to parse MS COCO-style JSON, we processed our generated annotation file alongside the original images to ensure accurate data structuring. One of the outcomes of this comprehensive dataset preparation process is shown in Error! Reference source not found., illustrating the final annotated dataset ready for model training and evaluation.

Figure 8.

Detecting area of interest from JSON.

Figure 8.

Detecting area of interest from JSON.

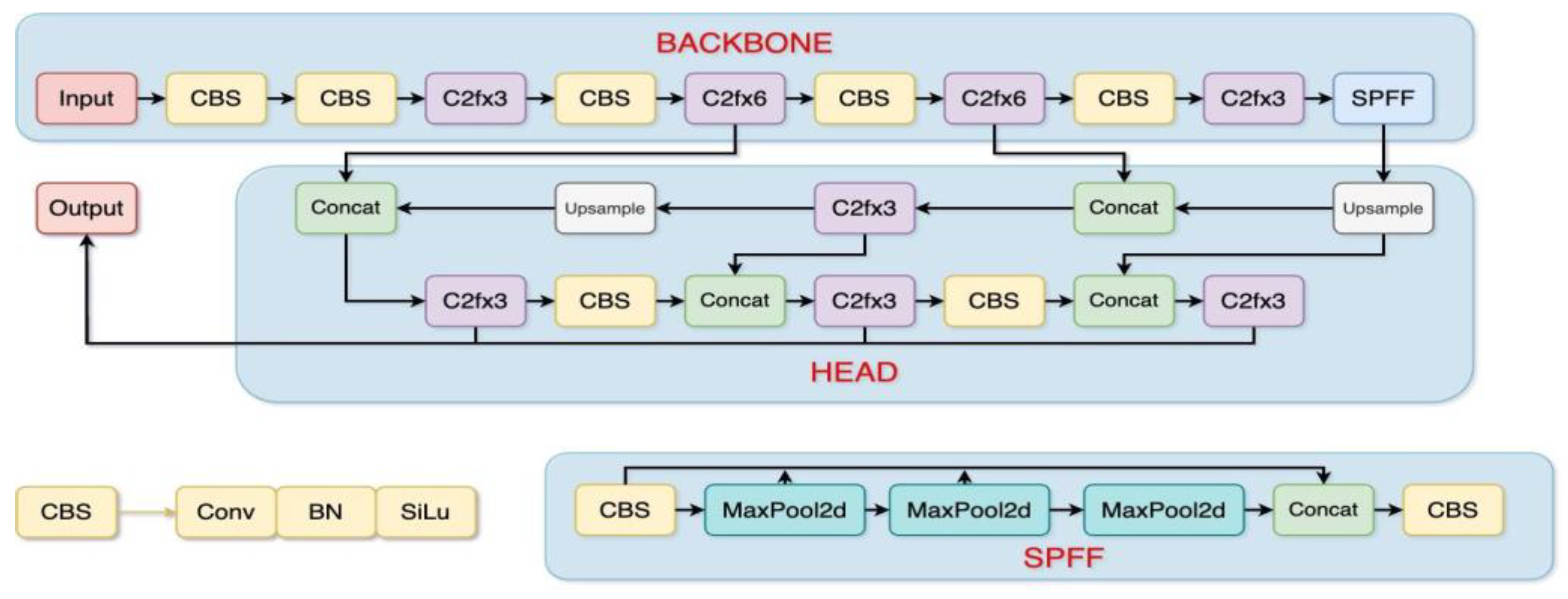

3.2. YOLOv8 Deep Learning Model

As discussed, YOLOv8 incorporates advanced data representation, adaptive attention mechanisms, flexible object recognition, and high-speed processing, making it well-suited for instance segmentation tasks. Its robustness and adaptability across diverse scenarios, without extensive retraining, highlight its practical application potential. Consequently, YOLOv8 was selected for instance segmentation in this study. Error! Reference source not found. provides an overview of the model architecture.

Figure 9.

YOLOv8 model architecture [

34].

Figure 9.

YOLOv8 model architecture [

34].

3.3. Model Preparation and Hardware Requirement

With the dataset prepared in MS COCO JSON format, we proceeded to develop the deep learning model. YOLOv8, however, requires input in the YOLO format. Since our dataset was originally structured in MS COCO format, a widely used standard for labeled image datasets, conversion to YOLO format was necessary. Fortunately, YOLO’s framework includes tools for converting JSON annotations to YOLO format, streamlining this process. Once converted, we created a YAML file specifying the paths for the training and validation datasets, along with the number of classes represented. For training, we utilized Kaggle Notebooks [

33], which provide access to free GPU resources for up to 30 hours per week, significantly accelerating the training process (see

Error! Reference source not found. for hardware specifications). All hyperparameters were kept at default settings, as YOLOv8’s optimized architecture is generally effective without extensive hyperparameter tuning for standard segmentation tasks.

Table 1.

Details of hardware used in the study.

Table 1.

Details of hardware used in the study.

| Hardware |

Description |

| Ram |

29GB |

| CPU |

Intel Xeon 2GHz |

| Memory |

73GB |

| GPU |

Nvidia Tesla T4 |

| GPU Memory |

16 GB |

| Number of GPUs |

2 |

3.4. Training Deep Learning Model

For the training process, we utilized a dataset comprising 2,000 synthetic images for training and an additional 200 synthetic images for validation, totaling 2,200 images. The training dataset was deliberately composed of 25% normal (uncracked) images and 75% defective (cracked) images. This distribution was chosen to ensure the model receives sufficient exposure to both classes, particularly emphasizing defective samples to enhance the model's ability to detect defects using the YOLOv8 architecture. Using this data, we developed and trained a YOLOv8 instance segmentation neural network. Details of the training parameters are provided in Error! Reference source not found.. The training process commenced with selecting the YOLOv8 extra-large (YOLOv8x) segmentation architecture provided by Ultralytics as our base model. All hyperparameters were kept at their default settings unless specified otherwise.

Table 2.

Overview of trained model specifications.

Table 2.

Overview of trained model specifications.

| Parameter |

Description |

| Architecture Used |

YOLOv8-Segmentation |

| Epoch |

300 |

| Image Size |

640 x 640 |

| Save Frequency |

20 Epochs |

| Patience |

50 Epochs |

| Number of Classes |

2 |

| Mosaic Augmentations |

True |

Training was configured for a maximum of 300 epochs, with an early stopping patience parameter set to 50. This parameter tracks training progress and halts the process if no significant improvement is observed over 50 consecutive epochs. By doing so, it conserves GPU resources, shortens training time, and reduces the risk of overfitting by stopping training early, potentially avoiding unnecessary iterations up to the maximum number of epochs. In our experiment, training concluded at the 205th epoch, with the model achieving its optimal performance at epoch 152. Key training parameters, including batch size, weight decay, and optimizer selection, were dynamically adjusted by the YOLOv8 package. This automation in parameter tuning facilitated a streamlined and efficient training process, allowing the model to leverage optimal configurations for effective learning and segmentation performance.

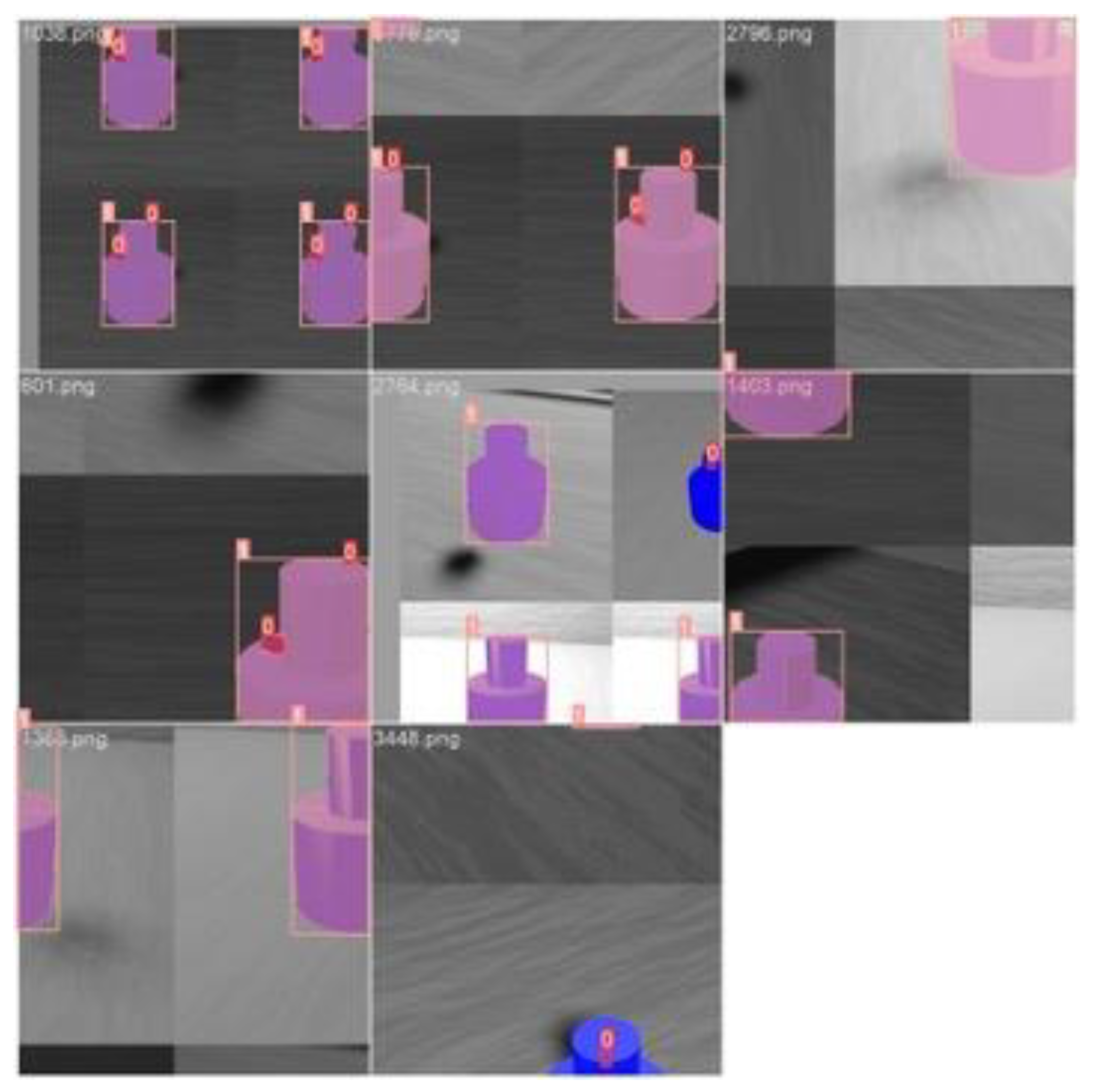

3.4.1. Model Tuning and Augmentation

To enhance model robustness, we employed the mosaic augmentation technique, which is particularly advantageous for detecting small objects within images. This technique combines four images into a single composite mosaic, where each image occupies a quadrant of the final image. By doing so, it effectively quadruples the diversity of visual patterns and object contexts available to the model during training, allowing it to generalize better across varied scenarios. The annotations for these newly generated mosaic images are automatically configured and fed as input to the model.

Mosaic augmentation improves dataset richness by introducing a broader variety of object placements, scales, and background contexts. This diversity strengthens the model's ability to accurately segment objects in complex scenes, enhancing its performance in object detection and segmentation tasks, as supported by recent studies [

30,

31].

Error! Reference source not found. illustrates the implementation of mosaic augmentation in this study, showcasing its effectiveness in enriching the dataset.

Figure 10.

Mosaic augmentations applied in this study.

Figure 10.

Mosaic augmentations applied in this study.

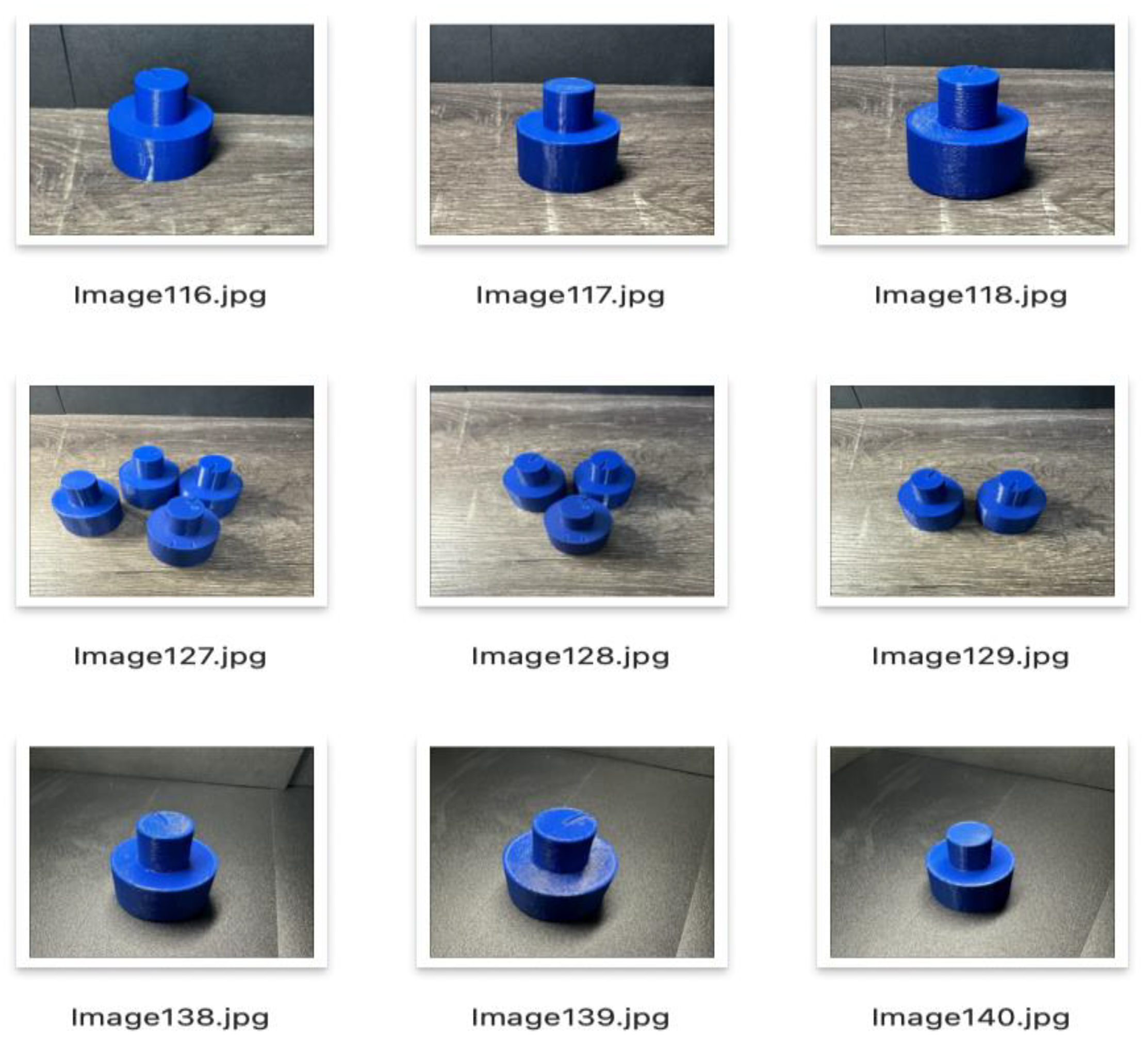

3.6. Buidling Test Dataset

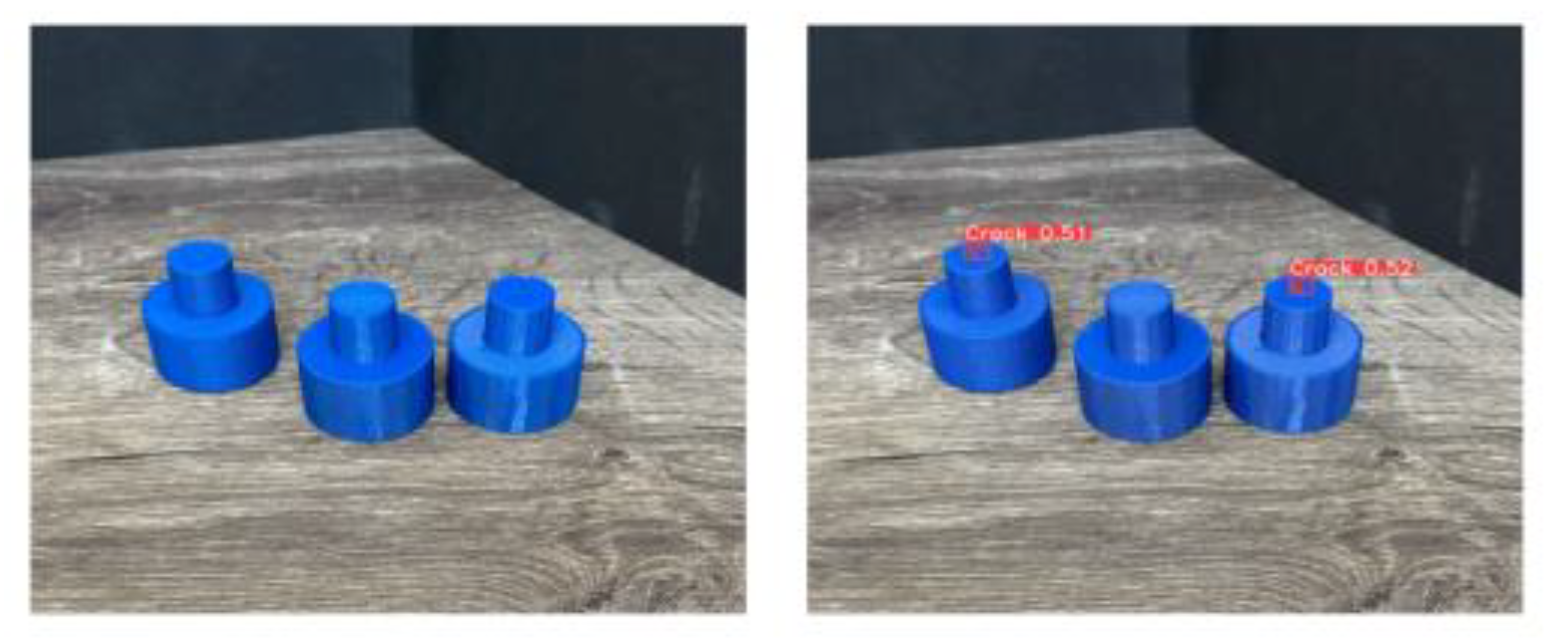

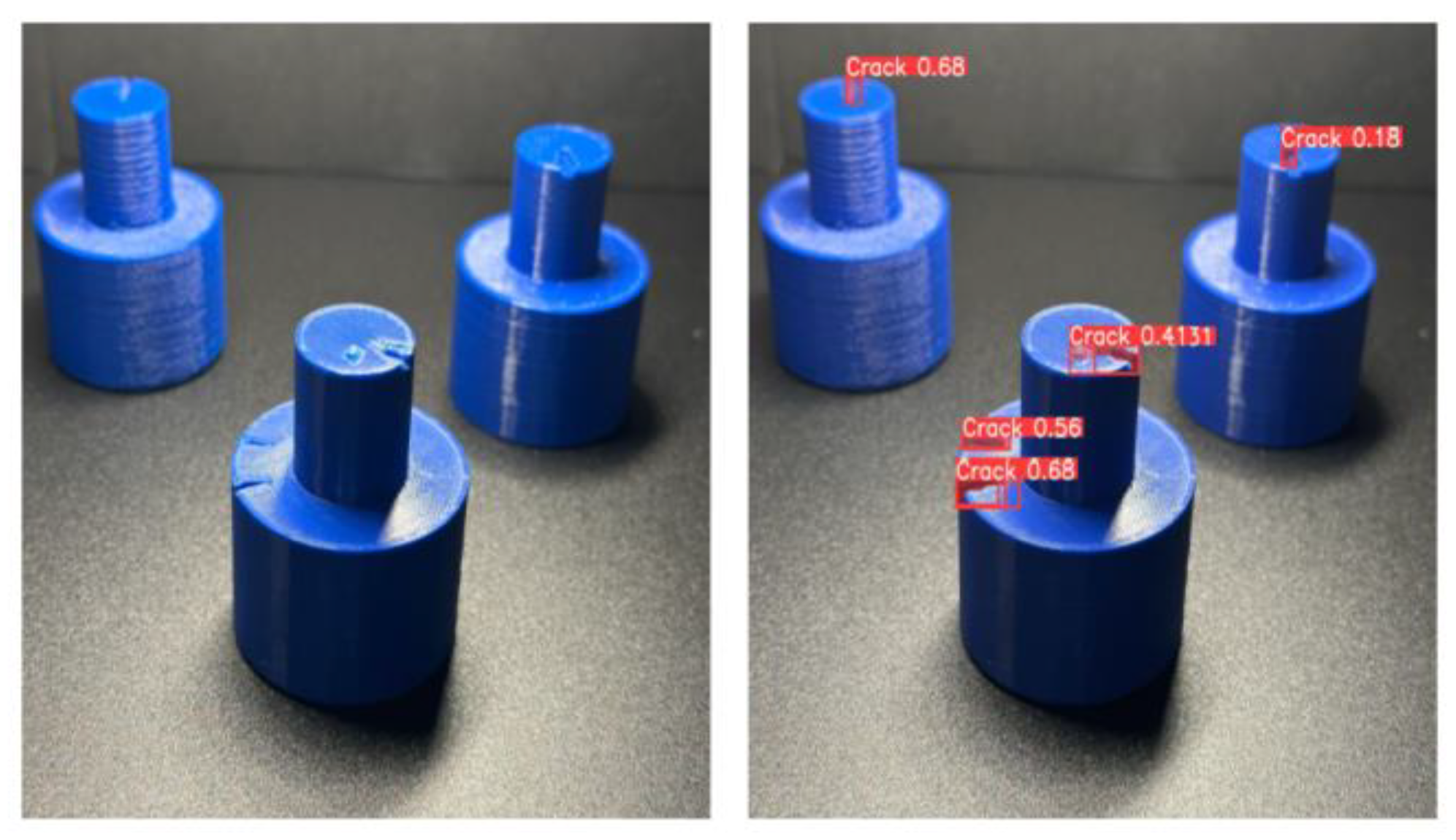

To thoroughly evaluate the model's practical applicability, we focused on assessing its performance using real-world data. This step is essential for evaluating the model’s adaptability and generalization capabilities beyond the synthetic training environment, providing valuable insights into its potential for deployment in manufacturing settings.

For our testing dataset, we began by 3D printing four cylindrical objects with deliberately designed cracks. Using a smartphone camera, we captured square images of these objects under various conditions. Specifically, we varied the lighting, backgrounds, and object orientations to introduce diversity and realism into the dataset.

Additionally, we purposefully included multiple objects in some frames to examine the model’s robustness in scenarios not represented in its training data. The final testing dataset comprised 204 images, enabling comprehensive inference testing. Representative images from the test set are presented in Error! Reference source not found., illustrating the variability in conditions that the model was exposed to during testing.

Figure 11.

Sample images in the test dataset.

Figure 11.

Sample images in the test dataset.

3. Results

In this section, we present the results of our modeling approach. The proposed method demonstrates a high level of accuracy in object classification, with robust precision and recall values achieved during both training and testing phases. Furthermore, we illustrate the model's application, originally trained on synthetic data, in identifying features within real-world instances of 3D-printed objects. The comparative analysis between the model’s performance on the actual test dataset (real objects) and the training dataset (synthetic data) highlights the effectiveness and importance of the proposed approach, underscoring its potential for practical deployment in similar real-world scenarios.

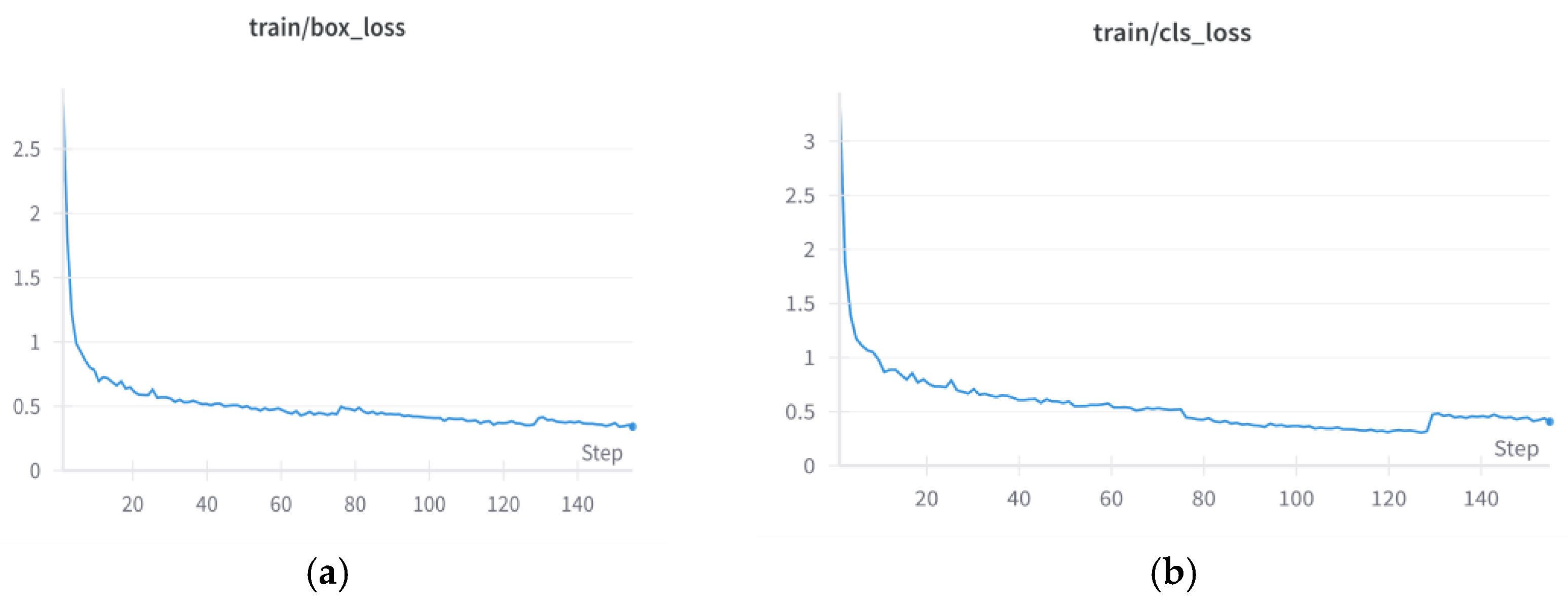

3.1. Results from Training Model on Synthtic Data from Train Dataset

The neural network was trained for defect detection using synthetically generated, augmented, and labeled data. A total of 2,000 images were used in the training process, comprising 500 images of normal, uncracked objects and 1,500 images depicting objects with induced cracks. Throughout training, a consistent decline was observed in both box and classification losses, indicating effective learning and convergence. The loss trends for box and classification losses across epochs are illustrated in Error! Reference source not found. (a) and (b), respectively, visually demonstrating the model’s improvement over successive training iterations.

The model’s precision and recall metrics were calculated on a synthetic validation and real test datasets. These metrics provide insight into the model's performance in classifying "cracked" versus "normal" objects across the datasets. Precision reflects the accuracy of the model’s positive predictions, measuring the proportion of items labeled as cracked or uncracked that were correctly identified. Conversely, recall assesses the model’s capability to detect all relevant instances of cracks within the dataset. These metrics collectively indicate the model’s proficiency in distinguishing defective from non-defective objects, affirming its potential for application in defect detection tasks.

Figure 12.

(a) Box loss diagram during training; (b) Classification loss diagram during training.

Figure 12.

(a) Box loss diagram during training; (b) Classification loss diagram during training.

3.2. Results from Evaluating the Trained Model Performance on Synthetic Validation Dataset

For specific classes, the model demonstrates higher precision, 0.922, and recall, 0.93, for the "Crack" class. This indicates that the model effectively identifies cracks in images and retrieves the majority of cracked cases in the dataset. However, its performance is slightly lower in labeling non-defective items, with a precision of 86.3% and recall of 84.8%. This reflects a slight reduction in accuracy for this class, suggesting that the model occasionally mislabels non-defective objects and fails to identify a few normal cases.

Overall, the model attains a precision of 0.892 and a recall of 0.889 across all categories, demonstrating a balanced and high level of performance in both metrics. These results from the training phase on synthetically generated and augmented images indicate that the proposed pipeline is effective, achieving an overall precision of 89.2% and recall of 88.9% for both defect ("Crack") and non-defect ("Object") categories. The greater proficiency in detecting cracks, with a precision of 92.2% and recall of 93%, underscores the model's reliability in identifying defects and its potential applicability in real-world defect detection tasks.

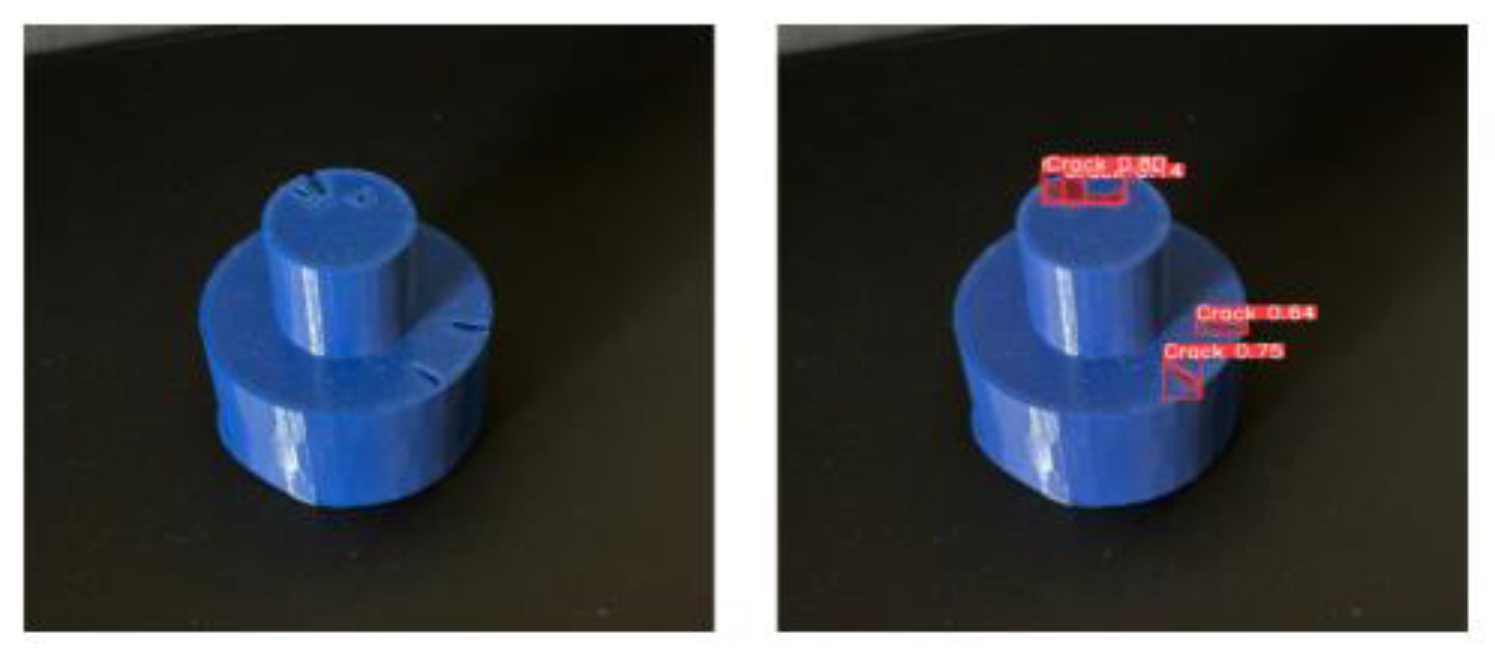

3.3. Results from Evaluating the Trained Model Performance on Real Test Dataset

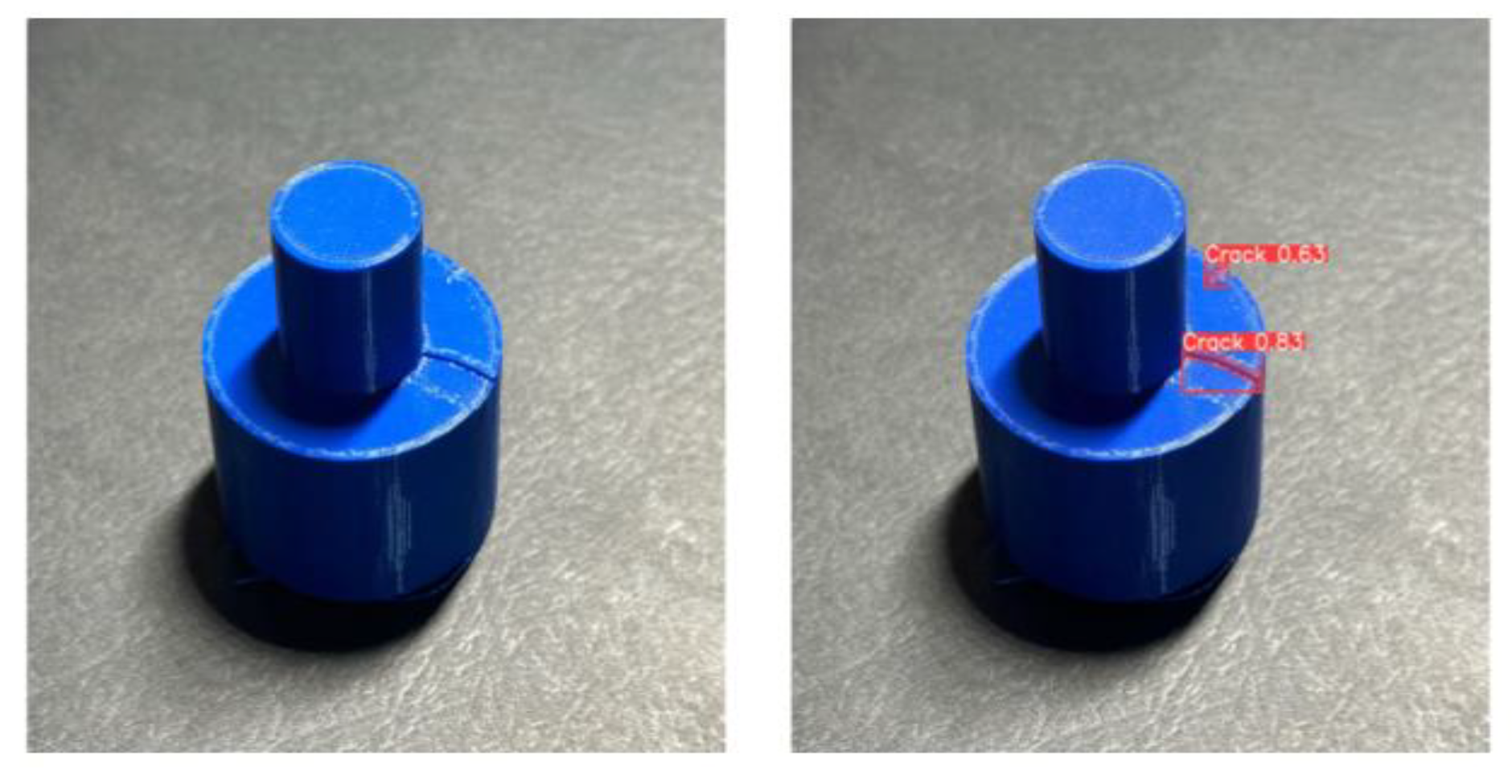

Using the YOLOv8 algorithm, we analyzed crack detection on a test dataset of images featuring real 3D-printed objects with cracks, utilizing the developed model. The annotated images, containing predictive insights, were systematically organized into a designated directory. The processing time for each image varied between 50 and 80 milliseconds on an Nvidia Tesla T4 GPU, with inference time partially influenced by input image size. This model demonstrates the capability for real-time instance segmentation predictions when supported by appropriate hardware and configurations.

We deployed our instance segmentation model on a test set of 204 images, comprising 400 total instances of cracks. The model successfully detected 349 crack instances, highlighting its effectiveness in identifying defects, though it also produced 42 false positives where non-defective regions were mistakenly identified as cracks. The model achieved a precision of 89.2%, indicating high accuracy in positive identifications, and a recall rate of 87.2%, reflecting its ability to capture most relevant instances.

To showcase the model’s high performance across varied scenarios, examples are presented in the following Figures. Error! Reference source not found. illustrates a crack detection scenario where the image was captured using only ambient natural light, with a dark background. In this case, the model successfully identified all cracks despite the lack of controlled lighting. Error! Reference source not found. presents multiple objects positioned on a table under artificial lighting from a table lamp, where the model maintained strong performance. The model demonstrated robustness in handling variations in angle and distance, and successfully detected cracks even in configurations with multiple objects, scenarios not represented in the training images. These examples underscore the model's adaptability in detecting cracks across diverse lighting conditions and object arrangements, reinforcing its applicability in real-world settings.

In Error! Reference source not found., the model demonstrates high precision in detecting a small crack that could easily go unnoticed by the human eye. For larger cracks, while the model successfully identifies the defect, the segmentation mask covers only one edge of the crack. This limitation underscores the model's challenge in cases where training did not explicitly include such specific crack configurations. To address this, an effective improvement strategy would be to re-run our pipeline to generate additional synthetic data that emphasizes scenarios with similar crack types. This synthetic data generation approach provides a rapid and resource-efficient means of enhancing model performance compared to the more labor-intensive process of collecting additional real-world data.

Error! Reference source not found. showcases an impressive result of our model, effectively detecting small cracks among multiple objects, even when some objects in the background are out of focus. The model demonstrates precision in detecting and accurately segmenting these cracks, underscoring its robustness in handling varied object configurations and depth-of-field challenges. This capability highlights the model's potential for accurate instance segmentation in practical applications, such as defect detection in manufacturing, where diverse object arrangements and focus variations are commonly encountered.

4. Discussion

This study introduces a novel approach by training defect detection models on synthetic data and testing them on images of real 3D-printed objects, offering significant applications and advantages for manufacturing operations and process monitoring. Our approach has the potential to transform process monitoring within the manufacturing sector through synthetic data generation, though some limitations were observed. This section outlines the potential applications of this method for enhancing process monitoring in manufacturing, followed by a discussion of the approach’s limitations and potential areas for improvement in

Section 4.1 and

Section 4.2, respectively.

4.1. Applications for Enhancing Manufacturing Process Monitoring

The integration of computational modeling and additive manufacturing offers a robust and innovative framework for improving the efficiency, accuracy, and practicality of quality assurance practices in the manufacturing sector. This comprehensive approach enables enhanced defect detection, improved agility in manufacturing operations, and more effective quality improvement practices. Moreover, it contributes positively to personnel safety and training by incorporating advanced technologies and methodologies tailored to the demands of modern manufacturing processes.

4.1.1. Efficiency in Defect Detection Modeling

The utilization of synthetic data to train initial defect detection models provides a transformative advantage for manufacturers. Synthetic data enables the simulation of a diverse range of defect types and scenarios at a scale unattainable through traditional physical product testing. This capability enhances the depth and scope of defect detection algorithms, enabling the identification of subtle and complex defect patterns that might otherwise be overlooked. Importantly, synthetic data reduces costs and resource requirements by eliminating the need for extensive physical prototype testing during the model training phase.

For model validation, the application of 3D-printed objects as test subjects bridges the gap between theoretical model accuracy and practical implementation. The precision of 3D printing technology allows for the controlled creation of defects, closely mimicking real-world variability in manufacturing processes. This provides a challenging and realistic environment for testing the robustness and reliability of defect detection models. The combination of synthetic data and 3D-printed validation ensures a seamless transition from model development to practical application, facilitating high-performing defect detection systems tailored to real-world manufacturing demands.

4.1.2. Impacts on Quality Improvement

The dual-phase approach of training on synthetic data and validating on 3D-printed objects significantly enhances quality monitoring and control processes. Early detection and rectification of potential defects are critical outcomes, contributing to reduced waste and improved final product quality. This methodology also fosters a culture of continuous improvement, as defect detection models can be continuously updated with data from both synthetic sources and real-world testing. This adaptability enables manufacturers to quickly respond to emerging defect patterns and production anomalies, thereby ensuring a dynamic and responsive manufacturing ecosystem.

Aligned with Industry 4.0 principles, this approach promotes an interconnected and intelligent manufacturing environment. Real-time predictions, achieved through advanced machine learning models running on high-performance hardware such as Nvidia Tesla T4 GPUs, enable rapid processing with inference times between 50 and 80 milliseconds depending on input size. This capability is particularly valuable for dynamic manufacturing scenarios, such as moving objects on conveyor belts, where immediate and accurate defect detection is essential.

The integration of defect detection models with other smart manufacturing systems facilitates real-time data sharing and decision-making, enhancing overall manufacturing intelligence. Insights derived from this process directly inform design improvements, resulting in higher-quality products that better align with consumer needs and expectations. This feedback loop not only drives innovation but also strengthens competitiveness by reducing time-to-market and optimizing resource utilization.

4.1.3. Impacts on Workers Safety and Training

The proposed framework also has significant implications for enhancing worker safety and training in manufacturing environments. By integrating synthetic data-based training with 3D-printed object testing, the approach provides safer and more effective quality control protocols. Training quality management personnel with artificial intelligence models and 3D-printed representations equips them to identify and rectify defects with greater accuracy and preparedness while minimizing exposure to high-value or hazardous materials.

This approach is particularly valuable in industries where defects can have severe financial, safety, or regulatory repercussions. By reducing the need for direct interaction with dangerous or sensitive materials during training and quality control, the framework mitigates risks to both employees and equipment. It ensures that safety standards are maintained without compromising the rigor of defect detection, thereby safeguarding operational integrity and protecting the well-being of workers and end-users alike.

Furthermore, the enhanced training methods provide a scalable and practical way to upskill the workforce, preparing employees for the increasingly technology-driven manufacturing landscape. By combining safety with advanced quality control practices, this framework sets a new standard for operational excellence and workforce development in the manufacturing sector.

4.2. Clallenges and Constraints

This study identifies several challenges and constraints associated with developing and implementing the proposed pipelines for manufacturing process monitoring. One significant challenge lies in the expertise required for 3D modeling software, such as Blender, to create accurate and realistic virtual environments. This step is both time-intensive and highly dependent on the precision and skills of the designers. The authenticity of synthetic scenes in replicating real-world manufacturing conditions demands meticulous attention to detail, which can pose a barrier to scalability and widespread adoption.

The applicability of synthetic data presents another constraint, as its effectiveness is not uniform across all industries. This is particularly critical in sectors with intricate interdependencies within processes or where safety is the highest priority. In such cases, trade-offs must be carefully evaluated to ensure that synthetic data does not compromise safety standards or operational integrity.

Additionally, the subjective nature of data quality poses challenges, as its adequacy varies depending on the specific objectives of each project. To address this, the establishment of standardized guidelines for generating and utilizing synthetic datasets is essential. These guidelines should define the extent, scope, and specific quality thresholds for synthetic data in various applications. Furthermore, a robust validation system is necessary to evaluate synthetic data against predefined criteria. Such a system would enhance data reliability and ensure its consistency across different industrial applications, enabling broader adoption and integration of synthetic data methods into diverse manufacturing processes.

By addressing these challenges, the study highlights the need for interdisciplinary collaboration, standardized methodologies, and continuous refinement of synthetic data approaches to ensure their practicality, reliability, and effectiveness in real-world manufacturing scenarios.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research demonstrate that training defect detection models using synthetic data and validating them with 3D-printed objects provides a comprehensive and effective framework for enhancing manufacturing process monitoring. This innovative approach significantly facilitates deep learning model development improves the accuracy and efficiency of defect detection in manufacturing processes. By adopting this methodology, manufacturers can enhance their quality assurance practices, reduce waste, and optimize resource utilization, ultimately achieving higher operational efficiency and sustainability.

A detailed methodology was established for generating labeled synthetic data, which was successfully employed to train an accurate instance segmentation model capable of delivering consistent performance with both synthetic and real-world data. The innovation of this research lies in overcoming the limitations typically associated with two-dimensional synthetic data by introducing a novel framework that expands the acquisition of labeled data across various domains. By advancing real-time instance segmentation capabilities, this research not only enhances traditional object detection but also promises faster and more cost-effective computer vision-based process monitoring.

Future research directions include incorporating feedback mechanisms into the data generation workflow for immediate model evaluations, as well as leveraging artificially created videos to refine model training further. A key area for future exploration involves generating dynamic synthetic data that accurately mirrors the complex interdependencies within manufacturing processes. This includes developing virtual environments that capture nuanced relationships and hierarchies across various manufacturing stages.

Additionally, improving synthetic data creation techniques remains critical for ensuring the quality, diversity, and relevance of these datasets. By advancing these techniques, future research can refine and adapt synthetic data generation methods to meet the complex demands of real-world industrial applications. These advancements will further contribute to the transformation of manufacturing processes, enabling more intelligent, efficient, and responsive industrial ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M; methodology, A.M, S.B; software, S.B; validation, A.M, S.B; formal analysis, A.M, S.B, F.D.K; investigation, A.M, S.B; resources, A.M, F.D.K; data curation, H.I; writing, original draft preparation, A.M, F.D.K; writing, review and editing, A.M, F.D.K, S.B; visualization, S.B; supervision, A.M; project administration, A.M; funding acquisition, A.M, F.D.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

As this research is ongoing, the dataset supporting the reported results will be made publicly available upon the completion of the project. The data will be shared under the first author's name on GitHub and will be accessible for further use and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- V. Nasir and F. Sassani, “A review on deep learning in machining and tool monitoring: methods, opportunities, and challenges”. [CrossRef]

- E. Zio, “Prognostics and Health Management (PHM): Where are we and where do we (need to) go in theory and practice,” Reliab Eng Syst Saf, vol. 218, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Mancuso, M. Compare, A. Salo, and E. Zio, “Optimal Prognostics and Health Management-driven inspection and maintenance strategies for industrial systems,” Reliab Eng Syst Saf, vol. 210, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. V. Badarinath, M. Chierichetti, and F. D. Kakhki, “A machine learning approach as a surrogate for a finite element analysis: Status of research and application to one dimensional systems,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 1–18, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liao, I. Ragai, Z. Huang, and S. Kerner, “Manufacturing process monitoring using time-frequency representation and transfer learning of deep neural networks,” J Manuf Process, vol. 68, pp. 231–248, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Moghadam and F. Davoudi Kakhki, “Empirical Study of Machine Learning for Intelligent Bearing Fault Diagnosis,” in Production Management and Process Control, AHFE International, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Kakhki and A. Moghadam, “Convolutional Neural Networks for Fault Diagnosis and Condition Monitoring of Induction Motors,” in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023, pp. 233–241. [CrossRef]

- M. Bertolini, D. Mezzogori, M. Neroni, and F. Zammori, “Machine Learning for industrial applications: A comprehensive literature review,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 175. Elsevier Ltd, Aug. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Chan, M. Rabaev, and H. Pratama, “Generation of synthetic manufacturing datasets for machine learning using discrete-event simulation,” Prod Manuf Res, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 337–353, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Wuest, D. Weimer, C. Irgens, and K. D. Thoben, “Machine learning in manufacturing: Advantages, challenges, and applications,” Prod Manuf Res, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 23–45, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Pahren, P. Thomas, X. Jia, and J. Lee, “A Novel Method in Intelligent Synthetic Data Creation for Machine Learning-based Manufacturing Quality Control,” in IFAC-PapersOnLine, Elsevier B.V., Jul. 2022, pp. 73–78. [CrossRef]

- T. Kelmar, M. Chierichetti, and F. Davoudi, “Optimization of Sensor Placement for Modal Testing Using Machine Learning,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Kannan and P. Nandwana, “Accelerated alloy discovery using synthetic data generation and data mining,” Scr Mater, vol. 228, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Vanherle, S. Moonen, F. Van Reeth, and N. Michiels, “Analysis of Training Object Detection Models with Synthetic Data,” Nov. 2022, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.16066.

- Z. Gastelum, T. Shead, and M. Higgins, “Synthetic Training Images for Real-World Object Detection.” [Online]. Available: https://www.lInl.govinews/researchers-developing-deep-learning-system-advance-nuclear-nonproliferation-.

- D. Schoepflin, D. Holst, M. Gomse, and T. Schüppstuhl, “Synthetic Training Data Generation for Visual Object Identification on Load Carriers,” in Procedia CIRP, Elsevier B.V., 2021, pp. 1257–1262. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, L. Chen, M. Shao, H. Liang, and J. Ren, “ESAMask: Real-Time Instance Segmentation Fused with Efficient Sparse Attention,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 14, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Li and Y. Yan, “Street tree segmentation from mobile laser scanning data using deep learning-based image instance segmentation,” Urban For Urban Green, vol. 92, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Venkataramanan et al., “Usefulness of synthetic datasets for diatom automatic detection using a deep-learning approach,” Eng Appl Artif Intell, vol. 117, p. 105594, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Amjoud and M. Amrouch, “Object Detection Using Deep Learning, CNNs and Vision Transformers: A Review,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 35479–35516, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Khare, S. Gandhi, A. M. Rahalkar, and S. Mane, “YOLOv8-Based Visual Detection of Road Hazards: Potholes, Sewer Covers, and Manholes,” Oct. 2023, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2311.00073.

- C.-T. Chien, R.-Y. Ju, K.-Y. Chou, and J.-S. Chiang, “YOLOv8-AM: YOLOv8 with Attention Mechanisms for Pediat-ric Wrist Fracture Detection,” vol. 14, 2024.

- J.-Y. Nie, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, and IEEE Computer Society, 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data : proceedings : Dec 11- 14, 2017, Boston, MA, USA.

- Manettas, N. Nikolakis, and K. Alexopoulos, “Synthetic datasets for Deep Learning in computer-vision assisted tasks in manufacturing,” in Procedia CIRP, Elsevier B.V., 2021, pp. 237–242. [CrossRef]

- K. C. Chan, M. Rabaev, and H. Pratama, “Generation of synthetic manufacturing datasets for machine learning using discrete-event simulation,” Prod Manuf Res, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 337–353, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Eversberg and J. Lambrecht, “Generating images with physics-based rendering for an industrial object detection task: Realism versus domain randomization,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Schraml and G. Notni, “Synthetic Training Data in AI-Driven Quality Inspection: The Significance of Camera, Lighting, and Noise Parameters,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 2, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Wong, K. Kunii, M. Baylis, W. H. Ong, P. Kroupa, and S. Koller, “Synthetic dataset generation for object-to-model deep learning in industrial applications,” Sep. 2019, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1909.10976.

- T.-Y. Lin et al., “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context,” May 2014, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1405.0312.

- M. Lui et al., “MC-YOLOv5: A Multi-Class Small Object Detection Algorithm,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Chai, H. Zeng, A. Li, and E. W. T. Ngai, “Deep learning in computer vision: A critical review of emerging techniques and application scenarios,” Machine Learning with Applications, vol. 6, p. 100134, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Immersive Limit website: https://www.immersivelimit.com/tutorials/create-coco-annotations-from-scratch.

- Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/. Accessed: 2023-12-02.

- R. King, “Brief summary of yolov8 model structure,” GitHub, 2023, https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics/issues/189.

- Community, B. O. (2018). Blender - a 3D modelling and rendering package. Stichting Blender Foundation, Amsterdam. Retrieved from http://www.blender.org.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).