1. Introduction

The proliferation of IoT devices will continue and accelerate substantially—they are expected to account for more than two-thirds of the 41.6 billion internet-connected devices projected by 2025 [9]. IoT devices, such as single-board computers like the Raspberry Pi, can function as hacking machines due to their compact size, affordability, and widespread usage. Using a Raspberry Pi with Kali Linux as a hacking machine can be a practical and portable solution. A Raspberry Pi is widely used as in IoT environment typically as the central component to collect, control and analyse data from sensors. It’s often deemed as the best choice for IoT projects because of its processing power, affordability, and ease of use.

Nonetheless, the growing use of such IoT Devices have provided an entirely new dimension to Cyber Criminals as digital forensics, necessitating the advancement of specialised IoT forensics techniques.[2]. IoT devices, ranging from smart home gadgets to industrial systems, generate vast amounts of data that can be crucial in criminal investigations and cybersecurity [3].

IoT forensics involves the identification, collection, preservation, and analysis of digital evidence from these devices. Its importance lies in its ability to provide key insights into device interactions, network behaviours, and user activities, making it essential for resolving cases involving data breaches, cyberattacks, and even physical crimes [10]. As IoT ecosystems continue to expand, the need for robust IoT forensic methodologies becomes critical to ensuring comprehensive and accurate investigations in the face of evolving cyber threats [3].

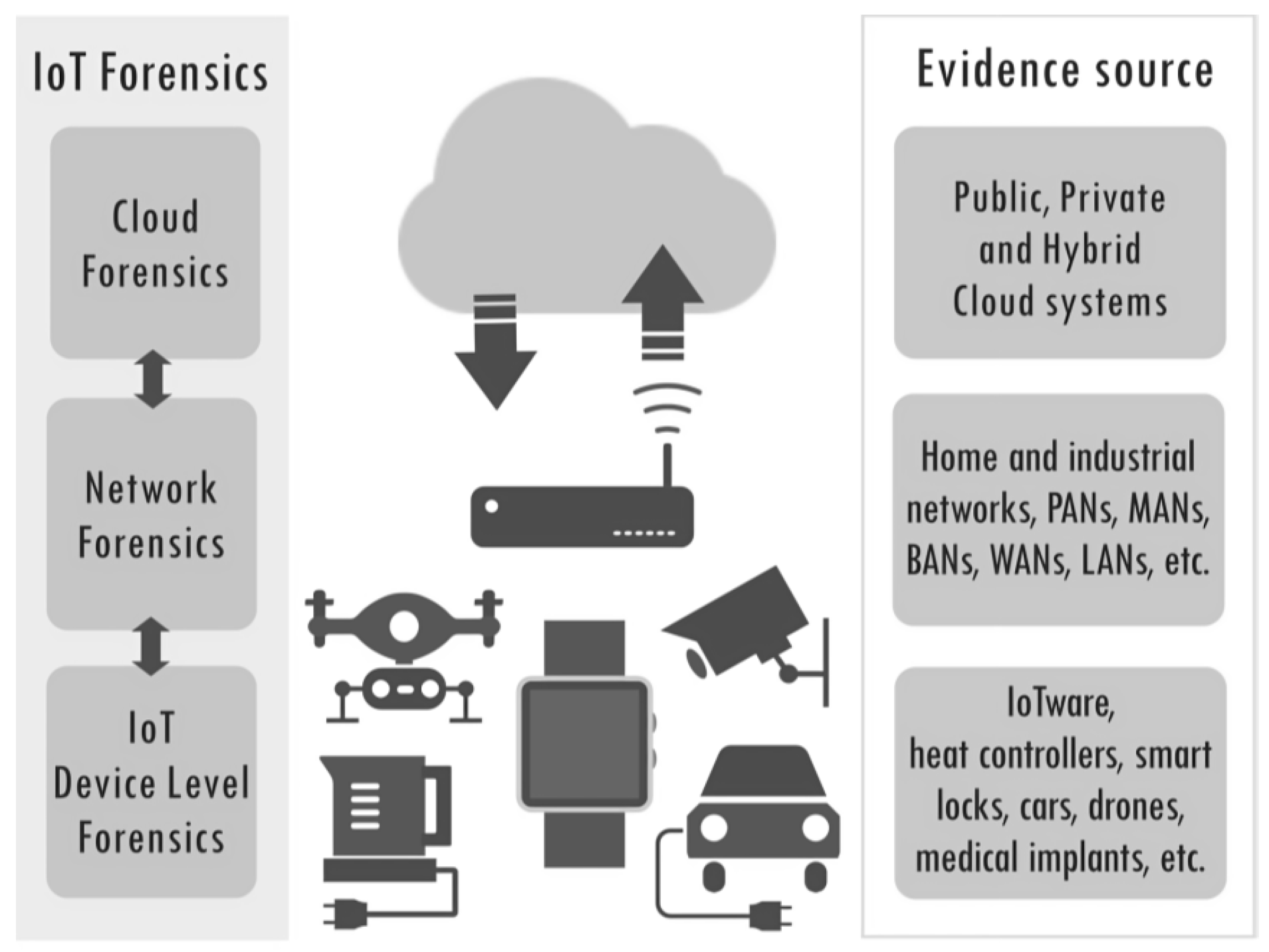

IoT forensics encompasses these forensics: device, live, network and cloud. ‘Things’ might be devices with permanent storage with familiar file systems and file formats. Such ‘things’ can be treated as any other digital device. Unfortunately, ‘things’ might use proprietary file systems and formats. They might not even have permanent memory that holds user data and a limited power supply that severely limits duration or even prevents live forensics [23]. ‘Things’ might have a limited amount of RAM and transfer all their data immediately. That data can be transferred in an open standard or a proprietary closed format. Network data can be encrypted. IoT data is often processed in the cloud located in an unknown location that can be on the other side of the planet. All this makes IoT forensics different and more challenging than traditional digital forensics [10].

Furthermore, the paper explores the challenges specific to IoT forensic investigations, such as the volatile nature of IoT data, the complexity of IoT architectures, and the integration of IoT devices into larger network infrastructures. Legal and ethical considerations surrounding IoT forensics, including privacy concerns and chain of custody issues, are also addressed. In this work, things of forensic interest are to find and extract forensic artefacts from:

Criminal-operated Linux (Command and Control).

Abused/misused Linux systems (suspect user).

Imaged systems (dead disk).

Independent artefacts on Linux distribution

Raspberry Pi-5 running default Kali Linux.

Metapackage from other platforms.

Figure 1 depicts IoT forensics subcomponents and their related artefacts sources.

In the IoT and IIoT context, the defence-in-depth approach is complex and results in the addition of multiple layers of security that are often vulnerable to a high-level attacker because they contain vulnerabilities due to human error, misconfigurations, and system weaknesses [5]. Being flexible comes at a huge cost, as cybersecurity professionals, experts, and researchers have found that cyber threats are becoming more frequent, complex, and sophisticated as the general rule of the attack surface evolves. Protecting complex networks and critical assets from cyber threats has forced network security professionals to implement more and more security layers and policies [7].

1.1. Research Motivation

IoT forensics presents complex challenges across several dimensions, starting with evidence source identification, as evidence is often distributed across a variety of interconnected devices with different protocols and data storage formats. Evidence acquisition or forensics imaging is also a challenge, given IoT devices’ limited storage, proprietary data formats, and reliance on cloud-based storage, which complicates access [18]. Additionally, traditional forensic tools and techniques are insufficient for IoT-specific needs, as they are not designed to handle the unique architectures and data formats of IoT devices, this necessitates utilising specialised tools. These factors highlight the importance of customized forensic strategies and international legal collaboration to effectively address the complexities of IoT investigations.

1.2. Research Questions

Our Research Questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1: How do forensic processes differ between conventional computers and IoT Devices such as Raspberry Pi devices?

RQ2: What are the key differences in terms of meaningful forensics artefacts between conventional computers and IoT Devices?

RQ3: What are the current challenges and limitations in IoT Forensics and possible best practices to implement to overcome these challenges?

2. Literature Review

As IoT devices proliferate across various domains, understanding the unique characteristics of IoT forensics becomes imperative for effective investigation and incident response. This section highlights the scope of IoT Forensics. IoT forensics encompasses a broad range of activities and challenges related to investigating and analysing digital evidence from Internet of Things (IoT) devices and systems. The scope of IoT forensics extends beyond traditional digital forensics practices to address the unique challenges posed by interconnected, heterogeneous, and pervasive IoT environments [12]. The uniqueness of IoT forensics can be summarized in the following points:

- (1)

Device Diversity: IoT devices come in various forms, including single-board computers (SBC), sensors, actuators, wearables, smart home appliances, and industrial controllers making the task address the diversity in device types, architectures, communication protocols, and operating systems challenging.

- (2)

Data Acquisition: Retrieving data from IoT devices while preserving its integrity and ensuring admissibility in legal proceedings is complex with many challenges such as accessing data stored in volatile memory, retrieving logs and configuration settings, and capturing network traffic.

- (3)

Distributed Nature: IoT environments involve numerous geographically distributed devices, making data collection and analysis challenging, especially with real-time data generation.

- (4)

Scalability Issues: The vast number of devices and data in IoT systems demands new forensic approaches to efficiently process and analyse large-scale information.

- (5)

Heterogeneous Protocols: IoT devices use various communication protocols, requiring forensic experts to understand and analyse diverse and often complex interactions.

- (6)

Privacy and Legal Concerns: IoT devices collect sensitive data, raising privacy issues. Forensic investigations must navigate legal frameworks to ensure evidence is admissible without violating privacy rights.

The Internet of Things (IoT) is gaining popularity, and numerous sectors have drawn attention to the topic of IoT security and forensics. Research efforts on IoT security and forensics are extensive and cover a wide range of topics, from the theoretical underpinnings of cybersecurity to the practical challenges of securing and investigating IoT devices [18]. The use of low-cost, portable tools like the Raspberry Pi has emerged as a recurring theme, offering both opportunities and challenges in the field of IoT forensics. Future research should continue to explore these areas, particularly focusing on the development of more robust forensic tools and methodologies tailored to the unique challenges posed by IoT environments. This literature review synthesizes key studies focusing on different aspects of IoT security, digital forensics, and the use of low-cost, portable tools like the Raspberry Pi for these purposes. It also offers a thorough examination of existing research on the use of Raspberry Pi in hacking and forensic analysis. It explores the performance, capabilities, and vulnerabilities of these devices within IoT environments, highlighting the crucial role of IoT forensics in criminal investigations and the importance of strong security measures [21].

Analysing data obtained from IoT devices involves examining logs, event traces, metadata, communication patterns, and potentially large volumes of sensor data. Therefore, investigators need tools and techniques to process, interpret, and correlate diverse data sources for reconstructing events and identifying evidence. Network Forensics refers to IoT devices’ communication over wireless and wired networks, this presents challenges for capturing, analysing, and reconstructing network traffic [17]. Therefore, investigators must consider encryption, encapsulation, and fragmentation mechanisms used in IoT communication protocols. Many IoT deployments leverage cloud and edge computing platforms for data processing, storage, and analytics. Forensic investigations may involve accessing data stored in remote servers, analysing data streams at the edge, and tracing data flows across distributed architectures.

In their 2018 study, Wanic and Rowe explore the topic of cybersecurity and deterrence within IoT environments, focusing on strategies to prevent cyberattacks, particularly those orchestrated by nation-states. They highlight the key differences between cyber weapons and conventional military tools, delving into the motivations that drive cyber operations. Additionally, the authors assess the effectiveness of various deterrence strategies. While their research does not specifically address IoT forensics, it lays the foundation for understanding the broader cybersecurity landscape, which is vital for contextualizing the unique challenges faced in IoT environments. [9]

Stoyanova et al. (2020) provide a comprehensive survey of the challenges and methodologies in IoT forensics, emphasizing critical areas such as the establishment of data inclusion and exclusion criteria, the automation of forensic processes, and the integration of forensic capabilities into device design referred to as "forensics by design." Their research also addresses the usability of forensic tools, the complexities involved in shutting down IoT devices for analysis, the implications of service level agreements (SLAs) on data access, and the privacy risks associated with encryption and anti-forensics techniques. This study is essential for understanding the intricate landscape of IoT forensics and the various obstacles that practitioners encounter in their investigations. [10]

In their 2018 study, [14] explored the field of ethical hacking and penetration testing, highlighting the advantages of using low-cost, portable hardware such as the Raspberry Pi. The authors provide a thorough overview of ethical hacking, covering essential definitions, techniques, and the practical application of various tools, particularly using a Raspberry Pi for tasks like reconnaissance and remote penetration testing. By integrating both theoretical insights and hands-on practices, this study serves as a valuable resource for understanding how portable devices can enhance cybersecurity efforts and forensic investigations. In their 2022 study, [15] investigated the vulnerabilities using a Raspberry Pi 4 running Raspberry Pi OS to simulate attacks using Kali Linux and various automated tools. Their research reveals significant security concerns inherent to IoT devices, emphasising the critical need for robust security measures to prevent potential exploitation. The methodology outlined in their work provides a comprehensive discussion of the practical challenges faced in securing IoT environments, highlighting the complexities involved in protecting these devices from cyber threats.

[16] investigated the creation of a low-cost, portable digital forensic imaging tool using a Raspberry Pi. The primary objective of their research was to develop an affordable imaging solution capable of effectively collecting and analysing digital evidence. This work is especially significant to IoT forensics, where the need for cost-effective tools is critical due to the extensive variety and prevalence of IoT devices in various environments. in [11] and [19], researchers conducted an evaluation and comparison of two open-source intrusion detection systems (IDSs) operating on a Raspberry Pi 2 (Model B). The primary objective of their research is to assess the suitability of these systems for deployment in cost-sensitive network environments [13]. This investigation holds significant importance for IoT forensics, emphasising the need for effective intrusion detection mechanisms in resource-constrained scenarios where affordable hardware plays a crucial role.

The research conducted by [20] examined the security vulnerabilities found in two commercial drones, utilising the Raspberry Pi as an automated tool for their analysis. This study not only highlights the significant security weaknesses inherent in these drones but also demonstrates the potential for exploiting such vulnerabilities. By shedding light on these risks, the research contributes valuable insights to the broader field of IoT forensics by emphasizing the dangers associated with the increasing integration of IoT devices across various sectors. A summary of related work, aspects covered, and techniques used are captured in

Table 1.

The literature identifies a notable gap in comparative studies of forensic processes between Raspberry Pi and traditional PCs. While many studies focus on specific aspects of IoT forensics, there is a lack of research that directly compares the forensic capabilities and challenges of these two platforms. The literature also highlights ongoing debates regarding the effectiveness of various forensic tools and methodologies when applied to IoT devices [24].

3. Methodology

The rise of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has introduced significant challenges to traditional forensic investigations, which are often tailored to conventional computing environments. This study addresses these challenges by creating a testbed that simulates environments where conventional PCs and IoT devices, like the Raspberry Pi, coexist. By simulating various cyber-attacks and analysing data such as network traffic, memory dumps, and system logs, the research compares forensic processes between these platforms. The findings highlight the strengths and limitations of existing forensic tools in IoT environments, emphasizing the need for specialized approaches for IoT forensics.

3.1. Testbed Design

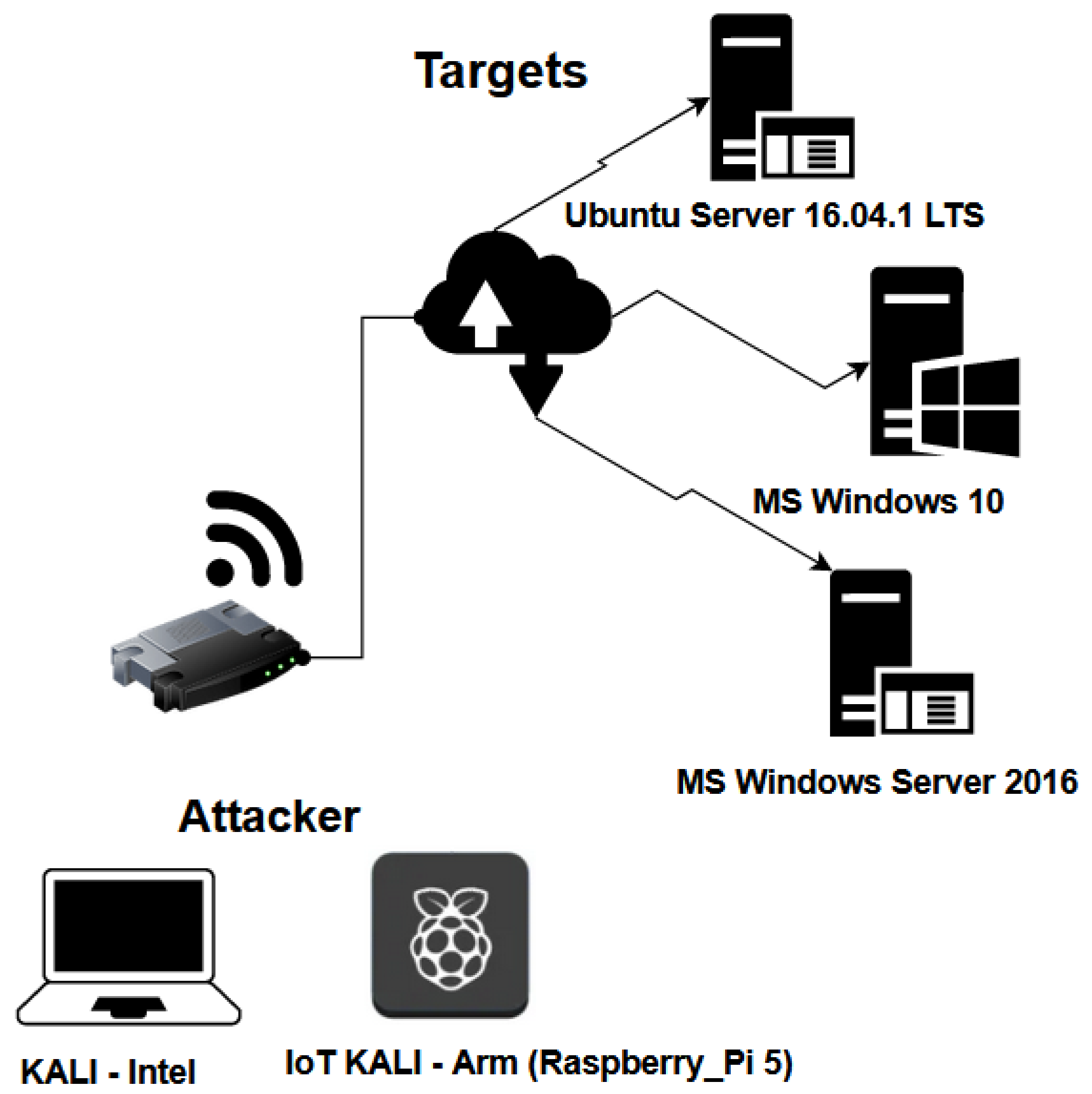

The forensic investigation in this study required a meticulously designed testbed to evaluate and compare forensic processes between conventional computers and IoT devices. The testbed included both a traditional PC and a Raspberry Pi, configured to simulate a real-world environment where these devices coexist. The PC used was an Acer Aspire V5, equipped with 8GB RAM and a 120GB SSD, running Kali Linux 2023.3. The Raspberry Pi 5, representing the IoT device, featured 5GB RAM and a 32GB SD card, also running Kali Linux 2023.3. Both devices were connected to a common Wi-Fi network using a Nokia HA-140W-B router. To generate relevant forensic data, four distinct cyber-attack scenarios were simulated on both the PC and the Raspberry Pi. These attacks included Windows 7 – EternalBlue, PowerShell-Empire, Windows 10 – Multi/Handler with Msfvenom payload, and Koadic Framework. Network traffic during these attacks was captured using Wireshark, ensuring comprehensive data for forensic analysis.

Figure 2 depicts the key components and processes of Tested design and implementation.

3.2. Dataset Elaboration

Various types of data were collected from both devices during the simulations to ensure a thorough forensic investigation. Network traffic data, including all incoming and outgoing packets, was captured and saved in pcap format for later analysis. Memory dumps were obtained using LiME (Linux Memory Extractor) for the Raspberry Pi and Microsoft AVML for the PC. These memory dumps were crucial for analysing the processes and system states during the attacks.

Additionally, system logs, such as event, application, and security logs, were collected from both devices to provide context to the network traffic and memory data. File system snapshots were also taken before and after the attack simulations, allowing for the identification of any changes made by the attackers.

3.3. Data Capturing

The forensic data capturing process involved both forensic imaging and live RAM dumps. FTK Imager was used to create forensic images of the PC’s hard drive and the Raspberry Pi’s SD card, providing a complete snapshot of the data at the time of acquisition. For live data capture, RAM dumps were obtained using LiME for the Raspberry Pi and Microsoft AVML for the PC. These RAM dumps were essential for analysing active processes and volatile data, which would otherwise be lost once the device was powered off. The collected data, which included system logs, memory dumps, and network traffic data, was then thoroughly analysed to identify traces of the simulated attacks.

3.4. Comparative Forensics Analysis

we conducted a thorough investigation to compare the forensic susceptibility of a standard Personal Computer (PC) and a Raspberry Pi (RPI). The comparative analysis aim to assess the forensics capabilities enabled by each device and how could the data be extracted and analysed in case of forensic investigation. The focus was on several key areas namely:

Tool compatibility: The comparative forensic analysis highlighted several significant differences and challenges between conventional computers and IoT devices. Traditional PCs demonstrated high compatibility with most forensic tools, which facilitated a more robust forensic investigation. In contrast, the Raspberry Pi analysis faced significant limitations due to its ARM architecture, which is not widely supported by many forensic tools.

Data Retention: Data retention also varied, with PCs retaining extensive logs and system data, allowing for a detailed forensic investigation. The Raspberry Pi, however, had limited storage and logging capabilities, resulting in fewer retrievable forensic artefacts and challenges in performing a thorough analysis.

Memory Analysis: Memory analysis was another area where differences were evident. While memory analysis on PCs was effective, with tools like Volatility providing detailed data from memory dumps, the Raspberry Pi’s architecture and limited tool support made this process much more challenging, if not impossible.

network traffic analysis: Network traffic analysis was consistent across both devices, with Wireshark effectively capturing relevant data. However, the contextual information provided by logs and memory analysis was more detailed for the PC, offering a more comprehensive view of the attacks.

system log analysis: System log analysis further underscored the differences, with PCs offering comprehensive and detailed logs, enabling deeper forensic examinations. In contrast, the Raspberry Pi provided limited logs, restricting the scope of analysis

file system snapshots: Finally. while PCs allowed for detailed file system snapshots before and after the attacks, revealing significant changes, the Raspberry Pi’s limited storage capacity resulted in fewer detectable changes, further constraining forensic analysis.

The discussion below evaluates these differences in different categories of forensic artefacts, highlighting their implications in forensic investigations.

Table 2 summarises the comparative forensics analysis

3.4.1. DisPartitions of the File System

The structure of the file system on a device will, to a large degree, define how forensic analysis is done by determining where and how data is stored, accessed, and managed. The PC machine running Kali Linux offers wider support for multiple partition types, such as FAT32, Ext4, Linux Swap, and unpartitioned space, which enhance flexibility in data storage and system configuration. Furthermore, dev/pts and dev/shm partitions create temporary storage for the session and temporary data that is quite handy in the capture of ephemeral artefacts. By contrast, the Raspberry Pi 5 only supports FAT32 and ext4 partitions. This greatly constrains its functionality in regard to swap memory and unpartitioned space due to a lack of Linux Swap, dev/pts, and dev/shm partitions, which makes the Raspberry Pi very limited with respect to how it manages memory. It therefore offers less capability to capture artefacts related to temporary storage or session information. Thus, the forensic investigators who would research or analyze a Raspberry Pi 5 would have fewer artefacts to consider compared to what is available on a PC and hence are very likely to miss some key transient data that may reside in swapped or shared memory areas.

3.4.2. MRBF/EFI/Config/Initramfs Files

Understanding boot and configuration files may be needed in the course of the startup process and system configuration, as both might reveal the tampering or malicious configurations. Grub.cfg, grub.d, conf.d, hooks, modules, update-initramfs.conf among others, on the PC provided a very important record of the events of the boot and configuration process that would assist the investigator in reconstructing the system’s boot sequence.

However, the main configuration file that is responsible for defining the behaviour of the bootloader in a grub.cfg is not present on Raspberry Pi 5, limiting forensic insight into the process of the boot. The rest of the configuration files, hooks, modules, and update initramfs.conf exist. However, without grub.cfg, it is impossible for forensic analysts to reconstruct or analyze the activity of the bootloader. This difference is critical in cases where evidence of bootloader modification which is a common tactic among attackers required as essential to a forensic investigation.

3.4.3. File System: Boot/EFI Logs

Other significant differences are the boot and EFI logs that one can find. On a PC, logs such as efi, boot.log, and dpkg.log summarize the process of booting up and package handling, hence giving the investigator an overview of the system changes and possible tampering.

However, the Raspberry Pi 5 does not provide efi and installer logs, and the investigator can use only boot.log and dpkg.log. This diminishes the level of detail concerning the boot process, and some critical logs may be missed that could indicate unauthorized changes or suspicious activities. Moreover, since most of the systems have no efi logs, the forensic analyst loses the ability to track some issues related to firmware or hardware-level tampering, which may be needed in the case of some new sophisticated cyber-attacks.

3.4.4. Systemd Boot/Shutdown

Both systems use /usr/lib/systemd and /etc/systemd for storing Systemd records of boots and shutdowns, respectively. Therefore, no significant difference exists between these systems in regard to this area. This homogeneity ensures that comparable records of boot and shutdown processes are equally available to the investigator on either device, thus reinforcing system start-up and shutdown behaviour auditing on either device or platform. This is one of the limited spaces where the forensic artefact landscape is still equivalent across both systems.

3.4.5. Installed Software and System Logbook

The installed software and system journal provide insight into the applications running on a system and their respective activities. Both systems do have system.journal and user-1000.journal files, important in capturing logs of user activities and events within the system. On the other hand, it should be noticed that both the PC and the Raspberry Pi 5 do not contain any var/log/messages or var/log/syslog, which might be a limitation to forensic visibility with respect to low-level system messages and error logs.

This similarity emphasizes one of the weaknesses of the default logging configuration in Kali Linux for both platforms, whereby important system messages are not captured by the traditional logs. In an investigation, this may mean losing critical error reports, system warnings, or security notices that usually flood these logs.

3.4.6. Network Log Files

Network logs are some of the most critical logs as far as tracking device connectivity for the purpose of forensic investigation and the determination of possible points of compromise. Below are the entries recorded in the Network Manager log file of the PC, reflecting some records of target devices along with network interface activity, for example, Wlan0. In the case of the Raspberry Pi 5, it also contains Wlan0. however, an extra secret_key entry is present that was missing in the PC. This unique log artefact on the Raspberry Pi 5 can hint at particular security settings or authentications, adding an extra network dimension of artefacts that could be relevant within some sorts of investigations.

The presence of the secret_key entry on the Raspberry Pi 5 may raise some questions regarding network configuration security, while absence on the PC shows difference in processing by each device of authentication logs. This, for an investigator, points to the need for knowledge of the specific platform when examining network activity across dissimilar devices.

3.4.7. Cache, Swap, and Persisted Data

The Cache and swap spaces play a big role in forensic analysis, as generally, residual data is left behind. Although both devices record Wlan0 and some network-related records, the Raspberry Pi 5 adds the secret_key entry. This Raspberry Pi reduces the vulnerable storage that could retain useful data, such as unsaved documents or network credentials since the swapping space is not available in it.

This little swap memory will contain the investigations that can be carried out on the Raspberry Pi, especially if the evidence has to be examined with respect to user activity or unsaved session data. Whereas in PC, swap memory may capture transient data and is an extended set of forensic artefacts.

3.4.8. Other Applications Logging

Both platforms use the same application logs for most default cybersecurity applications, empire_client.log, server.log, and MS17(eternalblue). For forensic investigators, this consistency of application logs presents advantages in allowing consistent analysis of the same application-level artefacts across devices.

3.4.9. Volatile Memory (RAM)

Live memory analysis is crucial for capturing volatile data; however, it’s only supported on the PC, which allows complete RAM analysis with tools like Volatility. Due to the architecture of Raspberry Pi 5, it doesn’t support Volatility, thusly live memory analysis isn’t possible. This has really proved a deep handicap because most live memory images usually contain, in real-time, operating processes, encryption keys, and session information which is very valuable during forensic investigation. Without this capability on the Raspberry Pi, forensic investigators may miss volatile artefacts critical to understanding real-time system behaviour.

4. Research Findings and Discussion

4.1. Key Differences Between PC and Raspberry Pi

Our investigation revealed significant differences between the PC and the Raspberry Pi in terms of forensic capabilities. The PC demonstrated a tendency to retain extensive logs, system data, and processes, facilitating a detailed forensic analysis. This is in stark contrast to the Raspberry Pi, which, due to its limited logging capability and smaller storage capacity, offered fewer forensic artefacts, thus limiting the depth of analysis. One of the most critical areas of difference was memory analysis. While acquiring and analysing AM images from a Windows-based PC was straightforward and provided rich data, the process was significantly more complex with Linux-based systems and IoT devices like the Raspberry Pi. The lack of tool compatibility with the RPI’s ARM architecture posed a significant challenge, making it difficult to perform comprehensive forensic analysis.

Table 3 summarizes the differences in forensic capabilities between the PC and Raspberry Pi:

Additionally, a detailed analysis of the file system and other artefacts on both devices further highlighted these differences. Starting with the file system, the PC features multiple partitions, including FAT32, ext4, and Linux Swap, along with unpartitioned space and various directories such as /dev/pts and /dev/shm. In contrast, the RPI5’s file system is more limited, comprising only two partitions (FAT32 and ext4) and lacking additional directories and unpartitioned space. This distinction suggests that the PC has a more complex and detailed file system structure, which may offer more artefacts for forensic analysis.

When examining boot processes, the PC demonstrates detailed boot configuration files, including grub.cfg, various grub.d scripts, and configurations for initramfs. The RPI5, however, shows limited support in this area, with many boot-related files not available. This limitation in the RPI5 indicates potential challenges in performing comprehensive forensic investigations related to the boot process.

In terms of system services and scheduling, both devices utilize systemd for boot and service management, suggesting a common approach in handling these functions despite potential differences in implementation details. However, the PC’s extensive logging capabilities, including directories like /var/log/messages and /var/log/syslog, contrast with the RPI5’s reliance on a journal system (system.journal, user-1000journal). This disparity highlights the PC’s superior capacity for retaining detailed logs, which are crucial for forensic analysis.

Log files and system journals further emphasize the differences, with the PC offering comprehensive logs, including those related to network management. The RPI5’s logs are more focused on network interfaces, such as Wlan0, and lack the breadth found in the PC. This limitation restricts the depth of forensic analysis that can be performed on the RPI5.

When it comes to application logs, both devices capture logs related to various attack tools like PowerShell Empire, multi/handler, and Koadic. However, the specific logs and their availability differ between the platforms, indicating that while both devices can log similar types of activities, the details and accessibility of these logs vary.

Live memory analysis presents a significant challenge for the RPI5, as the Volatility tool does not support its architecture, making live memory analysis difficult or impossible. In contrast, the PC supports live memory analysis with tools like Volatility, providing detailed insights into the system’s state during forensic investigations. This difference underscores the PC’s advantage in forensic memory analysis.

Finally, network traffic analysis is consistent across both devices, with tools like Wireshark effectively capturing relevant data. However, the contextual information provided by logs and memory analysis is more detailed for the PC, offering a more comprehensive view of the attacks. The differences in system log analysis further highlight the PC’s capability to offer detailed forensic examinations, while the RPI5’s limited logs restrict the scope of analysis.

4.2. Challenges with Raspberry Pi

The current forensic examination of hacker-oriented systems, using a traditional PC running Kali Linux and a Raspberry Pi 5, affords an unparalleled opportunity to assess how forensic artefacts will change across platforms with distinct hardware architectures and functionalities. Kali Linux remains the favourite choice for cybercriminals and current trends show an important shift towards the use of SBC such as Raspberry which the Cyber Forensics community is not ready yet to cope with this shift is marked by differences in both the level and type of forensic data available due to their base design, hardware, and software composition.

The most significant challenge encountered during this investigation was related to the analysis of RAM in the context of Raspberry Pi when compared to Desktop PC where acquiring RAM images was a relatively straightforward process. However, when dealing with Raspberry Pi and IoT devices in general, the process became more complex. We tested fourteen different tools to analyse Linux evidence, and only two, Rekall and Volatility, could handle Linux images. Unfortunately, Rekall has not been updated since November 2017, rendering it less effective in producing reliable results. Volatility, on the other hand, encounters issues with Linux symbols, requiring the creation of a symbol table using Dwarf2Jason for each Linux version. This process is problematic because the tool does not keep up with the frequent updates of the Linux operating system, limiting its applicability depending on the version in use. For the Raspberry Pi, the challenge was even more pronounced. The Volatility tool does not support the ARM architecture embedded in the Raspberry Pi, making it impossible to analyse live memory from the device. This limitation severely restricts the ability to perform comprehensive forensic analysis on the Raspberry Pi, highlighting a critical gap in the available forensic tools for IoT devices.

4.3. Addressing Research Questions

For RQ1, the forensic procedures vary considerably between traditional PCs and IoT devices such as Raspberry Pi because of the differences in their hardware designs, operating systems, and data storage capacities. Traditional computers, which usually have stronger hardware and storage capabilities, enable thorough forensic examination utilising a wide variety of tools and procedures [25]. Their logging techniques are comprehensive, facilitating the tracking of user actions and system operations. On the other hand, Raspberry Pi devices present difficulties in forensic investigations because of their simplified designs (ARCH architecture) and restricted storage capacity. A significant number of forensic tools do not have compatibility with IoT devices, and the data stored is often inadequate for doing thorough analysis. Acquiring live memory from IoT devices is a more intricate and less dependable operation compared to traditional PCs.

For RQ2, the significant distinctions in terms of forensic artefacts difference between traditional PCs and Raspberry Pi devices are due to the Data Storage Capacity and hardware architecture. Traditional computers have a greater capacity to store data and maintain more comprehensive records of user actions and system operations. This encompasses comprehensive system logs, application logs, and user-generated data, which are essential for forensic investigations. PCs use logging practices that employ strong systems to capture extensive information about system and network operations. Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as Raspberry Pi, sometimes possess restricted logging capabilities, leading to a reduced quantity and quality of artefacts. Conventional computers have a far higher capability for doing live memory analysis compared to other devices. Volatility Plugins are capable of extracting intricate information about active processes and system conditions from memory dumps. However, IoT devices have difficulties when it comes to memory analysis because of compatibility concerns with forensic tools.

For RQ3, the current challenges and limitations in weaponized IoT forensics include:

Tool Compatibility: Many existing forensic tools are not compatible with the diverse architectures and operating systems used by IoT devices, such as the ARCH architecture in Raspberry Pi.

Data Retention and Storage: IoT devices typically have limited storage capacity and simplified logging mechanisms, which result in insufficient forensic data retention.

Live Memory Analysis: Acquiring and analysing live memory from IoT devices is challenging due to tool incompatibility and the technical complexity of configuring existing tools for different architectures.

In summary, traditional PCs provided a robust platform for forensic investigations, offering extensive data retention and tool compatibility. In contrast, IoT devices like the Raspberry Pi posed significant challenges due to limited tool support, reduced data retention, and restricted memory analysis capabilities. These findings underscore the need for the development of specialised forensic tools and methodologies tailored to the unique characteristics of IoT devices to enhance their forensic investigation potential.

5. Conclusion and Future Works

In conclusion, our investigation underscores the significant differences in forensic capabilities between traditional PCs and Raspberry Pi devices. While PCs offer a robust basis for logging and extensive data retention capabilities, Raspberry Pi devices are hampered by limited storage, less detailed logs, and poor compatibility with existing forensic tools. These limitations, particularly live memory analysis, highlight the need for more advanced tools that can accommodate the unique architectures of IoT devices like the Raspberry Pi. Overall, Kali Linux running on the PC and Raspberry Pi 5 each potentially provide a wide range of forensic artefacts. However, there are some fundamental differences in several respects: for example, the availability of multiple partitions, full configuration files, and of course, live memory offers a much more textured forensic environment when it comes to the PC. Issues such as incomplete boot files, no swap space, and no support with Volatility diminish the forensic environment on the Raspberry Pi. These differences bring out the PC as a more robust forensic platform, while the simplicity of the Raspberry Pi 5 may be an advantage in focused investigations; it certainly presents some constraints for in-depth forensic analysis.

This research was deemed as not requiring the University’s Ethical Committee Approval as it doesn’t fall under any of the cases requiring ethical approval.

Disks’ Forensics Images and Volatile data generated for this research are available upon request.

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 2021.

- Wanic, E. and Rowe, N. (2018). Assessing Deterrence Options for Cyber Weapons, in 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), pp. 13–18. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Torabi, S. , Bou-Harb, E., Assi, C. and Debbabi, M., 2020. A scalable platform for enabling the forensic investigation of exploited IoT devices and their generated unsolicited activities. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 32, p.300922. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Kebande, V.R. , 2022. Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) forensics: The forgotten concept in the race towards industry 4.0. Forensic Science International: Reports, 5, p.100257. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Stoyanova, M. , Nikoloudakis, Y., Panagiotakis, S., Pallis, E. and Markakis, E.K., 2020. A survey on the Internet of Things (IoT) forensics: challenges, approaches, and open issues. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 22(2), pp.1191-1221. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Dunsin, D. , Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2024. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 48, p.301675. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Cook, M. , Marnerides, A., Johnson, C. and Pezaros, D., 2023. A survey on industrial control system digital forensics: challenges, advances and future directions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Nelufule, N. , Singano, T., Masemola, K., Shadung, D., Nkwe, B., Mokoena, J.2024. An Adaptive Digital Forensic Framework for the Evolving Digital Landscape in Industry 4.0 and 5.0, 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), pp.1686-1693, 2024. [CrossRef]

- 2028.

- Case, A. and Richard III, G.G., 2017. Memory forensics: The path forward. Digital investigation, 20, pp.23-33. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Wanic, E. and Rowe, N. (2018). Assessing Deterrence Optinos for Cyber Weapons. in 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), pp. 13–18. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Stoyanova, M. , Nikoloudakis, Y., Panagiotakis, S., Pallis, E. and Markakis, E. K. 2020. A Survey on the Internet of Things (IoT) Forensics: Challenges, Approaches, and Open Issues’, IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 22(2), pp. 1191–1221. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Cusack, B. , Tian, Z. and Kyaw, A.K., 2017. Identifying DOS and DDOS attack origin: IP traceback methods comparison and evaluation for IoT. In Interoperability, Safety and Security in IoT: Second International Conference, InterIoT 2016 and Third International Conference, SaSeIoT 2016, Paris, France, October 26-27, 2016, Revised Selected Papers 2 (pp. 127-138). Springer International Publishing. 26 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2021.

- Ghanem, M.C. , Mulvihill, P., Ouazzane, K., Djemai, R. and Dunsin, D., 2023. D2WFP: a novel protocol for forensically identifying, extracting, and analysing deep and dark web browsing activities. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 3(4), pp.808-829. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Ghanem, M.C. , Chen, T.M., Ferrag, M.A. and Kettouche, M.E., 2023. ESASCF: expertise extraction, generalization and reply framework for optimized automation of network security compliance. IEEE Access, 11, pp.129840-129853. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Yevdokymenko, M. , Mohamed, E. and Onwuakpa, P. (2017) ’Ethical hacking and penetration testing using Raspberry PI’, in 2017 4th International Scientific-Practical Conference Problems of Info-communications. Science and Technology (PIC S&T), pp. 179–181. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Mohd Bakry, B. B. , Bt Adenan, A. R. and Mohd Yussoff, Y. B. (2022) ‘Security Attack on IoT RelatedDevices Using Raspberry Pi and Kali Linux’, in 2022 International Conference on Computer and Drone Applications (IConDA), pp. 40–45. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Yudha, F. , Ramadhani, E. and Komaryan, R. M. (2021) ’A Prototype of Portable Digital Forensics Imaging Tools using Raspberry Device’, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 1077(1), p. 012064. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Farzaan, M.A.M. , Ghanem, M.C., El-Hajjar, A. and Ratnayake, D.N., 2024. AI-Enabled System for Efficient and Effective Cyber Incident Detection and Response in Cloud Environments.https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.05602. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2021.

- Dunsin, D. , Ghanem, M.C. and Quazzane, K., 2022. The use of artificial intelligence in digital forensics and incident response in a constrained environment. International Journal of Information and Communication Engineering, 16(8), pp.280-285. https://repository.londonmet.ac.uk/8678/. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2021.

- Kyaw, A. K. , Chen, Y. and Joseph, J. (2015) ’Pi-IDS: evaluation of open-source intrusion detection systems on Raspberry Pi 2’, in 2015 Second International Conference on Information Security and Cyber Forensics (InfoSec). Cape Town: IEEE, pp. 165–170. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Westerlund, O. and Asif, R. (2019) ’Drone Hacking with Raspberry-Pi 3 and WiFi Pineapple: Security and Privacy Threats for the Internet-of-Things’, in 2019 1st International Conference on Unmanned Vehicle Systems-Oman (UVS). Muscat, Oman: IEEE, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- T. Bakhshi. Forensic of Things: Revisiting Digital Forensic Investigations in Internet of Things. 2019 4th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering, Sciences and Technology (ICEEST), Karachi, Pakistan, 2019, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Y. Salem, M. Y. Salem, M. Owda and A. Y. Owda. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Forensics Frameworks for Internet of Things (IoT) Devices. 2023 International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 2023, pp. 89-96. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Mazhar, M.S. , Saleem, Y., Almogren, A., Arshad, J., Jaffery, M.H., Rehman, A.U., Shafiq, M. and Hamam, H., 2022. Forensic analysis on Internet of Things (IoT) device using machine-to-machine (M2M) framework. Electronics, 11(7), p.1126. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Alam M., N. and Kabir, M. S. Forensics in the Internet of Things: Application Specific Investigation Model, Challenges and Future Directions, 2023. 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- 2021.

- Ho, S.M. and Burmester, M. (2021). Cyber Forensics on Internet of Things: Slicing and Dicing Raspberry Pi. International Journal of Cyber Forensics and Advanced Threat Investigations, 2(1). pp.29–49. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).