Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Data Collection and Measurements

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

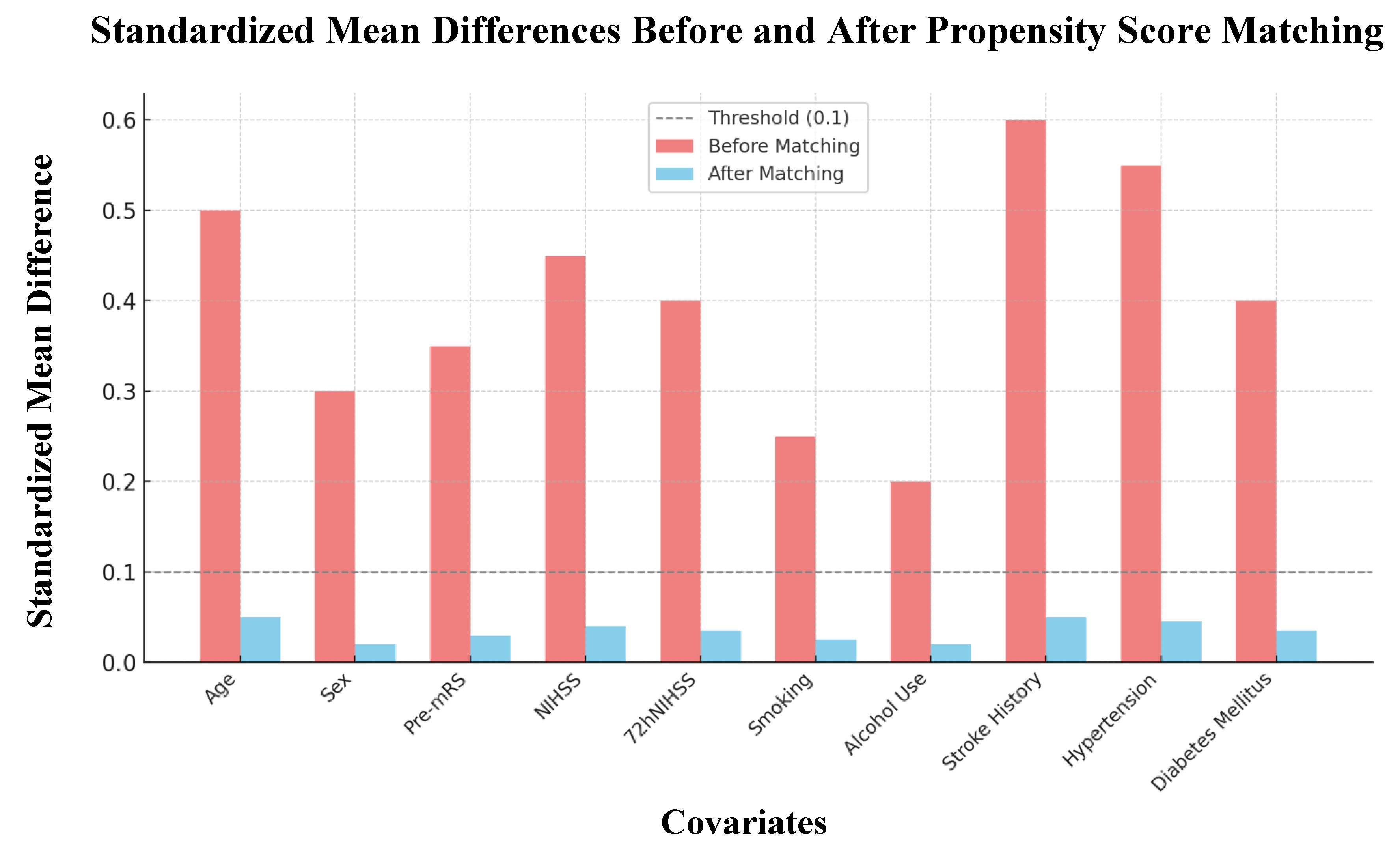

3.2. Propensity Score Matching and Sensitivity Analysis

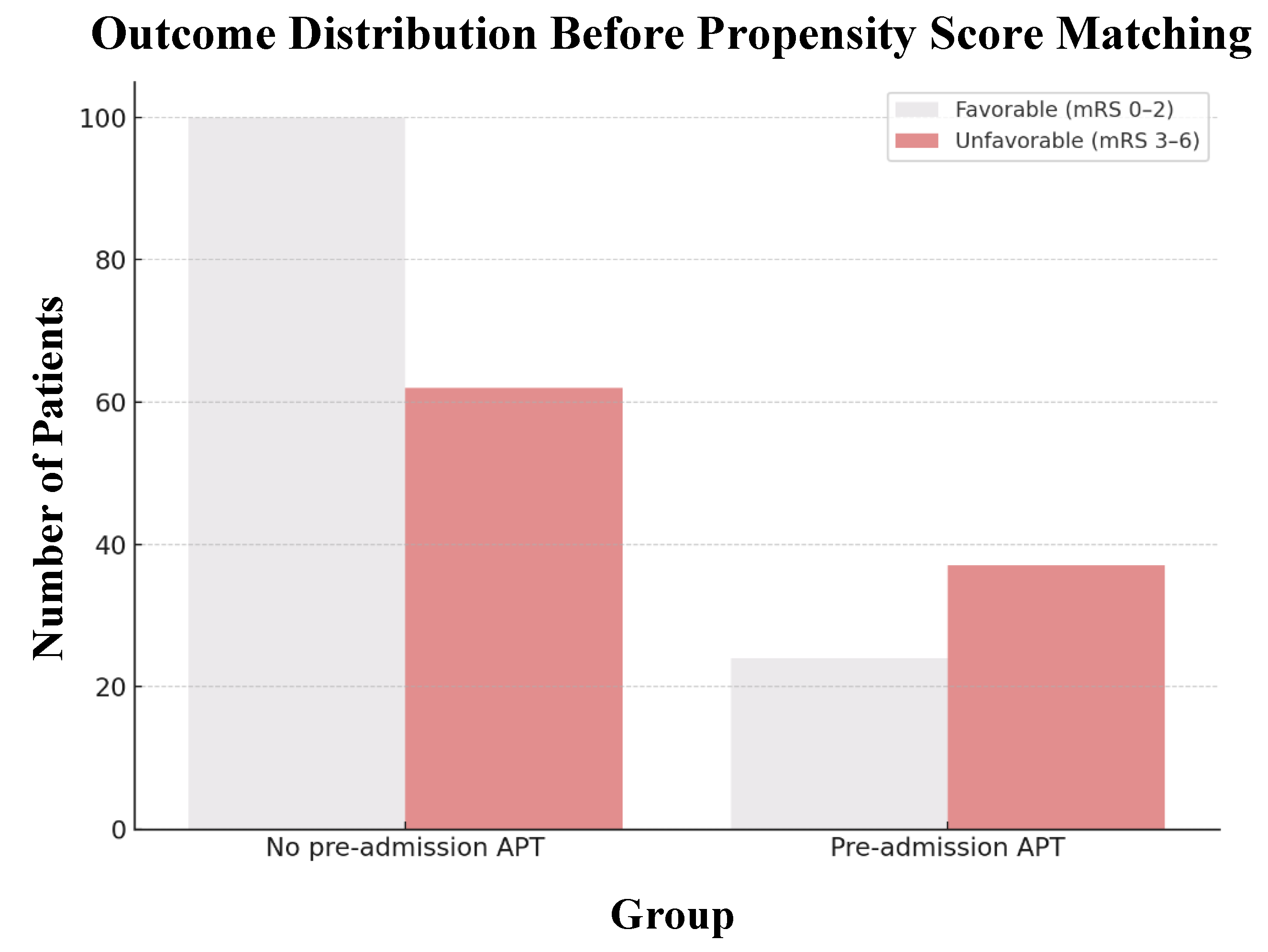

3.3. Functional Outcomes

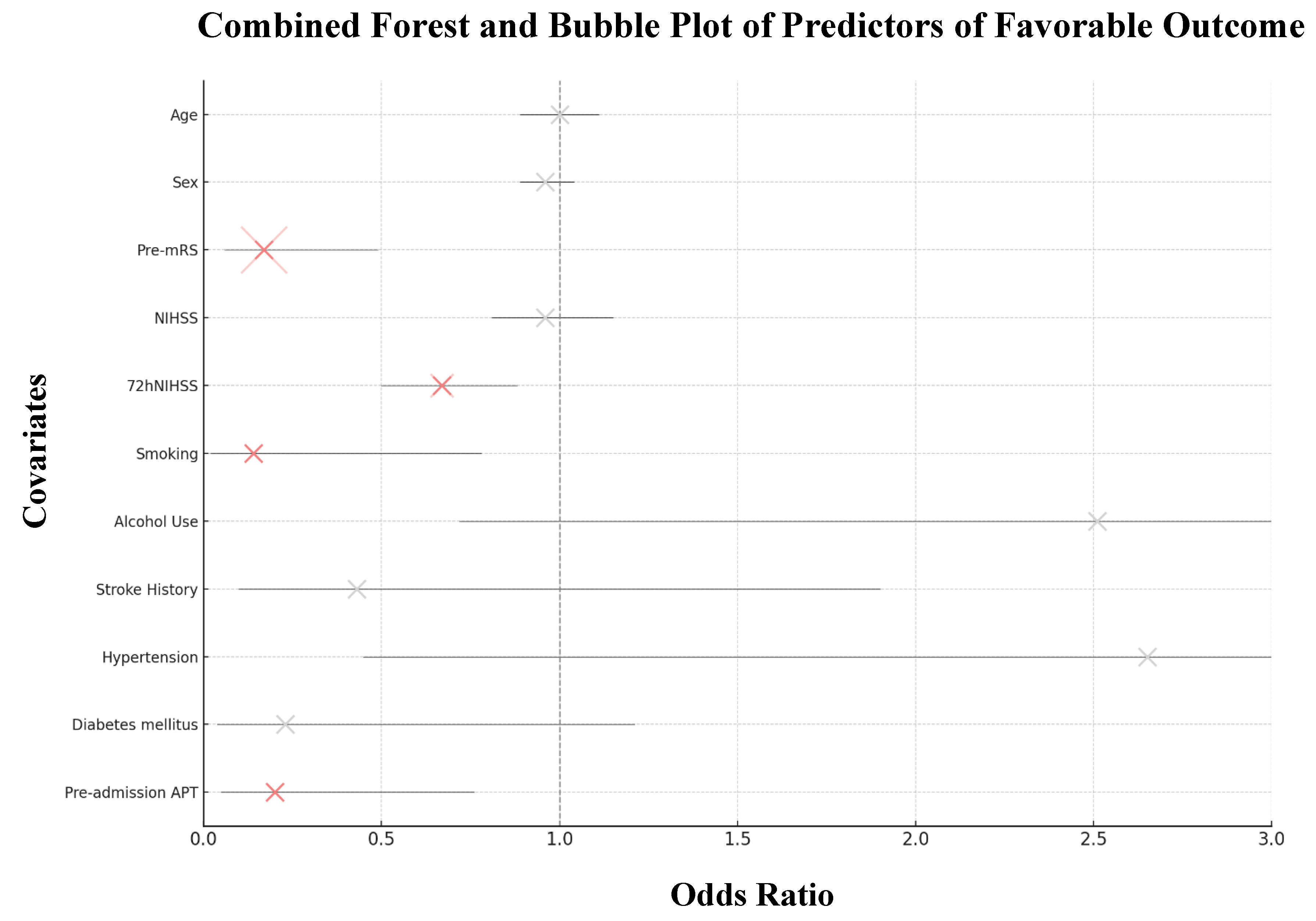

3.4. Logistic Regression and Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison to Current Literature

4.2. Possible Explanations

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| AIS | acute ischemic stroke |

| APT | antiplatelet therapy |

| PSM | propensity score matching |

| mRS | modified Rankin Scale |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| Pre-mRS | pre-morbidity modified Rankin Scale |

| NIHSS | National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale |

| aOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| ESUS | embolic stroke of undetermined source |

| TINL | Transzlációs Idegtudományi Nemzeti Laboratórium |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| TL | thromboylsis |

| MT | mechanical thrombectomy |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SMD | standardized mean difference |

| ADE | average direct effect |

| ACME | average causal mediation effect |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Lee, B.I.; Nam, H.S.; Heo, J.H.; Kim, D.I. Yonsei Stroke Registry. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2001, 12, 145–151. [CrossRef]

- Putaala, J.; Metso, A.J.; Metso, T.M.; Konkola, N.; Kraemer, Y.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaste, M.; Tatlisumak, T. Analysis of 1008 Consecutive Patients Aged 15 to 49 With First-Ever Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2009, 40, 1195–1203. [CrossRef]

- Ornello, R.; Degan, D.; Tiseo, C.; Di Carmine, C.; Perciballi, L.; Pistoia, F.; Carolei, A.; Sacco, S. Distribution and Temporal Trends From 1993 to 2015 of Ischemic Stroke Subtypes. Stroke 2018, 49, 814–819. [CrossRef]

- Saver, J.L. Cryptogenic Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 2065–2074. [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52. [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, M.G.; O’Donnell, M.J.; Khatri, P.; Lang, E.S.; Nguyen-Huynh, M.N.; Schwartz, N.E.; Sonnenberg, F.A.; Schulman, S.; Vandvik, P.O.; Spencer, F.A.; et al. Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy for Ischemic Stroke. Chest 2012, 141, e601S-e636S. [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.G.; Sharma, M.; Mundl, H.; Kasner, S.E.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Swaminathan, B.; Lavados, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Rivaroxaban for Stroke Prevention after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 2191–2201. [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.-C.; Sacco, R.L.; Easton, J.D.; Granger, C.B.; Bernstein, R.A.; Uchiyama, S.; Kreuzer, J.; Cronin, L.; Cotton, D.; Grauer, C.; et al. Dabigatran for Prevention of Stroke after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1906–1917. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yiin, G.S.; Geraghty, O.C.; Schulz, U.G.; Kuker, W.; Mehta, Z.; Rothwell, P.M. Incidence, Outcome, Risk Factors, and Long-Term Prognosis of Cryptogenic Transient Ischaemic Attack and Ischaemic Stroke: A Population-Based Study. Lancet Neurol 2015, 14, 903–913. [CrossRef]

- Bang, O.Y.; Lee, P.H.; Yeo, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Joo, I.S.; Huh, K. Non-Cardioembolic Mechanisms in Cryptogenic Stroke: Clinical and Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Features. Journal of Clinical Neurology 2005, 1, 50. [CrossRef]

- Arsava, E.M.; Helenius, J.; Avery, R.; Sorgun, M.H.; Kim, G.-M.; Pontes-Neto, O.M.; Park, K.Y.; Rosand, J.; Vangel, M.; Ay, H. Assessment of the Predictive Validity of Etiologic Stroke Classification. JAMA Neurol 2017, 74, 419. [CrossRef]

- Grau, A.J.; Weimar, C.; Buggle, F.; Heinrich, A.; Goertler, M.; Neumaier, S.; Glahn, J.; Brandt, T.; Hacke, W.; Diener, H.-C. Risk Factors, Outcome, and Treatment in Subtypes of Ischemic Stroke: The German Stroke Data Bank. Stroke 2001, 32, 2559–2566. [CrossRef]

- Bang, O.Y.; Lee, P.H.; Joo, S.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Joo, I.S.; Huh, K. Frequency and Mechanisms of Stroke Recurrence after Cryptogenic Stroke. Ann Neurol 2003, 54, 227–234. [CrossRef]

- Ntaios, G.; Papavasileiou, V.; Milionis, H.; Makaritsis, K.; Vemmou, A.; Koroboki, E.; Manios, E.; Spengos, K.; Michel, P.; Vemmos, K. Embolic Strokes of Undetermined Source in the Athens Stroke Registry. Stroke 2015, 46, 2087–2093. [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, S.; Messé, S.R.; Kleindorfer, D.; Smith, E.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Xu, H.; Zhao, X.; Lytle, B.; Cigarroa, J.; Schwamm, L.H. Cryptogenic Stroke. Neurol Clin Pract 2020, 10, 396–405. [CrossRef]

- Silimon, N.; Drop, B.; Clénin, L.; Nedeltchev, K.; Kahles, T.; Tarnutzer, A.A.; Katan, M.; Bonati, L.; Salmen, S.; Albert, S.; et al. Ischaemic Stroke despite Antiplatelet Therapy: Causes and Outcomes. Eur Stroke J 2023, 8, 692–702. [CrossRef]

- Sylaja, P.; Nair, S.S.; Pandian, J.; Khurana, D.; Srivastava, M.V.P.; Kaul, S.; Arora, D.; Sarma, P.S.; Singhal, A.B. Impact of Pre-Stroke Antiplatelet Use on 3-Month Outcome After Ischemic Stroke. Neurol India 2021, 69, 1645–1649. [CrossRef]

- Couture, M.; Finitsis, S.; Marnat, G.; Richard, S.; Bourcier, R.; Constant-dits-Beaufils, P.; Dargazanli, C.; Arquizan, C.; Mazighi, M.; Blanc, R.; et al. Impact of Prior Antiplatelet Therapy on Outcomes After Endovascular Therapy for Acute Stroke: Endovascular Treatment in Ischemic Stroke Registry Results. Stroke 2021, 52, 3864–3872. [CrossRef]

- Merlino, G.; Sponza, M.; Gigli, G.L.; Lorenzut, S.; Vit, A.; Gavrilovic, V.; Pellegrin, A.; Cargnelutti, D.; Valente, M. Prior Use of Antiplatelet Therapy and Outcomes after Endovascular Therapy in Acute Ischemic Stroke Due to Large Vessel Occlusion: A Single-Center Experience. J Clin Med 2018, 7, 518. [CrossRef]

- van de Graaf, R.A.; Zinkstok, S.M.; Chalos, V.; Goldhoorn, R.-J.B.; Majoie, C.B.; van Oostenbrugge, R.J.; van der Lugt, A.; Dippel, D.W.; Roos, Y.B.; Lingsma, H.F.; et al. Prior Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Endovascular Treatment for Acute Ischemic Stroke: Results from the MR CLEAN Registry. International Journal of Stroke 2021, 16, 476–485. [CrossRef]

- Xian, Y.; Federspiel, J.J.; Grau-Sepulveda, M.; Hernandez, A.F.; Schwamm, L.H.; Bhatt, D.L.; Smith, E.E.; Reeves, M.J.; Thomas, L.; Webb, L.; et al. Risks and Benefits Associated With Prestroke Antiplatelet Therapy Among Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Treated With Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator. JAMA Neurol 2016, 73, 50. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.-H.; Kim, C.; Sung, J.H.; Han, S.-W.; Minwoo Lee; Oh, M.S.; Yu, K.-H.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, S.-H. Effect of Pre-Stroke Antiplatelet Use on Stroke Outcomes in Acute Small Vessel Occlusion Stroke with Moderate to Severe White Matter Burden. J Neurol Sci 2024, 456, 122837. [CrossRef]

- Sanossian, N.; Saver, J.L.; Rajajee, V.; Selco, S.L.; Kim, D.; Razinia, T.; Ovbiagele, B. Premorbid Antiplatelet Use and Ischemic Stroke Outcomes. Neurology 2006, 66, 319–323. [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; R.; Jing, J.; Wang, A.; Mo, D.; Gao, F.; Ma, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Z. Safety and Efficacy of Oral Antiplatelet for Patients Who Had Acute Ischaemic Stroke Undergoing Endovascular Therapy. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2021, 6, 230–237. [CrossRef]

- Krieger, P.; Melmed, K.R.; Torres, J.; Zhao, A.; Croll, L.; Irvine, H.; Lord, A.; Ishida, K.; Frontera, J.; Lewis, A. Pre-Admission Antithrombotic Use Is Associated with 3-Month MRS Score after Thrombectomy for Acute Ischemic Stroke. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2022, 54, 350–359. [CrossRef]

- SMYTH, S.S.; MCEVER, R.P.; WEYRICH, A.S.; MORRELL, C.N.; HOFFMAN, M.R.; AREPALLY, G.M.; FRENCH, P.A.; DAUERMAN, H.L.; BECKER, R.C. Platelet Functions beyond Hemostasis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2009, 7, 1759–1766. [CrossRef]

- Dowlatshahi, D.; Hakim, A.; Fang, J.; Sharma, M. Pre Admission Antithrombotics Are Associated with Improved Outcomes Following Ischaemic Stroke: A Cohort from the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. International Journal of Stroke 2009, 4, 328–334. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Ye, H.; Wang, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Antiplatelet Therapy, Cerebral Microbleeds, and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2018, 49, 1751–1754. [CrossRef]

- Eikelboom, J.W.; Hirsh, J.; Spencer, F.A.; Baglin, T.P.; Weitz, J.I. Antiplatelet Drugs. Chest 2012, 141, e89S-e119S. [CrossRef]

| Before Propensity Score Matching | After Propensity Score Matching | |||||

|

Pre-admission APT n = 61 |

No pre-admission APT n = 162 |

P-value |

Pre-admission APT n = 61 |

No pre-admission APT n = 61 |

P-value | |

| Patient Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD Sex, male, n (%) |

69.87 ± 11.20 30 (49.2%) |

64.76 ± 13.26 73 (45.1%) |

0.005 0.690 |

69.87 ± 11.20 30 (49.2%) |

72.10 ± 9.35 24 (39.3%) |

0.235 0.362 |

| Clinical Variables | ||||||

| Pre-mRS score, mean ± SD NIHSS score, mean ± SD 72hNIHSS score, mean ± SD Etiology, ESUS, n (%) Onset-to-door time, mean ± SD Plasma glucose, mean ± SD |

0.61 ± 1.24 6.5 ± 6.1 4.2 ± 5.2 11 (18.0%) 484.44 ± 1116 7.62 ± 2.47 |

0.46 ± 1.04 6.6 ± 5.5 4.1 ± 5.2 28 (17.3%) 600.56 ± 1073 7.12 ± 2.27 |

0.404 0.926 0.852 1.00 0.486 0.175 |

0.61 ± 1.24 6.5 ± 6.1 4.2 ± 5.2 11 (18.0%) 484.44 ± 1116 7.62 ± 2.47 |

1.05 ± 1.48 7.6 ± 5.7 4.7 ± 5.5 6 (9.8%) 398.10 ± 456 7.66 ± 1.88 |

0.078 0.290 0.601 0.296 0.577 0.925 |

| Medical History, n (%) | ||||||

| Current Smoking Alcohol Use Stroke history Hypertension Diabetes mellitus |

14 (23.0%) 24 (39.3%) 18 (29.5%) 53 (86.9%) 25 (41.0%) |

57 (35.2%) 73 (45.1%) 4 (2.5%) 118 (72.8%) 34 (21.0%) |

0.113 0.538 <0.001 0.042 0.004 |

14 (23.0%) 24 (39.3%) 18 (29.5%) 53 (86.9%) 25 (41.0%) |

16 (26.2%) 20 (32.8%) 15 (24.6%) 56 (91.8%) 32 (52.5%) |

0.833 0.572 0.684 0.557 0.276 |

| Recanalization therapy, n (%) | ||||||

| TL MT TL + MT |

25 (41.0%) 10 (16.4%) 5 (8.2%) |

48 (29.6%) 36 (22.2%) 11 (6.8%) |

0.147 0.439 0.943 |

25 (41.0%) 10 (16.4%) 5 (8.2%) |

31 (50.8%) 5 (8.2%) 4 (6.6%) |

0.364 0.270 1.00 |

| OR | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Demographics | ||||

| Age, years Sex, male |

0.96 1.03 |

0.89 to 1.04 0.30 to 3.55 |

0.308 0.964 |

|

| Clinical Variables | ||||

| Pre-mRS score NIHSS score 72hNIHSS score Etiology, ESUS Onset-to-door time Plasma glucose |

0.17 0.96 0.67 0.39 1.00 1.12 |

0.06 to 0.49 0.81 to 1.15 0.50 to 0.88 0.06 to 2.38 1.00 to 1.00 0.78 to 1.61 |

<0.001 0.674 0.004 0.306 0.663 0.536 |

|

| Medical History | ||||

| Current Smoking Alcohol Use Stroke history Hypertension Diabetes mellitus |

0.14 2.51 0.43 2.65 0.23 |

0.02 to 0.78 0.72 to 8.70 0.10 to 1.90 0.45 to 15.6 0.04 to 1.21 |

0.025 0.148 0.263 0.282 0.083 |

|

| Recanalization therapy | ||||

| TL MT TL + MT |

2.28 1.08 5.08 |

0.49 to 10.5 0.12 to 9.95 0.53 to 48.8 |

0.290 0.944 0.159 |

|

| Estimate | Lower CI | Upper CI | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADE no pre-admission APT | -0.037 | -0.021 | 0.128 | 0.684 |

| ADE pre-admission APT | -0.037 | -0.020 | 0.127 | 0.684 |

| ACME no pre-admission APT | -0.015 | -0.080 | 0.041 | 0.596 |

| ACME pre-admission APT | -0.014 | -0.080 | 0.039 | 0.596 |

| Total Effect | -0.051 | -0.230 | 0.127 | 0.534 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).