Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

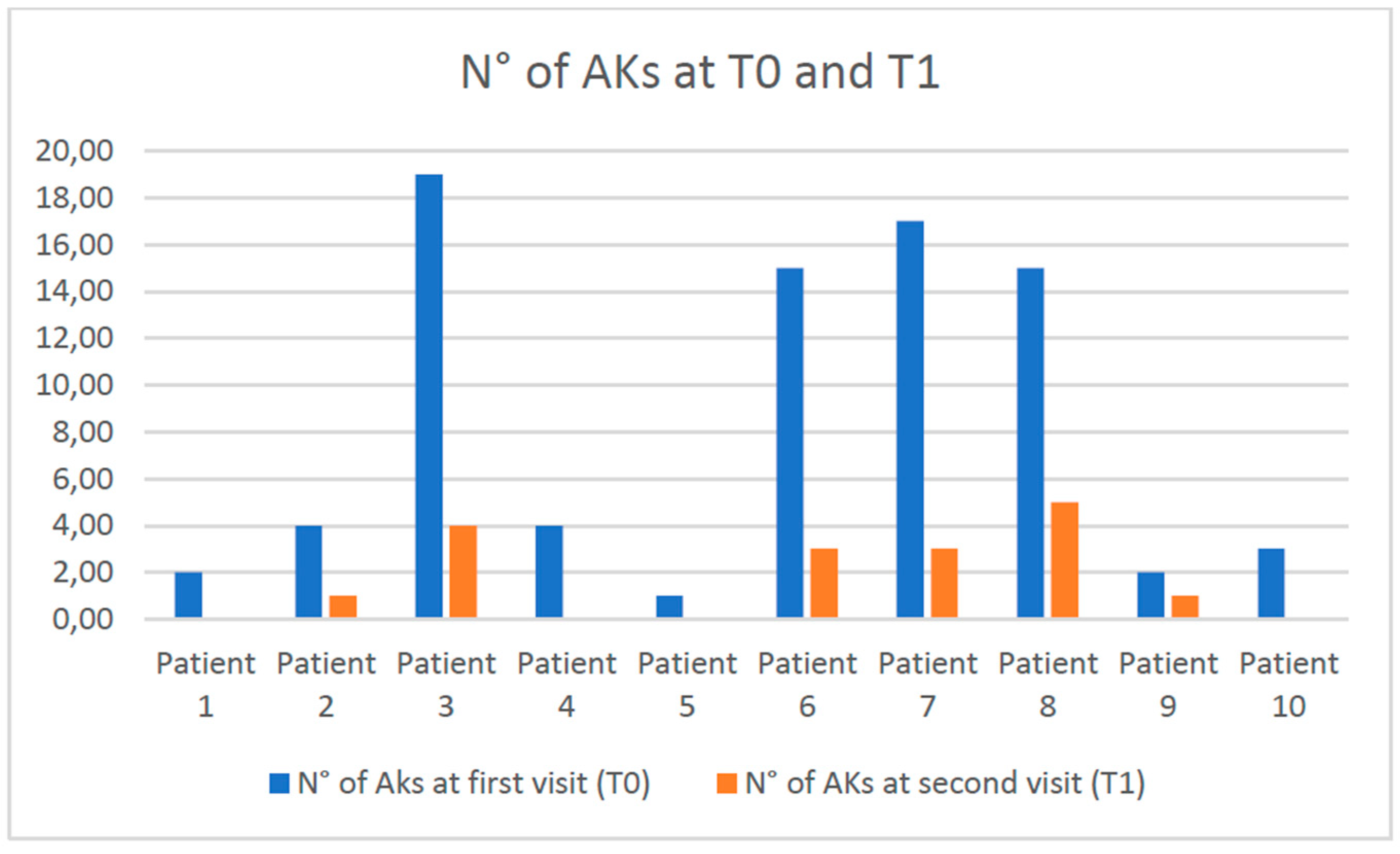

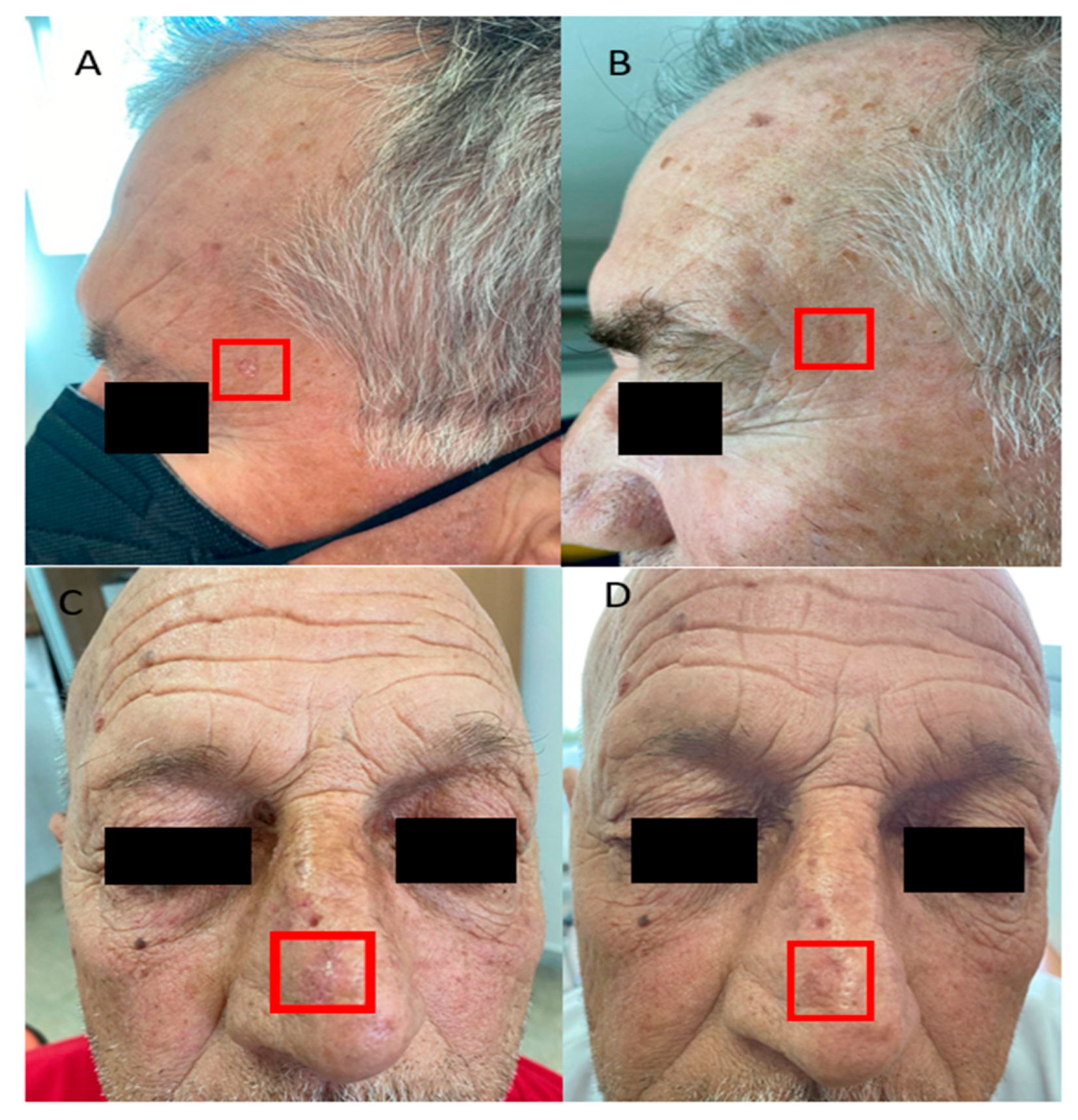

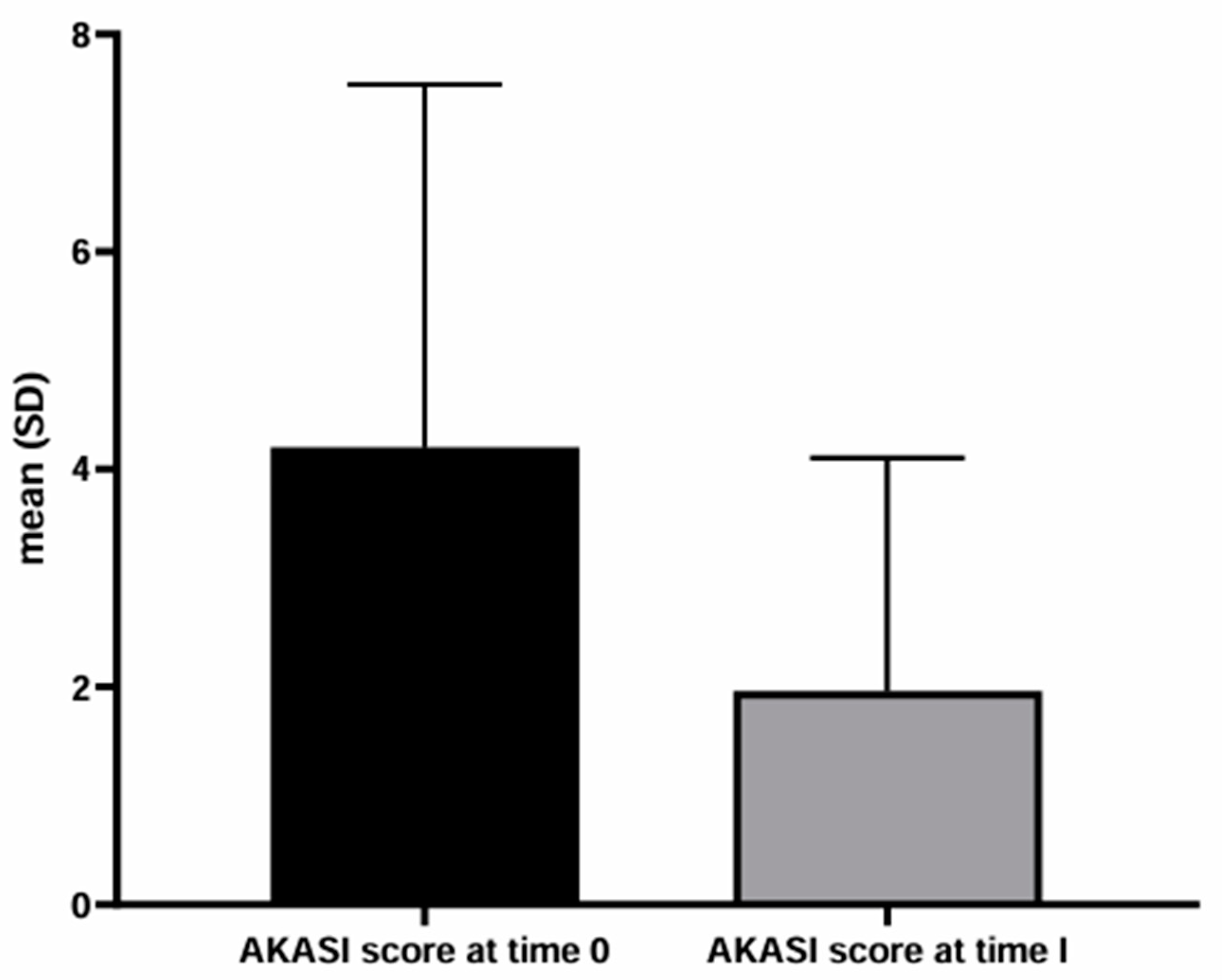

Background/Objectives: People living with HIV (PLWH) are more susceptible than immunocompetent people to non-melanoma skin cancers. These tumors can arise de novo or from precancerous lesions, such as actinic keratosis (AKs). The AKs management in PLWH has not been widely discussed in the literature. More specifically, the efficacy of AKs treatment in PLWH with modern topical drugs, such as tirbanibulin, is limited. The present work aims to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of AKs treatment with tirbanibulin 1% ointment in PLWH. Methods: We retrospectively collected the data of the PLWH who visited the Dermatology Department of the Policlinico Riuniti (Foggia, Italy) between September 2023 and September 2024. PLWH who received the diagnosis of AKs and underwent treatment with tirbanibulin 1% ointment were studied. To assess the severity of AKs, the number of AKs and the AKs area and severity index (AKASI) score were calculated at the time of diagnosis (T0) and after treatment (T1). Results: Ten PLWH were found to have AKs and received topical therapy with tirbanibulin 1% ointment. On average, al T0, the number of lesions was 8.2 and the AKASI score was 4.20; at T1, the number of AKs was 1.7 and the AKASI score was 1.5. Only two patients reported a mild inflammatory reaction to applying tirbanibulin 1% ointment. Conclusions: The rate of satisfactory responses was 80%, in line with a recent multicentric Italian study performed on immunocompetent patients. Our results confirm the efficiacy and tolerability of tirbanibulin 1% ointment in treating AKs also in PLWH.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AK | Actinic keratosis |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| NMSC | Non-melanoma skin cancer |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| AKASI | Actinic keratosis area and severity index |

References

- Röwert-Huber, J.; Patel, M.J.; Forschner, T.; Ulrich, C.; Eberle, J.; Kerl, H.; Sterry, W.; Stockfleth, E. Actinic keratosis is an early in situ squamous cell carcinoma: a proposal for reclassification. Br J Dermatol 2007, 156 Suppl 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandolf, L.; Peris, K.; Malvehy, J.; Mosterd, K.; Heppt, M.V.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Berking, C.; Arenberger, P.; Bylaite-Bučinskiene, M. , Del Marmol, V.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of actinic keratoses, epithelial UV-induced dysplasia and field cancerization on behalf of European Association of Dermato-Oncology, European Dermatology Forum, European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology and Union of Medical Specialists (Union Européenne des Médecins Spécialistes). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024, 18, 1024–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman, A.B.; Mones, J.M. Solar (actinic) keratosis is squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol 2006, 155, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, R.S.; Sebastian, S.; Jiang, Z.; Nindl, I.; Larson, R. Gene expression patterns of normal human skin, actinic keratosis, and squamous cell carcinoma: a spectrum of disease progression. Arch Dermatol 2010, 146, 288–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thamm, J.R.; Schuh, S.; Welzel, J. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Actinic Keratosis. What is New for The Management for Sun-Damaged Skin. Dermatol Pract Concept 2024, 14, e2024146S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, M.; Han, W.; Maddox, J.; Soltani, K.; Shea, C.R.; Freeman, D.M.; He, Y.Y. UVB-induced ERK/AKT-dependent PTEN suppression promotes survival of epidermal keratinocytes. Oncogene 2010, 29, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellou, P.; Zaravinos, A.; Zioga, M.; Stratigos, A.; Baritaki, S.; Soufla, G.; Zoras, O.; Spandidos, D.A. Genomic instability, mutations and expression analysis of the tumour suppressor genes p14(ARF), p15(INK4b), p16(INK4a) and p53 in actinic keratosis. Cancer Lett 2008, 264, 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohil, S.C.; van der Leest, R.J.; Dowlatshahi, E.A.; Hofman, A.; de Vries, E.; Nijsten, T. Prevalence of actinic keratosis and its risk factors in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol 2013, 133, 1971–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, W.; Liu, J.; Zha, X. Risk Factors for Actinic Keratoses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J Dermatol 2022, 67, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, G.; Drago, F.; Broccolo, F.; Pastorino, A.; Pizzatti, L.; Atzori, L.; Pilloni, L.; Santinelli, D.; Urbani, A.; Parodi, A.; et al. Oncoviruses and melanomas: A retrospective study and literature review. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e27924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aldabagh, B.; Yu, J.; Arron, S.T. Role of human papillomavirus in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014, 70, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, E.A.; Abernethy, M.L.; Kulp-Shorten, C.; Callen, J.P.; Glazer, S.D.; Huntley, A.; McCray, M.; Monroe, A.B.; Tschen, E.; Wolf, J.E. Jr. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluating masoprocol cream in the treatment of actinic keratoses on the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991, 24, 738–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmady, S.; Jansen, M.H.E.; Nelemans, P.J.; Kessels, J.P.H.M.; Arits, A.H.M.M.; de Rooij, M.J.M.; Essers, B.A.B.; Quaedvlieg, P.J.F.; Kelleners-Smeets, N.W.J.; et al. Risk of Invasive Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma After Different Treatments for Actinic Keratosis: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol 2022, 158, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarese, G.; Trave, I.; Herzum, A.; Parodi, A.; Drago, F. Dermatological manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus systemic infection: a case report and literature review. Int J Dermatol 2020, 59, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Silverberg, M.J.; Abrams, D.I. Non-AIDS-Defining Malignancies in the HIV-Infected Population. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2014, 16, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, M.S.; Cole, S.R.; Kirk, G.D.; Poole, C. A meta-analysis of the incidence of non-AIDS cancers in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009, 52, 611–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Merlo, G.; Trave, I.; Javor, S.; Rebora, A.; Parodi, A. Oral and cutaneous manifestations of viral and bacterial infections: Not only COVID-19 disease. Clin Dermatol 2021, 39, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trave, I.; Ciccarese, G.; Gasparini, G.; Canta, R.; Serviddio, G.; Herzum, A.; Drago, F.; Parodi, A. Skin cancers in solid organ transplant recipients: a retrospective study on 218 patients. Transpl Immunol 2023, 80, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojute, F.; Zakaria, A.; Zullo, S.; Klufas, D.; Amerson, E. Skin cancer risk across racial/ethnic groups among solid organ transplant recipients in the United States, 2000-2022. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024, S0190-9622, 03235-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniowski, P.; Griffith, C.; Young, P.A. Update on skin cancer prevention modalities and screening protocols in solid organ transplant recipients: a scoping review. Arch Dermatol Res 2024, 317, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, M.J.; Chao, C.; Leyden, W.A.; Xu, L.; Tang, B.; Horberg, M.A.; Klein, D.; Quesenberry, C.P. Jr.; Towner, W.J.; Abrams, D.I. HIV infection and the risk of cancers with and without a known infectious cause. AIDS 2009, 23, 2337–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shu, G.; Wang, S. The risk of non-melanoma skin cancer in HIV-infected patients: new data and meta-analysis. Int J STD AIDS 2016, 27, 568–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarchoan, R.; Uldrick, T.S. HIV-Associated Cancers and Related Diseases. N Engl J Med 2018, 378, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Parodi, A. Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N Engl J Med 2016, 374, 789–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dréno, B.; Amici, J.M.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Cribier, B.; Claudel, J.P.; Richard, M.A. AKTeam™. Management of actinic keratosis: a practical report and treatment algorithm from AKTeam™ expert clinicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014, 28, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinehr, C.P.H.; Bakos, R.M. Actinic keratoses: review of clinical, dermoscopic, and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol 2019, 94, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTemple, V.K.; Walter, A.; Bredemeier, S.; Gutzmer, R.; Schaper-Gerhardt, K. Anti-tumor effects of tirbanibulin in squamous cell carcinoma cells are mediated via disruption of tubulin-polymerization. Arch Dermatol Res 2024, 316, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagner, A.; Delgado, M.B.; Tallichet-Blanc, C.; Chan, J.S.; Sng, M.K.; Mottaz, H.; Degueurce, G.; Lippi, Y.; Moret, C.; Baruchet, M.; Antsiferova, M.; et al. Src is activated by the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ in ultraviolet radiation-induced skin cancer. EMBO Mol Med 2014, 6, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Kempers, S.; Lain, E.; Schlesinger, T.; Tyring, S.; Forman, S.; Ablon, G.; Martin, G.; Wang, H.; Cutler, D.L.; et al. Phase 3 Trials of Tirbanibulin Ointment for Actinic Keratosis. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European AIDS Clinical Society Guidelines. Version 11.1, October 2022. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/guidelines/eacs-guidelines/ (accessed on day month year).

- Masiá, M.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz de la Tabla, A.; Gutiérrez, F. Cancer screening in people living with HIV. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 20590–20603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosche, C.; Chio, M.T.W.; Arron, S.T. Skin cancer and HIV. Clin Dermatol 2023, S0738-081X, 00258-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirschka, T.; Pellacani, G.; Micali, G.; Malvehy, J.; Stratigos, A.J.; Casari, A.; Schmitz, L.; Gupta, G. Athens AK Study Group. A proposed scoring system for assessing the severity of actinic keratosis on the head: actinic keratosis area and severity index. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017, 31, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzaro, G.; Carugno, A.; Bortoluzzi, P.; Buffon, S.; Astrua, C.; Zappia, E.; Trovato, E.; Caccavale, S.; Pellegrino, V.; Paolino, G.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tirbanibulin 1% ointment in the treatment of cancerization field: a real-life Italian multicenter observational study of 250 patients. Int J Dermatol 2024, 63, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellacani, G.; Schlesinger, T.; Bhatia, N.; Berman, B.; Lebwohl, M.; Cohen, J.L.; Patel, G.K.; Kunstfeld, R.; Hadshiew, I.; et al. Efficacy and safety of tirbanibulin 1% ointment in actinic keratoses: Data from two phase-III trials and the real-life clinical practice presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024, 38 Suppl 1, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roewert-Huber, J.; Stockfleth, E.; Kerl, H. Pathology and pathobiology of actinic (solar) keratosis - an update. Br J Dermatol 2007, 157, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiyad, Z.; Marquart, L.; O'Rourke, P.; Green, A.C. The natural history of actinic keratoses in organ transplant recipients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017, 76, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Evans, R.; Maurer, T.; Muhe, L.M.; Freeman, E.E. Treatment of Dermatological Conditions Associated with HIV/AIDS: The Scarcity of Guidance on a Global Scale. AIDS Res Treat 2016, 2016, 3272483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez M. Skin Cancers in Patients with HIV. In: Nouri K. eds. Skin Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide. McGraw-Hill Education; 2023. Available online: https://dermatology.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3257§ionid=271456253 (Accessed December 21, 2024).

- Silverberg, M.J.; Leyden, W.; Warton, E.M.; Quesenberry, C.P. Jr.; Engels, E.A.; Asgari, M.M. HIV infection status, immunodeficiency, and the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013, 105, 350–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venanzi Rullo, E.; Maimone, M.G.; Fiorica, F.; Ceccarelli, M.; Guarneri, C.; Berretta, M.; Nunnari, G. Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer in People Living With HIV: From Epidemiology to Clinical Management. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 689789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Wang, C.; Friedman, D.J.; Pardee, A.B. Reciprocal modulations between p53 and Tat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995, 92, 5461–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, J.P.; Leslie, K.S. Skin cancer risk in people living with HIV: a call for action. Lancet HIV 2024, 11, e60–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.; Urban, M.I.; O'Connell, D.; Yu, X.Q.; Beral, V.; Newton, R.; Ruff, P.; Donde, B.; Hale, M.; Patel, M.; et al. The spectrum of human immunodeficiency virus-associated cancers in a South African black population: results from a case-control study, 1995-2004. Int J Cancer 2008, 122, 2260–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Baseline features of the studied patients | |

| Number of patients | 10 |

| Male sex | 10 |

| Mean age ± SD (years) | 69.5 ± 5.8 |

| Year from HIV diagnosis (years) | 27.2 ± 8.7 |

| Fitzpatrick phototype | |

| II | 8 (80%) |

| III | 2 (20%) |

| History of sunburns in childhood | 6 (60%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| hypertension | 2 (20%) |

| hypercholesterolemia | 3 (30%) |

| liver transplantation | 1 (10%) |

| HBV, HCV infection | 1 (10%) |

| Use of potentially photosensitizing drugs | 1 (10%) |

| History of non melanoma skin cancers | 1 (10%) |

| Previous AKs | 2 (20%) |

| Site of Aks | |

| only face | 4 (40%) |

| only scalp | 1 (10%) |

| face and scalp | 3 (30%) |

| other sites | 1 (10%) |

| face and other sites | 1 (10%) |

| Olsen grade of Aks at T0 | |

| I | 3 (30%) |

| I-II | 7 (70%) |

| II | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).