Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

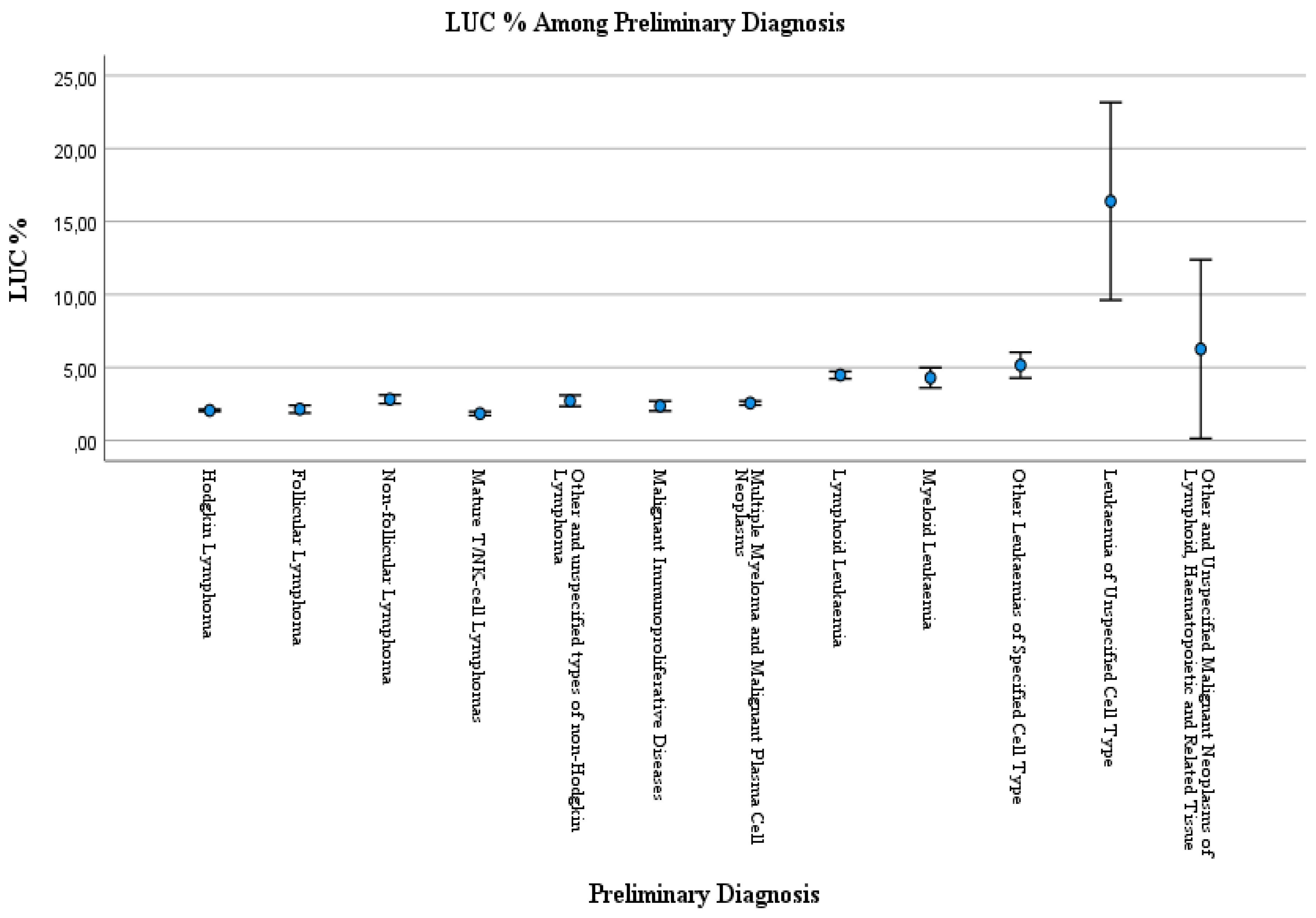

Large unstained cells (LUC) is a differential count parameter reported by routine hematology analysis, and LUC percentages (LUC %) reflect active lymphocytes and peroxidase-negative cells. We aimed the evaluate the LUC % parameter in routine practice towards malignant neoplasms, stated or presumed to be primary, of lymphoid, haematopoietic, and related tissue. LUC analysis was performed with Siemens ADVIA® 2120 Hematology System. Data were obtained from Ankara Bilkent City Hospital’s laboratory information system. A statistical difference in the LUC % data in the case of LUC % <4.5 and LUC % ≥4.5 among preliminary diagnoses was observed (p<0.001). According to the Kruskal-Wallis test, a statistical difference was observed between preliminary diagnosis and LUC % values (p<0.001). The One-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction was performed for post hoc multiple comparisons of the preliminary diagnosis among LUC%. LUC % was higher in Hodgkin Lymphoma patients than Myeloid leukaemia patients (p=0.002). LUC % was higher in the Lymphoid leukaemia patients than in the patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (p<0.001), Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (p<0.001), Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms (p<0.001). LUC % was higher in patients with leukemia unspecified cell type than Hodgkin lymphoma (p<0.001), Follicular lymphoma (p<0.001), Non-follicular lymphoma (p<0.001), Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas (p<0.001), Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (p<0.001), Malignant immunoproliferative diseases (p<0.001), Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms (p<0.001), Lymphoid leukaemia (p<0.001), Myeloid leukaemia (p<0.001), Other leukaemias of specified cell type patients (p<0.001). Prospective studies may be useful in assessing LUC%.

Keywords:

Introduction:

Material and Methods:

Statistical Analyses

Results:

Discussion:

Strengths and Limitations:

Conclusions:

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Celkan TT. What does a hemogram say to us? Turkish Archives of Pediatrics/Türk Pediatri Arşivi. 2020;55(2):103.

- George-Gay B, Parker K. Understanding the complete blood count with differential. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 2003;18(2):96-117. [CrossRef]

- Pepedil Tanrıkulu F, Yanardağ Açık D, Özdemir M. Geriatrik Hastalarda Hematolojik Malignitelerin Dağılımı: Tek Merkez Deneyimi. Medical Journal of Ankara Training & Research Hospital. 2021;54(2).

- Keskin M, Polat SB, Ateş I, Izdeş S, Güner HR, Topaloğlu O, et al. Are neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios and large unstained cells different in hospitalized COVID-19 PCR-positive patients with and without diabetes mellitus? European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences. 2022;26(16).

- Thirup P. LUC, what is that? Clinical chemistry. 1999;45(7):1100-.

- Merter M, Sahin U, Uysal S, Dalva K, Yuksel MK. Role of large unstained cells in predicting successful stem cell collection in autologous stem cell transplantation. Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 2023;62(1):103517. [CrossRef]

- Eren F, Kösem A, Oğuz EF, Ateş SN, Erel O. Evaluation Of Large Unstained Cells (Luc) And Nitric Oxide In Diabetes Mellitus. Ankara Medical Journal. 2022;22(4). [CrossRef]

- O’Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, Wildes KR, Hurdle JF, Ashton CM. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. Health services research. 2005;40(5p2):1620-39. [CrossRef]

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision 2019 [Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en.

- Harris N, Kunicka J, Kratz A. The ADVIA 2120 hematology system: flow cytometry-based analysis of blood and body fluids in the routine hematology laboratory. Laboratory Hematology. 2005;11(1):47-61. [CrossRef]

- Drewinko B, Bollinger P, Brailas C, Moyle S, Wyatt J, Simson E, et al. Flow cytochemical patterns of white blood cells in human haematopoietic malignancies. British journal of haematology. 1987;66(1):27-36. [CrossRef]

- Orazi A, Cattoretti G, Rilke F. The technicon H6000 analyzer discriminates chronic lymphocytic leukemia from other B-cell leukemias through automatic assessment of large unstained cells. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 1990;114(10):1021-4.

- Rabizadeh E, Pickholtz I, Barak M, Isakov E, Zimra Y, Froom P. Acute leukemia detection rate by automated blood count parameters and peripheral smear review. International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 2015;37(1):44-9. [CrossRef]

- Drewinko B, Bollinger P, Brallas C, Wyatt J, Simson E, Trujillo J. Flow cytochemical patterns of white blood cells in human haematopoietic malignancies: II, Chronıc Leukaemıas. British journal of haematology. 1987;67(2):157-65. [CrossRef]

- Lanza F, Moretti S, Latorraca A, Scapoli G, Rigolin F, Castoldi G. Flow cytochemical analysis of peripheral lymphocytes in chronic B-lymphocytic leukemia. Prognostic role of the blast count determined by the H∗ 1 system and its correlation with morphologic features. Leukemia research. 1992;16(6-7):639-46.

- Drewinko B, Bollinger P, Brailas C, Wyatt J, Simson E, Trujillo J. Flow cytochemical patterns of white blood cells in human hematopoietic malignancies: III. Miscellaneous hemopoietic diseases. Blood cells. 1988;13(3):475-86.

- Orazi A, Milanesi B. The technicon H6000 automated hematology analyzer in the diagnosis and classification of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 1990;75(1):87-90.

- Bunyaratvej A, Boonkanta P, Nítiyanant P, Apibal S, Bhamarapravati N. Automated Cytochemistry in Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: A New Method for Determination of Cells from Lymph Node Biopsy. Acta haematologica. 1986;75(4):199-202. [CrossRef]

- Vanker N, Ipp H. Large unstained cells: a potentially valuable parameter in the assessment of immune activation levels in HIV infection. Acta haematologica. 2014;131(4):208-12. [CrossRef]

- Vanker N, Ipp H. The use of the full blood count and differential parameters to assess immune activation levels in asymptomatic, untreated HIV infection. South African Medical Journal. 2014;104(1):45-8. [CrossRef]

- Shin D, Lee MS, Kim DY, Lee MG, Kim DS. Increased large unstained cells value in varicella patients: A valuable parameter to aid rapid diagnosis of varicella infection. The Journal of Dermatology. 2015;42(8):795-9. [CrossRef]

- Butthep P, Bunyaratvej A, Bhamarapravati N. Dengue virus and endothelial cell: a related phenomenon to thrombocytopenia and granulocytopenia in dengue hemorrhagic fever. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health. 1993;24:246-9.

- Nixon D, Parsons A, Eglin R. Routine full blood counts as indicators of acute viral infections. Journal of clinical pathology. 1987;40(6):673-5. [CrossRef]

- Bononi A, Lanza F, Ferrari L, Gusella M, Gilli G, Abbasciano V, et al. Predictive value of hematological and phenotypical parameters on postchemotherapy leukocyte recovery. Cytometry Part B: Clinical Cytometry: The Journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2009;76(5):328-33.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 853 | 49.9 |

| Male | 857 | 50.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 0-18 | 238 | 13.9 |

| 19-64 | 854 | 49.9 |

| 65 and over | 618 | 36.1 |

| LUC % Data | ||

| LUC % <4.5 | 1459 | 85.3 |

| LUC % ≥4.5 | 251 | 14.7 |

| Preliminary Diagnosis | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 201 | 11.8 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 46 | 2.7 |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | 116 | 6.8 |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | 36 | 2.1 |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 251 | 14.7 |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | 9 | 0.5 |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 226 | 13.2 |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 507 | 29.6 |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 279 | 16.3 |

| Other leukaemias of specified cell type | 19 | 1.1 |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | 17 | 1 |

| Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | 3 | 0.2 |

| Female | Male | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 0-18 | 105 | 12.3 | 133 | 15.5 | <0.001 |

| 18-64 | 400 | 46.9 | 454 | 53.0 | |

| 65 and over | 348 | 40.8 | 270 | 31.5 | |

| LUC % Data | |||||

| LUC % <4.5 | 712 | 83.47 | 747 | 87.2 | 0.031 |

| LUC % ≥4.5 | 141 | 16.53 | 110 | 12.8 | |

| Preliminary Diagnosis | |||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 84 | 9.8 | 117 | 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 28 | 3.3 | 18 | 2.1 | |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | 63 | 7.4 | 53 | 6.2 | |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | 25 | 2.9 | 11 | 1.3 | |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 107 | 12.5 | 144 | 16.8 | |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | 3 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.7 | |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 117 | 13.7 | 109 | 12.7 | |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 253 | 29.7 | 254 | 29.6 | |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 152 | 17.8 | 127 | 14.8 | |

| Other leukaemias of specified cell type | 15 | 1.8 | 4 | 0.5 | |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | 4 | 0.5 | 13 | 1.5 | |

| Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Age intervals | |||||||

| 0-18 | 18-64 | 65 and over | p* | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| LUC % Data | |||||||

| LUC % <4.5 | 205 | 86.1 | 766 | 89.7 | 488 | 79.0 | p<0.001 |

| LUC % ≥4.5 | 33 | 13.9 | 88 | 10.3 | 130 | 21.0 | |

| Preliminary Diagnosis | |||||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 24 | 10.1 | 151 | 17.7 | 26 | 4.2 | p<0.001 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 4 | 1.7 | 21 | 2.5 | 21 | 3.4 | |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | 13 | 5.5 | 56 | 6.6 | 47 | 7.6 | |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | 1 | 0.4 | 24 | 2.8 | 11 | 1.8 | |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 10 | 4.2 | 128 | 15.0 | 113 | 18.3 | |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.8 | |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 0 | 0 | 84 | 9.8 | 142 | 23.0 | |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 175 | 73.5 | 200 | 23.4 | 132 | 21.4 | |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 7 | 2.9 | 175 | 20.5 | 97 | 15.7 | |

| Other leukaemias of specified cell type | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.7 | 13 | 2.1 | |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | 3 | 1.3 | 5 | 0.6 | 9 | 1.5 | |

| Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

| LUC % Data | |||||

| LUC % <4.5 | LUC % ≥4.5 | p* | |||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Preliminary Diagnosis | |||||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 198 | 13.6 | 3 | 1.2 | p<0.001 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 45 | 3.1 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | 105 | 7.2 | 11 | 4.4 | |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | 36 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 230 | 15.8 | 21 | 8.4 | |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | 9 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 210 | 14.4 | 16 | 6.4 | |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 366 | 25.1 | 141 | 56.2 | |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 241 | 16.5 | 38 | 15.1 | |

| Other leukaemias of specified cell type | 10 | 0.7 | 9 | 3.6 | |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | 7 | 0.5 | 10 | 4.0 | |

| Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Preliminary Diagnosis | LUC % | |

|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 2 | [1.5-2.5] |

| Follicular lymphoma | 2.1 | [1.3-2.6] |

| Non-follicular lymphoma | 2.2 | [1.7-2.9] |

| Mature T/NK-cell lymphomas | 1.7 | [1.4-2.1] |

| Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.9 | [1.5-2.6] |

| Malignant immunoproliferative diseases | 2.1 | [1.9-2.75] |

| Multiple myeloma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms | 2.2 | [1.6-3.1] |

| Lymphoid leukaemia | 2.7 | [1.8-5] |

| Myeloid leukaemia | 1.9 | [1.5-2.8] |

| Other leukaemias of specified cell type | 4.3 | [2.6-6.4] |

| Leukaemia of unspecified cell type | 7.5 | [2.2-16.7] |

| Other and unspecified malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue | 2.6 | [2.3- ] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).