Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. DNA and RNA Isolation

2.3. Whole Exome Sequencing

2.4. Whole-Exome Sequencing Data Analysis

2.5. Variants Validation

3. Results

3.1. Hematological Parameters

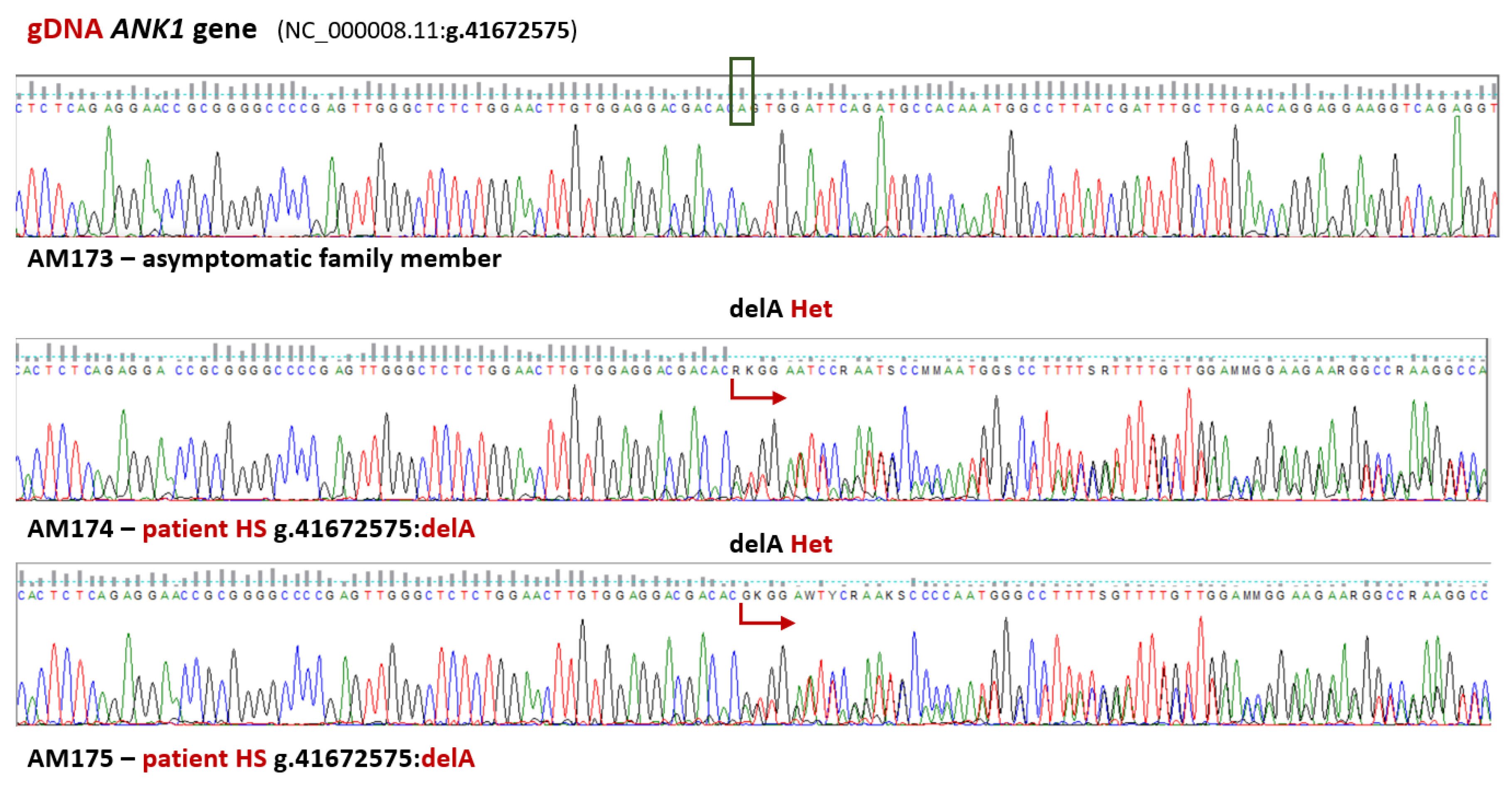

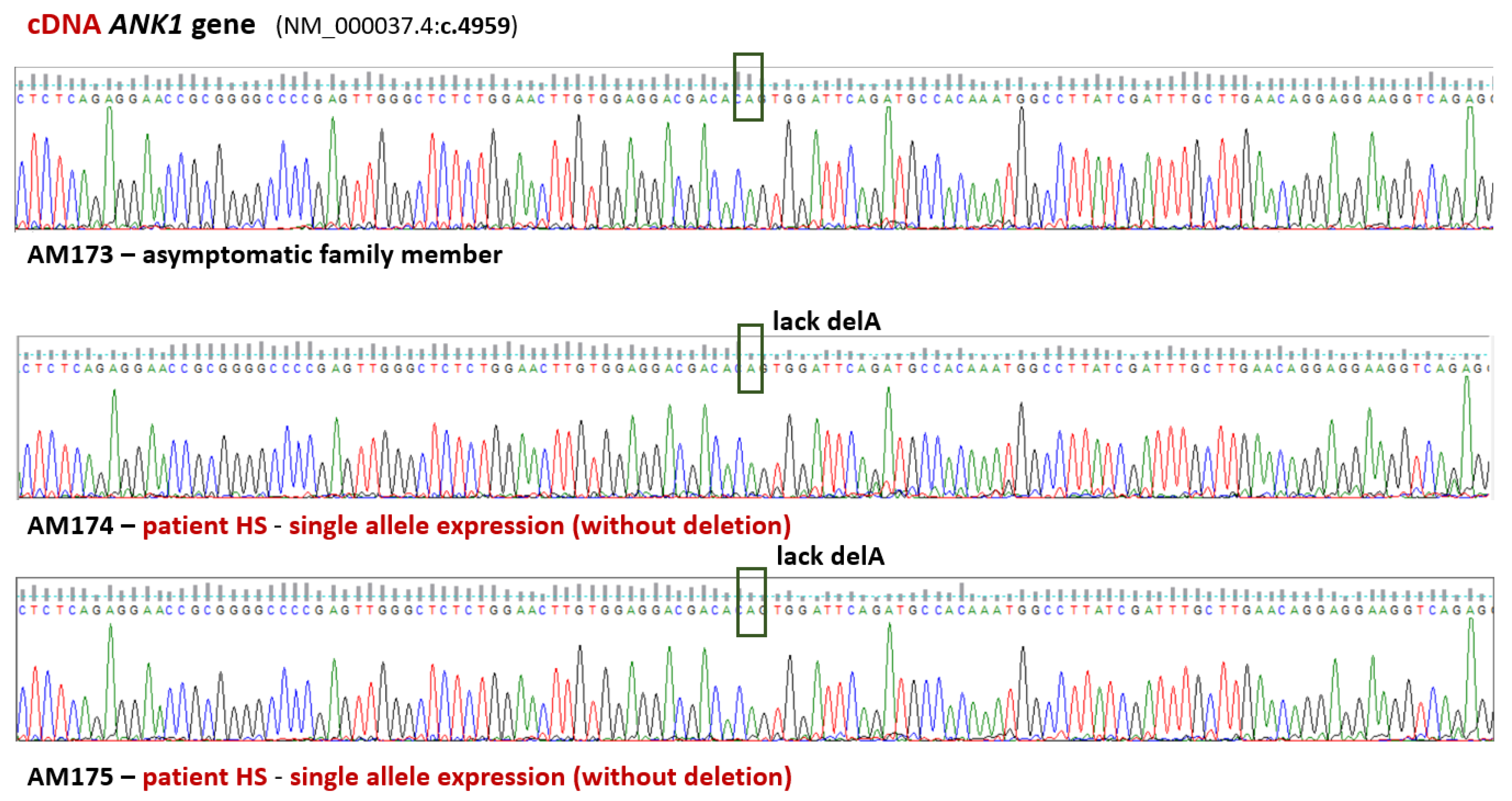

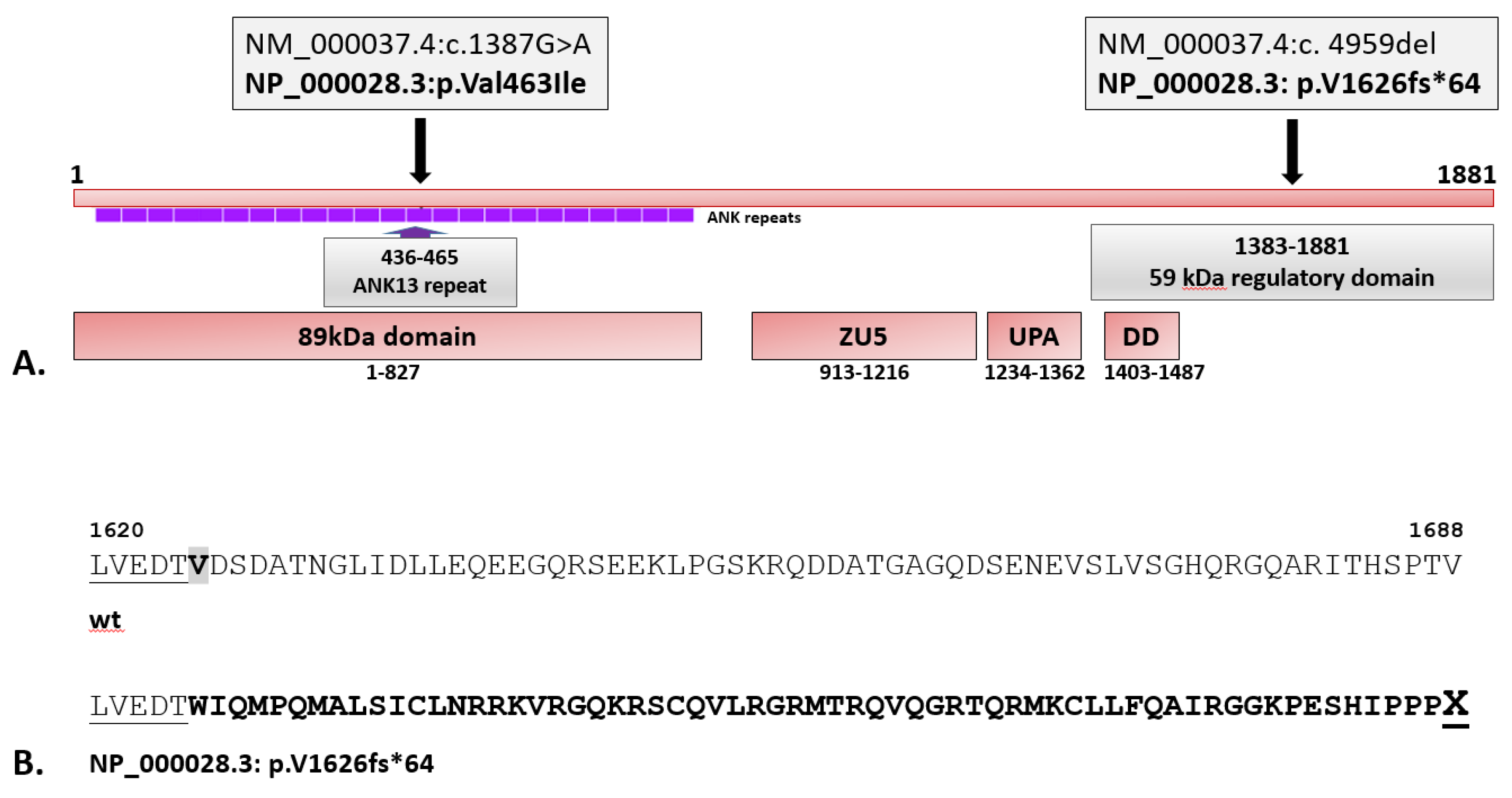

3.2. Validation of WES Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perrotta, S.; Gallagher, P.G.; Mohandas, N. Hereditary Spherocytosis. Lancet 2008, 372, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eber, S.; Lux, S.E. Hereditary Spherocytosis—Defects in Proteins That Connect the Membrane Skeleton to the Lipid Bilayer. Semin Hematol 2004, 41, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciepiela, O. Old and New Insights into the Diagnosis of Hereditary Spherocytosis. 2018, i, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, A.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R. Advances in Understanding the Pathogenesis of Red Cell Membrane Disorders. Br J Haematol 2019, 187, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisjes, R.; Makhro, A.; Llaudet-Planas, E.; Hertz, L.; Petkova-Kirova, P.; Verhagen, L.P.; Pignatelli, S.; Rab, M.A.E.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Seiler, E.; et al. Density, Heterogeneity and Deformability of Red Cells as Markers of Clinical Severity in Hereditary Spherocytosis. Haematologica 2020, 105, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton-Maggs, P.H.B.; Langer, J.C.; Iolascon, A.; Tittensor, P.; King, M.J. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Hereditary Spherocytosis - 2011 Update. Br J Haematol 2012, 156, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liao, L.; Lin, F. The Diagnostic Protocol for Hereditary Spherocytosis-2021 Update. J Clin Lab Anal 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Huang, H.; Luo, K.; Yi, Y.; Shi, X. Two Different Pathogenic Gene Mutations Coexisted in the Same Hereditary Spherocytosis Family Manifested with Heterogeneous Phenotypes. BMC Med Genet 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, D.; Liang, X.; Xie, H.; Wei, X.; Shang, X. Precise Diagnosis of a Hereditary Spherocytosis Patient with Complicated Hematological Phenotype. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2024, 299, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, F.; Rossmann, H.; Adenaeuer, A.; Shrestha, A.; Marandiuc, D.; Paret, C.; Faber, J.; Lackner, K.J.; Lämmle, B.; Beck, O. Hereditary Spherocytosis: Can Next-Generation Sequencing of the Five Most Frequently Affected Genes Replace Time-Consuming Functional Investigations? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Shu, H.; Zhou, M.; Gong, Y. Literature Review on Genotype–Phenotype Correlation in Patients with Hereditary Spherocytosis. Clin Genet 2022, 102, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risinger, M.; Kalfa, T.A. Red Cell Membrane Disorders: Structure Meets Function. Blood 2020, 136, 1250–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, L.; Sabatino, D.E.; Wong, E.Y.; Cline, A.P.; Garrett, L.J.; Garbarz, M.; Dhermy, D.; Bodine, D.M.; Gallagher, P.G. Erythroid Expression of the Human α-Spectrin Gene Promoter Is Mediated by GATA-1- and NF-E2-Binding Proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 41563–41570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, S.; Kajii, E.; Omi, T.; Kamesaki, T.; Akifuji, Y.; Ikemoto, S. Point Mutation in the Band 4.2 Gene Associated with Autosomal Recessively Inherited Erythrocyte Band 4.2 Deficiency. Eur J Haematol 1993, 50, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, L.L.; Jindel, H.K.; Gwynn, B.; Korsgren, C.; John, K.M.; Lux, S.E.; Mohandas, N.; Cohen, C.M.; Cho, M.R.; Golan, D.E.; et al. Mild Spherocytosis and Altered Red Cell Ion Transport in Protein 4.2–Null Mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1999, 103, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.L.; Sang, B.H.; Lei, Q.L.; Song, C.Y.; Lin, Y.B.; Lv, Y.; Yang, C.H.; Li, N.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhang, X.W.; et al. A de Novo ANK1 Mutation Associated to Hereditary Spherocytosis: A Case Report. BMC Pediatr 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Xie, Y.; Wu, P.; Li, S.; Hua, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhao, W. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Identified a Novel ANK1 Mutation Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis in a Chinese Family. Hematology (United Kingdom) 2019, 24, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Xing, Z.; Li, C.; Liu, S. xi; Wen, F. qiu Identification of a De Novoc.1000delA ANK1 Mutation Associated to Hereditary Spherocytosis in a Neonate with Coombs-Negative Hemolytic Jaundice-Case Reports and Review of the Literature. BMC Med Genomics 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iolascon, a; Miraglia del Giudice, E. ; Perrotta, S.; Alloisio, N.; Morlé, L.; Delaunay, J. Hereditary Spherocytosis: From Clinical to Molecular Defects. Haematologica 1998, 83, 240–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, P.G.; Romana, M.; Tse, W.T.; Lux, S.E.; Forget, B.G. The Human Ankyrin-1 Gene Is Selectively Transcribed in Erythroid Cell Lines despite the Presence of a Housekeeping-like Promoter. Blood 2000, 96, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, D.E.; Wong, C.; Cline, A.P.; Pyle, L.; Garrett, L.J.; Gallagher, P.G.; Bodine, D.M. A Minimal Ankyrin Promoter Linked to a Human γ-Globin Gene Demonstrates Erythroid Specific Copy Number Dependent Expression with Minimal Position or Enhancer Dependence in Transgenic Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2000, 275, 28549–28554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, V.; Stenbuck, P.J. The Membrane Attachment Protein for Spectrin Is Associated with Band 3 in Human Erythrocyte Membranes. Nature 1979, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Bham, K.; Senapati, S. Human Ankyrins and Their Contribution to Disease Biology: An Update. J Biosci 2020, 45, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S.R.; Rasband, M.N. Pleiotropic Ankyrins: Scaffolds for Ion Channels and Transporters. Channels 2022, 16, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanspal, M.; Yoon, S.; Yu, H.; Hanspal, J.; Lambert, S.; Palek, J.; Prchal, J. Molecular Basis of Spectrin and Ankyrin Deficiencies in Severe Hereditary Spherocytosis: Evidence Implicating a Primary Defect of Ankyrin. Blood 1991, 77, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, R.; Andolfo, I.; Manna, F.; Gambale, A.; Marra, R.; Rosato, B.E.; Caforio, P.; Pinto, V.; Pignataro, P.; Radhakrishnan, K.; et al. Multi-Gene Panel Testing Improves Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Hereditary Anemias. Am J Hematol 2018, 93, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Ahn, W.K.; Lee, S.T.; Han, J.W.; Choi, J.R.; Lyu, C.J.; Hahn, S.; Shin, S. Diagnostic Yield of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing for Pediatric Hereditary Hemolytic Anemia. BMC Med Genomics 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, M. Diagnostic Approaches for Inherited Hemolytic Anemia in the Genetic Era. Blood Res 2017, 52, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eber, S.W.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Lux, M.L.; Scarpa, A.L.; Tse, W.T.; Dornwell, M.; Herbers, J.; Kugler, W.; Ozcan, R.; Pekrun, A.; et al. Ankyrin–1 Mutations Are a Major Cause of Dominant and Recessive Hereditary Spherocytosis. Nat Genet 1996, 13, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogusławska, D.M.; Skulski, M.; Machnicka, B.; Potoczek, S.; Kraszewski, S.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Sikorski, A.F. Identification of a Novel Mutation of β-Spectrin in Hereditary Spherocytosis Using Whole Exome Sequencing. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogusławska, D.M.; Heger, E.; Machnicka, B.; Skulski, M.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Sikorski, A.F. A New Frameshift Mutation of the β-Spectrin Gene Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis. Ann Hematol 2017, 96, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boguslawska, D.M.; Heger, E.; Listowski, M.; Wasiński, D.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Machnicka, B.; Sikorski, A.F. A Novel L1340P Mutation in the ANK1 Gene Is Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis? Br J Haematol 2014, 167, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusławska, D.M.; Skulski, M.; Bartoszewski, R.; Machnicka, B.; Heger, E.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Sikorski, A.F. A Rare Mutation (p.F149del) of the NT5C3A Gene Is Associated with Pyrimidine 5′-Nucleotidase Deficiency. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2022, 27, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogusławska, D.M.; Kraszewski, S.; Skulski, M.; Potoczek, S.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Sikorski, A.F. Novel Variant of the SLC4A1 Gene Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machnicka, B.; Czogalla, A.; Bogusławska, D.M.; Stasiak, P.; Sikorski, A.F. Spherocytosis-Related L1340P Mutation in Ankyrin Affects Its Interactions with Spectrin. Life 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meienberg, J.; Bruggmann, R.; Oexle, K. ; Matyas, · Gabor Clinical Sequencing: Is WGS the Better WES? Hum Genet 2016, 135, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, E.J.; Maksimova, Y.; Duru, F.; Altay, C.; Gallagher, P.G. A Complex Splicing Defect Associated with Homozygous Ankyrin-Deficient Hereditary Spherocytosis. Blood 2007, 109, 5491–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaunay, J. The Molecular Basis of Hereditary Red Cell Membrane Disorders. Blood Rev 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Francese, M.; Polito, R.; Nobili, B.; Iolascon, A.; Perrotta, S. Apparently Normal Ankyrin Content in Unsplenectomized Hereditary Spherocytosis Patients with the Inactivation of One Ankyrin (ANK1) Allele. Haematologica 1997, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Bogusławska, D.M.; Heger, E.; Machnicka, B.; Skulski, M.; Kuliczkowski, K.; Sikorski, A.F. A New Frameshift Mutation of the β-Spectrin Gene Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis. Ann Hematol 2017, 96, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassères, D.S.; Tavares, A.C.; Costa, F.F.; Saad, S.T.O. SS-Spectrin São PauloII, a Novel Frameshift Mutation of the ß-Spectrin Gene Associated with Hereditary Spherocytosis and Instability of the Mutant MRNA. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2002, 35, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Lombardi, C.; Francesie, M.; Nobili, B.; Conte, M.L.; Amendola, G.; Cutillo, S.; Iolascon, A.; Perrotta, S. Frequent de Novo Monoallelic Expression of β-Spectrin Gene (SPTB) in Children with Hereditary Spherocytosis and Isolated Spectrin Deficiency. Br J Haematol 1998, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarolim, P.; Rubin, H.L.; Brabec, V.; Palek, J. Comparison of the Ankyrin (AC)n Microsatellites in Genomic DNA and MRNA Reveals Absence of One Ankyrin MRNA Allele in 20% of Patients with Hereditary Spherocytosis. Blood 1995, 85, 3278–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarolim, P.; Murray, J.L.; Rubin, H.L.; Taylor, W.M.; Prchal, J.T.; Ballas, S.K.; Snyder, L.M.; Chrobak, L.; Melrose, W.D.; Brabec, V.; et al. Characterization of 13 Novel Band 3 Gene Defects in Hereditary Spherocytosis with Band 3 Deficiency. Blood 1996, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhermy, D.; Bournier, O.; Bourgeois, M.; Grandchamp, B. The Red Blood Cell Band 3 Variant (Band 3(Bicetrel):R490C) Associated with Dominant Hereditary Spherocytosis Causes Defective Membrane Targeting of the Molecule and a Dominant Negative Effect. Mol Membr Biol 1999, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laboratory tests | Units | HS patients |

Reference range (female) |

Reference range (male) |

|

| AM174 (female) | AM175 (male) | ||||

| WBC | (G/L) | 11.37±3.02 | 11.80±2.05 | 4-10 | 4-10 |

| RBC | (T/L) | 3.58±0.35 | 3.58±0.35 | 4.0-5.0 | 4.5-5.9 |

| Hb | (mmol/L) | 7.21±0.50 | 7.65±0.52 | 7.54-9.93 | 8.69 -11.17 |

| HCT | (L/L) | 0.32±0.02 | 0.34±0.02 | 0.37-0.47 | 0.37-0.53 |

| PLT | (G/L) | 321±20 | 222±19 | 140-440 | 140-440 |

| MCV | (fL) | 88±2 | 95±3 | 81-98 | 81-98 |

| MCH | (fmol) | 2.02±0.06 | 2.17±0.13 | 1.61-2.11 | 1.61-2.11 |

| MCHC | (mmol/L) | 22.88±0.11 | 21.16±2.14 | 19.24-22.96 | 19.24-22.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).