Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The TRP Channel Family

3. TRP Ion Channels in the Pathogenesis of CIBP

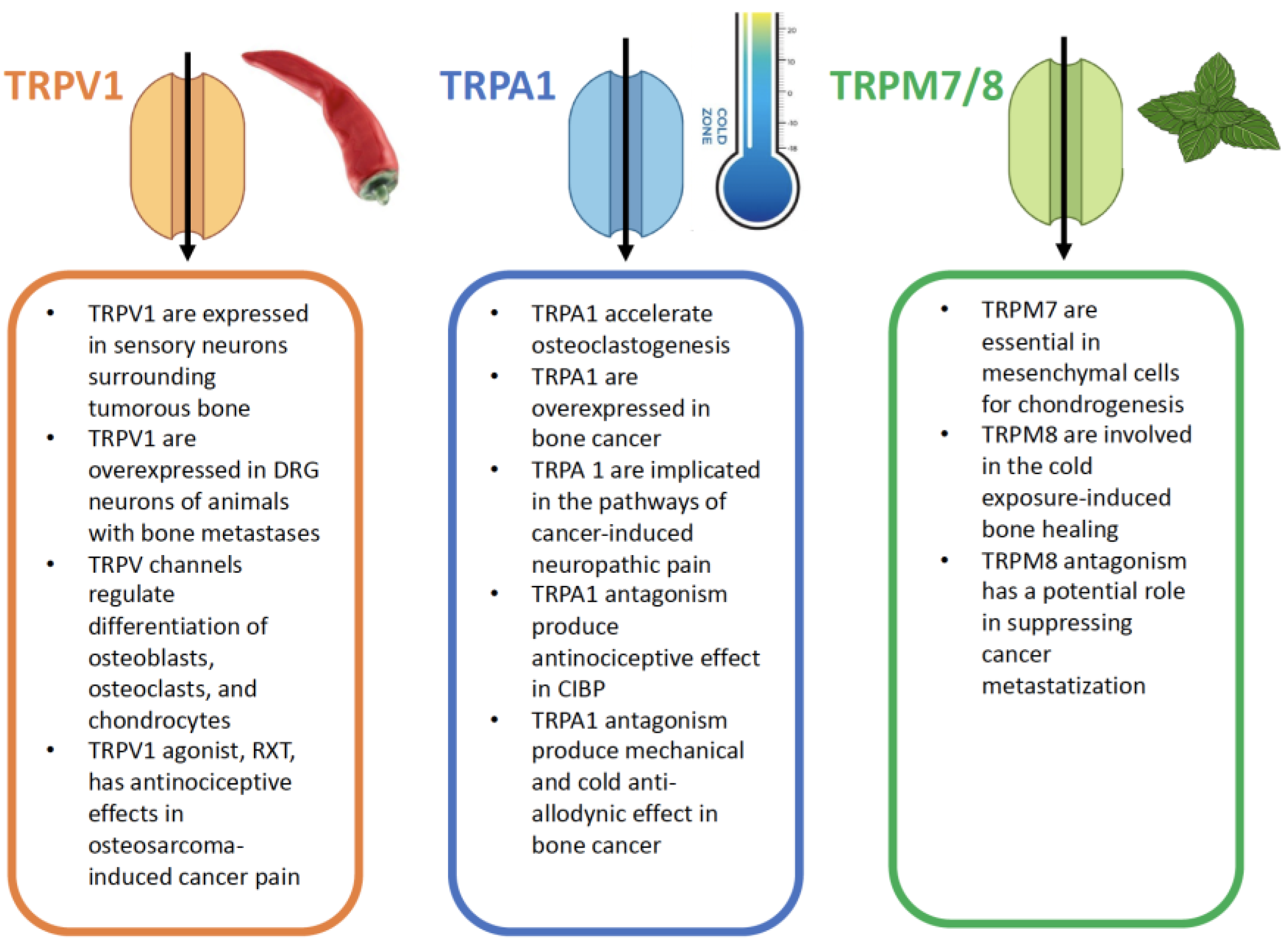

4. TRPV Channels

4.1. TRPV Modulation in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain

4.1.1. Resiniferatoxin (RTX)

4.1.2. JNJ-17203212

4.1.3. SB366791 [N-(3-methoxyphenyl)-4-chlorocinnamide]

4.1.4. 5-iodoresiniferatoxin

4.1.5. ABT-102

4.1.6. Capsazepine (CPZ)

4.1.7. QX-314

4.1.8. Quercetin

4.1.9. Acetaminophen

4.1.10. Xiaozheng Zhitong Paste (XZP)

4.1.11. PD-L1/ SHP-1

4.1.12. Quetiapine

4.1.13. Arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide

5. TRPA Channels

5.1. TRPA1 Modulation in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain

6. TRPM Channels

6.1. TRPM Modulation in Cancer-Induced Bone Pain

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-AG | 2-arachidonylglycerol |

| 5-HT | Serotonin |

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| AAV | Adeno-associated virus |

| AGS | Gastric adenocarcinoma |

| AITC | Allyl isothiocyanate |

| AM404 | N-arachidonoylphenolamine |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BK | Bradykinin |

| BMC | Bone mineral content |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| Ca2+ | Calcium |

| CaMKII | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CGRP | Calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| CIBP | Cancer-induced bone pain |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CPZ | Capsazepine |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| CXCL1 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 |

| CXCR2 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 |

| DAG | Diacylglycerol |

| DRG | Dorsal root ganglion |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| G-CSF | Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 |

| IB4 | Isolectin B4 |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-17A | Interleukin-17A |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IP3 | Inositol triphosphate |

| I-RTX | 5-iodoresiniferatoxin |

| ITGA4 | Integrin Subunit Alpha 4 |

| ITGB7 | Integrin Subunit Beta 7 |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| KD | KiloDalton |

| KIF13B | Kinesin-13B |

| KO | Knockout |

| MAPK/ERK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal regulated kinase |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| MOR | Mu-opioid receptor |

| MRMT-1 | Mammary rat metastasis tumor |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen |

| NAPQI | N-acetyl-4-benzoquinoneimine |

| NF200 | Neurofilament 200 kD |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs |

| NSCLC | Non-small lung cancer |

| OIC | Opioid-induced constipation |

| OIH | Opioid-induced hyperalgesia |

| PAG | Periaqueductal gray |

| PAR2 | Protease-activated receptor-2 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand 1 |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PGs | Prostaglandins |

| PI3K/PKB | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PLCP | Phospholipase |

| PMs | Plasma membranes |

| PPP | Picropodophyllotoxin |

| PTHrP | Parathyroid hormone-related peptide |

| RANK | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κ B |

| RANKL | Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κ B ligand |

| RTX | Resiniferatoxin |

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| SHP-1 | Src homology 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase-1 |

| siRNA | Short-interfering RNA |

| SREs | Skeletal-related events |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor-β1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TPPO | Triphenylphosphine oxide |

| TrkA | Tyrosine receptor kinases A |

| TRP | Transient Receptor Potential |

| TRPA | Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin |

| TRPC | Transient Receptor Potential canonical |

| TRPM | Transient Receptor Potential melastatins |

| TRPML | Transient Receptor Potential mucolipins |

| TRPN | Transient Receptor Potential no mechanoreceptor potential C channels |

| TRPP | Transient Receptor Potential polycystins |

| TRPV | Transient Receptor Potential vanilloids |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VTA | Ventral tegmental area |

| XZP | Xiaozheng Zhitong Paste |

References

- World Cancer Research Fund, Global cancer data by country. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/global-cancer-data-by-country. (Last accessed on 30th December 2024).

- Knapp BJ, Cittolin-Santos GF, Flanagan ME, Grandhi N, Gao F, Samson PP, Govindan R, Morgensztern D. Incidence and risk factors for bone metastases at presentation in solid tumors. Front Oncol. 2024 May 10;14:1392667. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ryan C, Stoltzfus KC, Horn S, Chen H, Louie AV, Lehrer EJ, Trifiletti DM, Fox EJ, Abraham JA, Zaorsky NG. Epidemiology of bone metastases. Bone. 2022 May;158:115783. Epub 2020 Dec 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang JF, Shen J, Li X, Rengan R, Silvestris N, Wang M, Derosa L, Zheng X, Belli A, Zhang XL, Li YM, Wu A. Incidence of patients with bone metastases at diagnosis of solid tumors in adults: a large population-based study. Ann Transl Med. 2020 Apr;8(7):482. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang J, Cai D, Hong S. Prevalence and prognosis of bone metastases in common solid cancers at initial diagnosis: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2023 Oct 21;13(10):e069908. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Rolke R, Mercadante S. Pain Management in Patients with Multiple Myeloma: An Update. Cancers (Basel). 2019 Dec 17;11(12):2037. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alvaro D, Coluzzi F, Gianni W, Lugoboni F, Marinangeli F, Massazza G, Pinto C, Varrassi G. Opioid-Induced Constipation in Real-World Practice: A Physician Survey, 1 Year Later. Pain Ther. 2022 Jun;11(2):477-491. Epub 2022 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Scerpa MS, Loffredo C, Borro M, Pergolizzi JV, LeQuang JA, Alessandri E, Simmaco M, Rocco M. Opioid Use and Gut Dysbiosis in Cancer Pain Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jul 22;25(14):7999. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Santoni A. Opioid-Induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia. CNS Drugs. 2019 Oct;33(10):943-955. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rullo L, Morosini C, Lacorte A, Cristani M, Coluzzi F, Candeletti S, Romualdi P. Opioid system and related ligands: from the past to future perspectives. J Anesth Analg Crit Care. 2024 Oct 11;4(1):70. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Billeci D, Maggi M, Corona G. Testosterone deficiency in non-cancer opioid-treated patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Dec;41(12):1377-1388. Epub 2018 Oct 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, LeQuang JAK, Sciacchitano S, Scerpa MS, Rocco M, Pergolizzi J. A Closer Look at Opioid-Induced Adrenal Insufficiency: A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 26;24(5):4575. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Pergolizzi J, Raffa RB, Mattia C. The unsolved case of "bone-impairing analgesics": the endocrine effects of opioids on bone metabolism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2015 Mar 31;11:515-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Scerpa MS, Centanni M. The Effect of Opiates on Bone Formation and Bone Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020 Jun;18(3):325-335. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kress HG, Coluzzi F. Tapentadol in the management of cancer pain: current evidence and future perspectives. J Pain Res. 2019 May 16;12:1553-1560. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Rullo L, Scerpa MS, Losapio LM, Rocco M, Billeci D, Candeletti S, Romualdi P. Current and Future Therapeutic Options in Pain Management: Multi-mechanistic Opioids Involving Both MOR and NOP Receptor Activation. CNS Drugs. 2022 Jun;36(6):617-632. Epub 2022 May 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coluzzi F, Di Bussolo E, Mandatori I, Mattia C. Bone metastatic disease: taking aim at new therapeutic targets. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(20):3093-115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu HJ, Wu XB, Wei QQ. Ion channels in cancer-induced bone pain: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023 Aug 17;16:1239599. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stucky CL, Dubin AE, Jeske NA, Malin SA, McKemy DD, Story GM. Roles of transient receptor potential channels in pain. Brain Res Rev. 2009 Apr;60(1):2-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang M, Ma Y, Ye X, Zhang N, Pan L, Wang B. TRP (transient receptor potential) ion channel family: structures, biological functions and therapeutic interventions for diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Jul 5;8(1):261. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Almeida AS, Bernardes LB, Trevisan G. TRP channels in cancer pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021 Aug 5;904:174185. Epub 2021 May 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duitama M, Moreno Y, Santander SP, Casas Z, Sutachan JJ, Torres YP, Albarracín SL. TRP Channels as Molecular Targets to Relieve Cancer Pain. Biomolecules. 2021 Dec 21;12(1):1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu H, Blair NT, Clapham DE. Camphor activates and strongly desensitizes the transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 channel in a vanilloid-independent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2005 Sep 28;25(39):8924-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ishikawa DT, Vizin RCL, Souza CO, Carrettiero DC, Romanovsky AA, Almeida MC. Camphor, Applied Epidermally to the Back, Causes Snout- and Chest-Grooming in Rats: A Response Mediated by Cutaneous TRP Channels. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2019 Feb 2;12(1):24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alpizar YA, Gees M, Sanchez A, Apetrei A, Voets T, Nilius B, Talavera K. Bimodal effects of cinnamaldehyde and camphor on mouse TRPA1. Pflugers Arch. 2013 Jun;465(6):853-64. Epub 2012 Dec 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selescu T, Ciobanu AC, Dobre C, Reid G, Babes A. Camphor activates and sensitizes transient receptor potential melastatin 8 (TRPM8) to cooling and icilin. Chem Senses. 2013 Sep;38(7):563-75. Epub 2013 Jul 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias B, Merighi A. Capsaicin, Nociception and Pain. Molecules. 2016 Jun 18;21(6):797. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bernal-Cepeda LJ, Velandia-Romero ML, Castellanos JE. Capsazepine antagonizes TRPV1 activation induced by thermal and osmotic stimuli in human odontoblast-like cells. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2023 Jan-Feb;13(1):71-77. Epub 2022 Nov 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li WW, Zhao Y, Liu HC, Liu J, Chan SO, Zhong YF, Zhang TY, Liu Y, Zhang W, Xia YQ, Chi XC, Xu J, Wang Y, Wang J. Roles of Thermosensitive Transient Receptor Channels TRPV1 and TRPM8 in Paclitaxel-Induced Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 May 27;25(11):5813. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xing H, Chen M, Ling J, Tan W, Gu JG. TRPM8 mechanism of cold allodynia after chronic nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2007 Dec 12;27(50):13680-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim YS, Hong CS, Lee SW, Nam JH, Kim BJ. Effects of ginger and its pungent constituents on transient receptor potential channels. Int J Mol Med. 2016 Dec;38(6):1905-1914. Epub 2016 Oct 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya Y, Kawamata K. Allicin Induces Electrogenic Secretion of Chloride and Bicarbonate Ions in Rat Colon via the TRPA1 Receptor. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2019;65(3):258-263. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Petrocellis L, Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Allarà M, Bisogno T, Petrosino S, Stott CG, Di Marzo V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 Aug;163(7):1479-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tominaga M, Kashio M. Thermosensation and TRP Channels. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024;1461:3-13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu S, Takahashi N, Mori Y. TRPs as chemosensors (ROS, RNS, RCS, gasotransmitters). Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;223:767-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Liang J, Liu P, Wang Q, Liu L, Zhao H. The RANK/RANKL/OPG system and tumor bone metastasis: Potential mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Dec 16;13:1063815. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jing D, Zhao Q, Zhao Y, Lu X, Feng Y, Zhao B, Zhao X. Management of pain in patients with bone metastases. Front Oncol. 2023 Mar 16;13:1156618. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wakabayashi H, Wakisaka S, Hiraga T, Hata K, Nishimura R, Tominaga M, Yoneda T. Decreased sensory nerve excitation and bone pain associated with mouse Lewis lung cancer in TRPV1-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Metab. 2018 May;36(3):274-285. Epub 2017 May 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen W, Li H, Hao X, Liu C. TRPV1 in dorsal root ganglion contributed to bone cancer pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2022 Nov 9;3:1022022. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oostinga D, Steverink JG, van Wijck AJM, Verlaan JJ. An understanding of bone pain: A narrative review. Bone. 2020 May;134:115272. Epub 2020 Feb 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneda T, Hiasa M, Okui T, Hata K. Cancer-nerve interplay in cancer progression and cancer-induced bone pain. J Bone Miner Metab. 2023 May;41(3):415-427. Epub 2023 Jan 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao D, Han DF, Wang SS, Lv B, Wang X, Ma C. Roles of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 in regulating bone cancer pain via TRPA1 signal pathway and beneficial effects of inhibition of neuro-inflammation and TRPA1. Mol Pain. 2019 Jan-Dec;15:1744806919857981. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holzer P. Acid-sensitive ion channels and receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(194):283-332. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hiasa M, Okui T, Allette YM, Ripsch MS, Sun-Wada GH, Wakabayashi H, Roodman GD, White FA, Yoneda T. Bone Pain Induced by Multiple Myeloma Is Reduced by Targeting V-ATPase and ASIC3. Cancer Res. 2017 Mar 15;77(6):1283-1295. Epub 2017 Mar 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansen RB, Sayilekshmy M, Sørensen MS, Jørgensen AH, Kanneworff IB, Bengtsson EKE, Grum-Schwensen TA, Petersen MM, Ejersted C, Andersen TL, Andreasen CM, Heegaard AM. Neuronal Sprouting and Reorganization in Bone Tissue Infiltrated by Human Breast Cancer Cells. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2022 May 31;3:887747. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng Q, Fang D, Cai J, Wan Y, Han JS, Xing GG. Enhanced excitability of small dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats with bone cancer pain. Mol Pain. 2012 Apr 3;8:24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Xu L. Targeted therapy: P2X3 receptor silencing in bone cancer pain relief. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2024 Nov;38(11):e70026. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu P, Wu X, Zhou G, Wang Y, Liu X, Lv R, Liu Y, Wen Q. P2X7 Receptor-Induced Bone Cancer Pain by Regulating Microglial Activity via NLRP3/IL-1beta Signaling. Pain Physician. 2022 Nov;25(8):E1199-E1210. [PubMed]

- Yanagisawa Y, Furue H, Kawamata T, Uta D, Yamamoto J, Furuse S, Katafuchi T, Imoto K, Iwamoto Y, Yoshimura M. Bone cancer induces a unique central sensitization through synaptic changes in a wide area of the spinal cord. Mol Pain. 2010 Jul 5;6:38. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ge MM, Chen SP, Zhou YQ, Li Z, Tian XB, Gao F, Manyande A, Tian YK, Yang H. The therapeutic potential of GABA in neuron-glia interactions of cancer-induced bone pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019 Sep 5;858:172475. Epub 2019 Jun 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka T, Yamada T, Ishimura T, Zuo D, Moffett JR, Neale JH, Yamamoto T. A role for the locus coeruleus in the analgesic efficacy of N-acetylaspartylglutamate peptidase (GCPII) inhibitors ZJ43 and 2-PMPA. Mol Pain. 2017 Jan;13:1744806917697008. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Slosky LM, BassiriRad NM, Symons AM, Thompson M, Doyle T, Forte BL, Staatz WD, Bui L, Neumann WL, Mantyh PW, Salvemini D, Largent-Milnes TM, Vanderah TW. The cystine/glutamate antiporter system xc- drives breast tumor cell glutamate release and cancer-induced bone pain. Pain. 2016 Nov;157(11):2605-2616. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, D., Zhou, X., Tan, Y., Yu, H., Cao, Y., Tian, L., Yang, L., Wang, S., Liu, S., Chen, J., Liu, J., Wang, C., Yu, H., Zhang, J., 2022. Altered brain functional activity and connectivity in bone metastasis pain of lung cancer patients: a preliminary restingstate fMRI study. Front. Neurol. 13, 936012. [CrossRef]

- Chiou, C., Chen, C., Tsai, T., Huang, C., Chou, D., Hsu, K., 2016. Alleviating bone cancerinduced mechanical hypersensitivity by inhibiting neuronal activity in the anterior cingulate cortex. Anesthesiology 125, 779–792. [CrossRef]

- Morales, M., Margolis, E.B., 2017. Ventral tegmental area: cellular heterogeneity, connectivity and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 73–85. [CrossRef]

- Imam MZ, Kuo A, Nicholson JR, Corradini L, Smith MT. Assessment of the anti-allodynic efficacy of a glycine transporter 2 inhibitor relative to pregabalin and duloxetine in a rat model of prostate cancer-induced bone pain. Pharmacol Rep. 2020 Oct;72(5):1418-1425. Epub 2020 Jul 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk S, Patel R, Heegaard A, Mercadante S, Dickenson AH. Spinal neuronal correlates of tapentadol analgesia in cancer pain: a back-translational approach. Eur J Pain. 2015 Feb;19(2):152-8. Epub 2014 Jun 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliepen SHJ, Korioth J, Christoph T, Tzschentke TM, Diaz-delCastillo M, Heegaard AM, Rutten K. The nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor system as a target to alleviate cancer-induced bone pain in rats: Model validation and pharmacological evaluation. Br J Pharmacol. 2021 May;178(9):1995-2007. Epub 2020 Jan 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gough P, Myles IA. Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors: Pleiotropic Signaling Complexes and Their Differential Effects. Front Immunol. 2020 Nov 25;11:585880. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lim H, Lee H, Noh K, Lee SJ. IKK/NF-κB-dependent satellite glia activation induces spinal cord microglia activation and neuropathic pain after nerve injury. Pain. 2017 Sep;158(9):1666-1677. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo W, Liu Y, Lei Y, Zhang Y, Huang Y, Mao Y, Wang C, Sun Y, Zhang W, Ma Z, Gu X. Imbalanced spinal infiltration of Th17/Treg cells contributes to bone cancer pain via promoting microglial activation. Brain Behav Immun. 2019 Jul;79:139-151. Epub 2019 Jan 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Sun Y, Tomura H, Okajima F. Ovarian cancer G-protein-coupled receptor 1 induces the expression of the pain mediator prostaglandin E2 in response to an acidic extracellular environment in human osteoblast-like cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012 Nov;44(11):1937-41. Epub 2012 Jul 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol LSC, Thornton P, Hatcher JP, Glover CP, Webster CI, Burrell M, Hammett K, Jones CA, Sleeman MA, Billinton A, Chessell I. Central inhibition of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is analgesic in experimental neuropathic pain. Pain. 2018 Mar;159(3):550-559. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ni H, Xu M, Xie K, Fei Y, Deng H, He Q, Wang T, Liu S, Zhu J, Xu L, Yao M. Liquiritin Alleviates Pain Through Inhibiting CXCL1/CXCR2 Signaling Pathway in Bone Cancer Pain Rat. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Apr 24;11:436. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schumacher MA. Peripheral Neuroinflammation and Pain: How Acute Pain Becomes Chronic. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(1):6-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lozano-Ondoua AN, Symons-Liguori AM, Vanderah TW. Cancer-induced bone pain: Mechanisms and models. Neurosci Lett. 2013 Dec 17;557 Pt A(0 0):52-9. Epub 2013 Sep 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fallon M, Sopata M, Dragon E, Brown MT, Viktrup L, West CR, Bao W, Agyemang A. A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Anti-Nerve Growth Factor Antibody Tanezumab in Subjects With Cancer Pain Due to Bone Metastasis. Oncologist. 2023 Dec 11;28(12):e1268-e1278. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Niemeyer BA. Structure-function analysis of TRPV channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005 Apr;371(4):285-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haustrate A, Prevarskaya N, Lehen'kyi V. Role of the TRPV Channels in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium Homeostasis. Cells. 2020 Jan 28;9(2):317. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stratiievska A, Nelson S, Senning EN, Lautz JD, Smith SE, Gordon SE. Reciprocal regulation among TRPV1 channels and phosphoinositide 3-kinase in response to nerve growth factor. Elife. 2018 Dec 18;7:e38869. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang Q, Ji C, Ali A, Ding I, Wang Y, McCulloch CA. TRPV4 mediates IL-1-induced Ca2+ signaling, ERK activation and MMP expression. FASEB J. 2024 Jun 15;38(11):e23731. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su X, Shen Z, Yang Q, Sui F, Pu J, Ma J, Ma S, Yao D, Ji M, Hou P. Vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells through ROS-dependent inhibition of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways via distinct mechanisms. Theranostics. 2019 Jun 9;9(15):4461-4473. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ren X, Feng C, Wang Y, Chen P, Wang S, Wang J, Cao H, Li Y, Ji M, Hou P. SLC39A10 promotes malignant phenotypes of gastric cancer cells by activating the CK2-mediated MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways. Exp Mol Med. 2023 Aug;55(8):1757-1769. Epub 2023 Aug 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loureiro G, Bahia DM, Lee MLM, de Souza MP, Kimura EYS, Rezende DC, Silva MCA, Chauffaille MLLF, Yamamoto M. MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways are activated in adolescent and adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2023 Dec;6(12):e1912. Epub 2023 Oct 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bourinet E, Altier C, Hildebrand ME, Trang T, Salter MW, Zamponi GW. Calcium-permeable ion channels in pain signaling. Physiol Rev. 2014 Jan;94(1):81-140. Erratum in: Physiol Rev. 2014 Jul;94(3):987. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shantanu PA, Sharma D, Sharma M, Vaidya S, Sharma K, Kalia K, Tao YX, Shard A, Tiwari V. Kinesins: Motor Proteins as Novel Target for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Mol Neurobiol. 2019 Jun;56(6):3854-3864. Epub 2018 Sep 13. Erratum in: Mol Neurobiol. 2021 Jan;58(1):450. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02117-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niiyama Y, Kawamata T, Yamamoto J, Omote K, Namiki A. Bone cancer increases transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily 1 expression within distinct subpopulations of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2007 Aug 24;148(2):560-72. Epub 2007 Jul 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards JG. TRPV1 in the central nervous system: synaptic plasticity, function, and pharmacological implications. Prog Drug Res. 2014;68:77-104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An SB, Cho YS, Park SK, Kim YS, Bae YC. Synaptic connectivity of the TRPV1-positive trigeminal afferents in the rat lateral parabrachial nucleus. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023 Mar 30;17:1162874. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bagood MD, Isseroff RR. TRPV1: Role in Skin and Skin Diseases and Potential Target for Improving Wound Healing. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 7;22(11):6135. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu Y, Zhao Y, Gao B. Role of TRPV1 in High Temperature-Induced Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle: A Mini Review. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Apr 5;10:882578. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Birder LA. TRPs in bladder diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 Aug;1772(8):879-84. Epub 2007 Apr 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Munjuluri S, Wilkerson DA, Sooch G, Chen X, White FA, Obukhov AG. Capsaicin and TRPV1 Channels in the Cardiovascular System: The Role of Inflammation. Cells. 2021 Dec 22;11(1):18. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qu Y, Fu Y, Liu Y, Liu C, Xu B, Zhang Q, Jiang P. The role of TRPV1 in RA pathogenesis: worthy of attention. Front Immunol. 2023 Sep 8;14:1232013. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He LH, Liu M, He Y, Xiao E, Zhao L, Zhang T, Yang HQ, Zhang Y. TRPV1 deletion impaired fracture healing and inhibited osteoclast and osteoblast differentiation. Sci Rep. 2017 Feb 22;7:42385. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoneda T, Hiasa M, Nagata Y, Okui T, White F. Contribution of acidic extracellular microenvironment of cancer-colonized bone to bone pain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 Oct;1848(10 Pt B):2677-84. Epub 2015 Feb 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dhaka A, Uzzell V, Dubin AE, Mathur J, Petrus M, Bandell M, Patapoutian A. TRPV1 is activated by both acidic and basic pH. J Neurosci. 2009 Jan 7;29(1):153-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Daniluk J, Voets T. pH-dependent modulation of TRPV1 by modality-selective antagonists. Br J Pharmacol. 2023 Nov;180(21):2750-2761. Epub 2023 Jul 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagae M, Hiraga T, Yoneda T. Acidic microenvironment created by osteoclasts causes bone pain associated with tumor colonization. J Bone Miner Metab. 2007;25(2):99-104. Epub 2007 Feb 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Stelt M, Di Marzo V. Endovanilloids. Putative endogenous ligands of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels. Eur J Biochem. 2004 May;271(10):1827-34. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyd DR, Weiss G, Henry MA, Hargreaves KM. Serotonin increases the functional activity of capsaicin-sensitive rat trigeminal nociceptors via peripheral serotonin receptors. Pain. 2011 Oct;152(10):2267-2276. Epub 2011 Jul 6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, Kim M, Kim M, Koo JY, Lee CH, Kim M, Oh U. TRPV1 mediates histamine-induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase. J Neurosci. 2007 Feb 28;27(9):2331-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tong Z, Luo W, Wang Y, Yang F, Han Y, Li H, Luo H, Duan B, Xu T, Maoying Q, Tan H, Wang J, Zhao H, Liu F, Wan Y. Tumor tissue-derived formaldehyde and acidic microenvironment synergistically induce bone cancer pain. PLoS One. 2010 Apr 21;5(4):e10234. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han Y, Li Y, Xiao X, Liu J, Meng XL, Liu FY, Xing GG, Wan Y. Formaldehyde up-regulates TRPV1 through MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Neurosci Bull. 2012 Apr;28(2):165-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan HL, Zhang YQ, Zhao ZQ. Involvement of lysophosphatidic acid in bone cancer pain by potentiation of TRPV1 via PKCε pathway in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Pain. 2010 Dec 1;6:85. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moriyama T, Higashi T, Togashi K, Iida T, Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Tominaga T, Narumiya S, Tominaga M. Sensitization of TRPV1 by EP1 and IP reveals peripheral nociceptive mechanism of prostaglandins. Mol Pain. 2005 Jan 17;1:3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mathivanan S, Devesa I, Changeux JP, Ferrer-Montiel A. Bradykinin Induces TRPV1 Exocytotic Recruitment in Peptidergic Nociceptors. Front Pharmacol. 2016 Jun 23;7:178. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shimizu T, Yanase N, Fujii T, Sakakibara H, Sakai H. Regulation of TRPV1 channel activities by intracellular ATP in the absence of capsaicin. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2022 Feb 1;1864(1):183782. Epub 2021 Sep 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantin CE, Mair N, Sailer CA, Andratsch M, Xu ZZ, Blumer MJ, Scherbakov N, Davis JB, Bluethmann H, Ji RR, Kress M. Endogenous tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) requires TNF receptor type 2 to generate heat hyperalgesia in a mouse cancer model. J Neurosci. 2008 May 7;28(19):5072-81. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang E, Lee S, Yi MH, Nan Y, Xu Y, Shin N, Ko Y, Lee YH, Lee W, Kim DW. Expression of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor in the spinal dorsal horn following spinal nerve ligation-induced neuropathic pain. Mol Med Rep. 2017 Aug;16(2):2009-2015. Epub 2017 Jun 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nakamura T, Okui T, Hasegawa K, Ryumon S, Ibaragi S, Ono K, Kunisada Y, Obata K, Masui M, Shimo T, Sasaki A. High mobility group box 1 induces bone pain associated with bone invasion in a mouse model of advanced head and neck cancer. Oncol Rep. 2020 Dec;44(6):2547-2558. Epub 2020 Oct 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shepherd AJ, Mickle AD, Kadunganattil S, Hu H, Mohapatra DP. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Peptide Elicits Peripheral TRPV1-dependent Mechanical Hypersensitivity. Front Cell Neurosci. 2018 Feb 15;12:38. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xu Q, Zhang XM, Duan KZ, Gu XY, Han M, Liu BL, Zhao ZQ, Zhang YQ. Peripheral TGF-β1 signaling is a critical event in bone cancer-induced hyperalgesia in rodents. J Neurosci. 2013 Dec 4;33(49):19099-111. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sevcik MA, Ghilardi JR, Peters CM, Lindsay TH, Halvorson KG, Jonas BM, Kubota K, Kuskowski MA, Boustany L, Shelton DL, Mantyh PW. Anti-NGF therapy profoundly reduces bone cancer pain and the accompanying increase in markers of peripheral and central sensitization. Pain. 2005 May;115(1-2):128-41. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Zhang R, Dong C, Jiao L, Xu L, Liu J, Wang Z, Lao L. Transient Receptor Potential Channel and Interleukin-17A Involvement in LTTL Gel Inhibition of Bone Cancer Pain in a Rat Model. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015 Jul;14(4):381-93. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang D, Kong LY, Cai J, Li S, Liu XD, Han JS, Xing GG. Interleukin-6-mediated functional upregulation of TRPV1 receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons through the activation of JAK/PI3K signaling pathway: roles in the development of bone cancer pain in a rat model. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):1124-1144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Cai J, Han Y, Xiao X, Meng XL, Su L, Liu FY, Xing GG, Wan Y. Enhanced function of TRPV1 via up-regulation by insulin-like growth factor-1 in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Eur J Pain. 2014 Jul;18(6):774-84. Epub 2013 Oct 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahidi Ferdowsi P, Ahuja KDK, Beckett JM, Myers S. TRPV1 Activation by Capsaicin Mediates Glucose Oxidation and ATP Production Independent of Insulin Signalling in Mouse Skeletal Muscle Cells. Cells. 2021 Jun 21;10(6):1560. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qian HY, Zhou F, Wu R, Cao XJ, Zhu T, Yuan HD, Chen YN, Zhang PA. Metformin Attenuates Bone Cancer Pain by Reducing TRPV1 and ASIC3 Expression. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Aug 4;12:713944. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jeske NA, Diogenes A, Ruparel NB, Fehrenbacher JC, Henry M, Akopian AN, Hargreaves KM. A-kinase anchoring protein mediates TRPV1 thermal hyperalgesia through PKA phosphorylation of TRPV1. Pain. 2008 Sep 15;138(3):604-616. Epub 2008 Apr 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frey E, Karney-Grobe S, Krolak T, Milbrandt J, DiAntonio A. TRPV1 Agonist, Capsaicin, Induces Axon Outgrowth after Injury via Ca2+/PKA Signaling. eNeuro. 2018 May 30;5(3):ENEURO.0095-18.2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu CC, Chien KH, Yarmishyn AA, Buddhakosai W, Wu WJ, Lin TC, Chiou SH, Chen JT, Peng CH, Hwang DK, Chen SJ, Chang YL. Modulation of osmotic stress-induced TRPV1 expression rescues human iPSC-derived retinal ganglion cells through PKA. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019 Sep 23;10(1):284. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guo SH, Lin JP, Huang LE, Yang Y, Chen CQ, Li NN, Su MY, Zhao X, Zhu SM, Yao YX. Silencing of spinal Trpv1 attenuates neuropathic pain in rats by inhibiting CAMKII expression and ERK2 phosphorylation. Sci Rep. 2019 Feb 26;9(1):2769. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bao Y, Gao Y, Hou W, Yang L, Kong X, Zheng H, Li C, Hua B. Engagement of signaling pathways of protease-activated receptor 2 and μ-opioid receptor in bone cancer pain and morphine tolerance. Int J Cancer. 2015 Sep 15;137(6):1475-83. Epub 2015 Mar 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niiyama Y, Kawamata T, Yamamoto J, Furuse S, Namiki A. SB366791, a TRPV1 antagonist, potentiates analgesic effects of systemic morphine in a murine model of bone cancer pain. Br J Anaesth. 2009 Feb;102(2):251-8. Epub 2008 Nov 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto J, Kawamata T, Niiyama Y, Omote K, Namiki A. Down-regulation of mu opioid receptor expression within distinct subpopulations of dorsal root ganglion neurons in a murine model of bone cancer pain. Neuroscience. 2008 Feb 6;151(3):843-53. Epub 2007 Nov 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson DM, Dubin AE, Shah C, Nasser N, Chang L, Dax SL, Jetter M, Breitenbucher JG, Liu C, Mazur C, Lord B, Gonzales L, Hoey K, Rizzolio M, Bogenstaetter M, Codd EE, Lee DH, Zhang SP, Chaplan SR, Carruthers NI. Identification and biological evaluation of 4-(3-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carboxylic acid (5-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-yl)amide, a high affinity TRPV1 (VR1) vanilloid receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2005 Mar 24;48(6):1857-72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui Q, Xu C, Zhuang L, Xia S, Chen Y, Peng P, Yu S. A new rat model of bone cancer pain produced by rat breast cancer cells implantation of the shaft of femur at the third trochanter level. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013 Feb;14(2):193-9. Epub 2012 Dec 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shimosato G, Amaya F, Ueda M, Tanaka Y, Decosterd I, Tanaka M. Peripheral inflammation induces up-regulation of TRPV2 expression in rat DRG. Pain. 2005 Dec 15;119(1-3):225-232. Epub 2005 Nov 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu ZH, Niu Z, Liu Y, Liu PL, Lin XL, Zhang L, Chen L, Song Y, Sun R, Zhang HL. TET1-TRPV4 Signaling Contributes to Bone Cancer Pain in Rats. Brain Sci. 2023 Apr 10;13(4):644. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen X, Zhang J, Wang K. Inhibition of intracellular proton-sensitive Ca2+-permeable TRPV3 channels protects against ischemic brain injury. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022 May;12(5):2330-2347. Epub 2022 Jan 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mandadi S, Sokabe T, Shibasaki K, Katanosaka K, Mizuno A, Moqrich A, Patapoutian A, Fukumi-Tominaga T, Mizumura K, Tominaga M. TRPV3 in keratinocytes transmits temperature information to sensory neurons via ATP. Pflugers Arch. 2009 Oct;458(6):1093-102. Epub 2009 Aug 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Song Z, Chen X, Zhao Q, Stanic V, Lin Z, Yang S, Chen T, Chen J, Yang Y. Hair Loss Caused by Gain-of-Function Mutant TRPV3 Is Associated with Premature Differentiation of Follicular Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2021 Aug;141(8):1964-1974. Epub 2021 Mar 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aijima R, Wang B, Takao T, Mihara H, Kashio M, Ohsaki Y, Zhang JQ, Mizuno A, Suzuki M, Yamashita Y, Masuko S, Goto M, Tominaga M, Kido MA. The thermosensitive TRPV3 channel contributes to rapid wound healing in oral epithelia. FASEB J. 2015 Jan;29(1):182-92. Epub 2014 Oct 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earley S, Pauyo T, Drapp R, Tavares MJ, Liedtke W, Brayden JE. TRPV4-dependent dilation of peripheral resistance arteries influences arterial pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009 Sep;297(3):H1096-102. Epub 2009 Jul 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lee WJ, Shim WS. Cutaneous Neuroimmune Interactions of TSLP and TRPV4 Play Pivotal Roles in Dry Skin-Induced Pruritus. Front Immunol. 2021 Dec 2;12:772941. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Das R, Goswami C. Role of TRPV4 in skeletal function and its mutant-mediated skeletal disorders. Curr Top Membr. 2022;89:221-246. Epub 2022 Sep 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain SM, Romac JM, Shahid RA, Pandol SJ, Liedtke W, Vigna SR, Liddle RA. TRPV4 channel opening mediates pressure-induced pancreatitis initiated by Piezo1 activation. J Clin Invest. 2020 May 1;130(5):2527-2541. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naert R, López-Requena A, Voets T, Talavera K, Alpizar YA. Expression and Functional Role of TRPV4 in Bone Marrow-Derived CD11c+ Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Jul 10;20(14):3378. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hu K, Sun H, Gui B, Sui C. TRPV4 functions in flow shear stress induced early osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017 Jul;91:841-848. Epub 2017 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wijst J, van Goor MK, Schreuder MF, Hoenderop JG. TRPV5 in renal tubular calcium handling and its potential relevance for nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int. 2019 Dec;96(6):1283-1291. Epub 2019 Jun 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burren CP, Caswell R, Castle B, Welch CR, Hilliard TN, Smithson SF, Ellard S. TRPV6 compound heterozygous variants result in impaired placental calcium transport and severe undermineralization and dysplasia of the fetal skeleton. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Sep;176(9):1950-1955. Epub 2018 Aug 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu N, Lu W, Dai X, Qu X, Zhu C. The role of TRPV channels in osteoporosis. Mol Biol Rep. 2022 Jan;49(1):577-585. Epub 2021 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi F, Bellini G, Tortora C, Bernardo ME, Luongo L, Conforti A, Starc N, Manzo I, Nobili B, Locatelli F, Maione S. CB(2) and TRPV(1) receptors oppositely modulate in vitro human osteoblast activity. Pharmacol Res. 2015 Sep;99:194-201. Epub 2015 Jun 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing L, Liu K, Wang F, Su Y. Role of mechanically-sensitive cation channels Piezo1 and TRPV4 in trabecular meshwork cell mechanotransduction. Hum Cell. 2024 Mar;37(2):394-407. Epub 2024 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai K, Liskova A, Kubatka P, Büsselberg D. Calcium Entry through TRPV1: A Potential Target for the Regulation of Proliferation and Apoptosis in Cancerous and Healthy Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jun 11;21(11):4177. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghilardi JR, Röhrich H, Lindsay TH, Sevcik MA, Schwei MJ, Kubota K, Halvorson KG, Poblete J, Chaplan SR, Dubin AE, Carruthers NI, Swanson D, Kuskowski M, Flores CM, Julius D, Mantyh PW. Selective blockade of the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 attenuates bone cancer pain. J Neurosci. 2005 Mar 23;25(12):3126-31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang S, Zhao J, Meng Q. AAV-mediated siRNA against TRPV1 reduces nociception in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Neurol Res. 2019 Nov;41(11):972-979. Epub 2019 Jul 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benitez-Del-Castillo JM, Moreno-Montañés J, Jiménez-Alfaro I, Muñoz-Negrete FJ, Turman K, Palumaa K, Sádaba B, González MV, Ruz V, Vargas B, Pañeda C, Martínez T, Bleau AM, Jimenez AI. Safety and Efficacy Clinical Trials for SYL1001, a Novel Short Interfering RNA for the Treatment of Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016 Nov 1;57(14):6447-6454. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobasheri A, Rannou F, Ivanavicius S, Conaghan PG. Targeting the TRPV1 pain pathway in osteoarthritis of the knee. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2024 Oct;28(10):843-856. Epub 2024 Oct 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown DC, Agnello K, Iadarola MJ. Intrathecal resiniferatoxin in a dog model: efficacy in bone cancer pain. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):1018-1024. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Menéndez L, Juárez L, García E, García-Suárez O, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Analgesic effects of capsazepine and resiniferatoxin on bone cancer pain in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2006 Jan 23;393(1):70-3. Epub 2005 Oct 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iadarola MJ, Mannes AJ. The vanilloid agonist resiniferatoxin for interventional-based pain control. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11(17):2171-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szallasi A. Targeting TRPV1 for Cancer Pain Relief: Can It Work? Cancers (Basel). 2024 Feb 2;16(3):648. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heiss, J.; Iadarola, M.J.; Cantor, F.; Oughourli, R.; Smith, R.; Mannes, A. A Phase I study of the intrathecal administration of resiniferatoxin for treating severe refractory pain associated with advanced cancer. J. Pain 2014, 15, S65. [CrossRef]

- Wahl P, Foged C, Tullin S, Thomsen C. Iodo-resiniferatoxin, a new potent vanilloid receptor antagonist. Mol Pharmacol. 2001 Jan;59(1):9-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honore P, Chandran P, Hernandez G, Gauvin DM, Mikusa JP, Zhong C, Joshi SK, Ghilardi JR, Sevcik MA, Fryer RM, Segreti JA, Banfor PN, Marsh K, Neelands T, Bayburt E, Daanen JF, Gomtsyan A, Lee CH, Kort ME, Reilly RM, Surowy CS, Kym PR, Mantyh PW, Sullivan JP, Jarvis MF, Faltynek CR. Repeated dosing of ABT-102, a potent and selective TRPV1 antagonist, enhances TRPV1-mediated analgesic activity in rodents, but attenuates antagonist-induced hyperthermia. Pain. 2009 Mar;142(1-2):27-35. Epub 2009 Jan 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai H, Ozaki N, Shinoda M, Nagamine K, Tohnai I, Ueda M, Sugiura Y. Heat and mechanical hyperalgesia in mice model of cancer pain. Pain. 2005 Sep;117(1-2):19-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinoda M, Ogino A, Ozaki N, Urano H, Hironaka K, Yasui M, Sugiura Y. Involvement of TRPV1 in nociceptive behavior in a rat model of cancer pain. J Pain. 2008 Aug;9(8):687-99. Epub 2008 May 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazzari J, Balenko MD, Zacal N, Singh G. Identification of capsazepine as a novel inhibitor of system xc- and cancer-induced bone pain. J Pain Res. 2017 Apr 18;10:915-925. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fuseya S, Yamamoto K, Minemura H, Yamaori S, Kawamata T, Kawamata M. Systemic QX-314 Reduces Bone Cancer Pain through Selective Inhibition of Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Subfamily 1-expressing Primary Afferents in Mice. Anesthesiology. 2016 Jul;125(1):204-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Zhang J, Ren X, Liu Q, Yang X. The mechanism of quercetin in regulating osteoclast activation and the PAR2/TRPV1 signaling pathway in the treatment of bone cancer pain. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2018 Nov 1;11(11):5149-5156. [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoshijima H, Hunt M, Nagasaka H, Yaksh T. Systematic Review of Systemic and Neuraxial Effects of Acetaminophen in Preclinical Models of Nociceptive Processing. J Pain Res. 2021 Nov 12;14:3521-3552. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bao Y, Wang G, Gao Y, Du M, Yang L, Kong X, Zheng H, Hou W, Hua B. Topical treatment with Xiaozheng Zhitong Paste alleviates bone cancer pain by inhibiting proteinase-activated receptor 2 signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2015 Sep;34(3):1449-59. Epub 2015 Jun 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu BL, Cao QL, Zhao X, Liu HZ, Zhang YQ. Inhibition of TRPV1 by SHP-1 in nociceptive primary sensory neurons is critical in PD-L1 analgesia. JCI Insight. 2020 Oct 15;5(20):e137386. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heo MH, Kim JY, Hwang I, Ha E, Park KU. Analgesic effect of quetiapine in a mouse model of cancer-induced bone pain. Korean J Intern Med. 2017 Nov;32(6):1069-1074. Epub 2017 Jan 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kawamata T, Niiyama Y, Yamamoto J, Furuse S. Reduction of bone cancer pain by CB1 activation and TRPV1 inhibition. J Anesth. 2010 Apr;24(2):328-32. Epub 2010 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meents JE, Ciotu CI, Fischer MJM. TRPA1: a molecular view. J Neurophysiol. 2019 Feb 1;121(2):427-443. Epub 2018 Nov 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng YT, Woo J, Luna-Figueroa E, Maleki E, Harmanci AS, Deneen B. Social deprivation induces astrocytic TRPA1-GABA suppression of hippocampal circuits. Neuron. 2023 Apr 19;111(8):1301-1315.e5. Epub 2023 Feb 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iannone LF, Nassini R, Patacchini R, Geppetti P, De Logu F. Neuronal and non-neuronal TRPA1 as therapeutic targets for pain and headache relief. Temperature (Austin). 2022 May 29;10(1):50-66. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cho HJ, Callaghan B, Bron R, Bravo DM, Furness JB. Identification of enteroendocrine cells that express TRPA1 channels in the mouse intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2014 Apr;356(1):77-82. Epub 2014 Jan 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luostarinen S, Hämäläinen M, Hatano N, Muraki K, Moilanen E. The inflammatory regulation of TRPA1 expression in human A549 lung epithelial cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Oct;70:102059. Epub 2021 Jul 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao M, Ding N, Wang H, Zu S, Liu H, Wen J, Liu J, Ge N, Wang W, Zhang X. Activation of TRPA1 in Bladder Suburothelial Myofibroblasts Counteracts TGF-β1-Induced Fibrotic Changes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 30;24(11):9501. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vélez-Ortega AC, Stepanyan R, Edelmann SE, Torres-Gallego S, Park C, Marinkova DA, Nowacki JS, Sinha GP, Frolenkov GI. TRPA1 activation in non-sensory supporting cells contributes to regulation of cochlear sensitivity after acoustic trauma. Nat Commun. 2023 Jun 30;14(1):3871. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang Z, Ye D, Ye J, Wang M, Liu J, Jiang H, Xu Y, Zhang J, Chen J, Wan J. The TRPA1 Channel in the Cardiovascular System: Promising Features and Challenges. Front Pharmacol. 2019 Oct 18;10:1253. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kudsi SQ, de David Antoniazzi CT, Camponogara C, Meira GM, de Amorim Ferreira M, da Silva AM, Dalenogare DP, Zaccaron R, Dos Santos Stein C, Silveira PCL, Moresco RN, Oliveira SM, Ferreira J, Trevisan G. Topical application of a TRPA1 antagonist reduced nociception and inflammation in a model of traumatic muscle injury in rats. Inflammopharmacology. 2023 Dec;31(6):3153-3166. Epub 2023 Sep 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura M, Sase T, Higashikawa A, Sato M, Sato T, Tazaki M, Shibukawa Y. High pH-Sensitive TRPA1 Activation in Odontoblasts Regulates Mineralization. J Dent Res. 2016 Aug;95(9):1057-64. Epub 2016 Apr 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss F, Kormos V, Szőke É, Kecskés A, Tóth N, Steib A, Szállási Á, Scheich B, Gaszner B, Kun J, Fülöp G, Pohóczky K, Helyes Z. Functional Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 and Vanilloid 1 Ion Channels Are Overexpressed in Human Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Feb 8;23(3):1921. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu YT, Yen SL, Li CF, Chan TC, Chen TJ, Lee SW, He HL, Chang IW, Hsing CH, Shiue YL. Overexpression of Transient Receptor Protein Cation Channel Subfamily A Member 1, Confers an Independent Prognostic Indicator in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. J Cancer. 2016 Jun 8;7(10):1181-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Almeida AS, Rigo FK, De Prá SD, Milioli AM, Pereira GC, Lückemeyer DD, Antoniazzi CT, Kudsi SQ, Araújo DMPA, Oliveira SM, Ferreira J, Trevisan G. Role of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) on nociception caused by a murine model of breast carcinoma. Pharmacol Res. 2020 Feb;152:104576. Epub 2019 Nov 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cojocaru F, Şelescu T, Domocoş D, Măruţescu L, Chiritoiu G, Chelaru NR, Dima S, Mihăilescu D, Babes A, Cucu D. Functional expression of the transient receptor potential ankyrin type 1 channel in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2021 Jan 21;11(1):2018. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2021 Apr 19;11(1):8853. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88169-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Faris P, Rumolo A, Pellavio G, Tanzi M, Vismara M, Berra-Romani R, Gerbino A, Corallo S, Pedrazzoli P, Laforenza U, Montagna D, Moccia F. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) mediates reactive oxygen species-induced Ca2+ entry, mitochondrial dysfunction, and caspase-3/7 activation in primary cultures of metastatic colorectal carcinoma cells. Cell Death Discov. 2023 Jul 1;9(1):213. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vancauwenberghe E, Noyer L, Derouiche S, Lemonnier L, Gosset P, Sadofsky LR, Mariot P, Warnier M, Bokhobza A, Slomianny C, Mauroy B, Bonnal JL, Dewailly E, Delcourt P, Allart L, Desruelles E, Prevarskaya N, Roudbaraki M. Activation of mutated TRPA1 ion channel by resveratrol in human prostate cancer associated fibroblasts (CAF). Mol Carcinog. 2017 Aug;56(8):1851-1867. Epub 2017 May 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudhud L, Rozmer K, Kecskés A, Pohóczky K, Bencze N, Buzás K, Szőke É, Helyes Z. Transient Receptor Potential Ankyrin 1 Ion Channel Is Expressed in Osteosarcoma and Its Activation Reduces Viability. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Mar 28;25(7):3760. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laursen WJ, Anderson EO, Hoffstaetter LJ, Bagriantsev SN, Gracheva EO. Species-specific temperature sensitivity of TRPA1. Temperature (Austin). 2015 Feb 11;2(2):214-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laursen WJ, Bagriantsev SN, Gracheva EO. TRPA1 channels: chemical and temperature sensitivity. Curr Top Membr. 2014;74:89-112. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So K, Tei Y, Zhao M, Miyake T, Hiyama H, Shirakawa H, Imai S, Mori Y, Nakagawa T, Matsubara K, Kaneko S. Hypoxia-induced sensitisation of TRPA1 in painful dysesthesia evoked by transient hindlimb ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Sci Rep. 2016 Mar 17;6:23261. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weng Y, Batista-Schepman PA, Barabas ME, Harris EQ, Dinsmore TB, Kossyreva EA, Foshage AM, Wang MH, Schwab MJ, Wang VM, Stucky CL, Story GM. Prostaglandin metabolite induces inhibition of TRPA1 and channel-dependent nociception. Mol Pain. 2012 Sep 27;8:75. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gouin O, L'Herondelle K, Lebonvallet N, Le Gall-Ianotto C, Sakka M, Buhé V, Plée-Gautier E, Carré JL, Lefeuvre L, Misery L, Le Garrec R. TRPV1 and TRPA1 in cutaneous neurogenic and chronic inflammation: pro-inflammatory response induced by their activation and their sensitization. Protein Cell. 2017 Sep;8(9):644-661. Epub 2017 Mar 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwartz ES, Christianson JA, Chen X, La JH, Davis BM, Albers KM, Gebhart GF. Synergistic role of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in pancreatic pain and inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2011 Apr;140(4):1283-1291.e1-2. Epub 2010 Dec 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhu P, Tao H, Chen K, Chu M, Wang Q, Yang X, Zhou J, Yang H, Geng D. TRPA1 aggravates osteoclastogenesis and osteoporosis through activating endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated by SRXN1. Cell Death Dis. 2024 Aug 27;15(8):624. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Francesconi O, Corzana F, Kontogianni GI, Pesciullesi G, Gualdani R, Supuran CT, Angeli A, Kavasi RM, Chatzinikolaidou M, Nativi C. Lipoyl-Based Antagonists of Transient Receptor Potential Cation A (TRPA1) Downregulate Osteosarcoma Cell Migration and Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2022 Sep 13;5(11):1119-1127. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu Q, Feng L, Han X, Zhang W, Zhang H, Xu L. The TRPA1 Channel Mediates Mechanical Allodynia and Thermal Hyperalgesia in a Rat Bone Cancer Pain Model. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2021 Mar 22;2:638620. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Forni MF, Domínguez-Amorocho OA, de Assis LVM, Kinker GS, Moraes MN, Castrucci AML, Câmara NOS. An Immunometabolic Shift Modulates Cytotoxic Lymphocyte Activation During Melanoma Progression in TRPA1 Channel Null Mice. Front Oncol. 2021 May 10;11:667715. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Antoniazzi CTD, Nassini R, Rigo FK, Milioli AM, Bellinaso F, Camponogara C, Silva CR, de Almeida AS, Rossato MF, De Logu F, Oliveira SM, Cunha TM, Geppetti P, Ferreira J, Trevisan G. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) plays a critical role in a mouse model of cancer pain. Int J Cancer. 2019 Jan 15;144(2):355-365. Epub 2018 Oct 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Almeida AS, Pereira GC, Brum EDS, Silva CR, Antoniazzi CTD, Ardisson-Araújo D, Oliveira SM, Trevisan G. Role of TRPA1 expressed in bone tissue and the antinociceptive effect of the TRPA1 antagonist repeated administration in a breast cancer pain model. Life Sci. 2021 Jul 1;276:119469. Epub 2021 Mar 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang Y, Fliegert R, Guse AH, Lü W, Du J. A structural overview of the ion channels of the TRPM family. Cell Calcium. 2020 Jan;85:102111. Epub 2019 Nov 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kashio M, Tominaga M. TRP channels in thermosensation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2022 Aug;75:102591. Epub 2022 Jun 18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangeel L, Benoit M, Miron Y, Miller PE, De Clercq K, Chaltin P, Verfaillie C, Vriens J, Voets T. Functional expression and pharmacological modulation of TRPM3 in human sensory neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2020 Jun;177(12):2683-2695. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gandini MA, Zamponi GW. Navigating the Controversies: Role of TRPM Channels in Pain States. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Sep 24;25(19):10284. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Almasi S, Long CY, Sterea A, Clements DR, Gujar S, El Hiani Y. TRPM2 silencing causes G2/M arrest and apoptosis in lung cancer cells via increasing intracellular ROS and RNS levels and activating the JNK pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem (2019) 52:742–57. [CrossRef]

- Maeda T, Suzuki A, Koga K, Miyamoto C, Maehata Y, Ozawa S, et al. TRPM5 mediates acidic extracellular pH signaling and TRPM5 inhibition reduces spontaneous metastasis in mouse B16-BL6 melanoma cells. Oncotarget (2017) 8:78312–26. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Xu SH, Chen Z, Zeng QX, Li ZJ, Chen ZM. TRPM7 overexpression enhances the cancer stem cell-like and metastatic phenotypes of lung cancer through modulation of the Hsp90a/uPA/MMP2 signaling pathway. BMC Cancer (2018) 18:1167. [CrossRef]

- Samart P, Luanpitpong S, Rojanasakul Y, Issaragrisil S. O- GlcNAcylation homeostasis controlled by calcium influx channels regulates multiple myeloma dissemination. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2021) 40:100. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Mikrani R, He Y, Faran Ashraf Baig MM, Abbas M, Naveed M, Tang M, Zhang Q, Li C, Zhou X. TRPM8 channels: A review of distribution and clinical role. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020 Sep 5;882:173312. Epub 2020 Jun 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa SV, Casas Z, Albarracín SL, Sutachan JJ, Torres YP. Therapeutic potential of TRPM8 channels in cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Mar 22;14:1098448. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu Y, Leng A, Li L, Yang B, Shen S, Chen H, et al. AMTB, a TRPM8 antagonist, suppresses growth and metastasis of osteosarcoma through repressing the TGFb signalling pathway. Cell Death Dis (2022) 13:288. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto Y, Ohkubo T, Ikebe T, Yamazaki J. Blockade of TRPM8 activity reduces the invasion potential of oral squamous carcinoma cell lines. Int J Oncol (2012) 40:1431–40. [CrossRef]

- Di Sarno V, Giovannelli P, Medina-Peris A, Ciaglia T, Di Donato M, Musella S, et al. New TRPM8 blockers exert anticancer activity over castration-resistant prostate cancer models. Eur J Med Chem (2022) 238:114435. [CrossRef]

- Liu T, Liao Y, Tao H, Zeng J, Wang G, Yang Z, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Zhou J, Wang X. RNA interference-mediated depletion of TRPM8 enhances the efficacy of epirubicin chemotherapy in prostate cancer LNCaP and PC3 cells. Oncol Lett. 2018 Apr;15(4):4129-4136. Epub 2018 Jan 24. Erratum in: Oncol Lett. 2022 Mar;23(3):91. doi: 10.3892/ol.2022.13211. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Slominski A. Cooling skin cancer: menthol inhibits melanoma growth. Focus on "TRPM8 activation suppresses cellular viability in human melanoma". Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008 Aug;295(2):C293-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shin M, Mori S, Mizoguchi T, Arai A, Kajiya H, Okamoto F, Bartlett JD, Matsushita M, Udagawa N, Okabe K. Mesenchymal cell TRPM7 expression is required for bone formation via the regulation of chondrogenesis. Bone. 2023 Jan;166:116579. Epub 2022 Oct 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria M, Matta J, Honjol Y, Schupbach D, Mwale F, Harvey E, Merle G. Decoding Cold Therapy Mechanisms of Enhanced Bone Repair through Sensory Receptors and Molecular Pathways. Biomedicines. 2024 Sep 9;12(9):2045. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qiao W, Wong KHM, Shen J, Wang W, Wu J, Li J, Lin Z, Chen Z, Matinlinna JP, Zheng Y, Wu S, Liu X, Lai KP, Chen Z, Lam YW, Cheung KMC, Yeung KWK. TRPM7 kinase-mediated immunomodulation in macrophage plays a central role in magnesium ion-induced bone regeneration. Nat Commun. 2021 May 17;12(1):2885. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yao H, Zhang L, Yan S, He Y, Zhu H, Li Y, Wang D, Yang K. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound/nanomechanical force generators enhance osteogenesis of BMSCs through microfilaments and TRPM7. J Nanobiotechnology. 2022 Aug 13;20(1):378. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Acharya TK, Kumar S, Tiwari N, Ghosh A, Tiwari A, Pal S, Majhi RK, Kumar A, Das R, Singh A, Maji PK, Chattopadhyay N, Goswami L, Goswami C. TRPM8 channel inhibitor-encapsulated hydrogel as a tunable surface for bone tissue engineering. Sci Rep. 2021 Feb 12;11(1):3730. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Son A, Kang N, Kang JY, Kim KW, Yang YM, Shin DM. TRPM3/TRPV4 regulates Ca2+-mediated RANKL/NFATc1 expression in osteoblasts. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018 Oct 15;61(4):207-218. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fozzato S, Baranzini N, Bossi E, Cinquetti R, Grimaldi A, Campomenosi P, Surace MF. TRPV4 and TRPM8 as putative targets for chronic low back pain alleviation. Pflugers Arch. 2021 Feb;473(2):151-165. Epub 2020 Sep 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang D, Treede RD, Köhr G. Electrophysiological evidence that TRPM3 is a candidate in latent spinal sensitization of chronic low back pain. Neurosci Lett. 2023 Nov 1;816:137509. Epub 2023 Oct 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).