Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

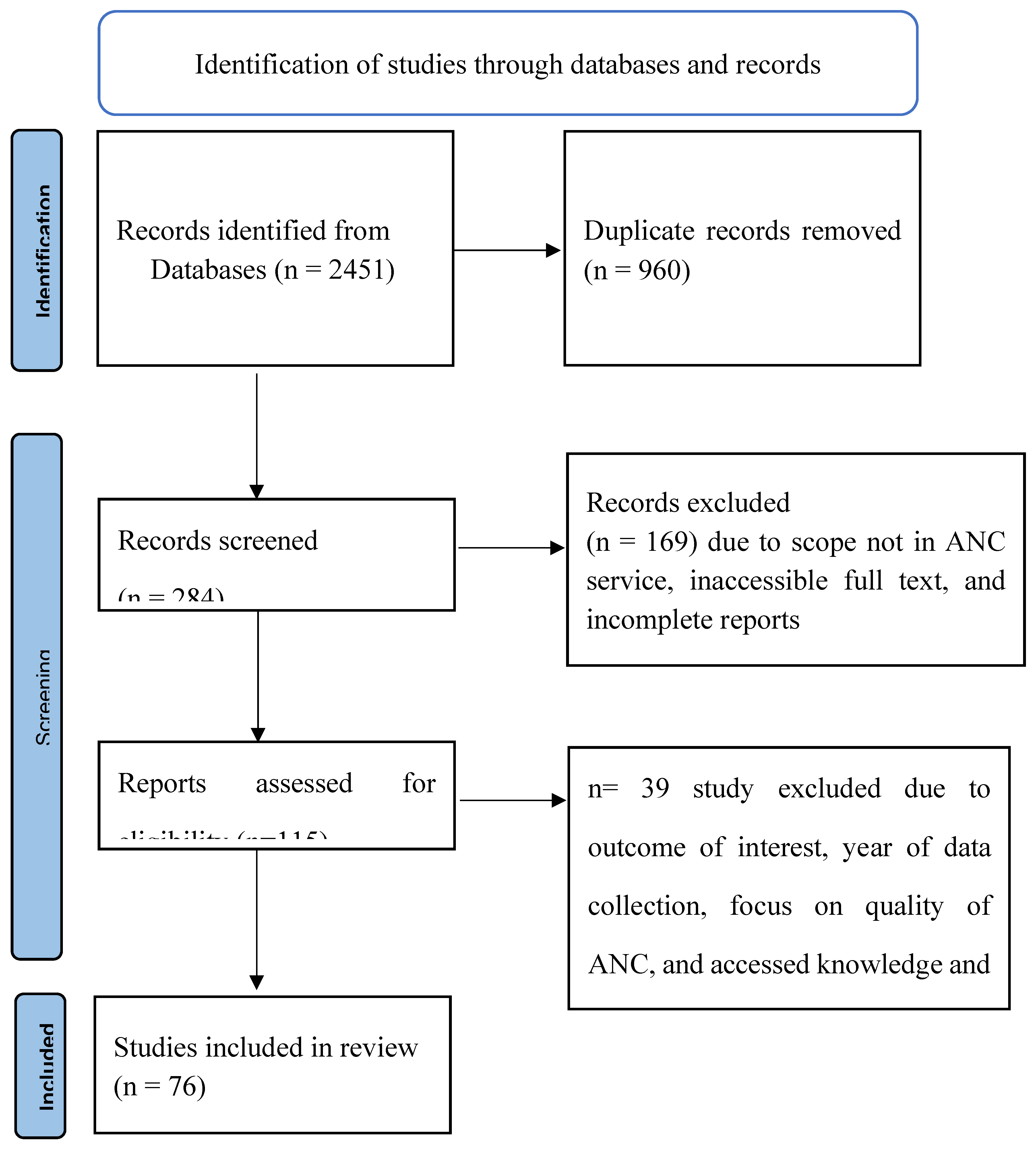

Introduction: In Ethiopia, there has been considerable recent investment and prioritization in the maternal health program. However, coverage rates have been low and stagnant for a long time, indicating the existence of systemic utilization barriers. Therefore, it is fundamental to synthesize the current body of knowledge to successfully address these problems and enhance program effectiveness to increase antenatal care (ANC) uptake. Methods: We conducted a scoping review of the literature. Using various combinations of search strategies, we searched Pubmed/Medline, WHO Library, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and Google for this review. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) were used to conduct the review. We included studies that used any study design, data collection, and analysis methods related to antenatal care utilization. Results: A total of 76 studies, national surveys and estimates were included in this review. The analysis revealed that ANC utilization coverage varied greatly by region, from 27% in Somali to 90.6% in the Oromia region, with significant disparities in socioeconomic status, access to healthcare, and vaccination knowledge. Ten priority research areas covering various aspects of the national ANC services were identified through a comprehensive review of the existing body of knowledge led by experts using the Delphi method. Conclusion: The barriers to recommended ANC service utilization differ depending on the context, suggesting that evidence-based, locally customized interventions must be developed and implemented. This review also identified evidence gaps, focusing on health system-related utilization barriers at the lower level, and identified additional research priorities in Ethiopia’s ANC service. The first step in developing and executing targeted program approaches could be identifying coverage of ANC services utilization among those with disadvantages.

Keywords:

Introduction

Rationale of the Scoping Review

Objectives of the Review

General Objective

- To investigate the current state of comprehensive knowledge regarding national ANC utilization.

- To identify the barriers influencing the utilization of ANC services.

- To determine recent knowledge gaps and highlight potential research areas in the ANC service of Ethiopia.

Methods

Design

Search Strategy

Selection Criteria to Include Studies

Data Abstraction and Analysis

Results and Discussion

Evidence on Use Of Antenatal Care Services in Ethiopia

ANC Service Utilization Coverage

Antenatal Care Dropout Rate

Timely Initiation of the First Antenatal Care Visit

Determinants of Antenatal Care Service Utilization

Socio-Economic and Demographic Determinants

Maternal Age

Educational Status of Women and Their Husbands

Occupational Status of Women and Their Husbands

Place of Residence

Household Wealth Index or Status

Marital Status

Exposure to Media and Information

Socio-Cultural Determinants

Knowledge of Mothers Regarding the ODS and Practices of Women About BPCR

Maternal Decision-Making Authority and Gender Role

Health Facility Related Determinants and Perceived Quality of ANC

Obstetric Related Determinants

The Identified Priorities Area for Research in the Antenatal Care Service

- Strengthening the linkage of community-based outreach services

- Adoption and adaptation of new technologies for the antenatal care service

- Availability of supplies, equipment, and drugs at the health facility level

- A comprehensive community-level data confirmation mechanism for the antenatal care service

- Active community engagement and health care provider-client communication

- Effects of electronic community health information system implementation on antenatal care services

- Women’s autonomy and empowerment in antenatal care services

- Antenatal care service provision mechanisms in displaced communities

- Revitalizing antenatal care services in pastoralist communities and slum urban settings

- Mechanisms that increase husband involvement

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- World Health Organization (2022) Promoting healthy pregnancy. Available online from https://www.who.int/activities/promoting-healthy-pregnancy.

- World Health Organization (2023) Maternal health. Available online from https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1.

- Boston Consulting Group (2023) Investing in the Next Generation of Women’s Health. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/investing-in-future-of-womens-health.

- Sai FT (1987) Sai FT. The Safe Motherhood Initiative: a call for action. IPPF Med Bull. ;21(3):1-2.

- UNFPA (1994) International Conference on Population and Development. Available from https://www.unfpa.org/icpd.

- UNDP (2000) Millennium Development Goals. Available from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sdgoverview/mdg_goals.html.

- Global University Network for Innovation (2016) Global University Network for Innovation. International Conference on Sustainable Development Goals: Actors and Implementation. Available from http://www.guninetwork.org/activity/international-conference-sustainable-development-goals-actors-and-implementation.

- World Health Organization (2023) WHO announces the Technical Advisory Group meeting on Maternal Perinatal Health. Available online from https://www.who.int/news/item/22-10-2023-who-announces-the-technical-advisory-group-meeting-on-maternal-perinatal-health.

- EFMOH (2010) Ministry of Health Ethiopia, Health sector Development Program (HSDP IV). MoH,.

- Negussie A, Girma G (2017) Is the role of Health Extension Workers in the delivery of maternal and child health care services a significant attribute? The case of Dale district, southern Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research 17: 1-8.

- Yitbarek K, Abraham G, Morankar S (2019) Contribution of women’s development army to maternal and child health in Ethiopia: a systematic review of evidence. BMJ open 9: e025937.

- FMOH (2016) National Reproductive Health Strategy to Improve Maternal and Child Health, FMOH, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016-2022.

- EFMOH (2020) Ethiopia Health Sector Transformation Plan (2020/21-2024/25).

- World Health Organization (2023) Maternal mortality. Available online from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality.

- World Health Organization (2016) WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Available online from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912.

- Arsenault C, Jordan K, Lee D, Dinsa G, Manzi F, et al. (2018) Equity in antenatal care quality: an analysis of 91 national household surveys. The Lancet Global Health 6: e1186-e1195. [CrossRef]

- CSA (2019) CSA. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- UNICEF. (2017) UNICEF Annual Report 2017 Ethiopia;1–69.

- WHO (2022) WHO Ethiopia Annual Report 2022. Available from https://www.afro.who.int/countries/ethiopia/publication/who-ethiopia-annual-report-2022.

- FMOH (2018) Annual Health Sector Performance report, 2010 E.C.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology 8: 19-32.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, et al. (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine 169: 467-473.

- Pollock D, Davies EL, Peters MD, Tricco AC, Alexander L, et al. (2021) Undertaking a scoping review: A practical guide for nursing and midwifery students, clinicians, researchers, and academics. Journal of advanced nursing 77: 2102-2113.

- Moller A-B, Newby H, Hanson C, Morgan A, El Arifeen S, et al. (2018) Measures matter: a scoping review of maternal and newborn indicators. PloS one 13: e0204763. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA https://prisma-statement.org//PRISMAStatement/FlowDiagram.aspx. Accessed 12 December 2022.

- Worku AG, Tilahun HA, Belay H, Mohammedsanni A, Wendrad N, et al. (2022) Maternal Service Coverage and Its Relationship To Health Information System Performance: A Linked Facility and Population-Based Survey in Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract 10. [CrossRef]

- EPHI (2022) Understanding the Drivers of Reduction in Maternal and Neonatal Mortality in Ethiopia — An in-depth Case Study of the Global Health Exemplars.

- CSA. (2001) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- CSA (2006) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- CSA (2011) CSA. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- CSA (2016) CSA. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2015. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- UNICEF (2022) UNICEF Ethiopia Annual Report 2022. Available online from https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/media/3941/file/Annual%20Report%202020.pdf.

- FMOH (2007) FMOH. Health and health related Indicators;1–66.

- FMOH (2014) Policy and practice information for action: Quarterly Health Bulletin;6(1).

- Umer A, Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Tschopp R, Hattendof J, et al. (2020) Antenatal care and skilled delivery service utilisation in Somali pastoral communities of eastern Ethiopia. Tropical Medicine & International Health 25: 328-337. [CrossRef]

- Jira C, Belachew T (2005) Determinants of antenatal care utilization in Jimma Town, SouthWest Ethiopia. Ethiopian journal of health Sciences 15.

- Tewodros B, Dibaba Y (2009) Factors affecting antenatal care utilization in Yem special woreda, southwestern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of health sciences 19.

- Dutamo Z, Assefa N, Egata G (2015) Maternal health care use among married women in Hossaina, Ethiopia. BMC Health Services Research 15: 1-9.

- Workie MS, Lakew AM (2018) Bayesian count regression analysis for determinants of antenatal care service visits among pregnant women in Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Journal of Big Data 5: 1-23.

- Worku AG, Yalew AW, Afework MF (2013) Factors affecting utilization of skilled maternal care in Northwest Ethiopia: a multilevel analysis. BMC international health and human rights 13: 1-11.

- Tadele F, Getachew N, Fentie K, Amdisa D (2022) Late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women in Jimma Zone Public Hospitals, Southwest Ethiopia, 2020. BMC Health Services Research 22: 632.

- Melaku YA, Weldearegawi B, Tesfay FH, Abera SF, Abraham L, et al. (2014) Poor linkages in maternal health care services—evidence on antenatal care and institutional delivery from a community-based longitudinal study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 14: 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Tsegay Y, Gebrehiwot T, Goicolea I, Edin K, Lemma H, et al. (2013) Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. International journal for equity in health 12: 1-10.

- Zelka MA, Yalew AW, Debelew GT (2022) Individual-level and community-level determinants of use of maternal health services in Northwest Ethiopia: a prospective follow-up study. BMJ open 12: e061293.

- Woldeamanuel BT (2022) Factors associated with inadequate prenatal care service utilization in Ethiopia according to the WHO recommended standard guidelines. Frontiers in Public Health 10: 998055.

- Hailemariam T, Atnafu A, Gezie LD, Tilahun B (2023) Utilization of optimal antenatal care, institutional delivery, and associated factors in Northwest Ethiopia. Scientific Reports 13: 1071.

- Gebrekirstos LG, Wube TB, Gebremedhin MH, Lake EA (2021) Magnitude and determinants of adequate antenatal care service utilization among mothers in Southern Ethiopia. Plos one 16: e0251477.

- Gebresilassie B, Belete T, Tilahun W, Berhane B, Gebresilassie S (2019) Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in public health institutions of Axum town, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2017: a mixed design study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 19: 1-11.

- Gulema H, Berhane Y (2017) Timing of First Antenatal Care Visit and its Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Public Health Facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 27: 139-146.

- Geleto A CC, Taddele T, Loxton D, (2020) Association between maternal mortality and caesarean section in Ethiopia: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Oct 6;20(1):588. [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) EaI, ” Ethiopia Minin Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Key Indicators Report: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, CSA and ICF, Maryland, USA.

- Borde MT, Loha E, Johansson KA, Lindtjorn B (2019) Utilisation of health services fails to meet the needs of pregnancy-related illnesses in rural southern Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 14: e0215195.

- Borde MT, Loha E, Johansson KA, Lindtjørn B (2020) Financial risk of seeking maternal and neonatal healthcare in southern Ethiopia: a cohort study of rural households. Int J Equity Health 19: 69.

- Borde MT, Loha E, Lindtjørn B (2020) Incidence of postpartum and neonatal illnesses and utilization of healthcare services in rural communities in southern Ethiopia: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 15: e0237852.

- Abosse Z WM, Ololo S, (2010) Factors influencing antenatal care service utilization in hadiya zone. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2010 Jul;20(2):75-82. [CrossRef]

- SA. M (2020) Magnitude and Determinants of Postnatal Care Service Utilization Among Women Who Gave Birth in the Last 12 Months in Northern Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Womens Health. 2020 Nov 13;12:1057-1064. [CrossRef]

- Berelie Y YD, Yismaw L, Alene M, (2020) Determinants of institutional delivery service utilization in Ethiopia: a population based cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020 Jul 8;20(1):1077. [CrossRef]

- Kifle D, et al., (2017) Maternal health care service seeking behaviors and associated factors among women in rural Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia: a triangulated community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health, 2017. 14(1): p. 6.

- Arvind Kumar Yadav et al. (2019) Trends, Differentials, and Social Determinants of Maternal Health Care Services Utilization in Rural India: An Analysis from Pooled Data. Women’s Health Reports. [CrossRef]

- Tekelab T, B. Yadecha, and A.S. Melka, (2015) Antenatal care and women’s decision making power as determinants of institutional delivery in rural area of Western Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 2015. 8(1): p. 769. [CrossRef]

- Tsegay Y GT, Goicolea I, et al., (2013) Determinants of antenatal and delivery care utilization in Tigray region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2013 May 14;12:30. [CrossRef]

- Amano A GA, Birhanu Z, (2012) Institutional delivery service utilization in Munisa Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012 Oct 8;12:105. [CrossRef]

- Melaku YA WB, Tesfay FH, et al. (2014) Poor linkages in maternal health care services-evidence on antenatal care and institutional delivery from a community-based longitudinal study in Tigray region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Dec 19;14:418. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal P MS SMM, Baral D MS, et al., (2018) Factors Affecting the Place of Delivery among Mothers Residing in Jhorahat VDC, Morang, Nepal. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2018 Jan;6(1):2-11.

- Mrisho M SJ, Mushi AK, et al., (2007) Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2007 Jul;12(7):862-72. [CrossRef]

- Yoseph M AS, Mekonnen FA, Sisay M, Gonete KA, (2020) Institutional delivery services utilization and its determinant factors among women who gave birth in the past 24 months in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020 Mar 30;20(1):265. [CrossRef]

- Adu J TE, Banchani E, Allison J, Mulay S, (2018) The effects of individual and community-level factors on maternal health outcomes in Ghana. PLoS ONE 13(11): e0207942. [CrossRef]

- Nigusie A AT, Yitayal M. (2020) Institutional delivery service utilization and associated factors in Ethiopia: a systematic review and META-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Jun 15;20(1):364. [CrossRef]

- Tessema ZT YL, Tesema GA, et al., (2020) Determinants of postnatal care utilization in sub-Saharan Africa: a meta and multilevel analysis of data from 36 sub-Saharan countries. Ital J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 27;46(1):175. [CrossRef]

- Birhan TY SW (2020) Trends and determinants of an acceptable antenatal care coverage in Ethiopia, evidence from 2005-2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey; Multivariate decomposition analysis. Arch Public Health.Dec 4;78(1):129. [CrossRef]

- EE. C (2020) Examining Individual- and Community-Level Factors Affecting Skilled Delivery Care among Women Who Received Adequate Antenatal Care in Ethiopia: Using Multilevel Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020 Sep 28;2020:2130585. [CrossRef]

- Ayalew TWaAMN (2017) Focused antenatal care utilization and associated factors in Debre Tabor Town, northwest Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Research Notes, 2018. 11(1): p. 819.

- Addai (1998) Demographic and sociocultural factors influencing use of maternal health services in Ghana, Afr. J. Reprod. Health, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 73–80,.

- MacLeod J, Rhode R (1998) Retrospective follow-up of maternal deaths and their associated risk factors in a rural district of Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health 3: 130-137.

- Charlotte Warren (2010) Care seeking for maternal health: challenges remain for poor women, Ethiop J Health Dev, vol. 24 Special Issue 1:100–104], no. Special issue 1, pp. 100 – 104,.

- Zelalem Ayele D, et al., (2014) Factors Affecting Utilization of Maternal Health Care Services in Kombolcha District, Eastern Hararghe Zone, Oromia Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2014. 2014: p. 917058.

- Maseresha N, Woldemichael K, Dube L (2016) Knowledge of obstetric danger signs and associated factors among pregnant women in Erer district, Somali region, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health 16: 30.

- Amenu G, Mulaw Z, Seyoum T, Bayu H (2016) Knowledge about Danger Signs of Obstetric Complications and Associated Factors among Postnatal Mothers of Mechekel District Health Centers, East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia, Scientifica 2016: 3495416.

- Doctor HV, Findley SE, Cometto G, Afenyadu GY (2013) Awareness of critical danger signs of pregnancy and delivery, preparations for delivery, and utilization of skilled birth attendants in Nigeria. J Health Care Poor Underserved 24: 152-170.

- Tura G, Afework MF, Yalew AW (2014) The effect of birth preparedness and complication readiness on skilled care use: a prospective follow-up study in Southwest Ethiopia. Reprod Health 11: 60.

- United Nations (2011) Men in families. Available online from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/family/docs/men-in-families.pdf.

- Bahilu Tewodros AGM, and Yohannes Dibaba, Factors affecting antenatal care utilization in YEM special woreda, Southwestern Ethiopia, Ethiop. J. Health Sci., vol. 19, no. 1,2009.

- Anteneh Asefa SG, Tamiru Messele,Yohannes Letamo,Endashaw Shibru. (2019) Mismatch between antenatal care attendance and institutional delivery in south Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. [CrossRef]

- Dida N BZ, Gerbaba M, (2014) Modeling the probability of giving birth at health institutions among pregnant women attending antenatal care in West Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Afr Health Sci,.

- Tsegaye B SE, Yoseph A, Tamiso A, (2021) Predictors of skilled maternal health services utilizations: A case of rural women in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16(2): e0246237. [CrossRef]

- Hagos S SD, Assegid M, et al. (2014) Utilization of institutional delivery service at Wukro and Butajera districts in the Northern and South Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 May 28;14:178. [CrossRef]

- MoFED (2010) Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) 2010/11-2014/15. The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, 2010.

- Mekonnen Y MA (2003) Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2003 Dec;21(4):374-82.

- Sundari TK (1992) The untold story: how the health care systems in developing countries contribute to maternal mortality. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(3):513-28.

- Ganatra BR CK, Rao VN. (1998) Too far, too little, too late: a community-based case-control study of maternal mortality in rural west Maharashtra, India. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(6):591-8.

| S.n | Author | Design | Results | Conclusions |

| 1 | CSA, 2000 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 26% ANC+4 = 11% ANC use in first 3 months = 5% |

|

| 2 | CSA, 2005 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 28% ANC+4 = 12% ANC use in first 3 months = 6% |

|

| 3 | Worku et al., 2022 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 93% ANC+4 = 54% ANC use in first 4 months = 61% |

|

| 4 | CSA, 2011 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 34% ANC+4 = 19% ANC use in first 4 months = 11% |

|

| 5 | EPHI, 2022 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 79% ANC+4 = 49% ANC use in first 4 months = 32% |

|

| 6 | FMOH, 2014 | HMIS | ANC once = 97% Somali region = 41.6% Tigray, Oromia, SNNP, Harari, and Dire Dawa = 100% |

|

| 7 | CSA, 2016 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 62% ANC+4 = 32% ANC use in first 4 months = 20% |

|

| 8 | CSA, 2019 | Cross-sectional | ANC once = 74 ANC+4 = 43% ANC use in first 4 months = 28% |

|

| 8 | FMOH,2014 | HMIS | ANC+4 = 70% Afar region = 46% Addis Ababa = 100% |

Showed good progress since 2010 coverage of 86% |

| 9 | UNICEF, 2022 | Estimates | ANC once = 84 ANC+4 = 68% ANC use in first 4 months = 38% |

Revealed improvement from previous estimates but huge disparity between regio |

| 10 | FMO, 2018 | HMIS | ANC once = 99% | Above target but significant regional variation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).