1. Introduction

Celiac disease (CeD) is a chronic, immune-mediated intestinal disease in genetically predisposed individuals, that is caused by the exposure to dietary gluten, i.e. a primary protein complex in wheat and other cereals (rye and barley), that is consumed in large amounts (15-20 g/day) in many areas of the world. The hallmark of active CeD is a small intestinal enteropathy characterized by villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and increased number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs). To date, the only effective treatment for CeD is a lifelong strict gluten-free diet (GFD). However, maintaining a “zero” gluten diet is difficult in real life due to the frequent contamination with traces of gluten of many food items. The persistent ingestion of gluten may cause chronic inflammation of the small intestinal mucosa and, consequently, risk of CeD-related symptoms and/or complications [

1].

As far as gluten content in food labelled as gluten-free (GF) is concerned, most countries adhere to the standards fixed by the

Codex Alimentarius, a collection of guidelines and codes of practice adopted by the Codex Alimentarius Commission, a joint commission of FAO and WHO [

2]. Since the year 2008, the

Codex Alimentarius recommendation is that food labeled as “gluten-free” contains a maximum level of 20 mg per Kg (20 parts per million = ppm) of product [

2]. This limit (also called “gluten threshold”) represents a pragmatic balance between scientific evidence and practical considerations, ensuring safety for the large majority of individuals while taking into consideration also the technical challenges of gluten detection and food production [

2]. The “20 ppm rule” has been adopted in many countries, such as USA, Canada, UK and EU [

3,

4,

5]. However, other countries worldwide set different recommendations. In Argentina, a maximum gluten level of 10 ppm in products labeled as GF is tolerated [

6]. Australia, New Zealand and Chile set even more stringent requirements, i.e. a product can be labeled as GF only if it contains no detectable gluten, while products containing up to 20 ppm of gluten are identified as “low gluten” [

7].

This heterogeneity of rules depends on a longstanding scientific debate about the maximum amount of daily gluten, if any, that can be tolerated in the GFD to avoid clinical problems and histological damage in patients affected with CeD. The purpose of this review is to critically analyze the current evidence on the gluten threshold and the toxicity of gluten traces, identify gaps in knowledge, and outline future directions aimed at optimizing the dietary management of CeD.

2. Materials and Methods

A comprehensive literature search was carried out to identify peer-reviewed articles on the tolerable amount of gluten and/or toxicity of gluten traces in the diet of patients with CeD, published in PubMed up to September 2024. Search strategies included the following key words: “celiac disease”, “gluten-free diet”, “gluten tolerance”, “gluten contamination”, “gluten threshold”. All the relevant original research articles in English, including randomized controlled trials, observational studies (prospective and retrospective) and case-reports were critically analyzed and synthesized to reflect current evidence and experts’ opinions.

3. Results

Only 9 papers fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in this review. The study-design and other features of these studies show wide variability, as summarized in

Table 1. Interestingly, most of them were published more than 15 years ago. The results of these studies will now be examined in detail to provide a comprehensive understanding of their findings and implications.

Catassi et al. firstly showed that the relationship between gluten consumption and small intestinal damage in children with CeD is dose-dependent. CeD children on long-term treatment with the GFD were administered either 100 mg or 500 mg of gliadin daily (equivalent to 200 mg and 1 g of gluten, respectively) over four weeks. After the challenge, both groups showed evidence of mucosal damage at the histological assessment, that was more pronounced in those challenged with the higher dose (500 mg of gliadin daily) [

8]. In a subsequent study performed by the same research group, treated adult CeD patients participated in a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial based on the daily ingestion of either zero (placebo), 10, or 50 mg of gluten for 90 days. Only a daily intake of 50 mg of gluten for three months caused a significant worsening of the small intestine villous height/crypt depth (Vh/Cd) ratio at the end of the challenge, as compared to placebo. However, a significant post-challenge improvement of the Vh/Cd index was observed in the placebo group (likely secondary to a “Hawthorne effect”) but not in the patients challenged with 10 of gluten. These findings suggested that the daily intake of gluten should prudentially be kept lower than 10 mg/day [

9]. Combining the results of these two studies, despite differences in the intervention (gliadin or whole gluten) and duration of the microchallenge (one or three months), it is interesting to note that a daily dose of 50, 100 and 500 mg of gliadin/gluten caused deterioration of morphometric parameters in almost all challenged subjects, while the response to 10 mg was variable at the individual level, and included all the possible outcomes (improvement, no change or deterioration of the Vh/Cd ratio and/or IELs count). These results suggested individual variability of the response to gluten when the intake is very low. Greco et al reported that a 60-day diet including baked goods made from hydrolyzed wheat flour (daily gluten intake around 500 mg) caused deterioration of the small intestinal architecture in the two CeD patients challenged with this dose, as compared with no change in the 5 challenged with 1.6 mg of gluten and the development of subtotal villous atrophy in the 6 challenged with regular bread (16 g/day of gluten) [

10].

Only the above trials evaluated the toxic effects of a precise amount of gluten given for a fixed period of time. Ciclitira et al. found no significant changes in the jejunal morphometry over a 6-week period when patients ingested 1.2 mg to 2.4 mg of gluten from bread, compared to another 6-week period in which gluten was completely excluded from their diet [

11]. In a retrospective study, Mayer et al found that the occasional intake of small amounts of gluten (60 mg-2 g/day) did not produce increased concentrations of antigliadin antibodies but resulted in an appreciably increased crypt epithelial volume and expanded crypt intraepithelial lymphocyte population [

12]. In a study involving both adults and children, Kaukinen et al. found that the consumption of non-purified wheat-starch based GF products containing 40-60 mg/100 g of gluten did not alter the integrity of the intestinal mucosa in the long-term, as compared to a diet including only naturally GF food [

13]. Laurin et al. investigated 24 children who underwent a challenge with a mean of 1.7 g/day of gluten (0.2-4.3) for a mean of 13 weeks (5-51). All children showed signs of relapse at a clinical, laboratory, or histological level, with a positive correlation between the amount of gluten intake and the IEL count in the biopsies taken post-challenge [

14]. Biagi et al. reported a case of a CeD patient in whom the ingestion of only 1 mg of gluten (with a communion host) every day for 2 years apparently prevented full histological recovery in spite of a satisfactory clinical and serological response [

15]. Finally, in a recent study, a low dose of gluten in form of “crackers” (about 60-120 mg of gluten/day) was administered for 3 months to 120 subjects already on GFD. Serological positivity was detected in 54 patients (45%), histology showed atrophy in 87% and Marsh 1-2 grade in 13% of patients [

16].

Indirect evidence of the toxicity of gluten traces derives from a retrospective study investigating the efficacy of the Gluten Contamination Elimination Diet (GCED), a restrictive diet using only rice in seeds as the only cereal source (instead of commercially available GF food containing up to 20 ppm of gluten) in patients with non-responsive CeD. Hollon et al. found that 82% of patients benefited from the GCED. Among seven patients with Marsh 3a/b mucosal lesions before starting the GCED, two achieved complete mucosal healing, and one showed normal findings on a follow-up video capsule endoscopy. However, this study did not provide any estimate of the possible amount of contaminating gluten [

17].

4. Discussion

Several studies have shown that a challenge with doses of gluten higher than 1 gram produces detectable effects on intestinal histology and other disease markers in almost all CeD patients [

14,

18,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, data on the toxicity of gluten traces are rather scanty, partially because simple CeD diagnostic markers present significant limitations to this purpose. Indeed, clinical symptoms may be completely absent [

1] while serological markers, such as the anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (anti-tTG), lack enough sensitivity to detect the exposure to low levels of dietary gluten [

22]. Histological evaluation of the small intestinal mucosa remains the gold standard method, particularly when expressed by morphometric parameters, particularly the IEL count and the Vh/Cd ratio, instead than an operator-dependent judgement such as the Marsh-Oberhuber classification [

23].

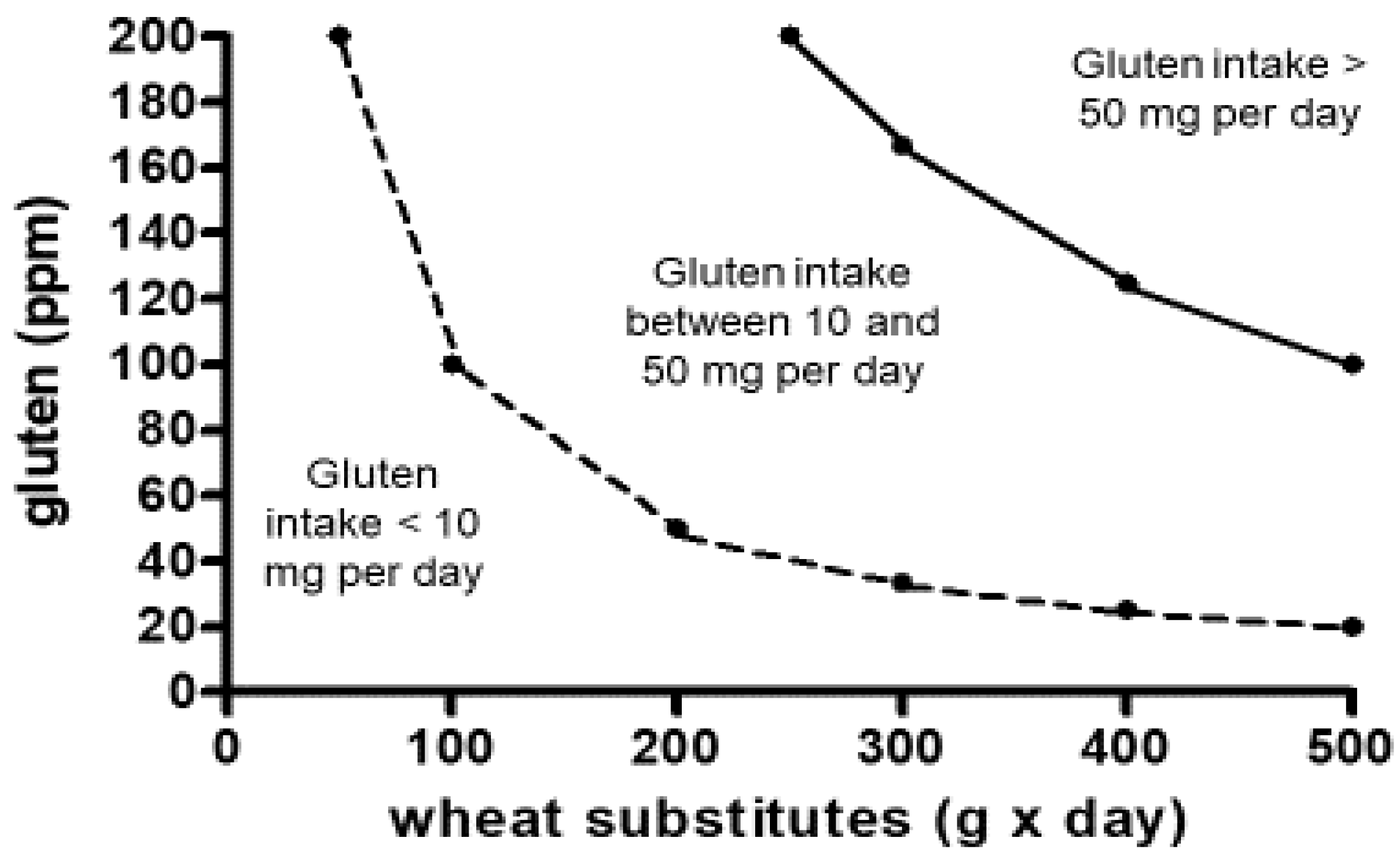

Available studies suggest that there is a linear relationship between the dose of ingested gluten and the damage of the small intestinal mucosa in CeD, at least for a gluten intake between 10 mg and 1000 g or more per day [

8,

9,

14,

21]. The threshold of 20 ppm adopted by the

Codex Alimentarius guarantees that even a high and protracted consumption of commercial gluten-free food does not overcome the gluten level (10 mg per day) that may potentially damage the architecture of the small intestinal mucosa, at least in most patients (

Figure 1) [

24].

After more than 10 years of adoption of this threshold, not a single study has definitely proven that the ingestion of gluten-free food containing less than 20 ppm of gluten may cause delay of mucosal healing after starting treatment with the GFD, or relapse of the disease in treated patients. Furthermore, in countries adopting the 20 ppm threshold for GF products, gluten contamination in labeled GF products is nowadays uncommon and usually mild on a quantitative basis. For instance, in Italy a study found that gluten level was lower than 10 ppm in 173 products (86.5%), between 10 and 20 ppm in 9 (4.5%), and higher than 20 ppm only in 18 (9%), respectively. In contaminated foodstuff (gluten > 20 ppm) the amount of gluten was almost exclusively in the range of a very low gluten content [

25].

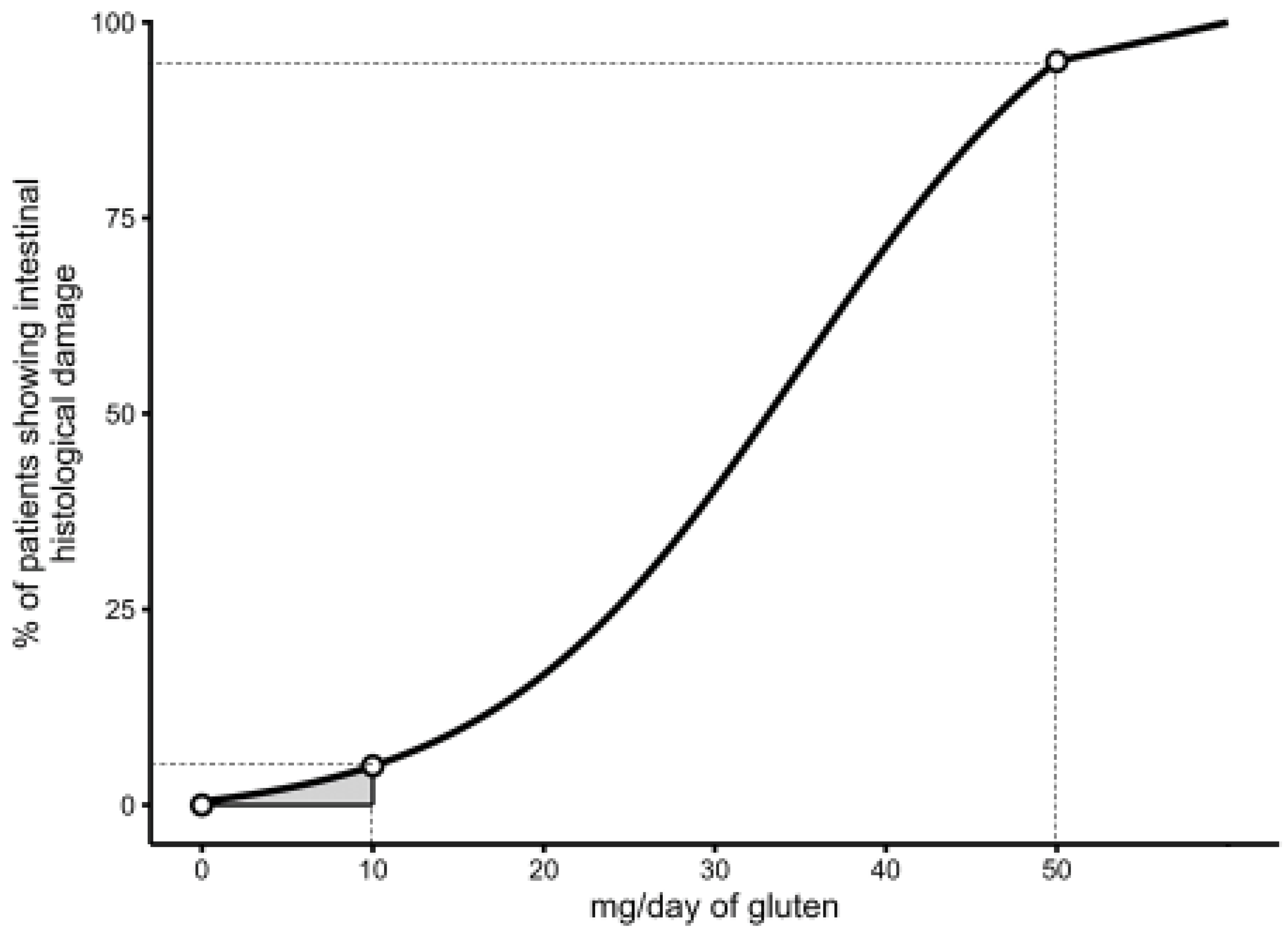

However, while there are convincing reasons to suggest that a threshold higher than 20 ppm could lead to the ingestion of an unsafe amount of gluten in a proportion of patients with CeD, the evidence that a dose of less than 10 mg of daily gluten is 100% safe for all CeD patients is weak since (a) the potential toxicity of gluten doses lower than 10 mg/day has not been evaluated in any double-blind, placebo-controlled trial so far, and (b) the sample size of available studies was too small to exclude a type II error (false negative). Should the sensitivity to gluten of CeD individuals show a Gaussian distribution from zero gluten onwards, it is well possible that a small proportion of patients may react even to minimal amounts of daily gluten (lower than 10 mg), as occasionally described in case-reports [

15] (

Figure 2).

Interestingly, the available literature shows that a consistent proportion of treated CeD patients fail to reach the complete normalization of the small intestinal architecture even after many years of treatment with the GFD [

26,

27]. It is not clear whether this finding depends on unreported transgressions to the GFD or “hypersensitivity” to traces of gluten that may be ingested with a nominally GFD.

It is important to note that also the evaluation of intestinal histology as an index of gluten-induced damage shows potential drawbacks: (a) it is an invasive procedure (upper endoscopy) to be performed before and after the gluten challenge; (b) it requires a prolonged, potentially harmful, exposure to gluten (at least 4-8 weeks), (c) it may be misleading due to a patchy distribution of the damage or poor orientation of the biopsy specimen [

1,

28]. New methods of investigating gluten toxicity in a quantitative manner have recently shown interesting results. Biopsy proteome scoring is a reliable measure of gluten-induced mucosal remodeling that may replace conventional histology in the evaluation of an oral gluten challenge [

29]. Even more promising is the measurement of serum interleukin (IL)-2 after an “acute” challenge with gluten [

30]. Leonard and coworkers recently investigated the performance of IL-2 measurement after a 14-days gluten challenge with either 3 or 10g of daily gluten, and found that this assay was more sensitive than intestinal histology to detect CeD reactivation at the lower dose of gluten (3 g/day) [

31]. This procedure could facilitate the investigation of the potential toxicity of traces of gluten, also in the range of 1-10 mg of gluten.

5. Conclusions

The available literature indicates that the current Codex Alimentarius “20ppm” rule, as the maximum tolerable level of gluten in gluten-free food, is evidence-based and safe for most patients. However it remains to be elucidated whether very low traces of gluten, in the range of up to 10 mg, may still be harmful for a subset of CeD patients. In the near future the application of new techniques of gluten toxicity analysis, such as the single-dose gluten challenge with subsequent quantification of serum IL-2, could help to clarify whether the current “20 ppm” rule for gluten-free food is the best choice or might be time to consider further reduction of gluten content in food item commercially available for treatment of CeD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; methodology, C.M. and C.C..; formal analysis, C.M. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, C.C., C.M., G.C. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

we thank Dr. Loris Naspi for drawing

Figure 2.

Conflicts of Interest

C.C. is scientific consultant for Dr. Schaer Food. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CeD |

Celiac Disease |

| GF |

Gluten Free |

| GFD |

Gluten Free Diet |

| FAO |

Food Agricolture Organization |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| Vh/Cd |

Villous Height/Crypt depth |

| IEL |

Intra Epithelial Lymphocyte |

| GCED |

Gluten Contamination Elimination Diet |

| Il-2 |

Interleukin-2 |

References

- Catassi, C.; Verdu, E.; Bai, J.; Lionetti, E. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2022, 399, 2413–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius. Standard for foods for special dietary use for persons intolerant to gluten. CXS 118-1979. Adopted in 1979. Amended in 1983 and 2015. Revised in 2008.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2013). Food Labeling; Glutenfree Labeling of Foods (Document Number 2013-18813). Federal Register, Available online: https://federalregister.gov/a/2013-18813.

- Health Canada. (2014). Foods for Special Dietary Use (Division 24). Food and Drug Regulations, Available online. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._870/FullText.html.

- Commision Implementing Regulation (EU) No 828/2014 on the Requirements for the Provision of Information to Consumers on the Absence or Reduced Presence of Gluten in Food. 30 July 2014. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2014/828/oj.

- Argentina Codigo Alimentario Argentino—Resolución Conjunta 131/2011 y 414/2011. [(accessed on 25 April 2022)]. Available online: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/normativa/nacional/resoluci%C3%B3n-131-2011-184719.

- Australia New Zealand Food Authority. (2012). Nutrition Information Requirements (Standard 1.2.8) Food Standards Code. Retrieved from. http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2013C00098.

- Catassi, C.; Rossini, M.; Rätsch, I.M.; Bearzi, I.; Santinelli, A.; Castagnani, R.; Pisani, E.; Coppa, G.V.; Giorgi, P.L. Dose-dependent effects of protracted ingestion of small amounts of gliadin in children with coeliac disease: a clinical and jejunal morphometric study. Gut 1993, 34, 1515–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catassi, C.; Fabiani, E.; Iacono, G.; D’Agate, C.; Francavilla, R.; Biagi, F.; Volta, U.; Accomando, S.; Picarelli, A.; De Vitis, I.; Pianelli, G.; Gesuita; Carle, F. ; Mandolesi, A.; Bearzi, I.; Fasano, A. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to establish a safe gluten threshold for patients with celiac disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 85, 160–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, L.; Gobbetti, M.; Auricchio, R.; Di Mase, R.; Landolfo, F.; Paparo, F.; Di Cagno, R.; De Angelis, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Cassone, A.; Terrone, G.; Timpone, L.; D’Aniello, M.; Maglio, M.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, S. Safety for patients with celiac disease of baked goods made of wheat flour hydrolyzed during food processing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 9, 24–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciclitira, P.J.; Cerio, R.; Ellis, H.J.; Maxton, D.; Nelufer, J.M.; Macartney, J.M. Evaluation of a gliadin-containing gluten-free product in coeliac patients. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr 1985, 39, 303–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M. , Greco L., Troncone R., Auricchio S., Marsh M.N. Compliance of adolescents with coeliac disease with a gluten free diet. Gut 1991, 32, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukinen, K.; Collin, P.; Holm, K.; Rantala, I.; Vuolteenaho, N.; Reunala, T.; Mäki, M. Wheat starch-containing gluten-free flour products in the treatment of coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis. A long-term follow-up study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999, 34, 163–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurin, P.; Wolving, M.; Fälth-Magnusson, K. Even small amounts of gluten cause relapse in children with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2002, 34, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, F.; Campanella, J.; Martucci, S.; Pezzimenti, D. , Ciclitira, P.J.; Hellis, H.J.; Corazza, G.R. A milligram of gluten a day keeps the mucosal recovery away: a case report. Nutr Rev 2004, 62, 360–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispo, A.; Guarino, A.D.; Siniscalchi, M.; Imperatore, N.; Santonicola, A.; Ricciolino, S.; de Sire, R.; Toro, B.; Cantisani, N.M.; Ciacci, C. “The crackers challenge”: A reassuring low-dose gluten challenge in adults on gluten-free diet without proper diagnosis of coeliac disease. Dig Liver Dis 2024, 56, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollon, J.R.; Cureton, P.A.; Martin, M.L.; Martin, M.L.; Puppa, E.L.; Fasano, A. Trace gluten contamination may play a role in mucosal and clinical recovery in a subgroup of diet-adherent non-responsive celiac disease patients. BMC Gastroenterol 2013, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyle, G.G.; Paaso, B.; Anderson, B.E.; Allen, D.; Marti, T.; Khosla, C.; Gray, G.M. Low-dose gluten challenge in celiac sprue: malabsorptive and antibody responses. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005, 3, 679–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartee, A.K.; Choung, R.S.; King, K.S.; Wang, S.; Dzuris, J.L.; Anderson, R.P.; Van Dyke, C.T.; Hinson, C.A.; Marietta, E.; Katzka, D.A.; Nehra, V.; Grover, M.; Murray, J.A. Plasma IL-2 and Symptoms Response after Acute Gluten Exposure in Subjects With Celiac Disease or Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol 2022, 117, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaanse, M.P.; Leffler, D.A.; Kelly, C.P.; Schuppan, D.; Najarian, R.M.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Buurman, W.A.; Vreugdenhil, A.C. Serum I-FABP Detects Gluten Responsiveness in Adult Celiac Disease Patients on a Short-Term Gluten Challenge. Am J Gastroenterol 2016, 111, 1014–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami-Nejad, M.; Asri, N.; Olfatifar, M.; Khorsand, B.; Houri, H.; Rostami, K. Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis on the Relationship between Different Gluten Doses and Risk of Coeliac Disease Relapse. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.A.; Kurada, S.; Szwajcer, A.; Kelly, C.P. , Leffler, D.A.; Duerksen, D.R. Tests for Serum Transglutaminase and Endomysial Antibodies Do Not Detect Most Patients With Celiac Disease and Persistent Villous Atrophy on Gluten-free Diets: a Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Gahlot, G.P.; Singh, A.; Baloda, V.; Rawat, R.; Verma, A.K.; Khanna, G.; Roy, M.; George, A.; Singh, A.; Nalwa, A.; Ramteke, P.; Yadav, R.; Ahuja, V.; Sreenivas, V.; Gupta, S.D.; Makharia, G.K. Quantitative histology-based classification system for assessment of the intestinal mucosal histological changes in patients with celiac disease. Intest Res 2019, 17, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, A.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Neuhold, S. , Houben, G.F.; Canela, M.A.; Fasano, A.; Catassi, C. Might gluten traces in wheat substitutes pose a risk in patients with celiac disease? A population-based probabilistic approach to risk estimation. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 97, 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Gatti, S.; Galeazzi, T.; Monachesi, C. , Padella, L.; Baldo, G.D.; Annibali, R.; Lionetti, E., Catassi C. Gluten Contamination in Naturally or Labeled Gluten-Free Products Marketed in Italy. Nutrients 2017, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, A.; Lanzarotto, F.; Villanacci, V.; Mora, A.; Bertolazzi, S. , Turini, D.; Carella, G.; Malagoli, A.; Ferrante, G.; Cesana, B.M.; Ricci, C. Complete recovery of intestinal mucosa occurs very rarely in adult coeliac patients despite adherence to gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009, 29, 1299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardella MT, Velio P, Cesana BM, et al. Coeliac disease: a histological follow-up study. Histopathology 2007, 50, 465–71.

- Ravelli, A.; Villanacci, V. Tricks of the trade: How to avoid histological pitfalls in celiac disease. Pathol Res Pract 2012, 208, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, A.; Sandve, G.K.F.; Maxwell, J.R.; Smithson, G., Sollid, L.M.; Stamnaes, J. Biopsy Proteome Score Performs Well as an Effect Measure in a Gluten Challenge Trial of Celiac Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024: S1542-3565(24)00771-7.

- ye-Din JA, Daveson AJM, Ee HC, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-2 after gluten correlates with symptoms and is a potential diagnostic biomarker for coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019, 50, 901–910.

- Leonard MM, Silvester JA, Leffler D, et al. Evaluating Responses to Gluten Challenge: A Randomized, Double-Blind, 2-Dose Gluten Challenge Trial. Gastroenterology. 2021, 160, 720–733.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).