1. Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide. One remarkable characteristic of cancer cells is their enormous flexibility in terms of modulating metabolism and adaptation to various nutrients and other factors that can potentially impact their growth and existence [

1]. Because of this unique flexibility, cancer cells can ‘adapt and conquer’ [

2] i.e. they not only can survive but can thrive and make otherwise ‘unfavorable’ conditions favorable. This ‘flexibility’ involves changes in their gene expression, and more importantly in their phenotype, and affords cancer cells their ‘plasticity’. The metabolic adaptability and plasticity of cancer cells is frequently the reason for frustration associated with therapeutic interventions. One important phenomenon in this respect is the stemness of cancer cells [

3]. A stem cell is known for its ability to reproduce cells of its kind, known as self-renewal or to differentiate into specialized cells [

4]. In cancer, the cancer stem cells possesses an unlimited capability to multiply and, in addition, they contribute to resistance against therapy, the relapse of tumor, as well as cancer metastasis [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The phenomenon of stem cell plasticity can be understood as a build-up on this basic foundation: stem cell plasticity could be defined as the differentiation of stem cells to any cell type if removed from their original location. Stem cell plasticity was first noted in their embryological origin [

12], but later evidence showed that stem cells can differentiate into cells of different germ layers [

13]. While plasticity is a natural characteristic of stem cells which is crucial during embryonic development, transdifferentiation pertains to a similar property in adulthood. Transdifferentiation entails the irreversible switching of cells from a particular tissue lineage into cells of an entirely different lineage, leading to the complete loss of the original cell type's tissue-specific markers and functions. Instead, the cells acquire the markers and functions associated with the new cell type.

Stem cell plasticity can be witnessed at work largely in tissue repair [

4]. It allows for the regeneration of tissues in scenarios where regeneration has failed to provide optimal results. For example, the replacement of the infected tissue in post-myocardial infarction patients with cardiomyocytes or skeletal myoblasts has been limited [

14]. Although it may have been successful in engraftment, it did not show optimal recovery of the myocardium and coronary vessels. However, bone marrow cells injected into damaged myocardium produced endothelial cells and smooth cells, resulting in angiogenesis and improved ventricular function. Another study supported this idea with the experiment on bone marrow stem cells in the regeneration of oval cells [

15]. By performing bone marrow transplantation in mice models followed by partial hepatectomy, it was observed that the oval cells found in the liver were bone marrow-derived which demonstrated stem cell plasticity’s role in tissue repair. In addition to being critically important for tissue repair following injury, cellular plasticity is relevant to cancer as it contributes to tumor heterogeneity [

16]. Thus, apart from its adaptation in normal physiological roles, stem cell plasticity has been shown to exert its role in tumorigenesis [

17]. It not only leads to tumor formation and metastasis but also plays a role in the resistance against therapy. [

18] For instance, Ewing sarcoma cells can undergo plasticity to give rise to endothelial cells that contribute to vasculogenesis and a more aggressive form of cancer, and in breast cancer, breast cancer stem cells transition between two states, mesenchymal-like and epithelial-like to continue invasion, metastasis, and growth [

19], thus exemplifying plasticity.

In terms of therapy resistance, cancer cell plasticity can allow cancer cells to develop resistance against multiple therapies and escape apoptosis [

20,

21,

22]. This concept is evident in the switching between two cell states in response to therapies in colon cancer [

23]. These tumor cells undergo self-renewal in the LGR (Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor)-5+ state. However, upon exposure to irinotecan, the cells undergo a quiescent state (LGR5-) with the ability to revert back to a LGR5+ state in the absence of the drug. Another study by Wang et al. [

24] showed that when patients with urothelial cancer are treated with a PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab, the cells with low response rate and shorter survival were observed to have high EMT/stroma-related gene expression. It was further observed that stromal cells played a major role in EMT gene expression. This evidence supports the adaptive ability of cancer stem cells to undergo differentiation to combat the effects of therapy.

2. Mechanisms of Cancer Cell Plasticity

To understand how cancer cells exhibit resistance to drugs, it is vital to identify the different underlying mechanisms through which stem cell plasticity helps achieve therapeutic resistance. One way tumor cells adapt to their environment is by the process of EMT (epithelial-mesenchymal transition) [

25,

26]. Another attributing mechanism is transient drug-induced tolerance which requires the cells to undergo a slow drug-resistant phase before a final multidrug resistance. Amongst others, transdifferentiation, a subtype of cellular reprogramming, also plays a major role in developing resistance towards drugs [

25,

27].

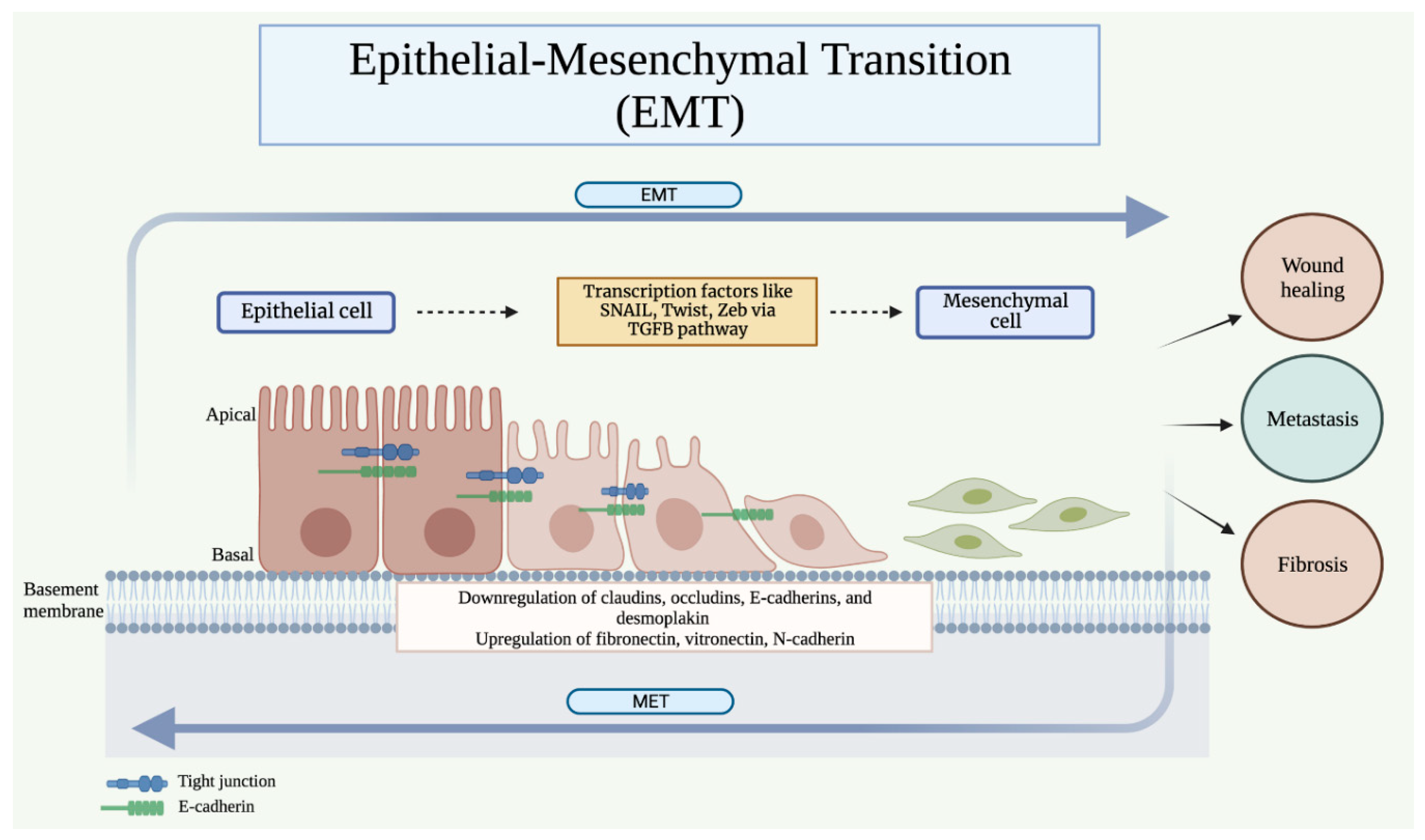

2.1. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

EMT is a dynamic mechanism that involves loss of epithelial cell-cell junction and actin cytoskeleton reorganization [

28] (

Figure 1). The epithelial cells have inherent plasticity, which enables them to transition into mesenchymal cells [

29]. EMT is a spectrum of biological processes that are reversible. Rather than transforming from a full epithelial state to a full mesenchymal state, the cells dynamically transition to an intermediate phase. A shift in the opposite direction, known as a mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) may also be observed [

30]. EMT confers more mobility in the cell and makes them invasive [

31,

32,

33]. The change in cell differentiation during EMT is mediated by transcription factors such as SNAIL, zinc-finger E-box-binding (ZEB), and basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) [

34]. They repress epithelial marker genes such as claudins, occludins, E-cadherins, desmoplakin, plakophilin, etc., and cause activation of genes such as fibronectin, vitronectin, N-cadherin, MMPs, etc. which are associated with the mesenchymal phenotype [

35,

36]. This change in gene expression during EMT is initiated and controlled by pathways activated in response to extracellular signals, the most predominant of which is the TGFβ signaling pathway [

34,

37].

EMT plays a significant role during the embryonic developmental period and is integral to embryonic stem cell differentiation. It is also observed pathologically, during wound healing, fibrosis, and cancer progression [

38]. During embryogenesis, EMT is required for the production of primary mesenchymal cells that are successively capable of producing secondary epithelia via MET [

39]. During wound healing and fibrosis, epithelial cells transition into fibroblast-like cells containing both epithelial cell markers as well as mesenchymal markers [

39]. They help rebuild the tissue following trauma or inflammation. The process of EMT is terminated once the repair is completed or inflammation is reduced [

39]. In the tumor cells, it is suggested that EMT causes them to lose their cell-cell junctions, apical-basal polarity, and adherence to the basement membrane [

40]. They acquire characteristics of the mesenchymal cells allowing them to migrate and become invasive. Histopathological analysis has shown the invasive front of the tumor to exhibit an EMT phenotype [

35,

41,

42,

43]. Thus, EMT promotes the dissemination of tumor cells into the systemic circulation and enhances the process via EMT-induced angiogenesis [

44]. However, it is to be noted that EMT phenotypes are not preferentially disseminated, as both epithelial and mesenchymal cells have been found in the peripheral circulation [

45]. Researchers have also demonstrated the association of EMT transcription factors (TFs) such as TWIST1 with the acquisition of stem cell properties and enhanced metastasis [

46,

47].

For metastasis, cancer cells are required to cross the endothelial cell barrier, enter into circulation (intravasation), and exit the circulation into distant tissues (extravasation) [

48]. While sufficient experimental evidence is not present to determine if EMT enhances the transendothelial migration of tumor cells, studies have found circulating tumor cells (CTCs) to exhibit EMT TFs [

49,

50]. Studies have also shown that CTCs exist in different states including epithelial and mesenchymal, and also exhibit characteristics of both epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes [

51,

52]. However, it may also be suggested that the CTCs undergo EMT in the peripheral circulation which is rich in TGFβ [

40]. Some studies also attribute extravasation and initial colonization of distant sites to EMT [

53].

2.2. Dedifferentiation and Transdifferentiation

Dedifferentiation of tumor cells and acquisition of stem cell-like traits increases the likelihood of the cancer metastasis to different organs, contributing to increased therapeutic resistance. A study by Malta et al. [

54] employed a machine learning algorithm for the assessment of tumor dedifferentiation through integrated analysis of cancer stemness in almost 12,000 primary human tumors of 33 different cancer types. The cells were either known to arise from progenitor cells themselves or other non-stem cells with dysregulated pathways. Metastasizing tumors were generally observed to express a more dedifferentiated phenotype, which was associated with high intratumor heterogeneity. The study also identified changes in key features such as the upregulation of progenitor genes and downregulation of differentiation and cell adhesion. Certain transcription factors such as SOX2 and NANOG externally play a role in dedifferentiation. NANOG is a regulatory protein found in pluripotent cells and is found to drive differentiated cells like astrocytes [

55] into brain cancer stem cells in the absence of p53. Moreover, another study on colorectal cancer observed TGF-β acting as an external stimulator to induce the TWIST1 gene into converting non-CSC CD44- to undifferentiated CD44+ CSC [

56].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) possess the capability to undergo transdifferentiation, transforming into cells of diverse lineages, typically via an intermediate dedifferentiation step. This process can result in either a reduction of the tumor's aggressiveness or the formation of structures that support the tumor's growth and proliferation. The transdifferentiation of CSCs presents a promising therapeutic approach, as their ability to transdifferentiate can be strategically employed to induce their differentiation into terminally differentiated cells, thereby eliminating the tumor's capacity for self-renewal. Accumulating evidence across various cancers underscores the potential of transdifferentiation-based therapies utilizing this strategy.

2.3. Epigenetics of Cancer Cell Plasticity

Dysregulation of epigenetic regulation plays a key role in cancers, leading to enhanced cancer cell plasticity, inducing carcinogenesis and metastases, and increasing chemoresistance (

Figure 2). Widespread alterations of chromatin conformation and associated epigenetic changes can confer on cancer cells the full range of oncogenic properties typically known as the ‘hallmarks of cancer’ [

57]. Chromatin can be permissive or restrictive, based on the epigenetic events such as DNA methylation, histone modifications (methylation and acetylation), and chromatin remodelling (SWI/SNF complex) that can open certain areas for active transcription while restricting others, blocking cellular differentiation or dysregulating cell programming, respectively. In cancer stem cells, bivalent chromatin (which possesses both permissive and repressive histone modifications) allows the cancer cell to retain its cell reprogramming ability and phenotypic plasticity, facilitating further growth and migration of the tumor.

Hypermethylation of the CpG islands associated with tumor suppressor genes and hypo-methylation of oncogenes in cancer has been reported in a number of studies. Frequent hypermethylation is observed in the promoter sequences of tumor suppressor genes p16INK4a (CDKN2A) and p15INK4a (CDKN2B), which regulate the cell cycle, in a variety of cancers [

58]. Silencing of genes involved in cell adhesion, CDH1 (E-cadherin), CDH2 (N-cadherin) and CDH13 (H-cadherin) via promoter methylation is also implicated in proliferation and metastasis of the tumor [

59]. The expression of DAPK1, which participates in apoptotic cell death, and its related transcription factors is downregulated through DNA hypermethylation [

60]. Hypomethylation of oncogenes, on the other hand, is frequently reported in the activation of HIF-1α and BCL2 [

61,

62].

The CTCF insulator protein plays a key role in creating chromatin loops and domain boundaries and is highly sensitive to methylation. Hypermethylation of CTCF in IDH mutant gliomas leads to loss-of-function at chromatin domain boundaries, dysregulating the interaction of a constitutive enhancer with the well-known glioma oncogene, the platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) [

63]. This drives oncogenic PDGFRA overexpression and is yet another example of epigenetically-driven plasticity with a direct effect on tumor progression.

2.3.1. Epigenetic Regulation of Genes Associated with EMT

EMT plays a significant role in cancer cell plasticity and is mediated by the epigenetic regulators of genes, including genes implicated in cell adhesion, genes for transcription factors, and pluripotency inducer genes. The CDH1 gene encodes E-cadherin, an adherens junction protein that maintains the stemness of cells in the epithelial state and prevents cell transition to the mesenchymal migratory state, thus acting as a tumor suppressor gene. Epigenetic regulation of CDH1 leading to E-cadherin downregulation is a key step for initiating EMT and causing the detachment of cells from the bulk tumor. Cooperative functioning of transcription factors such as SNAIL, zinc-finger E-box-binding homeobox (ZEB) and TWIST with others (HOXB7, FOX, SOX) plays an important role in the regulation of CDH1 expression. Activation of SNAI1 and SNAI2 through ERK pathway is implicated in the repression of CDH1 [

64], as well as other genes involved in tight junctions (occludin and claudin 1). In hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, SNAI2 upregulation enhanced H3K9 methylation and downregulated H3K4 and H3K56 acetylation in CDH1 promoters [

65]. Additionally, this SNAI2 upregulation also interacted with G9a and HDACs to suppress E-cadherin transcription, resulting in migration and invasion. ZEB1 (Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1) blocks the expression of the interleukin-2 gene and inhibits the CDH1 promoter, inducing EMT via recruiting SMARCA4/BRG1 [

66]. Moreover, ZEB1 recruits the histone deacetylase HDAC1 or the methyltransferase DNMT1 to the CDH1 promoter, thereby maintaining the hypermethylation status of the CDH1 gene and inhibiting its transcription. The HOXB7 protein, encoded from the human HOXB cluster, is believed to mediate CDH1 expression via promoter hypermethylation of CDH1 [

67]. It has been postulated this may occur through an indirect mechanism via the up-regulation of DNMT3B mediated by miR-152, which then controls DNA methylation of the CDH1 promoter [

67,

68,

69]. Transcription factor Forkhead Box protein A1 (FOXA2) was found to coordinate with the transcriptional coactivator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α) in suppressing TWIST1-mediated EMT, through regulating the expression of cadherin proteins E-cadherin (CDH1) and N-cadherin (CDH2) [

70].

The pluripotency inducer genes, SOX2 and NANOG, and their crosstalk with several oncogenic signaling pathways is linked to the regulation of EMT. Overexpression of SOX2 – a crucial embryonic stem cell (ESC) gene which mediates EMT via inducing β-catenin – is linked to cellular migration, tumor metastasis, and increased chemo-resistance of cancer cells [

71]. Chromatin modifications, where histone is altered by methylation and acetylation, are crucial for the epigenetic regulation of SOX2 expression. Findings by Kar et al. indicate the overexpression of SOX2 in cancer is mainly controlled by active histone 3 methylation (H3K4me3) and adjacent acetylation-phosphorylation (H3K9acS10p) marks [

72]. In prostate cancer clinical samples, high levels of methylation of the SOX2 promoter were found to be linked to high-grade prostate cancer [

73]. Moreover, the upregulation of NANOG has also been implicated in the reprogramming of normal cells into stem-like cancer cells. In embryonic stem cells, significant hypermethylation was reported at the sites where NANOG binds. The speckle-type POZ protein (SPOP) was implicated in the degradation of NANOG via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), inhibiting the self-renewal and stem-like traits of prostate cancer cells [

74].

3. Cell Plasticity and Therapy Resistance

Cancer cells can build resistance to therapies due to their plasticity (

Figure 3). Whether by manifesting senescence or pathways like autophagy, cells undergo metabolic adaptations to undergo resistance to treatment [

75,

76]. In terms of epigenetics, stem cells adopt resistance by modifying DNA promoter regions, methylating histone protein, or deregulated acetylation [

77,

78,

79]. ATM gene, known to repair DNA double-strand breaks is known to be activated by radiation, chemotherapy, and stress [

80]. Somatic mutations in these genes allow tumor cells to be resistant to chemotherapeutic agents. Another way tumor cells establish resistance is by the efflux pumps. The ability to efflux the drug at a high rate can be acquired post-therapy or can be an internal feature of the tumor [

81]. ABC transporters are proteins known to pump toxins out of cells. Their use in tumor cells has allowed them to resist drugs like methotrexate [

82]. It has also been reported that drug-metabolizing enzymes in Phase I (which catalyze oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis reactions of drugs) and Phase II (catalyzing conjugation reactions of drugs) play a significant role in chemoresistance. One such enzyme that was seen elevated in sarcoma cell lines was aldehyde dehydrogenase [

83]. Its expression was also elevated in prostate cancer cells post-radiotherapy [

84]. CSCs develop resistance by deregulating apoptosis [

85]. The process of resistance is highly dependent on the balance of apoptotic and anti-apoptotic protein expression. For instance, a study by Taniai et al. [

86] revealed that cholangiocarcinoma cells treated with TNF-apoptosis-inducing ligand showed resistance to this treatment. Upon analysis, these cells expressed high levels of anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-xl and Mcl-1. It is essential to know that cells can change in many ways, whether it is receptor-based or modifications in gene expression. Understanding these mechanisms will allow targeting specific processes to overcome the ongoing adaptations towards resistance.

3.1. Reduced Susceptibility to Apoptosis

The upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes and downregulation of apoptotic genes in cancer cells is associated with increased chemoresistance. In their study, Wu et al. established an association between the loss of the apoptotic tumor repressor gene, FHIT (fragile histidine triad), and cisplatin resistance in NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer) [

87]. FHIT loss-of-function can induce EMT and activate the AKT signaling pathway, causing upregulation of Slug transcription. This induces a decrease in PUMA expression which is responsible for cisplatin resistance.

The inhibition of apoptotic signaling pathways is another mechanism for chemoresistance. In a study by Lu et al., it was found that the loss of E-cadherin during EMT results in selective attenuation of the apoptotic signaling via the death receptors, DR4 and DR5 [

88]. Since TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) mediates its effects via these receptors, carcinoma cells become resistant to TNF-induced apoptosis.

Another pathway that suppresses apoptosis of cancer cells is the survivin pathway. Rhodes et al. [

89] investigated the survivin pathway in dedifferentiation of NSLC models that received radiation and were found to undergo plasticity. When NSCLC cells were treated with a survivin inhibitor, the CSCs were found to be more radiosensitive. Survivin was also found to enhance radiation resistance in glioblastoma multiform cell lines [

90]. The survivin pathway is an anti-apoptotic protein associated with tumorigenesis, therapeutic resistance, and poor prognosis [

91,

92,

93]. It can be activated by multiple factors such as microRNAs, tyrosine kinases, PI3K/Akt and STAT pathways. It plays a role in tumorigenesis by interacting with cascades, regulating cell cycle and p53 amongst many signaling pathways. In another study on GBM cell lines [

90], radioresistant cells had higher expression of survivin and significant double-stranded DNA repair. Moreover, these cells were also found to have elevated intracellular accumulation of ATP. This suggests that by regulating tumor metabolism and DNA repair, survivin produces a radioresistant phenotype cell in multiple tumors, including GBM.

3.2. Immune Evasion

The evasion of cytotoxic T-cells by carcinoma cells is facilitated by elevated levels of PD-L1 (programmed cell death ligand 1) and TSP-1 during EMT [

94,

95]. PD-L1 binds to inhibitory programmed cell death protein (PD-1) receptors on the cytotoxic T cell, which decreases the function of the cytotoxic T- cells. TSP-1 (thrombospondin-1) secreted during EMT promotes the development of regulatory T-cells within the tumor masses and results in decreased function of cytotoxic T-cells. Thus, most anti-cancer therapies only eliminate the non-CSCs while the CSCs are left behind. Due to their tumor-initiating potential, these cells are then able to give rise to new tumor masses, ultimately leading to clinical relapse [

96].

A study on a metastatic melanoma patient proved cytokine-induced plasticity [

97]. When melanoma cells were treated with ACT (adaptive T-cell therapy), they were found to undergo de-differentiation to neural crest origin. The T-cell therapy was directed toward MART-1 antigen; there was a decrease in the expression of MART-1 and gp-100, tumor antigens associated with melanoma [

98,

99]. This indicated that a switch in phenotype has occurred. It was also observed that cells, later on, expressed NGFR [

100], a CSC marker, which supported the de-differentiation of melanoma cells to neural crest origin. Moreover, the dedifferentiation was proven to be mediated by TNFα as cells treated with TNFα were noted to have decreased expression of the MART-1 antigen and upregulation of nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR). When TNFα was withdrawn, cells were marked by lower NFGR and higher MART-1 expression. This concludes that inflammation-induced de-differentiation is reversible and persistent TNFα is needed to continue this state. This identifies TNFα as a prospective target to overcome the resistance.

3.3. Epigenetic Targets

In terms of epigenetic mechanisms that drive chemoresistance, it was revealed that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a major role in the process (

Figure 4). Wnt is a protein that binds to transmembrane receptors, FZA (frizzled) and LPR5/6, activating the β-catenin protein [

101]. β-catenin allows cell-to-cell contact and regulates chromatin modification [

20,

102]. In cancer, it has been found to regulate stemness [

103,

104]. It has been reported that lymphoma cells treated with cyclophosphamide can renter the cell cycle with higher expression of Wnt genes [

105], and that in colon cancer, mutated APC gene interacts with MEK inhibitors to enhance Wnt activity and maintain the stemness of CSCs [

106]. Targeting the Wnt pathway, thus, can be an excellent epigenetic approach to overcome dedifferentiation. Ipafricept, a decoy receptor for Wnt ligands has proved to be well tolerated and reduces the frequency of CSCs for advanced solid tumors, as revealed in results from a phase 1 study [

107].

An in vitro study by Kim et al. reported widespread epigenetic changes to occur in the global chromatin landscape of melanoma cells exposed to IFN-γ, as the cells underwent dedifferentiation. The IFN-γ-mediated epigenetic signature in the study correlated with a better outcome of melanoma patients in clinics. Such observations also support the idea of targeting 3D chromatin architecture for re-sensitizing tumor cells to therapies [

108]. The epigenetic regulation of the process of dedifferentiation is also being evaluated with the role of methylation, and signaling through β-catenin in dedifferentiation as relevant to aggressive adrenocortical carcinoma [

109]. While the more concrete experimental evidence is emerging slowly, the involvement of epigenetic events and their role in dedifferentiation of cancer cells has been around for some time [

110,

111]. The emergence of specific epigenetic targets represents a promising therapeutic approach for the treatment of drug-resistant tumors.

3.4. Efflux of Drugs

A number of studies have noted the role drug efflux as a chemoresistance mechanisms in cancers. Vecchio et al. [

112] studied the effects of artificially de-differentiated cells' therapeutic resistance to paclitaxel and doxorubicin and observed a role of Twist [

47], a transcriptional regulator. These cells were found to have increased efflux activity and decreased ROS levels, both indicative of highly resistant cell nature. Moreover, Saxena et al. in their study established that induction of EMT increases the expression of multiple ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC transporters), increasing the efflux of drugs and making the cells drug-resistant [

113]. Similarly, Fung et al. noted increased expression of the hepatic oncofetal protein in hepatocellular carcinoma, where the ABC transporter was found to mediate EMT via the EMT inducers HIF1α/IL8 and Sox4, as well as regulate cancer stemness properties and increase chemoresistance and drug efflux [

114]. These findings highlight the potential of transporter proteins involved in drug efflux, such as ABC transporters, as novel therapeutic targets for cancers.

3.5. Alteration of Drug Targets

Epigenetic drugs like valproic acid function as HDAC inhibitors to allow tumor cells to undergo pluripotency and render them resistant to taxol [

115]. Treatment of breast cancer cells with valproic acid was observed to result in high aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity, a feature of a drug-resistant state. This also indicated the phenotypic state of change in cells. These cells had an upregulation of vimentin, and fibronectin, markers for EMT induction. The cells staying in G0/G1 phase further proved that CSCs underwent de-differentiation rather than proliferation.

4. Targeting Cancer Plasticity for Therapy

4.1. Therapy Targeting the Phenomenon of EMT

As discussed above, EMT promotes the metastatic potential of tumor cells and makes them resistant to existing therapeutic modalities. Thus, therapies that are aimed at either preventing or eliminating cells undergoing EMT must be developed and used along with anti-tumor therapies. One of the major pathways responsible for EMT initiation is the TGFβ pathway. Morris, et al. [

116] in their study on patients with malignant melanoma and renal cell carcinoma, found that Fresolimumab, a human anti-TGF-b monoclonal antibody, can provide an acceptable level of safety with preliminary evidence of anti-tumor activity. However, adverse effects such as the development of reversible keratoacanthomas and hyperkeratosis were also observed. The Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-HGF receptor (HGFR) signaling pathway has also been known to initiate EMT. It uses tyrosine kinase Met as its receptor to promote tumor invasion and metastasis in cells [

117]. Two drugs that inhibit this signaling pathway have now been approved by the FDA: crizotinib in the treatment of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), and cabozantinib for the treatment of medullary thyroid cancer and renal cell carcinomas [

96]. Douillard et al. [

118] assessed the efficacy and safety of gefitinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR TKI) in patients with EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC. First-line Gefitinib was found to be effective and well tolerated, offering longer progression-free survival and better quality of life as compared to first-line chemotherapy. However, in a study aimed at disrupting N-cadherin adhesion complexes for increasing the sensitivity of anti-tumor drug melphalan in the treatment of advanced extremity melanoma, no difference in response to treatment was observed [

119]. Several other drugs targeting EMT effectors and receptors are at different stages of clinical trials and have shown promising results. However, targeting effectors and receptors may be a difficult task because of the transient nature of the different phases of cells undergoing EMT, and the redundant nature of various EMT pathways [

120]. In contrast, therapies targeting EMT TFs such as SNAIL, ZEB, bHLH, TWIST, etc. could be more effective by having a broader effect, albeit it is conceivable that the effects might be a little too broad, with implications even in the normal functioning of body. Thus, there is need for a better fine tunning. Since EMT is mainly implicated in tumor cell metastasis and drug resistance and does not influence tumor cell proliferation and survival, it is judicious to utilize EMT inhibitors in conjugation with other established anti-tumor drugs rather than as a single first-line agent [

121].

4.2. Therapies Targeting Transdifferentiation

Transdifferentiation is the conversion of one differentiated cell into another differentiated cell with a different phenotype without entering pluripotency [

122,

123]. The process of transdifferentiation in a cell can be achieved in many ways and one way is the mixed state. It is a state where the transition happens in such a way that at one point, the cells are in a ‘transient’ state that contains components of both cell types. A study by Lui et al. [

124] supports this phenomenon as the cells were found to transdifferentiate from fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Analysis showed that at the early stages of induced cardiomyocytes, cells were found to express markers for both cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts. Cells may also transdifferentiate by losing the original phenotype of the cell and acquiring a new cell type. They achieve this by undergoing an intermediate state that is similar to features of stemness. This state will not express markers for either of the cell types [

122,

125]. Lastly, cells may also revert to a progenitor cell type, either completely or partially, before they differentiate into a new cell type. For instance, Szabo et al. [

126] discuss the ability of dermal fibroblasts to convert into progenitor hematopoietic cells before they differentiate into erythrocytes, granulocytes, etc. The lack of use of mesodermal pathways or stem cells supports the evidence of the multipotency of progenitor cells. Moreover, this process can be performed by targeting organ-specific genes. For instance, Jonsson et al. [

127] observed that insulin-promoter-factor 1, also known as Pdx 1 is an important transcription factor in the development of the pancreas. Following this idea, Ber et al. [

128] showed, by ectopic Pdx 1 expression in the liver, that hepatic cells can transdifferentiate into a pancreatic phenotype with insulin-producing cells. In the field of oncogenesis, angiogenesis can thus be promoted [

129]. Glioblastoma cells have been reported to differentiate into endothelial cells via an intermediate-progenitor state and maintain a tumor environment. Notch pathway and VEGF were also known to play contributing factors [

130]. Likewise, BM-MSCs (bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells) also play a role in the tumor environment by interacting with tumor cells via multiple factors such as CCL5, TGFβ, and VEGF [

131].

While transdifferentiation can potentiate tumor growth, it has also been observed to play a therapeutic role in overcoming resistance. The first role of transdifferentiation as therapy was observed by de The et al [

132] where all-trans-retinoic acid was introduced as a treatment for APL (acute promyelocytic anemia). Newer studies have shown transdifferentiation of breast cancer cells into adipocytes downregulated tumor invasion and metastasis [

133]. TGFβ was found to induce the differentiation of mammary tumor cells into a mesenchymal characteristic state [

134,

135]. With induction of BMP2 (bone morphogenic protein 2) [

136], it further differentiated into the adipocytes lineage. These new cells were found to have similar expression of markers as mature adipocytes, such as FABD and PPARγ2 [

137,

138]. They are also observed to have downregulation of alpha-smooth muscle actin, a feature of the mesenchymal cells. This reprogramming is known to be reversible [

133].

In terms of oncogenic changes, the differentiated cells undergo cell cycle arrest with decreased expression of oncogenic genes such as Cdk2 and upregulation of tumor suppressive genes such as Cdkn2c. The differentiated cells also expressed PPARγ, transcription regular of adipogenesis and Zeb1, the factors regulating EMT state [

137,

139]. To maintain this stemness, it is imperative to know while TGFβ induces the EMT state, it is a known inhibitor of adipogenesis. By inhibiting a TGFβ inducing pathway, with a MEK inhibitor, this helps ensure adipogenesis takes place in the presence of TGFβ. The cells treated with MERK inhibitor were also treated with Rosiglitazone as it is known to induce transdifferentiation and promote adipogenesis. This combination also showed inhibition of metastasis and tumor invasion. There have not been many studies on transdifferentiation therapy use to overcome resistance, but this study raises the possibility of implementing its use in resistant tumors [

133,

134].

4.3. Therapies Targeting Differentiation

Recent advances in cancer differentiation highlight the potential of differentiation-based therapeutic approaches in cancer. Differentiation-based therapy was first used in cancer by Flynn et al. was in an acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) cell line [

140]. The study found that retinoic acid was able to stimulate granulocytic differentiation and maturation in the APL cell line, and in promyelocytes from patient samples. Subsequently, there has been a growing amount of literature supporting the use of retinoic acid, as well as its use in combination therapies for APL, including several cases where complete eradication of the tumor was possible in patients. In particular, the use of VPA in combination with retinoic acid has shown promise in inhibiting the proliferation of leukemia-initiating cells and improving overall survival [

141]. In other forms of cancers, studies on differentiation-based have also shown a number of promising preclinical results. Treatment of colon carcinoma with the vitamin D metabolite 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulated expression of E-cadherin, in addition to disrupting EMT and expression of Wnt/β-catenin genes. In addition, Takahashi et al. found an inhibitor of a RhoA-associated kinase (ROCK) to stimulate adipogenic conversion and inhibit proliferation of osteosarcoma stem cells [

142]. Similarly, Hirozane et al. noted inhibited growth of osteosarcoma cell lines when treated with NCB-0846, a small molecule inhibitor that disrupted the Wnt signaling pathway [

143]. Notably, disruption of Wnt signaling was observed to cause osteosarcoma cells to switch lineage, converting into adipocytes through the activation of PPARγ singaling. Hirozane et al. furthermore identified TINK, a kinase transactivator of Wnt, as a potential biomarker in osteosarcoma for therapeutic targeting.

5. Conclusions

Cancer cell plasticity is the ability of cancer cells to switch between different states or phenotypes in response to changes in their microenvironment. This plasticity promotes tumorigenesis as well as leads to the emergence of therapy-resistant cancer cells, which is an ongoing obstacle in cancer treatment. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and deregulated acetylation, can regulate gene expression and alter the cellular phenotype and are known to be involved in cancer development and progression. In particular, these changes are achieved through EMT or the state of dedifferentiation. The EMT process is associated with the acquisition of mesenchymal features and increased cell progression, metastasis, and resistance to apoptosis. This process is mediated by multiple transcription factors such as SNAIL, Zeb, and basic helix-loop-helix. Activating multiple pathways, they repress epithelial markers like cadherin and claudins and activate mesenchymal markers such as vimentin and fibronectin. EMT is associated with induced angiogenesis and tumor invasiveness. Another pathway tumor cells undergo tumor resistance with is dedifferentiation. It is the process of switching to a less differentiated state to further reverse back to a progenitor cell. It loses the expression of the original cells gene and induces the expression of the new phenotype state. Factors like SOX2 and NANOG are involved in this transformation with TGFβ as an associated inducer.

Overcoming therapeutic resistance is a clinical necessity and can probably be done by understanding these pathways. EMT programming has been controlled by focusing on inducers such as TGFβ and generating antibodies against it. MET and EGFR inhibitors have also been developed and proved to show therapeutic results in multiple solid tumors. Transdifferentiation, the switching of a differentiated cell to a different phenotypical differentiated cell has shown little yet promising role as a therapy to overcome resistance. Using TGFβ, cells undergo differentiation and use specific cell-type transcriptional regulators to undergo stemness. By targeting TGFβ and the specific pathway such as MEK for adipocytes, tumor cells transform into a different state than the drug-resistant phenotype. Additionally, it might also be important to forge more cross-disciplinary collaborations to better understand and target epigenetic events leading to plasticity. For example, a better understanding of materials in the process will help design novel engineered materials to target cell plasticity, particularly through dynamic changes in histone methylation and acetylation [

144].

Overall, the epigenetic regulation of cancer cell plasticity is a complex and dynamic process that involves multiple mechanisms and pathways. Understanding these mechanisms and their impact on therapy resistance is important for the development of new strategies to improve cancer treatment and patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the draft of this review article and approved its submission for publication. AA conceptualized, supervised and edited the article.

Funding

Medical Research Center grants no # MRC-01-21-118 and MRC-01-21-330 (AA), Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha Qatar.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grasmann, G., Mondal, A., & Leithner, K. (2021). Flexibility and Adaptation of Cancer Cells in a Heterogenous Metabolic Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci, 22(3). [CrossRef]

- Kreuzaler, P., Panina, Y., Segal, J., & Yuneva, M. (2020). Adapt and conquer: Metabolic flexibility in cancer growth, invasion and evasion. Mol Metab, 33, 83-101. [CrossRef]

- Alsayed, R., Sheikhan, K., Alam, M. A., Buddenkotte, J., Steinhoff, M., Uddin, S., et al. (2023). Epigenetic programing of cancer stemness by transcription factors-non-coding RNAs interactions. Semin Cancer Biol, 92, 74-83. [CrossRef]

- Wagers, A. J., & Weissman, I. L. (2004). Plasticity of adult stem cells. Cell, 116(5), 639-648. [CrossRef]

- Patil, K., Khan, F. B., Akhtar, S., Ahmad, A., & Uddin, S. (2021). The plasticity of pancreatic cancer stem cells: implications in therapeutic resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 40(3), 691-720. [CrossRef]

- Phi, L. T. H., Sari, I. N., Yang, Y. G., Lee, S. H., Jun, N., Kim, K. S., et al. (2018). Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int, 2018, 5416923. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A. (2013). Pathways to breast cancer recurrence. ISRN Oncol, 2013, 290568. [CrossRef]

- Marzagalli, M., Fontana, F., Raimondi, M., & Limonta, P. (2021). Cancer Stem Cells-Key Players in Tumor Relapse. Cancers (Basel), 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Rogoff, H. A., Keates, S., Gao, Y., Murikipudi, S., Mikule, K., et al. (2015). Suppression of cancer relapse and metastasis by inhibiting cancer stemness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(6), 1839-1844. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. S., Ahmad, A., Ali, S., Bao, B., Philip, P. A., & Sarkar, F. H. (2013). The role of cancer stem cells and miRNAs in defining the complexities of brain metastasis. J Cell Physiol, 228(1), 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Steinbichler, T. B., Savic, D., Dudas, J., Kvitsaridze, I., Skvortsov, S., Riechelmann, H., et al. (2020). Cancer stem cells and their unique role in metastatic spread. Semin Cancer Biol, 60, 148-156. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, L. M., & Eisenberg, C. A. (2003). Stem cell plasticity, cell fusion, and transdifferentiation. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today, 69(3), 209-218. [CrossRef]

- Filip, S., Mokry, J., English, D., & Vojacek, J. (2005). Stem cell plasticity and issues of stem cell therapy. Folia Biol (Praha), 51(6), 180-187.

- Orlic, D., Kajstura, J., Chimenti, S., Limana, F., Jakoniuk, I., Quaini, F., et al. (2001). Mobilized bone marrow cells repair the infarcted heart, improving function and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98(18), 10344-10349. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S. H., Witek, R. P., Bae, S. H., Zheng, D., Jung, Y., Piscaglia, A. C., et al. (2007). Bone marrow-derived hepatic oval cells differentiate into hepatocytes in 2-acetylaminofluorene/partial hepatectomy-induced liver regeneration. Gastroenterology, 132(3), 1077-1087. [CrossRef]

- Marjanovic, N. D., Weinberg, R. A., & Chaffer, C. L. (2013). Cell plasticity and heterogeneity in cancer. Clin Chem, 59(1), 168-179. [CrossRef]

- Thankamony, A. P., Saxena, K., Murali, R., Jolly, M. K., & Nair, R. (2020). Cancer Stem Cell Plasticity - A Deadly Deal. Front Mol Biosci, 7, 79. [CrossRef]

- van der Schaft, D. W., Hillen, F., Pauwels, P., Kirschmann, D. A., Castermans, K., Egbrink, M. G., et al. (2005). Tumor cell plasticity in Ewing sarcoma, an alternative circulatory system stimulated by hypoxia. Cancer Res, 65(24), 11520-11528. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Cong, Y., Wang, D., Sun, Y., Deng, L., Liu, Y., et al. (2014). Breast cancer stem cells transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states reflective of their normal counterparts. Stem Cell Reports, 2(1), 78-91. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S., Jiang, J., Lu, Y., Nice, E. C., Huang, C., Zhang, J., et al. (2020). Emerging role of tumor cell plasticity in modifying therapeutic response. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 5(1), 228. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z. D., Pang, K., Wu, Z. X., Dong, Y., Hao, L., Qin, J. X., et al. (2023). Tumor cell plasticity in targeted therapy-induced resistance: mechanisms and new strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 8(1), 113. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Goodrich, D. W. (2022). RB1, Cancer Lineage Plasticity, and Therapeutic Resistance. Annual Review of Cancer Biology, 6(1), 201-221. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S., Yamada-Okabe, H., Suzuki, M., Natori, O., Kato, A., Matsubara, K., et al. (2012). LGR5-positive colon cancer stem cells interconvert with drug-resistant LGR5-negative cells and are capable of tumor reconstitution. Stem Cells, 30(12), 2631-2644. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Saci, A., Szabo, P. M., Chasalow, S. D., Castillo-Martin, M., Domingo-Domenech, J., et al. (2018). EMT- and stroma-related gene expression and resistance to PD-1 blockade in urothelial cancer. Nat Commun, 9(1), 3503. [CrossRef]

- Shen, S., & Clairambault, J. (2020). Cell plasticity in cancer cell populations. F1000Res, 9. [CrossRef]

- Brabletz, S., Schuhwerk, H., Brabletz, T., & Stemmler, M. P. (2021). Dynamic EMT: a multi-tool for tumor progression. EMBO J, 40(18), e108647. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S., Feng, Y., & Cheng, L. (2019). Cellular Reprogramming as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Trends Cell Biol, 29(8), 623-634. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Sarkar, S. H., Bitar, B., Ali, S., Aboukameel, A., Sethi, S., et al. (2012). Garcinol regulates EMT and Wnt signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo, leading to anticancer activity against breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther, 11(10), 2193-2201. [CrossRef]

- Nieto, M. A., Huang, R. Y., Jackson, R. A., & Thiery, J. P. (2016). Emt: 2016. Cell, 166(1), 21-45. [CrossRef]

- Pei, D., Shu, X., Gassama-Diagne, A., & Thiery, J. P. (2019). Mesenchymal-epithelial transition in development and reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol, 21(1), 44-53. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R., & Weinberg, R. A. (2009). The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest, 119(6), 1420-1428. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Hong, W., & Wei, X. (2022). The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J Hematol Oncol, 15(1), 129. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, G. W. (2019). Control of Invasion by Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Programs during Metastasis. J Clin Med, 8(5). [CrossRef]

- Lamouille, S., Xu, J., & Derynck, R. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 15(3), 178-196. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Y., Guilford, P., & Thiery, J. P. (2012). Early events in cell adhesion and polarity during epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Sci, 125(Pt 19), 4417-4422. [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H., Olmeda, D., & Cano, A. (2007). Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer, 7(6), 415-428. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Maitah, M. Y., Ginnebaugh, K. R., Li, Y., Bao, B., Gadgeel, S. M., et al. (2013). Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling sensitizes NSCLC cells to standard therapies through modulation of EMT-regulating miRNAs. J Hematol Oncol, 6(1), 77. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. (2009). EMT: when epithelial cells decide to become mesenchymal-like cells. J Clin Invest, 119(6), 1417-1419. [CrossRef]

- Marconi, G. D., Fonticoli, L., Rajan, T. S., Pierdomenico, S. D., Trubiani, O., Pizzicannella, J., et al. (2021). Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT): The Type-2 EMT in Wound Healing, Tissue Regeneration and Organ Fibrosis. Cells, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V. (2018). Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition in Tumor Metastasis. Annu Rev Pathol, 13, 395-412. [CrossRef]

- Beerling, E., Seinstra, D., de Wit, E., Kester, L., van der Velden, D., Maynard, C., et al. (2016). Plasticity between Epithelial and Mesenchymal States Unlinks EMT from Metastasis-Enhancing Stem Cell Capacity. Cell Rep, 14(10), 2281-2288. [CrossRef]

- Pastushenko, I., Mauri, F., Song, Y., de Cock, F., Meeusen, B., Swedlund, B., et al. (2021). Fat1 deletion promotes hybrid EMT state, tumour stemness and metastasis. Nature, 589(7842), 448-455. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M. S., Fu, L. H., Yan, H. C., Cheng, L. Y., Ru, H. M., Mo, S., et al. (2022). Proteomics and liquid biopsy characterization of human EMT-related metastasis in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol, 12, 790096. [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, A., Gruber, D. C., Pisarsky, L., Heck, C., Kunita, A., Yilmaz, M., et al. (2014). VEGF-mediated angiogenesis links EMT-induced cancer stemness to tumor initiation. Cancer Res, 74(5), 1566-1575. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Bardia, A., Wittner, B. S., Stott, S. L., Smas, M. E., Ting, D. T., et al. (2013). Circulating breast tumor cells exhibit dynamic changes in epithelial and mesenchymal composition. Science, 339(6119), 580-584. [CrossRef]

- Mani, S. A., Guo, W., Liao, M. J., Eaton, E. N., Ayyanan, A., Zhou, A. Y., et al. (2008). The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell, 133(4), 704-715. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Mani, S. A., Donaher, J. L., Ramaswamy, S., Itzykson, R. A., Come, C., et al. (2004). Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell, 117(7), 927-939. [CrossRef]

- Zubair, H., & Ahmad, A. (2017). Chapter 1 - Cancer Metastasis: An Introduction. In A. Ahmad (Ed.), Introduction to Cancer Metastasis (pp. 3-12): Academic Press.

- Kasimir-Bauer, S., Hoffmann, O., Wallwiener, D., Kimmig, R., & Fehm, T. (2012). Expression of stem cell and epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in primary breast cancer patients with circulating tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res, 14(1), R15. [CrossRef]

- Mego, M., Mani, S. A., Lee, B. N., Li, C., Evans, K. W., Cohen, E. N., et al. (2012). Expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-inducing transcription factors in primary breast cancer: The effect of neoadjuvant therapy. Int J Cancer, 130(4), 808-816. [CrossRef]

- Khoo, B. L., Lee, S. C., Kumar, P., Tan, T. Z., Warkiani, M. E., Ow, S. G., et al. (2015). Short-term expansion of breast circulating cancer cells predicts response to anti-cancer therapy. Oncotarget, 6(17), 15578-15593. [CrossRef]

- Barriere, G., Fici, P., Gallerani, G., Fabbri, F., Zoli, W., & Rigaud, M. (2014). Circulating tumor cells and epithelial, mesenchymal and stemness markers: characterization of cell subpopulations. Ann Transl Med, 2(11), 109. [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T., Brooks, M. W., Inan, M. F., Reinhardt, F., & Weinberg, R. A. (2012). The outgrowth of micrometastases is enabled by the formation of filopodium-like protrusions. Cancer Discov, 2(8), 706-721. [CrossRef]

- Malta, T. M., Sokolov, A., Gentles, A. J., Burzykowski, T., Poisson, L., Weinstein, J. N., et al. (2018). Machine Learning Identifies Stemness Features Associated with Oncogenic Dedifferentiation. Cell, 173(2), 338-354 e315. [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. H., Kwon, S., Jun, E. K., Kim, A., Whang, K. Y., Kim, H., et al. (2011). Nanog-induced dedifferentiation of p53-deficient mouse astrocytes into brain cancer stem-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 412(1), 175-181. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M., Kikushige, Y., Miyawaki, K., Kunisaki, Y., Mizuno, S., Takenaka, K., et al. (2019). Dedifferentiation process driven by TGF-beta signaling enhances stem cell properties in human colorectal cancer. Oncogene, 38(6), 780-793. [CrossRef]

- Flavahan, W. A., Gaskell, E., & Bernstein, B. E. (2017). Epigenetic plasticity and the hallmarks of cancer. Science, 357(6348). [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, A., & Nakanishi, M. (2021). Navigating the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet, 37(11), 1012-1027. [CrossRef]

- Ku, S. C., Liu, H. L., Su, C. Y., Yeh, I. J., Yen, M. C., Anuraga, G., et al. (2022). Comprehensive analysis of prognostic significance of cadherin (CDH) gene family in breast cancer. Aging (Albany NY), 14(20), 8498-8567. [CrossRef]

- Tur, M. K., Daramola, A. K., Gattenlohner, S., Herling, M., Chetty, S., & Barth, S. (2017). Restoration of DAP Kinase Tumor Suppressor Function: A Therapeutic Strategy to Selectively Induce Apoptosis in Cancer Cells Using Immunokinase Fusion Proteins. Biomedicines, 5(4). [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Xiong, W., Liu, X., Xiao, W., Guo, Y., Tan, J., et al. (2019). Hypomethylation at non-CpG/CpG sites in the promoter of HIF-1alpha gene combined with enhanced H3K9Ac modification contribute to maintain higher HIF-1alpha expression in breast cancer. Oncogenesis, 8(4), 26. [CrossRef]

- Stone, A., Cowley, M. J., Valdes-Mora, F., McCloy, R. A., Sergio, C. M., Gallego-Ortega, D., et al. (2013). BCL-2 hypermethylation is a potential biomarker of sensitivity to antimitotic chemotherapy in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther, 12(9), 1874-1885. [CrossRef]

- Flavahan, W. A., Drier, Y., Liau, B. B., Gillespie, S. M., Venteicher, A. S., Stemmer-Rachamimov, A. O., et al. (2016). Insulator dysfunction and oncogene activation in IDH mutant gliomas. Nature, 529(7584), 110-114. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N., Parbin, S., Kar, S., Das, L., Kirtana, R., Suma Seshadri, G., et al. (2019). Epigenetic silencing of genes enhanced by collective role of reactive oxygen species and MAPK signaling downstream ERK/Snail axis: Ectopic application of hydrogen peroxide repress CDH1 gene by enhanced DNA methyltransferase activity in human breast cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 1865(6), 1651-1665. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Zheng, Y., Dai, M., Wang, X., Wu, J., Yu, B., et al. (2019). G9a and histone deacetylases are crucial for Snail2-mediated E-cadherin repression and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci, 110(11), 3442-3452. [CrossRef]

- Romero, S., Musleh, M., Bustamante, M., Stambuk, J., Pisano, R., Lanzarini, E., et al. (2018). Polymorphisms in TWIST1 and ZEB1 Are Associated with Prognosis of Gastric Cancer Patients. Anticancer Res, 38(7), 3871-3877. [CrossRef]

- Paco, A., Leitao-Castro, J., & Freitas, R. (2021). Epigenetic Regulation of CDH1 Is Altered after HOXB7-Silencing in MDA-MB-468 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Genes (Basel), 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, D., Deb, M., Rath, S. K., Kar, S., Parbin, S., Pradhan, N., et al. (2016). DNA methylation and not H3K4 trimethylation dictates the expression status of miR-152 gene which inhibits migration of breast cancer cells via DNMT1/CDH1 loop. Exp Cell Res, 346(2), 176-187. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, D., Deb, M., & Patra, S. K. (2018). Antagonistic activities of miR-148a and DNMT1: Ectopic expression of miR-148a impairs DNMT1 mRNA and dwindle cell proliferation and survival. Gene, 660, 68-79. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. Q., Lee, M., Lim, W. J., Lee, S., Lim, C. H., & Lim, J. H. (2022). PGC1alpha Cooperates with FOXA1 to Regulate Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition through the TCF4-TWIST1. Int J Mol Sci, 23(15). [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S. B. (2012). The cancer epigenome: its origins, contributions to tumorigenesis, and translational implications. Proc Am Thorac Soc, 9(2), 64-65. [CrossRef]

- Kar, S., Niharika, Roy, A., & Patra, S. K. (2023). Overexpression of SOX2 Gene by Histone Modifications: SOX2 Enhances Human Prostate and Breast Cancer Progression by Prevention of Apoptosis and Enhancing Cell Proliferation. Oncology, 101(9), 591-608. [CrossRef]

- Niharika, Roy, A., Mishra, J., Chakraborty, S., Singh, S. P., & Patra, S. K. (2023). Epigenetic regulation of pluripotency inducer genes NANOG and SOX2 in human prostate cancer. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci, 197, 241-260. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Jin, J., Wan, F., Zhao, L., Chu, H., Chen, C., et al. (2019). AMPK Promotes SPOP-Mediated NANOG Degradation to Regulate Prostate Cancer Cell Stemness. Dev Cell, 48(3), 345-360 e347. [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M. L., Francescangeli, F., La Torre, F., & Zeuner, A. (2019). Stem Cell Plasticity and Dormancy in the Development of Cancer Therapy Resistance. Front Oncol, 9, 626. [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C. D., & Campisi, J. (2021). The metabolic roots of senescence: mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat Metab, 3(10), 1290-1301. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S., Bhattacharya, A., Adhikary, S., Singh, V., Gadad, S. S., Roy, S., et al. (2022). The paradigm of drug resistance in cancer: an epigenetic perspective. Biosci Rep, 42(4). [CrossRef]

- Toh, T. B., Lim, J. J., & Chow, E. K. (2017). Epigenetics in cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer, 16(1), 29. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Li, Y., Bao, B., Kong, D., & Sarkar, F. H. (2014). Epigenetic regulation of miRNA-cancer stem cells nexus by nutraceuticals. Mol Nutr Food Res, 58(1), 79-86. [CrossRef]

- Choi, M., Kipps, T., & Kurzrock, R. (2016). ATM Mutations in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Mol Cancer Ther, 15(8), 1781-1791. [CrossRef]

- Vasiliou, V., Vasiliou, K., & Nebert, D. W. (2009). Human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family. Hum Genomics, 3(3), 281-290. [CrossRef]

- Moitra, K. (2015). Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Stem Cells. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 635745. [CrossRef]

- Honoki, K., Fujii, H., Kubo, A., Kido, A., Mori, T., Tanaka, Y., et al. (2010). Possible involvement of stem-like populations with elevated ALDH1 in sarcomas for chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Oncol Rep, 24(2), 501-505. [CrossRef]

- Peitzsch, C., Cojoc, M., Hein, L., Kurth, I., Mabert, K., Trautmann, F., et al. (2016). An Epigenetic Reprogramming Strategy to Resensitize Radioresistant Prostate Cancer Cells. Cancer Res, 76(9), 2637-2651. [CrossRef]

- Fernald, K., & Kurokawa, M. (2013). Evading apoptosis in cancer. Trends Cell Biol, 23(12), 620-633. [CrossRef]

- Taniai, M., Grambihler, A., Higuchi, H., Werneburg, N., Bronk, S. F., Farrugia, D. J., et al. (2004). Mcl-1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res, 64(10), 3517-3524. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. W., Lee, M. C., Hsu, N. Y., Wu, T. C., Wu, J. Y., Wang, Y. C., et al. (2015). FHIT loss confers cisplatin resistance in lung cancer via the AKT/NF-kappaB/Slug-mediated PUMA reduction. Oncogene, 34(29), 3882-3883. [CrossRef]

- Lu, M., Marsters, S., Ye, X., Luis, E., Gonzalez, L., & Ashkenazi, A. (2014). E-cadherin couples death receptors to the cytoskeleton to regulate apoptosis. Mol Cell, 54(6), 987-998. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A., & Hillen, T. (2016). Mathematical Modeling of the Role of Survivin on Dedifferentiation and Radioresistance in Cancer. Bull Math Biol, 78(6), 1162-1188. [CrossRef]

- Chakravarti, A., Zhai, G. G., Zhang, M., Malhotra, R., Latham, D. E., Delaney, M. A., et al. (2004). Survivin enhances radiation resistance in primary human glioblastoma cells via caspase-independent mechanisms. Oncogene, 23(45), 7494-7506. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Duan, N., Zhang, C., & Zhang, W. (2016). Survivin and Tumorigenesis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. J Cancer, 7(3), 314-323. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A., Sakr, W. A., & Rahman, K. M. (2012). Novel targets for detection of cancer and their modulation by chemopreventive natural compounds. Front Biosci (Elite Ed), 4(1), 410-425. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K. M., Banerjee, S., Ali, S., Ahmad, A., Wang, Z., Kong, D., et al. (2009). 3,3'-Diindolylmethane enhances taxotere-induced apoptosis in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells through survivin down-regulation. Cancer Res, 69(10), 4468-4475. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Gibbons, D. L., Goswami, S., Cortez, M. A., Ahn, Y. H., Byers, L. A., et al. (2014). Metastasis is regulated via microRNA-200/ZEB1 axis control of tumour cell PD-L1 expression and intratumoral immunosuppression. Nat Commun, 5, 5241. [CrossRef]

- Vathiotis, I. A., Gomatou, G., Stravopodis, D. J., & Syrigos, N. (2021). Programmed Death-Ligand 1 as a Regulator of Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci, 22(10). [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T., & Weinberg, R. A. (2017). EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: the mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 14(10), 611-629. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A., Kim, Y. J., Robert, L., Tsoi, J., Comin-Anduix, B., Berent-Maoz, B., et al. (2018). Immunotherapy Resistance by Inflammation-Induced Dedifferentiation. Cancer Discov, 8(8), 935-943. [CrossRef]

- Fetsch, P. A., Marincola, F. M., Filie, A., Hijazi, Y. M., Kleiner, D. E., & Abati, A. (1999). Melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells (MART-1): the advent of a preferred immunocytochemical antibody for the diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma with fine-needle aspiration. Cancer, 87(1), 37-42.

- Bakker, A. B., Schreurs, M. W., de Boer, A. J., Kawakami, Y., Rosenberg, S. A., Adema, G. J., et al. (1994). Melanocyte lineage-specific antigen gp100 is recognized by melanoma-derived tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med, 179(3), 1005-1009. [CrossRef]

- Boiko, A. D., Razorenova, O. V., van de Rijn, M., Swetter, S. M., Johnson, D. L., Ly, D. P., et al. (2010). Human melanoma-initiating cells express neural crest nerve growth factor receptor CD271. Nature, 466(7302), 133-137. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Xiao, Q., Xiao, J., Niu, C., Li, Y., Zhang, X., et al. (2022). Wnt/beta-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 7(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M. (2014). Can we safely target the WNT pathway? Nat Rev Drug Discov, 13(7), 513-532. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, M., & Katoh, M. (2022). WNT signaling and cancer stemness. Essays Biochem, 66(4), 319-331. [CrossRef]

- Teeuwssen, M., & Fodde, R. (2019). Wnt Signaling in Ovarian Cancer Stemness, EMT, and Therapy Resistance. J Clin Med, 8(10). [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C. A., Fridman, J. S., Yang, M., Lee, S., Baranov, E., Hoffman, R. M., et al. (2002). A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell, 109(3), 335-346. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T., Ambrosi, G., Wandmacher, A. M., Rauscher, B., Betge, J., Rindtorff, N., et al. (2019). MEK inhibitors activate Wnt signalling and induce stem cell plasticity in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun, 10(1), 2197. [CrossRef]

- Jimeno, A., Gordon, M., Chugh, R., Messersmith, W., Mendelson, D., Dupont, J., et al. (2017). A First-in-Human Phase I Study of the Anticancer Stem Cell Agent Ipafricept (OMP-54F28), a Decoy Receptor for Wnt Ligands, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 23(24), 7490-7497. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Liu, X., & Pauklin, S. (2021). 3D chromatin architecture and epigenetic regulation in cancer stem cells. Protein Cell, 12(6), 440-454. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, D. R., Borges, K. S., Finco, I., LaPensee, C. R., Rege, J., Little, D. W., et al. (2023). Abstract 1501: Epigenetic dedifferentiation as a therapeutic strategy in adrenal cancer. Cancer Research, 83(7_Supplement), 1501-1501. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y., Haga, H., & Yamada, Y. (2014). Concise review: dedifferentiation meets cancer development: proof of concept for epigenetic cancer. Stem Cells Transl Med, 3(10), 1182-1187. [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, P., & Misteli, T. (2010). Cancer epigenetics: from disruption of differentiation programs to the emergence of cancer stem cells. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol, 75, 251-258. [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, C. A., Feng, Y., Sokol, E. S., Tillman, E. J., Sanduja, S., Reinhardt, F., et al. (2014). De-differentiation confers multidrug resistance via noncanonical PERK-Nrf2 signaling. PLoS Biol, 12(9), e1001945. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, M., Stephens, M. A., Pathak, H., & Rangarajan, A. (2011). Transcription factors that mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition lead to multidrug resistance by upregulating ABC transporters. Cell Death Dis, 2(7), e179. [CrossRef]

- Fung, S. W., Cheung, P. F., Yip, C. W., Ng, L. W., Cheung, T. T., Chong, C. C., et al. (2019). The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCF1 is a hepatic oncofetal protein that promotes chemoresistance, EMT and cancer stemness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett, 457, 98-109. [CrossRef]

- Debeb, B. G., Lacerda, L., Xu, W., Larson, R., Solley, T., Atkinson, R., et al. (2012). Histone deacetylase inhibitors stimulate dedifferentiation of human breast cancer cells through WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Stem Cells, 30(11), 2366-2377. [CrossRef]

- Morris, J. C., Tan, A. R., Olencki, T. E., Shapiro, G. I., Dezube, B. J., Reiss, M., et al. (2014). Phase I study of GC1008 (fresolimumab): a human anti-transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) monoclonal antibody in patients with advanced malignant melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One, 9(3), e90353. [CrossRef]

- Birchmeier, C., Birchmeier, W., Gherardi, E., & Vande Woude, G. F. (2003). Met, metastasis, motility and more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 4(12), 915-925. [CrossRef]

- Douillard, J. Y., Ostoros, G., Cobo, M., Ciuleanu, T., McCormack, R., Webster, A., et al. (2014). First-line gefitinib in Caucasian EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC patients: a phase-IV, open-label, single-arm study. Br J Cancer, 110(1), 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Beasley, G. M., Riboh, J. C., Augustine, C. K., Zager, J. S., Hochwald, S. N., Grobmyer, S. R., et al. (2011). Prospective multicenter phase II trial of systemic ADH-1 in combination with melphalan via isolated limb infusion in patients with advanced extremity melanoma. J Clin Oncol, 29(9), 1210-1215. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M., Yelle, N., Venugopal, C., & Singh, S. K. (2018). EMT: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther, 182, 80-94. [CrossRef]

- Elaskalani, O., Razak, N. B., Falasca, M., & Metharom, P. (2017). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition as a therapeutic target for overcoming chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol, 9(1), 37-41. [CrossRef]

- Reid, A., & Tursun, B. (2018). Transdifferentiation: do transition states lie on the path of development? Curr Opin Syst Biol, 11, 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Cieslar-Pobuda, A., Knoflach, V., Ringh, M. V., Stark, J., Likus, W., Siemianowicz, K., et al. (2017). Transdifferentiation and reprogramming: Overview of the processes, their similarities and differences. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, 1864(7), 1359-1369. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Wang, L., Welch, J. D., Ma, H., Zhou, Y., Vaseghi, H. R., et al. (2017). Single-cell transcriptomics reconstructs fate conversion from fibroblast to cardiomyocyte. Nature, 551(7678), 100-104. [CrossRef]

- Jarriault, S., Schwab, Y., & Greenwald, I. (2008). A Caenorhabditis elegans model for epithelial-neuronal transdifferentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 105(10), 3790-3795. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, E., Rampalli, S., Risueno, R. M., Schnerch, A., Mitchell, R., Fiebig-Comyn, A., et al. (2010). Direct conversion of human fibroblasts to multilineage blood progenitors. Nature, 468(7323), 521-526. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, J., Carlsson, L., Edlund, T., & Edlund, H. (1994). Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature, 371(6498), 606-609. [CrossRef]

- Ber, I., Shternhall, K., Perl, S., Ohanuna, Z., Goldberg, I., Barshack, I., et al. (2003). Functional, persistent, and extended liver to pancreas transdifferentiation. J Biol Chem, 278(34), 31950-31957. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Wu, T., Liu, A. Y., & Ouyang, G. (2015). Differentiation and transdifferentiation potentials of cancer stem cells. Oncotarget, 6(37), 39550-39563. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Chadalavada, K., Wilshire, J., Kowalik, U., Hovinga, K. E., Geber, A., et al. (2010). Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature, 468(7325), 829-833. [CrossRef]

- Barcellos-de-Souza, P., Gori, V., Bambi, F., & Chiarugi, P. (2013). Tumor microenvironment: bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells as key players. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1836(2), 321-335. [CrossRef]

- de The, H. (2018). Differentiation therapy revisited. Nat Rev Cancer, 18(2), 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Ishay-Ronen, D., Diepenbruck, M., Kalathur, R. K. R., Sugiyama, N., Tiede, S., Ivanek, R., et al. (2019). Gain Fat-Lose Metastasis: Converting Invasive Breast Cancer Cells into Adipocytes Inhibits Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Cell, 35(1), 17-32 e16. [CrossRef]

- Ishay-Ronen, D., & Christofori, G. (2019). Targeting Cancer Cell Metastasis by Converting Cancer Cells into Fat. Cancer Res, 79(21), 5471-5475. [CrossRef]

- Bruna, A., Greenwood, W., Le Quesne, J., Teschendorff, A., Miranda-Saavedra, D., Rueda, O. M., et al. (2012). TGFbeta induces the formation of tumour-initiating cells in claudinlow breast cancer. Nat Commun, 3, 1055. [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Medela, A. M., Jumabay, M., & Bostrom, K. I. (2019). Beyond the bone: Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in adipose tissue. Obes Rev, 20(5), 648-658. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Wang, D., Zhao, W., & Xu, L. (2018). Deciphering the Roles of PPARgamma in Adipocytes via Dynamic Change of Transcription Complex. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 9, 473. [CrossRef]

- Shan, T., Liu, W., & Kuang, S. (2013). Fatty acid binding protein 4 expression marks a population of adipocyte progenitors in white and brown adipose tissues. FASEB J, 27(1), 277-287. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., El-Naggar, S., Darling, D. S., Higashi, Y., & Dean, D. C. (2008). Zeb1 links epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cellular senescence. Development, 135(3), 579-588. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, P. J., Miller, W. J., Weisdorf, D. J., Arthur, D. C., Brunning, R., & Branda, R. F. (1983). Retinoic acid treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: in vitro and in vivo observations. Blood, 62(6), 1211-1217.

- Leiva, M., Moretti, S., Soilihi, H., Pallavicini, I., Peres, L., Mercurio, C., et al. (2012). Valproic acid induces differentiation and transient tumor regression, but spares leukemia-initiating activity in mouse models of APL. Leukemia, 26(7), 1630-1637. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N., Nobusue, H., Shimizu, T., Sugihara, E., Yamaguchi-Iwai, S., Onishi, N., et al. (2019). ROCK Inhibition Induces Terminal Adipocyte Differentiation and Suppresses Tumorigenesis in Chemoresistant Osteosarcoma Cells. Cancer Res, 79(12), 3088-3099. [CrossRef]

- Hirozane, T., Masuda, M., Sugano, T., Sekita, T., Goto, N., Aoyama, T., et al. (2021). Direct conversion of osteosarcoma to adipocytes by targeting TNIK. JCI Insight, 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Nemec, S., & Kilian, K. A. (2021). Materials control of the epigenetics underlying cell plasticity. Nature Reviews Materials, 6(1), 69-83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).