1. Introduction

Optical microcavities attract much interest in optical sensing due to their capacity for leveraging the fundamental properties of light and the resonant effects for detecting subtle changes in their surroundings. This makes them highly versatile and attractive for a broad range of analyses, including measurements of physical and chemical parameters (e.g., temperature, humidity, stress, and pH) and detection of biological markers (e.g., enzymes, nucleic acids, and antibodies) [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Recent advances in optical microcavity technologies have enabled the development of sensors that are not only more sensitive, but also more accurate in detecting specific targets in complex and noisy environments. These improvements are essential for applications where accuracy and reliability are crucial, such as cancer diagnosis. Due to enhanced sensor performance, including higher sensitivity and selectivity, optical microcavities can be used for precise and reliable measurements, ultimately advancing decision-making processes in critical applications.

Despite these advances, significant limitations remain. One key limitation is the challenge of maintaining high sensitivity and selectivity in diverse and dynamic environments, particularly if trace amounts of analytes are to be detected and if operation under real-time conditions is required. The need for scalability and cost-effective fabrication methods also requires further improvement to ensure broader adoption of these technologies. Additionally, the integration of novel materials and hybrid configurations in order to expand sensing capabilities remains insufficient, leaving room for innovations in both design and implementation.

This review explores the latest developments in optical microcavity sensors and highlights how functionalization enhances their sensing capability. We provide an overview of the key materials used to improve sensor configurations and various techniques employed to optimize the performance of optical microcavities used for sensing. We also discuss the challenges facing further development and application of these technologies.

2. Functionalized Optical Microcavities

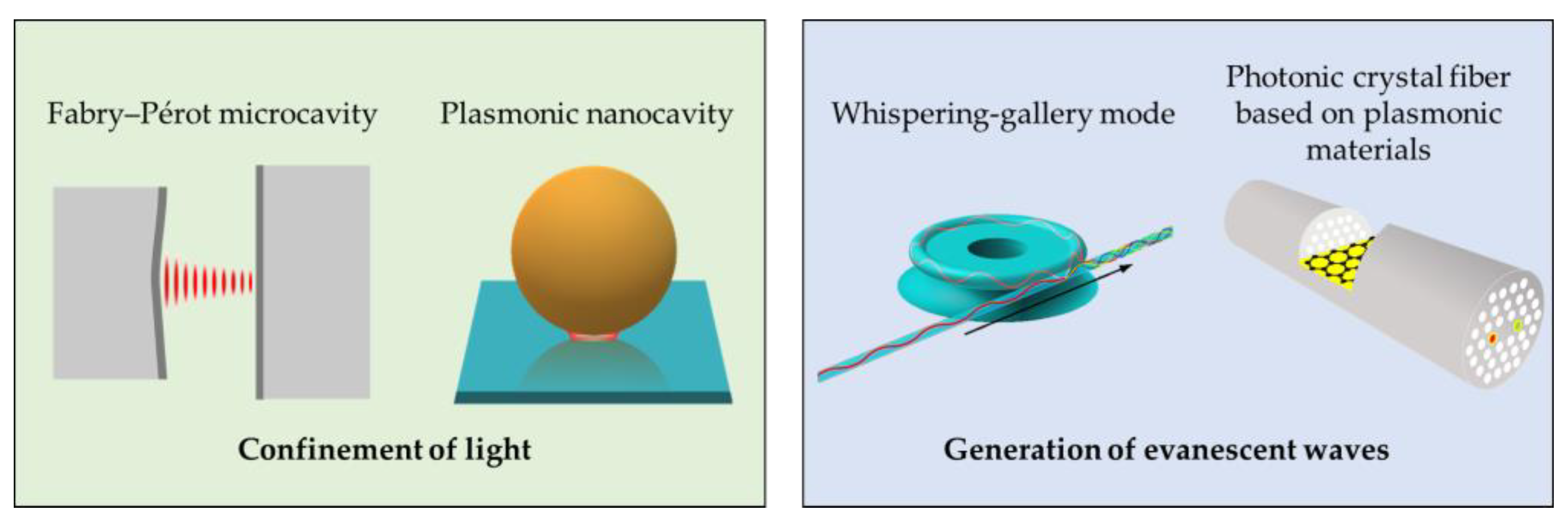

Optical microcavities, such as Fabry–Pérot (FP) microcavities, microcavities based on plasmonic materials (e.g., photonic crystal fiber (PCF) plasmonic sensors and plasmon nanocavities), and whispering-gallery mode (WGM) microcavities (e.g., microring resonators) are emerging as powerful tools in sensing technologies. Depending on their configuration, these microcavities can either concentrate light, as do Fabry–Pérot microcavities and nanocavities, or generate evanescent waves at the interface of dielectric and plasmonic materials, as do PCF plasmonic sensors and WGM microcavities (

Figure 1).

Optical microcavities operate through a resonance mechanism to confine the light. Within their small volumes, light interacts with external objects or surrounding environment, which results in detectable spectral shifts, broadening or splitting of resonance peaks, or changes in the intensity of light escaping the cavity. These effects, driven primarily by variations of the refractive index and optical confinement, make optical microcavities highly sensitive to even subtle environmental changes.

The two main detection mechanisms used with functionalized optical microcavities are based on recording refractive index changes or fluorescence. Compared to other sensing systems, optical microcavities stand out for their superior performance due to two key factors: their capacity for confining light within small volumes and their high potential for localized and highly efficient chemical functionalization. This combination enables the sensitive and selective detection of physical, chemical, or biological changes in surrounding media.

Functionalized optical microcavities combine materials with different optical properties, such as high-reflectance materials (e.g., Bragg mirrors), plasmonic nanoparticles (e.g., gold and silver ones), and quantum dots (QDs). These materials augment the detection capability of the microcavity by enhancing light–matter interactions and boosting sensitivity and selectivity. Additional strategies include the use of novel materials and hybrid and other advanced designs, such as enhanced surface functionalization, and microfluidics [

5]. Furthermore, employing artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to filter noise and reduce false positives offers a path to even greater precision of detection. Despite the resultant advantages, such as rapid response and versatility, challenges still remain in terms of the ease of fabrication, long-term stability, and material compatibility.

One of the key approaches involving plasmonic materials employs the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) phenomena. These effects ensure better light confinement and are foundational for highly sensitive sensors that respond to changes in the refractive index caused by analyte binding. Recent advances in nanometer-precise lithography and colloidal synthesis have enabled fine tunability of LSPR in the visible and near-infrared ranges, broadening the application scope of these sensors.

Polymers are also used in optical microcavities due to their flexibility, transparency, and biocompatibility [

6]. The main developments in this area have focused on improving the material properties, fabrication techniques, and integration strategies, including block copolymer self-assembly and layer-by-layer assembly for precise control of the film thickness and composition [

7]. Advanced techniques used with these materials include electrospinning in the case of ultrafine polymer fibers with a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and photopolymerization in the case of submicron-resolution 3D structures. They reduce manufacturing time and support complex designs [

8].

Two-dimensional (2D) materials, such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides, show great promise for sensor applications due to their ultrathin structures and exceptional sensitivity. These materials reduce losses, improve biocompatibility and ensure molecular specificity [

9], which makes them ideal for applications in early diagnosis of a number of diseases, including cancer [

10]. For example, graphene stands out for its exceptional properties, including high electrical conductivity, large surface area, chemical inertness, and thickness (about 0.3 nm [

11]), which make it a prime candidate for sensor applications [

12].

Quantum dots, semiconductor nanocrystals ranging from 1 to 12 nm in diameter, have unique optical and electronic properties, including high quantum yields, long fluorescence lifetimes, large extinction coefficients, narrow emission spectra, and high photostability. These properties can be tuned by adjusting their size [

13], composition, or surface ligands [

14]. Their surface chemistry can be modified to improve the sensor specificity, enabling their integration with various detection methods, such as fluorescence, electrochemistry, and Raman scattering measurements. By combining QDs with other nanomaterials, e.g., molecularly imprinted polymers and noble metal nanoparticles, the sensor performance can be significantly improved. These hybrid systems are particularly effective in detecting complex analytes, including antibiotics and metal ions, by leveraging both the optical properties of QDs and the functionalities of the other materials [

15]. However, challenges still remain related to optimizing real-world applications, particularly reducing the QD toxicity.

In biosensing applications of sensors based on optical microcavities, bio-recognition elements play a critical role in enabling high sensitivity and specificity. When the target analyte is recognized and bound by the sensing element of the sensor through specific molecular interactions, its physical properties, such as the refractive index, are changed. Bio-recognition elements include antibodies, enzymes, nucleic acids, aptamers, phages, peptides, lectins, and molecularly imprinted polymers, all of which selectively interacting with the target molecules [

16,

17,

18].

Further improvement of functionalized optical microcavities is essential for advancing various sensing applications. Current efforts are focused on enhancing sensor performance for detecting smaller analyte quantities, achieving faster real-time responses, and enhancing the selectivity in complex environments. Future developments in functionalized microcavity designs are aimed at increasing the sensitivity to the degree where single molecules can be detected and expanding the range of applications of the microcavities.

3. Fabry–Pérot Microcavities

Fabry–Pérot microcavities are optical resonators consisting of two reflective surfaces, such as metal layers or Bragg mirrors (one-dimensional photonic crystals), separated by a central cavity. This configuration enables the confinement of light inside the cavity, facilitating precise optical interactions and high resonance quality. Common materials used for the fabrication of FP microcavities include metals, such as gold and silver, known for their excellent reflective properties; dielectric materials, such as TiO₂, Ta₂O₅, ZnS, GaAs, SiO₂, and MgF₂; and semiconductors, such as Si, Ge, and GaN. More recent designs use novel combinations, e.g., Ag/Si [

19] and Si/Si₃N₄ [

20], which substantially improve the performance of these microcavities by ensuring the optimal photonic bandgap structure and a superior refractive index contrast.

Fabry–Pérot microcavities offer a powerful research platform that enable precise light–matter coupling, offering high-quality light confinement and strong resonance effects. These properties make them effective for detecting refractive index changes due to environmental factors, with applications in biology, chemistry, and environmental monitoring, such as gas detection [

21,

22], food safety assessment and early cancer biomarker detection, where timely intervention can significantly improve treatment outcomes [

23]. When the physical properties of FP microcavities are modified, they become exceptionally sensitive tools for detecting variations in humidity, pressure, temperature [

24], and ionizing radiation [

25].

Obtaining SPR in FP microcavities further sharpens the resonance peaks (i.e., narrows the linewidths), which decreases the detection threshold. At the same time, LSPR provides a high spatial resolution due to localized field enhancement facilitated by metal nanoparticles. Combining these mechanisms in FP microcavities amplifies the resonance sensitivity and tailors the optical responses, thus enhancing the sensing capability. Some innovative designs use the metal/cavity/multilayer porous TiO

2 photonic crystal structure to employ Tamm plasmon resonance for detecting traces of heavy metals [

26]. Fabry–Pérot microcavities, which confine light between two mirrors to create resonant optical modes, can support Tamm plasmon resonance if properly configured, which results in hybrid Tamm plasmon–cavity modes. These configurations have the potential for higher sensitivity [

27] and detection accuracy [

28]. Nanoparticles embedded in the layers further enhance the detection capability by boosting refractive index contrasts [

29,

30].

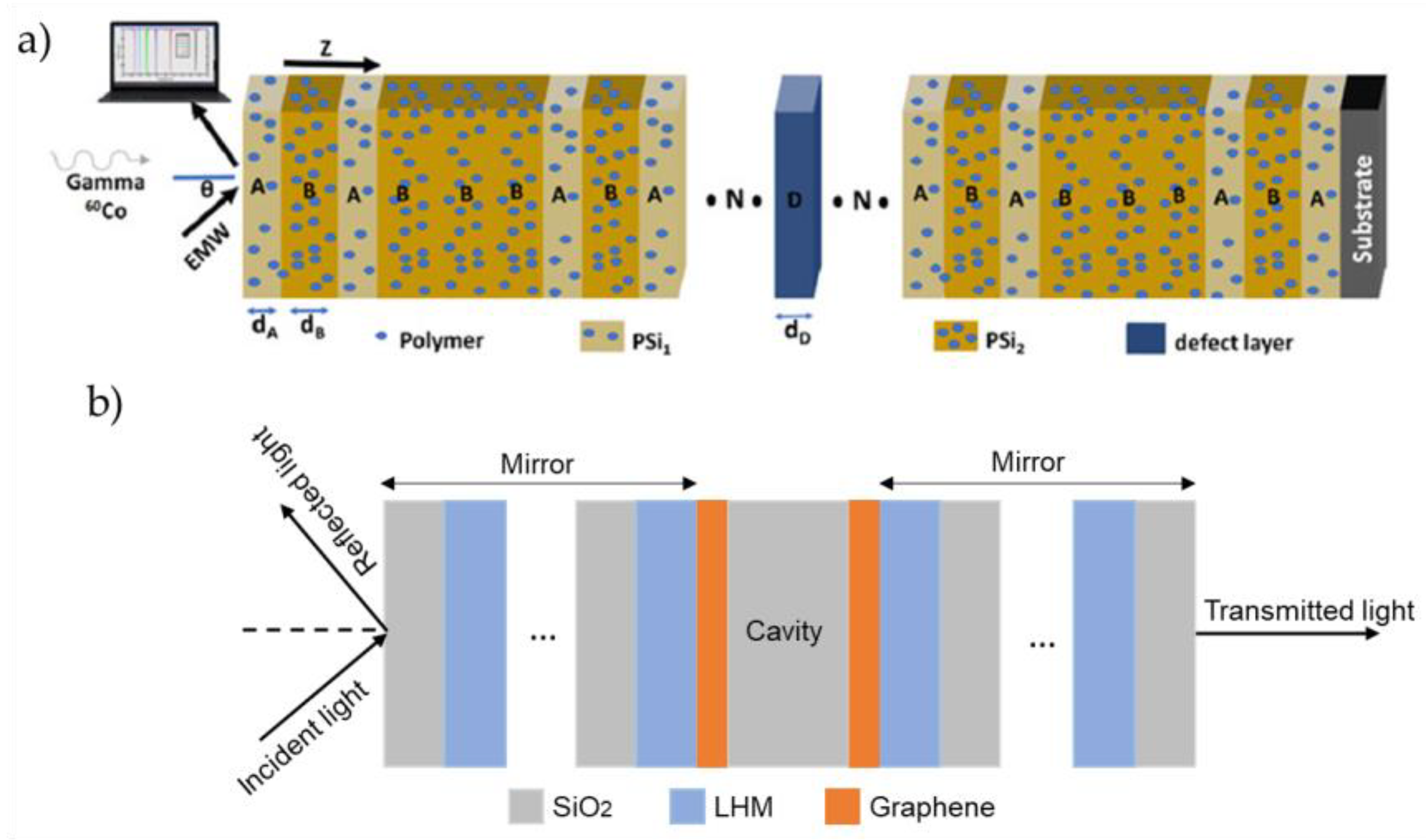

Polymers and inorganic materials are also employed in FP microcavity designs to expand their functional capabilities. For example, simulation predicts an impressive sensitivity of gamma radiation sensors based on porous silicon doped with polymers, which makes these configurations valuable for medical applications [

25] (

Figure 2 (a)). The sensor incorporates porous silicon layers with a high refractive index contrast, doped with a polymer of polyvinyl alcohol, carbol fuchsin and crystal violet (Layers A and B in Fig.2 (a)). The cavity itself is formed from the same polymer composition (Layer D in Fig.2 (a)). The results show a sensitivity of 0.265 nm/Gy to gamma radiation dose and a QF of 12,701. Incorporation of QDs into FP microcavities has proven versatile, enabling applications where single-photon sources [

31] are required. In sensing, to further improve the sensitivity of porous silicon microcavity biosensors, water-soluble CdSe/ZnS QDs have been proposed for amplifying the refractive index signal as a consequence of the high refractive index of QDs [

32]. This further highlights the potential of QDs for real-time, portable monitoring and low-detection-limit applications [

33].

2D materials, including graphene and WS₂ monolayers, have been explored in terms of improving the optical properties of FP microcavities. The inclusion of graphene sheets at the interface between cavity and mirror, as is shown in

Figure 2 (b), enhances the absorption of the incident energy by increasing the interaction path lengths of electromagnetic waves within the left-handed material (LHM). LHM refers to a metamaterial with negative permittivity and permeability, which plays a crucial role in a FP cavity as an absorber [

34].

Similarly, some configurations of FP microcavities based on dielectric Bragg mirrors, such as the MgF

2, ZnSe, and graphene monolayer at the interface between cavity and mirror, exhibit exceptional sensitivity, signal-to-noise ratio, and resolution metrics for applications in cancer cell detection. The sensors based on these microcavities have a sensitivity as high as 290 nm/RIU, and a quality factor of 2270.74 [

35]. WS₂ monolayers support plasmonic Fano resonance in FP cavities, further advancing their optical performance [

36]. These advancements meet the growing demand for miniaturized biosensors, particularly those designed for point-of-care cancer detection. Innovative designs, such as graphene-embedded defect one-dimensional photonic crystals, have enabled real-time identification of various cancer cell types, including basal, cervical, and breast cancer cells [

35]. In addition, coupling FP microcavities with metamaterials, e.g., MXenes, at at the interface between cavity and mirror and optimization of the cavity parameters ensure sharp, distinguishable resonance peaks and enhanced sensor performance [

37].

Metal–organic frameworks have also been integrated into FP microcavities. In this case, the sensing benefits from their high specific surface area and customizable functionalities [

38]. These properties of metal–organic frameworks enhance the microcavity interactions with analytes, and the functional groups can target specific molecules. FP microcavities based on metal–organic frameworks are used, e.g., in colorimetric sensing, where variations of the thickness and optical density of the FP film provide precise detection. Another example is humidity sensing [

39,

40]. Thus, the use of metal–organic frameworks further broaden the scope of applications of FP microcavities.

The versatility of FP microcavities in biosensing is augmented through functionalization of the sensing area with receptor molecules. When target biomolecules bind to these receptors, a measurable shift in the resonant response occurs, facilitating the detection of a wide range of biomarkers [

41,

42].

A promising novel sensor not requiring probe pre-modification is an optofluidic microbubble placed inside an FP microcavity. This design combines a high-quality factor (∼10

5), small mode volume (approximately one-sixth of the mode volume of the original FP microcavity), and high robustness (i.e., good tolerance to non-parallelism (5°) and cavity length changes). These features enable an ultrahigh refractive index sensitivity (679 nm/RIU) and an ultrasmall refractive index resolution (∼10

−7 RIU at 950 nm), representing a significant improvement over the original FP microcavity, which had a refractive index resolution of ∼10

−4 RIU. This configuration provides a low detection limit and a wide detection range for biomolecules, e.g., several femtograms per milliliter for IgG and less than a picogram per milliliter for human serum albumin [

2]. Another important example is a hybrid optofluidic microcavity composed of a microsphere and FP microcavities, which is characterized by exceptionally low effective mode volumes (0.3–5.1 μm³) and high-quality factors (from 1×10⁴ to 5×10⁴). This hybrid design leverages the advantages of both components: the microsphere confines light to small mode radius (0.26–0.9 μm) and mode volume, provides beam focusing due to the lensing effect, and mitigates geometrical losses by refracting or reflecting misaligned light [

43]. In this configuration, the microsphere serves as both a waveguide and a lens, enhancing the overall performance of the system. In addition, a convex microlens array structure inside the FP cavity has been proposed, which ensures a 5.6-fold increase in the quality factor than that of the original FP cavity [

44].

Porous silicon microcavities, in particular, have gained much attention for their low cost, easy fabrication, and fine control over the material’s refractive index. Recent developments include the use of aptamers for protein biomarker detection, enhanced by the addition of 3D-printed microfluidic systems with micromixer architectures [

45]. These innovations have improved sensor performance, ensuring detection limits as low as 50 nM. The integration of diverse materials and mechanisms in FP microcavities further extends their research, technological, and medical applications, reinforcing the potential of FP microcavities in advanced sensing and diagnostic technologies.

Furthermore, FP microcavities are integral to compact and stable spectrometer designs. SERS-active materials based on FP microcavities have proven to be two orders of magnitude more sensitive than conventional ones based on silicon substrates [

46]. By addressing challenges related to achieving high spectral resolution and overcoming manufacturing constraints, spectral reconstruction algorithms have been developed. These innovations significantly enhance the resolution and functionality of spectrometers, making them suitable for various high-precision applications.

Recent advancements have also extended the capability of FP microcavity sensing to the degree required for terahertz frequency-domain spectroscopy [

47], further broadening their application scope. The versatility of FP microcavities makes them all the more important as promising tools across a wide range of applications, driving innovation and discovery in science and technology.

4. Plasmonic Microcavity-Based Sensors

Plasmonic materials, particularly gold and silver, are promising for sensing applications due to their capacity for supporting SPR and LSPR, enabling enhanced optical sensitivity and precision. SPR occurs in thin metal films when the frequency of the evanescent wave matches that of the surface plasmons, enabling broadband light confinement [

48]. In contrast, LSPR is induced by electron oscillations confined to metal nanoparticles and is highly sensitive to the size, shape, and composition of the particles, as well as the refractive index of the surrounding medium. Nanoparticles, in particular, offer unique advantages at the molecular level because their small size minimizes bulk effects typical of films. This means that only the bound molecule contributes to the LSPR signal, which makes it possible to detect single molecules [

49,

50]. This makes LSPR ideal for detecting analytes in subwavelength-scale volume. Combination of the advantages offered by the SPR and LSPR effects and the use of 2D materials in plasmonic cavity sensors has been shown to improve a number of performance parameters, such as sensitivity, LOD, and detection range [

51,

52]. This combination has been extensively studied in terms of applications in gas sensing and biosensing, including cancer biomarker detection [

53]. Plasmonic integrated systems are also used for chemical sensing, temperature monitoring [

54], humidity and pressure measurements [

55], as well as food safety and environmental monitoring [

56].

These plasmonic materials have been integrated into different microcavity designs, including plasmonic PCF sensors. PCFs based on plasmonic materials are optical fibers with air channels forming ordered arrays that efficiently guide and confine light by reflecting it internally. These microcavities, with enhanced light–matter interactions, constitute a highly sensitive alternative to conventional fibers. Geometric parameters, such as the channel size, spacing, and the thickness of the plasmonic metal film, significantly affect the wavelength sensitivity.

The sensitivity of PCF SPR sensors is largely determined by the plasmonic material used. Typically, these are silver, gold, aluminum, copper, bismuth, or palladium, with gold standing out for its high chemical stability and a large change in resonant peak upon interaction with the analyte [

55]. Innovative designs of plasmonic PCFs, elaborated with intense use of computational methods, ensure high spectral sensitivity and resolution [

57,

58]. For example, D-type fiber optic sensors are easy to fabricate and allow for the integration of gold films near the core to obtain strong evanescent waves that interact effectively with the surrounding medium, which enhances the biosensor sensitivity [

59].

As noted above, SPR sensor performance can be enhanced by incorporating 2D materials, such as graphene, which strongly interact with biomolecules to significantly increase sensitivity. These SPR sensors detect subtle variations in the refractive index. For instance, a maximum amplitude sensitivity of 14,847.03 RIU

–¹ and an average wavelength sensitivity of 2000 nm/RIU have been demonstrated for graphene-based SPR sensors [

60]. The addition of graphene oxide to gold nanoparticles improves biomolecule adsorption, reducing the LOD to nanogram scale [

61]. Graphene combined with other materials, e.g., magnesium fluoride (MgF₂), has been used to coat PCF SPR sensors. MgF

2 is an ideal material for coatings due to its ability to support a wide wavelength range from ultraviolet to infrared and aids in the excitation of surface plasmon waves, enhancing sensor performance. By adding an MgF

2 layer

, the average wavelength sensitivity and amplitude sensitivity have been increased from 2500 nm/RIU

−1 to 4000 nm/RIU

−1 and from 12,155.2 RIU

−1 to 16,905.15 RIU

−1, respectively. This sensor has been proposed for detecting aqueous solutions [

62]. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) nanosheets are another example of a 2D material enhancing SPR sensor sensitivity [

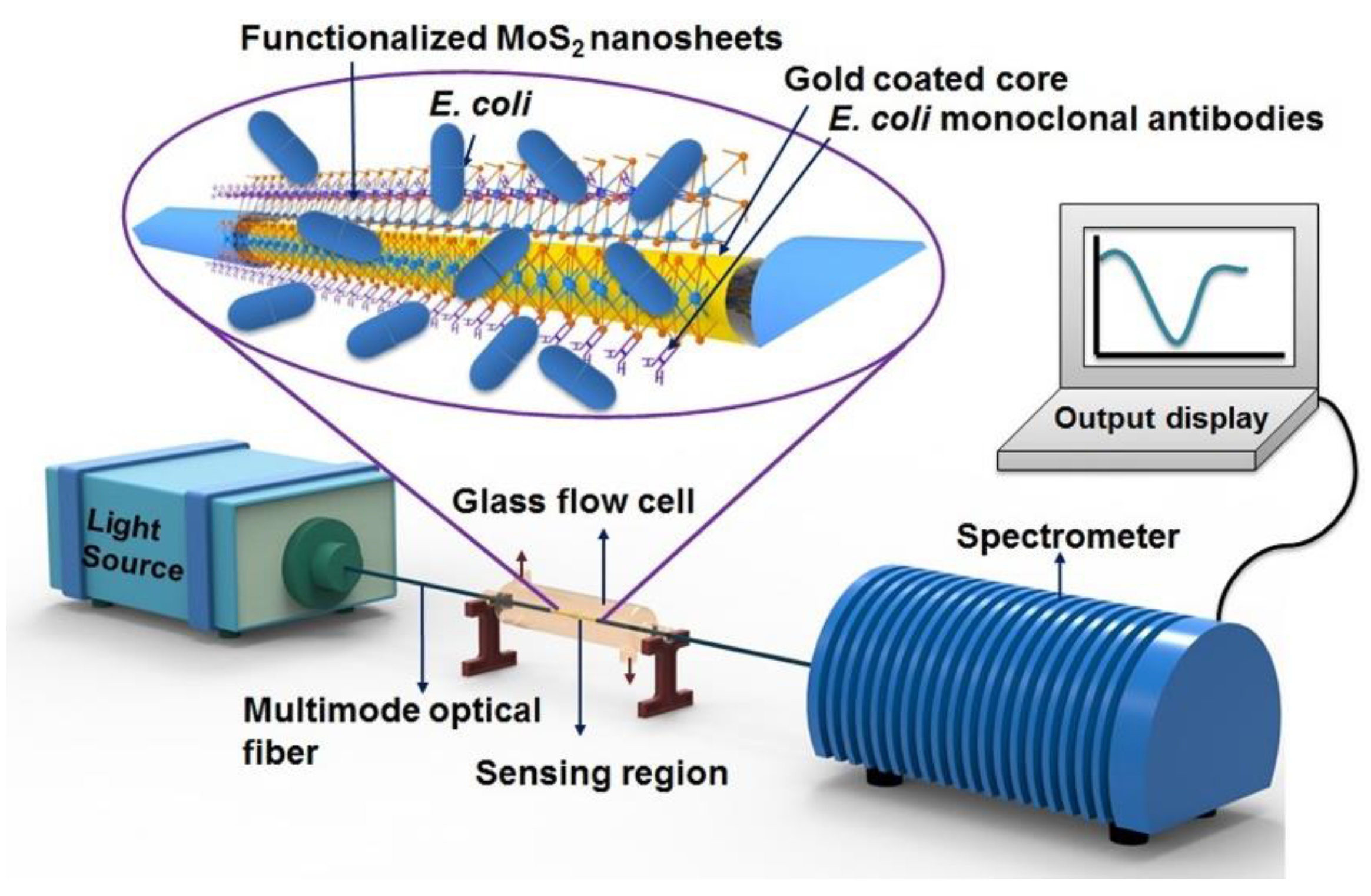

63]. The MoS

2 nanosheets are anchored to the gold layer surface and their function is to help the immobilization of monoclonal antibodies through hydrophobic interactions. This strategy was used for the quantitative analysis of E. coli bacteria with a sensitivity of 3135 nm/RIU (

Figure 3).

Another approach to enhancing the performance of plasmonic sensors is to protect the plasmon layer from oxidation. For example, coating of the silver layer with phosphorene has been reported to increase the wavelength sensitivity to 1800 nm/RIU within a refractive index range of 1.39–1.45 and the maximum amplitude sensitivity to 268 RIU

-⁻¹, with an analyte

refractive index of 1.40 [

64]. Other materials, such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂), are also employed to protect silver films from oxidation and enhance the SPR effect [

65].

The combination of various prospective materials discussed above in a single sensor architecture leads to additional improvements of plasmonic sensors. For instance, combining gold as the primary plasmonic layer with graphene and Ti₃C₂Tx-MXene increases the sensitivity and stability, facilitating early detection of cancer biomarkers at small concentrations [

66]. Carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide amplify signals, improve sensitivity, and provide high chemical stability in fiber-optic-based biosensors, with carbon nanotubes promoting molecularly imprinted polymer formation and graphene oxide enhancing the interaction between the SPR and the molecules [

67,

68]. QDs are incorporated into functionalized sensing systems to improve the detection of antibiotics, biomarkers, and metal ions [

15]. For example, CsPbBr₃ QDs enhance the energy transfer from the core mode of PCFs to the SPR mode of the metal, boosting sensing performance while preserving the narrow full width at half maximum [

69].

A recent breakthrough is an immunosensor based on a fiber-optic Fabry–Pérot interferometer for single-molecule detection that combines AuNP-embedded graphene oxide with a D-shaped optic fiber to address the challenges of the low spectral contrast and limited area of contact between light and material. The sensitivity and selectivity of the sensor are improved due to the localized confinement of the electromagnetic field of gold nanoparticles, ensuring an ultrahigh refractive index sensitivity of 583,000 nm/RIU and an LOD of 17.1 ag/mL in the case of progastrin-releasing peptide detection [

70]. Similarly, combining ZnO nanowires and WS₂ nanosheets provides a wide surface area for functionalization and antibody/nanoparticle immobilization in plasmon wave-based fiber sensors, providing a sensitivity of detection of 1.32 ng/mL and an LOD of 84 pg/mL for an alpha-fetoprotein solution at concentrations below 1000 ng/mL [

71,

72]. GO-enhanced sensors have been found to be 2.5 times more sensitive than gold-coated fiber optic sensors [

73].

Despite these advances, challenges remain in scaling up the fabrication of PCF sensors for commercial use due to the high production costs and complexity. Researchers are continually exploring ways to simplify the sensor design in order to facilitate miniaturization and increase cost-effectiveness while ensuring a high sensitivity for leveraging the potential of plasmonic sensors in medical diagnosis, environmental monitoring, and other fields. Recent trends in these developments include the use of microstructured fibers, optimization of the sensor geometry and fabrication of hybrid systems.

Combining microcavity and plasmonic effects has been demonstrated to ensure ultrasensitive detection. For example, a hybrid microcavity-based SERS sensor provides detection limits of 3.16 pg/mL for cardiac troponin I and 4.27 pg/mL for creatine kinase MB, outperforming the traditional fluorescence and ELISA techniques [

74]. Recent SERS developments in microfluidic systems have enabled femtogram-level detection for the biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease and Epstein–Barr virus [

75,

76]. SERS enables ultrasensitive detection of analytes down to single molecules, using a metal–dielectric nanocavity engineered from the SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein and silver. By enhancing the quality factor of the cavity with a silver shell, a sub-femtogram sensitivity for viral antigen detection is achieved without the use of Raman reporter molecules. This label-free method allows high-performance optical detection and conformational analysis of viral proteins at physiologically relevant levels [

77].

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering analysis is a powerful analytical technique offering remarkable sensitivity that allows single-molecule detection. However, it has substantial limitations. One key challenge is the need for reproducibility of the SERS signals, because the technique relies on the quality and uniformity of nanostructured substrates, which can vary during fabrication. Commonly used substrates, such as silver, are prone to oxidation and degradation, which reduce the performance over time. SERS also struggles with complex sample matrices, where nonspecific adsorption, interfering signals, or matrix effects may hinder accurate detection. Additionally, some types of molecules with weak Raman activity or without strong affinity to SERS-active surfaces (e.g., nonpolar/hydrophobic molecules), are difficult to detect. The performance also depends on environmental factors, such as pH, temperature, and ionic strength. The high cost of SERS analysis and the complexity of substrate preparation also limit its scalability for routine applications.

The ongoing development of novel designs increases the versatility of plasmonic microcavity-based sensors, enabling capabilities such as single-molecule detection. However, further research is needed to address manufacturing challenges and improve scalability.

5. Whispering-Gallery Mode Microcavities

Whispering-gallery mode microcavities, such as microdisks, microtoroids, and microspheres, are distinguished by their high-quality factors, high sensitivity, and long photon confinement times. These properties make them ideal for advanced light–matter interaction studies and a wide range of sensing applications, such as the detection of biomolecules and chemical substances (including gases) and temperature, pressure, humidity, and strain sensing. These innovations demonstrate the potential of WGM microcavities in revolutionizing precision sensing across various research and industrial applications.

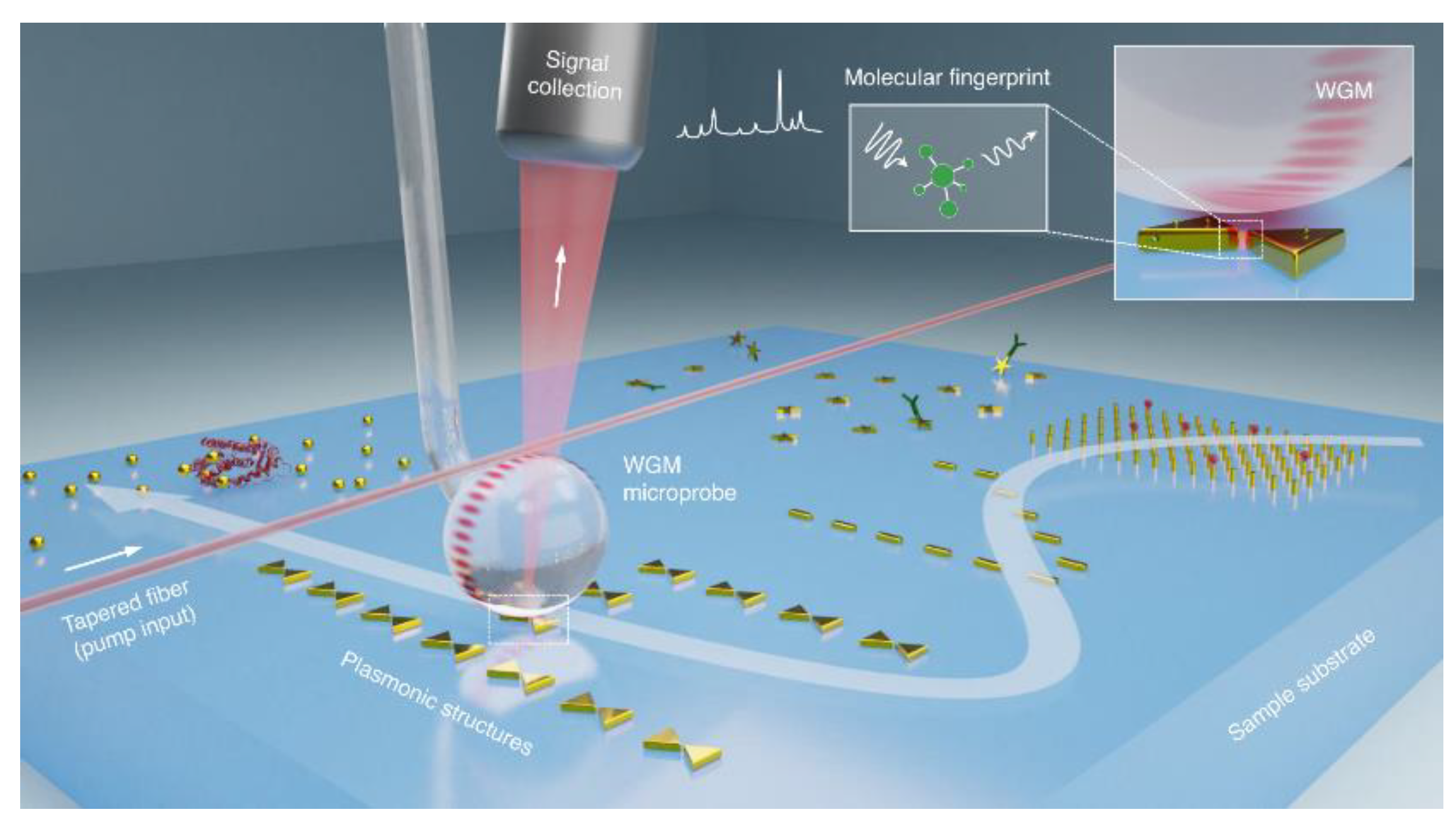

When combined with plasmonic nanoparticles or thin metal layers, WGM resonators significantly enhance light–matter coupling. This configuration has proven useful in detecting ultrasmall virus particles, such as the MS2 RNA virus, even at very low concentrations [

78]. Plasmonic-enhanced WGM systems are particularly valuable in cavity quantum electrodynamics, single-photon sources, and sensing because they enable signal enhancement beyond the detection limits of conventional biosensors. The combination of whispering-gallery modes and nanoplasmonics can ensure an almost two times more intense Raman spectroscopy signal for sensitive molecular fingerprinting compared with the traditional purely plasmonic approach [

79] (

Figure 4). Moreover, nanoparticles deposited on the surface of a WGM microcavity can enhance Rayleigh scattering, facilitating effective WGM coupling [

80].

Originally fabricated from silica, WGM microcavities have also been made of polymers in recent years. Polymers offer significant advantages, such as low cost, adaptability, and compatibility with diverse fabrication techniques [

81]. Their inherent elasticity makes them suitable for strain or deformation sensing, and their tunable refractive indices enable the integration of bioactive molecules, including antibodies, enzymes, and DNAs. Such functionalized WGM sensors detect changes in refractive index upon target molecule binding, producing strong optical signals. For example, microring resonators fabricated by femtosecond laser two-photon photopolymerization (TPP) have a temperature sensitivity of 9.51 × 10

−2 nm/°C and a refractive index sensitivity of 12.50 nm/RIU, which shows their potential for precise sensing applications [

82]. However, photopolymerization faces some challenges, such as the need for specific light-sensitive monomers and restricted light penetration depths, which may limit its applicability in some sensor designs. Optimizing the designs, such as incorporating tapered waveguides into polymer ring resonators or increasing the undercut size in WGM microdisks, enhances the sensitivity and decreases the detection threshold. The use of biodegradable materials for healthcare applications, particularly in transient sensing devices for personalized diagnosis, represents a growing area of research. The use of polymers further advances the optical sensor technology, with ongoing efforts to address challenges related to stability and performance under varying environmental conditions. Innovations in fabrication methods, such as drop-on-demand inkjet printing for optical gas sensors employing polymer WGM microcavities, have enabled the integration of multiple sensing materials on a single microchip. These systems have quality factors exceeding 10

6 [

83].

The incorporation of 2D materials represents another feasible way to improve the performance of WGM-based optical devices and promote the development of novel photonic and optoelectronic devices employing enhanced light–matter interaction [

84]. Functionalizing over-modal microcavities with single-layer graphene has been used to engineer microcomb sensors with high chemical selectivity and sensitivity [

85]. Similarly, MXene nanosheets, such as Nb

2C ones, have been integrated into WGM microcavities to enhance electrochemiluminescence (ECL), enabling sensitive detection of miRNA in triple-negative breast cancer. Here Nb

2C nanosheets are MXene-derived luminescent materials and SiO₂ optical microspheres are assembled on the electrode surface to form a whispering gallery mode (WGM) optical microcavity, which localized photons and amplified the ECL signal [

86]. In addition, the possibility of multimode sensing using WGM microcavities has been demonstrated, which further enhances the resolution and dynamic range of sensing [

87].

These advances, coupled with continuous innovations in materials, optimized geometries and fabrication techniques, further expand their applicability and improve their performance, making them indispensable tools in next-generation sensing systems.

6. The Advantages and Drawbacks of Different Microcavity Designs for Sensing Applications

Fabry–Pérot microcavities have a larger functional surface area compared to other optical microcavity designs, enabling enhanced sensor performance upon functionalization with specific receptors or nanomaterials. However, whereas they have a higher quality factor than plasmonic cavities, their light confinement volume is significantly larger than that of nanoparticle-based microcavities, precluding the detection of single molecules. This limitation could be overcome by making the reflective surfaces convex or concave or by incorporating an array of convex microlenses into the FP microcavity [

44]. Additionally, spectral tuning using (electro)mechanical positioners has been explored as a method for precisely adjusting the spacing between the mirrors [

31,

88]. Some materials, such as porous silicon, offer tunability to meet various detection requirements and are cost-effective and simple to manufacture. However, their scalability remains a problem because they are sensitive to the manufacturing conditions, such as resistivity of silicon wafers, temperature, etching solutions. Further research is needed to optimize microcavity designs, refine the adjustment of the parameters, and enhance long-term stability.

In contrast, SPR-based microcavities have small mode volumes, enabling single-molecule detection. Although their quality factors are often low because of high losses in the metal, combination with 2D nanomaterials increases their capacity for functionalization and biocompatibility. These advantages are particularly obvious in the case of PCFs, where electric field confinement is further optimized. In particular, D-shaped fibers are easy to fabricate and functionalize while retaining a high sensitivity. Novel designs of these systems offer improved adaptability for a variety of detection applications. Nevertheless, challenges persist in scaling up their production because precise and controlled manufacturing of each component is required.

Regarding WGM microcavities, despite their exceptional sensitivity and resolution, several limitations hinder their broader application. Tracking specific modes confines sensing performance to a single data channel, complicating multimodal data collection. The limited dynamic range of WGM sensors poses an issue because mode shifts beyond the laser scanning range disrupt measurements; on the other hand, extending the range often sacrifices resolution. Furthermore, noise interference reduces the accuracy of detecting subtle changes, whereas the necessity of reliably tracking the same mode interferes with reproducibility and standardization. Addressing these issues is critical for expanding the applicability of WGM sensors [

87].

In conclusion, while Fabry–Pérot, SPR-based, and WGM microcavities each offer unique advantages in sensor performance, they also face challenges that limit their broader application. Fabry–Pérot microcavities have large functional surfaces but struggle with single-molecule detection due to their larger light confinement volume. SPR-based microcavities excel at single-molecule detection but face issues with low quality factors and scalability. Particularly, SERS techniques have been optimized for detection of ultralow concentrations, even in complex samples, through the electromagnetic field confinement. WGM microcavities provide high sensitivity and resolution, yet are limited by mode tracking, dynamic range, and noise interference. Continued research is needed to address these limitations and improve the scalability, sensitivity, and reliability of these technologies for more diverse applications.

7. Prospects

Functionalized microcavities have proven remarkably versatile in biosensing, environmental monitoring, chemical and physical sensing, and other applications. The use of novel materials and approaches, including artificial intelligence [

89], has significantly enhanced sensor performance, increasing sensitivity, selectivity, and the capability for detecting low analyte concentrations in complex environments. This is particularly critical for cancer diagnosis [

35]. The combination of different microcavity configurations and techniques, such as SERS-based sensing integrated with Fabry–Pérot, plasmonic microcavity sensing or WGM, within a single sensor helps overcoming many limitations, leading to synergistic enhancement of performance.

Recent advances in fabrication methods and technologies allow better control over the sizes and geometric parameters, which are crucial for sensor designs where performance is highly sensitive to dimensional accuracy. Despite these improvements, even more precise methods are required to achieve consistent performance. Miniaturization and combination with microfluidics are essential for adapting sensors to real-world environments, enabling lab-on-chip configurations suitable for commercial applications. However, practical implementation remains a challenge requiring new solutions for cost reduction, scalability, and user-friendliness.

Whispering-gallery mode sensors have already been demonstrated to have high potential in biological detection. However, their extreme sensitivity to environmental factors necessitates strategies for noise reduction, such as advanced data processing algorithms. Simplifications of design have resulted in fibreless systems [

90], with polymers emerging as viable materials for cost-effective manufacturing. Miniaturized spectrometers are being developed to further enhance the portability and applicability of the sensors. In the case of FP cavities, optimizing fabrication processes to improve the quality factor and reproducibility remains an essential goal. Similarly, PCFs require more precise manufacturing to meet the optical requirements necessary for homogeneity and good performance in assembling nanomaterials.

Artificial intelligence plays a transformative role in improving sensor performance, enabling the processing of complex signals and recognition of the patterns that would otherwise be undetectable. By combining advantages of different configurations, e.g., balancing the optimal confinement volumes and quality factors, researchers are pushing the boundaries of multiplexed and multimodal detection, providing a wider range of analyte detection capabilities in the same device. For example, the integration of machine learning has been used for predicting the resonant peak wavelength of more complex systems such as 2D photonic crystal biosensor employed for cancer diagnosis. The machine learning models includes repeating training, testing, and optimization resonant wavelength with dependent and independent features of a 2D PC biosensor system [

91]. In addition, machine learning has been used to predict reflectance results, which can be employed to optimize designs and reduce the simulation time [

92]. The use of neural network also contributes to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of sensor, potentially revolutionizing hybrid optical–digital systems [

93,

94]. Hybrid sensor technologies integrating microfluidics [

5], artificial intelligence, and the Internet of things pave the way for next-generation lab-on-chip devices, tattoo-based sensors [

95], and other groundbreaking innovations.

Spectral resolution is another key characteristic in sensing performance. Sensitivity alone does not ensure good performance if the system cannot detect small spectral shifts due to noise. Recent developments in multimode optical microcavity sensors have enabled multiplexed detection by using several resonant modes simultaneously, effectively acting as multiple sensors within a single device [

96]. Here, machine learning-based multimode optical microcavity sensors employ algorithms to analyze the multimode shift data of the sensors, enhancing the system performance by enabling efficient data fusion and pattern recognition. This approach reduces human error and accelerates analysis.

Efforts towards miniaturizing sensor devices, such as computational spectrometers with spectral encoding and reconstruction algorithms [

97], will enhance their portability and accessibility. Additionally, the development of nontoxic, biodegradable materials will support sustainability and broader adoption across diverse applications. Future research should also focus on multichannel detection, hybrid sensors, and balance between performance parameters without sacrificing accuracy, with robust, scalable, and user-friendly sensor systems as the ultimate goal.

8. Summary and Outlook

Nanomaterials are transforming current sensing technologies by significantly enhancing the performance of sensors, making use of the unique properties of these materials, such as a large surface area accessible for functionalization, efficient electric field confinement, and strong interactions with analytes. Optical microcavity sensors integrated with nanomaterials offer exceptional sensitivity, resolution, and selectivity, enabling the detection of analytes at very low concentrations. Nanomaterials, including nanorods, nanowires, and nanocomposites, play crucial roles in improving sensor performance. Nanorods and nanowires enhance biocompatibility and provide a larger surface area for antibody functionalization, whereas nanocomposites facilitate the LSPR effect, further boosting the sensing capability. To increase specificity, optical fibers coated with engineered nanomaterials can be functionalized with antibodies against the target analytes or markers. The integration of machine learning algorithms allows more accurate data interpretation, making the devices more versatile and efficient by overcoming the limitations of traditional methods. Combining nanophotonic structures with microfluidics offers compact, effective solutions for bioanalytical applications, enhancing both performance and usability. Nanocrystals, such as QDs, are driving advancements in designing highly sensitive, flexible devices. Future trends in the development of these technologies are expected to focus on improving performance and scalability and facilitating their integration into multifunctional systems. Although functionalized optical microcavities have already demonstrated remarkable sensitivity, further efforts are called for to achieve miniaturization, sufficient cost-effectiveness, and applicability to real-time monitoring, and to ultimately expand their practical use in various fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.N., writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, P.S. and E.G.; general revision, P.S. and I.N.; supervision and funding acquisition, I.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the RF Ministry of Science and Higher Education Federal grant no. 075-15-2024-556 for conducting major scientific projects in priority areas of scientific and technological development (dated April 25, 2024) in the part of the work related to design and development of functional microcavities for optoelectronics and by the Russian Science Foundation grant no. 23-75-30016 in the part of the work related to microcavities design and applications to advanced biosensing and diagnostics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vladimir Ushakov for proofreading the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The company Life Improvement by Future Technologies (LIFT) Center had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kim, H.S.; Jun, S.W.; Ahn, Y.H. Developing a Novel Terahertz Fabry–Perot Microcavity Biosensor by Incorporating Porous Film for Yeast Sensing. Sensors 2023, 23, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Luo, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; et al. Highly Sensitive, Modification-Free, and Dynamic Real-Time Stereo-Optical Immuno-Sensor. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2023, 237, 115477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Arakawa, T.; Higo, A.; Ishizaka, Y. Silicon Microring Resonator Biosensor for Detection of Nucleocapsid Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Sensors 2024, 24, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.S.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, S. Gold-Immobilized Photonic Crystal Fiber-Based SPR Biosensor for Detection of Malaria Disease in Human Body. IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21, 17800–17807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granizo, E.; Kriukova, I.; Escudero-Villa, P.; Samokhvalov, P.; Nabiev, I. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics in Strong Light–Matter Coupling Systems. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil-Jradi, S.; Jradi, S.; Plain, J.; Adam, P.-M.; Bijeon, J.-L.; Royer, P.; Bachelot, R. Micro/Nanoporous Polymer Chips as Templates for Highly Sensitive SERS Sensors. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 7837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Zhu, H.; Lin, M.; Wang, F.; Hong, L.; Masson, J.-F.; Peng, W. Comparative Study of Block Copolymer-Templated Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Optical Fiber Biosensors: CTAB or Citrate-Stabilized Gold Nanorods. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2021, 329, 129094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makela, M.; Lin, Z.; Coté, G.L.; Lin, P.T. Fluorescence Enhanced Biomolecule Detection Using Direct Laser Written Micro-Ring Resonators. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 174, 110629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Fu, H.; Chu, P.K.; Liu, C. Recent Advances of Optical Fiber Biosensors Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance: Sensing Principles, Structures, and Prospects. Sens. Diagn. 2024, 3, 1369–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Alsalman, O. Design and Development of Graphene-Based Double Split Ring Resonator Metasurface Biosensor Using MgF2-Gold Materials for Blood Cancer Detection. Opt Quant Electron 2024, 56, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.H.; Wang, H.M.; Kasim, J.; Fan, H.M.; Yu, T.; Wu, Y.H.; Feng, Y.P.; Shen, Z.X. Graphene Thickness Determination Using Reflection and Contrast Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 2758–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Zhong, H.; Xu, Z.; He, T.; Kim, J.S.; Han, S.; Kim, S.; Park, S.; Shen, Y.; Gong, M.; et al. Functionalizing Nanophotonic Structures with 2D van Der Waals Materials. Nanoscale Horiz. 2023, 8, 1345–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Su, X. Recent Advances and Applications in QDs-Based Sensors. Analyst 2011, 136, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Choi, T.; Liu, A.; Zhu, H.; Noh, Y.-Y. Printed Quantum Dot Photodetectors for Applications from the High-Energy to the Infrared Region. Nano Energy 2024, 125, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Lin, L. Recent Advances in Quantum Dots-Based Biosensors for Antibiotics Detection. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2022, 12, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, R.; Gorai, P.; Shrivastav, A.; Pathak, A. Label-Free Biochemical Sensing Using Processed Optical Fiber Interferometry: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, acsomega.3c03970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, B.; Kumar, S.; Nedoma, J.; Martinek, R.; Marques, C. Advancements in Optical Biosensing Techniques: From Fundamentals to Future Prospects. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 091102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nifontova, G.; Gerasimovich, E.; Fleury, F.; Sukhanova, A.; Nabiev, I. Photonic Crystal Surface Mode Imaging for Multiplexed Real-Time Detection of Antibodies, Oligonucleotides, and DNA Repair Proteins. EPJ Web Conf. 2023, 287, 03007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, B.; Kumar, N.; Taya, S.A. Design and Analysis of Tunable Multichannel Transmission Filters with a Binary Photonic Crystal of Silver/Silicon. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2022, 137, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Suthar, B.; Nayak, C.; Bhargava, A. Analysis of a Gas Sensor Based on One-Dimensional Photonic Crystal Structure with a Designed Defect Cavity. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 065506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.N.; Tran, H.N.Q.; Lim, S.Y.; Abell, A.D.; Law, C.S.; Santos, A. Detection of Volatile Organic Compounds through Spectroscopic Signatures in Nanoporous Fabry–Pérot Optical Microcavities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 24961–24975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzempek, K.; Jaworski, P.; Tenbrake, L.; Giefer, F.; Meschede, D.; Hofferberth, S.; Pfeifer, H. Photothermal Gas Detection Using a Miniaturized Fiber Fabry-Perot Cavity. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 401, 135040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, R.B.; Saara, K.; Sharan, P. Detection of Oral Cancerous Cells Using Highly Sensitive One-Dimensional Distributed Bragg’s Reflector Fabry Perot Microcavity. Optik 2021, 244, 167599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, W.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Yi, Z.; Sun, T.; Wu, P.; Zeng, Q.; Raza, R. Tunable Metamaterial Absorption Device Based on Fabry–Perot Resonance as Temperature and Refractive Index Sensing. Optics and Lasers in Engineering 2024, 181, 108368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, Z.A.; Al-Dossari, M.; Hendy, A.S.; Zayed, M.; Aly, A.H. Gamma Radiation Detector Using Cantor Quasi-Periodic Photonic Crystal Based on Porous Silicon Doped with Polymer. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2024, 38, 2450409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, A.M.; Ahmed, A.M.; Aly, A.H.; Eissa, M.F.; Tammam, M.T. Detection of Low-Concentration Heavy Metal Exploiting Tamm Resonance in a Porous TiO2 Photonic Crystal. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26050–26058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, S.; Tokas, R.B.; Thakur, S.; Udupa, D.V. Rabi-like Splitting and Refractive Index Sensing with Hybrid Tamm Plasmon-Cavity Modes. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 175104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T.; De Leon, I.; Zaccaria, R.P.; Qian, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, G. Strong Coupling of Tamm Plasmons and Fabry-Perot Modes in a One-Dimensional Photonic Crystal Heterostructure. Phys. Rev. Applied 2022, 18, 014056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankita; Suthar, B.; Bissa, S.; Bhargava, A. Revolutionizing Optical Biosensor with Nanocomposite/Defect/Nanocomposite Multilayer 1D Photonic Crystals. Opt Quant Electron 2024, 56, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, N.R.; Amiri, I.S.; Taya, S.A.; Olyaee, S.; Udaiyakumar, R.; Pasumpon Pandian, A.; Joseph Wilson, K.S.; Mahalakshmi, P.; Yupapin, P.P. Enhanced Sensitivity of Cancer Cell Using One Dimensional Nano Composite Material Coated Photonic Crystal. Microsyst Technol 2019, 25, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Rao, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Song, C.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, K.; Chen, P.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; et al. Tunable Quantum Dots in Monolithic Fabry-Perot Microcavities for High-Performance Single-Photon Sources. Light Sci Appl 2024, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Lv, X.; Huang, X. Enhanced Biosensor Based on Assembled Porous Silicon Microcavities Using CdSe/ZnS Quantum Dots. IEEE Photonics J. 2021, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, F.; Vahedi, A.; Hagipour, S. Ternary One-Dimensional Photonic Crystal Biosensors for Efficient Bacteria Detection: Role of Quantum Dots and Material Combinations. Physica B: Condensed Matter 2025, 698, 416766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elblbeisi, M.; Taya, S.A.; Almawgani, A.H.M.; Hindi, A.T.; Alhamss, D.N.; Colak, I.; Patel, S.K. Absorption Properties of a Defective Binary Photonic Crystal Consisting of a Metamaterial, SiO2, and Two Graphene Sheets. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 1431–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Pukhrambam, P.D.; Wu, F.; Belhadj, W. Graphene-Based 1D Defective Photonic Crystal Biosensor for Real-Time Detection of Cancer Cells. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, B.; Xiao, S. WS2 Monolayer in Fabry–Perot Cavity Support for Plasmonic Fano Resonance. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Van Nguyen, C.; Pukhrambam, P.D.; Dhasarathan, V. Employing Metamaterial and Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Material for Cancer Cells Detection Using Defective 1D Photonic Crystal. Opt Quant Electron 2023, 55, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, K.; Jiang, Y.; Qin, P.; Chen, Y.; Heinke, L. A Colorimetric Label-Free Sensor Array of Metal–Organic-Framework-Based Fabry–Pérot Films for Detecting Volatile Organic Compounds and Food Spoilage. Adv Materials Inter 2023, 10, 2300329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Y.; Li, H.; Lu, Z.; Yang, L. Fabry–Pérot Cavity Based on Metal–Organic Framework/Graphene Oxide Heterostructure Membranes for Humidity Sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 6148–6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Yang, W.; Huang, M. Integrated and Robust Fabry–Perot Humidity Sensor Based on Metal–Organic Framework onto Fiber-Optic Facet. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 12906–12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, D.; Kim, S. Demonstration of a Label-Free and Low-Cost Optical Cavity-Based Biosensor Using Streptavidin and C-Reactive Protein. Biosensors 2020, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypabekova, M.; Hagemann, A.; Kleiss, J.; Morlan, C.; Kim, S. Optimizing an Optical Cavity-Based Biosensor for Enhanced Sensitivity. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 25911–25918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Tong, L.; Fan, X. High-Q, Low-Mode-Volume Microsphere-Integrated Fabry–Perot Cavity for Optofluidic Lasing Applications. Photon. Res. 2019, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Luo, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, X. High-Q Fabry-Pérot Cavity Based on Micro-Lens Array for Refractive Index Sensing. Photonic Sens 2024, 14, 240414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awawdeh, K.; Buttkewitz, M.A.; Bahnemann, J.; Segal, E. Enhancing the Performance of Porous Silicon Biosensors: The Interplay of Nanostructure Design and Microfluidic Integration. Microsyst Nanoeng 2024, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, P.; Li, Z. High Performance SERS Boosting by Fabry- Pérot Cavities of Silica-Gold-Silicon Multilayers. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 42569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, K.; Fahad, A.K.; Wang, H.; Zheng, X.; Ruan, C. The Enhancement Detection Method Based on the Fabry–Pérot Cavity Using Terahertz Frequency-Domain Spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2025, 327, 125293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausaite-Minkstimiene, A.; Popov, A.; Ramanaviciene, A. Ultra-Sensitive SPR Immunosensors: A Comprehensive Review of Labeling and Interface Modification Using Nanostructures. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 170, 117468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Das, A.; Zhang, X.; Schatz, G.C.; Sligar, S.G.; Van Duyne, R.P. Resonance Surface Plasmon Spectroscopy: Low Molecular Weight Substrate Binding to Cytochrome P450. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11004–11005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya, A.N. Plasmonic Nanoarchitectures for Single-Molecule Explorations: An Overview. Advanced Photonics Research 2022, 3, 2100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Sharan, P. Effect of 2-D Nanomaterials on Sensitivity of Plasmonic Biosensor for Efficient Urine Glucose Detection. Front. Mater. 2023, 9, 1106251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Gupta, V.; Choudhary, K.; Kumar, S. Two-Dimensional Materials-Based Plasmonic Sensors for Health Monitoring Systems—A Review. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 11324–11335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaity, A.C. Highly Sensitive Photonic Crystal Fiber Biosensor Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance for Six Distinct Types of Cancer Detection. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 1891–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-T.C.; Chen, S.-H.; Huang, H.J.; Kooh, M.R.R.; Lim, C.M.; Thotagamuge, R.; Mahadi, A.H.; Chau, Y.-F.C. Improving Temperature-Sensing Performance of Photonic Crystal Fiber via External Metal-Coated Trapezoidal-Shaped Surface. Crystals 2023, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.S.; Kumar, D.; Pandey, B.P.; Kumar, S. Advances in Photonic Crystal Fiber-Based Sensor for Detection of Physical and Biochemical Parameters—A Review. IEEE Sensors J. 2023, 23, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatani, S.; Biney, J.; Faramarzi, V.; Jabbour, G.; Park, J. Advances in Plasmonic Photonic Crystal Fiber Biosensors: Exploring Innovative Materials for Bioimaging and Environmental Monitoring. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202401265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hou, S.; Xie, C.; Wu, G.; Yan, Z. High-Performance Photonic Crystal Fiber Biosensor Based on Surface Plasmon Resonance for Early Cancer Detection. Plasmonics 2024, 19, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yao, J. Highly Sensitive Photonic Crystal Fiber Optic Sensor for Cancer Cell Detection. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, Y.; Qi, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.; Li, Y. Recent Advance on Fiber Optic SPR/LSPR-Based Ultra-Sensitive Biosensors Using Novel Structures and Emerging Signal Amplification Strategies. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 175, 110783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.K.; Mollah, Md.A.; Hassan, Md.Z.; Gomez-Cardona, N.; Reyes-Vera, E. Graphene-Coated Highly Sensitive Photonic Crystal Fiber Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Aqueous Solution: Design and Numerical Analysis. Photonics 2021, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Song, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, W.-M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.-Z.; Wang, B.-T.; Dai, Z.-X. Ultra-High Sensitivity SPR Fiber Sensor Based on Multilayer Nanoparticle and Au Film Coupling Enhancement. Measurement 2020, 164, 108083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, A.; Rash-Ahmadi, S. A Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Based on Photonic Crystal Fiber Composed of Magnesium Fluoride and Graphene Layers to Detect Aqueous Solutions. Opt Quant Electron 2024, 56, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Tiwari, U.K.; Pal, S.S.; Sinha, R.K. Rapid Detection of Escherichia Coli Using Fiber Optic Surface Plasmon Resonance Immunosensor Based on Biofunctionalized Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Nanosheets. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2019, 126, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajiani, T.; Shirkani, H.; Sadeghi, Z. Surface Plasmon Resonance Photonic Crystal Fiber Biosensor: Utilizing Silver-Phosphorene Nanoribbons for Near-IR Detection. Optics Communications 2024, 569, 130801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Z.; Shang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yan, W. High Sensitivity Refractive Index Sensor Based on TiO2-Ag Double-Layer Coated Photonic Crystal Fiber. Plasmonics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, A.J.; Maheshwari, R.U.; Pandey, B.K.; Pandey, D. Ultra-Sensitive Photonic Crystal Fiber–Based SPR Sensor for Cancer Detection Utilizing Hybrid Nanocomposite Layers. Plasmonics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspita, I.; Irawati, N.; Madurani, K.A.; Kurniawan, F.; Koentjoro, S.; Hatta, A.M. Graphene- and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes-Coated Tapered Plastic Optical Fiber for Detection of Lard Adulteration in Olive Oil. Photonic Sens 2022, 12, 220411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lin, W.; Xu, P.; Chen, L.; Meng, W.; Hu, X.; Qu, H.; Cui, Y.; Sun, J. FM-Level Detection of Glucose Using a Grating Based Sensor Enhanced With Graphene Oxide. J. Lightwave Technol. 2023, 41, 4145–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Ye, H.; Ding, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, X. Refractive Index Sensing Simulations of CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots/Gold Bilayer Coated Triangular-Lattice Photonic Crystal Fibers. Photonic Sens 2022, 12, 220309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Yao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Tian, J. Fiber-Optic Immunosensor Based on a Fabry–Perot Interferometer for Single-Molecule Detection of Biomarkers. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 2024, 255, 116265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Singh, R.; Zhang, B.; Kumar, S.; Li, G. S-Tapered WaveFlex Biosensor Based on Multimode Fiber and Seven-Core Fiber Composite Structure for Detection of Alpha-Fetoprotein. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 4480–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Singh, R.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.-Z.; Min, R.; Tosi, D.; Zhang, B.; Kumar, S. Development of W-Type Four-Core Fiber-Based WaveFlex Sensor for Enhanced Detection of Shigella Sonnei Bacteria Using Engineered Nanomaterials. J. Lightwave Technol. 2024, 42, 5055–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasu, P.T.; Noor, A.S.M.; Shabaneh, A.A.; Yaacob, M.H.; Lim, H.N.; Mahdi, M.A. Fiber Bragg Grating Assisted Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor with Graphene Oxide Sensing Layer. Optics Communications 2016, 380, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Lei, M.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Wang, R. Microcavity-Based SERS Chip for Ultrasensitive Immune Detection of Cardiac Biomarkers. Microchemical Journal 2021, 171, 106875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Xu, C. Visual/Quantitative SERS Biosensing Chip Based on Au-Decorated Polystyrene Sphere Microcavity Arrays. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2023, 388, 133869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shi, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Luo, C.; Hua, J.; Feng, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Xu, C. Construction of a Microcavity-Based Microfluidic Chip with Simultaneous SERS Quantification of Dual Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Talanta 2023, 261, 124677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarychev, A.K.; Sukhanova, A.; Ivanov, A.V.; Bykov, I.V.; Bakholdin, N.V.; Vasina, D.V.; Gushchin, V.A.; Tkachuk, A.P.; Nifontova, G.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; et al. Label-Free Detection of the Receptor-Binding Domain of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein at Physiologically Relevant Concentrations Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Biosensors 2022, 12, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannur Nanjunda, S.; Seshadri, V.N.; Krishnan, C.; Rath, S.; Arunagiri, S.; Bao, Q.; Helmerson, K.; Zhang, H.; Jain, R.; Sundarrajan, A.; et al. Emerging Nanophotonic Biosensor Technologies for Virus Detection. Nanophotonics 2022, 11, 5041–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, W.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L. A Whispering-Gallery Scanning Microprobe for Raman Spectroscopy and Imaging. Light Sci Appl 2023, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, Q.; Zhao, D.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, L. Review of Different Coupling Methods with Whispering Gallery Mode Resonator Cavities for Sensing. Optics & Laser Technology 2023, 159, 108955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Yang, S.; Shi, R.; Fu, Y.; Su, J.; Wu, C. Polymer Waveguide Coupled Surface Plasmon Refractive Index Sensor: A Theoretical Study. Photonic Sens 2020, 10, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Men, L.; Chen, Q. Femtosecond Laser Fabricated Polymer Microring Resonator for Sensing Applications. Electron. lett. 2018, 54, 888–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianki, M.-A.; Guertin, R.; Lemieux-Leduc, C.; Peter, Y.-A. Suspended Whispering Gallery Mode Resonators Made of Different Polymers and Fabricated Using Drop-on-Demand Inkjet Printing for Gas Sensing Applications. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 420, 136460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Yang, S.; Huang, G.; Mei, Y. 2D-Material-Integrated Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microcavity. Photon. Res. 2019, 7, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yan, G.; Zhou, S.; An, N.; Peng, B.; Soavi, G.; Rao, Y.; Yao, B. Multispecies and Individual Gas Molecule Detection Using Stokes Solitons in a Graphene Over-Modal Microresonator. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Liang, Z.; Ma, Q. The Luminescent Nb2C MXene Nanosheet-Based Whispering Gallery Mode-Enhanced ECL Strategy for miRNA-214 Detection. Talanta 2024, 279, 126627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Yang, L. Multimode Sensing by Optical Whispering-Gallery-Mode Barcodes: A New Route to Expand Dynamic Range for High-Resolution Measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochalov, K.E.; Vaskan, I.S.; Dovzhenko, D.S.; Rakovich, Y.P.; Nabiev, I. A Versatile Tunable Microcavity for Investigation of Light–Matter Interaction. Review of Scientific Instruments 2018, 89, 053105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Saetchnikov, A.; A. Tcherniavskaia, E.; A. Saetchnikov, V.; Ostendorf, A.; 1.Applied Laser Technologies, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum 44801, Germany; 2.Radio Physics Department, Belarusian State University, Minsk 220064, Belarus; 3.Physics Department, Belarusian State University, Minsk 220030, Belarus Deep-Learning Powered Whispering Gallery Mode Sensor Based on Multiplexed Imaging at Fixed Frequency. Opto-Electronic Advances 2020, 3, 200048–200048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suebka, S.; McLeod, E.; Su, J. Ultra-High-Q Free-Space Coupling to Microtoroid Resonators. Light Sci Appl 2024, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, V.R.; Ibrar Jahan, M.A.; Sridarshini, T.; Geerthana, S.; Thirumurugan, A.; Hegde, G.; Sitharthan, R.; Dhanabalan, S.S. Machine Learning Enabled 2D Photonic Crystal Biosensor for Early Cancer Detection. Measurement 2024, 224, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Surve, J.; Baz, A.; Parmar, Y. Optimization of Novel 2D Material Based SPR Biosensor Using Machine Learning. IEEE Trans.on Nanobioscience 2024, 23, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badloe, T.; Rho, J. Enabling New Frontiers of Nanophotonics with Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals, and Plasmonics. Nanophotonics 2024, 13, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wekalao, J.; Mandela, N.; Apochi, O.; Lefu, C.; Topisia, T. Nanoengineered Graphene Metasurface Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor for Precise Hemoglobin Detection with AI-Assisted Performance Prediction. Plasmonics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.; Kanwal, T.; Ahmad, N.; Fatima, B.; Najam-ul-Haq, M.; Hussain, D. Advances and Challenges in Portable Optical Biosensors for Onsite Detection and Point-of-Care Diagnostics. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 173, 117640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Duan, B.; Li, C.; Yang, D. Multimode Sensing Based on Optical Microcavities. Front. Optoelectron. 2023, 16, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D.; Lan, X.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J. Advances in Miniaturized Computational Spectrometers. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2404448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).