1. Introduction

As a vision challenge task, scene text image super-resolution (STISR) aims to reconstruct high-resolution (HR) textual sequences from low-resolution (LR) text contained images. Due to imaging conditions and other reasons, scene text images often suffer from defects such as low resolution, which greatly affects the accurate acquisition of text details as well as subsequent recognition tasks, such as scene text recognition [

1,

2,

3] and scene text detection [

4,

5]. Existing methods typically utilize text-specific features, such as stroke and character structure, to improve the comprehensibility and discrimination of the resulting super-resolution text images [

6,

7,

8]. In this paper, we focuses on relieving the limitations as the dense distribution of characters and the inefficient representation of foreground sequences from complex background in real scenes.

With the bloom of deep learning, Deep Convolutional Neural Network(DCNN) has become the basic component for STISR due to its powerful nonlinear mapping capability and adaptability. TextSR [

6] uses recognition loss to guide the training of generative adversarial networks. TPGSR [

9] incorporates semantic features extracted by a text recognizer into the generative network. TATT [

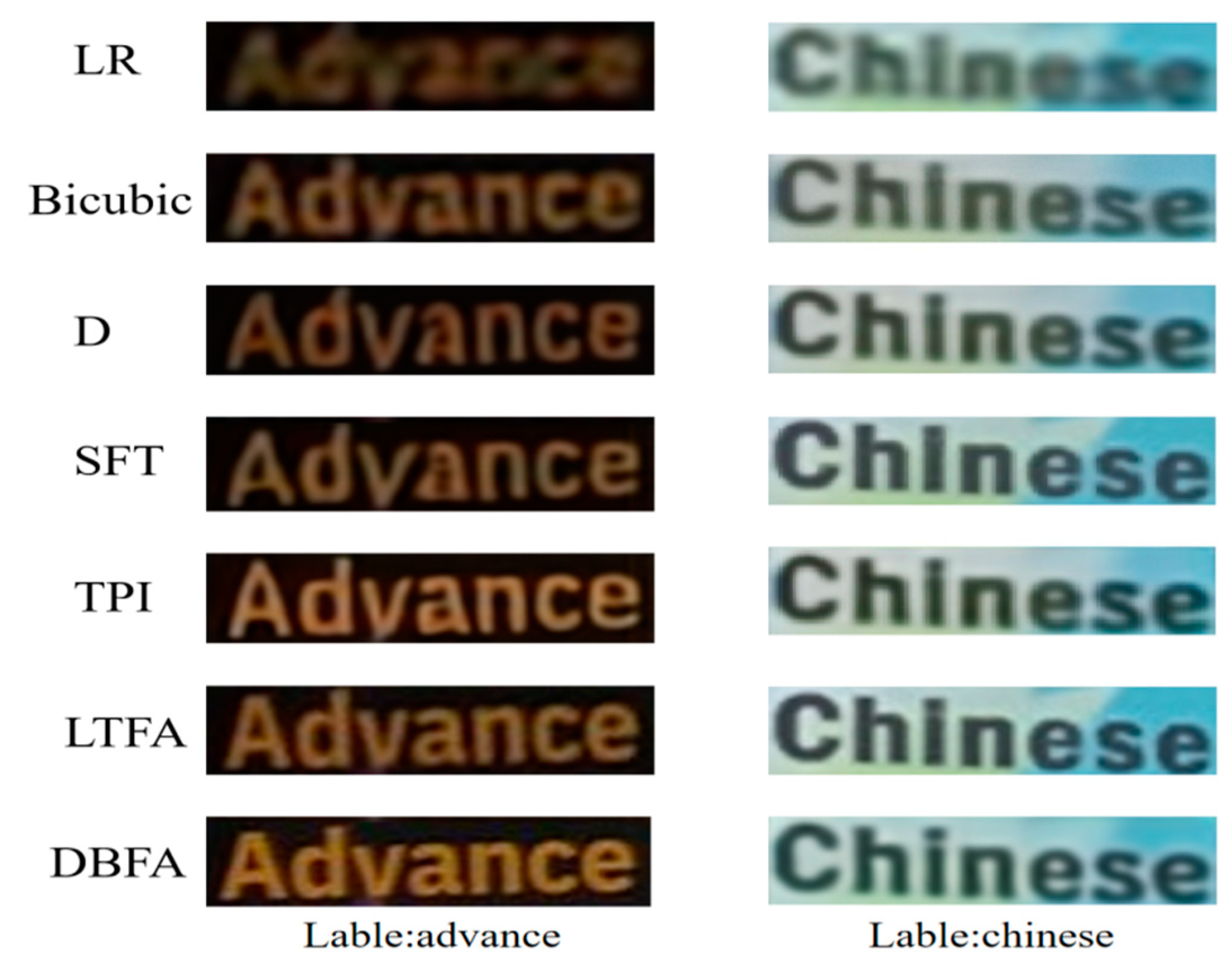

10] devised a TP interpreter and structural consistency loss for processing spatially deformed text. As shown in

Figure 1(a,b), the above baseline does not adequately consider the inherent dense distribution of characters and the detrimental effect of complex backgrounds on the local representation and reconstruction of characters.

Afterwards, TSRN [

7] proposed to capture contextual information in images by combining sequential residual blocks. In addition, TBSRN [

8] exploits the advantage of the attention module in processing sequential information, which makes the model robust to text regions in any orientation. Whereas the design of Gestalt [

11] focuses on modelling the internal structure at the character stroke level in text images. MTSR [

12] makes use of multiple transformers to perform the multi-tasks of image reconstruction and super-resolution. These schemes usually use traditional convolution operations. Due to their limited receptive fields, they focus on capturing local features such as strokes and edges of characters.However, as continuous data, the readability of text also depends on global information such as the relative position and overall arrangement of characters. Therefore, a competent architecture that takes into account both local details and global semantic information needs to be further explored.

In recent years, MNTSR [

13] using self-supervised end-to-end memory networks has been proposed, while PerMR [

14] fuses low-level strokes and high-level semantics extracted from a text recognition network to improve the visual quality, and furthermore, TLWSR [

15] proposes a weakly-supervised framework to implement STISR when only some of the HR labels are available. As shown in

Figure 1(c), these methods use semantic information or only focus on the text structure, while ignoring the color and texture of the original image. Which leads to frequent color drift between the text area and the background area in the generated image.

Aiming at the above bottlenecks, this paper proposes a single character based embedding feature aggregation using cross-attention for scene text super-resolution tasks, with the following main contributions:

This study proposes a two-branch feature aggregation strategy. It aggregates independently clipped single-character image features with corresponding character probability sequences. In this way, the high-level prior of the aggregation focuses on the structural details of the characters themselves, effectively reducing the interference of the complex background. In addition, the influence among neighbouring densely distributed characters is significantly reduced.

Considering the harmonization capability of different sized convolutional kernels due to their specific receptive fields, a improved Inception module is introduced into the shallow layers, in order to apply the dynamic multi-scale feature extraction strategy. By dynamically weighting scaled convolutional kernels, the global overview features and fine-grained features are adaptively adjusted for each input, thus enriching the feature expressions to comprehensively understand the salient vision content.

Using the idea that adaptive normalisation can learn the mapping relationship between different image domains, a colour correction operation is applied to adaptively adjust the mean and standard deviation of the pixels of target images. This improves the quality and effect of super-resolution reconstruction while keeping the content of the original image unchanged. Experiments are performed on the public dataset TextZoom, and the results show the superiority of the proposed model with the existing baselines. The average recognition accuracy on the test sets of CRNN, MORAN, and ASTER is improved by 1%, 1.5%, and 0.9%, respectively.

2. Related Works

2.1. Image Super Resolution

The super-resolution (SR) tasks aim to generate HR images from LR inputs through a priori spatial learning methodology. Traditional SR algorithms can be categorized as interpolation-based [

16,

17,

18], frequency-domain-based [

19,

20] and learning-based [

21] organizing by proposed order. With the rise of deep learning, Dong et al [

22]. firstly suggested using a set of convolution layers to learn prior representations for super-resolution reconstruction. Since then, the scale of SR networks has been expended to be further implemented on STISR tasks. For instance, VDSR [

23] as a SR architecture using 20 convolutional layers, ESPCN [

24] formulated by a sub-pixel convolutional network, recursively structured deep network [

25] and Deep residual network [

26] with jump connections. After that, the SRGAN approach has adopted adversarial learning to the field of SR reconstruction. Recently, diffusion models have been further introduced to different vision tasks including SR after surpassing GANs. For instance, SRDiff [

27] is the first diffusion-based SR model for single image reconstruction, which can effectively relieve the problems of spatial detail confusing and training pattern collapse in order to formulate realistic results.

2.2. Scene Text Recognition for STISR

Scene text recognition (STR) refers to the process of automatically detecting and recognizing text information in natural scene images. With the rise of deep learning, STR has made breakthrough progress. CRNN [

2] transforms a text recognition problem into a sequence learning problem, modeling the position and shape of individual characters. MORAN [

3] enables text detection and recognition through a spatial transformation network and a recognition network. Adaptive correction network and attention sequence recognition model introduced by ASTER [

28]. TextSR [

6], TPGSR [

9], TATT [

10] and other methods all use the above recognizer to extract text a priori to guide SR networks. In this paper, we generally apply the above three recognizers to capture semantic information and then allocate it to corresponding image features to improve reconstruction performance.

2.3. Scene Text Super Resolution

Different from Single Image Super-Resolution (SISR), STISR focuses on upgrading the quality of text images in order to improve the readability of the text and enhance downstream recognition tasks. In spite of the SISR approaches can theoretically be applied to STISR, e.g., Dong et al. perform the STISR task by extending the SRCNN [

29] baseline to text images. Also, PlugNet [

30] employs a lightweight SR module to extract features of LR images. However, STISR generally requires special processing to maintain the character and clarity of text. In recent years, more models specifically designed for STISR have been suggested. These schemes often utilize specific features of the text, such as stroke information and text structure, to improve the super-resolution results.

In addition, TextSR employs text recognition loss and text perception loss to preserve text feature, such as stroke clarity and word spacing, to ensure that super-resolution processed text can be recognized more accurately by optical character recognition (OCR) systems. To improve the effectiveness of STISR on real scenes, Wang et al. built a real scene text image dataset as TextZoom, and proposed TSRN using a centre-alignment module and sequence residual blocks to extract semantic information. Also, PCAN [

31] adopts a parallel contextual attention network with specific mechanisms to effectively fuse multi-scale features and enhance the recovery of textual details. TATT then uses a TP interpreter module based on an attention architecture that aligns textual priori and image features based on a global attention. Moreover, C3-STISR [

32] jointly utilizes recognition feedback, visual and linguistic multiple cues to enhance textual image and design triple cross-modal extraction and aggregation mechanisms for comprehensive guidance. Although the above methods focus on textual and characters reconstruction with prior details, the challenge still comes from the extreme dense text structure as well as the confusion with complex backgrounds.

3. The Proposed Network Architecture

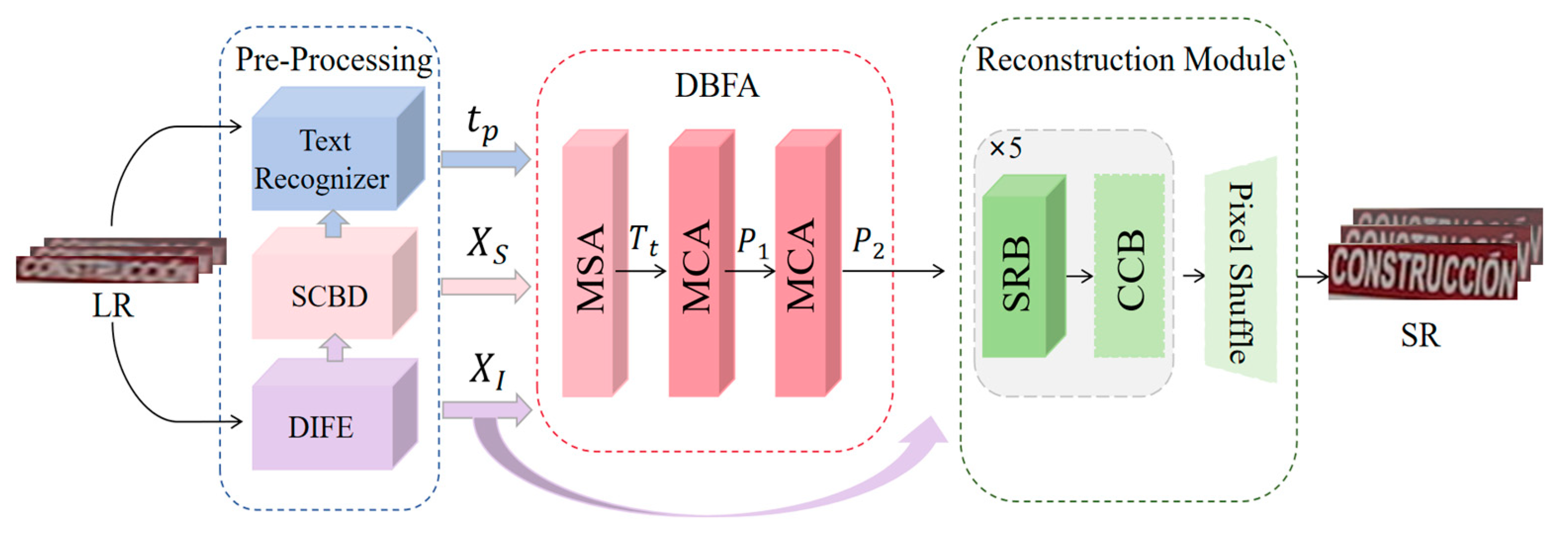

The feedforward network structure for STISR is an important factor that affects the reconstructed processing of textual images. In this paper, the single character embedding feature aggregation for driving the cross-attention based STISR network (SCE-STISR) is shown as

Figure 2. According to it, LR images

are used as inputs to the preprocessing, that employs a dynamic inception feature extraction to extract shallow features

, which also takes into account both global and local representations. Then a pre-trained text recognizer predicts text probability sequences

. Single character boundary detection clip

into character feature

according to character position information.

,

and

parallel input dual branch feature aggregation to guide the aggregation of visual and semantic representations. Ultimately, a high-level prior

= is formulated as input of the reconstruction module, which includes a colour correction layer for improving colour consistency and accuracy, and finally a sequence residual block for performing SR image reconstruction.

3.1. Image Pre-Processing

Image pre-processing procedure consists of three parts. That is dynamic inception feature extraction, single character boundary detection and Text Recognizer. According to them, LR image are fed as inputs, and shallow features , character image features and text priors are estimated as outputs.

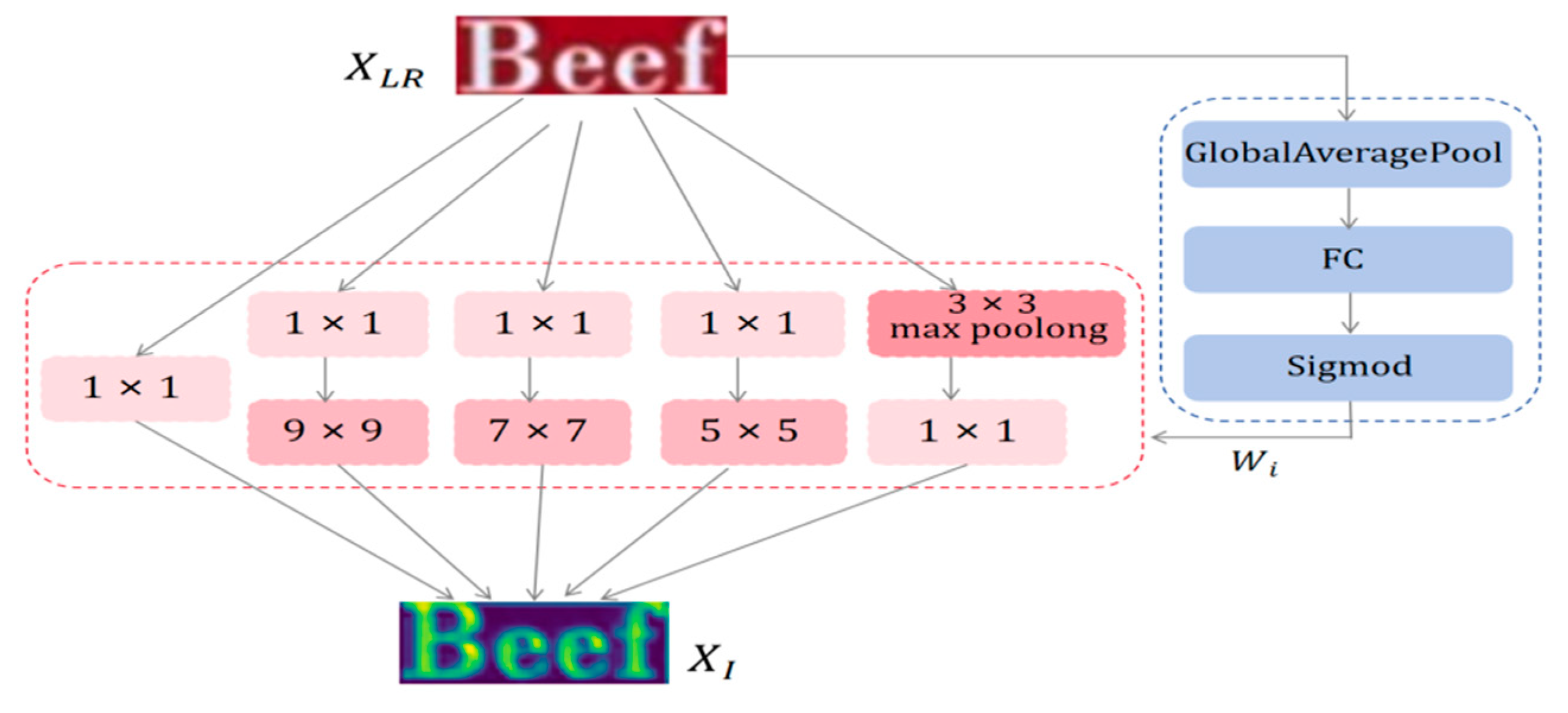

3.1.1. Dynamic Inception Feature Extraction

In general, the receptive fields of a single convolution layer are limited, and only single-scale features can be extracted. However, the characters in text images has multi-scale property involving font, size, style, etc., which results in the inefficient of single convolution layer to adequately extract rich prior representations. The block of dynamic inception feature extraction(DIFE) [

33] applied in this paper is shown as Fig.3. We use multi-scale convolution kernels to flexibly capture structural features at all levels in the text, from letter shape to word layout, to adapt to different datasets and task requirements. Then the 1x1 convolutional kernel is applied for dimensionality reduction or upgrading of feature channels, which adjusts the parameters scale and the network nonlinearity to formulate efficient architecture.

where

is LR text image, where H and W are the height and width, respectively.

denotes the shallow features extracted from the text image at each layer with

, and C denotes the number of feature channels,

as the size of the convolution kernel sized by

, and

denotes the convolution function.

Since different inputs have different priorities in the feature space captured by multi-scale convolution kernels, therefore this paper introduce a dynamic feature weighting mechanism.This mechanism can adaptively assign specific weights to each kernel branch based on the specific feature distribution according to the input data. This strategy not only enhances the network's sensitivity and ability to capture diverse features, but also enables it to more accurately understand and process complex text structures, thereby improving the overall performance and generalization capabilities of the model. The computational process is represented as:

where

represents compound operation,

means global average pooling operation on input

. After that, through the

fully connected layer function, the respective weight coefficients of the five convolutions of different input samples are learned. Finally the weights on each dimension are constrained to [0,1] by sigmoid function

to obtain the normalized dynamic weights

. Also

is the shallow feature output.

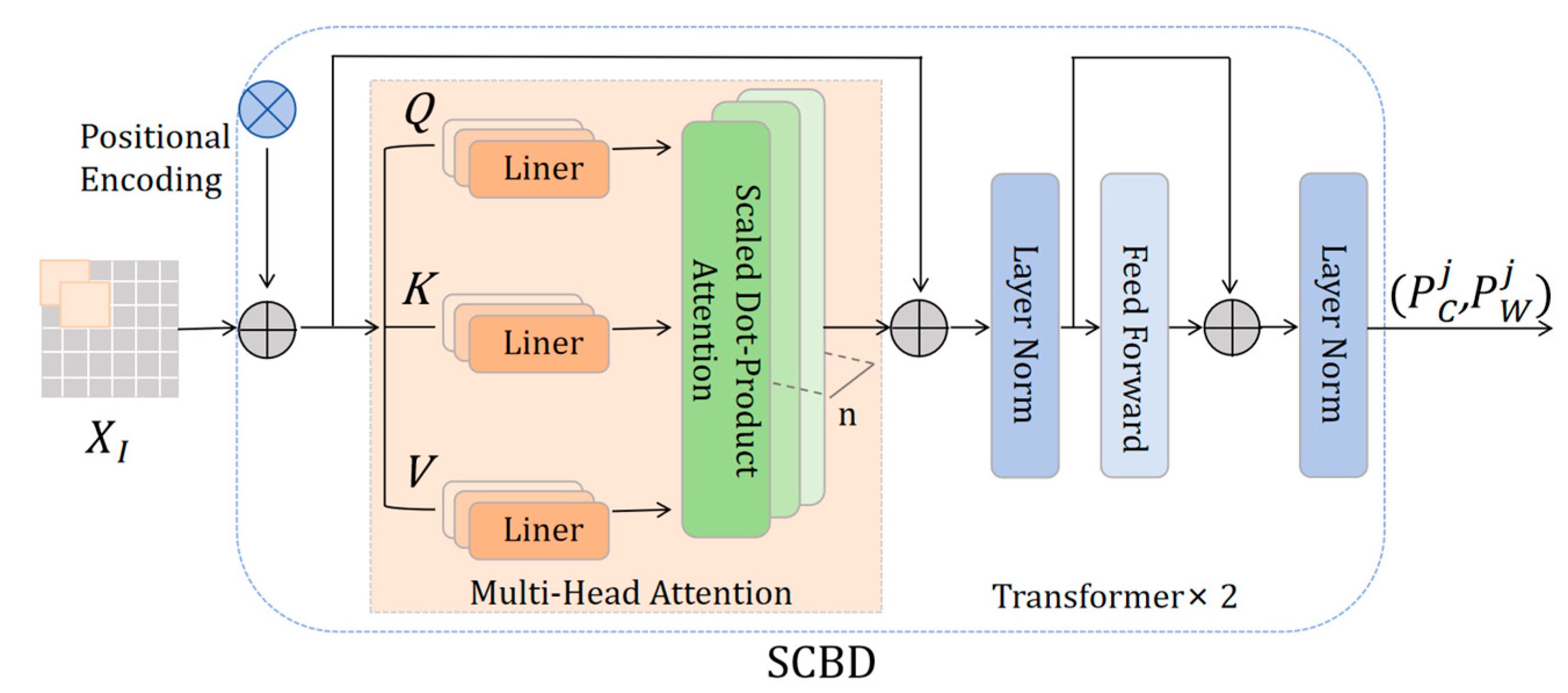

3.1.2. Single Character Boundary Detection

Since LR images usually contain multiple characters, the relative position and order of arrangement between characters is critical. Transformer's self-attention [

34] can directly model the association between any two characters, thereby generating more accurate text position information. In order to effectively separate foregrounds from background and maximize textual priori information to guide semantic and visual reconstruction, this study adopts transformer-based single character of boundary detection (SCBD) [

35] to predict the character positions for clipping individual characters as formulation of a image block sequence.

SCBD as shown in

Figure 4, the input

is flattened as

,

is a sequence of 2

D image blocks, the resolution of each image block is

, and the number of image blocks

. To help the model maintain position sensitivity while processing the sequence data, a further position coding

is fed into the encoder to predict the character position:

In Equation (4), refers to the centre position and width of the each predicted character, j represents the jth character , as well as refers to the cascade transformer encoder.

In order to reduce background interference, focus on the foreground of the text, and weaken the influence between neighbouring characters, we use the predicted positional information

to crop out the corresponding single character features:

where

denotes clipping operation,

indicates a single character feature,

is flattened as

and

represents the output of concatenation of

.

3.1.3. Text Recognizer

The aim of text recognizer (TR) is to capture text probability sequences in LR images as a priori information, thus guiding the model to reconstruct SR images with precise text semantics. In the related works, the methods such as CRNN, Moran and Aster show excellent performance in the field of text recognition. Therefore, this paper selects these pre-trained recognition models to obtain the coding vector of the text category

:

In this equation, is the TR function and is the probability sequence of the text prior, where M denotes the length of the sequence, and S as the number of categories in the reference text label set. In general, this set consists of the Arabic numerals 0-9, 26 letters of the alphabet, and a blank character.

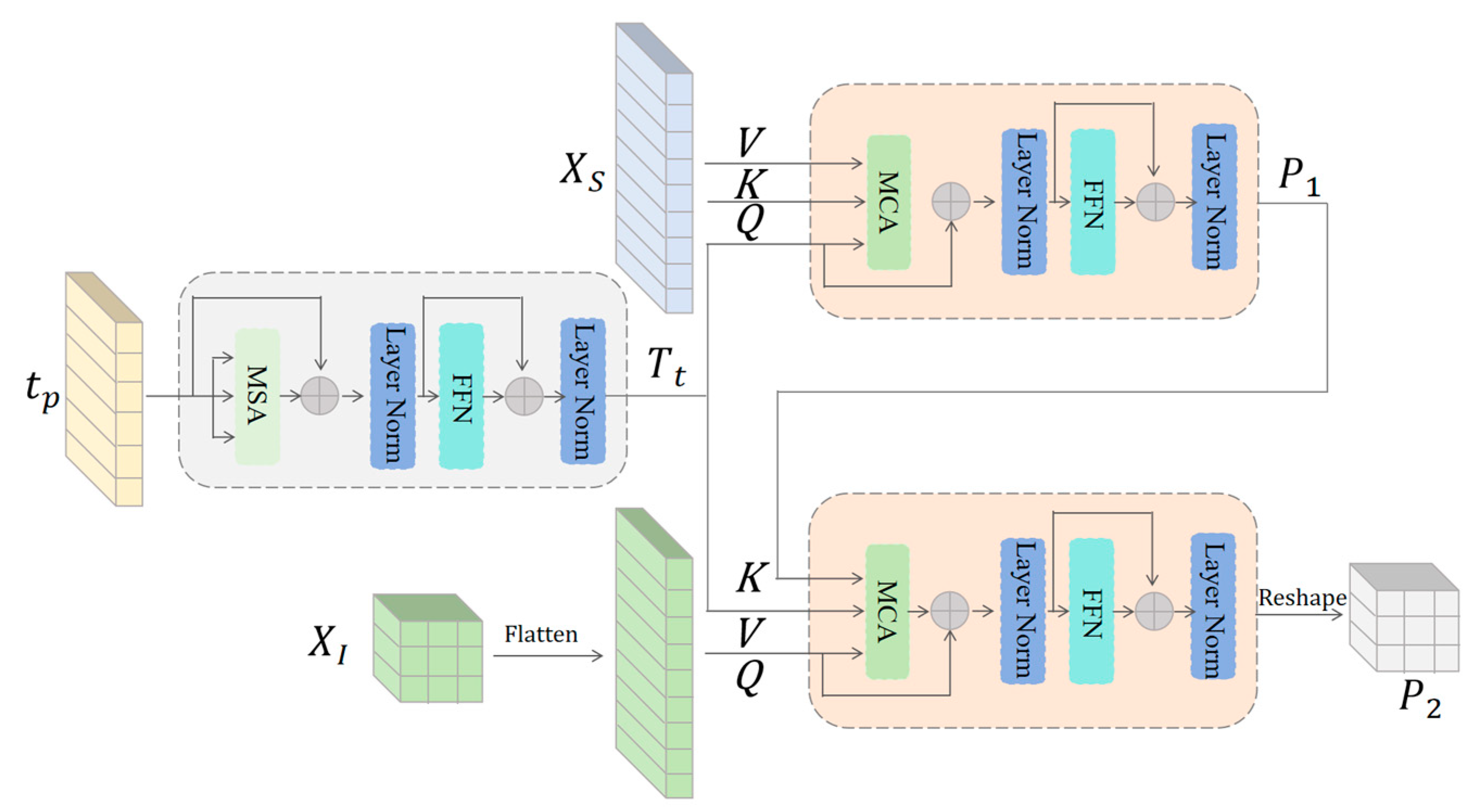

3.2. Dual Branch Feature Aggregation

In the proposed architecture, dual branch feature aggregation (DBFA) is the key part.The purpose of DBFA is to interpret text priori before image features, thereby exerting precise semantic guidance on relevant spatial locations in the image feature domain. With the deep interaction between prior knowledge of the text and image features, character adhesion and background interference gradually intensify, leading to wrong semantic guidance. In order to address the above challenges, this study focuses on the aggregation of individual character features, while aggregating global features to supplement missing background information.

As shown in

Figure 5, self-attention by capturing the semantic connections of characters and enhancing relevance, it helps understand the structure and meaning of the text. In this study, text priori

is projected to C-channel using linear projection to match the number of channels of the feature map.

where

,

and

refer to functions of layer norm, multi-head self-attention (MSA) and feedforward network (FFN) respectively. MSA performs global correlation between textual semantic elements and outputs contextually enhanced textual features

.

To achieve depth alignment between text features

and image features, a two-level multi-head cross-attention(MCA) is used. Where text feature

and single character feature

are used as first-level MCA inputs, with

as the query,

as the key and value, and let each character find the image feature that corresponds to it. The input tensors

and

are first split into n sub-tensors in the channel dimension.

where

, , are the linear mapping matrices corresponding to the

ith attention head respectively.

In this equation,

is the calculated attention per head and

is the length of

for scaling the attention. We process the results

with a channel-wise concatenation operation

(·) and a linear projection function

, described as:

The output is passed to a FFN for feature refinement, obtaining a high-level prior without background interference.

In addition, the prior

contains character image block

as a key, text features

as a value, and the size is consistent. It can be directly input into the secondary MCA to avoid dimensional inconsistencies. We use

to connect semantic information and global visual features. We Flatten the shallow features

as query. Unlike the

in first-level MCA the

are not flattened according to single characters, and the background and foreground information is not clear in terms of primary and secondary. However,

contains global features, which effectively improves the visual quality problem caused by missing background. The

as a key and

as a value.

Also each pixel point in can be queried by to the text feature corresponding to it. Obtaining a high-level prior for valid semantic mappings.

Since the cropped image is a sequence of image block features arranged by character, cluttered background interference is avoided when using transformer aggregation. And when calculating the correlation it reduces the interference of the neighbouring characters on the recovery of the current character. Global features can more accurately assign semantic information to the spatial domain via .

3.3. Reconstructed Module

The reconstruction module in this study consists of a Sequential Residual Block (SRB), a Colour Correction Block (CCB), and an upsampling layer. sent to the SRB for SR reconstruction. And each time the resulting features are again sent to the SRB for element-by-element summation with to ultimately obtain the SR reconstruction features . However, the SR image restored through upsampling the reconstructed features using the Pixel-Shuffle layer may suffer from color drifting in either the text part or the background part. In view of this, this study considers adaptive normalization to adjust the feature representation of the image to match the statistical properties of the target domain. So that the model can generate images that are consistent with the target style.

In detail, the mean and variance of the colour values of the SR image and LR image were first calculated using the

function as the target criterion:

where c denotes the RGB channel,

, and

, denote the mean and variance for

and

. Secondly the

are normalized to improve the model accuracy:

Subsequently applying

and

to the normalized feature

, the SR image is adjusted so that its colour value mean and variance are consistent with that of the LR image to obtain the colour corrected reconstructed feature

.

The reconstruction process in this study consists of five SRB and CCB modules connected in series, and finally an upsampling layer to obtain the reconstructed high-resolution image features .

3.4. Loss Function

In this study the total loss function consists of pixel loss

and text recognition prior loss

.

The

loss generates high quality images from LR images by constraining the

paradigm of super-resolution images and high-resolution images.

In Equation (18)

and

denote hyperparameters, A denotes the attention map obtained using the text recognizer, and

and

denote the text probability sequences of SR and HR images obtained by the text recognizer.

denote the text recognition branch is fine-tuned by constraining the

paradigm and the KL scatter of the text prior recognized from the low-resolution image and the real image. The total loss function

is expressed as follows.

In Equation (19), is the equilibrium parameter. During the training process, the loss function is used as the optimization objective, and the error signal is then passed to the proposed network through the back-propagation iterations to guide the updating of all the modules parameters.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

In this paper, the DIFE is designed to dynamically adjust the multi-scale feature weights according to the different structures, shapes, and distributions of the input images in order to improve the information loss caused by single convolution. The DBFA as the main architecture of the model achieves deep interaction between global and local feature semantics to vision based on cross-attention. In addition the CCB adaptively adjusts the colour error caused by background interference using the input colour channel as a target criterion. The effectiveness of the components proposed in this study verified by ablation experiments in

Section 4.2.

Section 4.3 verifies the excellent performance of the model by performing comparative experiments on the TextZoom and the generalisation and robustness of this study is demonstrated by performing comparative experiments on the STR dataset.

4.1. Dataset and Experimental Details

TextZoom: The STISR dataset is derived from two state-of-the-art SISR datasets, RealSR and SRRAW, which are captured by a multifocal camera in the field, and are more realistic and challenging than the synthetic data. 17,367 pairs of LR-HR training sets and 4,373 pairs of test sets are included in TextZoom, with text annotations, border types, and raw focal lengths information. The smaller the focal length the blurrier the image is at the same height. The test set is divided into three subsets: 1619 samples for the easy subset, 1411 samples for the medium subset, and 1343 samples for the hard subset.

STR dataset: in order to verify the effectiveness of the method on different distribution datasets, we use five English STR datasets, namely, ICDAR2013 [

36], ICDAT2015 [

37], SVT [

38], SVTP [

39], and CUTE80 [

40]. ICDAR2013 contains 1015 test samples, and ICDAR2015 contains 2,077 samples, and the text in the images may appear in a variety of scenes, with problems of distortion, occlusion, and uniform illumination. SVT contains 350 test samples, with large scale changes and complex backgrounds, the text may be bent and distorted, and the lighting conditions are varied, which makes the recognition more difficult. SVTP contains 645 test samples, although it is a synthetic data, the text image is of high quality, it lacks the complexity of the real scene. CUTE80 contains 288 text images with characters arranged along curved paths, forming curved text lines, with large image resolution, high quality and no LR images. In pre-processing, the images with resolution smaller than

are selected and degraded with Real-ESRGAN [

41] to test the robustness of the model.

The model is implemented using PyTorch framework and all the experiments are performed on a single RTX4090 GPU. The number of MSA in the SCBD is set to 4 and SRB is set to 5. The model with input batch size of 64, image width of 64 and height of 16 is optimized using Adam [

42] and the number of training rounds is set to 500 and the learning rate is set to 0.001, which yields an output with a width of 128 and a height of 32. In this study, three text recognizer, ASTER, CRNN and MORAN, are used to assess the recognition accuracy. In order to assess the quality of image reconstruction, we use Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) [

43] as reference metrics.

4.2. Ablation Experiment

In this study, the effectiveness of the DIFE, DBFA, and CCB is validated on the TextZoom using CRNN as a text recognizer.

4.2.1. The Role of Dual Branch Feature Aggregation

The DBFA is designed to accurately interpret the semantic information

the corresponding positions in the image features

and align between the textual a priori and the image features. Which is compared with other textual a priori interpreters in this study: firstly, the

is fused with the

using the inverse convolution block [

9], secondly, the

and

are aligned using the SFT layer, and the SFT layer [

44] outputs parameter pairs based on some textual a priori conditions, which affect the outputs by applying an affine transformation spatially to each intermediate feature map in the SR network to adaptively fuse the textual features. Finally, TPI is used to compute the correlation between textual prior and image features to guide the final SR text recovery. In order to verify the effectiveness of the DBFA, the local text feature aggregation LTFA is separately experimented as the text a priori interpreter.

Table 1 shows that the DBFA module proposed in this paper obtains the highest recognition accuracy and average accuracy in Easy, Medium, and Hard subsets, and the PSNR and SSIM indicators are also optimal, showing excellent SR performance.

(50.6%) and

(49.2%), although using text a priori to guide the reconstruction, they are not accurately assigned to the corresponding positions in the image feature space, resulting in the underutilisation of the a priori information, and TPI (52.8%), although aligning the image features with the text region well, the background foreground and foreground are not clear in terms of the primary and secondary, and the attention mechanism is not sufficiently allocated to the text part of the weights. Using only local textual feature integration (53.1%) ignores the background influence and reduces the visual quality. In contrast, DBFA focuses on both the foreground, accurately aligns the text prior and image features, and takes into account the background, improving the recognition accuracy to 53.6%, PSNR to 21.84, and SSIM to 0.7997, validating it as an effective super-resolution reconstruction method. The visual comparison in

Figure 6 shows that the text image obtained by this paper's method has the best visual quality.

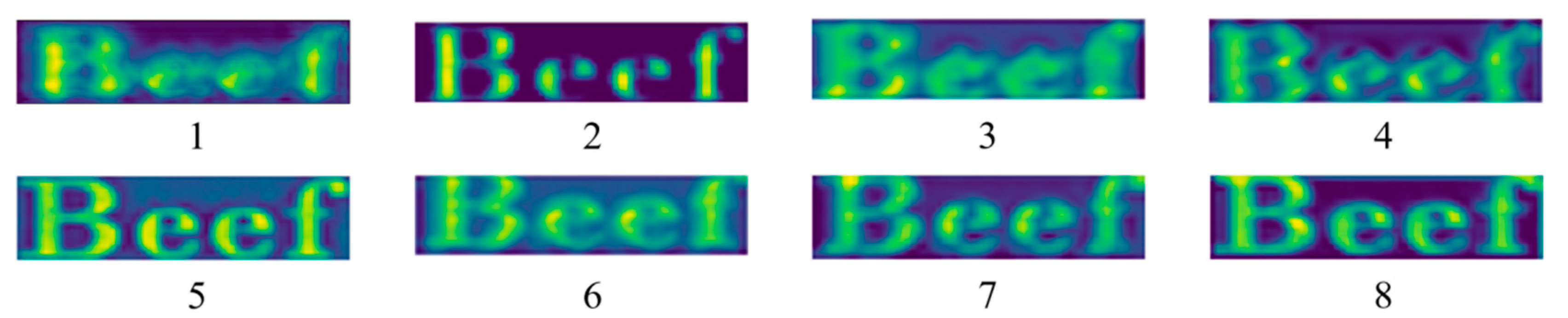

4.2.2. Dynamic Inception Feature Extraction

In this study, the DIFE is mainly used for multi-scale feature extraction[47]. Small convolutional kernels (e.g., 1x1, 3x3) focus on the local area, capture fine details such as edges and textures, and are suitable for extracting low-level features. Medium convolutional kernel (e.g. 5x5, 7x7) has a moderate sense field, captures both local and partial global information, and is suitable for extracting medium-level features such as part of an object's shape or silhouette. Large convolutional kernels (e.g., 9x9) have a large receptive field, cover a larger image area, and are suitable for extracting high-level features such as the overall shape of an object or the context of a scene. The dynamic weighting strategy adaptively adjusts the proportion of multi-scale feature information extracted from different convolutional kernels according to different input distributions. This experiment analyses the relationship between different sizes of convolutional kernels and whether or not to add the dynamic weighting strategy in feature extraction and recognition accuracy, and the results are shown in

Table 2.

The combination of multi-scale convolution kernels proves to be advantageous by significantly improving the results compared to single convolution layer feature extraction. Small convolution kernels ignore contextual information to reduce accuracy, while large convolution kernels do not capture enough details. Experiments show that DIFE achieves the best recognition accuracy (53.6%) at the eighth set of convolution kernel sizes. The visualization in

Figure 7 shows that the module is highlighted in the character region with the best retention of global and detailed features.

4.2.3. Validity of the CCB Module

To verify the effectiveness of the CCB module in colour correction, five models, TPGSR, TATT, C3-STISR, MNTSR, and SCE-STISR, are selected to compare the results with and without the CCB module.

Table 3 shows that all models improve in text recognition accuracy or SR quality, proving that the colour correction module improves image reconstruction quality.

4.2.4. Effectiveness of Different Components

As shown in

Table 4, this experiment investigated the effectiveness of introducing different modules, from which it can be seen that the results are optimal when all three modules are added at the same time.

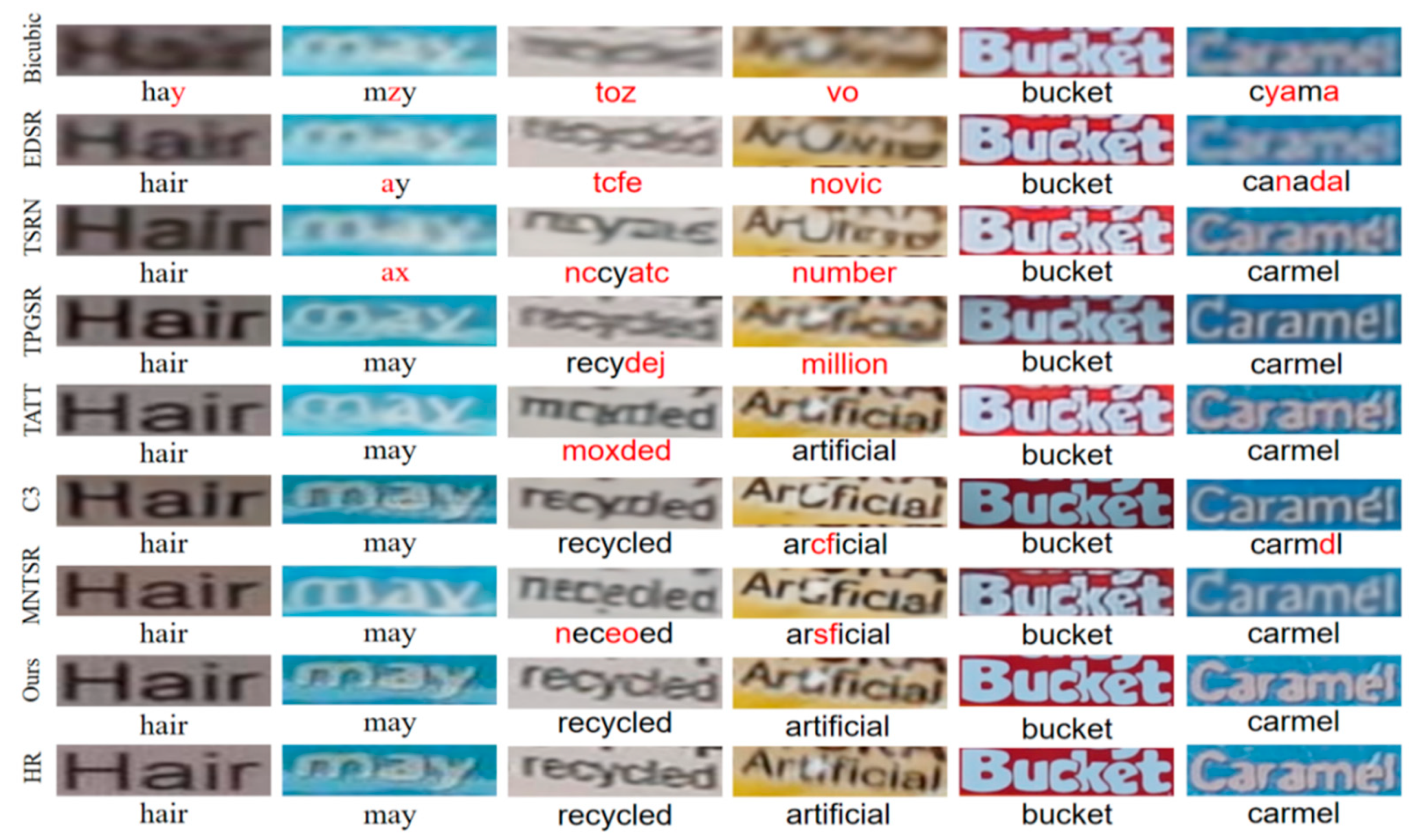

4.3. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Results

4.3.1. TextZoom Quantitative Research

To verify the model validity, SCE-STISR was compared with SISR methods (SRCNN, SRResNet, EDSR, RCAN, CARN, HAN) and STISR models (TSRN, TBSRN, PCAN, TPGSR, Text Gestalt, TATT, C3-STISR, MNTSR, PerMR) were compared.

The recognition accuracies of the experiments based on CRNN, MORAN, and ASTER recognizer on the TextZoom test set are shown in

Table 5. Since the SISR method is a generalised SR, it does not take into account the unique character structure of text images, and the textual information contained in the images. The results show that the recognition accuracy of SISR methods is generally low. Most of the other STISR methods use a single convolution layer, which is unable to take into account both character details and textual context, and treats foreground and background equally. with our method achieving the highest accuracy and sub-optimal average accuracy on the medium and difficult subsets; sub-optimal average accuracy on MORAN; and optimal simple subset and optimal average accuracy on ASTER. Compared with the STISR baseline TATT, we improve the average recognition accuracy on CRNN, MORAN, and ASTER by 1%, 1.4%, and 0.9%, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the method.

The results of SSIM and SPNR, which are common evaluation metrics for super-resolution, are shown in

Table 6. Our method employs a CCB to constrain the super-resolution reconstructed image to be infinitely close to the low-resolution image in the colour channel. So that the output image maintains the same statistical characteristics as the input, ensuring consistency with input perception, to improve the image visual quality, and structural similarity. While previous methods only consider the readability of the text part of the image, ignoring the effect of the image as a whole. Foreground and background interactions can also lead to colour drift, low reconstructed visual quality and weak structural similarity. The accuracy of the downstream text image recognition task depends on the image quality, and the PSNR of the model achieves the optimal results in the simple subset (24.99) and difficult subset (20.78) as well as the average PSNR (21.84), and performs the best in the medium subset (0.6955) and the difficult subset (0.7859) and the average (0.7951) SSIM metrics, which confirms its Validity.

4.3.2. TextZoom Qualitative Research

As shown in

Figure 8, in order to further validate the effectiveness of the model, the visualization results after image reconstruction with different text lengths, backgrounds and colors and the text recognition results are shown.

Observations show that all methods outperform the bicubic interpolation method, but there is a significant difference in visual quality between the SISR and STISR. In this paper, the text-specific model SCE-STISR has the best visualisation results closest to HR images. As shown in the first and second columns of the figure, although most methods can accurately recognise characters, problems such as blurring of character structure and bending of strokes may occur when using text for super-resolution reconstruction. On the other hand, SCE-STISR can accurately assign semantic information to the corresponding image features, reconstruct the image correctly, and obtain satisfactory visual effects. In addition, the model performs well in dealing with the dense connection of characters and the background influence on foreground restoration, such as ‘recycled’ and ‘artificial’, the reconstruction results are clear and closest to the high-resolution image, while the other methods show the phenomenon of character mis-construction. In previous methods, the colour of characters or background is easily inconsistent with the colour of LR and HR images, resulting in large errors, such as ‘bucket’ and ‘caramel’, while this method effectively corrects the colour drift and significantly improves the fidelity of images.

4.3.3. Generalisation Capabilities on Text Recognition Datasets

In order to verify the generalisation ability of the model on other datasets, it is tested on five STR datasets, ICDAR2013, ICDAR2015, SVT, SVTP, and CUTE80, using the parameters trained on the TextZoom. These datasets are mostly derived from the real world and contain text of different lengths and complex background images. LR images are selected to form the test set, and due to the high quality of most of the images, Real-ESRGAN second-order degradation method is used to degrade the quality. As shown in

Table 7, SCE-STISR can align the text prior and images more accurately, provide precise guidance, achieve better results, and prove the robustness of the model.

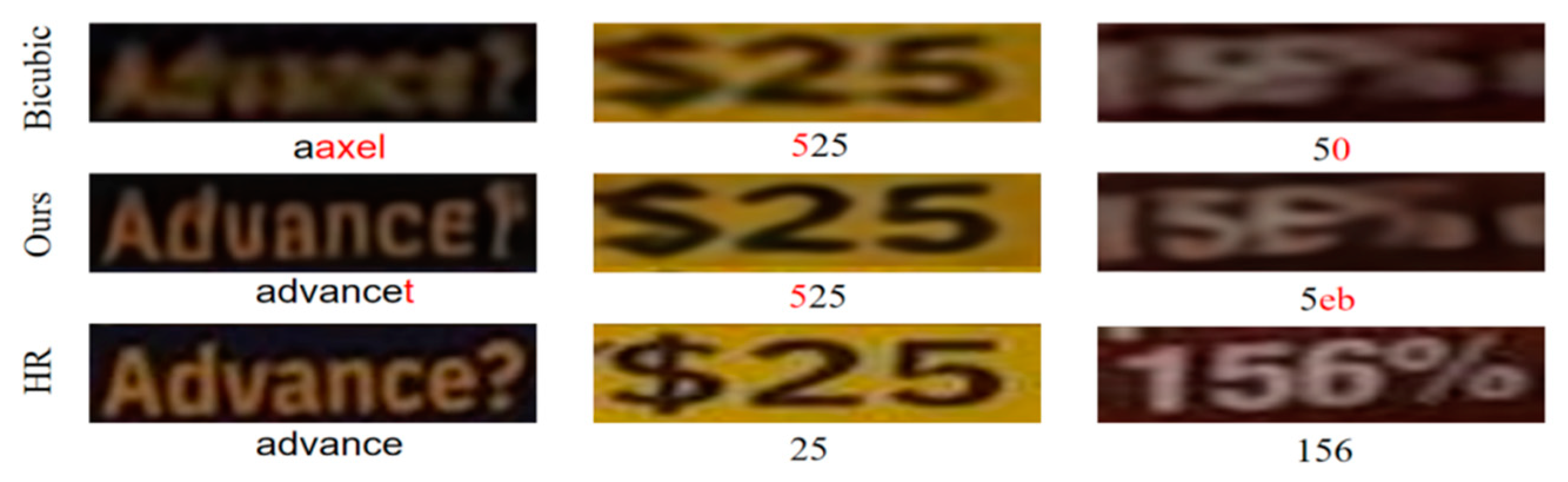

4.3.4. Discussions

Although the SCE-STISR network proposed in this paper can accurately reconstruct English characters and numbers, However, as shown in

Figure 9, when the image does not contain characters in the text label reference character set, the recognizer may misrecognize it and cause reconstruction chaos. Second, the introduction of DBFA increases computational complexity and reduces inference speed. Future work will focus on designing networks that do not require textual prior guidance and exploring how to balance reconstruction quality and inference speed.

Conclusions

In this study, we proposed a single character embedding feature aggregation based on cross-attention for scene text super-resolution. To solve the single convolution to obtain single feature information, we applied the DIFE for multi-scale feature extraction, and dynamically adjust the feature maps under different sensory fields according to different inputs. In addition, we used DBFA, which distinguishes the textual part from the background part by a single character and then uses a semantic prior to guide the image. Finally, a CCB is performed to improve the colour drift problem in the reconstruction process by normalising on the colour channel. In this study, ablation experiments were conducted for DIFE, DBFA and CCB to verify the effectiveness of the model components. To further demonstrate the superiority of this study, we conducted qualitative and quantitative comparison experiments on TextZoom for 16 models, and quantitative comparison experiments on 5 STR datasets for 7 models. The best or second best results were achieved in text recognition accuracy and image quality assessment metrics, respectively.

Author Contributions

Meng Wang, Haipeng Liu, and Qianqian Li conceived and designed the experiments; Qianqian Li performed the experiments and analysed the data, Meng Wang provided materials and analysis tools; Meng Wang and Qianqian Li wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (62062048) andYunnan Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (202201AT070113). This work is alsosupported by Faculty of Information Engineering and Automation, Kunming University of Science and Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, B.; Chen, K.; Peng, S.-L.; Zhao, M. Adaptive Aggregate Stereo Matching Network with Depth Map Super-Resolution. Sensors 2022, 22, 4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Bai, X.; Yao, C. An end-to-end trainable neural network for image-based sequence recognition and its application to scene text recognition. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2016, 39, 2298–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Jin, L.; Sun, Z. Moran: A multi-object rectified attention network for scene text recognition. Pattern Recognition 2019, 90, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, F.; Chen, Z.; Mei, T.; Xu, B. A single-shot oriented scene text detector with learnable anchors. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME); 2019; pp. 1516–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Shao, W.; Ye, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xue, X. Arbitrary-oriented scene text detection via rotation proposals. IEEE transactions on multimedia 2018, 20, 3111–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Sun, P.; Wang, W.; Tian, L.; Shen, C.; Luo, P. Textsr: Content-aware text super-resolution guided by recognition. arXiv:1909.07113 2019.

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, D.; Shen, C.; Bai, X. Scene text image super-resolution in the wild. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part X 16, 2020; pp. 650-666.

- Chen, J.; Li, B.; Xue, X. Scene text telescope: Text-focused scene image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021; pp. 12026–12035.

- Ma, J.; Guo, S.; Zhang, L. Text prior guided scene text image super-resolution. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2023, 32, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, L. A text attention network for spatial deformation robust scene text image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022; pp. 5911–5920.

- Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, J.; Li, B.; Xue, X. Text gestalt: Stroke-aware scene text image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2022; pp. 285–293.

- Honda, K.; Kurematsu, M.; Fujita, H.; Selamat, A. Multi-task learning for scene text image super-resolution with multiple transformers. Electronics 2022, 11, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Zhu, X.; Schaefer, G.; Ding, R.; Fang, H. Self-supervised memory learning for scene text image super-resolution. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 258, 125247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ye, J.; Yang, D. Perceiving Multiple Representations for scene text image super-resolution guided by text recognizer. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 124, 106551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, C.; Yang, D. TLWSR: Weakly supervised real-world scene text image super-resolution using text label. IET Image Processing 2023, 17, 2780–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-g. A new kind of super-resolution reconstruction algorithm based on the ICM and the bilinear interpolation. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Seminar on Future BioMedical Information Engineering; 2008; pp. 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, P.; Azhar, F. A single image interpolation scheme for enhanced super resolution in bio-medical imaging. In Proceedings of the 2010 4th international conference on bioinformatics and biomedical engineering; 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Badran, Y.K.; Salama, G.I.; Mahmoud, T.A.; Mousa, A.; Moussa, A. Single Image Super Resolution Using Discrete Cosine Transform Driven Regression Tree. In Proceedings of the 2020 37th National Radio Science Conference (NRSC); 2020; pp. 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.C.; Park, M.K.; Kang, M.G. Super-resolution image reconstruction: a technical overview. IEEE signal processing magazine 2003, 20, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, A.; Ahmadyfard, A.; Khosravi, H. Adaptive image super-resolution algorithm based on fractional Fourier transform. Image Analysis and Stereology 2022, 41, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wright, J.; Huang, T.S.; Ma, Y. Image super-resolution via sparse representation. IEEE transactions on image processing 2010, 19, 2861–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Image super-resolution using deep convolutional networks. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2015, 38, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Accurate image super-resolution using very deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 1646–1654.

- Shi, W.; Caballero, J.; Huszár, F.; Totz, J.; Aitken, A.P.; Bishop, R.; Rueckert, D.; Wang, Z. Real-time single image and video super-resolution using an efficient sub-pixel convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 1874–1883.

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, K.M. Deeply-recursive convolutional network for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016; pp. 1637–1645.

- Lim, B.; Son, S.; Kim, H.; Nah, S.; Mu Lee, K. Enhanced deep residual networks for single image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2017; pp. 136–144.

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Chang, M.; Chen, S.; Feng, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. Srdiff: Single image super-resolution with diffusion probabilistic models. Neurocomputing 2022, 479, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Lyu, P.; Yao, C.; Bai, X. Aster: An attentional scene text recognizer with flexible rectification. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2018, 41, 2035–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Loy, C.C.; He, K.; Tang, X. Learning a deep convolutional network for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6-12, 2014, Proceedings, Part IV 13, 2014; pp. 184-199.

- Mou, Y.; Tan, L.; Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Yan, R.; Huang, Y. Plugnet: Degradation aware scene text recognition supervised by a pluggable super-resolution unit. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XV 16, 2020; pp. 158-174.

- Zhao, C.; Feng, S.; Zhao, B.N.; Ding, Z.; Wu, J.; Shen, F.; Shen, H.T. Scene text image super-resolution via parallelly contextual attention network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, 2021; pp. 2908–2917.

- Zhao, M.; Wang, M.; Bai, F.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Zhou, S. C3-stisr: Scene text image super-resolution with triple clues. arXiv:2204.14044 2022.

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2015; pp. 1–9.

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zuo, W.; Loy, C.C. Learning generative structure prior for blind text image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023; pp. 10103–10113.

- Stamatopoulos, N.; Gatos, B.; Louloudis, G.; Pal, U.; Alaei, A. ICDAR 2013 handwriting segmentation contest. In Proceedings of the 2013 12th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition; 2013; pp. 1402–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas, D.; Gomez-Bigorda, L.; Nicolaou, A.; Ghosh, S.; Bagdanov, A.; Iwamura, M.; Matas, J.; Neumann, L.; Chandrasekhar, V.R.; Lu, S. ICDAR 2015 competition on robust reading. In Proceedings of the 2015 13th international conference on document analysis and recognition (ICDAR); 2015; pp. 1156–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Babenko, B.; Belongie, S. End-to-end scene text recognition. In Proceedings of the 2011 International conference on computer vision; 2011; pp. 1457–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T.Q.; Shivakumara, P.; Tian, S.; Tan, C.L. Recognizing text with perspective distortion in natural scenes. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2013; pp. 569–576.

- Risnumawan, A.; Shivakumara, P.; Chan, C.S.; Tan, C.L. A robust arbitrary text detection system for natural scene images. Expert Systems with Applications 2014, 41, 8027–8048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-esrgan: Training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021; pp. 1905–1914.

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Dong, C.; Loy, C.C. Recovering realistic texture in image super-resolution by deep spatial feature transform. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018; pp. 606–615.

Figure 1.

(a) Text-intensive concatenation leading to semantic errors in reconstructed characters. (b) Cluttered background interferes with recognition and poses a challenge to super-resolution reconstruction. (c) Colour drift may occur during image reconstruction, affecting the visual effect.

Figure 1.

(a) Text-intensive concatenation leading to semantic errors in reconstructed characters. (b) Cluttered background interferes with recognition and poses a challenge to super-resolution reconstruction. (c) Colour drift may occur during image reconstruction, affecting the visual effect.

Figure 2.

SCE-STISR model structure diagram. It consists of pre-processing module, DBFA and reconstruction module. The low resolution image is the input and the super resolution image is the output.

Figure 2.

SCE-STISR model structure diagram. It consists of pre-processing module, DBFA and reconstruction module. The low resolution image is the input and the super resolution image is the output.

Figure 3.

Dynamic inception feature extraction procedure.The left half represents multi-scale convolution kernel extraction of shallow features. The right panel represents computing the weights of the respective convolution kernels corresponding to the input samples.

Figure 3.

Dynamic inception feature extraction procedure.The left half represents multi-scale convolution kernel extraction of shallow features. The right panel represents computing the weights of the respective convolution kernels corresponding to the input samples.

Figure 4.

Single Character Boundary Detection.Consists of two transformer encoders with shallow features as input and position coordinates as output.

Figure 4.

Single Character Boundary Detection.Consists of two transformer encoders with shallow features as input and position coordinates as output.

Figure 5.

Dual Branch Feature Aggregation. The input to the left half is a textual prior, and the output is used as input to the right cross-attention to guide global and local textual image feature aggregation.

Figure 5.

Dual Branch Feature Aggregation. The input to the left half is a textual prior, and the output is used as input to the right cross-attention to guide global and local textual image feature aggregation.

Figure 6.

Visualisation of super-resolution reconstructed images using different decoders.

Figure 6.

Visualisation of super-resolution reconstructed images using different decoders.

Figure 7.

Text image shallow feature extraction map.1-8 correspond to the eight sets of comparative experimental feature visualization results in

Table 2 respectively.

Figure 7.

Text image shallow feature extraction map.1-8 correspond to the eight sets of comparative experimental feature visualization results in

Table 2 respectively.

Figure 8.

Visualisation of reconstruction results on the TextZoom dataset.

Figure 8.

Visualisation of reconstruction results on the TextZoom dataset.

Figure 9.

STISR Visualisation Results and Text Recognition Results for Unknown Characters in Text Label Character Sets.

Figure 9.

STISR Visualisation Results and Text Recognition Results for Unknown Characters in Text Label Character Sets.

Table 1.

Comparing several text image feature aggregation modules, denotes the deconvolution operation, is the SFT layer fusion operation, TPI is the TP interpreter, LTFA is the local textual feature aggregation, and DBFA is the dual branch feature aggregation.

Table 1.

Comparing several text image feature aggregation modules, denotes the deconvolution operation, is the SFT layer fusion operation, TPI is the TP interpreter, LTFA is the local textual feature aggregation, and DBFA is the dual branch feature aggregation.

| Fusion Strategy |

Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avgAcc↑ |

PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

| w/o DBFA |

51.2% |

41.9% |

31.7% |

41.6% |

21.02 |

0.7690 |

|

61.8% |

52.1% |

37.9% |

50.6% |

21.10 |

0.7819 |

|

60.3% |

50.4% |

36.9% |

49.2% |

20.87 |

0.7783 |

| TPI |

62.9% |

53.5% |

39.8% |

52.8% |

21.52 |

0.7930 |

| LTFA |

63.1% |

53.8% |

39.8% |

53.1% |

21.43 |

0.7954 |

| DBFA |

63.5% |

55.3% |

39.9% |

53.6% |

21.84 |

0.7997 |

Table 2.

Effect of different convolutional kernel sizes on recognition accuracy on the TextZoom dataset.

Table 2.

Effect of different convolutional kernel sizes on recognition accuracy on the TextZoom dataset.

| |

DIFE Parameter |

Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avgAcc↑ |

| 1 |

9*9 |

62.8% |

53.6% |

38.7% |

52.6% |

| 2 |

1*1、1*1+5*5 |

62.4% |

52.1% |

38.6% |

52.5% |

| 3 |

1*1、1*1+7*7 |

63.2% |

53.7% |

38.9% |

52.7% |

| 4 |

1*1、1*1+9*9 |

63.4% |

53.9% |

39.1% |

52.9% |

| 5 |

1*1、1*1+3*3、7*7+1*1 |

62.9% |

53.5% |

39.5% |

53.4% |

| 6 |

1*1、1*1+9*9、5*5+1*1 |

63.6% |

54.6% |

39.7% |

53.2% |

| 7 |

1*1、1*1+5*5、1*1+7*7、1*1+9*9、3*3+1*1 |

63.8% |

54.8% |

39.8% |

53.4% |

| 8 |

1*1、1*1+5*5、1*1+7*7、1*1+9*9、3*3+1*1(dynamic) |

63.5% |

55.3% |

39.9% |

53.6% |

Table 3.

Effect of different convolutional kernel sizes on recognition accuracy on the TextZoom dataset.√ indicates adding CCB, and × indicates not adding CCB.

Table 3.

Effect of different convolutional kernel sizes on recognition accuracy on the TextZoom dataset.√ indicates adding CCB, and × indicates not adding CCB.

| Approach |

CCB |

Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avgAcc↑ |

PSNR↑ |

SSIM↑ |

| TPGSR |

× |

61.0% |

49.9% |

36.7% |

49.8% |

21.02 |

0.7690 |

| √ |

62.1% |

51.6% |

36.7% |

50.4% |

21.32 |

0.7705 |

| TATT |

× |

62.6% |

53.4% |

39.8% |

52.6% |

21.52 |

0.7930 |

| √ |

62.4% |

54.4% |

39.6% |

52.7% |

20.95 |

0.7951 |

| C3-STISR |

× |

65.2% |

53.6% |

39.8% |

53.7% |

21.51 |

0.7721 |

| √ |

65.1% |

54.0% |

39.6% |

53.8% |

21.37 |

0.7853 |

| MNTSR |

× |

64.3% |

54.5% |

38.7% |

53.3% |

21.53 |

0.7946 |

| √ |

64.0% |

54.8% |

38.9% |

53.2% |

21.67 |

0.7964 |

| SCE-STISR |

× |

63.3% |

53.93% |

39.8% |

53.0% |

21.43 |

0.7982 |

| √ |

63.5% |

55.3% |

39.9% |

53.6% |

21.84 |

0.7997 |

Table 4.

Effect of combining different modules, TPI is used instead when DBFA module is not included.

Table 4.

Effect of combining different modules, TPI is used instead when DBFA module is not included.

| DBFA |

DIFA |

CCB |

Recognition Accuracy |

| Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avgAcc↑ |

| - |

- |

- |

62.26% |

52.73% |

39.09% |

52.1% |

| √ |

- |

- |

62.94% |

52.73% |

39.46% |

52.4% |

| √ |

√ |

- |

63.25% |

53.93% |

39.76% |

53.0% |

| √ |

√ |

√ |

63.53% |

55.31% |

39.95% |

53.6% |

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison of SCE-STISR and previous state-of-the-art methods using three recognisers, CRNN, MORAN and ASTER, the higher the recognition accuracy, the better the text super-resolution, boldface represents the optimal result, strikethrough represents the sub-optimal result, and avg represents the average recognition result.

Table 5.

Quantitative comparison of SCE-STISR and previous state-of-the-art methods using three recognisers, CRNN, MORAN and ASTER, the higher the recognition accuracy, the better the text super-resolution, boldface represents the optimal result, strikethrough represents the sub-optimal result, and avg represents the average recognition result.

| Method |

CRNN |

MORAN |

ASTER |

Easy

(%) |

Medium

(%) |

Hard(%) |

Avg(%) |

Easy(%) |

Medium(%) |

Hard(%) |

Avg(%) |

Easy(%) |

Medium(%) |

Hard(%) |

Avg(%) |

| Bicubic |

36.4 |

21.1 |

21.1 |

26.8 |

60.6 |

37.9 |

30.8 |

44.1 |

67.4 |

42.4 |

31.2 |

48.2 |

| SRCNN |

41.1 |

22.3 |

22.0 |

29.2 |

63.9 |

40.0 |

29.4 |

45.6 |

70.6 |

44.0 |

31.5 |

50.0 |

| SRResNet |

45.2 |

32.6 |

25.5 |

35.1 |

66.0 |

47.1 |

33.4 |

49.9 |

69.4 |

50.5 |

35.7 |

53.0 |

| EDSR |

42.7 |

29.3 |

24.1 |

32.7 |

63.6 |

45.4 |

32.2 |

48.1 |

72.3 |

48.6 |

34.3 |

53.0 |

| RCAN |

46.8 |

27.9 |

26.5 |

34.5 |

63.1 |

42.9 |

33.6 |

47.5 |

67.3 |

46.6 |

35.1 |

50.7 |

| CARN |

40.7 |

27.4 |

24.3 |

31.4 |

58.8 |

42.3 |

31.1 |

45.0 |

62.3 |

44.7 |

31.5 |

47.1 |

| HAN |

51.6 |

35.8 |

29.0 |

39.6 |

67.4 |

48.5 |

35.4 |

51.5 |

71.1 |

52.8 |

39.0 |

55.3 |

| TSRN |

52.5 |

38.3 |

31.4 |

41.4 |

70.1 |

55.3 |

37.9 |

55.4 |

75.1 |

56.3 |

40.1 |

58.3 |

| PCAN |

59.6 |

45.4 |

34.8 |

47.4 |

73.7 |

57.6 |

41.0 |

58.5 |

77.5 |

60.7 |

43.1 |

61.5 |

| TBSRN |

59.6 |

47.1 |

35.3 |

48.1 |

74.1 |

57.0 |

40.8 |

58.4 |

75.7 |

59.9 |

41.6 |

60.1 |

| Gestalt |

61.2 |

47.6 |

35.5 |

48.9 |

75.8 |

57.8 |

41.4 |

59.4 |

77.9 |

60.2 |

42.4 |

61.3 |

| TPGSR |

63.1 |

52.0 |

38.6 |

51.8 |

74.9 |

60.5 |

44.1 |

60.5 |

78.9 |

62.7 |

44.5 |

62.8 |

| TATT |

62.6 |

53.4 |

39.8 |

52.6 |

72.5 |

60.2 |

43.1 |

59.5 |

78.9 |

63.4 |

45.4 |

63.6 |

| C3-STISR |

65.2 |

53.6 |

39.8 |

53.7 |

74.2 |

61.0 |

43.2 |

59.5 |

79.1 |

63.3 |

46.8 |

64.1 |

| PerMR |

65.1 |

50.4 |

37.8 |

52.0 |

76.7 |

58.9 |

42.9 |

60.6 |

80.8 |

62.9 |

45.5 |

64.2 |

| MNTSR |

64.3 |

54.5 |

38.7 |

53.3 |

76.7 |

61.2 |

44.9 |

61.9 |

79.5 |

64.6 |

45.8 |

64.4 |

| SCE-STISR |

63.5 |

55.3 |

39.9 |

53.6 |

73.9 |

59.5 |

44.7 |

60.9 |

80.9 |

63.4 |

45.8 |

64.5 |

Table 6.

Quantitative comparisons on CRNN between SCE-STIR and previous state-of-the-art methods show that, the higher the PSNR and SSIM, the better the quality of the text super-resolution image, with red representing the optimal result and blue the sub-optimal result.

Table 6.

Quantitative comparisons on CRNN between SCE-STIR and previous state-of-the-art methods show that, the higher the PSNR and SSIM, the better the quality of the text super-resolution image, with red representing the optimal result and blue the sub-optimal result.

| Method |

PSNR |

SSIM |

| Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avg |

Easy |

Medium |

Hard |

avg |

| Bicubic |

22.35 |

18.98 |

19.39 |

20.35 |

0.7884 |

0.6254 |

0.6592 |

0.6961 |

| SRCNN |

23.48 |

19.06 |

19.34 |

20.78 |

0.8379 |

0.6323 |

0.6791 |

0.7227 |

| SRResNet |

24.36 |

18.88 |

19.29 |

21.03 |

0.8681 |

0.6406 |

0.6911 |

0.7403 |

| EDSR |

24.26 |

18.63 |

19.14 |

20.68 |

0.8633 |

0.6440 |

0.7108 |

0.7394 |

| RCAN |

22.15 |

18.81 |

19.83 |

20.26 |

0.8525 |

0.6465 |

0.7227 |

0.7406 |

| CARN |

22.70 |

19.15 |

20.02 |

20.62 |

0.8384 |

0.6412 |

0.7172 |

0.7323 |

| HAN |

23.30 |

19.02 |

20.16 |

20.95 |

0.8691 |

0.6537 |

0.7387 |

0.7596 |

| TSRN |

25.07 |

18.86 |

19.71 |

21.42 |

0.8897 |

0.6676 |

0.7302 |

0.7690 |

| PCAN |

24.57 |

19.14 |

20.26 |

21.49 |

0.8830 |

0.6781 |

0.7475 |

0.7752 |

| TBSRN |

23.46 |

19.17 |

19.68 |

20.91 |

0.8729 |

0.6455 |

0.7452 |

0.7603 |

| Gestalt |

23.95 |

18.58 |

19.74 |

20.76 |

0.8611 |

0.6621 |

0.7520 |

0.7584 |

| TPGSR |

23.73 |

18.68 |

20.06 |

20.97 |

0.8805 |

0.6738 |

0.7440 |

0.7719 |

| TATT |

24.72 |

19.02 |

20.31 |

21.52 |

0.9006 |

0.6911 |

0.7703 |

0.7930 |

| C3-STISR |

24.71 |

19.03 |

20.09 |

21.51 |

0.8545 |

0.6674 |

0.7639 |

0.7721 |

| PerMR |

24.89 |

18.98 |

20.42 |

21.43 |

0.9102 |

0.6921 |

0.7658 |

0.7894 |

| MNTSR |

24.93 |

19.28 |

20.38 |

21.50 |

0.9173 |

0.6860 |

0.7806 |

0.7946 |

| SCE-STISR |

24.99 |

19.13 |

20.78 |

21.84 |

0.9038 |

0.6955 |

0.7859 |

0.7951 |

Table 7.

Validating model generalisation on five text recognition datasets including IC13, IC15, CUTE80, SVT and SVTP.

Table 7.

Validating model generalisation on five text recognition datasets including IC13, IC15, CUTE80, SVT and SVTP.

| Method |

STR Datasets |

| IC13 |

IC15 |

CUTE80 |

SVT |

SVTP |

| Bicubic |

9.6% |

10.1% |

35.8% |

3.3% |

10.2% |

| SRResNet |

11.4% |

13.4% |

50.5% |

9.3% |

13.8% |

| TSRN |

15.6% |

18.6% |

66.9% |

10.0% |

16.4% |

| TBSRN |

17.7% |

21.3% |

75.0% |

12.2% |

17.4% |

| TPGSR |

22.7% |

24.2% |

72.6% |

13.7% |

16.5% |

| TATT |

27.6% |

28.6% |

74.7% |

14.2% |

25.9% |

| C3-STISR |

24.7% |

22.7% |

71.5% |

10.2% |

17.7% |

| SCE-STISR |

28.9% |

30.7% |

74.9% |

15.1% |

26.5% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).