Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Albert Rift in Uganda is a significant geological and petroleum exploration frontier within the East African Rift System. The basin has been comprehensively analyzed via thorough literature survey, seismic data analysis, well log interpretations, and basin and petroleum systems modeling to examine the complex interactions of tectonics, sedimentation, and hydrocarbon generation and expulsion within the rift basin. Our findings reveal a detailed tectonostratigraphic framework with multiple Neogene to Quaternary depositional sequences and structural features influencing hydrocarbon maturation, generation and expulsion. Key stratigraphic units are identified, highlighting their contributions to a viable petroleum system present within the rift basin. The Albert Rift is a Neogene petroleum system that is currently generating and expelling hydrocarbons to various potential traps. The study underscores the impact of rift-related tectonics on the basin architecture, source-reservoir-seal rock distribution within a young rift basin. Our research enhances new understanding of the Albert Rift's geological history and petroleum systems, offering valuable insights for future petroleum exploration strategies. By integrating tectonostratigraphic and petroleum system analysis, we provide a robust model applicable to similar rift basins worldwide.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Developing a Tectonostratigraphic Framework

2.2. Petroleum Potential Evaluation

3.2.1. Southern Lake Albert Lithostratigraphy

2.2.2. Source Rock Characterization

2.2.3. Basin and Petroleum Systems Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Albert Rift Regional Tectonostratigraphy

3.2. Petroleum Potential of the Albert Rift

3.2.1. South Lake Albert Lithostratigraphy

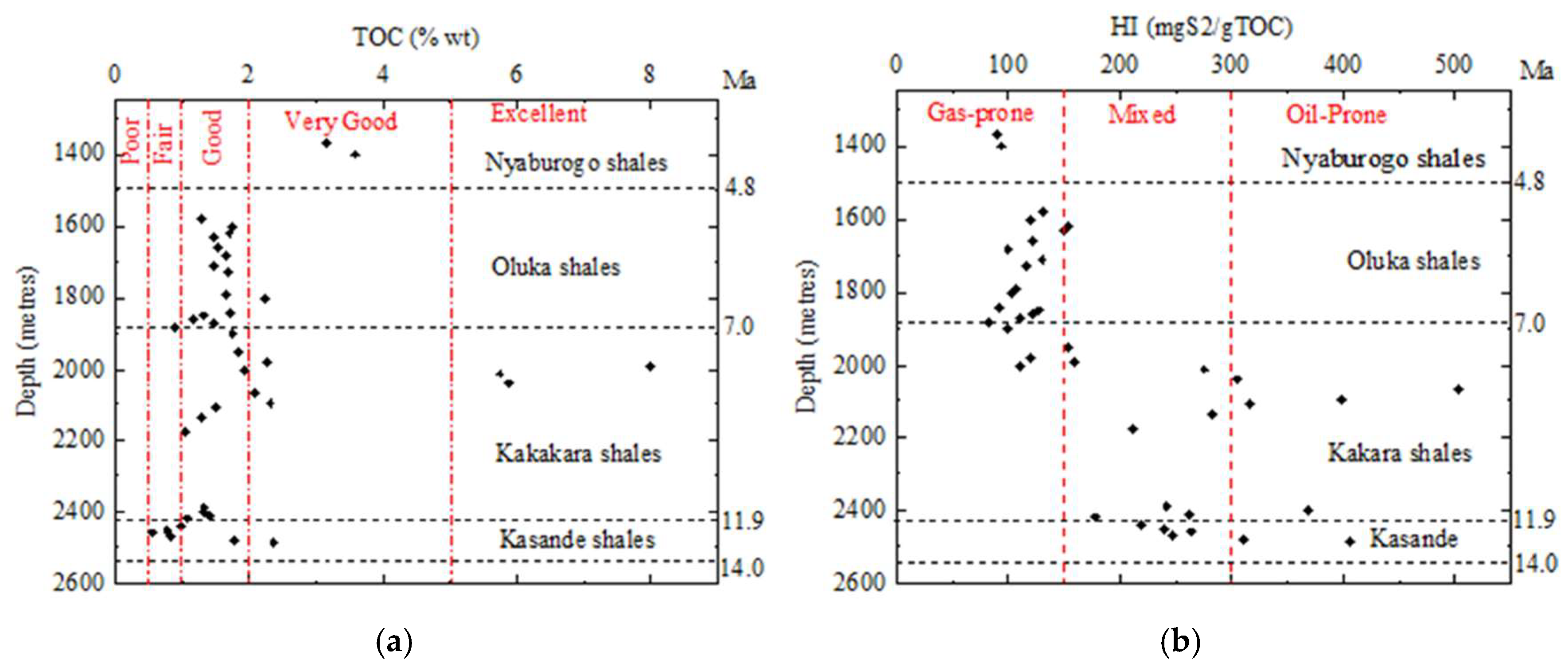

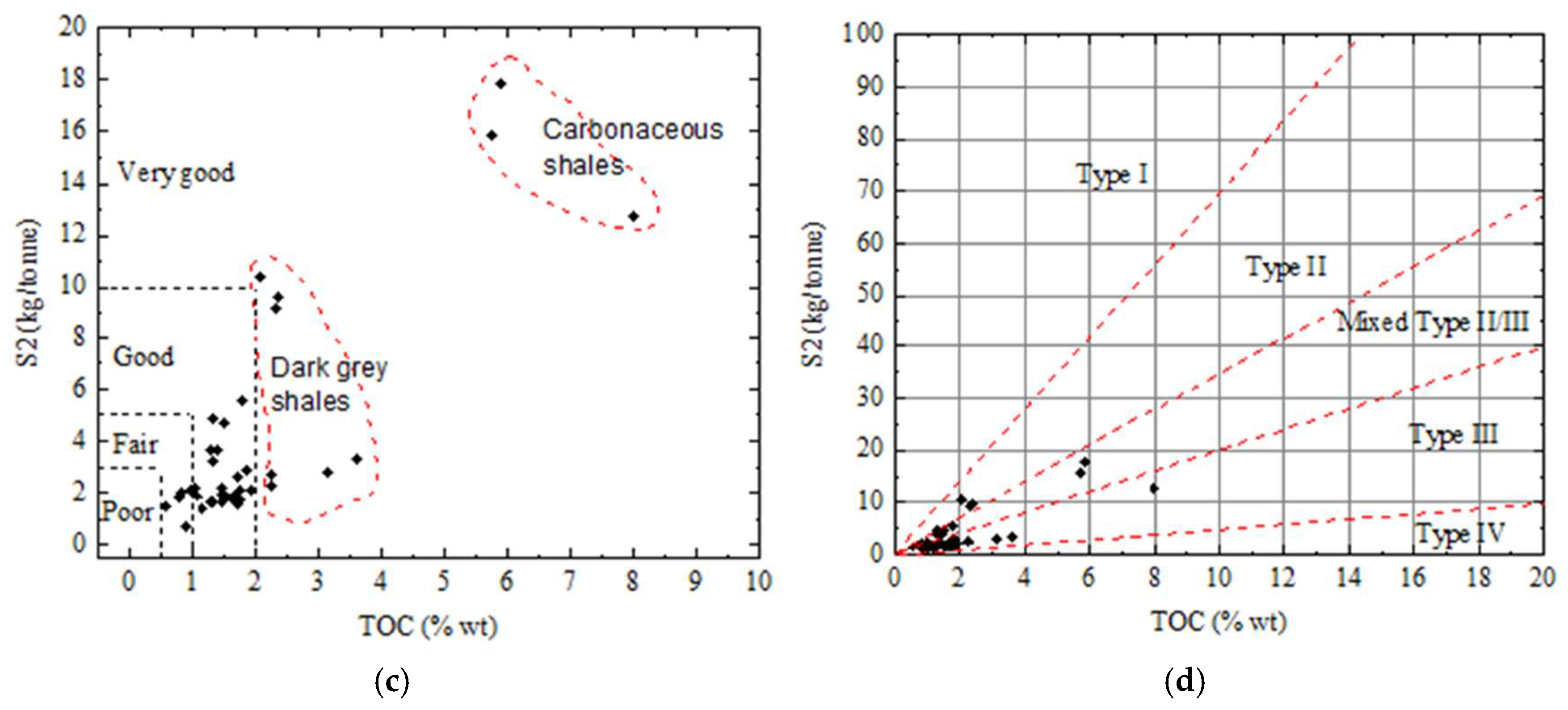

3.2.2. Source Rock Characteristics

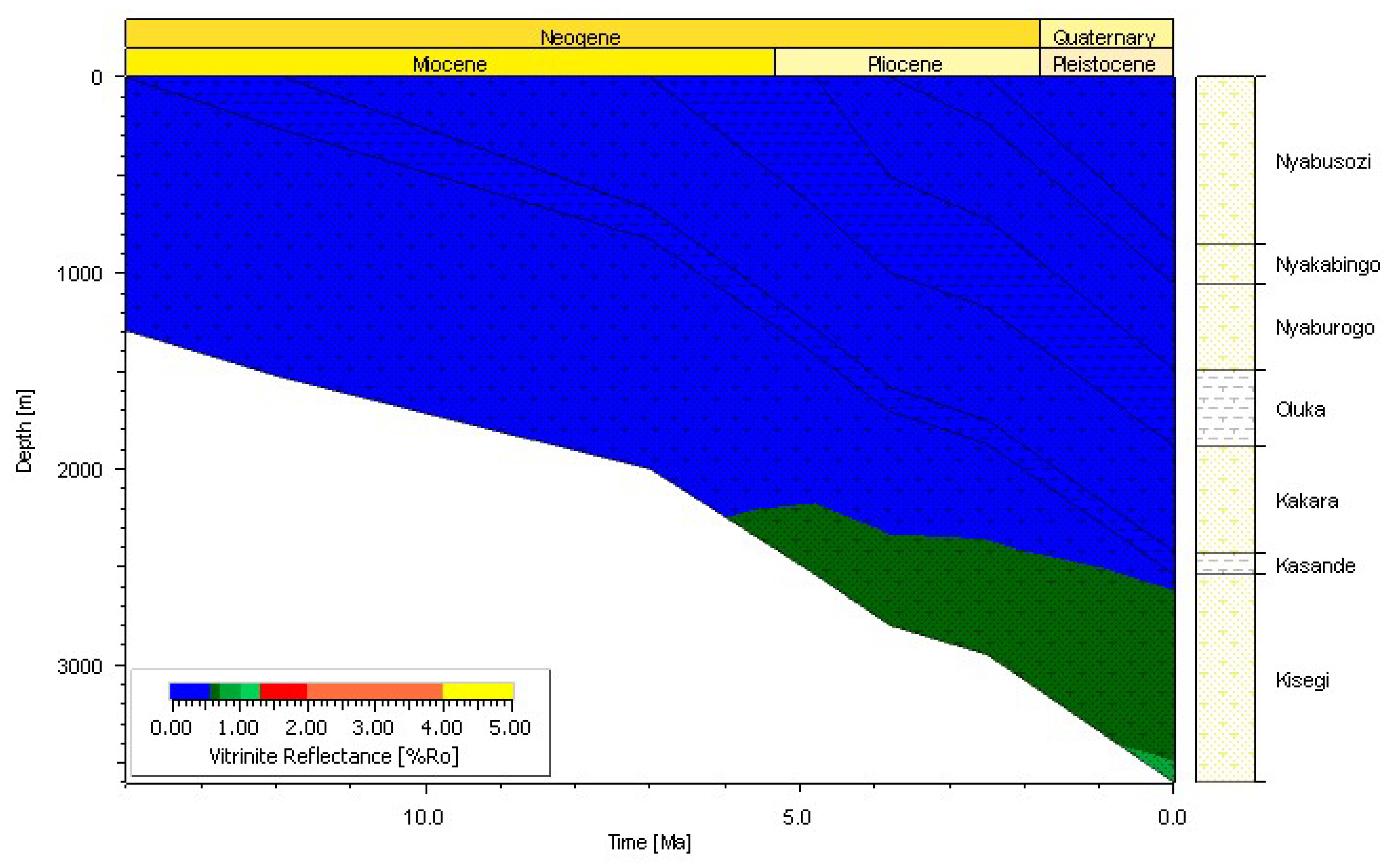

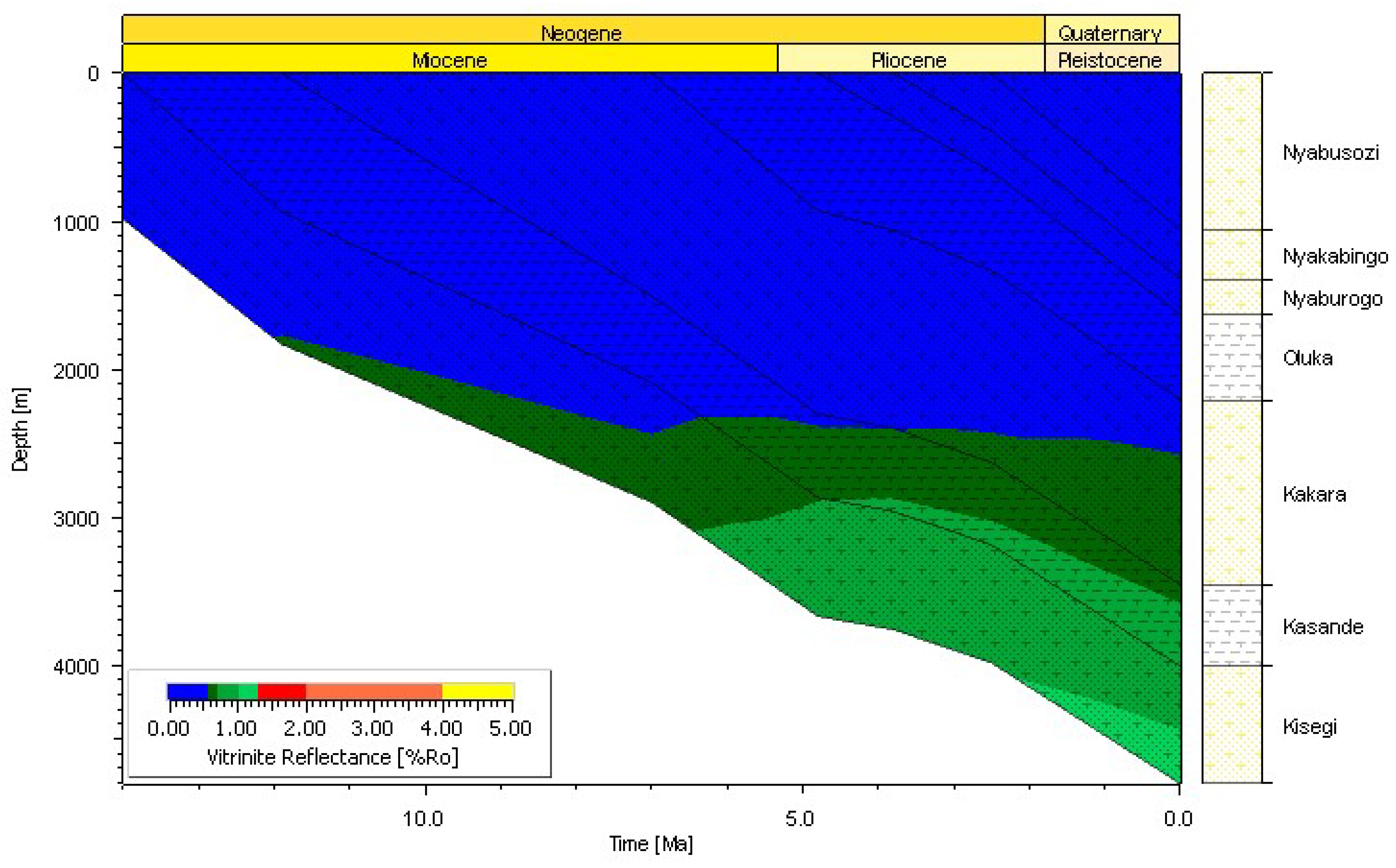

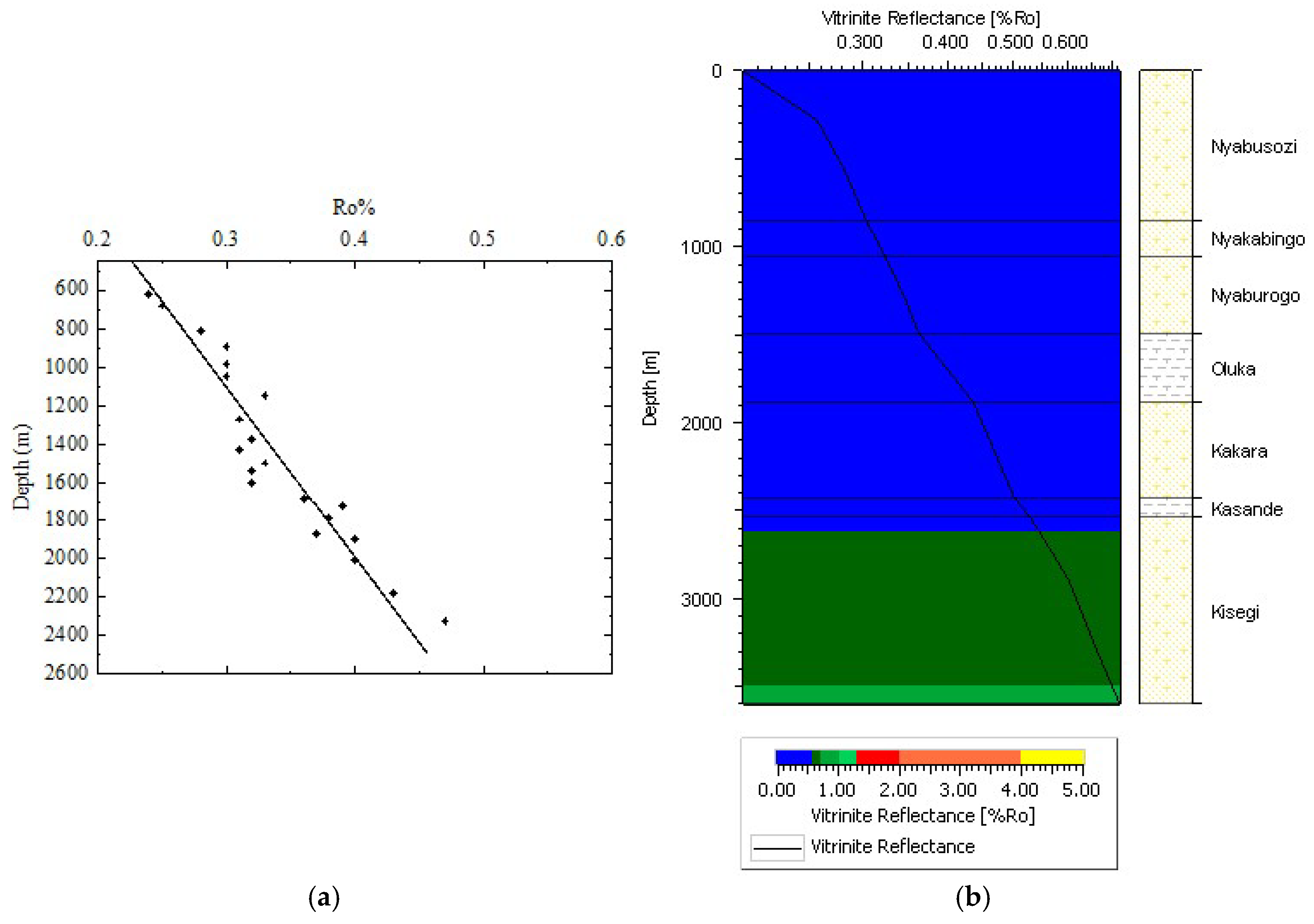

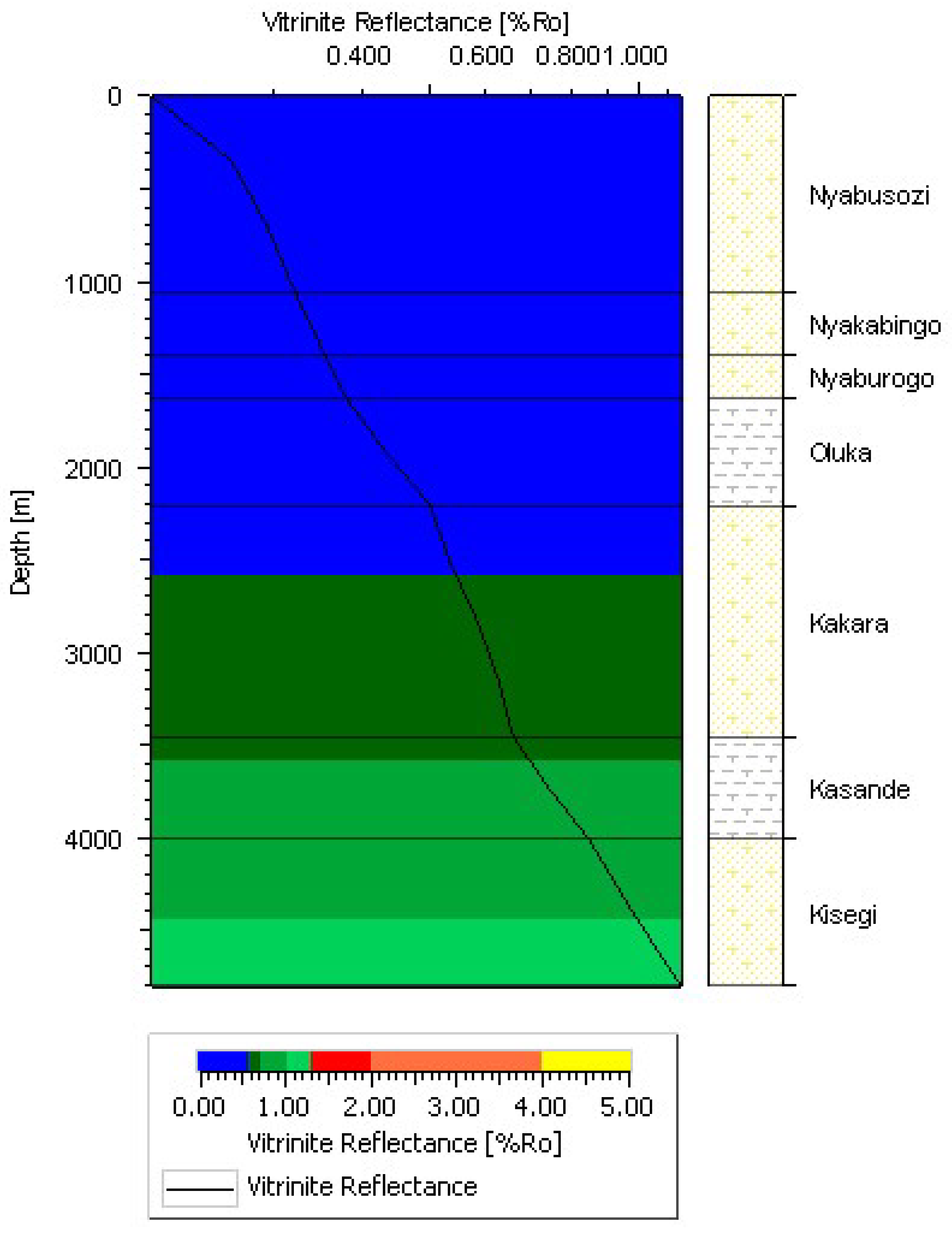

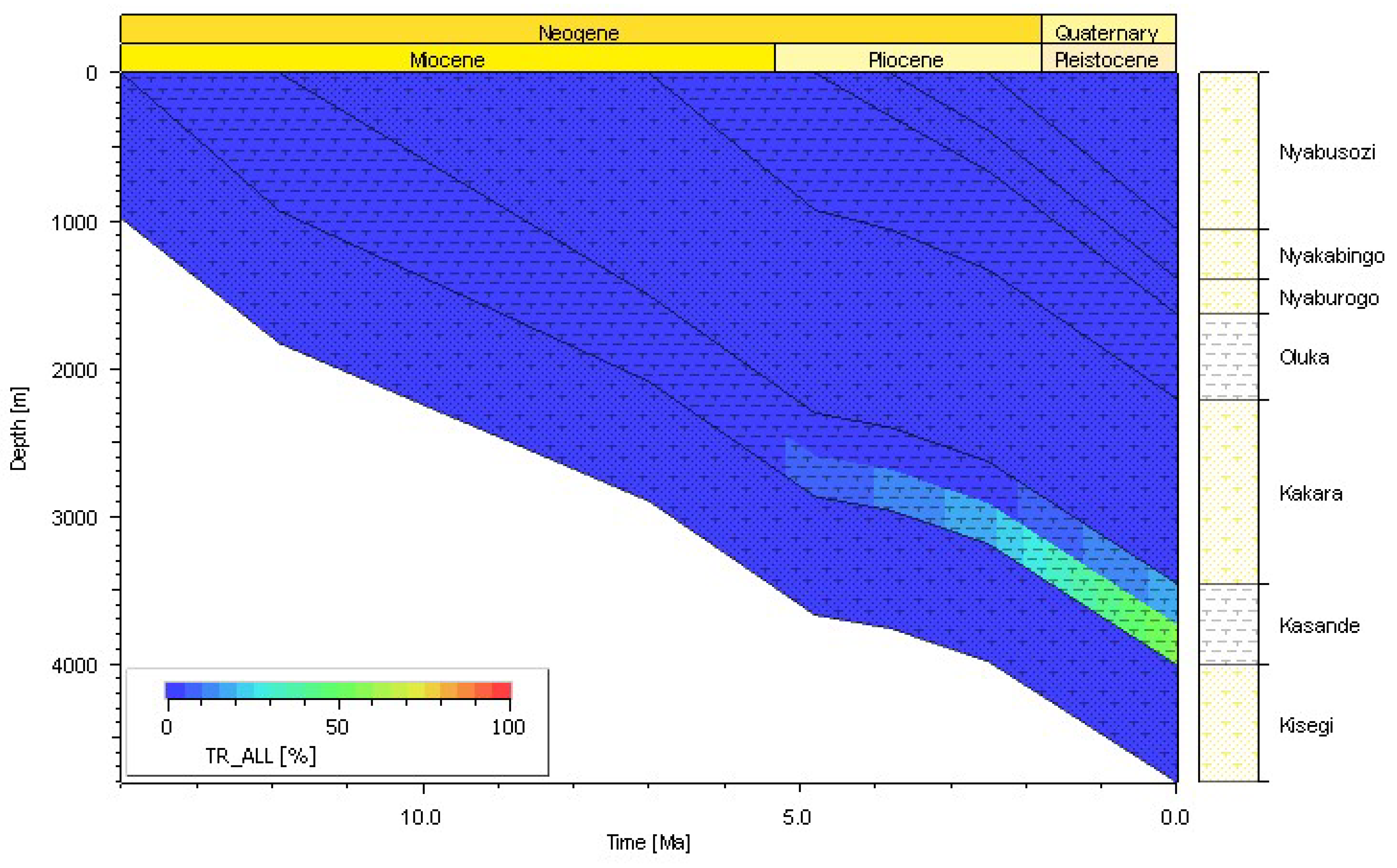

3.2.3. Burial and Thermal History

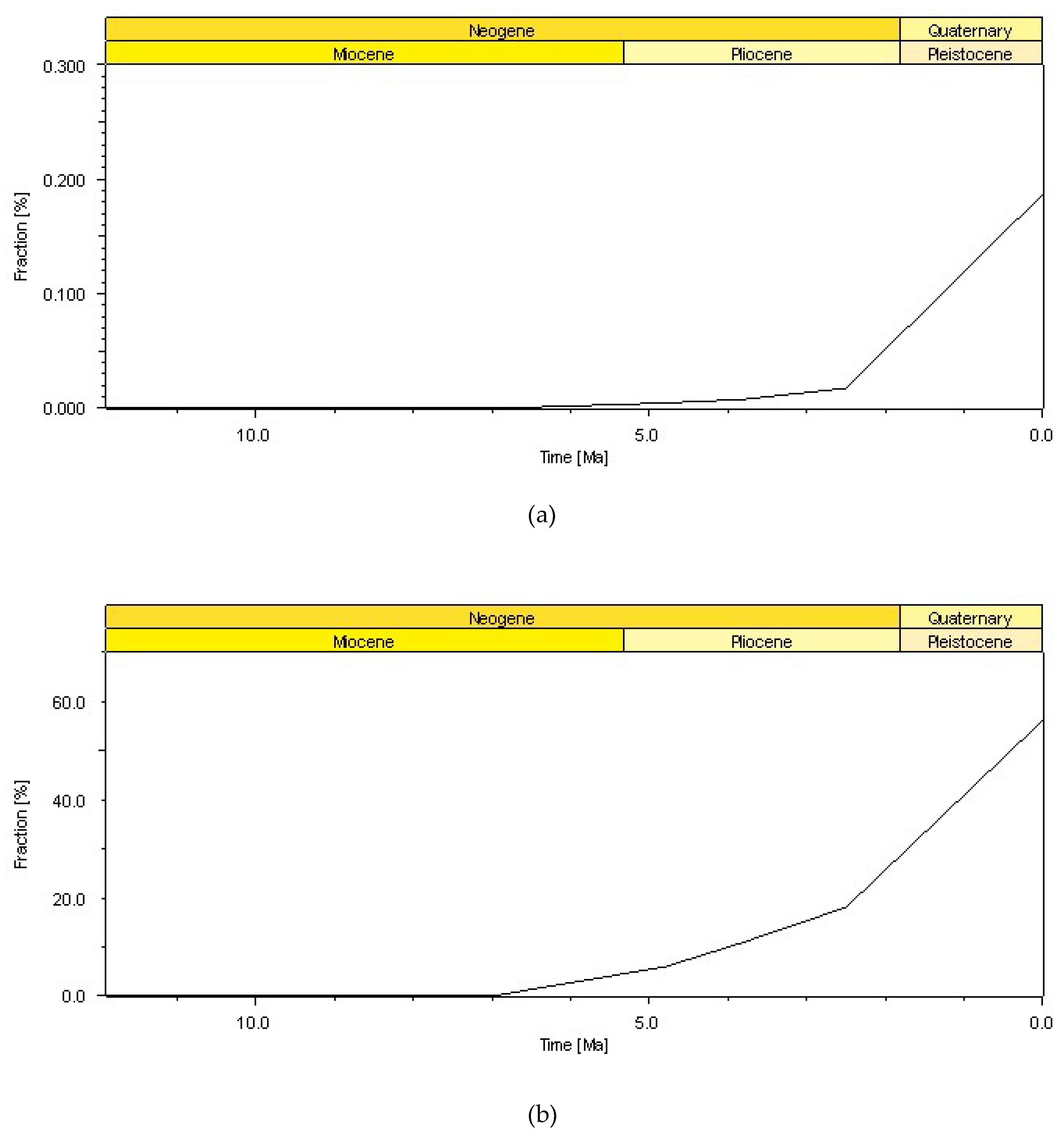

3.2.4. Hydrocarbon Transformation

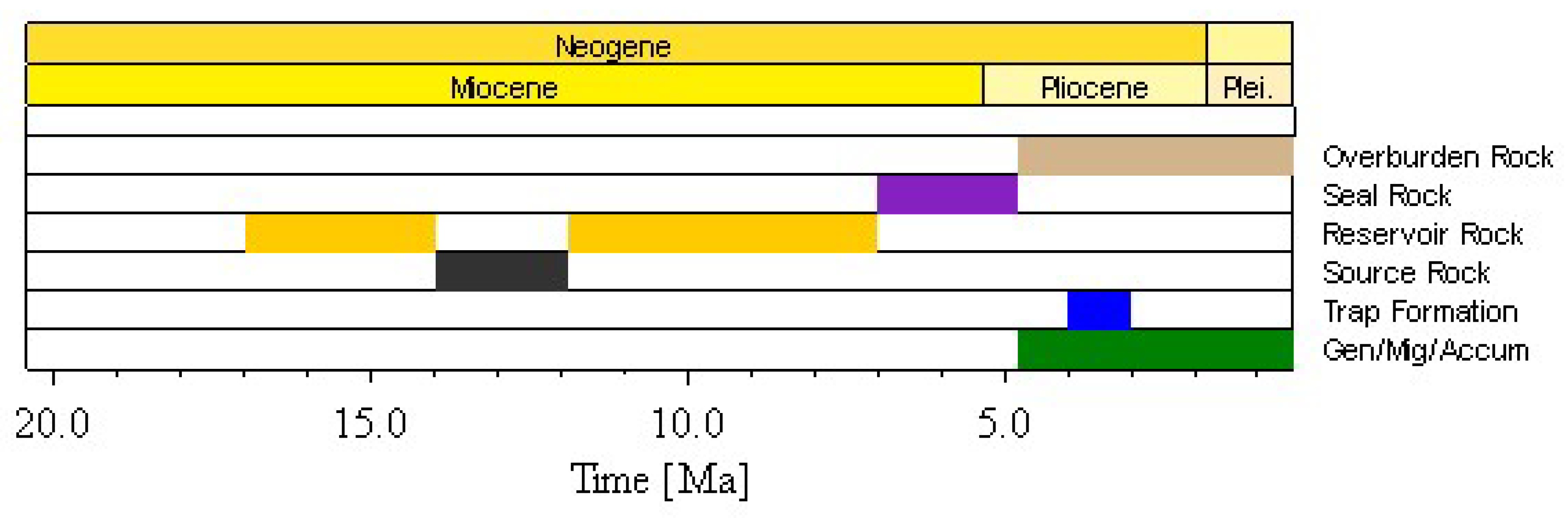

3.2.5. Petroleum System Elements

4. Discussion

4.1. Tectonostratigraphic Evolution

4.2. Source Rock Potential and Depositional Environment

4.3. Subsidence History

4.4. Thermal Maturity, Hydrocarbon Generation and Expulsion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abeinomugisha, D.; Njabire, N. Transfer Zones and Hydrocarbon Accumulation in the Albertine Graben of the East African Rift System. AAPG Annu. Conv. Exhib. 2012, 10401, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderer, M.; Schneider, S.; Stutenbecker, L. Unravelling the evolution of a continental rift by a multi-proxy provenance study (Albertine Rift, Uganda). Int J Earth Sci. 2024, 113, 1317–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, M.R. The origins of lacustrine oil source rocks: evidence from the lakes of tropical Africa. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 1988, 40(1), 29-43. [CrossRef]

- Katz, B. J. Controls on distribution of lacustrine source rocks through time and space. In: Katz, B.J (Ed). Lacustrine basin exploration: Case studies and modern analogs. Memoir. 1990, 50, 61–76.

- Rosendahl, B. R.; Kilembe, E.; Kaczmarick, K. Comparison of the Tanganyika, Malawi, Rukwa and Turkana Rift zones from analyses of seismic reflection data. Tectonophysics. 1992, 213(1-2), 235-256. [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C. A. Deltas of the Lake Malawi rift, East Africa: Seismic expression and exploration implications: AAPG Bulletin. 1995, 79(11), 1679–1697. [CrossRef]

- Soreghan, M. J.; Cohen, A.S. Textural and compositional variability across littoral segments of Lake Tanganyika: The effect of asymmetric basin structure on sedimentation in large rift lakes: AAPG Bulletin. 1996, 80, 382–409.

- Demaison, G.J.; Moore, G.T. Anoxic environments and oil source bed genesis. Org. Geochem. 1980, 2, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, T.; Scholz, C.A.; McGlue, M.M. Structure and Stratigraphy of the Lake Albert Rift, East Africa Observations from Seismic Reflection and Gravity Data, in: Lacustrine Sandstone Reservoirs and Hydrocarbon Systems. AAPG Special Volumes. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Morley, C.K.; Nelson, R.A.; Patton, T.L.; Munn, S.G. Transfer zones in the East African rift system and their relevance to hydrocarbon exploration in rifts. AAPG bulletin. 1990, 74, 1234–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgregor, D. History of the development of the East African Rift System: A series of interpreted maps through time. J Afr Earth Sci. 2015, 101, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahao, D.; Warme, J. E. Lacustrine and associated deposits in a rifted continental margin: Lower Cretaceous Lagoa Feia Formation, Campos Basin, offshore Brazil: In B. J. Katz, (Ed.). Lacustrine basin exploration: Case studies and modern analogs: AAPG Memoir. 1990, 50, 287– 305.

- McHargue, T. R. Stratigraphic development of proto-South Atlantic rifting in Cabinda, Angola: A petroliferous lake basin. In B. J. Katz (Ed.). Lacustrine basin exploration: Case studies and modern analogs: AAPG Memoir. 1990, 50, 307–326.

- Pickford, M. Field Report – Western Rift. Collège de France, Paris. Unpublished field report. 2011, 1-30.

- Pickford, M.; Senut, B. Western Rift Valley. Collège de France, Paris. Unpublished field report. 2012, 1-61.

- Lukaye, J.; Worsley, D.; Kiconco, L.; Nabbanja, P.; Abeinomugisha, D.; Amusugut, C.; Njabire, N.; Nuwagaba, R.; Mugisha, F.; Ddungu, T.; Sserubiri, T.; Sempala, V. Developing a coherent stratigraphic scheme of the Albertine Graben-East, Africa. Glob. j. Earth sci. eng. 2016, 6, 264–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaye, J.; Etano, G.; Abbott, G. Molecular organic geochemistry of crude oils from the Albertine Graben, Uganda: possible implications on the expulsion of the oils from the source rocks. Glob. j. Earth sci. eng. 2017, 7.

- Pickford, M.; Senut, B.; Hadoto, D. Geology and palaeobiology of the Albertine Rift valley, Uganda-Zaire. Orléans, France: CIFEG. 1993, 1, 1-189.

- Bauer, F.U.; Glasmacher, U.A.; Ring, U.; Grobe, R.W.; Mambo, V.S.; Starz, M. Long-term cooling history of the Albertine Rift: new evidence from the western rift shoulder, DR Congo. Int J Earth Sci. 2016, 105, 1707–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jess, S.; Koehn, D.; Fox, M.; Enkelmann, E.; Sachau, T.; Aanyu. Paleogene initiation of the Western branch of the east African Rift: The uplift history of the Rwenzori Mountains, Western Uganda. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 552, 116593. [CrossRef]

- Michon, L.; Famin, V.; Quidelleur, X. Evolution of the East African Rift System from trap-scale to plate-scale rifting. Earth Sci Rev. 2022, 231, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Hornung, J.; Hinderer, M. Evolution of the western East African Rift System reflected in provenance changes of Miocene to Pleistocene synrift sediments (Albertine Rift, Uganda). Sediment. Geol. 2016, 343, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaye, J.M. Biostratigraphy and palynofacies of four exploration wells from the Albertine Graben, Uganda. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Search & Discovery Article. 2009, 50169.

- Roller, S.; Hornung, J.; Hinderer, M.; Ssemmanda, I. Middle Miocene to Pleistocene sedimentary record of rift evolution in the southern Albert Rift (Uganda). Int J Earth Sci. 2010, 99, 1643–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.; Guillocheau, F.; Robin, C.; Dauteuil, O.; Nalpas, T.; Pickford, M.; Bez, M. Deformation and sedimentary evolution of the Lake Albert rift (Uganda, East African Rift System). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 86, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukaye, J.; Okello, M. Geochemical Characterization and Correlation of Crude Oils and Potential Source Rocks from the Semliki, Southern Lake Albert and Kaisotonya basins in the Albertine Graben, Uganda. In: International Conference and Exhibition, Melbourne, Australia 13-16 September. Society of Exploration Geophysicists and American Assoc. AAPG. 2015, 557-557. [CrossRef]

- Klemme, H. D.; Ulmishek, G. F. Effective petroleum source rocks of the world: stratigraphic distribution and controlling depositional factors. AAPG Bulletin. 1991, 75, 1809–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Tissot, B. P.; Pelet, R.; Ungerer, P. Thermal History of Sedimentary Basins, Maturation Indices, and Kinetics of Oil and Gas Generation. AAPG. 1987, 71, 1445–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welte, D. H.; Yalçin, M. N. Basin Modelling-A New Comprehensive Method in Petroleum Geology. Org. Geochem. 1988, 13, 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Ungerer, P.; Burrus, J.; Doligez, B.; Chenet, P. Y.; Bessis, F. Basin Evaluation by Integrated Two-Dimensional Modeling of Heat Transfer, Fluid Flow, Hydrocarbon Generation, and Migration. AAPG. 1990, 74, 309–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debra, K. H.; Michael, L.; Laura, N.R.R.; Mitchell, E.H. Petroleum system Modeling Capacities for Use in Oil and gas Resource assessments. U.S. Department of the Interior. U.S. Geological Survey. Open-File Report. 2006, 1024.

- Hantschel, T.; Kauerauf, A.I. Fundamentals of basin and petroleum systems modeling. Springer Science & Business Media. 2009, 476.

- Peters, K.E.; Schenk, O.; Hosford, S. A.; Wygrala, B.; Hantschel, T. Basin and petroleum system modeling. Springer handbook of petroleum technology. 2017, 381–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, F.; Scheirer, A.H.; Peters, K.E. Past, present, and future of basin and petroleum system modeling. AAPG Bulletin. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tugume, F.A.; Nyblade, A.A. The depth distribution of seismicity at the northern end of the Rwenzori mountains: implications for heat flow in the western branch of the East African Rift System in Uganda. South Afr. J. Geol. 2009, 112, 261-276. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.J.; Burnham, A.K. Evaluation of a simple model of vitrinite reflectance based on chemical kinetics. AAPG bulletin. 1990, 74, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frakes, L. A. Climates throughout Geological Time. Amsterdam, Elsevier. 1979, 1 - 310.

- Hardenbol, J.; Thierry, J.; Farley, M.; Thierry, J.; De Graciansky, P. C.; Vail, P. R. Mesozoic and Cenozoic Stratigraphy of European Basins. SEPM Special Publication. 1998, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Dembicki, H. Practical petroleum geochemistry for exploration and production. Elsevier. 2017, 1-331.

- Mechie, J.; Keller, G.R.; Prodehl, C.; Khan, M.A.; Gaciri, S.J. A model for the structure, composition and evolution of the Kenya rift. Tectonophysics. 1997, 278, 95-119. [CrossRef]

- Ebinger, C.J.; Casey, M. Continental breakup in magmatic provinces: An Ethiopian example. Geological Journal. 2001, 29, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, R.; Beyth, M. The Afar Depression: interpretation of the 1960–2000 earthquakes. Geophys. J. Int, 2003, 155, 715-732. [CrossRef]

- Shaban, S.N.; Scholz, C.A.; Muirhead, J.D.; Wood, D.A. The stratigraphic evolution of the Lake Tanganyika Rift, East Africa: Facies distributions and paleo-environmental implications. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 2021, 575, 110474. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.U.; Glasmacher, U.A.; Ring, U.; Schumann, A.; Nagudi, B. Thermal and exhumation history of the central Rwenzori Mountains, Western rift of the east African rift system, Uganda. Int J Earth Sci. 2010, 99, 1575–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, C.J.; Newth, I, R.; Abeinomugisha, D.; Tumushabe, W.M.; Twinomujuni, L. Geology and stratigraphy of the south-eastern Lake Edward basin (Petroleum Exploration Area 4B), Albertine Rift Valley, Uganda. J. Maps. 2016, 12, 237–248. [CrossRef]

- Mutebi, S.; Sen, S.; Sserubiri, T.; Rudra, A.; Ganguli, S. S.; Radwan, A. E. Geological characterization of the Miocene–Pliocene succession in the Semliki Basin, Uganda: Implications for hydrocarbon exploration and drilling in the East African Rift System. Nat. Resour. Res. 2021, 30, 4329–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissot, B.P.; Welte, D.H. Petroleum formation and occurrence. Springer Science & Business Media. 2013, 1-679.

- Morley, C.K. Tectonic settings of continental extensional provinces and their impact on sedimentation and hydrocarbon prospectivity. In: Renaut R, W., Ashley. G, M (Eds.). Sedimentation in Continental Rifts. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Peters, K. E.; Cassa, M. R. Applied Source Rock Geochemistry. In: The Petroleum System – From Source to Trap. AAPG Memoir. 1994, 60, 93-120.

- Doust, H.; Omatsola, E. Niger Delta. In: Edwards, J. D., & Santogrossi, P. A. (Eds.). Divergent/Passive Margin Basins, AAPG Memoir. 1990, 48, 239-248.

- Cornford, C. Source Rocks and Hydrocarbons of the North Sea. In: Glennie, K. W. (Ed.). Petroleum Geology of the North Sea. Blackwell Publishing. 1998, 376-462.

- McClay, K.; Khalil, S.M.; Bosworth, W.; Gussinye, M.P. Tectono-stratigraphic evolution of the northwestern Red Sea, Egypt–a review. Rifting and Sediments in the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf Regions .2024, 9-36.

- Van Damme, D.; Pickford M. The late Cenozoic ampullariidae (mollusca, gastropoda) of the Albertine rift valley (Uganda-Zaire). Hydrobiologia. 1995, 316:1–32. [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, D.; Pickford, M. The late Cenozoic Thiaridae (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Cerithioidea) of the Albertine rift valley (Uganda-Congo) and their bearing on the origin and evolution of the Tanganyikan thalassoid malacofauna. Hydrobiologia. 2003, 498:1– 83. [CrossRef]

- Kato, V. Geothermal exploration in Uganda – Status report. Papers presented at “SDG Short Course II on Exploration and Development of Geothermal Resources”, organized by UNU-GTP, GDC and KenGen, at Lake Bogoria and Lake Naivasha, Kenya, 2016, 1-24.

- EAGER. Structural geology at Panyimur and Buranga. East Africa Geothermal Energy Facility, report U-23-D02. 2017.

- Hinz, N.; Cumming, B.; Sussman, D. Exploration of fault-related deep-circulation geothermal resources in the western branch of the East African Rift System: Examples from Uganda and Tanzania. Proceedings of the 7th African Rift Geothermal Conference, Kigali, Rwanda, 2018, 1-16.

- Kahwa, E. Geothermal exploration in Uganda – Status report. Papers presented at “SDG Short Course II on Exploration and Development of Geothermal Resources”, organized by UNU-GTP, GDC and KenGen, at Lake Bogoria and Lake Naivasha, Kenya, 2021, 1-11.

| Layer |

Age From (ma) |

To (ma) |

Thickness Top (m) |

Base (m) | |

| Nyabusozi | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 848 | |

| Nyakabingo | 2.5 | 3.8 | 848 | 1055 | |

| Nyaburogo | 3.8 | 4.8 | 1055 | 1492 | |

| Oluka | 4.8 | 7 | 1492 | 1883 | |

| Kakara | 7 | 11.9 | 1883 | 2425 | |

| Kasande | 11.9 | 14 | 2425 | 2540 | |

| Kisegi | 14 | 17 | 2540 | 3600 |

| Layer |

Thickness Top (m) |

Bottom (m) |

Age Top (Ma) |

Bottom (Ma) | |

| Nyabusozi | 0 | 1056 | 0 | 2.5 | |

| Nyakabingo | 1056 | 1392 | 2.5 | 3.8 | |

| Nyaburogo | 1392 | 1632 | 3.8 | 4.8 | |

| Oluka | 1632 | 2208 | 4.8 | 7 | |

| Kakara | 2208 | 3456 | 7 | 11.9 | |

| Kasande | 3456 | 4008 | 11.9 | 14 | |

| Kisegi | 4008 | 4800 | 14 | 17 | |

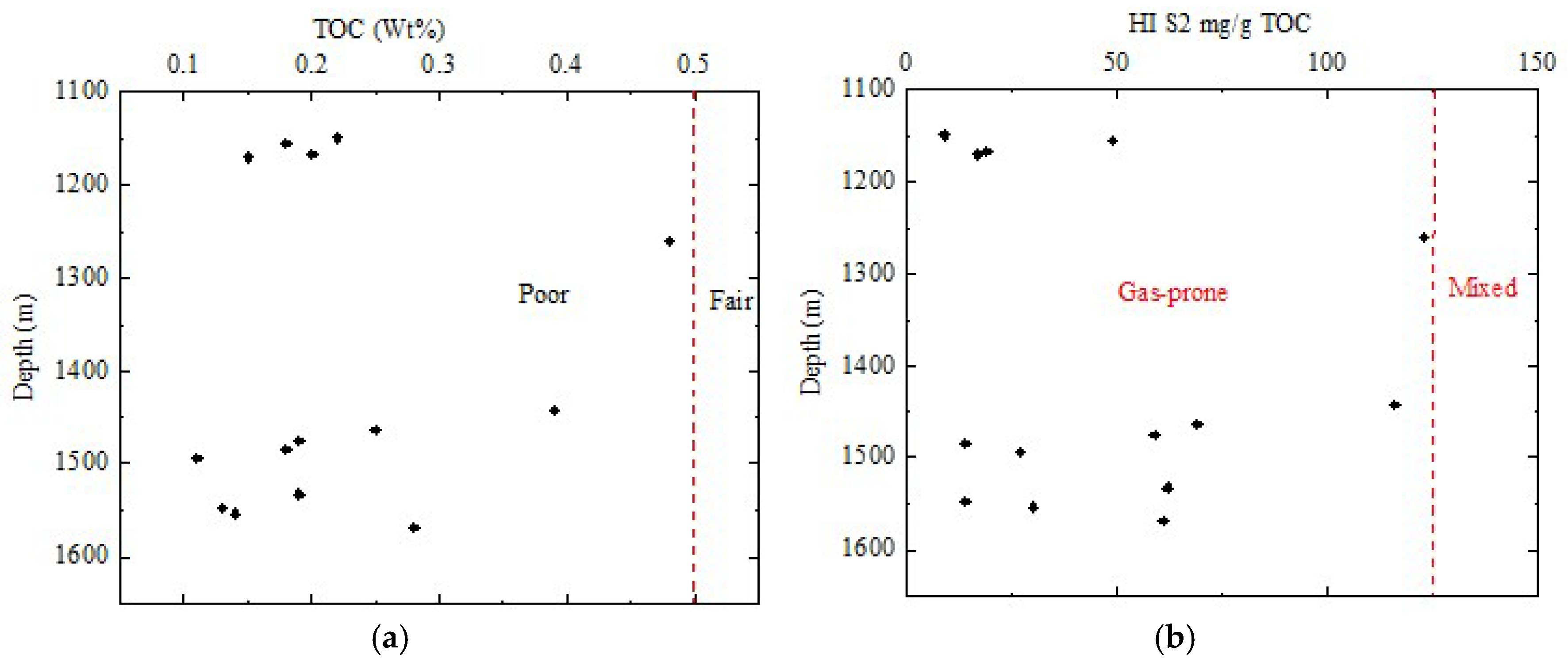

| Depth(m) | Quantity (mg) | TOC (%) | S1 (mg/g) | S2 (mg/g) | Tmax (0C) | TpkS2 (0C) | PI | HI |

| 1146-1149 | 46.9 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.02 | 404 | 441 | 0.10 | 9.00 |

| 1152-1155 | 52.8 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.09 | 421 | 457 | 0.03 | 49.00 |

| 1164-1167 | 57.8 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 345 | 382 | 0.28 | 19.00 |

| 1167-1170 | 53.4 | 0.15 | 0 | 0.03 | 418 | 455.00 | 0.12 | 17.00 |

| 1257-1260 | 46.7 | 0.48 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 413 | 450 | 0.01 | 123.00 |

| 1440-1443 | 53.8 | 0.39 | 0 | 0.46 | 421 | 458 | 0.01 | 116.00 |

| 1461-1464 | 58.9 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 422 | 458 | 0.05 | 69.00 |

| 1473-1476 | 53.9 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 424 | 461 | 0.14 | 59.00 |

| 1482-1485 | 54.7 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.03 | 403 | 440 | 0.09 | 14.00 |

| 1491-1494 | 59.6 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 415 | 452 | 0.32 | 27.00 |

| 1530-1533 | 49.6 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 382 | 419 | 0.04 | 62.00 |

| 1545-1548 | 44.9 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.02 | 354 | 391.00 | 0.15 | 14.00 |

| 1551-1554 | 45.8 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 411 | 448 | 0.12 | 30.00 |

| 1563-1569 | 55.3 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 414 | 451 | 0.14 | 61.00 |

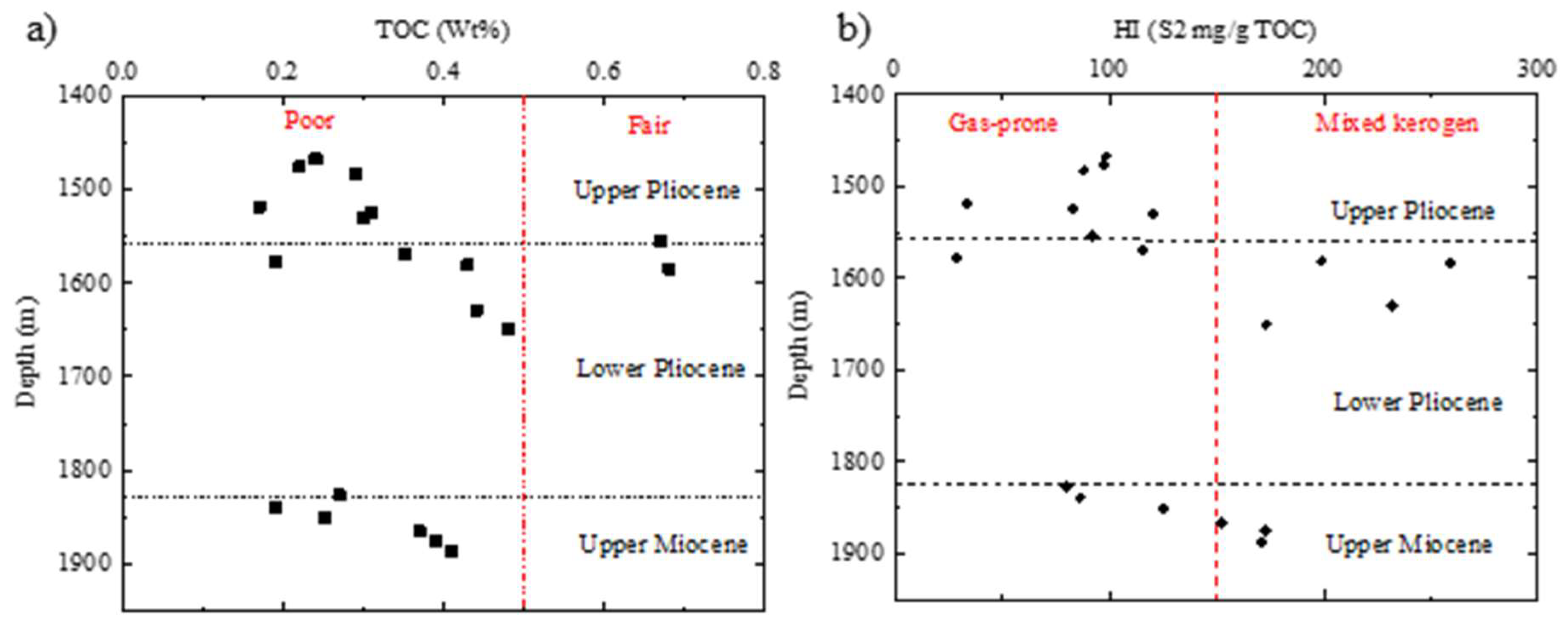

| Depth(m) | Quantity (mg) | TOC (%) | S1 (mg/g) | S2 (mg/g) | Tmax (0C) | TpkS2 (0C) | PI | HI |

| 1467.00 | 50.8 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 407 | 444 | 0.07 | 98 |

| 1476.00 | 44.9 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 414 | 451 | 0.07 | 97 |

| 1482.00 | 58.4 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 419 | 456.00 | 0.03 | 88 |

| 1518.00 | 41.9 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 418 | 455 | 0.06 | 33 |

| 1524.00 | 55.4 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 412.00 | 449.00 | 0.03 | 83 |

| 1530.00 | 60.8 | 0.30 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 414 | 451 | 0.06 | 120 |

| 1554.00 | 52.2 | 0.67 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 433 | 470 | 0.04 | 92 |

| 1569.00 | 61.4 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 413.00 | 450.00 | 0.06 | 115 |

| 1578.00 | 42.8 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 422 | 458 | 0.07 | 28 |

| 1581.00 | 60.6 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 421 | 458 | 0.05 | 199 |

| 1584.00 | 58.9 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 1.75 | 420 | 457 | 0.11 | 259 |

| 1629.00 | 57.6 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 1.03 | 411 | 448 | 0.13 | 232 |

| 1650.00 | 44.8 | 0.48 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 415 | 452.00 | 0.02 | 173 |

| 1827.00 | 52.3 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.22 | 416 | 453 | 0.03 | 80 |

| 1839.00 | 54.9 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 403 | 440 | 0.05 | 86 |

| 1851.00 | 50.8 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 415 | 451.00 | 0.05 | 125 |

| 1866.00 | 54.2 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.56 | 413 | 450.00 | 0.03 | 152 |

| 1875.00 | 54.1 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 419 | 455 | 0.08 | 173 |

| 1887.00 | 44.9 | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.7 | 409 | 445 | 0.12 | 171 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).