2.1. Smooth and Deterministic: The Continua

At a certain point of their history, physicists accepted that the world is made of very tiny systems, as molecules, atmos, electrons, and after all elementary particles, that render

matter granular. However, since a couple of centuries at that moment, they had already developed a picture of macroscopic material systems as

continua, i.e. extended distributions of matter occupying finite portions of the physical space and experiencing and applying forces all over their volume, and surface. From the invention of Calculus, physicists had given a precise mathematical meaning to the Latin proverb

Natura non facit saltus, taken by Leibniz as a manifesto for modelling physical systems: any physical quantity should have a

-dependence on the variables it is function of. This “phylosophy of non-roughness” applies to the description of continua stating that if a macroscopic continuum

occupies a volume

at a certain time

t, any positional quantity

describing its state (e.g., mass density, velocity, pressure...) must be

a smooth field all over

:

being the factor “

” encoding the time dependence of

and

the mathematical set of values of

(numbers, vectors, tensors...). In

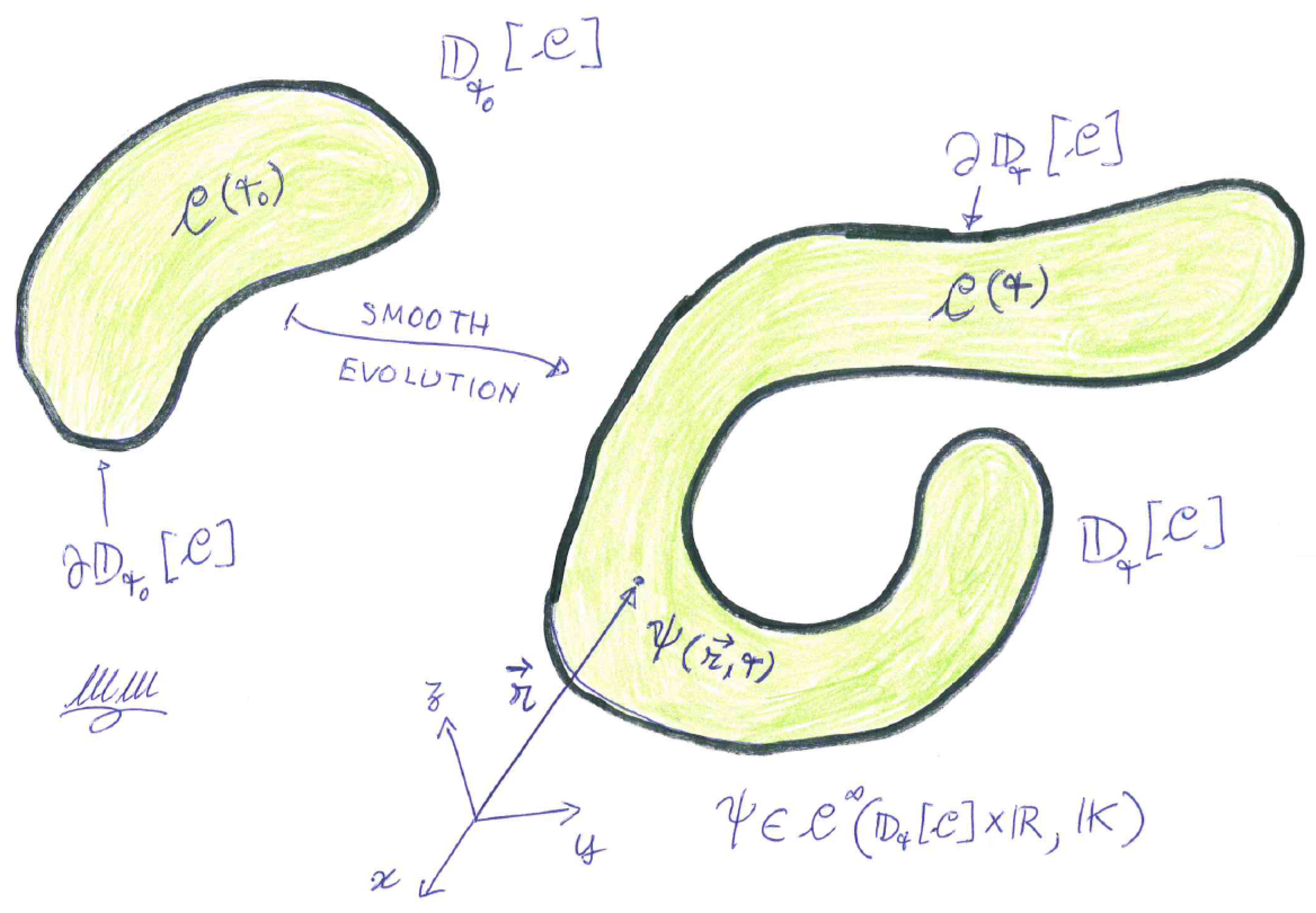

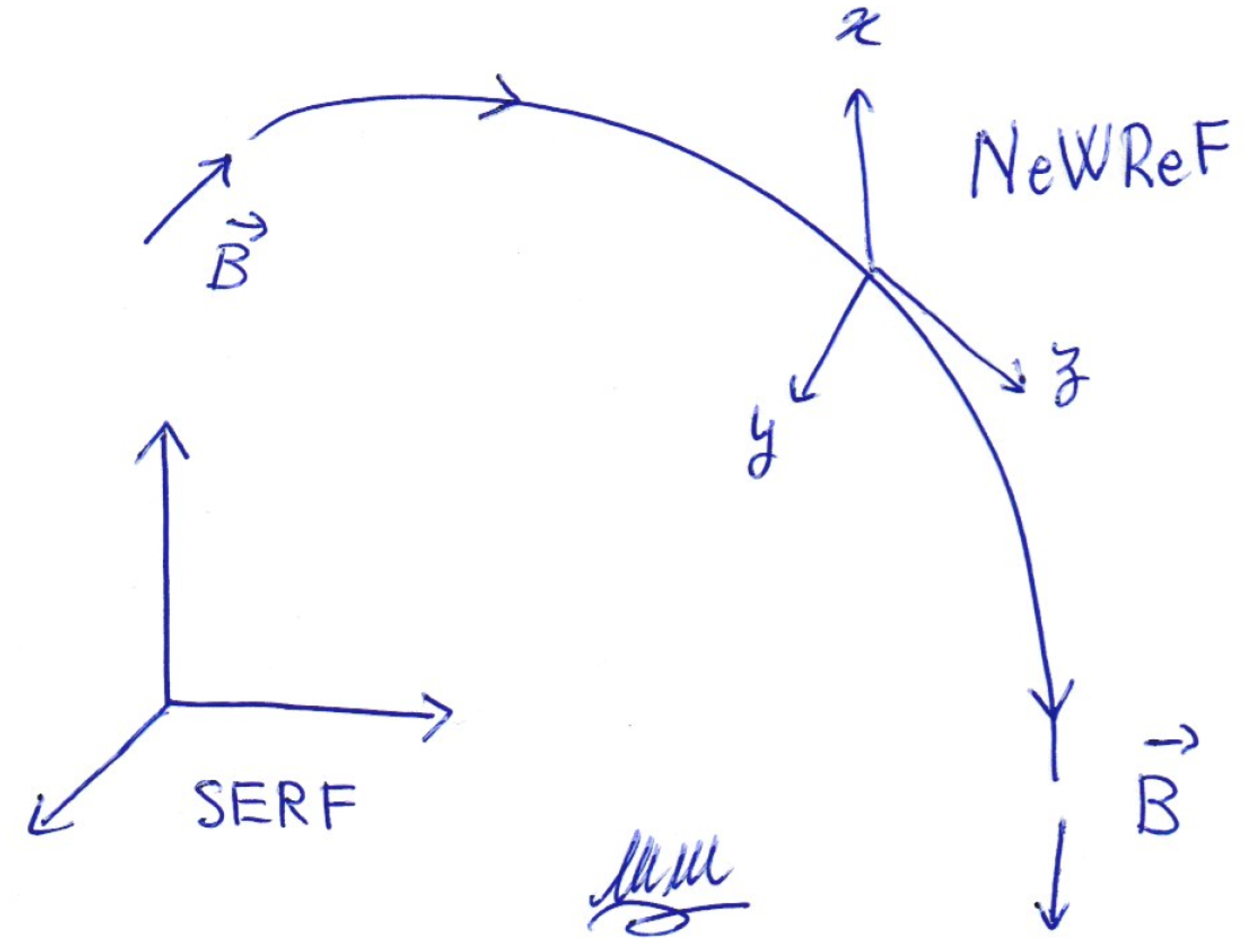

Figure 1 the assessment (

1) is cartoonised: a greenish continuum

evolves from an initial configuration

to a later one

through a supposed

smooth evolution; this means that any local quantity

describing it undergoes precisely the condition (

1). Actually, considering the border of the sets

the region where the local proxies of the continuum stop being defined, or may be understood to go from a finite value to zero “within no distance”, one should replace (

1) with something more precise like

(this does not, however, lighten the request (

1)).

Despite its high requests on the mathematical description of matter reality, this picture has been able to give very satisfactory theories, as hydrodynamics, magneto-hydrodynamics, elasticity theory and many more [

6]. Note that the picture satisfying (

1) is also a

deterministic picture, as the smooth time-behaviour of

excludes noise from its time evolution, which is another very strong requirement.

Even if the continuous picture of macroscopic systems is very beautiful, yet at a certain point the granular nature of matter was experimentally proved, and in order to reconcile the latter with the smooth picture of macroscopic bodies some reasoning had to be introduced, namely the so called continuous limit of pointlike particle systems. The fluid dynamics (FD) of the ionosphere is one important product of this “ideology”, that has an elegant and effective resoning, but relies on precise and not-that-universal properties of the microscopic systems at hand.

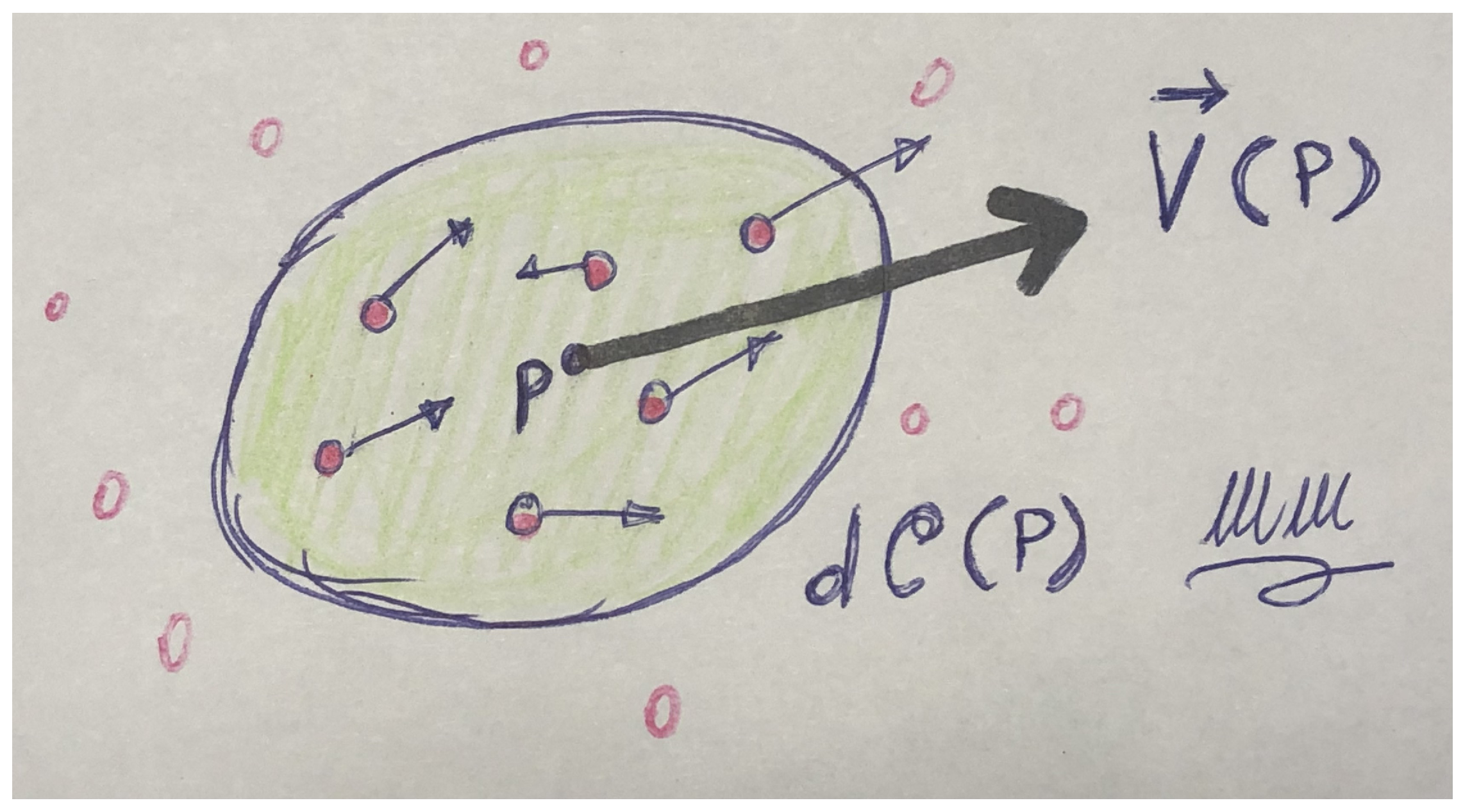

The central concept of the continuous limit contruction is considering “small” portions of the continuum

, referred to as

parcels, and make the following reasoning (the term “small” has to be specified later). In such a

there exist

elementary components of the macroscopic matter system, each of which is moving with a certain velocity. In general, these

components may or may not have all the same chemical nature, hence the same mass: the

local representation of the neighbourhood

within the continuum is obtained considering the

centre-of-mass P of those

components, to which the velocity of the centre-of-mass of the

particles is attributed as

. The local representation of the continuum at

P is constructed starting by saying that the parcel of continuum

moves with velocity

.

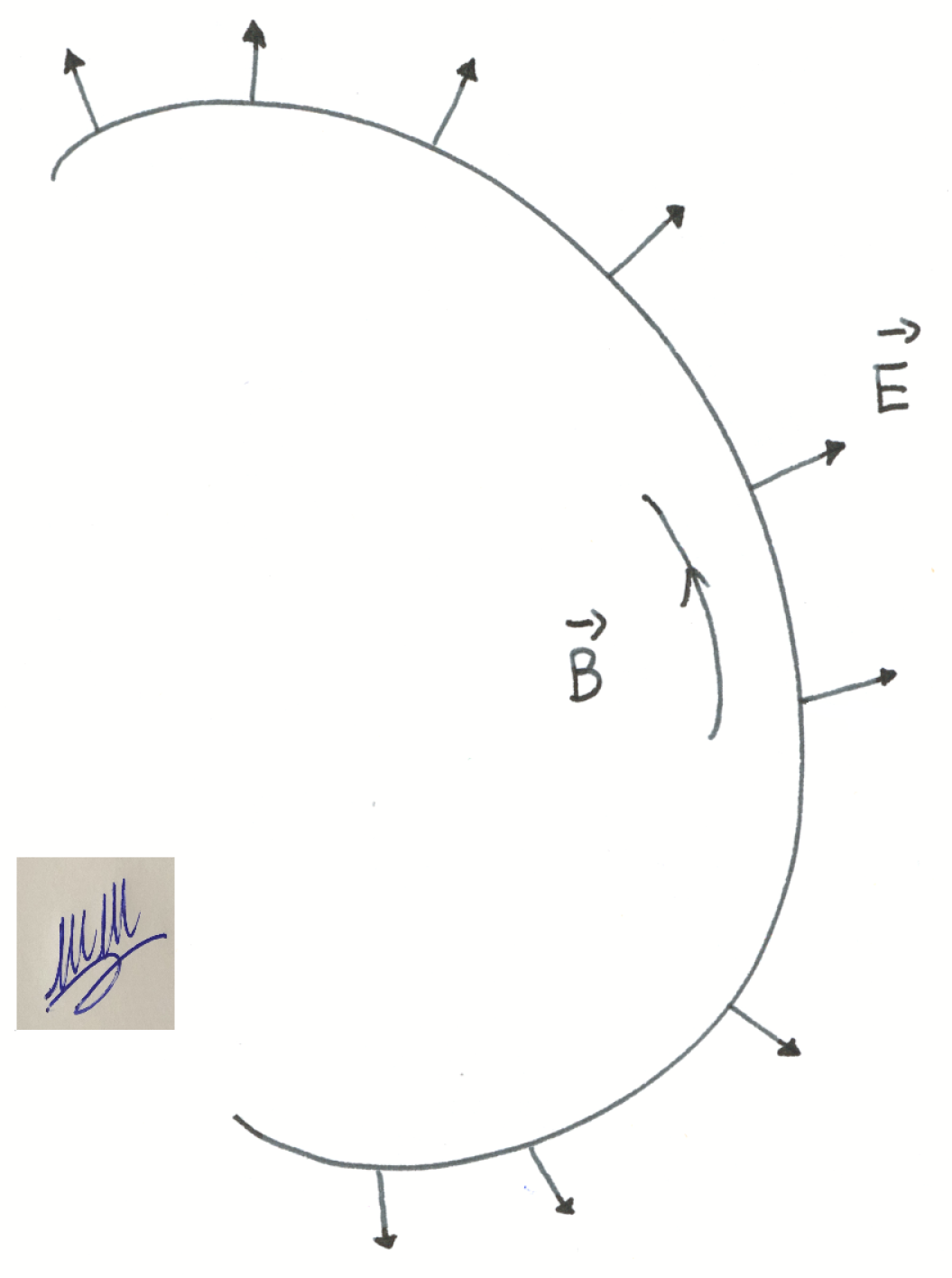

Figure 2 represents a cartoon of this idea. Recalling the definition of centre-of-mass, we may say that the point

P is attributed the

mass-average velocity of the

particles within

, i.e. the total linear momentum of the matter in

.

The bridge between the micro-physics of particles and macro-physics of continua was traced by Statistical Mechanics, in which the macroscopic appearance of the world is conceived a

s the statistical sum of all the microscopic, fluctuating contributions of particles. Boltzmann’s Kinetic Theory paved the way for a quantitative study of those cumulative effects of what the micro-components are doing: this makes it possible to recover the local variables

in (

1) as

suitable momenta of the statistical distributions of the

particles in

[

7]: this is how

mass density,

bulk velocity,

pressure,

tension ... are defined in FD. This sounds quite intuitive, as we humans simply accept that our senses, and our classical instruments, simply sense the world of elementary particles “defocussing” their tiny details, and saving only a coarse-grained, average picture of it. In this reasoning, when one looks at the

particles within the parcel

of centre-of-mass

P, the position

mentioned in the FD fields

is the position vector of

P: in what follows,

and

P are used with the same meaning.

All in all, the macroscopic picture

would be obtained via a “statistical” way:

being

some physical quantity depending on the single particle variables, and

a sign of suitable

statistical averaging(whatever this may mean at this early point) performed within

at time

t. In order to rely on a statistical procedure as (

2), one needs a first important ingredient to the very existence of the

s: the number

has to be so huge to point towards the

Thermodynamic limit

This is the first tough requirement to go from particle physics to FD, that had become a necessity once molecules, atoms and all their tinier fellows were discovered. In any statistical theory, due to results as the Central Limit Theorem [

8], there is the need of having enough samples to be able to neglect stochastic fluctuations, that is precisely what one needs to do in order for

to be a deterministic (hence, time-smooth) process. Note: the condition (

3), that may sound definitely sensible considering a small glass of water to contain

s of

molecules, is not at all obvious when one would like to represent the physics of galaxies (made of “few” solar systems) or even a finite portion of very dilute space plasmas (made of “few”

p and

) with FD, in which the constituents are all but

s of bodies. In those cases, the theory of small thermodynamic systems, large fluctuations and extreme events have to be invoked [

9].

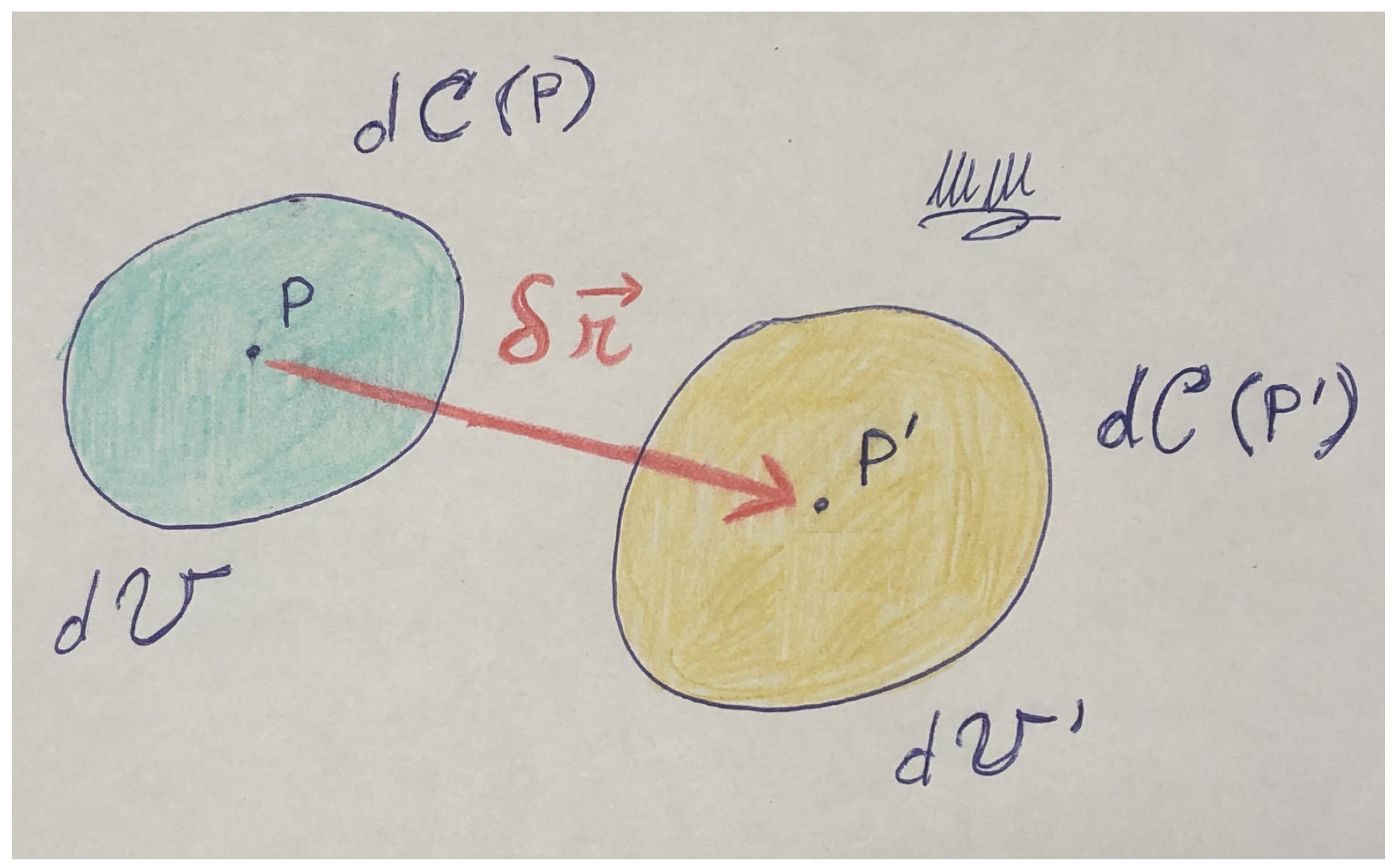

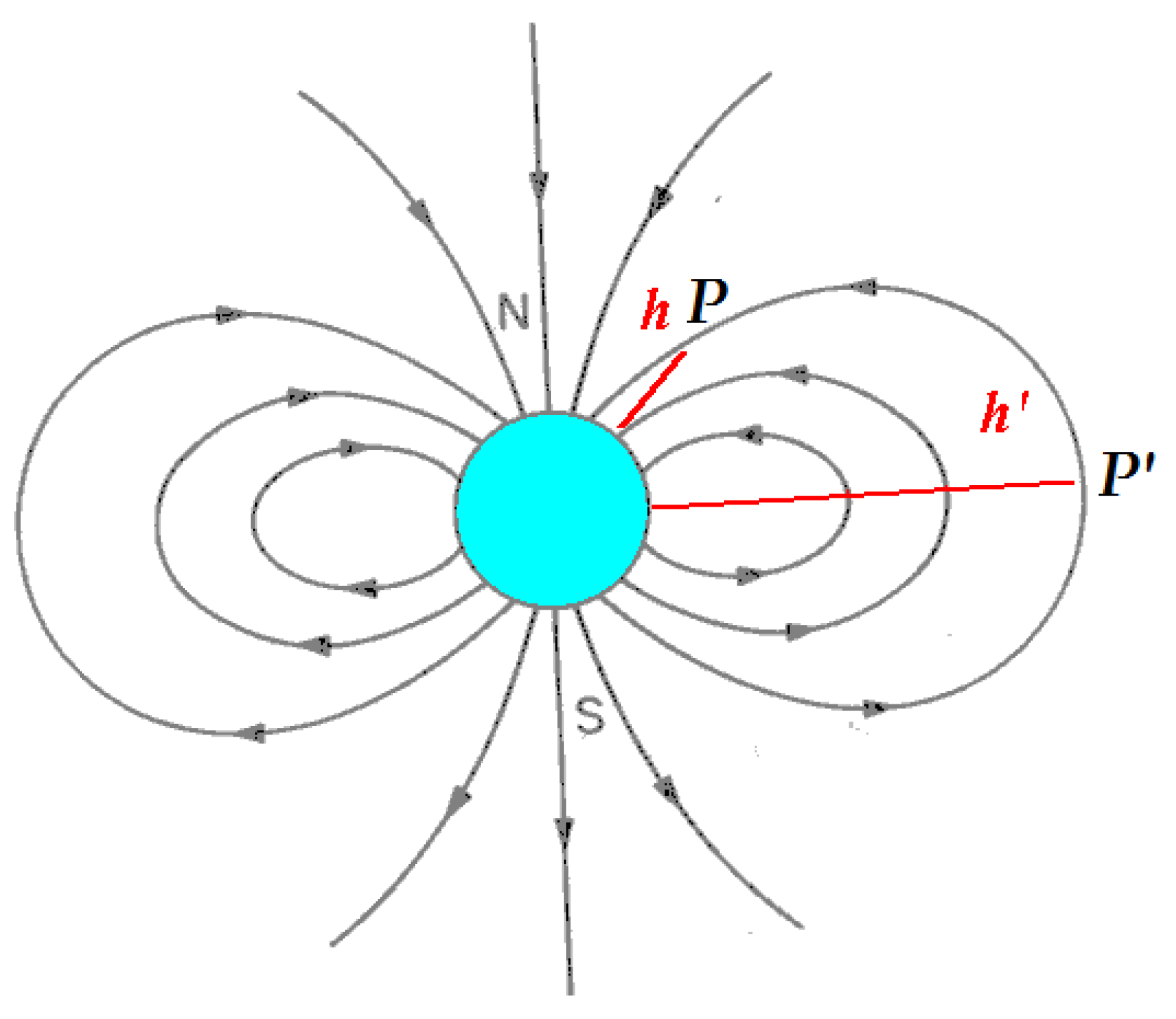

Once we have defined the continuum quantities

as non-fluctuating fields on

, one has to have them smooth, as prescribed by (

1). This means that, if one has two “nearby” points

P and

within

separated by some “small” displacement

, as in

Figure 3, one has to be able to calculate the non-fluctuating value

as

, the non-fluctuating value

, and then find the incremental limit between them with respect to the

distance to exist:

Equally, there must exist also the limit

defining the instantaneous rate of change with time of

. Actually, the two requirements (

4) and (

5) demand for differentiability of

in space and time, while the requirement (

1) is extremely stronger because it means

to have infinite space and time derivatives: clearly (

1) imply both (

4) and (

5). More cleanly, one could replace the two requirements (

4) and (

5) getting the whole (

1) by assessing

the differences between

at two (macroscopically) nearby points or at two nearby times must scale to zero as

positive integer powers of the distance or of the time lapse considered. Clearly, this (

6) rules out any turbulent regime of classical fluids [

10]. In (

4), (

5) and (

6) the symbol

refers to a length in the set of the valus of

, for instance the absolute value for real numbers, or Pitagora Theorem norm for three-dimensional vectors.

The construction of the continuum representation of a macroscopic system of matter is all pivoted on the definitions (

2) satisfying the conditions (

6), starting with the definition of a

velocity field as described before and sketched in

Figure 2, and a

mass density field , defined for the matter in

as the ratio

, being

the total mass of particles forming

, and

the parcel volume. Defining these

and

helps us explaining how “small” the “parcel” must be taken around

P: reference is made to the idea of

macroscopic infinitesimal portion [

11], for which one starts to ideally shrink the volume in

around

P and applies the definitions to smaller and smaller volumes

; at a certain size of

one stops seeing

and

fluctuating, while go on with shrinking too much, fluctuations re-appear. At the beginnig of this “plateau” of the

values with decreasing

one stops including in the parcel regions of the continuum in different local conditions; when fluctuations re-appear at too small values of

, the number

is not satisfying the condition (

3) any more, and the granularity of matter is unwantedly appreciated in terms of fluctuations.

Concluding this rapid introduction to continua, that is the necessary foreword to FD, we refer again to

Figure 2: the set of particles in

have their

degrees of freedom, three of which have been taken into account considering the position of

P and the velocity

: these are the centre-of-mass variables [

12]. What about the other

degrees of freedom, namely the variables relative-to-

P, e.g. the difference between the position of each of the

particles of

and that of

P, and their canonically conjugated momenta?

Treating also this huge number of relative variables is necessary to completely describe che phase space of the

particles in the parcel, but despite it is sensible to use the

per se deterministic variables

for the centre-of-mass

P of the parcel, being

the total momentum of

, the

relative variables of the parcel will be treated

in a statistical way. That is: while

is already a field

as those involved in equations (

1) and (

2), the positions

of the

particles in the parcel relative to

P and their conjugate momenta become the subject of the

-

local statistical mechanics. As the dynamics in this relative phase space

is treated statistically, becasue

, the statistical distributions on

become the completion of the description of the exactly

particles in

.

On a theoretical ground, describing statistically the relative variables within the parcel vmay consist of the dynamics of the Gibbs distribution in

[

7,

13]; in practice, one always assumes the particles in

to be represented by some kinetic theory that will cut the BBGKY hierarchy in

to 1-particle distributions. Moreover, as the only well established statistical mechanics is equilibrium thermodynamics, the

-local kinetic theory will converge to the definition of

local thermodynamic variables attributed to the point

of position vector

, as new smooth fields

. All in all, the

microscopic degrees of freedom of the particles in the parcel will turn into the 3 ones of the centre-of-mass plus an equilibrium thermodynamics for the

relative coordinates, representing the inner structure of

, converging however to some other local smooth continuum system variables

(e.g., the pressure, or density, and temperature, see Sub

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5).

With this, the FD philosophy of the LIM is established; before moving on focussing on the system composition, let us resume it in items:

The requirement 1 makes it possible to have well defined non-fluctuating statistics tout court; the requirement 2 leads to the feasibility of deterministic smooth FD at all. Last but not least, the requirement 3 is the path leading to FD as we know it today. The thorny debate about physical regimes when those requirements do not appear to be met deserves future manuscripts.

2.2. The System: Matter and Interactions

Let us now introduce how all this theoretical background is applied to the Earth’s ionosphere.

The system is considered to be formed by

S chemical species, indicated as

, with

. For example, molecular species as O

2, N

2, CO

2, NH

4, but also atomic species as O and N, are in this list. If the neutral species considered are

and the ion species are

then the example composition reads:

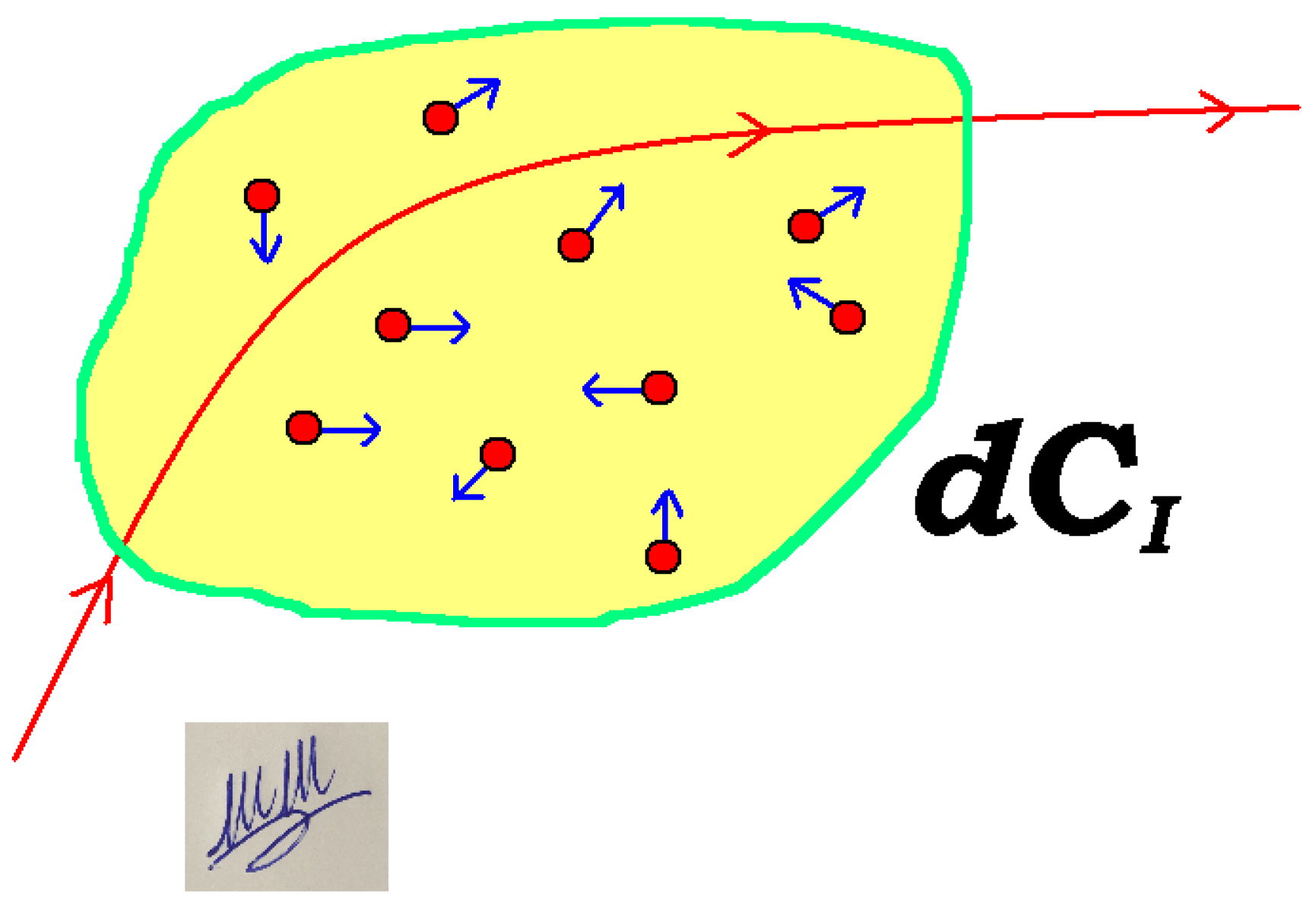

In the ionosphere, these

S chemicals are in the state of

gases. Each of the different gases is an extended system of matter represented as a continuum

in the way discussed before, i.e. with parcel dynamics: at each point

P of the space a parcel

is considered for the

I-th chemical, with a centre-of-mass velocity

and the

I-th relative phase space

described via statistical mechanics, in general, more practically via

P-local equilibrium thermodynamics.

This is only the matter part; there is a field part too, made of those fundamental force fields acting on the atmospheric gases: gravity and electromagnetic fields. Due to the average speeds of the subsystems in the SERF, and to the energy of the processes treated, here we represent everything in terms of classical physics, involving only small sips of Special Relativity, here and there, when the electromagnetic fields are to be transformed from a first observer to another one. Gravity will not be a dynamical variable of the system!

Every component

experiences the action of the gravitational field defined around the Earth, which includes the field of properly massive origin, the inertial positional forces and the time varying field due to the tidal action of other celestial bodies. From a General relativistic point of view one should include Coriolis force too in the gravitational field, while here the Coriolis force will be kept as separated from the whole “effective” gravity. In general one can write:

Coriolis forces are thus due to Coriolis acceleration field

being

the rotation vector of the Earth as seen in a frame in which this Coriolis force is not experienced, and

the fluid velocity of the

I-th species, constructed as explained before.

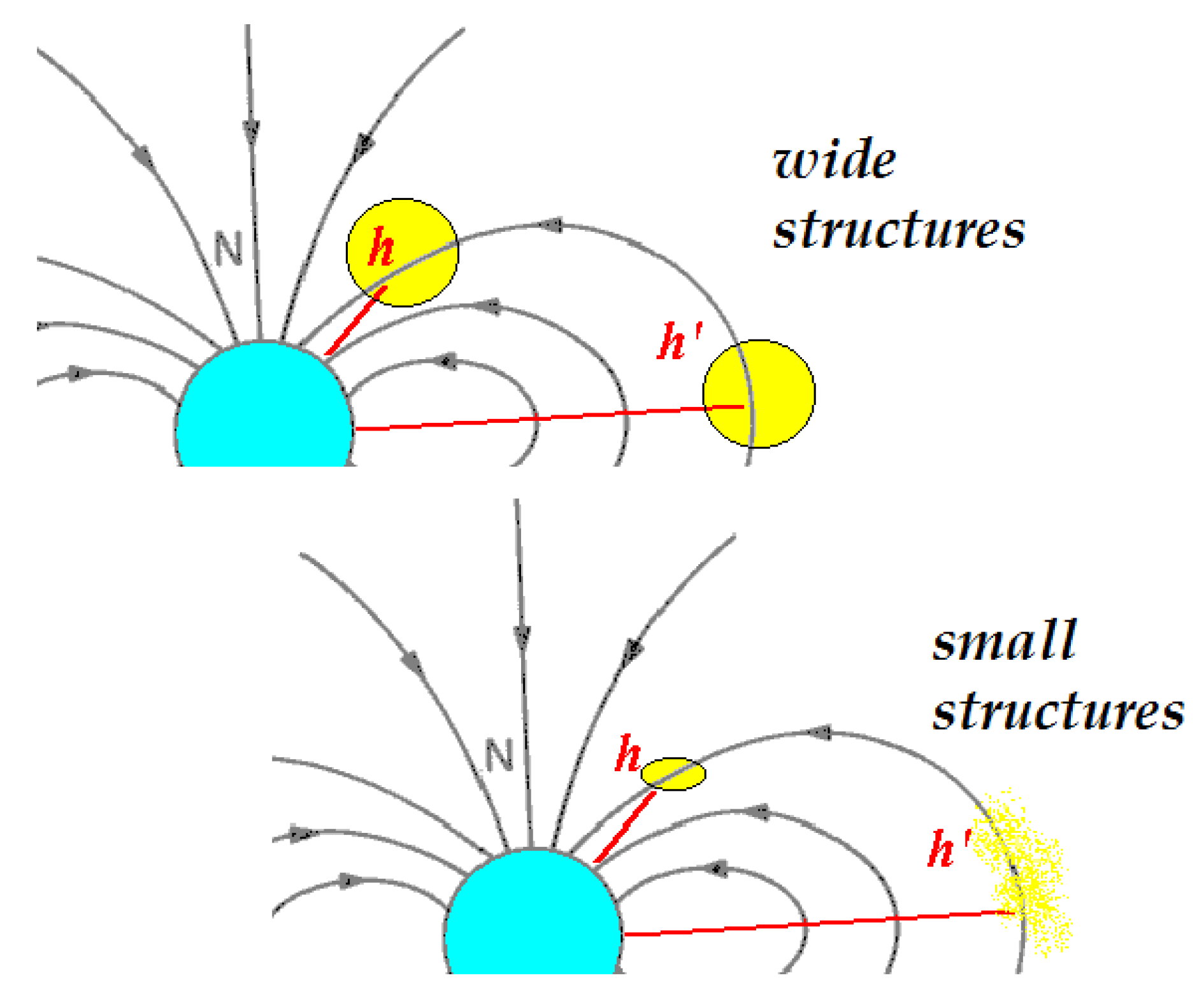

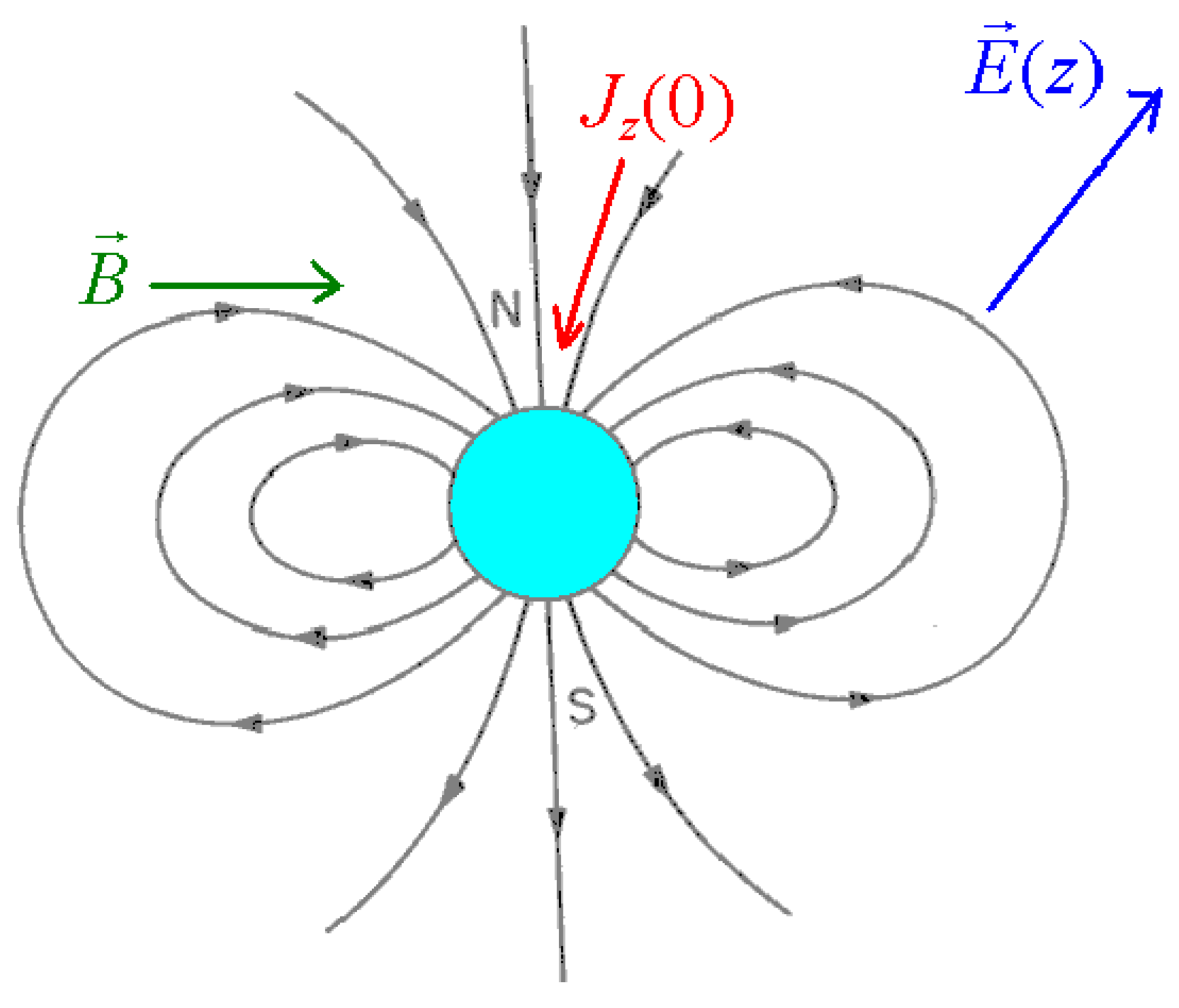

Electromagnetic fields are experienced only by charged continua (in the example (

7) the ions

and

and the electrons

), and for these particles their strength is much more important than that of gravity. In general there is the geomagnetic field

, that is considered as a rigid external field, and some non geomagnetic, perturbing magnetic field

, due to temporary phenomena (e.g., the geomagnetic storms), so that one has

Many electric fields of different origin are also present, and this will be clarified later.

Quite the opposite to what happens to gravity, the electromagnetic fields acting on the

s undergo important back reactions due to charge displacements, net currents and dynamoes produced by the motion of these fluids. The “complete” dynamical system we will deal with will then include all these fluids

plus the fields

and

influenced by the atmospheric motions (it should be stated that the mechanics of the

s are only a part of the source of the atmospheric

and

, since

is generated, in its component

in equation (

9), by some conducting lavic movement inside the solid Earth [

14]).

2.3. Fluid Matter Variables

Every single chemical component

is described as made of particles of mass

and electrical charge

, we will use

to indicate mass density,

for numerical density and

for charge density. These quantities are related as:

Of course,

,

and

are proper fluid fields as the

discussed in Sub

Section 2.1.

The components involved can be neutral species

or charged ones

In ionospheric studies the use of

is often preferred instead of

, because the numerical densities of particles enter the typical expressions of cross sections, determining the production and loss rates of the

s in chemical processes, and also because the expressions of many measurable quantities are entered by the numerical density

of free electrons. For what concerns

one must say that the functional relationship (

10) renders it practically equivalent to

or

for the charged species, while when

it simply vanishes.

About these

s, in general a constraint of

neutrality of the LIM

may exist, besides the global one:

The constraint (

13) is a standard in many applications of ionospheric physics, even if particular regions, as the dawn and dusk terminator, may violate it.

Local thermal equilibrium is assumed for each

: then, temperature fields

will come into the play; it is useful to remember that the different chemicals have different temperatures,

they are not in thermal equilibrium with the others; for example, electron temperature has been measured as about

, while positive ions were found around

in the polar E layer at about 150 km height, when intense electric field are present, as reported in [

15]. This should not be surprising, despite the different

s are in thermal contact with each other: as they are moving, floating and interacting, these gases are in a well different condition from that of fluids in a calorimeter. This also keeps the system far from a global thermodynamic equilibrium.

The continuous approach, which is largely valid for studying plasma and neutrals of the “standard” ionosphere, can not be used to describe the rain of high energy particles entering the Earth’s atmosphere from the space, because of the hypothesis of local thermal equilibrium which is lacking for them.

2.4. Dynamical Variables for Matter

A fluid occupying a certain volume in the space is fully described when point by point and time by time its velocity field, mass density and tensions are given [

16]; this means that for each constituent

one should use the

-vector

(bulk velocity given by the centre-of-mass velocity of the parcel with the centre-of-mass in

), the

-scalar

(bulk mass density) and the distinct elements of the stress tensor

with

, a two rank

-tensor. Usual fluids as those at hand have symmetric stress tensor, so that one has 6 independent components

. This

, plus

, plus

give all the fields to describe each continuum

composing the atmosphere in the Eulerian picture. However, tensions are not further variables to be added to

and

: the

s are in general functionally dependent on the velocity field

, and “fluids” are classified into different species according to the mathematical form of the dependence

The tension dependence on velocities is restricted in general to a particular subdivision of

, that can be written as the sum of a pure positional addendum and on another term depending on the

s too:

The continuum

is defined as

fluid if

holds. In the very particular case in which

one speaks about

ideal fluids. The definition (

20) means that the system is not able to exert any off diagonal stress when it is at rest. The statement (

21) indicates as ideal fluids those fluids unable to exert off diagonal stresses also when they are moving.

The

-scalar

in (

19) is the

hydrostatic pressure. The case of perfect fluids well represents the

s in very dilute regions [

17]. Note that since

is a scalar under the rotation group it must be related to the trace of

, so that

is traceless.

In order to describe energy exchanges the thermodynamical nature of the system must be taken into account; then another quantity is introduced, the local temperature

, which is also an

-scalar. The full set of dynamical variables we have introduced to describe each

is then given by the density

, the velocity

, the pressure

, the

tensor and the temperature

, giving a set of

12 unknowns in the equations of motion. In Sub

Section 3.4 the roles of

and

will be clarified from a fully mechanical point of view, as coarse grained proxies of the microscopic degrees of freedom of the matter of the fluid at hand, contained in the volume

, in terms of variables relative-to-the-centre-of-mass of the “parcel”.

The various fluids

are generally classified and studied as follows [

18]:

-

Neutral particles. Various molecules or atoms (e.g. O, N, O2, N2, CO2, NH4 and so on) with zero electric charge: these ones are the major part, both numerically as well as massively, of all the high atmosphere, up to the level of about 1000 km height, starting point of a region where practically all the matter is ionized. From that point on, one speaks about plasmasphere.

If each neutral species is indicated with the index

, the speed of their centre of mass is point by point some field

, defined as follows in terms of partial matter densities

and velocities

:

This velocity undergoes a proper dynamics that may be attributed to the neutral matter as a unique fuid .

Negative ions. These are the species which have captured one or more electrons. These particles are very rare and their presence is practically negligible in general. Nevertheless, one should consider them when dealing with the lower part of the ionosphere, as the region D and the lower E [

19]. Negative ion abundance is reasonably non negligible only under 95 km, even if in particular conditions this can be false. Sometimes a coefficient

is defined for each negative ion

as

giving the measure of the contribution of the species

to the ionospheric negative charge, relative to the electron one.

Positive ions. These are the neutrals that have lost one or more electrons: actually, the 2- or 3-valent positive ions are very rare, so we can restrict to the study of 1-valent positive ions. When the constraint (

13) holds and no negative ions exist, positive ions have a numerical density equal to that of free electrons.

Electrons. Electrons are the most important element for ionospheric phenomenology as far as electromagnetic disturbances are concerned, because of their very small mass that gives them a great mobility [

3], making them very effective in producing local and travelling electromagnetic fields.

In general one could represent in a Lagrangian way the fluid motion as the evolution of a manifold, a domain continuously filled in with matter, and describe its motion as the transformations undergone by this manifold. The manifold can stretch, roll, it can be deformed by tensions, its centre-of-mass moves under the action of external forces. Basically one physical portion of it can be identified as the evolution of a fixed portion of the initial continuum [

16]. This way of representing the evolution of a continuous system has led to a Hamiltonian description of fluids alternative to the local approach (for reference see [

20,

21,

22] and [

23]).

In the absence of chemical reactions the mass of the parcel

remains constant:

being

the operator making the time derivative along the motion [

24] . What happens if chemical reactions take place?

When chemical reactions enter the fluid dynamics, it is convenient to treat the systems as non constant mass systems, writing:

This

is the variation rate of the mass of the parcel as following the parcel motion, and it can be either positive or negative, according to production or loss processes.

The description of the fluid

is referred to as

Lagrangian or substantial, because the quantities used refer to the degrees of freedom of a material portion of the system

; on the contrary, fluids are often described in the

Eulerian or local way, in which one describes the situation via quantities thought of as properties of the spatial point at hand [

16]. When some quantity

is attributed to a fluid, the relationship between the Lagrangian version

and the Eulerian version

of it is given in terms of time derivatives, and reads

being

the local speed of the fluid to which

is attributed (for ionospheric continua, the

s and

in (

26) have a chemical species index

I)

It has already been stated that the extended system

has

centre-of-mass (CoM)

variables and

relative-to-CoM (R2CoM)

variables as explained in [

12] and references therein. The evolution of the CoM variables will be governed by Newton’s principle as explained in Sub

Section 3.3 below. For what concerns the R2CoM variables,

a statistical approach is used for them in ordinary fluid dynamics, see better Sub

Section 3.4.