Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

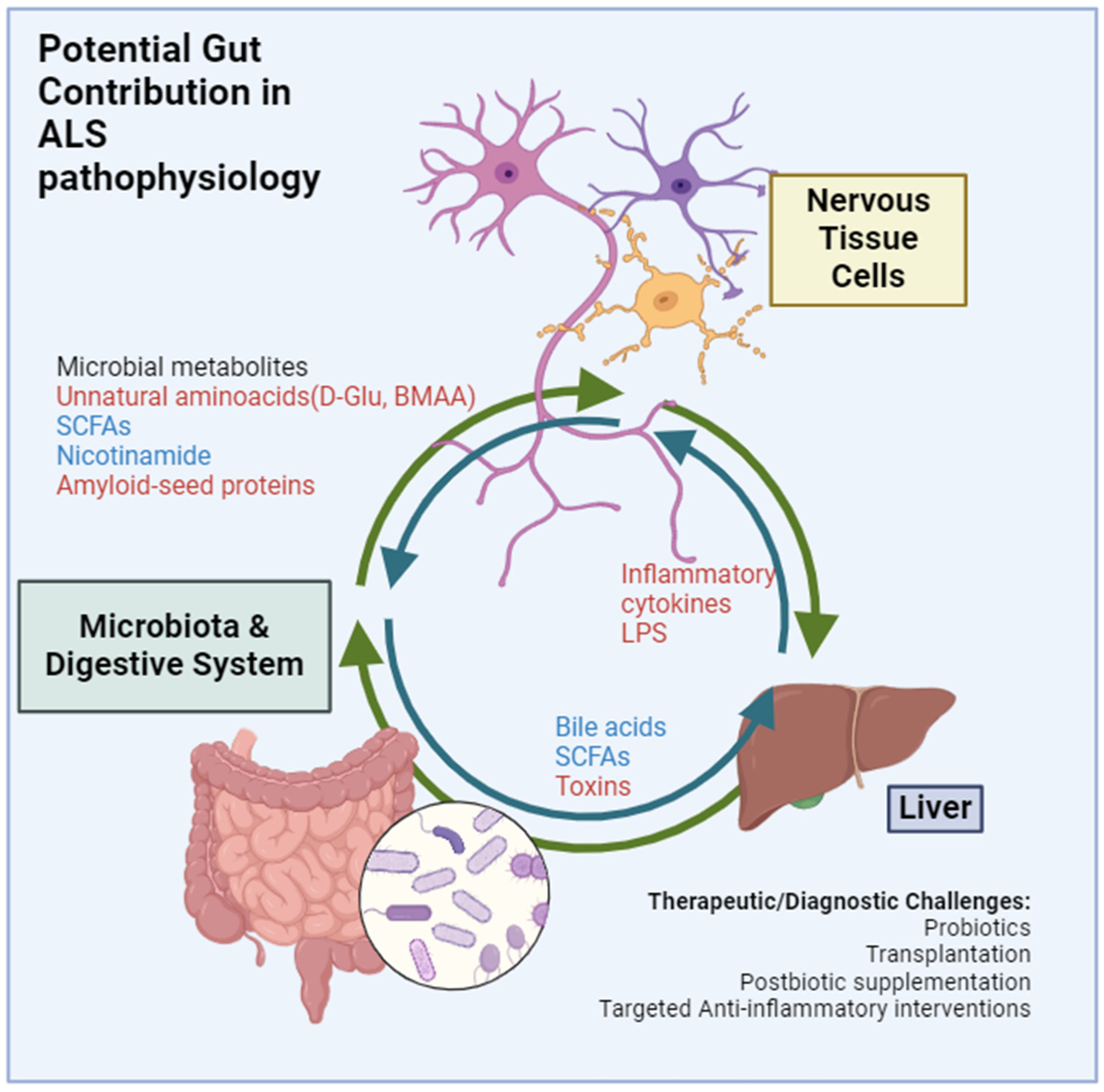

2. Gut Microbiota and ALS: Current Understanding

The Gut Microbiota’s Influence on Liver Health

3. Key Microbial Metabolites and Factors and Their Influence on ALS

SCFAs, LPS and Other Lipids

Microbiota Influence on Protein Aggregation in ALS: Potential Parallels in Bacterial Systems

β-Methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA) and Other Amines as Postbiotic Neurotoxic Factors

Microbiota Differences in Spinal vs. Bulbar ALS

Impact of Dysphagia on Oral and Gut Microbiota

The Role of Antibiotics and Dietary Changes in ALS Progression

5. Therapeutic Potential of Microbiota Modulation

Probiotics and Prebiotics

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

Dietary Interventions

Targeting Specific Bacterial Metabolites

6. Current Gaps and Future Directions

6.1. Need for Larger and Longitudinal Studies

6.2. Heterogeneity in ALS Phenotypes and Microbiota Response

6.3. Mechanistic Understanding of Microbiota's Role in ALS

6.4. Therapeutic Trials of Microbiota-Based Interventions

6.5. Role of Environmental and Dietary Factors in Modulating Microbiota

6.6. Developing Personalized Microbiota-Based Therapies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mejzini, R.; Flynn, L.L.; Pitout, I.L.; Fletcher, S.; Wilton, S.D.; Akkari, P.A. ALS genetics, mechanisms, and therapeutics: where are we now? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1310. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Kankel, M.W.; Su, S.C.; Han, S.W.S.; Ofengeim, D. Exploring the genetics and non-cell autonomous mechanisms underlying ALS/FTLD. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 648–662. [CrossRef]

- Gros-Louis, F.; Gaspar, C.; Rouleau, G.A. Genetics of familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 956–972. [CrossRef]

- Al-Chalabi, A.; Lewis, C.M. Modelling the effects of penetrance and family size on rates of sporadic and familial disease. Hum. Hered. 2011, 71, 281–288. [CrossRef]

- Povedano, M.; Saez, M.; Martínez-Matos, J.-A.; Barceló, M.A. Spatial Assessment of the Association between Long-Term Exposure to Environmental Factors and the Occurrence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Catalonia, Spain: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study. Neuroepidemiology 2018, 51, 33–49. [CrossRef]

- Proaño, B.; Cuerda-Ballester, M.; Daroqui-Pajares, N.; Del Moral-López, N.; Seguí-Sala, F.; Martí-Serer, L.; Calisaya Zambrana, C.K.; Benlloch, M.; de la Rubia Ortí, J.E. Clinical and sociodemographic factors related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in spain: A pilot study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Fabi, J.P. The connection between gut microbiota and its metabolites with neurodegenerative diseases in humans. Metab. Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 967–984. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Microbiome and micronutrient in ALS: From novel mechanisms to new treatments. Neurotherapeutics 2024, e00441. [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.-S.; Autenrieth, I.B. The gut microflora and its variety of roles in health and disease. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013, 358, 273–289. [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Powell, N.; Walker, M.M.; Talley, N.J. The mucosal immune system: master regulator of bidirectional gut-brain communications. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 143–159. [CrossRef]

- Fung, T.C. The microbiota-immune axis as a central mediator of gut-brain communication. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 136, 104714. [CrossRef]

- Fontdevila, L.; Povedano, M.; Domínguez, R.; Boada, J.; Serrano, J.C.; Pamplona, R.; Ayala, V.; Portero-Otín, M. Examining the complex Interplay between gut microbiota abundance and short-chain fatty acid production in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients shortly after onset of disease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23497. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Galaction, A.I.; Turnea, M.; Blendea, C.D.; Rotariu, M.; Poștaru, M. Redox homeostasis, gut microbiota, and epigenetics in neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, Z.; Lan, X.; Yu, S.; Yang, Y. Fecal microbiota transplantation significantly improved respiratory failure of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2353396. [CrossRef]

- Pribac, M.; Motataianu, A.; Andone, S.; Mardale, E.; Nemeth, S. Bridging the gap: harnessing plant bioactive molecules to target gut microbiome dysfunctions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 4471–4488. [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Lai, X.; Li, C.; Ding, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Y. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Various Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders-An Evidence Mapping Based on Quantified Evidence. Mediators Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 5127157. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Su, L.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C. Gut microbiota regulation and their implication in the development of neurodegenerative disease. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Niccolai, E.; Di Pilato, V.; Nannini, G.; Baldi, S.; Russo, E.; Zucchi, E.; Martinelli, I.; Menicatti, M.; Bartolucci, G.; Mandrioli, J.; Amedei, A. The Gut Microbiota-Immunity Axis in ALS: A Role in Deciphering Disease Heterogeneity? Biomedicines 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- McCombe, P.A.; Henderson, R.D.; Lee, A.; Lee, J.D.; Woodruff, T.M.; Restuadi, R.; McRae, A.; Wray, N.R.; Ngo, S.; Steyn, F.J. Gut microbiota in ALS: possible role in pathogenesis? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 785–805. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Man, S.; Sun, B.; Ma, L.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Gao, W. Gut liver brain axis in diseases: the implications for therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 443. [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, M.; Kaminska, M.; Oluwasegun, A.K.; Mosig, A.S.; Wilmes, P. Emulating the gut-liver axis: Dissecting the microbiome’s effect on drug metabolism using multiorgan-on-chip models. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research 2021, 18, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pang, C.; Xie, J.; Gao, L.; Du, L.; Cao, W.; Fan, D.; Cui, C.; Yu, H.; Deng, B. Fighting amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by protecting the liver? A prospective cohort study. Ann. Neurol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, A.; Sayin, S.I.; Marschall, H.-U.; Bäckhed, F. Intestinal Crosstalk between Bile Acids and Microbiota and Its Impact on Host Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 41–50. [CrossRef]

- Niesler, B.; Kuerten, S.; Demir, I.E.; Schäfer, K.-H. Disorders of the enteric nervous system - a holistic view. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 393–410. [CrossRef]

- Kurlawala, Z.; McMillan, J.D.; Singhal, R.A.; Morehouse, J.; Burke, D.A.; Sears, S.M.; Duregon, E.; Beverly, L.J.; Siskind, L.J.; Friedland, R.P. Mutant and curli-producing E. coli enhance the disease phenotype in a hSOD1-G93A mouse model of ALS. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5945. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Niu, K.; Zeng, W.; Wang, R.; Guo, X.; Lin, C.; Hu, L. Oleanolic acid alleviate intestinal inflammation by inhibiting Takeda G-coupled protein receptor (TGR) 5 mediated cell apoptosis. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 1963–1976. [CrossRef]

- Kasubuchi, M.; Hasegawa, S.; Hiramatsu, T.; Ichimura, A.; Kimura, I. Dietary gut microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, and host metabolic regulation. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2839–2849. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Qin, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Zou, Z.; Wang, L. Dietary butyrate suppresses inflammation through modulating gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366. [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Cardiovascular disease may be triggered by gut microbiota, microbial metabolites, gut wall reactions, and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Gorain, B. Mechanistic insight of neurodegeneration due to micro/nano-plastic-induced gut dysbiosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Mustafa, A.N.; Mustafa, M.A.; S, R.J.; Dabis, H.K.; Prasad, G.V.S.; Mohammad, I.J.; Adnan, A.; Idan, A.H. The role of gut-derived short-chain fatty acids in Parkinson’s disease. Neurogenetics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Khachatryan, L.G.; Younis, N.K.; Mustafa, M.A.; Ahmad, N.; Athab, Z.H.; Polyanskaya, A.V.; Kasanave, E.V.; Mirzaei, R.; Karampoor, S. Microbiota-derived short chain fatty acids in pediatric health and diseases: from gut development to neuroprotection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1456793. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, X.; Lao, L.; Wang, Y.; Su, H.; Sun, H. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Historical Overview and Future Directions. Aging Dis. 2024, 15, 74–95. [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T.; Takahashi, M.; Fukuda, N.N.; Murakami, S.; Miyauchi, E.; Hino, S.; Atarashi, K.; Onawa, S.; Fujimura, Y.; Lockett, T.; Clarke, J.M.; Topping, D.L.; Tomita, M.; Hori, S.; Ohara, O.; Morita, T.; Koseki, H.; Kikuchi, J.; Honda, K.; Hase, K.; Ohno, H. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [CrossRef]

- Föh, B.; Buhre, J.S.; Lunding, H.B.; Moreno-Fernandez, M.E.; König, P.; Sina, C.; Divanovic, S.; Ehlers, M. Microbial metabolite butyrate promotes induction of IL-10+IgM+ plasma cells. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266071. [CrossRef]

- Church, J.S.; Bannish, J.A.M.; Adrian, L.A.; Rojas Martinez, K.; Henshaw, A.; Schwartzer, J.J. Serum short chain fatty acids mediate hippocampal BDNF and correlate with decreasing neuroinflammation following high pectin fiber diet in mice. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1134080. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, J.; Noakes, P.G.; Bellingham, M.C. The role of altered bdnf/trkb signaling in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 368. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Vello, P.; Tytgat, H.L.P.; Elzinga, J.; Van Hul, M.; Plovier, H.; Tiemblo-Martin, M.; Cani, P.D.; Nicolardi, S.; Fragai, M.; De Castro, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Silipo, A.; Molinaro, A.; de Vos, W.M. The lipooligosaccharide of the gut symbiont Akkermansia muciniphila exhibits a remarkable structure and TLR signaling capacity. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8411. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Qiao, Y. Messengers From the Gut: Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites on Host Regulation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 863407. [CrossRef]

- Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Shrestha, A.; Duff, A.F.; Kontic, D.; Brewster, P.C.; Kasperek, M.C.; Lin, C.-H.; Wainwright, D.A.; Hernandez-Saavedra, D.; Woods, J.A.; Bailey, M.T.; Buford, T.W.; Allen, J.M. Aging amplifies a gut microbiota immunogenic signature linked to heightened inflammation. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14190. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.M.; Ke, X.; Hitchcock, D.; Jeanfavre, S.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Nakata, T.; Arthur, T.D.; Fornelos, N.; Heim, C.; Franzosa, E.A.; Watson, N.; Huttenhower, C.; Haiser, H.J.; Dillow, G.; Graham, D.B.; Finlay, B.B.; Kostic, A.D.; Porter, J.A.; Vlamakis, H.; Clish, C.B.; Xavier, R.J. Bacteroides-Derived Sphingolipids Are Critical for Maintaining Intestinal Homeostasis and Symbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 668-680.e7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.-S. Sphingolipids in neuroinflammation: a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. BMB Rep. 2020, 53, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Siopi, E.; Guenin-Macé, L.; Pascal, M.; Laval, T.; Rifflet, A.; Boneca, I.G.; Demangel, C.; Colsch, B.; Pruvost, A.; Chu-Van, E.; Messager, A.; Leulier, F.; Lepousez, G.; Eberl, G.; Lledo, P.-M. Effect of gut microbiota on depressive-like behaviors in mice is mediated by the endocannabinoid system. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6363. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, I.; Allaband, C.; Mannochio-Russo, H.; El Abiead, Y.; Hagey, L.R.; Knight, R.; Dorrestein, P.C. The changing metabolic landscape of bile acids - keys to metabolism and immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 21, 493–516. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.R.; King, O.D.; Shorter, J.; Gitler, A.D. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 361–372. [CrossRef]

- Hayden, E.; Cone, A.; Ju, S. Supersaturated proteins in ALS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017, 114, 5065–5066. [CrossRef]

- Gitler, A.D.; Shorter, J. RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in ALS and FTLD-U. Prion 2011, 5, 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Smethurst, P.; Sidle, K.C.L.; Hardy, J. Review: Prion-like mechanisms of transactive response DNA binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2015, 41, 578–597. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, T.R.; Challis, C.; Jain, N.; Moiseyenko, A.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Shastri, G.G.; Thron, T.; Needham, B.D.; Horvath, I.; Debelius, J.W.; Janssen, S.; Knight, R.; Wittung-Stafshede, P.; Gradinaru, V.; Chapman, M.; Mazmanian, S.K. A gut bacterial amyloid promotes α-synuclein aggregation and motor impairment in mice. eLife 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Van Assche, E.; Van Puyvelde, S.; Vanderleyden, J.; Steenackers, H.P. RNA-binding proteins involved in post-transcriptional regulation in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 141. [CrossRef]

- McQuail, J.; Switzer, A.; Burchell, L.; Wigneshweraraj, S. The RNA-binding protein Hfq assembles into foci-like structures in nitrogen starved Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12355–12367. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, G.R.; Comolli, L.R.; Gaietta, G.M.; Fero, M.; Hong, S.-H.; Jones, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Downing, K.H.; Ellisman, M.H.; McAdams, H.H.; Shapiro, L. Caulobacter PopZ forms a polar subdomain dictating sequential changes in pole composition and function. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 173–189. [CrossRef]

- Shattuck, J.E.; Paul, K.R.; Cascarina, S.M.; Ross, E.D. The prion-like protein kinase Sky1 is required for efficient stress granule disassembly. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3614. [CrossRef]

- Guzikowski, A.R.; Chen, Y.S.; Zid, B.M. Stress-induced mRNP granules: Form and function of processing bodies and stress granules. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2019, 10, e1524. [CrossRef]

- Calloni, G.; Chen, T.; Schermann, S.M.; Chang, H.-C.; Genevaux, P.; Agostini, F.; Tartaglia, G.G.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. DnaK functions as a central hub in the E. coli chaperone network. Cell Rep. 2012, 1, 251–264. [CrossRef]

- Zajkowski, T.; Lee, M.D.; Mondal, S.S.; Carbajal, A.; Dec, R.; Brennock, P.D.; Piast, R.W.; Snyder, J.E.; Bense, N.B.; Dzwolak, W.; Jarosz, D.F.; Rothschild, L.J. The Hunt for Ancient Prions: Archaeal Prion-Like Domains Form Amyloid-Based Epigenetic Elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2088–2103. [CrossRef]

- King, A.E.; Woodhouse, A.; Kirkcaldie, M.T.K.; Vickers, J.C. Excitotoxicity in ALS: Overstimulation, or overreaction? Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275 Pt 1, 162–171. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, M.; Park, K.; Hong, S. A systematic review on analytical methods of the neurotoxin β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA), and its causative microalgae and distribution in the environment. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143487. [CrossRef]

- Banack, S.A.; Cox, P.A. Creating a simian model of guam ALS/PDC which reflects chamorro lifetime BMAA exposures. Neurotox. Res. 2018, 33, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Lance, E.; Arnich, N.; Maignien, T.; Biré, R. Occurrence of β-N-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) and Isomers in Aquatic Environments and Aquatic Food Sources for Humans. Toxins (Basel) 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.A.; Davis, D.A.; Mash, D.C.; Metcalf, J.S.; Banack, S.A. Dietary exposure to an environmental toxin triggers neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2016, 283. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, A.S.; Gehringer, M.M.; Welch, J.H.; Neilan, B.A. Does α-amino-β-methylaminopropionic acid (BMAA) play a role in neurodegeneration? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3728–3746. [CrossRef]

- Masrori, P.; Van Damme, P. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1918–1929. [CrossRef]

- Noor Eddin, A.; Alfuwais, M.; Noor Eddin, R.; Alkattan, K.; Yaqinuddin, A. Gut-Modulating Agents and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Son, J.; Lee, D.; Tsai, J.; Wang, D.; Chocron, E.S.; Jeong, S.; Kittrell, P.; Murchison, C.F.; Kennedy, R.E.; Tobon, A.; Jackson, C.E.; Pickering, A.M. Gut- and oral-dysbiosis differentially impact spinal- and bulbar-onset ALS, predicting ALS severity and potentially determining the location of disease onset. BMC Neurol. 2022, 22, 62. [CrossRef]

- Rizos, E.; Pyleris, E.; Pimentel, M.; Triantafyllou, K.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. Small intestine bacterial overgrowth can form an indigenous proinflammatory environment in the duodenum: A prospective study. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.L.; Fournier, C.; Houser, M.C.; Tansey, M.; Glass, J.; Hertzberg, V.S. Potential role of the gut microbiome in ALS: A systematic review. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2018, 20, 513–521. [CrossRef]

- Kakaroubas, N.; Brennan, S.; Keon, M.; Saksena, N.K. Pathomechanisms of Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in ALS. Neurosci. J. 2019, 2019, 2537698. [CrossRef]

- Matzaras, R.; Nikopoulou, A.; Protonotariou, E.; Christaki, E. Gut microbiota modulation and prevention of dysbiosis as an alternative approach to antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2022, 95, 479–494.

- Brenner, D.; Hiergeist, A.; Adis, C.; Mayer, B.; Gessner, A.; Ludolph, A.C.; Weishaupt, J.H. The fecal microbiome of ALS patients. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 61, 132–137. [CrossRef]

- Fondell, E.; O’Reilly, E.J.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Falcone, G.J.; Kolonel, L.N.; Park, Y.; McCullough, M.L.; Ascherio, A. Dietary fiber and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: results from 5 large cohort studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 1442–1449. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; Calder, P.C.; Sanders, M.E. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; Verbeke, K.; Reid, G. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [CrossRef]

- Harijan, A.K.; Kalaiarasan, R.; Ghosh, A.K.; Jain, R.P.; Bera, A.K. The neuroprotective effect of short-chain fatty acids against hypoxia-reperfusion injury. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 131, 103972. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Sun, J. Probiotics and microbial metabolites maintain barrier and neuromuscular functions and clean protein aggregation to delay disease progression in TDP43 mutation mice. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2363880. [CrossRef]

- Mincic, A.M.; Antal, M.; Filip, L.; Miere, D. Modulation of gut microbiome in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1832–1849. [CrossRef]

- Niccolai, E.; Martinelli, I.; Quaranta, G.; Nannini, G.; Zucchi, E.; De Maio, F.; Gianferrari, G.; Bibbò, S.; Cammarota, G.; Mandrioli, J.; Masucci, L.; Amedei, A. Fecal microbiota transplantation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: clinical protocol and evaluation of microbiota immunity axis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2761, 373–396. [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Juliá, S.; Obrador, E.; López-Blanch, R.; Oriol-Caballo, M.; Moreno-Murciano, P.; Estrela, J.M. Ketogenic effect of coconut oil in ALS patients. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1429498. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.C.L.; Johnston, S.E.; Simpson, P.; Chang, D.K.; Mather, D.; Dick, R.J. Time-restricted ketogenic diet in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a case study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1329541. [CrossRef]

- Norgren, J.; Kåreholt, I.; Sindi, S. Is there evidence of a ketogenic effect of coconut oil? Commentary: Effect of the Mediterranean diet supplemented with nicotinamide riboside and pterostilbene and/or coconut oil on anthropometric variables in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. A pilot study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1333933. [CrossRef]

- Moțățăianu, A.; Șerban, G.; Andone, S. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Microbiota-Gut-Brain Cross-Talk with a Focus on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Sun J, Huang T, Debelius JW, Fang F. Gut microbiome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A systematic review of current evidence. J Intern Med. 2021 Oct;290(4):758-788. [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Wang X, Yang S, Meng F, Wang X, Wei H, Chen T. Evaluation of the Microbial Diversity in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Using High-Throughput Sequencing. Front Microbiol. 2016 Sep 20;7:1479. [CrossRef]

- Rowin J, Xia Y, Jung B, Sun J. Gut inflammation and dysbiosis in human motor neuron disease. Physiol Rep. 2017 Sep;5(18):e13443. PMID: 28947596; PMCID: PMC5617930. [CrossRef]

- Zhai CD, Zheng JJ, An BC, Huang HF, Tan ZC. Intestinal microbiota composition in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: establishment of bacterial and archaeal communities analyses. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019 Aug 5;132(15):1815-1822. PMID: 31306225; PMCID: PMC6759115. [CrossRef]

- Blacher E, Bashiardes S, Shapiro H, Rothschild D, Mor U, Dori-Bachash M, Kleimeyer C, Moresi C, Harnik Y, Zur M, Zabari M, Brik RB, Kviatcovsky D, Zmora N, Cohen Y, Bar N, Levi I, Amar N, Mehlman T, Brandis A, Biton I, Kuperman Y, Tsoory M, Alfahel L, Harmelin A, Schwartz M, Israelson A, Arike L, Johansson MEV, Hansson GC, Gotkine M, Segal E, Elinav E. Potential roles of gut microbiome and metabolites in modulating ALS in mice. Nature. 2019 Aug;572(7770):474-480. Epub 2019 Jul 22. PMID: 31330533. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Q, Shen J, Chen K, Zhou J, Liao Q, Lu K, Yuan J, Bi F. The alteration of gut microbiome and metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Sci Rep. 2020 Aug 3;10(1):12998. PMID: 32747678; PMCID: PMC7398913. [CrossRef]

- Nicholson K, Bjornevik K, Abu-Ali G, Chan J, Cortese M, Dedi B, Jeon M, Xavier R, Huttenhower C, Ascherio A, Berry JD. The human gut microbiota in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2021 May;22(3-4):186-194. Epub 2020 Nov 2. PMID: 33135936. [CrossRef]

- 90Ngo ST, Restuadi R, McCrae AF, Van Eijk RP, Garton F, Henderson RD, Wray NR, McCombe PA, Steyn FJ. Progression and survival of patients with motor neuron disease relative to their fecal microbiota. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2020 Nov;21(7-8):549-562. Epub 2020 Jul 9. PMID: 32643435. [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia D, Bozzi Cionci N, Baffoni L, Amoruso A, Pane M, Mogna L, Gaggìa F, Lucenti MA, Bersano E, Cantello R, De Marchi F, Mazzini L. A prospective longitudinal study on the microbiota composition in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC Med. 2020 Jun 17;18(1):153. PMID: 32546239; PMCID: PMC7298784. [CrossRef]

- Hertzberg VS, Singh H, Fournier CN, Moustafa A, Polak M, Kuelbs CA, Torralba MG, Tansey MG, Nelson KE, Glass JD. Gut microbiome differences between amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients and spouse controls. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2022 Feb;23(1-2):91-99. Epub 2021 Apr 5. PMID: 33818222; PMCID: PMC10676149. [CrossRef]

- Liu K, Guo Q, Ding Y, Luo L, Huang J, Zhang Q. Alterations in nasal microbiota of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2024 Jan 20;137(2):162-171. Epub 2023 Jul 21. PMID: 37482646; PMCID: PMC10798702. [CrossRef]

- Feng R, Zhu Q, Wang A, Wang H, Wang J, Chen P, Zhang R, Liang D, Teng J, Ma M, Ding X, Wang X. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. 2024 Dec 2;22(1):566. PMID: 39617896; PMCID: PMC11610222. [CrossRef]

- Ning J, Huang SY, Chen SD, Zhang YR, Huang YY, Yu JT. Investigating Casual Associations Among Gut Microbiota, Metabolites, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;87(1):211-222. PMID: 35275534. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Zhuang Z, Zhang G, Huang T, Fan D. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between 98 genera of the human gut microbiota and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a 2-sample Mendelian randomization study. BMC Neurol. 2022 Jan 3;22(1):8. PMID: 34979977; PMCID: PMC8721912. [CrossRef]

- Guo K, Figueroa-Romero C, Noureldein MH, Murdock BJ, Savelieff MG, Hur J, Goutman SA, Feldman EL. Gut microbiome correlates with plasma lipids in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2024 Feb 1;147(2):665-679. PMID: 37721161; PMCID: PMC10834248. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Kurilshikov A, Radjabzadeh D, Turpin W, Croitoru K, Bonder MJ, Jackson MA, Medina-Gomez C, Frost F, Homuth G, Rühlemann M, Hughes D, Kim HN; MiBioGen Consortium Initiative; Spector TD, Bell JT, Steves CJ, Timpson N, Franke A, Wijmenga C, Meyer K, Kacprowski T, Franke L, Paterson AD, Raes J, Kraaij R, Zhernakova A. Meta-analysis of human genome-microbiome association studies: the MiBioGen consortium initiative. Microbiome. 2018 Jun 8;6(1):101. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Cai X, Lao L, Wang Y, Su H, Sun H. Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Historical Overview and Future Directions. Aging Dis. 2024 Feb 1;15(1):74-95. PMID: 37307822; PMCID: PMC10796086. [CrossRef]

- Monselise EB, Vyazmensky M, Scherf T, Batushansky A, Fishov I. D-Glutamate production by stressed Escherichia coli gives a clue for the hypothetical induction mechanism of the ALS disease. Sci Rep. 2024 Aug 6;14(1):18247. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 6;14(1):20873. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-71813-5. PMID: 39107374; PMCID: PMC11303787. [CrossRef]

- Wang IF, Guo BS, Liu YC, Wu CC, Yang CH, Tsai KJ, Shen CK. Autophagy activators rescue and alleviate pathogenesis of a mouse model with proteinopathies of the TAR DNA-binding protein 43. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Sep 11;109(37):15024-9. Epub 2012 Aug 29. PMID: 22932872; PMCID: PMC3443184. [CrossRef]

- Stacchiotti A, Corsetti G. Natural Compounds and Autophagy: Allies Against Neurodegeneration. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Sep 22;8:555409. PMID: 33072744; PMCID: PMC7536349. [CrossRef]

| Potential microbiota alterations in ALS | Cases | Controls | Exclusion criteria | Methodology for metagenome | Geographical background | Reference |

| Decreased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in ALS cases; increased Dorea; decreased Oscillibacter, Anaerostipes, Lachnospiraceae at genus level for cases | 6 ALS patients | 5 healthy controls, with apparently no matching in BMI, sex or age | FVC1 < 70%, mental illness or neurological disorders, or nocturnal hypoventilation | Bacterial 16S rRNA (V3-V4 region) sequencing for gut microbiome profiling | China | Fang et al. 2016, [84] |

| ALS cases showed decreased diversity; with 3 of 5 ALS patients having low Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio. | 5 ALS patients (4 female) | 96 Healthy controls, with apparent no matching in BMI, sex or age | Cases with concurrent intestinal diseases or abdominal symptoms | Bacterial 16S rRNA-based PCR with multiple primer design aimed at phylum and class level classification | USA | Rowin et al. 2017[85] |

| Higher OTU number in cases, though indexes of neither alpha nor beta diversity differed significantly; only one OTU (uncultured Ruminococcaceae) at the genus level differed significantly. | 25 ALS patients (13 female) | 32 healthy controls (16 female) matched for age and sex | Recent antibiotic use, neoplastic disease, autoimmune disease, gastrointestinal disorders, or active infections | Bacterial 16S rRNA sequencing (454 pyrosequencing) | Germany | Brenner et al. 2018, [71] |

| Increased Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in cases; ALS associated to increased Methanobrevibacter, and decreased Faecalibacterium and Bacteroides, at the genus level ; unclear declaration of methods employed for statistical analyses. | 8 ALS patients (4 female) | ; 8 healthy controls (4 female) with no declared age, sex or dietary regimes match | ALS-like illnesses, severe systemic disorders, and excessive eating or drinking throughout the previous two weeks | Bacterial 16S rRNA (V4-V5 region) sequencing | China | Zhai et al. 2019 [86] |

| Several microbiome differences between cases and controls, with Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum being correlated with serum nicotinamide levels, with alterations in gene content for tryptophan and nicotinamide metabolism in cases. | 37 ALS patients | 29 healthy controls consisting of family members; matched for age and BMI | Pregnancy, fertility therapies, antibiotics, probiotics, and inflammatory or malignant diseases were among the exclusion criteria. | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing | Israel | Blacher et al. 2019,[87] |

| Increased alpha diversity ( evaluated by Shannon index) but not beta diversity in ALS; increased in Bacteroidetes; decreased in Firmicutes, at phylum level; Increased in Kineothrix, Parabacteroides, Odoribacter, Sporobacter, Eisenbergiella, Mannheimia, Anaerotruncus, and unclassified Porphyromonadaceae; decreased in Megamonas, at the genus level | 20 probable or definite ALS patients (8 female) | 20 healthy controls (8 female)with overall similar living conditions and dietary structure; probable age and sex matching | Diseases and drugs of the gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal surgical history, and nutritional imbalances in the diet | Two methods: 16S rRNA (V4 region)sequencing for gut bacterial microbiome profiling, and shotgun metagenomic sequencing for gut microbiome profiling and functional measure | China | Zeng et al. 2020, [88] |

| Similar alpha and beta diversities; increased in Escherichia (unclassified) and Streptococcus; decreased in Bilophila, (unclassified) at the genus level; Clostridiaceae bacterium JC118, Coprobacter fastidiosus, Eubacterium eligens, and Ruminococcus sp 5 1 39 BF ;with two butyrate-producing bacteria (Eubacterium rectale and Roseburia intestinalis) significantly lower in ALS; total relative abundance of the eight dominant butyrate producers significantly lower in ALS; | 66 at least suspected ALS (26 female); | 61 healthy controls (36 female), consisting of caregivers and other healthy individuals; 12 neurodegenerative controls (7 female) | Adults (older than 18 years), not employing probiotics for 14 days, no use of antibiotics or immune suppressants in the last three months, and no active inflammatory bowel disease, GI malignancy, irritable bowel syndrome, or other GI sickness needing treatment (apart from gastroesophageal reflux) for more than 18 years | Two methods: 16S rRNA (V4 region)sequencing for gut bacterial microbiome profiling, and shotgun metagenomic sequencing for gut microbiome profiling and functional measure | USA | Nicholson et al. 2020, [89] |

| No difference in alpha and beta diversity | 49 Motor Neuron Disease patients (15 female); | 51 healthy controls (21 female)consisting of spouses, friends, and family members; Age, sex and BMI matching | Individuals with a history of diabetes, gastrostomy use, antibiotic or probiotic use, or FVC< 60% | Bacterial 16S rRNA (V6-V8 region) sequencing for gut microbiome profiling | Australia | Ngo et al. 2020, Australia [90] |

| Increased alpha diversity in cases (Chao1 index) also with changes in beta diversity; No changes in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio; increased in Cyanobacteria at the phylum level; increased in Lactobacillus, Citrobacter, Coprococcus, at the genus level | 50 probable or defined ALS patients (22 female); | 50 controls (22 female) unrelated subjects, unrelated family members, or friends; matched for sex, age, origin, eating habits, and geographic region | Individuals with noninvasive ventilation, gastrostomy, illnesses, antibiotic or medication use during the last eight weeks, or FVC < 50% | Bacterial 16S rRNA (V3-V4 region) sequencing for gut microbiome profiling | Italy | Di Gioia et al. 2020,[91] |

| Patient microbiomes showed higher diversity with a higher number of taxa. ALS patients were also deficient in Prevotella spp | 10 ALS patients (3 female); | 30 Healthy controls (20 female)with overall similar living conditions and dietary structure; probable age and sex matching | Patients receiving enteral nutrition as well as those with a history of bowel disease other than constipation, malignancy, dementia/other cognitive disorders, or Parkinson’s disease /other neurodegenerative diseases. | 16S rRNA (V4 region) gene sequencing | USA | Hertzberg et al., 2022 [92] |

| Nasal microbiome changes over ALS, with lower alpha diversity. Gaiella, Sphingomonas, Polaribacter_1, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Klebsiella, and Alistipes werehigher in ALS patients, at the genus level Nosignificant differences in nasal microbiota richness and evenness were detected in ALS patients | 66 ALS patients (29 female) | 40 healthy controls, caregivers(the spouses of the ALS patients) who lived in closeproximity with the patients, potentially matched for diet, daily schedule, pollution exposure,and other related factors. | Human immunodeficiencyvirus infection, primary immunodeficiency,systemic inflammatory disorder, or history of intranasaldrug administration, including antibiotics, immunesuppressants, or probiotics within the prior 3 years, andoral administration or infusion of antibiotics in theprior 2 months. | 16S rRNA (V3-V4 region) gene sequencing | China | Liu et al., 2024 [93] |

| No changes in alpha diversity associated to ALS. Lower Bifidobacterium in ALS, at the genus level | 27 ALS patients (12 females) | 15 healthy controls, chosen as donors in a fecal microbiota transplantation procedure | FVC<70%, having a first-degree relative ormore than one relative with ALS, a diagnosis of majordepression or psychosis acuteinfection or inflammatory conditions within the preceding4 weeks, history of abdominal surgery, autoimmuneor chronic inflammatory conditions , probiotic orantibiotic use in the past 3 months, active malignancy,pregnancy, and drug abuse. | 16S rRNA (V3-V4 region) gene sequencing | China | Feng et al., 2024 [94] |

| Decreased abundance of Fusicatenibacter and Catenibacterium; increased abundance of Lachnospira; | 20,806 cases with ALS | 59,804 controls (GWAS summary statistics from IALSC); 18,340 participants (GWAS summary statistics from the MiBioGen); 7824 participants (GWAS summary statistics from TwinsUK and KORA) | Ning et al.,2022[95] | |||

| Increased abundance of Soutella and Lactobacillales order; interaction with genetically predicted increased susceptibility to ALS | 20,806 cases with ALS | 59,804 controls (GWAS summary statistics from IALSC); 1812 sanples (GWAS summary statistics); 7824 adult individuals (GWAS summary statistics from 2 European cohorts) | Zhang et al., 2022 [96] | |||

| Lower alpha diversity in ALS patients, beta-diversity significantly different as well, Firmicutes and Cyanobacteria differed in ALS patients, at phylum level. Higher relative abundance in ALS of Bacteroides Parasutterella and Lactococcus and higher relative abundance in control of Faecalibacterium) and Bifidobacterium at genus level. Lower abundance of butyrate-producing species in ALS | 75 ALS patients (32 females) | 110 Controls (66 females), matched for sex and age | For controls neurodegenerative condition or family history of ALS | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V4 region) | USA | Guo et al., 2024 [97] |

| No changes in alpha or beta diversity in ALS, nor in firmicutes to bacteroidetes ratio; ALS patients showed higher Fusobacteria and Acidobacteria at the phylum level | 16 diagnosed ALS patients (8 female) | 12 controls (6 female) matched for age and sex, among spouses and caregivers | Cases with with GI diseases or those treated with drugs (such as antibiotics) that could alter nutritional balance and affect intestinal microbiota. Antibiotic use within 2 months | 16S rRNA gene sequencing (V3-V4 region) | Spain | Fontdevila et al., 2024 [13] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).