Submitted:

29 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction & Background

Review

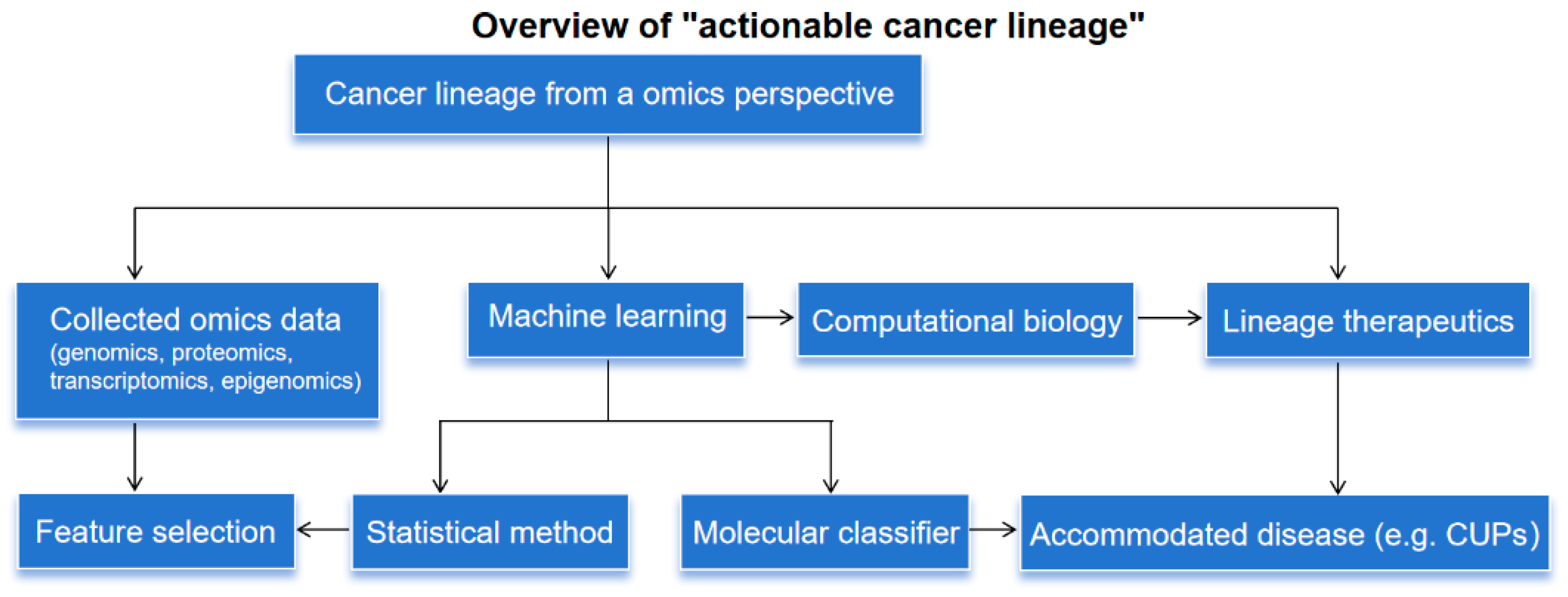

Cancer Lineage Plasticity Guided by Machine Learning

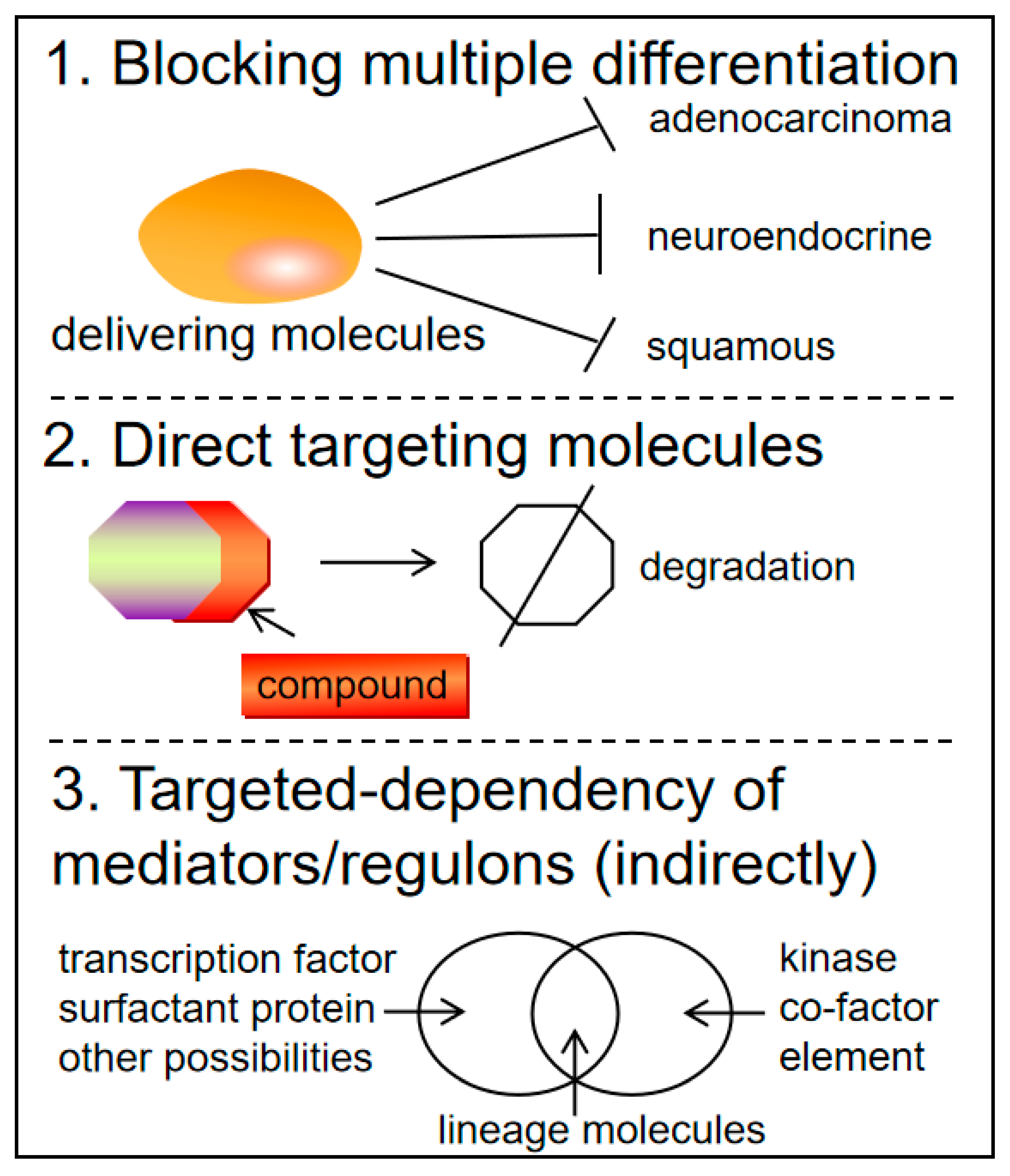

Clinical Applications and Future Directions

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Subbiah V, Gouda MA, Ryll B, Burris HA, 3rd, et al. The evolving landscape of tissue-agnostic therapies in precision oncology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 2024. [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, JP. Every gene can (and possibly will) be associated with cancer. Trends in genetics 2022, 38, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Zoubeidi, A.; Beltran, H.; Selth, L.A. The Transcriptional and Epigenetic Landscape of Cancer Cell Lineage Plasticity. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 1771–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M.; Sekine, S.; Sato, T. Decoding the basis of histological variation in human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 24, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haigis, K.M.; Cichowski, K.; Elledge, S.J. Tissue-specificity in cancer: The rule, not the exception. Science 2019, 363, 1150–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoadley, K.A.; Yau, C.; Hinoue, T.; Wolf, D.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Drill, E.; Shen, R.; Taylor, A.M.; Cherniack, A.D.; Thorsson, V.; et al. Cell-of-Origin Patterns Dominate the Molecular Classification of 10,000 Tumors from 33 Types of Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 291–304.e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, G.; Fails, D.; Nagarajan, P.; Ge, Y. Unraveling cancer lineage drivers in squamous cell carcinomas. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 206, 107448–107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rindi, G.; Inzani, F. Neuroendocrine neoplasm update: toward universal nomenclature. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2020, 27, R211–R218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Lyu, Q. Challenges and opportunities in rare cancer research in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martincorena I, Raine KM, Gerstung M, Dawson KJ, et al. Universal Patterns of Selection in Cancer and Somatic Tissues. Cell 2017, 171, 1029–1041.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dressler, L.; Bortolomeazzi, M.; Keddar, M.R.; Misetic, H.; Sartini, G.; Acha-Sagredo, A.; Montorsi, L.; Wijewardhane, N.; Repana, D.; Nulsen, J.; et al. Comparative assessment of genes driving cancer and somatic evolution in non-cancer tissues: an update of the Network of Cancer Genes (NCG) resource. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Shan, A.; Bailey, M.H.; Huang, K.-L.; et al. Pan-cancer analysis of somatic mutations across 21 neuroendocrine tumor types. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Teng, L.; Guo, L.; Liang, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Li, R.; et al. Genomic characterization reveals distinct mutation landscapes and therapeutic implications in neuroendocrine carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riet, J.; van de Werken, H.J.G.; Cuppen, E.; Eskens, F.A.L.M.; Tesselaar, M.; van Veenendaal, L.M.; Klümpen, H.-J.; Dercksen, M.W.; Valk, G.D.; Lolkema, M.P.; et al. The genomic landscape of 85 advanced neuroendocrine neoplasms reveals subtype-heterogeneity and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yachida, S.; Totoki, Y.; Noë, M.; Nakatani, Y.; Horie, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Nakamura, H.; Saito-Adachi, M.; Suzuki, M.; Takai, E.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Gastrointestinal System. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 692–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.; Ruiz, P.; Ito, T.; Sellers, W.R. Targeting pan-essential genes in cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage SR, Yi X, Lei JT, Wen B, et al. Pan-cancer proteogenomics expands the landscape of therapeutic targets. Cell 2024, 187, 4389–4407.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Lih, T.M.; Pan, J.; Höti, N.; Dong, M.; Cao, L.; Hu, Y.; Cho, K.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Eguez, R.V.; et al. Proteomic signatures of 16 major types of human cancer reveal universal and cancer-type-specific proteins for the identification of potential therapeutic targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilis, T.; Petre, M.L.; Vatsellas, G.; Ainatzoglou, A.; Stamoula, E.; Sachinidis, A.; Lamprinou, M.; Dardalas, I.; Vamvakaris, I.N.; Gkiozos, I.; et al. Lung Cancer Proteogenomics: Shaping the Future of Clinical Investigation. Cancers 2024, 16, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen F, Zhang Y, Gibbons DL, Deneen B, et al. Pan-Cancer Molecular Classes Transcending Tumor Lineage Across 32 Cancer Types, Multiple Data Platforms, and over 10,000 Cases. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 2182–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Zheng, S.; Yao, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Yin, E.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; et al. Molecular subtypes of neuroendocrine carcinomas: A cross-tissue classification framework based on five transcriptional regulators. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 1106–1125.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejas, P.; Xie, Y.; Font-Tello, A.; Lim, K.; Syamala, S.; Qiu, X.; Tewari, A.K.; Shah, N.; Nguyen, H.M.; Patel, R.A.; et al. Subtype heterogeneity and epigenetic convergence in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terekhanova, N.V.; Karpova, A.; Liang, W.-W.; Strzalkowski, A.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Southard-Smith, A.N.; Iglesia, M.D.; Wendl, M.C.; Jayasinghe, R.G.; et al. Epigenetic regulation during cancer transitions across 11 tumour types. Nature 2023, 623, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang MT, Penson A, Desai NB, Socci ND, et al. Small-Cell Carcinomas of the Bladder and Lung Are Characterized by a Convergent but Distinct Pathogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 1965–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsunemoto, R.; Lee, S.; Szűcs, A.; Chubukov, P.; Sokolova, I.; Blanchard, J.W.; Eade, K.T.; Bruggemann, J.; Wu, C.; Torkamani, A.; et al. Diverse reprogramming codes for neuronal identity. Nature 2018, 557, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loriot, Y.; Kamal, M.; Syx, L.; Nicolle, R.; Dupain, C.; Menssouri, N.; Duquesne, I.; Lavaud, P.; Nicotra, C.; Ngocamus, M.; et al. The genomic and transcriptomic landscape of metastastic urothelial cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorman, A.R.; Benitez, E.K.; Cambuli, F.; Jiang, Q.; Mahmoud, A.; Lumish, M.; Hartner, S.; Balkaran, S.; Bermeo, J.; Asawa, S.; et al. Progressive plasticity during colorectal cancer metastasis. Nature 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinze, G.; Wallisch, C.; Dunkler, D. Variable selection – A review and recommendations for the practicing statistician. Biom. J. 2018, 60, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Wang, C. A comparative study of clustering methods on gene expression data for lung cancer prognosis. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalise P, Kwon D, Fridley BL, Mo Q. Statistical Methods for Integrative Clustering of Multi‐omics Data. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2023, 2629, 73–93.

- Mamatjan Y, Agnihotri S, Goldenberg A, Tonge P, et al. Molecular Signatures for Tumor Classification: An Analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas Data. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD 2017, 19, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, H.-C.; Qin, L.-X. Making External Validation Valid for Molecular Classifier Development. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, J.; Ni, S.; Tan, C.; Xu, M.; Dong, L.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Q.; Du, X. Pan-cancer transcriptome analysis reveals a gene expression signature for the identification of tumor tissue origin. Mod. Pathol. 2016, 29, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydzewski, N.R.; Shi, Y.; Li, C.; Chrostek, M.R.; Bakhtiar, H.; Helzer, K.T.; Bootsma, M.L.; Berg, T.J.; Harari, P.M.; Floberg, J.M.; et al. A platform-independent AI tumor lineage and site (ATLAS) classifier. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia D, Leon AJ, Cabanero M, Pugh TJ, et al. Minimalist approaches to cancer tissue-of-origin classification by DNA methylation. Modern pathology 2020, 33, 1874–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz FD, Matushansky I. Solid tumor differentiation therapy - is it possible? Oncotarget 2012, 3, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Cross, R.S.; Jenkins, M.R. Synthetic biology, genetic circuits and machine learning: a new age of cancer therapy. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelluti, M.A.; Poeta, V.M.; Valsoni, S.; Quarato, P.; Merlin, S.; Merelli, I.; Lombardo, A. Durable and efficient gene silencing in vivo by hit-and-run epigenome editing. Nature 2024, 627, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Ma, L.; Xu, S.; Lin, Y. Deciphering a global source of non-genetic heterogeneity in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 9019–9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim N, Hwang CY, Kim T, Kim H, et al. A Cell-Fate Reprogramming Strategy Reverses Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Cancer Cells While Avoiding Hybrid States. Cancer research 2023, 83, 956–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montagud, A.; Béal, J.; Tobalina, L.; Traynard, P.; Subramanian, V.; Szalai, B.; Alföldi, R.; Puskás, L.; Valencia, A.; Barillot, E.; et al. Patient-specific Boolean models of signalling networks guide personalised treatments. eLife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjödahl, G.; Eriksson, P.; Liedberg, F.; Höglund, M. Molecular classification of urothelial carcinoma: global mRNA classification versus tumour-cell phenotype classification. J. Pathol. 2017, 242, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arad, G.; Geiger, T. Functional Impact of Protein–RNA Variation in Clinical Cancer Analyses. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Qin, Z.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, J.; Chen, L.; Luo, R.; Zhang, X.; et al. Proteomic analysis reveals key differences between squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas across multiple tissues. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Q.; Gong, H.; Gao, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Zheng, H.; Wu, Z.; et al. Spatially resolved proteomic map shows that extracellular matrix regulates epidermal growth. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhrmann, L.; Werner, M.; Oleś, M.; Mock, A.; Uhrig, S.; Jahn, A.; Kreutzfeldt, S.; Fröhlich, M.; Hutter, B.; Paramasivam, N.; et al. Comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis in cancer of unknown primary guides molecularly-informed therapies despite heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, J.; Eizenga, J.M.; Beale, H.C.; Vaske, O.M.; Paten, B. Bayesian Framework for Detecting Gene Expression Outliers in Individual Samples. JCO Clin. Cancer Informatics 2020, 4, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xue, Y.; Qin, Z.; Fang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, C.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Counteracting lineage-specific transcription factor network finely tunes lung adeno-to-squamous transdifferentiation through remodeling tumor immune microenvironment. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Stanton, S.; E Castle, P.; Finn, O.J.; Sei, S.; A Emens, L. Advances and challenges in cancer immunoprevention and immune interception. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e007815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, V.H.; Pipinikas, C.P.; Pennycuick, A.; Lee-Six, H.; Chandrasekharan, D.; Beane, J.; Morris, T.J.; Karpathakis, A.; Feber, A.; E Breeze, C.; et al. Deciphering the genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic landscapes of pre-invasive lung cancer lesions. . 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Koehler, A.N. Transcription Factor Inhibition: Lessons Learned and Emerging Targets. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.Y. Targeting Super-Enhancers for Disease Treatment and Diagnosis. Molecules and cells 2018, 41, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes DN, Oluoha O, Schwartz DL. For Squamous Cancers, the Streetlamps Shine on Occasional Keys, Most Baskets Are Empty, and the Umbrellas Cannot Keep Us Dry: A Call for New Models in Precision Oncology. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Xiao, G.; Gerber, D.; Minna, J.D.; Xie, Y. Lung Cancer Computational Biology and Resources. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2021, 12, a038273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Song, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhao, J.; Xie, L.; et al. scGRN: a comprehensive single-cell gene regulatory network platform of human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D293–D303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).