1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an umbrella term used to describe disorders characterized by hepatic steatosis (histologically or radiologically identified) in absence of excessive alcohol consumption and other secondary causes of hepatic fat accumulation[

1,

2]. NAFLD encompasses a wide spectrum ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which may advance to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis with liver failure or/and hepatocellular carcinoma[

3,

4]. It is the most common liver disease in Western countries with approximately a global prevalence of 30% in adults, causing a constantly increasing clinical and economic burden worldwide[

5]. In 2020, the entity was renamed to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), underlining the metabolic substrate of the disorder which defines its pathophysiology. MAFLD incorporates a set of “positive” criteria regardless of alcohol consumption or other concurrent liver diseases. The requirements for the diagnosis of MAFLD include evidence of hepatic steatosis (based on histology, imaging, or blood biomarkers) in addition to one of the following three criteria: overweight/obesity, presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), or evidence of metabolic dysregulation[

6]. Therefore, MAFLD is generally considered the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome[

7]. Lately, the terminology of metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease (MASLD) was introduced to describe the previously called NAFLD entity. MASLD diagnostic criteria incorporate the presence of liver steatosis with the existence of at least one cardiometabolic risk factor, such as increased body mass index (BMI), fasting serum glucose, plasma triglycerides, blood pressure, and HDL cholesterol, in the absence of any other obvious cause of hepatic steatosis [

8].

The pathophysiology of the disease has yet to be completely elucidated due to the complex mechanisms involved. The first proposed pathogenesis, termed as the «two-hit hypothesis», included the consumption of high fat diet and the embracement of a sedentary lifestyle lead to obesity and insulin resistance (IR), resulting to the accumulation of triglycerides (TAGs) in the liver (first hit) and prompting the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to fat accumulation and necroinflammation (second hit) [

9] . Nowadays, the “multiple-hit hypothesis” has been proposed, according to which, dietary, genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors cause obesity, IR, gut microbiome alterations, ectopic fat accumulation, adipose tissue dysfunction, dysregulation of autophagy and mitochondrial function, leading to oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[

10].

The prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and fatal cardiovascular adverse events are higher in patients with MASLD, with recent evidence suggesting that NAFLD is an independent risk factor for CVD occurrence [

11]. Furthermore, CVD is the most common cause of death in these patients, surpassing liver complications-related deaths[

11,

12]. In the majority of NAFLD patients, several conventional cardiovascular risk factors are identified. Therefore, these patients are candidates for therapeutic interventions that target on the reduction of the high cardiovascular burden while simultaneously may have a positive effect on NAFLD[

13].

This review provides current knowledge on the epidemiologic association of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD to CVD mortality and morbidity and enlightens the possible underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms linking NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD with CVD. It also highlights potential common therapeutic interventions with cardiometabolic drugs such as anti-hypertensive drugs, hypolipidemic agents, glucose-lowering medications, salicylic acid and the thyroid hormone receptor-beta agonist that may improve outcomes of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD.

2. Epidemiologic association between MASLD and CVD incidence and mortality

Increasing evidence shows a strong correlation between NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and CVD. NAFLD seems to be independently correlated with cardiovascular adverse events even after adjustment for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors such as sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, hypertension, or dyslipidemia. This knowledge has been established by several systematic reviews and meta-analyses, summarized in

Table 1.

A recent meta-analysis by Mantovani et al., which included 36 observational studies, examined the risk of incidence of CVD events amongst adults with and without NAFLD and demonstrated that NAFLD is linked to an increased long-term risk of fatal or non-fatal CVD events (pooled random-effects HR= 1.45, 95% CI 1.31-1.61), especially in patients with more advanced liver disease and higher fibrosis stage (pooled random-effects HR 2.50, 95% CI 1.68–3.72)[

14]. Wu et al. reported that NAFLD was correlated with an increased risk of non-fatal CVD events (HR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.10–1.72), such as CAD, hypertension, and atherosclerosis, although, without statistically significant association with CVD mortality[

15]. The latter finding may be attributed to the fluctuating frequencies of cardiovascular comorbidities among the subjects of diverse studies or the implementation of varying diagnostic criteria for NAFLD and NASH. However, in a large-scale prospective cohort study with 215,245 participants, NAFLD was shown to be independently associated with CVD mortality (HR 1.61, 95% CI 1.42–1.82), acute myocardial infarction (AMI) mortality (HR 1.58, 95% CI 1.19–2.11) but not with stroke mortality (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.85–1.64)[

16] .

The pathologic hallmark of IR is implicated in the pathogenesis of CVD and the development and progression of MASLD. A meta-analysis of 11 studies by Zhou et al. showed that NAFLD patients with T2DM had a nearly twofold increase in CVD risk compared to patients without NAFLD (OR 2.20; 95% CI 1.67–2.90)[

17]. Moreover, a recently published nationwide population-based study with 7,796,763 participants in Korea reported that NAFLD in patients with T2DM (505.763 patients) was associated with a higher incidence rate of CVD such as myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and all-cause death, even in patients with mild NAFLD [

18].

In brief, the latest epidemiologic data demonstrate an independent association of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD with the manifestation of CVD and/or adverse cardiovascular events. Importantly, patients with more severe liver disease and fibrosis and patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and T2DM appear to have an increased risk for CV adverse events. While NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD is linked to increased all-cause mortality, its association with CVD mortality remains a controversial topic.

Table 1.

Meta-analyses evaluating the association of NAFLD and CVD events.

Table 1.

Meta-analyses evaluating the association of NAFLD and CVD events.

| Author |

Study design |

Population |

Results |

|

Mantovani et al. (2021) [14] |

Systematic review and meta-analysis |

36 observational studies

5,802,226 adults

335,132 individuals with baseline NAFLD (diagnosed with liver biopsy, imaging techniques, ICD 9/10 codes)

Median follow-up period: 6.5 years |

Increased risk of fatal or non-fatal CVD events in patients with NAFLD vs those without (pooled random-effects HR= 1.45, 95% CI 1.31-1.61).

Even higher risk with more severe NAFLD

(pooled random-effects HR= 2.50, 95% CI 1.68-3.72).

All risks were independent of other common cardiometabolic risk factors. |

|

Targher et al. (2016) [19] |

Meta-analysis |

16 observational studies

34,043 adults

36.3% of individuals with baseline NAFLD

Median follow-up period: 6.9 years |

Increased risk of fatal and/or non-fatal CVD events patients with NAFLD vs those without NAFLD (random effect OR= 1.64, 95% CI 1.26–2.13).

Even higher risk in patients with more severe NAFLD (random effect OR= 2.58; 95% CI 1.78–3.75). |

|

Abosheaishaa et al. (2024) [20] |

Systematic review and meta-analysis |

32 studies

5,610,990 individuals

567,729 patients with NAFLD |

Increased risk of

angina (RR= 1.45, 95% CI: 1.17-1.79), CAD (RR= 1.21, 95% CI: 1.07-1.38), Coronary artery calcium (CAC) >0 (RR= 1.39, 95% CI: 1.15-1.69), and calcified coronary plaques (RR= 1.55, 95% CI: 1.05-2.27).

No statistically significant association between NAFLD and CAC >100 (RR= 1.16, 95% CI: 0.97-1.38) and MI (RR= 1.70, 95% CI: 0.16 -18.32). |

|

Wu et al. (2016) [15] |

Systematic review and meta-analysis |

34 studies (21 cross-sectional studies, and 13 cohort studies)

164,494 participants

153,209 patients with NAFLD (diagnosed by U/S, CT or liver biopsy) |

Increased risk of prevalence (OR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.23–2.66) and incidence (HR = 1.37, 95% CI: 1.10–1.72) of CVD in patients with NAFLD vs those without NAFLD.

Increased risk of prevalence (OR = 1.87, 95% CI: 1.47–2.37) and incidence (HR = 2.31, 95% CI: 1.46–3.65) coronary artery disease (CAD), prevalence (OR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.14–1.36) and incidence (HR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.06–1.27) of hypertension and prevalence (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.07–1.62). atherosclerosis among patients with NAFLD than those without NAFLD.

No statistically significant difference in CVD mortality between patients with NAFLD and non-NAFLD participants (HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.86–1.41) |

|

Liu et al. (2019) [21] |

Meta-analysis |

14 studies

498,501 individuals

More of 95,111 patients with NAFLD |

Increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients with NAFLD vs those without (HR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.17–1.54).

No statistically significant association of NAFLD with CVD mortality (HR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.92–1.38). |

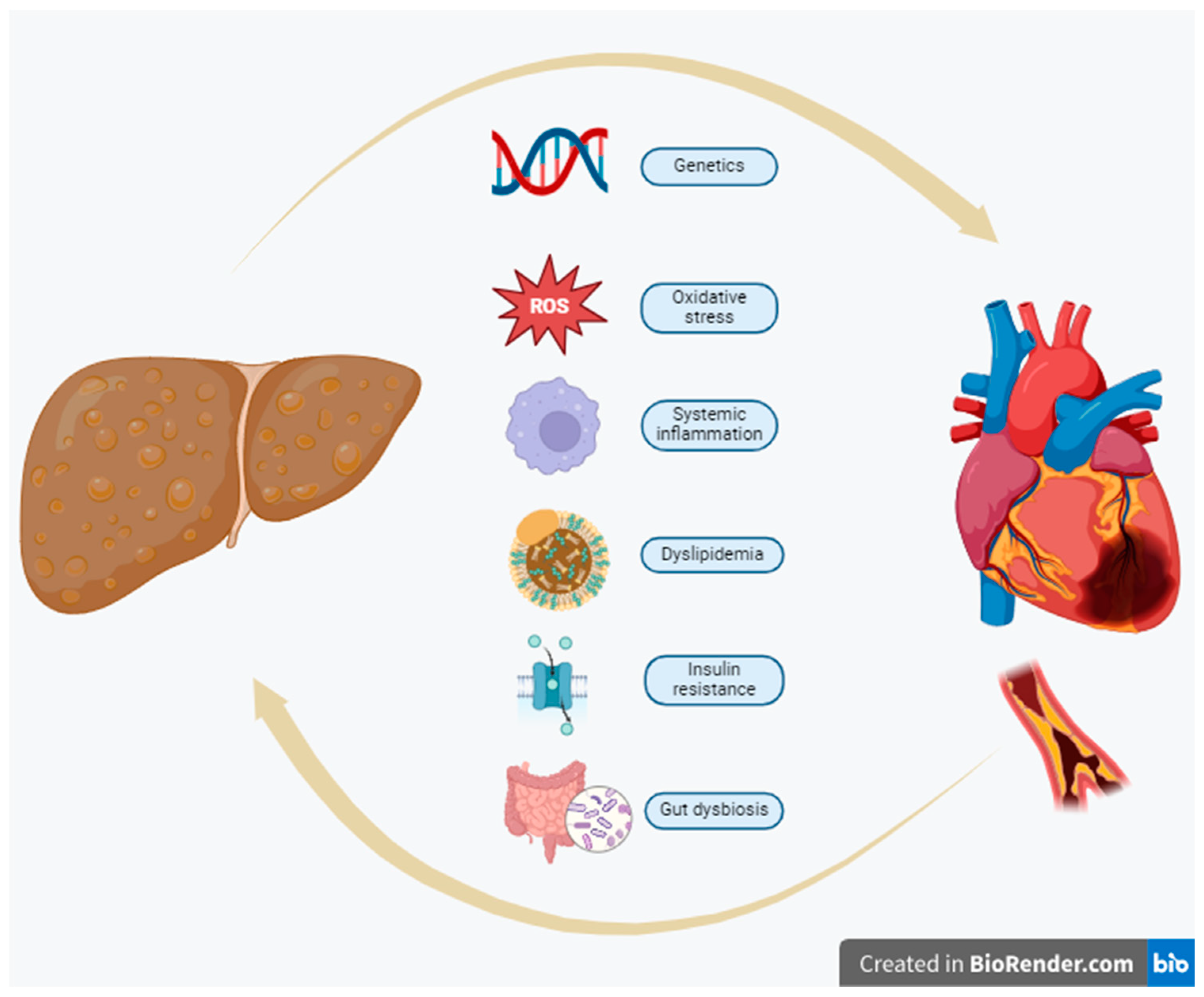

3. Pathophysiological linkage of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and CVD

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn. The underlying pathophysiologic linkage of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and CVDs involves many complex, frequently overlapping pathways[

22].

3.1. Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia includes a broad spectrum of lipid perturbations manifesting as increased plasma TG and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol.

Lipid metabolism is regulated by the liver via the combined action of de novo lipogenesis (DNL) and breakdown of lipids, as well as the uptake and secretion of serum lipoproteins[

23]. As hepatic fat accumulation is the hallmark of MASLD, it is clear why impaired lipid metabolism is identified as one of the major risk factors of the disease. Impaired liver uptake of serum lipids, increased hepatic DNL and altered export of very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) are observed in NAFLD[

24], leading to the accumulation of free fatty acids (FFA) in liver parenchyma and thus the development of steatohepatitis (NASH).

Overproduction of VLDL and LDL, in combination with low serum HDL levels contribute to the phenotype of atherogenic dyslipidemia that includes a predominance of particularly atherogenic, small dense LDL particles, which in turn initiates the cascade of atherosclerosis by penetration and accumulation of apolipoprotein-B-containing lipoproteins within the subendothelial layer of vessels[

25,

26]. LDL cholesterol in the vascular wall is further oxidized and stimulates innate immune response via toll-like receptors (TLRs)[

27]. Apo-B-containing particles play a crucial role in atherosclerosis development. Moreover, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins such as VLDL and intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) promote CVD development. In these particles apolipoprotein C3 is contained, which likely plays a role in activating inflammasome [

28], that, in turn, activates the interleukin (IL)-1β family via caspase-1, stimulating pro-inflammatory mediators IL-1, IL-6, and CRP in the vascular wall and promoting vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic CVD[

29]. Likewise, increased hepatic DNL in NAFLD is also associated with an increased production of saturated fatty acids, such as hepatic palmitic acid (C 16:0), which, in turn, can induce vascular inflammation by inflammasome activation [

30].

3.2. Inflammation– Oxidative stress

Liver inflammation in NAFLD can be considered a multifactorial process, in which inflammatory stimuli may derive from either hepatic tissue or extrahepatic regions, such as the adipose tissue and the gut[

31]. Circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines [IL-6, high sensitivity CRP, IL-1β, Tumor Necrosis Factor-a (TNF-α)] are often increased in patients with NAFLD, especially in NASH, indicating that low-grade systemic inflammation is a major component in disease progression[

32]. This systemic inflammation can, in turn, lead to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis progression and is associated with CVD [

25].

Hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) can trigger endothelial inflammation via microRNA-1 (miR-1), a critical component within EVs which suppresses Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) expression and activates the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway[

33]. The hepatic miRNAs can subsequently enter the bloodstream and trigger CVD through modifications in lipid metabolism and/or the induction of systemic inflammation [

34].

In patients with NAFLD, changes in methionine metabolism and subsequent alternation of homocysteine catabolism are implicated in the increased levels of serum homocysteine that are regularly seen[

35]. Elevated serum levels of homocysteine can deplete glutathione stores, leading to oxidative stress, and thus increased vascular resistance and impaired nitric oxide formation[

36,

37]. Superoxide-induced oxidate stress may also cause endothelial dysfunction, a crucial early step in atherosclerosis formation[

38].

3.3. Insulin Resistance (IR)

As already mentioned, IR has now been identified as one of the major drivers of hepatic steatosis in patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD, as well as a major risk factor for CVD. Systemic inflammation, visceral obesity, and augmented accumulation of dysfunctional ectopic adipose tissue lead to IR[

39].

Excessive intrahepatic accumulation of lipid metabolites, such as diacylglycerol, has been implicated as a mediator of IR [

40]. Visceral adipose tissue also contributes to NASH development by secreting several adipokines and pro-inflammatory molecules such as adiponectin, leptin, resistin, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, that, in turn, downregulate glucose transporter GLUT-4 expression [

41]. Furthermore, NAFLD, and in particular NASH, have been associated with high levels of Fetuin-A (FetA), a hepatokine that acts as tyrosine kinase inhibitor of insulin receptor in the liver leading to IR[

42,

43]. Most interestingly, FetA is also related with myocardial infarction and stroke, evidence that might render it as a possible causative link between NASH and CVD[

44].

It should be highlighted that IR results in compensatory persistent hyperinsulinemia, which is of crucial importance for the induction of unfavorable metabolic events[

45]. Both increased circulating glucose levels and hyperinsulinemia stimulate DNL in NAFLD. One of the underlying mechanisms of DNL is the activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) and carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP) transcription factors, which induce the expression of enzymes involved in lipogenesis[

46]. It has been observed that DNL contributes to the synthesis of 26% of intrahepatic triglycerides in NAFLD patients, compared to 5% in healthy individuals[

47].

Impaired insulin signaling has deleterious effects on the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle cells, enhancing endothelial dysfunction and the progression of atherosclerosis. Elevated insulin levels overactivate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase /protein kinase B (PI3K-PKB) pathway, enhancing the development or progression of atherosclerosis[

48]. Endothelial insulin resistance leads to increased expression of intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) due to the downregulation of the insulin receptor–Akt1 pathway[

49]. The activation of endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase in endothelial cells is also impaired, resulting in reduced production of NO. Vascular smooth muscle cells undergo phenotypic alternation, which may participate in atherosclerosis progression[

50]. Oxidative stress and concurrent activation of inflammatory pathways seem to be triggered by persistent hyperglycemia and high postprandial glucose levels, leading to the production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that also promote vascular inflammation. Moreover, IR is associated with dysregulated activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) that lead to dysfunction of the fibrinolytic system, as well as the development of autonomic neuropathy, which may promote myocardial systolic and diastolic dysfunction or life-threatening arrhythmias [

49,

51,

52].

3.4. Genetics

Apart from the environmental factors, the causal relationship between NAFLD and CVD depends on a genetic background with several genetic polymorphisms co-existing in both NAFLD and CVD patients[

53],[

54]. Of note, patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) and transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), are thought to have a protective effect regarding CVD risk, although positively related to NAFLD. In particular, PNPLA3 is a multifunctional enzyme that participates in lipid droplet remodeling and triglyceride metabolism [

55], while TM6SF2 regulates hepatic VLDL excretion [

56]. Robust data show that the PNPLA3 rs738409 polymorphism predisposes to NAFLD and is linked to an increased risk of developing NASH, advanced fibrosis, and cirrhosis [

57]. The TM6SF2 rs58542926 polymorphism has also been associated with NAFLD predisposition [

58]. On the other hand, an exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in more than 300,000 participants determined that these alleles seem to confer modest protection from CAD by lowering serum triglycerides and LDL cholesterol levels[

59]. However, to what extent these genetic modifications can also affect the development of other cardiovascular diseases is still under debate.

3.5. Gut Dysbiosis

Alterations in gut microbiota, referred as intestinal dysbiosis, have been linked to the development of NAFLD and several cardiometabolic diseases such as atherosclerosis and hypertension[

60,

61]. The gastrointestinal tract can be considered as a possible site of origin of systemic inflammation that may play a crucial role in the establishment and maintenance of metabolic diseases such as NAFLD and CVD. Gut dysbiosis is associated with an impairment in intestinal barrier function leading to increased mucosal barrier permeability to intestinal bacteria or microbial-derived products may, that in turn, induce a systemic inflammatory response [

45].

Secondary bile acids, trimethylamine (TMA), and short-chain fatty acids are a few of the described microbial-derived metabolites [

62], which, via modulation of energy balance and insulin sensitivity, but also through triggering adipose inflammation, may have an impact on NAFLD and CVD development. TMA N-oxide (TMAO), a TMA metabolite, also triggers platelet activation and its plasma levels are linked to thrombotic event risk[

63]. The introduction of gut microbiota with pro-inflammatory properties into Ldlr−/− female mice has been also shown to accelerate atherosclerosis and increase systemic inflammation [

64]. In this context, the use of statins, has been associated with a lower prevalence of gut microbiota dysbiosis, through the well-established anti-inflammatory effects of these drugs [

65].

In line with the aforementioned data, a variety of upcoming therapeutic options focus on targeting the gut-liver axis. Obeticholic acid is a synthetic variant of the natural bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid which acts as an agonist on the farnesoid X receptor in intestinal epithelial cells and hepatocytes, regulating bile acid, glucose, and lipid metabolism [

66]. In the FLINT clinical trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled study of 283 patients with NASH, an improvement in the hepatic histological parameters was shown in patients receiving obeticholic acid [

67]. However, the proportion of patients with resolution of NASH did not differ between obeticholic acid and placebo group. Obeticholic acid was also associated with increased total serum and LDL cholesterol and reduced HDL cholesterol, leading to an increased CVD risk profile.

3.6. Other potential mechanisms

Growing evidence suggest that the increase in epicardial adipose tissue can be considered as a potential cardiometabolic risk factor [

68]. NAFLD is associated with increased epicardial adipose tissue, and, simultaneously, a higher epicardial fat thickness is associated with more severe liver fibrosis, steatosis, and CVD prevalence in NAFLD patients [

69]. Under physiological conditions, epicardial fat supplies energy and heat to the myocardium and exerts an anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and anti-atherogenic cardioprotective role. A co-occurrence of increased epicardial fat thickness and other metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities convert epicardial fat into a highly lipotoxic, prothrombotic, profibrotic, and proinflammatory organ [

70], leading to the release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. leptin, TNF-a, IL-1, IL-6, and resistin), that in turn promote fibrosis and infiltration of the coronary intima wall layer with macrophages, and thus, accelerate atherosclerosis [

71]. Regarding liver tissue, the released pro-inflammatory cytokines may contribute to the activation of hepatic stellate cells and induce hepatic fibrosis.

Several pro- and anticoagulant factors are mainly produced in the liver. An increase in coagulation factor VIII, IX, XI, and XII activities has been described in NAFLD, proposing that hepatic fat accumulation can increase thrombotic risk[

72]. Likewise, plasminogen inhibitor activator 1 (PAI-1) serum levels are also positively related to liver fat content[

73].

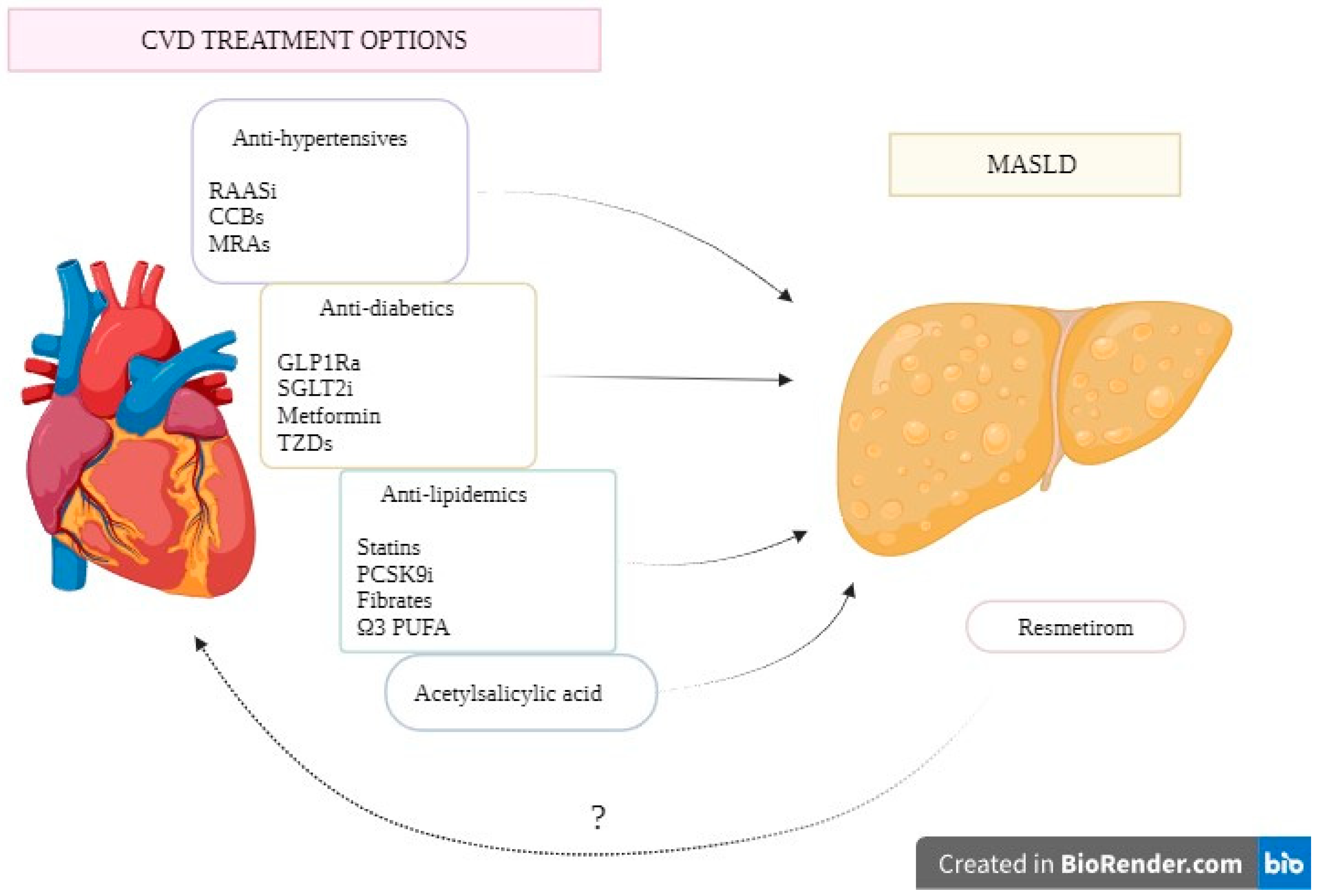

Figure 1 depicts the proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in the causal linkage between NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and CVD.

4. Cardiometabolic drugs and NAFLD/MASLD/MASLD

The strong association between CVD and MASLD emphasizes the need for early identification and adequate treatment of cardiometabolic risk factors. Current guidelines suggest that all patients with NAFLD should be screened regularly to detect the presence of additional cardiometabolic risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, or T2DM[

2]. Until recently, there were no specific pharmacological therapies for NAFLD/MASLD/MASLD, therefore optimal management of cardiometabolic risk factors implicated in the pathophysiology of the disease is crucial to reduce the cardiovascular risk of these patients. The recent approval of resmetirom, a thyroid hormone receptor b (THRb), opens new opportunities in the therapeutic management of MASLD [

74].

4.1. Anti-hypertensive drugs

Among NAFLD patients, the prevelence of arterial hypertension ranges from 40-70% and emerging data from prospective studies highlight the strong linkage between NAFLD and an increased risk of pre-hypertension (i.e. systolic blood pressure: 120–139 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure: 80–89 mmHg) and hypertension [

75,

76].

In spite of the significant correlation between MASLD and arterial hypertension, current evidence on the relative advantage of certain antihypertensive agents in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is insufficient. Therefore, antihypertensive management in patients with MASLD is conducted following current guidelines for arterial hypertension irrespective of this diagnosis.

4.1.1. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is a major contributor in the homeostasis of extracellular volume and blood pressure. Simultaneously, RAAS overactivity leads to a cascade of deleterious changes in the cardiovascular system promoting endothelial dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle cell and monocyte proliferation, pro-thrombotic effects, and IR [

77].

Currently, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs) are used in several CVD scenarios, such as in patients with hypertension, for secondary prevention after myocardial infarction, as well as for the management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and their cardiovascular benefit has already been well-established [

78,

79].

In preclinical mice studies, RAAS inhibitors have been shown to have a positive effect on liver fibrosis, fat deposition, and necroinflammation through variable mechanisms [

80,

81,

82]. Furthermore, telmisartan has been shown to work as a partial peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) agonist, influencing the expression of PPAR-γ target genes involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and reducing glucose, insulin, and triglyceride levels, thus reducing IR [

83].

In a pilot study of patients with NAFLD and chronic hepatitis C receiving telmisartan or olmesartan, an improvement in IR and transaminase levels was observed [

84]. Moreover, in a retrospective cohort study including more than 12,000 patients with NAFLD, treatment with ACEIs was correlated with a reduced risk of cirrhosis and liver cancer, even though this effect was not consistent with ARBs treatment [

85]. The effects of telmisartan or losartan for NAFLD treatment were studied in the FANTASY trial, which included 19 hypertensive patients with NAFLD. Although serum FFA levels were significantly reduced in the telmisartan compared to the losartan group, there was no significant improvement in liver function in either group [

86]. Furthermore, even though telmisartan has been shown to improve NAS and fibrosis score in patients with NASH [

87], a recent meta-analysis from Li et. al. failed to prove a statistically significant decrease in serum ALT levels (although demonstrating a decreasing trend) with neither improvement in fibrosis nor NAFLD scores with ARBs therapy [

88]. Therefore, the current evidence from clinical trials is insufficient to support the efficacy of RAAS inhibitors in NAFLD patients.

4.1.2. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs)

The harmful effects of aldosterone on the cardiovascular system have been previously well described, including sodium and fluid retention, myocardial fibrosis, and endothelial dysfunction [

89]. MRAs are currently used as second-line anti-hypertensive agents in patients with resistant hypertension [

90]. Furthermore, MRAs are part of the quadruple therapy for HFrEF that improves survival and reduces hospitalization for HF [

91]. Three landmark randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown the benefits of MRAs in decreasing morbidity and mortality among patients with reduced left ventricle (LV) ejection fraction (RALES trial, EPHESUS trial, EMPHASIS trial) [

92,

93,

94]. In heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HfpEF), MRAs have been shown to improve echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function [

95], with no reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular adverse effects [

96].

In experimental mice models, it has been shown that the expression of MR is associated with hepatic IR, liver inflammation and fibrosis development, while MR blockade with eplerenone induces anti-steatotic and anti-fibrotic effects [

97,

98]. Furthermore, reduced activation of hepatic MR seems to lead to beneficial downstream inhibition of lipogenesis [

99]. Unfortunately, data from clinical trials demonstrating possible beneficial effects of MR inhibition in patients with NAFLD are largely lacking. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (MIRAD trial) studying eplerenone’s effect on liver fat and metabolism in patients with T2DM did not show promising beneficial effects [

100]. A combination of spironolactone with vitamin E, on the other hand, appeared to have a positive effect on serum insulin levels and HOMA-IR in NAFLD patients [

101]. Moreover, Polyzos et al., in their 52-week randomized controlled trial including 23 women with NAFLD, compared the effects of combined low-dose spironolactone plus vitamin E vs vitamin E monotherapy on NAFLD. They showed that NAFLD liver fat score, insulin levels and HOMA-IR declined significantly only in the combination treatment group [

102]. Overall, the role of MRAs in NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD treatment is still under debate.

4.1.3. Calcium Channel Blockers

Calcium channel blockers are currently one of the first options in the management of arterial hypertension [

103].

In a recent preclinical study by Li et. al., it was shown that, in mice with NAFLD and hypertension, amlodipine, via modulation of gut microbiota, ameliorates liver injury and steatosis, while improving lipid metabolism through a reduction in the expression of lipogenic genes [

104]. Likewise, the use of amlodipine in spontaneously hypertensive rats with steatohepatitis improved IR and cytokine profile of IL-6 and IL-10, suggesting that amlodipine could be beneficial for patients with metabolic syndrome and NASH [

105]. However, there is a lack of clinical data determining if calcium channel blockers are effective for the prevention of CVD in patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD.

4.1.4. Beta Blockers

The maladaptive activation of SNS is implicated in the pathophysiology of several cardiovascular diseases (e.g., heart failure [

106]). Beta-blockers exert their cardioprotective effects through several mechanisms (e.g., anti-inotropic, anti-chronotropic action), rendering them crucial therapeutic choices in patients with CVD. Up to date, they are used for the relief of angina pectoris symptoms, as antihypertensive drugs in selected patients, after acute coronary syndromes, and in combination with RAS inhibitors, MRAs, and SGLT2i in HFrEF [

91,

107,

108,

109].

In a preclinical NASH rat model, propranolol was shown to worsen liver injury via activation of apoptotic pathways, suggesting that beta-blockers should be avoided or used with extreme caution in patients with MASH [

110]. Studies evaluating the effect of this drug category in humans have yet not been conducted.

4.2. Glucose Lowering Medications

Given the close relationship between IR, NAFLD and CVD, it is not a surprise that fifty percent of all NAFLD patients have T2DM, while the prevalence of NAFLD is higher in individuals with prediabetes [

111]. Furthermore, T2DM is closely associated with the severity of NAFLD and promotes the development of NASH, advanced fibrosis, and HCC [

112,

113]. Conversely, patients with U/S-defined MASLD have a 2-5-fold increased risk of subsequent incident T2DM [

114]. Therefore, diabetic patients should be assessed for possible NAFLD, and vice versa, screening and surveillance for T2DM should be done in patients with NAFLD [

2].

4.2.1. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1RAs)

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a polypeptide secreted by intestinal L-cells after meal digestion. GLP1-RAs act by enhancing glucose-mediated insulin release and suppressing glucose-mediated glucagon secretion in pancreatic tissue [

115]. GLP-1RAs are used in clinical practice as antidiabetic drugs. Furthermore, the ability of these drugs to reduce appetite acting as central anorexigens and delaying gastric emptying makes them suitable for weight reduction in obese patients in whom non-pharmacologic interventions have failed to reduce body weight [

116].

GLP-1RAs have demonstrated unique properties beyond glucose metabolism regulation, exerting cardioprotective and vasodilatory effects [

117]. The cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1RAs have been shown in several RCTs among patients with T2DM and high cardiovascular risk [

118,

119,

120,

121]. Recently, semaglutide, a drug of this category showed a reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight or obese patients without T2DM [

122].

In hepatic cells, through the activation of AMP kinase, GLP1-RAs reduce liver lipogenesis [

123]. In vitro, they have been shown to decrease triglyceride stores and steatosis in human hepatocytes via modulation of insulin signaling pathways, as well as hepatic inflammation, via reducing fat-derived oxidants [

124,

125].

Data from clinical studies demonstrate a positive effect of GLP-1RAs in patients with MASLD [

126]. Most trials have shown an improvement in serum aminotransferases, liver steatosis, and MASH, with an ability to even reduce hepatic fibrosis in some of them [

127,

128,

129].

A promising meta-analysis of eleven placebo-controlled or active-controlled phase-2 RCTs (Mantovani et al) demonstrated that treatment with GLP1-RAs (exenatide, semaglutide, liraglutide, dulaglutide) in patients with NAFLD, was correlated with a reduction in serum liver enzyme levels and absolute percentage of liver fat content on magnetic resonance-based techniques and a histological resolution of NASH without worsening of liver fibrosis. However, improvement in the liver fibrosis stage was not observed in either of these trials [

130].

Of note, an ongoing paired-biopsy phase 3 clinical trial (NCT04822181) with 1,200 participants with NASH and significant fibrosis (stages F2–F3) receiving semaglutide 2.4 mg/week or placebo for 72 weeks is being conducted.

GLP-1RAs, therefore, could be considered a drug of choice for patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD, especially in obese patients with T2DM and NASH/MASH. It’s worth noting that, until now, data regarding the use of GLP-1RAs in NASH/MASH patients with no T2DM are scarce.

4.2.2. Dual glucagon-like peptide-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (glp-1/gip) receptor agonist

Tirzepatide is a novel dual GLP1-GIP receptor agonist that has been recently shown to induce substantial and sustained body weight loss in overweight patients with or without diabetes mellitus (SURMOUNT TRIALS) [

131,

132]. In May 2022, tirzepatide received FDA approval to improve glycemic control in adults with T2DM [

133].

The cardiovascular outcomes of tirzepatide in patients with T2DM and increased CV risk are currently being studied in the SURPASS-CVOT trial [

134], while the drug’s potential cardiovascular benefits in overweight or obese patients with established CV disease but without diabetes mellitus are being evaluated in the SURMOUNT-MMO trial.

In SURPASS-3 MRI, a substudy of the SURPASS-3 trial, tirzepatide promoted a significant reduction in liver fat content (LFC) and visceral adipose tissue compared with insulin degludec [

135]. In a proof-of-concept trial, studying tirzepatide's effect on NASH activity and fibrosis biomarkers in patients with T2DM, higher tirzepatide doses significantly increased adiponectin levels and reduced NASH-related biomarkers [

136]. Given these biomarker effects, the ongoing SYNERGY-NASH trial aims to demonstrate the clinical effect of tirzepatide by measuring NASH resolution and lack of fibrosis progression. In summary, the effects of tirzepatide with its dual mechanism of action, and the upcoming triple agonists (GLP-1/GIP/glucagon receptor triagonist) with greater outcomes on weight loss have the potential to outperform the known effects of single GLP-1Ras and become an alluring treatment option for NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD or NASH/MASH, especially for patients with coexisting diabetes or obesity.

4.2.3. Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 Inhibitors (SGLT-2i)

Sodium glucose transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) were initially designed as antidiabetic drugs for patients with T2D, acting on the sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 protein expressed in the renal proximal convoluted tubules of the nephron, leading to reduction of reabsorption of filtered glucose and thus, improving glycemic control [

137,

138]. Furthermore, through the stimulation of the SIRT1/AMPK signaling pathway and the downregulation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, SGLT-2i can trigger a variety of glucose-independent beneficial effects: amelioration of oxidative stress, reduction of inflammation, normalization of mitochondrial structure and function, minimization of coronary microvascular injury, improvement of contractile performance, and suppression of the development of cardiomyopathy. In the nephrons, a reduction of glomerular and tubular inflammation is observed, diminishing the development of nephropathy [

139]. Clinically, SGLT2i cardiovascular benefit has been proven in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and T2DM, rendering them a first-choice therapeutic approach for this subgroup of patients [

140]. Recently, SGLT-2i have become part of the standard of care in patients with HFrEF, with clear beneficial effects in reducing the risk for CV death or hospitalization for heart failure, even in patients without T2DM [

91], while EMPEROR-PRESERVED trial has demonstrated their efficacy in CV risk reduction in patients with HFpEF [

141].

In experimental animal models, SGLT-2i have been reported to restrict the development of NAFLD and ameliorate histological hepatic steatosis or steatohepatitis in both weight-dependent and independent ways. They also reduce serum liver enzymes, hepatic collagen deposition, and inflammatory cytokine expression [

142,

143,

144].

Several clinical studies highlight the beneficial effects of SGLT-2i in patients with T2DM and NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD. In RCTs using as a primary outcome MRI-measured changes in liver triglyceride content, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to reduce liver steatosis [

145,

146,

147].

In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial, which included pooled data from 4 placebo-controlled trials (n = 2,477) and a trial of empagliflozin versus glimepiride, empagliflozin was shown to significantly reduce aminotransferase levels in patients with T2DM [

148]. A meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled trials of a total of 573 participants with T2DM and NAFLD supports that SGLT2 inhibitors are superior over other antihyperglycemic drugs used in these RCTs in improving serum aminotransferases levels, hepatic fibrosis and lowering liver fat and body weight [

149]. However, data in non-diabetic patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD are lacking. There is only a small single-center study comparing 12 patients under dapagliflozin and 10 patients under teneligliptin, a DPP4 inhibitor, that showed that after an intervention period of 12 weeks, serum transaminases were reduced in both groups, while in the dapagliflozin group, total body water and body fat also decreased, leading to decreased total body weight [

150].

Proposed pathophysiologic mechanisms that may lead to NAFLD improvement under SGLT-2i treatment include reduced glucose and insulin levels, which in turn, lead to reduced de novo endohepatic lipid synthesis and increased glucagon secretion from alpha pancreatic cells that also express SGLT-2. Moreover, hepatic β-oxidation is stimulated by the elevated serum glucagon levels, and an anti-oxidant environment is established through decrease of high glucose-induced oxidative stress, reduction of free radical generation, and upregulation of antioxidant systems [

151].

4.2.4. Metformin

Metformin, an AMPK agonist, exerts its actions by improving insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues and regulating glucose utilization by the hepatic cells [

152]. Due to its high efficacy in reducing blood glucose levels and improving insulin sensitivity, as well its well-established safety, metformin is a first-line medical treatment in T2DM patients [

152]. Apart from its glucose-lowering effect, metformin exerts pleiotropic actions in several cardiovascular parameters, including dyslipidemia, systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and atherosclerosis [

153].

A recent meta-analysis of 16 studies, including 701,843 participants of T2DM, treated with metformin, and 1,160,254 controls, demonstrated a reduced mortality risk [OR=0.44 (0.34–0.57)] and adverse cardiovascular events [OR=0.73 (0.59–0.90)] with metformin [

154]. Furthermore, an ongoing trial (the “MetCool ACS” trial) is going to evaluate the effectiveness of metformin in reducing the risk of an unscheduled PCI or CABG after successful revascularization due to ACS within a 30-month follow-up period in patients without diabetes. Additionally, a meta-analysis of nine RCTs (754 patients) suggested a favorable effect of metformin concerning left ventricular mass index (LVMI) and LVEF in patients with or without preexisting CVD [

155].

As expected, the efficacy of metformin in NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD has been thoroughly investigated, both in patients with T2DM and non-diabetic individuals. Although it has been shown, in some trials. that the use of metformin ameliorates serum transaminases and hepatic steatosis [

156,

157], two recent major meta-analyses failed to demonstrate the beneficial effect of metformin in improving hepatic biochemical or histological parameters of patients with NAFLD [

158,

159]. Due to the discrepancy in existent data, metformin is not recommended as a specific NAFLD treatment in current guidelines from international societies 2.

4.2.5. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs)

TZDs are potent PPAR-γ agonists that improve IR, a hallmark of T2DM, NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD, and CVD [

160]. They have been used as antidiabetic agents, but their adverse effects have rendered them a backup choice in patients with T2DM [

160].

Apart from its glucose-lowering effects, in large clinical trials, pioglitazone seems to retard the atherosclerotic process and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events [

161,

162,

163]. A meta-analysis of 19 trials with a total of 16,390 patients with T2DΜ receiving either pioglitazone or placebo showed that the use of pioglitazone was associated with a reduced primary composite endpoint (death, myocardial infarction or stroke) (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72-0.94). However, serious heart failure events were more prominent in the pioglitazone group (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.14-1.76), without an increase in mortality [

164]. On the contrary, a meta-analysis of several small studies suggested an association of rosiglitazone with MI and an overall trend toward death from CV causes [

165]. Therefore, rosiglitazone has been subsequently reserved from the market.

Animal studies have demonstrated improvement in various aspects of NAFLD such as improvement of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis and suppression of inflammation [

166,

167].

Additionally, several clinical trials demonstrate that treatment with TZDs and especially pioglitazone, can lead to an improvement in hepatic biochemical and histologic parameters in patients with NASH [

168,

169,

170]. In a randomized control clinical trial of 247 NASH patients without T2DM receiving either pioglitazone (80 patients), or Vitamin E (84 patients), or placebo (83 patients), the use of pioglitazone was associated with statistically significant reduction in plasma alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels, hepatic steatosis and lobular inflammation when compared to placebo group, but without improvement in fibrosis scores [

171]. A meta-analysis of four randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials using pioglitazone or rosiglitazone versus placebo in the treatment of 344 patients with NASH showed that TZDs were more likely to improve ballooning degeneration (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3-3.4), lobular inflammation (OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.7-4.0), steatosis (OR 3.4, 95% CI 2.2-5.3) and necroinflammation (OR 6.52, 95% CI, 3.03-14.06). Moreover, an improvement in fibrosis was observed in patients treated with pioglitazone compared with placebo (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0-2.8) [

172]. In another meta-analysis of 8 RCTs with 516 patients with biopsy-proven NASH, pioglitazone therapy was associated with an improvement in advanced fibrosis (OR, 3.15; 95% CI, 1.25-7.93;), fibrosis of any stage (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.12-2.47) and NASH resolution (OR, 3.22; 95% CI, 2.17-4.7). Results were similar in patients without diabetes [

173].

As a result, pioglitazone, together with vitamin E, is currently recommended for the treatment of MASLD with significant fibrosis.

4.3. Lipid-lowering Drugs

4.3.1. Statins

Statins are currently the most frequently used antilipidemic drug for primary and secondary prevention of CVD, as the reduction of pro-atherogenic LDL cholesterol with statin therapy lowers the risk of major coronary events, coronary revascularization, ischemic stroke, and all-cause mortality [

174].Via inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, statins curtail cholesterol formation by targeting a key step in the biosynthesis of sterols and promoting lipoprotein clearance, primarily by upregulating low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) expression [

175].

Beyond cholesterol-lowering effects, statins exert pleiotropic anti-inflammatory, proapoptotic, anti-oxidative, and anti-fibrotic properties, which may prove beneficial for the improvement of NAFLD/NASH [

176]. This has already been proven in animal studies, where statins show reduction of inflammation, fibrosis, hepatic stellate cells activation, and sinusoidal endothelial cell dysfunction [

177,

178,

179].

To date, there are no RCTs evaluating the role of statins in NASH. Data from post hoc analyses of prospective studies demonstrate a beneficial trend of statin use on NASH. A post hoc analysis of the GREACE study, highlighted statin safety, statin-induced improvement of liver tests, and reduction of cardiovascular risk in patients with established coronary heart disease and mild-to-moderately abnormal liver tests potentially attributable to NAFLD [

180]. Another post hoc analysis of IDEAL study proved greater cardiovascular benefit of intensive statin therapy in contrast to moderate treatment strategy in patients with established cardiovascular disease and moderately elevated aminotransferase levels, emphasizing that moderate elevations in liver enzyme levels should not present a barrier to prescribing statins, even at higher doses, in high-risk patients [

181]. In the post hoc analysis of the ATTEMPT study which evaluated 1,123 participants with metabolic syndrome without diabetes or CVD, liver enzymes and ultrasonography improved during the study with the use of statins [

182]. Furthermore, improvement of hepatic steatosis has been observed in uncontrolled investigations using ultrasonography and tomography [

183,

184]. A histopathological follow-up study in patients with NAFLD also revealed a significant reduction of liver steatosis with statins use [

185]. A meta-analysis of 14 RCTs has highlighted the statins’ effect to significantly reduce liver biochemical indicators in patients with NAFLD [

186]. Moreover, statin use has been associated with a reduced risk of HCC development [

187].

In December 2022, Ibrahim Ayada et al. published the results of a multidimensional study comprising a cross-sectional investigation in an ongoing general population cohort (the ROTTERDAM STUDY) and a NAFLD patient cohort (the PERSONS cohort), a meta-analysis, and an experimental exploration. In the analysis of 4,576 participants of the Rotterdam study, the use of statins in patients with dyslipidemia was inversely associated with NAFLD compared to participants with untreated dyslipidemia (OR: 0.72, 95%, CI: 0.59–0.86). In the PERSONS cohort, an analysis of 569 patients with biopsy-proven NASH showed that statin use was inversely associated with MASH (OR: 0.55, 95%, CI: 0.32–0.95), but not with fibrosis (OR: 0.86, 95%, CI: 0.44–1.68). The meta-analysis of 6 studies revealed a not significant inverse association of statin use with steatosis (pooled OR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.46–1.01), a significant inverse association with NASH (pooled OR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.44–0.79) and a significant inverse association with fibrosis (pooled OR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.33–0.70). Lastly, experimental exploration in a fatty liver model of primary human liver organoids highlighted the hepatoprotective properties of statins, by amelioration of intrahepatic lipid droplets accumulation and suppression of the expression of pro-inflammatory genes in macrophages [

188].

Currently, STAT NASH (NCT04679376), a double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT is being conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of atorvastatin in improving NASH features (improvement of NASH with no worsening of fibrosis or improvement of fibrosis with no worsening of NASH) in 70 adult patients with NASH.

In summary, although a beneficial trend of statins’ use in NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD has been observed, stronger evidence from RCTs evaluating their possible positive effects in NASH/MASH patients are needed for definitive NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD recommendations.

4.3.2. Ezetimibe

Ezetimibe is an antilipidemic drug that lowers serum LDL levels via inhibition of Niemann Pick C1-like 1 protein (NPC1L1) expressed at the enterocyte/ gut lumen (apical) as well as the hepatobiliary (canalicular) interface, thus reducing intestinal and biliary cholesterol absorption [

189]. When added to statins, ezetimibe reduces LDL cholesterol levels by an additional 23 to 24%, on average. In IMPROVE-IT trial, combination of ezetimibe with statin reduced the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) compared with statin monotherapy [

190]. Therefore, ezetimibe is currently used either in combination with statins in patients in whom statin monotherapy has failed to achieve the target LDL-levels (according to individualized CV risk) or as monotherapy in patients with statin intolerance [

191].

In experimental animal models, ezetimibe has been shown to ameliorate NAFLD by improving liver steatosis and reducing IR [

192,

193]. Similar beneficial results have been observed in small-numbered human uncontrolled trials [

194,

195]. However, there is a lack of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, proving the beneficial effect of ezetimibe in NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD. An open-label randomized clinical trial (Takeshita et al) demonstrated that treatment with 10mg of ezetimibe for 6 months significantly reduced serum total cholesterol, fibrosis staging, and ballooning score, with no statistically significant effect on serum aminotransferases levels and hepatic steatosis. Using hepatic gene expression analysis, researchers suggested that amelioration of fibrosis might be regulated by the downregulation of genes involved in skeletal muscle development and cell adhesion molecules, thus suppressing stellate cell development into myofibroblasts. However, treatment with ezetimibe significantly deteriorated glycaemic control; a critical risk factor for NAFLD development and progression [

196]. MOZART trial, which assessed the efficacy of ezetimibe treatment in MASH patients by the magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density-fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) and liver histology, failed to show statistically significant reduction in liver fat content and serum aminotransferases levels [

197]. Likewise, no improvement in liver steatosis was found in a meta-analysis by Lee and colleagues, despite the decrease in NAFLD activity score [

198]. In the ESSENTIAL study, a, open-label randomized trial of 70 NAFLD patients assigned to receive either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks, the combined ezetimibe plus rosuvastatin treatment significantly reduced liver fat measured by MRI-PDFF compared to single rosuvastatin therapy [

199]. Overall, ezetimibe therapy is still controversial in patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and more studies are required to establish its efficacy.

4.3.3. PCSK9 inhibitors

Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9i) are a novel therapeutic option for very high-risk cardiovascular patients who either cannot achieve LDL goal with statin-ezetimibe combination therapy or cannot tolerate statin therapy due to side effects [

191].

PCSK9 binds to the LDL receptor leading it to lysosomal degradation inside hepatocytes, thus reducing LDLR-mediated LDL reabsorption from circulation [

200].

In the landmark FOURIER and ODYSSEY RCTs, the PCSK9i antibodies evolocumab and alirocumab were shown to reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with established ASCVD and under statin therapy by effectively lowering LDL cholesterol levels [

201,

202].

Animal and clinical studies have demonstrated that high intrahepatic or circulating PCSK9 levels augment hepatic fatty acids and triglyceride storage, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of NAFLD [

203].

Although there is limited data from clinical trials using PCSK9i as a therapeutic option for NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD, their results indicate a potential reduction in liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis with a possible benefit on cardiovascular risk. A randomized study of 40 patients with heterozygous familial hyperlipidemia demonstrated complete amelioration of previously diagnosed NAFLD after one year of treatment with a PCSK9i, with improvement in liver structure and a further reduction in CV risk [

204]. Moreover, in a retrospective, chart review-based study, 8 of 11 patients with a radiologic diagnosis of NAFLD treated with PCSK9i for any reason reached complete radiological resolution of NAFLD with a statistically significant reduction in serum ALT levels [

205].

4.3.4. Other Hypolipidemic Agents

Fibrates activate the PPAR-α and are generally effective in lowering triglycerides and cholesterol levels [

206]. Several RCTs have been conducted to evaluate the CV benefit of fibrates, with their efficacy confined in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (>500 mg/dl) as a statin add-on therapy [

191]. Regarding NAFLD, preclinical animal studies have demonstrated the positive effect of fibrates in ameliorating both hepatic steatosis and necroinflammation in NAFLD or NASH experimental animals [

207,

208,

209,

210]. However, clinical-based research studies investigating the possible therapeutic benefit of fibrates in treating NAFLD/NASH are limited. Fabbrini et al. study failed to show any alteration in intrahepatic triglyceride content in obese NAFLD patients treated either with fenofibrate or niacin [

211]. Yaghoubi et al, on the contrary, demonstrated that fenofibrate significantly reduced serum transaminase levels, blood pressure, and BMI in 30 NAFLD patients [

212]. More clinical studies are therefore needed to establish the therapeutic effects of fibrates in NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD treatment.

Ω-3 fatty acids [eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)] are currently considered an effective add-on therapy to statins in high CV risk patients with elevated triglycerides levels despite statin treatment, in order to reduce the risk of ischemic CV events [

213]. Clinical data also support the beneficial effects of ω-3 fatty acid supplementation in the decrease of hepatic steatosis in NAFLD patients, rendering them as a promising pharmacologic agent for management of NAFLD [

214]; however, these data come mainly from small, non-randomized trials, so more studies are needed before safe consumptions can be made.

4.4. THR-β agonists- Resmetirom

Thyroid hormone receptor alpha (THR-α) and beta (THR-β) are the main mediators of thyroid hormones effects into peripheral tissues. THR-β is the dominant receptor isoform in liver cells and regulates several metabolic pathways. The THR-β role is crucial in increasing fatty acid β-oxidation and lowering serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels by reducing the secretion of VLDL and upregulating expression of the LDLR in the hepatocytes [

74]. However, THR-β hepatic signaling in patients with NASH is impaired, potentially worsening NASH and liver fibrosis [

215].

Resmetirom, a liver-targeted THR-β selective agonist, showing promising results in the improvement of hepatic fibrosis and MASH resolution, has recently received FDA approval for non-cirrhotic MASH patients with moderate to advanced fibrosis, along with dietary and exercise interventions [

74]. The resmetirom-MASH development program includes four ongoing phase 3 clinical trials: MAESTRO-NASH, MAESTRO-NAFLD-1, MAESTRO-NAFLD-OLE, and MAESTRO-NASH-OUTCOMES. Results were recently published from the MAESTRO-NASH trial. In the MAESTRO-NASH trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial, of 966 patients with biopsy-proven NASH and moderate or advanced liver fibrosis, NASH resolution with no worsening of fibrosis was observed in a statistically significant higher number of patients in resmetirom group when compared with the placebo one. Furthermore, the other primary endpoint of the trial, an improvement in fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of the NAFLD activity score was also achieved in significantly more patients in the resmetirom group [

216]. Limitations of this study include the lack of clinical-outcomes data to correlate with histologic data and the unassessed long-term safety of resmetirom.

Another very interesting finding from the resmetirom trials, comes from the MAESTRO-NAFLD trial where resmetirom was shown to significantly lower atherogenic lipids/lipoproteins that contribute to increased CV risk, such apoCIII, Lp(a), and VLDL cholesterol when compared to placebo [

217]. Similar results were also observed in the MAESTRO-NASH trial [

216].

4.5. Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA)

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) irreversibly inhibits the cyclo-oxygenase 1 (COX1) enzyme, exerting anti-thrombotic effects via suppressing thromboxane A2 formation, a molecule that activates platelets and promotes vasoconstriction. ASA is used for secondary prevention in all patients with established atherosclerotic CVD including chronic coronary disease, previous myocardial infarction, previous ischemic stroke, and peripheral arterial disease [

218].

An in vitro and in vivo study has recently shown that aspirin administration in dyslipidemic conditions can simultaneously ameliorate nonalcoholic fatty liver and atherosclerosis, through elevation of catabolic metabolism, inhibition of lipid synthesis, and suppression of inflammation, effects mediated from sequential regulation of the PPARδ-p-AMPK-PGC-1α oxidative phosphorylation pathway [

219].

In a prospective cohort study of 361 patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD, administration of ASA on a daily basis was correlated with less severe histologic features of NAFLD/NASH, and reduced risk of progression to advanced fibrosis, especially after 4 years of aspirin use [

220].

Additionally, daily aspirin therapy was significantly associated with a decreased risk for HCC in NAFLD patients in a population-based cohort study [

221]. Recently, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial with 80 non-cirrhotic MASLD patients tested as a primary endpoint whether aspirin use could reduce liver fat content. Researchers observed that a 6-month daily low-dose aspirin significantly reduced hepatic fat quantity measured by magnetic resonance imaging proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) compared with placebo [

222].

The latest clinical data suggest an underlying hepatoprotective effect of ASA on NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD. Although this assumption needs further clarification, it seems to be an interesting approach, which can also prove beneficial in patients already requiring ASA for secondary cardiovascular protection.

Figure 2.

Potential CVD treatment options as therapeutic targets for MASLD. Abbreviations: MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; RAASi: Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone system inhibitors; CCBs: Calcium Channel Blockers; MRAs: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists; GLP-1RAs: Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists; SGLT-2i: Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 Inhibitors; TZDs: Thiazolidinediones; PCSK9i: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors; PUFA: Polyunsaturated fatty acid .

Figure 2.

Potential CVD treatment options as therapeutic targets for MASLD. Abbreviations: MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; RAASi: Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone system inhibitors; CCBs: Calcium Channel Blockers; MRAs: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists; GLP-1RAs: Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists; SGLT-2i: Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 Inhibitors; TZDs: Thiazolidinediones; PCSK9i: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors; PUFA: Polyunsaturated fatty acid .

Table 2.

Summary of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for cardiometabolic conditions on the reduction of hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis and cardiovascular risk. Abbreviations: ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; ARBs: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1; GIP: glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; PCSK9i: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

Table 2.

Summary of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for cardiometabolic conditions on the reduction of hepatic steatosis, steatohepatitis, hepatic fibrosis and cardiovascular risk. Abbreviations: ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; ARBs: Angiotensin Receptor Blockers; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; GLP-1: glucagon-like peptide-1; GIP: glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide; PCSK9i: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors.

| Drug Category |

Drug |

Hepatic steatosis |

Steatohepatitis |

Hepatic fibrosis |

Cardiovascular (CV) risk |

Notes |

| ANTI-HYPERTENSIVES |

RAAS Inhibitors (ACE Inhibitors, ARBs) |

Limited evidence |

Limited evidence |

Limited evidence |

Reduce CV risk

(used in patients with HTN, HFrEF, post MI) |

Preclinical studies suggest potential liver benefits.

Clinical data are insufficient, with inconsistent effects on fibrosis and MASLD scores. |

| Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists |

Limited evidence |

Limited evidence |

Limited evidence |

Reduce CV risk in specific conditions (e.g., HFrEF) |

Potential benefit in MASLD liver fat score when combined with vitamin E

|

|

Calcium Channel Blockers

|

Limited evidence |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

Neutral or reduce CV risk.

Commonly used for arterial hypertension management. |

Animal studies suggest liver benefits; lack of clinical data.

|

|

Beta Blockers

|

Not effective; may worsen |

Not effective; may worsen |

No evidence |

Reduce CV risk in certain conditions (e.g., heart failure and post-myocardial infarction) |

Preclinical data suggest potential worsening of liver injury in NASH/MASH.

|

| GLUCOSE LOWERING DRUGS |

GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

|

Effective |

Effective |

Some evidence |

Reduce CV risk in high-risk patients with T2DM or obesity. |

Most clinical trials show improvement in liver enzymes, steatosis, and MASH resolution

Some clinical trials also show improvement in hepatic fibrosis

Data in MASH patients without T2DM are scarce

|

| |

SGLT-2 Inhibitors

|

Effective |

Some evidence |

Some evidence |

Proven cardiovascular benefits, including reduction in heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality in HFrEF patients. |

Limited data in non-diabetic MASLD

|

|

Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonist

|

Limited evidence |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

Potential to reduce cardiovascular risk |

Ongoing trials are evaluating effects on MASH, fibrosis, and cardiovascular outcomes.

|

|

Metformin

|

Not effective |

Not effective |

Not effective |

May reduce CV risk in T2DM |

Recent meta-analyses do not support liver benefits

Not recommended as a specific MASLD treatment.

|

|

Thiazolidinediones

|

Effective |

Effective |

Effective |

Mixed cardiovascular effects.

May reduce CV risk in T2DM patients but can increase risk of heart failure. |

Recommended in combination with Vitamin E for the treatment of MASH with significant fibrosis

|

| LIPID LOWERING DRUGS |

Statins

|

Some evidence |

Some evidence |

Some evidence |

Reduce CV risk |

Generally safe in MASLD, with studies showing reduced CVD risk without worsening liver injury

|

|

Ezetimibe

|

Conflicting evidence |

Conflicting evidence |

Conflicting evidence |

Reduce CV risk when combined with statins |

May worsen glycemic control in some patients.

Used to further lower LDL cholesterol levels when statins are insufficient.

|

|

PCSK9 inhibitors

|

Limited evidence |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

Reduce CV events in high-risk patients when added to statin therapy |

Further studies needed for MASLD benefits.

|

|

Fibrates

|

Limited evidence |

Limited evidence |

Insufficient data |

Benefit in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia when combined with statins |

Preclinical studies suggest potential liver benefits.

Clinical data are insufficient

Used primarily to lower triglyceride levels in severe hypertriglyceridemia.

|

|

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

|

Some evidence |

Insufficient data |

Insufficient data |

May reduce cardiovascular risk |

Data mainly from small, non-randomized trials |

| OTHERS |

Acetylsalicylic Acid

|

Some evidence |

Some evidence |

Some evidence |

Reduce CV risk |

Studies suggest benefits in hepatic fat reduction and histological features

Further trials needed for definitive MASLD recommendations

Standard therapy for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.

|

5. Conclusion

In summary, NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD is independently associated with CVD occurrence, therefore the CVD risk of patients with NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD seems to be increased from disease’s early stages. Special consideration should be made for patients with MASH or advanced fibrosis (F3-F4) as well as NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD patients with concomitant T2DM, as these patients show an even higher CVD risk. The precise pathophysiological mechanisms linking NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD with CVD are yet to be fully elucidated. Current evidence suggests an important role of common risk factors, including dyslipidemia, IR, systemic inflammation, coagulopathies, ectopic adipose tissue deposition, perturbations in the gut microbiome, as well as a genetic substrate. With a diagnosis of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD, a thorough cardiovascular risk assessment and evaluation for subclinical atherosclerosis should be considered, to identify high-risk patients that are candidates for therapeutic interventions which alleviate the cardiometabolic risk factor burden. Lifestyle modifications including weight loss, augmented physical activity and suitable nutrition, e.g. Mediterranean/low-carbohydrate diet, although not discussed on this review, remain the cornerstone of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD management. Pharmacologic interventions with drugs targeting common modifiable cardiometabolic risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and T2DM is a reasonable strategy to prevent CVD development and progression of MASLD. Recently, a novel drug for MASH, resmetirom, has shown positive effects regarding CVD risk, opening new opportunities for the therapeutic approach of NAFLD/MAFLD/MASLD and CVD.

Author Contributions

E.K. conceived and designed the manuscript. M.Z. collected the data and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of M.C. and T.A.All authors critically review and comment on the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

NAFLD: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; MAFLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease; NASH: nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; MASH: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TLRs: toll-like receptors; IL: interleukin; IR: Insulin Resistance; DNL: de novo lipogenesis; KLF4: Krüppel-like factor 4; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; EVs: extracellular vesicles; miR-1: microRNA-1; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; FetA: Fetuin-A; SREBP-1c: sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c; ChREBP: carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein; ICAM-1: intracellular adhesion molecule 1; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; NO: nitric oxide; AGEs: advanced glycation end products; PAI-1: plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; PNPLA3: patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3; TM6SF2: transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2; TMA: trimethylamine; PPAR-γ: partial peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HfpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; GLP-1RAs: Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists; SGLT-2i: Sodium Glucose Transporter-2 Inhibitors; TZDs: Thiazolidinediones; RAASi: Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone system inhibitors; CCBs: Calcium Channel Blockers; MRAs: Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists;NPC1L1: Niemann Pick C1-like 1, PCSK9i: Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors; EPA: eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; THR-α: Thyroid hormone receptor alpha; THR-β: Thyroid hormone receptor beta.

References

- Chalasani, N.; et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016, 64, 1388–402. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteoni, C.A.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999, 116, 1413–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, T.; et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Disease Spectrum. Annu Rev Pathol 2016, 11, 451–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, S.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr Disord 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flessa, C.-M.; et al. Genetic and Diet-Induced Animal Models for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri-Ansari, N.; et al. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): A Concise Review. Cells 2022, 11, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Santillán, R.; et al. Hepatic manifestations of metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, L.A.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and its relationship with cardiovascular disease and other extrahepatic diseases. Gut 2017, 66, 1138–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.; Grobbee, D.E.; Dendale, P. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a new and growing risk indicator for cardiovascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020, 27, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 6, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with major adverse cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 33386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; et al. Association of NAFLD with cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: a large-scale prospective cohort study based on UK Biobank. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2022, 13, 20406223221122478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Y.; et al. Synergistic increase in cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 30, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.S.; et al. Association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with cardiovascular disease and all cause death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: nationwide population based study. Bmj 2024, 384, e076388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abosheaishaa, H.; et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2024, 18, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 11124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, E.P.; et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Heart: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019, 73, 948–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; et al. Liver lipid metabolism. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 2008, 92, 272–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsen, D.H., J. Lykkesfeldt, and P. Tveden-Nyborg, Molecular mechanisms of hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018, 75, 3313–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francque, S.M.; van der Graaff, D.; Kwanten, W.J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular risk: Pathophysiological mechanisms and implications. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 425–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ference, B.A.; et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J 2017, 38, 2459–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, M.; et al. The significance of low-density-lipoproteins size in vascular diseases. Int Angiol 2006, 25, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zewinger, S.; et al. Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latz, E.; Xiao, S.; Stutz, A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nat Rev Immunol 2013, 13, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, M.S.; et al. Dietary interesterified fat enriched with palmitic acid induces atherosclerosis by impairing macrophage cholesterol efflux and eliciting inflammation. J Nutr Biochem 2016, 32, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.; et al. Triggering and resolution of inflammation in NASH. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoner, L.; et al. Inflammatory biomarkers for predicting cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem 2013, 46, 1353–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; et al. Hepatocyte-derived extracellular vesicles promote endothelial inflammation and atherogenesis via microRNA-1. J Hepatol 2020, 72, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braza-Boïls, A.; et al. Deregulated hepatic microRNAs underlie the association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease. Liver Int 2016, 36, 1221–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacana, T.; et al. Dysregulated Hepatic Methionine Metabolism Drives Homocysteine Elevation in Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0136822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; et al. Plasma levels of homocysteine and cysteine increased in pediatric NAFLD and strongly correlated with severity of liver damage. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 21202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]