1. Introduction

In recent years, the research of deep neural network models has witnessed significant progress as various large language models are proposed and evolved at a fast pace. However, currently, these models still cannot achieve reasonable performance in logical and mathematical reasoning without much human intervention, although more than 10 billion trainable parameters are placed in their latest neural networks. The failure of these sophisticated models in some seemingly simple math problems inspired us to propose a non-Turing computer structure to address this challenge. The number of previous works on non-Turing machines is relatively small ([

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]), which mostly discuss it conceptually and psychologically without giving any specific workable architecture like the Turing one. Among these, [

2,

7] argued that analog or natural computations should be used to conduct calculations involving continuous real numbers. The potential adaptivity of this type of model, however, is only restricted to the range between the discrete approximation of a continuous number and its unrepresented portion. Moreover, it lacks the interactions among the discrete domain and the continuous domain to solve the problem in their model as well. Recently, [

8] and its variants investigated so-called Neural Turing Machines, which use neural networks like LSTM [

9] as the controller to make the entire system differentiable for end-to-end training. Compared with this structure, the abstract controller in the proposed non-Turing machine (which will be called “Ren machine" for simplicity below) can still be discrete/binary-based for logic reasoning. This novel structure allows the flexibility of switching back and forth between the abstract domain and the specific domain to better approach a solution to a given problem with rules summarized or learned from thought/tool experiments during the process. What’s more, it also enables the interactive collaborations of specific contents and abstract contents on both types of tapes to command and instruct the controller for completing a task.

2. Related Work

There are early works studying the multi-tape variants of Turing machines such as [

10,

11]. It is proved that these multi-tape Turing machines are not essentially different from their single-tape prototype – simply increasing the number of tapes does not give rise to the capacity to compute any new functions, though their complexity of computing or realizing a function can be improved to some degree. Furthermore, various types of interactive multi-tape Turing machines have also been proposed and analyzed in the theoretical computer science community ([

12,

13,

14,

15]). However, one fundamental characteristic of these architectures that makes them different from Ren machine is that they only consider a single type of domain (namely, the abstract bit domain). As a result, even interactions in the single abstract domain are considered in some of these works, their potential reasoning ability and the ability of rule summarization, learning, and generalization are unlikely to go beyond the Turing machine’s limit. What is more, their research focuses on the computability/realizability of an assumed static function on these architectures, while using unconventional and nondeterministic computations based on autonomous rule formation and generalization in thought/tool experiments to solve practical problems (such as collision avoidance in robotics, mathematical reasoning in theorem proving, etc.) is not discussed due to its infeasibility on these Turing variants. Compared with these existing structures, the proposed Ren machine provides a more general architecture containing tapes not only in the abstract domain but also in the specific domain, and its computation and reasoning are hence implemented based on the mapping rules that are known in advance or learned from experiments among these domains.

3. The Proposed Architecture

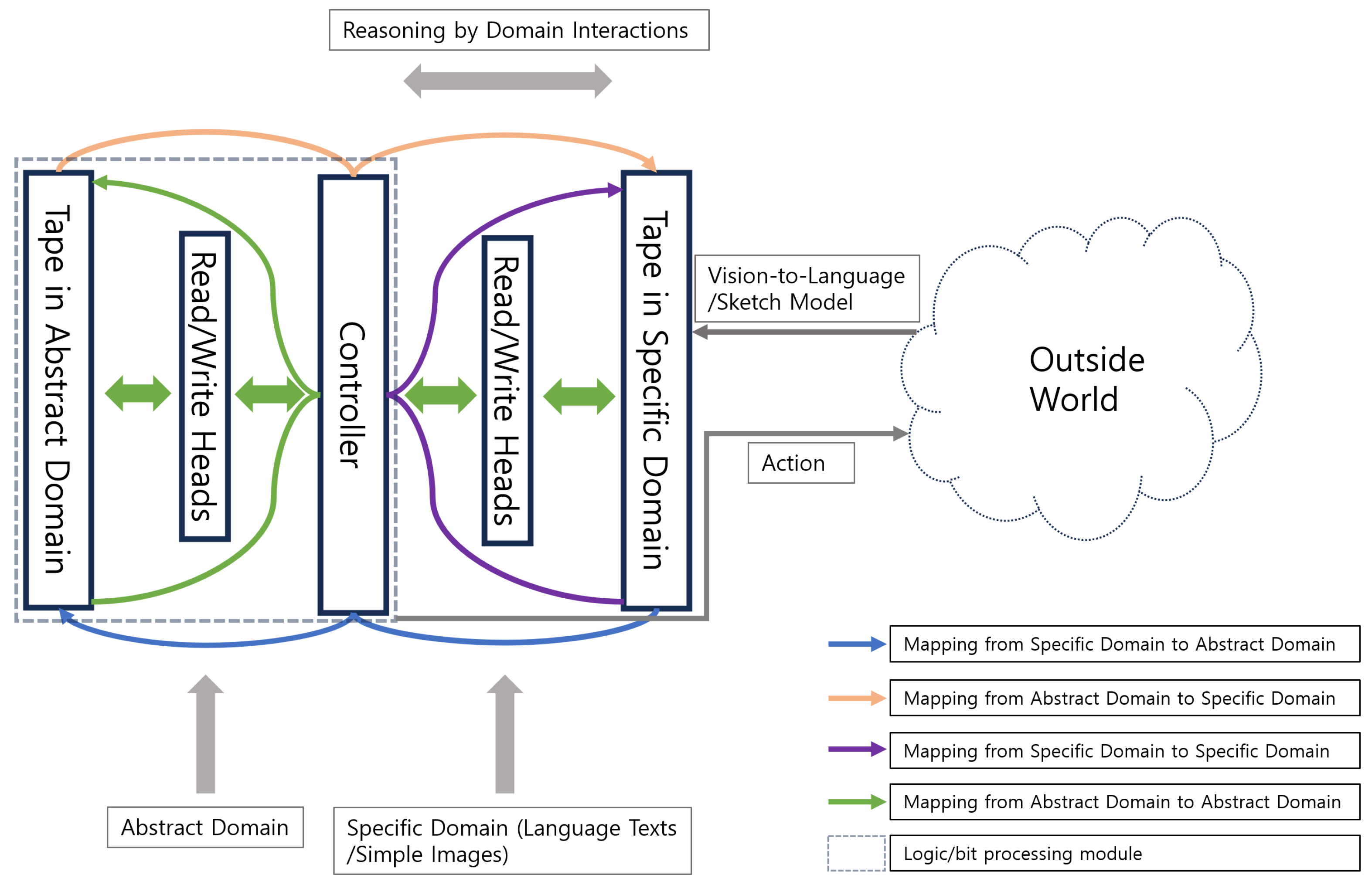

The components and their relations of Ren machine are elaborated in

Figure 1. This structure consists of a controller and two types of read/write heads and tapes, one in the specific domain and the other in the abstract domain. The interactions inter and intra the specific domain and the abstract domain are realized by different types of mappings annotated in this figure. These mappings can be implemented by applying prior knowledge or learned rules (e.g., neural networks or memorized tables) or simply rendering using a built-in function on the screen. Note that the writing and reading processes utilizing the heads in the specific domain are affected by the environment in the real world. As a result, some information from the outside world is also involved during these processes. As discussed above, the read/write heads and tapes in the specific domain are essential parts of a Ren machine because of their important effects on autonomous rule formation and generalization.

4. Experiment

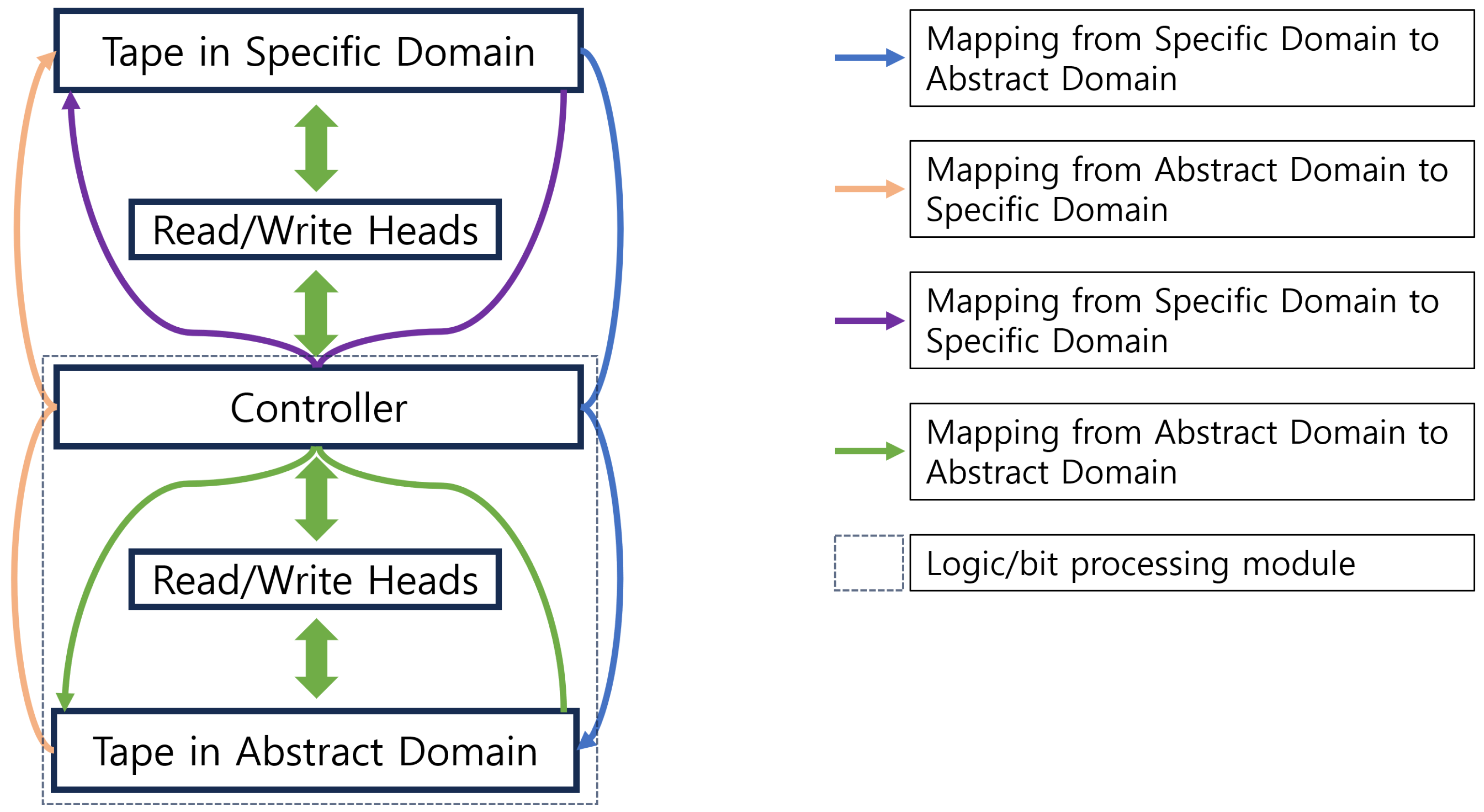

In the first experiment, we aim to autonomously find a method of computing the product of any positive integers by using very basic algebraic rules that are already known. The following diagram shows the workflow of Ren machine to calculate an expression where it learned the distributive rule of multiplication by experiments generated in the specific domain and used the rule to get the correct result of the expression.

In this process, when it is recognized that a potential rule is technically applicable to any objects in either the abstract domain or the specific domain, the rule will be formed, called, and applied to them as a trial to move towards a solution even if it seems that applying this rule to the objects is ‘meaningless’ (certainly a search strategy like reinforcement learning with simplicity and regularity rewards could be added for more ‘efficient’ lookup). New rules are summarized or learned from thought or tool experiments generated from prior knowledge and existing rules that have already been learned so far. For example, in the computing process demonstrated in

Figure 2, the distributive rule is learned by the cooperation of specific observations and abstract prior knowledge. Specifically, Ren machine can compute the multiplication of any small integers like

,

, and

using multiple additions by the original definition of multiplication. Then it finds that actually the equation

holds true. Then it generates an example in the specific domain accordingly by simply displaying the equation on the screen. Using a similar procedure, it can generate a large number of examples (images) in the specific domain showing that the distributive property exists. Then neural networks can be trained to learn the transformation between the images on the left side of the equation and those on the right side of the equation with a high confidence. It is shown in the experiment that such neural networks (e.g. LLaMA [

16], ChatGPT [

17]) are able to generalize to other pairs of integers that are unseen in the training, even when the integers are very large. After applying the transformation in the visual domain, we can use computer vision models such as YOLO [

18] to convert the equation back into the abstract domain. This procedure eventually enables Ren machine to autonomously learn a general method of calculating the multiplications of arbitrary positive integers. The accuracy of the reasoning process is guaranteed by the high accuracy of each reasoning step: each rule it uses is valid with a probability higher than

; therefore the theoretical overall accuracy of the multi-step reasoning process is over

.

We conduct the test of computing the multiplications in 20 pairs of positive integers listed as follows:

| 1234*3456, |

12345*34567, |

123456*345678, |

1234567*3456789, |

12345678*34567891 |

| 2345*4567, |

23456*45678, |

234567*456789, |

2345678*4567891, |

23456789*45678912 |

| 3456*5678, |

34567*56789, |

345678*567891, |

3456789*5678912, |

34567891*56789123 |

| 4567*6789, |

45678*67891, |

456789*678912, |

4567891*6789123, |

45678912*67891234 |

The results in this experiment show that the accuracy (

) achieved by the proposed method on Ren machine is significantly higher than that (

) achieved by the state-of-the-art large language model used in Microsoft Copilot [

19].

In the second experiment, we present how the proposed Ren machine completes the proof of the conclusion that “the summation of interior angles of a triangle is in Euclidean space" using the rules that are learned in advance and the prior knowledge base.

In this workflow, first, it is assumed that the machine knows from prior experiences that a flat angle (i.e., a straight line) is

, which also appears in the target conclusion to be proved. Then, a language model can be trained to generate a text prompt like “According to the question, first generate a triangle, then generate a line passing through one of its vertices" to potentially help prove the conclusion with the added auxiliary line. Next, rules based on a language-to-image model and a structured display of geometric objects (a line and a triangle) are used to map the texts to simple images in the specific domain. As we find, current LLM-based methods are not able to generate a structured image according to text prompts correctly. However, we can train image-to-image models to rotate and translate geometric objects in proper directions so that the straight line passes through one vertex of the triangle and becomes parallel to the opposite edge. After that, an annotation mapping rule in the specific domain can be applied to label the involved angles in the generated image. Sequentially, the rules of interior alternate angles and flat angle that are learned and memorized before can be used to convert the images in the specific domain to the symbolic angular equations in the specific domain, as shown in

Figure 3. Finally, one can complete the proof by applying the stored substitution rule in the specific (symbol) domain to the generated equations.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

In this paper, we propose a non-Turing architecture, Ren machine, that solves a problem by autonomously learning rules and building knowledge bases from generated experiments in the process of approaching an answer. It can input and output by using two types of read/write heads in both the specific domain and the abstract domain. The mappings among these domains can be conducted based on learned rules such as neural networks, memorized tables, or simply built-in rendering functions. In this way, the controller can be commanded/instructed cooperatively by both the contents on the tape in the abstract domain and those in the specific domain. In the experiments, it is demonstrated that this flexible mechanism enables Ren machine to solve the multiplication problem of positive integers in a self-directed manner with a higher accuracy rate compared with other state-of-the-art LLM methods. The machine’s superior reasoning ability is also shown in proving a theorem in Plane Geometry. Assume a thought chain for solving a problem has a length of 1000 and each rule it uses is valid with a probability of , then the thought chain achieves an accuracy rate of . More advantages of Ren machine could be further explored by coping with the problems that cannot be solved by Turing machine intrinsically. As we know, the halting problem is the problem of determining whether an arbitrary program will terminate or continue to run forever. This problem is proven to be undecidable on Turing machine, meaning that there exists no general algorithm on Turing machine that can solve the halting problem for all possible pairs of program and input. On the other hand, on Ren machine, since the controller is connected with the specific domain using another type of read/write heads, it can also be commanded/instructed by the contents shown on the tape in the specific domain. Thus, the halting problem can be addressed with significantly high accuracy, if one includes a clock in the specific domain to count the time that a program has been running for, or uses neural networks to recognize the text patterns of never-ending programs, or counts the number of steps from their printouts on the screen, etc. In this regard, instead of pretending to be human in conversation, if a machine can actively generate rules from thought/tool experiments, for generalizing them to approach an answer to the problem it tries to solve, then it can be closer to the real artificial general intelligence.

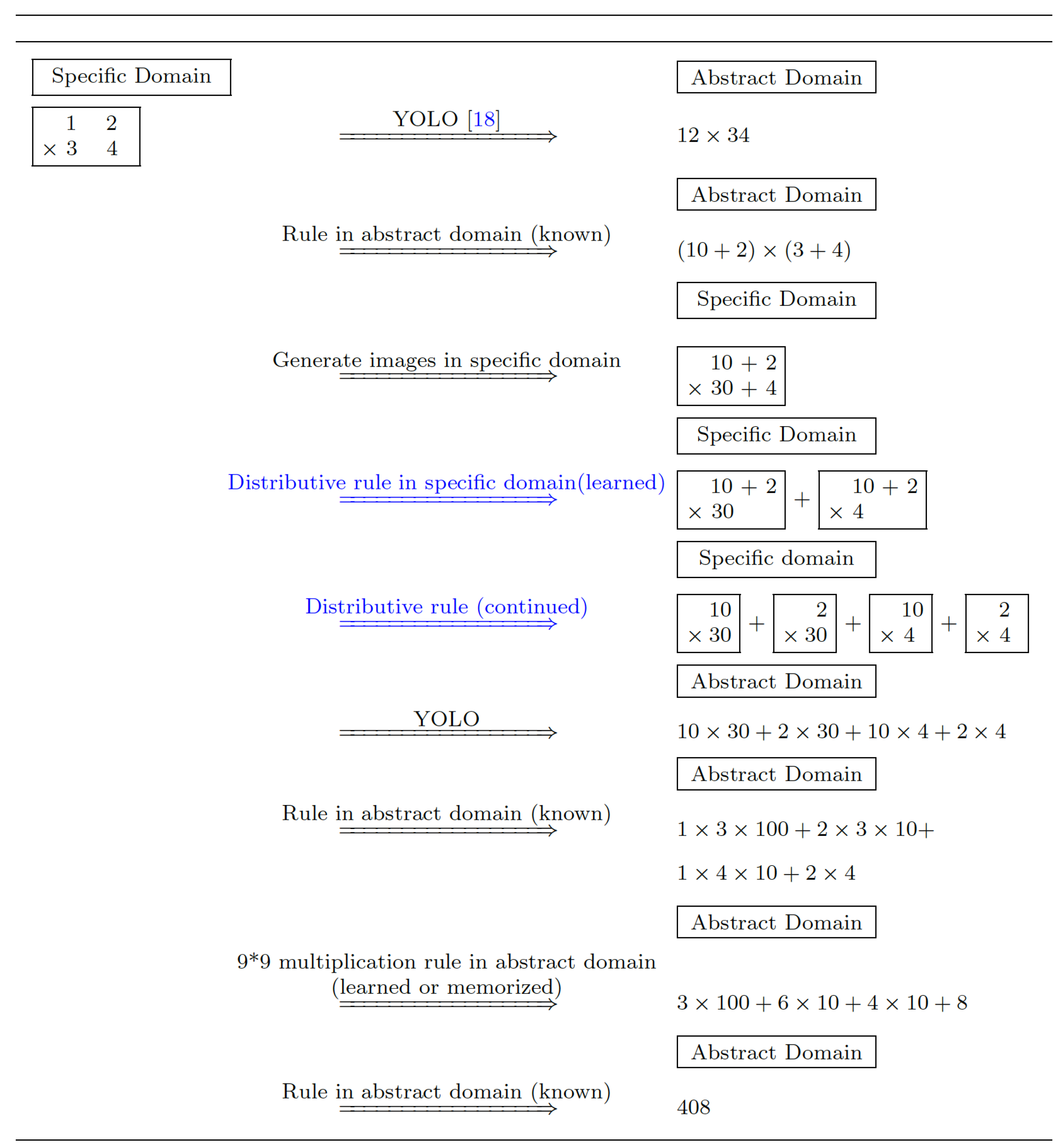

Appendix A. Non-Turing Robotics

Although recent Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models manage to enable robots to complete a variety of basic tasks, they still suffer from drawbacks in two aspects: (1) lacking sound reasoning ability to handle complicated tasks, and (2) requiring intensive environment setups, datasets, and computation for training and fine-tuning VLA model. To address these challenges, we propose a non-Turing robotic architecture based on Ren machine (see

Figure A1), which can conduct spatial-temporal reasoning through the interactions inter and inside specific domain and abstract domain.

On the proposed non-Turing robotic architecture based on Ren machine, the reasoning can be carried out by the interactions (mapping rules) between and inside abstract domain and specific domain. It comprehends the current situation in the outside world by firstly converting the scenario’s videos into sketches in the specific domain using vision-to-sketch mapping. Suppose the mapping rule (e.g., a vision-to-sketch model, or a simplified 3D rendering function using the parameters returned by the pose estimation module) is designed properly, the sketches will contain the necessary information to determine whether a collision is going to occur or not with high accuracy. Then, a mapping (e.g., a classification neural network) is used to convert the sketches into the contents in the abstract domain such as ‘True’ or ‘False’ to flag collision. In addition, a generative model or a sketch space updating module can be adopted to generate the sketches of the consequential scenario assuming that a tentative movement is implemented by the robot. By using this mechanism, the proposed robotic architecture can conduct multiple virtual trials to find out the best policy to avoid potential collisions from these thought experiments. The action generated by the best policy will then be executed by the robot in the real world. Notice that in this process the reasoning and computations are implemented based on the simple sketches instead of the full videos of real-world scenarios. As a result, the computational cost as well as the cost of setting up environments and generating data on the Ren machine-based robotic architecture will be markedly reduced.

Figure A1.

This shows the non-Turing robotic architecture based on Ren machine. The spatial-temporal reasoning is implemented based on the contents in the specific domain (such as a simple sketch of objects in the outside world) generated from applying vision-to-sketch mapping rule to videos of real-world scenarios. For example, when the sketch in the specific domain shows the collision is about to happen (i.e., the mapping result of the sketch into the abstract domain is ‘True’ for collision), the controller will generate another movement direction and generate a sketch of the scenario assuming that the robot has moved in this direction. By doing multiple low-cost thought experiments, it will choose the best direction from a finite candidate direction set and implement it in the real world. In the meantime, this process provides (data, label) pairs that can be used to train a sketch-to-best-direction classification neural network model.

Figure A1.

This shows the non-Turing robotic architecture based on Ren machine. The spatial-temporal reasoning is implemented based on the contents in the specific domain (such as a simple sketch of objects in the outside world) generated from applying vision-to-sketch mapping rule to videos of real-world scenarios. For example, when the sketch in the specific domain shows the collision is about to happen (i.e., the mapping result of the sketch into the abstract domain is ‘True’ for collision), the controller will generate another movement direction and generate a sketch of the scenario assuming that the robot has moved in this direction. By doing multiple low-cost thought experiments, it will choose the best direction from a finite candidate direction set and implement it in the real world. In the meantime, this process provides (data, label) pairs that can be used to train a sketch-to-best-direction classification neural network model.

As an example, the Vision-Sketch-Reasoning-Action (VSRA) method described in

Table A1 can be implemented on the proposed robotic architecture to complete a robot motion planning task of reaching a goal position and avoiding collision with obstacles.

The fundamental differences between our architecture and the Agent AI structure proposed recently in [

22] lie in the following aspects:

- 1)

In their structure, the virtual world is supposed to be as close to the real world as possible. Therefore, their virtual world is more static and its complexity is more like the real world’s, compared with the actively generated, simpler, and more dynamic sketch space in the specific domain of our robotic architecture.

- 2)

The reasoning is hence efficiently realized with low cost by the interactions inter and intra the abstract domain and the specific domain of the proposed Ren machine-based robotic architecture.

- 3)

Their structure based on the Turing machine does not have an actual sensor/camera observing the virtual world. Instead, they only have the inner parameters to reconstruct the complex virtual world. As contrast, on our robotic architecture, the contents in the workspace (the additional tape) in the specific domain can be efficiently observed and mapped into various domains, significantly facilitating the reasoning process.

The spatial-temporal reasoning workflow discussed above demonstrates that these differences/advantages enable the proposed Ren machine-based architecture to overcome the problems of insufficient reasoning ability and expensive computation and setup costs that are commonly encountered by Turing robotic structures.

Table A1.

The Pseudocode of The Vision-Sketch-Reasoning-Action (VSRA) Method in Motion Planning.

Table A1.

The Pseudocode of The Vision-Sketch-Reasoning-Action (VSRA) Method in Motion Planning.

|

While

|

The target is not attained And No collision occurs |

| |

Step 1 Get images of real objects taken from the top and the right side |

| |

with respect to the robot base |

| |

Step 2 Apply a computer vision model to convert the images to |

| |

3D sketches in a simplified simulative 3D space in which |

| |

cylinders and spheres are used to sketch the robot, and |

| |

smaller collision spheres to sketch other objects with a unit |

| |

arrow in the simplified 3D simulative space originating from |

| |

the end-effector point towards the goal |

| |

(Outside World to Specific Domain)

|

| |

Step 3 Get 3D voxels by viewing the 3D sketches in the robot base’s |

| |

coordinate system |

| |

(Specific Domain to Specific Domain)

|

| |

Step 4 Apply a sketch-to-direction model 1 to convert the 3D voxels |

| |

to an escape direction in the 3D sketch space with a scale in |

| |

range(, , 50) (divide the 3D space evenly into 36*36 |

| |

segments with 36*36 representative directions so that the model |

| |

is a classification model), or to an additional class “go directly

|

| |

to the target (zero escape direction)" 2

|

| |

(Specific Domain to Abstract Domain)

|

| |

Step 5 Control the robot to move in the real world in the direction |

| |

synthesized by the outputted (escape direction, scale) pairs |

| |

and the arrow direction (with a safe speed) |

| |

(Abstract Domain to Outside World)

|

References

- Holyoak, K.J. Why I am not a Turing machine. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 2024, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- MacLennan, B.J. Natural computation and non-Turing models of computation. Theoretical computer science 2004, 317, 115–145. [CrossRef]

- Harel, D.; Marron, A. The Human-or-Machine Issue: Turing-Inspired Reflections on an Everyday Matter. Communications of the ACM 2024, 67, 62–69. [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E. The turing trap: The promise & peril of human-like artificial intelligence. In Augmented education in the global age; 2023; pp. 103–116. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. The Turing Test and our shifting conceptions of intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, C.H. Is AI intelligent? An assessment of artificial intelligence, 70 years after Turing. Technology in Society 2022, 68, 101893. [CrossRef]

- MacLennan, B.J. Mapping the territory of computation including embodied computation. In Handbook of Unconventional Computing: VOLUME 1: Theory; 2022; pp. 1–30.

- Graves, A. Neural Turing Machines. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.5401 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-term Memory. Neural Computation MIT-Press 1997. [CrossRef]

- Hennie, F.C.; Stearns, R.E. Two-tape simulation of multitape Turing machines. Journal of the ACM (JACM) 1966, 13, 533–546. [CrossRef]

- Maass, W.; Schnitger, G.; Szemerédi, E.; Turán, G. Two tapes versus one for off-line Turing machines. Computational complexity 1993, 3, 392–401. [CrossRef]

- Verbaan, P.R.A. The computational complexity of evolving systems. Thesis, Utrecht University 2006.

- Sims, K. Interactive evolution of dynamical systems. In Proceedings of the Toward a practice of autonomous systems: Proceedings of the first European conference on artificial life, 1992, pp. 171–178.

- Van Leeuwen, J.; Wiedermann, J. A computational model of interaction in embedded systems. Techn. Report UU-CS-2001-02, Dept of Computer Science, Utrecht University 2001.

- Van Leeuwen, J.; Wiedermann, J. Beyond the Turing limit: Evolving interactive systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Current Trends in Theory and Practice of Computer Science. Springer, 2001, pp. 90–109. [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT, 2023.

- Redmon, J. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016.

- Microsoft. Microsoft Copilot: Your AI companion, 2023.

- Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. The international journal of robotics research 1986, 5, 90–98. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.A.; Mukadam, M.; Issac, J.; Birchfield, S.; Fox, D.; Boots, B.; Ratliff, N. Rmpflow: A geometric framework for generation of multitask motion policies. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2021, 18, 968–987. [CrossRef]

- Durante, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wake, N.; Gong, R.; Park, J.S.; Sarkar, B.; Taori, R.; Noda, Y.; Terzopoulos, D.; Choi, Y.; et al. Agent AI: Surveying the horizons of multimodal interaction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.03568 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).