1. Introduction

With the introduction of mainstream deep learning methods, the doors to solving more complex digital signal processing problems, such as Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Speech emotion recognition (SER), have opened. Reviewing research published in the past decade shows a positive trajectory [1] of efficiency and accuracy each year.

A group of the significant drivers of SER is the big tech companies trying to create a robust solution for this problem, with Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, Apple Siri, and Microsoft Cortana [2]. There has been an influx of research on SER, from proposals to create better training sets to methods that increase accuracy and to the ones that make the systems more robust and reliable in real situations.

The rationale behind these endeavors stems from the anticipation that advancements in Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) will significantly enhance the landscape of human-computer interaction. The pivotal role of SER lies in its potential to facilitate the development of systems capable of comprehending human commands with greater acuity and responding adeptly across diverse scenarios. Noteworthy instances of application include the optimization of interactions between smart speakers, virtual assistants, and end users. In particular, SER proves instrumental in refining the quality of exchanges within speech-to-text applications, addressing the challenges of informal language structures that deviate from conventional grammar and syntax. This is exemplified when written sentences may not accurately convey content due to the absence of appropriate intonation, such as in the case of polar (Yes/No) questions, as illustrated by the query “You pet the cat?” [3]. SER also has benefits in psychotherapy, customer service, remote learning, self-driving vehicles, and more [1].

As mentioned above, older research mainly focused on techniques used in automatic speech recognition (ASR) and machine learning [4] [3]. These methods’ results were limited, e.g., 74.2% accuracy [4], and 77% [3]. However, the newer publications focusing on deep learning are generating better results, with reporting 95% [5], 93% [6], 95.5% [7], and 97% accuracy [8].

In addition to the methods, many databases have been introduced for speech emotion recognition. General categories of emotional speech databases include natural, semi-natural, and simulated databases [1].

All considered, the reliability of SER models faces challenges in terms of fairness, robustness, and accuracy when confronted with environmental noise, out-of-distribution test settings, and gender bias. Environmental noise, such as background sounds, can introduce variability and hinder the model’s performance. Out-of-distribution test settings, where the data differs significantly from the training set, threaten the generalization capabilities of SER models. Additionally, gender bias can manifest in disparities in the recognition accuracy across different gender groups. Recognizing these vulnerabilities, we are exploring normalization techniques, noise reduction strategies, and the utilization of a comprehensive super corpus to enhance the fairness, robustness, and overall accuracy of SER models in diverse and challenging scenarios.

1.1. Contribution

Despite the notable achievements of deep neural networks (DNNs), their efficacy is contingent upon the characteristics of the training data, and concerns persist regarding their generalization capabilities. While recent attention has been directed toward assessing the fairness and robustness of DNNs in computer vision and natural language processing, to the best of our knowledge, we are the first to explore the robustness of SER models to speaker’s gender and out-of-distribution test samples. Specifically, our contribution includes:

Building and evaluating a series of modern deep learning-based architectures, establishing a new baseline that outperforms older benchmarks across accuracy, F1 score, precision, and recall metrics while maintaining balanced performance across datasets and preprocessing strategies.

Introducing a super corpus that augments the sample pool and diversifies the datasets, enabling broader applicability and robustness.

Conducting a detailed examination of model robustness concerning speaker gender and cross-corpora scenarios.

Finally, we will provide a comprehensive discussion on how our proposed super corpus, coupled with various preprocessing strategies, contributes to improving generalization, mitigating gender bias, and enhancing the robustness of the SER models to the out-of-distribution data samples.

The resulting models and datasets serve as a foundational baseline for future research in this domain.

1.2. Organization

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 revisits related works in cross-corpus SER and fairness discussions in speech processing.

Section 3 sets up the problem and formalizes the approach for crafting super corpora.

Section 4 discusses the datasets and the examination metrics and models. We will present and discuss the results in

Section 5; the last section concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

The known problem of limited data available to train SER models has driven many to try creative methods such as augmenting data or cross-corpus training. In this chapter, we will review some of the works on mitigating data limitations and demographic bias of SER systems. Additionally, one way of mitigating the lack of inductive biases, i.e., architectural choices and robust priors in deep learning, is expanding the training data [9] [10]. However, as suggested by [11], various inductive can be equal, more or less data, and in scenarios involving extensive datasets, the benefits conferred by inductive biases may diminish, implying that the evaluation of the advantage derived from inductive biases and their implementation becomes particularly interesting in transfer settings where limited examples for the new distribution is available.

In one of the early efforts at data augmentation, Zhang et al. [12] researched the suitability of unsupervised learning in cross-corpus settings using ABC [13], AVIC [14], DES [15], eNTERFACE [16], SAL [17], and VAM [18] datasets. SAL and VAM are based on arousal/valence; the rest are categorical emotions. Therefore, they mapped the categorical databases to Arousal and Valence descriptors to unify the data. They employed the openEAR toolkit [

19] to extract features and retain 39 functional of the 56 acoustic Low-Level Descriptors (LLDs). As an extra step in their preprocessing, they normalized all databases to zero means. And finally, to evaluate their experiment, they followed a cross-corpus leave-one-out strategy.

To evaluate their methods, they have three experiments planned. The first experiment was creating an agglomeration of 3 databases and testing on one database. The second experiment was creating a supervised training database based on 3 of the databases and then unsupervised training the model with two other databases and testing the remaining database. The last experiment involved training on five databases and testing on the remaining. They conclude that adding unlabeled samples to an agglomerated multi-corpus training set improves the accuracy of the model; however, the improvement on average is half of the results if they had added the same amount of labeled data.

In 2019, Milner et al. [19] investigated cross-corpora SER by incorporating a bidirectional LSTM with an attention mechanism. Their research investigates information transfer from acted databases to natural databases. Moreover, they have also looked into domain adversarial training (DAT) and out-of-domain (OOD) models and considered adapting them.

Their network is a triple attention network consisting of a BLSTM, the attention architecture, and the emotion classifier at the end. For domain adversarial training, they also consider adding a domain identifier to the training set that teaches the model how it is doing with each dataset. In their work, they use two acted datasets, eNTERFACE and RAVDESS, one elicited dataset, IEMOCAP, and one natural dataset, MOSEI.

This study concludes that when testing cross-corpus, the matched results outperform mismatched, and the model trained on simulated datasets generally achieves the best mismatched performance. They also discuss that the model trained on multi-domain is performing better than all of the other mismatched models due to more generalization resulting from having a larger dataset. They continue to show in their results that adding the domain information does not help the multi-domain model to generalize better, but training with more other domains helps improve the mismatched results.

In 2021, Wisha et al. [20], worked on a cross-corpus, cross-language ensemble method to detect emotions from 4 languages. They have used Savee (English) [21], URDU (Urdu) [22], EMO-DB (German) [23], and EMOVO (Italian) [24] in their research. However, their study only investigates binary valence. To train their classifier, they used Spectral features such as 20 MFCC coefficients and prosodic features defined in eGeMAPS [25]. The classifiers that create the ensemble are SVM with a Pearson VII function-based Universal Kernel, a random forest with ten trees, and a C4.5 algorithm decision tree.

As a result of their study, they claim that their methods have an increase of 13% for URDU, 8% for EMO-DB, 11% for EMOVO, and 5% for Savee in their in-corpus tests. They also report that in their cross-corpus tests, they achieved an improvement of 2% training on Urdu and testing on German data, 15% when testing on Italian, and when testing on Urdu while trained on German, 7%, with training with Italian, 3% and lastly training with English, they have gained a 5% improvement in their accuracy.

In 2021, Braunschweiler et al. [26] investigated cross-corpus data augmentation’s impact on model accuracy. In their research, they incorporate a network with 6 layers of CNN, a Bidirectional LSTM model with 2 layers of 512 nodes, and 4 fully connected layers fed to an attention mechanism. The databases used in this research are IEMOCAP [27], RAVDESS [28], CMU-MOSEI [29], and three in-house single speaker corpora, named TF1, TF2, and TM1; F and M stand for female and male, respectively. The classes they chose to recognize using their model were angry, happy, sad, and neutral. To increase variability in their samples and improve their model generalization, they also applied variable speed, volume, and multiple frequency distortions such as bass, treble, overdrive, and tempo changes to the samples.

They discuss that their investigation shows that in situations where the model was trained with one database and tested with another, they have an accuracy decline of 10-40%. They further discuss that their results were improved when the model was trained with more than one corpora and tested on one of the corpora in the training set, except for their single-speaker datasets. The last result that they report is a 4% gain in accuracy with additional data augmentation.

Later, in 2022, Latif et al. [30] introduced an adversarial dual discriminator (ADDi) network trained on cross-language and cross-corpora domains. They claim their model improves the performance over the state-of-the-art models. Their model contains an encoder, a generator, and a dual discriminator. In their model, they are mapping the data to a domain-invariant latent representation. The generator uses the result of the encoder to generate target or source domain samples and the two adversarial discriminators that, in combination with the generator, tune the domain invariant representation to minimize the loss function. The generator and the encoder act as decoders to construct the input samples.

In their self-supervised training process, they introduce synthetic data generation as a pretext task that helps to improve domain generalization. As a byproduct, synthetic emotional data is produced that can augment the SER training set and help with more generalization.

They further discuss that introducing the ADDi network improves cross-corpus and cross-language SER without using target data labels. They also add that their model significantly improves by feeding partial target labels. They also claim that with the help of the self-supervised pretext task, they can achieve the same performance by training their ADDi network with 15-20% less training data.

Regardless of the accuracy of deep learning models, their robustness to changes in data distribution and making fair decisions is still open research. In 2020, Meyer et al. [31] published Artie Bias Corpus as the first English dataset for speech recognition applications with demographic tags, age, gender, and accent curated from Mozilla Common Voice corpus (Needs citation). Additionally, they published open-source software for their dataset to detect demographic biases in ASR systems.

Similarly, in 2021, Feng et al. [32] quantified the bias in the state-of-the-art Dutch Automatic speech recognition (ASR) system against gender and age. Their work reported the bias regarding word error rates (WER). They concluded that the ASR system studied had a higher WER for male Dutch speakers than for female speakers.

Lastly, in 2022, a team of researchers from Meta [33] released a manually transcripted dataset containing 846 hours of corpus for fairness assessment of ASR and facial recognition systems across different ages, genders, and skin tones. According to their results, several ASR systems lack fairness across gender and skin tone and have higher word error rates for specific demographics.

3. Problem

The current challenge in the field pertains to the resilience of deep learning models against out-of-distribution data instances and demographic biases. This matter persists as an unresolved concern. Our approach involves the utilization of pre-existing open-source datasets to enhance the generalizability of established Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) methodologies. Furthermore, we endeavor to alleviate biases directed towards particular speaker genders whenever feasible. We assert that the augmentation of datasets within the realm of deep learning models for SER holds substantial potential, mainly when such augmentation is cost-effective and maintains the explicability of the end-to-end process. Within our dataset repository, we permit the augmentation of each dataset with all others. Notably, we introduce a specific case wherein solely simulated datasets undergo augmentation. This is motivated by their shared attributes, such as a controlled noisy environment and a predefined set of speakers. Additionally, our experimental framework examines the impacts of noise reduction and normalization.

4. Experimental Setup

In this section, we introduce our approach to generating super corpora. Additionally, we explain how we built our baseline setup based on a wide range of available architectures for deep learning-based SER.

4.1. Super Corpora

As previously stated, the performance of Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) systems experiences degradation when confronted with out-of-distribution samples. Furthermore, as demonstrated in

Section 5, the performance of these systems varies inconsistently across different speakers’ genders. In our proposed solution, we endeavor to address these issues by mitigating the impact of data distribution disparities. This is achieved through the augmentation and amalgamation of diverse datasets, yielding a comprehensive dataset called a “super corpus.”

In Speech Emotion Recognition (SER), datasets are classified into three categories: Natural, Semi-Natural, and Simulated. Natural datasets are derived from authentic speech instances from diverse contexts such as news, online talk shows, and customer service call recordings. Labeling such datasets is inherently challenging due to the ambiguity of speaker intentions and the potential for varied listener interpretations of emotions. Consequently, the labeling process necessitates a sizable cohort of annotators and a structured voting system to determine emotional labels. Another inherent challenge with natural datasets lies in the dynamic nature of emotions within spontaneous speech. For instance, in a customer service call, emotions can transition rapidly from a neutral state to frustration or anger within a span of seconds. This fluidity poses difficulties in precisely labeling utterances or even entire sentences, constituting a complex and subjective task [1]. Examples of natural datasets include Vera Am Mittag (VAM) [18], and FAU Aibo [34].

Semi-natural datasets are created based on predefined scenarios and plots, and then one or more voice actors execute them. The emotional expressions within this dataset category are not strictly organic and may sometimes be exaggerated. Nonetheless, the advantage lies in achieving heightened control over the dataset, as the intended emotions are known, rendering the labeling process more dependable. However, challenges persist within this dataset paradigm, particularly concerning the dynamic nature of emotions and the intricate task of labeling utterances [1]. IEMOCAP [27], Belfast [35], and NIMITEK [36] are examples of this type of dataset.

The third dataset category, simulated, is constructed from a set of emotionally neutral sentences enunciated by voice actors who infuse various emotions into their delivery. The employment of emotionally neutral sentences imbued with diverse emotional expressions serves dual purposes. Firstly, it prevents the acquisition of emotionally biased sentences being learned by machine learning models, thereby mitigating the risk of triggering responses based solely on, for instance, the identification of emotion-related keywords such as “angry” within a speech signal. Secondly, the repetition of identical sentences articulated with different emotions ensures that the classifier model remains impervious to the semantic content of the sentences, thereby facilitating the isolation of the shared direct current (dc) component in the convoluted signal field [1]. EMO-DB (German) [23], DES (Danish) [15], RAVDESS [28], TESS [37], and CREMA-D [38] are examples of this type of dataset.

To systematically select integrated datasets, we establish our criteria set as follows: the primary criterion for dataset selection is language. Given the variation in how emotions are expressed through speech across different languages, we exclusively consider datasets in the English language. Subsequently, for result comparison, we opt for datasets associated with multiple models substantiated by published papers. Furthermore, given our focus on addressing the challenge of exposure to out-of-distribution data samples, we prioritize datasets characterized by a substantial volume of samples and a diverse spectrum of emotional expressions, encompassing not only positive or negative sentiments. Plus, we will utilize simulated-only and semi-natural datasets to address labeling challenges, variations in utterance size, and linguistic nuances related to emotional content. Therefore, from the list of open-sourced datasets in English, we chose three simulated English datasets of RAVDESS, TESS, and CREMA-D, plus the widely used semi-natural dataset of IEMOCAP. Ultimately, we abstain from employing augmentation processes rooted in deep learning to maintain interpretability within our methodology. Instead, we exclusively leverage the extant data samples to augment each dataset. This will facilitate subsequent extensions of our robustness evaluations to encompass more intricate scenarios, notably including assessments of robustness against adversarial attacks, which we will address in future works.

From the selected databases, which feature a variety of emotions, we found that four emotions, Happiness, Anger, Sadness, and Neutral, are present in all of them. We decided to use these samples for our project. In

Table 1, we present a summary of each dataset. Since we aim to investigate the performance of models w.r.t. bias against speaker’s gender, the presented statistics are divided based on two groups of speakers, Male and Female.

4.1.1. Building the Super Corpora

To construct our experimental corpus, we utilized a selection of databases, each comprising PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) encoded WAV files. However, the encoding formats, sample rates, and other audio characteristics varied significantly across the databases. For instance, the CREMA-D database had a sample rate of 16 kHz, while others used 48 kHz. Additionally, two databases were recorded in stereo, while the remaining two were mono. We resampled the audio files to 16-bit, 16 kHz, and mono signals to ensure uniformity across all datasets.

Upon reviewing file sizes and utterance durations, we observed that several utterances in the IEMOCAP database were shorter than one second. These short samples presented challenges even for human listeners in reliably identifying emotions. Consequently, we excluded all samples with less than one-second durations from our dataset.

Further analysis of the files revealed significant statistical differences across the datasets, including variations in average mean, DC component (Mean Signal Offset), peak amplitude, amplitude range, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), voicing characteristics such as Zero-Crossing Rate (ZCR), and prosodic features. Notably, voicing and prosodic features are closely linked to the emotional content of speech signals.

In contrast, features like the DC component, Root Mean Square (RMS) energy, and SNR primarily create energy-related signal denormalization effects. For example, normalizing the audio could reduce the energy in high-frequency samples (e.g., Angry or Happy emotions) or mitigate noise interference in low-energy samples (e.g., Sad emotions). Moreover, the same normalization will reduce the relative prominence of high-energy components (e.g., transients or spikes) across all frequencies. As a result, their perceptual prominence will change. Similarly, spectral noise reduction will attenuate energy at the signal’s lower and higher frequency margins as an unwanted effect.

One of the key features in gender identification is the signal’s high- and low-frequency energy content [39]. Consequently, these preprocessing methods are likely to reduce gender-specific characteristics in speech. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that normalization and spectral noise reduction would remove more gender-specific discriminative content than emotional information from the speech signals.

We applied preprocessing methods, including RMS Normalization and Spectral Noise Reduction, to test this hypothesis and evaluate their effects on classification performance and bias. We implemented four preprocessing schemes and applied them to all datasets:

In the next step, we created a series of Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficient (MFCC) representations for all datasets while retaining the original PCM (WAV file) versions. For MFCC generation, we experimented with different window sizes in both time and frequency domains. Time-wise, we used shorter window sizes, such as 25 ms, and longer durations approaching one second. Frequency-wise, we generated representations with 13 coefficients (including delta and delta-delta) and 64 coefficients (also with delta and delta-delta).

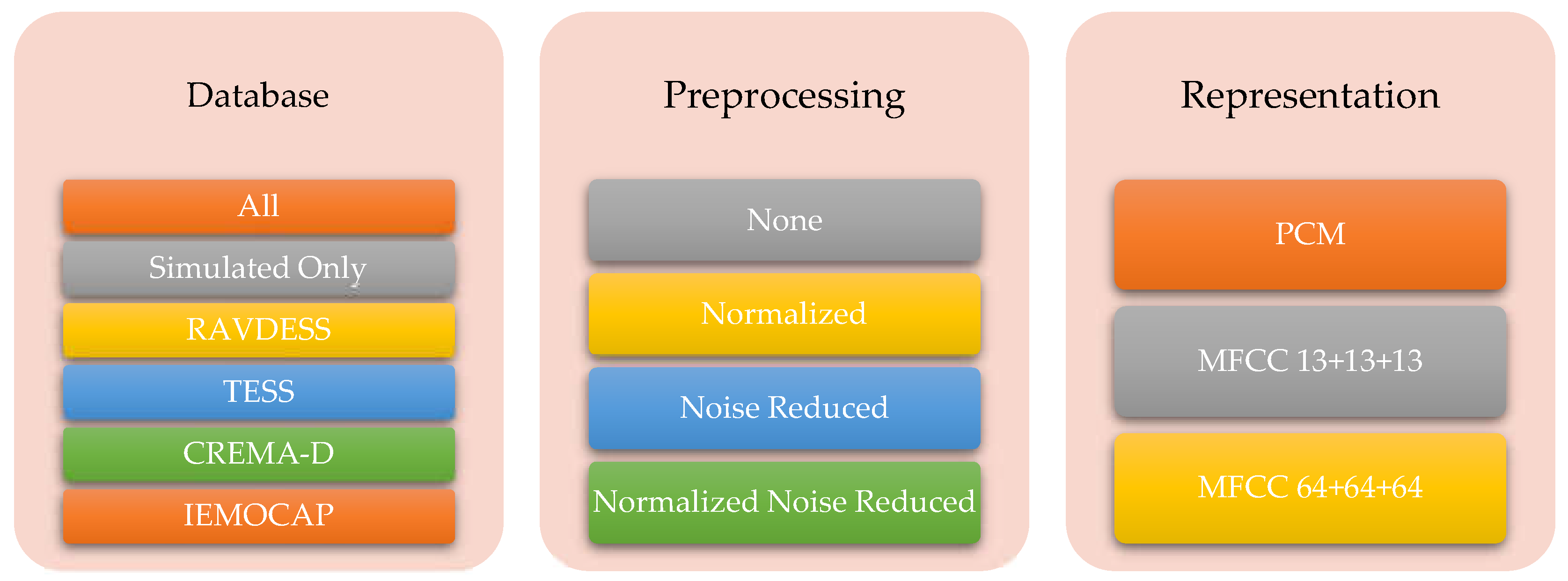

Additionally, we experimented with various database combinations. These included:

Merging all samples from all databases into a single bucket (All),

Using only simulated database samples (Simulated Only),

Keeping each database separate.

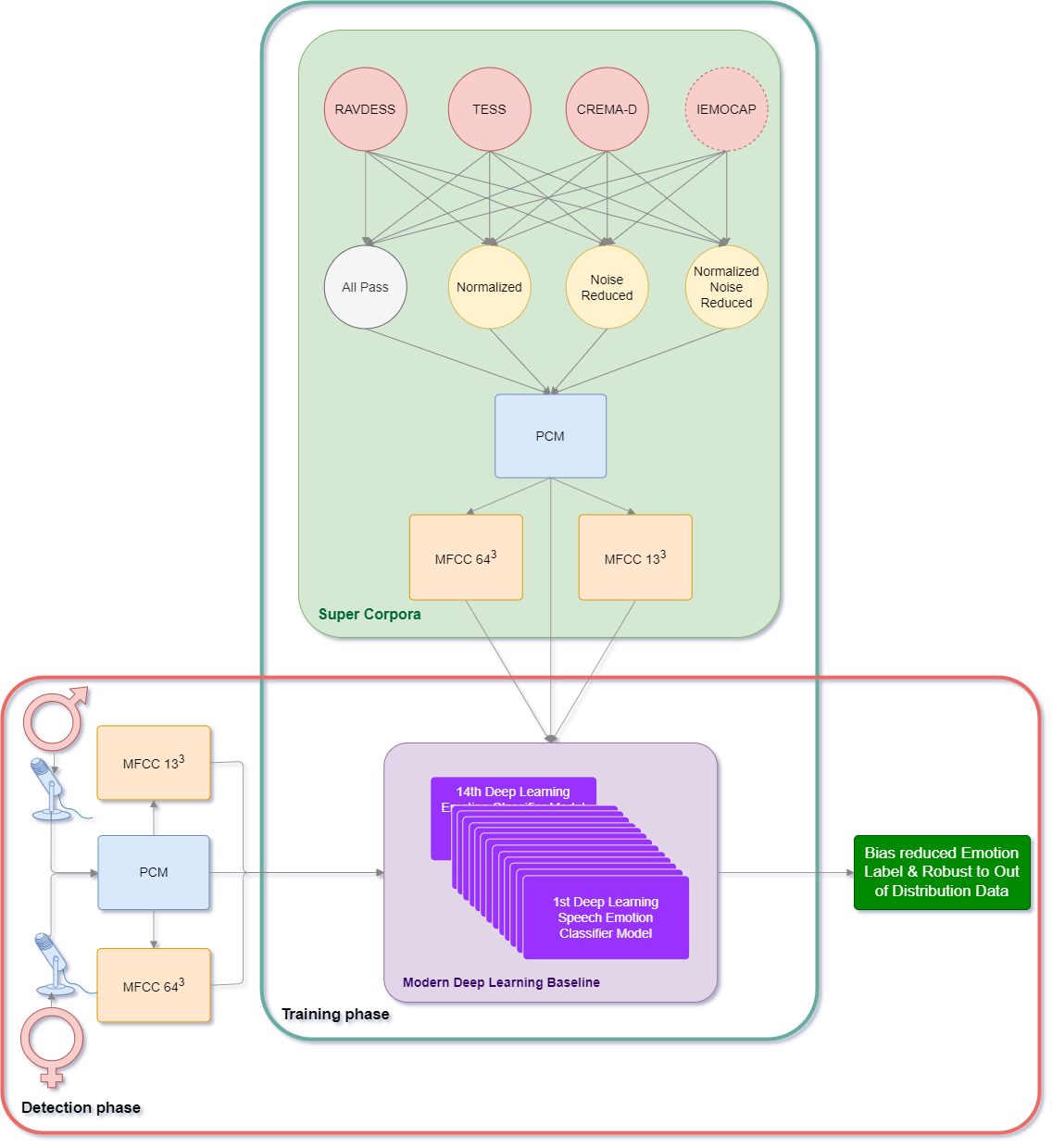

This setup resulted in six database combinations. By applying all preprocessing schemes across these combinations, we built a total of 72 databases for analysis. The following figure illustrates all the database combinations used in this investigation.

Figure 1.

Each combination of databases had gone through all of the preprocessing options, creating four variations. Then, each of the variations was represented by the representation schemas.

Figure 1.

Each combination of databases had gone through all of the preprocessing options, creating four variations. Then, each of the variations was represented by the representation schemas.

4.2. Deep Learning-Based SER

Creating a versatile baseline is essential to covering a wide range of diverse approaches to SER. Therefore, we have chosen several deep learning methods, ANN-based, CNN-based, and LSTM-based, to cover various methods applicable to MFCC preprocessed speech datasets. In

Table 2, we present a summary of the networks we have examined, and we will explain the result in

Section 5.

The architecture names in the first column of

Table 2 follow a systematic notation to represent the layers used in each model. For instance, “3XCNN1D 1XLSTM 2XDENSE” refers to a model that begins with three one-dimensional convolutional neural network (CNN) layers, followed by a single Long-Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layer and concludes with two fully connected dense layers. As clarified in the literature [1], each layer type serves a specific purpose in processing the speech data, which we briefly revisit in the following.

4.2.1. 1D Convolutional Layers (CNN1D)

In SER, CNN1D captures spatial patterns across features, making them ideal for analyzing temporal sequences like MFCCs, which encapsulate the frequency-time patterns in speech signals.

4.2.2. 1D Temporal Convolutional Networks (TDCNN1D)

Architecturally, TDCNN1D is similar to 1D CNNs but tailored to capture longer dependencies using dilated convolutions. These enable the network to look further back in the sequence without substantially increasing the computational cost.

4.2.3. Long short-term memory (LSTM)

LSTM Layers are recurrent neural networks (RNNs) designed to capture long-term dependencies and temporal relationships, which are critical for speech-related tasks, where context over time can influence emotion detection.

4.2.4. Dense

Finally, Dense (Fully Connected) Layers integrate the features learned by previous layers, enabling the model to make final classifications or predictions.

Each model configuration in

Table 2 varies based on the dataset used (e.g., IEMOCAP, CREMAD) and preprocessing techniques applied to the MFCCs, such as denoising or normalization. These variations help us understand the model’s robustness and adaptability across different datasets and preprocessing choices, providing a comprehensive foundation for Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) research.

4.3. Downstream Bias

Female speakers convey their emotions more expressively than Male speakers, which could result in inconsistent performance if the classifier is used in real-world applications. The empirical true positive rate (TPR) estimates the probability that the classifier accurately identifies a person’s emotion from their speech. Following previous research [40] and [41], we measure downstream bias by examining the empirical TPR gap between speeches for each gender set. First, define

where g is a set of genders, and y is an emotion.

and

are the true and predicted emotions, respectively. Then,

bias (

) is

where if a classifier predicts “Angry” for a Male speaker much more often than for a Female speaker, the TPR ratio for the “Angry” class is low.

5. Results and Discussions

This section presents the results of employing our augmentation process to craft super corpora on the deep learning-based SER models. We show both predictive performance-related experiments on all datasets and gender-specific generalization experiments.

When developing SER systems, the final model is trained and tested on a specific dataset. In this situation, the generalization and predictive performance of the developed model are constrained to the dataset. However, based on our experiments in this section, we demonstrate that the models’ performances are inconsistent in inner-corpora and cross-corpora settings. Additionally, even the best models, i.e., those with high accuracy and F1 scores, are biased, and their performance is inconsistent across different speaker genders. Ultimately, our proposed augmentation approach effectively improves the cross-corpora performance, also known as exposure to out-of-distribution generalization, and mitigates gender bias.

We have described the build process of our Super Corpora experiment in

Section 4.1.1. As a result, we had 72 databases and over 13 models with which to run the experiment. After some experimentation and comparing the results, as one of our objectives was adding a limited computation overhead, we continued working with the MFCC window of (120, 39), about 600ms audio, and 13+13+13 coefficients with a 25% overlapping window. We dropped using the 64+64+64 MFCCs, as their performance gain was limited compared to complexity overhead. Also, in our initial experiments, we explored the utilization of spectrograms, as suggested by Wani et al. [42]. However, spectrogram-based experiments are not computationally efficient and suffer from implicit biases.

We conducted extensive experimental evaluations across a range of network architectures and varying model sizes applied to each dataset. However, in this section, we only report the performance of top networks on each dataset and finally extend our augmentation experiment on them. It is noteworthy that DSCNN2D, as SER state-of-the-art architecture, has not consistently outperformed other architectures in our experiment.

Additionally, the gender-bias hypothesis in the form of downstream bias is measured for each dataset separately and combined. This allows us to investigate whether the bias is influenced by the dataset specification or implicitly by the network architecture. The bias hypothesis here is measured using the TPB metric (described in

Section 4.3) as well as the differences in predictive metrics (accuracy, F1 score, precision, recall, and Confusion matrix) between different groups of speakers and emotions. Moreover, we investigate how models trained with a particular dataset using different preprocessing approaches, normalization, and noise reduction are vulnerable when exposed to out-of-distribution data samples. Finally, we present how our proposed super-corpus improves each deficiency and the emotional confusion of these models for female and male speakers.

Table 2 presents the overall accuracy and F1 score, precision, and recall of each top architecture across individual datasets and the proposed super corpus in four preprocessing scenarios. As mentioned in

Section 4.1.1, in our experiments, we refer to the super corpora that have been augmented by using all datasets as “All,” and as the name implies, “Simulated only” refers to the super corpora that have incorporated RAVDESS, TESS, and CREMA-D in augmentation process.

5.1. Deep Learning Architectures and Their Performance

As mentioned in the previous section, IEMOCAP is a semi-simulated and relatively large dataset. As can be found from the results, SER models can benefit from our data augmentation approach to improve their generalization and demonstrate better predictive performance at no computation cost since the batch size and training epochs have been fixed for all of the reported results. Notably, having the best performance over the TESS dataset can be explained by its unique design, smaller spoken content variation, and only two female speakers uttering all the samples. Apart from the TESS dataset, the “simulated only” augmented dataset effectively outperforms all others, regardless of the preprocessing schemes.

At the beginning of this study, one objective was to establish a modern baseline for the SER models, ensuring future comparisons are not limited to state-of-the-art models from two decades ago. To this end,

Table 3 summarizes the previously published state-of-the-art results across the model architecture families we implemented and tested and compares our models and their corresponding best-performing counterparts. Our models demonstrate superior predictive performance compared to results reported in prior research. Moreover, the models presented in this work are assessed for generalization and fairness. In contrast, many prior works, including those referenced in

Table 3, primarily report accuracy alone, offering a limited perspective on system performance.

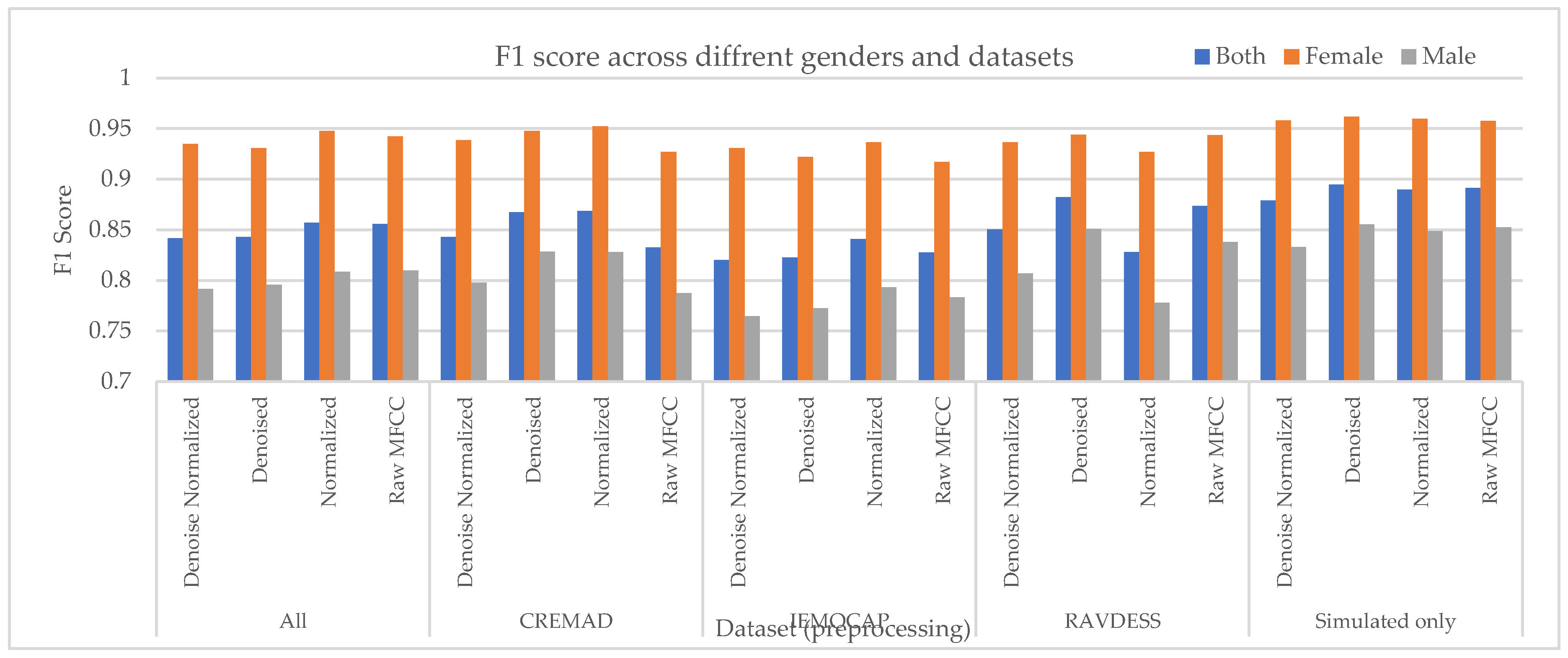

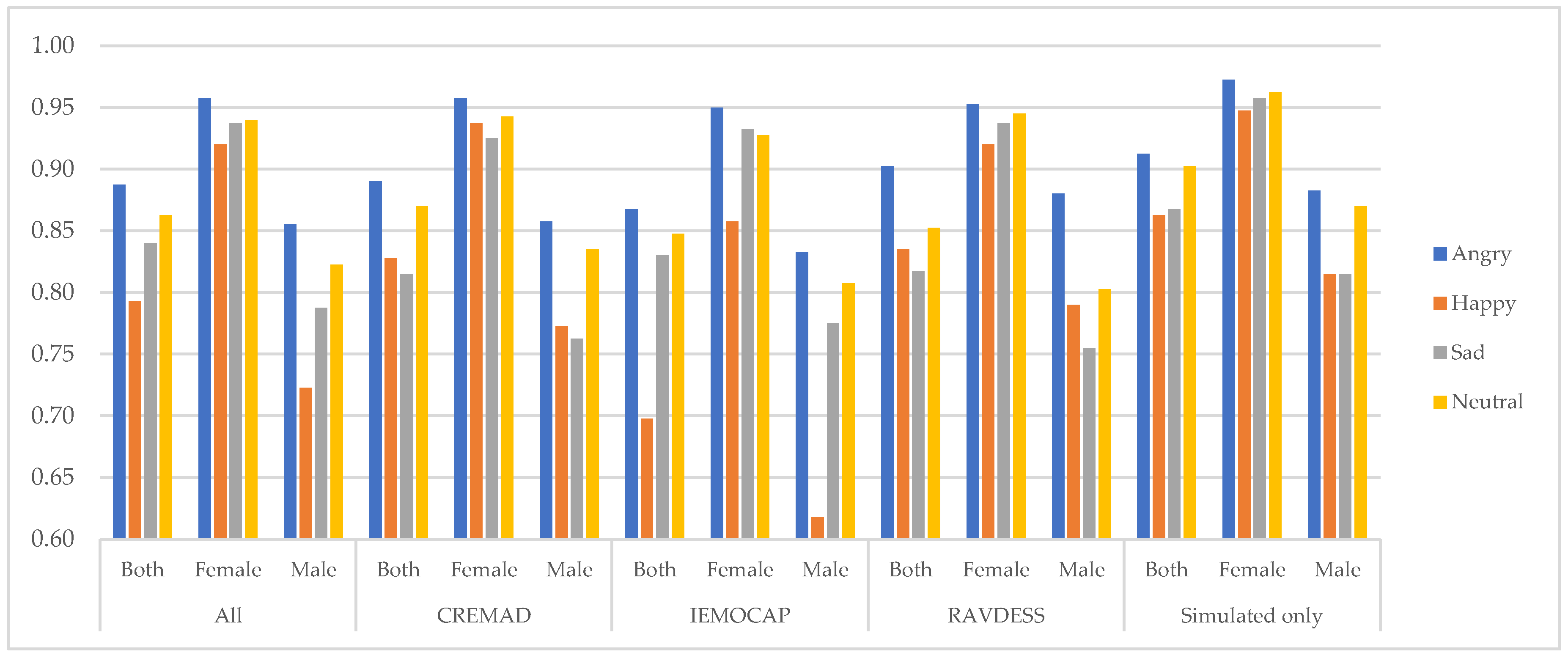

In the next step and for bias assessment, we have decoupled Female specker data samples from Male speakers and compared their performance per speaker. As can be found from

Figure 2, the performance of models is not consistent and robust w.r.t. speaker’s gender. However, under constrained training setup, i.e., fixed training epochs and batch size, and barely employing our augmentation approach, not only can improve the predictive performance of models but also develop their robustness across different gender and reduce the bias that can be measured by

), of “Both”, “Male“ and “Female” speakers. Additionally, our super corpora augmentation approach is effective regardless of conventional preprocessing approaches, reducing the overall computation cost of SER systems.

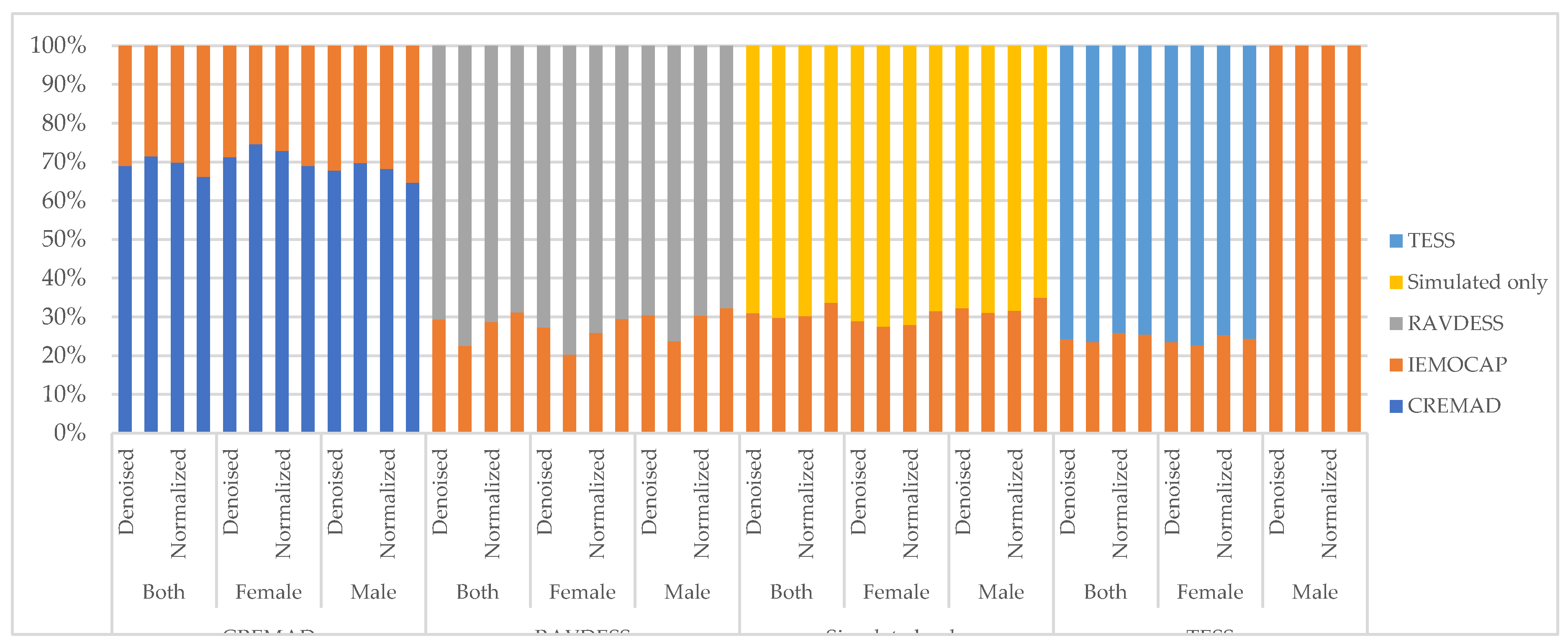

In the following and to demonstrate the cross-corpora effectiveness of our approach, we present the performance of previously mentioned models when trained with each simulated dataset, TESS, RAVDESS, IEMOCAP, and when trained with our “simulated only” super corpora and tested against IEMOCAP as our excluded dataset.

As

Figure 3 shows, regardless of the inductive biases that fit each previously mentioned model to the training dataset, all models suffer from exposure to out-of-distribution datasets. This is critical in training and deploying models with a specific dataset to real-world problems. However, training models with a mixture of datasets can improve the generalization of models to out-of-distribution scenarios, even where the model has not seen any data sampled from the test data distributions.

5.2. Emotion-level bias mitigation

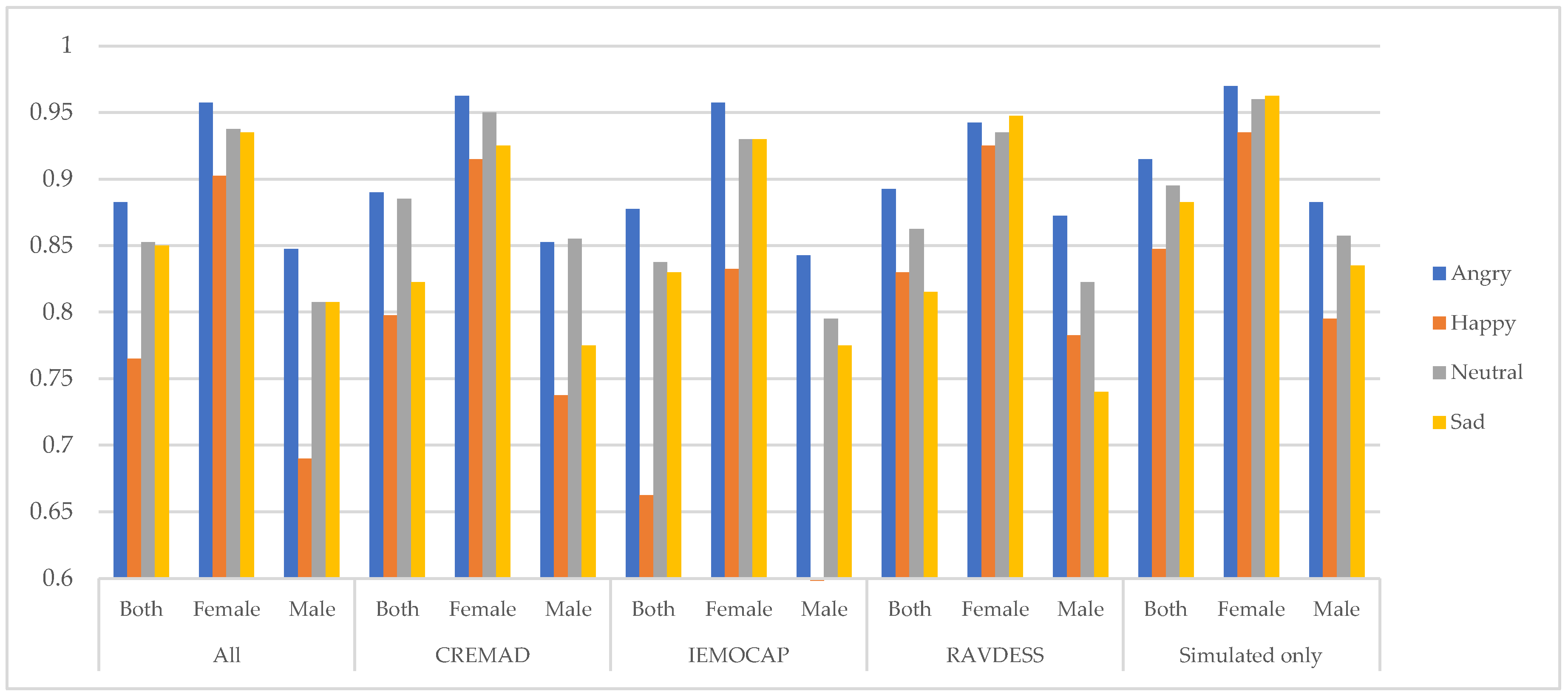

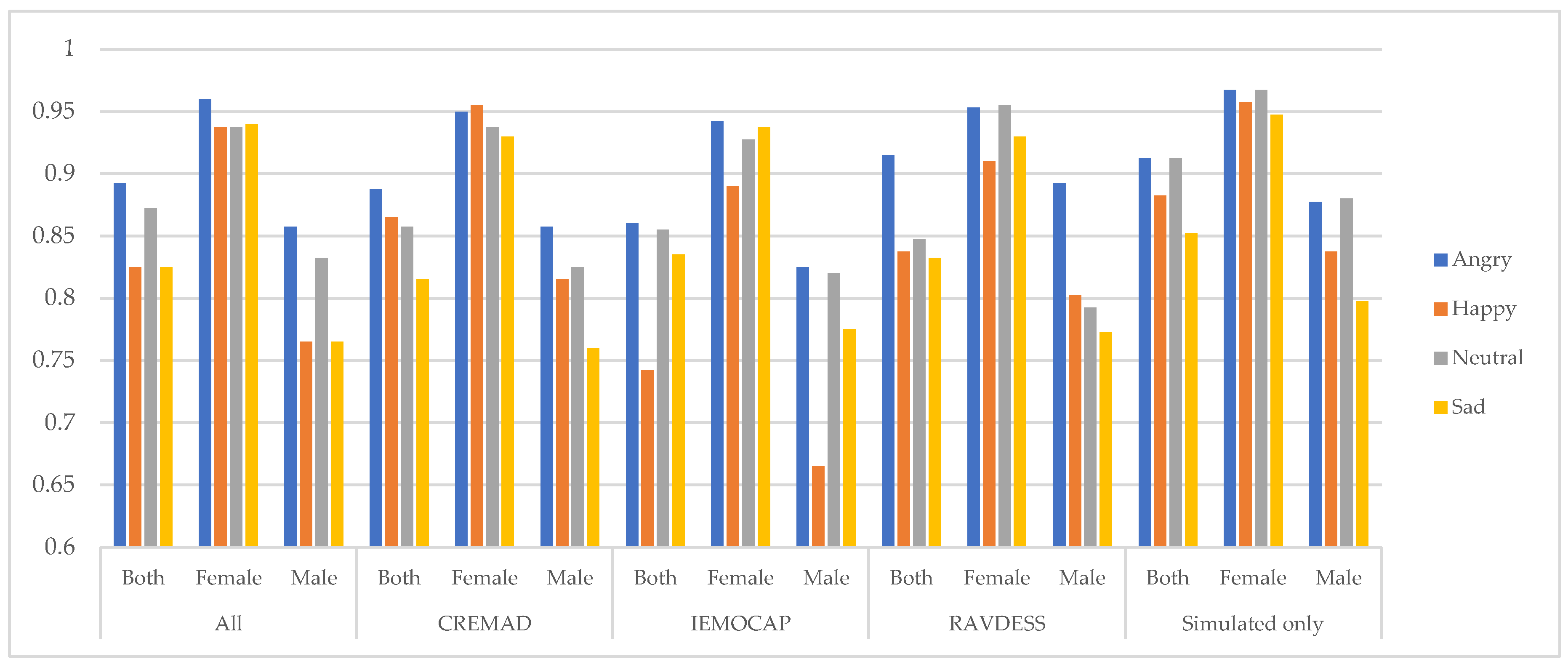

At it has been shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, our proposed data augmentation approach to creating a super corpus is effective in mitigating biases at the emotion level; By integrating this augmented dataset, the overall fidelity of the data has improved significantly. Specifically, the inter-class performance variation, denoted by

where

is effectively minimized.

This indicates that our approach reduces disparities across emotion categories, resulting in a more balanced and robust model performance. The improvement is evident through consistent evaluation metrics, reflecting enhanced model fairness and reliability.

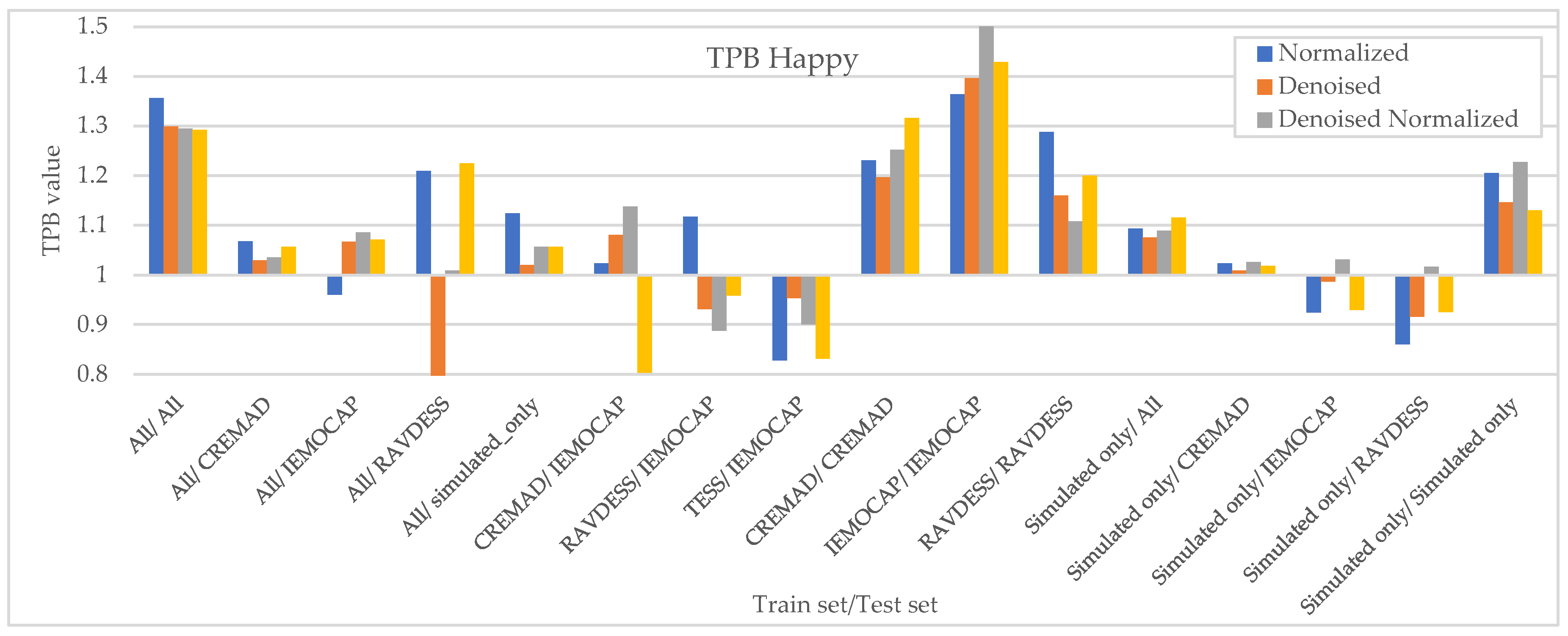

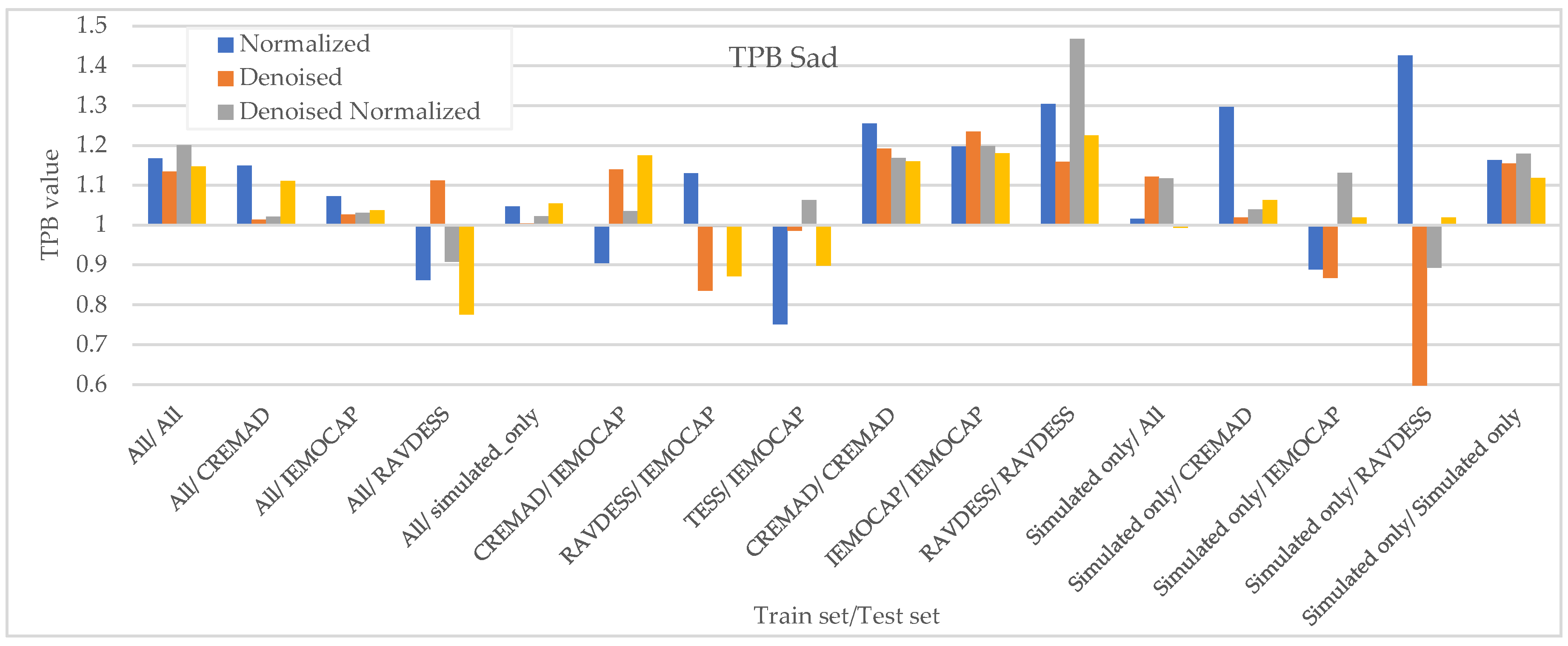

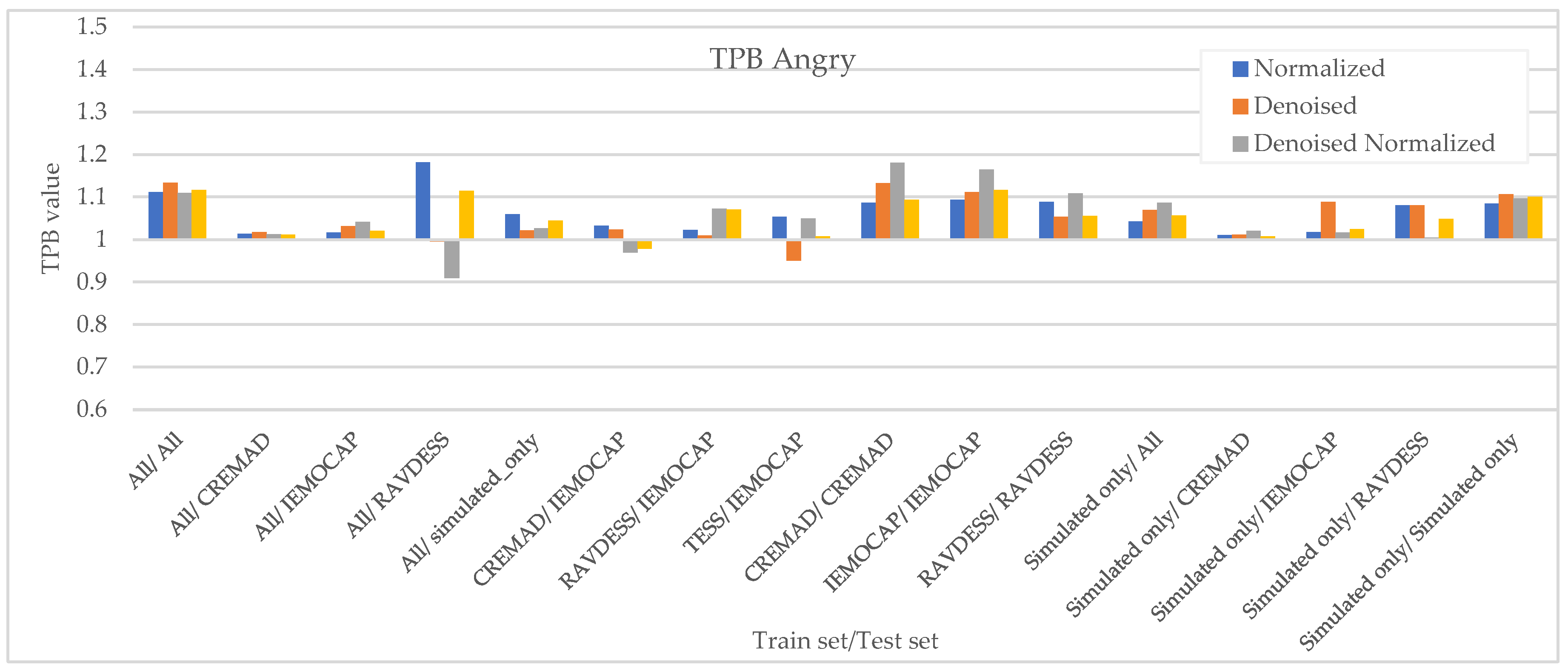

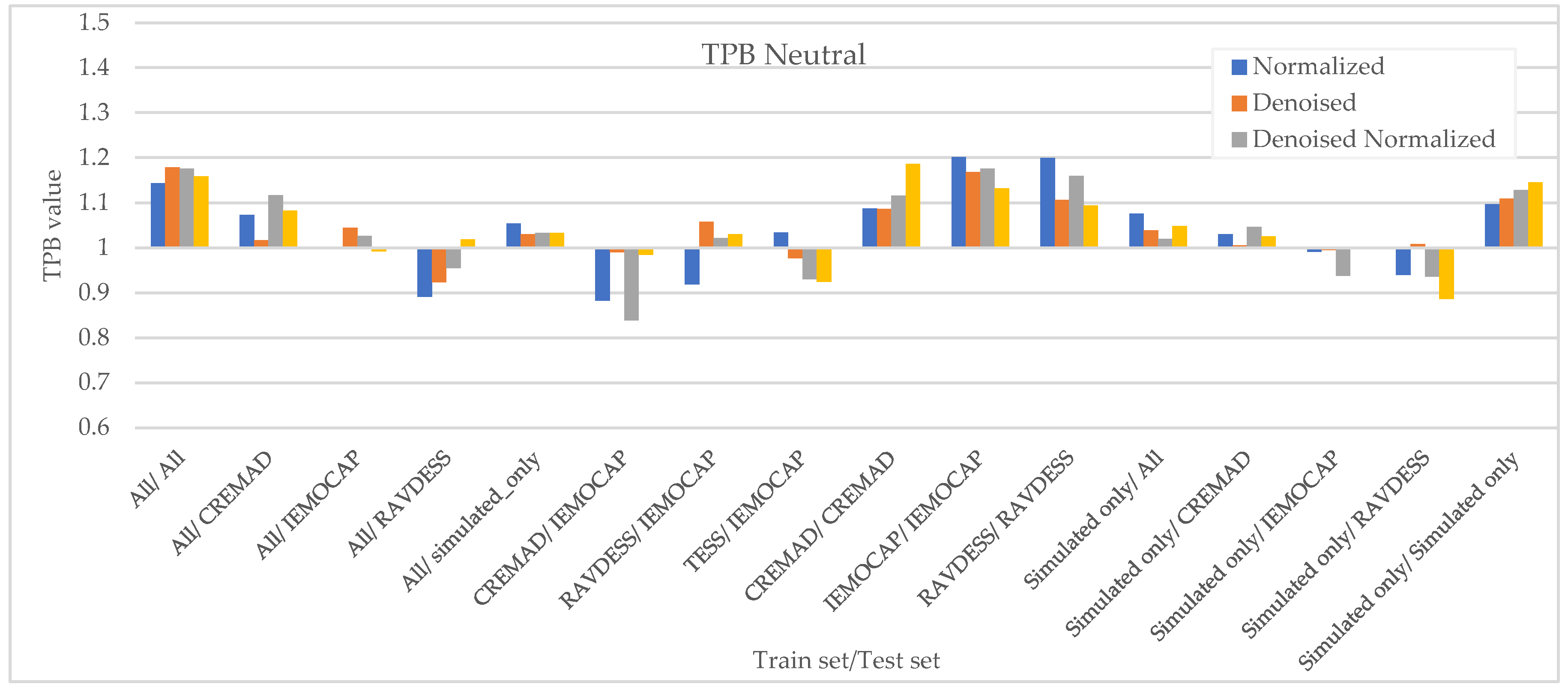

5.3. Downstream Bias

Finally, in this section, we investigate whether downstream biases of best models, as reported in

Section 5.1, vary when trained with individual datasets compared to our augmentation super corpus. To measure downstream biases, we report

for the best model(according to

Table 1) across emotions of our datasets where, as mentioned in

Section 4.3, if a classifier predicts, e.g., “Angry” for a Male speaker much more often than for a Female speaker, the TPR ratio for the “Angry” class is low. TPB = 1 implies an unbiased situation.

As

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate, regardless of preprocessing methods and training datasets, we have witnessed lower TPB (0.85 < TPB < 1.2) for Angry and Neutral emotions compared to Happy and Sad(0.6 < TPB < 1.5). This means our best-performing classifier is transferring bias on Happy and Sad emotions, and the training data has a high impact on the performance of models in Happy and Sad detection. Additionally, as can be found from the reported Figures, different preprocessing approaches, i.e., Denoising, Normalization, or both, cannot shift the bias in models. However, our augmentation approach (Simulated only or All) can effectively shift the bias in the model and push biases in the desired direction and, in some cases, fully de-bias the models, e.g., Simulated only/All.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces a low-cost data augmentation approach for SER systems, addressing critical gaps in their evaluation and performance. Through extensive experiments, we demonstrate that relying solely on F1 score and accuracy metrics provides an incomplete picture of SER systems’ effectiveness. Our findings emphasize the need for a holistic evaluation framework that incorporates additional performance metrics and assesses fairness, robustness, and generalization. This approach highlights limitations in prior work, which often overstate system effectiveness by focusing narrowly on accuracy.

Our analysis reveals that even top-performing models exhibit inconsistent performance across gender groups (Female, Male), struggle with out-of-distribution samples, and show variability when analyzing different emotions within the same dataset distribution. Despite their strong F1 and accuracy metrics, these models continue to reflect biases inherent in the data. Moreover, standard preprocessing methods, such as denoising and normalization, whether used individually or in combination, fail to adequately address these biases.

To tackle these challenges, we introduced a super corpus that significantly augments and diversifies the dataset pool, enabling broader applicability and enhancing robustness in SER models. Additionally, our detailed examination of model robustness in relation to speaker gender and cross-corpora scenarios offers valuable insights into mitigating biases and improving generalization.

Our results further illustrate that the proposed augmentation approach, whether using simulated datasets alone or coupled with preprocessing strategies, effectively reduces or even eliminates bias in some cases, steering the model’s behavior in the desired direction. By demonstrating how our super corpus, when integrated with preprocessing strategies, enhances generalization, mitigates gender bias, and improves robustness to out-of-distribution data samples, we establish a comprehensive foundation for advancing SER systems.

This work not only establishes a strong baseline for future research but also underscores the importance of fairness, robustness, and reliability as essential dimensions of SER system evaluation alongside traditional performance metrics.

References

- Abbaschian, B.; Sierra-Sosa, D.; Elmaghraby, A. Deep Learning Techniques for Speech Emotion Recognition, from Databases to Models. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furey, E.; Blue, J. Alexa, Emotions, Privacy, and GDPR. In Proceedings of the British HCI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, B.; Rigoll, G.; Lang, M. Hidden Markov Model-based Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP, IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Baltimore, MD, USA, 6–9 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, B.; Rigoll, G.; Lang, M. Speech emotion recognition combining acoustic features and linguistic information in a hybrid support vector machine-belief network architecture. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Mao, X.; Chen, L. Speech emotion recognition using deep 1D & 2D CNN LSTM networks. Elsevier Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2019, 47, 312–323. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Liang, R.; Liang, Z.; Huang, C.; Zou, C.; Schüller, B. Speech Emotion Classification Using Attention-Based LSTM. IEEE/Acm Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Englebienne, G.; Truong, K.P.; Evers, V. Towards Speech Emotion Recognition “in the wild” using Aggregated Corpora and Deep Multi-Task Learning. In Proceedings of the Interspeech; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harár, P.; Burget, R.; Dutta, M.K. Speech Emotion Recognition with Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Signal Processing and Integrated Networks (SPIN); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Welling, M. Do we still need models or just more data and compute?” University of Amsterdam, 19. Available online: https://staff.fnwi.uva.nl/m.welling/wp-content/uploads/Model-versus-Data-AI-1.pdf. 20 April.

- Baxter, J. Learning, A Model of Inductive Bias. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2011, 12, 149–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Bengio, Y. Inductive biases for deep learning of higher-level cognition. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2022, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Weninger, F.; Wöllmer, M.; Schüller, B. Unsupervised learning in cross-corpus acoustic emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, B.; Arsic, D.; Rigoll, G.; Wimmer, M. ; Radig Audiovisual Behavior Modeling by Combined Feature Spaces. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Acoustics, 2007., Speech and Signal Processing - ICASSP ’07.

- Schüller, B.; Müller, R.; Eyben, F.; Gast, J.; Hörnler, B.; Wöllmer, M.; Rigoll, G.; Höthker, A.; Konosu, H. , "Being bored? Recognising natural interest by extensive audiovisual integration for real-life application. Image Vis. Comput. 2009, 27, 1760–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engberg, I.S.; Hansen, A.V.; Andersen, O.; Dalsgaard, P. Design, recording, and verification of a Danish emotional speech database. In Proceedings of the EUROSPEECH, Rhodes, Greece; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, O.; Kotsia, I.; Macq, B.M.; Pitas, I. The eNTERFACE’05 Audio-Visual Emotion Database. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Data Engineering Workshops (ICDEW’06); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas-Cowie, E.; Cowie, R.; Sneddon, I.; Cox, C.; Lowry, O.; McRorie, M.; Devillers, L.; Abrilian, S.; Batliner, A.; Amir, N.; Karpouzis, K.; Martin, J.-C. The HUMAINE database: Addressing the collection and annotation of naturalistic and induced emotional data. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction, Lisbon, Portugal; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, M.; Kroschel, K.; Narayanan, S. The Vera am Mittag German audio-visual emotional speech database. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Hannover, Germany; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, R.; Jalal, M.A.; Ng, R.W.M.; Hain, T. A Cross-Corpus Study on Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU); 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zehra, W.; Javed, A.R.; Jalil, Z.; Khan, H.U.; Gadekallu, T.R. Cross corpus multi-lingual speech emotion recognition using ensemble learning. Complex Intell. Syst. 2021, 7, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.J.; Haq, S. Surrey Audio-Visual Expressed Emotion (SAVEE) Database; University of Surrey: Guildford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, S.; Qayyum, A.; Usman, M.; Qadir, J. Cross Lingual Speech Emotion Recognition: Urdu vs. In Western Languages. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, F.; Paeschke, A.; Rolfes, M.; Sendlmeier, W.F.; Weiss, B. A database of German emotional speech. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH, Lisbon, Portugal; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Costantini, G.; Iaderola, I.; Paoloni, A.; Todisco, M. EMOVO Corpus: an Italian Emotional Speech Database. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’14), Reykjavik, Iceland, May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eyben, F.; Scherer, K.R.; Schüller, B.W.; Sundberg, J.; André, E.; Busso, C.; Devillers, L.Y.; Epps, J.; Laukka, P.; Narayanan, S.S.; Truong, K.P. The Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set (GeMAPS) for Voice Research and Affective Computing. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2016, 7, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunschweiler, N.; Doddipatla, R.; Keizer, S.; Stoyanchev, S. A Study on Cross-Corpus Speech Emotion Recognition and Data Augmentation. Cartagena, Colombia, 2021.

- Busso, C.; Bulut, M.; Lee, C.-C.; Kazemzadeh, A.; Mower, E.; Kim, S.; Chang, J.N.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S.S. IEMOCAP: Interactive emotional dyadic motion capture database. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2008, 42, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.R.; Russo, F.A. The Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song (RAVDESS): A dynamic, multimodal set of facial and vocal expressions in North American English. PLoS ONE 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadeh, A.; Liang, P.P.; Poria, S.; Vij, P.; Cambria, E.; Morency, L.-P. Multi-attention recurrent network for human communication comprehension. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Latif, S.; Rana, R.; Khalifa, S.; Jurdak, R.; Schüller, B. Self-Supervised Adversarial Domain Adaptation for Cross-Corpus and Cross-Language Speech Emotion Recognition. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Rauchenstein, L.; Eisenberg, J.D.; Howell, N. Artie Bias Corpus: An Open Dataset for Detecting Demographic Bias in Speech Applications. In Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC Marseille, 2020.

- Feng, S.; Kudina, O.; Halpern, B.M.; Scharenborg, O. Quantifying Bias in Automatic Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Picheny, M.; Sarı, L.; Chitkara, P.; Xiao, A.; Zhang, X.; Chou, M.; Alvarado, A. Towards Measuring Fairness in Speech Recognition: Casual Conversations Dataset Transcriptions. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Steidl, S. Automatic Classification of Emotion-Related User States in Spontaneous Children’s Speech. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, I.; McRorie, M.; McKeown, G.; Hanratty, J. The Belfast induced natural emotion database. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnjatovic, M.; Rosner, D. Inducing Genuine Emotions in Simulated Speech-Based Human-Machine Interaction: The NIMITEK Corpus. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2010, 1, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, K.; Pichora-Fuller, M.K. Recognition of emotional speech for younger and older talkers: Behavioural findings from the Toronto emotional speech set. Can. Acoust. Acoust. Can. 2011, 39, 182–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Cooper, D.G.; Keutmann, M.; Gur, R.; Nenkova, A.; Verma, R. CREMA-D: Crowd-sourced emotional multimodal actors dataset. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2014, 5, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childers, D.G.; Wu, K. Gender recognition from speech. Part II: Fine analysis. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991, 90, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Arteaga, M.; Romanov, A.; Wallach, H.; Chayes, J.; Borgs, C.; Chouldechova, A.; Geyik, S.; Kenthapadi, K.; Kalai, A.T. Bias in Bios: A Case Study of Semantic Representation Bias in a High-Stakes Setting. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, 2019., and Transparency (ACM FAT*).

- Steed, R.; Panda, S.; Kobren, A.; Wick, M. Upstream Mitigation Is Not All You Need: Testing the Bias Transfer Hypothesis in Pre-Trained Language Models. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, T.M.; Gunawan, T.S.; Qadri, S.A.A.; Mansor, H.; Kartiwi, M.; Ismail, N. Speech Emotion Recognition using Convolution Neural Networks and Deep Stride Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference on Wireless and Telematics (ICWT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Darekara, R.V.; Dhande, A.P. Emotion recognition from Marathi speech database using adaptive artificial neural network. Biol. Inspired Cogn. Archit. 2018, 25, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Yu, D.; Tashev, I. Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Neural Network and Extreme Learning Machine. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, T.; Kawahara, T. Improved End-to-End Speech Emotion Recognition Using Self Attention Mechanism and Multitask Learning. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2019: Training Strategy for Speech Emotion Recognition; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mekruksavanich, S.; Jitpattanakul, A.; Hnoohom, N. Negative Emotion Recognition using Deep Learning for Thai Language. In Proceedings of the Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Pattaya, Thailand, 2020., Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON).

- Mirsamadi, S.; Barsoum, E.; Zhang, C. Automatic speech emotion recognition using recurrent neural networks with local attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), New Orleans, LA; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, S.; Gupta, R.; Espy-Wilson, C. On Enhancing Speech Emotion Recognition Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Interspeech 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.; Rana, R.; Qadir, J.; Epps, J. Variational Autoencoders for Learning Latent Representations of Speech Emotion: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chatziagapi, A.; Paraskevopoulos, G.; Sgouropoulos, D.; Pantazopoulos, G.; Nikandrou, M.; Giannakopoulos, T.; Katsamanis, A.; Potamianos, A.; Narayanan, S. Data Augmentation Using GANs for Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2019: Speech Signal Characterization 1, Graz, Austria; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eskimez, S.E.; Duan, Z.; Heinzelman, W. Unsupervised Learning Approach to Feature Analysis for Automatic Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, 2018., Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).