Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

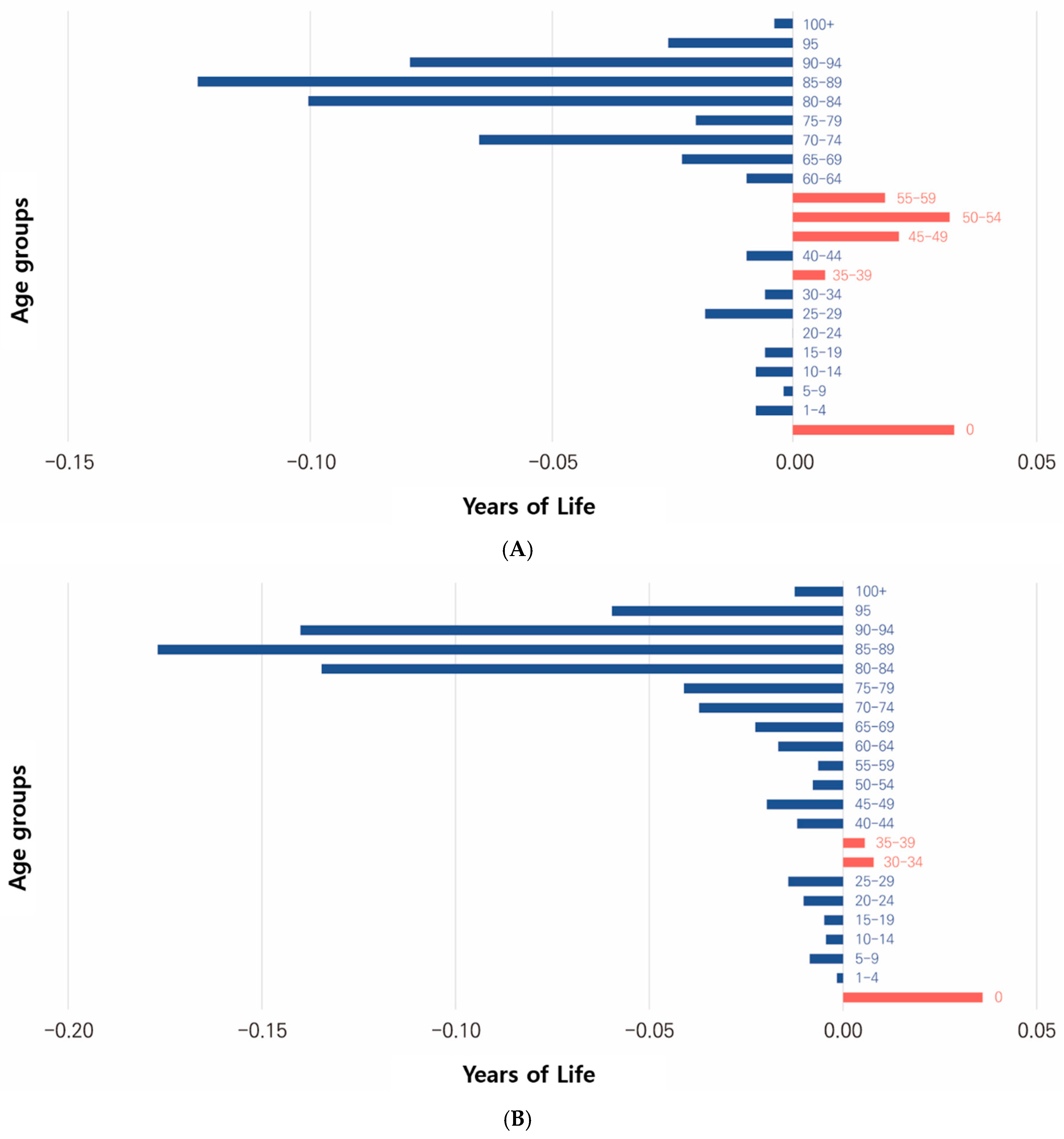

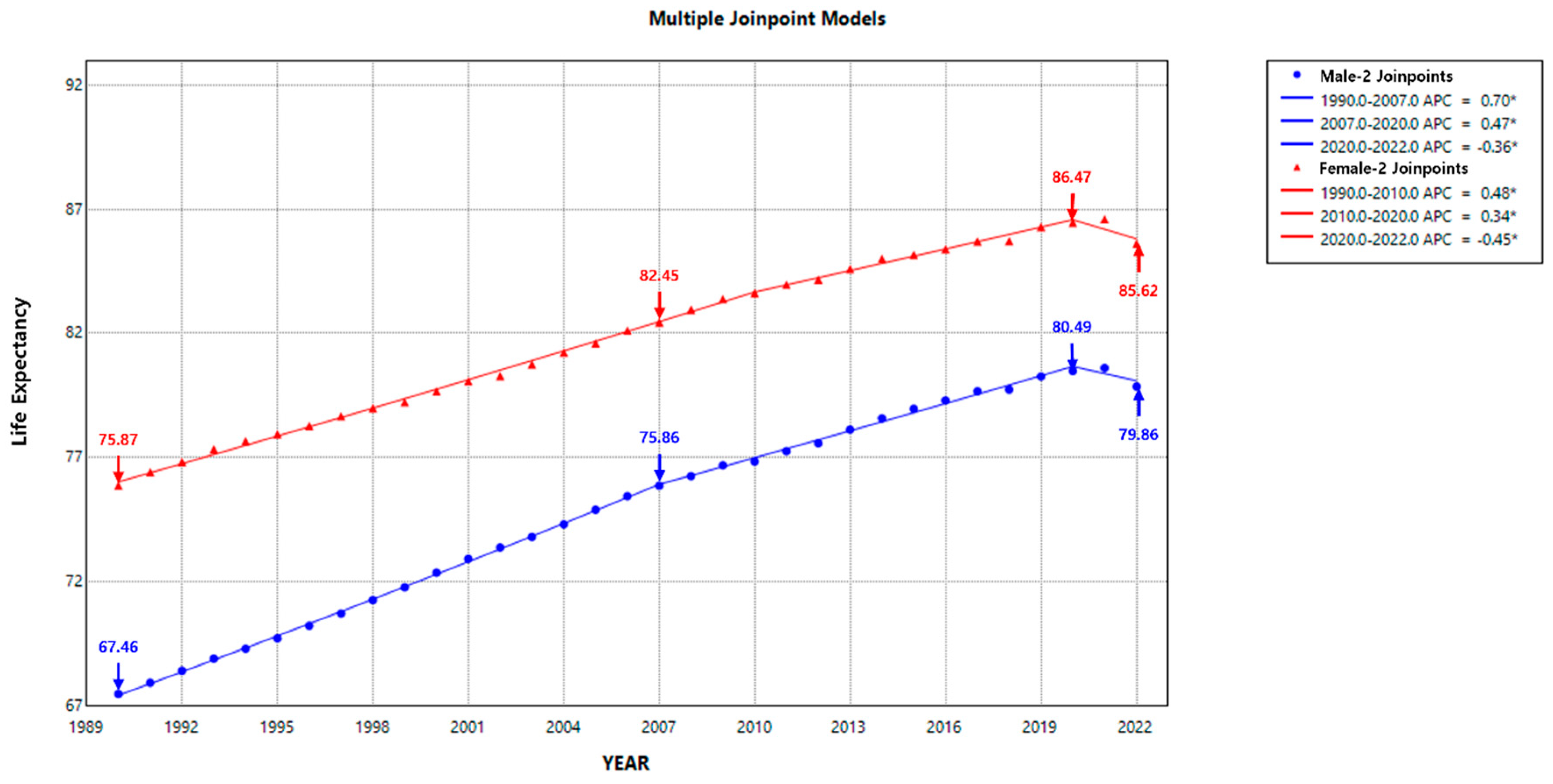

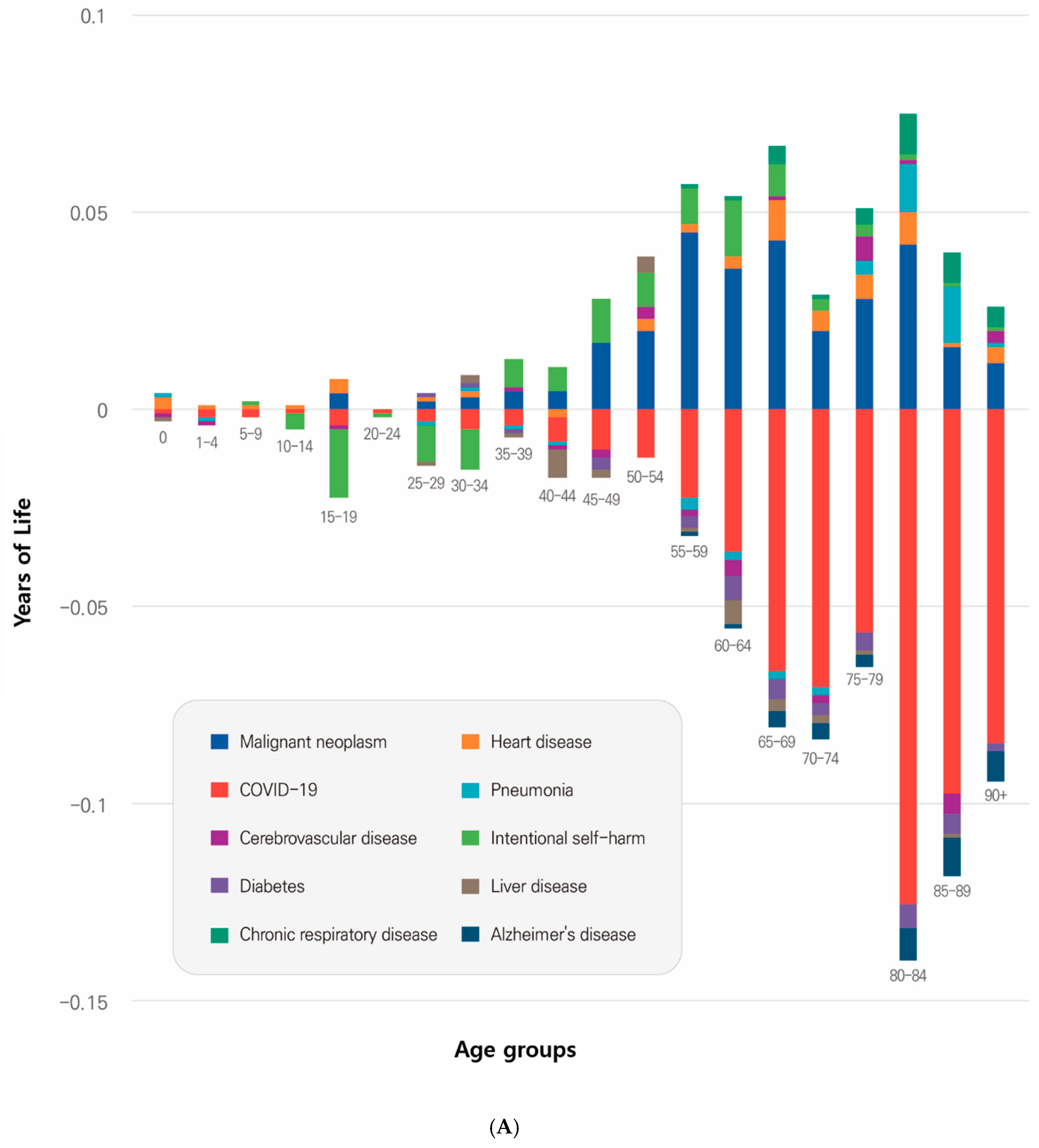

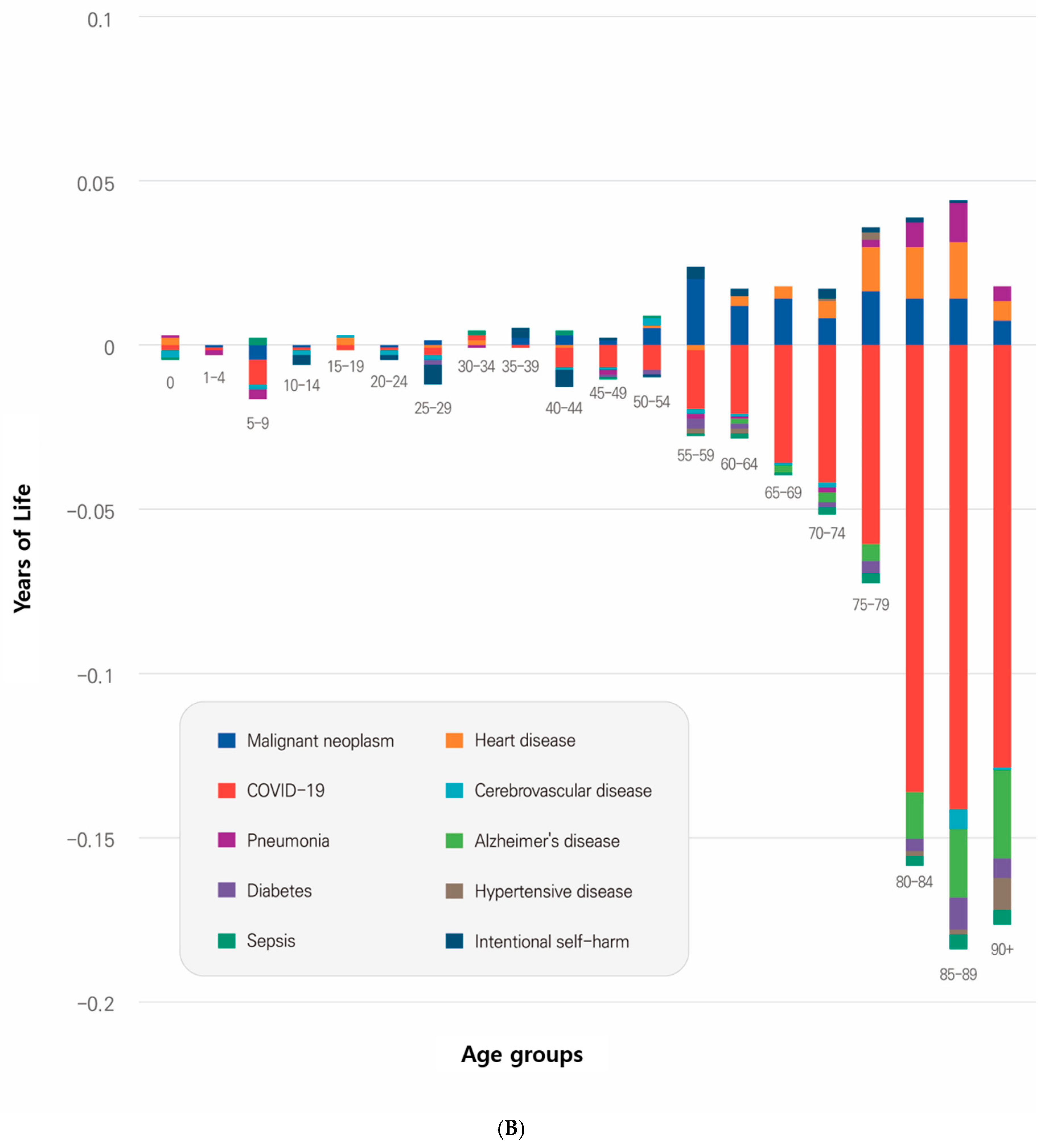

This study investigated changes in life expectancy due to the COVID-19 pandemic by analyzing the contributions of age, gender, and cause of death in 2019 and 2022. Korea’s simplified life table and cause-of-death statistics from 2019 to 2022 were used to assess mortality changes by age, gender, and cause of death during the pandemic. Joinpoint regression analysis was applied to detect trends, and the Arriaga decomposition method was used to quantify the contributions of age, gender, and cause of death to life expectancy changes. Joinpoint regression identified a slow increase in life expectancy in 2007 and a decline in 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. Life expectancy decreased markedly for men (-0.36 years per year, 95%CI: -0.68 to -0.03) and women (-0.45 years per year, 95%CI: -0.71 to -0.18). Age-specific contributions revealed declines across age groups, with the steepest reductions in the older population (80 years or older: -0.35 years for men; -0.52 years for women). Women (-0.68 years) contributed more to the decline in life expectancy than men (-0.41 years). COVID-19 ranked as the third leading cause of death in 2022, significantly contributing to the decline in life expectancy among the older population (aged 80 years or older: -0.306 years for men, -0.408 years for women). Women in Korea were more affected than men, reducing the gender gap in life expectancy by 0.3 years. Before the pandemic, non-communicable diseases such as malignant neoplasms, heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease dominated Korea’s top 10 causes of death. During the pandemic, however, COVID-19 rose to third place by 2022. Notably, intentional self-harm (suicide) contributed to an increase in life expectancy, suggesting shifts in the relative impact of various causes of death.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Demographic and Epidemiological Datasets

2.2. Decomposing Life Expectancy Changes

3. Results

3.1. Life Expectancy Trends in Korea

3.2. Contributions to Life Expectancy by Age and Gender

3.3. Contributions to Life Expectancy by Age and Gender

4. Discussion

Acknowledgments

References

- Riley JC. Estimates of regional and global life expectancy, 1800–2001. Popul Dev Rev. 2005;31: 537–543. [CrossRef]

- Schöley J, Aburto JM, Kashnitsky I, Kniffka MS, Zhang L, Jaadla H, et al. Life expectancy changes since COVID-19. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6: 1649–1659. [CrossRef]

- Hong J, Yi S, Yoon T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy by the level of area deprivation in South Korea. Front Public Health. 2023;11: 1215914. [CrossRef]

- Cao G, Liu J, Liu M, Liang W. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy at birth at the global, regional, and national levels: A joinpoint time-series analysis. J Glob Health. 2023;13: 06042. [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org.

- Mo Y, Feng Q, Gu D. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy at birth in Asia. BMC Public Health. 2023;23: 1508. [CrossRef]

- Munira MS, Okada Y, Nishiura H. Life-expectancy changes during the COVID-19 pandemic from 2019–2021: estimates from Japan, a country with low pandemic impact. PeerJ. 2023;11: e15784. [CrossRef]

- Islam N, Jdanov DA, Shkolnikov VM, Khunti K, Kawachi I, White M, et al. Effects of Covid-19 pandemic on life expectancy and premature mortality in 2020: time series analysis in 37 countries. BMJ. 2021;375: e066768. [CrossRef]

- Woolf SH, Masters RK, Aron LY. Changes in life expectancy between 2019 and 2020 in the US and 21 peer countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e227067. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global excess deaths associated with COVID19, January 2020 - December 2021; 2022.

- World Health Organization. Methods for estimating the excessive mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic; 2022.

- Aburto JM, Kashyap R, Schöley J, Angus C, Ermisch J, Mills MC, et al. Estimating the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality, life expectancy and lifespan inequality in England and Wales: a population level analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75: 735-740. [CrossRef]

- Aburto JM, Schöley J, Kashnitsky I, Zhang L, Rahal C, Missov TI, et al. Quantifying impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic through life-expectancy losses: a population-level study of 29 countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51: 63-74. [CrossRef]

- Castro MC, Gurzenda S, Turra CM, Kim S, Andrasfay T, Goldman N. Reduction in life expectancy in Brazil after COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27: 1629-1635. [CrossRef]

- Chan EYS, Cheng D, Martin J. Impact of COVID-19 on excess mortality, life expectancy, and years of life lost in the United States. PLOS ONE. 2021;16: e0256835. eCollection 2021. [CrossRef]

- Heuveline P. Global and national declines in life expectancy: an End-of-2021 assessment. Popul Dev Rev. 2022;48: 31-50. [CrossRef]

- Trias-Llimós S, Riffe T, Bilal U. Monitoring life expectancy levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: example of the unequal impact of the frst wave on Spanish regions. PLOS ONE. 2020;15: e0241952. eCollection 2020 . [CrossRef]

- Masters RK, Woolf SH, Aron LY. Age -specifc mortality during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and life expectancy changes in the United States and peer countries, 1980–2020. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77 Supplement 2(Suppl_2):S 127-S137: S127–S137. [CrossRef]

- Woolf SH, Masters RK, Aron LY. Effect of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 on life expectancy across populations in the USA and other high income countries: simulations of provisional mortality data. BMJ. 2021;373:n 1343: 1343. [CrossRef]

- Huang G, Guo F, Zimmermann KF, Liu L, Taksa L, Cheng Z, et al. The effect of the COVID 19 pandemic on life expectancy in 27 countries. Sci Rep. 2023;13: 8911. [CrossRef]

- Strozza C, Vigezzi S, Callaway J, Aburto JM. The impact of COVID-19 on life expectancy across socioeconomic groups in Denmark. Popul Health Metr. 2024;22: 3. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 eliminated a decade of progress in global level of life expectancy, NEW, 24 May 2024; 2024.

- Masters RK, Aron LY, Woolf SH. Life expectancy changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2019-2021: highly racialized deaths in young and middle adulthood in the United States as compared with other high-income countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2024;193: 26-35. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute, Joinpoint Regression Program. version 4.8.0.1. Internet. Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute; https :. Available from: surveillance.cancer.gov/ joinpoint /.

- Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19: 335-351. [CrossRef]

- Tools of the trade: cancer trend analysis using joinpoint regression, Part 1 – The basics.

- Arriaga EE. Measuring and explaining the change in life expectancies. Demography. 1984;21: 83-96. [CrossRef]

- Lim DO, Yoo YH. Patterns and changes in life expectancy in Korea, 1990-2020. J Health Info Stat. 2024;49: 70-78. [CrossRef]

- Ciarambino T, Para O, Giordano M. Immune system and COVID-19 by sex differences and age. Womens Health (Lond). 2021;17: 17455065211022262. [CrossRef]

- Korean social trends 2022, Statistics Korea, statistics Research Institute.

- GBD. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403: 2133-2161. [CrossRef]

- Kuehn BM. COVID-19 cuts life expectancy in dozens of countries. JAMA. 2022;327: 209. [CrossRef]

- Hajdu T, Krekó J, Tóth CG. Inequalities in regional excess mortality and life expectancy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Sci Rep. 2024;14: 3835. [CrossRef]

- Aburto JM, Kashyap R, Schöley J, Angus C, Ermisch J, Mills MC, et al. Estimating the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality, life expectancy and lifespan inequality in England and Wales: a population-level analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75: 735-740. [CrossRef]

- Urashima M, Tanaka E, Ishihara H, Akutsu T. Association between life expectancy at age 60 years before the COVID-19 pandemic and excess mortality during the pandemic in aging countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e2237528. [CrossRef]

| Age (y) | Male | Female | Male - Female | ||

| 0 | 0.035 | 8.51% | 0.036 | 5.29% | -0.001 |

| 1–4 | -0.008 | -1.89% | -0.002 | -0.23% | -0.006 |

| 5–9 | -0.002 | -0.51% | -0.009 | -1.26% | 0.007 |

| 10–14 | -0.008 | -1.96% | -0.004 | -0.65% | -0.004 |

| 15–19 | -0.006 | -1.41% | -0.005 | -0.71% | -0.001 |

| 20–24 | 0.000 | -0.08% | -0.010 | -1.49% | 0.01 |

| 25–29 | -0.019 | -4.58% | -0.014 | -2.07% | -0.005 |

| 30–34 | -0.006 | -1.49% | 0.008 | 1.16% | -0.014 |

| 35–39 | 0.007 | 1.68% | 0.006 | 0.82% | 0.001 |

| 40–44 | -0.010 | -2.48% | -0.012 | -1.74% | 0.002 |

| 45–49 | 0.023 | 5.55% | -0.020 | -2.89% | 0.043 |

| 50–54 | 0.034 | 8.25% | -0.008 | -1.14% | 0.042 |

| 55–59 | 0.020 | 4.78% | -0.006 | -0.94% | 0.026 |

| 60–64 | -0.010 | -2.49% | -0.017 | -2.46% | 0.007 |

| 65–69 | -0.024 | -5.80% | -0.023 | -3.32% | -0.001 |

| 70–74 | -0.068 | -16.46% | -0.037 | -5.46% | -0.031 |

| 75–79 | -0.021 | -4.99% | -0.041 | -6.03% | 0.02 |

| 80–84 | -0.105 | -25.44% | -0.135 | -19.76% | 0.03 |

| 85–89 | -0.129 | -31.30% | -0.177 | -25.97% | 0.048 |

| 90–94 | -0.083 | -20.25% | -0.140 | -20.56% | 0.057 |

| 95-99 | -0.027 | -6.64% | -0.060 | -8.76% | 0.033 |

| 100+ | -0.004 | -1.01% | -0.012 | -1.83% | 0.008 |

| Total | -0.412 | -100.00% | -0.681 | -100.00% | 0 .269 |

| male | C00-C97 | I20–I51 | U07.1, U07.2, U10 | J12–J18 | I60–I69 | X60–X84 | E10–E14 | K70–K76 | J40–J47 | G30 | Other |

| 0 | 0.000 | 0.003 | -0.001 | 0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.034 |

| 1–4 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.002 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.005 |

| 5–9 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.002 |

| 10–14 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.004 |

| 15–19 | 0.004 | 0.004 | -0.004 | 0.000 | -0.001 | -0.017 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| 20–24 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| 25–29 | 0.002 | 0.001 | -0.003 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.009 | 0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.009 |

| 30–34 | 0.003 | 0.002 | -0.005 | 0.001 | 0.000 | -0.010 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 35–39 | 0.005 | 0.000 | -0.004 | -0.001 | 0.001 | 0.007 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| 40–44 | 0.005 | -0.002 | -0.006 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.006 | 0.000 | -0.007 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.004 |

| 45–49 | 0.017 | 0.000 | -0.010 | 0.000 | -0.002 | 0.011 | -0.003 | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

| 50–54 | 0.020 | 0.003 | -0.012 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.007 |

| 55–59 | 0.045 | 0.002 | -0.022 | -0.003 | -0.002 | 0.009 | -0.003 | -0.001 | 0.001 | -0.001 | -0.004 |

| 60–64 | 0.036 | 0.003 | -0.036 | -0.002 | -0.004 | 0.014 | -0.006 | -0.006 | 0.001 | -0.001 | -0.010 |

| 65–69 | 0.043 | 0.010 | -0.066 | -0.002 | 0.001 | 0.008 | -0.005 | -0.003 | 0.005 | -0.004 | -0.011 |

| 70–74 | 0.020 | 0.005 | -0.070 | -0.002 | -0.002 | 0.003 | -0.003 | -0.002 | 0.001 | -0.004 | -0.016 |

| 75–79 | 0.028 | 0.006 | -0.056 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.003 | -0.005 | -0.001 | 0.004 | -0.003 | -0.007 |

| 80–84 | 0.042 | 0.008 | -0.125 | 0.012 | 0.001 | 0.002 | -0.006 | 0.000 | 0.010 | -0.008 | -0.040 |

| 85–89 | 0.016 | 0.001 | -0.097 | 0.014 | -0.005 | 0.001 | -0.005 | -0.001 | 0.008 | -0.010 | -0.317 |

| 90 + | 0.012 | 0.004 | -0.084 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.005 | -0.008 | -0.047 |

| Total | 0.299 | 0.053 | -0.605 | 0.019 | -0.003 | 0.035 | -0.038 | -0.020 | 0.035 | -0.040 | -0.414 |

| Female | C00–C97 | I20–I51 | U07.1, U07.2, U10 | I60–I69 | J12–J18 | G30 | E10–E14 | I10–I13 | A40–41 | X60–X84 | Other |

| 0 | 0.000 | 0.002 | -0.002 | -0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.037 |

| 1–4 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| 5–9 | -0.005 | 0.000 | -0.007 | -0.002 | -0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.008 |

| 10–14 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.003 | 0.000 |

| 15–19 | 0.000 | 0.002 | -0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.005 |

| 20–24 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.002 | -0.005 |

| 25–29 | 0.001 | -0.001 | -0.002 | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.006 | -0.004 |

| 30–34 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| 35–39 | 0.002 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | -0.001 |

| 40–44 | 0.003 | -0.001 | -0.006 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.005 | -0.003 |

| 45–49 | 0.001 | 0.000 | -0.007 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.001 | -0.011 |

| 50–54 | 0.005 | 0.001 | -0.008 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | -0.001 | -0.006 |

| 55–59 | 0.020 | -0.002 | -0.018 | -0.001 | -0.002 | 0.000 | -0.003 | -0.001 | -0.001 | 0.004 | -0.003 |

| 60–64 | 0.012 | 0.003 | -0.021 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.001 | -0.002 | -0.001 | -0.002 | 0.002 | -0.006 |

| 65–69 | 0.014 | 0.004 | -0.036 | -0.001 | 0.000 | -0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 70–74 | 0.008 | 0.005 | -0.042 | -0.002 | -0.001 | -0.003 | -0.002 | 0.001 | -0.002 | 0.003 | -0.002 |

| 75–79 | 0.016 | 0.014 | -0.061 | 0.000 | 0.002 | -0.005 | -0.004 | 0.002 | -0.003 | 0.002 | -0.004 |

| 80–84 | 0.014 | 0.016 | -0.137 | 0.000 | 0.007 | -0.014 | -0.004 | -0.001 | -0.003 | 0.002 | -0.015 |

| 85–89 | 0.014 | 0.017 | -0.142 | -0.006 | 0.012 | -0.021 | -0.010 | -0.001 | -0.005 | 0.001 | -0.448 |

| 90 + | 0.007 | 0.006 | -0.129 | -0.001 | 0.005 | -0.027 | -0.006 | -0.010 | -0.004 | 0.000 | -0.054 |

| Total | 0.110 | 0.067 | -0.621 | -0.018 | 0.017 | -0.072 | -0.032 | -0.010 | -0.021 | 0.001 | -0.518 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).