1. Introduction

Antimicrobial medication is commonly administered to food-producing animals, with approximately 80% of them receiving such treatment at some point in their lives (Lee et al., 2001). Livestock and poultry farmers utilize antimicrobials to promote animal growth, improve feed efficiency, and maintain animal health.

Among the antimicrobials used in veterinary medicine, fluoroquinolones stand out because they are classified amongst the “highest priority critically important antimicrobials” (HPCIA) (WOAH, 2021, WHO, 2018). This classification underscores their significance not only in veterinary medicine but also in human medicine.

These synthetic antibiotics are particularly valued for their broad spectrum of activity against a range of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, making them versatile tools in treating infections that can affect livestock and poultry. They are utilized in managing several types of infections commonly encountered in food animals. For instance, they are frequently prescribed for respiratory infections, which can significantly impact animal health and productivity. Additionally, these drugs are effective against urinary tract infections and gastrointestinal infections, conditions that can lead to severe morbidity if left untreated (Gajda et al., 2012, Prajapati et al., 2018, Herrera-Herreraa et al., 2011). Their cost-effectiveness further contributes to their popularity among farmers who seek to maximize production while minimizing costs (Martins et al., 2015).

Unfortunately, there is a growing trend of self-prescription and sale of these antimicrobials without adequate medical oversight in various regions worldwide (Collignon et al., 2019). The overuse or misuse of fluoroquinolones in food animals can contribute to the development of resistant bacterial strains, posing a threat to both animal and human health. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a significant global threat and has the potential to become the next pandemic (Akram et al., 2023). According to O’Neil (2016), AMR is responsible for 700,000 deaths annually, and this number is projected to escalate to 10 million deaths per year by 2050. Resistance to one fluoroquinolone can lead to resistance to the entire class of antimicrobials, as well as cross-resistance to other antibiotics. This phenomenon increases the risks of treatment failure due to the application of an ineffective antibiotic, and complicates efforts to control and contain antimicrobial resistance (WHO, 1998).

The protection of public health against probable harmful effects of veterinary drugs has been a main concern for the drug regularity authorities. In some developed countries regulatory frameworks have been established to mitigate these risks. For instance, the European Union’s Regulation No. 2377/90 sets maximum residue limits (MRLs) for various veterinary drugs, including fluoroquinolones, in food products derived from animals such as poultry, beef, pork, and milk (Mahmood et., 2016). Maximum residue limits refer to the maximum concentration of residues legally acceptable in food or animal feed standards to ensure the safety of food products for consumers (CAC, 2011, Jayalakshmi et al., 2017). These regulations aim to ensure that any residues present in food do not pose a risk to consumer health. Conversely, many developing countries face challenges related to the regulation of veterinary antibiotics. In these regions, access to veterinary drugs may be largely unregulated, leading to practices such as overdosing or inappropriate use among farmers and veterinarians (Baazize-Ammi et al., 2019). This lack of oversight can result in higher concentrations of antibiotic residues in animal products and contribute to the emergence of AMR due to selective pressure exerted by sub-therapeutic doses or misuse of antibiotics.

In recognition of the concerns regarding fluoroquinolone contamination in food products from animal origin, a systematic review was conducted. The primary aim of the review was to determine the concentration of fluoroquinolones in livestock and poultry products. The specific objectives included assessing whether the concentrations detected were above the minimum threshold to cause harm and calculating the prevalence of the residues. By synthesizing data from multiple studies, the review sought to identify patterns regarding the presence of fluoroquinolones in different countries in the food animal products. Furthermore, by calculating the prevalence of fluoroquinolone residues across different types of animal-derived foods, the review provided an overview of the extent to which these fluoroquinolones are present in the food supply chain. The data generated from this review can provide valuable insights on the management of fluoroquinolones in food animals globally and assist in analyzing the effectiveness of established regulatory policies that control their presence in food products.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Review Protocol and Literature Search.

A systematic review was conducted aiming to summarize studies reporting on the concentrations of fluoroquinolones in beef, pork, poultry meat, milk, and eggs. The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Relevant articles were sought through a search of three bibliographic databases, including Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus. The search phrase used was “(fluoroquinolones OR fluoroquinolone OR enrofloxacin OR ciprofloxacin) AND (concentration) AND (egg OR eggs OR milk OR cattle OR beef OR poultry OR chicken OR pig OR pigs OR pork)”. The inclusion criteria focused on articles published in English between January 2000 and December 2022.

2.2. Data Screening

To provide rapid access of the literature reviewed and manage the citations retrieved from the databases, all publications were imported into the Endnote 20.5 reference management software. This software was also used to remove duplicate entries. To verify its accuracy, the references were cross checked manually. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were screened independently by T.V against a set of exclusion criteria which included (i) studies describing different antimicrobials other than fluoroquinolones (ii) studies focusing on validation of methods (method trials) (iii) different food samples apart from beef, pork, milk, poultry meat and eggs. Following the initial screening level, full texts of the citations considered relevant were retained for further assessment of eligibility. During the full text screening stage, the exclusion criteria which resulted in elimination of articles included: (i) failure to report concentration of the detected fluoroquinolones (ii) lack of access to full texts (iii) non-original information i.e., review articles. The reference lists of the selected articles were further explored to identify any additional relevant studies meeting the eligibility criteria. This step aimed to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data from the selected articles were extracted and summarized into a Microsoft Excel sheet. The publications were broadly classified by the animal food product and further categorized regarding the country where the research took place, year of publishing, fluoroquinolone detected and concentration.

3. Statistical Analysis

The extracted data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism version 8.4.2. Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize the main findings of the included studies focusing on parameters including the mean concentration of the fluoroquinolones and their prevalence in the various food matrices. As the normality assumptions were not met, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test for differences between the prevalence of the fluoroquinolones among the samples. Differences between groups were regarded as significant at P < 0.05. The graphs and tables were generated using Graph Pad Prism and Microsoft Excel.

4. Results

4.1. Search Results

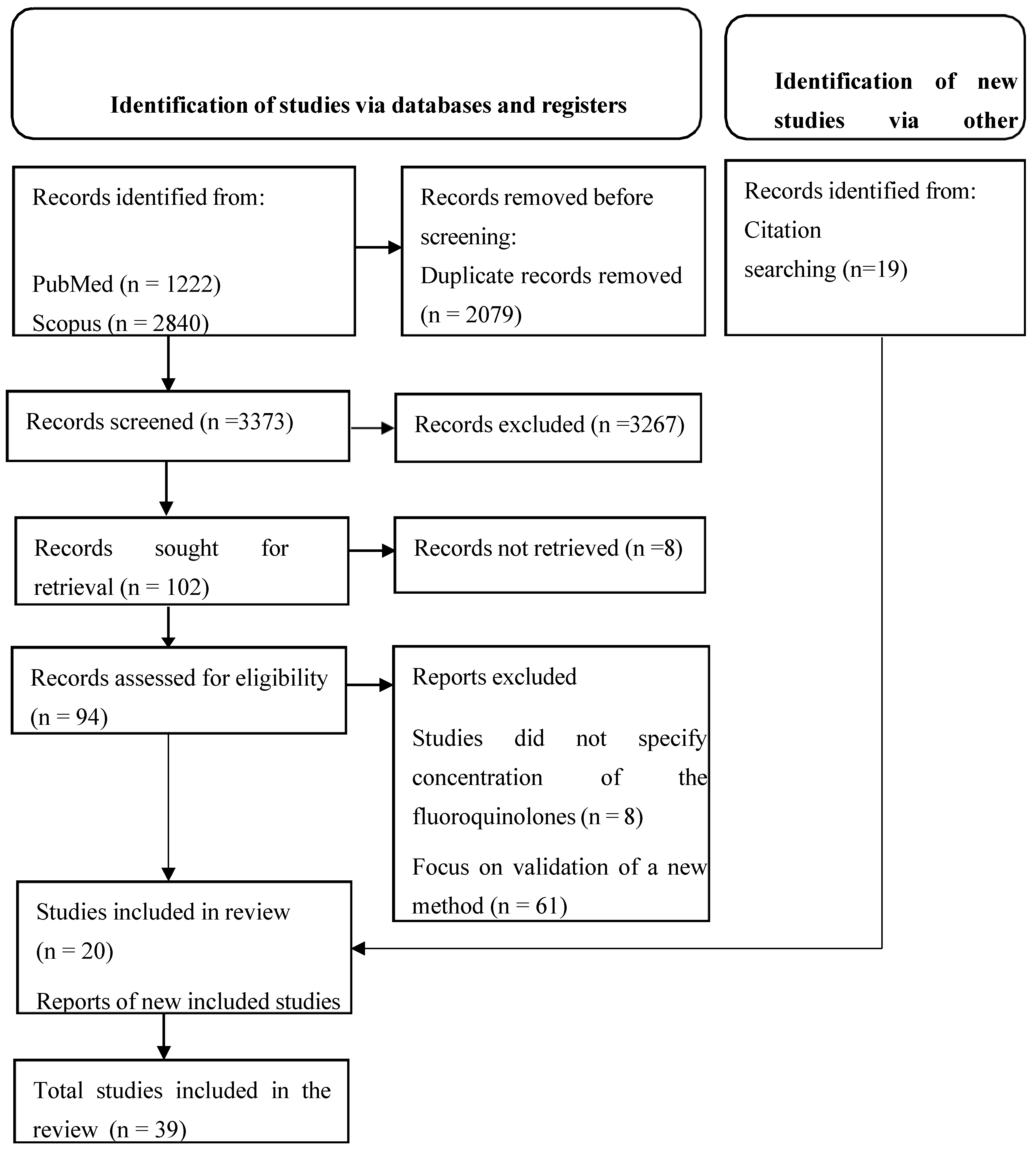

A total of 5452 articles were retrieved from the databases. After removing duplicate articles, 3373 unique articles remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 102 remained for full paper screening and this resulted in the elimination of 82 articles as outlined in the PRISMA flow chart (

Figure 1). A manual search of the retrieved citations resulted in 19 additional eligible articles. Overall, 39 articles were considered relevant and included in the systematic review.

4.2. Characteristics of Data Reported in the Included Articles.

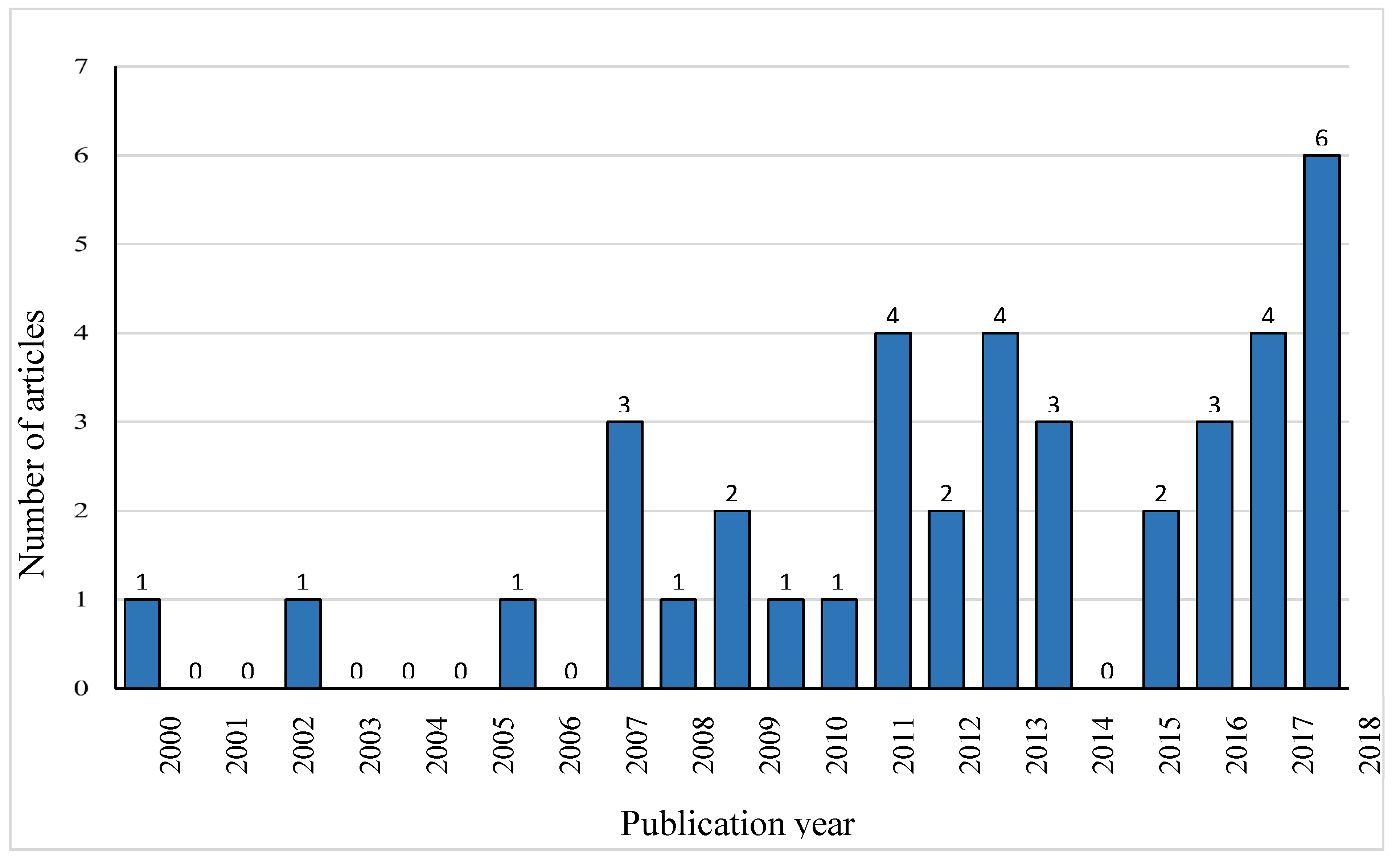

The number of publications on the concentration of fluoroquinolones in food animals increased over the years, with 17.9% (7/39) of the reports published in the decade from 2000- 2010 and 66.7% (26/39) in the decade from 2011- 2021.

Figure 2 highlights the trend in publication of the articles that investigated the concentration of fluoroquinolones in livestock and poultry samples.

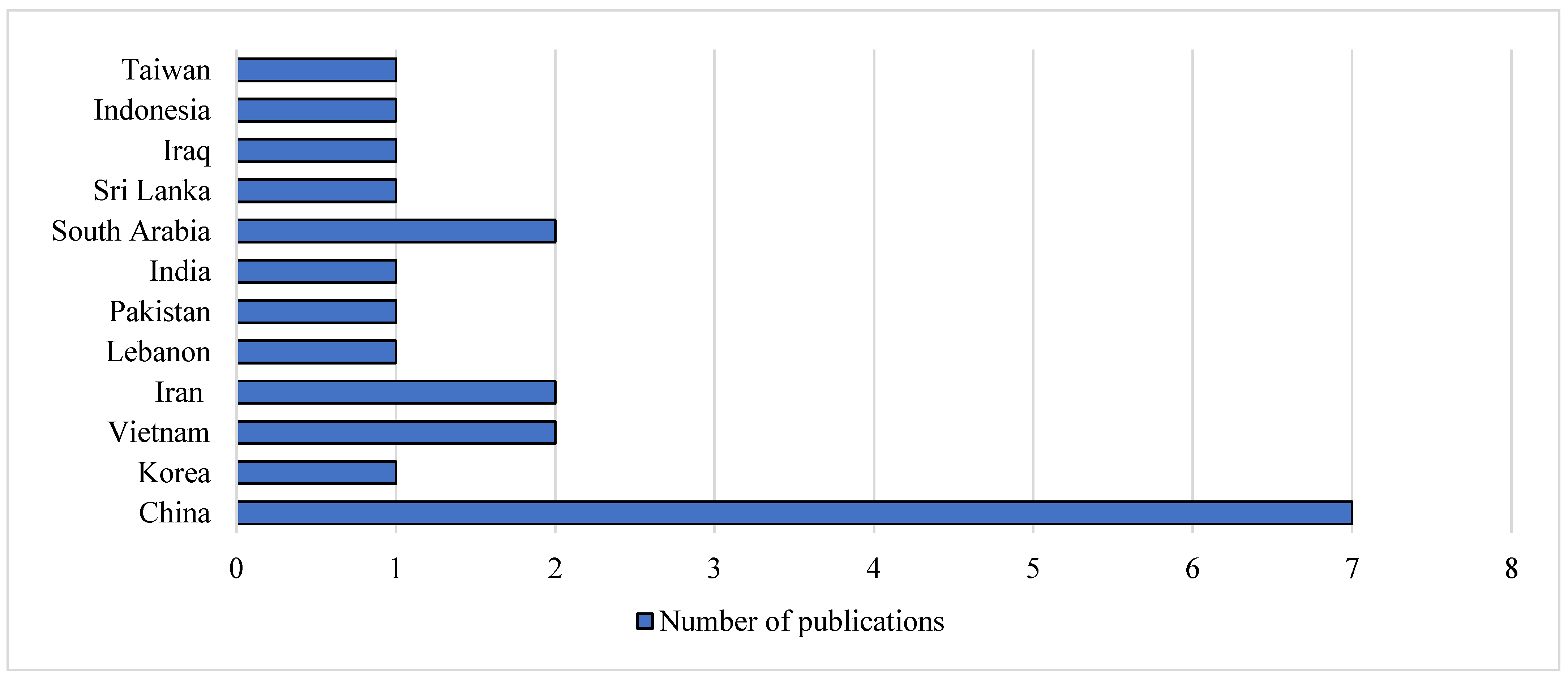

The studies reported data for four continents including Africa, Asia, Europe, and South America. Most of the selected articles were reported from Asia (53.8%, 21/39), followed by Africa (25.6%, 10/39). In South America, there was only one relevant study from Brazil (Panzenhagen et al., 2016), while in Europe there was a slightly higher number of records at 17.9% (7/39). In North America and Australia, there were no relevant data on the concentration of fluoroquinolones in food animals.

In the data from Africa, as can be seen in

Figure 3, Nigeria and Africa each account 40% (4/10) of the studies. Southern Africa was only represented by South Africa with regard to investigations into fluoroquinolone concentration in food animals. On the Asian continent, 33.3% (7/21) of the publications were from China (

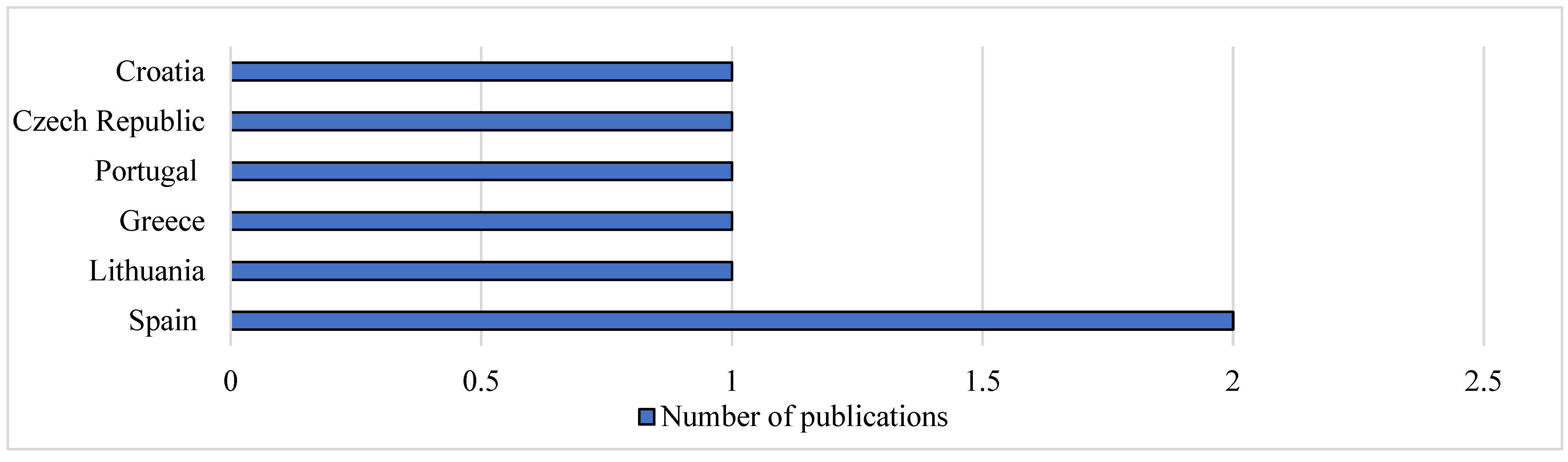

Figure 4). In Europe, most of the studies related to concentration of fluoroquinolones in animal products were carried out in Spain as shown in

Figure 5.

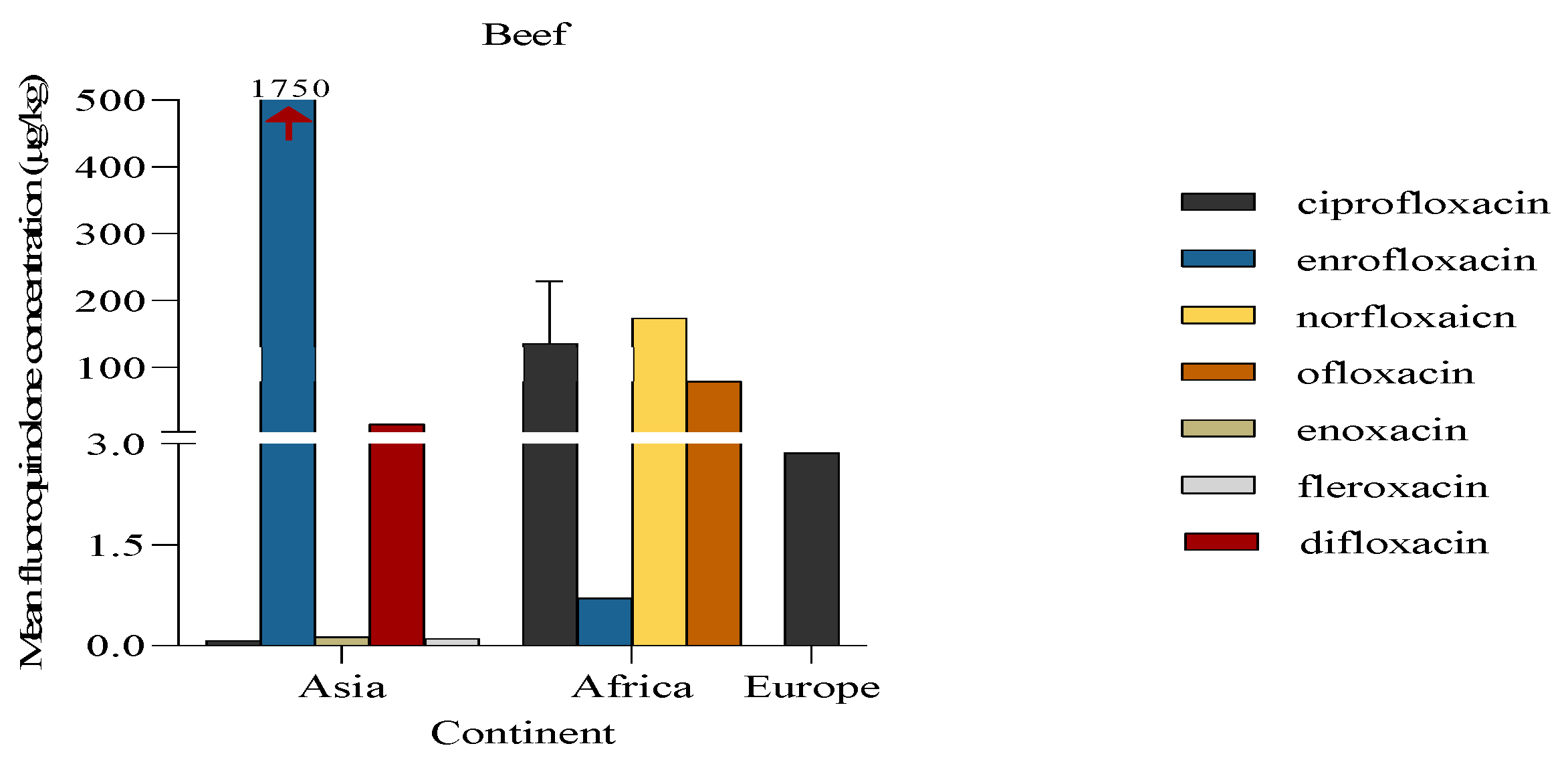

4.3. Concentration of Fluoroquinolones in Livestock

The concentration of fluoroquinolones in beef was reported from publications done in Africa, Asia and Europe. Researchers collecting data for Asia reported the highest number of different fluoroquinolones (n = 5) present in beef. Of these, the fluoroquinolone with the highest mean concentration above its MRL was enrofloxacin (1750 μg/kg) and this was reported from a study conducted in Iraq (Sultan, I. A. 2014). In contrast, a single study conducted in Greece (Stavroulaki et al., 2022) detected one fluoroquinolone, ciprofloxacin at low concentration of 2.87 ug/kg (

Figure 6).

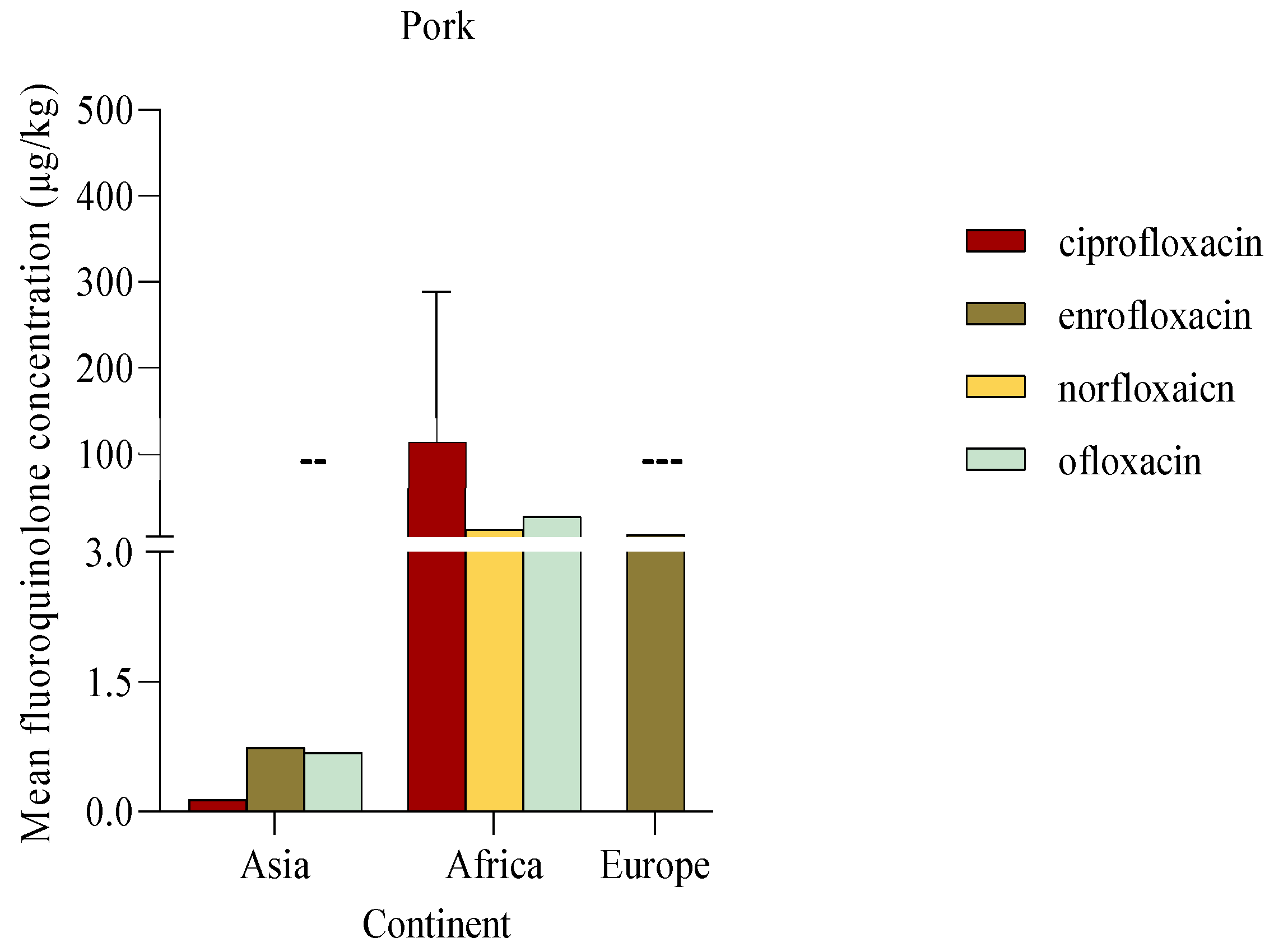

Pork

In pork, the fluoroquinolone with the highest mean concentration detected was ciprofloxacin (184 ± 126.5 μg/kg) followed by ofloxacin (27.02 μg/kg). Single studies published from Asia reported low concentrations of fluoroquinolones including ciprofloxacin, enrofloxacin, and ofloxacin ranging from 0.1 to 0.7 μg/kg. Similarly, a publication from Greece detected low mean concentrations of enrofloxacin (4.97 μg/kg). Notably, African publications reported high fluoroquinolone concentrations relative to other studies as shown in

Figure 7.

Milk

The concentration of fluoroquinolones in milk were reported from Asian and European publications namely Korea, China, Spain, Czech Republic and Croatia. Enrofloxacin, difloxacin, marbofloxacin and danofloxacin were among the fluoroquinolones detected in European publications with high mean concentrations ranging from 192.5 ± 366.6 μg/L to 705.9 ± 993.5 μg/L. In contrast, the fluoroquinolones detected from Asian publications had lower concentrations below their MRL as shown in

Figure 8.

4.4. Concentration of Fluoroquinolones in Poultry

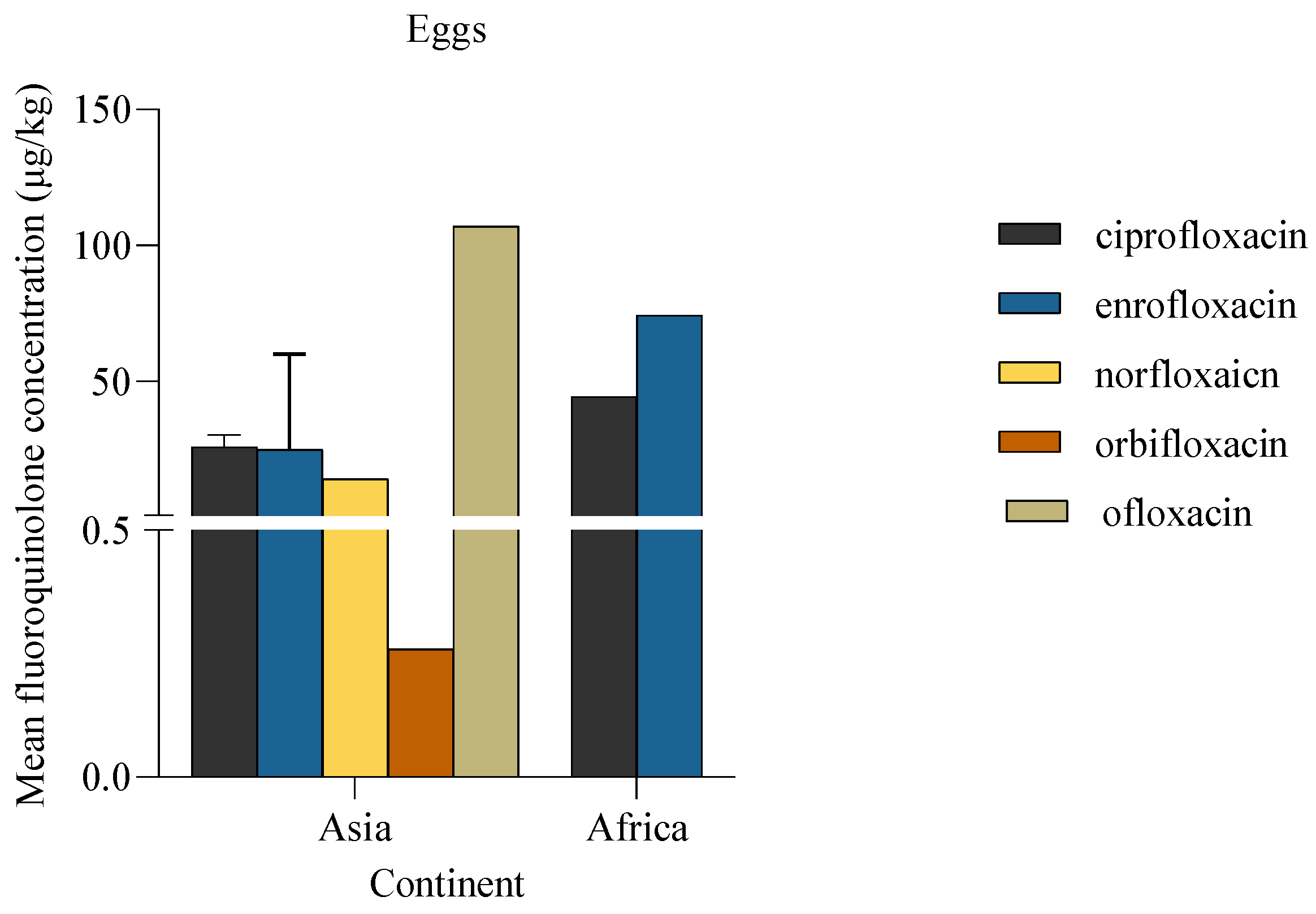

Eggs

The concentration of fluoroquinolones detected in eggs ranged from 0.3 μg/kg to 107.1 μg/kg. Among the various fluoroquinolones detected, enrofloxacin was the most frequently detected, being recorded in 75% (3/4) of the articles.

Figure 10.

Mean concentration of fluoroquinolones in eggs. The bar represents the descriptive statistic (mean) with standard deviation for ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin. ln the studies without error bars, the data are derived from a single study and therefore no error bars are shown.

Figure 10.

Mean concentration of fluoroquinolones in eggs. The bar represents the descriptive statistic (mean) with standard deviation for ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin. ln the studies without error bars, the data are derived from a single study and therefore no error bars are shown.

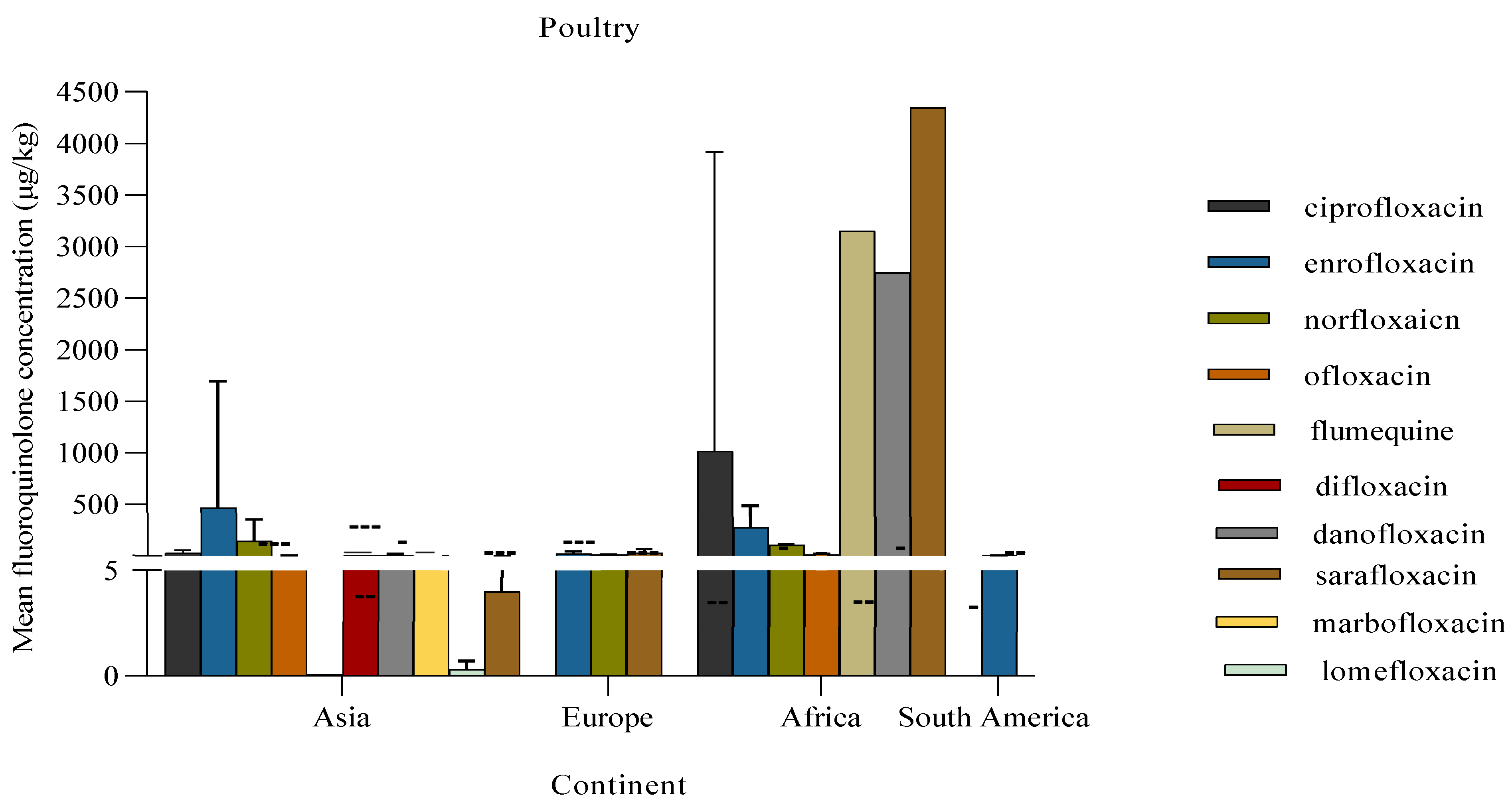

Poultry meat

The concentration of fluoroquinolones detected in poultry meat varied significantly, as evidenced by the data in

Figure 9. The fluoroquinolone with the highest mean concentration in poultry meat was sarafloxacin (4349.1 μg/kg), while flumequine had the lowest mean concentration (0.1 μg/kg). From the studies conducted in Africa, 71.4% (5/7) of the detected fluoroquinolones had mean concentrations above their MRLs as per EU regulations (VMD, 2021). According to the one study conducted in South America and three from Europe, the mean concentrations of the detected fluoroquinolones were below the MRL (≤35 μg/kg). In contrast, studies done in Asia recorded a high residue mean concentration of enrofloxacin (468.8 ± 1227 μg/kg) above the MRL of 100 μg/kg (VMD, 2021)

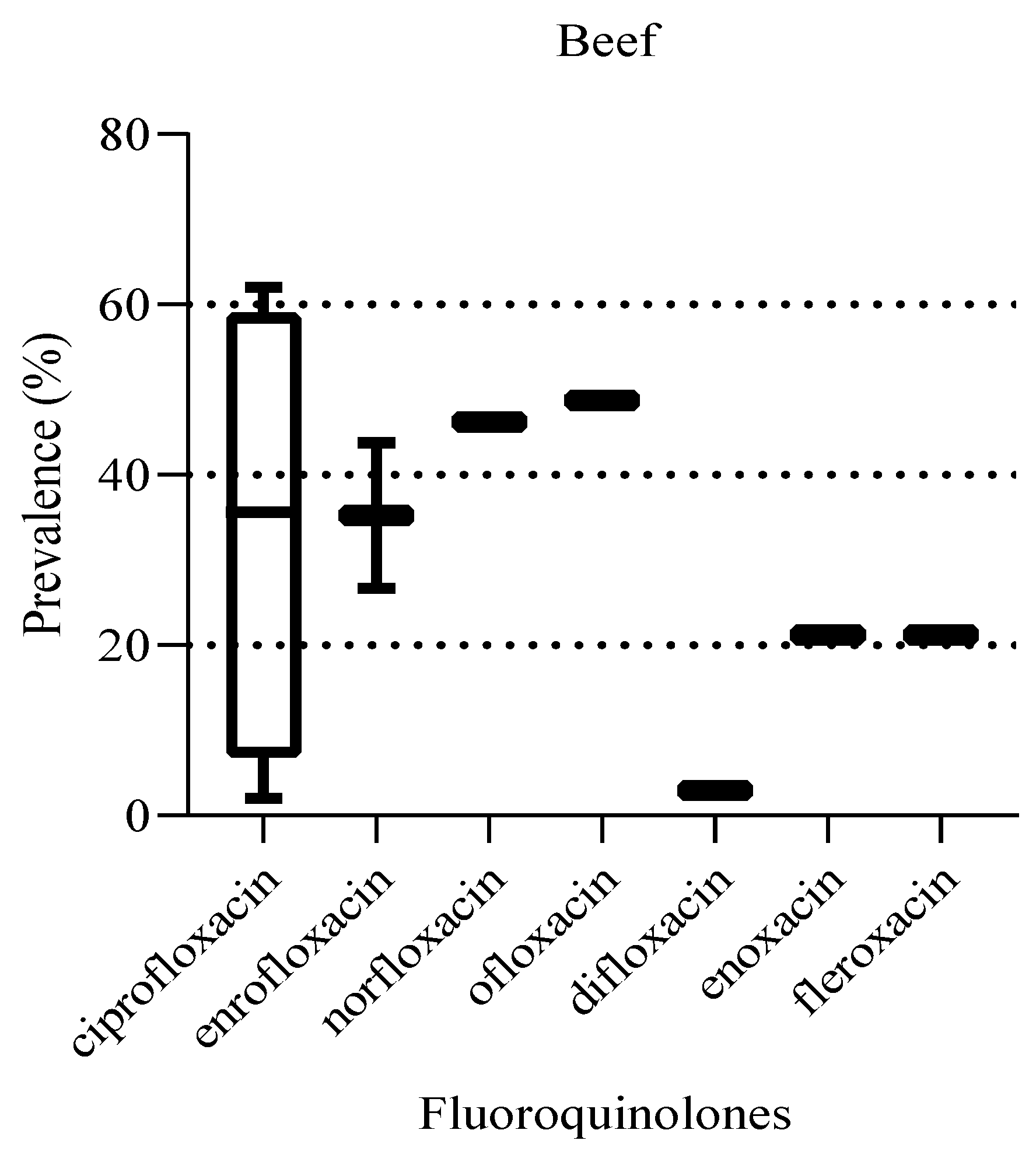

4.5. Prevalence of Fluoroquinolones in Livestock Samples

The prevalence of the fluoroquinolones in beef ranged from 2 to 63.6%, with 71.4% (5/7) of the data reported from single studies (

Figure 11). The most prevalent fluoroquinolone was ciprofloxacin. Despite the wide range of prevalence levels for the different fluoroquinolone detected, there was no statistically significant difference in prevalence between them (P = 0.87).

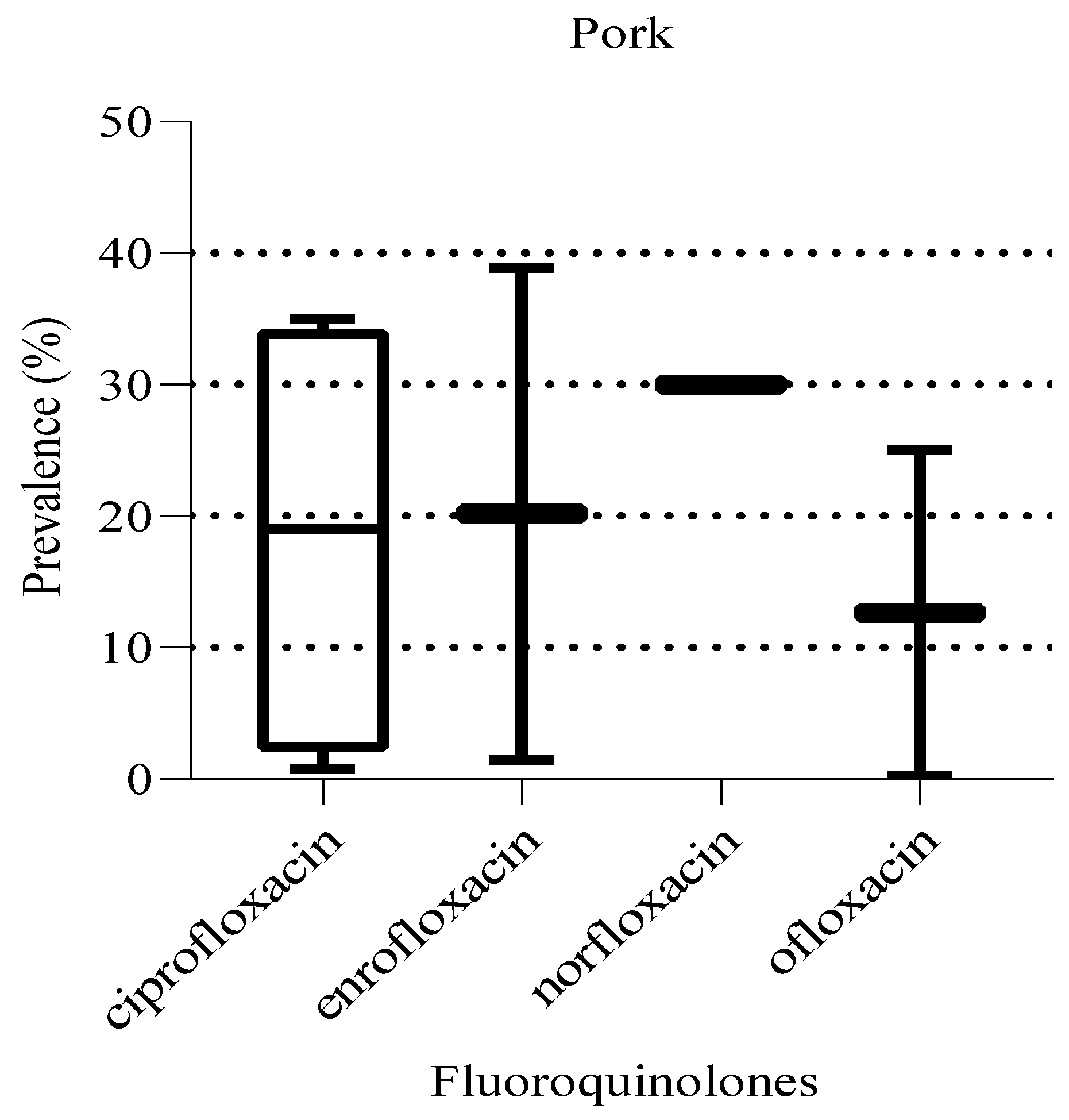

Similarly, in pork, the prevalence of the fluoroquinolones detected ranged from 0.3 to 38.9% (

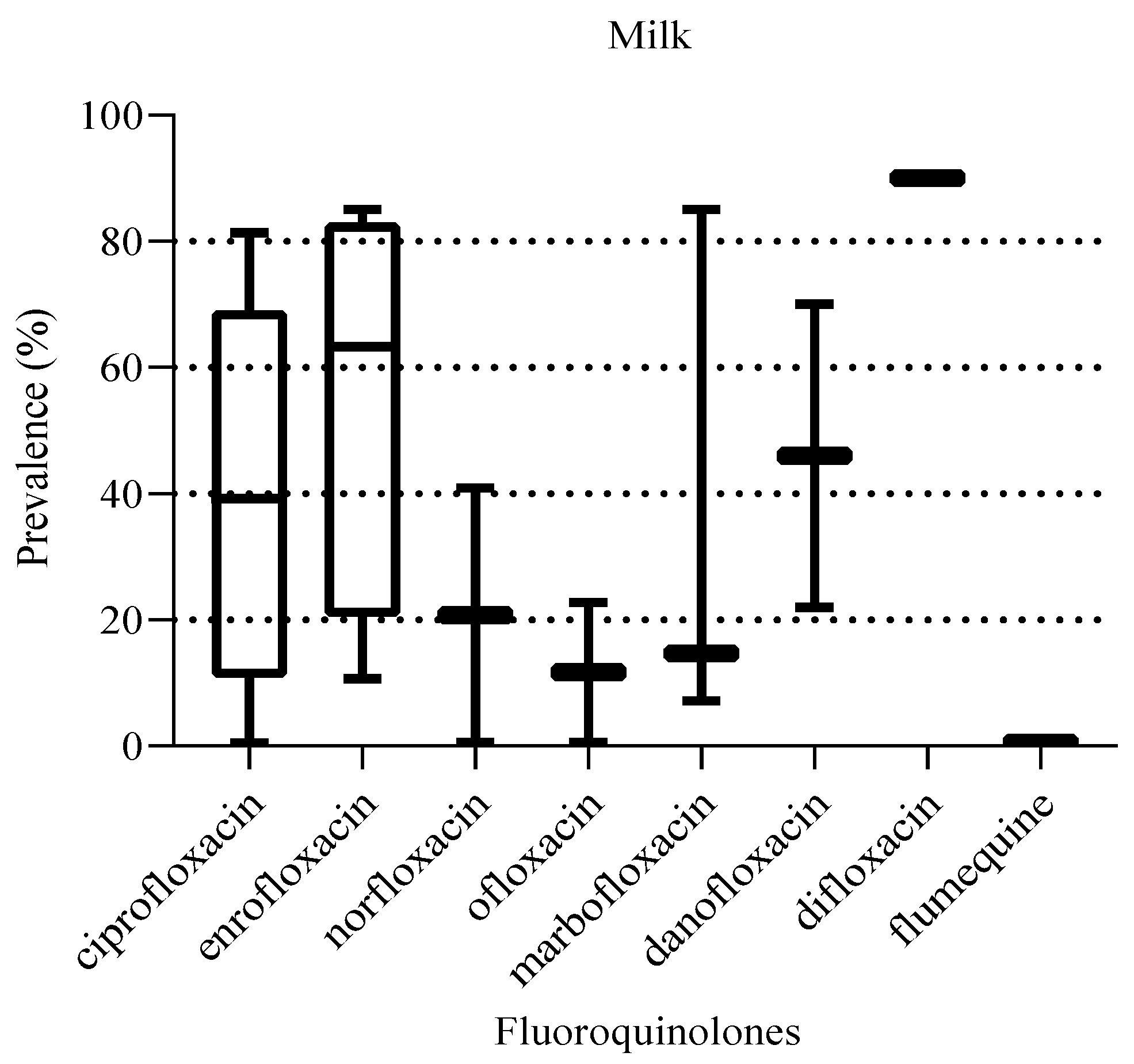

Figure 12), with no statistically significant difference in prevalence levels between the fluoroquinolones (P = 0.80). The fluoroquinolone with the highest prevalence in pork was enrofloxacin. In milk, the variability in prevalence of the detected fluoroquinolones was higher (ranging from 0.42 to 90%) as shown in

Figure 13. However, similar to beef and pork, there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence levels of different fluoroquinolones detected in milk (P = 0.41).

Figure 9.

Mean concentration of fluoroquinolones in poultry. The bar represents the descriptive statistic (mean) with standard deviation. Error bars are not shown for single studies in danofloxacin, sarafloxacin, flumequine, and lomefloxacin. Dotted lines represent MRL per fluoroquinolone.

Figure 9.

Mean concentration of fluoroquinolones in poultry. The bar represents the descriptive statistic (mean) with standard deviation. Error bars are not shown for single studies in danofloxacin, sarafloxacin, flumequine, and lomefloxacin. Dotted lines represent MRL per fluoroquinolone.

Figure 11.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones detected in beef. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum data values.

Figure 11.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones detected in beef. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum data values.

Figure 12.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in pork. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

Figure 12.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in pork. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

Figure 13.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones milk. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

Figure 13.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones milk. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

4.6. Prevalence of Fluoroquinolones in Poultry

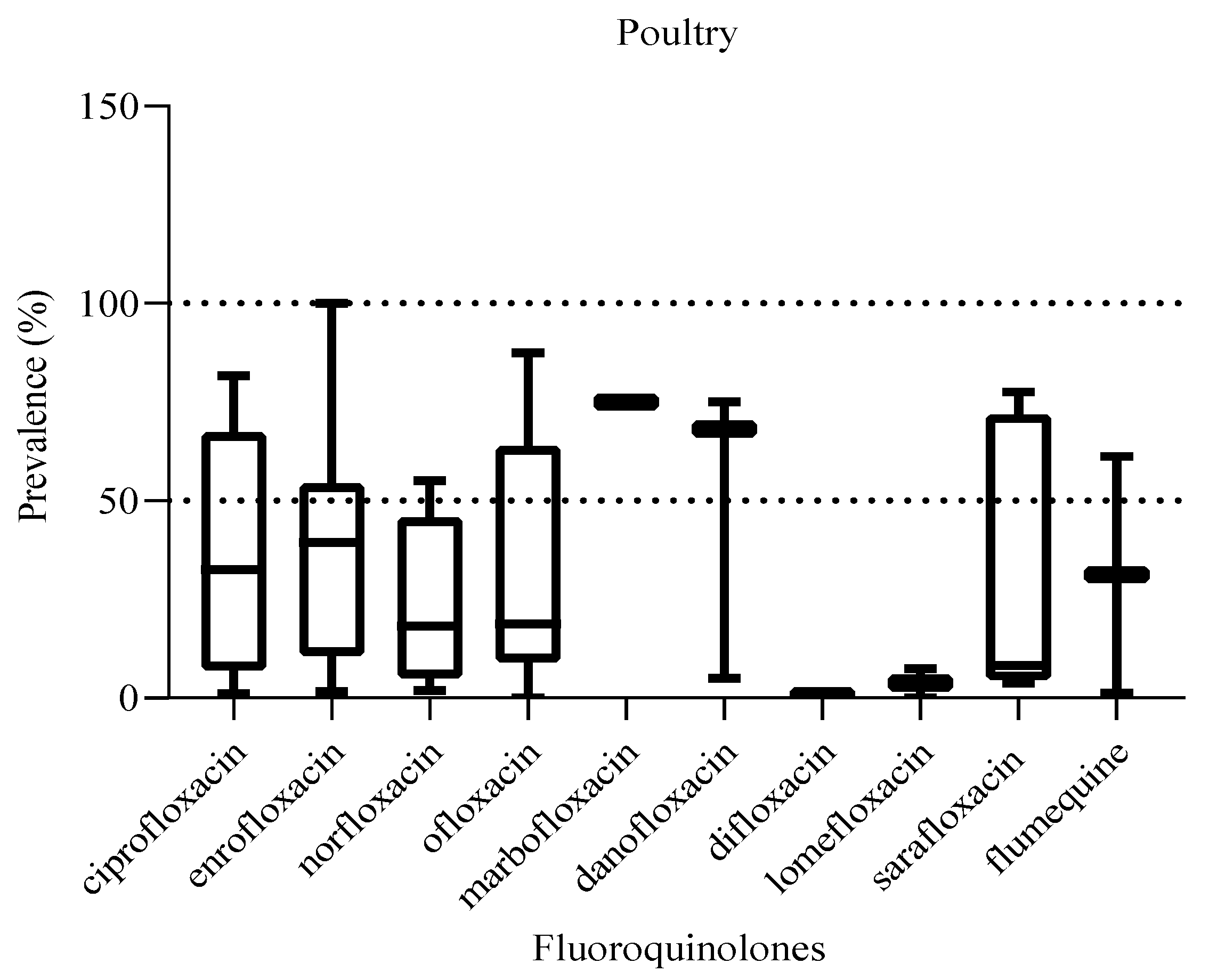

The prevalence of the different fluoroquinolones detected in poultry meat ranged from 0.1 to 100% (

Figure 14) with no statistically significant difference in prevalence between them (P = 0.73). The fluoroquinolones with the lowest and highest prevalence were difloxacin and enrofloxacin, respectively.

Figure 15.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in poultry. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

Figure 15.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in poultry. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

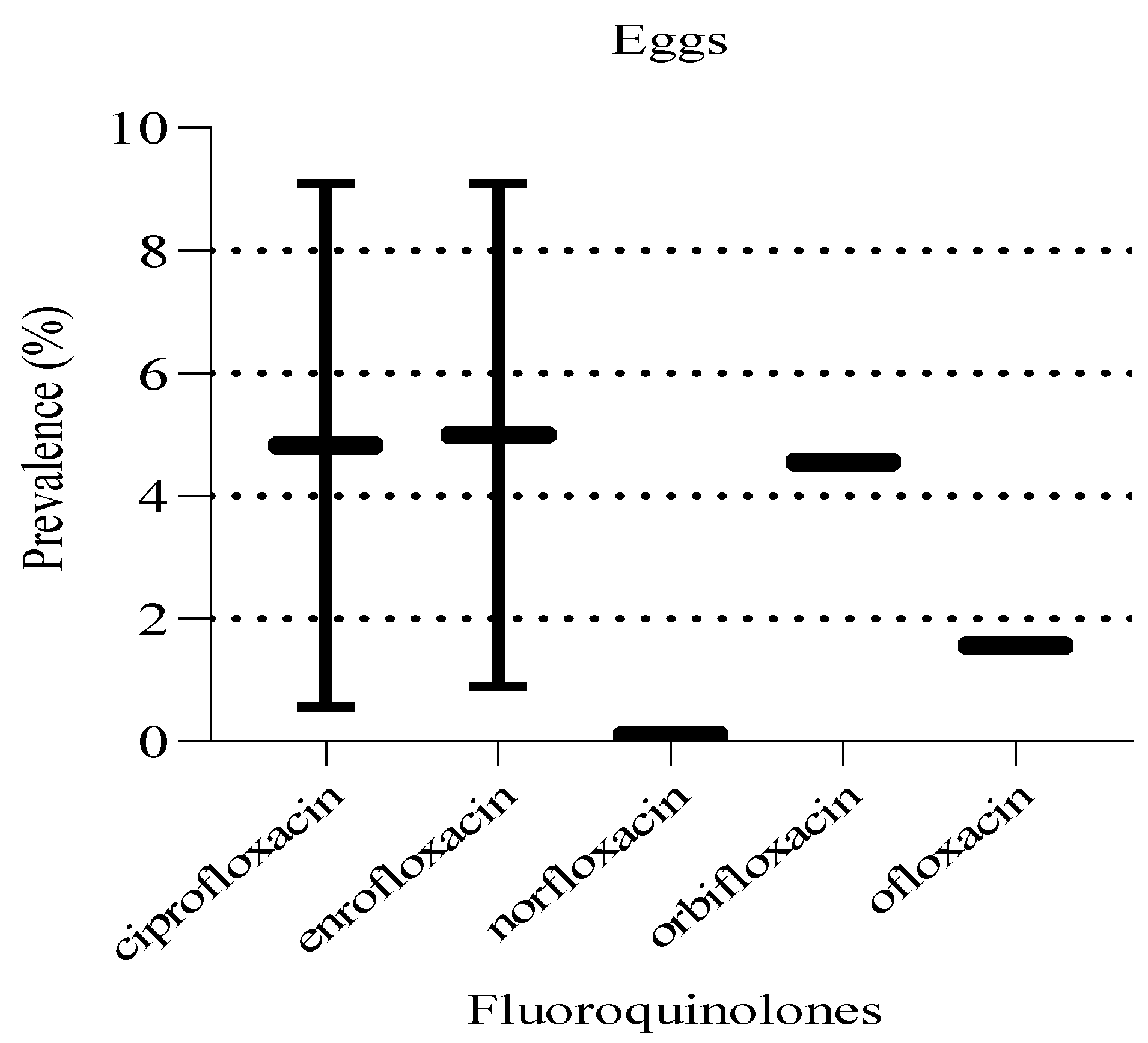

In egg samples, the prevalence of detected fluoroquinolones ranged between 0.1 to 9.1% (

Figure 15). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.87) in prevalence levels between the fluoroquinolones detected in eggs. Notably, a significant proportion (60%, 3/5) of the detected fluoroquinolones in eggs samples were based on findings from single studies.

Figure 14.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in eggs. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

Figure 14.

Prevalence of fluoroquinolones in eggs. The box ranges from the 25th to 75th percentiles, and the ends of whiskers represent minimum and maximum prevalence levels.

5. Discussion

The presence of fluoroquinolones in food-animals is receiving attention globally due to the potential impact on animal and human health. In this systematic review, scientific evidence on concentration of fluoroquinolones in food-animals published between 2000 and 2022 provides valuable insights into the extent of this issue. The review indicated that there has been a significant increase in research activity on this topic. This reflects a growing recognition of the potential adverse effects of fluoroquinolone use in food animals, including antimicrobial resistance and the potential transmission of resistant genes from animals to humans.

Although the number of publications on the topic seem to have increased over time there is still a significant knowledge gap worldwide. This is particularly concerning especially in developing countries. The main barriers to reporting quantitative data on antimicrobial agents intended for use in food animals in these countries include poor coordination between national authorities and private sectors, lack of regulatory framework, inadequate human resources and funds (WOAH, 2024).

On the contrary some Asian, European and Australian countries have legal guidelines regarding antibiotic residues in food that are relatively strict and checked by state authorities. Therefore, scientific studies by non-governmental research groups do not seem worthwhile (Treiber and Beranek-Knauer, 2021). Australia banned the usage of fluoroquinolones in food animals in 2006 (Collignon et al., 2019). The number of European studies are almost evenly distributed across different countries. This could be caused by the effects of the strict directives in European Union policy on antibiotic residues in foods of animal origin (Treiber and Beranek-Knauer, 2021). In Europe almost every antibiotic used in veterinary medicine is licensed or prescribed by a qualified veterinarian (WHO, 1998). Furthermore, the introduction of MRL ensures limits are put in place to guarantee the safety of animal products intended for human consumption (Hernández-Arteseros et al., 2002). This strict regulation explains the relatively low residue concentrations (≤ 35 μg/kg) of various fluoroquinolones found in beef, pork, and poultry recorded from the European publications.

Maximum residue values are established to protect consumers from potential harmful effects of drug residues in food products. However, these limits do not provide an absolute guarantee that animal products exceeding these thresholds will not enter the market (Muaz et al., 2018). This is particularly relevant in the context of fluoroquinolone antibiotics which were reported from some European publications. The established MRLs for fluoroquinolones in milk are 30 μg/L for danofloxacin, 75 μg/L for marbofloxacin, and 100 μg/L for enrofloxacin (VMD, 2021). Despite these regulatory thresholds, in Europe, reports indicated higher mean residue concentrations of these fluoroquinolones with levels reaching 705.93 ± 993.5 μg/L for danofloxacin, 225.5 ± 379.0 μg/L for marbofloxacin, and 192.5 ± 366.6 μg/L for enrofloxacin. These findings highlight a critical gap between regulatory standards and real-world contamination levels, raising questions about the effectiveness of monitoring systems and enforcement mechanisms designed to ensure compliance with MRLs.

Elevated fluoroquinolone concentrations pose a significant risk to human health because the residues of these antibiotics can remain in milk even after heat treatment due to their high stability and can reach the dairy industry and consumers. The implications of these residues extend beyond individual health risks; they also contribute to the broader issue of antibiotic resistance which poses a significant public health threat. Implementing compulsory fluoroquinolone screening tests for milk before it reaches the market could serve as an essential safeguard against the sale of contaminated dairy products (Mahmood et al., 2016). Such measures would help ensure compliance with MRLs and protect public health by reducing exposure to potentially harmful antibiotic residues.

Consistently high concentrations of fluoroquinolones above the MRL were also detected in poultry, pork and beef according to reports from Africa. The presence of these residues above MRLs can be attributed to several factors: 1) impudent use of these antibiotics in livestock and poultry farming; (2) poor patent protection leading to over-the-counter practices; (3) absence of monitoring programs and facilities regarding judicial use of fluoroquinolones in livestock production (Kabir et al., 2004, Lawal et al., 2015), (4) failure of compliance with prescribed withdrawal periods. Particular attention should be paid to fluoroquinolones because they are toxic to humans even in low concentrations (Muaz et al., 2018).

Similarly, the detection of some fluoroquinolones including ofloxacin in eggs at levels above zero raises concerns about unauthorized antibiotic use in poultry farming. Ofloxacin is not approved for use in laying chickens due to concerns about residues transferring to eggs consumed by humans. The presence of ofloxacin residues in eggs could indicate a lack of enforcement of antibiotic regulatory policies (Teglia et al., 2021). To safeguard public health and prevent the occurrence of unauthorized drug residues in eggs, it is essential to strengthen regulatory and enforcement measures related to poultry production.

The high prevalence (<50%) of residues in the poultry meat indicate the widespread use of fluoroquinolones in the poultry industry. This may be influenced by several factors such as the amount of drug use, extent to which the drugs are controlled and level of drug residue monitoring (Kabir et al., 2004). On the other hand, the prevalence fluoroquinolones in eggs samples was less than 10%. This low prevalence is likely due to strict regulations on antimicrobial use in egg laying chickens, including zero tolerance policies. These control measures seem to be effective in limiting the presence of fluoroquinolones in eggs. Overall, the most prevalent fluoroquinolone in the livestock samples was enrofloxacin. This could be attributed to its wide spread use and prescription as a broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone in veterinary medicine (Katzung, 2001).

5.1. Limitations

When critically evaluating literature on the concentration of fluoroquinolones in food animals, some challenges were encountered. One major issue was the limited number of countries reporting data on fluoroquinolone concentrations, with reports predominantly coming from Asian countries. This lack of geographical representation can skew the overall findings and limit the generalizability of the results. The variability in methodologies, outcomes and study designs in the included studies were also a great concern because it was challenging to combine results effectively and draw meaningful conclusions. The heterogeneity of the studies prevented a meta-analysis from being conducted. This limitation has the potential to impact the comprehensiveness of the review and may lead to an incomplete understanding of fluoroquinolone concentrations in food animals, worldwide. Lastly, insufficient data, such as the reporting of concentration ranges without means or median concentrations, made it difficult to draw accurate conclusions as some articles were excluded from the analysis. Given these limitations and their potential impact on the validity and reliability of the results, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings of this study.

5.2. Conclusion

This review allowed us to summarize the scientific evidence on fluoroquinolones and to our knowledge this is the first systematic review on detection of concentration of fluoroquinolones in food of animal-origin, worldwide.

Given the growing importance of fluoroquinolones in animal production and their widespread misuse in various countries; these drugs must be cautiously administered in appropriate concentrations under proper clinical assessment taking into consideration the withdrawal periods (Trouchon and Lefebvre, 2016). Improving the judicial and rational use of fluoroquinolones in food-animals is paramount to safeguard human and animal health. It is only through collaborative efforts and interdisciplinary cooperation that we will be successful in addressing promoting responsible antimicrobial use practices (WOAH, 2024).

There is a need to intensify research pertaining to the concentration of fluoroquinolone residues in animal-derived food to get the estimates of residues in different food matrices. As the WOAH in collaboration with WHO aims to strengthen communication with other national agencies, beyond Veterinary Services which are involved in antimicrobial use data collection in the animal health sector, educational work regarding antimicrobial residues in animal products must also be stepped up particularly in developing countries (WOAH, 2024). This can be done through increased monitoring of the use of antibiotics in animal breeding. Users must be informed about the health consequences for their customers regarding antibiotic residues in animal products and the development of multi-resistant germs. Furthermore, alternatives to fluoroquinolones, such as vaccinations, use of prebiotics, probiotics, and traditional medicinal herbs in animal feed must also be further researched to ultimately reduce the use of these antibiotics in animal breeding (Gouvêa et al., 2015).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akram, F.; Imtiaz, M.; Haq, I.U. Emergent crisis of antibiotic resistance: A silent pandemic threat to 21st century. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 174, 105923. [CrossRef]

- BAAZIZE-AMMI, D., DECHICHA, A. S., TASSIST, A., GHARBI, I., HEZIL, N., KEBBAL, S., MORSLI, W., BELDJOUDI, S., M.R. SAADAOUI, M. R. & GUETARNI, D. 2019 Screening and quantification of CAC 2011. Codex Alimentarius Commission. Codex standard. Rome, Food Agriculture Organization.

- COLLIGNON, P. J. & MCEWEN, S. A. 2019. One Health-Its Importance in Helping to Better Control Antimicrobial.

- GAJDA, A., POSYNIAK, A., ZMUDZKI, J., GBYLIK, M. & BLADEK, T. 2012. Determination of (fluoro)quinolones in eggs by liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection and confirmation by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chemistry 135, 430-439. [CrossRef]

- GOUVÊA, R., DOS SANTOS, F. & DE AQUINO, M. 2015. Fluoroquinolones in industrial poultry production, bacterial resistance and food residues: a review. Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science, 17, 1-10.

- HERNÁNDEZ-ARTESEROS, J. A., BARBOSA, J., COMPAÑÓ, R. & PRAT, M. D. 2002. Analysis of quinolone residues in edible animal products. J Chromatogr A, 945, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- HERRERA-HERRERAA, A. V., HERNÁNDEZ-BORGESA, J., RODRÍGUEZ-DELGADOA, M. A., HERREROB, M. & CIFUENTESB, M. 2011. Determination of quinolone residues in infant and young children powdered milk combining solid-phase extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry Journal of Chromatography A, 1218, 7608– 7614.

- JAYALAKSHMI, K., PARAMASIVAM, M., SASIKALA, M., TAMILAM, T. & SUMITHRA, A. 2017. Review on antibiotic residues in animal products and its impact on environments and human health. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 5, 1446-1451.

- KABIR, J., UMOH, V., AUDU-OKOH, E., UMOH, J. & KWAGA, J. 2004. Veterinary drug use in poultry farms and determination of antimicrobial drug residues in commercial eggs and slaughtered chicken in Kaduna State, Nigeria. Food control, 15, 99-105. [CrossRef]

- KATZUNG, B. G. 2001. Basic and clinical pharmacology, CN, USA, Appleton and Lange, Norwalk.

- LAWAL, J. R., JAJERE, S. M., GEIDAM, Y. A., BELLO, A. M., WAKIL, Y. & MUSTAPHA, M. 2015. Antibiotic residues in edible poultry tissues and products in Nigeria: A potential public health hazard. International Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances, 7, 55-61. [CrossRef]

- LEE, M., LEE, H. & RYU, P. 2001. Public health risks: Chemical and antibiotic residues-review. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 14, 11. [CrossRef]

- MAHMOOD, T٭., ABBAS, M., ILYAS, S., AFZAL, N., & NAWAZ, R. 2016. Quantification of fluoroquinolone (enrofloxacin, norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin) residues in cow milk. International Journal of Chemical and Biochemical Sciences, 10,10-15.

- MARTINS, M. T., BARRETO, F., HOFF, R. B. JANK, L., ARSAND, J. B., FEIJÓ, T. C. & SCHERMANSCHAPOVAL, E. E. 2015. Determination of quinolones and fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and sulfonamides in bovine, swine and poultry liver using LC-MS/MS. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 32, 333-341.

- MUAZ, K., RIAZ, M., AKHTAR, S., PARK, S. & ISMAIL, A. 2018. Antibiotic residues in chicken meat: global prevalence, threats, and decontamination strategies: a review. Journal of food protection, 81, 619-627. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Government of the United Kingdom: London, UK, 2016.

- PAGE, M. J., MCKENZIE, J. E., BOSSUYT, P. M., BOUTRON, I., HOFFMANN, T. C., MULROW, C. D., SHAMSEER, L., TETZLAFF, J. M., AKL, E. A., BRENNAN, S. E., CHOU, R., GLANVILLE, J., GRIMSHAW, J. M., HRÓBJARTSSON, A., LALU, M. M., LI, T., LODER, E. W., MAYO-WILSON, E., MCDONALD, S., MCGUINNESS, L. A., STEWART, L. A., THOMAS, J., TRICCO, A. C., WELCH, V. A., WHITING, P. & MOHER, D. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71.

- PANZENHAGEN, P. H. N., AGUIAR, W. S., GOUVÊA, R., DE OLIVEIRA, A. M. G., BARRETO, F., PEREIRA, V. L. A. & AQUINO, M. H. C. 2016. Investigation of enrofloxacin residues in broiler tissues using ELISA and LC-MS/MS. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 33, 639-643. [CrossRef]

- PRAJAPATI, M., RANJIT, E., SHRESTHA, R., SHRESTHA, S. P., ADHIKARI, S. & KHANAL, D. R. 2018. Status of Antibiotic Residues in Poultry Meat of Nepal. Nepalese Veterinary Journal. [CrossRef]

- STAVROULAKI, A., TZATZARAKIS, M. N., KARZI, V., KATSIKANTAMI, I., RENIERI, E., VAKONAKI, E., AVGENAKI, M., ALEGAKIS, A., STAN, M., KAVVALAKIS, M., RIZOS, A. K. & TSATSAKIS, A. 2022. Antibiotics in Raw Meat Samples: Estimation of Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Toxics, 10, 15. [CrossRef]

- SULTANA, A.I. Detection of Enrofloxacin Residue in Livers of Livestock Animals Obtained from a Slaughterhouse in Mosul City. 2014. Journal of Veterinary Science & Technology, 5, 2.

- TEGLIA, C. M., GUIÑEZ, M., CULZONI, M. J. & CERUTTI, S. 2021. Determination of residual enrofloxacin in eggs due to long term administration to laying hens. Analysis of the consumer exposure assessment to egg derivatives. Food Chemistry, 351, 129279. [CrossRef]

- TREIBER, M.F. & KRAUNER-BERANEK, H. 2021. Antimicrobial residues in food from animal origin- A review of the literature focusing on products collected in stores and markets worldwide. Antibiotics, 10 (5), 534.

- TROUCHON, T. & LEFEBVRE, S. 2016. A review of enrofloxacin for veterinary use. Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine, 6, 40-58. [CrossRef]

- VMD 2021. Veterinary Medicines Directorate. Maximum Residue Limits in Great Britain.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION (WHO). 1998. Use of quinolones in food animals and potential impact on human health: report and proceedings of a WHO meeting, Geneva, Switzerland.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION (WHO). 2018. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION (WHO) 2024. WHO's List of Medically Important Antimicrobials: a risk management tool for mitigating antimicrobial resistance due to non-human use. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION FOR ANIMAL HEALTH (WOAH). 2021. OIE List of antimicrobial agents of veterinary importance.

- WORLD ORGANISATION FOR ANIMAL HEALTH (WOAH). 2024. – Annual Report on Antimicrobial Agents Intended for Use in Animals. 8th Report. Paris, 44 pp. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).