1. Introduction to Near-infrared Spectroscopy

Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) has emerged as a highly versatile and effective tool across a wide range of biomedical imaging applications, providing significant insights into the structure and function of biological tissues. This non-invasive technique has proven invaluable in exploring various physiological and pathological processes, as highlighted in [

1,

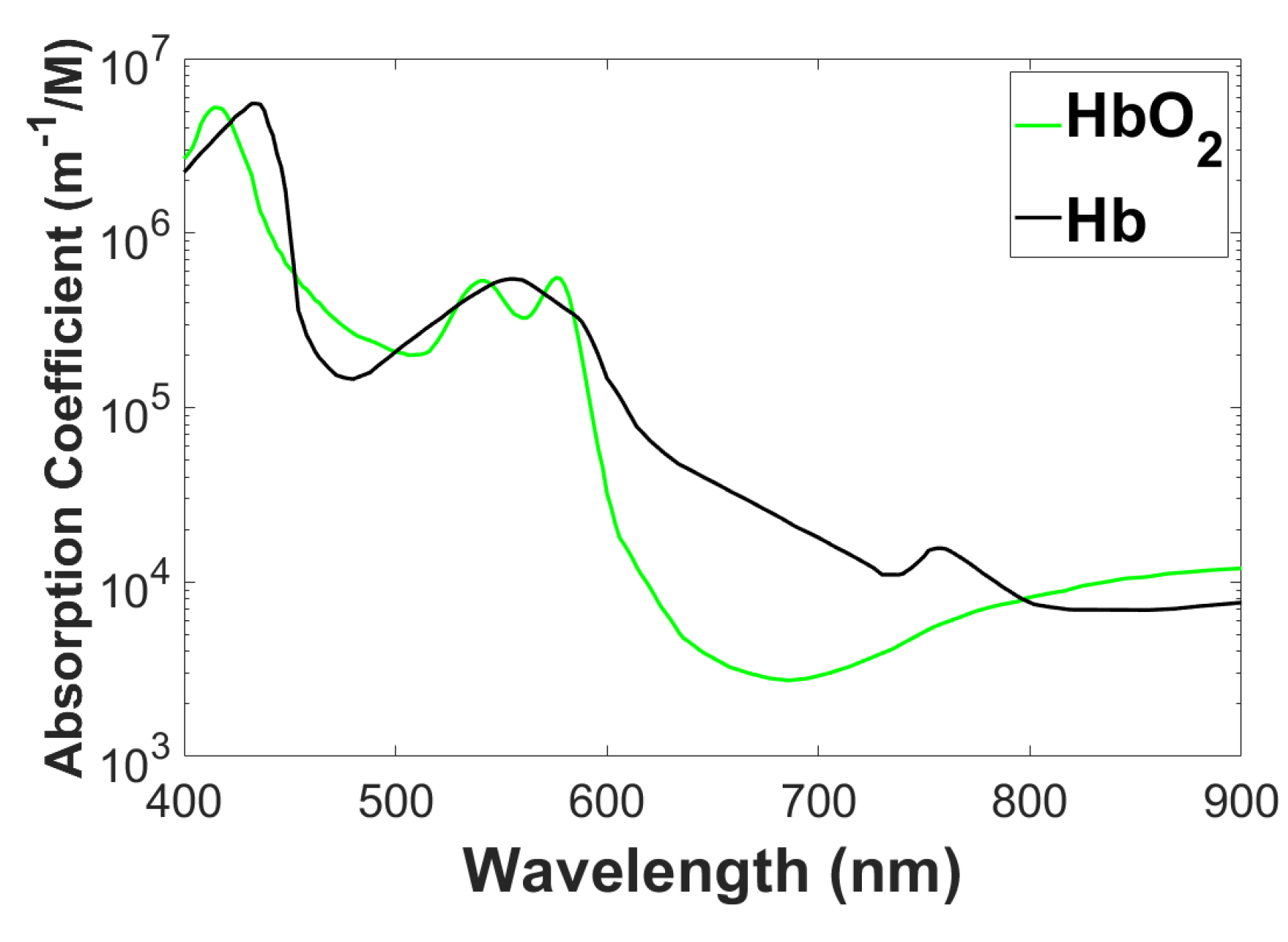

2]. A key area of NIRS application is functional brain imaging, where it enables the monitoring of cerebral oxygenation and hemodynamics without requiring invasive procedures. By detecting variations in the absorption of near-infrared light, NIRS delivers real-time data on brain activity, which is especially advantageous for investigating cognitive functions and the intricate relationship between neuronal activity and blood flow, known as neurovascular coupling. Beyond neuroimaging, NIRS has established its importance in cardiovascular imaging. It plays a crucial role in evaluating tissue oxygenation within the heart and peripheral vascular regions, aiding in the diagnosis of ischemic conditions and the monitoring of interventions during cardiac surgeries. In oncology, NIRS-based diffuse optical tomography has become an essential tool for the early detection and characterization of tumors. By leveraging the unique absorption spectra of different chromophores, as illustrated in

Figure 1, NIRS facilitates the analysis of tissue composition and vascularity. This capability significantly contributes to the accurate localization and differentiation of tumors. Additionally, NIRS shows considerable promise in the domain of musculoskeletal imaging, where it provides valuable information about oxygenation levels in skeletal muscles during physical activities such as exercise or during rehabilitation processes. Thanks to its non-ionizing nature, portability, and suitability for continuous monitoring, NIRS offers unique advantages for point-of-care settings. Its flexibility makes it a highly attractive modality for a variety of medical applications, as discussed in [

3,

4,

5]. This combination of features underscores its potential as a cornerstone in modern biomedical imaging practices.

Over the last hundred years, the field of optical medical imaging has undergone remarkable advancements, playing a crucial role in modern medicine by enabling the acquisition of high-density data with exceptional accuracy. These improvements have not only enhanced the precision of medical imaging but have also minimized the likelihood of errors, offering clinicians more reliable insights. Furthermore, the evolution of optical imaging has introduced a broader spectrum of source-detector configurations and wavelengths, providing significantly greater flexibility and adaptability compared to earlier imaging methods. The concept of "light," as it pertains to these imaging techniques, covers an extensive range of wavelengths that include the infrared, visible, and ultraviolet portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. This understanding of light stems from James Clerk Maxwell’s groundbreaking work in the 19th century, where he described it as a form of electromagnetic wave propagation. Since then, researchers and scientists have utilized this foundational knowledge to explore a wide variety of physical processes and properties within the human body. Optical imaging techniques have been instrumental in measuring and documenting these phenomena, contributing to a deeper understanding of human physiology and advancing medical diagnostics.

Near-infrared spectroscopy diffuse optical tomography (NIRS-DOT) combines the principles of spectroscopy with advanced tomographic techniques to create a powerful imaging tool. One of its most notable strengths lies in its capacity to examine biological tissues non-invasively while providing detailed insights into both depth and structural complexity. By utilizing near-infrared light, NIRS-DOT enables the analysis of internal tissue composition and functional characteristics, delivering a comprehensive understanding of anatomical structures and physiological activities [

6,

7]. This imaging approach has proven particularly valuable in the study and diagnosis of diseases such as breast cancer [

8]. Its ability to detect and differentiate the optical properties of tissues makes it a critical tool for the early detection and characterization of tumors. The integration of multiple light sources and detectors, along with the use of sophisticated image reconstruction algorithms [

9], facilitates the rapid generation of three-dimensional images, allowing for detailed visualization of the tissue under examination.

Recent innovations in the field include the development of circular probes designed for continuous spectroscopic imaging, enhancing the modality’s capability for dynamic assessments. Furthermore, the incorporation of GPUs for image reconstruction has significantly accelerated the process, enabling real-time imaging and improving the overall efficiency of NIRS-DOT. Efforts to further optimize the technology are ongoing, focusing on reducing costs by integrating components such as LEDs and photodetectors, and designing specialized instruments capable of high-speed imaging. These advancements highlight the growing potential of NIRS-DOT as a versatile and impactful tool in the realm of medical diagnostics, offering promising applications across a wide range of clinical settings.

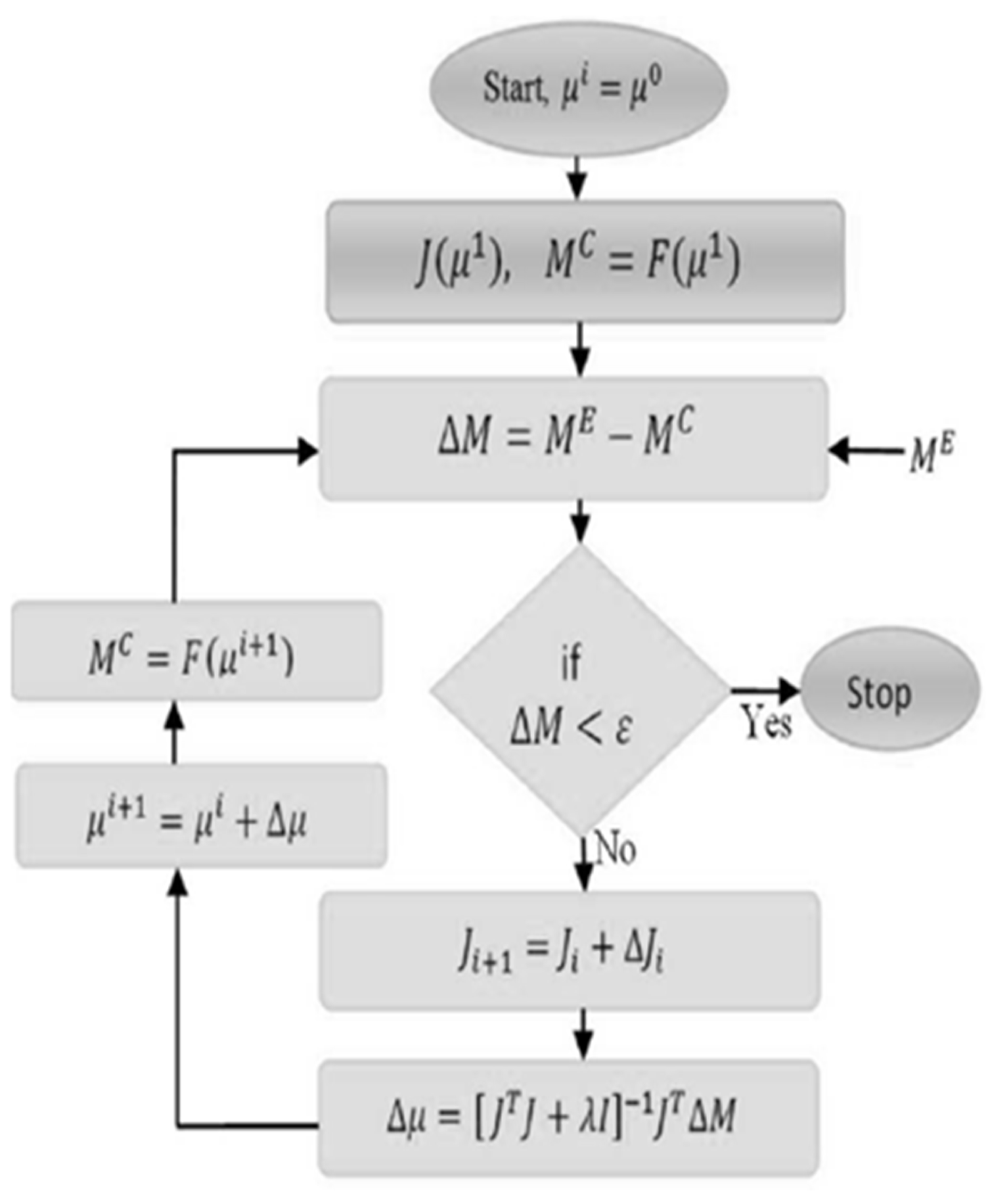

Diffuse Optical Tomography (DOT) has gained significant attention over the past few decades due to its ability to generate functional images of biological tissue using non-ionizing near-infrared (NIR) light. This makes it particularly useful in imaging soft tissues, such as the brain and breast, without exposing patients to harmful radiation. The process of accurately estimating the internal distribution of optical properties within the tissue heavily relies on measurements taken at the boundary of the tissue. These measurements are crucial for understanding how light interacts with the tissue, especially since NIR light primarily interacts with tissue through scattering. As a result, the problem of estimating these internal properties, known as the inverse problem, is complex, nonlinear, ill-posed, and sometimes underdetermined. Solving this problem requires computationally demanding models. In these models, the optical properties of the tissue are iteratively adjusted to match experimental data, typically using a least-squares approach. The algorithm depicted in

Figure 2 illustrates the process involved in DOT image reconstruction. However, due to the computational intensity of these models, obtaining real-time optical images remains a significant challenge, as the models need to be run repeatedly to refine the data and ensure accurate results.

2. Brain Imaging using NIRS

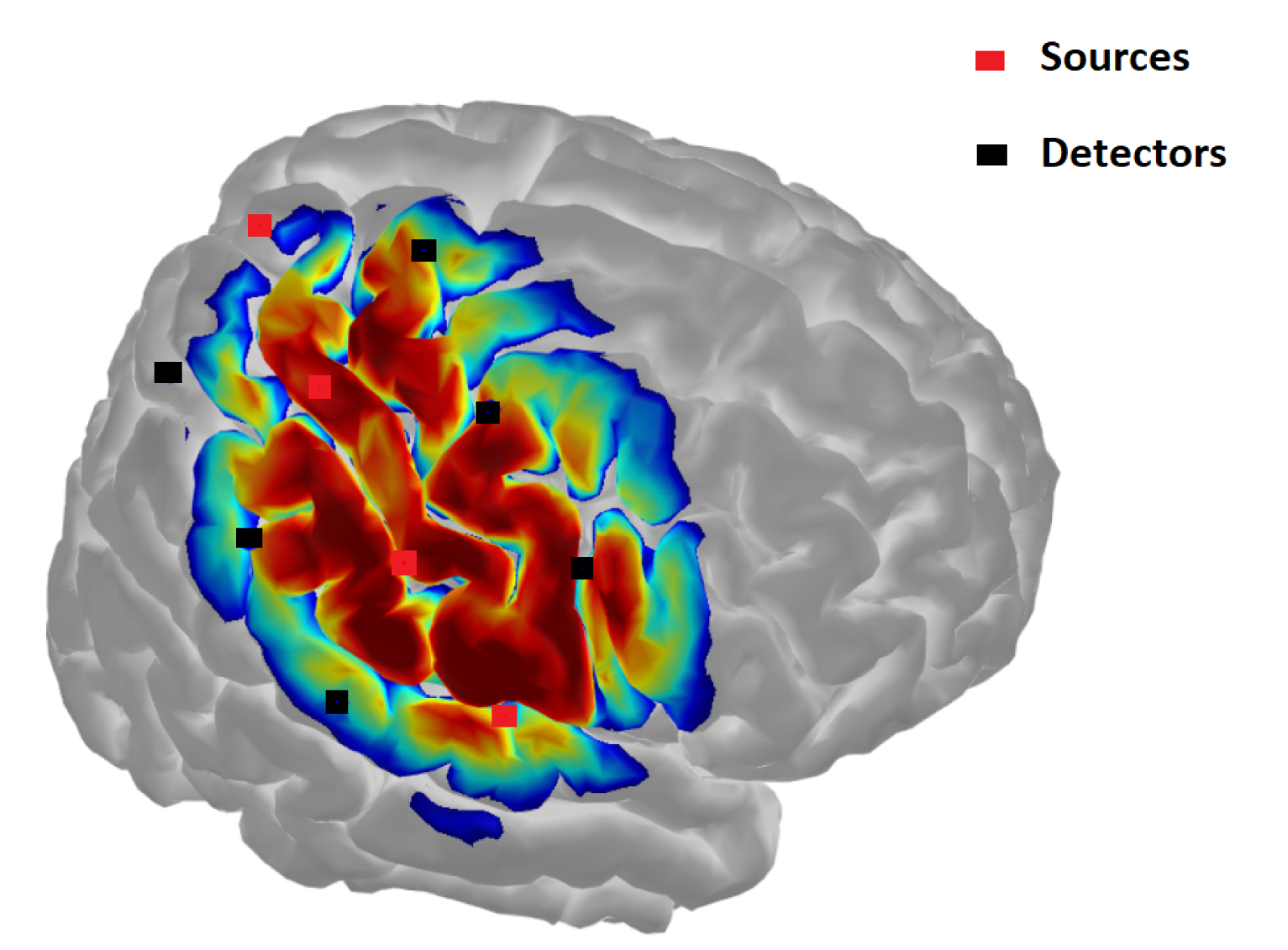

Simple imaging techniques utilizing near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) include functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), a method that focuses on channel-wise measurements rather than complete tomographic image reconstruction [

10]. The natural transparency of biological tissues to near-infrared (NIR) light allows this technique to penetrate the scalp and reach the brain, enabling real-time monitoring of cerebral oxygenation levels and dynamic hemodynamic changes. fNIRS is grounded in the principles of spectroscopy, employing multiple wavelengths of NIR light to measure the concentration of chromophores such as oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin in brain tissues. The process involves directing NIR light sources onto specific regions of the scalp [

Figure 3], while optoelectronic sensors, carefully positioned over the head, detect the light that is either transmitted through or reflected by the tissues. The captured signals undergo rigorous signal processing to derive meaningful physiological information. To quantify changes in hemoglobin concentrations and oxygen saturation levels in cerebral tissues, methods like the Modified Beer-Lambert Law are commonly applied. These calculations are crucial for understanding regional cerebral oxygenation and its variations as shown in

Figure 3. Researchers are continuously working to enhance the spatial resolution, depth sensitivity, and specificity of NIRS measurements, aiming to improve its capability in detecting localized changes in brain activity.

Recent advancements have also seen the integration of NIRS with other neuroimaging modalities such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [

11] and electroencephalography (EEG) [

12,

13,

14]. These multi-modal approaches provide a more comprehensive view of brain function by combining the strengths of each technique.The technical features of NIRS make it a valuable tool in neuroimaging, offering real-time insights into cerebral hemodynamics and oxygenation. Its applications extend across various domains, including neuroscience research, cognitive studies, and clinical settings. For example, NIRS is instrumental in brain-computer interface development and in monitoring cerebral autoregulation in critically ill patients, underscoring its potential for both innovative research and practical medical interventions.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a widely utilized tool for brain imaging, with diverse applications such as measuring mental workload [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], assessing mental stress [

20], and supporting neurofeedback studies [

21]. Compared to diffuse optical tomography (DOT), the design and implementation of an fNIRS system are relatively straightforward [

22,

23,

24,

25]. For instance, researchers have demonstrated the use of compact patches for brain imaging applications [

23,

25]. However, the quality of the signals obtained through fNIRS heavily depends on the design and placement of its light sources and detectors, collectively known as optodes [

26,

27]. This makes the precision in hardware configuration critical for reliable data acquisition. Recognizing the growing need for mobility and accessibility, significant research efforts have focused on developing portable fNIRS systems [

4,

28]. Innovations in this field include the integration of Internet-of-Things (IoT) technology into fNIRS systems, enabling remote monitoring and data collection capabilities [

29,

30,

31]. Another exciting advancement in fNIRS technology is its compatibility with machine learning techniques. By applying machine learning algorithms in real-time, researchers can achieve automatic classification of brain function, opening new doors for more sophisticated and efficient analysis of neural activity [

17,

32,

33,

34]. These developments highlight the versatility and potential of fNIRS as a tool for both research and clinical applications, making it a valuable resource in neuroscience and cognitive science.

2.1. Processing of NIRS Signals

The analysis of fNIRS data requires sophisticated signal processing techniques to extract valuable insights into brain function, given the inherent complexity of the signals [

35]. The initial steps in processing involve addressing various sources of noise that can degrade signal quality, such as motion artifacts and physiological interferences. These noise factors are significant challenges that must be carefully managed to ensure accurate results. To enhance signal quality, spatial filtering techniques like adaptive filtering and principal component analysis (PCA) are commonly utilized. These methods aim to minimize contamination from superficial tissues, such as the scalp and skull, thereby increasing the specificity of the recorded signals to cortical brain regions. This preprocessing step is crucial for isolating meaningful brain activity from extraneous influences.

The raw fNIRS data, which reflect changes in oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) concentrations, are then subjected to statistical analyses to identify task-related activations. General linear models (GLMs) are widely used in this context to model the relationship between the observed fNIRS signals and the experimental conditions. By doing so, researchers can pinpoint brain regions associated with specific cognitive or motor tasks. In addition to traditional statistical methods, machine learning techniques have become increasingly prevalent for analyzing fNIRS data [

36]. Approaches such as support vector machines (SVMs) and neural networks take advantage of the high-dimensional nature of fNIRS datasets, enabling the classification of different cognitive states or task conditions. These algorithms offer a powerful means of interpreting complex patterns within the data, facilitating a deeper understanding of brain function and advancing applications in neuroscience and cognitive research. Human digital twins may also be possible in the future using fNIRS and EEG [

37].

Temporal and spectral analyses are fundamental for understanding the dynamic aspects of brain function through fNIRS data. Temporal analyses primarily involve examining hemodynamic response functions (HRFs), which enable researchers to evaluate the timing, duration, and amplitude of neural activations. These analyses are essential for understanding how the brain responds to specific stimuli or tasks over time. On the other hand, spectral analyses delve into the frequency characteristics of fNIRS signals. Techniques such as wavelet transforms and Fourier analysis are employed to explore the frequency domain, helping to identify oscillatory patterns in brain activity that are linked to various cognitive processes. These frequency-based insights provide a deeper layer of understanding regarding the rhythmic components of brain function. Additionally, connectivity analyses form a vital aspect of fNIRS signal processing by focusing on the functional interactions between different brain regions. Tools such as seed-based correlation analysis and graph theory are commonly used to map and interpret the networks underlying cognitive tasks or resting-state conditions [

38]. These methods reveal how different regions of the brain communicate and coordinate to perform complex cognitive functions.

The field of fNIRS signal processing is continually advancing to tackle challenges like integrating data from multiple channels, effectively removing artifacts, and enabling real-time processing for practical applications, such as brain-computer interfaces. These innovations are crucial as fNIRS gains broader acceptance in both neuroscience and clinical research. As signal processing techniques evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in maximizing the capabilities of this powerful and versatile neuroimaging technology, helping to unravel the complexities of human brain function.

3. Breast Cancer Imaging using NIRS

In 2019, breast cancer claimed the lives of more than 45,000 women in the United States, highlighting its devastating impact and cementing its position as one of the most prevalent cancers affecting women [

39,

40]. Within urban populations, breast cancer stands out as the leading cancer diagnosis among women, accounting for approximately 20% of all documented cancer cases in women’s cancer registries. Although breast cancer is most commonly diagnosed in women aged 50 and older, a significant proportion—around 32% of cases are found in women under the age of 50. While invasive forms of the disease are more frequent in women past the age of 50, there is an observable and concerning increase in cases among younger women. This upward trend underscores the importance of raising awareness, advancing early detection strategies, and focusing on preventive measures to address this growing public health challenge.

Notably, approximately 10% of all new breast cancer diagnoses in the United States occur in women under the age of 45. Several factors contribute to an increased risk of developing breast cancer, including early onset of menstruation (menarche), delayed menopause, having a first full-term pregnancy after the age of 31, a family history of breast cancer diagnosed before menopause, and personal history with either breast cancer or benign proliferative breast conditions. These risk factors highlight the complex and multifactorial nature of breast cancer’s origins, pointing to the wide array of influences that can affect a woman’s likelihood of developing the disease. Given this complexity, there is a pressing need for increased awareness, early screening, and proactive health strategies aimed at women across different age groups to help manage and reduce breast cancer risk [

41].

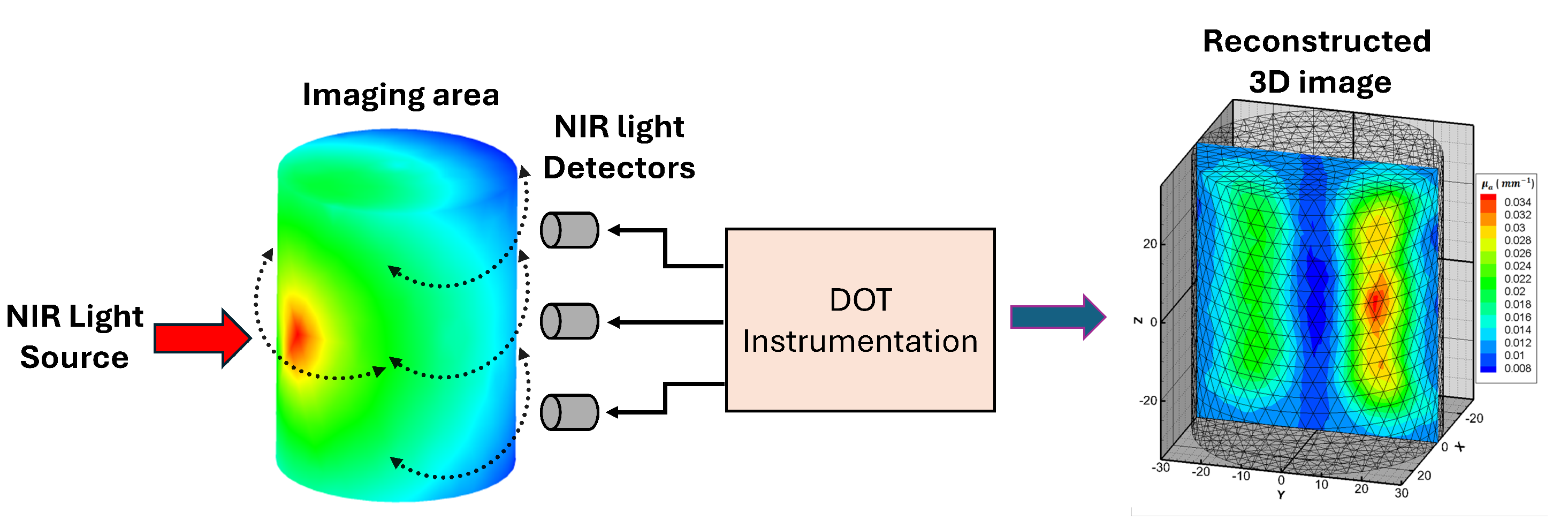

Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) imaging is based on the interaction between near-infrared light and biological tissues, offering crucial insights into the distribution of various optical properties, such as absorption and scattering, as illustrated in

Figure 4 [

42,

43]. Ongoing research in DOT is primarily focused on improving key aspects of the technique, including its spatial resolution, depth penetration, and quantitative accuracy. These improvements are essential for enhancing the reliability and applicability of DOT in clinical settings. To overcome the challenges posed by light scattering in biological tissues, advanced reconstruction algorithms and computational models are being developed. These innovations aim to refine the process of reconstructing three-dimensional images, with a particular emphasis on increasing the fidelity and precision of the resulting data. The ultimate goal is to make DOT a more effective and practical tool for clinical diagnostics and treatment monitoring.

In addition to ongoing advancements in DOT technology, integrating it with other imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), is an important focus of current research. By combining these modalities, a more comprehensive imaging approach can be achieved, taking advantage of the unique strengths of each technique to provide both structural and functional insights. This multimodal approach holds the potential to enhance the overall accuracy and diagnostic capabilities of medical imaging. Furthermore, significant efforts are being made to improve the hardware components that support DOT systems [

44], such as light sources and detectors. By optimizing these components, researchers aim to increase the sensitivity and specificity of DOT, allowing for more precise measurements and better clinical outcomes. Clinical studies are actively being conducted in areas such as breast cancer detection, brain imaging, and functional monitoring of vital organs. These studies are critical in assessing the real-world applicability of DOT and in determining its potential for routine use in medical practice.

Clinical trials are currently underway to evaluate the performance of DOT in diverse healthcare settings, aiming to validate its effectiveness and establish its reliability as a diagnostic tool. Notable contributions to this field include the work of Gibson et al., who have made significant strides in developing advanced reconstruction algorithms for DOT, improving the quality of reconstructed images. Additionally, Zhang et al. have conducted research on integrating DOT with other imaging modalities to enhance breast cancer detection, showcasing the potential for cross-technology collaboration to improve diagnostic accuracy.

3.1. NIRS Medical Image Reconstruction

The process of image reconstruction in diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is a crucial step in transforming the collected data into accurate three-dimensional models that represent the internal optical properties of biological tissues. This step is vital for understanding the structure and function of tissues at a deeper level. However, due to the complex way light interacts and propagates through biological tissues, along with the diffuse nature of the measurements, sophisticated algorithms are necessary to ensure the quality and precision of the reconstructed images.

A primary difficulty in this process is the ill-posed nature of the inverse problem in image reconstruction. Essentially, this means that multiple different distributions of optical properties can produce the same set of measurement data, making it challenging to pinpoint the exact characteristics of the tissues. To address this challenge, various mathematical approaches are employed, with both iterative and analytical methods being commonly used. Iterative reconstruction algorithms, particularly gradient-based optimization techniques, aim to reduce the difference between the measured data and the predicted data through repeated adjustments.

Incorporating regularization methods, such as Tikhonov regularization, helps maintain stability in the reconstruction process, preventing overfitting when noise is present in the measurements. This ensures that the model remains accurate without being overly influenced by small fluctuations in the data. Furthermore, Bayesian approaches are increasingly being utilized, as they allow for the integration of prior knowledge about the expected distributions of optical properties. This additional information helps to improve the reliability and precision of the reconstruction process, enhancing the overall robustness of DOT imaging systems.

The integration of anatomical information into the process of DOT image reconstruction has become a crucial focus in recent research. By combining structural data from other imaging modalities, such as X-ray computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), hybrid imaging approaches significantly improve the spatial accuracy and boundary definition of optical targets in DOT. This fusion of multimodal data enhances the overall precision of the reconstructed images, helping to overcome some of the limitations of DOT, particularly its challenges in capturing detailed structural information.

Moreover, ongoing advancements in regularization techniques have made a substantial impact on improving the spatial resolution of reconstructed DOT images. Nonlinear regularization methods, including total variation regularization, are being increasingly utilized to preserve sharp edges and finer details in the images, thereby enhancing their overall quality. Additionally, the use of sophisticated forward models that incorporate both anatomical and physiological information, along with variations in optical properties across different regions, adds another layer of complexity to the reconstruction process. While this makes the reconstruction more computationally demanding, it results in images that are not only more accurate but also more faithful to the actual anatomical structure of the tissues being examined. This integration of additional data into the reconstruction process promises to further improve the utility and precision of DOT as a diagnostic tool.

Researchers are increasingly focusing on developing novel strategies, such as incorporating machine learning techniques, to improve both the efficiency and precision of DOT image reconstruction. Approaches like convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning models are being explored to automatically learn complex relationships between the measured data and the underlying optical properties of tissues, eliminating the need for traditional, explicit mathematical models. This shift towards machine learning offers the potential to enhance the capability of DOT by allowing it to process and interpret data more effectively.

The process of DOT image reconstruction continues to evolve, with ongoing efforts to refine the algorithms and techniques involved. These refinements are essential to fully unlock the capabilities of DOT as a non-invasive imaging tool in the biomedical field. As research in DOT advances, the integration of cutting-edge computational methods with experimental innovations will play a crucial role in overcoming current challenges. This combined progress is expected to significantly enhance the clinical application of diffuse optical tomography, expanding its usefulness in medical imaging and ultimately improving patient care.

4. Breast Cancer Detection using NIRS

Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is a non-invasive optical imaging technique that is particularly useful for examining soft tissues, such as breast tissue. By utilizing near-infrared (NIR) light, DOT allows for both the visualization of internal anatomical structures and the assessment of functional properties of tissues. The core principle behind DOT involves measuring the transmission or reflection of NIR light as it interacts with tissues. This process provides detailed information about the optical characteristics of the tissues, helping to map their internal properties.

A key feature of DOT is its model-based image reconstruction approach, which enables the calculation of important tissue components such as hemoglobin, water, and lipids. This method relies on the use of multiple light sources and detectors, making multiplexing techniques crucial for ensuring the rapid switching between light sources and detectors. These techniques are also vital for performing system calibration, helping to correct any potential inaccuracies in measurements and ensuring the reliability of the results.

The complexity of DOT instrumentation, with its array of components working in concert, highlights the advanced nature of the technology. It requires precise calibration and meticulous attention to detail to extract accurate, meaningful information from the optical imaging of breast tissues. Some advanced DOT systems utilize circular probes to conduct continuous spectroscopic imaging, allowing for real-time analysis of tissue properties, as demonstrated in previous studies. This ongoing refinement of DOT technology continues to enhance its diagnostic capabilities in medical imaging.

5. Challenges and Future Scope

The use of diffuse optical tomography (DOT) in medical imaging presents a significant challenge when it comes to estimating the internal optical properties of tissue based on measurements that are only obtained from the tissue’s outer boundary. This difficulty arises primarily due to the highly scattered nature of near-infrared (NIR) light as it travels through biological tissues. The scattering of light complicates the estimation process, making it what is known as an inverse problem—nonlinear, ill-posed, and sometimes underdetermined, meaning that there is insufficient data to solve the problem directly [

42].

Despite these challenges, various algorithms have been developed to allow for the rapid reconstruction of three-dimensional DOT images [

45,

46]. More recently, considerable efforts have been made to improve the speed of this image reconstruction process by leveraging the power of Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), which are capable of handling large amounts of data in parallel [

47,

48]. With the aid of GPUs, real-time imaging capabilities for DOT have been successfully demonstrated [

49]. Furthermore, innovations such as specialized instruments designed for high-speed imaging of specific tissue regions have been proposed, further advancing the potential of DOT for medical applications [

50,

51]. These ongoing developments continue to enhance the effectiveness and practicality of DOT as a diagnostic tool in clinical settings.

Despite the considerable size of DOT instruments and the slow data collection process, ongoing research work aims to lower instrument costs by incorporating Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) and photodetectors [

52,

53,

54]. Furthermore, DOT is being explored as a point-of-care imaging system [

55], with educational applications to teach students about optical medical imaging systems [

56,

57]. Addressing challenges during data collection, a practical method has been proposed, involving the measurement and subtraction of superficial noise from the signal of interest, proving effective in enhancing data accuracy [

58]. Notably, current research in this field is rapidly expanding, revealing the potential of NIR light in medical imaging for early-stage breast cancer detection and brain function imaging.

Despite the relatively large size of diffuse optical tomography (DOT) instruments and the time-consuming nature of data collection, there is ongoing research focused on reducing the cost of these instruments [

59]. One strategy involves incorporating more affordable components, such as Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) and photodetectors, to replace more expensive alternatives, which could make DOT technology more accessible and cost-effective [

52,

53,

54]. Additionally, DOT is being explored for use in point-of-care settings, allowing for more immediate and accessible imaging in medical environments [

55]. Beyond clinical applications, DOT is also being investigated for educational purposes, offering a valuable tool for teaching students about optical medical imaging systems and the underlying technologies [

56].

In addressing challenges encountered during the data collection process, a practical solution has been proposed to improve the accuracy of the collected data. This method involves measuring and then subtracting the superficial noise from the signal of interest, which has proven to be an effective way of enhancing data quality and reducing interference [

58]. As research in DOT continues to grow at a rapid pace, it is becoming increasingly clear that near-infrared (NIR) light holds great potential in medical imaging, particularly in the early detection of breast cancer and in imaging brain function. These advancements continue to expand the applicability and effectiveness of DOT in both clinical and research settings.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

In summary, the evolving field of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) for medical imaging, particularly in applications related to brain and breast health, demonstrates a complex and dynamic combination of progress, challenges, and future possibilities. The continued integration of NIRS with other complementary imaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) [

60], serves to enhance the depth, precision, and comprehensiveness of the information gathered from the body. However, challenges persist, particularly in achieving higher spatial resolution and addressing the influence of extracerebral tissues, which highlights the ongoing need for refinement in both the technology and methodology. Promising developments in signal processing techniques, as well as the fusion of multiple imaging modalities, are providing potential solutions.

In the realm of breast imaging, NIRS has emerged as a promising non-invasive technique for the early detection of breast cancer. Recent progress in spectral tomography and its integration with traditional imaging techniques, such as mammography, are driving advancements in the field. However, there are still significant hurdles to overcome, such as improving spatial resolution and addressing the heterogeneity of tissues, which require innovative approaches, such as the use of multi-wavelength and frequency-domain NIRS. As the technology continues to evolve, ongoing clinical trials are essential to validate the effectiveness of NIRS as a reliable diagnostic tool in breast cancer detection, helping to establish its role in clinical practice.

The paper concludes by discussing the potential future developments of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) in the field of medical imaging. In the context of brain imaging, the incorporation of sophisticated signal processing methods, particularly machine learning algorithms, offers significant promise in enhancing spatial localization and improving the ability to decode cognitive states. For breast imaging, the use of molecular-specific contrast agents, coupled with advancements in hardware technology, is expected to help overcome current limitations, enabling more accurate detection of tumors at earlier stages. As NIRS technology progresses, its capacity to address technical challenges, alongside its ability to integrate seamlessly with other imaging modalities, positions it as a valuable tool for routine clinical use in both brain and breast imaging. This paper contributes to the ongoing dialogue within the medical imaging community by offering a comprehensive technical overview of the current state of NIRS, the challenges it faces, and the exciting possibilities for its future application in the ever-evolving landscape of medical imaging.

References

- Althobaiti, M.; Al-Naib, I. Recent developments in instrumentation of functional near-infrared spectroscopy systems. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 6522.

- Huang, W.; Luo, S.; Yang, D.; Zhang, S. Applications of smartphone-based near-infrared (NIR) imaging, measurement, and spectroscopy technologies to point-of-care (POC) diagnostics. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B 2021, 22, 171. [CrossRef]

- Eleveld, N.; Esquivel-Franco, D.C.; Drost, G.; Absalom, A.R.; Zeebregts, C.J.; de Vries, J.P.P.; Elting, J.W.J.; Maurits, N.M. The influence of extracerebral tissue on continuous wave near-infrared spectroscopy in adults: A systematic review of in vivo studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 2776.

- Saikia, M.; Besio, W.; Mankodiya, K. WearLight: Toward a Wearable, Configurable Functional NIR Spectroscopy System for Noninvasive Neuroimaging. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Circuits and Systems 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Development of handheld near-infrared spectroscopic medical imaging system. Biophotonics Congress: Optics in the Life Sciences Congress 2019 (BODA,BRAIN,NTM,OMA,OMP) (2019), paper DS1A.6 2019, Part F168-BODA 2019, DS1A.6. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.; Forghani, F.; Campbell, C.; Bedford, S.; O’Sullivan, T.D. Method for Quantitative Broadband Diffuse Optical Spectroscopy of Tumor-Like Inclusions. Applied Sciences 2020, Vol. 10, Page 1419 2020, 10, 1419. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. A Spectroscopic Diffuse Optical Tomography System for the Continuous 3-D Functional Imaging of Tissue - A Phantom Study. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Fernández, J.D.; Roa-Tort, K.; Stolik, S.; Valor, A.; Fabila-Bustos, D.A.; de la Rosa, G.; Hernández-Chávez, M.; de la Rosa-Vázquez, J.M. Design of a low-cost diffuse optical mammography system for biomedical image processing in breast cancer diagnosis. Sensors 2023, 23, 4390.

- Okawa, S.; Hoshi, Y. A Review of Image Reconstruction Algorithms for Diffuse Optical Tomography. Applied Sciences 2023, Vol. 13, Page 5016 2023, 13, 5016. [CrossRef]

- Acuña, K.; Sapahia, R.; Jiménez, I.N.; Antonietti, M.; Anzola, I.; Cruz, M.; García, M.T.; Krishnan, V.; Leveille, L.A.; Resch, M.D.; et al. Functional Near-Infrared Spectrometry as a Useful Diagnostic Tool for Understanding the Visual System: A Review. Journal of clinical medicine 2024, 13, 282.

- Revealing the spatiotemporal requirements for accurate subject identification with resting-state functional connectivity: A simultaneous fNIRS-fMRI study.

- Chen, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhou, X.; Rosas, E.V.; Thomas, A.; Loureiro, R.; Cooper, R.J.; Carlson, T.; Zhao, H. fNIRS-EEG BCIs for Motor Rehabilitation: A Review. Bioengineering 2023, Vol. 10, Page 1393 2023, 10, 1393. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Chakraborty, D.; Saikia, M.J.; Dandapat, S.; Barma, S. Seizure Type Detection Using EEG Signals Based on Phase Synchronization and Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Body Sensor Networks (BSN). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Kim, N.; Borthakur, D.; Saikia, M.J. Examining Brainwave Patterns in Response to Familiar Music: An EEG and Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the SoutheastCon 2024. IEEE, 2024, pp. 758–763.

- Liampas, I.; Danga, F.; Kyriakoulopoulou, P.; Siokas, V.; Stamati, P.; Messinis, L.; Dardiotis, E.; Nasios, G. The Contribution of Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) to the Study of Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 663.

- Saikia, M.J.; Besio, W.G.; Mankodiya, K. The Validation of a Portable Functional NIRS System for Assessing Mental Workload. Sensors 2021, 21, 3810.

- Saikia, M.J.; Kuanar, S.; Borthakur, D.; Vinti, M.; Tendhar, T. A machine learning approach to classify working memory load from optical neuroimaging data. 2021, p. 69. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xia, Y.; Thomas, A.; Carlson, T.; Zhao, H. Mental Fatigue Classification with High-Density Diffuse Optical Tomography: A Feasibility Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5.

- Saikia, M.J. K-means Clustering Machine Learning Approach Reveals Groups of Homogeneous Individuals with Unique Brain Activation, Task, and Performance Dynamics using fNIRS. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, A.; Candia-Rivera, D.; Valenza, G. Multivariate Pattern Analysis of Entropy estimates in Fast- and Slow-Wave Functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy: A Preliminary Cognitive Stress study. Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS 2022, 2022-July, 373–376. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, K.; Saikia, M.J. Consumer-Grade Electroencephalogram and Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Neurofeedback Technologies for Mental Health and Wellbeing. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Shahbakhti, M.; Hakimi, N.; Horschig, J.M.; Floor-Westerdijk, M.; Claassen, J.; Colier, W.N. Estimation of respiratory rate during biking with a single sensor functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) system. Sensors 2023, 23, 3632.

- Abtahi, M.; Cay, G.; Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. Designing and testing a wearable, wireless fNIRS patch. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 10 2016, Vol. 2016-Octob, pp. 6298–6301. [CrossRef]

- Tsow, F.; Kumar, A.; Hosseini, S.H.; Bowden, A. A low-cost, wearable, do-it-yourself functional near-infrared spectroscopy (DIY-fNIRS) headband. HardwareX 2021, 10, e00204. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. A Wireless fNIRS Patch with Short-Channel Regression to Improve Detection of Hemodynamic Response of Brain. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 12 2018, pp. 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Mudalige, D.N.; Gamage, C.J.U.; Palihakkara, A.T.; Liyanagoonawardena, S.N.; De Silva, A.C.; Chang, T. Standalone Optode for Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Acquisition. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Industrial and Information Systems (ICIIS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 188–193.

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K. 3D-printed human-centered design of fNIRS optode for the portable neuroimaging. 2019, 10870, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Momtahen, S.; Shokoufi, M.; Ramaseshan, R.; Golnaraghi, F. Near-Infrared Handheld Probe and Imaging System for Breast Tumor Localization. IEEE Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2023, 46, 246–255. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Cay, G.; Gyllinsky, J.V.; Mankodiya, K. A Configurable Wireless Optical Brain Monitor Based on Internet-of-Things Services. 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer Technologies and Optimization Techniques, ICEECCOT 2018 2018, pp. 42–48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, L.; Cui, X.; Gao, Y. Application of portable near-infrared spectroscopy technology for grade identification of Panax notoginseng slices. Journal of Food Safety 2023, 43, e13033.

- Saikia, M.J. Internet of things-based functional near-infrared spectroscopy headband for mental workload assessment. SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11629, pp. 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Asadi, H.; Hoang, T.; Lim, C.P.; Nahavandi, S. Measuring Cognitive Load: Leveraging fNIRS and Machine Learning for Classification of Workload Levels. Communications in Computer and Information Science 2024, 1963 CCIS, 313–325. [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Garro, E.M.; Zhao, Y. EEG/fNIRS Based Workload Classification Using Functional Brain Connectivity and Machine Learning. Sensors 2022, 22, 7623. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Brunyé, T.T. K-means clustering for unsupervised participant grouping from fNIRS brain signal in working memory task. SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11629, pp. 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Patashov, D.; Menahem, Y.; Gurevitch, G.; Kameda, Y.; Goldstein, D.; Balberg, M. fNIRS: Non-stationary preprocessing methods. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2023, 79, 104110. [CrossRef]

- Ch Vidyasagar, K.E.; Revanth Kumar, K.; Anantha Sai, G.N.K.; Ruchita, M.; Saikia, M.J. Signal to Image Conversion and Convolutional Neural Networks for Physiological Signal Processing: A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66726–66764. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Z.; Saikia, M.J. Digital Twins for Healthcare Using Wearables. Bioengineering 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Álvaro de Oliveira Franco.; de Oliveira Venturini, G.; da Silveira Alves, C.F.; Alves, R.L.; Vicuña, P.; Ramalho, L.; Tomedi, R.; Bruck, S.M.; Torres, I.L.; Fregni, F.; et al. Functional connectivity response to acute pain assessed by fNIRS is associated with BDNF genotype in fibromyalgia: An exploratory study. Scientific Reports 2022 12:1 2022, 12, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Miller, K.D.; Kramer, J.L.; Newman, L.A.; Minihan, A.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Breast Cancer Statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2022, 72, 524–541. [CrossRef]

- Basic Information About Breast Cancer | CDC.

- Boyd, N.F.; Jensen, H.M.; Cooke, G.; Han, H.L.; Lockwood, G.A. Mammographic densities and the prevalence and incidence of histological types of benign breast disease. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2000, 9, 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Arridge, S.R. Optical tomography in medical imaging. Inverse Problems 1999, 15, R41. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J. Design and development of a functional diffuse optical tomography probe for real-time 3D imaging of tissue. SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11639, pp. 213–218.

- Saikia, M.J. An embedded system based digital onboard hardware calibration for low-cost functional diffuse optical tomography system. SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11632, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R.; Vasu, R.M. High-speed GPU-based fully three-dimensional diffuse optical tomographic system. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Dutta, P.K.; Saikia, M.J. Gaussian Distributed Semi-Analytic Reconstruction Method for Diffuse Optical Tomographic Measurement. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023.

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. High performance single and multi-GPU acceleration for Diffuse Optical Tomography. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 1 2014, pp. 1320–1323. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R.; Mohan Vasu, R. High-Speed GPU-Based Fully Three-Dimensional Diffuse Optical Tomographic System. International Journal of Biomedical Imaging 2014, 2014, 376456.

- Saikia, M.J.; Rajan, K.; Vasu, R.M. 3-D GPU based real time Diffuse Optical Tomographic system. Souvenir of the 2014 IEEE International Advance Computing Conference, IACC 2014 2014, pp. 1099–1103. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Development of DOT system for ROI scanning. Optical Society of America (OSA), 12 2014, p. T3A.4. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. Region-of-interest diffuse optical tomography system. Review of Scientific Instruments 2016, 87, 013701. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Alqasemi, U.; Chen, A.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Q. Light-emitting diode-based multiwavelength diffuse optical tomography system guided by ultrasound. 2014, 19, 126003. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Instrumentation in Diffuse Optical Imaging. Photonics 2014, Vol. 1, Pages 9-32 2014, 1, 9–32. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.; Manjappa, R.; Kanhirodan, R. A cost-effective LED and photodetector based fast direct 3D diffuse optical imaging system. 2017, Vol. 10412. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Mankodiya, K.; Kanhirodan, R. A point-of-care handheld region-of-interest (ROI) 3D functional diffuse optical tomography (fDOT) system. 2019, 10874, 295–300. [CrossRef]

- Saikia, M.J.; Kanhirodan, R. A tabletop Diffuse Optical Tomographic (DOT) experimental demonstration system. SPIE, 2 2019, Vol. 10869, p. 11. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Yan, J.; Yi, Z.; Korfhage, M.O.; Tong, S.; Zhu, C. Low-cost compact optical spectroscopy and novel spectroscopic algorithm for point-of-care real-time monitoring of nanoparticle delivery in biological tissue models. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2022, 29, 1–8.

- Saikia, M.J.; Manjappa, R.; Mankodiya, K.; Kanhirodan, R. Depth sensitivity improvement of region-of-interest diffuse optical tomography from superficial signal regression. OSA - The Optical Society, 6 2018, Vol. Part F99-C, p. CM3E.5. [CrossRef]

- Poorna, R.; Kanhirodan, R.; Saikia, M.J. Square-waves for frequency multiplexing for fully parallel 3D diffuse optical tomography measurement. SPIE, 2021, Vol. 11639, pp. 219–226. [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Borthakur, D.; Saikia, M.J. Machine Learning Approach for Music Familiarity Classification with Single-Channel EEG. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–4.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).