Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

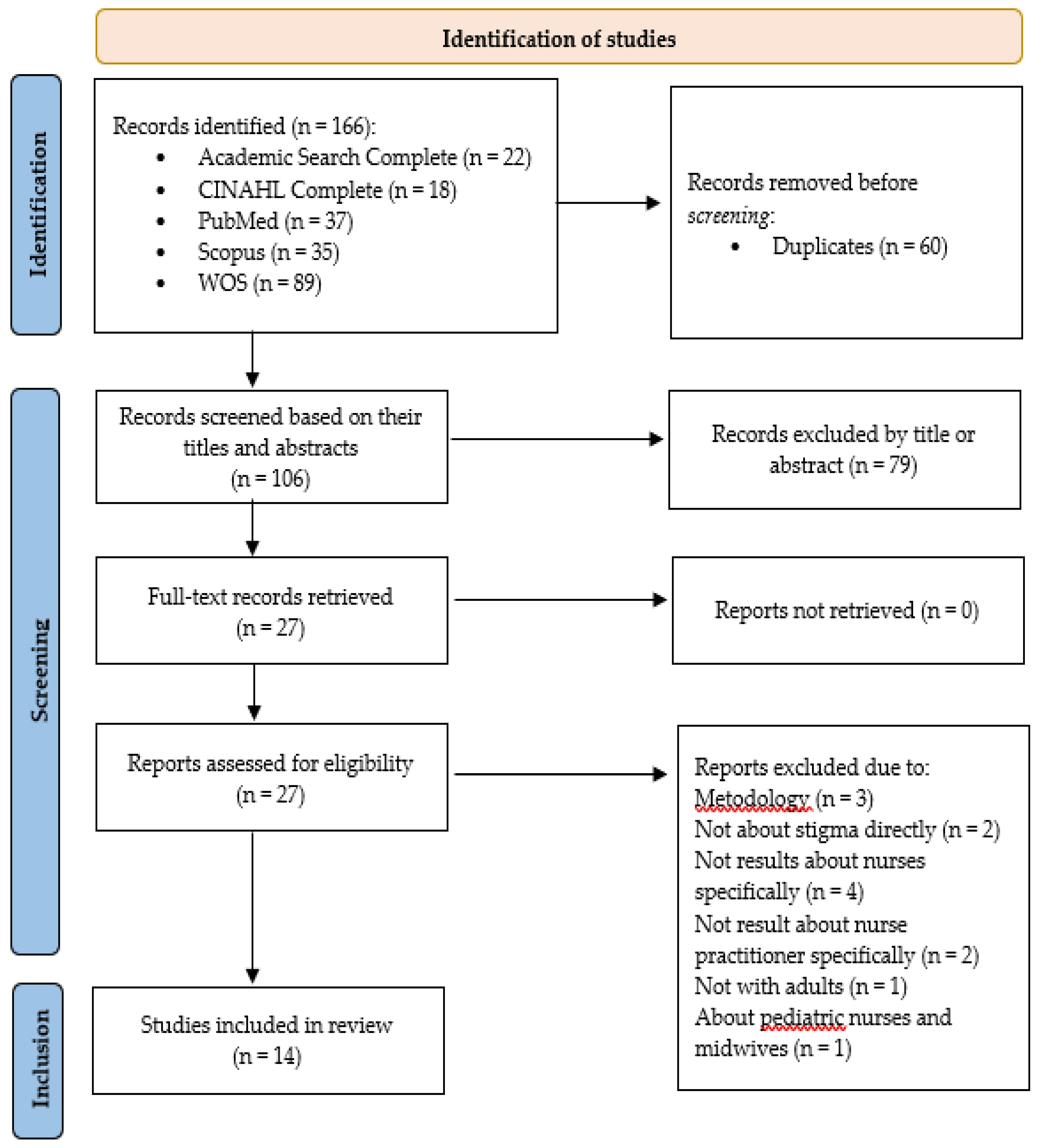

2. Materials and Methods

- Identification of the research question/problem.

- Identification of relevant studies through available literature.

- Selection of studies through evaluation based on eligibility criteria.

- Analysis of information and graphical representation of data.

- Compilation, summary, and presentation of the findings.

- Population: Nurses and nursing students.

- Concept: Experiences, opinions, beliefs, attitudes.

- Context: Health care for patients with obesity.

- Population: Terms identified included nurse, nursing staff, and nurse-patient relations.

- Concept: Terms identified included weight prejudice, bias, implicit, social stigma, and stereotyping.

- Context: Terms identified included obesity and overweight.

- Population characteristics: Studies focusing on nurses and nursing students, both male and female, were selected. Studies involving other health care professionals were included only if the majority of the results focused on nurses.

- Methodological design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies were selected.

- Concept: Studies addressing weight stigma in all its forms were included, whether focused on detecting it or on developing interventions and strategies to address it.

- Context: Studies in which the studied professionals provide health care to adult patients with obesity, both male and female, were selected. Articles published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, without geographical limitations, were included.

- Population characteristics: Studies focused on specialist nurses, particularly in obstetrics-gynecology, geriatrics, pediatrics, family and community care, and mental health. Studies involving children or adolescents were excluded.

- Methodological design: Grey literature, review articles, books, and editorials were excluded.

- Context: Studies in which health care professionals exclusively provide care to children or adolescents were excluded.

3. Results

3.1. General Aspects of the Included Studies

3.1.1. Instruments and Techniques Used

3.2. Main Findings

4. Discussions

4.1. Overview of Nurses' Attitudes and Behaviors

4.2. Contradictions and Complexities of the Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, 2022; ISBN 978-92-890-5773-8. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Graham, Y.; Hayes, C.; Cox, J.; Mahawar, K.; Fox, A.; Yemm, H. A systematic review of obesity as a barrier to accessing cancer screening services. Obesity science & practice 2022, 8, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.J.; Kerr, D.; Pollard, C.M.; Theophilus, M.; Alexander, E.; Haywood, D.; O’Connor, M. Weight bias among health care professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2021, 29, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palad, C.J.; Yarlagadda, S.; Stanford, F.C. Weight stigma and its impact on paediatric care. Current opinion in Endocrinology & Diabetes and obesity 2019, 26, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talumaa, B.; Brown, A.; Batterham, R.L.; Kalea, A.Z. Effective strategies in ending weight stigma in healthcare. Obesity Reviews 2022, 23, e13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubino, F.; Puhl, R.M.; Cummings, D.E.; Eckel, R.H.; Ryan, D.H.; Mechanick, J.I.; Nadglowski, J.; Ramos Salas, X.; Schauer, P.R.; Twenefour, D.; et al. Joint international consensus statement for ending stigma of obesity. Nature medicine 2020, 26, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. Estigma. La identidad deteriorada.; Amorrortu: Buenos aires, 2009; ISBN 9789505180165. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, R.L. Childhood obesity: issues of weight bias. Preventing chronic disease 2011, 8, A94. [Google Scholar]

- Lava, M.D.P.; Antún, M.C.; De Ruggiero, M.; González, V.; Mirri, M.E.; Rossi, M.L. Percepción de usuarios con exceso de peso sobre los factores que intervienen en la implementación de las pautas alimentarias sugeridas en la Consejería Nutricional del Programa Estaciones Saludables en la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Diaeta 2018, 36, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, S.M.; Bauer, K.W.; Bradley, D.; Bradley, S.M.; Haller, I.V.; Mundi, M.S.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; Schroeder, D.R.; Fischer, K.; Croghan, I. A model of weight-based stigma in health care and utilization outcomes: Evidence from the learning health systems network. Obesity science & practice 2021, 8, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberga, A.S.; Edache, I.Y.; Forhan, M.; Russell-Mayhew, S. Weight bias and health care utilization: a scoping review. Primary Health Care Research & Development 2019, 20, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Internacional de Enfermeras. Código de ética del CIE para las Enfermeras. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/2023-06/ICN_Code-of-Ethics_SP_WEB.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Brown, I. Nurses' attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: literature review. J Adv Nurs 2006, 53, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez, P.; Müggenburg, C. Relaciones personales entre la enfermera y el paciente. Enfermería Universitaria 2015, 12, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo Algarra, A.J.; García Serrano, L.; Cárdenas Orjuela, C.M.; Díaz Sánchez, I.R.; Yabrudy Wilches, N. La filosofía de Patricia Benner y la práctica clínica. Enfermería Global 2013, 12, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.R.; Padilha, M.I.; Petry, S.; Silva, E.; Silva, V.; Woo, K.; Galica, J.; Wilson, R.; Luctkar-Flude, M. Reviews of Literature in Nursing Research: Methodological Considerations and Defining Characteristics. Advances in Nursing Science 2022, 45, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biblioteca Virtual en Salud (BVS). DeCS/MeSH Descriptores en Ciencias de la Salud. Available online: https://decs.bvsalud.org/es/ (accessed on 01 August 2024).

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaida, Australia, 2020; ISBN 978-0-64884880-6. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Habibi, N.; Aromataris, E.; Stone, J.C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Sears, K.; Hasanoff, S.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Moola, S.; et al. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for quasi-experimental studies. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2024, 22, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Developed by the JBI Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation Working Party October 2013. Available online: https://acortar.link/UZqQ0e (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Barra, M.; Singh Hernandez, S.S. Too big to be seen: Weight-based discrimination among nursing students. Nursing forum 2018, 53, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, M. The attitudes towards obese persons scale (ATOPS). unpublished manuscript 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Darling, R.; Atav, A. Attitudes Toward Obese People: A Comparative Study of Nursing, Education, and Social Work Students. Journal of Professional Nursing 2019, 35, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.B.; Basile, V.C.; Yuker, H.E. The measurement of attitudes toward and beliefs about obese persons. International Journal of Eating Disorders 1991, 10, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, E. Effects of weight bias training on student nurse empathy: A quasiexperimental study. Nurse education in Practice 2023, 66, 103538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; DeSantis, J.; Gonnella, J.S. Patient Perceptions of Clinician’s Empathy:Measurement and Psychometrics. Journal of Patient Experience 2017, 4, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, C.; Gray, L.; Russell, L.; MacDonald, C. A Qualitative Study to Explore the Impact of Simulating Extreme Obesity on Health Care Professionals' Attitudes and Perceptions. Ostomy Wound Management 2018, 64, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, E.; Raque, T. Feasibility of a Loving Kindness Intervention for Mitigating Weight Stigma in Nursing Students: A Focus on Self-Compassion. Mindfulness 2023, 14, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, L.M.; Burke, N.L.; Thompson, J.K.; Dedrick, R.F.; Heinberg, L.J.; Calogero, R.M.; Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Higgins, M.K.; Frederick, D.A.; Kelly, M.; et al. Development and validation of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4). Psychol Assess 2015, 27, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.E.; Schwartz, J.L. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L.; Tugade, M.M.; Waugh, C.E.; Larkin, G.R. What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003, 84, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.P.; Vander Wal, J.S. The cognitive flexibility inventory: Instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cognitive therapy and research 2010, 34, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F.; Pommier, E.; Neff, K.D.; Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Seomun, G. Development and validation of an instrument to measure nurses' compassion competence. Appl Nurs Res 2016, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, S.; Connor, K.; Quatraro, M.; Dye, J. Changes in weight bias after simulation in pre-license baccalaureate nursing students. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 2023, 18, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, J.G.; Scheltema, K.E.; Robinson, B.E. Fat phobia scale revisited: the short form. International Journal of Obesity 2001, 25, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.L.; Qi, B.-B.; Diewald, L.K.; Shenkman, R.; Kaufmann, P.G. Development of a weight bias reduction intervention for third-year nursing students. Clinical obesity 2021, 12, e12498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, T.L.; Shenkman, R.; Diewald, L.K.; Dowdell, E.B. Nursing students' perspectives on observed weight bias in healthcare settings: A qualitative study. Nursing Forum 2021, 56, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaydin, T.; Tuncbeden, M. An investigation of the prejudice and stigmatization levels of nursing students towards obese individuals. Archieves of Psychiatric Nursing 2022, 40, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, E.; Güngör, H. Değerler Eğitimi Dergisi, 2013; 11, 251–270. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/ded/issue/29175/312427.

- Robstad, N.; Westergren, T.; Siebler, F.; Söderhamn, U.; Fegran, L. Intensive care nurses' implicit and explicit attitudes and their behavioural intentions towards obese intensive care patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) 2019, 75, 3631–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.B.; Chambliss, H.O.N.; Brownell, K.D.; Blair, S.N.; Billington, C. Weight Bias among Health Professionals Specializing in Obesity. Obesity Research 2003, 11, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C.S. Prejudice against fat people: ideology and self-interest. Journal of personality and social psychology 1994, 66, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robstad, N.; Siebler, F.; Söderhamn, U.; Westergren, T.; Fegran, L. Design and psychometric testing of instruments to measure qualified intensive care nurses' attitudes toward obese intensive care patients. Research in Nursing & Health 2018, 41, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.; Ruiz-Iglesias, A.; González-López, J. Changes in anti-fat attitudes among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Education Today 2020, 95, 104584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanneberger, A.; Ciupitu-Plath, C. Nurses' Weight Bias in Caring for Obese Patients: Do Weight Controllability Beliefs Influence the Provision of Care to Obese Patients? Clinical Nursing Research 2018, 27, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.J.; Cash, T.F.; Jacobi, L.; Bubb-Lewis, C. Prejudice toward fat people: the development and validation of the antifat attitudes test. Obes Res 1997, 5, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, T.; DeCristofaro, C.; Murphy, P. Unconscious Weight Bias Among Nursing Students: A Descriptive Study. Healthcare 2019, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assemi, M.; Cullander, C.; Hudmon, K.S. Implementation and Evaluation of Cultural Competency Training for Pharmacy Students. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2004, 38, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.; Ayhan, N. Is there prejudice against obese persons among health professionals? A sample of student nurses and registered nurses. Perspective in Psychiatric Care 2019, 55, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Mangione, S.; Nasca, T.J.; Cohen, M.J.M.; Gonnella, J.S.; Erdmann, J.B.; Veloski, J.; Magee, M. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement 2001, 61, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercan, A.; AkÇİL Ok, M.; Kiziltan, G.; Altun, S. SAĞLIK BİLİMLERİ ÖĞRENCİLERİ İÇİN OBEZİTE ÖNYARGI ÖLÇEĞİNİN GELİŞTİRİLMESİ: GAMS 27-OBEZİTE ÖNYARGI ÖLÇEĞİ. International Peer-Reviewed Journal of Nutrition Research 2015, 2, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.; Brownell, K.D. Bias, Discrimination, and Obesity. Obesity research 2001, 9, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gailey, J.A. The Violence of Fat Hatred in the “Obesity Epidemic” Discourse. Humanity & Society 2022, 46, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, D. El estigma de la obesidad y su impacto en la salud: una revisión narrativa. Endocrinología, Diabetes y Nutrición 2022, 69, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lara, K.M.; Cruz-Millán, A.C.; Barrera-Hernandez, L.F.; Valbuena-Gregorio, E.; Ayala-Burboa, M.O.; Hernández-Lepe, M.A.; Olivas-Aguirre, F.J. Mitigating Weight Stigma: A Randomized Controlled Trial Addressing Obesity Prejudice through Education among Healthcare Undergraduates. Obesities 2024, 4, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.H.; Oliver, T.L.; Randolph, J.; Dowdell, E.B. Interventions for reducing weight bias in healthcare providers: An interprofessional systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Obes 2022, 12, e12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawickrama, R.S.; Hill, B.; O'Connor, M.; Flint, S.W.; Hemmingsson, E.; Ellis, L.R.; Du, Y.; Lawrence, B.J. Efficacy of interventions aimed at reducing explicit and implicit weight bias in healthcare students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews 2024, e13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachman, B.A.; Brownell, K.D. Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune? International Journal of Obesity 2001, 25, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Kaufononga, A.; Yovich, F.; Diversi, T. The prevalence and practice impact of weight bias among New Zealand registered dietitians. Nutrition & Dietetics 2023, 80, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Xumet, J.-E.; García-Hernández, A.-M.; Fernández-González, J.-P.; Marrero-González, C.-M. Beyond scientific and technical training: Assessing the relevance of empathy and assertiveness in future physiotherapists: A cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports 2023, 6, e1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuguero, O.; Esquerda, M.; Viñas, J.; Soler-Gonzalez, J.; Pifarré, J. Ética y empatía: relación entre razonamiento moral, sensibilidad ética y empatía en estudiantes de medicina. Revista Clínica Española 2019, 219, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocquier, A.; Verger, P.; Basdevant, A.; Andreotti, G.; Baretge, J.; Villani, P.; Paraponaris, A. Overweight and obesity: knowledge, attitudes, and practices of general practitioners in france. Obesity research 2005, 13, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuan, J.F.; Avignon, A. Obesity management: attitudes and practices of French general practitioners in a region of France. International Journal of Obesity 2005, 29, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués Andrés, S. Formación continuada: herramienta para la capacitación. Enfermería Global 2011, 10. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1695-61412011000100020&nrm=iso. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.L.; Cheng, H.; Duffield, C.; Denney-Wilson, E. The relationship between patient obesity and nursing workload: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2021, 30, 1810–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrara, F.S.A.; Zanei, S.S.V.; Cremasco, M.F.; Whitaker, I.Y. Outcomes and nursing workload related to obese patients in the intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 2016, 35, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikorski, C.; Luppa, M.; Glaesmer, H.; Brähler, E.; König, H.-H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Attitudes of Health Care Professionals towards Female Obese Patients. Obesity Facts 2013, 6, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, E.; Bayram, S.; Altınbaş Akkaş, Ö. Perceptions of nursing students about individuals with obesity problems: Belief, attitude, phobia. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 2021, 57, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Cortina, A.; López Rebolledo, M. Bases teóricas del estigma, aproximación en el cuidado de personas con herpes genital. Index de Enfermería 2011, 20, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Judgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct; Guilford Press: New York, NY, US, 1995; ISBN 0-89862-843-1. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P.; Markowitz, F.E.; Watson, A.; Rowan, D.; Kubiak, M.A. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of health and Social Behavior 2003, 162–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauser, D.R.; Ciftci, A.; O'Sullivan, D. Using attribution theory to examine community rehabilitation provider stigma. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2009, 32, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The Primacy of Self-Regulation in Health Promotion. Applied Psychology: An International Review 2005, 54, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina Souza Santos, T.; Campos Victor, J.; Ribeiro Dias, G.; Cosmo de Moura Balbino, A.; Jaime, P.C.; Lourenço, B.H. Self-efficacy among health professionals to manage therapeutic groups of patients with obesity: Scale development and validity evidences. Journal of Interprofessional Care 2023, 37, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annesi, J.J.; Stewart, F.A. Self-regulatory and self-efficacy mechanisms of weight loss in women within a community-based behavioral obesity treatment. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myre, M.; Berry, T.R.; Ball, G.D.C.; Hussey, B. Motivated, fit, and strong—Using counter-stereotypical images to reduce weight stigma internalisation in women with obesity. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2020, 12, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, E.; Interlenghi, G.; Leite, T.; Cunha, D.; Junior, E.V.; Steffen, R.; Azeredo, C. Primary care–based interventions for treatment of obesity: A systematic review. Public Health 2021, 195, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Domínguez, B. Investigación cualitativa y psicología social crítica. Contra la lógica binaria y la ilusión de la pureza. Dossier Investigación Cualitativa en Salud, Revista Universidad de Guadalajara 2008, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera Aguilaga, M.T. The qualitative research. Educar 1986, 10, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otálvaro, G.; Páramo Bernal, P.F. Investigación alternativa: Por una distinción entre posturas epistemológicas y no entre métodos. Cinta de Moebio, 2006; 1–7. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1996988.

- Nogales Espert, A. Cuidados de Enfermería en el siglo XXI: una mirada hacia el arte de cuidar. 2011; 41–55. Available online: https://acortar.link/TQlaz7.

- Lawrence, B.; Kerr, D.; Pollard, C.; Theophilus, M.; Alexander, E.; Haywood, D.; O'Connor, M. Weight bias among health care professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. OBESITY 2021, 29, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bibliographic Resources | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| Academic Search Complete | ( obesity or body weight or overweight ) AND ( nurse or nursing staff or Nurse-Patient Relations ) AND ( weight prejudice or bias, implicit or social stigma or Stereotyping ) |

| CINAHL Complete | ( obesity or body weight or overweight ) AND ( nurse or nursing staff or Nurse-Patient Relations ) AND ( weight prejudice or bias, implicit or social stigma or Stereotyping ) |

| PubMed | ( obesity or body weight or overweight ) AND ( nurse or nursing staff or Nurse-Patient Relations ) AND ( weight prejudice or bias, implicit or social stigma or Stereotyping ) |

| Web of Science | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( obesity OR "body weight" OR overweight ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( nurse OR "nursing staff" OR "Nurse-Patient Relations" ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( "weight prejudice" OR "bias, implicit" OR "social stigma" OR stereotyping ) |

| Scopus | ((TS=(obesity or body weight or overweight )) AND TS=(nurse or nursing staff or Nurse-Patient Relations)) AND TS=(( weight prejudice or bias, implicit or social stigma or Stereotyping )) |

| Author (year). Country. Design. |

Objetives | Subjects or Participants | Instruments and techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barra et al. (2018) [29]. United States. Quantitative. |

To determine the effectiveness of an awareness program on obesity. | Nursing students (n=103). Third- and fourth-year students. |

A weekly educational intervention was conducted. Before and after the intervention, participants completed the Attitudes Toward Obese Persons Scale (ATOPS) [30] and a questionnaire specifically designed for this study. |

| Darling et al. (2019) [31]. United States. Quantitative. |

To evaluate undergraduate and postgraduate students' attitudes toward individuals with obesity and compare nursing students with those from other professions. | Undergraduate and postgraduate nursing students (n=403), postgraduate education students (n=35), and postgraduate social work students (n=88). | The Attitudes Toward Obese Persons Scale (ATOP) and the Beliefs About Persons Scale (BAOP) [32] were used. |

| Gajewski et al. (2023) [33]. United States. Quantitative. |

To evaluate the effectiveness of educational activities focused on weight bias to promote empathy. | Nursing students (n=2021). First-year students. |

Weight bias learning activities were conducted. The Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Health Professions Students (JSE-HPS) was used pre- and post-intervention. A simulation scenario was employed, followed by the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Nurse Empathy (JSPPNE) [34] completed by the individual participating in the simulation. |

| Hales et al. (2018) [35]. New Zeland. Qualitative. |

To explore the impact of using a simulation suit on participants' attitudes and perceptions. | Registered nurses (n=6) and a registered physiotherapist (n=1) who regularly treated individuals with obesity. | A semi-structured individual interview was conducted pre- and post-simulation with a suit designed to mimic the shape and size of a person with obesity. Additionally, a pre-simulation questionnaire with five open-ended questions about perceptions of the daily challenges faced by people with obesity was completed. |

| Joseph et al. (2023) [36]. United States. Quantitative. |

To determine the effectiveness of Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) in reducing weight bias. | Nursing students (n=189). Loving-Kindness Meditation (LKM) condition (n=80). Control condition (n=109) |

Both groups participated in a meditation session. The intervention group practiced LKM, while the control group engaged in a mindfulness-based body scan meditation. Both sessions lasted 10 minutes and were guided through an audio recording. Before the intervention, the thinness-related subscale from the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4) [37] was used. After the meditation sessions, the following variables were measured by the researchers: Weight bias: IAT [38] was used. Positive emotions: The Modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES) [39] was employed. Cognitive flexibility: The Cognitive Flexibility Inventory (CFI) [40] was utilized. Self-compassion: The Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF) [41] was applied. Compassionate care: The Compassion Competence Scale (CCS) [42] was administrated. Attitudes toward individuals with obesity: ATOP [32] acted as an instrument. |

| Llewellyn et al. (2023) [43]. United States. Mixed Methods. |

To evaluate weight bias in nursing students pre- and post-intervention using a communication tool and a simulation test. | Nursing students. Participants in the pre-survey (n=47) and post-survey (n=73). First semester. |

The instruments used included the Fat Phobia Scale (FPS) [44], the Beliefs About Persons Scale (BAOP) [32] and open-ended questions, administered before and after a didactic course introducing the LEARN model. This model is based on patient-centered communication, emphasizing the patient's concerns. |

| Oliver et al. (2022) [45]. United States. Quantitative. |

To evaluate the effectiveness of incorporating deeper modules into Weight Bias Reduction (WBR) programs that promote self-reflection and critical thinking to improve attitudes and beliefs toward individuals with obesity. | Nursing students (n=99). Participants in the intervention group: (n=46). Participants in the control group: (n=53). Third-year students. |

All participants completed the ATOP and BAOP [32] questionnaires before and after each intervention. Intervention group: Received a WBR program with more intensive content. This intervention included weight-based case studies. Control group: Received the standard program. |

| Oliver et al. (2021) [46]. United States. Qualitative. |

To explore nursing students' reflections on weight bias in healthcare settings. | Nursing students (n=197). Third-year students. |

A reflective journal was used, where students progressively answered five questions over 15 weeks. |

| Ozaydin et al. (2022) [47]. Turkey. Quantitative. |

To determine levels of prejudice and stigma toward individuals with obesity. | Nursing students (n=233). Second-, third-, and fourth-year students. |

The GAMS-27 Obesity Prejudice Scale and the Stigma Scale [48] were used. Data was collected through an online link providing access to the described questionnaires. |

| Robstad et al. (2019) [49]. Norway. Quantitative. |

To examine the explicit and implicit attitudes of intensive care unit (ICU) nurses toward patients with obesity and whether these attitudes are associated with their intentional behaviors. | Qualified ICU nurses (n=159). Participants were registered nurses with 1.5 years of continuous training in ICU care or a 2-year master’s degree in intensive care. |

An online questionnaire was used, incorporating the following scales: Implicit bias: IAT [38]. Explicit bias: A scale based on specific stereotypes assessed in the IAT to rate feelings on a seven-point differential scale [50]. The Anti-Fat Attitude (AFA) questionnaire [51] was also used. Behavioral intention: Four vignettes were presented, and participants rated the likelihood of the described scenarios occurring in real life on a seven-point semantic scale (from very likely to very unlikely) [52]. |

| Rodríguez-Gázquez et al. (2020) [53]. Spain. Quantitative. |

To analyze changes in negative attitudes toward obesity throughout academic training. | Nursing students (n=578). First-, second-, third-, and fourth-year students. |

The AFA questionnaire [51] was applied, and data were collected in person during courses with the highest attendance rates. |

| Tanneberger et al. (2018) [54]. Germany. Quantitative. |

To determine the belief that patients with obesity receive different care compared to non-obese individuals and to evaluate whether beliefs about weight control influence clinical practice. | Nurses in an intensive care clinic (n=73). | The Weight Control/Blame (WCB) subscale of the Antifat Attitudes Test (AFAT) [55] was used. Additional questions, rated similarly to the utilized subscale, were included to gather data on the frequency of providing care to people with obesity, the quality and availability of resources used in their care, and the perception of whether nurses or their colleagues treated individuals with obesity differently compared to those with acceptable weight. Participants were also given the option to provide free-text responses to elaborate on perceived discrimination toward these patients. |

| Tracy et al. (2019) [56]. United States. Quantitative. |

To determine whether explicit attitudes align with implicit beliefs. | Nursing students (n=69). First semester. |

A modified pre-survey questionnaire was used to evaluate cultural competence and communication [57], asking respondents to declare their preferences for fat or thin individuals, followed by the IAT [38] to assess unconscious preference for thin people. |

| Yilmaz et al. (2019) [58]. Turkey. Quantitative. |

To evaluate whether prejudice toward people with obesity exists. | Nursing students (n=190) and licensed nurses (n=189). | Two scales were used: the Fat Phobia Scale (FPS) [44] and the Beliefs About Obese Persons Scale (BAOP) [32]. |

| Author (year) | Main results | JBI |

|---|---|---|

| Barra et al. (2018) [29]. | The pre-intervention survey revealed that more than half of the students held negative opinions toward patients with obesity. A significant positive change in students' biases was observed after the training sessions, with students expressing remorse upon recognizing that their weight biases impacted the quality of care provided. | 6 out of 9 points on the critical appraisal checklist for quasi-experimental studies. Level of Evidence: II |

| Darling et al. (2019) [31]. | No differences were found between male and female scores on either scale. However, older participants were associated with more positive beliefs and attitudes. Nursing students appeared to have less positive attitudes compared to students from other professions. | 6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV |

| Gajewski et al. (2023) [33]. | Empathy levels were high both before and after the learning activities. In one cohort, significant changes in empathy levels were demonstrated before and after the intervention. Female participants scored higher in empathy compared to males. | 6 out of 9 points on the critical appraisal checklist for quasi-experimental studies. Level of Evidence: II |

| Hales et al. (2018) [35]. | Participants experienced the challenges faced by individuals with obesity, gaining a deeper understanding of how this condition affects physical challenges and social interactions, often resulting in social isolation. The use of simulation suits among health care professionals had a positive impact on reducing weight stigma. | 9 out of 10 points on the critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research. Level of Evidence: III |

| Joseph et al. (2023) [36]. | Participants in the intervention group experienced significantly higher levels of emotions such as gratitude and love. No significant differences were found in other variables, such as self-compassion, weight bias, cognitive flexibility, compassionate care, or positive attitudes toward individuals with obesity. These findings suggest that a 10-minute exposure may not be sufficient to yield significant differences. Additionally, baseline data were not collected to avoid participant bias. | 11 out of 13 points on the critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials. Level of Evidence: I. |

| Llewellyn et al. (2023) [43]. | Quantitative Results: Significant differences were observed, with respondents being less likely to agree that obesity results from a lack of love, overeating, or lack of physical exercise. Positive trends were also noted regarding qualities such as strength, self-control, and resilience. Qualitative Results: Students adopted a less weight-centered approach, focusing more on the individual and tailoring care to the patient's needs. |

6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. 7 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies. Level of Evidence: III. |

| Oliver et al. (2021) [45]. | BAOP scores, reflecting beliefs about individuals with obesity, improved significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group. However, no significant changes were observed in the ATOP scale results, which measure attitudes toward individuals with obesity. | 11 out of 13 points on the critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials. Level of Evidence: I. |

| Oliver et al. (2021) [46]. | Observed Implicit and Explicit Weight Bias: Students reported that nurses made derogatory comments to patients with obesity. Weight Bias Due to External Factors: Students noted that caring for patients with obesity posed a greater burden compared to patients of acceptable weight, partly due to the lack of an accommodating environment for treating these individuals. These aspects created a contrast between what students learned about weight bias and their clinical practice experiences. |

9 out of 10 points on the critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research. Level of Evidence: III. |

| Ozaydin et al. (2022) [47]. | High levels of prejudice and stigmatization toward individuals with obesity were detected, with a positive correlation between stigmatization and prejudice levels. Fourth-year students demonstrated significantly higher prejudice levels than younger students. No differences were found for other variables such as gender, place of residence, BMI of the respondent, economic level, the presence of first-degree relatives with obesity, or interactions with individuals with obesity during clinical practice. | 8 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV |

| Robstad et al. (2019) [49]. | A greater preference for thin individuals was detected, both in implicit and explicit attitudes. No association was found between explicit and implicit attitudes and the self-reported weight of the study participants. However, male participants scored higher in the belief that individuals with obesity have less willpower. Explicit and implicit attitudes were not associated with behavioral intention. | 6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV. |

| Rodríguez-Gázquez et al. (2020) [53]. | First-year students scored higher overall on the scale, indicating a stronger attitude against obesity. Female participants showed lower values in terms of aversion and perceived willpower. Attitudes became less negative as academic years progressed. | 6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV. |

| Tanneberger et al. (2018) [54]. | A significant association was found between healthcare professionals' weight control beliefs and their perception that individuals with obesity were treated differently compared to those of acceptable weight, both by their colleagues and by the professionals themselves. Weight control beliefs were the only significant factor predicting the perception of discrimination by nurses toward patients with obesity. Nurses reported a lack of adequate resources, which increased the perception that care required greater intensity. |

6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV. |

| Tracy et al. (2019) [56]. | More than 65% of respondents demonstrated a significant difference between their self-reported attitudes toward individuals with obesity and the results of the IAT on implicit attitudes. No relationship was found between the BMI of the respondent and their preference for body mass in others. | 6 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV |

| Yilmaz et al. (2019) [58]. | The majority of nursing students and licensed nurses reported negative attitudes and beliefs toward individuals with obesity. In both the FPS and BAOP results, the proportion of negative responses was significantly higher among licensed nurses compared to nursing students. Participants with obesity exhibited more positive attitudes, and having relatives with obesity was also associated with a more positive attitude. | 7 out of 8 points on the critical appraisal checklist for cross-sectional analytical studies. Level of Evidence: IV. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).