1. Introduction

Influenza is an acute viral infection that spreads easily from person to person and can affect any age group (Paules, 2017). Each year influenza epidemics strain health services as well as take an economic toll through hospitalizations and work absenteeism. The genomes of influenza viruses are highly plastic and prone to mutations and interspecies transmission (Han, 2023). Consequently, new strains of influenza viruses that humans have little resistance to can emerge and cause devastating pandemics (Kandeil, 2023). Combating influenza outbreaks is challenging. Vaccination can be one of the most effective means for preventing influenza outbreaks. However, continuous antigenic drift of circulating viruses mandates yearly updates to the influenza vaccine composition and likely provides limited protection against novel pandemic strains. Antiviral drugs offer the promise of treatment (Hayden, 2022) although resistance to antivirals has grown markedly high in some influenza strains (Yin, 2021). The limitation of current vaccines and antivirals makes the development of new strategies for prevention and treatment of influenza a worldwide healthcare priority.

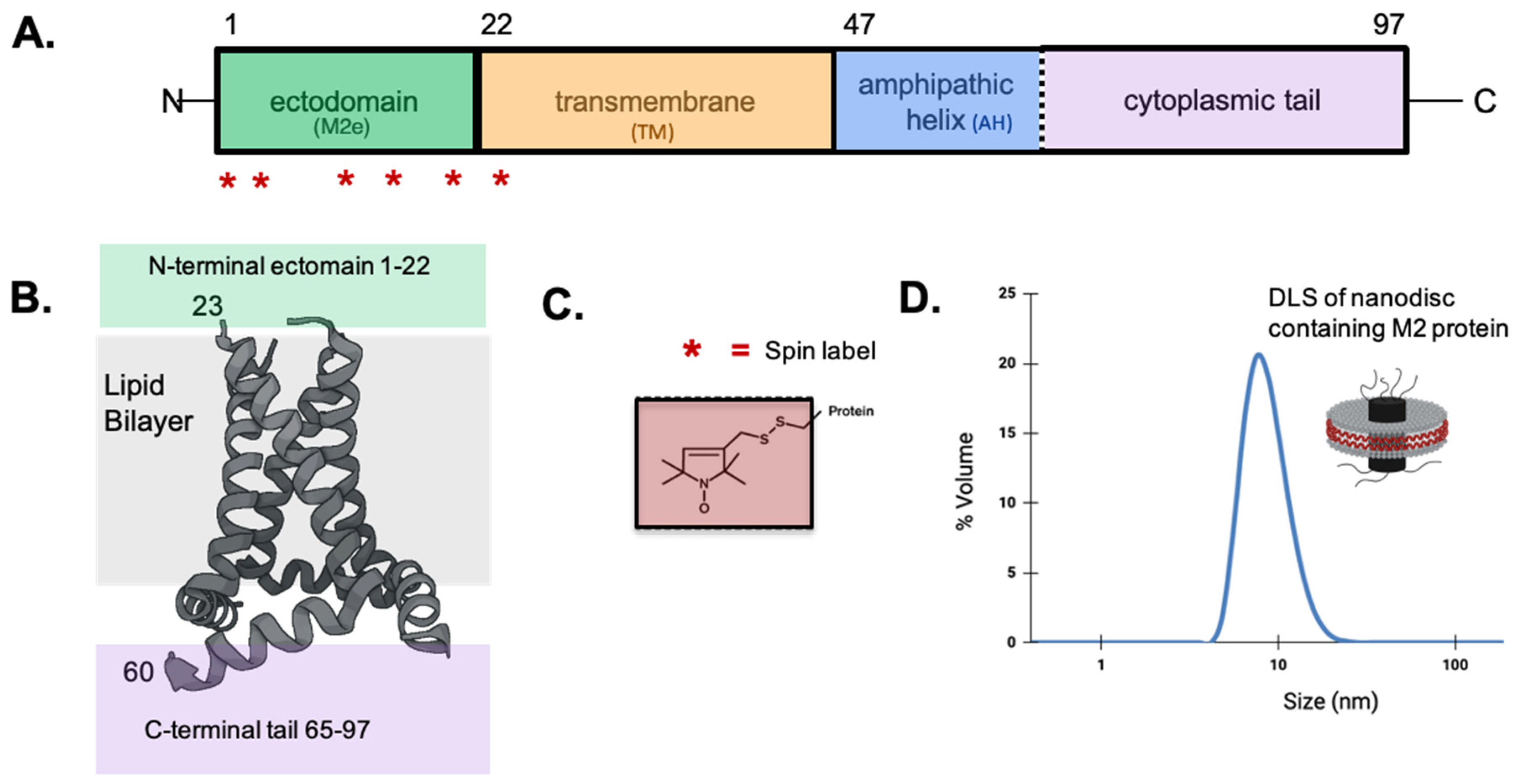

Fundamental information on the influenza virus life cycle and the structural properties of the viral components are still being uncovered. There has been sustained interest in matrix protein 2 (M2), which resides in the coat of the influenza virus as well as the plasma membrane of an infected cell. The M2 protein is a 97-amino acid membrane-bound protein that functions as a homotetramer (

Figure 1). The M2 protein has been studied by a wide range of biophysical techniques (Gu, 2013). Each monomer consists of an N-terminal ectodomain (M2e), a transmembrane domain (TM), and a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain containing an amphipathic helix (AH) followed by a mobile tail. The tetrameric TM is a four-helix bundle that acts as a proton channel which promotes uncoating of virions upon entrance to a host cell. The AH plays important roles in viral budding and morphology (Kim, 2019). M2e has been linked to the successful incorporation of M2 into nascent virions (Park, 1998) and has generated intense attention as a target for universal influenza vaccines (Schepens, 2018) and novel antiviral strategies (Matthys, 2024; Yu, 2023).

The sequence of M2e is highly conserved among humans, as well as in swine and avian strains (Mezhenskaya, 2019). The potential for cross-species mixing that could lead to a pandemic outbreak makes M2e a particularly powerful target for a universal vaccine. The high conservation of M2e likely results from its genetic overlap with the open reading frame of the influenza matrix protein 1 (Schepens, 2018). Monoclonal antibodies toward M2e have been developed, and their therapeutic potential has been explored. Several M2e-based vaccines are undergoing clinical trials (Mezhenskaya, 2019).

In this paper we provide insight into the properties of M2e using site-directed spin labeling electron paramagnetic resonance (SDSL-EPR). SDSL-EPR is a technique exquisitely suited for detecting the mobility and membrane topology of membrane proteins reconstituted into lipid bilayers (Klug, 2008). SDSL-EPR has been previously used to study the C-terminal extramembranous domain of full-length M2 protein (Kyaw, 2023; Kim, 2019; Herneisen, 2017; Kim, 2015; Huang, 2015) which provides valuable context in interpretation of M2e data.

Partial models for the conformation of M2e have been proposed (Schepens, 2018). Two x-ray structures of short M2e peptides bound to protective monoclonal antibodies have been published (Cho, 2015; Cho, 2016). The folds of the M2e peptides differ in the two complexes, but both include a turn. A solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance model (ssNMR) suggested beta-strand character within M2e based on chemical shift patterns (Liao, 2013). Another ssNMR study proposed that M2e is unstructured and dynamic (Kwon, 2016). The observation that M2e appears unstructured under some conditions, yet can form secondary structure motifs in other conditions, has been hypothesized to result from M2e's ability to shift between different unique conformations (Schepens, 2018). In this paper we designed our experiments to avoid artifacts that could result from using a truncated protein or excluding a membrane surface. Thus, we measured conformational properties of M2e within a full-length M2 protein embedded in lipid bilayers. We also probed how M2e was impacted upon the addition of each of two molecules (cholesterol and antiviral drug) previously shown to modify the properties of the other domains of M2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Expression, Spin Labeling, and Purification of Spin-Labeled Full Length M2 Protein

Single cysteine substitutions were introduced into a cysteine less background plasmid based on the A/Udorn/72 M2 sequence (Leiding, 2010) using site-directed mutagenesis (Sequences are shown in

Figure S1). To minimize potential perturbation caused by the replacement of a residue with a nitroxide spin-label, we used only one label at a time, chose a spin-label that is similar in size to a natural amino and probed multiple proximal sites within the M2e domain to provide valuable internal comparison of measured values. A wide range of studies on M2 have shown the introduction of a single cysteine outside the TM core has led to only minor changes in the function in the majority of cases (Pinto, 1997; Shuck, 2000).

Full-length M2 protein was over-expressed and purified using methods previously optimized in our laboratory (Herneisen, 2017). Briefly, a C-terminal His-tagged protein is expressed in E. coli cells and purified using nickel affinity chromatography. A spin label was covalently linked via a disulfide linkage to the introduced cysteines with the S-(1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-pyrrol-3-yl) methyl methanesulfonate (MTSL) spin label.

2.2. Reconstitution of Spin-Labeled M2 Protein Into Nanodiscs

Full-length M2 protein was reconstituted into nanodiscs using a protocol optimized in our lab (Kyaw, 2023). Briefly, we assembled nanodiscs with a membrane bilayer consisting of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC, Avanti Polar Lipids): 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG, Avanti Polar Lipids) in a molar ratio of 4:1. This lipid mix has been used in functional assays of M2 (Rossman, 2011) and previous M2 SDSL-EPR studies (Kyaw, 2023; Kim, 2019; Herneisen, 2017). Native mass spectrometry demonstrated that M2-nanodiscs composed of bilayered lipids with a similar hydrophobic thickness to our lipids selectively contained tetrameters (Townsend, 2021). Based on the mean surface area needed to accommodate tetrameric M2 protein (Hagn, 2018) we used the membrane scaffold protein construct called MSP1D1. The molar ratio of M2:MSP1D1:POPC/POPG lipids was 4:2:130 (Kyaw, 2023). The mixture was incubated for 2 h at 4°C. 1.5 g of Biobeads (Bio-Rad) was mixed with 20 mM Tris pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl and degassed. The Biobeads were added in 3 equal aliquots; the first two aliquots 2 hrs apart and the third was incubated for an additional 12 h. After Biobead removal, the nanodisc solution was passed through a 0.45 μm filter and characterized using dynamic light scattering.

2.3. Composition of Cholesterol and Drug Samples

Cholesterol-containing lipid films were prepared by adding a 30% molar fraction of cholesterol to 4:1 POPC:POPG lipid preparations, in accordance with previous literature (Herneisen, 2017). Nanodiscs were then prepared identically to non-cholesterol-containing samples.

Rimantadine drug films were prepared at a 1:20 molar ratio of M2 tetramer-to-rimantadine, in accordance with previous literature (Kyaw, 2023). Standard nanodiscs were prepared, concentrated, and then allowed to incubate on rimantadine films for 24-48 hours before analysis via SDSL-EPR.

2.4. Dynamic Light Scattering

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to measure the sizes of nanodiscs to confirm proper nanodisc formation. Nanodisc samples were spun at 14,000 rpm in a benchtop microfuge for 10 minutes to remove any large particulates prior to DLS measurement. DLS was collected on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS using 1 cm pathlength cuvettes. Data were reported as an average of five measurements.

2.5. EPR Spectroscopy and Data Analysis

Continuous wave (CW) and power saturation spectra were collected on an X-band Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with an ER4123S resonator at room temperature. CW spectra were acquired in gas-permeable TPX capillary tubes using 2 mW incident microwave power, 1 G field modulation amplitude at 100 kHz, and a 150 G sweep width. The number of scans varied in accordance with signal quality, ranging from 3-9 scans. The dynamics of a spin-labeled site were assessed from the CW EPR line shape using a semi-empirical mobility factor (Klug, 2008) calculated from the inverse peak-to-peak width of the central line (ΔH0−1). For power saturation spectra, experiments were performed under nitrogen gas or equilibrated with ambient air. EPR spectra were collected over eight power levels for nitrogen power saturation experiments and 16 power levels for oxygen power saturation. The number of scans varied in accordance with signal quality, which was determined during CW spectra collection. Data were fit to obtain ΔP1/2 parameters as described previously and errors reported as 95% confidence intervals from the fits to the power saturation curves (Nguyen, 2008).

3. Results

To probe the conformational properties and membrane topology along M2e, we generated six different constructs of the full-length M2 protein, each with a single spin label spread out along the 23-residue domain (Sequences are shown in

Figure S1). Five out of the six sites we looked at (L4, I11, E14, R18 and D21) were previously site-specifically studied in a ssNMR study on M2e (Kwon, 2016) which provide valuable context to compare our results. To minimize potential perturbation caused by the replacement of a residue with a nitroxide spin-label, we used only one label at a time, chose a spin-label that is similar in size to a natural amino and probed multiple proximal sites within the M2e domain to provide valuable internal comparison. We have previously sequentially placed nitroxide spin labels at over 25 sites in the other domains of M2 protein (Kyaw, 2023; Kim, 2019; Herneisen, 2017; Kim, 2015; Huang, 2015, Thomaston, 2013, Nguyen, 2008).

In this paper, the spin-labeled proteins were reconstituted into lipid bilayer nanodiscs as described in the Materials and Methods. As presented in detail below, EPR data on the mobility and accessibility to paramagnetic relaxation agents of sites along M2e are used to build conformational models.

3.1. Dynamic Properties of Sites Along the Ectodomain

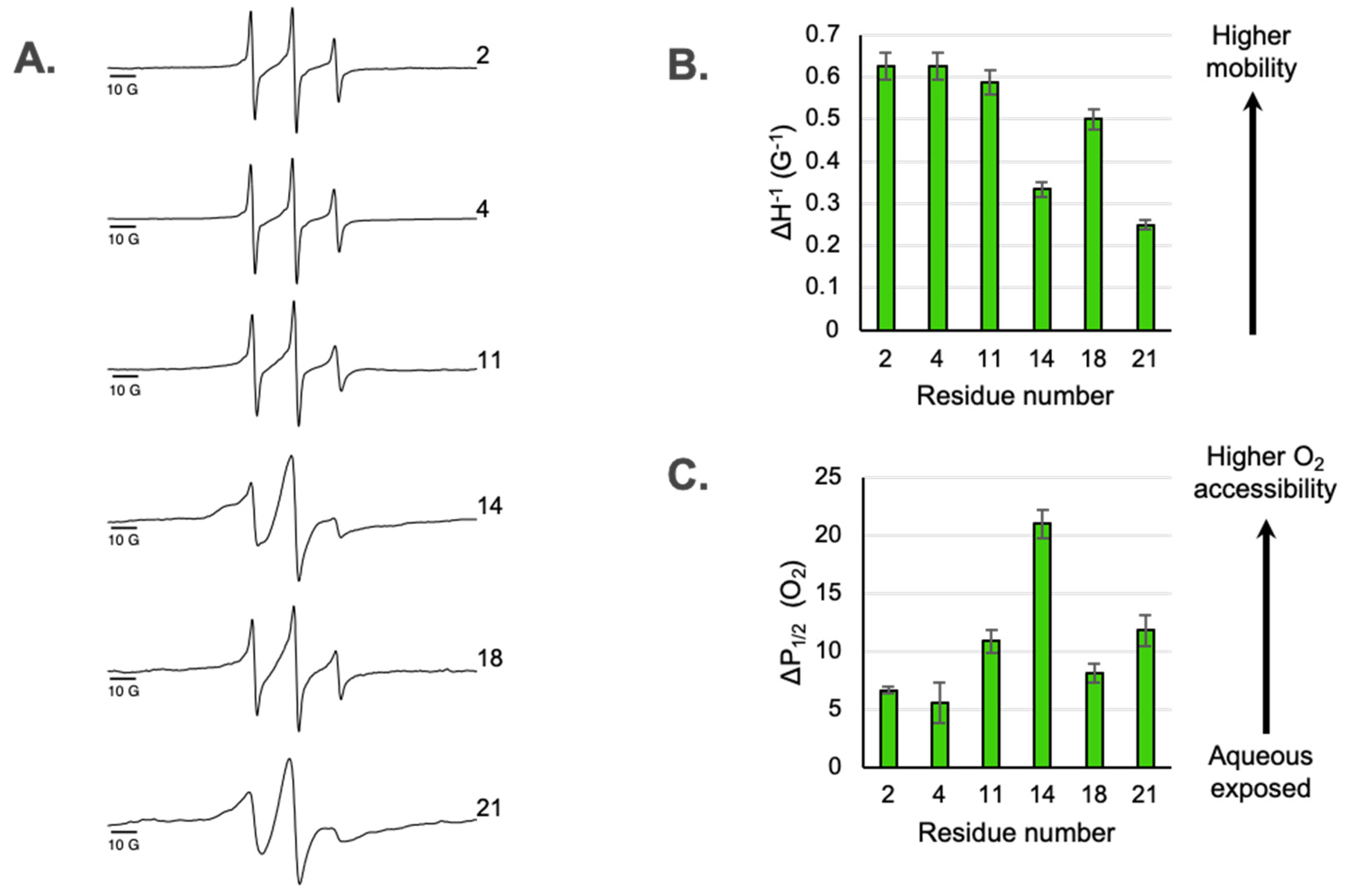

The EPR line shapes of spin-labeled residues on a membrane protein provide insight into conformational dynamics and secondary structure (Klug, 2008). The X-band CW EPR line shapes for the six spin labeled sites located in M2e are shown in

Figure 2A. The dynamics of a spin-labeled site can be assessed from the line shape using a semi-empirical mobility factor (Klug, 2008) calculated from the inverse peak-to-peak width of the central line (ΔH

0−1) (

Figure 2B). If the ectodomain is disordered and simply extends from the membrane surface, one would expect that the mobility would smoothly increase moving from the sites closest to the TM domain toward the N-terminal tail. However, we observe a deviation from that predicted pattern. While site 21 closest to the TM domain is substantially immobilized compared to site 2 near the end of N-terminal tail, site 14 located near the middle of the ectodomain is immobilized compared to the sites on either side of it.

The line shapes of the two most immobilized sites in M2e (site 14 and 21) exhibit multicomponent nature (

Figure 2). The superposition of a broad, immobilized component and a sharper, mobile component is most pronounced for site 14. Expanded spectra highlighting the multicomponent nature of line shapes is shown in

Figure S2.

The C-terminal AH was previously shown to have multicomponent EPR spectra which were extensively characterized using both CW EPR line shape analysis and pulsed EPR saturation recovery methods (Kim, 2019; Hernesein, 2017). That work along with a range of complementary biophysical methods from different groups established the presence of an equilibrium involving at least two different conformational substates of the C-terminal AH.

3.2. Accessibility to Paramagnetic Relaxation Agents Along the Ectodomain

Power saturation experiments have been widely used in SDSL-EPR of membrane protein to determine a residue’s accessibility to paramagnetic reagents such as hydrophobic O2 and water-soluble paramagnetic reagent (nickel(II) ethylenediaminediacetate, NiEDDA) (Klug, 2008) O2 preferentially partitions into lipid bilayers and NiEDDA is a hydrophilic compound that remains in the aqueous phase. Previously, our lab has integrated O2 collision frequencies with the collision frequency of NiEDDA for both the amphipathic helix (Nguyen, 2008) and the cytoplasmic tail (Kim, 2019) and calculated of an empirical contrast parameter, ϕ, that combines accessibilities of O2 and NiEDDA. For example, analysis of spin-labels placed along sites 50–60 in M2 identified a sinusoidal variation in oxygen accessibility with a periodicity of 3.6, characteristic of a surface-associated alpha helix. We have noted that the NiEDDA variation along the AH (the extramembranous region on the opposite side of the membrane from M2e) is much smaller than the corresponding O2 variation which often fell within error of the experiment (Nguyen, 2008). We therefore prioritized O2 power saturation data in this first report on M2e.

If the ectodomain linearly extends from the membrane surface and O2 accessibility simply reflects membrane depth, one would expect that the O2 accessibility would smoothly decrease as one moved from the sites closest to the TM domain out to the N-terminus. However, we observe a deviation from this predicted pattern at site 14. While site 21 closest to the TM domain shows higher oxygen accessibility than site 2 near the N-terminal tail, site 14 deviates from this pattern and is more accessible to O2 than sites on either side of it. One possible interpretation is that site 14 is more exposed to the hydrophobic membrane than nearby sites, which is consistent with site 14 being part of a membrane embedded turn.

Derivatives of bilayer-forming lipids with spin-labels attached at different carbon atoms positions on the hydrocarbon chains have been used in the past as depth gauges for membrane bilayers (Subczynski, 2009) but quantitative distances near the membrane surface is complicated by a lack of distance calibration points near and above the glycerol backbone (Frazier, 2002). Depth gauges for reference points within the hydrophobic interior of nanodiscs with the sample composition used in this paper have been reported (Kyaw, 2023). The P

1/2 (O

2) values for two depth gauges are shown in

Table S1 and provide reference points for the values we report here. In addition we can compare the oxygen accessibilities in M2e with previously published values on M2's C-terminal AH (

Figure 4). Note M2e site 14 is more oxygen accessible than the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic C-terminal helix (site 57). The oxygen accessibility of the site closest to the N-terminus (site 2) is similar to that measured for the site closest to the C-terminus (site 82).

3.3. Impact of Cholesterol and Drug Upon Properties of M2e

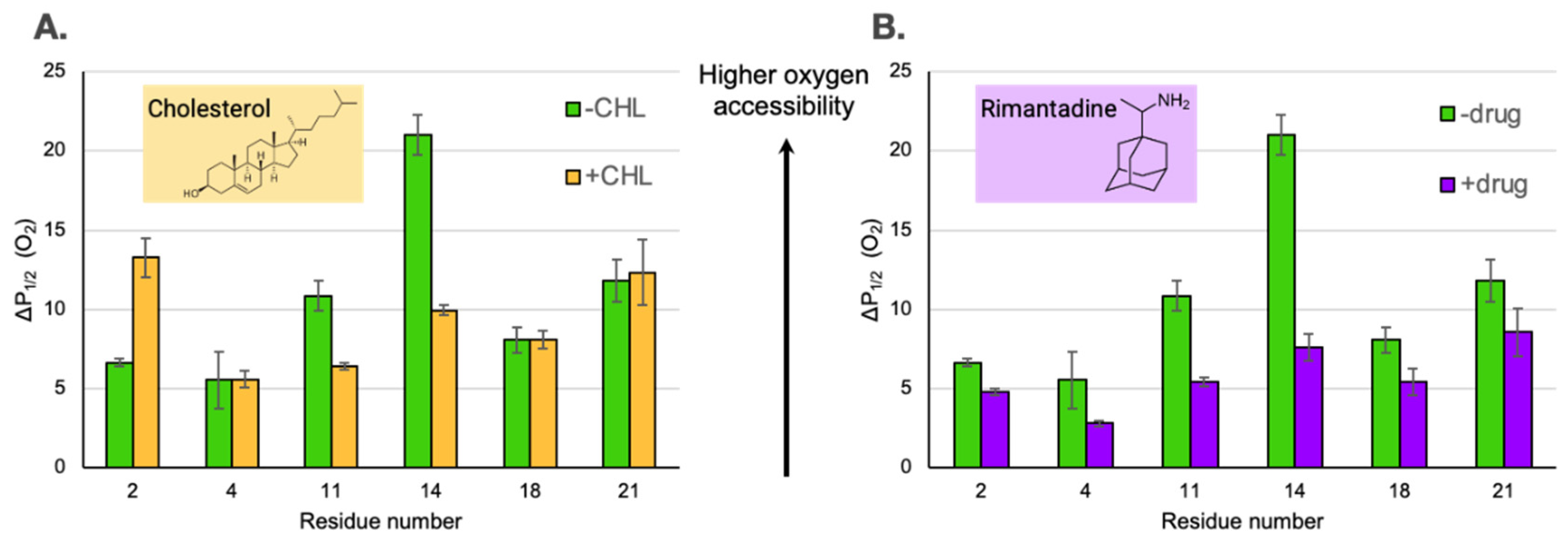

Upon the addition of cholesterol and drug, there are only minor changes in M2e CW-line shapes (

Figure S2). The mobility factors calculated from the line shapes do not change within error. However, M2e sites do exhibit marked changes in oxygen accessibility (

Figure 3) upon the addition of cholesterol and drug

The addition of cholesterol can decrease the oxygen permeability of membrane bilayers (Subczynski, 1989) which complicates the straightforward interpretation of cholesterol induced changes on membrane protein structure. In our previous work with the same lipid composition as this paper, we saw an ~30% decrease in oxygen accessibility for lipid based depth gauges (Kim, 2015). Intriguingly the changes in O

2 accessibility for M2e site 14 is larger than expected for just the impact of cholesterol on O

2 permeability, sites 4 and 18 don't show an impact of cholesterol at all and site 2 shows an increase in O

2 (

Figure 3A). This pattern of changes in O

2 accessibility suggest that more is going on than just cholesterol induced oxygen permeability and perhaps changes in secondary structure or proximity to the membrane surface is leading to the observed data.

Upon addition of drug, the P

1/2 (O

2) for site 11 decreases by a factor of ~2 and site 14 decreases by a factor of ~3 (

Figure 3B). These changes are consistent with the center of the M2e domain moving away from the membrane surface. The biologically relevant binding site for the rimantadine drug is located within the N-terminal half of the TM channel (Gu, 2013) and a range of biophysical strategies have demonstrated drug induced conformational and dynamic changes in the protein (Kumar, 2024).

4. Discussion

The mobility and oxygen accessibility results reported above provide a rich source of data to build models for M2e. As described below, current understanding of the other domains of the M2 protein provide valuable context in which to interpret the novel results we report here for M2e.

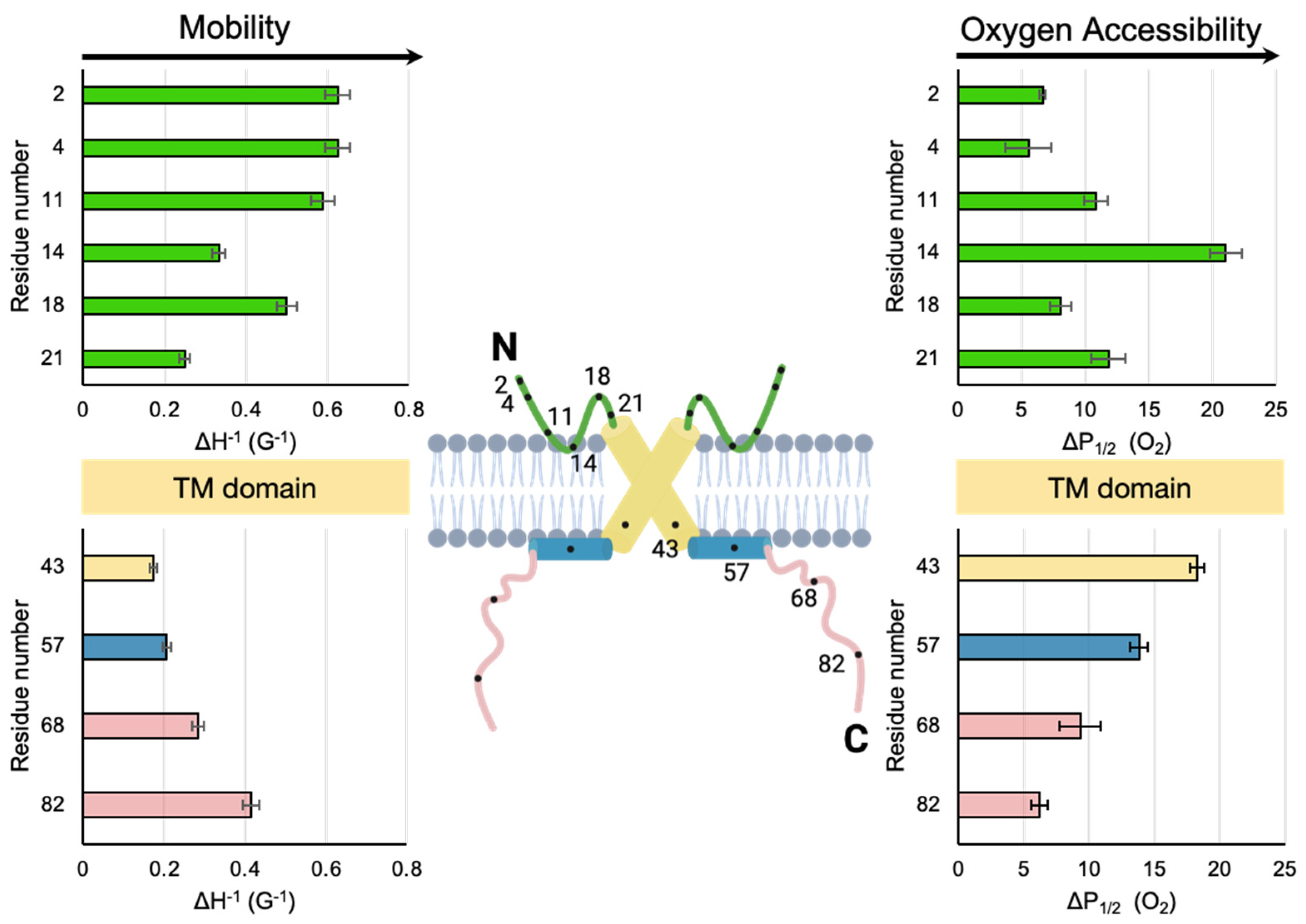

4.1. Comparison of the Two Extramembranous Domains of M2

It is useful to compare the SDSL-EPR data reported here for M2e to the more extensively studied C-terminal domain of M2. The mobility factors and O2 accessibility factors of the two extramembranous M2 domains are shown side by side in Figure. 4. The 50 residue C-terminal domain consists of a proximal AH that lies on the membrane surface (Huang, 2015) followed by a distal cytoplasmic tail that dynamically extends from the membrane (Kim, 2019). In terms of mobility, the least dynamic site (smallest ΔH0−1) for both the N-terminal domain (site 21) and C-terminal domain (site 43) is the site closest to the membrane embedded TM domain. Conversely the sites closest to both the N-termini (sites 2 and 4) and C-termini (site 82) are highly dynamic.

For the C-terminal domain, the trends in mobility and accessibility are inversely related, which has been attributed to membrane binding being a primary determinant of reduced motion of a site (Kim, 2019). For the N-terminal domain, the pattern of mobility also mirrors oxygen accessibility. For example, site 14 has low mobility and high oxygen accessibility. This observation is consistent with an immobilized membrane embedded turn (

Figure 4).

The TM and C-terminal domains of M2 protein have been previously demonstrated to have multiple low-energy conformational states (Yi, 2009; Hu, 2011; Kim, 2015). Thus it is not surprising that M2e would sample multiple conformations as suggested by the multicomponent lineshapes seen in

Figure 2A and

Figure S2. Plasticity in the packing of the four helices in the TM could propagate out to the N-terminal and C-terminal extramembranous domains. The loop regions that connect the TM to the extramembranous domains could act as flexible hinges that allow for different packing arrangements and membrane depths. The M2 protein has at least two functions: the proton channel activity crucial for uncoating of virions (Pinto, 2006) and the generation of curvature of the plasma membranes of infected cells essential for viral budding (Rossman, 2011). The virion and plasma membrane have different compositions, and the properties of M2 are exquisitely sensitive to membrane composition (Duong-Ly, 2005; Kim, 2015).

Our hypothesis based on multicomponent line shapes suggests M2e (like the other parts of M2) samples different conformational states is in agreement with previously published work that showed the potential of the ectodomain to have different folds, yet appear disordered in other studies (Cho, 2015; Cho, 2016; Kwon, 2016). It is unclear how a highly flexible M2e could serve as an antigen for high affinity M2e-specific antibodies, but theories have been proposed in the literature (Schepens, 2018). The details of how M2e-vaccines operate are still being determined. M2e-specific antibodies have very low binding to the surface of virions. Instead, the protective effect of anti-M2e antibodies likely results from a binding event to M2e on the surface of infected cells that triggers the removal of infected cells. Thus, high resolution details of the conformation of the ectodomain of M2 protein embedded in a lipid membrane that mimics the plasma membrane could be valuable in elucidating the atomic level interactions of M2 protein with the immune system.

4.2. Putative Membrane Insertion Motif Within the Ectodomain

Previously published work provides clues for why M2e might includes a membrane embedded turn. Arg/Trp pairs are a well-known motif for the interaction of peptides with membrane surfaces (Chan, 2006). For example, antimicrobial peptides which rely on membrane interaction for their function are often Trp and Arg rich and contain a well-defined turn between the two residues (Chan, 2006). M2e contains a highly conserved Arg/Trp pair in the middle of the domain (Arg12 and Trp15).

Aromatic residues are capable of strong cation-π interactions with Arg residues. A cation-π interaction with an aromatic residue makes the insertion of a charged Arg residue into the hydrophobic membrane energetically more favorable. Once the insertion of an Arg into the membrane surface is facilitated by a cation-π interaction with an aromatic residue, Arg can hydrogen bond with other species at the lipid interface. We hypothesize that a cation-π interaction promotes the formation of a membrane-embedded turn in M2e (

Figure 4) that could lead to the high O

2 accessibility and low mobility in the region near site 14.

4.3. Cholesterol and the Ectodomain

M2 is known to cluster in cholesterol-rich lipid rafts during viral budding from the host cell (Dou, 2018; Paulino, 2019) and there has been extensive interest in the impact of cholesterol on the conformational properties of M2 (Martyna, 2020; Ekanayake, 2016; Kim, 2015). The fact cholesterol can impact the intrinsic oxygen permeability of a membrane bilayer complicates the interpretation of the accessibility data we report in this paper. However, previously published work has shown that cholesterol reduces the membrane depth of the C-terminal AH which was hypothesized to result from a condensing effect on the lipid bilayer that decreases the ability of the membrane associated AH to penetrate into the membrane (Kim, 2015). The same movement away from the membrane surface upon the addition of cholesterol may be happening for M2e (

Figure S3). Alternatively, cholesterol-induced changes in the TM that result from direct cholesterol binding or constrained TM movement in the rigidified bilayer have been hypothesized to lead to changes in the C-terminal domain through interdomain coupling (Herneisen, 2017). The changes that cholesterol induces in the TM could be propagated to M2e and lead to a change in membrane proximity.

4.4. Drug Binding Impacts Ectodomain Properties

As shown in

Figure 3, drug binding reduces the O

2 accessibility of all sites on M2e, with the most marked changes occurring near site 14 in the middle of the domain. This is consistent with M2e moving away from the membrane surface upon drug binding (

Figure S3).

Adamantane drugs (including rimantadine which is used in this study) contain a hydrophobic adamantane group and a positively charged ammonium group. These drugs have been widely used models for influenza antiviral development although more than 90% of circulating influenza A strains are currently resistant (Jalily, 2020). The biologically relevant binding site for rimantadine is located within the N-terminal half of the TM channel with the large hydrophobic adamantane group located near Val27 and Ala30 and the positively charged ammonium group pointed down towards the His37 residues (Gu, 2013).

Electrophysiological experiments have shown that an ectodomain-truncated M2 construct has a weaker drug affinity than full-length M2 protein (Ohigashi, 2009) which one study attributes to the ectodomain modulating the conformation and dynamics of the TM (Kwon, 2016). Adamantane drug binding has been shown to narrow the wild-type TM channel and reduce its motion (Kumar, 2024). The impact of drug binding on the C-terminal AH has been explored by both ssNMR (Ekanayke, 2016) and SDSL-EPR (Thomaston, 2013). The C-terminal AHs are more closely packed in the presence of drugs, likely due to being tethered to the drug-immobilized TM (Thomaston, 2013). In addition, most membrane-embedded sites on the C-terminal AH move away from the membrane upon the addition of adamantane drugs. This is consistent with M2e moving away from the membrane surface upon drug binding (

Figure S3).

5. Conclusions

In the face of high levels of antiviral drug resistance and constantly evolving influenza strains, the high level of conservation of the M2e makes it a promising target for a universal influenza vaccine and antiviral drug. A key step towards advances in disease prevention and treatment is solving the structure of M2e. To best mimic the native environments of M2 and maximize the biological relevance of our work, we used full-length M2 protein embedded in lipid bilayer membranes. We studied multiple sites along the length of M2e and measured both mobility factors and O2 accessibility in order to elucidate structure and dynamics of M2e. Our data are consistent with the presence of a membrane embedded turn in the middle of the ectodomain potentially facilitated by a cation-π interaction between Arg12 and the nearby aromatic residue at site 15. The addition of cholesterol and of the antiviral drug rimantadine change the O2 accessibility of M2e, especially near the proposed membrane embedded turn. Growing interest in M2e-targeting nanobody drugs highlights the need for a high-resolution understanding of the structure and dynamics of M2e in different biologically and medically relevant environments (Yu, 2023). The data reported here provide a valuable resource for developing antiviral drugs and vaccines, and may allow for improved and targeted methods for generating M2e antibodies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. Sequences of the six different constructs of the full-length M2 protein. Figure S2. Overlay of X-band CW EPR line of spin-labeled M2 reconstituted into nanodiscs in the presence of cholesterol and rimantadine drug. Figure S3. Proposed models for M2e in the presence of cholesterol and rimantadine drug . Table S1. ΔP1/2 values for spin-labels on M2 protein embedded in nanodiscs.

Author Contributions

Kyra Roepke: Conceptualization; Investigation; Formal Analysis; Visualization; Writing – Review & Editing. Kathleen Howard: Conceptualization; Supervision; Visualization; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Review & Editing; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [GM134497-01] to KPH and Swarthmore College.

Acknowledgments

TPX capillary tubes were generously provided by Candice Klug in the Biophysics Department at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

References

- Chan, D. I., Prenner, E. J., & Vogel, H. J. (2006). Tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptides: Structures and mechanisms of action. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 1758(9), 1184–1202. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K. J., Schepens, B., Moonens, K., Deng, L., Fiers, W., Remaut, H., & Saelens, X. (2016). Crystal Structure of the Conserved Amino Terminus of the Extracellular Domain of Matrix Protein 2 of Influenza A Virus Gripped by an Antibody. Journal of Virology, 90(1), 611–615. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K. J., Schepens, B., Seok, J. H., Kim, S., Roose, K., Lee, J.-H., … Kim, K. H. (2015). Structure of the Extracellular Domain of Matrix Protein 2 of Influenza A Virus in Complex with a Protective Monoclonal Antibody. Journal of Virology, 89(7), 3700–3711. [CrossRef]

- Dou, D., Revol, R., Östbye, H., Wang, H., & Daniels, R. (2018). Influenza A Virus Cell Entry, Replication, Virion Assembly and Movement. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 1581. [CrossRef]

- Duong-Ly, K. C., Nanda, V., DeGrado, W. F., & Howard, K. P. (2005). The conformation of the pore region of the M2 proton channel depends on lipid bilayer environment. Protein Science, 14(4), 856–861. [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, E. V., Fu, R., & Cross, T. A. (2016). Structural Influences: Cholesterol, Drug, and Proton Binding to Full-Length Influenza A M2 Protein. Biophysical Journal, 110(6), 1391–1399. [CrossRef]

- Frazier, A. A., Wisner, M. A., Malmberg, N. J., Victor, K. G., Fanucci, G. E., Nalefski, E. A., … Cafiso, D. S. (2002). Membrane Orientation and Position of the C2 Domain from cPLA2 by Site-Directed Spin Labeling. Biochemistry, 41(20), 6282–6292. [CrossRef]

- Gu, R.-X., Liu, L. A., & Wei, D.-Q. (2013). Structural and energetic analysis of drug inhibition of the influenza A M2 proton channel. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 34(10), 571–580. [CrossRef]

- Hagn, F., Nasr, M. L., & Wagner, G. (2018). Assembly of phospholipid nanodiscs of controlled size for structural studies of membrane proteins by NMR. Nature Protocols, 13(1), 79–98. [CrossRef]

- Han, A. X., De Jong, S. P. J., & Russell, C. A. (2023). Co-evolution of immunity and seasonal influenza viruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 21(12), 805–817. [CrossRef]

- Hayden, F. G., Asher, J., Cowling, B. J., Hurt, A. C., Ikematsu, H., Kuhlbusch, K., … Monto, A. S. (2022). Reducing Influenza Virus Transmission: The Potential Value of Antiviral Treatment. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 74(3), 532–540. [CrossRef]

- Herneisen, A. L., Sahu, I. D., McCarrick, R. M., Feix, J. B., Lorigan, G. A., & Howard, K. P. (2017). A Budding-Defective M2 Mutant Exhibits Reduced Membrane Interaction, Insensitivity to Cholesterol, and Perturbed Interdomain Coupling. Biochemistry, 56(44), 5955–5963. [CrossRef]

- Hu, F., Luo, W., Cady, S. D., & Hong, M. (2011). Conformational plasticity of the influenza A M2 transmembrane helix in lipid bilayers under varying pH, drug binding, and membrane thickness. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 1808(1), 415–423. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Green, B., Thompson, M., Chen, R., Thomaston, J., DeGrado, W. F., & Howard, K. P. (2015). C-terminal juxtamembrane region of full-length M2 protein forms a membrane surface associated amphipathic helix. Protein Science, 24(3), 426–429. [CrossRef]

- Jalily, P. H., Duncan, M. C., Fedida, D., Wang, J., & Tietjen, I. (2020). Put a cork in it: Plugging the M2 viral ion channel to sink influenza. Antiviral Research, 178, 104780. [CrossRef]

- Kandeil, A., Patton, C., Jones, J. C., Jeevan, T., Harrington, W. N., Trifkovic, S., … Webby, R. J. (2023). Rapid evolution of A(H5N1) influenza viruses after intercontinental spread to North America. Nature Communications, 14(1), 3082. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G., Raymond, H. E., Herneisen, A. L., Wong-Rolle, A., & Howard, K. P. (2019). The distal cytoplasmic tail of the influenza A M2 protein dynamically extends from the membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 1861(8), 1421–1427. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S., Upshur, M. A., Saotome, K., Sahu, I. D., McCarrick, R. M., Feix, J. B., … Howard, K. P. (2015). Cholesterol-Dependent Conformational Exchange of the C-Terminal Domain of the Influenza A M2 Protein. Biochemistry, 54(49), 7157–7167. [CrossRef]

- Klug, C. S., & Feix, J. B. (2008). Methods and Applications of Site-Directed Spin Labeling EPR Spectroscopy. In Methods in Cell Biology (Vol. 84, pp. 617–658). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G., & Sakharam, K. A. (2024). Tackling Influenza A virus by M2 ion channel blockers: Latest progress and limitations. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 267, 116172. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, B., & Hong, M. (2016). The Influenza M2 Ectodomain Regulates the Conformational Equilibria of the Transmembrane Proton Channel: Insights from Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biochemistry, 55(38), 5387–5397. [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, A., Roepke, K., Arthur, T., & Howard, K. P. (2023). Conformation of influenza AM2 membrane protein in nanodiscs and liposomes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 1865(5), 184152. [CrossRef]

- Leiding, T., Wang, J., Martinsson, J., DeGrado, W. F., & Årsköld, S. P. (2010). Proton and cation transport activity of the M2 proton channel from influenza A virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(35), 15409–15414. [CrossRef]

- Liao, S. Y., Fritzsching, K. J., & Hong, M. (2013). Conformational analysis of the full-length M2 protein of the influenza A virus using solid-state NMR. Protein Science, 22(11), 1623–1638. [CrossRef]

- Martyna, A., Bahsoun, B., Madsen, J. J., Jackson, F. St. J. S., Badham, M. D., Voth, G. A., & Rossman, J. S. (2020). Cholesterol Alters the Orientation and Activity of the Influenza Virus M2 Amphipathic Helix in the Membrane. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 124(31), 6738–6747. [CrossRef]

- Matthys, A., & Saelens, X. (2024). Promises and challenges of single-domain antibodies to control influenza. Antiviral Research, 222, 105807. [CrossRef]

- Mezhenskaya, D., Isakova-Sivak, I., & Rudenko, L. (2019). M2e-based universal influenza vaccines: A historical overview and new approaches to development. Journal of Biomedical Science, 26(1), 76. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Phuong A., Cinque S. Soto, Alexei Polishchuk, Gregory A. Caputo, Chad D. Tatko, Chunlong Ma, Yuki Ohigashi, Lawrence H. Pinto, William F. DeGrado, and Kathleen P. Howard. (2008) pH-Induced Conformational Change of the Influenza M2 Protein C-Terminal Domain. Biochemistry 47(38), 9934–36. [CrossRef]

- Ohigashi, Y., Ma, C., Jing, X., Balannick, V., Pinto, L. H., & Lamb, R. A. (2009). An amantadine-sensitive chimeric BM2 ion channel of influenza B virus has implications for the mechanism of drug inhibition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18775–18779. [CrossRef]

- Park, E. K., Castrucci, M. R., Portner, A., & Kawaoka, Y. (1998). The M2 Ectodomain Is Important for Its Incorporation into Influenza A Virions. Journal of Virology, 72(3), 2449–2455. [CrossRef]

- Paules, C., & Subbarao, K. (2017). Influenza. The Lancet, 390(10095), 697–708. [CrossRef]

- Paulino, J., Pang, X., Hung, I., Zhou, H.-X., & Cross, T. A. (2019). Influenza A M2 Channel Clustering at High Protein/Lipid Ratios: Viral Budding Implications. Biophysical Journal, 116(6), 1075–1084. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. H., Dieckmann, G. R., Gandhi, C. S., Papworth, C. G., Braman, J., Shaughnessy, M. A., … DeGrado, W. F. (1997). A functionally defined model for the M 2 proton channel of influenza A virus suggests a mechanism for its ion selectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(21), 11301–11306. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. H., & Lamb, R. A. (2006). The M2 Proton Channels of Influenza A and B Viruses. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(14), 8997–9000. [CrossRef]

- Rossman, J. S., & Lamb, R. A. (2011). Influenza virus assembly and budding. Virology, 411(2), 229–236. [CrossRef]

- Schepens, B., De Vlieger, D., & Saelens, X. (2018). Vaccine options for influenza: Thinking small. Current Opinion in Immunology, 53, 22–29. [CrossRef]

- Shuck, K., Lamb, R. A., & Pinto, L. H. (2000). Analysis of the Pore Structure of the Influenza A Virus M 2 Ion Channel by the Substituted-Cysteine Accessibility Method. Journal of Virology, 74(17), 7755–7761. [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W K, J S Hyde, and A Kusumi. (1989) “Oxygen Permeability of Phosphatidylcholine--Cholesterol Membranes.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 86, (12) 4474–78. [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W. K., Widomska, J., & Feix, J. B. (2009). Physical properties of lipid bilayers from EPR spin labeling and their influence on chemical reactions in a membrane environment. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 46(6), 707–718. [CrossRef]

- Thomaston, J. L., Nguyen, P. A., Brown, E. C., Upshur, M. A., Wang, J., DeGrado, W. F., & Howard, K. P. (2013). Detection of drug-induced conformational change of a transmembrane protein in lipid bilayers using site-directed spin labeling. Protein Science, 22(1), 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Townsend, J. A., Sanders, H. M., Rolland, A. D., Park, C. K., Horton, N. C., Prell, J. S., … Marty, M. T. (2021). Influenza AM2 Channel Oligomerization Is Sensitive to Its Chemical Environment. Analytical Chemistry, 93(48), 16273–16281. [CrossRef]

- Yi, M., Cross, T. A., & Zhou, H.-X. (2009). Conformational heterogeneity of the M2 proton channel and a structural model for channel activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(32), 13311–13316. [CrossRef]

- Yin, H., Jiang, N., Shi, W., Chi, X., Liu, S., Chen, J.-L., & Wang, S. (2021). Development and Effects of Influenza Antiviral Drugs. Molecules, 26(4), 810. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Ding, W., Zhu, L., Zhou, Y., Dong, Y., Li, L., … Wang, J. (2023). Screening and characterization of inhibitory vNAR targeting nanodisc-assembled influenza M2 proteins. iScience, 26(1), 105736. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).