1. Introduction

Facial expressions serve as a fundamental component in enabling emotion-aware human communication and deepening our understanding of emotions. By providing essential cues, they play an important role in helping us interpret the thoughts, intentions, and emotions of others. In this context, facial Action Units (AUs) were introduced in the Facial Action Coding System (FACS) [

1] to quantify facial expressions allowing researchers to build robust and reproducible rules for emotion identification. FACS [

1] is a comprehensible taxonomy that provides an objective framework for describing and categorizing the anatomical movements of the face. This coding system comprises 32 non-overlapping fundamental actions, AUs, which correspond to specific individual muscles or groups of muscles. By the same token, FACS introduces facial AU intensity which refers to the level or strength of activation of a particular AU. This intensity is important for understanding the magnitude or power of a facial expression. By categorizing AUs into different intensity levels, ranging from slight to extreme, FACS captures even subtle nuances and variations in facial expressions which allows for a more precise analysis of emotional states. The measurement and coding of AUs intensity follow a scale from 0 to 5. A rating of 0 signifies the absence of any movement, while a rating of 5 represents the maximum intensity or full activation of the specific action unit. The intermediate intensity levels, namely 1, 2, 3, and 4, allow for a detailed representation of facial expressions by capturing varying degrees of muscle activation or movement. Quantifying human facial expressions through AUs allows to objectively learn, interpret and analyze human emotions in a manner that is both robust and reproducible.

However, the utilization of AUs in research poses challenges as they are usually annotated manually, resulting in time-consuming, repetitive, and error-prone processes. Aiming to address these issues, researchers have focused on building automated ways to detect facial AUs, and research in this direction has gained significant attention. Advancements in automated AU detection have the potential to significantly decrease the time required for this task and enhance the reliability of annotations for various downstream applications. This is closer than ever to being perfected thanks the continuous advancements in machine learning and deep learning techniques which have emerged as the predominant approaches for handling unstructured data, resulting in remarkable progress in various fields such as computer vision [

2], speech recognition [

3], and natural language processing [

4].

With that being said, a significant challenge impeding progress in medical research lies in the inherent nature of the available datasets, which often contain sensitive, confidential patient information. Healthcare institutions and hospitals, driven by a commitment to preserving patient privacy, are understandably unwilling to share such data, thereby limiting the potential for broader collaborative advancements in the field. This is even more so when the datasets include sensitive biometric information such as facial features, fingerprints, or voice patterns, that could be used to uniquely identify an individual. In particular, sharing facial images of patients could be misused if it falls in the wrong hands especially with the rapidly advancing technologies of generative artificial intelligence (AI).

As previously stated, doctors and researchers can derive a wide variety of information from patients’ facial expressions, which makes it a necessity to find a way to derive these expression without compromising patient safety or privacy by exposing or sharing identifiable facial images. Driven by this motivation, in this study, we present quick non-computationally costly method to detection Action Units (AUs) and AUs intensity, two key information for assessing one’s health and emotions, using only 3D face landmarks.

In this paper, we propose a light framework allowing extracting 3D face landmarks from video recordings and images, which can be used by researchers to strip datasets from confidential content. Nevertheless, the framework also includes a component that extract AUs from the 3D face landmarks with a high accuracy. Finally, we demonstrate the usefulness of the framework and the extracted AUs in emotion detection tasks by training Transformer [

5] and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) [

6] models on the BP4D+ [

7] dataset to detect pain, and showing competitive results to those when this task (i.e., pain detection) is performed using AUs extracted from the actual images.

The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows: (1) we propose a method for AU extraction and intensity estimation from 3D face landmarks; (2) we use of these AUs for pain detection; and (3) we demonstrate that the bare minimum number of AUs (i.e., 8 among 34 ground-truth AUs) extracted from the 3D face landmarks can be used for pain detection.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In

Section 2 we introduce some important concepts for a better understanding of the current work. In

Section 3, we describe some of the work done by the research community on the topic of AU detection and facial expression analysis, and introduce our motivation for conducting this research. In

Section 4, we describe in the detail our proposed method for AU extraction and AU intensity estimation from 3D face mesh as well as proposed method for pain detection from AUs. In

Section 5, we evaluate the performance of our proposed method and compare it to the conventional ones. Finally, in

Section 6, we conclude this paper, and open directions for future work.

2. Key Concepts

2.1. Action Units

As described in

Section 1, AUs are the fundamental components of facial expressions, used in the FACS developed by Ekman and Friesen [

1]. Each action unit corresponds to a specific movement of facial muscles, such as raising the eyebrows or pulling the lip corners. AUs are designed to objectively describe facial movements regardless of their emotional interpretation.

The utility of action units lies in their ability to decompose complex facial expressions into smaller, measurable components. This allows for the detailed analysis of human emotions, non-verbal communication, and behavioral patterns. AUs are widely used in psychological research, human-computer interaction, emotion recognition systems, and affective computing. By quantifying facial expressions through AUs, researchers can create datasets for machine learning, study the dynamics of facial expressions in social contexts, or improve algorithms for recognizing emotional states in real-time applications. Their objectivity and granularity make action units valuable for scientific research, as they enable consistent, replicable studies of facial behavior across diverse fields.

Each AU is assigned a unique identifier and can be associated with multiple emotions. For instance, AU number 9, which represents nose wrinkle, can indicate emotions such as disgust or pain. In

Table 1, we show a compilation of different emotions and their corresponding AUs [

8].

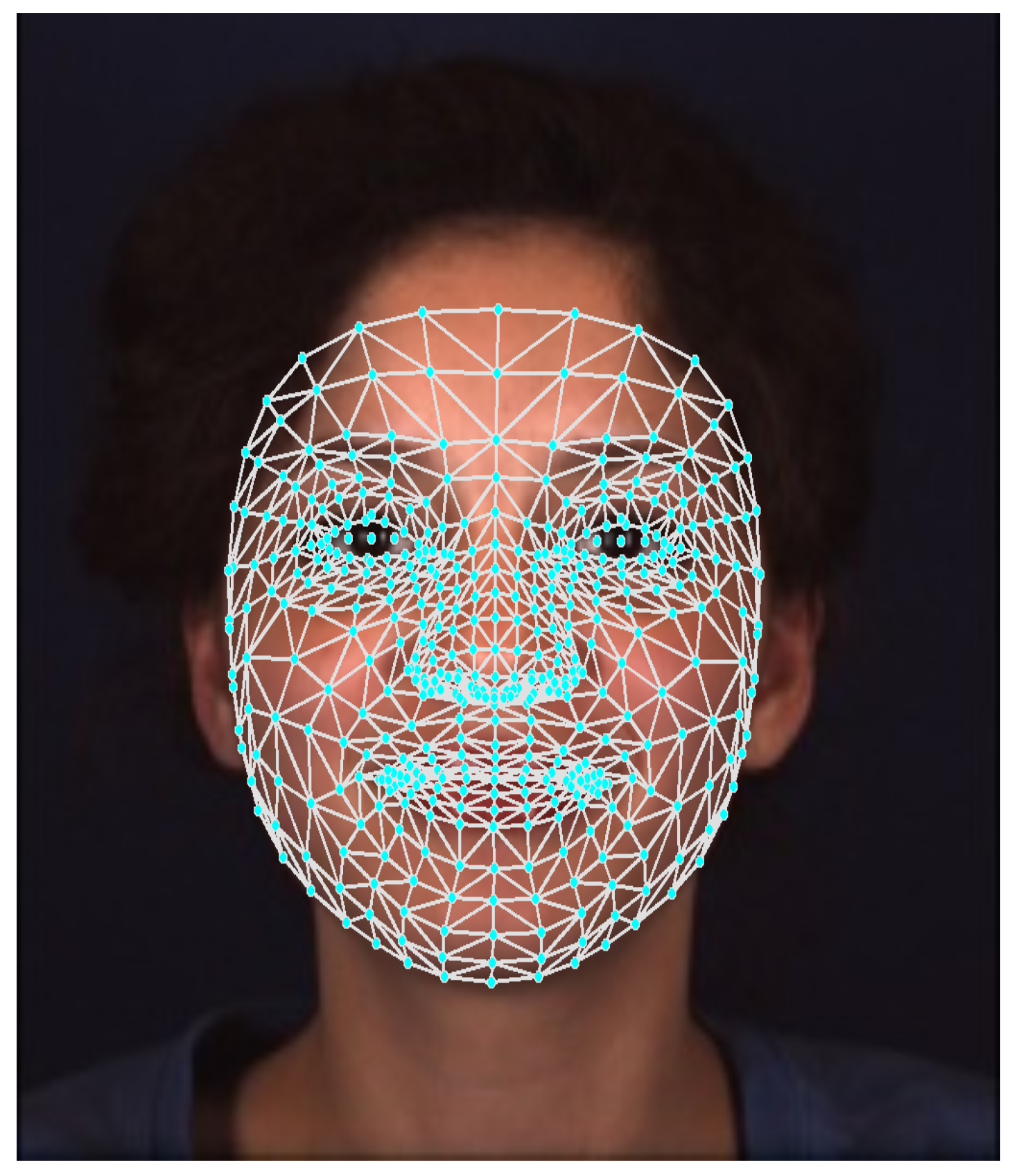

2.2. Face Mesh

The face mesh is a 3D model of the human face. This type of model is commonly used in applications involving 3D modeling or augmented reality [

9]. In our current work, we will be using a pre-trained neural network (NN) to extract the face mesh [

10]. This NN has been trained to identify the

x and

y coordinates of the different landmarks as well as to estimate the

z coordinate. The model is designed to predict the positions of 468 landmarks spread out across the facial surface, with an additional 10 landmarks allocated for the iris. Overall, the face mesh consists of 478 points, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

By converting a face image into a face mesh, we significantly reduce the size of the data by transforming image features into mesh features. This approach retains most of the critical information, allowing for effective facial expression recognition and expression analysis, as we will demonstrate later. Additionally, converting a face image into a face mesh can help safeguard the privacy of the individuals participating in any study in which their faces are visible.

2.3. Data Augmentation

Different from the two previous concept, data augmentation is a general technique used in machine learning and deep learning to artificially increase the size and diversity of a dataset by applying various transformations such as rotations, flips, or variations in brightness. The purpose of such technique is usually balancing datasets containing classes of objects with few samples compared to others. In the context of automatic AU detection, data augmentation helps address the issue of rare action units by artificially creating more samples of these underrepresented expressions. By applying the aforementioned transformations to existing data, we can generate synthetic examples of rare AUs, increasing their frequency in the training set.

2.4. Pain Detection

Pain is a complicated and subjective experience that profoundly impacts our overall well-being of humans. The development of automatic pain detection systems has the potential to improve quality of life and alleviate suffering for individuals experiencing pain. This advancement has significant implications across a variety of healthcare fields, including medical diagnosis, remote monitoring, and sport medicine.

Being a typical task related to emotion recognition, pain detection is used in this paper to highlight the effectiveness of our methods for face mesh extraction and AU detection.

3. Related Work and Motivation

3.1. Related Work

Our proposed framework is mainly related to the detection of AUs and their uses for facial expression analysis, thus we separated this subsection in two parts accordingly.

3.1.1. AUs Detection

Traditional methods for AUs detection rely heavily on manually engineered features. For example, Valstar et al. [

11] used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to recognize AUs and analyze their temporal behavior from face videos, utilizing a set of spatio-temporal features calculated from 20 facial fiducial points. Simon et al. [

12] introduced kSeg-SVM, a segment-based approach for automatic facial AU detection that combined the strengths of static and temporal modeling while addressing their limitations. By formulating AU detection as a temporal event detection problem, the method modeled feature dependencies and action unit lengths without assuming specific event structures. Experimental results showed that kSeg-SVM outperformed state-of-the-art static methods.

Jiang et al. [

13] investigated the use of local binary pattern descriptors for FACS AU detection, comparing static descriptors like Local Binary Patterns (LBP) and Local Phase Quantisation (LPQ). They introduced LPQ-TOP, a dynamic texture descriptor capturing facial expression dynamics, and demonstrated its superiority over LBP-TOP and static methods. Results showed that LPQ-based systems achieved higher accuracy, with LPQ-TOP outperforming all other methods on both posed and spontaneous expression datasets.

Chu et al. [

14] addressed the challenge of automatic facial AU detection by proposing the Selective Transfer Machine (STM), a transductive learning method to personalize generic classifiers without requiring additional labels for test subjects. STM reduced person-specific biases by re-weighting relevant training samples while learning the classifier. Evaluations on the Extended Cohn-Kanade (CK+) [

15], GEMEP-FERA [

16], and RU-FACS [

17] datasets showed that STM outperformed generic classifiers and cross-domain learning methods.

Baltrušaitis et al. in [

18] presents a real-time facial AUs intensity estimation and occurrence detection framework based on the combination of appearance features (Histogram of Oriented Gradients) and geometry features (shape parameters and landmark locations).

Zhao et al. [

19] proposed Deep Region and Multi-label Learning (DRML), a unified deep network for facial AU detection that simultaneously addresses region learning (RL) and multi-label learning (ML). The network features a novel region layer that captures facial structural information by inducing important regions through feed-forward functions. DRML’s end-to-end design integrates RL and ML for robust feature learning, achieving state-of-the-art performance on BP4D [

20] and DISFA [

21] benchmarks in terms of F1-score and AUC.

Recent advancements in deep learning have yielded impressive results in detecting AUs. Li et al. [

22] proposed a deep learning framework for AU detection that combines Region of Interest (ROI) adaptation, multi-label learning, and LSTM-based temporal fusion. Their method uses ROI cropping nets to independently learn specific face regions, integrates outputs via multi-label learning to capture AU inter-relationships, and optimally selects LSTM layers to enhance temporal feature fusion. Evaluations on BP4D [

20] and DISFA [

21] datasets demonstrated significant improvements over state-of-the-art methods, with average performance gains of 13% and 25%, respectively. In [

23], they utilized a Gated Graph Neural Network (GGNN) in a multi-scale Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) framework to integrate semantic relationships among AUs.

Shao et al. [

24] proposed an end-to-end attention and relation learning framework for facial AU detection that adaptively learns AU-specific features using only AU labels. Their method combines channel-wise and spatial attentions to extract local AU-related features and refines these features through pixel-level AU relations. The framework demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on benchmarks like BP4D [

20], DISFA [

21], and FERA 2015 [

25] for AU detection, AU intensity estimation, and robustness to occlusions and large poses.

In [

26], Zhang et al. proposed a model called Multi-Head Fused Transformer that uses both RGB and depth images to learn discriminative AUs features representations. In their work, Jacob et al. [

27] utilized image features and attention maps to feed different action unit branches, where discriminative feature embeddings were extracted using a novel loss function. Next, to capture the complex relationships between the different AUs, a Transformer encoder is employed.

3.1.2. AUs for Facial Expression Analysis

FACS has been widely used for facial expression analysis in various applications. Gupta [

28] explored facial emotion detection in both static images and real-time video using the CK and CK+ datasets [

15]. Faces were detected with OpenCV’s HAAR filters, followed by facial landmark processing and classification of eight universal emotions using SVM, achieving an accuracy of 93.7%. This approach has applications in human-robot interaction and sentiment analysis, with potential for further improvement in accuracy through landmark refinement.

Darzi et al. [

29] investigated the potential of facial action units and head dynamics as biomarkers for assessing Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) severity, depression, and Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) energy in patients undergoing DBS treatment for severe OCD. Using Automatic Facial Affect Recognition (AFAR) and clinical assessments, they analyzed data from five patients recorded during interviews across pre- and post-surgery intervals. Their model predicted 61% of OCD severity variation (YBOCS-II [

30]), 59% of depression severity (BDI), and 37% of DBS energy variation, highlighting the promise of automated facial analysis in neuromodulation therapy.

Other studies have explored the use of AUs for detecting stress [

31,

32,

33] and pain [

34]. Giannakakis et al. [

31] proposed a deep learning pipeline for automated recognition and analysis of facial AUs to differentiate between neutral and stress states. The model uses geometric and appearance facial features extracted from two publicly available annotated datasets, UNBC [

35] and BOSPHORUS [

36], and applies these to regress AU intensities and classify AUs. Tested on their stress dataset SRD’15, the method demonstrated strong performance in both AU detection and stress recognition. The study also identified specific AUs whose intensities significantly increase during stress, highlighting more expressive facial characteristics compared to neutral states.

Gupta et al. [

32] proposed using a multilayer feedforward neural network (FFNN) to distinguish between stress and neutrality based on 17 facial AUs extracted from videos using the Openface tool. The model achieved a prediction accuracy of 93.2% using the CK+ [

15] and DISFA [

21] datasets, outperforming existing feature-based approaches in distinguishing between the two emotional states.

Bevilacqua et al. [

33] proposed a method for analyzing facial cues to detect stress and boredom in players during game interactions. Their approach uses computer vision to extract 7 facial features that capture facial muscle activity, relying on Euclidean distances between facial landmarks rather than predefined expressions or model training. Evaluated in a gaming context, their method showed statistically significant differences in facial feature values during boring and stressful gameplay periods, indicating its effectiveness for real-time, unobtrusive emotion detection. This approach is user-tailored and well-suited for game environments.

Hinduja et al. [

34] trained a Random Forest (RF) model to recognize pain by combining AUs with physiological data. In [

37], Meawad et al. proposed an approach for detecting pain in sequences of spontaneous facial expressions, based on extracted landmarks from a mobile device. For comprehensive surveys on automatic pain detection from facial expressions, the readers may refer to [

38,

39].

3.2. Motivation

Given the above referred to works, the research community has been paying great attention to creating effective tools for detecting AUs which allow for a wide range of benefits in fields such as medicine, psychology, and affective computing.

What sets our proposal apart from conventional methods is the input data format and the simplicity of the neural network architecture used for AU extraction and AU intensity estimation. Unlike deep learning models that process entire images, we only used the 3D face landmarks from the face mesh. Our approach employs a straightforward fully-connected neural network to map 478 facial landmarks to top 8 AUs. Our method stands out for its efficiency in terms of computational complexity and time. (maybe we should also mention this computational efficiency aspect at the abstract and introduction session.)

Nonetheless, throughout this work, we introduce a pipeline that allows researchers to share viable datasets in low size format and without posing any threat to the privacy of participants. We demonstrate how such datasets can be used effectively for AU extraction, AU intensity estimation and emotion detection.

4. Proposed Approach

Before proceeding with our proposed approach for AU extraction, AU intensity estimation and pain detection, we will introduce the dataset on which we conducted our experiments.

4.1. Dataset

The multimodal BP4D+ dataset [

7] offers a rich and diverse collection of modalities, including 3D facial models, RGB images, thermal images, and eight physiological signals (diastolic blood pressure, mean blood pressure, electrical conductivity of the skin, systolic blood pressure, raw blood pressure, pulse rate, respiration rate, and respiration volts). The dataset consisted of 140 participants (82 females and 58 males) engaging in 10 activities aimed at eliciting 10 different emotions.

Table 2 shows the details of the activities performed. Additionally, experts in FACS annotated AUs for four distinct emotion elicitation tasks: happiness, embarrassment, fear, and pain. However, it is important to note that only the most expressive segments were subjected to annotation, resulting in an average duration of approximately 20 seconds for each segment. (the word resulting seems like there is a relationship between annotation and segment length, is the segment length changing or it depends on the annotation?) We have formulated a binary classification task for pain detection by treating pain sequences as the positive class and the remaining three emotion sequences as the negative class.

4.2. Overall System Description

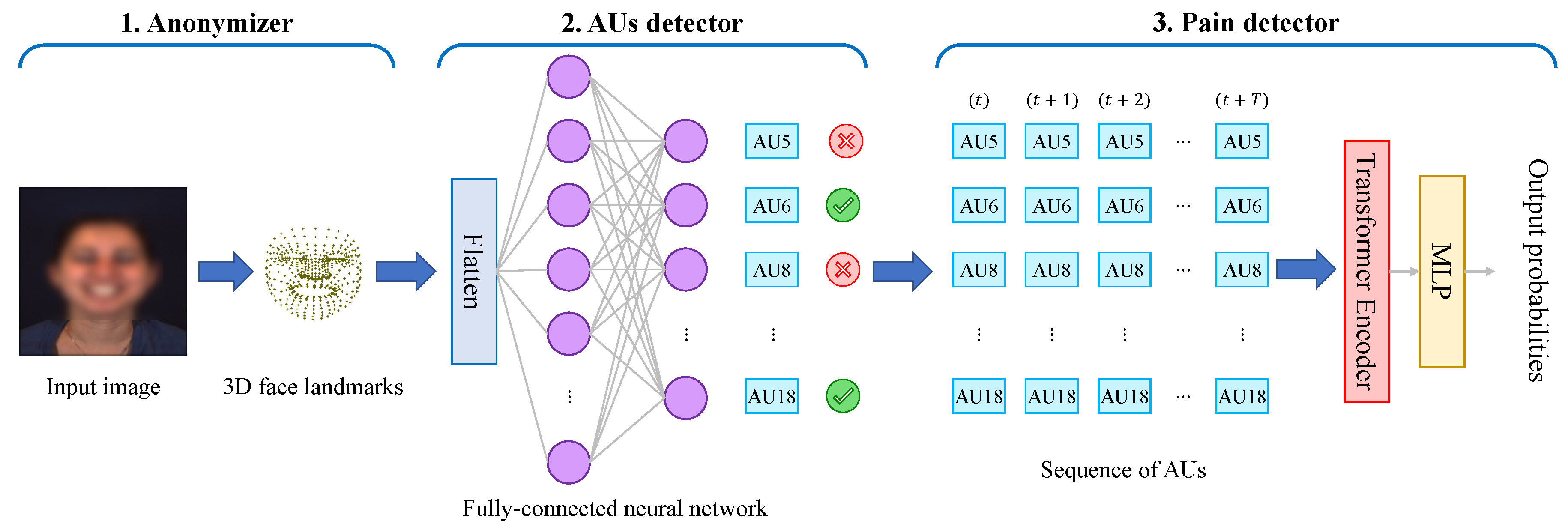

In

Figure 2, we show the flowchart of our proposed system. In addition, in

Figure 3, we show the structure of the transformer encoder block. Our system is composed of three main parts:

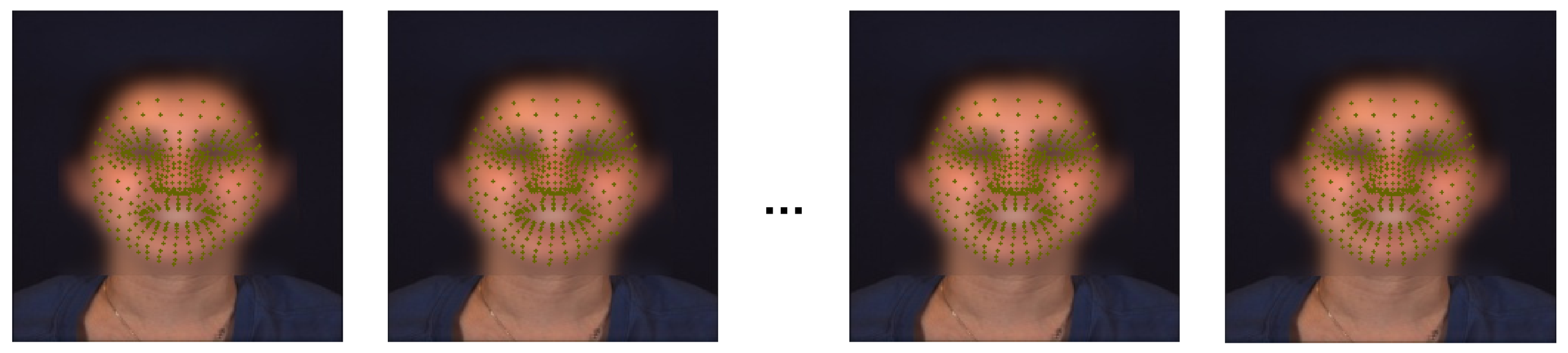

An anonymizer: this component refers to the transformation of images in our dataset into 3D face landmarks. In brief, it generates a set of 478 landmark coordinates over time. Such point coordinates are very useful in extracting information allowing for pain detection, as we will demonstrate, yet, they do not allow identifying the identity of the subjects. in

Figure 4, we show a sequence of frames which are a few seconds apart from the dataset along with their detected face landmarks. Since we employ a pre-trained model [

10] for this part, we do not describe the details of the model and its performance in this paper. Such details can be found in [

10].

An AU detector: this component simply allows extracting the main AUs from a given set of 3D face landmarks. Conventionally, NNs are trained to identify AUs from full images, making use of all embedded information. By creating NNs that extract the AUs from the 3D face landmarks, we demonstrate the usefulness of the first component, and that it is still possible to derive relevant information from a condensed and small-size vector such as the set of 3D landmarks.

A pain detector: this component relies on the detected AUs to identify the pain expressed by the subjects. Although there is still room for improvement in AU estimation accuracy, we demonstrate that effective pain detection can still be achieved, with performance comparable to that obtained using ground-truth AUs. We also demonstrate that for the pain detection task, very few AUs are required to achieve an accuracy relatively close to that when using all the AUs.

4.3. Detailed System Description

4.3.1. The AUs Detector

Conventionally, AUs are extracted from the images of human faces (similar to the input image to our anonymizer shown in the left part of

Figure 2).

However, the transformations we applied to remove identity-related information from participants also altered the original input format. As such, rather than using a typical 2D CNN for image processing, in the current work, we use a neural network that follows the structure of a typical Fully Connected (FC) neural network. In

Figure 2, we show the structure of the proposed network. The network is composed of two dense layer with 128 neurons and 8 neurons, respectively. The input layer’s shape follows the size of the input vector generated for the face landmarks,

i.e., a shape of

, with

referencing to the number of landmarks (478 in our case). The output layers composed of 8 neurons is meant to extract 8 AUs (the most common and useful ones for pain detection). It is possible to include more AUs (increase the number of neurons in the output layer). However, other AUs are quite rare in the dataset, and our experiments have shown that it is possible to reach good performance in pain detection using only 8 AUs. The results of the detection will be shown later in

Section 5.

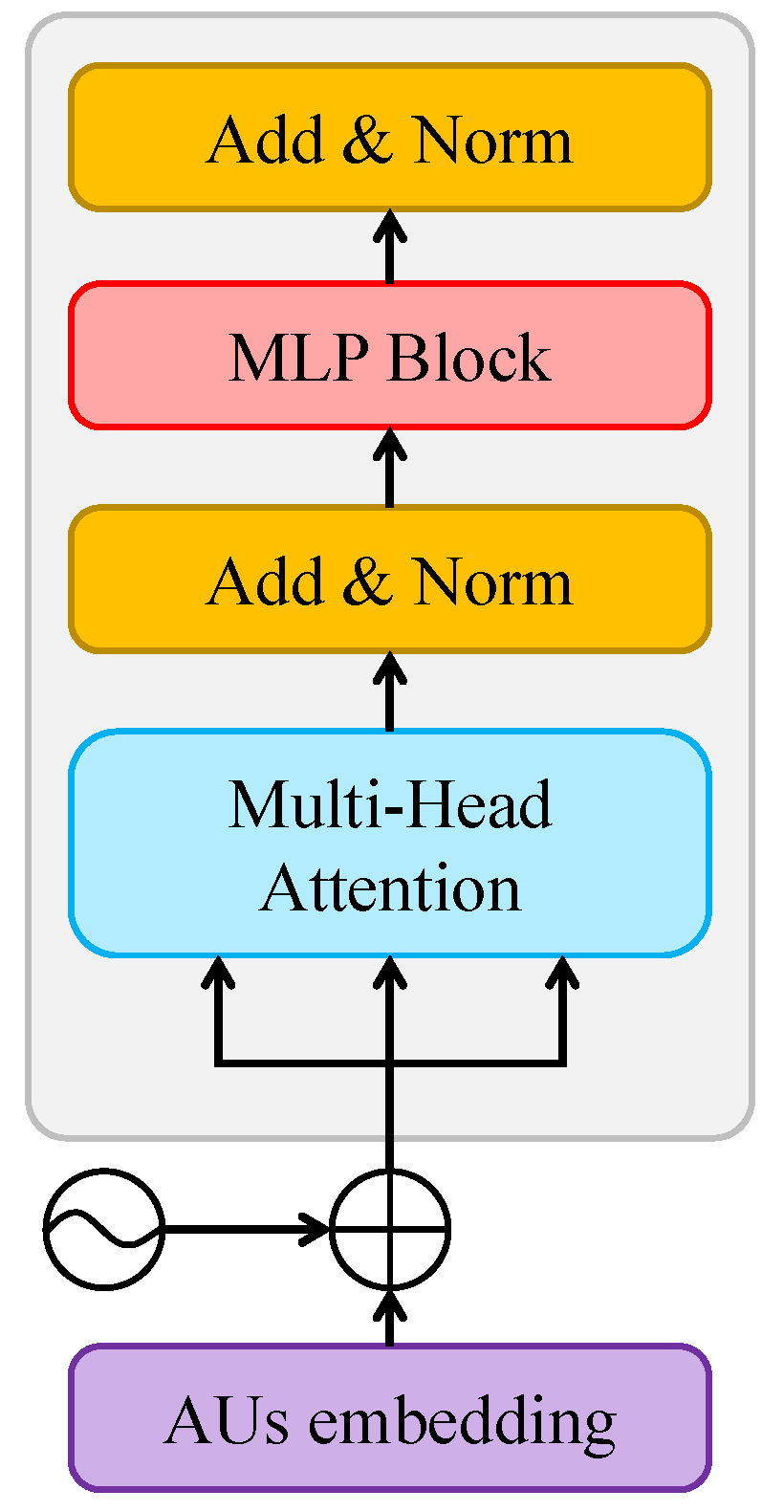

4.3.2. The Pain Detector

In this study, we propose using more advanced deep learning models to detect pain by utilizing the AUs extracted from our AU detector approach as well as all ground-truth AUs. We believe that tailored neural networks will enhance performance and enable real-time operation. Deep learning is particularly well-suited for processing sequential data and eliminates the need for feature engineering, which is often required in traditional machine learning algorithms. We employed both Transformer and LSTM and compared their performance.

LSTM is a type of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) that handles sequential data by storing and retrieving information over time. It uses a series of gates to selectively update and forget information at each time step, allowing it to capture long-term dependencies in the input sequence. On the other hand, the Transformer is a type of neural network model that has become the go-to method for handling natural language processing tasks. Unlike LSTMs, it does not use recurrent connections, but instead uses self-attention mechanisms to model the relationships between different positions in the input sequence. This allows it to capture dependencies between distant positions in the sequence, which can be difficult for LSTMs. In this work, we utilize only the encoder component of the Transformer model, as shown in

Figure 3.

The encoder processes AU embeddings, which are combined with a positional encoding and passed through a multi-head attention mechanism This is followed by two block of typical Add & Norm and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) which outputs the probabilities for two classes: pain expression and non-pain expression.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Implementation Details

5.1.1. AUs Detection

A total of 197,782 frames have been used for the training and testing. More precisely, we have used approximately 66% of the frames for training and the remaining ones for testing. (what is a frame? what is the different between a frame and the segment which was mentioned in the 4.1 dataset session.) As previously described, the FC neural network model is composed of a hidden layer with 128 neurons and a dense layer with 8 neurons for output. As for hyperparameters, we fixed the batch size to 64, the maximum number of epochs to 500, and the learning rate was set to 0.01.

To validate our AU detection approach, we employed a subject-independent 3-fold cross-validation strategy. Each fold consisted of extracted 3D face landmarks from distinct subjects, which ensured that the model was trained on one set of subjects and evaluated on another set of subjects to ensure generalizability. In terms of performance metrics, we utilized the F1-score to account for imbalanced class distribution.

5.1.2. AUs Intensity Estimation

Similar to the AUs detection, the AUs intensity estimation network is made of a hidden layer with 128 neurons and 5 neurons as output which indicate the intensity of the 5 AUs considered (i.e., AUs 6, 10, 12, 14 and 17).previously, the paper says we are using 8 AUs, why only 5 AUs here? We used the same batch size and trained the network for the same number of epochs (i.e., 64 and 500, respectively). The learning rate was also set to 0.01.

Similar to AUs detection, the AUs intensity estimation is done through a 3-fold cross-validation. The same split is done making sure that subjects used in the evaluation in each fold are different from those in the training. In terms of performance metrics, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) between the estimated intensity and the ground-truth one are used.

5.1.3. Pain Detection

During the training process, we used a fixed timestamp of 350 frames, which corresponds to approximately 14 seconds of data. To determine the optimal parameters for our models, we employed a grid-search strategy. For the Transformer model, we set the dimension of the linear projection layer to 1024, the number of multi-head attention to four, the number of encoder layers to two, and the learning rate to . Regarding the LSTM model which is composed of two layers, we fixed the hidden dimension to 512, and the learning rate to . Both models were trained with a batch size of 16 and a maximum number of epochs of 150. (Are we using the results of AU detection and AU intensity as input to this pain detection model? What is the input and how is the input processed for this LSTM and Transformer model?)

All models (for AUs and pain detection) were trained using the Adam optimizer [

40], with an exponential decay rate for the first and second-moment estimates fixed at 0.9 and 0.999, respectively. The whole pipeline was implemented using the PyTorch framework [

41]. Following prior works [

34], we utilized a subject-independent 10-fold cross-validation strategy, where each fold comprised distinct subjects whose AUs were extracted using the AUs detection model. For evaluation, we used the accuracy and F1-score. (The subject-independent n-fold cross-validation strategy is mentioned three times in this section. Seems a bit redundant, maybe we can mention it just once, for example: "All performance evaluations are conducted using a subject-independent strategy.")

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Action Units Detection

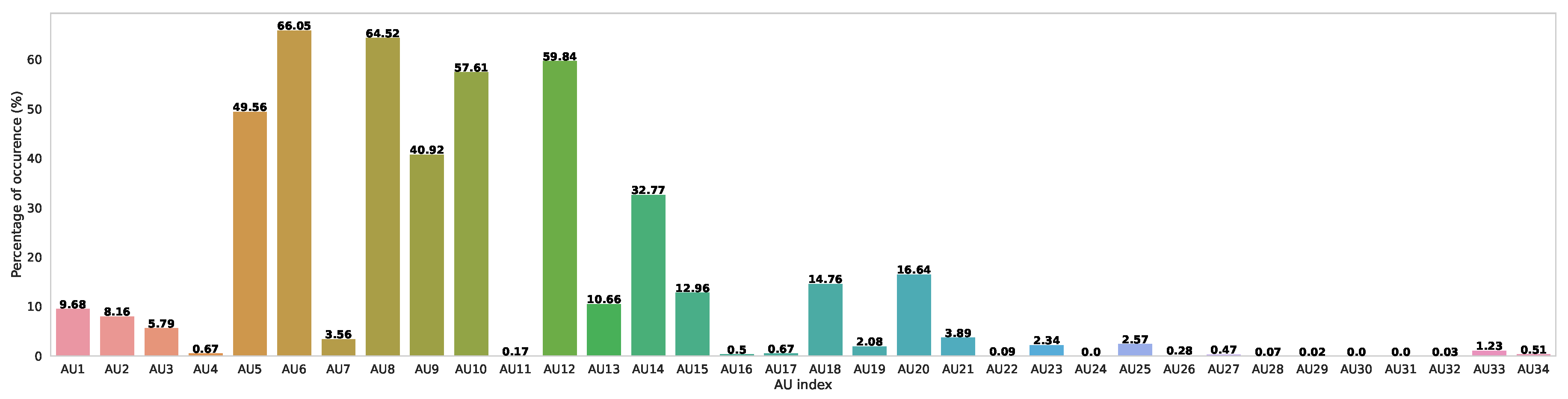

As mentioned earlier, numerous AUs poorly presented in the the vast majority of frames. In

Figure 5, we illustrate the distribution of AUs within our dataset. As can be seen, a large number of the AUs is almost totally absent in our dataset with a presence ranging from 0.0% (AUs 30 and 31) to a little over 10.66% for AU 13. Overall, the figure clearly demonstrates the imbalance in terms of AU presence in the dataset. Due to the poor presence of many AUs in the dataset, training the network to learn to detect them is unreasonable. As such, our detection results are limited to a subset of 8 AUs that are present with a relatively enough instances and contribute the most to the task we will address later, namely pain detection. In

Table 3, we list these AUs as well as their FACS name which indicates which facial muscle is moved. In addition to not having great contribution in pain detection, the infrequent AUs represent only a very small portion of the ground-truth, thus, they cannot be used to identify pertinent or generalizable patterns, as we will demonstrate later on.

Table 4 presents the average F1-score (%) for detecting the eight most frequently occurring AUs, which are also the most relevant for our study. The table shows the results of AU identification using our proposed method using 3D face mesh and that using a pre-trained CNN applied to the original images from the dataset. In the table, FCN (BP4D+) refers to applying our fully connected network to the 3D facial landmarks in the BP4D+ dataset, and FCN (Mediapipe) refers to the 3D facial landmarks extracted using Mediapipe [

10]. Unlike Mediapipe [

10], the 3D facial landmarks in BP4D+ is composed of only 83 points. Since they are annotated by experts, they are more accurate than the ones obtained using a tool like Mediapipe. However, despite that, our proposed method using Mediapipe reaches F1-scores that are superior to the one obtained when we use the 3D face landmarks from BP4D+. Maybe we should first introduce Mediapipe in related work or Key concept. To me it seems like we were introducing FCN(BP4D+) previously, and no information of FCN(Mediapipe) was provided earlier.

To enable a proper comparison with AU detection using original RGB images, we also report results obtained using a pre-trained CNN (ResNet50 [42]) applied directly to these images in their original format. Leveraging such a deep neural network represents a performance upper bound for AU detection, providing a benchmark for our method. The detection accuracy for our proposed method ranges from 55.13% for AU18 to 89.1% for AU8, with an overall average F1-score equal to 79.25%. This is not far from the detection using ResNet50 [

42] applied to images whose performance ranges from 59.99% to 89.12% with an average equal to 82.34%.

The main reason behind the poor detection accuracy of AU18 for all the methods is its low presence in the dataset. As opposed to the other 7 AUs identified here, AU18 is present in only 14.76% of the frames in our dataset. Despite AU18, our method demonstrates overall strong performance, relying on a limited number of facial landmarks compared to deep learning models that process entire images. More importantly, as we will demonstrate, the detected AUs from the human face landmarks can be used to perform classification tasks such as pain detection.

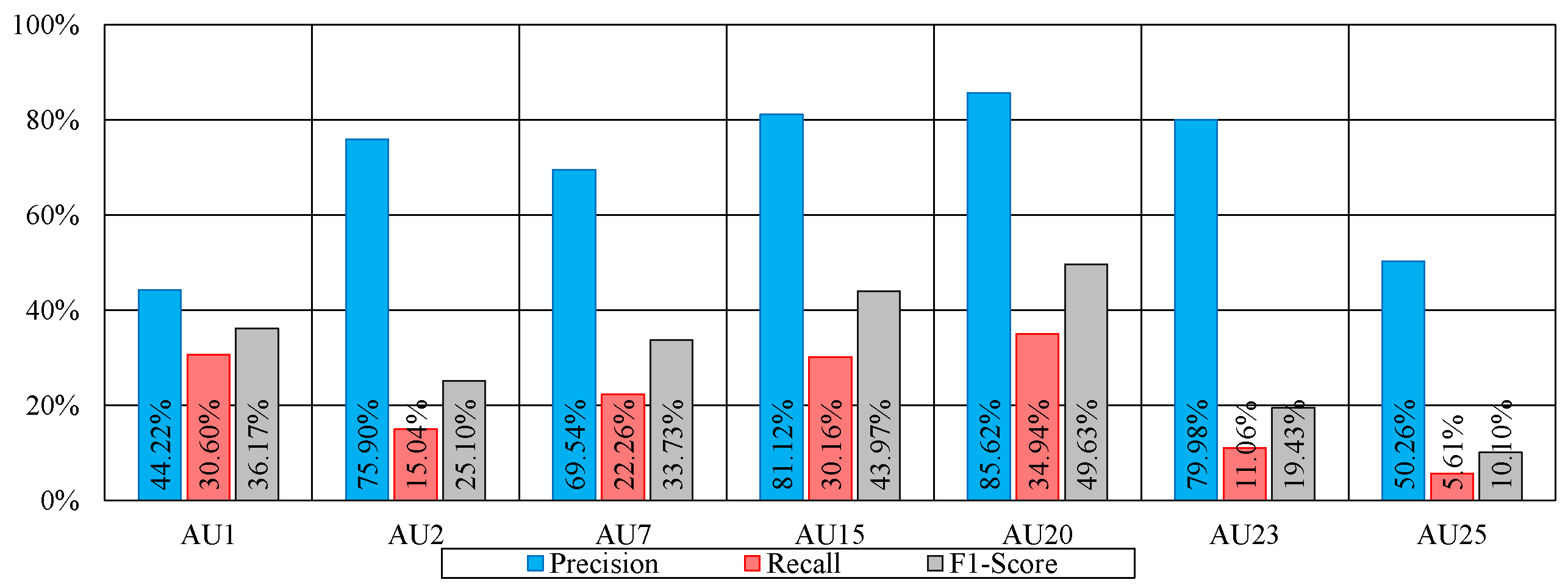

In comparison to extraction of the top 8 AUs, the remaining AUs have a much lower presence, rendering their detection quite challanging. Despite that, in our work we try to detect the next 7 more present AUs, namely AUs 1, 2 7, 15, 20, 23 and 25. To address the issue of their low presence, we need a mean to increase the number of instances in which they occur. In this context, we employ the technique we previously introduced (i.e., data augmentation) by introducing copies of the original images (from the training subset only) with several alterations including horizontal flip, rotation, cropping and linear distortion. In

Table 5, we show the detection of the aforementioned 7 AUs with and without augmentation using our proposed method. As can be observed, the overall detection of AUs is much poorer than that of the AUs that are more common in the dataset. That being said, the performance after augmentation show clear improvement. The average AU detection went from 16.31% to 31.16%, with AU20 and AU15 reporting 49.43% and 43.97%, respectively. Again, this is not very far from the results obtained using ResNet50 [

42], where the results range from 24.2% to 53.2% for AU23 and AU20, respectivly. Do we really need to detect AU’s that have less presence, seems it is not really related to Pain detection. Also the output layers have 8 neurons can it be used to detect only 7 AUs?

To further investigate the performance for each of these AUs, we show in

Figure 6 the precision and recall as well as the already reported F1-score of the method FCN (BP4D+). Since both precision and recall contribute to the F1 score, our goal is to highlight which of the two metrics contributes to the obtained results. As can be seen, for all 6 AUs, the precision is much higher than the recall. The low recall indicates that for these AUs, in many frames, they have not been detected. This is in part due to the low presence of these AUs in the training set, leading the model to learn few patterns that help detect them. In other words, the model did not encounter enough samples in the training set to understand how to detect them correctly. More interestingly is the high precision levels reported. A high precision indicates that when detected, an AUs is very likely to be indeed present. On other words, even though the model cannot always identity these AUs, but when they are detected, the model is highly likely to be correct.

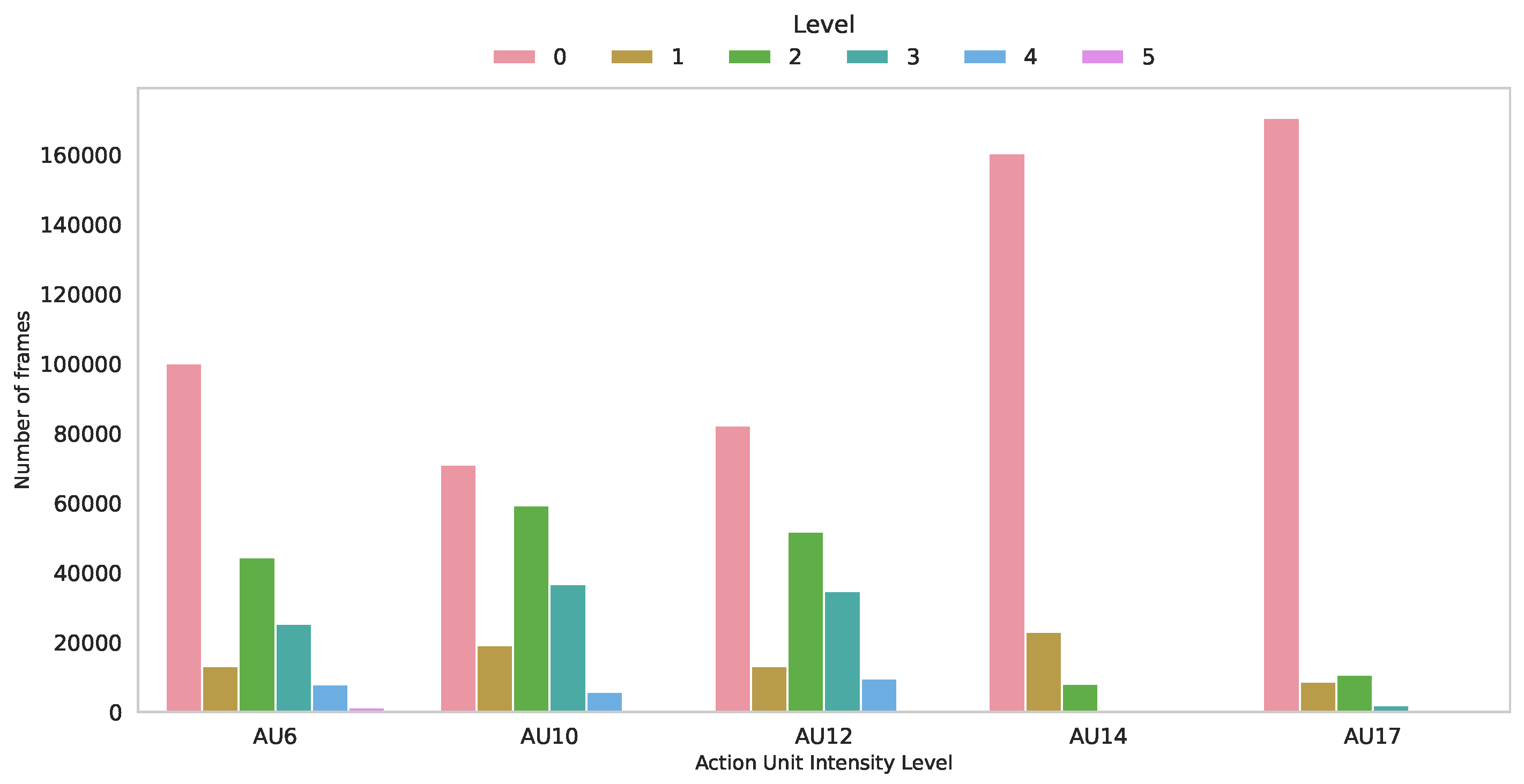

5.2.2. AUs Intensity Estimation

The AU intensity estimation is an even more challenging task than the AU detection. This is because it does not consist of a binary classification, but rather of identifying one of multiple levels. In addition, subjects with different ages have different manifestations of their facial muscle movements which renders the estimation an even harder task. Nevertheless, the presence of different intensities is even much lower than the presence of binary AUs in the dataset. In

Figure 7, we show the top 5 most present AUs with different intensities in our dataset. As can be observed, intensity 0 (which indicate absence) is predominant, with AUs such as AU14 and AU17 appearing in much fewer samples when their intensities are non-equal to 0.

That being said, in our work, we address the AU intensity estimation as a regression task, by which our neural network tries to minimize the difference between the predicted intensity and the ground-truth one. This means that, while the AU intensity should take discrete values, our models predicts a continuous value between 0 and 5. For a realistic prediction, it is possible to simply round the estimated value to its nearest integer one. As stated above, we use the same neural network we previously introduced for AU estimation with the difference is that our output layer consists of 5 neurons with a linear activation.

In

Table 6, we report the results of AU intensity estimation using our proposed method, two baseline ones including a random guess and a majority class as well as the estimation using ResNet50 [

42] fine-tuned for the estimation of individual AUs (one at a time).

As can be seen, our method outperforms the baseline ones by far, even the majority class one, reaching and RMSE equal to 0.66 and an MAE equal to 0.44. Despite the intensity 0 being dominant for all AUs in the dataset, our method outperforms the majority guess with an improvement of 0.67 and 0.41 in RMSE and MAE respectively. On the other hand, our method lags behind ResNet50 [

42] in both RMSE and MAE, with a difference of 0.08 and 0.09 in those metrics, respectively. Overall, the skewness of data in favor of the intensity 0 renders drawing a conclusion about the overall performance and its generalizability challenging. Further investigations are needed to confirm the effectiveness of both our proposed method and ResNet50 [

42] and how well they perform on other datasets.

5.2.3. Pain Detection

We present the performance of the pain detection task using four different settings, which are:

8 predicted AUs (8AUP), in which the top 8 predicted AUs (see

Table 3) are used for pain detection

8 ground-truth AUs (8AUG), in which the ground truth of the same 8AUP are used for pain detection

All ground-truth AUs (All-AUG), in which all the 34 ground truth AUs are used for pain detection

Using ResNet50 [42] + LSTM , in which the ResNet model is fine-tuned on the actual images from the dataset, and the output probabilities of each image are fed to an LSTM similar to ours.

In

Table 7, we show the performance for the task of pain detection. We report the overall accuracy and F1-score for each of the four experiments. As we can see, the results of training Transformer and LSTM models with 8AUP and 8AUG show a marginal difference. For Transformer and LSTM models, the difference in F1-score is 0.26% and 0.09% in favor of 8AUG, respectively. When comparing 8AUP with All-AUG, we can see a small difference of 2.43% and 1.13% in terms of F1-score, and 1.30% and 0.58% in terms of accuracy in favor of All-AUG for Transformer and LSTM, respectively.

In addition, 8AUP outperforms the Random Forest (RF) model proposed in [

34]. To the best of our knowledge, the work [

34] is the only one in the literature which addressed the same task as ours directly, and can be used as a baseline for a direct comparison to our work. Our approach results in a significant improvement in F1-score and accuracy, by 8.7% and 1.79% when using Transformer, and by 8.1% and 2.14% when using LSTM, compared to the Random Forest model. When using all-AUG, the F1-score and accuracy are improved by 11.13% and 2.72% when using Transformer, and by 9.23% and 2.14% when using LSTM, compared to the Random Forest model. In

Table 7 seems Transformer model have lower Accuracy but higher F1-score compared LSTM.

As stated above, we also compare our method to ResNet50+LSTM, enabling us to assess how well AUs perform relative to using full image sequences. Table 7 shows that our method is only 2.76% behind accuracy-wise and 2.01% F1-score-wise when using all ground-truth AUs. When using the predictions of or earlier model, the accuracy is 4.06% below that of ResNet50+LSTM, and the F1-score is 6.44% below.

We then explore the confusion matrix of the classification using the method 8AUP. The confusion matrix as shown in

Table 8 summarizes the classification performance for the pain detection task using this method. Overall, we can see that we have a well-balanced confusion matrix indicating that the pain detection model is performing well for both classes (pain

vs no pain), and is not biased towards one class or the other.

This balance is particularly important when working with datasets that exhibit significant class imbalances, as is common in medical datasets where images showing symptoms of a condition are often far fewer than those of healthy subjects.

5.3. Discussion

Despite showing promising results in AU detection, AU intensity estimation and using detected AUs for tasks such as pain detection, our method have much room for improvements.

As indicated by the results, detecting AUs and estimating their intensities using 3D facial landmarks is less effective as when the real-world images, which capture fine details and nuanced information from facial muscle movements. As such, in our work, we treat these images, and the realization of the different tasks using a state-of-the-art image classifier (i.e., ResNet50 [

42]) as the upper bound of what our approach could achieve.

Nonetheless, our proposed method achieves performance that is reasonably close to this upper bound. For instance, in the detection of the Top 8 AUs, our method reaches 79.25% F1-score, only 3.09% behind ResNet50. Similarly, for pain detection, our method reaches an accuracy of 92.11% and an F1-score equal to 84.53%, short of only 2.76% and 4.01% compared to ResNet50’s accuracy and F1-score. However, it is important to keep in mind that our method, not only uses a much less informative input (i.e., the coordinates of 471 key points) but also employs a much smaller neural network architecture. Our neural network consists of 128 and 8 neurons, resulting in a few thousands of parameters, as opposed to ResNet which is made of 25.6 million parameters. Needless to say, our method comprises another step, namely the anonymizer, which also consists of a deep neural network. However, this step is meant to share the data without compromising the subjects’ privacy. As such, it is meant to be done once, and all future processing is done on the resulting face meshes.

Another point that needs to be addressed is the complete dependence of the face mesh extraction on the quality of the input images. Low quality images results in inaccurate face mesh estimation. This is even more pronounced when processing sequences of images (i.e., videos) where consistency between consecutive frames is necessary. In our current work, the dataset used is quite clean and the frames extracted are of high quality. Further evaluation is needed on data from diverse sources and varying quality levels to assess the robustness of our approach.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we first proposed an approach for AUs detection using only 3D face landmarks. We achieved an overall F1-score of 79.25% for the top 8 AUs present in the multimodal BP4D+ dataset [

7], and an RMSE of AU intensity detection for the top 5 AUs. Then, to further demonstrate the effectiveness of our method, we trained a Transformer and LSTM models for the task of pain detection using solely the 8 extracted AUs from our AUs detection model. Those results are then compared to the ones obtained from ground-truth AUs. The results from the 8 predicted AUs are similar to the ones from the 8 ground truth AUs, which confirms the relevance of our AUs detection model. Nevertheless, we observe an acceptable drop in performance when compared to results from all the available AUs or when the original images are used as input for a much more sophisticated classifier (i.e., ResNet50 + LSTM). Moreover, the experimental results show that our framework, even only using the 8 predicted AUs, outperforms the existing baseline approach for the task of pain detection on the challenging BP4D+ dataset.

In a future study, we will work toward (1) improving the detection of AUs with low presence and the estimation of AUs intensity using 3D face landmarks, and; (2) on the design of a more sophisticated model for both AUs detection and AUs intensity estimation in a multi-task setting, to reach higher performance and efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MB and K.F.; methodology, M.B. and K.F.; software, M.B. and K.F.; validation, M.B., K.F. S.W., Y.Y. and T.O.; formal analysis, M.B. and K.F.; investigation, M.B., K.F. and S.W.; resources, M.B. and K.F.; data curation, M.B. and K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. and K.F.; writing—review and editing, M.B., K.F. S.W. and Y.Y; visualization, MB and K.F.; supervision, T.O.; project administration, T.O.; funding acquisition, M.B. and T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) [Grant Number: YYH3Y07] and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) ASPIRE [Grant Number: JPMJAP2326].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of a publicly avaialble dataset generously offered the authors of [

7].

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the use of a publicly avaialble dataset generously offered the authors of [

7].

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this work can be obtained by contacting the authors of the work [

7].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AFAR |

Automatic Facial Affect Recognition |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| AU |

Action Unit |

| CK+ |

Extended Cohn-Kanade |

| DBS |

Deep Brain Stimulation |

| DRML |

Deep Region and Multi-label Learning |

| FACS |

Facial Action Coding System |

| FC |

Fully Connected |

| FFNN |

Feedforward Neural Network |

| GGNN |

Gated Graph Neural Network |

| LBP |

Local Binary Patterns |

| LPQ |

Local Phase Quantisation |

| LSTM |

Long Short Term Memory |

| MAE |

Mean Absolute Error |

| ML |

Multi-Label Learning |

| MLP |

Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| NN |

neural network |

| OCD |

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder |

| RF |

Random Forest |

| RL |

Region Learning |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| ROI |

Region of Interest |

| STM |

Selective Transfer Machine |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machine |

References

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Facial action coding system. Environmental Psychology & Nonverbal Behavior 1978.

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25.

- Chiu, C.C.; Sainath, T.N.; Wu, Y.; Prabhavalkar, R.; Nguyen, P.; Chen, Z.; Kannan, A.; Weiss, R.J.; Rao, K.; Gonina, E.; et al. State-of-the-art speech recognition with sequence-to-sequence models. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2018, pp. 4774–4778.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, Minnesota, 6 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780.

- Zhang, Z.; Girard, J.M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, P.; Ciftci, U.; Canavan, S.; Reale, M.; Horowitz, A.; Yang, H.; et al. Multimodal spontaneous emotion corpus for human behavior analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 3438–3446.

- Cordaro, D.T. Universals and cultural variations in emotional expression; University of California, Berkeley, 2014.

- Kitanovski, V.; Izquierdo, E. 3d tracking of facial features for augmented reality applications. In Proceedings of the WIAMIS 2011: 12th International Workshop on Image Analysis for Multimedia Interactive Services, Delft, The Netherlands, April 13-15, 2011. TU Delft; EWI; MM; PRB, 2011.

- Kartynnik, Y.; Ablavatski, A.; Grishchenko, I.; Grundmann, M. Real-time facial surface geometry from monocular video on mobile GPUs. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.06724 2019.

- Valstar, M.; Pantic, M. Fully automatic facial action unit detection and temporal analysis. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshop (CVPRW’06). IEEE, 2006, pp. 149–149.

- Simon, T.; Nguyen, M.H.; De La Torre, F.; Cohn, J.F. Action unit detection with segment-based SVMs. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. IEEE, 2010, pp. 2737–2744.

- Jiang, B.; Valstar, M.F.; Pantic, M. Action unit detection using sparse appearance descriptors in space-time video volumes. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2011, pp. 314–321.

- Chu, W.S.; De la Torre, F.; Cohn, J.F. Selective transfer machine for personalized facial action unit detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2013, pp. 3515–3522.

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Kanade, T.; Saragih, J.; Ambadar, Z.; Matthews, I. The extended cohn-kanade dataset (ck+): A complete dataset for action unit and emotion-specified expression. In Proceedings of the 2010 ieee computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition-workshops. IEEE, 2010, pp. 94–101.

- Valstar, M.F.; Mehu, M.; Jiang, B.; Pantic, M.; Scherer, K. Meta-analysis of the first facial expression recognition challenge. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics) 2012, 42, 966–979. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S.; Littlewort, G.; Frank, M.G.; Lainscsek, C.; Fasel, I.R.; Movellan, J.R.; et al. Automatic recognition of facial actions in spontaneous expressions. J. Multim. 2006, 1, 22–35. [CrossRef]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Mahmoud, M.; Robinson, P. Cross-dataset learning and person-specific normalisation for automatic action unit detection. In Proceedings of the 2015 11th IEEE International Conference and Workshops on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2015, Vol. 6, pp. 1–6.

- Zhao, K.; Chu, W.S.; Zhang, H. Deep region and multi-label learning for facial action unit detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 3391–3399.

- Zhang, X.; Yin, L.; Cohn, J.F.; Canavan, S.; Reale, M.; Horowitz, A.; Liu, P. A high-resolution spontaneous 3d dynamic facial expression database. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th IEEE international conference and workshops on automatic face and gesture recognition (FG). IEEE, 2013, pp. 1–6.

- Mavadati, S.M.; Mahoor, M.H.; Bartlett, K.; Trinh, P.; Cohn, J.F. Disfa: A spontaneous facial action intensity database. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing 2013, 4, 151–160. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Abtahi, F.; Zhu, Z. Action unit detection with region adaptation, multi-labeling learning and optimal temporal fusing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 1841–1850.

- Li, G.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lin, L. Semantic relationships guided representation learning for facial action unit recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 8594–8601. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cai, J.; Wu, Y.; Ma, L. Facial action unit detection using attention and relation learning. IEEE transactions on affective computing 2019, 13, 1274–1289. [CrossRef]

- Valstar, M.F.; Almaev, T.; Girard, J.M.; McKeown, G.; Mehu, M.; Yin, L.; Pantic, M.; Cohn, J.F. Fera 2015-second facial expression recognition and analysis challenge. In Proceedings of the 2015 11th IEEE International Conference and Workshops on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2015, Vol. 6, pp. 1–8.

- Zhang, X.; Yin, L. Multi-Modal Learning for AU Detection Based on Multi-Head Fused Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–8.

- Jacob, G.M.; Stenger, B. Facial action unit detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 7680–7689.

- Gupta, S. Facial emotion recognition in real-time and static images. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd international conference on inventive systems and control (ICISC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 553–560.

- Darzi, A.; Provenza, N.R.; Jeni, L.A.; Borton, D.A.; Sheth, S.A.; Goodman, W.K.; Cohn, J.F. Facial Action Units and Head Dynamics in Longitudinal Interviews Reveal OCD and Depression severity and DBS Energy. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Storch, E.A.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Price, L.H.; Larson, M.J.; Murphy, T.K.; Goodman, W.K. Development and psychometric evaluation of the yale–brown obsessive-compulsive scale—second edition. Psychological assessment 2010, 22, 223. [CrossRef]

- Giannakakis, G.; Koujan, M.R.; Roussos, A.; Marias, K. Automatic stress analysis from facial videos based on deep facial action units recognition. Pattern Analysis and Applications 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Gupta, P.; Maji, S.; Jain, V.K.; Agarwal, S. Automatic Stress Recognition Using FACS from Prominent Facial Regions. In Proceedings of the 2024 First International Conference on Pioneering Developments in Computer Science & Digital Technologies (IC2SDT). IEEE, 2024, pp. 488–492.

- Bevilacqua, F.; Engström, H.; Backlund, P. Automated analysis of facial cues from videos as a potential method for differentiating stress and boredom of players in games. International Journal of Computer Games Technology 2018, 2018, 8734540. [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Canavan, S.; Kaur, G. Multimodal fusion of physiological signals and facial action units for pain recognition. In Proceedings of the 2020 15th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2020). IEEE, 2020, pp. 577–581.

- Lucey, P.; Cohn, J.F.; Prkachin, K.M.; Solomon, P.E.; Matthews, I. Painful data: The UNBC-McMaster shoulder pain expression archive database. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition (FG). IEEE, 2011, pp. 57–64.

- Savran, A.; Alyüz, N.; Dibeklioğlu, H. Bosphorus Database for 3D Face Analysis In: European workshop on Biometrics & Identity Management, 2008.

- Meawad, F.; Yang, S.Y.; Loy, F.L. Automatic detection of pain from spontaneous facial expressions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, 2017, pp. 397–401.

- Chen, Z.; Ansari, R.; Wilkie, D. Automated pain detection from facial expressions using facs: A review. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.07988 2018.

- Hassan, T.; Seuß, D.; Wollenberg, J.; Weitz, K.; Kunz, M.; Lautenbacher, S.; Garbas, J.U.; Schmid, U. Automatic detection of pain from facial expressions: a survey. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence 2019, 43, 1815–1831.

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014.

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).