1. Introduction

The growing need for sustainable materials has led to an increased adoption of 3D printing techniques across various applications. These techniques offer valuable advantages, such as the ability to create complex designs, faster production on-site, high resolution, and significantly reduced waste. Additionally, they promote recyclability, making them more cost-effective compared to traditional polymer processing methods like moulding and extrusion. This shift has had a significant economic and social impact [

1,

2]. Furthermore, 4DP SMPs are recognized as a unique category of smart, sustainable materials. Significant knowledge is required to understand the temporary shape (shape fixity, also called shape programming) and its shape-changing region to enhance the utilisation of 3DPd structures [

3,

4,

5]. Approaches based on temperature-responsiveness as a thermal trigger for the SMPs have been extensively studied. SMPs can change their shape with the effect of thermal stimulus that, after being shaped into a "temporary, also known as programming" configuration, can be returned into a "permanent" shape through a thermo-mechanical process. These smart polymers can return to their permanent shape when heated above the glass transition temperature [

6,

7,

8]. Various mechanisms may be utilised to obtain deployment responses like temperature-responsive (Thermal stimuli) SMPs. Most SMP materials have two stages: permanent shape recovery after a temporary shape through a thermomechanical procedure (programming) [

6,

9]. In addition, functionally graded SMP materials have attracted researchers', manufacturers’ and supply chains' attention as durable materials whose structure has the capability to switch to multiple shapes, thus enabling the optimisation of the characteristics for required applications [

10,

11].

The efficiency of such materials in performing their function is the capability to withstand different loading conditions during their lifetime. One of these loading cases is the propagation of an existing crack. The fracture toughness of a material containing a crack is represented by the critical stress intensity factor (K

IC). It is the critical value of stress intensity at a crack tip essential for understanding the conditions that lead to catastrophic failure under simple uniaxial loading [

12,

13]. Mixed-mode fracture, which includes both mixed-mode I/II and mixed-mode I/III scenarios, is the most common type of fracture associated with cracked components. Research has focused on crack tilting, which involves opening and sliding for mixed-mode I/II [

14,

15,

16] and crack twisting, characterized by opening and tearing for mixed-mode I/III [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, compared to the testing available for mixed-mode I/II, there are fewer qualified loading configurations for mixed-mode I/III testing. Pan et al. [

17] investigated the fracture parameters to show that the pristine mode I fracture, and mixed-mode (I/II, I/III and I/II/III) fractures can be realised by varying the direction of the crack angles. Also, the study showed that the critical stress intensity factor decreased when the angle between the crack and loading direction changed from mode I (crack angle parallel to the load) to mixed mode I/III. Avci et al. [

21] found that the mixed-mode I/III fracture toughness behaviour of polyester resin filled with sand particles and chopped glass fibre was significantly affected by varying crack angles under the SENB test.

Polymeric materials can be sensitive to long-term exposure to moisture and heat. For example, the mechanical and thermal behaviour of polymer materials can be significantly affected by moisture absorption, particularly at high temperatures. This means that water can progressively penetrate the polymer matrix [

22,

23]. Despite some thermoplastic materials like PA6 could promote crystallisation with moisture diffusing during hydrothermal treatment into the amorphous region due to the reorganisation of the hydrogen bond among amide groups in the amorphous region [

24]. In contrast, exposure of thermosets like epoxy to moisture and heat for long periods may lead to damage to their structural integrity due to the degradation of chain crosslinking and chain scission. This environment can deteriorate the matrix of thermoset-based materials by affecting their chemical compound. Polymer chain crosslinking can make the polymer brittle, potentially resulting in microcracks on the material's surface. Meanwhile, chain scission can reduce the molecular weight and weaken the thermal and mechanical properties of the polymer matrix [

23,

25,

26].

According to the literature survey, several researchers have investigated the effects of hydrothermal ageing on the shape memory properties of the 3DPd structures. To the best of the author's knowledge, no study has been found to report the effect of humidity and temperature on the mixed mode fracture toughness and shape memory properties of the 3DPd UV-curable resin. In this study, a DLP resin was employed for 3DPg epoxy-based components. The viscoelastic, shape memory, and fracture characteristics of the epoxy-based UV-curable resin under the effects of short and long hydrothermal accelerating ageing were investigated. The chemical behaviour was analysed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The curing behaviour was explored by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The viscoelastic properties and shape memory (SMP) behaviour were via DMTA. This investigation study can increase the 4DPg technology of thermosets-based 3DPd structures in various engineering applications.

2. Materials and Methods

Rigid 140C Black resin (Referred as 3DP-Ep) (3D Systems, Inc., Rock Hill, South Carolina, USA) was employed as a photopolymer resin (UV light-activated resin). This resin consists of some chemical materials (

Table 1). 3DP-Ep (A two-part epoxy/acrylate hybrid material) is a heat-resistant material combining high elongation and high strength for direct plastics production, tool-less, which can be used for various applications like under-the-hood and internal cabin automotive covers, clips, connectors, fasteners and housings, board connectors, and electrical latching [

27].

The resin in part A bottle was shaken and mixed for 1 hour for first-time use on the 3D Systems LC-3D mixer, which was also mixed for 10 minutes before subsequent use. A 19:1 mix ratio of part A to part B was shaken vigorously in a mixing container for 5 min. The resulting 3DP-Ep blend resin was stirred in the printer's tray for 30 seconds between every printing process.

Figure 4® 3D printer (3D Systems) was utilised to manufacture the 3DP-Ep samples with a UV light wavelength of 405 nm and a layer thickness set to 0.1 mm. The support structure of the printed samples was oriented at 90° with the platform to provide a minimum structure with good resolution and surface finish. The 3DPd objects were washed with isopropyl alcohol (IPA) for 2 min and then, after drying, UV-post-cured for 90 as suggested by the manufacturer. A three-hour thermal post-cure at 135 °C was also used for the full-curing process, as preferred by the manufacturer. A Memmert water path machine was used to immerse 3DPd samples in distilled water coupled with 45

oC for (0, 60 and 120) days as hydrothermal accelerated ageing.

2.1. FTIR, DSC, Viscoelastic and Water Uptake Test Procedure

The FTIR test was conducted using a Perkin Elmer ATR-FTIR machine (Norwalk, CT, USA) with a scanning range of 1000 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1 wavenumber and resolution of 4 cm−1. The DSC analysis was performed with a Perkin Elmer machine DSC 4000 (Norwalk, CT, USA). For the DSC measurements, 7 mg samples were heated from -10 to 230 oC at a rate of 5 oC/min, followed by cooling back to -10 oC at the same rate. DMTA was conducted using a TA Instruments machine Q800 (New Castle, DE, USA). In this test, a single cantilever mode was utilized with an oscillation frequency of 1 Hz and a strain of 0.02%. The temperature was increased from 25 °C to 210 °C at a heating rate of 3 °C/min. The free length, width, and thickness of the specimen were 12 mm × 17.5 mm × 3.2 mm, respectively. Tg was determined from the tan(δ) and loss modulus peaks.

The water uptake was calculated from the change in the weight of the 3DPd specimens (C) as follows:

Where W

t is the weight of the specimen after a specific immersion time of up to 408 h (17 days), and W

o is the weight of the sample before ageing. The specimens were weighed before and after a fixed interval of the hydrothermal ageing. The average values were obtained from four rectangular specimens.

2.2. SMP Test Procedure

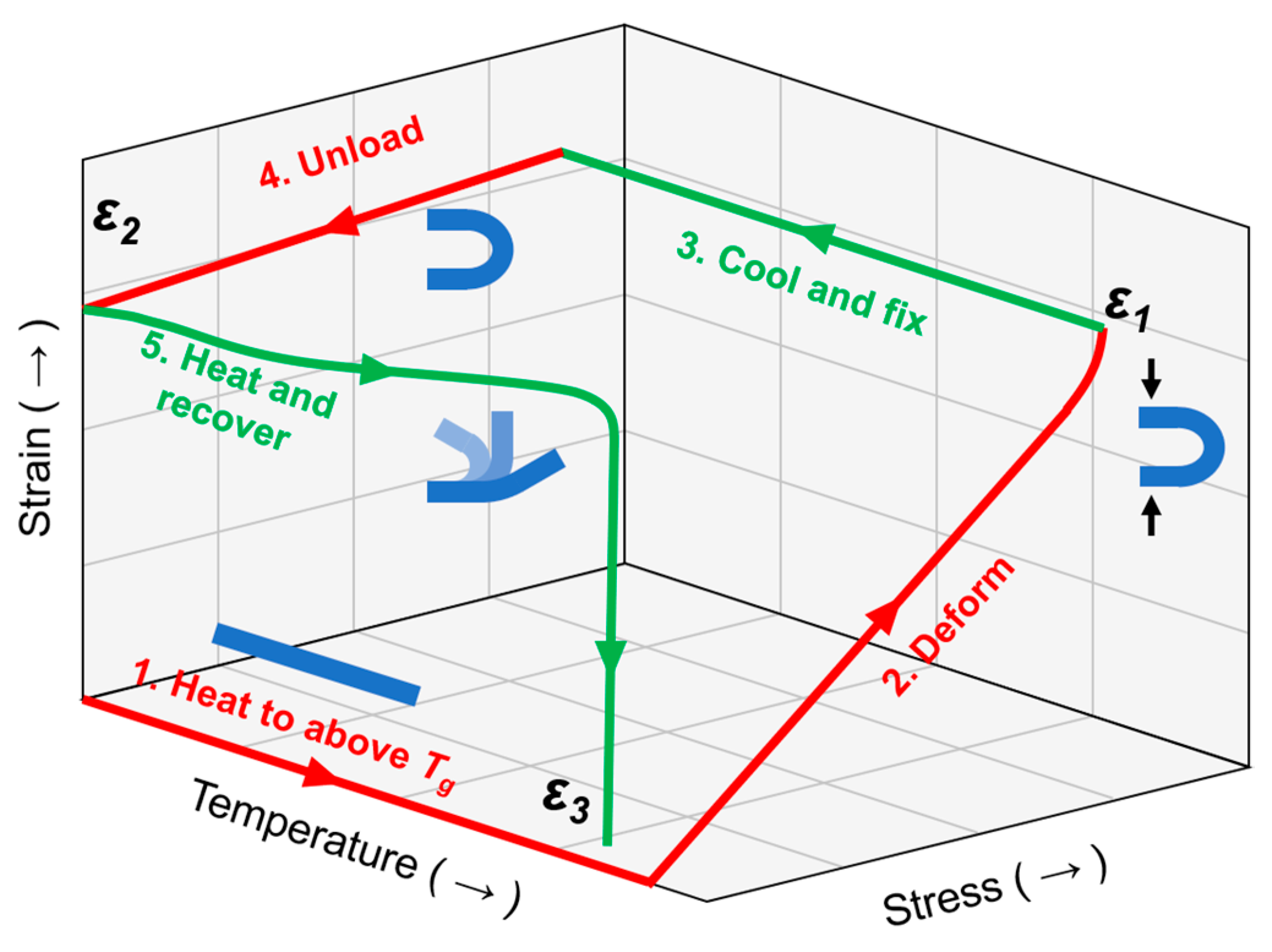

Two procedures were used to understand the SMP behaviour of the 3DPd epoxy-based objects. The first SMP procedure was the thermomechanical SMP cycle test (

Figure 1), which was used to investigate the shape fixity and shape recovery using DMTA single cantilever mode. This technique is usually used to analyse the fixity/recovery behaviour of SMPs [

28,

29].

Tg was considered a reference temperature when designing the thermomechanical procedure. This procedure is performed as follows: (1) Heating the sample above

Tg with a rate of 5 °C min

−1 then isothermal for 25 min; (2) Deforming the sample with a ramped force at a rate of 0.5 N min

−1 ; (3) Cooling down the sample to 25 °C withholding the force constant; (4) Releasing the force; (5) Heating back the sample above

Tg. Then, repeat the process from step (2).

The shape recovery (

) and shape fixity (

) values were determined by the following equations:

Where ε

1 is the strain induced by an external load above

Tg.

ε2 is the strain after releasing the external load at room temperature.

ε3 is the strain when heating above

Tg again.

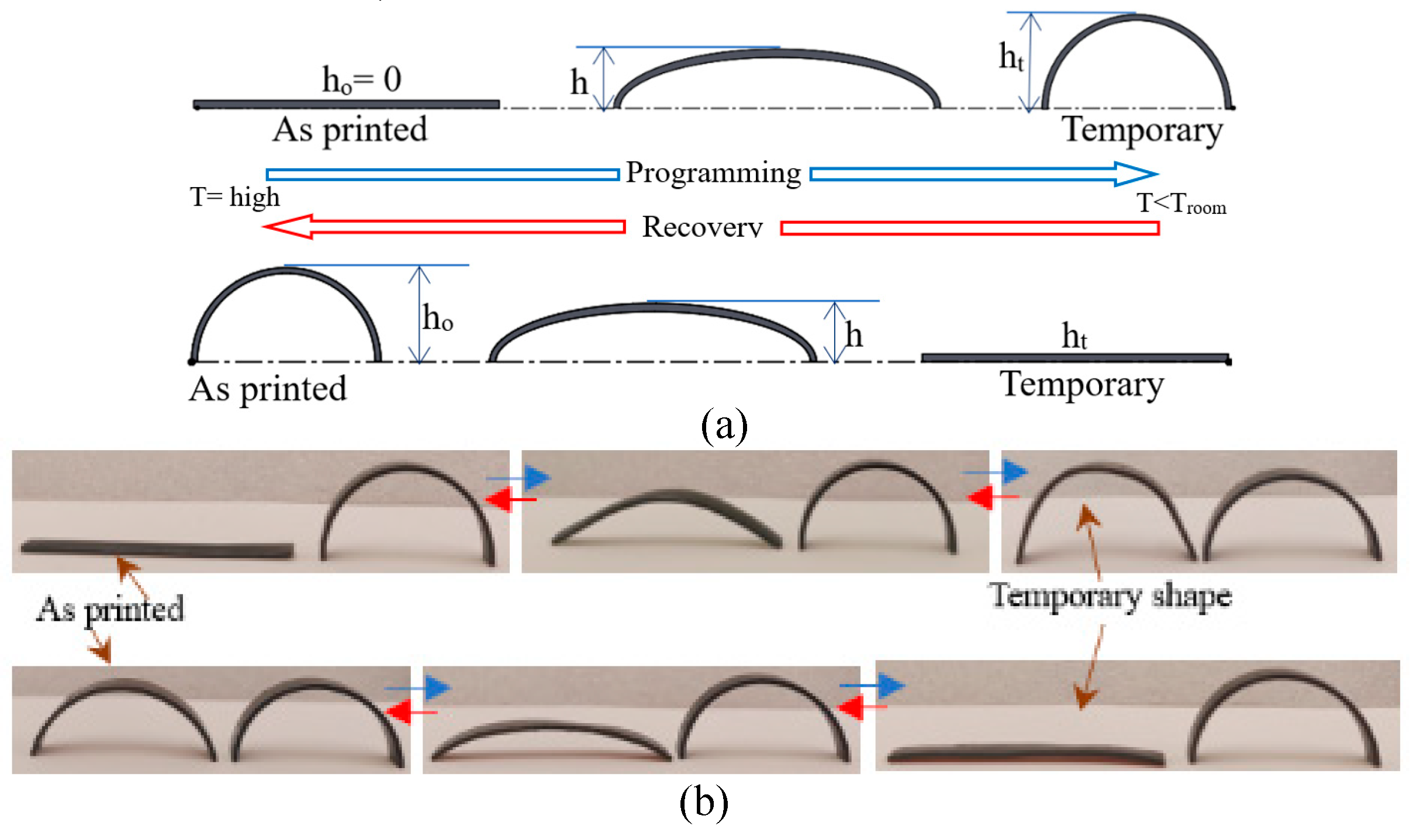

The second SMP procedure was conducted to explore the sequential deployment of the flat and circular 3DPd samples [

30].

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b represent a schematic diagram and photographs for the programming and recovery process of the 3DPd samples. The size of the 3DPd flat sample was 50 × 7 × 1 mm

3, and it was the same dimension as the circular sample when it was programmed under the shape fixity process. The SM performance for the flat and circular samples included two processes: programming shape (Temporary) occurred during the fixity shape due to heating the sample in sunflower oil, with a temperature around

Tg (160 °C), then it cooled down to the room temperature (20 °C). The flat and circular samples were put in a silicon mould, and a flat metal plate was put on the sample to maintain their programming shape. The second process, i.e., the recovery shape (Permanent), was achieved by heating the sample again in a sunflower oil from 0 °C to 160 °C. The test was repeated 5 times. A high-resolution camera was positioned in front of the sample to capture the recovery process. A thermometer was used to monitor the temperature near the sample inside a glass beaker. The height (h) (see

Figure 2a) was measured using digital imaging analysis software (ImageJ, version 1.54d).

This procedure was utilized to calculate the shape fixity (

) and shape recovery (

) values using the following equations:

where h

t is the temporary height,

ho is the as-printed height, h

u is the height after load release, and

h is the actual height, as shown in

Figure 2a.

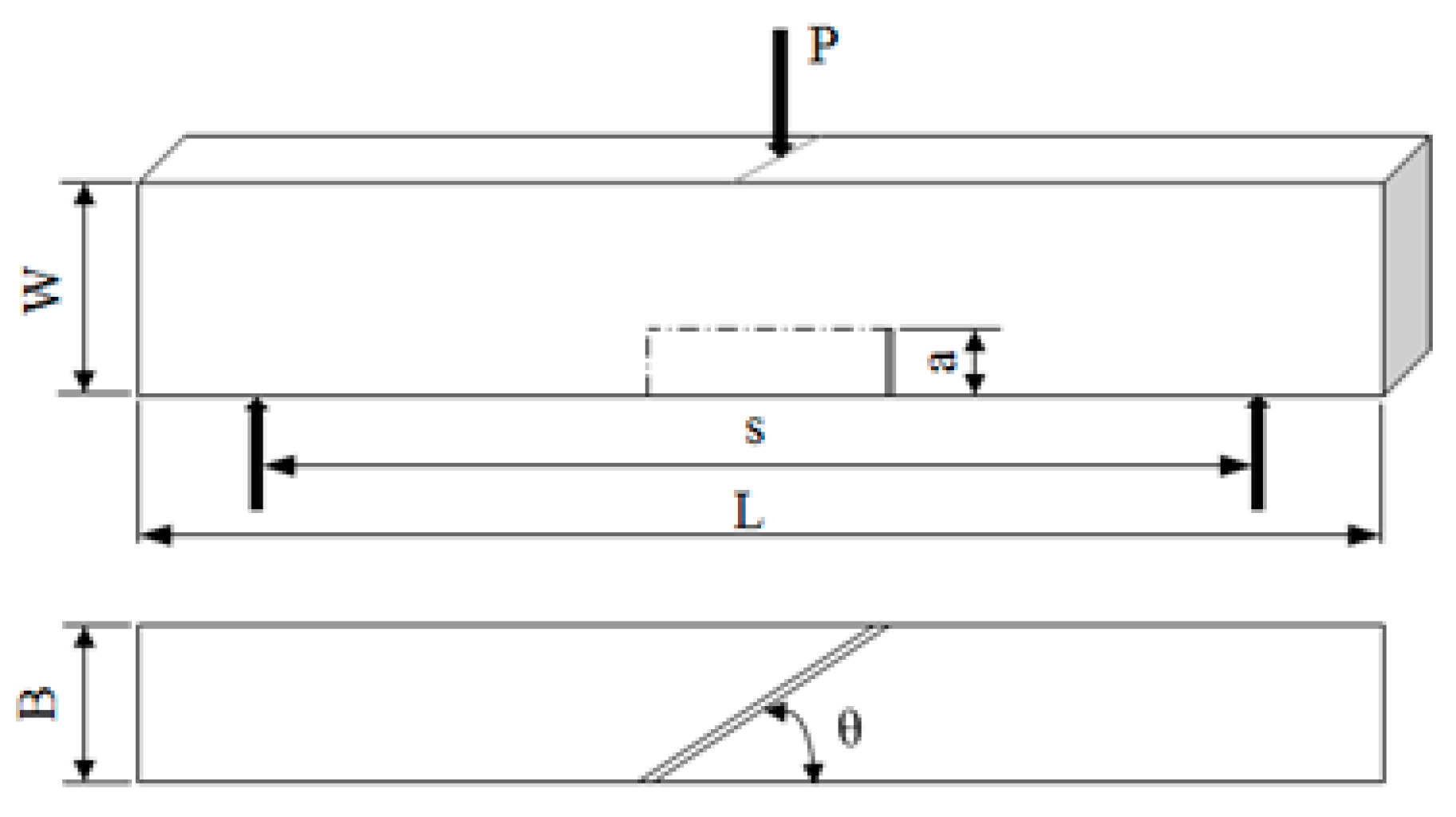

2.3. Mixed Mode I/III Fracture Test Procedure

The stress intensity factor values of the SENB specimens resulting from conducting TPB of LEFM were determined by several studies in the literature [

9,

21,

31].

Figure 3 represents a schematic diagram of the geometrical configuration of the SENB specimen. The mode I critical stress intensity factor can be determined via the initial notch depth technique by the below equations:

Where

P is the fracture load for crack propagation,

B is the sample width, and

s is the span length.

is the correction parameter.

For an inclined notch of the SENB test, several researchers determined the critical stress intensity factor for mixed-mode I/III [

13,

21] specified that the apparent stress intensity factor (

KA) can be used to calculate the critical stress intensity factors for mode I (

KIc) and mode III (

KIIIc) by substitution

KA into equations (8) and (9) below:

The

KIc and

KIIIc were calculated from equations (6), (8) and (9), as:

3. Results

3.1. FTIR and Water Uptake Behaviour

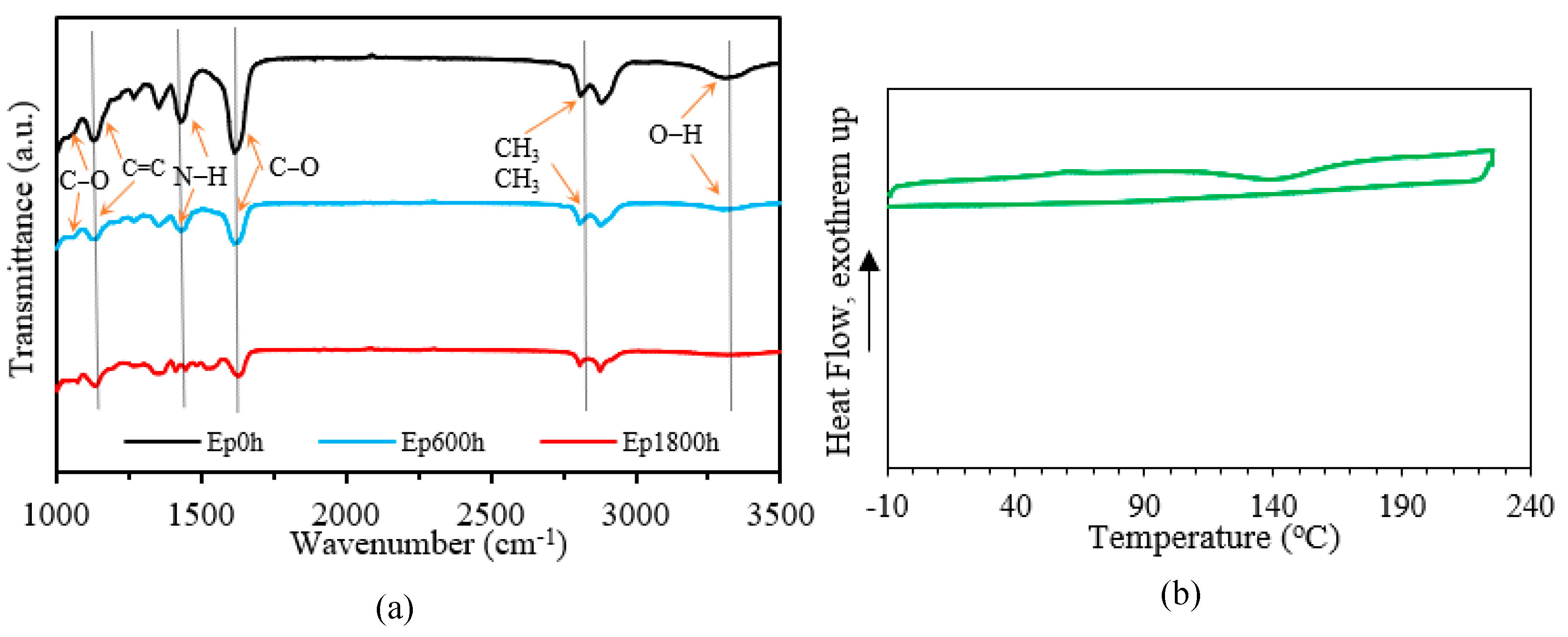

FTIR experiments were conducted to investigate the chemical bond alterations and assess the degradation of the epoxy-based network of the 3DPd composites under hydrothermal accelerating ageing.

Figure 4 illustrates the FTIR spectra of the 3DP-Ep samples before and after the immersion in distilled water for 600 h and 1800 h. The intensity of all peaks became almost lower with long-term immersion. For instance, the ester bonds represented by C–O stretching were located at around 1150 cm

−1 and 1700 cm

−1. The same behaviour was noticed for the C=C peak at 1200 cm

-1, and the symmetric stretching of CH

2 and CH

3 at the peaks between 2850 cm

−1 and 2950 cm

−1, respectively [

32].

The DSC measurement is a reliable tool for measuring and visualising the endotherm reaction of epoxy thermosets.

Figure 4b shows the DSC heating and cooling curves for the 3DPd epoxy-based sample before thermal post-curing. The DSC curve shows the amorphous nature and crosslinking behaviour of the 3DPd samples. The heat flow of the 3DPd sample shows an endotherm peak in the curve at approximately 140 °C, which refers to the glass transition temperature.

Figure 4.

(a) FTIR spectra of the 3DP-Ep before hydrothermal ageing and after immersion in distilled water for 450 h and 1200 h, (b) the DSC analysis before and after thermal post-curing.

Figure 4.

(a) FTIR spectra of the 3DP-Ep before hydrothermal ageing and after immersion in distilled water for 450 h and 1200 h, (b) the DSC analysis before and after thermal post-curing.

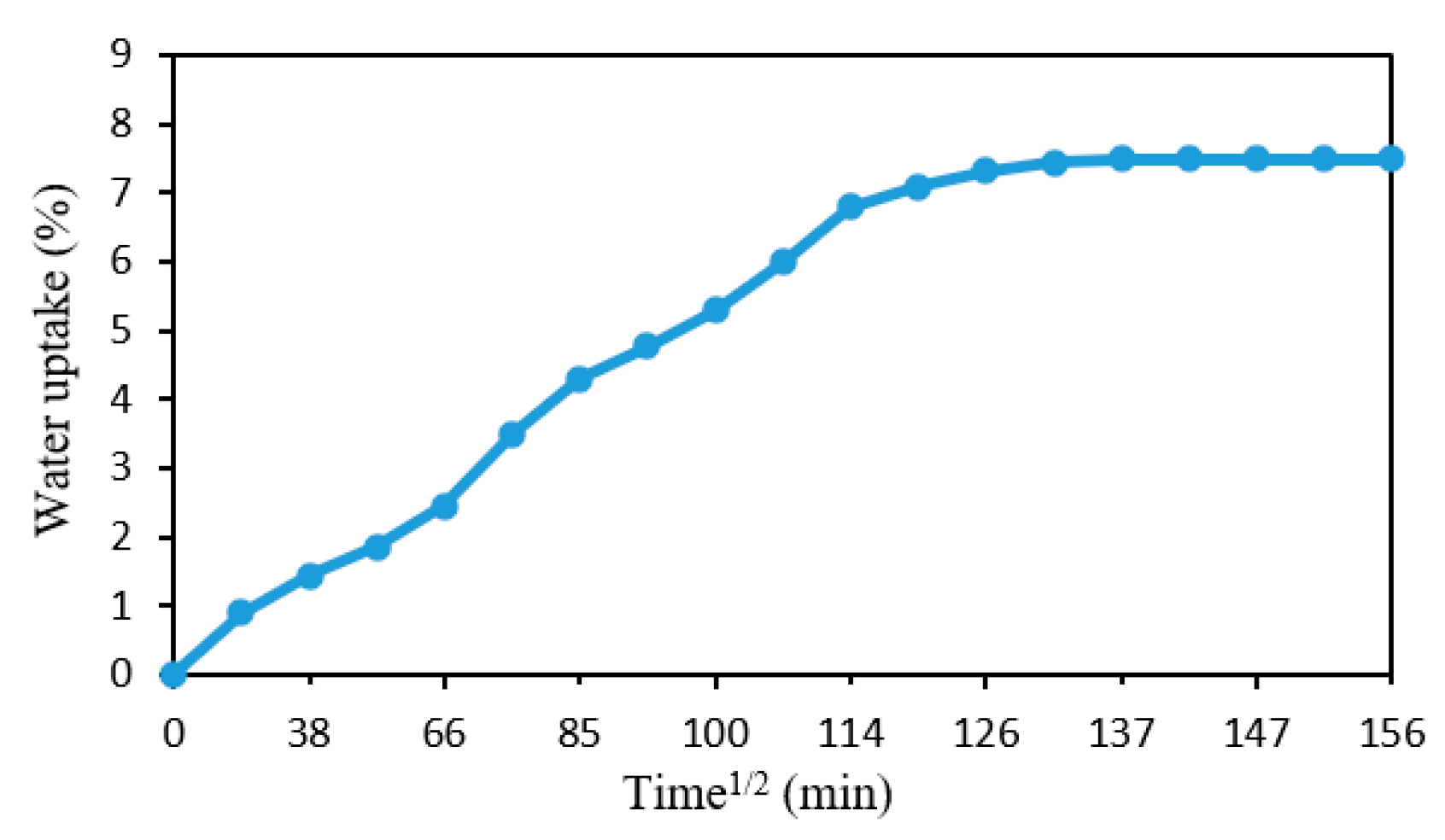

Figure 5 b displays the change in humidity content for the samples as a function of the square root of the hydrothermal ageing time. In this figure, the curve can be divided into two steps. At the beginning of step 1, experimental values of humidity content for all studied samples increased proportionally to the square root of ageing time. The sharply rising slope indicated quick humidity absorption processes in the samples. The same behaviour was seen in the literature on epoxy-based composites [

23,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Water absorption after 24 h was 1.47%, calculated in accordance with ASTM D570. According to the literature [

37,

38] epoxy matrices alone, for instance, can absorb up to 5 wt% of their weight in water, which affects their mechanical performance. After achieving certain humidity contents in stage 1, moisture uptakes of samples slowed down until reaching the humidity quasi-equilibrium plateau with a maximum water uptake of approximately 7.5 %.

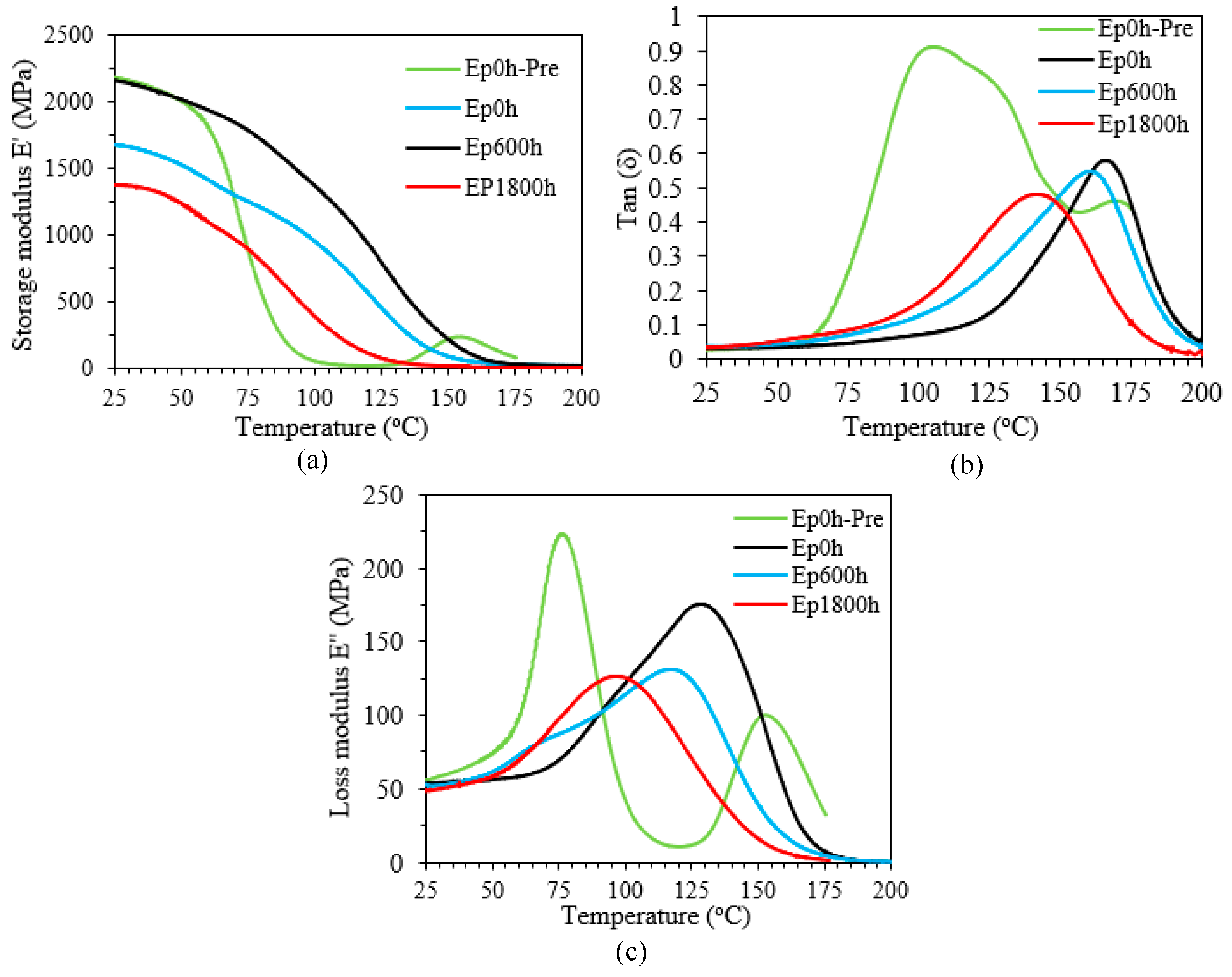

3.2. Viscoelastic Behaviour

DMTA was used to determine the possible changes in the viscoelastic behaviour by exposing the 3DP-Ep components to a broad range of temperatures values under an oscillating load. The damping factor (

tan(δ)), storage modulus (

E') and loss modulus (E") behaviour of the 3DPd epoxy-based samples before and after short and long hydrothermal ageing are presented in Figures 6a, 6b and 6c, respectively.

Table 1 shows the

Tg, E' and E" properties of the 3DP-Ep components before and after the hydrothermal ageing. EP0h-Pre represented the 3DPd sample before thermal post-curing of the three hours at 135°C. The EP0h-Pre 3DPd sample undergoes early in the glass transition state (rubbery) at about 70 °C. This is typically seen where polymer entanglement or crosslinking occurs due to molecular chain mobility, and chains can slide past each other [

30,

39]. It was observed that after the hydrothermal ageing in the distilled water at 45

oC, the curves of

Tg,

E' and E" were shifted to the left, and all the results were reduced after the 600 h and 1800 h hydrothermal degradation. As seen from the Table, the reduction in the

Tg from (

tan (δ)) curves are 4.8 % and 11.7 %, i.e., after 600 h and 1800 h of the hydrothermal ageing, respectively. On the other hand, the

E' was reduced by about 23 % and 19 %, respectively. This behaviour, for example, can play a vital role in the behaviour of the SMP in that the materials enter the rubbery region from the glass transition region early.

Figure 6.

Viscoelastic properties of the 3DP-Ep before and after the hydrothermal ageing: (a) E', (b) (tan(δ)) and (c) E".

Figure 6.

Viscoelastic properties of the 3DP-Ep before and after the hydrothermal ageing: (a) E', (b) (tan(δ)) and (c) E".

Table 2.

Tg, E' and E" properties of the 3DP-Ep before and after the hydrothermal ageing.

Table 2.

Tg, E' and E" properties of the 3DP-Ep before and after the hydrothermal ageing.

| Property |

Ep0h-Pre |

Ep0h |

Ep600h |

Ep1800h |

|

Tg (oC) (tan (δ)) |

105.3 |

166.7 |

159.1 |

142.5 |

|

Tg (oC) (E") |

76.8 |

128.9 |

117.5 |

96.2 |

| E' (MPa), T= 25 oC |

2184 |

2159 |

1679 |

1368 |

| E’’ (MPa), T= 25 oC |

55.8 |

53.6 |

52.3 |

48.9 |

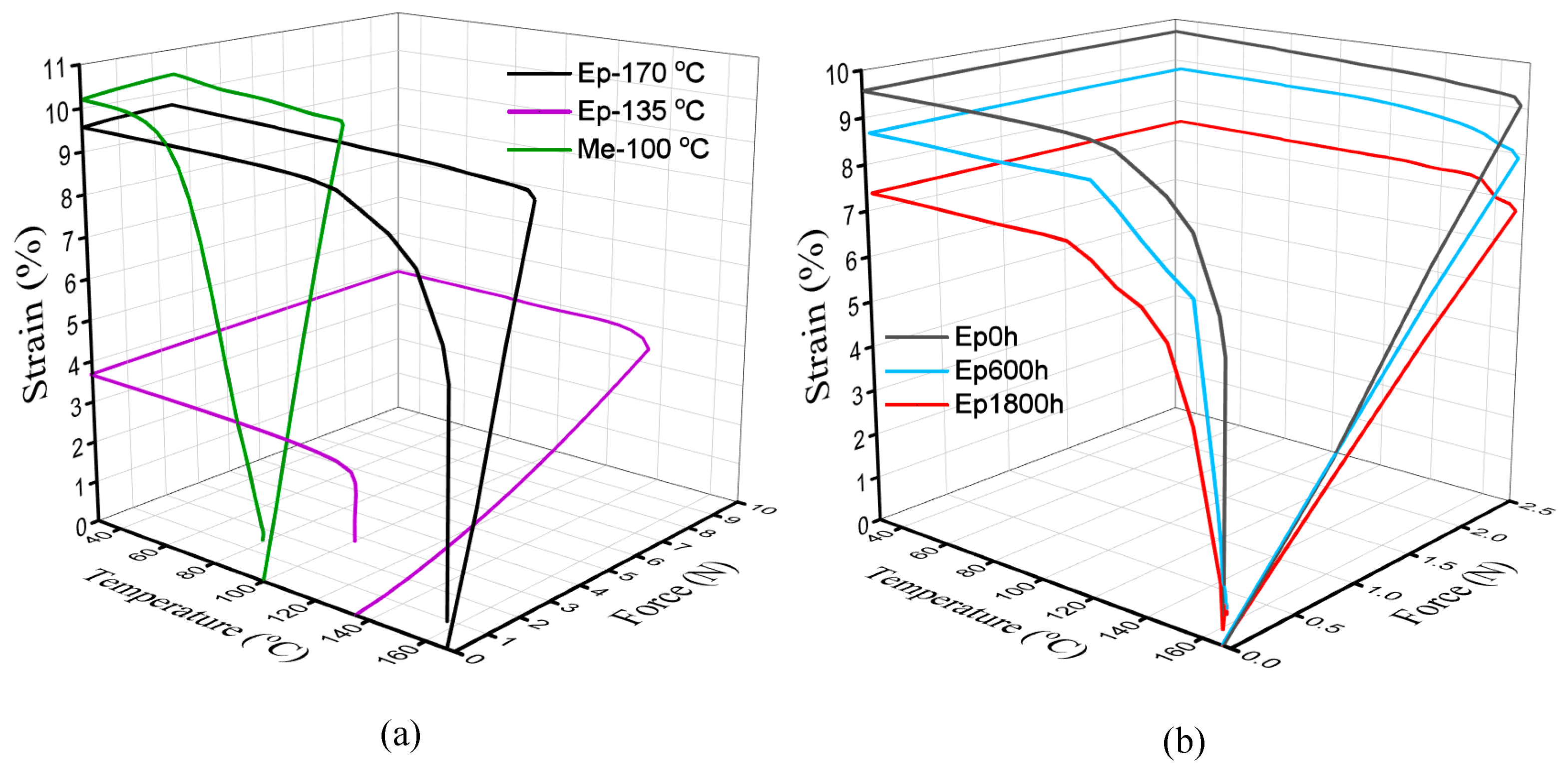

3.3. SMP Behaviour

The SMP performance of the 3DPd epoxy-based objects undertaking repeated 4-step-DMTA thermomechanical cycles is demonstrated in

Figure 7.

Table 3 displays the shape fixity and shape recovery values calculated by equations 2 and 3 in section 2.3.

Figure 9a represents the 4-step thermomechanical SMP cycle for the 3DP-Ep (135

oC and 170

oC) and the methacrylate-based resin (Tough-Blk-20 resin, 3D Systems, referred as Me-100

oC). The 3DP-Ep samples heated to 135

oC and 170

oC with applied loads 10 N and 2.5, respectively, were conducted (

Figure 7). Hence, molecular chain mobility increased, and shape-changing became easier in the end glass transition region and rubbery region. Therefore, the strain result for the Ep-135

oC was less than Ep-170

oC (Ep0h). This indicated that the molecular mobility level was low and still under the glass transition region for the Ep-135

oC, while the Ep-170

oC showed a high molecular mobility level under the rubbery region. Therefore, as shown in

Table 3, the shape fixity and shape recovery values for the Ep-135

oC are less than 90%.

On the other hand, the 4-step thermomechanical cycle of the Ep-170 oC showed similar behaviour to the Me-100 oC (Tg was 83.2 oC, from tan (δ) results), which both were heated above Tg within the rubbery region of the 3DPd material.

Figure 6b shows the effect of the hydrothermal degradation on the 4-step-DMTA thermomechanical cycles after (0 h, 600 h, and 1800 h) hydrothermal accelerating ageing in distilled water. Compared to the unaged sample, the strain values were reduced after ageing by about 10% and 29% for the Ep600h and Ep800h, respectively. However, the deformation occurred earlier at high temperatures due to the reduction of the

Tg after 600 h and 1800 h hydrothermal ageing as described in the viscoelastic behaviour section that the difference increased between

Tg and heating up to (170) leads to higher molecular chain mobility for the hydrothermal aged samples. In spite of long-term temperature and humidity ageing, the shape fixity and shape recovery values were still higher than 90%.

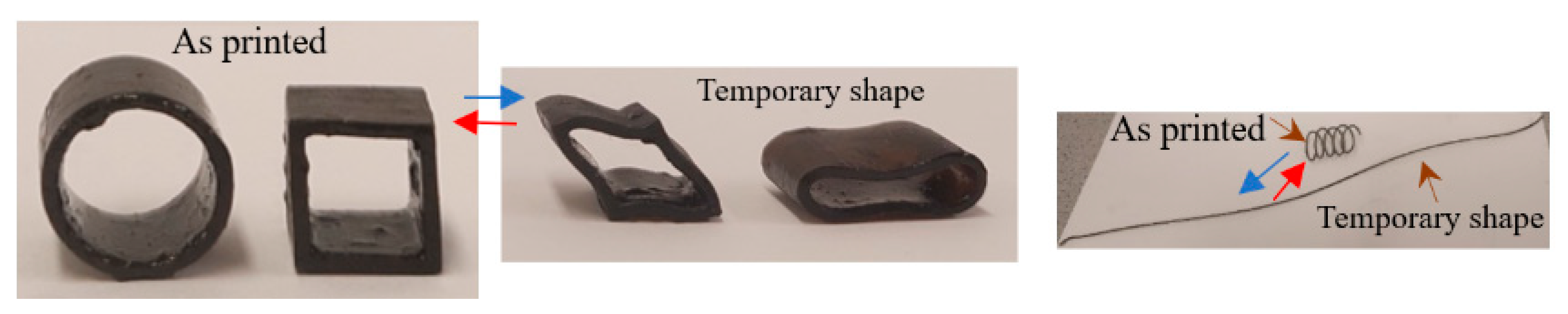

The SMP behaviour of the sequential deployment and shape-changing for the flat and circular 3DPd samples is due to thermal heating to assess the shape programming (shape fixing) and shape recovery behaviour. The 3DP-Ep sample is thermally heated in sunflower oil to a temperature close to the

Tg (160 °C). The average shape fixity and shape recovery values were calculated by equations 4 and 5 in section 2.3. The average shape fixity and shape recovery values were 98% and 92% for the flat sample, respectively; These average values were 96% and 88% for the circular 3DPd sample, respectively. Therefore, this 3DP-Ep material can be used for various SMP applications like actuators and thermal sensors.

Figure 8 shows the programmed (temporary) and recovery shapes by heating above

Tg and cooling to room temperature of the 3DPd Epoxy-based structures.

Figure 8.

3DPd Epoxy-based structures demonstrate temporary and recovery shapes.

Figure 8.

3DPd Epoxy-based structures demonstrate temporary and recovery shapes.

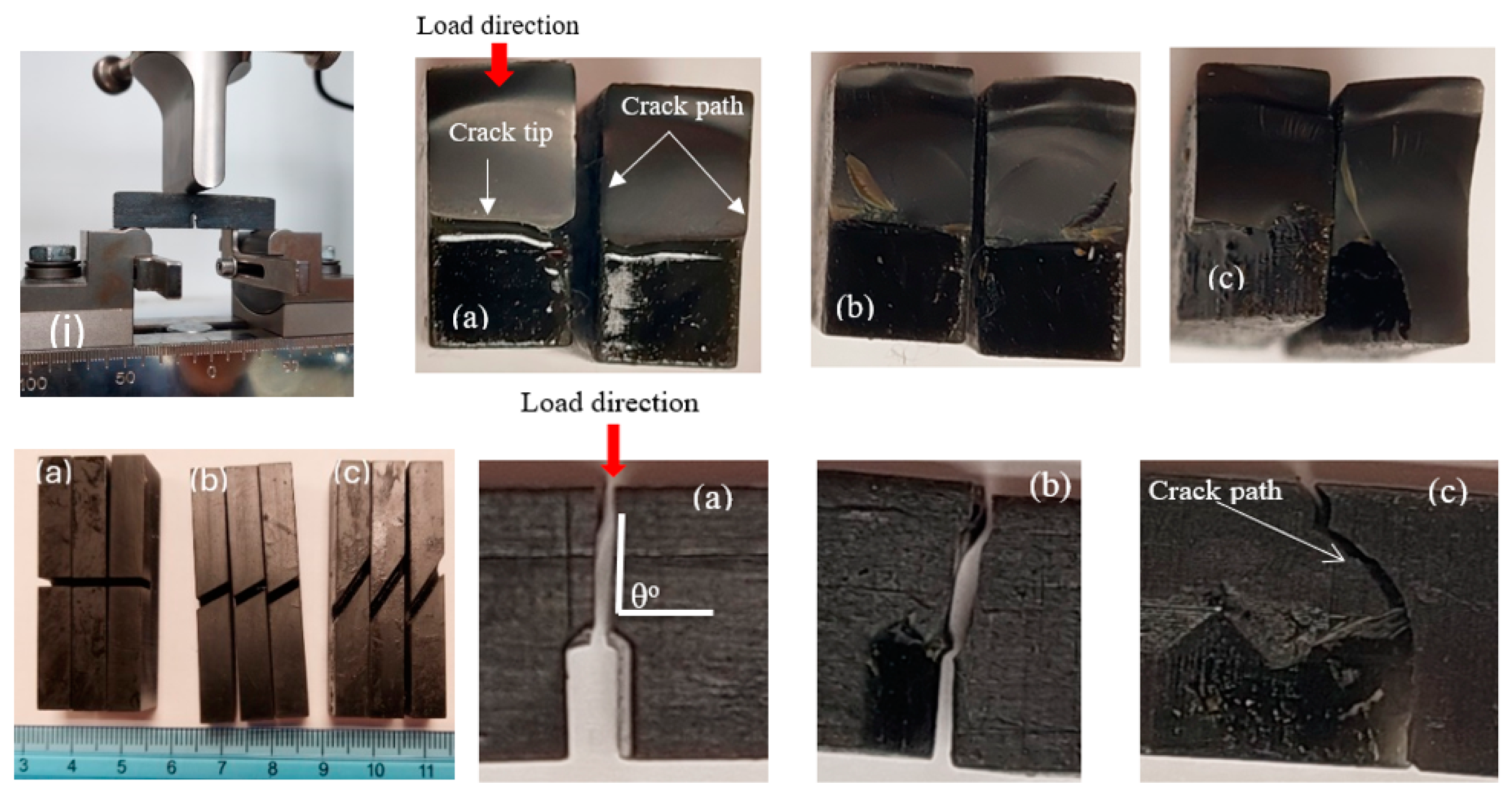

3.4. Mixed Mode I/III Fracture Toughness Behaviour

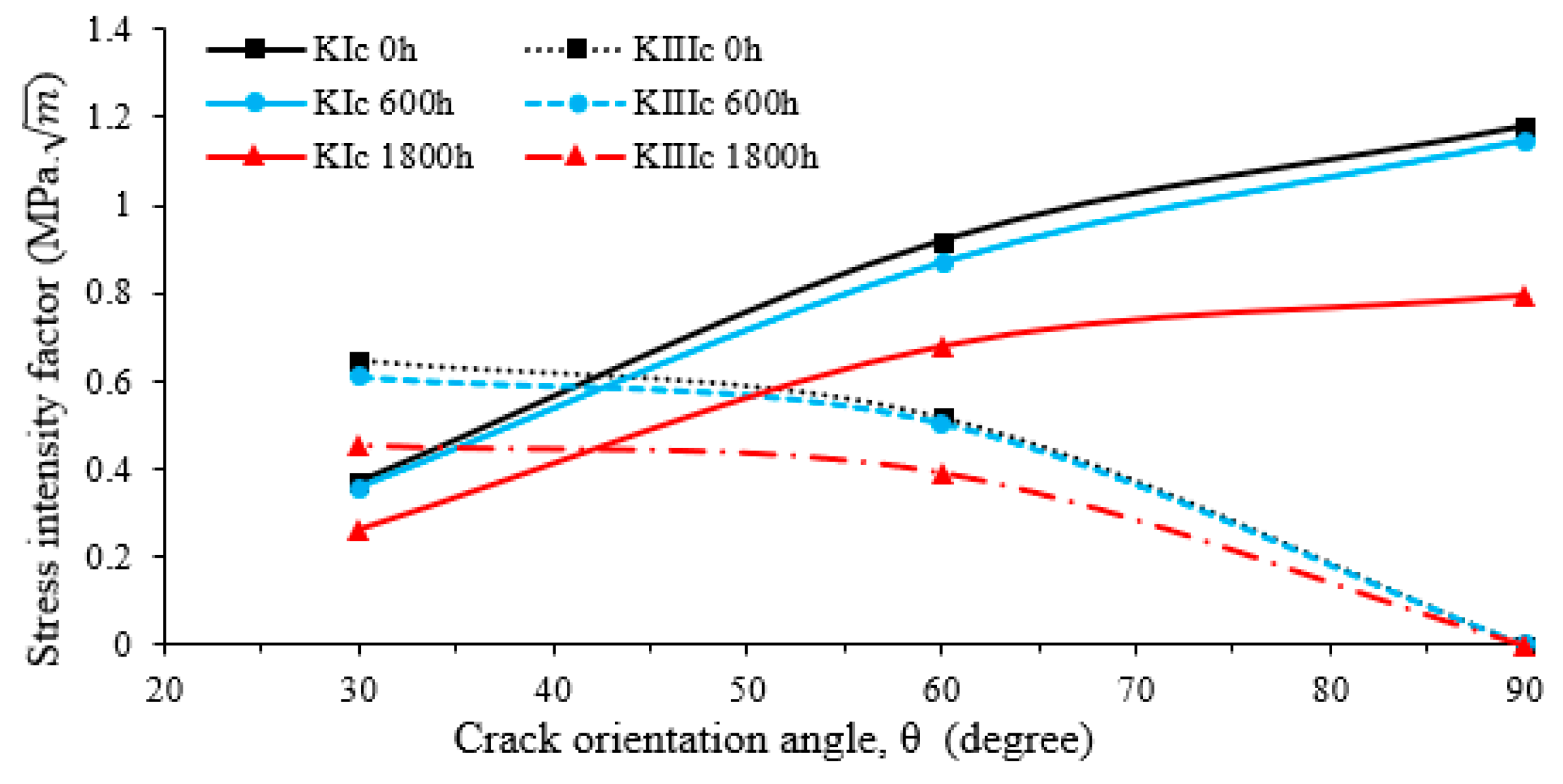

The fracture toughness of the 3DP-Ep beams with different crack inclination angles was investigated for the mode I (opening) and mixed-mode I/III (Opening and tearing) loading conditions.

Table 4 represents the fracture loads of the SENB specimens resulting from the TPB test. The fracture load of SENB specimens of the unaged samples reached its maximum value (407.8 N) at θ = 30

0 and gradually reduced when the crack inclination angle was increased to reach 322.3 N at θ = 90

0 with a fracture load reduction of about 21%. These values were reduced under 600 h and 1800 h of the hydrothermal accelerating ageing in the distilled water to 286.3 N and 217.6 N at angles 30

0 and 90

0, respectively.

Figure 9 shows the mode I and mixed mode I/III critical stress intensity factors,

KIc and

KIIIc, respectively, with various crack inclination angles of the epoxy-based 3DPd beams with the effect of short and long hydrothermal ageing intervals. This figure shows that when the crack inclination angle changed from 30

o to 90

o, the

KIc increased to reach the highest values at θ = 90

o as 1.18 MPa√m of un-aged samples. In contrast,

KIIIc reached maximum values at θ = 30

o. As expected, at θ = 90

o,

KIIIc values reached zero, which means no tearing loading when the crack is in the same loading direction.

KIc and

KIIIc values are expected to be equal at the crack inclination of 45

o due to equal loading conditions.

The increment in KIIIc values was attributed to the increase in surface area at the notch section, owing to the various notch inclination angles, which increased the crack propagate resistance and, thus, the fracture toughness of the cracked material.

The

KIc and

KIIIc values of the 3DPd beams were influenced by the immersion periods in distilled water. Hence, the

KIc and

KIIIc values were reduced after 600 h and 1800 h hydrothermal ageing, respectively. The reduction of the

KIc values was about (2%, 6%, and 4%) for the crack angles (90

o, 60

o and 30

o) after 600 h of ageing, while its reduction values after 1800 h of long ageing were (32%, 26%, and 29%). On the other hand, the reduction of the

KIIIc values for the 600 h ageing interval was about (3% and 7%) for the crack angles (60

o and 30

o), while its reduction values after 1800 h of ageing were (24% and 30%). This behaviour was attributed to degradation caused by the temperature and moisture of the hydrothermal ageing, which weakened the interfacial adhesion between the constituents and led to increasing the stress concentration areas [

14,

40,

41,

42]. Therefore, the long-ageing phenomenon generated remarkable degradation that significantly reduced the fracture toughness of the investigated epoxy-base 3DPd beams.

Figure 9.

Mode I and mixed mode I/III critical stress intensity factors of the 3DP-Ep beams.

Figure 9.

Mode I and mixed mode I/III critical stress intensity factors of the 3DP-Ep beams.

Figure 10 presents The broken surfaces of the failed SENB samples under the 3-point bending (3PB) test with various crack angles. Generally, the crack was propogated continuously along the preliminary crack when θ = 90

o. On the other hand, for θ< 90

o, the crack was almost propagated at the same angle as the preliminary crack. Several researchers in the literature noticed the same behaviour that the crack was propagated by the twisted path for θ< 90

o [

14,

17,

21]. The bright crack surface (

Figure 11 (a)) showed the brittle behaviour of the mode I fracture. When the crack inclination angle was less than 90

o, crack propagation was turned from a nearly straight path of the crack (

Figure 11 (a)) to curved-path crack propagation (

Figure 11 (b) and (c)).

4. Conclusions and Future Scope

This experimental study investigated the influence of hydrothermal accelerating ageing at 45 oC on the viscoelastic, shape memory, and mixed mode I/III fracture toughness of the 3D-printed epoxy-based resin. A UV-based DLP 3D printer was used to manufacture the samples, followed by UV and thermal post-curing. The FTIR spectra of the 3DP-Ep samples showed that all intensity peaks became almost lower with long-term immersion. The heat flow of the 3DPd sample from the DSC test showed the glass transition temperature at about 140 °C. The 3DP-Ep objects exhibited a maximum water uptake of 11.5 %. The temperature and humidity of the long-term ageing in distilled water significantly deteriorated the viscoelastic performance in terms of storage modulus and Tg. The reduction in the storage modulus and Tg (tan (δ)) were 11.7% and 23%, respectively, after 1800 h ageing.

The calculated shape fixity and shape recovery from the 4-step thermomechanical cycles were less than 90% for the samples heated lower than Tg from tan(δ). The shape-changing region between the Tg value from the loss modulus and the Tg value from the tan(δ) is considered a glass transition region due to about 80% to 99% of the shape being recovered in this region. The strain values were reduced by 29% after long-term ageing compared to the unaged sample. Nevertheless, the deformation occurred earlier at high temperatures due to the reduction of the Tg after long-term ageing, which led to higher molecular chain mobility for the hydrothermally aged samples. Despite long-term temperature and humidity ageing, the shape fixity and shape recovery values were still higher than 90%. The sequential deployment and shape-changing for the flat and circular 3DPd structures due to thermal trigger exhibited good shape programming (higher than 88%) and shape recovery behaviour (higher than 96%).

The fracture toughness of the 3DP-Ep beams with various crack inclination angles in mode I and mixed-mode I/III loading conditions was investigated using the SENB test. The SENB load values were reduced after the 600 h and 1800 h hydrothermal ageing. The long ageing phenomenon generated remarkable degradation that significantly reduced the fracture toughness values (KIc and KIIIc) for the crack angles (90o, 60o and 30o) of the investigated epoxy-based 3DPd beams. After 1800 h of ageing, the maximum reduction of the KIc values was 32%, 26%, and 29%, while the decrement in the KIIIc values was 24% and 30% due to the degradation caused by the temperature and moisture, which weakened the interfacial adhesion between the constituents and led to increased stress concentration areas. This study provides concepts for developing durable functionally graded epoxy-based structures showing shape memory properties to expand the use of 4DPg technology in various applications such as soft robotics, actuators, thermal sensors, marines and deployable structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.A.; methodology, M.A.; resources, MA, D.D., C.T.M. and E.P.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A. and T.A.S.; writing—review and editing, M.A., E.P.H., T.A.S. and D.D.; visualisation, M.A.; supervision, C.T.M., E.P.H. and D.D.; project administration, D.D.; funding acquisition, M.A., C.T.M. and D.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research project is funded by Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 847577 cofounded by the European Regional Development Fund and Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) (Currently Research Ireland) under Grant Number SFI/16/RC/3918 (Smart Manufacturing, Confirm Centre, UL).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request to the interested researchers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express gratitude to leading engineer James Wall for utilising the resin Tough Blk-20 and Figure® 4 DLP printer at 3D Technology Ltd company, Galway, Ireland. The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the engineer Aaron Maloney, PRISM Research Institute, Technological University of the Shannon, for their support in conducting the mechanical tests. The corresponding author would like to acknowledge EireComposites Company for their support. Dr. Tamer Sebaey would like to acknowledge Prince Sultan University for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iftekar, S.F.; Aabid, A.; Amir, A.; Baig, M. Advancements and Limitations in 3D Printing Materials and Technologies: A Critical Review. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15, 2519. https://doi:10.3390/polym15112519. [CrossRef]

- Naghshineh, B.; Ribeiro, A.; Jacinto, C.; Carvalho, H. Social Impacts of Additive Manufacturing: A Stakeholder-Driven Framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 164, 120368. https://doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120368. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Akram, T.; Shenggui, C.; Chen, H. Revolutionizing Manufacturing: A Review of 4D Printing Materials, Stimuli, and Cutting-Edge Applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 266, 110952. https://doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110952. [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M.; Hinchy, E.P.; McCarthy, C.T.; Moritz, V.F.; Zhuo, S.; Fuenmayor, E.; Devine, D.M. Liquid-Based 4D Printing of Shape Memory Nanocomposites: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 35. https://doi:10.3390/jmmp7010035. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, B.; Ye, H.; Jian, B.; He, X.; Cheng, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; Lin, J.; et al. Reconfigurable 4D Printing via Mechanically Robust Covalent Adaptable Network Shape Memory Polymer. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10. https://doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl4387. [CrossRef]

- Pommer, R.; Saf, R.; Supplit, R.; Holzner, A.; Plank, H.; Trimmel, G. Thermally-Triggered Multi-Shape-Memory Behavior of Binary Blends of Cross-Linked EPDM with Various Thermoplastic Polyethylenes and Their Potential Applications as Temperature Indicators. Polymer (Guildf). 2023, 284, 126302. https://doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2023.126302. [CrossRef]

- Baer, G.; Wilson, T.S.; Matthews, D.L.; Maitland, D.J. Shape-memory Behavior of Thermally Stimulated Polyurethane for Medical Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 103, 3882–3892. https://doi:10.1002/app.25567. [CrossRef]

- Inverardi, N.; Pandini, S.; Bignotti, F.; Scalet, G.; Marconi, S.; Auricchio, F. Sequential Motion of 4D Printed Photopolymers with Broad Glass Transition. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2020, 305. https://doi:10.1002/mame.201900370. [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M.; Hinchy, E.P.; McCarthy, C.T.; Moritz, V.F.; Portela, A.; Devine, D.M. Investigation of Thermal, Mechanical and Shape Memory Properties of 3D-Printed Functionally Graded Nanocomposite Materials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2658. https://doi:10.3390/nano13192658. [CrossRef]

- Ameen, A.A.; Takhakh, A.M.; Abdal-hay, A. An Overview of the Latest Research on the Impact of 3D Printing Parameters on Shape Memory Polymers. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 194, 112145. https://doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.112145. [CrossRef]

- Nian, Y.; Wan, S.; Avcar, M.; Yue, R.; Li, M. 3D Printing Functionally Graded Metamaterial Structure: Design, Fabrication, Reinforcement, Optimization. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 258, 108580. https://doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2023.108580. [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Yang, W.; Li, C.-Q. Stress Intensity Factors for Mixed Mode Fracture Induced by Inclined Cracks in Pipes under Axial Tension and Bending. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2017, 89, 100–109. https://doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2017.02.001. [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M.; Erkliğ, A.; Bulut, M. Mixed-Mode I/III Fracture Toughness of Polymer Matrix Composites Toughened with Waste Particles. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2018, 25, 679–687. https://doi:10.1515/secm-2016-0326. [CrossRef]

- Omidvar, N.; Aliha, M.R.M.; Khoramishad, H. Hygrothermal Degradation of MWCNT/Epoxy Brittle Materials under I/II Combined Mode Loading Conditions: An Experimental, Micro Structural and Theoretical Study. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 125, 103896. https://doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2023.103896. [CrossRef]

- Torabi, A.R.; Kamyab, M. Mixed Mode I/II Failure Prediction of Thin U-Notched Ductile Steel Plates with Significant Strain-Hardening and Large Strain-to-Failure: The Fictitious Material Concept. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids 2019, 75, 225–236. https://doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2019.02.004. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, A.S.; Ayatollahi, M.R.; Torabi, A.R. Fracture Study in Notched Ductile Polymeric Plates Subjected to Mixed Mode I/II Loading: Application of Equivalent Material Concept. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids 2018, 70, 37–43. https://doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2018.01.009. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Huang, J.; Gan, Z.; Dong, S.; Hua, W. Analysis of Mixed-Mode I/II/III Fracture Toughness Based on a Three-Point Bending Sandstone Specimen with an Inclined Crack. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1652. https://doi:10.3390/app11041652. [CrossRef]

- Ilyaei, S.; Abubasir, Y.; Sourki, R. PLA-Based 3D Printed Porous Scaffolds under Mixed-Mode I/III Loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 265, 108382. https://doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2022.108382. [CrossRef]

- Aliha, M.R.M.; G. Kouchaki, H.; Jafari Haghighatpour, P. Designing a Simple and Suitable Laboratory Test Specimen for Investigating the General Mixed Mode I/II/III Fracture Problem. Mater. Des. 2023, 236, 112477. https://doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112477. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wang, C. Mixed-Mode I/III Fracture. In Rock Fracture Mechanics and Fracture Criteria; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2024; pp. 89–112.

- Avci, A.; Akdemir, A.; Arikan, H. Mixed-Mode Fracture Behavior of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 243–247. https://doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.07.003. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, A.; Liao, H.-T.; Chiang, F.; Korach, C.S. Time-Dependent Changes in Mechanical Properties of Carbon Fiber Vinyl Ester Composites Exposed to Marine Environments. Compos. Struct. 2016, 144, 80–85. https://doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2016.02.053. [CrossRef]

- Banjo, A.D.; Agrawal, V.; Auad, M.L.; Celestine, A.-D.N. Moisture-Induced Changes in the Mechanical Behavior of 3D Printed Polymers. Compos. Part C Open Access 2022, 7, 100243. https://doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2022.100243. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H.; Hu, W.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Effect of Nanoparticle and Glass Fiber on the Hydrothermal Aging of Polyamide 6. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137. https://doi:10.1002/app.49585. [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, B.; Karbhari, V.M. Characteristics and Models of Moisture Uptake in Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Topical Review. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16, 2265. https://doi:10.3390/polym16162265. [CrossRef]

- Sebaey, T.A. Crashworthiness of GFRP Composite Tubes after Aggressive Environmental Aging in Seawater and Soil. Compos. Struct. 2022, 284, 115105. https://doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.115105. [CrossRef]

- 3D Systems Inc., Figure 4 TOUGH-BLK 20, Https://Www.3dsystems.Com/Materials/Figure-4-Tough-Blk-20, Last Accessed 2023/19/10.

- Choong, Y.Y.C.; Maleksaeedi, S.; Eng, H.; Wei, J.; Su, P.C. 4D Printing of High Performance Shape Memory Polymer Using Stereolithography. Mater. Des. 2017, 126, 219–225. https://doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2017.04.049. [CrossRef]

- ALSAADI, M.; HINCHY, E.P.; MCCARTHY, C.T.; DEVINE, D.M. Effect of Graphene Nanoplatelets and Accelerated Weathering on the Mechanical and Shape Memory Behaviour of 3D Printed Components. Eurasia Proc. Sci. Technol. Eng. Math. 2024, 28, 47–55. https://doi:10.55549/epstem.1519155. [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, M.; Hinchy, E.P.; McCarthy, C.T.; de Lima, T.A. de M.; Portela, A.; Coudray, T.; Devine, D.M. 4D Printing of Weather Resistant Structures Reinforced with Functionalised Graphene Nanoplatelets. In; 2025; pp. 188–195.

- Anderson, T.L.; Anderson, T.L. Fracture Mechanics; CRC Press, 2005; ISBN 9780429125676.

- Wu, H.; Chen, P.; Yan, C.; Cai, C.; Shi, Y. Four-Dimensional Printing of a Novel Acrylate-Based Shape Memory Polymer Using Digital Light Processing. Mater. Des. 2019, 171, 107704. https://doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.107704. [CrossRef]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Gagani, A.I.; Echtermeyer, A.T. Hygrothermal Aging of Amine Epoxy: Reversible Static and Fatigue Properties. Open Eng. 2018, 8, 447–454. https://doi:10.1515/eng-2018-0050. [CrossRef]

- Garden, L.; Pethrick, R.A. A Dielectric Study of Water Uptake in Epoxy Resin Systems. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134. https://doi:10.1002/app.44717. [CrossRef]

- LIU, W.; HOA, S.; PUGH, M. Water Uptake of Epoxy–Clay Nanocomposites: Experiments and Model Validation. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2066–2072. https://doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.07.024. [CrossRef]

- Dezulier, Q.; Clement, A.; Davies, P.; Arhant, M.; Flageul, B.; Jacquemin, F. Water Ageing Effects on the Elastic and Viscoelastic Behaviour of Epoxy-Based Materials Used in Marine Environment. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 242, 110090. https://doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110090. [CrossRef]

- Lavoratti, A.; Bianchi, O.; Cruz, J.A.; Al-Maqdasi, Z.; Varna, J.; Amico, S.C.; Joffe, R. Impact of Water Absorption on the Creep Performance of Epoxy/Microcrystalline Cellulose Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141. https://doi:10.1002/app.55365. [CrossRef]

- Starkova, O.; Gaidukovs, S.; Platnieks, O.; Barkane, A.; Garkusina, K.; Palitis, E.; Grase, L. Water Absorption and Hydrothermal Ageing of Epoxy Adhesives Reinforced with Amino-Functionalized Graphene Oxide Nanoparticles. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 191, 109670. https://doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2021.109670. [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Du, Z.; Fu, Q.; Gao, X.; Gong, J. Control of Polymer Properties by Entanglement: A Review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306. https://doi:10.1002/mame.202100536. [CrossRef]

- Glaskova-Kuzmina, T.; Aniskevich, A.; Papanicolaou, G.; Portan, D.; Zotti, A.; Borriello, A.; Zarrelli, M. Hydrothermal Aging of an Epoxy Resin Filled with Carbon Nanofillers. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12, 1153. https://doi:10.3390/polym12051153. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Feng, C.; Zhang, L.; Shan, J.; Shi, M. A Review of the Effect of Hydrothermal Aging on the Mechanical Properties of <scp>2D</Scp> Fiber-reinforced Resin Matrix Composites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35. https://doi:10.1002/pat.6239. [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M.; Alsaadi, M.; Erkliğ, A. The Effects of Nanosilica and Nanoclay Particles Inclusions on Mode II Delamination, Thermal and Water Absorption of Intraply Woven Carbon/Aramid Hybrid Composites. Int. Polym. Process. 2020, 35, 367–375. https://doi:10.3139/217.3940. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).