Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

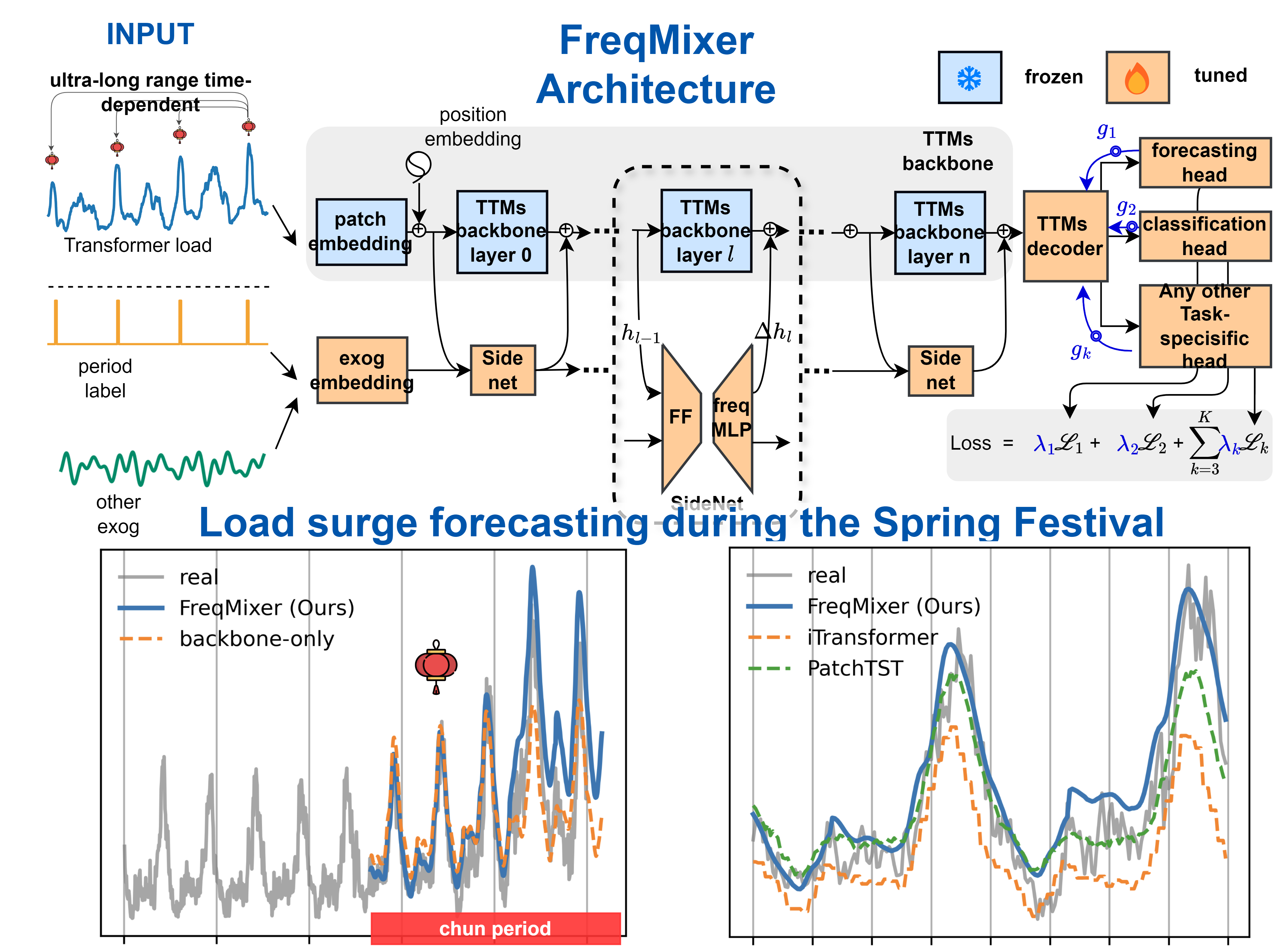

- We design a Side Network utilizing the PEFT (Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning) method with covariates to address long-term dependencies. Ablation experiments show that Side Net outperforms traditional methods like full trimming, head trimming, adapter, and LoRA in both time and frequency domains.

- We introduce frequency-domain features combined with PEFT during fine-tuning, enhancing model generalization with fewer parameters and improving performance in diverse scenarios.

- We implement a multi-task learning framework to boost model generalization in Smart Grid Management, mitigating overfitting by leveraging complementary knowledge across tasks, resulting in improved performance across multiple tasks.

2. Related Work

2.1. Foundation Models for Time Series Analysis

2.2. Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning

2.3. Multitask Learning

3. Methodologies of FreqMixer

3.1. Problem Formulation & End-to-End multitask Finetuning

3.2. Background of TTMs

3.3. End-to-End Multitask Finetuning Framework

4. Experiments

4.1. Data

4.2. Experimental Setting

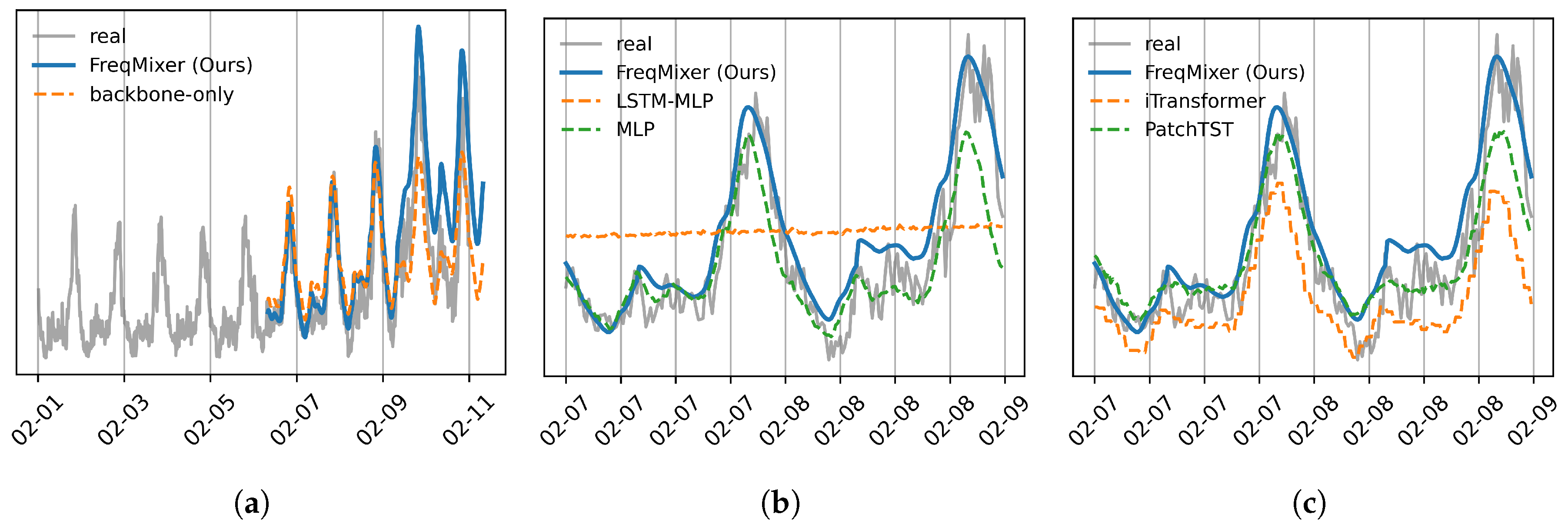

4.3. Load Forecasting in 2024 Spring Festival

4.4. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PEFT | Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning |

| TTMs | Tiny Time Mixers |

| MTL | Multi-Task Learning |

| FMs | Foundation Models |

References

- Ahmad, N.; Ghadi, Y.; Adnan, M.; Ali, M. Load forecasting techniques for power system: Research challenges and survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 71054–71090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nti, I.K.; Teimeh, M.; Nyarko-Boateng, O.; Adekoya, A.F. Electricity load forecasting: a systematic review. Journal of Electrical Systems and Information Technology 2020, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Dong, H.; Zheng, W.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Xi, L. Review and prospect of data-driven techniques for load forecasting in integrated energy systems. Applied Energy 2022, 321, 119269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haben, S.; Arora, S.; Giasemidis, G.; Voss, M.; Greetham, D.V. Review of low voltage load forecasting: Methods, applications, and recommendations. Applied Energy 2021, 304, 117798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Han, Y.; Wei, J. Electrical load prediction of healthcare buildings through single and ensemble learning. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 2751–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Iqbal, N.; Ahmad, R.; Kim, D.H. Ensemble prediction approach based on learning to statistical model for efficient building energy consumption management. Symmetry 2021, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Dong, Z.Y.; Jia, Y.; Hill, D.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Short-term residential load forecasting based on LSTM recurrent neural network. IEEE transactions on smart grid 2017, 10, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussein, M.; Aurangzeb, K.; Haider, S.I. Hybrid CNN-LSTM model for short-term individual household load forecasting. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 180544–180557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, S.; Afshari, A. Short-term load forecasts using LSTM networks. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2922–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumohsen, M.; Owda, A.Y.; Owda, M. Electrical load forecasting using LSTM, GRU, and RNN algorithms. Energies 2023, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, P.; Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Feng, B. Short-Term Heavy Overload Forecasting of Public Transformers Based on Combined LSTM-XGBoost Model. Energies 2023, 16, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Chen, X.; Zeng, X.; Kong, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, T. Short-term load forecasting of industrial customers based on SVMD and XGBoost. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2021, 129, 106830. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Ye, A.; Zhong, J.; Xu, D.; Yang, W.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, T.; Tian, Y.; et al. Bagging–XGBoost algorithm based extreme weather identification and short-term load forecasting model. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 8661–8674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Fu, X.; Zong, C. Short-term load forecasting method based on feature preference strategy and LightGBM-XGboost. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 75257–75268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jánošík, D. Enhanced short-term load forecasting with hybrid machine learning models: CatBoost and XGBoost approaches. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 241, 122686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Non-stationary transformers: Exploring the stationarity in time series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 9881–9893. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.; Kim, J.; Tae, Y.; Park, C.; Choi, J.H.; Choo, J. Reversible instance normalization for accurate time-series forecasting against distribution shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara, E.; Martinez, L.C.; De Oliveira, D.; Zimbrão, G.; Pappa, G.L.; Mattoso, M. Adaptive normalization: A novel data normalization approach for non-stationary time series. In Proceedings of the The 2010 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE; 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Timesnet: Temporal 2d-variation modeling for general time series analysis. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2210.02186. [Google Scholar]

- Oreshkin, B.N.; Carpov, D.; Chapados, N.; Bengio, Y. N-BEATS: Neural basis expansion analysis for interpretable time series forecasting. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1905.10437. [Google Scholar]

- Challu, C.; Olivares, K.G.; Oreshkin, B.N.; Ramirez, F.G.; Canseco, M.M.; Dubrawski, A. Nhits: Neural hierarchical interpolation for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence; 2023; Vol. 37, pp. 376989–6997. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2211.14730. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 27268–27286. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 37; 2023; pp. 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Sezer, O.B.; Gudelek, M.U.; Ozbayoglu, A.M. Financial time series forecasting with deep learning: A systematic literature review: 2005–2019. Applied soft computing 2020, 90, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samonas, M. Financial forecasting, analysis, and modelling: a framework for long-term forecasting; John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Sezer, O.B.; Gudelek, M.U.; Ozbayoglu, A.M. Financial time series forecasting with deep learning: A systematic literature review: 2005–2019. Applied soft computing 2020, 90, 106181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, R.; Singh, R.P.; et al. Financial and non-stationary time series forecasting using LSTM recurrent neural network for short and long horizon. In Proceedings of the 2019 10th international conference on computing, communication and networking technologies (ICCCNT). IEEE; 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Fan, S. Density forecasting for long-term peak electricity demand. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2009, 25, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, C.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Li, Q.; Yu, D.; Liu, J. Deep learning for renewable energy forecasting: A taxonomy, and systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 384, 135414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalehkhondabi, I.; Ardjmand, E.; Weckman, G.R.; Young, W.A. An overview of energy demand forecasting methods published in 2005–2015. Energy Systems 2017, 8, 411–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahogianni, E.I.; Karlaftis, M.G.; Golias, J.C. Short-term traffic forecasting: Where we are and where we’re going. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2014, 43, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Patras, P. Long-term mobile traffic forecasting using deep spatio-temporal neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eighteenth ACM International Symposium on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking and Computing, 2018, pp.; pp. 231–240.

- Qu, L.; Li, W.; Li, W.; Ma, D.; Wang, Y. Daily long-term traffic flow forecasting based on a deep neural network. Expert Systems with applications 2019, 121, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, U.K.; Vo<i>β</i>, A.; Singh, A.; Fahl, U.; Blesl, M.; Gallachóir, B.P.Ó. Energy and emissions forecast of China over a long-time horizon. Energy 2011, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, G.; Duan, Z.; Chen, C. Intelligent modeling strategies for forecasting air quality time series: A review. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 102, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalgren, P.W.; Byington, C.S.; Roemer, M.J.; Watson, M.J. Defining PHM, a lexical evolution of maintenance and logistics. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE autotestcon. IEEE; 2006; pp. 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, H.; Li, Y.F. A review on prognostics and health management (PHM) methods of lithium-ion batteries. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 116, 109405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zio, E. Prognostics and Health Management (PHM): Where are we and where do we (need to) go in theory and practice. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2022, 218, 108119. [Google Scholar]

- Ekambaram, V.; Jati, A.; Nguyen, N.H.; Dayama, P.; Reddy, C.; Gifford, W.M.; Kalagnanam, J. TTMs: Fast Multi-level Tiny Time Mixers for Improved Zero-shot and Few-shot Forecasting of Multivariate Time Series. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.03955, arXiv:2401.03955 2024.

- Das, A.; Kong, W.; Sen, R.; Zhou, Y. A decoder-only foundation model for time-series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.10688, arXiv:2310.10688 2023.

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Timer: Transformers for time series analysis at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02368, arXiv:2402.02368 2024.

- Woo, G.; Liu, C.; Kumar, A.; Xiong, C.; Savarese, S.; Sahoo, D. Unified training of universal time series forecasting transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02592, arXiv:2402.02592 2024.

- Garza, A.; Mergenthaler-Canseco, M. TimeGPT-1. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03589, arXiv:2310.03589 2023.

- Jin, M.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, J.Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, P.Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Pan, S.; et al. Time-llm: Time series forecasting by reprogramming large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.01728, arXiv:2310.01728 2023.

- Rasul, K.; Ashok, A.; Williams, A.R.; Khorasani, A.; Adamopoulos, G.; Bhagwatkar, R.; Biloš, M.; Ghonia, H.; Hassen, N.; Schneider, A.; et al. Lag-llama: Towards foundation models for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the R0-FoMo: Robustness of Few-shot and Zero-shot Learning in Large Foundation Models; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ekambaram, V.; Jati, A.; Nguyen, N.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. Tsmixer: Lightweight mlp-mixer model for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2023, pp.; pp. 459–469.

- Chang, C.; Peng, W.C.; Chen, T.F. Llm4ts: Two-stage fine-tuning for time-series forecasting with pre-trained llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.08469, arXiv:2308.08469 2023.

- Cao, D.; Jia, F.; Arik, S.O.; Pfister, T.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, W.; Liu, Y. Tempo: Prompt-based generative pre-trained transformer for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04948, arXiv:2310.04948 2023.

- Gruver, N.; Finzi, M.; Qiu, S.; Wilson, A.G. Large language models are zero-shot time series forecasters. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Koker, T.; Queen, O.; Hartvigsen, T.; Tsiligkaridis, T.; Zitnik, M. Units: Building a unified time series model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00131, arXiv:2403.00131 2024.

- Kornblith, S.; Shlens, J.; Le, Q.V. Do better imagenet models transfer better? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2019; pp. 2661–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Zaken, E.B.; Ravfogel, S.; Goldberg, Y. Bitfit: Simple parameter-efficient fine-tuning for transformer-based masked language-models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.10199, arXiv:2106.10199 2021.

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp.; pp. 9650–9660.

- Houlsby, N.; Giurgiu, A.; Jastrzebski, S.; Morrone, B.; De Laroussilhe, Q.; Gesmundo, A.; Attariyan, M.; Gelly, S. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 2790–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Ge, C.; Tong, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, P. Adaptformer: Adapting vision transformers for scalable visual recognition. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 16664–16678. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.09685, arXiv:2106.09685 2021.

- Zhang, J.O.; Sax, A.; Zamir, A.; Guibas, L.; Malik, J. Side-tuning: a baseline for network adaptation via additive side networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 16. Springer, 2020, August 23–28; pp. 698–714.

- Xu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, F.; Hu, H.; Bai, X. Side adapter network for open-vocabulary semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023, pp.; pp. 2945–2954.

- Chen, Z.; Duan, Y.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Lu, T.; Dai, J.; Qiao, Y. Vision transformer adapter for dense predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.08534, arXiv:2205.08534 2022.

- Sung, Y.L.; Cho, J.; Bansal, M. Lst: Ladder side-tuning for parameter and memory efficient transfer learning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 12991–13005. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, M.; Zhu, K.; Wu, J. Dtl: Disentangled transfer learning for visual recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol.; pp. 3812082–12090.

- Teichmann, M.; Weber, M.; Zoellner, M.; Cipolla, R.; Urtasun, R. Multinet: Real-time joint semantic reasoning for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE intelligent vehicles symposium (IV). IEEE; 2018; pp. 1013–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Zhang, T.; Süsstrunk, S.; Salzmann, M. Mult: An end-to-end multitask learning transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp.; pp. 12031–12041.

- Hu, R.; Singh, A. Unit: Multimodal multitask learning with a unified transformer. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp.; pp. 1439–1449.

- Kendall, A.; Gal, Y.; Cipolla, R. Multi-task learning using uncertainty to weigh losses for scene geometry and semantics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp.; pp. 7482–7491.

- Chen, Z.; Badrinarayanan, V.; Lee, C.Y.; Rabinovich, A. Gradnorm: Gradient normalization for adaptive loss balancing in deep multitask networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2018; pp. 794–803. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Johns, E.; Davison, A.J. End-to-end multi-task learning with attention. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp.; pp. 1871–1880.

- Guo, M.; Haque, A.; Huang, D.A.; Yeung, S.; Fei-Fei, L. Dynamic task prioritization for multitask learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp.; pp. 270–287.

- Sener, O.; Koltun, V. Multi-task learning as multi-objective optimization. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, K.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, P.; He, H.; An, N.; Lian, D.; Cao, L.; Niu, Z. Frequency-domain MLPs are more effective learners in time series forecasting. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, L.; Long, M. itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06625, arXiv:2310.06625 2023.

- Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Shi, X.; Hu, T.; Luo, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, J. Timemixer: Decomposable multiscale mixing for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.14616, arXiv:2405.14616 2024.

- Massaoudi, M.; Refaat, S.S.; Chihi, I.; Trabelsi, M.; Oueslati, F.S.; Abu-Rub, H. A novel stacked generalization ensemble-based hybrid LGBM-XGB-MLP model for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Energy 2021, 214, 118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Keynia, F. Mid-term electricity load forecasting by a new composite method based on optimal learning MLP algorithm. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2020, 14, 845–852. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Peng, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, W. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2021, Vol.; pp. 3511106–11115.

| model | Leadtime/Metric | 1hour | 3hour | 6hour | 12hour | 1day | 2day | 3day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOTA TSF Models | TSMixerx | MAPE | 23.82 | 44.87 | 49.23 | 28.46 | 30.82 | 51.82 | 31.16 |

| Recall | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Precision | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| iTransformer | MAPE | 23.9 | 24.68 | 26 | 27.44 | 30.22 | 34.75 | 37.37 | |

| Recall | 0.176 | 0.118 | 0.059 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Precision | 0.750 | 1.000 | 0.333 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| TimeMixer | MAPE | 17.79 | 20.71 | 24.22 | 25.38 | 27.49 | 33.07 | 37.06 | |

| Recall | 0.294 | 0.176 | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Precision | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| PatchTST | MAPE | 18.39 | 19.91 | 20.66 | 22.98 | 26.6 | 30.71 | 33.07 | |

| Recall | 0.882 | 0.588 | 0.412 | 0.235 | 0.294 | 0.118 | 0.000 | ||

| Precision | 0.441 | 0.455 | 0.333 | 0.235 | 0.139 | 0.047 | 0.000 | ||

| Baseline | lstm+mlp | MAPE | 26.09 | 26.33 | 26.74 | 27.48 | 28.38 | 29.50 | 29.86 |

| Recall | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Precision | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| mlp | MAPE | 16.38 | 17.33 | 18.48 | 20.38 | 23.80 | 26.28 | 32.00 | |

| Recall | 0.700 | 0.600 | 0.650 | 0.450 | 0.500 | 0.250 | 0.158 | ||

| Precision | 0.519 | 0.500 | 0.481 | 0.310 | 0.385 | 0.208 | 0.125 | ||

| Foundation | FreqMixer | MAPE | 13.31 | 15.04 | 16.1 | 16.87 | 17.17 | 21.43 | 24.53 |

| Recall | 0.706 | 0.647 | 0.647 | 0.706 | 0.706 | 0.647 | 0.706 | ||

| Precision | 0.706 | 0.917 | 0.733 | 0.632 | 0.600 | 0.355 | 0.255 | ||

| TTms | MAPE | 23.27 | 27.85 | 28.32 | 28.56 | 29.72 | 42.76 | 53.54 | |

| Recall | 0.880 | 1.000 | 0.650 | 0.450 | 0.400 | 0.250 | 0.150 | ||

| Precision | 0.595 | 0.652 | 0.382 | 0.281 | 0.286 | 0.122 | 0.056 | ||

| Avg Imp. over best SOTA | MAPE ↓: -23.65%, Recall ↑: 87.42%, Precision ↑: 72.32% | ||||||||

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1_score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FreqMixer | 0.9489 | 0.5652 | 0.619 | 0.5909 |

| Dlinear | 0.8324 | 0.1935 | 0.5714 | 0.2892 |

| mlp | 0.0653 | 0.0575 | 0.9524 | 0.1084 |

| lstm | 0.0597 | 0.0597 | 1 | 0.1126 |

| Avg Imp. | 14.00% | 2× | 8.33% | 1× |

| TASK | Single task | Multi task | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| METHOD | full | head | Adapter | LoRA | SideNet | full | head | Adapter | LoRA | SideNet | |

| lead 1 day | MAE | 0.077 | 0.156 | 0.072 | 0.073 | 0.073 | 0.081 | 0.144 | 0.077 | 0.095 | 0.077 |

| MSE | 1.015 | 3.819 | 0.834 | 0.875 | 0.860 | 1.123 | 3.504 | 1.005 | 1.435 | 0.974 | |

| MAPE | 28.987 | 64.937 | 28.084 | 28.497 | 28.316 | 30.744 | 55.238 | 30.226 | 36.770 | 30.366 | |

| Accuracy | 0.241 | 0.000 | 0.433 | 0.406 | 0.433 | 0.176 | 0.000 | 0.400 | 0.161 | 0.429 | |

| Precision | 0.318 | 0.000 | 0.448 | 0.419 | 0.448 | 0.231 | 0.000 | 0.429 | 0.227 | 0.462 | |

| Recall | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.929 | 0.929 | 0.929 | 0.429 | 0.000 | 0.857 | 0.357 | 0.857 | |

| F1 score | 0.389 | 0.000 | 0.605 | 0.578 | 0.605 | 0.300 | 0.000 | 0.571 | 0.278 | 0.600 | |

| lead 5 day | MAE | 0.219 | 0.179 | 0.205 | 0.215 | 0.214 | 0.259 | 0.155 | 0.206 | 0.265 | 0.215 |

| MSE | 6.240 | 4.893 | 5.394 | 5.920 | 5.736 | 8.546 | 4.036 | 5.228 | 8.675 | 5.598 | |

| MAPE | 93.913 | 75.774 | 84.639 | 87.907 | 87.522 | 109.766 | 59.757 | 86.595 | 114.597 | 90.281 | |

| Accuracy | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.160 | 0.163 | 0.179 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.169 | 0.054 | 0.167 | |

| Precision | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.165 | 0.167 | 0.182 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.061 | 0.174 | |

| Recall | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.867 | 0.867 | 0.933 | 0.133 | 0.000 | 0.733 | 0.333 | 0.800 | |

| F1 score | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.277 | 0.280 | 0.304 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.289 | 0.103 | 0.286 | |

| #Param | 0.8M | 0.3M | 1.6M | 1.6M | 1.3M | 1.7M | 0.3M | 1.6M | 1.6M | 2.9M | |

| tune mode | d_model | MSE | MAE | #Param |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOTA Baseline PatchTST |

16 | 0.370 | 0.400 | 0.11M |

| full tune | / | 0.368 | 0.396 | 67.3M |

| FF | 16 | 0.373 | 0.401 | 0.27M |

| 32 | 0.369 | 0.400 | 0.53M | |

| 128 | 0.362 | 0.398 | 2.11M | |

| 512 | 0.399 | 0.421 | 8.41M | |

| FreqMLP | 2 | 0.362 | 0.399 | 0.05M |

| 4 | 0.354 | 0.394 | 0.09M | |

| 16 | 0.363 | 0.399 | 0.55M | |

| 32 | 0.369 | 0.402 | 1.08M | |

| FF+FreqMLP | 2 | 0.364 | 0.400 | 0.09M |

| 4 | 0.360 | 0.396 | 0.16M | |

| 8 | 0.359 | 0.396 | 0.29M | |

| 16 | 0.362 | 0.399 | 0.55M | |

| 32 | 0.362 | 0.401 | 1.08M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).