Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- V'kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(3):155-70. [CrossRef]

- Pasrija R, Naime M. The deregulated immune reaction and cytokines release storm (CRS) in COVID-19 disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90:107225. [CrossRef]

- Frieman M, Heise M, Baric R. SARS coronavirus and innate immunity. Virus Res. 2008;133(1):101-12. [CrossRef]

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783-801. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455(7213):674-8. [CrossRef]

- Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339(6121):786-91. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, Chen C, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339(6121):826-30. [CrossRef]

- Zhong B, Yang Y, Li S, Wang YY, Li Y, Diao F, et al. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity. 2008;29(4):538-50. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh T, Fujita N, Hayashi T, Takahara K, Satoh T, Lee H, et al. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(49):20842-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structures and Mechanisms in the cGAS-STING Innate Immunity Pathway. Immunity, 2020;53(1):43-53. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie C, Carozza JA, Li L. Biochemistry, Cell Biology, and Pathophysiology of the Innate Immune cGAS-cGAMP-STING Pathway. Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91:599-628. [CrossRef]

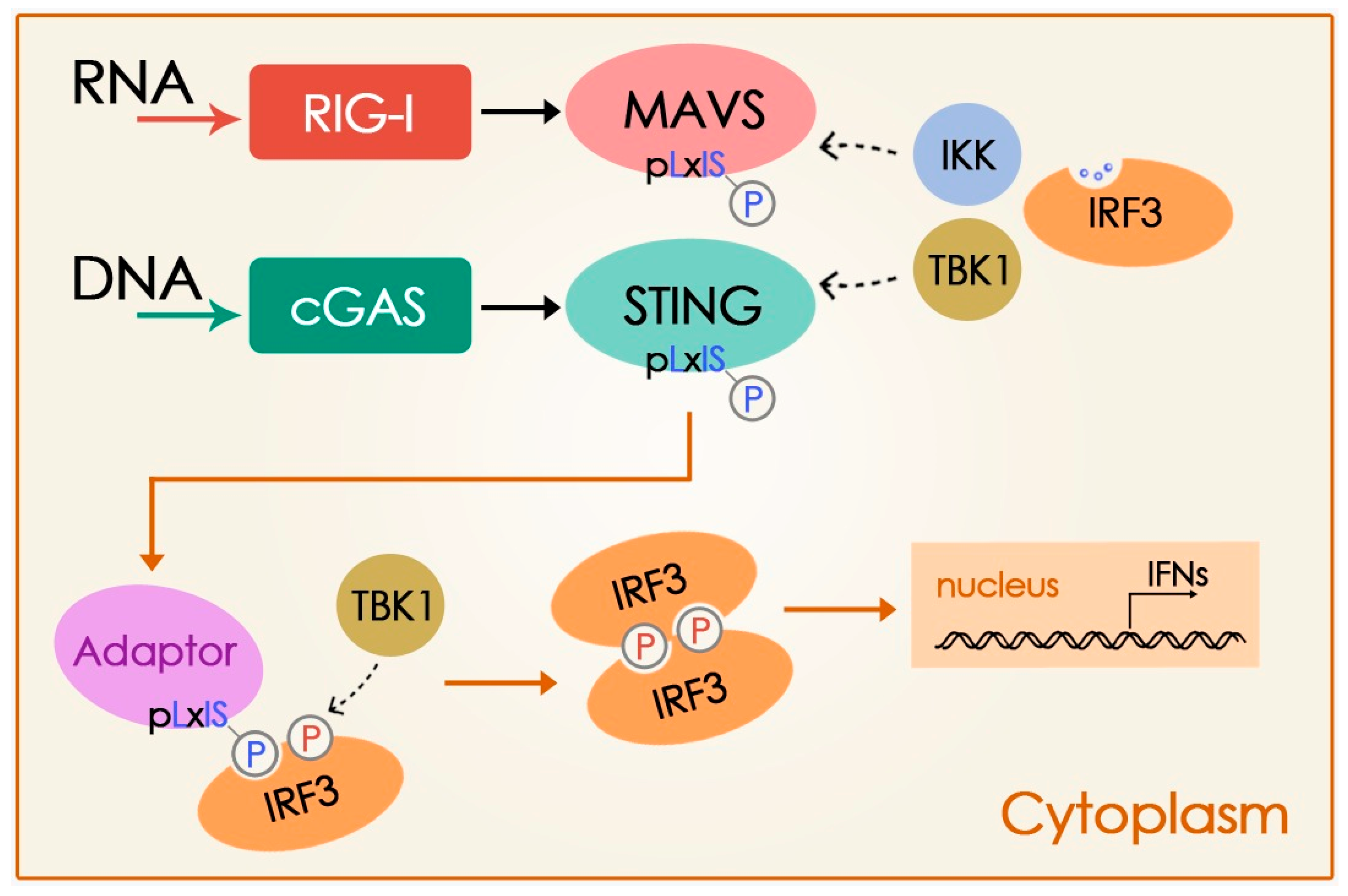

- Liu S, Cai X, Wu J, Cong Q, Chen X, Li T, et al. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science. 2015;347(6227):aaa2630. [CrossRef]

- Ablasser A, Chen ZJ. cGAS in action: Expanding roles in immunity and inflammation. Science. 2019;363(6431):eaat8657. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama M, Fujita T. RNA recognition and signal transduction by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunol Rev, 2009;227(1):54-65. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461(7265):788-92. [CrossRef]

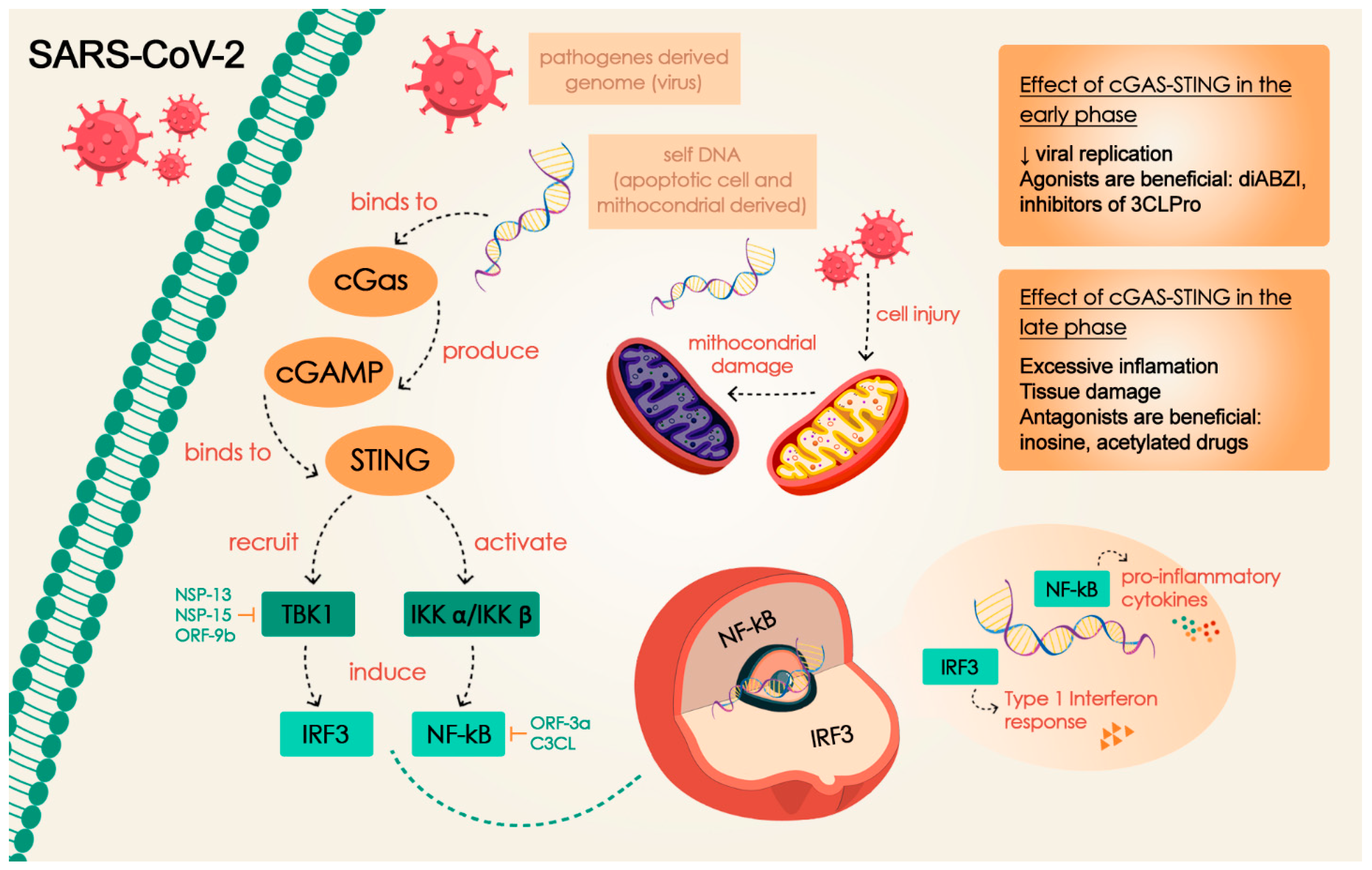

- Rui Y, Su J, Shen S, Hu Y, Huang D, Zheng W, et al. Unique and complementary suppression of cGAS-STING and RNA sensing- triggered innate immune responses by SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):123. [CrossRef]

- Han L, Zhuang MW, Deng J, Zheng Y, Zhang J, Nan ML, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF9b antagonizes type I and III interferons by targeting multiple components of the RIG-I/MDA-5-MAVS, TLR3-TRIF, and cGAS-STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol. 2021;93(9):5376-89. [CrossRef]

- Han L, Zheng Y, Deng J, Nan ML, Xiao Y, Zhuang MW, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 antagonizes STING-dependent interferon activation and autophagy. J Med Virol. 2022;94(11):5174-88. [CrossRef]

- Ma Z, Damania B. The cGAS-STING Defense Pathway and Its Counteraction by Viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):150-8. [CrossRef]

- Xiao R, Zhang A. Involvement of the STING signaling in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1006395. [CrossRef]

- Yang CA, Huang YL, Chiang BL. Innate immune response analysis in COVID-19 and kawasaki disease reveals MIS-C predictors. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(3):623-32. [CrossRef]

- Berthelot JM, Lioté F, Maugars Y, Sibilia J. Lymphocyte Changes in Severe COVID-19: Delayed Over-Activation of STING? Front Immunol. 2020;11:607069. [CrossRef]

- Carty M, Guy C, Bowie AG. Detection of Viral Infections by Innate Immunity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;183:114316. [CrossRef]

- Anwar S, Ul Islam K, Azmi MI, Iqbal J. cGAS-STING-mediated sensing pathways in DNA and RNA virus infections: crosstalk with other sensing pathways. Arch Virol. 2021;166(12):3255-68. [CrossRef]

- Copaescu A, Smibert O, Gibson A, Phillips EJ, Trubiano JA. The role of IL-6 and other mediators in the cytokine storm associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(3):518-34.e1. [CrossRef]

- Kirsch-Volders M, Fenech M. Inflammatory cytokine storms severity may be fueled by interactions of micronuclei and RNA viruses such as COVID-19 virus SARS-CoV-2. A hypothesis. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2021;788:108395. [CrossRef]

- Ji L, Wang Y, Zhou L, Lu J, Bao S, Shen Q, Wang X, Liu Y, Zhang W. E3 Ubiquitin Ligases: The Operators of the Ubiquitin Code That Regulates the RLR and cGAS-STING Pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14601. [CrossRef]

- de Moura Rodrigues D, Lacerda-Queiroz N, Couillin I, Riteau N. STING Targeting in Lung Diseases. Cells. 2022;11(21):3483. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudvand S, Shokri S. Interactions between SARS coronavirus 2 papain-like protease and immune system: A potential drug target for the treatment of COVID-19. Scand J Immunol. 2021;94(4):e13044. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Zhang M, Yuan C, Ma Z, Li W, Zhang Y, et al. Progress of cGAS-STING signaling in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1010911. [CrossRef]

- Mdkhana B, Saheb Sharif-Askari N, Ramakrishnan RK, Goel S, Hamid Q, Halwani R. Nucleic Acid-Sensing Pathways During SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Expectations versus Reality. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:199-216. [CrossRef]

- Yan S, Wu G. Spatial and temporal roles of SARS-CoV PLpro -A snapshot. FASEB J. 2021;35(1):e21197. [CrossRef]

- Colarusso C, Terlizzi M, Maglio A, Molino A, Candia C, Vitale C, et al. Activation of the AIM2 Receptor in Circulating Cells of Post-COVID-19 Patients With Signs of Lung Fibrosis Is Associated With the Release of IL-1α, IFN-α and TGF-β. Front Immunol. 2022;13:934264. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Yang C, Liu Y, Li T, Li H, Han J, et al. High Expression of HERV-K (HML-2) Might Stimulate Interferon in COVID-19 Patients. Viruses. 2022;14(5):996. [CrossRef]

- Jearanaiwitayakul T, Limthongkul J, Kaofai C, Apichirapokey S, Chawengkirttikul R, Sapsutthipas S, et al. The STING Ligand and Delivery System Synergistically Enhance the Immunogenicity of an Intranasal Spike SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidate. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5):1142. [CrossRef]

- Wang N, Li E, Deng H, Yue L, Zhou L, Su R, et al. Inosine: A broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory against SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced acute lung injury via suppressing TBK1 phosphorylation. J Pharm Anal. 2023;13(1):11-23. [CrossRef]

- Deng J, Zheng Y, Zheng SN, Nan ML, Han L, Zhang J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 NSP7 inhibits type I and III IFN production by targeting the RIG-I/MDA5, TRIF, and STING signaling pathways. J Med Virol. 2023;95(3):e28561. [CrossRef]

- Karlowitz R, Stanifer ML, Roedig J, Andrieux G, Bojkova D, Bechtel M, et al. USP22 controls type III interferon signaling and SARS-CoV-2 infection through activation of STING. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(8):684. [CrossRef]

- Lee JH, Kanwar B, Khattak A, Balentine J, Nguyen NH, Kast RE, et al. COVID-19 Molecular Pathophysiology: Acetylation of Repurposing Drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(21):13260. [CrossRef]

- Liu W, Reyes HM, Yang JF, Li Y, Stewart KM, Basil MC, et al. Activation of STING Signaling Pathway Effectively Blocks Human Coronavirus Infection. J Virol. 2021;95(12):e00490-21. [CrossRef]

- Ren H, Ma C, Peng H, Zhang B, Zhou L, Su Y, et al. Micronucleus production, activation of DNA damage response and cGAS-STING signaling in syncytia induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biol Direct. 2021;16(1):20. [CrossRef]

- Su J, Shen S, Hu Y, Chen S, Cheng L, Cai Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a inhibits cGAS-STING-mediated autophagy flux and antiviral function. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28175. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Zhang X, Lei X, Xiao X, Jiao T, Ma R, et al. Sensing of cytoplasmic chromatin by cGAS activates innate immune response in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):382. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, Zhang Y, Wang L, Yao X, Wu D, Cheng J, et al. Inhibition of coronavirus infection by a synthetic STING agonist in primary human airway system. Antiviral Res. 2021;187:105015. [CrossRef]

- Domizio JD, Gulen MF, Saidoune F, Thacker VV, Yatim A, Sharma K, et al. The cGAS-STING pathway drives type I IFN immunopathology in COVID-19. Nature. 2022;603(7899):145-51. [CrossRef]

- Barnett KC, Xie Y, Asakura T, Song D, Liang K, Taft-Benz SA, et al. An epithelial-immune circuit amplifies inflammasome and IL-6 responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(2):243-59.e6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Q, Liu S, Zhang CS, Wu Q, Yu X, Zhou R, et al. AMPK directly phosphorylates TBK1 to integrate glucose sensing into innate immunity. Mol Cell. 2022;82(23):4519-36.e7. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Ferretti M, Ying B, Descamps H, Lee E, Dittmar M, et al. Pharmacological activation of STING blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(59):eabi9007. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227(1):75-86. [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama M, Kikuchi M, Natsukawa T, Shinobu N, Imaizumi T, Miyagishi M, et al. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(7):730-7. [CrossRef]

- Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, et al. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478(7370):515-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Shi H, Wu J, Zhang X, Sun L, Chen C, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP containing mixed phosphodiester linkages is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for STING. Mol Cell. 2013;51(2):226-35. [CrossRef]

- Cai X, Chiu YH, Chen ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2014;54(2):289-96. [CrossRef]

- Neufeldt CJ, Cerikan B, Cortese M, Frankish J, Lee JY, Plociennikowska A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a pro-inflammatory cytokine response through cGAS-STING and NF-κB. Commun Biol. 2022;5(1):45. [CrossRef]

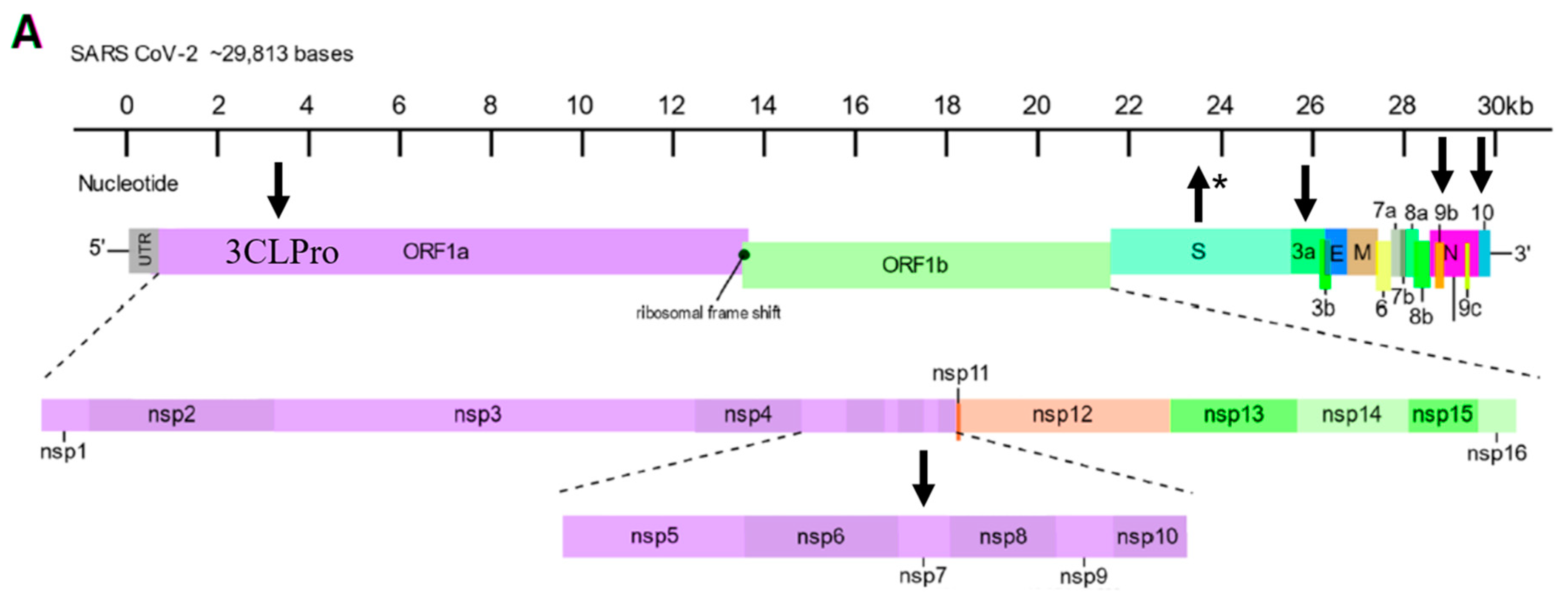

- Ellis P, Somogyvári F, Virok DP, Noseda M, McLean GR. Decoding Covid-19 with the SARS-CoV-2 Genome. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2021;9(1):1-12. [CrossRef]

- Elahi R, Hozhabri S, Moradi A, Siahmansouri A, Jahani Maleki A, Esmaeilzadeh A. Targeting the cGAS-STING pathway as an inflammatory crossroad in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2023;45(6):639-49. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).