Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Related Surveys

1.2. Key Contributions

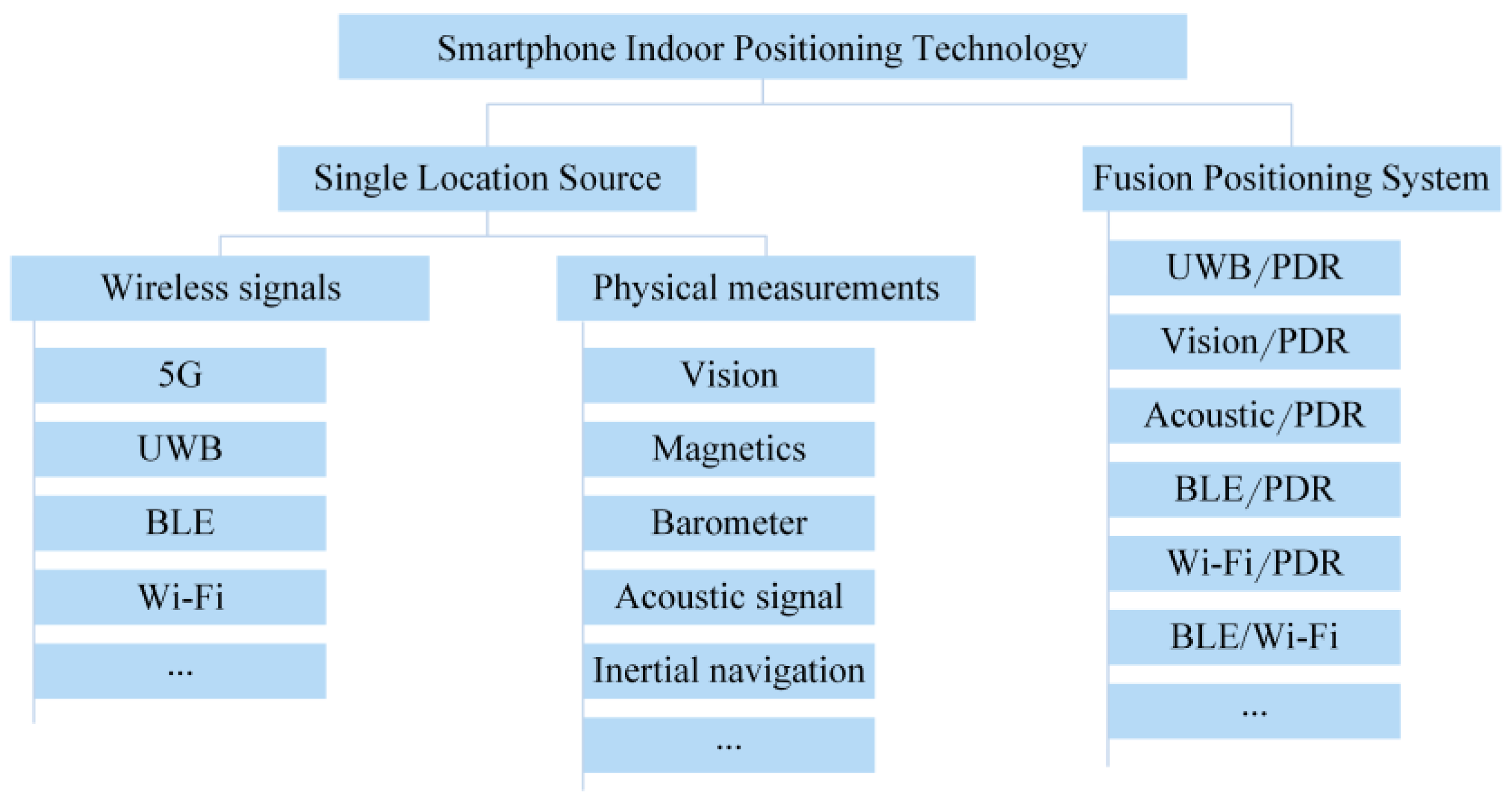

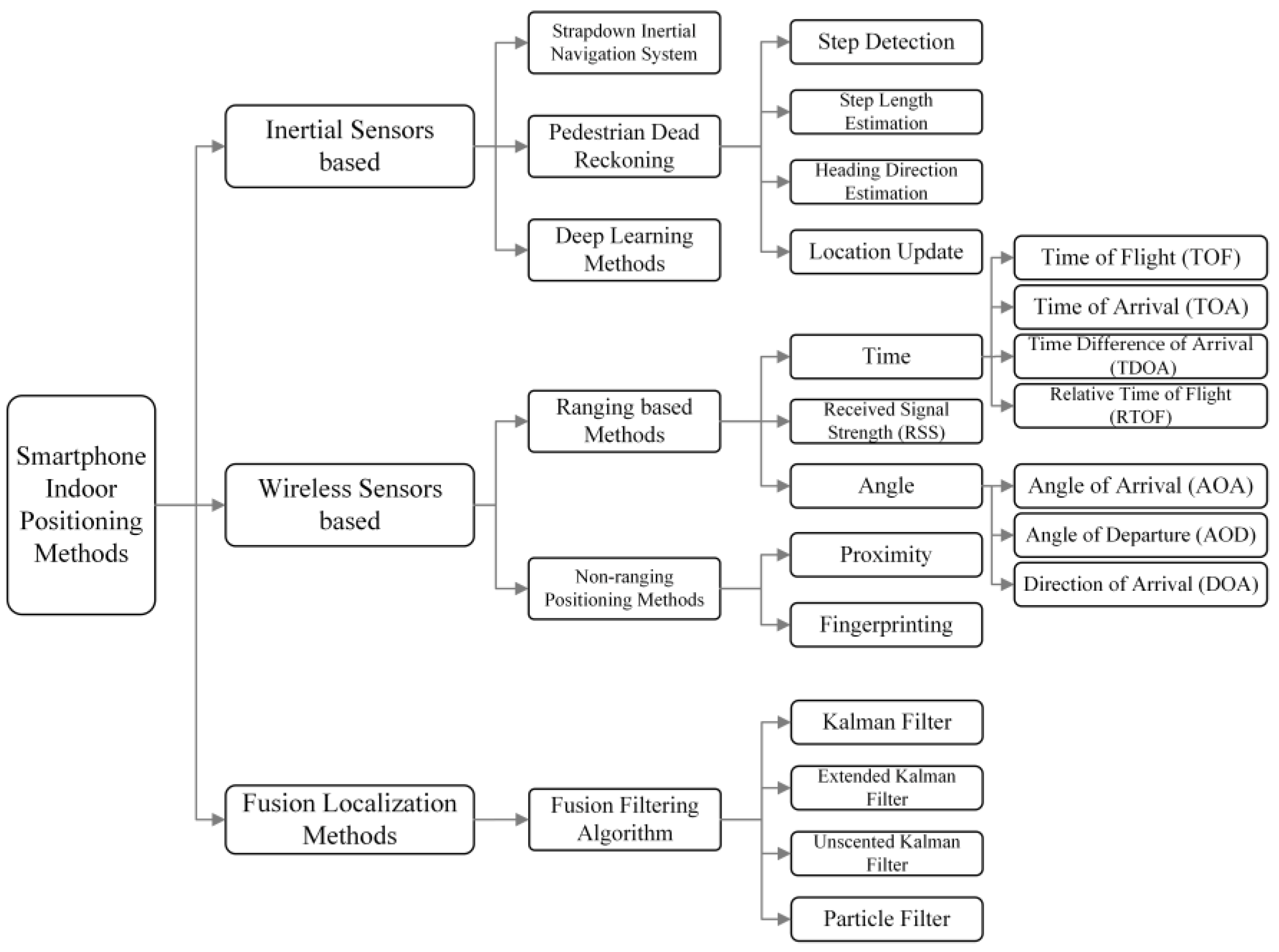

2. Smartphone Indoor Positioning Methods

2.1. Single Sensor-based Indoor Localization Method for Smartphone

2.1.1. Wi-Fi-based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.2. Bluetooth-based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.3. Inertial Sensors-Based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.3.1. Accelerometer

2.1.3.2. Gyroscope

2.1.3.3. Magnetometer

2.1.3.4. Inertial Sensor Fusion for Indoor Localization

2.1.4. Barometer-Based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.5. Vision-Based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.6. Acoustic Sensor-Based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.7. UWB-Based Indoor Localization Method

2.1.8. Challenges

- It is often difficult for a single sensor technology to provide continuous, high-precision localization services under all conditions. For example, Wi-Fi and BLE signals are highly affected by building structures, while visual or audio localization is susceptible to light conditions and noise levels.

- Poor stability of single sensors in localization, such as the error accumulation problem of inertial sensors and the localization errors caused by the non-visual distance and multipath effect problems of BLE and Wi-Fi.

- Deploying a high-density sensor network to achieve sufficient coverage and accuracy may increase the cost burden and implementation complexity, especially for indoor environments with large areas or complex structures.

- Indoor environments change frequently, such as crowd movement and the addition of temporary obstacles, and it is often difficult for a single sensor solution to adapt to these changes in real-time, which affects the localization results.

2.2. Fusion of Multi-Source Sensors for Indoor Localization of Smartphone

2.2.1. Fusion of Wi-Fi and Inertial Sensors for Indoor Localization

2.2.2. Fusion of BLE and Inertial Sensors for Indoor Localization

2.2.3. Fusion of Acoustic Signals and Inertial Sensors for Indoor Localization

2.2.4. Fusion of Vision and Inertial Sensors for Indoor Localization

2.2.5. Other Integration Methods

2.2.6. Challenges

- Existing multi-source fusion positioning solutions are usually optimized for a certain type of indoor scene or a specific user to achieve good positioning performance. However, the diversity of indoor environments introduces unique layouts, structures, and walking modes that can potentially impact the accuracy of indoor localization.

- Given the widespread use of Wi-Fi and BLE, a growing number of indoor positioning systems incorporate wireless positioning technologies alongside IMU integrated into smartphones. This approach offers extensive coverage and system capacity; however, its accuracy is susceptible to multipath interference and NLOS conditions.

- To improve indoor positioning accuracy, the existing methods are often realized by increasing the number of sensors, additional data and algorithm complexity, but this will also leads to higher implementation costs and operational and maintenance expenses for the system.

- Some fusion positioning systems, which lack inertial sensors, can utilize the complementary physical characteristics of wireless technologies to compensate for each other and serve as a class of indoor positioning solutions. However, these systems face challenges in acquiring velocity and attitude information similar to inertial sensors and may be influenced by low sampling rates.

3. Conclusions and Discussion

- Constructing building maps to constrain the indoor positioning of cell phones, constraining and matching the indoor positioning results by the a priori information of the building maps as well as the geometrical semantic and positional information contained in the building maps, so as to correct the coordinate information of the indoor positioning. In addition, accurate identification of the entrance location and floor identification of the building helps to construct a seamless indoor and outdoor localization system.

- Multipath and NLOS issues seriously affect the accuracy of wireless localization. Future work may focus on detecting and mitigating these problems in integrated systems. Implementing signal processing algorithms to identify and filter out multipath components, thereby improving the quality of received signals. Training machine learning models using historical datasets to recognize patterns indicative of multipath and NLOS conditions. These models can then predict and correct for such effects in real-time. Furthermore, multi-source sensors can aid in the detection of multipath and NLOS through environmental awareness or by cross-verifying measurement results.

- The deployment of additional facilities required in an indoor positioning system, such as wireless access points and BLE beacons, is also an important part of the system. The deployment location of these devices affects both the system implementation cost and positioning accuracy. By improving the wireless beacon location deployment algorithm to determine the optimal location for each beacon, the coverage of the wireless signals can be fully utilized. This reduces the number of wireless beacons needed, lowers the system cost, and reduces the measurement noise of the signals.

- The grip position of smartphones can introduce errors in the heading estimation in PDR systems. Therefore, when considering different smartphone headings, it is essential to account for changes in user behavioral states. Data from the smartphone's built-in accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer are used to train a machine learning model to detect different user behaviors, such as holding the phone in hand, in a pocket, or in a bag. This detection helps in adjusting the heading estimation accordingly. Another approach is to use context-aware algorithms to adjust heading estimates based on real-time user behavior and environment. In addition, an integrated framework combining traditional filtering algorithms and machine learning methods can effectively improve the accuracy of indoor localization systems and the recognition accuracy of motion states.

- AI Foundation model for indoor position and navigation is a forward-looking research field. For example, step length estimation is a major step in the PDR algorithm; however, due to variations in gender, body type, and height, among users, incorporating a big data artificial intelligence mechanism for adaptive adjustment of step length can be introduced to enhance the accuracy of indoor positioning.

- Some indoor localization methods are only oriented to a certain type of indoor scenes, but indoor environments are complex and varied, including rooms, corridors, halls, staircases, elevators, large arenas, warehouses, underground parking lots, and so on. The behavior of pedestrians is different in different indoor scenes, and the operation characteristics of the built-in sensors of smartphones are also different. Accurately identifying and sensing complex indoor scenes and optimizing their positioning weights for each sensor module in different scenes can help achieve high-precision indoor positioning in complex indoor environments. In addition, incorporating barometer data will improve the accuracy of floor recognition for developing a 3D indoor localization system.

- The fusion of different localization techniques through filtering algorithms is important to achieve optimal position estimates. Integration methods such as EKF, UKF, and PF are widely used to fuse position information from inertial sensors and ranging information from wireless signals. However, current filters often struggle to adapt dynamically to changing environments. Future work should focus on developing adaptive filtering techniques that can automatically adjust parameters based on real-time environmental changes. In addition, while these filtering algorithms offer good performance, they can be computationally intensive, especially in smartphones. Optimizing these algorithms for lower power consumption and faster processing is essential.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Imam-Fulani, Y.O.; Faruk, N.; Sowande, O.A.; Abdulkarim, A.; Alozie, E.; Usman, A.D.; Adewole, K.S.; Oloyede, A.A.; Chiroma, H.; Garba, S.; et al. 5G Frequency Standardization, Technologies, Channel Models, and Network Deployment: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Panja, A.K.; Karim, S.F.; Neogy, S.; Chowdhury, C. A novel feature based ensemble learning model for indoor localization of smartphone users. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 107. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Zhou B.D.; Ma W.; Xue W.X. Research process of GIS-aided indoor localization. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2019, 48, 1498-1506. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Li, Q.Q.; Fang, Z.X. A Visual-Based Approach for Indoor Radio Map Construction Using Smartphones. Sensors 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, I.; Hur, S.; Park, Y. Application of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and Smartphone Sensors for Indoor Localization. Applied Sciences-Basel 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; He, S.B.; Shu, Y.C.; Shi, Z.G. A Self-Evolving WiFi-based Indoor Navigation System Using Smartphones. Ieee Transactions on Mobile Computing 2020, 19, 1760-1774. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.Y.; Cheng, W.L.; Yang, N.; Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, J.J. Smartphone-Based 3D Indoor Pedestrian Positioning through Multi-Modal Data Fusion. Sensors 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Ciabattoni, L.; Foresi, G.; Monteriù, A.; Pepa, L.; Pagnotta, D.P.; Spalazzi, L.; Verdini, F. Real time indoor localization integrating a model based pedestrian dead reckoning on smartphone and BLE beacons. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2019, 10, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chen R.Z.; Guo G.Y.; Chen L.; Niu X.G. Application Status, Development and Future Trend of High-Precision Indoor Navigation and Tracking. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University 2023, 48, 1591-1600. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Chen, L.; Zheng, X.Y.; Wu, D.W.; Li, W.; Wu, Y. A Novel 3-D Indoor Localization Algorithm Based on BLE and Multiple Sensors. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 9359-9372. [CrossRef]

- Van der Ham, M.F.S.; Zlatanova, S.; Verbree, E.; Voûte, R. Real Time Localization Of Assets In Hospitals Using QUUPPA Indoor Positioning Technology. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2016, IV-4/W1, 105-110. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Ye, F.; Liu, Z.Y.; Xu, S.H.; Huang, L.X.; Li, Z.; Qian, L. A Robust Integration Platform of Wi-Fi RTT, RSS Signal, and MEMS-IMU for Locating Commercial Smartphone Indoors. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 16322-16331. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Niu, X.J.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X.G. Indoor Positioning Based on Pedestrian Dead Reckoning and Magnetic Field Matching for Smartphones. Sensors 2018, 18. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.F.; Deng, Y.; Guo, C.; Qi, S.F.; Wang, J.R. Performance improvement of 5G positioning utilizing multi-antenna angle measurements. Satellite Navigation 2022, 3. [CrossRef]

- Girard, G.; Côté, S.; Zlatanova, S.; Barette, Y.; St-Pierre, J.; Van Oosterom, P. Indoor Pedestrian Navigation Using Foot-Mounted IMU and Portable Ultrasound Range Sensors. Sensors 2011, 11, 7606-7624. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Ye, F.; Guo, G.Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, L. Improved TOA Estimation Method for Acoustic Ranging in a Reverberant Environment. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 4844-4852. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.B.; Li, Z.H.; Yuan, S.W.; Zhu, S.H. IMU/UWB Fusion Method Using a Complementary Filter and a Kalman Filter for Hybrid Upper Limb Motion Estimation. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, E.B.; Li, B.H.; Diakite, A.; Zhao, K.; Oliver, N.; Bednarz, T.; Zlatanova, S. Visually Impaired User Experience using a 3D-Enhanced Facility Management System for Indoors Navigation. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2020 International Conference on Multimodal Interaction, Virtual Event, Netherlands, 2021; pp. 92–96.

- Sun, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Huai, J.Z.; Hua, L.C.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, R.Z. RSS-Based Visible Light Positioning Using Nonlinear Optimization. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 14137-14150. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.; Rocha, H.; Ribeiro, A.; Lobo, F. INEXT: A Computer System for Indoor Object Location using RFID. Anais Estendidos do Simpósio Brasileiro de Engenharia de Sistemas Computacionais (SBESC); 2023: Anais Estendidos do XIII Simpósio Brasileiro de Engenharia de Sistemas Computacionais 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cai, Y.X.; He, D.J.; Lin, J.R.; Zhang, F. FAST-LIO2: Fast Direct LiDAR-Inertial Odometry. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2022, 38, 2053-2073. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; El-Sheimy, N. Tightly-Coupled Integration of WiFi and MEMS Sensors on Handheld Devices for Indoor Pedestrian Navigation. IEEE Sensors Journal 2016, 16, 224-234. [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.D.; Wu, H. Indoor dynamic positioning system based on strapdown inertial navigation technology. In Proceedings of the Proc.SPIE, 2011; p. 820115.

- Liu, T.; Niu, X.J.; Kuang, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. Doppler Shift Mitigation in Acoustic Positioning Based on Pedestrian Dead Reckoning for Smartphone. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.J.; Lee, J.B.; Zlatanova, S.; Diakité, A.A.; Kim, H. Navigation network derivation for QR code-based indoor pedestrian path planning. Transactions in GIS 2022, 26, 1240-1255. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.L.; Liu, L.; Zlatanova, S.; Penard, W.; Xiong, Q. A pedestrian tracking algorithm using grid-based indoor model. Automation in Construction 2018, 92, 173-187. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.W.; Jiang, C.H.; Jia, J.X.; Bo, Y.M.; Zhu, B.; Dai, H.J.; Hyyppä, J. An APDR/UPV/Light Multisensor-Based Indoor Positioning Method via Factor Graph Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Morar, A.; Moldoveanu, A.; Mocanu, I.; Moldoveanu, F.; Radoi, I.E.; Asavei, V.; Gradinaru, A.; Butean, A. A Comprehensive Survey of Indoor Localization Methods Based on Computer Vision. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kunhoth, J.; Karkar, A.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Al-Ali, A. Indoor positioning and wayfinding systems: a survey. Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences 2020, 10, 18. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.N.; Cheng, L.S.; Qian, K.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.H. Indoor acoustic localization: a survey. Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences 2020, 10, 2. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.S.; Ansari, N.; Hu, F.Z.; Shao, Y.; Elikplim, N.R.; Li, L. A Survey on Fusion-Based Indoor Positioning. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 566-594. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, H.B.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Wireless Sensing for Human Activity: A Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2020, 22, 1629-1645. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, I.; Hur, S.; Park, Y. Smartphone Sensor Based Indoor Positioning: Current Status, Opportunities, and Future Challenges. Electronics 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Simões, W.C.S.S.; Machado, G.S.; Sales, A.M.A.; de Lucena, M.M.; Jazdi, N.; de Lucena, V.F. A Review of Technologies and Techniques for Indoor Navigation Systems for the Visually Impaired. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Pascacio, P.; Casteleyn, S.; Torres-Sospedra, J.; Lohan, E.S.; Nurmi, J. Collaborative Indoor Positioning Systems: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, H.; Shuaieb, W.; Obeidat, O.; Abd-Alhameed, R. A Review of Indoor Localization Techniques and Wireless Technologies. Wireless Personal Communications 2021, 119, 289-327. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.Y.; Bergmann, J. Pedestrian Dead Reckoning With Wearable Sensors: A Systematic Review. Ieee Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 143-152. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, G.L.; Abed-Meraim, K. A Survey of Magnetic-Field-Based Indoor Localization. Electronics 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.; Álvarez, F.J.; Á, H.; Holm, S. A Survey on Acoustic Positioning Systems for Location-Based Services. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Fu, M.X.; Wang, J.Q.; Luo, H.Y.; Sun, L.; Ma, Z.C.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.Y.; Huang, R.; Li, X.D.; et al. Recent Advances in Pedestrian Inertial Navigation Based on Smartphone: A Review. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 22319-22343. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Pan, X.F. Deep Learning for Inertial Positioning: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2024, 25, 10506-10523. [CrossRef]

- Naser, R.S.; Lam, M.C.; Qamar, F.; Zaidan, B.B. Smartphone-Based Indoor Localization Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Huai, J.Z.; Hua, L.C.; Yang, X.S.; Cao, X.X.; Zhang, P.; Cao, Y.; Qi, L.N.; et al. Multi-sensor integrated navigation/positioning systems using data fusion: From analytics-based to learning-based approaches. Information Fusion 2023, 95, 62-90. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Huai, J.Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.Z. Bluetooth Localization Technology: Principles, Applications, and Future Trends. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2022, 9, 23506-23524. [CrossRef]

- Leitch, S.G.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Abbas, W.B.; Hafeez, M.; Laziridis, P.I.; Sureephong, P.; Alade, T. On Indoor Localization Using WiFi, BLE, UWB, and IMU Technologies. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kargar-Barzi, A.; Farahmand, E.; Chatrudi, N.T.; Mahani, A.; Shafique, M. An Edge-Based WiFi Fingerprinting Indoor Localization Using Convolutional Neural Network and Convolutional Auto-Encoder. Ieee Access 2024, 12, 85050-85060. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yan, R.e.; Zhao, L. An extreme value based algorithm for improving the accuracy of WiFi localization. Ad Hoc Networks 2023, 143, 103131. [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, S. Fingerprint Augment Based on Super-Resolution for WiFi Fingerprint Based Indoor Localization. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 12152-12162. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Shang, S.; Wu, Z.N. Research on Indoor 3D Positioning Algorithm Based on WiFi Fingerprint. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, H.; Taleai, M.; Zlatanova, S. NSGA-II based optimal Wi-Fi access point placement for indoor positioning: A BIM-based RSS prediction. Automation in Construction 2023, 152, 104897. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Gao, L.J.; Mao, S.W.; Pandey, S. CSI-Based Fingerprinting for Indoor Localization: A Deep Learning Approach. Ieee Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2017, 66, 763-776. [CrossRef]

- Amri, S.; Khelifi, F.; Bradai, A.; Rachedi, A.; Kaddachi, M.L.; Atri, M. A new fuzzy logic based node localization mechanism for Wireless Sensor Networks. Future Generation Computer Systems-the International Journal of Escience 2019, 93, 799-813. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Yu, B.G.; Li, H.S.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Zhu, R.H.; Li, Y.N. HPIPS: A High-Precision Indoor Pedestrian Positioning System Fusing WiFi-RTT, MEMS, and Map Information. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Guo, G.Y.; Ye, F.; Chen, L. Wi-Fi Fine Time Measurement: Data Analysis and Processing for Indoor Localisation. Journal of Navigation 2020, 73, 1106-1128. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.C.; Wu, H.T. Framework and Methods of State Monitoring-Based Positioning System on WIFI-RTT Clock Drift Theory. Ieee Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems 2024, 60, 685-697. [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, R.; Joshi, R.B.; Mishra, S. IndoorGNN: A Graph Neural Network Based Approach for Indoor Localization Using WiFi RSSI. In Proceedings of the Big Data and Artificial Intelligence, Cham, 2023//, 2023; pp. 150-165.

- Pan, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Q. Indoor positioning fingerprint database construction based on CSA-DBSCAN and RCVAE-GAN. Physica Scripta 2024, 99. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.J.; Wang, Y.J.; Bi, J.X.; Zhang, Y.S.; Yao, G.B.; Feng, Y.G.; Si, M.H. LOS compensation and trusted NLOS recognition assisted WiFi RTT indoor positioning algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 243. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Nguyen, K.A.; Luo, Z. A Wi-Fi RSS-RTT Indoor Positioning Model Based on Dynamic Model Switching Algorithm. IEEE Journal of Indoor and Seamless Positioning and Navigation 2024, 2, 151-165. [CrossRef]

- Junoh, S.A.; Pyun, J.Y. Enhancing Indoor Localization With Semi-Crowdsourced Fingerprinting and GAN-Based Data Augmentation. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 11945-11959. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yin, F.; Gunnarsson, F.; Amirijoo, M.; Özkan, E.; Gustafsson, F. Particle filtering for positioning based on proximity reports. In Proceedings of the 2015 18th International Conference on Information Fusion (Fusion), 6-9 July 2015, 2015; pp. 1046-1052.

- Huang, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, W. A Performance Evaluation Framework for Direction Finding Using BLE AoA/AoD Receivers. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 3331-3345. [CrossRef]

- Gentner, C.; Hager, P.; Ulmschneider, M. Server based Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Positioning using Received Signal Strength (RSS) Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2023 13th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), 25-28 Sept. 2023, 2023; pp. 1-7.

- Shin, B.; Ho Lee, J.; Lee, T. Novel indoor fingerprinting method based on RSS sequence matching. Measurement 2023, 223, 113719. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.S.; Hu, S.C.; Kang, K.; Qian, H. An Improved AoA Estimation Algorithm for BLE System in the Presence of Phase Noise. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2023, 69, 400-407. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q.; Wu, T.; Zhang, K.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Cheng, K.; Liu, J.H.; Zhu, J. A high precision indoor positioning system of BLE AOA based on ISSS algorithm. Measurement 2024, 224, 113801. [CrossRef]

- Spachos, P.; Plataniotis, K.N. BLE Beacons for Indoor Positioning at an Interactive IoT-Based Smart Museum. IEEE Systems Journal 2020, 14, 3483-3493. [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Wu, C. Hybrid Indoor Positioning System for Pedestrians With Swinging Arms Based on Smartphone IMU and RSSI of BLE. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.Z. Intelligent Fusion Structure for Wi-Fi/BLE/QR/MEMS Sensor-Based Indoor Localization. Remote Sensing 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Assayag, Y.; Oliveira, H.; Souto, E.; Barreto, R.; Pazzi, R. Adaptive Path Loss Model for BLE Indoor Positioning System. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 12898-12907. [CrossRef]

- Safwat, R.; Shaaban, E.; Al-Tabbakh, S.M.; Emara, K. Fingerprint-based indoor positioning system using BLE: real deployment study. Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics; Vol 12, No 1: February 2023DO - 10.11591/eei.v12i1.3798 2023.

- Wu, Z.T.; Ma, X.P.; Li, J.Y.; Wang, R.J.; Chen, F. Design of Indoor Navigation Scheme Based on Bluetooth Low Energy. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technologies for Rail Transportation (EITRT) 2023, Singapore, 2024//, 2024; pp. 561-569.

- Wang, B.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Yu, B.G.; Jia, R.C.; Huang, L. Posture Recognition and Heading Estimation Based on Machine Learning Using MEMS Sensors. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence for Communications and Networks, Cham, 2019//, 2019; pp. 496-508.

- Ignatov, A. Real-time human activity recognition from accelerometer data using Convolutional Neural Networks. Applied Soft Computing 2018, 62, 915-922. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.s.; Kong, Y.; Nam, Y.; Yim, K. An Indoor Positioning System Using Bluetooth RSSI with an Accelerometer and a Barometer on a Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2015 10th International Conference on Broadband and Wireless Computing, Communication and Applications (BWCCA), 4-6 Nov. 2015, 2015; pp. 528-531.

- Lee, K.; Nam, Y.; Min, S.D. An indoor localization solution using Bluetooth RSSI and multiple sensors on a smartphone. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2018, 77, 12635-12654. [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Chen, R.Z.; Guo, G.Y.; Chen, L. Locating Smartphone Indoors by Using Tightly Coupling Bluetooth Ranging and Accelerometer Measurements. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Z.X.; Xiao, Z.L.; Zhou, J. A High-Precision and Low-Cost IMU-Based Indoor Pedestrian Positioning Technique. Ieee Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 6716-6726. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.P. Indoor PDR Trajectory Matching by Gyroscope and Accelerometer Signal Sequence Without Initial Motion State. Ieee Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 15128-15139. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, I.; Hur, S.; Park, Y. Enhancing Performance of Magnetic Field Based Indoor Localization Using Magnetic Patterns from Multiple Smartphones. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Li, T.Y.; Niu, X.J. Magnetometer Bias Insensitive Magnetic Field Matching Based on Pedestrian Dead Reckoning for Smartphone Indoor Positioning. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 4790-4799. [CrossRef]

- Friad Qadr, R.; Maghdid, H.S.; Sabir, A.T. Novel Integration of Wi-Fi Signal and Magnetometer Sensor Measurements in Fingerprinting Technique for Indoors Smartphone positioning. ITM Web Conf. 2022, 42.

- Zhao, H.Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Qiu, S.; Wang, Z.L.; Yang, N.; Xu, J. Pedestrian Dead Reckoning Using Pocket-Worn Smartphone. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 91063-91073. [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Han, Y. SmartPDR: Smartphone-Based Pedestrian Dead Reckoning for Indoor Localization. IEEE Sensors Journal 2015, 15, 2906-2916. [CrossRef]

- Mekruksavanich, S.; Jantawong, P.; Jitpattanakul, A. Deep Learning-based Action Recognition for Pedestrian Indoor Localization using Smartphone Inertial Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2022 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), 26-28 Jan. 2022, 2022; pp. 346-349.

- Casado, F.E.; Rodríguez, G.; Iglesias, R.; Regueiro, C.V.; Barro, S.; Canedo-Rodríguez, A. Walking Recognition in Mobile Devices. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, S.; Haas, H. Pedestrian dead reckoning: A basis for personal positioning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Positioning, Navigation and Communication, 2006; pp. 27-35.

- Gu, F.Q.; Khoshelham, K.; Yu, C.Y.; Shang, J.G. Accurate Step Length Estimation for Pedestrian Dead Reckoning Localization Using Stacked Autoencoders. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2019, 68, 2705-2713. [CrossRef]

- Poulose, A.; Eyobu, O.S.; Han, D.S. An Indoor Position-Estimation Algorithm Using Smartphone IMU Sensor Data. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 11165-11177. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.L.; Meng, X.L.; Wang, Y.J.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Tian, P.; Yang, H.C. Integrated WiFi/PDR/Smartphone Using an Unscented Kalman Filter Algorithm for 3D Indoor Localization. Sensors 2015, 15, 24595-24614. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, H.B.; Du, Q.X.; Tang, S.M. A Pedestrian Dead-Reckoning System for Walking and Marking Time Mixed Movement Using an SHSs Scheme and a Foot-Mounted IMU. Ieee Sensors Journal 2019, 19, 1661-1671. [CrossRef]

- Renaudin, V.; Combettes, C.; Peyret, F. Quaternion based heading estimation with handheld MEMS in indoor environments. In Proceedings of the Position, Location & Navigation Symposium-plans, IEEE/ION, 2014.

- Liu, J.B.; Chen, R.Z.; Pei, L.; Guinness, R.; Kuusniemi, H. A Hybrid Smartphone Indoor Positioning Solution for Mobile LBS. Sensors 2012, 12, 17208-17233. [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Solaz, Y.; Ohayon, G. Pedestrian Dead Reckoning With Smartphone Mode Recognition. Ieee Sensors Journal 2018, 18, 7577-7584. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Ye, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.J.; Liu, M.Y.; Cao, Z.P. A Pose Awareness Solution for Estimating Pedestrian Walking Speed. Remote Sensing 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.X.; Zhan, X.Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.Z.; Yuan, W.H. Heading Estimation for Multimode Pedestrian Dead Reckoning. Ieee Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 8731-8739. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.B.; Pan, L.; Fen, W.; Xu, X.R.; Liang, X.S.; Xu, X. A Robust Step Detection and Stride Length Estimation for Pedestrian Dead Reckoning Using a Smartphone. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 9685-9697. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Guo, J.X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, R.; Wang, L.P. An Indoor Localization Method Based on the Combination of Indoor Map Information and Inertial Navigation with Cascade Filter. Journal of Sensors 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.X.; Jiang, Z.H. An improved pedestrian dead reckoning algorithm based on smartphone built-in MEMS sensors. Aeu-International Journal of Electronics and Communications 2023, 168. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Guo, S.L.; Han, L.; Baris, C.A. Indoor positioning method for pedestrian dead reckoning based on multi-source sensors. Measurement 2024, 229. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.G.; Gao, Z.Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, Q.Z.; Yang, C. Reliable Positioning Model of Smartphone Sensors and User Motions Tightly Enhanced PDR. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.T.; Xie, Y.X.; Zhou, Z.H.; He, Y.Y.; Wang, Q.L.; Chen, Z.M. An Indoor 3D Positioning Method Using Terrain Feature Matching for PDR Error Calibration. Electronics 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, K.; Khan, A.J.; Misra, A.; Balan, R.K.; Agarwal, S. Barometric phone sensors: more hype than hope! In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th Workshop on Mobile Computing Systems and Applications, Santa Barbara, California, 2014; p. Article 12.

- Yu, M.; Xue, F.; Ruan, C.; Guo, H. Floor positioning method indoors with smartphone's barometer. Geo-Spatial Information Science 2019, 22, 138-148. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Y.; Wei, J.M.; Zhu, J.X.; Yang, W.J. A robust floor localization method using inertial and barometer measurements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Indoor Positioning & Indoor Navigation, 2017.

- Elbakly, R.; Elhamshary, M.; Youssef, M. HyRise: A robust and ubiquitous multi-sensor fusion-based floor localization system. Proceedings of the ACM on interactive, mobile, wearable and ubiquitous technologies 2018, 2, 1-23.

- Li, M.; Chen, R.Z.; Liao, X.; Guo, B.X.; Zhang, W.L.; Guo, G. A Precise Indoor Visual Positioning Approach Using a Built Image Feature Database and Single User Image from Smartphone Cameras. Remote Sensing 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Y.W.; Zhu, J.L.; Jiang, C.H.; Jia, J.X.; Bo, Y.M.; Liu, X.Z.; Dai, H.J.; Puttonen, E.; Hyyppä, J. An Up-View Visual-Based Indoor Positioning Method via Deep Learning. Remote Sensing 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.R.; Chen, R.Z.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.J.; Wu, D.W. An Indoor Positioning System Based on Static Objects in Large Indoor Scenes by Using Smartphone Cameras. Sensors 2018, 18. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. Ultra-High-Accuracy Visual Marker for Indoor Precise Positioning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 31 May-31 Aug. 2020, 2020; pp. 2338-2343.

- Kubícková, H.; Jedlicka, K.; Fiala, R.; Beran, D. Indoor Positioning Using PnP Problem on Mobile Phone Images. Isprs International Journal of Geo-Information 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, B.G.; Jin, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X.H. Image-Based Indoor Localization Using Smartphone Camera. Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.W.; Jeong, C.S.; Kwon, S.C.; Jung, K.D. Point-Graph Neural Network Based Novel Visual Positioning System for Indoor Navigation. Applied Sciences-Basel 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.X.; Ou, B.J.; Wang, R.C.; Yu, H.A.; Yu, J.H.; Hu, Y.X. A Robust Indoor Localization Method Based on DAT-SLAM and Template Matching Visual Odometry. Ieee Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 8789-8796. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Ye, F.; Guo, G.Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, L. Time-of-arrival estimation for smartphones based on built-in microphone sensor. Electronics Letters 2020, 56, 1280-1282. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.H.; Chen, R.Z.; Guo, G.Y.; Huang, L.X.; Li, Z.; Qian, L.; Ye, F.; Chen, L. An Audio Fingerprinting Based Indoor Localization System: From Audio to Image. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 20154-20166. [CrossRef]

- Priyantha, N.B.; Chakraborty, A.; Balakrishnan, H. The cricket location-support system. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 6th annual international conference on Mobile computing and networking, 2000; pp. 32-43.

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.H.; Cao, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Acoustic Indoor Localization System Integrating TDMA+FDMA Transmission Scheme and Positioning Correction Technique. Sensors 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, M.L.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, Z. TOA Estimation of Chirp Signal in Dense Multipath Environment for Low-Cost Acoustic Ranging. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2019, 68, 355-367. [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X. Effective Audio Signal Arrival Time Detection Algorithm for Realization of Robust Acoustic Indoor Positioning. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2020, 69, 7341-7352. [CrossRef]

- Bordoy, J.; Schott, D.J.; Xie, J.Z.; Bannoura, A.; Klein, P.; Striet, L.; Hoeflinger, F.; Haering, I.; Reindl, L.; Schindelhauer, C. Acoustic Indoor Localization Augmentation by Self-Calibration and Machine Learning. Sensors 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Chen, R.Z.; Xu, S.A.; Liu, Z.Y.; Guo, G.Y.; Chen, L. A Novel Method Locating Pedestrian With Smartphone Indoors Using Acoustic Fingerprints. Ieee Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 27887-27896. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Wu, J. Acoustic TDOA Measurement and Accurate Indoor Positioning for Smartphone. Future Internet 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, R.Z.; Guo, G.Y.; Ye, F.; Qian, L.; Xu, S.H.; Huang, L.X.; Chen, L. Dual-Step Acoustic Chirp Signals Detection Using Pervasive Smartphones in Multipath and NLOS Indoor Environments. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 6494-6507. [CrossRef]

- Yogesh, V.; Buurke, J.H.; Veltink, P.H.; Baten, C.T.M. Integrated UWB/MIMU Sensor System for Position Estimation towards an Accurate Analysis of Human Movement: A Technical Review. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Kok, M.; Hol, J.D.; Schön, T.B. Indoor Positioning Using Ultrawideband and Inertial Measurements. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2015, 64, 1293-1303. [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.W.; Yu, Y.H. Indoor position system based on improved TDOA algorithm. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2019; p. 012075.

- Monfared, S.; Copa, E.I.P.; De Doncker, P.; Horlin, F. AoA-Based Iterative Positioning of IoT Sensors With Anchor Selection in NLOS Environments. Ieee Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2021, 70, 6211-6216. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.H.; Zhao, K.; Sandoval, E.B. A UWB-Based Indoor Positioning System Employing Neural Networks. Journal of Geovisualization and Spatial Analysis 2020, 4, 18. [CrossRef]

- Leitinger, E.; Fröhle, M.; Meissner, P.; Witrisal, K. Multipath-assisted maximum-likelihood indoor positioning using UWB signals. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC), 10-14 June 2014, 2014; pp. 170-175.

- Bottigliero, S.; Milanesio, D.; Saccani, M.; Maggiora, R. A Low-Cost Indoor Real-Time Locating System Based on TDOA Estimation of UWB Pulse Sequences. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.M.; Lin, R.H.; Zhu, H.L.; Lin, Y.H.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, L.H.; Gao, Y.L.; Zhuang, J.B.; Hu, H.Q.; Lu, Y.J.; et al. UWB-based AOA Indoor Position-Tracking System and Data Processing Algorithm. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.-M.-S.; Yeo, B.-C.; Lim, W.-S. Integration of UWB RSS to Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting-based indoor positioning system. Cogent Engineering 2022, 9, 2087364. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.K.K.; El-Gamal, M.N. Ultra-wideband (UWB) communications systems: an overview. In Proceedings of the The 3rd International IEEE-NEWCAS Conference, 2005., 22-22 June 2005, 2005; pp. 381-386.

- Djosic, S.; Stojanovic, I.; Jovanovic, M.; Nikolic, T.; Djordjevic, G.L. Fingerprinting-assisted UWB-based localization technique for complex indoor environments. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 167, 114188. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, J.; He, L.Y. TOA and DOA Estimation for IR-UWB Signals: An Efficient Algorithm by Improved Root-MUSIC. Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.L.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhao, G.F. Joint TOA and DOA Estimation for UWB Systems with Antenna Array via Doubled Frequency Sample Points and Extended Number of Clusters. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.K.; Lu, M.; Zheng, Y.F.; Fang, T.Y. System and Method for Reducing NLOS Errors in UWB Indoor Positioning. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, Y.J.; Xu, S.L.; Qi, H.X.; Hu, X.X. Indoor Positioning Tightly Coupled Wi-Fi FTM Ranging and PDR Based on the Extended Kalman Filter for Smartphones. Ieee Access 2020, 8, 49671-49684. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, B.D.; Huang, P.P.; Xue, W.X.; Li, Q.Q.; Zhu, J.S.; Qiu, L. Kalman Filter-Based Data Fusion of Wi-Fi RTT and PDR for Indoor Localization. Ieee Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 8479-8490. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Choi, Y.S. Calibration-Free Positioning Technique Using Wi-Fi Ranging and Built-In Sensors of Mobile Devices. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 541-554. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, H.; Gravina, R.; Sun, F.M. WIO-EKF: Extended Kalman Filtering-Based Wi-Fi and Inertial Odometry Fusion Method for Indoor Localization. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 23592-23603. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.H.; Chen, R.Z.; Yu, Y.; Guo, G.Y.; Huang, L.X. Locating Smartphones Indoors Using Built-In Sensors and Wi-Fi Ranging With an Enhanced Particle Filter. Ieee Access 2019, 7, 95140-95153. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Song, S.J.; Liu, Z.H. A PDR/WiFi Indoor Navigation Algorithm Using the Federated Particle Filter. Electronics 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yang, J.F.; Fang, X.; Jiang, H.; Xie, L.H. Fusion of WiFi and IMU Using Swarm Optimization for Indoor Localization. In Machine Learning for Indoor Localization and Navigation, Tiku, S., Pasricha, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 133-157.

- Lin, Y.R.; Yu, K.G. An Improved Integrated Indoor Positioning Algorithm Based on PDR and Wi-Fi under Map Constraints. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Fu, W.J.; Li, W.; Zhou, H.T.; Guo, G.Y. Indoor positioning based on tightly coupling of PDR and one single Wi-Fi FTM AP. Geo-Spatial Information Science 2023, 26, 480-495. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Huang, B.Q.; Xu, Z.D.; Yang, R.Z. A Fuzzy Logic-Based Energy-Adaptive Localization Scheme by Fusing WiFi and PDR. Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Niu, X.G.; Yan, K.; Xu, S.H.; Chen, L. Factor Graph Framework for Smartphone Indoor Localization: Integrating Data-Driven PDR and Wi-Fi RTT/RSS Ranging. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 12346-12354. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.D.; Huang, B.Q.; Jia, B.; Mao, G.Q. Enhancing WiFi Fingerprinting Localization Through a Co-Teaching Approach Using Crowdsourced Sequential RSS and IMU Data. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2024, 11, 3550-3562. [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.M.T.; Duong, N.S.; Sandrasegaran, K. Smartphone-Based Indoor Positioning Using BLE iBeacon and Reliable Lightweight Fingerprint Map. Ieee Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 10283-10294. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Zhou, B.D.; Bao, S.Q.; Liu, X.; Gu, Z.N.; Li, L.C.; Zhao, Y.P.; Zhu, J.S.; Li, Q.Q. A Data-Driven Inertial Navigation/Bluetooth Fusion Algorithm for Indoor Localization. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 5288-5301. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.Y.; Yang, B.; Long, Z.Q.; Dai, C.H. A Method of Indoor Positioning by Signal Fitting and PDDA Algorithm Using BLE AOA Device. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 7877-7887. [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Li, Y.J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.F.; Cheng, Z. Real-Time Indoor Positioning Based on BLE Beacons and Pedestrian Dead Reckoning for Smartphones. Applied Sciences-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Yan, K.; Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, R.Z. Virtual Wireless Device-Constrained Robust Extended Kalman Filters for Smartphone Positioning in Indoor Corridor Environment. Ieee Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 2815-2822. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Yan, K.; Li, P.Z.; Yuan, L.; Chen, L. Multichannel and Multi-RSS Based BLE Range Estimation for Indoor Tracking of Commercial Smartphones. Ieee Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 30728-30738. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.H.; Zeng, B.S.; Li, S.N.; Zlatanova, S.; Yang, Z.J.; Bai, M.C.; Yu, B.; Wen, D.Q. MLA-MFL: A Smartphone Indoor Localization Method for Fusing Multisource Sensors Under Multiple Scene Conditions. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 26320-26333. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Luo, X.N.; Zhong, Y.R.; Lan, R.S.; Wang, Z. Acoustic Signal Positioning and Calibration with IMU in NLOS Environment. In Proceedings of the 2019 Eleventh International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence (ICACI), 2019.

- Chen, R.Z.; Li, Z.; Ye, F.; Guo, G.Y.; Xu, S.A.; Qian, L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, L.X. Precise Indoor Positioning Based on Acoustic Ranging in Smartphone. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.A.; Chen, R.Z.; Guo, G.Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, L.; Ye, F.; Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, L.X. Bluetooth, Floor-Plan, and Microelectromechanical Systems-Assisted Wide-Area Audio Indoor Localization System: Apply to Smartphones. Ieee Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2022, 69, 11744-11754. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Ye, F.; Huang, L.X.; Guo, G.Y.; Xu, S.H.; Chen, D.N.; Chen, L. Precise, Low-Cost, and Large-Scale Indoor Positioning System Based on Audio Dual-Chirp Signals. Ieee Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2023, 72, 1159-1168. [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Yan, K.; Li, Z.; Qian, L.; Xu, S.H.; Niu, X.G.; Chen, L. Large-Scale Indoor Localization Solution for Pervasive Smartphones Using Corrected Acoustic Signals and Data-Driven PDR. Ieee Internet of Things Journal 2023, 10, 15338-15349. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.Q.; Wu, C.P.; Luo, X.A.; Ji, Y.F.; Xiao, J.M. Multi-Information Fusion Indoor Localization Using Smartphones. Applied Sciences-Basel 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Luo, X.N.; Wang, X.H. A Highly Stable Fusion Positioning System of Smartphone under NLoS Acoustic Indoor Environment. Acm Transactions on Internet Technology 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Chen, R.Z.; Li, D.R.; Chen, Y.J.; Guo, G.Y.; Cao, Z.P.; Pan, Y.J. Scene Recognition for Indoor Localization Using a Multi-Sensor Fusion Approach. Sensors 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Neges, M.; Koch, C.; König, M.; Abramovici, M. Combining visual natural markers and IMU for improved AR based indoor navigation. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2017, 31, 18-31. [CrossRef]

- Poulose, A.; Han, D.S. Hybrid Indoor Localization Using IMU Sensors and Smartphone Camera. Sensors 2019, 19. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.T.; Yan, D.Y.; Li, T.; Xia, M.; Shi, C. Pedestrian Gait Information Aided Visual Inertial SLAM for Indoor Positioning Using Handheld Smartphones. Ieee Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 19845-19857. [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.C.; Chen, G.L.; Zhang, Z.H. Efficient image-based indoor localization with MEMS aid on the mobile device. Isprs Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2022, 185, 85-110. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Qin, D.Y.; Bai, J.A.; Ma, L. An Indoor Visual Positioning Method with 3D Coordinates Using Built-In Smartphone Sensors Based on Epipolar Geometry. Micromachines 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Huai, J.Z.; Hua, L.C.; Yang, X.S.; Cao, X.X.; Zhang, P.; Cao, Y.; Qi, L.N.; et al. Multi-sensor integrated navigation/positioning systems using data fusion: From analytics-based to learning-based approaches. Information Fusion 2023, 95, 62-90. [CrossRef]

- Kanaris, L.; Kokkinis, A.; Liotta, A.; Stavrou, S. Fusing Bluetooth Beacon Data with Wi-Fi Radiomaps for Improved Indoor Localization. Sensors 2017, 17. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Sottile, F.; Spirito, M.A.; Garello, R. Hybrid Indoor Positioning Approaches Based on WSN and RFID. In Proceedings of the 2011 4th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security, 7-10 Feb. 2011, 2011; pp. 1-5.

- Bai, L.; Sun, C.; Dempster, A.G.; Zhao, H.B.; Cheong, J.W.; Feng, W.Q. GNSS-5G Hybrid Positioning Based on Multi-Rate Measurements Fusion and Proactive Measurement Uncertainty Prediction. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.X.; Tu, R.; Hong, J.; Zhang, S.X.; Zhang, P.F.; Lu, X.C. Combined positioning algorithm based on BeiDou navigation satellite system and raw 5G observations. Measurement 2022, 190. [CrossRef]

- Monica, S.; Bergenti, F. Hybrid Indoor Localization Using WiFi and UWB Technologies. Electronics 2019, 8. [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.C.; Hsiao, T.J. Indoor Localization System Based on Hybrid Wi-Fi/BLE and Hierarchical Topological Fingerprinting Approach. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2019, 68, 10791-10806. [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.P.; Yu, C.; Xia, Q.H.; Zheng, Z.Q.; Zhao, K.; Chen, W. An Indoor Positioning Method Based on UWB and Visual Fusion. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.J.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.P. A Sequential-Multi-Decision Scheme for WiFi Localization Using Vision-Based Refinement. Ieee Transactions on Mobile Computing 2024, 23, 2321-2336. [CrossRef]

| Author | Time | Survey contents |

| Morar et al. [28] | 2020 | An overview of the field of computer vision-based indoor localization |

| Kunhoth et al. [29] | 2020 | Different computer vision-based indoor navigation and localization systems are reviewed |

| Liu et al. [30] | 2020 | Distance-based acoustic indoor localization is divided into absolute and relative distance localization |

| Guo et al. [31] | 2020 | Fusion-based indoor localization techniques and systems with three fusion features: source, algorithm, and weight space |

| Liu et al. [32] | 2020 | Existing RF-based indoor localization systems are reviewed |

| Ashraf et al. [33] | 2020 | Reviewed methods for estimating a user's indoor location using data from smartphone sensors |

| Simões et al. [34] | 2020 | Indoor Navigation and Positioning System for the Blind |

| Pascacio et al. [35] | 2021 | A systematic review of cooperative indoor localization systems |

| Obeidat et al. [36] | 2021 | Indoor positioning technologies and wireless technologies are reviewed |

| Hou and Bergmann [37] | 2021 | A systematic review and quality assessment of research on PDR and wearable sensors |

| Ouyang and Abed-Meraim [38] | 2022 | Reviewed magnetic fingerprint localization techniques |

| Aparicio et al. [39] | 2022 | Summarizes the main characteristics of acoustic positioning systems in terms of accuracy, coverage area, and update rate |

| Wang et al. [40] | 2022 | A systematic review of smartphone-based inertial localization and navigation methods is presented |

| Chen and Pan [41] | 2024 | Reviewed work related to inertial localization based on deep learning |

| Naser et al. [42] | 2023 | A systematic compendium and analysis of smartphone-based indoor localization methods |

| Zhuang et al. [43] | 2023 | An overview of combined multi-sensor navigation/positioning systems is presented |

| Systems | Equipment | Positioning Methods | Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations | Costs |

| Wi-Fi | Wi-Fi sensors, Wi-Fi AP |

RSSI/Fingerprinting/Wi-Fi RTT | 3–10 m | No additional infrastructure is required, Low cost, Wide coverage |

Cumbersome fingerprint database creation, Susceptible to signal interference and blockage, Fewer devices supporting Wi-Fi RTT protocols |

Medium |

| BLE | Bluetooth sensors, Bluetooth beacons | RSSI/Fingerprinting/Proximity | 1–5 m | Low cost, low power consumption, Easy deployment, Small device size |

Smaller range, Susceptible to signal interference, Poorer signal stability |

Low |

| Inertial navigation |

Inertial sensors (Accelerometer, Gyroscope, Magnetometer) | INS/PDR/Motion constraints | Decreases with increasing positioning time | Sensors built into smartphones, No signal interference |

Problems with error accumulation | Low |

| Barometer | Barometer sensors | Barometric floor positioning | Meter scale | No additional equipment to deploy, low cost |

Vulnerability to external factors | Low |

| Vision | Camera | Feature detection/Visual marker/SLAM | Accuracy depends on time |

No need for base station deployment, Not affected by signal strength |

Susceptible to light conditions, background interference | Low |

| Acoustic | Acoustic sensors, Signal transmitter | TOF/TOA/TDOA/DOA | Depends on the distribution density of the infrastructure | Good compatibility, High scalability, High accuracy potential |

More sensitive to the Doppler effect, Small beacon coverage area, Cumbersome fingerprint database creation |

High |

| UWB | UWB base station, UWB receiver | RSSI/TOA/TDOA/AOA | Centimeter scale | Low power consumption, Insensitive to multipath effects |

High cost, Liquids and metallic materials can block signals |

High |

| 5G | 5G base station, 5G antenna | RSSI/TOA/TDOA/AOA/CSI | Decimeter scale | High-ranging accuracy and reliability | Signal susceptibility to interference | Low |

| Magnetic | Magnetometer | Fingerprinting | Meter scale | Low cost No need to deploy additional equipment |

Poor generalizability, Susceptible to indoor magnetic interference |

Low |

| Method | Time | Author | Research Focus |

| RSSI | 2019 | Amri et al. [52] | A fuzzy localization algorithm calculates the distance between the anchor point and the sensor node using RSSI measurements. |

| 2023 | Vishwakarma et al. [56] | Classification of specific locations into specific regions based on Graph Neural Network (GNN) and collected RSSI values | |

| 2023 | Tao et al. [47] | Extreme value-based AP selection and localization algorithm | |

| Fingerprinting | 2017 | Wang et al. [51] | Deep Learning based Fingerprinting (DeepFi), a deep learning-based indoor fingerprint localization method |

| 2018 | Xu et al. [26] | Utilize indoor environment constraints in the form of a grid-based indoor model to improve the localization of a WiFi-based system. | |

| 2022 | Lan et al. [48] | Super-resolution based fingerprint enhancement framework for fingerprint enhancement as well as super-resolution fusion | |

| 2023 | Wang et al. [49] | Three-dimensional dynamic localization model based on temporal fingerprinting | |

| 2023 | Hosseini et al. [50] | A method for generating virtual fingerprints of building interiors by predicting Wi-Fi RSS values using integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and signal propagation | |

| 2024 | Kargar-Barzi et al. [46] | Lightweight indoor Wi-Fi fingerprint localization method based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and convolutional self-encoder | |

| 2024 | Pan et al. [57] | Indoor Wi-Fi localization fingerprint database construction method based on crow search algorithm optimized density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise and recurrent conditional variational autoencoder-generative adversarial network | |

| Wi-Fi RTT | 2020 | Huang et al. [53] | Learning nonlinear mapping relationship between indoor location and Wi-Fi RTT ranging information using deep convolutional neural network |

| 2020 | Yu et al.[54] | A Wi-Fi RTT-based data acquisition and processing framework for estimating and reducing multipath and Non-Line of Sight (NLOS) errors | |

| 2024 | Guo et al. [55] | Clock drift error reduction based on clock drift theory modeling localization system framework, state monitoring algorithms, and partial differential equation constraint models | |

| 2024 | Cao et al. [58] | WiFi RTT localization method based on Line of Sight (LOS) compensation and trusted NLOS identification |

| Method | Author | Time | Research Focus |

| RSSI | 2021 | You et al. [68] | RSSI-based multipoint localization algorithm |

| 2023 | Assayag et al. [70] | Adaptive path loss model | |

| 2023 | Gentner et al. [63] | Position is calculated on the server using particle filtering and returned to the mobile device | |

| 2024 | Wu et al. [72] | Using KF to attenuate the effect of random perturbations | |

| Fingerprinting | 2023 | Safwat et al. [71] | K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) and Weighted K-Nearest Neighbor (WKNN) based fingerprint localization methods |

| 2023 | Shin et al. [64] | Fingerprint mapping method based on RSS sequence matching | |

| 2024 | Junoh et al. [60] | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based semi-crowdsourced fingerprint map construction method for labor reduction | |

| AOA | 2016 | Van der Ham et al. [11] | A localization method is developed that considers geometrical influences, characteristics of the Quuppa positioning system, and indoor obstructions. |

| 2023 | Xiao et al. [65] | Improving AoA estimation accuracy by estimating phase noise using the extended kalman filter | |

| 2024 | Wan et al. [66] | Improved signal subtraction subspace algorithm to reduce interference from coherent signals and errors caused by movement between people in the room | |

| Proximity | 2015 | Zhao et al. [61] | BLE proximity detection based on particle filtering |

| 2020 | Spachos et al. [67] | BLE proximity detection and RSSI-based localization |

| Author | Time | Research Focus |

| Klein et al. [94] | 2018 | Machine learning classification algorithm to recognize smartphone modes |

| Guo et al. [95] | 2019 | Adaptive walking speed estimation for smartphone based on attitude sensing |

| Zheng et al. [96] | 2020 | Heading estimation algorithm for pocket and swing modes |

| Yao et al. [97] | 2020 | Step detection and step length estimation algorithms for recognizing different walking modes |

| Zhang et al. [98] | 2021 | A low-cost indoor navigation framework combining inertial sensors and indoor map information |

| Zhao et al. [99] | 2023 | Denoising MEMS data using bias drift model and KF |

| Wu et al. [100] | 2024 | PDR algorithm for multi-sensor fusion based on Particle Filter (PF)-UKF |

| Liu et al. [101] | 2024 | Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)-based integration method for pedestrian motion constraints, smartphone sensors and step detection methods |

| Chen et al. [102] | 2024 | 3D localization method based on terrain feature matching |

| Method | Time | Author | Research Focus |

| Image Match | 2020 | Kubícková et al. [111] | Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) algorithm for feature detection and matching to find coordinates of image database using Perspective-n-Point (PnP) method. |

| 2020 | Li et al. [107] | Accurate single-image-based indoor visual localization method | |

| 2021 | Li et al. [112] | Deep belief network based scene classification and PnP algorithm to solve camera position | |

| Object Detection | 2018 | Xiao et al. [109] | Deep learning based localization method for large indoor scenes |

| 2021 | Jung et al. [113] | Deep learning based matching of object position and pose | |

| 2024 | Chen et al. [108] | Landmark matching method to match the landmark within an up-view image with a landmark in the pre-labeled landmark sequence | |

| Visual Marker | 2020 | Tanaka et al. [110] | An ultra-high precision visual marker with pose error less than0.1° |

| Method | Time | Author | Research Focus |

| TOA | 2019 | Zhang et al. [119] | TOA estimation method for extracting first path signal based on the iterative cleaning process |

| 2020 | Liu et al. [115] | TOA estimation method for smartphone based on built-in microphone sensor | |

| 2020 | Cao et al. [120] | A novel TOA detection algorithm for acoustic signals consisting of coarse search and fine search | |

| TDOA | 2019 | Chen et al. [118] | Doppler shift based TDOA correction method |

| 2020 | Bordoy et al. [121] | TDOA measurement method without manual measurement of receiver position | |

| 2023 | Cheng et al. [123] | Maximum likelihood algorithms combined with TDOA measures | |

| Fingerprinting | 2021 | Wang et al. [122] | Detection of the first path based on time-division multiplexing, utilizing Power Spectral Density (PSD) of the frequency domain signal as a fingerprinting feature |

| 2024 | Xu et al. [116] | Constructing an audio-chirp-attention network model fusing edge detection maps with normalized energy density maps and correlating fingerprint datasets with corresponding spatial locations |

| Method | Time | Author | Research Focus |

| TDOA | 2019 | Pan et al. [127] | Improved TDOA and KF to compute the position of target nodes |

| 2021 | Bottigliero et al. [131] | No need for time synchronization between sensors, using a unidirectional communication method to reduce the cost and complexity of tags | |

| AOA | 2021 | Monfared et al. [128] | Iterative AOA localization algorithm for multilevel anchor selection under NLOS conditions |

| 2024 | Zhong et al. [132] | AOA-based position tracking system and data processing algorithms to minimize system static error | |

| TOA | 2021 | Li et al. [136] | Improved root-Multiple Signal Classification (MUSIC) algorithm for joint estimation of TOA and DOA |

| 2021 | Gong et al. [137] | Frequency doubling and cluster counting algorithm for joint estimation of TOA and DOA | |

| TOF | 2020 | Li et al. [129] | A neural network approach has been adopted to enhance the system's performance in NLOS scenarios. |

| RSS | 2022 | Chong et al. [133] | Integration of UWB RSS into Wi-Fi RSS fingerprinting-based indoor localization system |

| System | References | Cost | Strengths/Weaknesses |

| Wi-Fi/PDR | [139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150] | Medium | Wi-Fi positioning results provide accurate initial positioning, fusing PDR for position update and reducing the cumulative error of PDR. However, fewer devices support the Wi-Fi RTT protocol and are susceptible to signal interference and blockage. |

| BLE/PDR | [151,152,153,154,155,156,157] | Low | Bluetooth positioning results provide accurate initial positioning and fusion of PDR for position updating to reduce the cumulative error of PDR. The lower cost and power consumption of BLE and PDR are suitable as a pervasive indoor positioning method, but the fusion method has less coverage and is susceptible to signal interference. |

| Acoustic/PDR | [158,159,160,161,162,163,164] | High | Acoustic signals can provide the relative positional relationship between the sound source and the device, which is used to reduce the accumulated error of the PDR method. However, acoustic signals are susceptible to the Doppler effect and are easily blocked and absorbed by obstacles in complex indoor scenes, and high accuracy can be achieved by deploying sufficient devices in large, more open scenes. |

| Vision/PDR | [165,166,167,168,169,170] | Low | Visual localization using the image information acquired by the camera, combined with the attitude and motion information provided by the PDR, can reduce the cumulative error of the PDR. Visual localization is not subject to signal interference, but is susceptible to lighting conditions and background interference, and requires high smartphone performance. |

| Author | Time | Research Focus |

| Xu et al. [143] | 2019 | Enhanced PF with two different state update strategies and fast reinitialization |

| Sun et al. [139] | 2020 | Least-Squares (LS)-based real-time ranging error compensation model and Weighted Least-Squares (WLS)-based adaptive Wi-Fi FTM localization algorithm |

| Liu et al. [140] | 2021 | Adaptive filtering system consisting of multiple EKFs and outlier detection methodology |

| Choi et al. [141] | 2021 | Calibration-free localization using Wi-Fi ranging and PDR |

| Guo et al. [12] | 2022 | A tightly coupled method based on Wi-Fi RTT, RSSI, and MEMS-IMU |

| Chen et al. [144] | 2022 | Federated Particle Filter (FPF) fusion of PDR and Wi-Fi based on information sharing principle |

| Huang et al. [145] | 2023 | Improved particle swarm optimization-based algorithm for integrating inertial sensors and RSS fingerprinting |

| Wu et al. [147] | 2023 | Using only one Wi-Fi FTM AP and estimating position with the smartphone's built-in inertial sensor |

| Guo et al. [149] | 2023 | Tightly coupled fusion platform for Wi-Fi RTT, RSS and data-driven PDR based on factor graph optimization |

| Yang et al. [148] | 2023 | Fuzzy logic-based fusion localization method adaptively schedules energy-consuming Wi-Fi scans |

| Lin et al. [146] | 2024 | Enabling PF integration of PDR, Wi-Fi and indoor maps |

| Zhou et al. [142] | 2024 | EKF-based multimodal sensor fusion algorithm for indoor localization |

| Xu et al. [150] | 2024 | Enhancing Wi-Fi fingerprint localization with a co-teaching approach using crowdsourced sequential RSS and IMU data |

| Author | Time | Research Focus |

| Dinh et al. [151] | 2020 | Estimating approximate distance methods to estimate initial position and lightweight fingerprinting methods |

| Chen et al. [152] | 2022 | Data-driven integration of BLE-based inertial navigation using PF |

| Ye et al. [153] | 2022 | Angle estimation algorithm based on signal fitting and propagator direct data acquisition |

| Jin et al. [154] | 2023 | PF-based indoor localization framework for BLE and PDR |

| Guo et al. [155] | 2023 | Hybrid indoor localization approach with pedestrian reachability and floor map constraints based on virtual wireless devices |

| Guo et al. [156] | 2023 | Robust adaptive EKF-based multi-level constraint fusion localization framework |

| Liu et al. [157] | 2024 | A smartphone indoor localization method that fuses map positioning anchors with multi-sensor fusion |

| Author | Time | Research Focus |

| Wang et al. [158] | 2019 | Positioning system combining acoustic signals and IMUs to correct NLOS errors |

| Chen et al. [159] | 2021 | Introduction of EKF to integrate IMU and acoustic TDOA ranging data |

| Xu et al. [160] | 2022 | Hybrid acoustic signal transmission architecture based on frequency division multiple access, time division multiple access and space division multiple access |

| Liu et al. [161] | 2023 | Low-cost, large-scale indoor positioning system based on audio dual chirp signals |

| Guo et al. [162] | 2023 | Acoustic measurement compensation method and measurement quality assessment and control strategy |

| Yan et al. [163] | 2023 | Fusion of CHAN and improved PDR indoor localization system |

| Wang et al. [164] | 2023 | Fusion of acoustic signals and IMU data using KF |

| Author | Time | Research Focus |

| Liu et al. [165] | 2017 | A multi-sensor fusion approach for camera, WiFi and inertial sensors on smartphones |

| Neges et al. [166] | 2017 | Indoor navigation system based on IMU and real-time visual video streaming AR technology |

| Poulose et al. [167] | 2019 | Indoor positioning method using smartphone IMU, Wi-Fi RSSI and camera |

| Dong et al. [168] | 2022 | Visual inertial mileage assisted by pedestrian step information |

| Shu et al. [169] | 2022 | Efficient image-based indoor positioning using MEMS |

| Zheng et al. [170] | 2023 | An indoor visual positioning method with three-dimensional coordinates using built-in smartphone sensors based on epipolar geometry |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).