Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background/Objectives: It is essential to identify acute myocardial infarction patients with greater risk of deterioration following primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Given an inconsistent result about predictors of 30-day outcomes regarding scoring system for first episode of acute myocardial infarction, the objective of this study is to develop novel scoring system to predict 30-day mortality among patients with first episode of acute myocardial infarction underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Methodology. Retrospective study was conducted with total sampling for all patients with first-time acute myocardial infarction underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention, between 2021 to 2024 at Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Indonesia. We performed a total sampling, collected 1714 patients, in which 1535 patients were included.. Primary outcomes were 30-day mortality. Results. The analysis included 1535 patients: derivation set 926 and validation set 609. In our study, the 30-day mortality was 20.7%. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to build prediction models in derivation group, and then validated in validation cohort. Discrimination, calibration and clinical usefulness of the predicting model were assessed using the C-index, calibration plot and decision curve analysis. After pairwise comparison, the best performing model was chosen to build a nomogram according to the regression coefficients. The AUROC was 0.944 (0.906–0.972) in the derivation set and 0.959 (0.921–0.983) in the validation set. Conclusion. After adjusting for potential confounders, we developed RURUS SURYAWAN, a novel scoring system to identify predictor of 30-day mortality among acute myocardial infarction before primary percutaneous coronary intervention.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Model Development

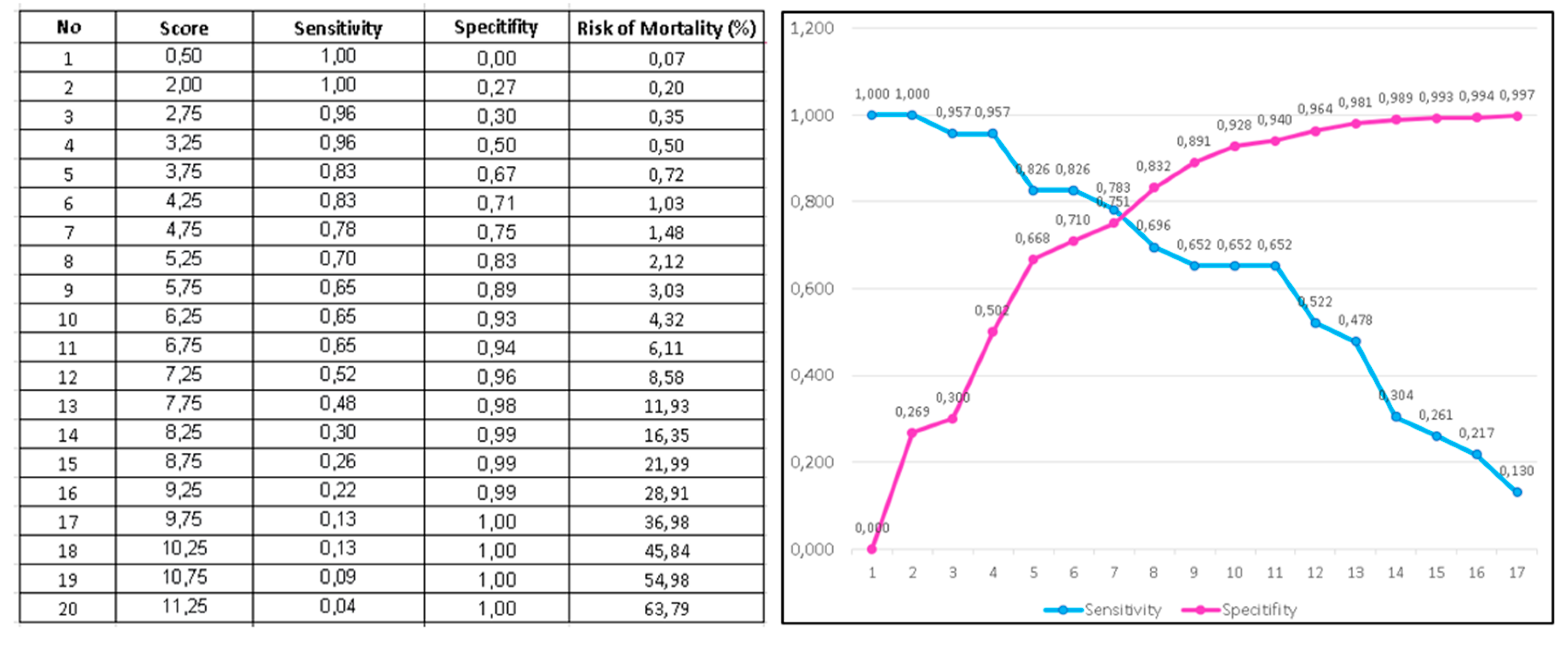

3.3. RURUS SURYAWAN as Novel Risk Score for 30-Days Mortality Among Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

| Variables | Multivariate analysis | Point assigned | ||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Resting heart rate (>110 bpm) | 1.51 | 1.20 - 1.90 | 0.024 | 1 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18kg/m2) | 1.37 | 1.15 - 1.99 | 0.033 | 1 |

| Respiratory rate (>28 / minutes) | 1.18 | 1.03 - 1.34 | 0.039 | 1 |

| Urine-output, first 24 hours admission (<0.5 ml / kg BW / hour) | 2.56 | 1.79 - 4.44 | <0.001 | 1 |

| Saturation O2 peripheral (<90%) | 1.35 | 1.21 - 1.49 | 0.026 | 1 |

| Systolic blood pressure during admission (<90 mmHg) | 2.31 | 1.67 - 4.02 | <0.001 | 1 |

| Urea nitrogen (> 50 mg/dL) | 1.93 | 1.81 - 2.04 | <0.001 | 1 |

| Reduced ejection fraction. (baseline LVEF < 40%) | 1.21 | 1.08 - 1.37 | 0.042 | 1 |

| time delaYed of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (door-to-balloon time >2 hours) | 1.89 | 1.56 - 2.37 | 0.002 | 1 |

| Age (>70 years old) | 1.55 | 1.23 - 2.08 | 0.021 | 1 |

| Women | 1.17 | 1.02 - 1.33 | 0.041 | 1 |

| Anemia (Hb < 10 g/dL) | 1.79 | 1.45 - 2.55 | 0.003 | 1 |

| NT-proBNP (> 1500 pg/mL) | 2.17 | 1.58 - 3.74 | <0.001 | 1 |

| Total score | 13 | |||

| RURUS SURYAWAN score | Stratification | Risk of 30-day mortality |

| 0-3 points | Low risk | <1% |

| 4-6 points | Intermediate risk | 2-5% |

| 7-9 points | High risk | 8-30% |

| 10-13 points | Very high risk | >50% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Strength

4.2. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AMI | Acute Myocardial Infarction |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| AUROC | area under the receiver operating characteristic |

| CAPRICORN | CArvedilol Post-infaRct survIval COntRolled evaluatioN |

| EPHESUS | Eplerenone in patients with heart failure due to systolic dysfunction complicating acute myocardial infarction |

| GRACE | Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events |

| GUSTO | Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| MINAP | Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project |

| NSTEMI | Non ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide |

| OASIS | Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score |

| OPTIMAAL | Optimal Therapy in Myocardial Infarction with the Angiotensin II Antagonist Losartan |

| PCI | Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PPCI | Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention |

| PURSUIT | Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in Unstable Angina: Receptor Suppression Using Integrilin |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristic |

| STEMI | ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction |

| TIMI | Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction |

| VALIANT | VALsartan In Acute Myocardial iNfarcTion |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- Bamford P, Henry TD, O’Neill WW, Grines CL. The Revolution of STEMI Care: A Story of Resilience, Persistence, and Success. Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions 2024 Nov 3; 11: 102395.

- Dadjoo Y, Mahmoodi Y. The prognosis of primary percutaneous coronary intervention after one year clinical follow up. Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2013 Mar;7(1):21-4.

- Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, de Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: Description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943–57. [CrossRef]

- Yan F, Zhang Y, Pan Y, Li S, Yang M, Wang Y, Yanru C, Su W, Ma Y, Han L. Prevalence and associated factors of mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention for adult patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Res Med Sci. 2023 Mar 16;28:17. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura Y, Yoshimachi F, Murotani N, Karasawa Y, Nagamatsu H, Kasai S, Ikari Y. Comparison of Mortality Prediction by the GRACE Score, Multiple Biomarkers, and Their Combination in All-comer Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Intern Med. 2023 Feb 15;62(4):503-510. [CrossRef]

- Pramudyo M, Yahya AF, Martanto E, Tiksnadi BB, Karwiky G, Rafidhinar R, Putri GNI. Predictors of 30-day Mortality in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome in Hasan Sadikin Hospital, Bandung, Indonesia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Acta Medica Indonesiana. 2022 Dec 54;3.

- Ioacara S, Popescu AC, Tenenbaum J, Dimulescu DR, Popescu MR, Sirbu A, Fica S. Acute Myocardial Infarction Mortality Rates and Trends in Romania between 1994 and 2017. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Dec 31;17(1):285. [CrossRef]

- Salari N, Morddarvanjoghi F, Abdolmaleki A, Rasoulpoor S, Khaleghi AA, Hezarkhani LA, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023 Apr 22;23(1):206. [CrossRef]

- Yoon SSS, et al. Trends in the prevalence of coronary heart disease in the US: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2012. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(4):437–445. [CrossRef]

- Danny S, Roebiono P, Soesanto A, & Kasim M. Factors Influencing Major Cardiovascular Event Post Acute Myocardial Infarction in Woman. Indonesian Journal of Cardiology, 30(1), 3-12. [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva P, Kaur K, Fatima S, Mahak F, Noman M, Siddenthi SM, Surksha MA, Munir M, Fatima F, Sultana SS, Varrassi G, Khatri M, Kumar S, Elder M, Mohamad T. Advancements in Myocardial Infarction Management: Exploring Novel Approaches and Strategies. Cureus. 2023 Sep 19;15(9):e45578. [CrossRef]

- Rohani, C., Jafarpoor, H., Mortazavi, Y., Esbakian, B., Gholinia, H. Mortality in patients with myocardial infarction and potential risk factors: A five-year data analysis. ARYA Atherosclerosis Journal, 2022; 18(3): 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gong IY, Goodman SG, Brieger D, Gale CP, Chew DP, Welsh RC, Huynh T, DeYoung JP, Baer C, Gyenes GT, Udell JA, Fox KAA, Yan AT; Canadian GRACE/GRACE-2 and CANRACE Investigators. GRACE risk score: Sex-based validity of 30-day mortality prediction in Canadian patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2017 Oct 1;244:24-29.

- McClure MW, Berkowitz SD, Sparapani R, Tuttle R, Kleiman NS, Berdan LG, Lincoff AM, Deckers J, Diaz R, Karsch KR, Gretler D, Kitt M, Simoons M, Topol EJ, Califf RM, Harrington RA. Clinical significance of thrombocytopenia during a non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. The platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in unstable angina: receptor suppression using integrilin therapy (PURSUIT) trial experience. Circulation. 1999 Jun 8;99(22):2892-900. [CrossRef]

- Amin ST, Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Sloan S, Contant C, Murphy S, Antman EM. Dynamic TIMI risk score for STEMI. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013 Jan 29;2(1):e003269. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AE, Kramer AA, Clifford GD. A new severity of illness scale using a subset of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation data elements shows comparable predictive accuracy. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:1711–1718. [CrossRef]

- Johnson AE, Kramer AA, Clifford GD. A new severity of illness scale using a subset of acute physiology and chronic health evaluation data elements shows comparable predictive accuracy. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41:1711–1718. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhang Z, Hu T. Effectiveness of LODS, OASIS, and SAPS II to predict 30-day mortality for intensive care patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Sci Rep. 2021 Dec 13;11(1):23887. [CrossRef]

- Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–2963. [CrossRef]

- Kolovou GD, Katsiki N, Mavrogeni S. Risk Scores After Acute Coronary Syndrome. Angiology. 2017 Mar;68(3):185-188. [CrossRef]

- Correia LC, Garcia G, Kalil F, Ferreira F, Carvalhal M, Oliveira R, Silva A, Vasconcelos I, Henri C, Noya-Rabelo M. Prognostic value of TIMI score versus GRACE score in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014 Aug;103(2):98-106. [CrossRef]

- Choi SY, Kim MH, Serebruany V. Comparison of ACUITY, CRUSADE, and GRACE Risk Scales for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Patients Treated with Dual-Antiplatelet Therapy. TH Open. 2018 Nov 27;2(4):e399-e406. [CrossRef]

- Amador P, Santos J F, Gonçalves S, Seixo F, Soares L. Comparison of ischemic and bleeding risk scores in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes. Acute Card Care. 2011;13(02):68–75. [CrossRef]

- McNamara RL, Kennedy KF, Cohen DJ, Diercks DB, Moscucci M, Ramee S, Wang TY, Connolly T, Spertus JA. Predicting 30-day Mortality in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 9;68(6):626-635. [CrossRef]

- Jabre P, Roger VL, Weston SA, Adnet F, Jiang R, Vivien B, Empana JP, Jouven X. Resting heart rate in first year survivors of myocardial infarction and long-term mortality: a community study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014 Dec;89(12):1655-63. [CrossRef]

- Heidland UE, Strauer BE. Left ventricular muscle mass and elevated heart rate are associated with coronary plaque disruption. Circulation. 2001;104(13):1477–1482. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Sasmita BR, Hu X, Xue Y, Gan H, Xiang Z, et al. Blood Urea Nitrogen for Short-Term Prognosis in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction. Int J Clin Pract. 2022;2022:9396088. [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi Y, Aoki J, Tanabe K, Nakao K, Ozaki Y, Kimura K, et al. A High Level of Blood Urea Nitrogen Is a Significant Predictor for 30-day Mortality in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Int Heart J. 2018;59:263-71. [CrossRef]

- Bosch X, Théroux P. Left ventricular ejection fraction to predict early mortality in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2005 Aug;150(2):215-20. [CrossRef]

- Miller AL, Dib C, Li L, Chen AY, Amsterdam E, Funk M, Saucedo JF, Wang TY. Left ventricular ejection fraction assessment among patients with acute myocardial infarction and its association with hospital quality of care and evidence-based therapy use. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012 Sep 1;5(5):662-71. [CrossRef]

- Srimahachota S, Kanjanavanit R, Boonyaratavej S, et al. Demographic, management practices and 30-day outcomes of Thai Acute Coronary Syndrome Registry (TACSR): the difference from the Western world. J Med Assoc Thai 2007;90 Suppl 1:1-11.

- Champasri K, Srimahachota S, Chandavimol M, Udayachalerm W, Thakkinstian A, Sookananchai B, Phatharajaree W, Kiatchoosakun S, Sansanayudh N. Door-to-device time and mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention: insight from real world data of Thai PCI Registry. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2023 Oct 31;13(5):843-854. [CrossRef]

- Tsukui T, Sakakura K, Taniguchi Y, et al. Association between the Door-to-balloon Time and Mid-term Clinical Outcomes in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Intern Med 2020;59:1597-603. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khatib SM, Stebbins AL, Califf RM, Lee KL, Granger CB, White HD, Armstrong PW, Topol EJ, Ohman EM; GUSTO-III trial. Sustained ventricular arrhythmias and mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-III trial. Am Heart J. 2003 Mar;145(3):515-21. [CrossRef]

- Damluji AA, Forman DE, Wang TY, Chikwe J, Kunadian V, Rich MW, Young BA, Page RL 2nd, DeVon HA, Alexander KP; American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Older Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health. Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome in the Older Adult Population: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023 Jan 17;147(3):e32-e62. [CrossRef]

- Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A, Dinh DT, Lefkovits J, Zaman S.. Sex differences persist in time to presentation, revascularization, and mortality in myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(10). [CrossRef]

- Dennis JA, Zhang Y, Zhang F, Kopel J, Abohelwa M, Nugent K. Comparison of 30-day mortality and readmission frequency in women versus men with acute myocardial infarction. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021;34(6):668-672. Published 2021 Jul 21. [CrossRef]

- Shu DH, Ransom TP, O'Connell CM, et al. Anemia is an independent risk for mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2006;5:8. Published 2006 Apr 7. [CrossRef]

- Mamas MA, Kwok CS, Kontopantelis E, Fryer AA, Buchan I, Bachmann MO, Zaman MJ, Myint PK. Relationship Between Anemia and Mortality Outcomes in a National Acute Coronary Syndrome Cohort: Insights From the UK Myocardial Ischemia National Audit Project Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 Nov 19;5(11):e003348. [CrossRef]

- Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, Xie C, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2006;114:774–782. [CrossRef]

- Nikolsky E, Aymong ED, Halkin A, Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Merhan R, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T, Turco M, Cohen DA, Negoita M, Lansky AJ, Stone GW. Impact of anemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: analysis from the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:547–553. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez A, Regueiro A, Hernández J, Kasa G, Sitges M, Bosch X, Heras M. Additional value of B-type natriuretic peptide on discrimination of patients at risk for mortality after a non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2014;3(2):132–140. [CrossRef]

- Schellings DA, Adiyaman A, Dambrink JE, et al. Predictive value of NT-proBNP for 30-day mortality in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a comparison with the GRACE and TIMI risk scores. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:471-476. Published 2016 Nov 21. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n=1535) |

Derivation group (n=926) |

Validation group (n=609) |

P value for derivation vs validation |

Alive (n=1217) |

Died (n=318) |

P value for alive vs dead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.856 | 0.041 | |||||

| Male (n, %) | 1211 (78.9%) | 730 (78.8%) | 481 (78.9%) | 972 (79.9 %) | 239 (75.2%) | ||

| Female (n, %) | 324 (21.1%) | 196 (21.2%) | 128 (21.1%) | 245 (20.1%) | 79 (24.8%) | ||

| Age, mean + SD, years | 69.86 + 9.47 | 69.85 + 9.49 | 69.87 + 9.23 | 0.798 | 68.21 + 9.45 | 71.42 + 10.27 | 0.021 |

| BMI, mean + SD, kg/m2 | 23.12 + 6.93 | 23.05 + 8.23 | 23.29 + 7.25 | 0.767 | 24.27 + 8.03 | 21.43 + 7.56 | 0.033 |

| Resting heart rate during admission, mean + SD, bpm | 91.44 + 11.03 | 91.43 + 11.97 | 91.45 + 12.05 | 0.863 | 88.75 + 10.99 | 96.82 + 17.49 | 0.024 |

| Systolic blood pressure during admission, mean + SD, mmHg | 123.37 + 14.69 | 123.71 + 13.18 | 123.33 + 13.95 | 0.512 | 127.51 + 13.32 | 112.56 + 21.44 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure during admission, mean + SD, mmHg | 64.27 + 9.68 | 64.64 + 9.50 | 64.30 + 9.12 | 0.918 | 64.90 + 7.90 | 61.87 + 12.88 | 0.053 |

| Respiratory rate during admission, mean + SD, bpm | 22.80 + 4.10 | 22.82 + 3.99 | 22.76 + 4.03 | 0.821 | 20.62 + 3.90 | 28.56 + 7.84 | 0.039 |

| Core temperature during admission, mean + SD, °C | 36.23 + 0.72 | 36.24 + 0.71 | 36.22 + 0.78 | 0.719 | 36.40 + 0.52 | 36.14 + 0.87 | 0.125 |

| Saturation O2 peripheral, mean + SD, % | 97.31 + 4.87 | 97.24 + 4.67 | 97.35 + 4.19 | 0.658 | 97.63 + 3.56 | 92.23 + 6.34 | 0.026 |

| Urine-output (first 24 hours), median (lower-upper), mL/24 hours | 1.350 (880–2.200) |

1.340 (870-2.100) | 1.355 (886-2.230) | 0.932 | 1.480 (890-2.300) | 1.160 (550-1.900) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, mean + SD, % | 46.93 + 13.91 | 46.92 + 13.79 | 46.88 + 14.29 | 0.799 | 49.32 + 11.79 | 41.27 + 21.79 | 0.042 |

| Haematocrit, mean (SD), % | 31.91 (5.20) | 31.77 (5.13) | 32.25 (5.36) | 0.151 | 31.94 (5.19) | 31.69 (5.27) | 0.571 |

| Red cells, mean (SD), ×1012/L | 3.58 (0.63) | 3.55 (0.62) | 3.62 (0.65) | 0.088 | 3.58 (0.62) | 3.54 (0.70) | 0.411 |

| MCH, mean (SD), pg | 27.89 + 1.55 | 27.88 + 1.49 | 27.89 + 1.69 | 0.394 | 29.53 (2.58) | 29.63 (2.87) | 0.647 |

| MCHC, mean (SD), % | 29.81 + 1.34 | 29.87 + 1.37 | 29.77 + 1.35 | 0.701 | 32.88 (1.41) | 32.75 (1.36) | 0.275 |

| MCV, mean (SD), fL | 89.90 (6.53) | 90.01 (6.47) | 89.66 (6.67) | 0.396 | 89.81 (6.43) | 90.47 (7.16) | 0.242 |

| RDW, mean (SD), % | 15.95 (2.13) | 16.01 (2.25) | 15.81 (1.82) | 0.139 | 15.83 (2.07) | 16.75 (2.33) | <0.001 |

| White cells, mean (SD), /×10∧9/L | 10.54 (4.29) | 10.54 (4.31) | 10.53 (4.23) | 0.980 | 10.20 (4.11) | 12.78 (4.78) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count, median (lower-upper), ×109/L | 222.67 (168.91–304.25) |

222.12 (168.91–301.38) |

224.03 (168.97–306.78) |

0.582 | 226.09 (173.40–305.33) |

198.56 (134.68–262.07) |

<0.001 |

| NT-proBNP, median (lower-upper), pg/ml | 5840.00 (2251.00–14 968.00) |

6217.00 (2341.00–15 555.00) |

4994.00 (2088.38–13 629.75) |

0.102 | 5302.00 (2143.00–13 666.50) |

9469.00 (3082.50–3662.75) |

<0.001 |

| hsTnI, median (lower-upper), ng/ml | 89.25 (46.00–185.19) | 85.00 (46.92–185.88) | 99.00 (44.00–185.00) | 0.509 | 90.00 (47.00–182.13) | 83.12 (37.85–38.63) | 0.794 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, median (lower-upper), mg/dL | 30.67 (20.83–45.25) | 30.67 (20.56–45.08) | 30.49 (22.25–45.36) | 0.580 | 29.25 (20.11–43.00) | 39.62 (27.06–57.16) | <0.001 |

| Random blood glucose, mean (SD), mEq/L | 148.80 (51.49) | 148.07 (52.09) | 150.49 (50.12) | 0.462 | 148.14 (50.46) | 153.01 (57.63) | 0.270 |

| Sodium, mean (SD), mEq/L | 138.89 (4.15) | 138.85 (4.17) | 138.98 (4.12) | 0.636 | 139.01 (3.98) | 138.20 (5.02) | 0.023 |

| Potassium, mean (SD), mEq/L | 4.18 (0.41) | 4.17 (0.41) | 4.18 (0.42) | 0.662 | 4.15 (0.39) | 4.32 (0.53) | <0.001 |

| Chloride, mean (SD), mEq/L | 102.28 (5.34) | 102.27 (5.43) | 102.32 (5.14) | 0.875 | 102.17 (5.21) | 103.10 (6.00) | 0.040 |

| Calcium, total, mean (SD), mg/dL | 8.50 (0.57) | 8.49 (0.58) | 8.54 (0.56) | 0.169 | 8.54 (0.55) | 8.24 (0.62) | <0.001 |

| Magnesium, mean (SD), mg/dL | 2.12 (0.25) | 2.12 (0.26) | 2.13 (0.24) | 0.420 | 2.11 (0.24) | 2.17 (0.29) | 0.011 |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.38 (0.07) | 7.38 (0.07) | 7.37 (0.07) | 0.041 | 7.38 (0.06) | 7.36 (0.07) | <0.001 |

| PO2, mean (SD), mm Hg | 85.54 (12.86) | 85.48 (12.95) | 85.67 (12.65) | 0.846 | 86.82 (12.85) | 84.07 (12.85) | 0.141 |

| PCO2, mean (SD), mm Hg | 45.54 (12.86) | 45.48 (12.95) | 45.67 (12.65) | 0.846 | 45.82 (12.85) | 44.07 (12.85) | 0.141 |

| Bicarbonate, mean (SD), mEq/L | 26.91 (5.17) | 26.90 (5.23) | 26.94 (5.02) | 0.906 | 27.37 (4.98) | 24.00 (5.42) | <0.001 |

| Lactate, median (Q1–Q3), mmol/L | 1.60 (1.20–2.20) | 1.60 (1.20–2.20) | 1.65 (1.25–2.20) | 0.309 | 1.60 (1.20–2.10) | 2.00 (1.36–3.08) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.072 | 0.013 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 332 (28.21%) | 220 (26.67%) | 112 (31.82%) | 274 (26.94%) | 58 (36.48%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 845 (71.79%) | 605 (73.33%) | 240 (68.18%) | 743 (73.06%) | 101 (63.52%) | ||

| Supraventricular arrhythmias | 0.918 | <0.001 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 646 (54.89%) | 452 (54.79%) | 194 (55.11%) | 578 (56.83%) | 67 (42.14%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 531 (45.11%) | 373 (45.21%) | 158 (44.89%) | 439 (43.17%) | 92 (57.86%) | ||

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 0.857 | 0.614 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 1076 (91.42%) | 755 (91.52%) | 321 (91.19%) | 928 (91.25%) | 147 (92.45%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 101 (8.58%) | 70 (8.48%) | 31 (8.81%) | 89 (8.75%) | 12 (7.55%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.390 | 0.086 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 681 (57.86%) | 484 (58.67%) | 197 (55.97%) | 579 (56.93%) | 102 (64.15%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 496 (42.14%) | 341 (41.33%) | 155 (44.03%) | 438 (43.07%) | 57 (35.85%) | ||

| Anemia | 0.822 | <0.001 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 778 (66.10%) | 547 (66.30%) | 231 (65.62%) | 653 (64.21%) | 124 (77.99%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 399 (33.90%) | 278 (33.70%) | 121 (34.38%) | 364 (35.79%) | 35 (22.01%) | ||

| Hyperlipidaemia | 0.275 | 0.067 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 730 (62.02%) | 520 (63.03%) | 210 (59.66%) | 620 (60.96%) | 109 (68.55%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 447 (37.98%) | 305 (36.97%) | 142 (40.34%) | 397 (39.04%) | 50 (31.45%) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.937 | <0.001 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 747 (63.47%) | 523 (63.39%) | 224 (63.64%) | 625 (61.46%) | 122 (76.73%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 430 (36.53%) | 302 (36.61%) | 128 (36.36%) | 392 (38.54%) | 37 (23.27%) | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.697 | <0.001 | |||||

| No (n, %) | 1389 (90.49%) | 761 (92.24%) | 327 (92.90%) | 1118 (91.86%) | 271 (85.22%) | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 146 (9.51%) | 64 (7.76%) | 25 (7.10%) | 99 (8.13%) | 47 (14.78%) | ||

| 30-day mortality | 0.106 | – | |||||

| No (n, %) | 1217 (79.28%) | 709 (76.57%) | 508 (83.42%) | – | – | ||

| Yes (n, %) | 318 (20.72 %) | 217 (23.43%) | 101 (16.58 %) | – | – |

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | ||||

| Sex, women, % | 1.33 | 1.04 - 1.78 | 0.037 | 1.17 | 1.02 - 1.33 | 0.041 | |||

| Age, years | 1.72 | 1.34 - 2.24 | 0.0197 | 1.55 | 1.23 - 2.08 | 0.021 | |||

| BMI, mean + SD, kg/m2 | 1.44 | 1.18 - 2.12 | 0.027 | 1.37 | 1.15 - 1.99 | 0.033 | |||

| Resting heart rate, bpm | 1.78 | 1.48 to 2.14 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.20 to 1.90 | 0.004 | |||

| Systolic blood pressure during admission (<90 mmHg) | 2.97 | 1.95 - 4.59 | <0.001 | 2.31 | 1.67 - 4.02 | <0.001 | |||

| Respiratory rate during admission, bpm | 1.21 | 1.04 - 1.45 | 0.032 | 1.18 | 1.03 - 1.34 | 0.039 | |||

| Saturation O2 peripheral (<90%) | 1.45 | 1.28 - 1.77 | 0.018 | 1.35 | 1.21 - 1.49 | 0.026 | |||

| Urine-output, first 24 hours admission (<0.5 ml / kg BW / hour) | 2.81 | 1.98 – 5.13 | <0.001 | 2.56 | 1.79 - 4.44 | <0.001 | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 2.02 | 1.91 - 2.13 | <0.001 | 1.93 | 1.81 - 2.04 | <0.001 | |||

| Red blood cells, ×1012/L | 0.82 | 0.58 - 1.14 | 0.233 | NA | |||||

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 1.94 | 1.62 - 2.88 | 0.002 | 1.79 | 1.45 - 2.55 | 0.003 | |||

| MCV, fL | 1.03 | 0.92 - 1.98 | 0.120 | NA | |||||

| MCH, pg | 1.07 | 0.99 - 1.16 | 0.098 | NA | |||||

| White cells, ×10∧9/L | 1.11 | 0.96 to 1.16 | 0.057 | NA | |||||

| Lymphocytes, % | 0.92 | 0.88 - 1.15 | 0.078 | NA | |||||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 1.12 | 0.98 - 1.16 | 0.074 | NA | |||||

| PaO2, mm Hg | 0.91 | 0.86 – 1.03 | 0.355 | NA | |||||

| PaCO2, mm Hg | 0.94 | 0.86 – 0.97 | 0.098 | NA | |||||

| Sodium, mEq/L | 0.95 | 0.91 to 0.99 | 0.197 | NA | |||||

| Potassium, mEq/L | 1.77 | 1.23 - 2.17 | 0.052 | NA | |||||

| Calcium, mg/dL | 0.95 | 0.78 - 1.34 | 0.144 | NA | |||||

| Magnesium, mg/dL | 0.89 | 0.27 - 1.02 | 0.064 | NA | |||||

| Anion gap, mEq/L | 1.23 | 1.15 - 1.32 | 0.048 | 1.05 | 0.97 - 1.27 | 0.053 | |||

| Lactate, mmol/L | 1.28 | 1.18 - 1.44 | 0.046 | 1.07 | 0.99 - 1.40 | 0.052 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | No | 1 | |||||||

| Yes | 1.85 | 1.30 - 2.76 | 0.016 | 1.54 | 1.14 - 2.43 | 0.024 | |||

| hsTnI, ng/mL | 1.02 | 0.95 - 1.07 | 0.355 | NA | |||||

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 2.82 | 1.90 - 4.65 | <0.001 | 2.17 | 1.58 - 3.74 | <0.001 | |||

| Ejection Fraction, % | 1.45 | 1.22 - 1.92 | 0.028 | 1.21 | 1.08 - 1.37 | 0.042 | |||

| Time for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, minutes | 1.91 | 1.58 - 2.57 | <0.001 | 1.89 | 1.56 - 2.37 | 0.002 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).