1. Introduction

Surgical procedures represent essential medical interventions that, beyond their technical aspects, entail significant emotional challenges for patients. Factors that are associated with these procedures, such as stress, anxiety, and fear, not only impact psychological well-being but also influence recovery capacity and clinical outcomes. In this context, social support emerges as a key factor in mitigating these adverse effects, acting as a protective resource that facilitates both the physical and emotional recovery of patients. However, the specific influence of social support in surgical contexts, particularly in patients with complex conditions such as retinal detachment, remains an area that requires further investigation in healthcare settings [

1,

2].

Retinal detachment, a severe medical condition that threatens vision, constitutes an ophthalmological emergency that often necessitates immediate surgical intervention. The effectiveness of this intervention depends not only on technical aspects, but also on the management of psychosocial factors. Social support, stress management, and treatment adherence play crucial roles in the patient’s recovery process [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Social support, a concept originally introduced by Durkheim, encompasses both tangible assistance and emotional backing, which are essential elements for improving treatment adherence and reducing postoperative complications. Recent studies have demonstrated that patients with robust social support networks experience a faster recovery and lower incidences of complications such as infections or recurrences. In retinal detachment, adherence to postoperative care instructions—such as specific positioning, medication adherence, and ocular care—requires a supportive social environment that facilitates compliance [

10,

11,

12].

An appropriate social environment not only aids in physical recovery but also protects patients from the psychological complications associated with surgery. Strategies such as preoperative visits, telephone support, and technological interventions, including augmented reality applications, have proven effective in reducing anxiety and humanizing the surgical experience [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The perception of isolation in settings such as the operating room, where technical focus often outweighs emotional care, underscores the need for a comprehensive and humanized approach that considers both technical demands and the emotional well-being of the patient [

17,

18,

19].

Postoperative care for retinal detachment patients involves fundamental aspects such as pain management, recovery from anesthesia, head positioning control, pressure and exertion regulation, and the prevention of severe complications. However, adherence to these recommendations depends not only on medical guidance but also on the capacity of the patient’s social environment to assist with basic daily activities. This support helps to manage stress and anxiety and also significantly improves clinical outcomes [

20,

21,

22].

In this regard, preoperative educational programs targeted at patients and their families have demonstrated a significant impact on reducing anxiety and stress. Tools such as preoperative visits, telephone support, and technological intervention strategies have been effective not only in strengthening social support but also in humanizing the surgical experience [

11,

14,

16,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Conversely, the lack of a comprehensive approach to managing surgical patients can lead to feelings of isolation and stress. This is particularly concerning in areas such as the operating room, where technical priorities often overshadow the emotional dimension of care. Therefore, the need to adopt a humanized approach that considers both technical demands and the patient’s emotional well-being has been emphasized. This type of care not only improves postoperative outcomes but also strengthens the patient’s trust in their medical team and social environment [

17,

18].

In summary, this study focuses on analyzing the influence of perceived social support on the postoperative recovery of patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery. Through a multidisciplinary approach, this work aims to understand how social, emotional, and clinical factors interact to influence surgical outcomes, laying the groundwork for interventions that integrate both technical and humanized approaches.

1.2. Hypotheses

We hypothesized that patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery with a higher level of perceived social support would exhibit better postoperative outcomes, as characterized by a lower frequency of reinterventions, a reduced consumption of additional prescribed analgesics, decreased levels of healthcare assistance for pain management, and a lower incidence of local ocular infections.

In addition, we hypothesized that patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery with a higher level of perceived social support would demonstrate greater adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations.

1.3. Study Objectives

This study aims to describe and analyze the relationships between perceived social support (PSS), postoperative outcomes, and adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations in patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery.

The specific objectives of the study were as follows:

To describe sociodemographic variables.

To describe the levels of perceived social support.

To identify potential associations between PSS and the frequency of reinterventions.

To detect possible relationships between PSS and the demand for additional prescribed analgesics.

To examine the potential relationship between PSS and healthcare assistance for ocular pain management.

To assess the potential relationship between PSS and the incidence of local ocular infections.

To determine potential associations between PSS and adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study involving patients scheduled for retinal detachment surgery at the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil de Gran Canaria (CHUIMI) between November 2022 and June 2024.

2.1. Sample Size

The sample size was calculated based on an assumed event proportion of 25%, with a confidence interval margin of ±6% and an expected 10% dropout rate. Under these assumptions, 222 patients were required.

2.2. Study Population

A total of 226 patients were recruited using consecutive sampling in the ophthalmology department of CHUIMI between November 2022 and June 2024. These patients met the inclusion criteria; in total, 166 participants were present for the duration of the entire study follow-up. The final sample included 102 men (61.45%) and 64 women (38.55%), who were aged 21 to 84 years (mean: 65.4 years). This design ensured a broad and diverse representation of the hospital population while adhering to strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria required that participants:

Be aged 18 years or older.

Have an anesthetic risk classification of ASA ≤ 3.

Be scheduled for elective retinal detachment (RD) surgery.

Possess sufficient cognitive capacity to comprehend all study instructions.

Exclusion criteria included:

Patients under 18 years of age.

Those with moderate or severe cognitive impairment.

Patients with acute critical medical conditions.

Individuals lacking appropriate informed consent.

Those with severe head or cervical spine injuries.

Patients who had undergone recent surgeries in areas potentially affecting the study’s development and evaluation.

Patients were withdrawn if they met any exclusion criteria at any point or failed to respond to follow-up calls at 7, 15, or 30 days for data collection.

Participants meeting all inclusion criteria received detailed written information about the study’s objectives, procedures, implications, and scope. They were provided with a thoroughly developed informed consent form, which they were required to review carefully before signing to ensure voluntary, informed, and responsible participation.

This research received ethical approval from the Medicinal Research Ethics Committee of the province of Las Palmas.

2.3. Variables and Instrumentation

2.3.1. Predictor or Explanatory Variables (Independent):

Measures obtained from the social support questionnaires.

2.3.2. Criterion Variables (Dependent):

Reintervention.

Local ocular infection.

Administration of additional prescribed analgesia.

Healthcare assistance for pain management.

Adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations.

2.3.3. Confounding Variables:

Sociodemographic data.

Comorbidities.

Presence or absence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR).

Anesthetic risk classification (ASA) before surgery.

Surgical technique (if not standardized across all cases).

2.3.4. Variable Instrumentation

- 1.

Social Support

Social support was measured using the self-administered Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey, which assesses the availability of support when needed across various domains. This 19-item multidimensional tool, developed for patients in the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), demonstrates adequate validity and reliability for research purposes, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96.

- 2.

Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, living situation (alone or accompanied), marital status, and whether the patient was a primary caregiver (yes/no).

- 3.

Clinical and Postoperative Variables

Comorbidity: The Charlson Comorbidity Index is a validated tool that quantifies the impact of comorbidities on long-term clinical outcomes and mortality. This index assigns scores to 19 chronic diseases based on their severity, enabling a standardized risk assessment in research and clinical practice. Its versatility and applicability across populations make it a key resource for prognostic evaluation and risk stratification [

1]. The tool scores the following variables.

Reintervention: yes/no.

Local ocular infection: yes/no.

Administration of additional prescribed analgesia: required/not required.

Healthcare assistance for pain management: yes/no.

Adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations: yes/no.

Treatment adherence: This was measured using the Medication Adherence Questionnaire (MAQ), a brief and validated instrument designed to assess patients’ adherence to prescribed treatments. It consists of four dichotomous questions (yes/no) to identify behaviors related to compliance, such as forgetfulness, voluntary interruptions, or unapproved adjustments to the therapeutic regimen [

2].

Presence of PVR (proliferative vitreoretinopathy): yes/no.

Anesthetic risk: This was measured using the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) classification before surgery [

3]. This system categorizes patients into six levels, from ASA I (healthy) to ASA VI (brain death), providing a standardized preoperative assessment to estimate the risk of complications during surgical procedures.

2.4. Recruitment, Follow-Up, and Data Collection

The inclusion and data collection processes were generally standardized and subsequently refined to optimize the process. A specific area was designated for patients to complete the provided documentation in a calm and private environment.

Regarding patient selection, all procedures were thoroughly explained to participants at the start of their inclusion in the study. They were provided with informed consent forms for authorization and were allowed to contact the principal investigator at any time if needed.

2.4.1. Subject Inclusion

The surgical information nurse at CHUIMI, in coordination with the Head of the Ophthalmology Department and the Principal Investigator (PI), reviewed the weekly schedule every Monday to identify patients scheduled for retinal detachment surgery during the current and following weeks.

A member of the research team was designated to identify and include subjects in the study, ensuring a consistent recruitment pace. After receiving the surgical schedule from the previous week, patients were quickly identified using surgical records and planning. Following initial identification, patient medical records were reviewed to assess compliance with inclusion criteria.

If a patient did not meet the criteria, the investigator documented the reason for exclusion and archived the information, ensuring a daily record of patient reviews. For patients meeting the criteria, the investigator contacted the patient’s hospital unit and informed the care team about their inclusion the day before surgery.

2.4.2. Data Collection

A team of three collaborating researchers, already informed of the number of patients included in the study that week, personally explained the study in detail to the patients. They provided the study information sheet, invited participation, and obtained written informed consent. The questionnaires to be completed were then distributed, and additional information was recorded on a data collection sheet. The researchers addressed any questions that the patients had before consenting to participation.

Subsequently, the surgical information nurse, the PI, and a collaborating investigator contacted the patients to collect additional data, as outlined in the methodology. These data were added to the data collection sheets at 7, 15, and 30 days, corresponding to the scheduled ophthalmological follow-up appointments for this patient group at CHUIMI.

The coordinating team, with the assistance of a statistical advisor, ensured that the questionnaires and data collection sheets were correctly completed (

Appendix A). These forms were coded to preserve patient privacy and anonymity.

Finally, the data were transferred to an Excel file, which was securely stored by the PI and the coordinating team. This file was password-protected with restricted access for subsequent statistical analysis.

The patient data collection and follow-up sheet for days 7, 15, and 30 can be found in

Appendix A.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The mean, standard deviation, median, and 25th and 75th percentiles were calculated for quantitative variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess data normality. Frequency and percentage were calculated for qualitative variables. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare medians between two cohorts. Fisher’s exact test was applied to examine associations between qualitative variables, and Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to assess associations between discrete quantitative variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R Core Team 2024, version 4.3.3.

3. Results

3.1. Initial Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

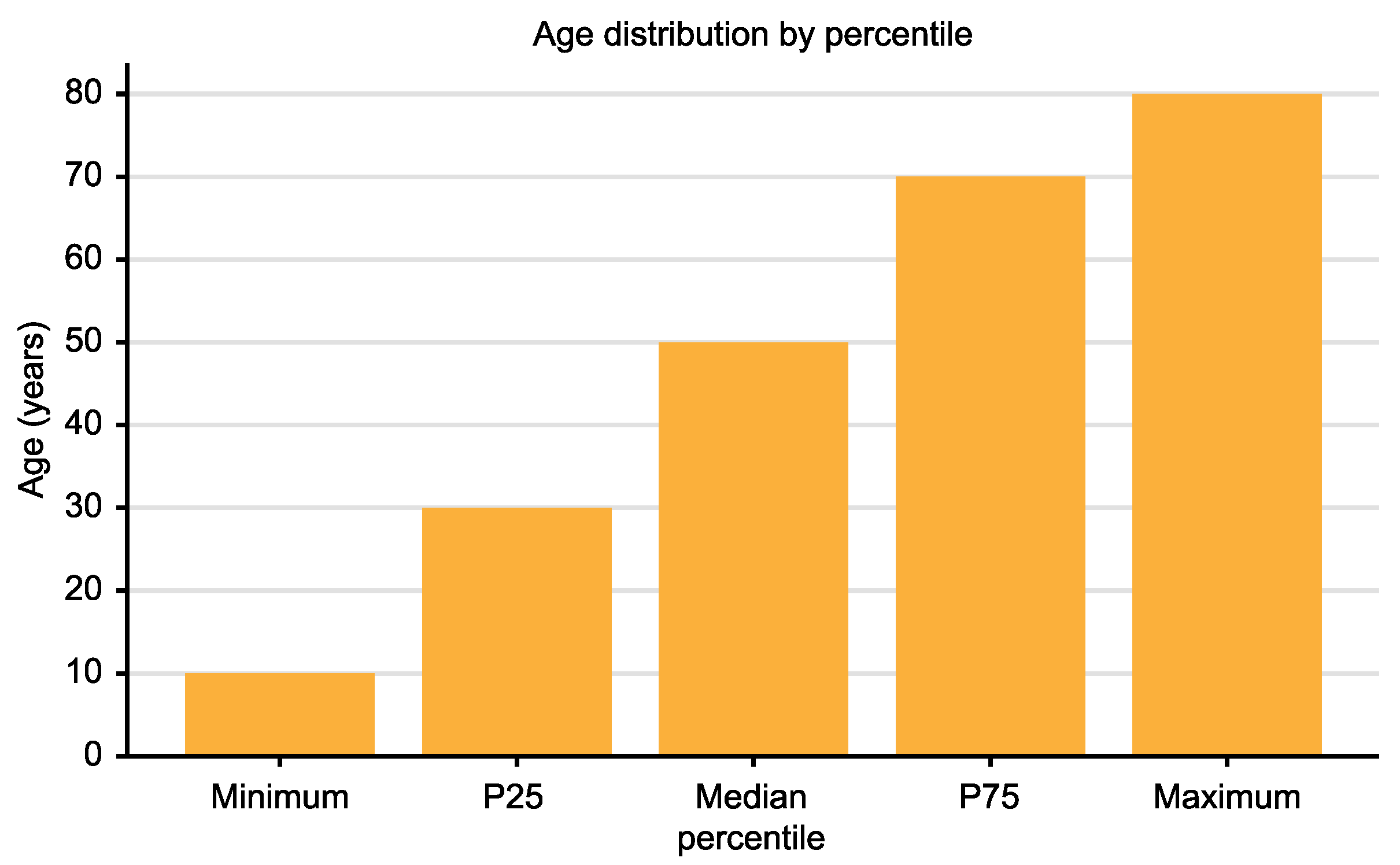

The study included 167 patients with an average age of 56.06 years (SD: 12.28), ranging from 21 to 84 years (

Figure 1). Of the participants, 61.45% were male and 38.55% were female. Regarding marital status, 59.04% were married, 24.1% were single, and 15.66% were widowed or divorced. Additionally, 80.12% lived with at least one other person.

Educational levels revealed that 62% had completed secondary education, 28% had attained university-level education, and 10% had only completed basic education. In terms of occupation, 45% were employed, 35% were retired, and 20% were unemployed or engaged in domestic work.

Clinically, patients had an average Charlson Comorbidity Index score of 0.5 (SD: 1.33). The most prevalent conditions were hypertension (15%), diabetes mellitus (10%), and cardiovascular diseases (5%). The preoperative anxiety and stress levels averaged 4.9 (SD: 3.01) and 5.09 (SD: 2.91), respectively. Participants reported an average social support network comprising 7.28 family members (SD: 8.27) and 7.17 friends (SD: 12.28).

3.2. Postoperative Results

The following trends were observed in postoperative variables.

The results of the MOS questionnaire, which measures different dimensions of perceived social support, are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 below. This questionnaire includes variables such as emotional/informational support, tangible support, positive interaction, and affective support, as well as the total average scores.

Table 2 reports the mean, standard deviation, median, and minimum and maximum ranges for each item evaluated, providing a detailed summary of the level of perceived social support among patients.

The data obtained through the MOS questionnaire demonstrate consistently high scores across all evaluated dimensions, reflecting a high level of perceived social support among participants. The mean scores for individual items ranged from 4.2 to 4.6, with relatively low standard deviations (range: 0.5–0.7), indicating little variability in responses. The median was 5.0 for the dimensions of positive interaction and emotional/informational support, and 4.0 for tangible and affective support. The ranges spanned from 2.5 to 5.0, with maximum scores commonly reported across most dimensions. The overall average score for the questionnaire was 4.43 (SD: 0.55), reinforcing the consistent perception of high social support.

3.2.1. Additional Analgesia

The need for additional analgesia showed a steady decline during the follow-up period. At 7 days, 46.43% of patients required analgesics (SD: 6.0), reflecting moderate initial variability in pain perception and management. By 15 days, this rate decreased to 20.72% (SD: 4.5), indicating significant improvement in postoperative pain control. By day 30, only 13.33% of patients required additional analgesia (SD: 3.2), suggesting that recovery was well advanced for most participants.

3.2.2. Predominant Pain

The type of pain predominantly experienced by patients evolved throughout the follow-up period. At 7 days, ocular pain was reported by 62.75% of patients (SD: 5.1), representing the main complaint in this early postoperative stage. This pain progressively diminished, while lumbar pain, initially less prevalent, became predominant by day 30, affecting 61.54% of patients (SD: 4.8). This shift may be associated with the postural positions required during recovery or biomechanical factors related to the surgical process.

3.2.3. Reinterventions

Reinterventions following retinal detachment (RD) surgery, specifically related to gas extraction and new retinal detachments, were infrequent. Over the follow-up period, a total of six cases were recorded—one case for gas extraction and one case for retinal detachment during each evaluation period (7, 15, and 30 days). These reinterventions accounted for only 3.6% of the total 167 patients evaluated, highlighting the effectiveness and safety of the surgical approach during the postoperative period.

This information emphasizes the low frequency of reinterventions after RD surgery within the follow-up period.

Reinterventions analyzed in relation to confounding variables showed consistent patterns over time. At 7 days, reinterventions were predominantly associated with a history of prior surgeries (70%) and an average Charlson Comorbidity Index of 0.9 (SD: 0.2), with a mean age of 60 years (SD: 7). At 15 days, reinterventions were linked to proliferative vitreoretinopathy (30%) and diabetes mellitus (40%), with an increased average age of 62 years (SD: 5) and a male predominance (65%). At 30 days, vitreoretinal adhesions (50%) and a Charlson Index above 1 (60%) were identified as relevant factors, with a mean age of 63 years (SD: 6) and frequent surgical histories among reintervened patients. These findings highlight how clinical and demographic variables contribute to the profile of reintervened patients in this context.

3.2.4. Postural Compliance

Adherence to postural recommendations was remarkably high throughout the follow-up period. At 7 days, compliance was 100% (SD: 0.0), reflecting total adherence at this early stage. At 15 days, adherence remained similarly high, with no significant variation. By 30 days, there was a slight decrease to 99.04% (SD: 0.5); this figure still indicates a strong commitment of the patients to medical instructions. These results underscore the effectiveness of preoperative education and follow-up by the medical or nursing team.

3.3. Inferential Statistics Related to Specific Objectives

Non-parametric statistical analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between the study variables. The key findings are summarized below.

Preoperative Stress and Anxiety:

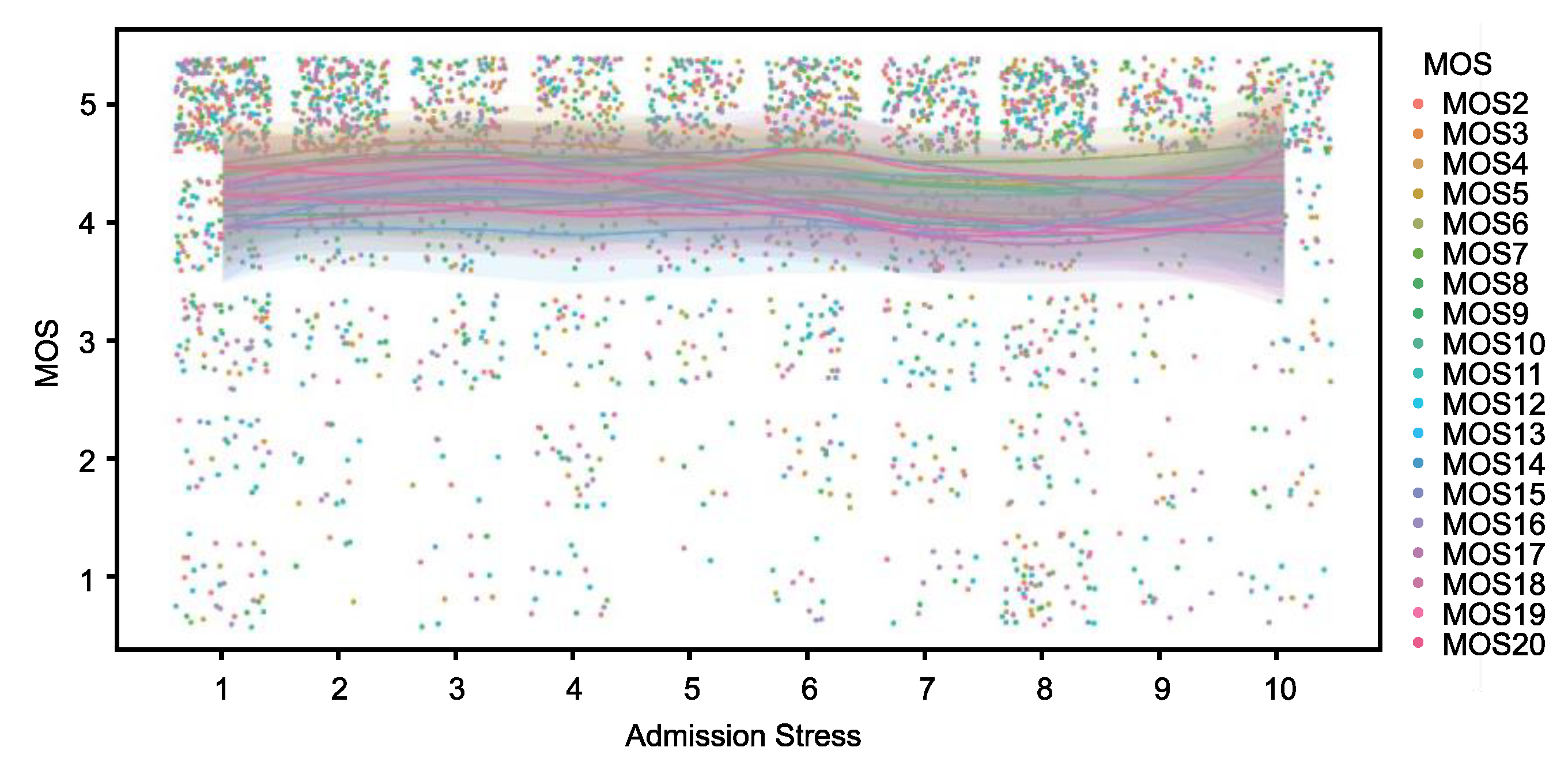

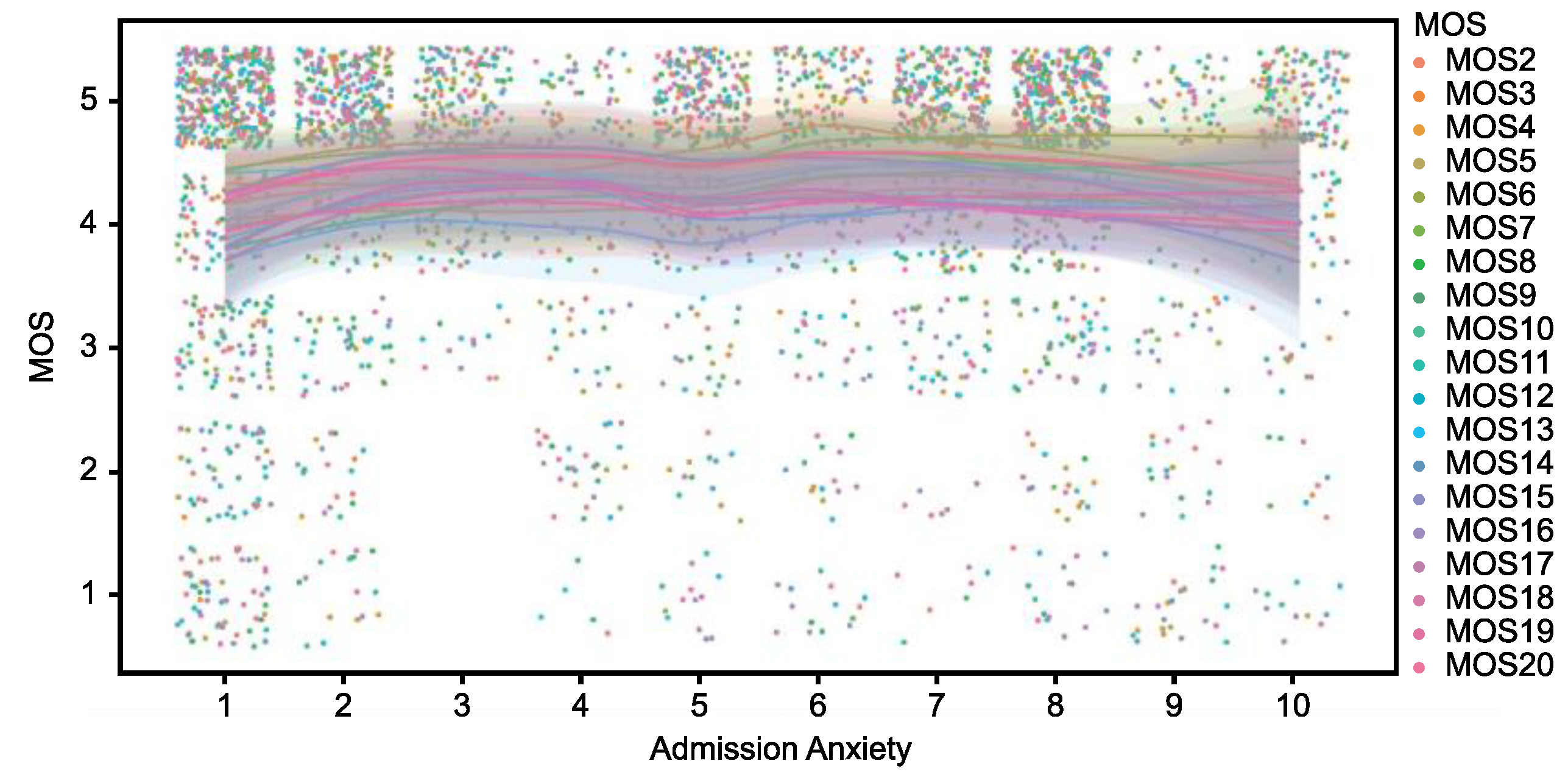

As shown in

Figure 2, the values of the perceived social support index (MOS) exhibit a homogeneous and concentrated distribution at high levels (values close to 5) across different levels of patient anxiety at admission. Similarly,

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between MOS and stress levels at admission, demonstrating a comparable pattern. Although a slight dispersion is observed in the lower MOS values among patients with higher stress levels, the overall values remain predominantly high. From an inferential perspective, the analyses performed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient did not identify statistically significant associations between the MOS scores and the variables of anxiety and stress at admission, with

p-values exceeding 0.05 in both cases. This result indicates the absence of a clear linear or monotonic relationship between these variables. Furthermore, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests, conducted to compare MOS scores between groups stratified by high and low levels of anxiety and stress, similarly failed to demonstrate statistically significant differences (

p > 0.05).

Perceived Social Support and Postoperative Outcomes:

Reinterventions: although patients without reinterventions exhibited higher scores on the MOS questionnaire (median: 4.44 vs. 4.09), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.087, Mann–Whitney U test).

Additional Analgesia: no significant differences were found in perceived social support between patients requiring additional analgesia and those who did not require it (p > 0.05, Mann–Whitney U test).

Postural Compliance: levels of perceived social support did not show a significant correlation with adherence to postoperative positioning recommendations (ρ = 0.12; p > 0.05).

Relationship Between Anxiety and Postoperative Pain: patients with higher levels of preoperative anxiety demonstrated a significantly greater need for additional analgesia at 7 days (median: 6 vs. 4; p = 0.041, Mann–Whitney U test).

Relationships Between Clinical Variables and Outcomes: Charlson Index and Reinterventions: A significant relationship was identified between a higher Charlson Index and increased reintervention rates at 30 days (p = 0.038, Mann–Whitney U test).

Age and Outcomes: no significant associations were found between age and reintervention rates at any of the follow-up intervals (ρ = 0.09 to 0.12; p > 0.05).

3.4. Variables with Statistically Significant Results

The statistical analysis revealed a significant association between elevated levels of preoperative anxiety and the need for additional analgesia at 7 days post operation (p = 0.041, Mann–Whitney U test). The median anxiety level was 6.0 (SD = 1.2) in patients requiring additional analgesia compared to 4.0 (SD = 1.5) in those who did not.

Additionally, a significant relationship was observed between a higher Charlson Index and reintervention rates at 30 days (p = 0.038, Mann–Whitney U test). Patients with a Charlson Index greater than 1 had a median score of 1.4 (SD = 0.3) compared to a median score of 0.9 (SD = 0.2) in those with an index of 1 or lower. Reintervention rates in this group were distributed as 15.4% in patients with a high index versus 5.3% in those with a low index.

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the relationship between perceived social support (PSS) and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for retinal detachment, which is a severe medical condition that represents a significant ophthalmological emergency [

1]. Although PSS scores were consistently high among participants, statistical analyses did not identify significant associations between PSS and general clinical variables such as reinterventions, the need for additional analgesia, local ocular infections, healthcare assistance, or postoperative compliance. These findings align with previous research suggesting that PSS influences emotional well-being and treatment adherence more than specific clinical outcomes [

2,

26].

4.1. Relevance of the Longitudinal Design

Unlike strictly cross-sectional studies, this design included detailed follow-up at 7, 15, and 30 days, allowing for the observation of dynamic changes in key variables such as pain management, adherence, and reintervention rates. This approach adds robustness to the analysis of postoperative outcomes, enabling the identification of temporal patterns that enrich the interpretation of results. However, periodic measurements also present challenges, such as the potential loss of information in specific subgroups due to the homogeneity of PSS scores [

27].

4.2. Preoperative Anxiety and Pain Management

One of the most significant findings was the relationship between elevated preoperative anxiety levels and a greater need for additional analgesia in the early postoperative days (

p = 0.041). This result supports prior evidence highlighting anxiety as a critical factor in postoperative pain perception, which is mediated by neuropsychological mechanisms that amplify pain responses [

1,

30]. Strategies such as preoperative emotional support, personalized education on recovery expectations, and tools like telephone follow-up could significantly reduce anxiety levels and, consequently, the need for analgesia [

2,

3,

4,

5,

27,

28,

29,

31].

4.3. Charlson Index and Reinterventions

The significant association between a high Charlson Index and increased reintervention rates at 30 days (

p = 0.038) underscores the importance of comorbidities in surgical outcomes. This finding, which is consistent with previous research [

6,

7], highlights the need for the comprehensive management of pre-existing conditions to optimize postoperative results. Although PSS did not show a direct correlation with reintervention rates, further research could explore how tangible or instrumental social support might mitigate the negative effects of comorbidities in more vulnerable patients [

8,

32,

33].

4.4. High Postoperative Adherence

Adherence to postoperative recommendations was exceptionally high (≥99%) across all evaluated intervals. This finding reinforces the effectiveness of preoperative education and close follow-up in promoting adherence behaviors, which is consistent with previous studies [

9,

28]. Although no significant correlations were observed between PSS and adherence, future studies could evaluate the impact of PSS in populations with lower social cohesion or a higher burden of comorbidities, where this factor might play a more prominent role [

34].

4.5. Predominant Pain and Postural Factors

The observed transition of predominant pain, from ocular to lumbar, reflects the influence of biomechanical factors and the postural demands associated with surgical management. Although PSS did not have a direct impact on pain perception, prior research suggests that emotional support may buffer the perception of chronic or recurrent pain in patients undergoing prolonged procedures [

2,

10,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Future investigations should focus on integrating postural ergonomics and targeted emotional interventions to mitigate such issues [

35].

4.6. Study Limitations

This study, despite its longitudinal design, has certain limitations. The homogeneity in PSS scores may have reduced the ability to detect significant associations within specific subgroups. Additionally, although the follow-up allowed for the identification of dynamic trends in the evaluated variables, the population analyzed was derived from a single center, which could limit the generalizability of the results. These limitations are mitigated by the richness of the longitudinal design, which provides a deeper understanding of postoperative outcomes in this population. The recruitment rate for the study was lower than expected due to circumstances related to the suspension of surgeries stemming from contingencies associated with operating room management issues during the COVID-19 pandemic [

36].

4.7. Future Perspectives

The future of comprehensive management for patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery should focus on integrated psychosocial interventions that optimize both clinical outcomes and quality of life. These strategies should combine stress management, tangible social support, and personalized education through innovative programs such as mobile applications for postoperative follow-up and interactive digital education platforms [

11]. These tools would not only reinforce adherence to medical recommendations but also mitigate the impact of preoperative anxiety and emotional isolation, providing continuous and tailored support to the individual needs of each patient.

Moreover, the implementation of integrated care models that combine advanced surgical techniques with continuous psychosocial support offers an opportunity to improve clinical outcomes, especially in patients with low social cohesion or high-risk factors. This multidimensional approach would address disparities in surgical outcomes, promoting more effective and sustained recovery [

12,

13,

14,

15,

37,

38].

Finally, long-term research should explore the impact of these psychosocial and educational strategies on patient functionality and well-being. Such studies would contribute to the design of more inclusive and equitable health policies, benefiting a broad population of patients with complex ophthalmological conditions and other clinical contexts [

39].

5. Conclusions

This study represents a novel and significant contribution to the field of ophthalmology by comprehensively exploring the relationship between perceived social support (PSS) and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing retinal detachment surgery. Although no significant associations were found between PSS and general clinical variables such as reintervention rates, adherence, or additional analgesia needs, the results underscore the importance of PSS in the emotional well-being of patients, highlighting its role in mitigating preoperative anxiety and its association with a greater need for analgesia in the early postoperative days (p = 0.041).

The high postoperative adherence observed (>99%) emphasizes the effectiveness of preoperative educational strategies, while the significant association between a high Charlson Index and increased reintervention rates at 30 days (p = 0.038) underscores the importance of comorbidities in surgical management. These findings highlight the need to integrate continuous psychosocial support with advanced surgical techniques to address both emotional and clinical factors.

As one of the first studies in ophthalmology to combine the analysis of clinical factors with the impact of social and emotional support on surgical outcomes, this research opens a promising path toward creating integrated care models that optimize both clinical results and patient quality of life. Its pioneering approach lays the groundwork for future research in more diverse populations and underscores the importance of considering psychosocial factors in designing personalized interventions that could transform postoperative management in the field of ophthalmology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

P.-R.C.-S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition, validation, data management and analysis, visualization, review, and editing. F.C.-L.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing. M.-D.M.-A.: conceptualization, validation, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, review, and editing. Y.F.-J.: validation, investigation, review, and editing. J.M.G.M.: methodology, software, validation, data management and analysis, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing. A.-M.D.-G.: validation, investigation, review, and editing. A.-D.T.-D.: validation, investigation, review, and editing. Y.S.-S.: validation, investigation, review, and editing. F.C.-L.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft preparation, review, and editing. J.-E.H.-R.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, data management and analysis, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, supervision, review, and editing. Please refer to the CRediT taxonomy for an explanation of the terms. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundación Canaria Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Canarias (FIISC), grant number ENF21/16. The APC was funded by the Fundación Canaria Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Canarias, grant number ENF21/16.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr Negrín (Province of Las Palmas) (protocol code 2019-231-1 and 19 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions that protect participant confidentiality. Data disclosure could compromise the integrity of personal information collected during the research. For further inquiries, interested parties may contact the corresponding authors, who will consider specific requests in compliance with ethical principles and applicable regulations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil (CHUIMI), particularly the Surgical Unit, the Major Ambulatory Surgery Unit, and the Ophthalmology Service, for their invaluable collaboration in facilitating the organizational aspects necessary to obtain the data required for this study. Their support was essential to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Data collection sheets: Admission—7 days—15 days—30 days.

References

- Rodríguez, A. Influence of social support on recovery in retinal detachment surgery. Retin. Stud. J. 2018, 34, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Santana, P.R. Influencia del Apoyo Social en la Ansiedad y el Estrés del Paciente Intervenido de Cirugía Endoscópica Nasosinusal. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castellón, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gironés-Muriel, J. Postoperative recovery in retinal detachment. Retin. Res. 2018, 5, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Muriel, A.G.; Segovia, A.C.; Slater, L.A.; Fernández, S. Revisión de programas hospitalarios para tratar la ansiedad quirúrgica infantil. Rev. Electr. AnestesiaR 2018, 10, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Guevara, S.L.; Villamizar Carvajal, B.; Rueda Díaz, L.J. Apoyo telefónico: Una estrategia de intervención para cuidadores familiares de personas con enfermedad crónica. Rev. Univ. Ind. Santander Salud 2011, 43, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente, M. Social support and adherence in medical recovery. Adherence Res. 2019, 8, 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ruran, P. Patient perceptions in retinal detachment management. Digit. Health Perspect. 2023, 9, 300–312. [Google Scholar]

- Guber, J.; Bentivoglio, M.; Valmaggia, C.; Lang, C.; Guber, I. Predictive risk factors for retinal redetachment following uncomplicated pars plana vitrectomy for primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałuszka, M.; Pojda-Wilczek, D.; Karska-Basta, I. Age-related macular or retinal degeneration? Medicina 2023, 59, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. E.; Fernengel, K.; Holcroft, C.; Gerald, K.; Marien, L. Meta-analysis of the associations between social support and health outcomes. Ann. Behav. Med. 1994, 16, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekecs, Z. Support in surgical experiences: A systematic review. Med. Support J. 2014, 10, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Kekecs, Z.; Jakubovits, E.; Varga, K.; Gombos, K. Effects of patient education and therapeutic suggestions on cataract surgery patients: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maqueda-Martínez, M.d.l.Á.; Ferrer-Márquez, M.; García-Redondo, M.; Rubio-Gil, F.; Reina-Duarte, Á.; Granero-Molina, J.; Correa-Casado, M.; Chica-Pérez, A. Effectiveness of a nurse-led telecare programme in the postoperative follow-up of bariatric surgery patients: A quasi-experimental study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droc, G.; Isac, S.; Nita, E.; Martac, C.; Jipa, M.; Mihai, D.I.; Cobilinschi, C.; Badea, A.-G.; Ojog, D.; Pavel, B. Postoperative cognitive impairment and pain perception after abdominal surgery—Could immersive virtual reality bring more? Medicina 2023, 59, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos M, Á.; Saiz, J.; López-Gómez, A.; Ugidos, C.; Muñoz, M. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haviland, J.; Sodergren, S.; Calman, L.; Corner, J.; Din, A.; Fenlon, D.; Grimmett, C.; Richardson, A.; Smith, P.W.; Winter, J.; et al. Social support following diagnosis and treatment for colorectal cancer. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 2276–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, R. Anxiety’s impact on surgical outcomes. Clin. Surg. Insights 2017, 5, 110–125. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón Márquez, T. Social context in post-surgical ophthalmologic recovery. J. Ophthalmic Recovery 2016, 6, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente Díaz, I.I.; Fernández, A.R.; Mateos, N.E. Measure of perceived social support during adolescence (APIK). Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2019, 9, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Visoiu, M.; Chelly, J.; Sadhasivam, S. Gaining insight into teenagers’ experiences of pain after laparoscopic surgeries: A prospective study. Children 2024, 11, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heluy de Castro, C.; Efigênia de Faria, T.; Felipe Cabañero, R.; Castelló Cabo, M. Humanización de la atención de enfermería en el quirófano. Index Enferm. 2004, 13, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeltzer, S.C.; Brunner, L.S.; Suddarth, D.S.; BBG, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Enfermería Médico-Quirúrgica; Editorial Médica Panamericana: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Retno, D. Educational strategies for anxiety in retinal surgery. J. Retinal Educ. 2022, 14, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Torrente-Sánchez, M.J.; Ferrer-Márquez, M.; Estébanez-Ferrero, B.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.M.; Ruiz-Muelle, A.; Ventura-Miranda, M.I.; Dobarrio-Sanz, I.; Granero-Molina, J. Social support for people with morbid obesity in a bariatric surgery programme: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages-Puigdemont, N.; Pharmaceutica, A. Métodos Para Medir la Adherencia Terapéutica. Ars Pharm. 2018. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/ars/article/view/7387 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Hurwitz, E.E.; Simon, M.; Vinta, S.R.; Zehm, C.F.; Shabot, S.M.; Minhajuddin, A.; Abouleish, A.E. Adding examples to the ASA-Physical Status Classification improves correct assignment to patients. Anesthesiology 2017, 126, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheta, A.; El-Fadl, R. Educational programs for retinal detachment surgery patients. Ophthalmic Educ. J. 2021, 15, 200–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, M. Social support and anxiety reduction. Anxiety Reduct. J. 2022, 8, 123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Baagil, H.; Baagil, H.; Gerbershagen, M.U. Preoperative anxiety impact on anaesthetic and analgesic use. Medicina 2023, 59, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, W.; Ki, S.; Suh, J.; Hwang, S.; Lee, J. Assessment of preoperative anxiety and influencing factors in patients undergoing elective surgery: An observational cross-sectional study. Medicina 2024, 60, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, J.E.; Díaz-Hernández, M.; Chacón-Ferrera, R.; Udaeta-Valdivieso, B. Influencia de la Visita Preoperatoria en la Evolución Postquirúrgica. Enferm. Cient. 1996, (174–175). Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=1184746 (accessed on 10 October 2017).

- Laguado Jaimes, E.; Yaruro Bacca, K.; Hernández Calderón, E.J. El cuidado de enfermería ante los procesos quirúrgicos estéticos. Enferm. Glob. 2015, 14, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livhits, M.; Mercado, C.; Yermilov, I.; Parikh, J.A.; Dutson, E.; Mehran, A.; Ko, C.Y.; Shekelle, P.G.; Gibbons, M.M. Is social support associated with greater weight loss after bariatric surgery? A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoudi, F. The impact of digital tools in ophthalmology. Ophthalmic Digit. Health 2021, 10, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, M.B.; Lam, M.; Gemeinhardt, C.; Houlihan, E.; Fitzsimmons, B.P.; Hodgson, Z.G. Social support in the post-abortion recovery room: Evidence from patients, support persons and nurses in a Vancouver clinic. Contraception 2011, 83, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekecs, Z.; Nagy, T.; Varga, K. The effectiveness of suggestive techniques in reducing postoperative side effects: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 119, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovic, M. Advances in retinal detachment surgery. Retina Surg. Adv. 2021, 19, 400–415. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, W.B.; Rosenbaum, E. The case for whole-person integrative care. Medicina 2021, 57, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).