Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

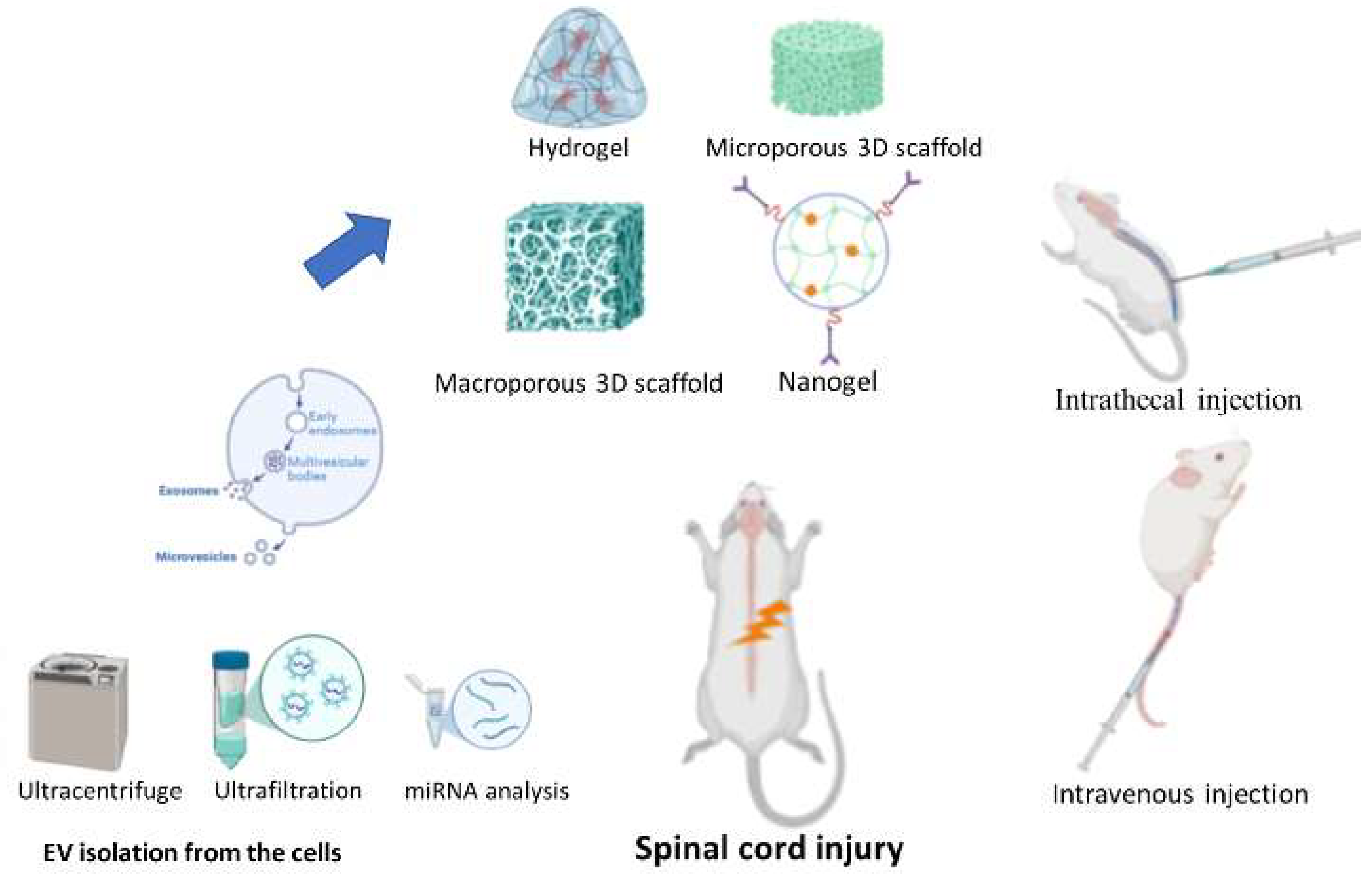

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

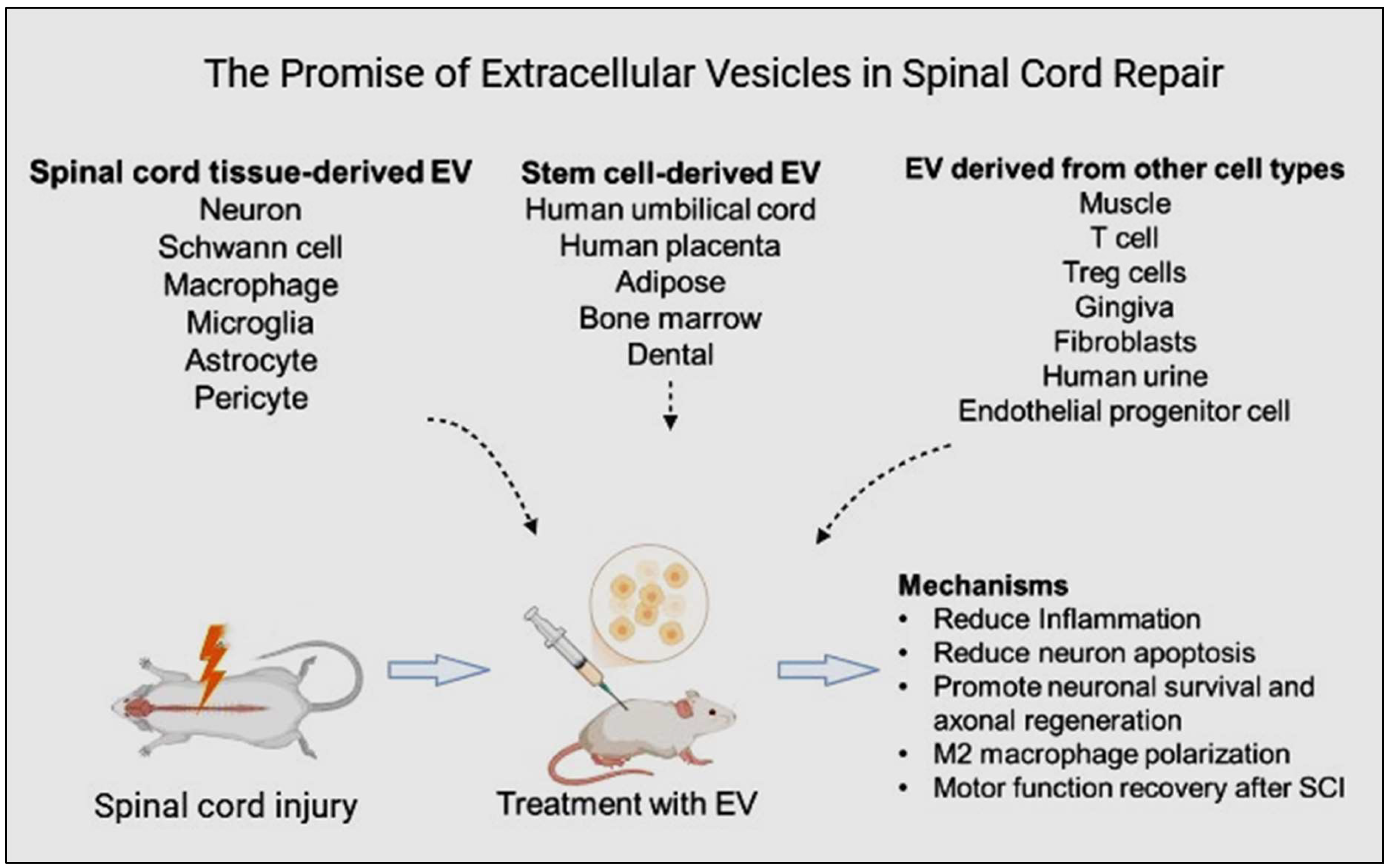

2. Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Mediators in Spinal Cord Injury

3. Extraction and Identification of Extracellular Vesicles

4. Routes of Administration and Biomaterial Approaches for Extracellular Vesicle Delivery in Spinal Cord Injury

5. Extracellular Vesicle miRNAs in Spinal Cord Injury Repair

6. Unlocking Therapeutic Potential: Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Spinal Cord Injury Recovery via Potential Signaling Pathways

6.1. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

6.2. Human Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

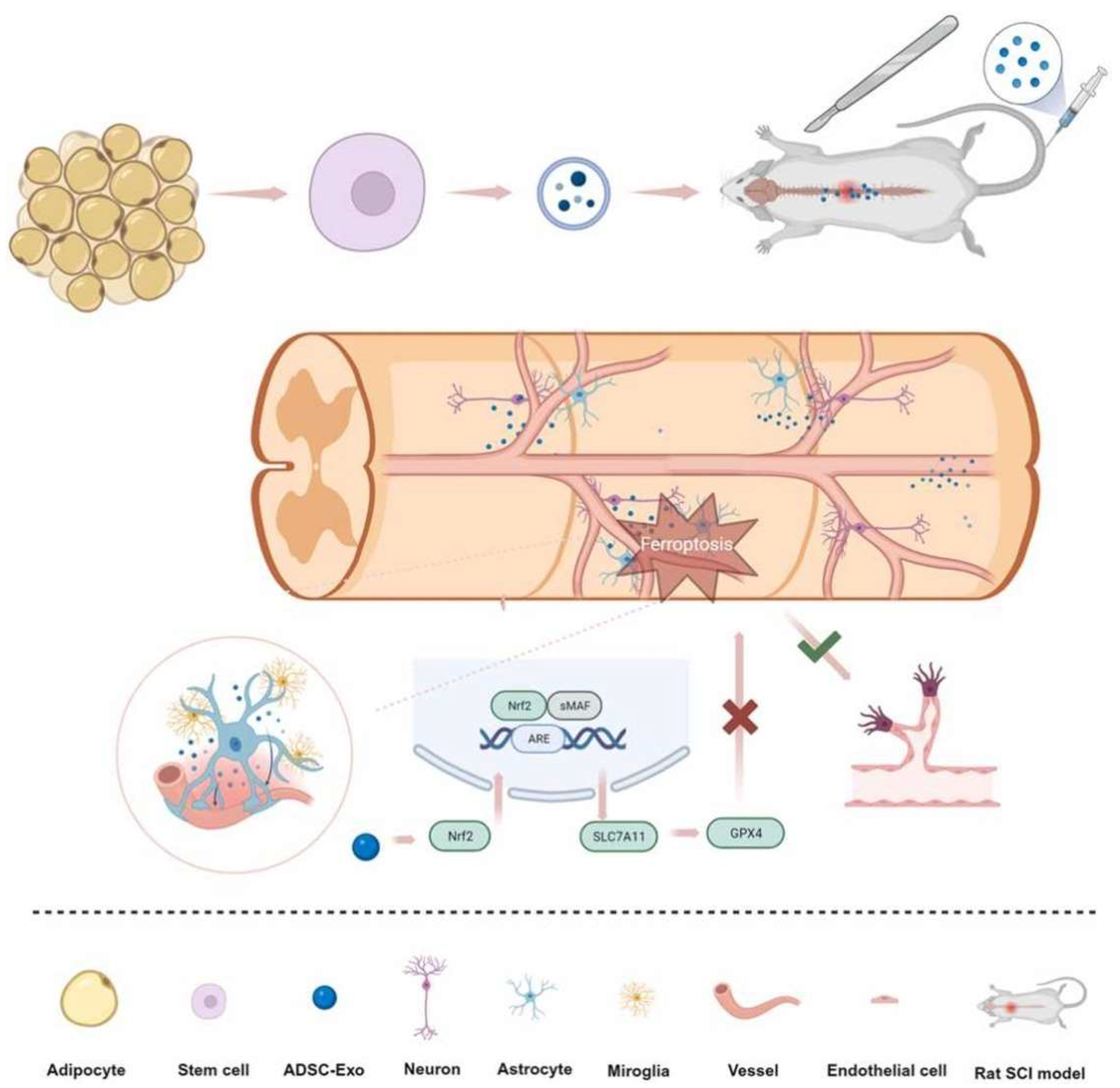

6.3. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

6.4. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

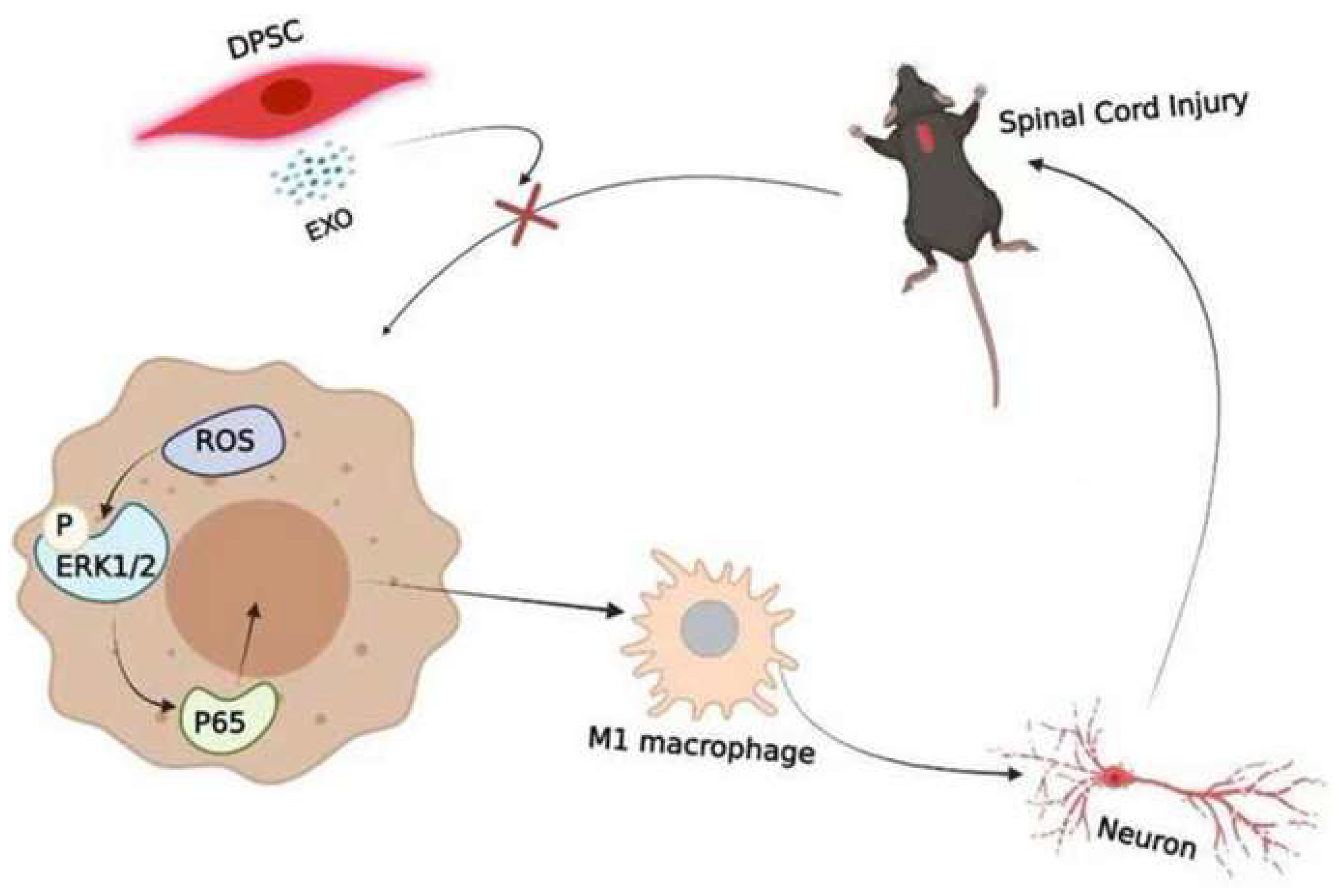

6.5. Dental Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

7. Exploring Therapeutic Potential: Spinal Cord Tissue-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Spinal Cord Injury

7.1. Neural Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

| Cell type/EV type | Injury model | Delivery route | Signal pathways | Therapeutic effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MG-EXs | Mice spinal cord contusive injury | Exogenous administration | p53/p21/CDK1 | Regulates neuronal apoptosis and promotes axonal growth | [88] |

| MG-EXs | Mouse spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 | Promotes functional recovery after SCI | [89] |

| MP-EXs | Mouse spinal cord injury | Locally administrated at the injury site | Wnt/β-Catenin | Promotes angiogenesis after SCI. | [90] |

| MP-EXs | Rat spinal cord contusion injury | Tail vein injection | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Attenuates anti-apoptosis suppresses BSCB disruption and functional recovery after SCI. | [91] |

| MP-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury |

Tail vein injection | miR-23a-3p/PTEN/PI3K/AKT axis | Phenotypic switch of macrophages in the immune microenvironment | [92] |

| SC-EXs | Mice spinal cord contusion injury | Tail vein injection | NF-κB/PI3K | Stimulates the expression of TLR2 in astrocytes after SCI and reduces the deposition of CSPGs. | [93] |

| SC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury |

Tail vein injection |

vincristine receptor B | Reduces apoptosis and promotes recovery of motor function | [94] |

| SC-EXs | Rat spinal cord contusion model | Tail vein injection |

SOCS3/STAT3 | Attenuates inflammation | [95] |

| PC-EXs | Mice spinal cord injury |

Tail vein injection |

PTEN/Akt | Improves endothelial barrier function under hypoxic conditions and protects endothelial cells | [96] |

| NSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury |

Tail vein injection | PTEN/AKT | Promotes functional recovery of SCI | [84] |

| NSC-EXs | Rat acute spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | miR-219a-2-3p/YY1 | Inhibits neuro-inflammation and promotes neuroprotection |

[97] |

| AC-EVs | Spinal cord injury | In vitro PC12 cell culture | Hippo pathwayMOB1-YAP axis | Promotes neurite elongation | [98] |

7.2. Schwann Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

7.3. Macrophage-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

7.4. Microglia-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

7.5. Astrocyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

7.6. Pericyte-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

8. Therapeutic Potential of Extracellular Vesicles from Other Cell Types in Spinal Cord Injury

9. Exploring the Role of Bioinformatics in Advancing Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Studies

9.1. Unveiling Therapeutic Pathways via microRNA Analysis in Extracellular Vesicles Transplanted Rodents

| Cell type/ EV type | Exosome Cargo | Delivery route | Injury model | Signaling pathways | Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HucMSC-EXs | miR-145-5p | Tail vein injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

TLR4/NF-κB | Regulates inflammation | [70] |

| HucMSC-EXs | miR-199a-3p/145-5p | Tail vein injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

NGF/TrkA | Promotes neuroprotective and functional recovery | [46] |

| MP-EXs | miR-155 | Tail injection | Mouse contusive spinal cord injury | NF-κB; miR-155/SOCS6/p65 axis | Ensures the transport network between macrophages and vascular endothelial cells after SCI | [140] |

| MSC-EXs | miR-338-5p | Tail vein injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

Cnr1/Rap1/Akt | Reduces apoptosis and promotes neuronal survival | [141] |

| ADSC-EXs | miR-133b | Tail intravenous injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

- | Promotes axonal regrowth and motor function recovery | [13] |

| BmMSC-EXs | miR-23b | Caudal vein injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

targeting TLR4 and inhibiting NF-κB pathway activation | Alleviates spinal cord injury | [69] |

| BmMSC-EXs | miR-544 | Intravenous injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

- | Reduces the number of apoptotic neurons | [142] |

| BmMSC-EXs | miR-125a | Intravenous injection | Rat spinal cord injury |

- | Promotes M2 macrophage polarization | [143] |

10. Clinical Studies

11. Navigating Future Insights and Anticipated Challenges

11.1. Future Insights

11.2. Challenges

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSC-EVs | Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles |

| MSC-EXs | Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| SCI | Spinal cord injury |

| miRNAs | Micro RNAs |

| BSCB | Blood spinal cord barrier |

| HucMSC-EXs | Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| hPMSC-EXs | Human placental mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| ADSC-EXs | Adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| BMSC-EXs | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| DSC-EXs | Dental mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes |

| NSC-EXs | Neural stem cell-derived exosomes |

| SC-EXs | Schwann cell-derived exosomes |

| MP-EXs | Macrophage-derived exosomes |

| MG-EXs | Microglia-derived exosomes |

| AC-EXs | Astrocyte-derived exosomes |

| PC-EXs | Pericyte-derived exosomes |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| Rsad2 | Radical SAM domain-containing 2 |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated protein x |

| TrkA | Tropomyosin receptor kinase A |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| IRAK1 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases 1 |

| TRAF6 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing-3 |

| NPCs | Neural pluripotent cells |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| CREB | cAMP-response element binding protein |

| OGD/R | Oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion |

| Nrf2/HO-1 | Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2/heme oxygenase |

| PI3K/Akt | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Protein kinase B |

| SLC7A11 | Solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| GPx4 | Glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| PTGDS | Prostaglandin D2 synthase |

| Rnd1 | Rho Family GTPase 1 |

| R-Ras | R-Ras gene |

| S1P | Sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| SIPR3 | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 |

| Sema3A | Semaphorin 3A |

| NRP1 | Neuropilin 1 |

| SOCS6 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 6 |

| Rap1 | Repressor/Activator Protein 1 |

| Cnr1 | Cannabinoid receptor gene |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| JUN | Jun proto-oncogene or enhancer-binding protein |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 2 |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| RELA | v-rel avian reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene homolog A |

| CCl3 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 3 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| SHH | Sonic hedgehog |

| TIMP2 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| Cdc42 | Cell division control protein 42 homolog |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PKB also known as AKT | Protein kinase B |

| PI3Ks | Phosphoinositide 3-kinases |

| DUSPs | dual-specificity phosphatases |

References

- Poongodi, R.; Yang, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yang, K.D.; Chen, H.-Z.; Chu, T.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Lin, H.-C.; Cheng, J.-K. , Stem cell exosome-loaded Gelfoam improves locomotor dysfunction and neuropathic pain in a rat model of spinal cord injury, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2024, 15, 143. 15.

- Hu, X.; Xu, W.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, X.; Huang, R.; Ma, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, L. , Spinal cord injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 245. 8.

- Cao, S.; Hou, G.; Meng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xie, L.; Shi, B. , Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking-Based Investigation of Potential Targets of Astragalus membranaceus and Angelica sinensis Compound Acting on Spinal Cord Injury, Disease Markers 2022 (2022) 2141882.

- Yan, L.; Fu, J.; Dong, X.; Chen, B.; Hong, H.; Cui, Z. , Identification of hub genes in the subacute spinal cord injury in rats, BMC Neuroscience 2022, 23, 51. 23.

- Li, Y.; Shen, P.-P.; Wang, B. , Induced pluripotent stem cell technology for spinal cord injury: a promising alternative therapy, Neural Regeneration Research 2021, 16,.

- Tran, A.P.; Warren, P.M.; Silver, J. , New insights into glial scar formation after spinal cord injury, Cell and Tissue Research 387 (2022) 319+.

- Liu, W.; Rong, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, X.; Ji, C.; Jiang, D.; Gong, F.; Li, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, S.; Kong, F.; Gu, C.; Fan, J.; Cai, W. , Exosome-shuttled miR-216a-5p from hypoxic preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells repair traumatic spinal cord injury by shifting microglial M1/M2 polarization, Journal of Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 47. 17.

- Khalatbary, A.R. , Stem cell-derived exosomes as a cell free therapy against spinal cord injury, Tissue and Cell 71 (2021) 101559.

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, X.; Qiu, J.; Xin, D.; Li, T.; Chu, X.; Yuan, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D. , Exosomes Derived From Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibit Complement Activation In Rats With Spinal Cord Injury, Drug Des Devel Ther 13 (2019) 3693-3704.

- Ren, Z.; Qi, Y.; Sun, S.; Tao, Y.; Shi, R. , Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Hope for Spinal Cord Injury Repair, Stem Cells and Development 2020, 29, 1467–1478.

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Niazi, V.; Hussen, B.M.; Omrani, M.D.; Taheri, M.; Basiri, A. , The Emerging Role of Exosomes in the Treatment of Human Disorders With a Special Focus on Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9 (2021).

- Huang, J.-H.; Xu, Y.; Yin, X.-M.; Lin, F.-Y. , Exosomes Derived from miR-126-modified MSCs Promote Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis and Attenuate Apoptosis after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats, Neuroscience 424 (2020) 133-145.

- Li, D.; Zhang, P.; Yao, X.; Li, H.; Shen, H.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Lu, X. , Exosomes Derived From miR-133b-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury, Frontiers in Neuroscience 12 (2018).

- Tang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Ren, J.; Ding, H.; Shang, J.; Wang, M.; Wei, Z.; Feng, S. , Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes loaded into a composite conduit promote functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury in rats, Neural Regeneration Research 2024, 19,.

- Liu, J.-S.; Du, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, X.-Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.-L. , Exosomal miR-451 from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells attenuates burn-induced acute lung injury, Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2019, 82,.

- Morita, T.; Sasaki, M.; Kataoka-Sasaki, Y.; Nakazaki, M.; Nagahama, H.; Oka, S.; Oshigiri, T.; Takebayashi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Kocsis, J.D.; Honmou, O. , Intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells promotes functional recovery in a model of chronic spinal cord injury, Neuroscience 335 (2016) 221-231.

- Lv, L.; Sheng, C.; Zhou, Y. , Extracellular vesicles as a novel therapeutic tool for cell-free regenerative medicine in oral rehabilitation, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 2020, 47, 29–54.

- Kiyotake, E.A.; Martin, M.D.; Detamore, M.S. , Regenerative rehabilitation with conductive biomaterials for spinal cord injury, Acta Biomaterialia 139 (2022) 43-64.

- El Andaloussi, S.; Mäger, I.; Breakefield, X.O.; Wood, M.J.A. , Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities, Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 347–357.

- He, C.; Zheng, S.; Luo, Y.; Wang, B. , Exosome Theranostics: Biology and Translational Medicine, Theranostics 2018, 8, 237–255.

- Liu, W.-Z.; Ma, Z.-J.; Li, J.-R.; Kang, X.-W. , Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes: therapeutic opportunities and challenges for spinal cord injury, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 102. 12.

- Wu, S.-C.; Kuo, P.-J.; Rau, C.-S.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-J.; Lu, T.-H.; Lin, C.-W.; Tsai, C.-W.; Hsieh, C.-H. , Subpopulations of exosomes purified via different exosomal markers carry different microRNA contents, International Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 18, 1058–1066.

- Hade, M.D.; Suire, C.N.; Suo, Z. , Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Applications in Regenerative Medicine, Cells, 2021.

- López-Leal, R.; Díaz-Viraqué, F.; Catalán, R.J.; Saquel, C.; Enright, A.; Iraola, G.; Court, F.A. , Schwann cell reprogramming into repair cells increases miRNA-21 expression in exosomes promoting axonal growth, Journal of Cell Science 2020, 133, jcs239004.

- Yang, X.-X.; Sun, C.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.-L. , New insight into isolation, identification techniques and medical applications of exosomes, Journal of Controlled Release 308 (2019) 119-129.

- Akbar, A.; Malekian, F.; Baghban, N.; Kodam, S.P.; Ullah, M. , Methodologies to Isolate and Purify Clinical Grade Extracellular Vesicles for Medical Applications, Cells, 2022.

- Sidhom, K.; Obi, P.O.; Saleem, A. , A Review of Exosomal Isolation Methods: Is Size Exclusion Chromatography the Best Option?, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020.

- Huang, J.-H.; Fu, C.-H.; Xu, Y.; Yin, X.-M.; Cao, Y.; Lin, F.-Y. , Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Epidural Fat-Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuate NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Improve Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury, Neurochemical Research 2020, 45, 760–771.

- Zeng, J.; Gu, C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X. , Engineering of M2 Macrophages-Derived Exosomes via Click Chemistry for Spinal Cord Injury Repair, Advanced Healthcare Materials 2023, 12, 2203391.

- Chen, K.; Yu, W.; Zheng, G.; Xu, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Yue, Z.; Yuan, W.; Hu, B.; Chen, H. , Biomaterial-based regenerative therapeutic strategies for spinal cord injury, NPG Asia Materials 2024, 16, 5. 16.

- Liu, S.; Xie, Y.-Y.; Wang, B. , Role and prospects of regenerative biomaterials in the repair of spinal cord injury, Neural Regeneration Research 2019, 14,.

- Tabesh, H.; Amoabediny, G.; Nik, N.S.; Heydari, M.; Yosefifard, M.; Siadat, S.O.R.; Mottaghy, K. , The role of biodegradable engineered scaffolds seeded with Schwann cells for spinal cord regeneration, Neurochemistry International 2009, 54, 73–83.

- Poongodi, R.; Chen, Y.-L.; Yang, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-H.; Yang, K.D.; Lin, H.-C.; Cheng, J.-K. , Bio-Scaffolds as Cell or Exosome Carriers for Nerve Injury Repair, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021.

- Zhang, L.; Fan, C.; Hao, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dai, J. , NSCs Migration Promoted and Drug Delivered Exosomes-Collagen Scaffold via a Bio-Specific Peptide for One-Step Spinal Cord Injury Repair, Advanced Healthcare Materials 2021, 10, 2001896.

- Hsu, J.M.; Shiue, S.J.; Yang, K.D.; Shiue, H.S.; Hung, Y.W.; Pannuru, P.; Poongodi, R.; Lin, H.Y.; Cheng, J.K. , Locally Applied Stem Cell Exosome-Scaffold Attenuates Nerve Injury-Induced Pain in Rats, Journal of pain research 13 (2020) 3257-3268.

- Fan, B.; Chopp, M.; Zhang, Z.G.; Liu, X.S. , Emerging Roles of microRNAs as Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets for Diabetic Neuropathy, Frontiers in Neurology 11 (2020).

- Gebert, L.F.R.; MacRae, I.J. , Regulation of microRNA function in animals, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2019, 20, 21–37.

- Treiber, T.; Treiber, N.; Meister, G. , Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2019, 20, 5–20.

- Xia, S.; Xu, C.; Liu, F.; Chen, G. , Development of microRNA-based therapeutics for central nervous system diseases, European Journal of Pharmacology 956 (2023) 175956.

- Wang, N.; He, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Tian, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B.; Rong, L. , Integrated analysis of competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks in subacute stage of spinal cord injury, Gene 726 (2020) 144171.

- Ding, S.Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.N.; Duan, F.X.; Chen, Y.Q.; Shi, Y.J.; Hu, J.G.; Lu, H.Z. , Identification of serum exosomal microRNAs in acute spinal cord injured rats, Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019, 244, 1149–1161.

- Paim, L.R.; Schreiber, R.; de Rossi, G.; Matos-Souza, J.R.; Costa, E.S.A.A.; Calegari, D.R.; Cheng, S.; Marques, F.Z.; Sposito, A.C.; Gorla, J.I.; Cliquet, A., Jr. ; Nadruz, W., Jr..; Circulating microRNAs; Risk, V., and Physical Activity in Spinal Cord-Injured Subjects, J Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 845–852.

- Wang, Y.; Yi, H.; Song, Y. , miRNA Therapy in Laboratory Models of Acute Spinal Cord Injury in Rodents: A Meta-analysis, Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2023, 43, 1147–1161.

- Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Gu, C.; Waqas, A.; Chen, L. , Emerging Exosomes and Exosomal MiRNAs in Spinal Cord Injury, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9 (2021).

- Kang, J.; Guo, Y. , Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Exosomes Promote Neurological Function Recovery in a Rat Spinal Cord Injury Model, Neurochemical Research 2022, 47, 1532–1540.

- Wang, Y.; Lai, X.; Wu, D.; Liu, B.; Wang, N.; Rong, L. , Umbilical mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes facilitate spinal cord functional recovery through the miR-199a-3p/145-5p-mediated NGF/TrkA signaling pathway in rats, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 117. 12.

- Sun, G.; Li, G.; Li, D.; Huang, W.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Y.; Wang, B. , hucMSC derived exosomes promote functional recovery in spinal cord injury mice via attenuating inflammation, Materials Science and Engineering: C 89 (2018) 194-204.

- Gao, X.; Gao, L.-F.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Kong, X.-Q.; Jia, S.; Meng, C.-Y. , Huc-MSCs-derived exosomes attenuate neuropathic pain by inhibiting activation of the TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway in the spinal microglia by targeting Rsad2, International Immunopharmacology 114 (2023) 109505.

- Xiao, X.; Li, W.; Rong, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, H.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. , Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles facilitate the repair of spinal cord injury via the miR-29b-3p/PTEN/Akt/mTOR axis, Cell Death Discovery 2021, 7, 212. 7.

- Zhang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zhang, R.; Xie, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, F.; Han, J.; Sun, H.; Ouyang, Q.; Hua, S.; Lv, B.; Hua, T.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, X. , Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-146a-5p reduces microglial-mediated neuroinflammation via suppression of the IRAK1/TRAF6 signaling pathway after ischemic stroke, Aging 2021, 13, 3060–3079.

- Che, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J. , Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes attenuate neuroinflammation and oxidative stress through the NRF2/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway, CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics n/a(n/a) (2023).

- Zhou, W.; Silva, M.; Feng, C.; Zhao, S.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Zhong, J.; Zheng, W. , Exosomes derived from human placental mesenchymal stem cells enhanced the recovery of spinal cord injury by activating endogenous neurogenesis, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 174. 12.

- Cheshmi, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Akbari, M.; Nasiry, D.; Rezapour-Nasrabad, R.; Bagheri, M.; Abouhamzeh, B.; Poorhassan, M.; Mirhoseini, M.; Mokhtari, H.; Akbari, E.; Raoofi, A. , Human Placental Mesenchymal Stem Cell-derived Exosomes in Combination with Hyperbaric Oxygen Synergistically Promote Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats, Neurotoxicity Research 2023, 41, 431–445.

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, F.; Wang, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, H.; Qin, Z.; Tao, T. , Human PMSCs-derived small extracellular vesicles alleviate neuropathic pain through miR-26a-5p/Wnt5a in SNI mice model, Journal of Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 221.

- Harrell, C.R.; Volarevic, V.; Djonov, V.; Volarevic, A. , Therapeutic Potential of Exosomes Derived from Adipose Tissue-Sourced Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Neural and Retinal Diseases, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022.

- Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Lin, T.; Zhou, D. , Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Enhance PC12 Cell Function through the Activation of the PI3K/AKT Pathway, Stem cells international 2021 (2021) 2229477-2229477.

- Li, M.; Lei, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, B.; Yu, C.; Yuan, Y.; Fang, D.; Xin, Z.; Guan, R. , Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells exert therapeutic effect in a rat model of cavernous nerves injury, Andrology 2018, 6, 927–935.

- Liang, Y.; Wu, J.-H.; Zhu, J.-H.; Yang, H. , Exosomes Secreted by Hypoxia–Pre-conditioned Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reduce Neuronal Apoptosis in Rats with Spinal Cord Injury, Journal of Neurotrauma 2022, 39, 701–714.

- Luo, Y.; He, Y.-Z.; Wang, Y.-F.; Xu, Y.-X.; Yang, L. , Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell exosomes ameliorate spinal cord injury in rats by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and regulating microglial polarization, Folia Neuropathologica 2023, 61, 326–335.

- Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Q.; Yang, E.; Zhang, B.; Qian, Y.; Lian, X.; Xu, J. , ADSC-Exos enhance functional recovery after spinal cord injury by inhibiting ferroptosis and promoting the survival and function of endothelial cells through the NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 172 (2024) 116225.

- Sheng, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, J.; He, R.; Lu, H.; Wu, T.; Duan, C.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. , Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Accelerate Functional Recovery After Spinal Cord Injury by Promoting the Phagocytosis of Macrophages to Clean Myelin Debris, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9 (2021).

- Lankford, K.L.; Arroyo, E.J.; Nazimek, K.; Bryniarski, K.; Askenase, P.W.; Kocsis, J.D. , Intravenously delivered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes target M2-type macrophages in the injured spinal cord, PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0190358.

- Ni, H.; Yang, S.; Siaw-Debrah, F.; Hu, J.; Wu, K.; He, Z.; Yang, J.; Pan, S.; Lin, X.; Ye, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Jin, K.; Zhuge, Q.; Huang, L. , Exosomes Derived From Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Early Inflammatory Responses Following Traumatic Brain Injury, Frontiers in Neuroscience 13 (2019).

- Li, C.; Qin, T.; Liu, Y.; Wen, H.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Z.; Peng, W.; Lu, H.; Duan, C.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. , Microglia-Derived Exosomal microRNA-151-3p Enhances Functional Healing After Spinal Cord Injury by Attenuating Neuronal Apoptosis via Regulating the p53/p21/CDK1 Signaling Pathway, Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9 (2022).

- Wang, L.; Pei, S.; Han, L.; Guo, B.; Li, Y.; Duan, R.; Yao, Y.; Xue, B.; Chen, X.; Jia, Y. , Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Reduce A1 Astrocytes via Downregulation of Phosphorylated NFκB P65 Subunit in Spinal Cord Injury, Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 50, 1535–1559.

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Lu, Y.; Mao, T.; Gu, Y.; Ju, D.; Dong, C. , Exosomes combined with biomaterials in the treatment of spinal cord injury, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 11 (2023).

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Gong, F.; Rong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, T.; Jiang, T.; Yang, S.; Yin, G.; Chen, J.; Fan, J.; Cai, W. , Exosomes Derived from Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cells Repair Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury by Suppressing the Activation of A1 Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes, Journal of Neurotrauma 2018, 36, 469–484.

- Fan, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, X.; Zheng, L.; Zou, Y.; Wen, H.; Guan, P.; Lu, F.; Luo, Y.; Tan, G.; Yu, P.; Chen, D.; Deng, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ning, C. , Exosomes-Loaded Electroconductive Hydrogel Synergistically Promotes Tissue Repair after Spinal Cord Injury via Immunoregulation and Enhancement of Myelinated Axon Growth, Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2105586.

- Nie, H.; Jiang, Z. , Bone mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles deliver microRNA-23b to alleviate spinal cord injury by targeting toll-like receptor TLR4 and inhibiting NF-κB pathway activation, Bioengineered 2021, 12, 8157–8172.

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J. , Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes containing miR-145-5p reduce inflammation in spinal cord injury by regulating the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, Cell Cycle 2021, 20, 993–1009.

- Jia, Y.; Yang, J.; Lu, T.; Pu, X.; Chen, Q.; Ji, L.; Luo, C. , Repair of spinal cord injury in rats via exosomes from bone mesenchymal stem cells requires sonic hedgehog, Regenerative Therapy 18 (2021) 309-315.

- Xin, W.; Qiang, S.; Jianing, D.; Jiaming, L.; Fangqi, L.; Bin, C.; Yuanyuan, C.; Guowang, Z.; Jianguang, X.; Xiaofeng, L. , Human Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes Attenuate Blood–Spinal Cord Barrier Disruption via the TIMP2/MMP Pathway After Acute Spinal Cord Injury, Molecular Neurobiology 2021, 58, 6490–6504.

- Li, S.; Liao, X.; He, Y.; Chen, R.; Zheng, W.V.; Tang, M.; Guo, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, S.; Sun, J. , Exosomes derived from NGF-overexpressing bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell sheet promote spinal cord injury repair in a mouse model, Neurochemistry International 157 (2022) 105339.

- Mai, Z.; Chen, H.; Ye, Y.; Hu, Z.; Sun, W.; Cui, L.; Zhao, X. , Translational and Clinical Applications of Dental Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes, Frontiers in Genetics 12 (2021).

- Swanson, W.B.; Zhang, Z.; Xiu, K.; Gong, T.; Eberle, M.; Wang, Z.; Ma, P.X. , Scaffolds with controlled release of pro-mineralization exosomes to promote craniofacial bone healing without cell transplantation, Acta Biomaterialia 118 (2020) 215-232.

- Liu, C.; Hu, F.; Jiao, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, J.; You, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. , Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes suppress M1 macrophage polarization through the ROS-MAPK-NFκB P65 signaling pathway after spinal cord injury, Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 65. 20.

- Li, S.; Luo, L.; He, Y.; Li, R.; Xiang, Y.; Xing, Z.; Li, Y.; Albashari, A.A.; Liao, X.; Zhang, K.; Gao, L.; Ye, Q. , Dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviate cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion injury through suppressing inflammatory response, Cell Proliferation 2021, 54, e13093.

- Shao, M.; Jin, M.; Xu, S.; Zheng, C.; Zhu, W.; Ma, X.; Lv, F. , Exosomes from Long Noncoding RNA-Gm37494-ADSCs Repair Spinal Cord Injury via Shifting Microglial M1/M2 Polarization, Inflammation 2020, 43, 1536–1547.

- Li, C.; Jiao, G.; Wu, W.; Wang, H.; Ren, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y. , Exosomes from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Inhibit Neuronal Apoptosis and Promote Motor Function Recovery via the Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway, Cell Transplantation 2019, 28, 1373–1383.

- Wang, S.; Bao, L.; Fu, W.; Deng, L.; Ran, J. , Protective effect of exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on rats with diabetic nephropathy and its possible mechanism, Am J Transl Res 2021, 13, 6423–6430.

- Fukuoka, T.; Kato, A.; Hirano, M.; Ohka, F.; Aoki, K.; Awaya, T.; Adilijiang, A.; Sachi, M.; Tanahashi, K.; Yamaguchi, J.; Motomura, K.; Shimizu, H.; Nagashima, Y.; Ando, R.; Wakabayashi, T.; Lee-Liu, D.; Larrain, J.; Nishimura, Y.; Natsume, A. , Neurod4 converts endogenous neural stem cells to neurons with synaptic formation after spinal cord injury, iScience 2021, 24, 102074.

- Deng, M.; Xie, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, J.; Ming, J.; Yang, J. , Mash-1 modified neural stem cells transplantation promotes neural stem cells differentiation into neurons to further improve locomotor functional recovery in spinal cord injury rats, Gene 781 (2021) 145528.

- Li, W.-Y.; Zhu, Q.-B.; Jin, L.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.-Y.; Hu, X.-Y. , Exosomes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells protect neuronal function under ischemic conditions, Neural Regeneration Research 2021, 16,.

- Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Lai, X.; Xia, Q. , Exosomes Derived from Nerve Stem Cells Loaded with FTY720 Promote the Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury in Rats by PTEN/AKT Signal Pathway, Journal of Immunology Research 2021 (2021) 8100298.

- Zhang, L.; Han, P. , Neural stem cell-derived exosomes suppress neuronal cell apoptosis by activating autophagy via miR-374-5p/STK-4 axis in spinal cord injury, Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions 2022, 22, 411–421.

- Zhong, D.; Cao, Y.; Li, C.-J.; Li, M.; Rong, Z.-J.; Jiang, L.; Guo, Z.; Lu, H.-B.; Hu, J.-Z. , Neural stem cell-derived exosomes facilitate spinal cord functional recovery after injury by promoting angiogenesis, Experimental Biology and Medicine 2020, 245, 54–65.

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Xu, X.; Sun, H.-T.; Zheng, H.-M.; Zhang, J.-L.; Wang, H.-H.; Fang, J.-W.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Huang, L.-L.; Song, Z.-W.; Liu, J.-B. , Neuron-Derived Exosomes Promote the Recovery of Spinal Cord Injury by Modulating Nerve Cells in the Cellular Microenvironment of the Lesion Area, Molecular Neurobiology 2023, 60, 4502–4516.

- Li, C.; Qin, T.; Zhao, J.; He, R.; Wen, H.; Duan, C.; Lu, H.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. , Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosome-Educated Macrophages Promote Functional Healing After Spinal Cord Injury, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 15 (2021).

- Peng, W.; Wan, L.; Luo, Z.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, T.; Lu, H.; Hu, J. , Microglia-Derived Exosomes Improve Spinal Cord Functional Recovery after Injury via Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Promoting the Survival and Function of Endothelia Cells, Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021 (2021) 1695087.

- Luo, Z.; Peng, W.; Xu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J. , Exosomal OTULIN from M2 macrophages promotes the recovery of spinal cord injuries via stimulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway-mediated vascular regeneration, Acta Biomaterialia 136 (2021) 519-532.

- Zhang, B.; Lin, F.; Dong, J.; Liu, J.; Ding, Z.; Xu, J. , Peripheral Macrophage-derived Exosomes promote repair after Spinal Cord Injury by inducing Local Anti-inflammatory type Microglial Polarization via Increasing Autophagy, International Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 17, 1339–1352.

- Peng, P.; Yu, H.; Xing, C.; Tao, B.; Li, C.; Huang, J.; Ning, G.; Zhang, B.; Feng, S. , Exosomes-mediated phenotypic switch of macrophages in the immune microenvironment after spinal cord injury, Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 144 (2021) 112311.

- Pan, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, F.; Lv, Z.; Zhu, S.; Shao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ning, G.; Feng, S. , Increasing toll-like receptor 2 on astrocytes induced by Schwann cell-derived exosomes promotes recovery by inhibiting CSPGs deposition after spinal cord injury, Journal of Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 172.

- Pan, D.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, W.; Wei, Z.; Yang, F.; Guo, Z.; Ning, G.; Feng, S. , Autophagy induced by Schwann cell-derived exosomes promotes recovery after spinal cord injury in rats, Biotechnology Letters 2022, 44, 129–142.

- Ren, J.; Zhu, B.; Gu, G.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Song, X.; Wei, Z.; Feng, S. , Schwann cell-derived exosomes containing MFG-E8 modify macrophage/microglial polarization for attenuating inflammation via the SOCS3/STAT3 pathway after spinal cord injury, Cell Death & Disease 2023, 14, 70. 14.

- Yuan, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, P.; Jing, Y.; Yao, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xiu, R. , Exosomes Derived From Pericytes Improve Microcirculation and Protect Blood–Spinal Cord Barrier After Spinal Cord Injury in Mice, Frontiers in Neuroscience 13 (2019).

- Ma, K.; Xu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, F.; Liang, H.; Sun, H.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R.; Chen, X. , Insulin-like growth factor-1 enhances neuroprotective effects of neural stem cell exosomes after spinal cord injury via an miR-219a-2-3p/YY1 mechanism, Aging 2019, 11, 12278–12294.

- Sun, H.; Cao, X.; Gong, A.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Lv, B.; Li, Z.; Guan, S.; Lu, L.; Yin, G. , Extracellular vesicles derived from astrocytes facilitated neurite elongation by activating the Hippo pathway, Experimental Cell Research 2022, 411, 112937.

- Wong, F.C.; Ye, L.; Demir, I.E.; Kahlert, C. , Schwann cell-derived exosomes: Janus-faced mediators of regeneration and disease, Glia 2022, 70, 20–34.

- Ghosh, M.; Pearse, D.D. , Schwann Cell-Derived Exosomal Vesicles: A Promising Therapy for the Injured Spinal Cord, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023.

- Zhu, B.; Gu, G.; Ren, J.; Song, X.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Huo, Y.; Wang, H.; Jin, L.; Feng, S.; Wei, Z. , Schwann Cell-Derived Exosomes and Methylprednisolone Composite Patch for Spinal Cord Injury Repair, ACS Nano 2023, 17, 22928–22943.

- Jessen, K.R.; Mirsky, R.; Lloyd, A.C. , Schwann Cells: Development and Role in Nerve Repair, Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2015, 7, a020487.

- Ching, R.C.; Wiberg, M.; Kingham, P.J. , Schwann cell-like differentiated adipose stem cells promote neurite outgrowth via secreted exosomes and RNA transfer, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2018, 9, 266. 9.

- Cong, M.; Shen, M.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; He, Q.; Shi, H.; Ding, F. , Improvement of sensory neuron growth and survival via negatively regulating PTEN by miR-21-5p-contained small extracellular vesicles from skin precursor-derived Schwann cells, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 80. 12.

- Hyung S, K.J.; CJ, Y.; HS, J.; JW, H. , Neuroprotective Effect of Glial Cell-Derived Exosomes on Neurons, Immunotherapy (Los Angel) 5:156 (2019).

- Huang, Z.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Shi, Y.; Liang, J.; Zhao, L. , Baicalin-loaded macrophage-derived exosomes ameliorate ischemic brain injury via the antioxidative pathway, Materials Science and Engineering: C 126 (2021) 112123.

- Gao, Z.-S.; Zhang, C.-J.; Xia, N.; Tian, H.; Li, D.-Y.; Lin, J.-Q.; Mei, X.-F.; Wu, C. , Berberine-loaded M2 macrophage-derived exosomes for spinal cord injury therapy, Acta Biomaterialia 126 (2021) 211-223.

- Huang, J.-H.; He, H.; Chen, Y.-N.; Liu, Z.; Romani, M.D.; Xu, Z.-Y.; Xu, Y.; Lin, F.-Y. , Exosomes derived from M2 Macrophages Improve Angiogenesis and Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury through HIF-1α/VEGF Axis, Brain Sciences, 2022.

- Poulen, G.; Aloy, E.; Bringuier, C.M.; Mestre-Francés, N.; Artus, E.V.F.; Cardoso, M.; Perez, J.-C.; Goze-Bac, C.; Boukhaddaoui, H.; Lonjon, N.; Gerber, Y.N.; Perrin, F.E. , Inhibiting microglia proliferation after spinal cord injury improves recovery in mice and nonhuman primates, Theranostics 2021, 11, 8640–8659.

- Ge, X.; Guo, M.; Hu, T.; Li, W.; Huang, S.; Yin, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhu, L.; Kang, C.; Jiang, R.; Lei, P.; Zhang, J. , Increased Microglial Exosomal miR-124-3p Alleviates Neurodegeneration and Improves Cognitive Outcome after rmTBI, Molecular Therapy 2020, 28, 503–522.

- Zhang, J.; Hu, D.; Li, L.; Qu, D.; Shi, W.; Xie, L.; Jiang, Q.; Li, H.; Yu, T.; Qi, C.; Fu, H. , M2 Microglia-derived Exosomes Promote Spinal Cord Injury Recovery in Mice by Alleviating A1 Astrocyte Activation, Molecular Neurobiology (2024).

- Endo, F.; Kasai, A.; Soto, J.S.; Yu, X.; Qu, Z.; Hashimoto, H.; Gradinaru, V.; Kawaguchi, R.; Khakh, B.S. , Molecular basis of astrocyte diversity and morphology across the CNS in health and disease, Science 378(6619) eadc9020.

- Escartin, C.; Galea, E.; Lakatos, A.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Petzold, G.C.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Steinhäuser, C.; Volterra, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Agarwal, A.; Allen, N.J.; Araque, A.; Barbeito, L.; Barzilai, A.; Bergles, D.E.; Bonvento, G.; Butt, A.M.; Chen, W.-T.; Cohen-Salmon, M.; Cunningham, C.; Deneen, B.; De Strooper, B.; Díaz-Castro, B.; Farina, C.; Freeman, M.; Gallo, V.; Goldman, J.E.; Goldman, S.A.; Götz, M.; Gutiérrez, A.; Haydon, P.G.; Heiland, D.H.; Hol, E.M.; Holt, M.G.; Iino, M.; Kastanenka, K.V.; Kettenmann, H.; Khakh, B.S.; Koizumi, S.; Lee, C.J.; Liddelow, S.A.; MacVicar, B.A.; Magistretti, P.; Messing, A.; Mishra, A.; Molofsky, A.V.; Murai, K.K.; Norris, C.M.; Okada, S.; Oliet, S.H.R.; Oliveira, J.F.; Panatier, A.; Parpura, V.; Pekna, M.; Pekny, M.; Pellerin, L.; Perea, G.; Pérez-Nievas, B.G.; Pfrieger, F.W.; Poskanzer, K.E.; Quintana, F.J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Riquelme-Perez, M.; Robel, S.; Rose, C.R.; Rothstein, J.D.; Rouach, N.; Rowitch, D.H.; Semyanov, A.; Sirko, S.; Sontheimer, H.; Swanson, R.A.; Vitorica, J.; Wanner, I.-B.; Wood, L.B.; Wu, J.; Zheng, B.; Zimmer, E.R.; Zorec, R.; Sofroniew, M.V.; Verkhratsky, A. ; Reactive astrocyte nomenclature; definitions; future directions; Neuroscience, N.2021) 312-325.

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; Wilton, D.K.; Frouin, A.; Napier, B.A.; Panicker, N.; Kumar, M.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Rowitch, D.H.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M.; Stevens, B.; Barres, B.A. , Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia, Nature 2017, 541, 481–487.

- Hira, K.; Ueno, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Miyamoto, N.; Yamashiro, K.; Inaba, T.; Urabe, T.; Okano, H.; Hattori, N. , Astrocyte-Derived Exosomes Treated With a Semaphorin 3A Inhibitor Enhance Stroke Recovery via Prostaglandin D2 Synthase, Stroke 2018, 49, 2483–2494.

- Lu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Du, R.; Ji, J.; Xu, T.; Yang, C.; Chen, X. , Astrocyte-derived sEVs alleviate fibrosis and promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury in rats, International Immunopharmacology 113 (2022) 109322.

- Tang, H.-B.; Jiang, X.-J.; Wang, C.; Liu, S.-C. , S1P/S1PR3 signaling mediated proliferation of pericytes via Ras/pERK pathway and CAY10444 had beneficial effects on spinal cord injury, Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2018, 498, 830–836.

- Zeng, X.; Bian, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Ren, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Tegeleqi, B.; He, G.; Guan, M.; Gao, Z.; Huang, C.; Liu, J. , Muscle-derived stem cell exosomes with overexpressed miR-214 promote the regeneration and repair of rat sciatic nerve after crush injury to activate the JAK2/STAT3 pathway by targeting PTEN, Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 16 (2023).

- Azoulay-Alfaguter, I.; Mor, A. , Proteomic analysis of human T cell-derived exosomes reveals differential RAS/MAPK signaling, European Journal of Immunology 2018, 48, 1915–1917.

- Rao, F.; Zhang, D.; Fang, T.; Lu, C.; Wang, B.; Ding, X.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pi, W.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, P. , Exosomes from Human Gingiva-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Combined with Biodegradable Chitin Conduits Promote Rat Sciatic Nerve Regeneration, Stem Cells International 2019 (2019) 2546367.

- Tassew, N.G.; Charish, J.; Shabanzadeh, A.P.; Luga, V.; Harada, H.; Farhani, N.; D’Onofrio, P.; Choi, B.; Ellabban, A.; Nickerson, P.E.B.; Wallace, V.A.; Koeberle, P.D.; Wrana, J.L.; Monnier, P.P. , Exosomes Mediate Mobilization of Autocrine Wnt10b to Promote Axonal Regeneration in the Injured CNS, Cell Reports 2017, 20, 99–111.

- He, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Ju, D.; Mao, T.; Lu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Qi, L.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Dong, C. , A decellularized spinal cord extracellular matrix-gel/GelMA hydrogel three-dimensional composite scaffold promotes recovery from spinal cord injury via synergism with human menstrual blood-derived stem cells, Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10, 5753–5764.

- Cao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Xie, H.; Lu, H.; Hu, J. , Local delivery of USC-derived exosomes harboring ANGPTL3 enhances spinal cord functional recovery after injury by promoting angiogenesis, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2021, 12, 20. 12.

- Kong, G.; Xiong, W.; Li, C.; Xiao, C.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, J.; Fan, J.; Jin, Z. , Treg cells-derived exosomes promote blood-spinal cord barrier repair and motor function recovery after spinal cord injury by delivering miR-2861, Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 364.

- Gao, P.; Yi, J.; Chen, W.; Gu, J.; Miao, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Li, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, S.; Wu, M.; Yin, G.; Chen, J. , Pericyte-derived exosomal miR-210 improves mitochondrial function and inhibits lipid peroxidation in vascular endothelial cells after traumatic spinal cord injury by activating JAK1/STAT3 signaling pathway, Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 452.

- Mao, Q.; Nguyen, P.D.; Shanti, R.M.; Shi, S.; Shakoori, P.; Zhang, Q.; Le, A.D. , Gingiva-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Extracellular Vesicles Activate Schwann Cell Repair Phenotype and Promote Nerve Regeneration, Tissue Engineering Part A 2018, 25, 887–900.

- Yuan, F.; Peng, W.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Huang, T.; Shi, C.; Ding, Y.; Li, C.; Qin, T.; Xie, S.; Zhu, F.; Lu, H.; Huang, J.; Hu, J. , Endothelial progenitor cell-derived exosomes promote anti-inflammatory macrophages via SOCS3/JAK2/STAT3 axis and improve the outcome of spinal cord injury, Journal of Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 156.

- Gauthier, J.; Vincent, A.T.; Charette, S.J.; Derome, N. , A brief history of bioinformatics, Briefings in Bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1981–1996.

- Li, J.-Z.; Fan, B.-Y.; Sun, T.; Wang, X.-X.; Li, J.-J.; Zhang, J.-P.; Gu, G.-J.; Shen, W.-Y.; Liu, D.-R.; Wei, Z.-J.; Feng, S.-Q. , Bioinformatics analysis of ferroptosis in spinal cord injury, Neural Regeneration Research 2023, 18,.

- Hu, R.; Shi, M.; Xu, H.; Wu, X.; He, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, L.; Ma, R. , Integrated bioinformatics analysis identifies the effects of Sema3A/NRP1 signaling in oligodendrocytes after spinal cord injury in rats, PeerJ 10 (2022) e13856.

- He, X.; Fan, L.; Wu, Z.; He, J.; Cheng, B. , Gene expression profiles reveal key pathways and genes associated with neuropathic pain in patients with spinal cord injury, Mol Med Rep 2017, 15, 2120–2128.

- Zhang, G.; Yang, P. , Bioinformatics Genes and Pathway Analysis for Chronic Neuropathic Pain after Spinal Cord Injury, BioMed Research International 2017 (2017) 6423021.

- Chavda, V.P.; Pandya, A.; Kumar, L.; Raval, N.; Vora, L.K.; Pulakkat, S.; Patravale, V. ; Salwa; Duo, Y., Ed.; Tang, B.Z., Exosome nanovesicles: A potential carrier for therapeutic delivery, Nano Today 49 (2023) 101771. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Guha, L.; Kumar, H. , From hope to healing: Exploring the therapeutic potential of exosomes in spinal cord injury, Extracellular Vesicle 3 (2024) 100044.

- Cheng, L.-F.; You, C.-Q.; Peng, C.; Ren, J.-J.; Guo, K.; Liu, T.-L. , Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a new drug carrier for the treatment of spinal cord injury: A review, Chinese Journal of Traumatology 2024, 27, 134–146.

- Ren, Z.W.; Zhou, J.G.; Xiong, Z.K.; Zhu, F.Z.; Guo, X.D. , Effect of exosomes derived from MiR-133b-modified ADSCs on the recovery of neurological function after SCI, European review for medical and pharmacological sciences 2019, 23, 52–60.

- Zhang, Y.; Chopp, M.; Liu, X.S.; Katakowski, M.; Wang, X.; Tian, X.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Z.G. , Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Axonal Growth of Cortical Neurons, Molecular Neurobiology 2017, 54, 2659–2673.

- Huang, S.; Ge, X.; Yu, J.; Han, Z.; Yin, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Lei, P. , Increased miR-124-3p in microglial exosomes following traumatic brain injury inhibits neuronal inflammation and contributes to neurite outgrowth via their transfer into neurons, The FASEB Journal 2018, 32, 512–528.

- Li, H.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Yang, A.; Lyu, F.; Dong, Y. , Exosomal miR-423-5p Derived from Cerebrospinal Fluid Pulsation Stress-Stimulated Osteoblasts Improves Angiogenesis of Endothelial Cells via DUSP8/ERK1/2 Signaling Pathway, Stem Cells International 2024 (2024) 5512423.

- Ge, X.; Tang, P.; Rong, Y.; Jiang, D.; Lu, X.; Ji, C.; Wang, J.; Huang, C.; Duan, A.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Fan, J.; Liu, W.; Yin, G.; Cai, W. , Exosomal miR-155 from M1-polarized macrophages promotes EndoMT and impairs mitochondrial function via activating NF-κB signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells after traumatic spinal cord injury, Redox Biology 41 (2021) 101932.

- Zhang, A.; Bai, Z.; Yi, W.; Hu, Z.; Hao, J. , Overexpression of miR-338-5p in exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells provides neuroprotective effects by the Cnr1/Rap1/Akt pathway after spinal cord injury in rats, Neuroscience Letters 761 (2021) 136124.

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, B.; Wang, C. , Exosomes derived from miR-544-modified mesenchymal stem cells promote recovery after spinal cord injury, Archives of Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 126, 369–375.

- Chang, Q.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhuo, H.; Zhao, G. , Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal microRNA-125a promotes M2 macrophage polarization in spinal cord injury by downregulating IRF5, Brain Research Bulletin 170 (2021) 199-210.

- Zhou, S.; Ding, F.; Gu, X. , Non-coding RNAs as Emerging Regulators of Neural Injury Responses and Regeneration, Neuroscience Bulletin 2016, 32, 253–264.

- Yang, W.; Sun, P. , Promoting functions of microRNA-29a/199B in neurological recovery in rats with spinal cord injury through inhibition of the RGMA/STAT3 axis, Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 2020, 15, 427.

- Jiang, D.; Gong, F.; Ge, X.; Lv, C.; Huang, C.; Feng, S.; Zhou, Z.; Rong, Y.; Wang, J.; Ji, C.; Chen, J.; Zhao, W.; Fan, J.; Liu, W.; Cai, W. , Neuron-derived exosomes-transmitted miR-124-3p protect traumatically injured spinal cord by suppressing the activation of neurotoxic microglia and astrocytes, Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2020, 18, 105.

- Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, J. , miR-223 Inhibits the Polarization and Recruitment of Macrophages via NLRP3/IL-1β Pathway to Meliorate Neuropathic Pain, Pain Research and Management 2021 (2021) 6674028.

- Bai, G.; Jiang, L.; Meng, P.; Li, J.; Han, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. , LncRNA Neat1 Promotes Regeneration after Spinal Cord Injury by Targeting miR-29b, Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2021, 71, 1174–1184.

- Huang, W.; Lin, M.; Yang, C.; Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Gao, J.; Yu, X. , Rat Bone Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Loaded with miR-494 Promoting Neurofilament Regeneration and Behavioral Function Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury, Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2021 (2021) 1634917.

- Malvandi, A.M.; Rastegar-moghaddam, S.H.; Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan, S.; Lombardi, G.; Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan, A.; Mohammadipour, A. , Targeting miR-21 in spinal cord injuries: a game-changer? , Molecular Medicine 2022, 28, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Ma, T.; Chang, L.; Chen, X.; Xia, G.; Li, C.; Liu, H. ; Correlation between miRNA-124; miRNA-544a, and TNF-α levels in acute spinal cord injury, Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 779–783.

- Cui, Y.; Yin, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, B.; Yang, B.; Xu, B.; Song, H.; Zou, Y.; Ma, X.; Dai, J. , LncRNA Neat1 mediates miR-124-induced activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in spinal cord neural progenitor cells, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2019, 10, 400. 10.

- Wang, T.; Li, B.; Yuan, X.; Cui, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Xiu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, F.; Guo, X.; Zhao, X.; Chen, X. , MiR-20a Plays a Key Regulatory Role in the Repair of Spinal Cord Dorsal Column Lesion via PDZ-RhoGEF/RhoA/GAP43 Axis in Rat, Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 2019, 39, 87–98.

- Danilov, C.A.; Gu, Y.; Punj, V.; Wu, Z.; Steward, O.; Schönthal, A.H.; Tahara, S.M.; Hofman, F.M.; Chen, T.C. , Intravenous delivery of microRNA-133b along with Argonaute-2 enhances spinal cord recovery following cervical contusion in mice, The Spine Journal 2020, 20, 1138–1151.

- Shao, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhao, H.; Li, D. , Mesenchymal Stem Cell Derived Exosomes Suppress Neuronal Cell Ferroptosis Via lncGm36569/miR-5627-5p/FSP1 Axis in Acute Spinal Cord Injury, Stem Cell Reviews and Reports 2022, 18, 1127–1142.

- Akhlaghpasand, M.; Tavanaei, R.; Hosseinpoor, M.; Yazdani, K.O.; Soleimani, A.; Zoshk, M.Y.; Soleimani, M.; Chamanara, M.; Ghorbani, M.; Deylami, M.; Zali, A.; Heidari, R.; Oraee-Yazdani, S. , Safety and potential effects of intrathecal injection of allogeneic human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in complete subacute spinal cord injury: a first-in-human, single-arm, open-label, phase I clinical trial, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2024, 15, 264. 15.

- Ye, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, G.; Shu, F.; Fan, K.; Wang, D. , Advancements in engineered exosomes for wound repair: current research and future perspectives, Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 11 (2023).

- Lotfy, A.; AboQuella, N.M.; Wang, H. , Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials, Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2023, 14, 66. 14.

| Cell type/ EV type | Animal model | Delivery route | Signaling pathways | Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HucMSC-EXs | Rat chronic constriction injury | Intrathecal injection | TLR2/MyD88/NF-κB | Attenuates neuropathic pain | [48] |

| HucMSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | Wnt/β-catenin | Mitigates apoptosis downregulates inflammatory factors and promotes angiogenesis and axonal growth | [45,46] |

| HucMSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Intravenous administration | BCL2/Bax and Wnt/β-catenin | Productive effects of SCI | [45] |

| HucMSC-EXs | LPS-treated mouse model | Tail vein injection | NRF2/NF-κB/NLRP3 | Reduces oxidative stress and neuroinflammation | [51] |

| HPMSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | MEK/ERK/cAMP-CREB | Endogenous neurogenesis activation enhances recovery from spinal cord injury | [52] |

| ADSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | Nrf2/HO-1 | Prevents inflammation in M1 microglia and spinal cord tissues | [59] |

| ADSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 | Prevents ferroptosis and promotes recovery of vascular and neural functions | [60] |

| ADMSC -EXs | Mice spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | NF-κB light-chain enhancer (related to STAT activity) to inhibit NF-κB | Repairs SCI via Shifting microglial M1/M2 Polarization | [78] |

| BmMSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | Wnt/β-catenin | Inhibits neuronal apoptosis and promotes motor function recovery | [79] |

| BmMSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Intravenous administration | Wnt/β-catenin | Plays crucial roles in SCI | [45] |

| Bone MSC-EXs | Mice spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | TLR4–NF-κB and activating the PI3K–AKT | Exosome-shuttled miR-216a-5p from hypoxic pre-conditioned MSC repairs traumatic SCI | [7] |

| BMSC-SHH-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Intravenous injection | Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) | Promotes neuron recovery and inhibits astrocyte activation | [71] |

| BmMSC-EXs | Rat acute spinal cord injury | Intravenous injection | TIMP2)/MMP | Therapeutics intervention in acute SCI | [72] |

| BmMSC-EXs | Rat diabetic nephropathy model | Tail vein injection | JAK2/STAT3 | Protective effects of diabetic nephropathy and its possible mechanism | [80] |

| miR-216a-5p was enriched in MSC-derived exosomes | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | TLR4/NF-κB/PI3K/AKT | Repairs traumatic SCI by suppressing the activation of A1 neurotoxic reactive astrocytes | [67] |

| DSC-EXs | Rat spinal cord injury | Tail vein injection | ROS-MAPK-NF-κB P65 | Suppresses M1 macrophage polarization | [76] |

| DSC-EXs | Mice transient middle cerebral artery occlusion injury | Tail vein injection | HMGB1/TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB | Promotes anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects | [77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).