Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

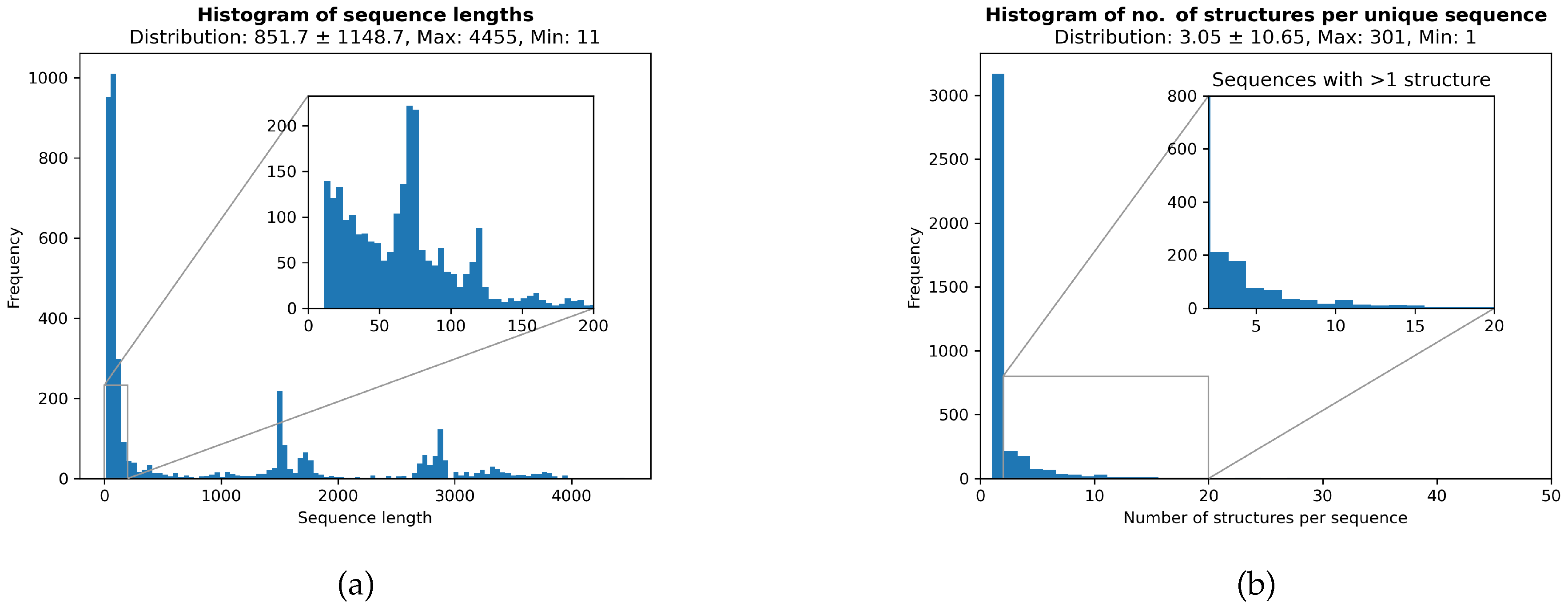

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Splits

2.3. Metrics

2.4. Graph Construction of RNA Structures

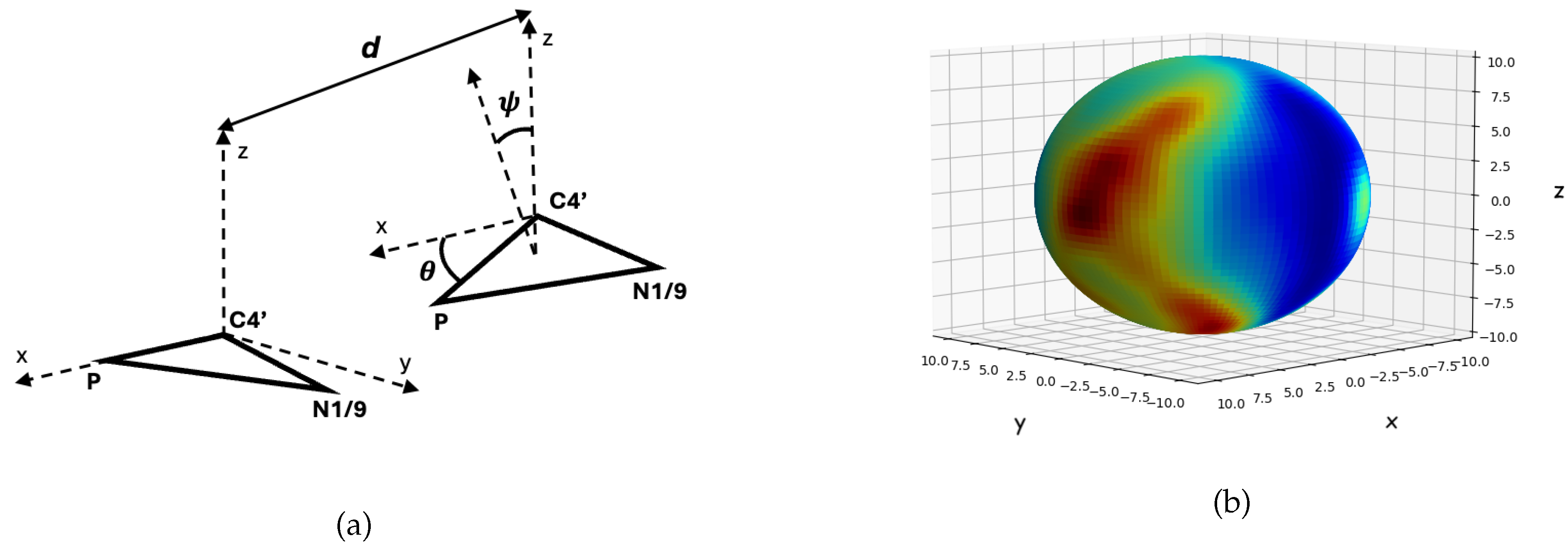

Nodes

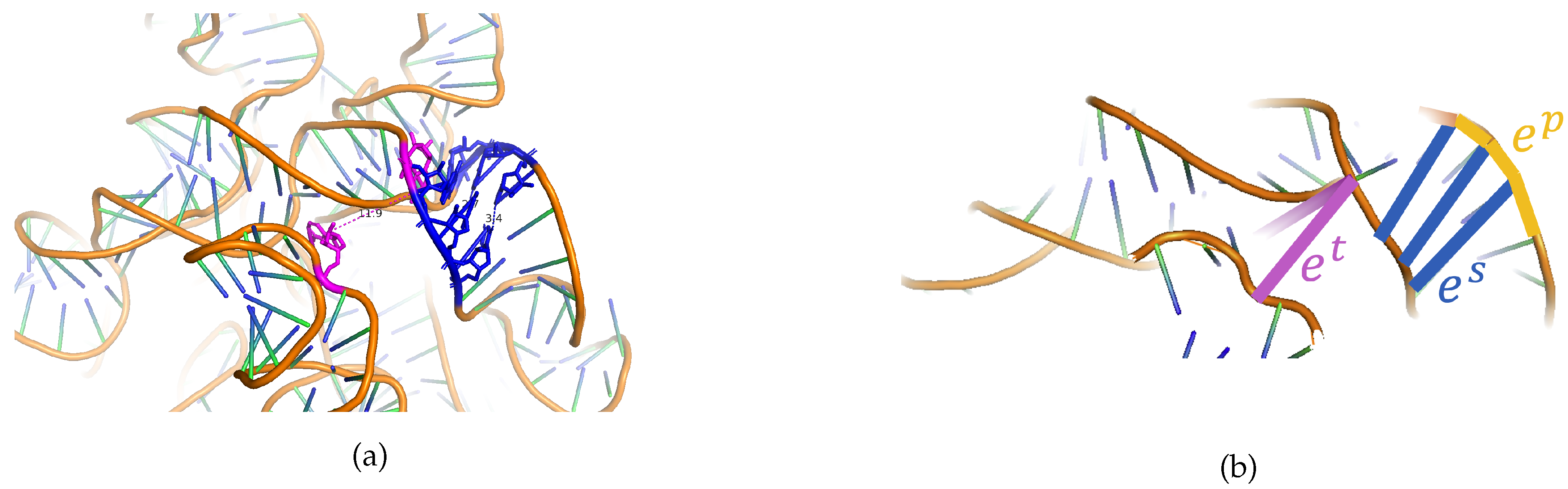

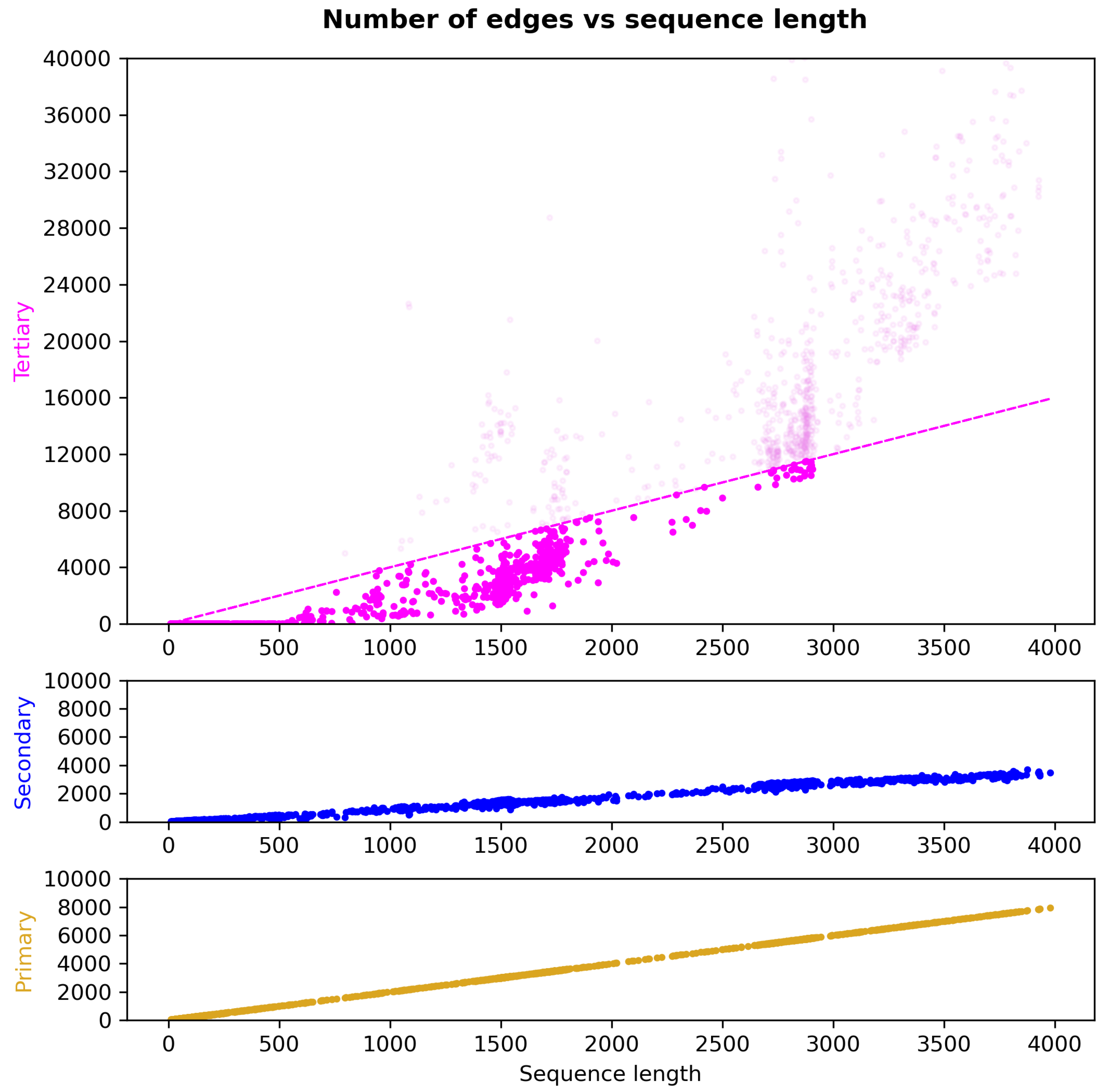

Primary-Structure Edge Types

Secondary-Structure Edge Types

Tertiary-Structure Edge Types

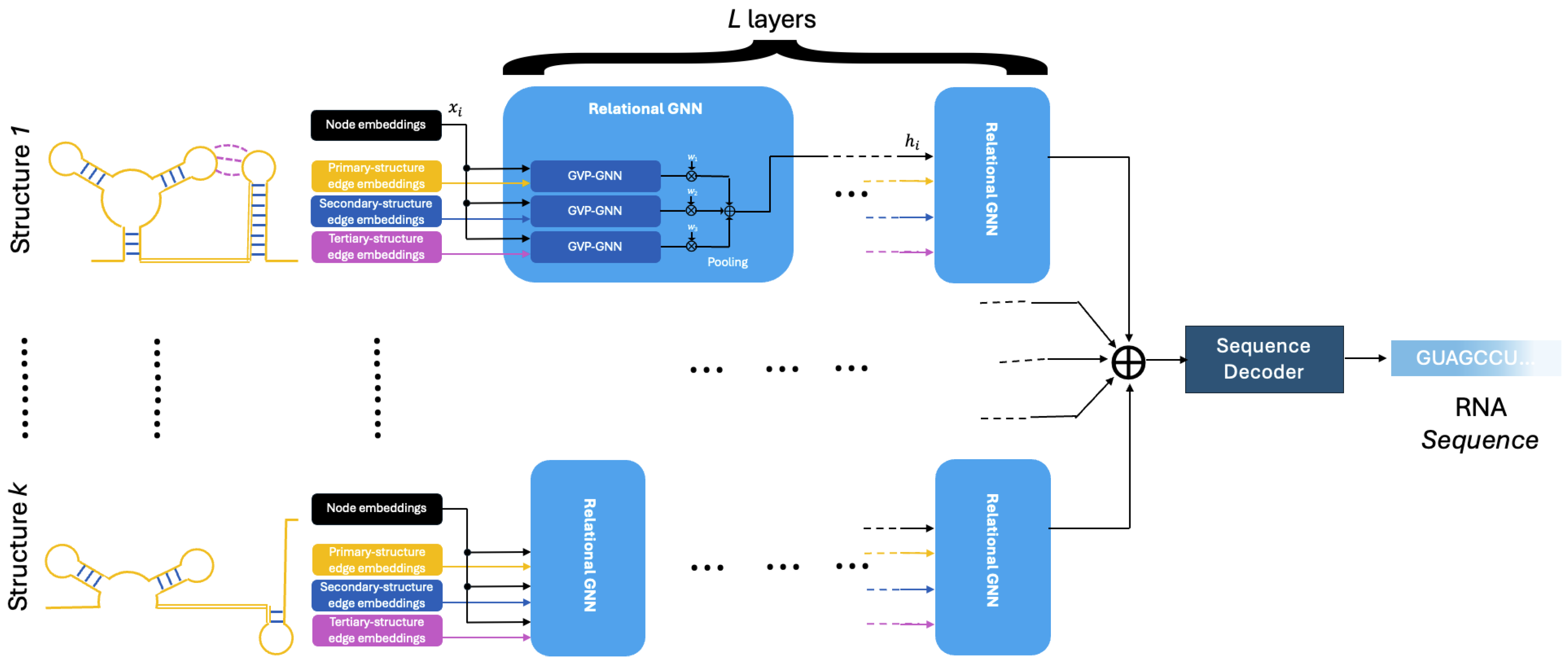

2.5. Relational Graph Neural Network

Input Embedding

Model Encoder

Model Decoder

3. Results

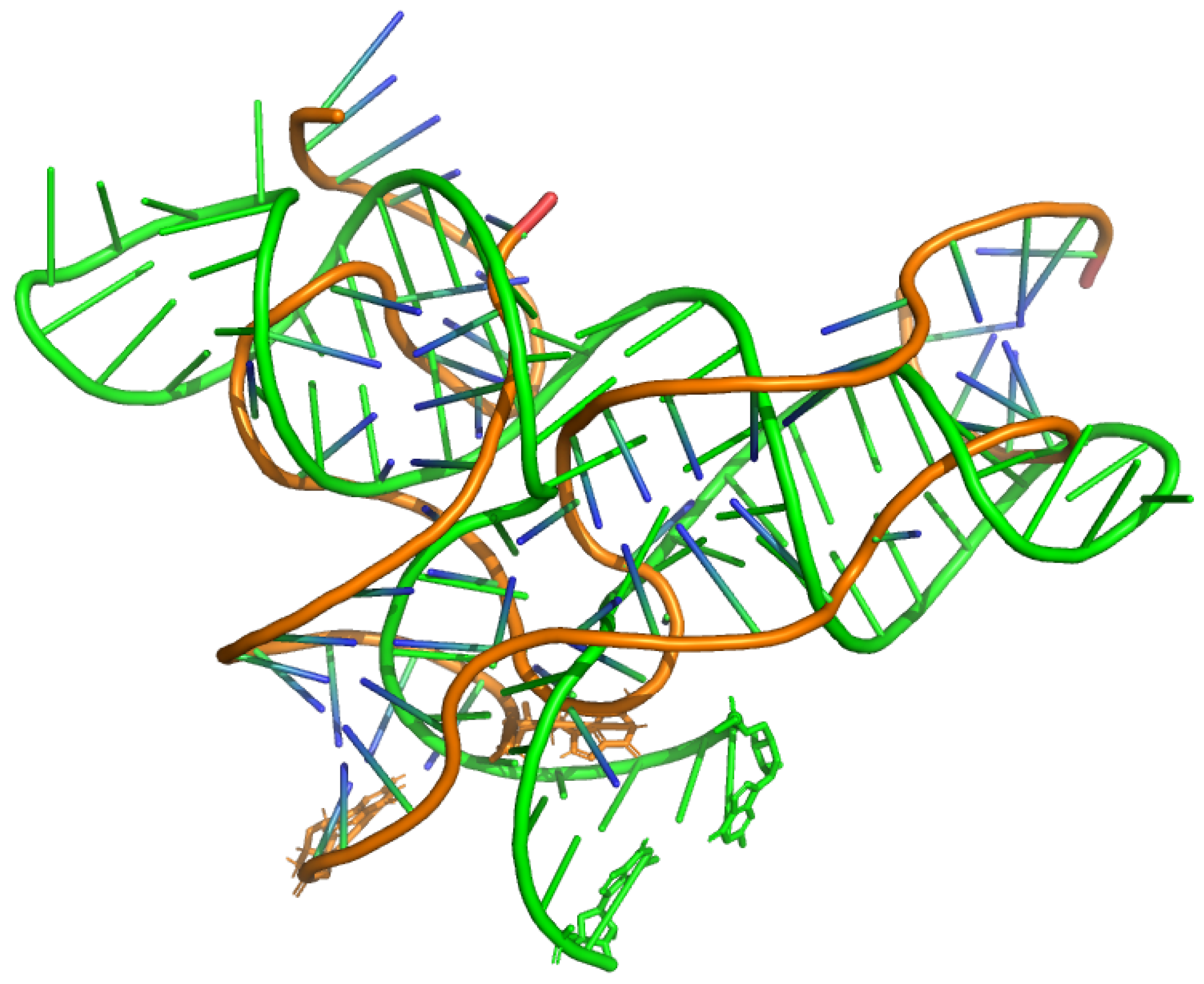

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Future Work

Author Contributions

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GVP-GNN | Geometric Vector Perceptron Graph Neural Network |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| gRNAde | Geometric Deep Learning for 3D RNA inverse design |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| Å | Ångström (unit of length) |

| O(3)-equivariant | Equivariance under the orthogonal group in 3 dimensions |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization system |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library for graph neural networks |

| libLEARNA | Library for solving the partial RNA design problem |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| DBSCAN | Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| CD-HIT | Cluster Database at High Identity with Tolerance |

| qTMclust | Structure Clustering by Sequence-Independent Structure Alignment |

| X3dna-dssr | An integrated software tool for Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA |

| Eternafold | RNA Secondary Structure Prediction Software |

| sc score | Secondary-Structure Self-Consistency Score |

| NAR | Non-Autoregressive |

| AR | Autoregressive |

| BP | Base Pairing |

| nt | Nucleotide |

| TPP | Thiamine Pyrophosphate |

| Ppl. | Perplexity |

| Acc. | Accuracy |

| Rec. | Recovery |

| SC | Secondary-structure Compatibility Score |

| DSSR | An integrated software tool for Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA |

| X3DNA | A software package for the Analysis and Visualization of 3D Nucleic Acid Structures |

| Fr3d | A software package for finding small RNA motifs in RNA 3D structures |

| AR-informed-2D | Autoregressive structure-informed model based on primary- and secondary-structure edge types |

| AR-informed-3D | Autoregressive structure-informed model based on primary-, secondary, and tertiary-structure edge types |

| seqid | Sequence-based data split |

| structsim | Structure-based data split |

| Pred | Prediction |

| AlphaFold | Algorithm for Protein and RNA 3D Structure Prediction |

| ProteinMPNN | Protein Message Passing Neural Network |

Appendix A. Supplementary Information

Appendix A.1. An Exploration into Tertiary-Structure Edge Type Characteristics

References

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; Weissman, D. MRNA Vaccines — a New Era in Vaccinology. Nature reviews. Drug discover/Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metkar, M.; Pepin, C.S.; Moore, M.J. Tailor made: the art of therapeutic mRNA design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, M.M.; Bruna, J.; Cohen, T.; Veličković, P. Geometric Deep Learning: Grids, Groups, Graphs, Geodesics, and Gauges, 2021, [arXiv:cs.LG/2104.13478].

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.M.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust deep learning-based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; Trippe, B.L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H.E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A.J.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, A.; Mathis, S.V.; Joshi, C.K.; Schmidt, V.; Miret, S.; Malliaros, F.D.; Cohen, T.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y.; Bronstein, M. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to Geometric GNNs for 3D Atomic Systems, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2312.07511].

- Mandal, M.; Breaker, R.R. Gene regulation by riboswitches. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppek, K.; Das, R.; Barna, M. Functional 5’ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.B.I. Coenzymes as fossils of an earlier metabolic state. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1976, 7, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, S.A.; Ellington, A.D.; Tauer, A. Modern metabolism as a palimpsest of the RNA world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1989, 86, 7054–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahvi, A.; Sudarsan, N.; Ebert, M.S.; Zou, X.; Brown, K.L.; Breaker, R.R. Genetic control by a metabolite binding mRNA. Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitreschak, A.G.; Rodionov, D.A.; Mironov, A.A.; Gelfand, M.S. Riboswitches: the oldest mechanism for the regulation of gene expression? Trends Genet. 2004, 20, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breaker, R.R. Riboswitches: from ancient gene-control systems to modern drug targets. Future Microbiol. 2009, 4, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaker, R.R. Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a003566–a003566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, A.V.; Henkin, T.M. Riboswitch-mediated gene regulation: Novel RNA architectures dictate gene expression responses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 70, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCown, P.J.; Corbino, K.A.; Stav, S.; Sherlock, M.E.; Breaker, R.R. Riboswitch diversity and distribution. RNA 2017, 23, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaker, R.R. Riboswitches and translation control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10, a032797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Breaker, R.R. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 305–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serganov, A.; Nudler, E. A Decade of Riboswitches. Cell 2013, 152, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peselis, A.; Serganov, A. Themes and variations in riboswitch structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1839, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaker, R.R. The biochemical landscape of riboswitch ligands. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blount, K.F.; Breaker, R.R. Riboswitches as antibacterial drug targets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deigan, K.E.; Ferré-D’Amaré, A.R. Riboswitches: discovery of drugs that target bacterial gene-regulatory RNAs. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh Aghdam, E.; Hejazi, M.S.; Barzegar, A. Riboswitches: From living biosensors to novel targets of antibiotics. Gene 2016, 592, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, V.; Brenk, R. Riboswitches as drug targets for antibiotics. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suess, B.; Weigand, J.E. Engineered riboswitches: overview, problems and trends. RNA Biol. 2008, 5, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, K.H.; Breaker, R.R. Engineering ligand-responsive gene-control elements: lessons learned from natural riboswitches. Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 1189–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C.M.; Smolke, C.D. RNA switches for synthetic biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickiser, J.K.; Winkler, W.C.; Breaker, R.R.; Crothers, D.M. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza-Mateos, A.; Nuthanakanti, A.; Serganov, A. Riboswitch mechanisms: New tricks for an old dog. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2021, 86, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavita, K.; Breaker, R.R. Discovering riboswitches: the past and the future. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkin, A.; Retwitzer, M.D.; Reinharz, V.; Ponty, Y.; Waldispühl, J.; Barash, D. Design of RNAs: comparing programs for inverse RNA folding. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, F.; Franke, J.; Fertmann, D.; Backofen, R.; Hutter, F. Partial RNA design. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, i437–i445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Höner zu Siederdissen, C.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms for Molecular Biology 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, J.K.; Weitzner, B.D.; Lewis, S.M.; Adolf-Bryfogle, J.; Alam, N.; Alford, R.F.; Aprahamian, M.; Baker, D.; Barlow, K.A.; Barth, P.; et al. Macromolecular modeling and design in Rosetta: recent methods and frameworks. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Hu, B.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.Z. RDesign: Hierarchical Data-efficient Representation Learning for Tertiary Structure-based RNA Design. In Proceedings of the The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lin, Z.; He, D.; Hong, L.; Li, Y. RiboDiffusion: tertiary structure-based RNA inverse folding with generative diffusion models. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, i347–i356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, C.K.; Jamasb, A.R.; Viñas, R.; Harris, C.; Mathis, S.; Liò, P. Multi-State RNA Design with Geometric Multi-Graph Neural Networks. arXiv preprint 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, B.; Eismann, S.; Suriana, P.; Townshend, R.J.L.; Dror, R.O. Learning from Protein Structure with Geometric Vector Perceptrons. ArXiv 2020, abs/2009.01411.

- Das, R.; Karanicolas, J.; Baker, D. Atomic accuracy in predicting and designing noncanonical RNA structure. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- oshi, C.K.; Jamasb, A.R.; Viñas, R.; Harris, C.; Mathis, S.V.; Morehead, A.; Anand, R.; Liò, P. gRNAde: Geometric Deep Learning for 3D RNA inverse design. bioRxiv 2024, [https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2024/05/25/2024.03.31.587283.full.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Olson, W.K. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three‚Äêdimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 5108–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.J.; Bussemaker, H.J.; Olson, W.K. DSSR: an integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, e142–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fey, M.; Lenssen, J.E. Fast graph representation learning with PyTorch Geometric 2019.

- Schrödinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8, 2015.

- Adamczyk, B.; Antczak, M.; Szachniuk, M. RNAsolo: a repository of cleaned PDB-derived RNA 3D structures. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 3668–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Niu, B.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, S.; Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3150–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Shine, M.; Pyle, A.M.; Zhang, Y. US-align: universal structure alignments of proteins, nucleic acids, and macromolecular complexes. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wayment-Steele, H.K.; Kladwang, W.; Strom, A.I.; Lee, J.; Treuille, A.; Becka, A.; Eterna Participants. ; Das, R. RNA secondary structure packages evaluated and improved by high-throughput experiments. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, W.K.; Maciejczyk, M.; Jankowska, E.J.; Bujnicki, J.M. Coarse-grained modeling of RNA 3D structure. Methods 2016, 103, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontis, N.B.; Westhof, E. Geometric nomenclature and classification of RNA base pairs. RNA 2001, 7, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingraham, J.; Garg, V.; Barzilay, R.; Jaakkola, T. Generative Models for Graph-Based Protein Design. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Wallach, H.; Larochelle, H.; Beygelzimer, A.; d’Alché-Buc, F.; Fox, E.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., Vol. 32. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.J.; Zipser, D. A Learning Algorithm for Continually Running Fully Recurrent Neural Networks. Neural Computation 1989, 1, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarver, M.; Zirbel, C.L.; Stombaugh, J.; Mokdad, A.; Leontis, N.B. FR3D: finding local and composite recurrent structural motifs in RNA 3D structures. J. Math. Biol. 2008, 56, 215–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.K.; Lee, Y.T.; Fan, L.; Wilt, H.M.; Conrad, C.E.; Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; Shi, G.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y.X.; et al. Crystal structure of <em>Escherichia coli</em> thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitch in the apo state. Structure 2023, 31, 848–859.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.; Mallet, V.; Waldisp√ºhl, J. , A.; Barash, D., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, 2025; pp. 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-4079-1_10.rnaglib. In RNA Design: Methods and Protocols; Churkin, A., Barash, D., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, 2025; Springer US: New York, NY, 2025; pp. 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fatlawi, A.; Hossen, M.B.; El-Hendi, F.; Schroeder, M. Protein secondary structure and remote homology detection. bioRxiv 2024, [https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2024/09/06/2024.09.03.611022.full.pdf]. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Lower perplexity does not always reflect a more superior model. It may be possible to have slightly high perplexity/entropy for individual nucleotide probabilities but a low perplexity/entropy on their joint distributions. |

| model | split | layers | Ppl. (↓) | Acc. (↑) | Rec. (↑) | SC (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR-original | seqid | 4 | 1.2501 | 66.08 | 50.84 | 63.18 |

| AR-informed-2D | seqid | 2 | 1.4875 | 71.12 | 54.51 | 53.00 |

| AR-informed-3D | seqid | 2 | 1.4136 | 71.84 | 54.10 | 52.32 |

| AR-informed-3D | seqid | 4 | 1.3526 | 72.24 | 58.37 | 52.92 |

| AR-original | structsim | 4 | 1.4843 | 62.72 | 44.85 | 55.41 |

| AR-informed-2D | structsim | 2 | 1.3422 | 68.61 | 50.31 | 51.06 |

| AR-informed-3D | structsim | 2 | 1.3471 | 68.66 | 49.40 | 51.59 |

| AR-informed-3D | structsim | 4 | 1.2984 | 69.02 | 50.23 | 54.57 |

| NAR-original | seqid | 4 | 1.5790 | 53.95 | 53.62 | 38.68 |

| NAR-informed-2D | seqid | 2 | 1.6062 | 59.87 | 61.06 | 42.44 |

| NAR-informed-3D | seqid | 2 | 1.4562 | 60.17 | 61.92 | 30.66 |

| NAR-informed-3D | seqid | 4 | 1.5483 | 61.02 | 61.39 | 0.4840 |

| NAR-original | structsim | 4 | 1.9695 | 47.18 | 43.51 | 39.36 |

| NAR-informed-2D | structsim | 2 | 1.4444 | 56.25 | 55.07 | 25.22 |

| NAR-informed-3D | structsim | 2 | 1.4398 | 54.97 | 51.44 | 26.37 |

| NAR-informed-3D | structsim | 4 | 1.3413 | 56.59 | 53.00 | 40.83 |

| PDB | Desc. | VRNA | RDes. | Ros. | gRNAde | AR-3D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1CSL | RRE high affinity site | 0.25 | 0.4455 | 0.44 | 0.5719 | 0.4263 |

| 1ET4 | RNA aptamer | 0.25 | 0.3929 | 0.44 | 0.6250 | 0.4379 |

| 1F27 | RNA pseudoknot | 0.30 | 0.3013 | 0.37 | 0.3437 | 0.3750 |

| 1L2X | RNA pseudoknot | 0.24 | 0.3727 | 0.48 | 0.4721 | 0.5765 |

| 1LNT | internal loop of SRP | 0.33 | 0.5556 | 0.53 | 0.5843 | 0.7131 |

| 1Q9A | Sarcin/ricin dom. | 0.27 | 0.4417 | 0.41 | 0.5044 | 0.8079 |

| 4FE5 | Guanine riboswitch | 0.29 | 0.4112 | 0.36 | 0.5300 | 0.7687 |

| 1X9C | All-RNA hairpin ribozyme | 0.26 | 0.3967 | 0.50 | 0.5000 | 0.3927 |

| 1XPE | HIV-1 B RNA | 0.27 | 0.3834 | 0.40 | 0.7037 | 0.4266 |

| 2GCS | glmS ribozyme | 0.25 | 0.4518 | 0.44 | 0.5078 | 0.6659 |

| 2GDI | TPP riboswitch | 0.25 | 0.3523 | 0.48 | 0.6500 | 0.7680 |

| 2OEU | Junctionless hairpin riboz. | 0.23 | 0.5000 | 0.37 | 0.9519 | 0.7680 |

| 2R8S | Tetrahymena ribozyme | 0.27 | 0.5641 | 0.53 | 0.5689 | 0.6985 |

| 354D | Loop E | 0.28 | 0.4458 | 0.55 | 0.4410 | 0.8210 |

| Overall recovery: | 0.27 | 0.4296 | 0.45 | 0.5682 | 0.6044 |

| name | sequence |

|---|---|

| 8F4O_1_B | GCGACUCGGGGUGAAGGCUGAGAAAUACCCGUAUCACCUGAUCUGGAGCCAGCGUAGGGAAGUCG |

| Pred_1 | GCGCCUCGGGGUGAAAGCUGAGAAAUACCGGUAGCACUUCUUUUCGUUCGAACGUAAGGAAGGCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).