1. Introduction

The likelihood of falling increases significantly with age, particularly among those residing in long-term care (LTC) facilities, where the risk is even higher. This elevated risk persists despite some evidence suggesting improvements in the overall health of older adults [

1].

Globally, the population aged 65 years and older was approximately 703 million in 2019, with this number projected to double by 2050 [

2]. In South Africa, the elderly population is also growing rapidly, particularly in provinces like the Western Cape, where the percentage of older adults increased from 8.9% in 2011 to 10.7% in 2022 [

3]. This demographic shift is particularly pronounced in developing countries, where aging is occurring at an accelerated rate, compounded by socioeconomic challenges such as poverty, and exacerbated by the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics [

2,

4,

5].

In sub-Saharan Africa, and especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the older population is expanding at a faster pace than in developed nations, often without the necessary infrastructure and resources to provide adequate care [

6]. This is concerning, as the highest proportions of older adults in South Africa are concentrated in regions like the Eastern Cape (11.5%), Western Cape (10.7%), and Northern Cape (10.1%) [

3]. Given these trends, understanding and mitigating the risk factors for falls in this vulnerable population is crucial.

Falls among older adults are typically not caused by a single factor but rather by a combination of intrinsic (e.g., visual problems, osteoporosis, balance difficulties), extrinsic (e.g., environmental hazards), and behavioural factors [

7]. These multiple risk factors collectively increase the likelihood of falling, particularly in LTC facilities where older adults often experience reduced mobility and frailty. Addressing these risk factors is essential for fall prevention and improving the quality of life for older adults [

8,

9].

The consequences of falls extend beyond physical injuries; they also include significant psychological impacts such as loss of confidence, fear of falling, and limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs). These consequences can lead to a decline in functional capacity and overall quality of life [

10]. Given the severity of these outcomes, it is imperative to develop targeted interventions to reduce fall risks in LTC facilities.

Despite the growing elderly population and the associated risks, there has been a lack of research specifically investigating the prevalence of falls among older adults in LTC facilities in the City of Cape Town. This gap in the literature underscores the need for studies that can inform local healthcare practices and policies. Therefore, this study aims to determine the prevalence of falls among older adults living in various LTC facilities in the City of Cape Town, providing valuable insights for future fall prevention strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design where 258 male and female older adults were conveniently recruited to participate in the study. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, limitations on sample size were imposed by care facilities. Potential participants were identified by the nursing managers and, thereafter, an information session about the research was held with the potential participants. The fifteen facilities that consented to participate in the study were regions in the Atlantic Seaboard, Southern Suburbs, and the Northern Suburbs of Cape Town. Data collection was conducted on a once-off basis from September 2021 to January 2022. Males and females, aged 60 years and older living in LTC facilities in the CoCT for a minimum of one year, who were independently ambulatory, without the support of a walking aid, were included. Older adults who were not living in LTC facilities, with physical disabilities who were dependent on a walking aid for ambulation, were frail, wheelchair-bound, or bed-ridden, were excluded. Ethical clearance to conduct the study was provided by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape (Ethics number: BM21/6/18).

2.1. Fall Risk Assessment Tool

The Fall Risk Assessment Tool FRAT is a previously validated 4-item fall risk assessment tool used in residential care settings and is composed of two sections, i.e., part one was a screening tool used to obtain a risk score [

11]. Questions were asked regarding recent falls, medications used, and the participant’s psychological and cognitive status. The total score for the fall-risk status indicated a low (5 – 11), moderate (12 – 15) or high fall-risk (16 - 20) for the participants. The second part of the FRAT is a risk factor checklist to identify possible risk factors that contributed to falling. These were identified as major risk factors for falls in hospitals and residential care facilities, which included poor vision, concerning behaviours (e.g., agitation, confusion, disorientation, and difficulty following instructions/non-compliant), unstable mobility, unsafe transfers, incontinence, unsafe footwear, challenging environment, poor nutrition, impaired ADL’s and other (which refers to other risk factors not listed in the study).

2.2. Data Analysis

Data was analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 28). The data was checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilks test. Descriptive statistical analysis (means, standard deviations, and frequencies) was used to describe the variables, such as age, and BMI. Spearman’s correlation was used to determine the associations between falls and fall risk factors. The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to determine the associations between categorical variables (facility type, gender, age-group, marital status and education level).

3. Results

A total of 357 participants initially consented to participate in the study; however, due to constraints imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, only 258 participants were recruited, resulting in a response rate of 72.3%. Of these participants, 28.7% (n = 74) were male, and the majority, 71.3% (n = 184), were female. The mean (X̅± SD) age of the participants was 78.2 ± 7.4 years. The age distribution showed that 13.2% (n = 34) of participants were in the 60–69 years age group, 39.9% (n = 103) were in the 70–79 years age group, 43.0% (n = 111) were in the 80–89 years age group, and 3.9% (n = 10) were aged 90 years or older.

The results indicated that most participants (52.3%; n = 135) were either overweight or obese. In terms of education, 50.4% of participants had completed matric (grade 12), with 30.6% (n = 79) from mainstream schools and 19.8% (n = 51) from technical schools. Additionally, 20.5% of participants held a graduate qualification from a tertiary institution. Almost half of the participants (43.4%; n = 112) were widowed.

The study found that 32.6% of participants had experienced a fall in the past three months, while 67.4% (n = 174) had not sustained a fall during this period. The primary mechanisms of falls were slipping/tripping (15.5%; n = 40), followed by loss of balance (10.5%; n = 27) and dizziness (5.0%; n = 13).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

| Category |

n (%) |

| Gender |

| Male |

74 (28.7) |

| Female |

184 (71.3) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

| Age (years) |

| 60 – 69 |

34 (13.2) |

| 70 – 79 |

103 (39.9) |

| 80 – 89 |

111 (43.0) |

| ≥90 |

10 (3.9) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

| Obesity (kg/m2) |

|

| Underweight |

10 (3.9) |

| Normal |

113 (43.8) |

| Overweight |

87 (33.7) |

| Obese |

48 (18.6) |

| Educational level |

| Grade 7 or lower |

32 (12.4) |

| Grades 8 - 11 |

43 (16.7) |

| Matriculated from mainstream school |

79 (30.6) |

| Matriculated from technical school |

51 (19.8) |

| Graduated with a bachelors’ degree |

42 (16.3) |

| Graduated with a masters’ degree |

6 (2.3) |

| Graduated with a doctoral degree |

5 (1.9) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

| Marital Status |

| Married |

63 (24.4) |

| Single |

44 (17.1) |

| Divorced |

39 (15.1) |

| Widowed |

112 (43.4) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

| Fall History |

| No |

67.4 (174) |

| Yes |

32.6 (84) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

| Fall Mechanisms |

| Slipping/Tripping |

40 (15.5) |

| Loss of balance |

27 (10.5) |

| Collapse |

9 (3.5) |

| Legs give way |

2 (0.8) |

| Dizziness |

13 (5.0) |

| Total |

258 (100) |

In examining the three-month fall prevalence, it was found that females had a higher prevalence of falls (77.5%; n = 31) compared to males (22.5%; n = 9), with slipping/tripping being the most common cause. Conversely, dizziness was more prevalent among males (53.8%; n = 8). Loss of balance showed a similar prevalence among males (10.8%; n = 8) and females (10.3%; n = 19). Of the 40 participants who experienced slipping/tripping, 30.0% (n = 12) were in the 70–79 years age group and 45.0% (n = 18) were in the 80–89 years age group. Similarly, of the 27 participants who experienced loss of balance, 40.7% (n = 11) were in the 70–79 years age group and 48.1% (n = 13) were in the 80–89 years age group.

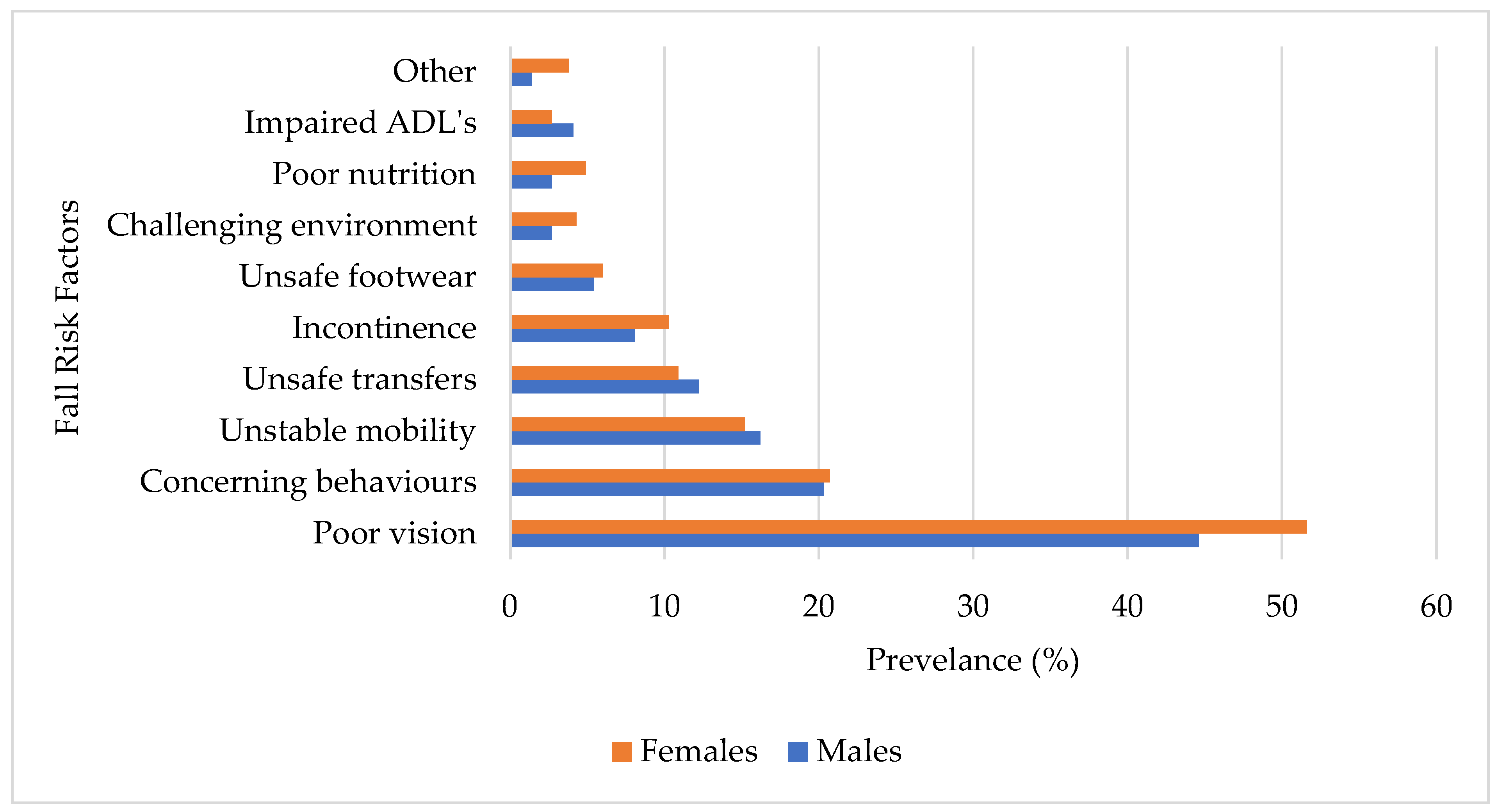

The prevalence of fall risk factors among older adults showed that poor vision was the most common (49.6%; n = 128). Other notable risk factors included concerning behaviours (20.5%; n = 53), poor mobility (15.5%; n = 40), unstable transfers (11.2%; n = 28), incontinence (9.7%; n = 24), and various unspecified factors (2.7%; n = 7).

The fall risk factors by gender (

Figure 1) revealed that poor vision was the most prevalent among both males (44.6%; n = 33) and females (51.6%; n = 95). Concerning behaviours were reported similarly by males (20.3%; n = 15) and females (20.7%; n = 38). The prevalence of unstable mobility was comparable between males (15.2%; n = 12) and females (16.2%; n = 28). Unsafe transfers were slightly more common in males (12.2%; n = 8) compared to females (10.9%; n = 20). Incontinence as a risk factor was slightly higher in females (10.3%; n = 19) than in males (8.1%; n = 5). Unsafe footwear presented with a similar prevalence in males (5.4%; n = 4) and females (6.0%; n = 11). Environmental challenges were reported by 2.7% (n = 2) of males compared to 4.3% (n = 8) of females. Poor nutrition was more prevalent in females (4.89%; n = 9) than in males (2.70%; n = 1). Impaired ADLs were slightly more common in males (4.1%; n = 2) than in females (2.71%; n = 5).

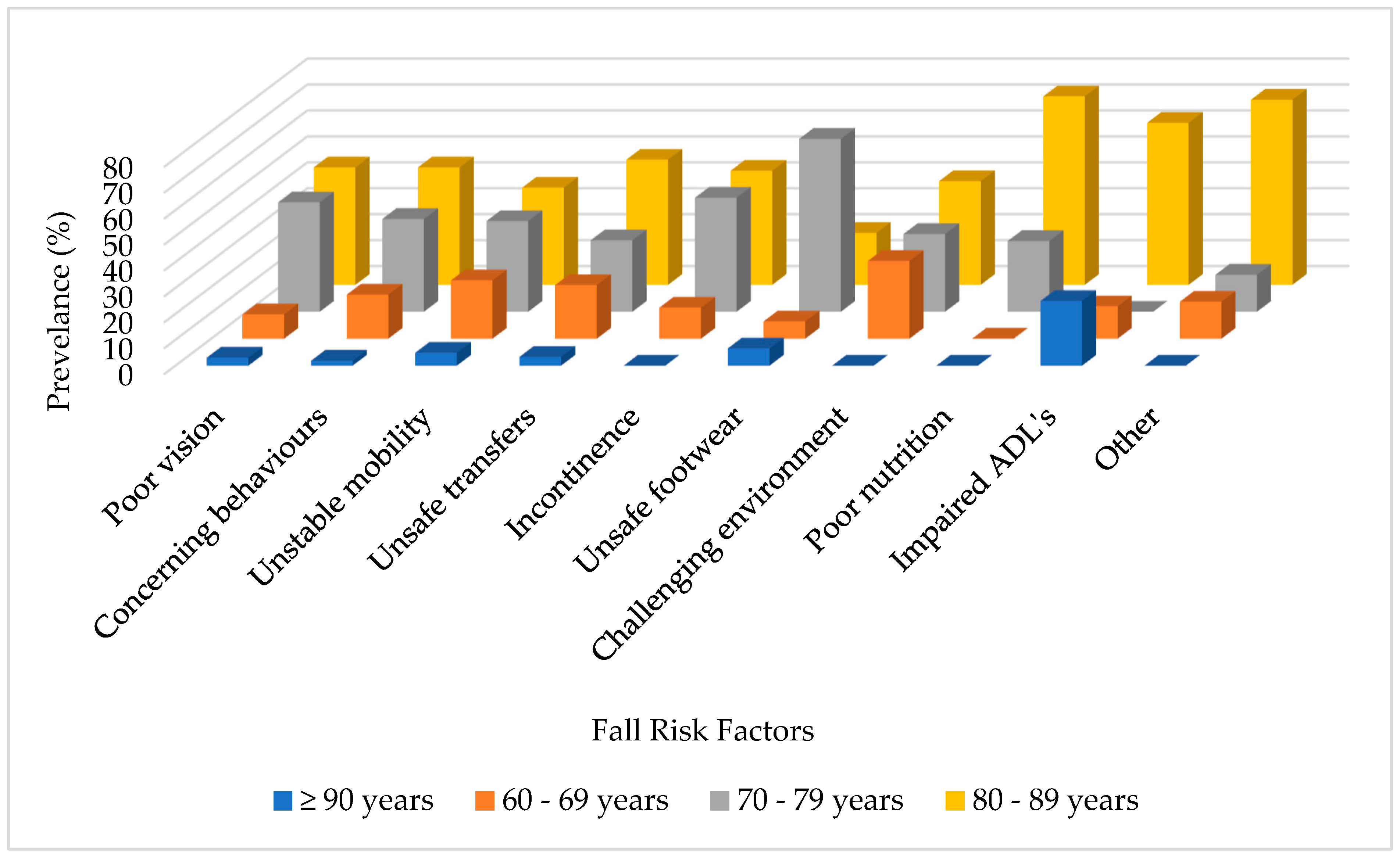

Regarding age groups (

Figure 2), participants aged 60–69 years had a high prevalence of risks related to challenging environments (30.0%; n = 3), poor mobility (22.5%; n = 9), and unsafe transfers (20.7%; n = 6). In the 70–79 years age group, unsafe footwear (66.7%; n = 1), incontinence (44.0%; n = 11), and poor vision (42.2%; n = 54) were the most common risk factors. The 80–89 years age group showed a high prevalence of poor nutrition (72.7%; n = 7), unspecified risk factors (71.4%; n = 4), and impaired ADLs (62.5%; n = 4). Among those aged 90 years and older, impaired ADLs (25.0%; n = 2), unsafe footwear (6.7%; n = 1), and unstable mobility (5.0%; n = 2) were the most prevalent.

The relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants and the occurrence of falls (

Table 3) revealed that facility type (X² = 7.403; p = 0.007), level of education (X² = 14.05; p = 0.029), and marital status (X² = 16.49; p = 0.001) were significantly associated with falls. The analysis also indicated a significant association between falls and certain observed behaviours, such as concerning behaviours (X² = 6.486; p = 0.011) and other issues (X² = 4.951; p = 0.026).

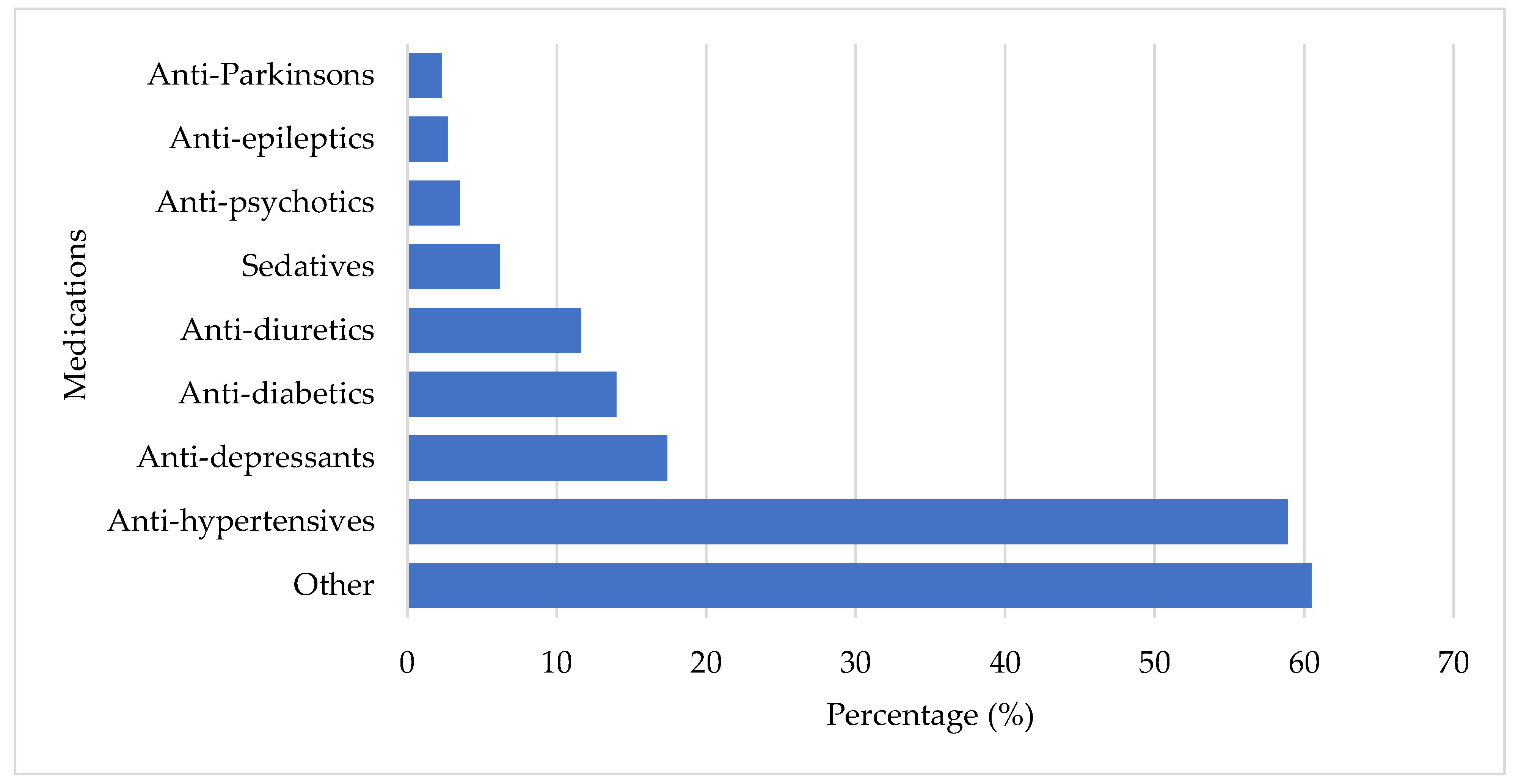

Regarding the number of medications used, 62.0% of participants were taking more than two medications, with the majority being female (71.3%). The highest medication usage was observed in the 70–79 years (42.5%) and 80–89 years (39.4%) age groups. A total of 461 medications (

Figure 3) were used by the participants. The smallest percentages of medications used were anti-Parkinson’s (2.3%; n = 6), anti-epileptics (2.7%; n = 7), and anti-psychotics (3.5%; n = 9). Sedatives (6.2%; n = 16), anti-diuretics (11.6%; n = 30), anti-diabetics (14.0%; n = 36), and anti-depressants (17.4%; n = 45) were more commonly used. The majority of participants were medicated with anti-hypertensives (58.9%; n = 152) and other (60.5%; n = 156) medications. Participants who used anti-depressants [X² (1) = 4.941; p = 0.026, OR = 2.083 (95% CI: 0.611, 1.763)] and anti-diabetics [X² (1) = 4.097; p = 0.043, OR = 2.070 (95% CI: 1.013, 4.228)] were approximately four times more likely to experience a fall.

4. Discussion

The study aimed to determine the prevalence of falls among older adults living in LTC facilities in the City of Cape Town. The findings revealed a fall prevalence of 32.6% among participants, aligning with similar studies in Saudi Arabia (34%), China (31.7%), Brazil (38.9%), and Malaysia (32.8%) [

10,

12,

13,

14]. However, these results differ from studies conducted in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Egypt, which reported higher prevalence rates of 50.8% and 60.3%, respectively [

9,

15]. Another study indicated that fall prevalence was higher among women than men, which is consistent with this study’s findings [

16]. On the other hand, a systematic review showed a lower global prevalence of falls (26.5%) [

17]. These variations in fall prevalence could be influenced by several factors, including differences in study designs, cultural norms, and healthcare conditions across countries.

Falls related to slipping/tripping showed a much higher prevalence of 68.5% [

18]. Factors such as poor mobility, incorrect footwear, decreased strength, and balance issues may explain the high incidence of falls due to slipping/tripping [

19,

20]. The majority of falls occurred among participants aged 70-79 years (39.9%) and 80-89 years (43.0%), consistent with other studies where the highest fall rates were also observed in the 80-89 age group, particularly in LTC facilities [

20,

21]. The lower fall rates among participants aged 60-69 years may be attributed to their relatively better physical strength [

21]. Participants aged 90 years and older often experienced lower fall rates, possibly due to being bedridden or less mobile, which reduced their fall risk [

20]. This contrasts with findings from other studies, which suggest that age is not always a significant determinant of falls [

21,

23].

A significant association was found between concerning behaviours and falls in this study. Nearly half (47.2%) of the participants exhibited problem behaviours, which significantly increase fall risk. These behaviours may be influenced by the participants’ perceptions of independence, their fall history, their understanding of fall risks, and their willingness to accept support from staff and healthcare professionals [

20]. In LTC facilities, safety regulations are often enforced by staff, which can lead to risk-taking behaviours among residents as they adapt to institutional rules, ultimately increasing fall risk [

24,

25,

26]. The study also found that other risk factors not listed as major factors, were significantly associated with falls. Multiple studies have identified over 400 risk factors for falls, with no universally accepted classification system to simplify their understanding [

27,

28,

29]. According to Williams et al. (2015), various factors, including older age, female gender, physical frailty, muscle weakness, poor gait and balance, impaired cognition, and depressive symptoms, contribute to an increased risk of falls. This risk further escalates with comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and diabetes [

30]. The study revealed that participants from NPO LTC facilities were more likely to experience falls than those from private facilities. This may be due to understaffing, limited safety resources, cost-cutting measures, and inadequate infrastructure in NPO facilities [

31,

32,

33]. In contrast, private LTC facilities often employ multidisciplinary teams, including occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and biokineticists, who specialize in working with older adults and implementing fall prevention procedures. These professionals also provide individualized care and continuously educate staff on safety measures [

34,

35]. Unfortunately, public healthcare facilities for older adults are often underfunded and must contend with a high burden of disease, limited support staff, and overcrowding compared to private facilities [

35].

Education level was also significantly associated with fall risk in this study. Participants with lower education levels were more likely to experience falls, consistent with other research showing that individuals with lower education, particularly women, have higher fall rates [

36]. It is suggested that lower education levels may lead to difficulties in understanding fall prevention information, indicating the need for targeted fall prevention programs among this population [

37]. Additionally, lower education levels may affect cognitive abilities, making tasks like visual search more challenging and increasing fall risk [

38].

Regarding marital status, the study found that married participants had a lower risk of falling compared to their single or unmarried counterparts. Being widowed was associated with an increased fall risk, highlighting the protective role of having a partner who provides social support [

39]. These findings are consistent with other studies, including the South African census, which reported health advantages associated with marriage [

40,

41,

42].

Medication use was significantly associated with falling. Similar to this study, previous research found that the use of anti-diabetic and anti-psychotic medications was associated with an increased fall risk [

43,

44]. Polypharmacy, or the use of multiple medications, was also identified as a significant risk factor for falls [

12,

21,

45]. A systematic review further supported the finding that the use of four or more medications significantly increases the likelihood of falls. Reducing the use of psychotropic medications has been shown to decrease fall rates, highlighting the importance of careful medication management in fall prevention [

46,

47].

5. Conclusion

This study revealed a high incidence falls among older adults, with one-third of participants experiencing such events. These findings align with previous research, highlight the urgent need for interventions to reduce injuries and enhance the well-being of older adults. As participants age, the occurrence of falls increases, particularly among those engaging in high-risk behaviours. Despite technological advancements, a thorough history taking process remains essential in assessing fall risk among older adults.

By identifying and understanding the factors that elevate the risk of falls, healthcare professionals can play a vital role in reducing the incidence of falls. This highlights the importance of examining the roles of long-term (LTC) staff to ensure that the appropriate healthcare professionals are designated to specific tasks, ensuring that older adults in these facilities receive the necessary care to address this global concern [49]. Future research should focus on interventions aimed at promoting educational and behavioural changes among older adults to reduce the risk of falls and related injuries.

Author Contributions

Supervision, Lloyd Leach; Writing – original draft, Nabilah Ebrahim.

Funding

This research was funded by the Africa Wetu Foundation- NPC. NPC No.: 2020/622200/08, PBO No.: 90071454. www.africawetufoundation.org.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance to conduct the study was provided by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Western Cape (Ethics number: BM21/6/18).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LTC |

Long Term Care |

| FRAT |

Fall Risk Assessment Tool |

References

- Guoqing, S., Kun, D., Hao, C., & Jingwei, X. (2020). A Study of Fall Risk Assessment in the Elderly. 197(Icaset), 176–183.

- Kalula, S., Ferreira, M., Swingler, G. H., Badri, M., & Sayer, A. A. (2017). Methodological challenges in a study on falls in an older population of cape town, South Africa. African Health Sciences, 17(3), 912–922. [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa, 2022. (2022). Mid-year population estimates. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022022.pdf.

- Aboderin, I. (2011). Understanding and advancing the health of older populations in sub-Saharan Africa: Policy perspectives and evidence needs. In Public Health Reviews (Vol. 33, Issue 2, pp. 357–376).

- Kelly, G., Mrengqwa, L., & Geffen, L. (2019). “they don’t care about us”: Older people’s experiences of primary healthcare in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Aboderin, I. A. G., & Beard, J. R. (2015). Older people’s health in sub-Saharan Africa. In The Lancet (Vol. 385, Issue 9968, pp. e9–e11). Lancet Publishing Group. [CrossRef]

- Fraix, M. (2012). Role of the musculoskeletal system and the prevention of falls. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 112(1), 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Iamtrakul, P., Chayphong, S., Jomnonkwao, S., & Ratanavaraha, V. (2021). The association of falls risk in older adults and their living environment: A case study of rural area, Thailand. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(24). [CrossRef]

- Sharif, R. S., & Al-daour, D. S. (2018). Falls in the elderly : assessment of prevalence and risk factors. Pharmacy Practice [revista en Internet] 2018 [acceso 4 de enero de 2020]; 16(3): 1-7. 16(3), 1–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6207352/pdf/pharmpract-16-1206.pdf.

- Kioh, S. H., & Rashid, A. (2018). The prevalence and the risk of falls among institutionalised elderly in penang, malaysia. Medical Journal of Malaysia, 73(4), 212–219.

- Department of Health Victoria. (2015). Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) Victoria. Https://Www.Health.Vic.Gov.Au/Publications/Falls-Risk-Assessment-Tool-Frat. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/falls-risk-assessment-tool-frat.

- Almegbel, F. Y., Alotaibi, I. M., Alhusain, F. A., Masuadi, E. M., Al Sulami, S. L., Aloushan, A. F., & Almuqbil, B. I. (2018). Period prevalence, risk factors and consequent injuries of falling among the Saudi elderly living in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Firpo, G., Duca, D., Ledur Antes, D., Curi, P., & Ii, H. (2013). Quedas e fraturas entre residentes de instituições de longa permanência para idosos Falls and fractures among older adults living in long-term care. In Rev Bras Epidemiol (Vol. 16, Issue 1).

- Zhang, L., Zeng, Y., Weng, C., Yan, J., & Fang, Y. (2019). Epidemiological characteristics and factors influencing falls among elderly adults in long-term care facilities in Xiamen, China. Medicine, 98(8), e14375. [CrossRef]

- Orces, C. H. (2013). Prevalence and determinants of falls among older adults in ecuador: An analysis of the SABE i survey. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Gale, C. R., Cooper, C., & Sayer, A. A. (2016). Prevalence and risk factors for falls in older men and women: The English longitudinal study of ageing. Age and Ageing, 45(6), 789–794. [CrossRef]

- Salari, N., Darvishi, N., Ahmadipanah, M., Shohaimi, S., & Mohammadi, M. (2022). Global prevalence of falls in the older adults: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 17(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Imaginário, C., Martins, T., Araújo, F., Rocha, M., & MacHado, P. P. (2021). Risk Factors Associated with Falls among Nursing Home Residents: A Case-Control Study. Portuguese Journal of Public Health, 39(3), 120–130. [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, J., Jernbro, C., & Nilson, F. (2018). There is more to life than risk avoidance–elderly people’s experiences of falls, fall-injuries and compliant flooring. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Xia, Q., Zhou, P., Jiang, S., Diwan, V. K., & Xu, B. (2020). Falls and Fall-Related Consequences among Older People Living in Long-Term Care Facilities in a Megacity of China. Gerontology, 66(6), 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Dhargave, P., & Sendhilkumar, R. (2016). Prevalence of risk factors for falls among elderly people living in long-term care homes. Journal of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics, 7(3), 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Ghazi, H. F., Elnajeh, M., Abdalqader, M. A., Baobaid, M. F., Rahimah Rosli, N. S., & Syahiman, N. (2017). The prevalence of falls and its associated factors among elderly living in old folks home in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health, 4(10), 3524. [CrossRef]

- Satariano, W. A. (2010). The Ecological Model in the Context of Aging Populations : A Portfolio of. Jasp, 1–20.

- Castaldo, A., Giordano, A., Antonelli Incalzi, R., & Lusignani, M. (2020). Risk factors associated with accidental falls among Italian nursing home residents: A longitudinal study (FRAILS). Geriatric Nursing, 41(2), 75–80. [CrossRef]

- Living, D., Scores, S.-, Cumming, R. G., Salkeld, G., Thomas, M., & Szonyi, G. (2000). Nursing Home Admission. 55(5), 299–305.

- Tolson, D., & Morley, J. E. (2011). Medical Care in the Nursing Home. Medical Clinics of North America, 95(3), 595–614. [CrossRef]

- Callis, N. (2016). Falls prevention: Identification of predictive fall risk factors. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 53–58. [CrossRef]

- Deandrea, S., Bravi, F., Turati, F., Lucenteforte, E., La Vecchia, C., & Negri, E. (2013). Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56(3), 407–415. [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, L. Z. (2006). Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age and Ageing, 35(SUPPL.2), 37–41. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. S., Kowal, P., Hestekin, H., Driscoll, T. O., Peltzer, K., & Yawson, A. (2015). Prevalence , risk factors and disability associated with fall-related injury in older adults in low- and middle-incomecountries : results from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health ( SAGE ). 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A. T., Abd Elltef, M. A. B., & Miky, S. F. (2020). Prevention Program Regarding Falls among Older Adults at Geriatrics Homes. Evidence-Based Nursing Research, 2(2), 11. [CrossRef]

- Rapp, K., Becker, C., Cameron, I. D., König, H.-H., & Büchele, G. (2012). Epidemiology of falls in residential aged care: analysis of more than 70,000 falls from residents of bavarian nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 13(2), 187.e1-6. [CrossRef]

- Shao, L., Shi, Y., Xie, X., Wang, Z., Wang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2023). Incidence and Risk Factors of Falls Among Older People in Nursing Homes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. [CrossRef]

- King, B., Pecanac, K., Krupp, A., Liebzeit, D., & Mahoney, J. (2018). Impact of Fall Prevention on Nurses and Care of Fall Risk Patients. Gerontologist, 58(2), 331–340.

- Rizka, A., Indrarespati, A., Dwimartutie, N., & Muhadi, M. (2021). Frailty among older adults living in nursing homes in indonesia: Prevalence and associated factors. Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research, 25(2), 93–97. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, R., Ashwell, A., Docrat, S., Schneider STRiDE South Africa, M., candidate, M., & Schneider, M. (2020). The Impact of Covid-19 on Long-term Care Facilities in South Africa with a specific focus on Dementia Care. https://stride-dementia.org/.

- Wen, Y., Liao, J., Yin, Y., Liu, C., Gong, R., & Wu, D. (2021). Risk of falls in 4 years of follow-up among Chinese adults with diabetes: Findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMJ Open, 11(6). [CrossRef]

- Abreu, H. C. de A., Reiners, A. A. O., Azevedo, R. C. de S., da Silva, A. M. C., Abreu, D. R. de O. M., & de Oliveira, A. D. (2015). Incidence and predicting factors of falls of older inpatients. Revista de Saude Publica, 49. [CrossRef]

- Bloch, F., Thibaud, M., Dugué, B., Brèque, C., Rigaud, A. S., & Kemoun, G. (2010). Episodes of falling among elderly people: A systematic review and meta-analysis of social and demographic pre-disposing characteristics. Clinics, 65(9), 895–903. [CrossRef]

- Carr, D., & Springer, K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 743–761. [CrossRef]

- Jennings, E. A., Chinogurei, C., & Adams, L. (2022). Marital experiences and depressive symptoms among older adults in rural South Africa. SSM - Mental Health, 2(March), 100083. [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. (2014). Census 2011: Profile of older persons in South Africa. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-01-60/Report-03-01-602011.pdf.

- Costa-Dias, M. J., Oliveira, A. S., Martins, T., Araújo, F., Santos, A. S., Moreira, C. N., & José, H. (2014). Medication fall risk in old hospitalized patients: a retrospective study. Nurse Education Today, 34(2), 171–176. [CrossRef]

- Obayashi, K., Araki, T., Nakamura, K., Kurabayashi, M., Nojima, Y., Hara, K., Nakamura, T., & Yamamoto, K. (2013). Risk of falling and hypnotic drugs: Retrospective study of inpatients. Drugs in R and D, 13(2), 159–164. [CrossRef]

- Kalula, S. Z., Ferreira, M., Swingler, G. H., & Badri, M. (2016). Risk factors for falls in older adults in a South African Urban Community. In BMC Geriatrics (Vol. 16, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Du, Y., Wolf, I. K., & Knopf, H. (2017). Association of psychotropic drug use with falls among older adults in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults 2008-2011 (DEGS1). PLoS ONE, 12(8), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Hill, K. D., & Wee, R. (2012). Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people: a review of interventions aimed at reducing the problem. Drugs & Aging, 29(1), 15–30. [CrossRef]

- Mapira, L., Kelly, G., & Geffen, L. N. (2019). A qualitative examination of policy and structural factors driving care workers’ adverse experiences in long-term residential care facilities for the older adults in Cape Town. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).