1. Introduction

There are many resources for creating digital text data, including social media posts, online news articles, customer reviews, and many other forms. This has caused the volume of digital text data to grow. At the same time, the development of machine learning methods allows this data to be processed for various tasks. Machine learning methods in this domain have applications for:

text classification is the categorization and dividing of a text into predefined classes, for example, identification of spam or labeling topics in news posts [

1,

2];

information search is extracting relevant information from large collections of text documents based on user queries to support efficient search functions [

3];

speech recognition is an automatic process to transform a speech signal into digital information that can be used in voice assistants and automated phone systems [

4];

machine translation is an automatic process of translating a text from one language to another based on the exploitation of machine learning or deep learning methods [

5,

6];

text summarization is the automatic process of constructing a new short text containing the main information from an initial text, which is useful for condensing news articles or product descriptions [

7];

sentiment analysis is analyzing the sentiment behind the text, such as positive, negative, or neutral, used for monitoring social media or customer service [

8];

named entity recognition (NER) is the identifying and classifying of specific objects in text, such as people, places, or organizations; it is a useful application for information extraction and question answering [

9];

natural language generation (NLG) is a software-based process to generate natural language outputs (text or spoken) with the use of methods of Artificial Intelligence, applied in creating various creative text formats such as scripts, music compositions, emails, letters, etc. [

10].

One of the domains intensely developed for digital text data processing is Natural Language Processing (NLP), which has become a key tool for working with large volumes of text data arising in the modern digital environment [

11]. NLP methods allow us to automate human language processing and solve new problems that go beyond the basic interpretation of text. Such tasks may include sentiment analysis, machine translation, or automated text summarization (

Table 1).

The development of NLP methods allows the creation of effective applications in computational linguistics. In particular, NLP methods have been used in new types of chatbots and translation systems, which allow text aspect analyzing and determining the emotional mood of text in social networks and open communication channels of many people. Methods of analyzing emotions and sentiments in social networks help assess public opinion, improve customer experience, detect fake news, prevent cyberbullying, and support users' psycho-emotional well-being. For example, one of the problems of sentiment analysis based on digital text analysis and classification is the detection of depressive states and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) [

12,

13]. As was shown in studies [

14,

15,

16] one of the key tasks within NLP is text content analysis, the process of discovering, classifying, and interpreting information contained in text data. Some of the existing systems for sentiment analysis are shown in

Table 2.

These systems can be used for analyzing the sentiment of text data from various sources such as social media, customer reviews, news articles, and more. Each of them has its own advantages and limitations that may affect their use in specific scenarios [

17,

18,

19].

The systems described in

Table 2 fail to meet the requirements of flexibility (working with limited emotion categories), adaptability to specific tasks (not tailored for specific domains), and transparency and control (risk of data access by third parties). Therefore, the development of such a system becomes a relevant task. Creating a custom system for labeling emotionally charged text offers several strategic advantages: flexibility, control, localization, and support for scientific research. This paper proposes a concept for developing a system that can be flexibly adapted for use across different languages, domains, and emotions, based on a combination of sentiment analysis, emotion detection, named entity recognition, and thematic analysis modules.

2. Research Task Rationale

The analysis of emotional texts is a crucial area in the fields of computational linguistics and information technology. Modern information society faces a growing need for effective methods to analyze and classify texts based on their emotional tone. This section explores the significance and applications of emotional text analysis across various domains, as well as the role of automated methods in addressing these challenges.

There are numerous approaches to classifying emotions. One influential model was developed by psychologist Paul Ekman, who identified six basic emotions with distinct physiological and facial expressions: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust [

20,

21]. This model serves as a foundation for automated systems that rely on detecting these fundamental emotional expressions through linguistic signals and sentiment lexicons (dictionaries containing emotionally charged words).

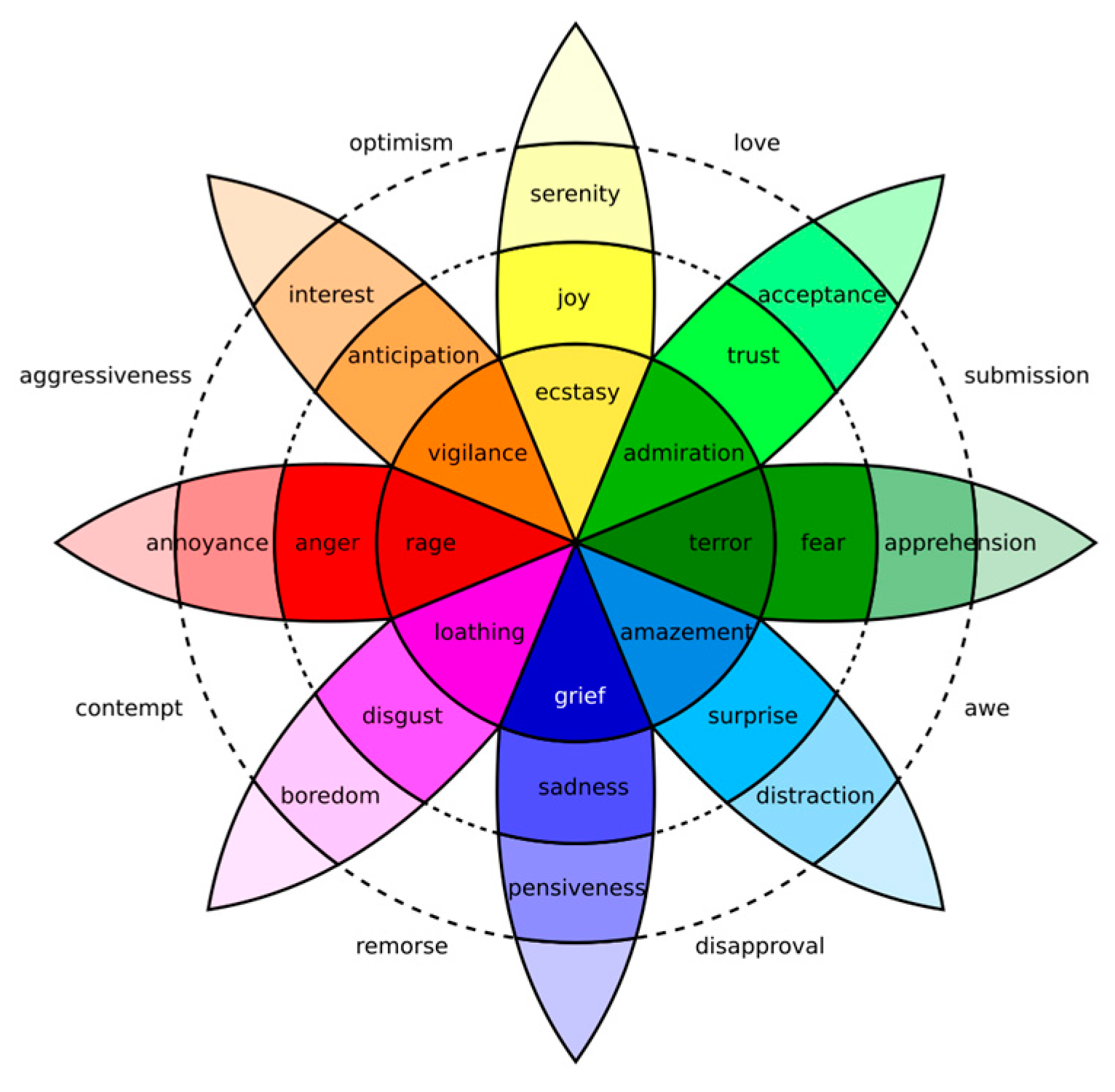

Another concept, Robert Plutchik's comprehensive model of emotions [

22], goes beyond basic emotions by proposing eight primary emotions (joy, sadness, anger, fear, trust, disgust, anticipation, and surprise) arranged in a circular structure (

Figure 1). This model suggests that emotions can be combined to create complex emotional states. For example, the combination of anger and fear may result in frustration, while the combination of joy and anticipation may signify excitement. Automated systems using this structure can focus on detecting combinations of emotionally charged words to capture these nuances of emotional states.

In addition to these models, an increasing number of studies are examining cultural differences in the expression of emotions [

23].

Human language is inherently ambiguous [

24,

25,

26]. Words often have multiple meanings depending on the context. Consider the sentence: "The meeting was noisy." Without additional contextual information, an automated system cannot determine whether "noisy" refers to a positive (very enjoyable) or negative (unpleasant) experience. Sarcasm in human communication presents a similar challenge. Automated systems often struggle to identify subtle cues that distinguish sarcasm from sincere emotions, potentially misinterpreting the intended meaning of the text.

Variations in language and sentiment depend on the subject domain. For instance, the language used in a medical report is likely to convey emotions differently than in a product review or a social media post. Automated systems require training data specific to the domain being analyzed to effectively classify expressions of emotion. A system trained on financial news articles may not accurately interpret the emotional language used on a gaming forum due to inherent differences in vocabulary and patterns of emotional expression in these domains.

Methodologies for analyzing the content of textual documents can be divided into four groups (

Table 3). Traditional methods are characterized by interpretability and efficiency but lack precision and nuance [

27,

28]. In the context of

Table 2, traditional methods refer to content analysis approaches that do not employ complex computational algorithms, such as machine learning or deep learning, and are typically based on simple automated text analysis, focusing on keywords or patterns. Machine learning models and statistical methods provide a balance between interpretability and accuracy, but their performance largely depends on training data and feature engineering. Deep learning methods offer high efficiency in solving complex analysis tasks but require significant computational resources and data [

29,

30]. As previously noted, each content analysis methodology has specific advantages and disadvantages (

Table 3).

The aim of the study is to develop a content analysis model for textual information containing emotionally charged vocabulary. This model will have a wide range of applications across various domains and enable reactive actions, such as moderation or the generation of targeted content based on the analysis of input text datasets.

To achieve this goal, the following objectives need to be solved:

examine methods for analyzing text content of various lengths, including the classification of text datasets by types of emotions and sentiments [

31,

32,

33];

analyze neural linguistic models for implementing modules for semantic, emotional, and thematic analysis, including an overview of existing datasets;

develop a conceptual model for tagging emotionally charged vocabulary;

conduct experimental studies on the impact of training parameters of neural network models (batch size, dataset size, number of epochs, optimizer type) and the use of scalers on the effectiveness of determining the emotional tone and sentiment of the text;

analyze the obtained results.

To achieve the stated goal, a comprehensive model consisting of four modules is proposed: emotional classification, named entity recognition, emotional tone analysis, and thematic analysis. In contrast to existing approaches, the study proposes for the first time to analyze text using a combination of methods for sentiment, emotion, named entity, and thematic analysis within a unified module. This module is preceded by text preprocessing, and its output is the formation of a prompt with the possibility of generating visual markers.

Using these modules, the study will summarize the text, highlight emotionally charged vocabulary, and identify the themes present in the text. This approach will provide a comprehensive understanding of the text’s tone, emotions, feelings, and sensations, as well as the topics discussed within it.

3. Results and Discussion

The work proposes a model for the automated tagging of emotionally charged vocabulary, integrating various computational linguistic techniques for text processing and analysis. This system is designed to decompose input text into manageable blocks, process these fragments using multiple analysis modules, and generate markers encapsulating the analysis results. These markers are subsequently used to create "prompts" following a pre-defined prompt template.

In the context of generative artificial intelligence models, a prompt refers to a set of instructions or cues that indicate what needs to be generated. Essentially, it is a starting point for the model's creative process. The goal of a prompt is to provide the AI model with enough information. Prompts can influence the style and tone of the generated content. For instance, they can specify whether the tone should be formal or informal for text, or whether an image should evoke a cheerful or tense mood.

In the context of the proposed model, a marker represents comprehensive contextual and syntactic information about a specific segment of text. By creating such markers, it is possible to generate prompts that effectively encapsulate all the necessary information for content generation based on plain text.

The model operates through a structured sequence of steps, beginning with the segmentation of the input text and concluding with the generation of markers used for various downstream applications. The key components and their interactions are described below.

The system accepts raw text, which can originate from various domains and contexts. The input text is first pre-processed to remove extraneous characters and standardize formatting. The pre-processed text is divided into smaller, coherent segments or "chunks," which are subsequently tokenized in the later components of the model.

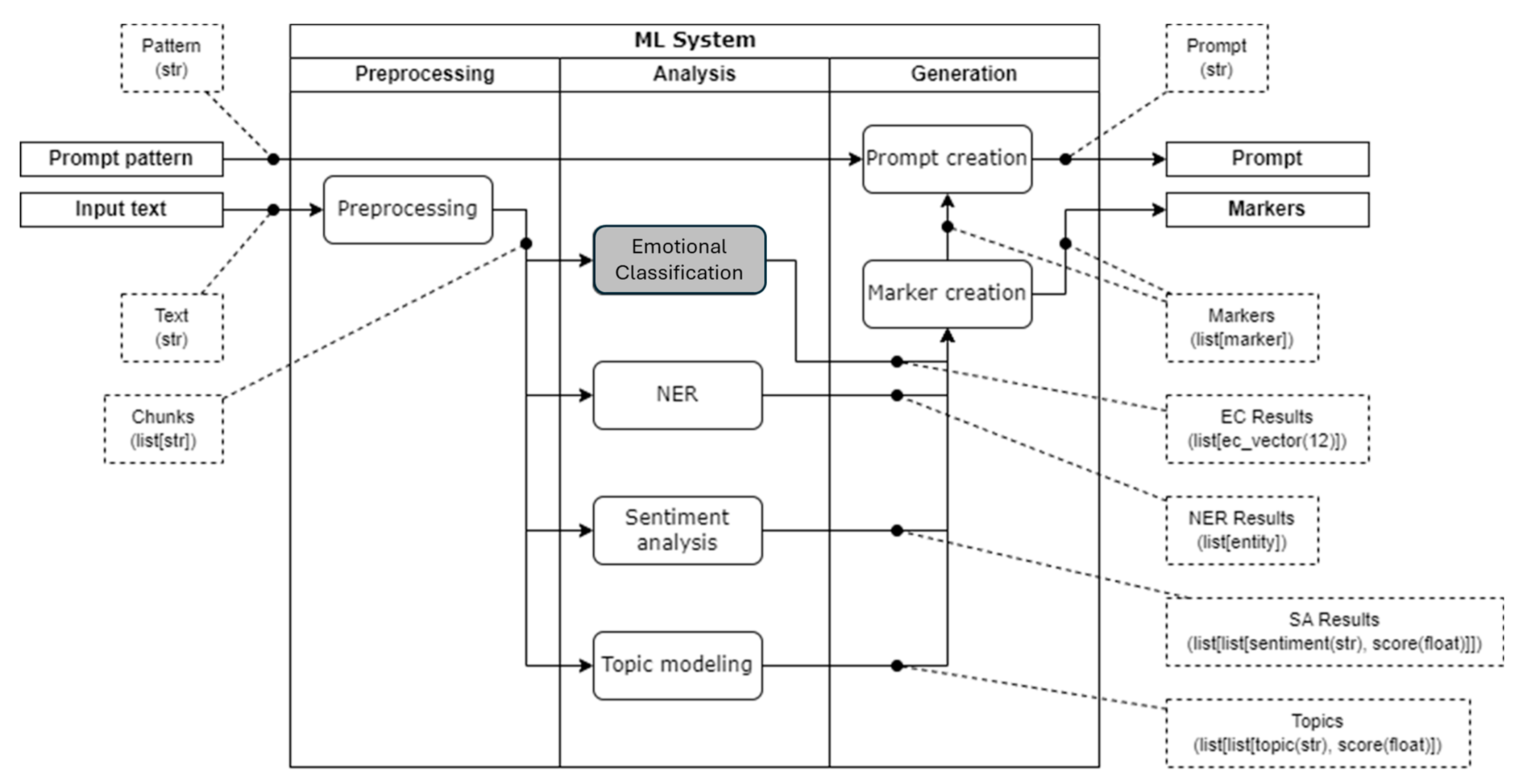

The architecture of the proposed model consists of three main modules:

preprocessing module;

content analysis module, which includes:

emotion classifier (identifies emotions expressed in the text, such as happiness, sadness, anger, or fear);

named entity recognition (NER) (extracts and classifies specific entities from the text, such as people, places, or organizations);

sentiment analysis (determines the overall positive, negative, or neutral sentiment of a text fragment);

topic modeling (detects hidden thematic groups or "topics" within a collection of documents);

generation module (includes marker creation and prompt generation), excluding text preprocessing (

Figure 2).

The output of the proposed model consists of generated prompts and markers.

Figure 2 demonstrates that all stages of the content analysis module influence the formation of the text marker, which serves as the basis for generating prompts used as input for generative models. This is a distinctive feature of the proposed model: the generation of prompts is not based solely on a single content analysis stage but on the combination of four interconnected stages.

To evaluate the impact of the emotion classifier, named entity recognition, sentiment analysis, and topic modeling on marker formation quality, the role of each stage should be assessed:

Emotional Classification focuses on the emotional context, determining the emotional state of the text on a deep emotional level;

Sentiment Analysis evaluates the general sentiment of the text by analyzing its polarity—positive, negative, or neutral tone;

NER identifies factual elements in the text, extracting named entities such as names, places, dates, and organizations;

Topic Modeling identifies the thematic context by clustering words based on their meaning.

Emotional Classification is pivotal for marker formation since emotions provide depth to the text, enabling the creation of a more informative and accurate marker for subsequent tasks. For example, a marker for news text or literary content would be incomplete without emotional context. Moreover, the task of emotion classification is scientifically challenging, requiring advanced machine learning methods, which underscores its relevance and significance. Hence, the experimental focus in this study will center on investigating the hyperparameters of the neural network model for emotion classification.

The preprocessing module precedes the content analysis module, which operates through four steps: performing emotion classification, named entity recognition, sentiment analysis, and topic modeling. These steps collectively contribute to marker formation. In this context, a marker is a comprehensive representation of contextual and syntactic information about a specific text segment.

The Emotion Classification block is a key component of the content analysis module, enabling the system to recognize and classify the emotional undertones of textual data. This process leverages pre-trained transformer models to accurately identify and classify a wide range of emotions in text segments.

The development of the emotion classifier involves several stages, including data collection and preparation, model training, evaluation, and deployment.

The EmotionClassifier model is built using libraries and tools in Python:

torch – the core library for PyTorch, used for building and training deep learning models;

pandas – used for data manipulation and analysis, particularly for handling datasets in tabular format;

numpy – used for numerical operations, providing support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices;

GradScaler and autocast from torch.cuda.amp – utilized for mixed-precision training, which helps speed up training and reduce memory usage without sacrificing model accuracy;

DataLoader and Dataset from torch.utils.data – these classes are used for efficient data processing and loading during the training process;

classification_report from sklearn.metrics – provides a detailed report on precision, recall, F1 score, and support for each class, which is essential for evaluating model performance;

train_test_split from sklearn.model_selection – used to split the dataset into training and testing sets to evaluate the model’s performance on unseen data;

AdamW and get_linear_schedule_with_warmup from transformers – optimizer and learning rate scheduler used for efficient training of the transformer model;

DistilBertTokenizer and DistilBertForSequenceClassification from transformers – the tokenizer and model class for DistilBERT, a lighter and faster version of BERT specifically designed for sequence classification tasks.

To conduct research and solve the task of classifying the emotions in textual information, the DistilBERT model (Distilled Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) was used in this study. DistilBERT is a simplified version of the BERT model. The initialization function of the EmotionClassifier loads the pre-trained model distilbert-base-uncased. This model, being a lighter and faster variant of BERT, is well-suited for sequence classification tasks. The EmotionClassifier inherits from DistilBertForSequenceClassification.

The activation function is a sigmoid function, which maps input values to a range between 0 and 1, effectively converting output logits into probabilities. Each probability value indicates the likelihood that the input text corresponds to a specific emotion.

The output of the model is a vector of 13 values, each representing the probability that the input text belongs to one of 13 predefined emotion categories:

joy;

anger;

sadness;

disgust;

fear;

trust;

surprise;

love;

confusion;

anticipation;

shame;

guilt;

noemo (no emotion).

This vector can be considered a 13-dimensional representation of the text in the emotional space, providing a comprehensive assessment of the emotional content of the text.

The detailed configuration and adaptation of the EmotionClassifier ensure that it effectively classifies text into the specified emotional categories, leveraging the robust capabilities of transformer models and the efficiency of PyTorch utilities.

The EmotionClassifier was trained using datasets described in

Table 4 [

34,

35,

36].

Each dataset was cleaned to remove any auxiliary information that could potentially interfere with the training process of the emotion classification model.

The dataset was divided into three parts:

training set (80%, i.e., 11,064) – used for training the model;

validation set (10%, i.e., 1,366) – used to fine-tune the model's hyperparameters and evaluate its performance during training;

test set (10%, i.e., 1,366) – used to assess the final performance of the model after training.

After evaluating possible dataset splits (50:25:25, 70:15:15, 80:10:10), the 80:10:10 split was preferred because increasing the proportion of the training set ensures better generalization of the model, especially for large datasets. This reduces the risk of underfitting, where the model fails to capture important patterns due to insufficient data.

The maximum length of each sequence in the dataset is 128 tokens. This means that any text longer than 128 tokens is truncated, while shorter texts are padded to ensure uniform length. This uniformity is necessary for efficient parallel processing on massively parallel computing devices (e.g., GPUs). The length of 128 tokens was chosen as it approximately matches the maximum tokenized length of a tweet, which forms the majority of the training data.

4. Methodology of Experiments

During classification, the model processes data in batches, where the batch size is a configurable parameter. Batching not only accelerates computations but also helps better utilize GPU resources, contributing to more efficient training.

Training for 2 epochs resulted in an accuracy of approximately 60%. Training beyond 3 epochs led to overfitting, where the model performs well on training data but poorly on validation data. Thus, 3 epochs established a balance between training time and performance. The training was conducted on an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU with 12 GB of video memory. The AdamW optimizer was used, which adjusts learning rates based on the average of the first and second moments of gradients and includes weight decay for better regularization. The experiments involved evaluating losses and accuracy on the validation dataset after each epoch. The model with the lowest validation loss was saved as the most effective one.

On the specified hardware (NVIDIA RTX 3060), each epoch takes approximately 12 minutes. After training is completed, the model is tested on the test set.

The following experiments assess the impact of various parameters on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content by the chosen model and the training speed, specifically:

assessment of the impact of dataset size on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content and training speed;

assessment of the impact of batch size on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content and training speed;

assessment of the impact of the number of epochs on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content;

assessment of the impact of the optimizer on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content and training speed;

assessment of the impact of the scheduler on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content and training speed;

assessment of the impact of the scaler on the accuracy of emotional classification of text content and training speed.

Among the existing metrics for evaluating the quality of model training and testing, such as Accuracy, F1-Score, Precision, and Recall, Accuracy is the fundamental metric for classification tasks. It indicates the proportion of correctly predicted outcomes to the total number of predictions. The Accuracy metric is suitable for balanced datasets (a common scenario in text emotion classification tasks), serves for preliminary model evaluation for further improvements, and allows comparison of the impact of various parameters on performance. Other metrics can be utilized in subsequent research stages when the focus shifts to detailed error analysis or optimization for specific classes.

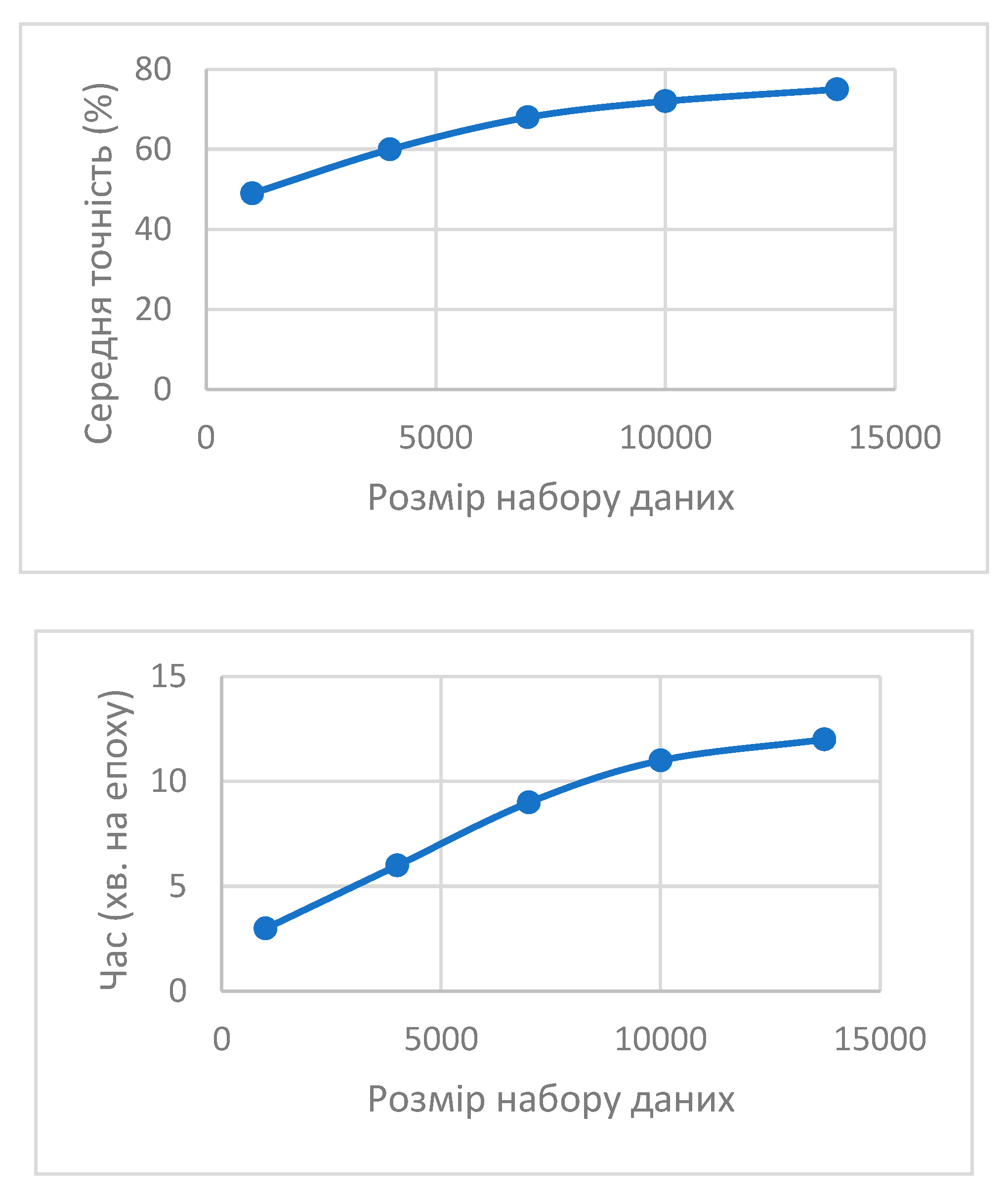

The results show that increasing the dataset size improves model accuracy. Through experimentation, a dataset size of approximately 13,000 records was determined to balance accuracy and time, achieving an accuracy of 75% with an acceptable epoch time of 12 minutes.

Figure 3.

The impact of dataset size on the accuracy of text emotion classification and training speed.

Figure 3.

The impact of dataset size on the accuracy of text emotion classification and training speed.

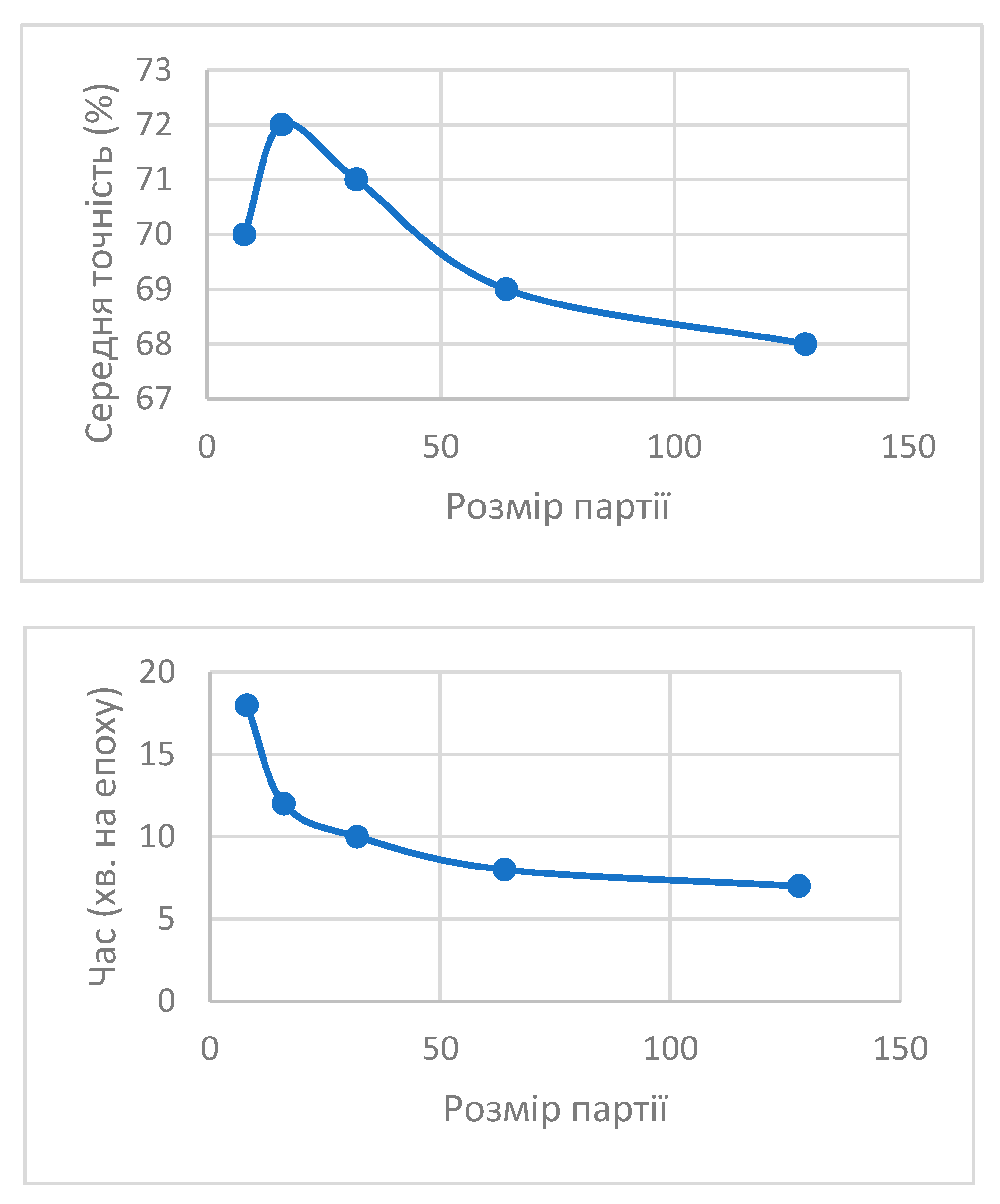

The batch size was varied to evaluate its impact on model performance and computational efficiency (

Table 6). Analysis of the results shows that the highest accuracy of 72% is achieved with a batch size of 16, with a training time of 12 minutes per epoch. Increasing the batch size to 128 reduces accuracy to 68%, while the epoch time decreases to 7 minutes. Therefore, a batch size of 16 is recommended as it provides the best balance between accuracy and training time.

Research and assessment of training time for the text content classification model are important for practical considerations, particularly when:

the model requires updates (fine-tuning) with new data, such as adding new emotions to an existing emotion classification system;

the model needs to incorporate a new language in a multilingual text emotion analysis system.

Thus, the faster the model trains, the more efficiently it can be updated without significant downtime in the system's operation.

Figure 4.

Impact of batch size on training time and average accuracy.

Figure 4.

Impact of batch size on training time and average accuracy.

The model was trained for different numbers of epochs to determine the effect of the number of epochs on accuracy and overfitting (

Table 5).

The model shows an accuracy increase up to 72% after three epochs of training. Further increasing the number of epochs leads to overfitting. In the fourth epoch, accuracy decreases to 70%, and in the fifth epoch, it drops further to 68%.

Testing different optimizers allowed for the evaluation of their impact on the training process and model accuracy, including SGD, Adam, AdamW, RMSprop, and Adagrad (

Table 6).

Table 6.

Impact of optimizer on accuracy and training speed.

Table 6.

Impact of optimizer on accuracy and training speed.

| Optimizer |

Accuracy (%) |

Training speed (min per epochs) |

| SGD |

65 |

14 |

| Adam |

70 |

12 |

| AdamW |

72 |

12 |

| RMSprop |

67 |

13 |

| Adagrad |

64 |

15 |

The AdamW optimizer demonstrated the highest accuracy of 72% with an average training time of 12 minutes per epoch. Other optimizers, such as SGD (65%) or Adagrad (64%), showed lower accuracy. Therefore, AdamW is recommended as it provides the most balanced results in terms of time and classification accuracy.

The final experiment evaluated the impact of the chosen scheduler on the efficiency and accuracy of classification (

Table 7).

The highest accuracy of 73% is achieved by the model without using a scheduler, but the training time significantly increases to 25 minutes per epoch. The Linear with Warmup scheduler ensures an accuracy of 72% within 12 minutes per epoch. Thus, using Linear with Warmup is recommended to maintain high accuracy while minimizing training time.

The use of mixed precision training with GradScaler was analyzed to evaluate its impact on training efficiency and duration.

Without using GradScaler, the accuracy was 70%, and the training time was 16 minutes per epoch. With GradScaler, the accuracy increased to 72%, and the training time decreased to 12 minutes (

Table 8).

Through these comprehensive experiments, it was determined that an optimal configuration for the EmotionClassifier involved the full dataset size of 13,736 records, a batch size of 16, training over 3 epochs, using the AdamW optimizer, and applying a linear scheduler with warmup. Mixed precision training with GradScaler also improved the speed and efficiency of training. This information is crucial for fine-tuning the model to achieve the best balance between performance and computational resource utilization.

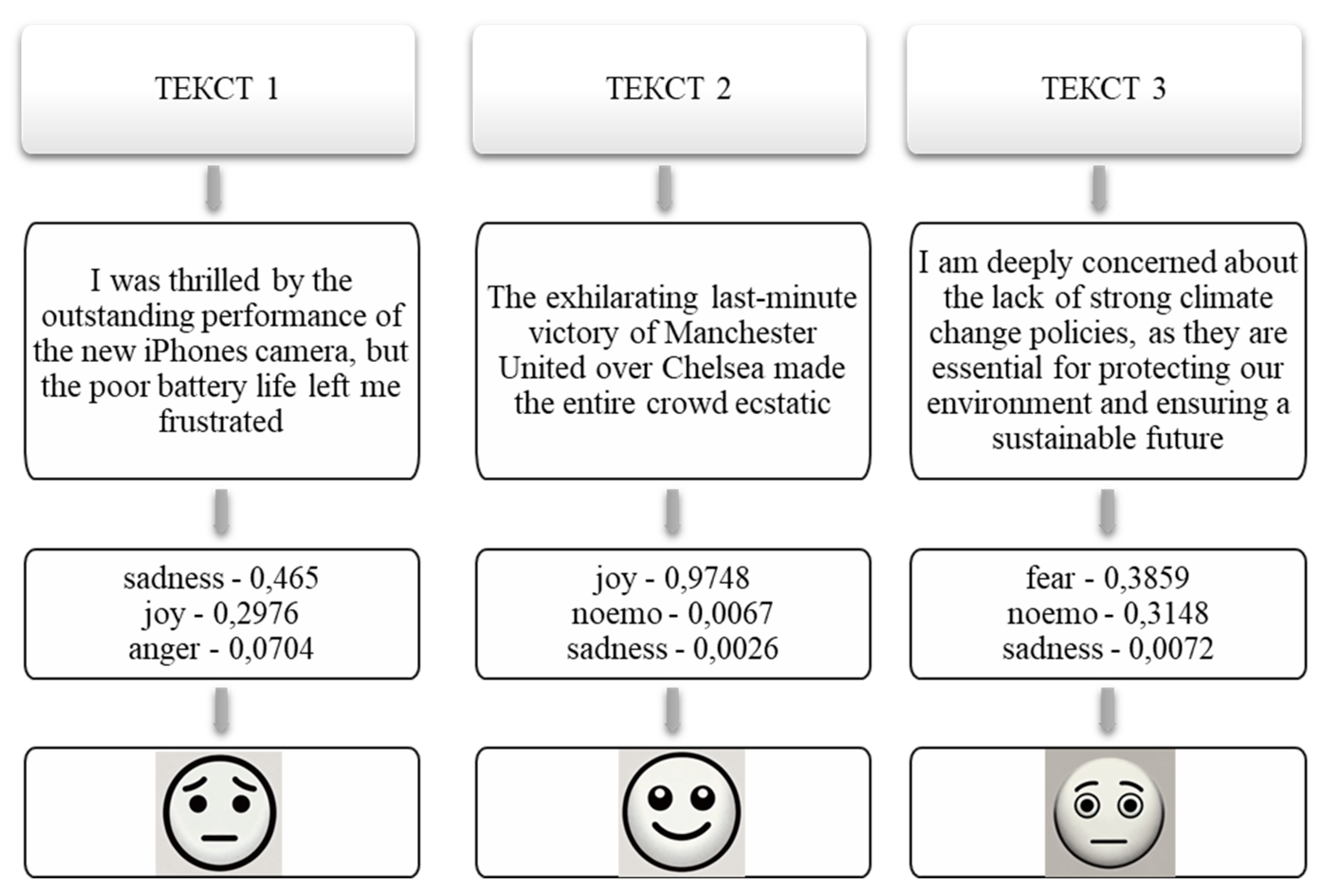

Examples of the operation of the emotion classification module for textual content are provided in

Figure 5. Explanations are given below:

Text 1 – "I was thrilled by the outstanding performance of the new iPhone's camera, but the poor battery life left me frustrated."

Text 2 – "The exhilarating last-minute victory of Manchester United over Chelsea made the entire crowd ecstatic."

Text 3 – "I am deeply concerned about the lack of strong climate change policies, as they are essential for protecting our environment and ensuring a sustainable future."

Table 11.

Demonstration of results from the emotion classification module.

Table 11.

Demonstration of results from the emotion classification module.

| Emotion |

Text 1 |

Text 2 |

Text 3 |

| joy |

0,2976 |

0,9748 |

0,0017 |

| anger |

0,0704 |

0,0022 |

0,0011 |

| sadness |

0,465 |

0,0026 |

0,0072 |

| disgust |

0,0104 |

0,0007 |

0,0006 |

| fear |

0,024 |

0,0018 |

0,3859 |

| trust |

0,0002 |

0,0017 |

0 |

| surprise |

0,0051 |

0,0015 |

0,0006 |

| love |

0,0025 |

0,0002 |

0,0002 |

| noemo |

0,0303 |

0,0067 |

0,3148 |

| confusion |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| anticipation |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| shame |

0,0018 |

0 |

0,0002 |

| guilt |

0,0032 |

0 |

0,0002 |

The provided results of emotion classification for the three sentences demonstrate varying levels of intensity for different emotions. The analysis will focus on interpreting these results and understanding the emotional tone of each sentence based on the given scores.

Text 1 – "I was thrilled by the outstanding performance of the new iPhone's camera, but the poor battery life left me frustrated":

joy (0.2976): the highest emotion score for this sentence is joy, reflecting the positive sentiment about the iPhone's camera performance;

sadness (0.465): sadness is also significant, indicating disappointment with the battery life;

anger (0.0704): anger is present but not dominant, suggesting mild frustration;

other emotions: minor traces of disgust, fear, trust, surprise, and love indicate a complex emotional reaction, but they are not predominant;

noemo (0.0303): a small portion of the sentence evokes no strong emotions.

The sentence evokes a mix of joy and sadness, primarily due to the contrasting impressions of the iPhone's camera and battery life.

Text 2 – "The exhilarating last-minute victory of Manchester United over Chelsea made the entire crowd ecstatic":

joy (0.9748): joy overwhelmingly dominates this sentence, aligning with the positive and exciting nature of the content;

other emotions: negligible levels of anger, sadness, disgust, fear, trust, surprise, and love indicate a clear and strong positive emotional response;

noemo (0.0067): a very small portion of the sentence elicits no specific emotions.

The sentence is predominantly joyful, reflecting the elation and ecstasy of the crowd after the victory.

Text 3 – "I am deeply concerned about the lack of strong climate change policies, as they are essential for protecting our environment and ensuring a sustainable future":

fear (0.3859): fear is the predominant emotion, highlighting concern about climate change policies.

sadness (0.0072): sadness is present but to a much lesser extent, possibly reflecting worry.

noemo (0.3148): a significant portion of the sentence is neutral or not strongly emotional, indicating a more factual tone.

other emotions: traces of anger, disgust, trust, surprise, love, shame, and guilt suggest a mix of concern and urgency.

This text primarily evokes fear, with a notable neutral component, indicating serious concern and a call to action on climate policy.

Text 1 demonstrates a balanced mix of joy and sadness, reflecting the speaker's ambivalence about the iPhone's features. Text 2 is dominated by joy, vividly expressing excitement and happiness over the sports victory. Text 3 is primarily driven by fear, indicating concern about climate change, with a significant neutral component suggesting a factual tone.

These results highlight the system's ability to capture complex emotional nuances and provide valuable insights into the sentiments and emotional content of various sentence types.

5. Conclusion

The main goal of the conducted work has been achieved—the development of a conceptual model for a system to tag emotionally colored lexicon. This system has a wide range of applications in various fields and enables reactive actions, such as content moderation or generation tailored to specific audiences, based on the analysis of incoming textual data.

The proposed conceptual model for the emotionally colored lexicon tagging system comprises four modules: emotional classification, named entity recognition, emotional tone analysis, and topic modeling. These modules enable text summarization, extraction of emotionally colored lexicon, and identification of themes present in the text. This approach provides a comprehensive understanding of the text's mood, emotions, feelings, and sensations, as well as the topics discussed.

Experimental research was conducted to evaluate the impact of training parameters for the DistilBERT neural network model, such as batch size, dataset size, number of epochs, optimizer type, and their influence on the accuracy and speed of classifying textual data based on its emotional tone and sentiment. The experiments demonstrated the necessity of using a gradient scaler to reduce training time for neural network classifiers.

The results of the experiments underscore the importance of tuning training parameters to improve model accuracy and identify the recommended architecture for the DistilBERT neural network with a transformer-based architecture: a recommended dataset size of 13,000 entries, a batch size of 16, three epochs for training, the AdamW optimizer, the Linear with Warmup scheduler, and GradScaler. These settings achieve an accuracy of 72–75% with minimal computational costs and training time of approximately 12 minutes per epoch on a mass-parallel processor—an NVIDIA RTX 3060 with Ampere architecture.

The experimental results confirm the viability of the developed model for tasks such as text classification, emotion analysis, and automated content generation. The examples provided demonstrate the system's ability to capture complex emotional nuances and provide valuable insights into the sentiments and emotional content of different types of sentences. The outcomes and configurations of the neural network model architecture can be beneficial for automating content creation processes for media platforms, blogs, advertisements, and other areas where content creation based on textual information is required.

Future project development includes conducting similar research on the Sentiment Analysis module to determine the overall positive, negative, or neutral sentiment of text fragments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.I., A.K. and E.Z.; methodology, O.B. and D.Z.; software, D.Z. and P.B.; validation, H.I., D.Z. and P.B.; formal analysis, E.Z., V.L.; investigation, A.K. and O.B.; resources, P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B. and D.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.Z., V.L.; visualization, H.I.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, O.B.; funding acquisition, E.Z. and V.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the grants APVV-23-0033 and APVV-18-0027, the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic under the grant VEGA 1/0858/21

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data for the experimental study are indicated in the paper’s text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NLP |

Natural Language Processing |

| BERT |

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| NLG |

Natural Language Generation |

| NER |

Named Entity Recognition |

| PTSD |

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| VAD |

Valence-Arousal-Dominance |

| TEC |

Textual Emotion Corpus |

| ISEAR |

International Survey on Emotion Antecedents and Reactions |

| SSEC |

Sarcasm Sentiment Emotion Corpus |

| GPUs |

Graphics Processing Units |

| SGD |

Stochastic Gradient Descent |

References

- Barkovska, Olesia et al. Analysis of the impact of the contextual embeddings usage on the text classification accuracy. Radioelectronic and Computer Systems, [S.l.], v. 2024, n. 3, p. 67-79, aug. 2024. ISSN 2663-2012. Available at: http://nti.khai.edu/ojs/index.php/reks/article/view/reks.2024.3.05. Date accessed: 09 dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barkovska, O., Kholiev, V., Havrashenko, A., Mohylevskyi, D., & Kovalenko, A. (2023). A Conceptual Text Classification Model Based on Two-Factor Selection of Significant Words. In COLINS (2) (pp. 244-255).

- Wang, Jiapeng, and Yihong Dong. ‘Measurement of Text Similarity: A Survey’. Information, vol. 11, no. 9, Aug. 2020, p. 421. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Nassif, Ali Bou, et al. ‘Speech Recognition Using Deep Neural Networks: A Systematic Review’. IEEE Access, vol. 7, 2019, pp. 19143–65. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Havrashenko, Anton, and Olesia Barkovska. ‘ANALYSIS OF TEXT AUGMENTATION ALGORITHMS IN ARTIFICIAL LANGUAGE MACHINE TRANSLATION SYSTEMS’. Advanced Information Systems, vol. 7, no. 1, Mar. 2023, pp. 47–53. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Maksymenko, Daniil, et al. ‘Improving the Machine Translation Model in Specific Domains for the Ukrainian Language’. 2022 IEEE 17th International Conference on Computer Sciences and Information Technologies (CSIT), IEEE, 2022, pp. 123–29. DOI.org (Crossref).

- Wu, Peng, et al. ‘Social Media Opinion Summarization Using Emotion Cognition and Convolutional Neural Networks’. International Journal of Information Management, vol. 51, Apr. 2020, p. 101978. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, Ganesh, et al. ‘Multimodal Sentimental Analysis for Social Media Applications: A Comprehensive Review’. WIREs Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, vol. 11, no. 5, Sept. 2021, p. e1415. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, Nasser, and Saad Alanazi. ‘The Impact of Using Different Annotation Schemes on Named Entity Recognition’. Egyptian Informatics Journal, vol. 22, no. 3, Sept. 2021, pp. 295–302. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, Anabela, et al. An Outlook on Natural Language Generation. 2023, pp. 27–34. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, Jan, et al. ‘The State of the Art of Natural Language Processing—A Systematic Automated Review of NLP Literature Using NLP Techniques’. Data Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 3, Aug. 2023, pp. 707–49. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Burdisso, Sergio G., et al. ‘A Text Classification Framework for Simple and Effective Early Depression Detection over Social Media Streams’. Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 133, Nov. 2019, pp. 182–97. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Santos, Wesley, et al. ‘Mental Health Prediction from Social Media Text Using Mixture of Experts’. IEEE Latin America Transactions, vol. 21, no. 6, June 2023, pp. 723–29. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Kou, Gang, et al. ‘Evaluation of Feature Selection Methods for Text Classification with Small Datasets Using Multiple Criteria Decision-Making Methods’. Applied Soft Computing, vol. 86, Jan. 2020, p. 105836. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Rezaeinia, Seyed Mahdi, et al. ‘Sentiment Analysis Based on Improved Pre-Trained Word Embeddings’. Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 117, Mar. 2019, pp. 139–47. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, Ammar Ismael. ‘Survey on Supervised Machine Learning Techniques for Automatic Text Classification’. Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 52, no. 1, June 2019, pp. 273–92. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Bondielli, Alessandro, and Francesco Marcelloni. ‘A Survey on Fake News and Rumour Detection Techniques’. Information Sciences, vol. 497, Sept. 2019, pp. 38–55. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Iftikhar, et al. ‘Fake News Detection Using Machine Learning Ensemble Methods’. Complexity, edited by M. Irfan Uddin, vol. 2020, Oct. 2020, pp. 1–11. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, Mahdi. ‘Web Page Classification: A Survey of Perspectives, Gaps, and Future Directions’. Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 79, no. 17–18, May 2020, pp. 11921–45. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Ekman, Paul. ‘Facial Expressions of Emotion: New Findings, New Questions’. Psychological Science, vol. 3, no. 1, Jan. 1992, pp. 34–38. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Ekman, Paul. ‘An Argument for Basic Emotions’. Cognition and Emotion, vol. 6, no. 3–4, May 1992, pp. 169–200. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, Robert. ‘A Psychoevolutionary Theory of Emotions’. Social Science Information, vol. 21, no. 4–5, July 1982, pp. 529–53. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, Batja, and Nico H. Frijda. ‘Cultural Variations in Emotions: A Review.’ Psychological Bulletin, vol. 112, no. 2, 1992, pp. 179–204. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Carl W. ‘Semantic Text Analysis: On the Structure of Linguistic Ambiguity in Ordinary Discourse’. Text Analysis for the Social Sciences, edited by Carl W. Roberts, 1st ed., Routledge, 2020, pp. 55–78. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Yadav, Apurwa, et al. ‘A Comprehensive Review on Resolving Ambiguities in Natural Language Processing’. AI Open, vol. 2, 2021, pp. 85–92. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Montejo-Ráez, Arturo, and Salud María Jiménez-Zafra, editors. Current Approaches and Applications in Natural Language Processing. MDPI Books, 2022.

- Rezaeenour, Jalal, et al. ‘Systematic Review of Content Analysis Algorithms Based on Deep Neural Networks’. Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 82, no. 12, May 2023, pp. 17879–903. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Schöpper, Henning, and Wolfgang Kersten. Using Natural Language Processing for Supply Chain Mapping: A Systematic Review of Current Approaches. May 2021. DOI.org (Datacite). [CrossRef]

- Pintas, Julliano Trindade, et al. ‘Feature Selection Methods for Text Classification: A Systematic Literature Review’. Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 54, no. 8, Dec. 2021, pp. 6149–200. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Gasparetto, Andrea, et al. ‘A Survey on Text Classification Algorithms: From Text to Predictions’. Information, vol. 13, no. 2, Feb. 2022, p. 83. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Nandwani, Pansy, and Rupali Verma. ‘A Review on Sentiment Analysis and Emotion Detection from Text’. Social Network Analysis and Mining, vol. 11, no. 1, Dec. 2021, p. 81. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Dawei, Wang, et al. ‘A Literature Review on Text Classification and Sentiment Analysis Approaches’. Computational Science and Technology, edited by Rayner Alfred et al., vol. 724, Springer Singapore, 2021, pp. 305–23. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Kusal, Sheetal, et al. ‘A Systematic Review of Applications of Natural Language Processing and Future Challenges with Special Emphasis in Text-Based Emotion Detection’. Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 56, no. 12, Dec. 2023, pp. 15129–215. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Sarsam, Samer Muthana, et al. ‘Sarcasm Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms in Twitter: A Systematic Review’. International Journal of Market Research, vol. 62, no. 5, Sept. 2020, pp. 578–98. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Zad, Samira, et al. ‘Emotion Detection of Textual Data: An Interdisciplinary Survey’. 2021 IEEE World AI IoT Congress (AIIoT), IEEE, 2021, pp. 0255–61. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, Shrikala. ‘Review of Databases Used for Text Based Emotion Detection’. 2024 MIT Art, Design and Technology School of Computing International Conference (MITADTSoCiCon), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5. DOI.org (Crossref). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).