1. Introduction

Rich mineral content of seawater has led to its extensive utilization for salt production. Indonesia has 43,052.10 hectares of salt land, with approximately 59.7% dedicated to salt production [

1]. Salt harvesting produces a product known as bittern—a concentrated seawater solution with high mineral content. Bitterns contain substantial amounts of potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg), which are highly beneficial for health applications.

Currently, seawater mineral concentrate has been utilized in health sector as a raw material for supplements and multivitamins due to high mineral content [

2]. As the demand for minerals grows, synthetic mineral sources from mining are diminishing, making concentrated seawater to be a viable alternative. Indonesia has very long coastline thus provide natural resource for deep seawater as raw material for mineral concentrate. Despite abundant potential of source, the quality of these materials has not been extensively studied. Therefore, the standardization of quality to be used as raw materials for multivitamin is highly needed. The quality of deep seawater as raw material can be assessed through the physical, chemical, and biological parameters [

3]. The official standard concerning the quality of water for health purposes including pharmaceutical grade material for oral formulations such as multivitamin has not been published. Yet, the available standard was adopted from those for drinking water with some additional quality standards.

Due to the increased community income and quality life standard, the trend of healthy lifestyle and disease prevention has also been increased thus the needs for multivitamins to improve health and nutrient intake are also growing up. In the pharmaceutical sector, it is imperative to characterize and standardize the raw materials thoroughly to guarantee the safety and quality of final product. With regards to deep seawater as raw material for supplement, pollution number is one of the factors contributing to the quality. Consumption of contaminated seawater whether due to physical, chemical, or microbiological pollutants exceeding human tolerance levels can pose serious health risks and safety [

4].

Deep seawater concentrate has enormous potential to be used as a raw material in the development of supplements as a source of minerals in multivitamins [

2]. Seawater is a natural resource that is abundantly available and will never run out without the need to be cultivated. Standardization, which is a must in maintaining the quality of raw materials for pharmaceutical preparations, must also be applied in the development of the concentrates as a source of raw materials for supplements. To enhance and broaden insights concerning the safety and quality of deep seawater concentrate, validation and quality control need to be employed as requirement of pharmaceuticals raw material. Due to lack of compendial method, the quality control including physical, chemical, and biological parameters in this experiment were based on the reference of Seawater Quality standard by the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry year 2016. Quantitative determination of mineral/metal content can be done using ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectrometry) and XRF (X-Ray fluorescence) [

5,

6].

The uniform shape of the granules provides good homogeneity in the mixing process as well as ability in dosage adjustment, thus more practical and efficient in the manufacturing process whether in the form of tablets, capsules, or other solid-form products [

7]. According to previous research, high mineral content in solid material gives very hygroscopic properties to the powder due to susceptibility in absorbing moisture [

8]. Zhang

et al. has conducted research related to the hygroscopic properties of the mineral content by studying the properties of sodium and potassium salts during storage [

9]. The hygroscopic character of pharmaceutical raw materials is influenced by various things, including the stages of the process, manufacturing, packaging, storage, and distribution. This property also greatly affects the stability, appearance, and efficiency of the raw material. Therefore, it is important to study and classify the problem of raw materials based on their hygroscopic properties and provide the information of product handling of these materials [

10].

In the development of pharmaceutical and nutraceutical, the solid dosage forms such as tablets, capsules, and powders that are hygroscopic in nature greatly affect the physicochemical stability, therapeutic performance, and shelf life of the product. The formulation strategies that have been used to overcome this problems in the form of oral solid preparations of drugs/nutraceuticals are; (1) film coating, (2) encapsulation by spray drying or coagulation, (3) co-processing with excipients, and (4) crystal engineering by co-crystallization [

11]. Mabrouki (2022) has conducted research related to the formulation and development of tablets from

Herniaria Glabra L extract which is known to be hygroscopic, and improved its properties and physical stability by using a film coating system [

12].

In the context of developing a non-hygroscopic solid pharmaceutical dosage forms derived from deep seawater concentrate which is rich in minerals as main ingredient for supplements and multivitamins, further research is highly needed related to its stability and formulation. By preparing the material with good quality and stability, the potential of deep seawater concentrate as a source of minerals for supplements will increase thus will provide greater benefits in supporting human’s health and welfare [

13,

14]. This study aims to provide information on the quality of mineral concentrates from deep seawater to fulfill requirement of pharmaceutical grade in the form of granules as a source of raw material for minerals and multivitamins. The information provided includes the standardization of product as raw materials for supplements and formulation aspects to improve the stability of deep seawater which is very hygroscopic granule to have better stability so that they can be used as raw material for multivitamin. Moisture protection of these material will increase its stability which lead to the ensurement of the micronutrients availability in the form of vitamins, minerals, and trace elements that play a main role in providing the nutrients needed to support optimal growth and development in children [

15].

3. Discussion

Analysis of Quality Parameters and Contaminants

Physical parameter testing is crucial to determine the quality of the sample and can be used as preliminary visual screening. Physical characteristics of the deep seawater concentrate were conducted on both the sample from Madura seawater and marketed concentrate water as standard (

Table 1). As parameters, the quality standard to be examined were those which used as quality criteria for drinking water and seawater [

16,

17].

Color testing using spectrophotometry revealed that the sample of seawater concentrate from Madura had a Pt/Co scale value of 333, while that of marketed product was 570. Higher Pt/Co scale values indicate greater water turbidity or color intensity, often attributed to high organic content [

21]. Both samples exceeded the permitted quality requirements range for drinking water (Pt/Co scale value of 15) and demonstrated more intense turbidity due to more concentrated seawater thus higher content of minerals and other chemical components.

Upon organoleptic examination, Madura’s seawater concentrate displayed a distinct aroma which may attributed to higher salt after many of coacervation during concentration process. The marketed product from seawater mineral also possessed a faint odor, albeit less pronounced compared to that from Madura’s seawater.

In terms of total suspended solids (TSS) analysis by gravimetric method, it was found that both Madura’s seawater and the marketed product exhibited values of < 7.7. This suggests that TSS in both samples which comprise as solid particle impurities like mud, dust, organic substances, and dissolved particles were within the acceptable range for drinking water standards.

- b.

Chemical Parameters

Chemical parameter testing was conducted to assess the quality of the samples. Due to lack of compendial standard, the parameter of quality to be examined were basen on those which used as for drinking water and seawater [

16,

17].

Based on their chemical characteristics (

Table 2) it was found that the pH of both Madura seawater and the marketed product seawater mineral were in the range of permissible value for drinking water standards. The pH of seawater is influenced by its carbon dioxide content, which generates carbonate and bicarbonate ions, releasing hydrogen ions and consequently increasing the seawater’s pH. However, during the evaporation process, most of the alkaline components—such as carbonate and bicarbonate ions—evaporate into calcium carbonate. This leads to a lower pH in the seawater concentrate compared to natural seawater [

2].

The salinity value of Madura seawater concentrate was 311%, while marketed product was 283%. High salinity value of both samples was due to the evaporation process, which led to an increase in salt concentration containing minerals such as magnesium and potassium [

22]. This process also affects the Baumé degree, which influences the density of the fluid with a linear relationship. Higher Baume degree resulted in higher salinity [

1].

The dissolved oxygen content of Madura seawater concentrate had a value of 2.1 mg/L, while that of the marketed product was 3.1 mg/L. However, both samples had the DO levels below the permissible range of at least 6 mg/L. This can be attributed to the evaporation process during production of the concentrate, which cause a decrease in oxygen levels as dissolved oxygen molecules bound to water can also evaporate. As shown in previous data, evaporation process also affected the salinity values of the samples, to which higher salinity leads to decreased solubility of dissolved oxygen [

23]. Biological oxygen demand (BOD) value of Madura seawater was 304 mg/L, which obviously did not meet the permissible quality standard of 2 mg/L. The discrepancy could be attributed to the evaporation process, which elevates the BOD value. As water evaporates, it leaves all the containing mineral behind to be more concentrated, thereby increasing the concentration of residual matter. Additionally, evaporation contributes to higher salinity levels, resulting in reduced dissolved oxygen content. The reduction in oxygen availability hence can elevate BOD levels, as decomposer organisms require oxygen to degrade organic matter [

24].

The results indicated that Ammonia level in both samples were below the maximum value of 1.5 mg/L (according to Indonesia’s Minister of Health Regulation No. 492/2010 regarding Drinking Water Quality Requirements). The ammonia level in Madura seawater was lower than that of the marketed product. High level of ammonia can lead to unpleasant odors of water due to contaminants such as organic waste and chemicals. Furthermore, it can disrupt the digestive system, causing symptoms like nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Therefore, level of ammonia can be emphasized as one of the important factor in maintaining water quality to be within permissible limits [

25].

Phosphate level of Madura seawater had a value within the acceptable drinking water quality standard, which must be below 0.2 mg/L. It exhibited lower phosphate level (0.096 mg/L), even when compared to the marketed product seawater which was 0.23 mg/L. A low level of phosphate signifies better water quality as phosphate is considered as a crucial nutrient compound that significantly impacts water productivity. In aquatic environments, phosphorus exists in the form of dissolved inorganic compounds, namely orthophosphate and polyphosphate. Elevated phosphate levels can trigger eutrophication and uncontrolled algae proliferation, leading to the release of algal toxins that pose health risks to both humans and animals [

26].

The results of nitrate level determination from both samples showed that their values were less than the allowable drinking water quality standard, which must be less than 10 mg/L. Nitrate is a nutrient that supports protein synthesis in animals and plants. When the concentration exceeds 0.2 mg/L, it can lead to eutrophication and algae blooming which will impact the ecosystem biodiversity and water quality. Biochemical processes resulted from the oxidation of nitrogen compounds can influence nitrate level in water. Nitrate level can also be influenced by factors such as pH, temperature, dissolved oxygen, and salinity [

27]. Nitrite is an intermediate form between ammonia and nitrate that quickly converts to more stable form of nitrate. Nitrite level of Madura seawater was 0.0047 mg/L, while that of marketed product was 0.004 mg/L. which are in the range of allowable drinking water quality standard. In natural water bodies, nitrite levels are generally low due to the presence of oxygen, which stabilizes its properties. Nitrite is toxic because it prevents oxygen from being transported when bound to hemoglobin in the blood, making it an important parameter in determining seawater quality. Several factors influencing nitrite levels in water are including temperature, lighting, microbial activity, and the biochemical balance present in the aquatic ecosystem [

28].

Based on cyanide level testing, both samples comply with the permissible drinking water quality standard of less than 0.02 mg/L. Cyanide is a highly toxic non-metal compound that can significantly impact the health of marine organisms. Sources of cyanide include industrial waste and illegal fishing practices that use cyanide, both of which can severely damage marine life and even cause death. Factors influencing cyanide levels in aquatic environments include human activities involving cyanide (i.e., industrial discharges) and environmental factors (e.g., pH and temperature) that affect cyanide solubility. Cyanide exposure can lead to fatal poisoning, with risks of transmission through the consumption of seafood from contaminated marine organisms.[

19,

29].

Madura seawater concentrate sample showed a sulfide concentration of 0.011 mg/L, while the marketed seawater product exhibited a lower concentration (<0.005 mg/L). Hydrogen sulfide is a natural gas produced by the decomposition of organic materials containing metals by anaerobic bacteria. Hydrogen sulfide levels in aquatic environments increase when organic matter content is higher thus decrease the dissolved oxygen levels [

30]. Madura seawater revealed higher level of sulfide which mean that the surrounding area of sample contained more organic living materials than that of marketed seawater area. Nevertheless, both samples had sulfide levels within the permissible limits for drinking water as specified by WHO, which is less than 0.05 mg/L. Levels of hydrogen sulfide exceeding 0.05 mg/L can be identified by a distinctive odor and taste, similar to that of rotten eggs.

Hydrocarbon pollution in aquatic environments can arise from offshore oil production and transportation, waste disposal, oil spills, and biomass burning. While certain hydrocarbons can be biogenically produced by bacteria or through the natural chemical degradation of lipids, petrogenic sources often serve as the primary contributors to hydrocarbon pollution in coastal regions [

31]. Total hydrocarbon level test measured by using gas chromatography method showed that the Madura seawater sample exhibited total hydrocarbon levels as much as than 0.79 mg/L, which is within the permissible limits for surface water as set by the WHO, which is 10 mg/L. It can be concluded that seashore area of Madura can provide the deep seawater with good quality from point of view hydrocarbon pollution.

Total phenol compound testing using the continuous flow analyzer (CFA) method on sampel of Madura seawater concentrate found that total phenol concentration was 0.0016 mg/L. This level was in the range of permissible drinking water quality standard which must be less than 0.002 mg/L. The general toxicity threshold for phenol ranges from 9 to 25 mg/L for both humans and aquatic life. Phenolic compounds are organic substances that can be widely distributed in natural aquatic environments. These compounds tend to persist in the environment for extended periods and exhibit toxic effects. The presence of phenolic compounds in water can be as result from several factors including : natural sources where phenolic compounds were formed through biochemical processes in marine environments, as well as human activities that contribute to waste disposal and oil pollution [

32].

Surfactant (detergent) level of both samples exhibited values over the water quality standard (0.02 mg/L). The seawater concentrate sample from Madura showed a surfactant level of 1.8 mg/L, while that from the market product displayed a higher level (2.9 mg/L). Detergents, comprised mainly of synthetic organic chemicals known as surfactants, possess cleansing properties and are generally considered xenobiotic, featuring polar head groups and non-polar tails. The presence of detergents in water can lead to eutrophication, foam production, toxic effects on aquatic fauna, and a decline in water quality. Moreover, detergents can induce poisoning and irritation of the eyes and skin in humans [

33]. The elevated surfactant levels are likely attributable to factors such as waste discharge from human activities near the seawater sampling site.

The presence of oil and fat in natural water will interfere with biological life in surface and create unsightly film. It will spread over the surface in a thin layer and block the oxygen which needed by plants and animals living in the water. Film layer formation impedes gas diffusion and photosynthesis, resulting in unpleasant odors and hazardous gases, while oil emulsions can obstruct the respiratory systems of aquatic biota and organisms on the sea body [

34]. The quality standard of oil and fat level in drinking water is less than 0.2 mg/L. The seawater concentrate from Madura demonstrated an oil and fat level of < 0.11 mg/L, thus it is in the range of requirement level.

- c.

Biological Parameters

Biological parameter testing is essential to evaluate the quality of water focusing on two key parameters: fecal coliform and total coliform (

Table 3). Upon conducting fecal coliform testing, it was found that both samples failed to meet the drinking water quality standard (0 per 100 ml of sample) accoring to Indonesia’s Minister of Health Regulation No. 492/2019 regarding Drinking Water Quality Requirements. Both the seawater concentrate sample from Madura and the marketed product exhibited fecal coliform bacterial counts of < 10 CFU. The World Health Organization (WHO) established the risk of disease from drinking water based on the category of indicator organisms measured in 100 ml of water sample. In this context, the presence of 1–10 fecal coliforms indicates as low risk [

35]. The seawater concentrate sample from Madura, is a natural material that has not undergone microbial reduction or elimination process. Thus, it is imperative to incorporate microbial reduction or elimination during manufacturing processes. This can be achieved by adding antimicrobial agents or conducting sterilization procedures on raw materials of the seawater concentrate to ensure that the fecal coliform quality parameter aligns with permissible drinking water standards.

Total coliform count of both samples exhibited values that fail to meet the drinking water quality standard (0 per 100 ml of the sample) according to Indonesia’s Minister of Health Regulation No. 492/2019 concerning Drinking Water Quality Requirements. Total coliforms encompass organisms capable of thriving and reproducing in water, comprising various types of gram-negative aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacilli that do not produce spores. They can originated from fecal matter or surrounding water body. While total coliforms generally do not induce illnesses, their presence signifies bacterial proliferation [

36]. The detection of total coliforms underscores the necessity for sterilization procedures or the introduction of antimicrobials to the seawater concentrate of Madura, to ensure compliance with the drinking water quality standard. Other alternative is to find deeper spot of water collection to which fecal matter from daily life waste will not pollute the waterbody.

The deep seawater mineral concentrate currently lacks of standard or quality guideline. Hence, when quality parameters of drinking water outlined by the National Standardization Agency (SNI) has been employed, several parameters fall short due to the influence of the evaporation process during seawater concentrate production. These parameters include color, the Pt/Co scale value, distinctive odor, salinity, dissolved oxygen, BOD, pH, total phenol, surfactants, fecal coliform as well as total coliform.

Quantitative Chemical Analysis of Deep Seawater Concentrate

The analysis of deep seawater concentrates were conducted using XRF (X-Ray Fluorescence) and ICP-OES (Inductively Coupled Plasma–Optical Emission Spectrometry) methods due to their capability of simultaneous multi-element detection, detection speed, and high sensitivity and wide detection range [

37,

38,

39]. The results from these two instruments were compared to study the ease and sensitivity to be used in mineral content analysis. The results indicated that the seawater concentrate either from Madura or as marketed products contained the major component of Magnesium (Mg), Chloride (Cl), Potassium (K), Calcium (Ca), Sodium (Na), and Boron (B) (

Table 4).

The difference between mineral content detected from marketed products compared with deep seawater from Madura when analized by using XRF and ICP-OES either in qualtitative or quantities of the elements was contributed to the variation in sample treatment between XRF and ICP-OES analysis. In XRF method, the samples do not need to undergo destruction due to its capability to analyze both solid and liquid samples without prior destruction or dissolution. However, this can result in a higher matrix effect, which potentially affecting the results [

37]. Seawater concentrate, which was formerly processed into a concentrated form, can precipitate salts during storage [

40]. ICP-OES analysis cannot be conducted directly into solid samples. The sample must be dissolved, requiring the digestion of solids with acid [

5]. Mostly, aqua regia—consisting of HNO3 and HCl in a 1:3 ratio—has been used for this purpose. Acid digestion can alter the form of elements which some of them are not easily soluble or ionized. It can break down the complex compounds or minerals, releasing the elements [

5]. The differences in sample treatment and the matrix composition of the sample of XRF and ICP-OES analyses can affect the results potentially leading to discrepancies between the outcomes. XRF can detect greater number of elements than ICP-OES. However, in terms of trace elements, ICP-OES demonstrates the ability to detect elements at lower concentrations, ranging from 0.0365 to 18625.8 mg/L, whereas XRF operates within a higher detection range, from 6.61 to 188319 mg/L. In contrast, for detection of broader range of elements with higher concentrations, the XRF method is more suitable.

Based on the data, the Madura seawater concentrate contained mineral which are essential for supplement including major content of magnesium (Mg), chloride (Cl), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), copper (Cu), and sodium (Na) in the amount which meet the requirements for mineral daily intake as multivitamin supplement. Furthermore, heavy metals such as mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) were not detected from Madura seawater concentrate, indicating its safety in terms of raw materials for multivitamin supplement.

Formulation and Stability Study of Deep Seawater Granules using Different Types of Fillers

Seawater concentrate is concentrated liquid of deep seawater rich in minerals needed for supplement/multivitamin. In terms of stability, raw materials of pharmaceutical dosage forms will be better in solid form either as powders or granules because not only of being stable, but it also provide other advantages, namely ease in practical use, handling and distribution. The deepsea water as raw materials for multivitamins, most of which are minerals, had been changed from a liquid to solid in the form of granules. The method of drying and stabilizing the granules during time of storage became the biggest challenge. Previous research has proven that high mineral content will make solid preparations to be hygroscopic. To overcome this problem, it is necessary to select the optimum diluent and dessicant/drying agent. Lactose has been used as filler for the reason of affordable price to reduce production unit costs while microcrystalline cellulose was expected to provide better drying capability. The study on multifactor influencing granule’s stability had been elaborated to provide comprehensive data on developing granule of deep seawater as raw material for multivitamin.

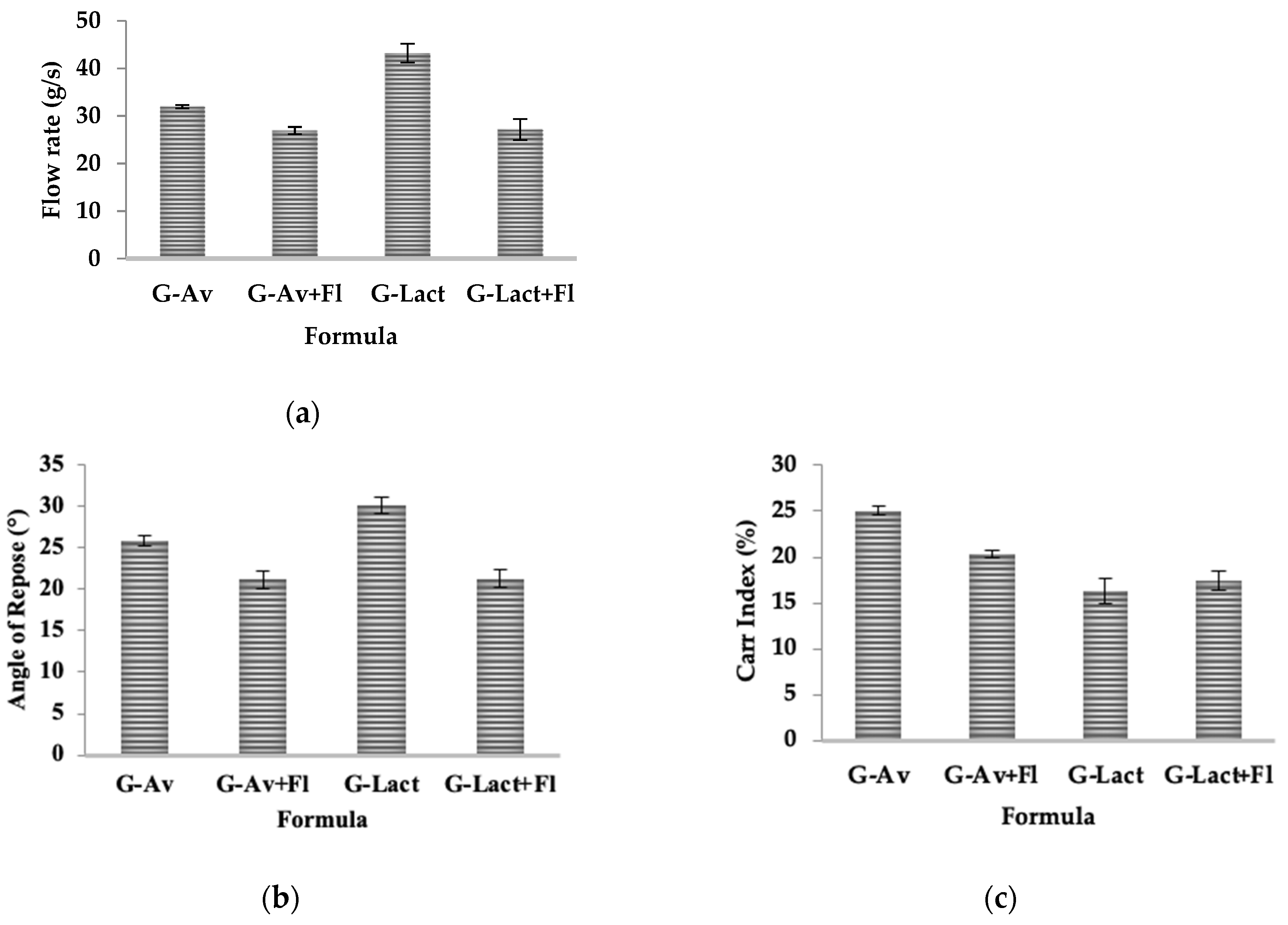

Upon formulation, evaluation on the flow rate of all granules exhibited good flow properties (exceeding 10 g/s flow rates,

Figure 1 a). Among others formulation, Lactose granules (G-Lact) revealed highest flowability which due to bigger particle size compared that with Microcrystalline Cellulose (Avicel PH 102). The result was inline with the previous finding that big particle size exhibit better flowability [

41].

In contrast, Angle of Repose determination exhibited better flowability of Avicel granules compared with those using Lactose as filler (

Figure 1.b). The small values of Angle of repose from Lactose granules were attributed to the hygroscopic nature of the material, which causes the granules to absorb moisture from the air and stick together in the funnel [

42,

43]. Flowability were increase as measured by smaller values of Angles to less than 25 after addition of Florite as dying agent. The findings supported previous study which found that moisture contents coats the particles to enhance the sticking ability thus increase particle interaction and large angle of repose.

Based on the compressibility/Carr’s index results shown in

Figure 1c, all formulations exhibited good compressibility values ranging from 5 to 20%, except for G-Av (25.71%). Compressibility refers to the ability of a material to reduce in volume under certain pressure [

44]. Formula G-Av had smaller granule sizes compared to others. Granule size affects the compressibility; smaller granules tend to have higher compressibility percentages, while larger one will exhibit lower percentages [

45].

The production of granules requires consideration of stability and ease in distribution. To enhance the stability, desiccant is essentially needed to counteract the hygroscopic nature of the mineral content in granules. In this experiment, Florite® was employed as the desiccant at concentration of 10%. It is a synthetic calcium silicate with outstanding liquid absorption capability up to approximately five times its weight. It is also reported to have compressibility improvement properties [

46].

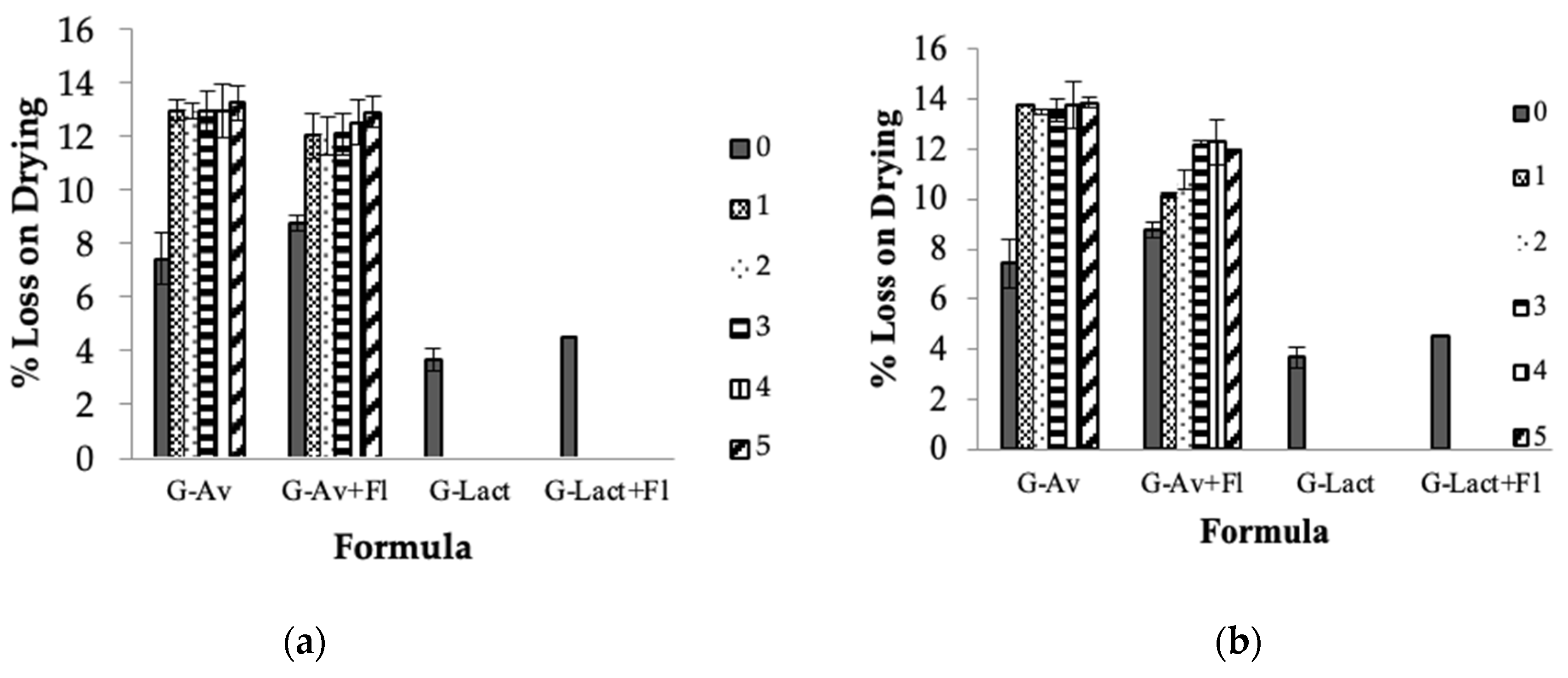

Stability of formula G-Av, G-Av+Fl, and G-Lact+Fl granules at room temperature remained stable, while formula G-Lact melted at the third days of storage. Granules using Avicel® as a filler (G-Av and G-Av+Fl) demonstrated good stability until five months of storage either at room temperature (

Figure 2a) or during stress stability at climatic chamber (

Figure 2b). As addition to serve as filler, Avicel® also provided the adsorbent capability thus reducing hygroscopic properties [

47,

48].

Accordingly, the granule formula using lactose as fillers G-Lact and G-Lact+Fl (lactose filler and Florite as a dessicant) in the first month had been melted thus cannot continue the stability testing (

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b). At early stage of in process evaluation, G-Lact granules had been obtained and was more hygroscopic compared to G-Lact+Fl granules, meaning that Florite affected the hygroscopic properties of the resulting granules. Nevertheless, these granules could not survive and liquified at two weeks of storage. It can be concluded that the type of filler had more dominant influence on the formulation than the desiccant.

The results indicated that Avicel® as model of Mycrocrystalline cellulose derivate can effectively maintain the stability and quality of the higroscopic granules with high mineral content of seawater concentrate. Thus the moisture protection of deepsea water in form of solid material (granule) have been successfully developed

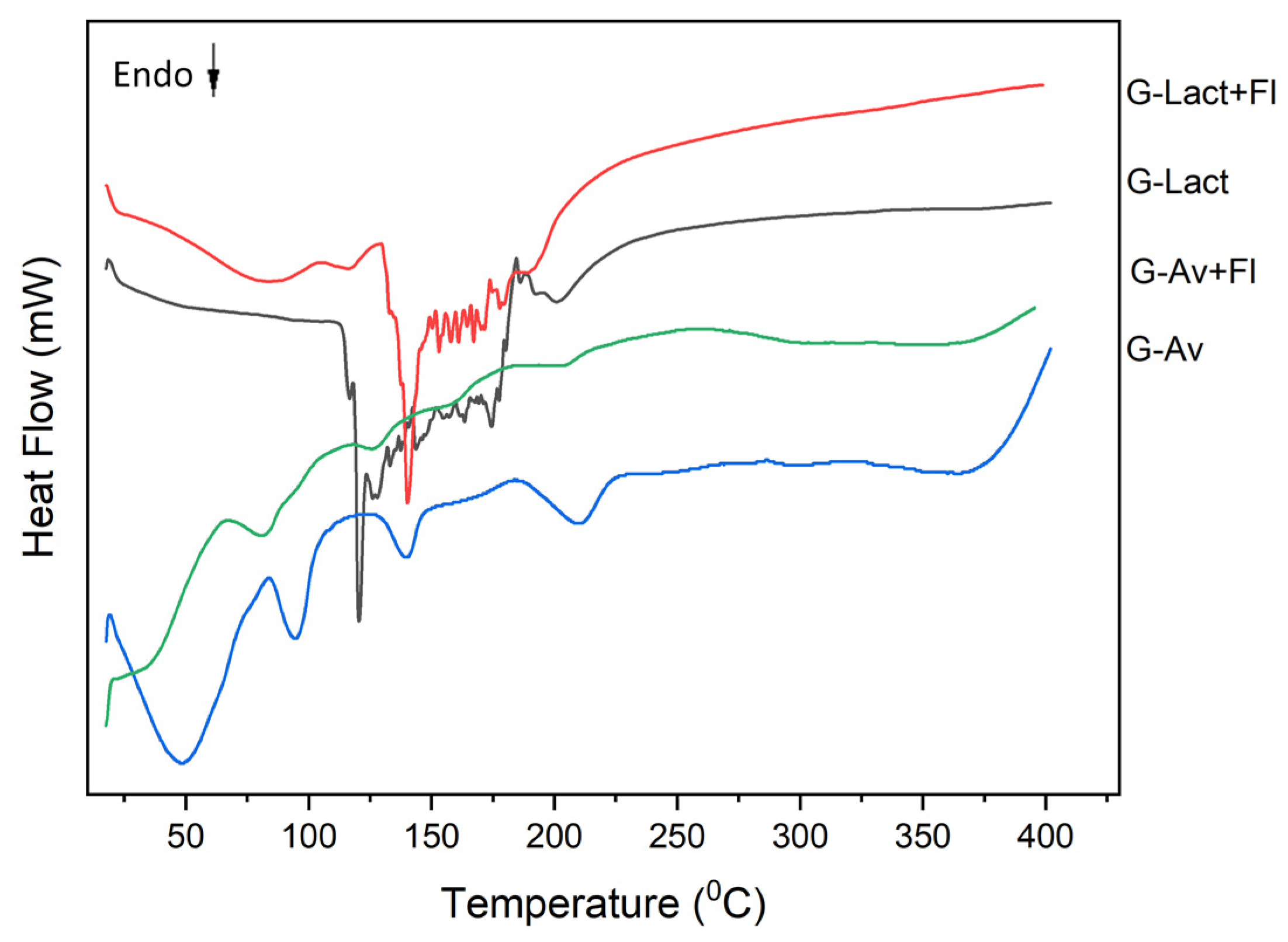

Thermal Behavior Analysis of Granules by DSC Testing

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) testing aims to observe the melting point shift and the transition point of the sample. DSC can also be used as a parameter for stability testing [

49]. The thermal analysis of deep seawater granule formulations—including Avicel® granules (G-Av), Avicel® granules with Florite® 10% (G-Av+Fl), lactose granules (G-Lact), and lactose granules with Florite® 10% (G-Lact+Fl)—were conducted by using DSC (

Figure 3). The results in

Figure 3 showed that addition of drying agent (Florite®) had improve the melting point of the granule to become higher. Notably, there are differences in the melting peaks between granule with Lactose and those with Avicel as filler. This shift in melting point correlated with enhanced stability of the granules containing Florite® 10% showing greater thermal stability. Similarly, differences in thermal transition points were observed in lactose granules (G-Lact) and lactose granules with Florite® (G-Lact+Fl), indicating that the addition of Florite® positively impacted the stability of the granules. Melting point of Florite is 1.540

oC; Lactose is 201-202

oC

, and Avicel® is 260 -270

oC [

50,

51].

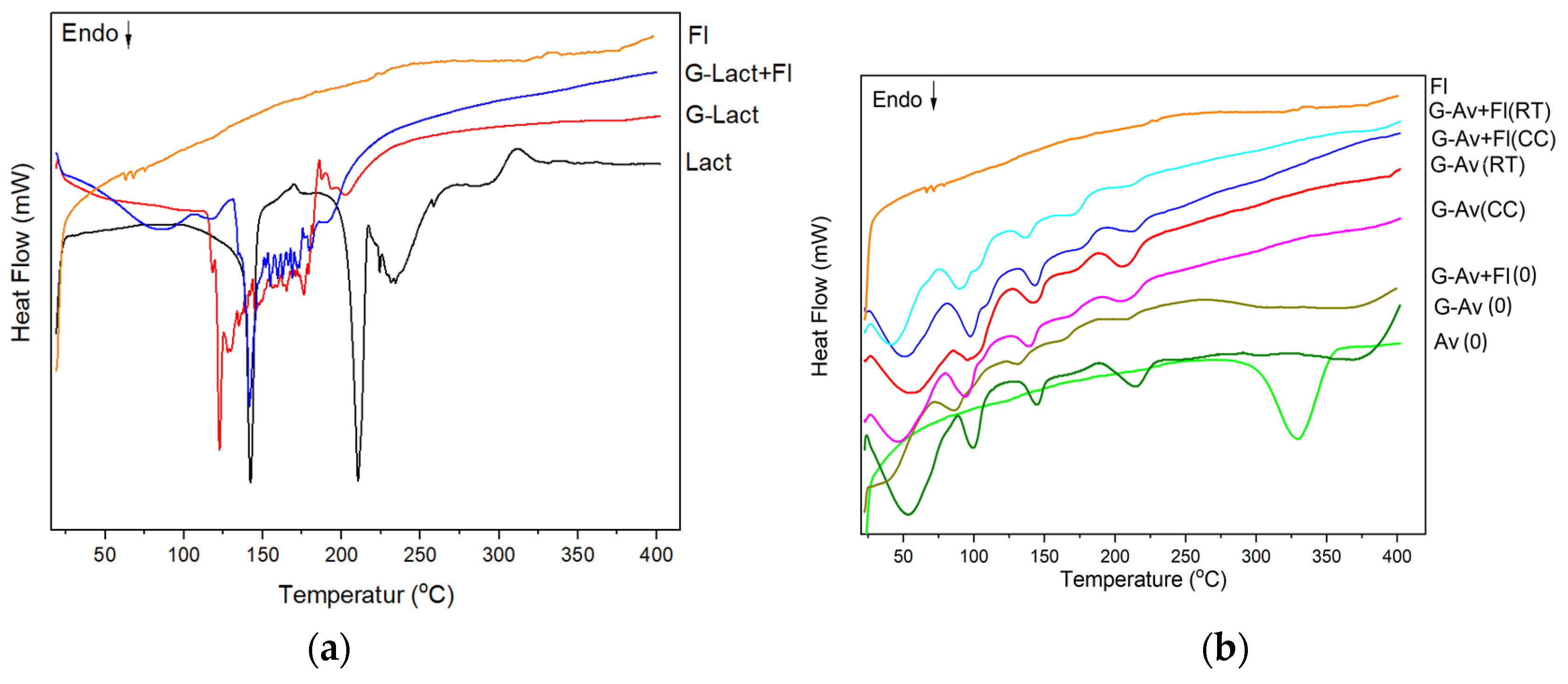

The distinct differences in the thermal behavior of the two formulations (

Figure 4a and

Figure 4b) was due to different physical properties of Lactose (crystalline) and Avicel/Microcryastalline Cellulose (semicrystalline). This hypothesis will be discussed XRD analysis section. During stability study, Avicel® granules (G-Av) and Avicel® granules with Florite® (G-Av+Fl) showed more robust formulation suggesting that the type of filler highly influenced the stability of the granules. Granules with lactose as filler could not stand the stability testing and begun to melt on the second week of storage, thus further observation on stability testing could not be continued (

Figure 4a). Hygroscopic properties of lactose granules was not only due to chemical property of lactose but also larger particle size and porosity of the granule. The granules using Avicel PH 102 as filler were successfully revealed the good stability until five months of storage by showing similarly difractogram either in room temperature or climatic chamber. Slight shift of melting points were found when comparing formulation using Florite as drying agent with that without it.

XRD Analysis

The purpose of using XRD analysis is to identify crystalline phases within the material [

52,

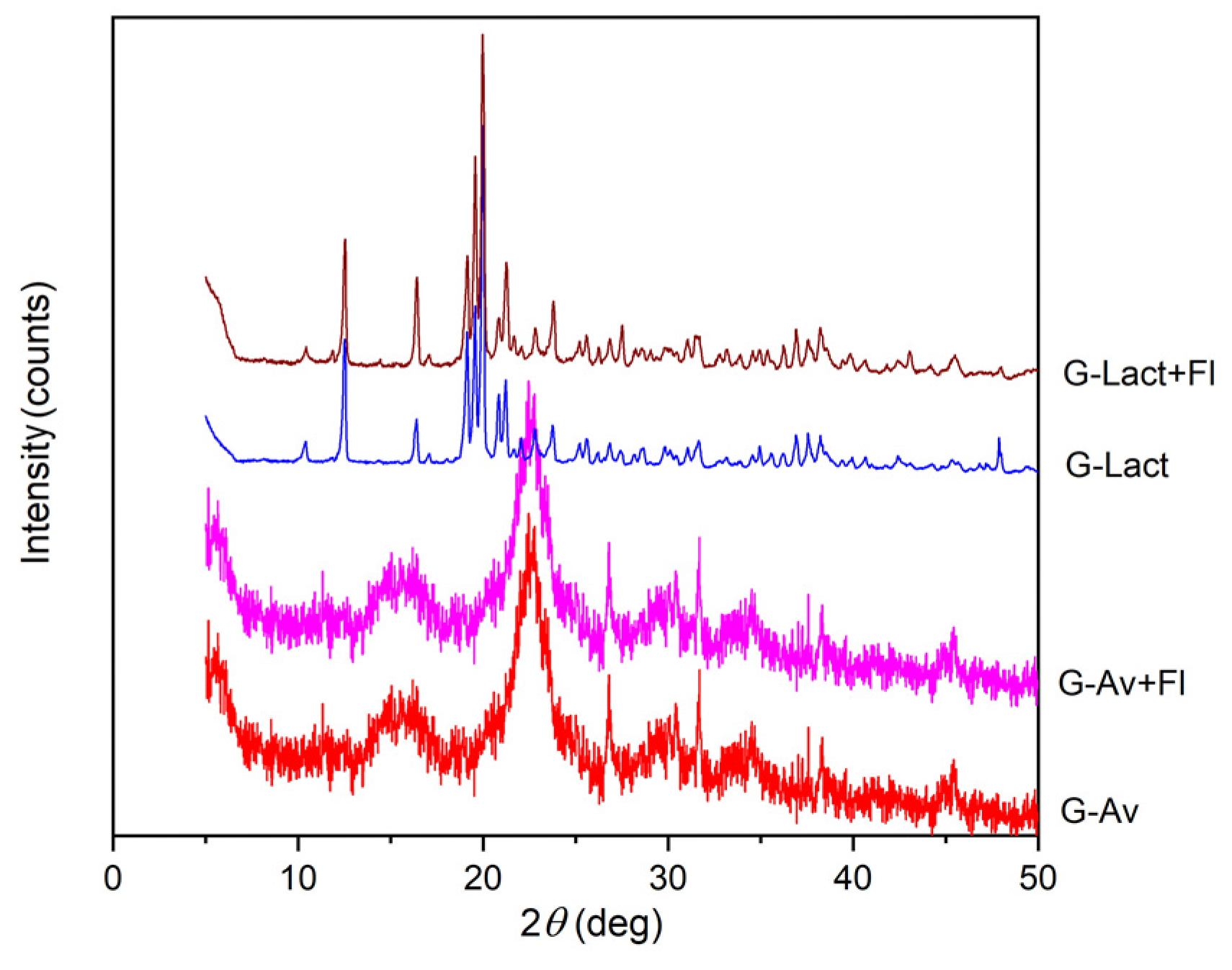

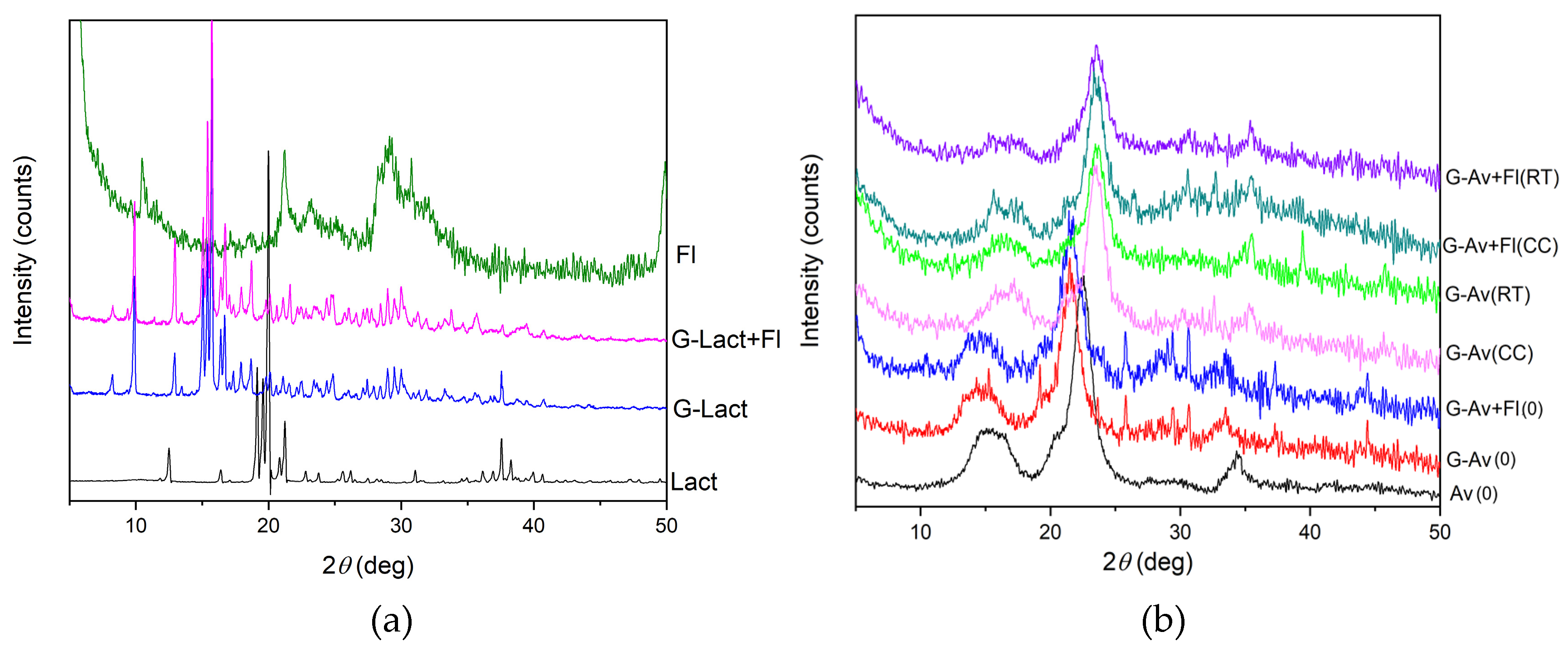

53]. Based on the x-ray diffraction patterns of the mineral granules with various fillers and Florite® as drying agent, it was evident that the peak intensities were apparently differ among the samples. Lactose granules and lactose granules with Florite® 10% exhibited sharp and high diffraction peaks due to crystalline property of lactose as filler. In contrast, Avicel® granules and Avicel® granules with Florite® 10% addition, as well as Avicel® powder displayed less pronounced crystalline patterns (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6b). The diffraction pattern of Avicel® was characterized by its microcrystalline structure, resulting in broad peaks due to its low crystallinity [

54]. Notably, the addition of Florite® 10% to the mineral granules did not alter the crystalline form of the filler as exhibited by lactose (

Figure 6a). Thus, the granules failed in stability study which were performed for five months of storage. The results were inline with previous data on LoD and DSC thermogram (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4). In conclusion, the formulation of moisture resistant granules containing deep seawater which physically stabile were succesfully developed by using Avicel PH 102 as filler either by addition or not of dessicant/drying agent.

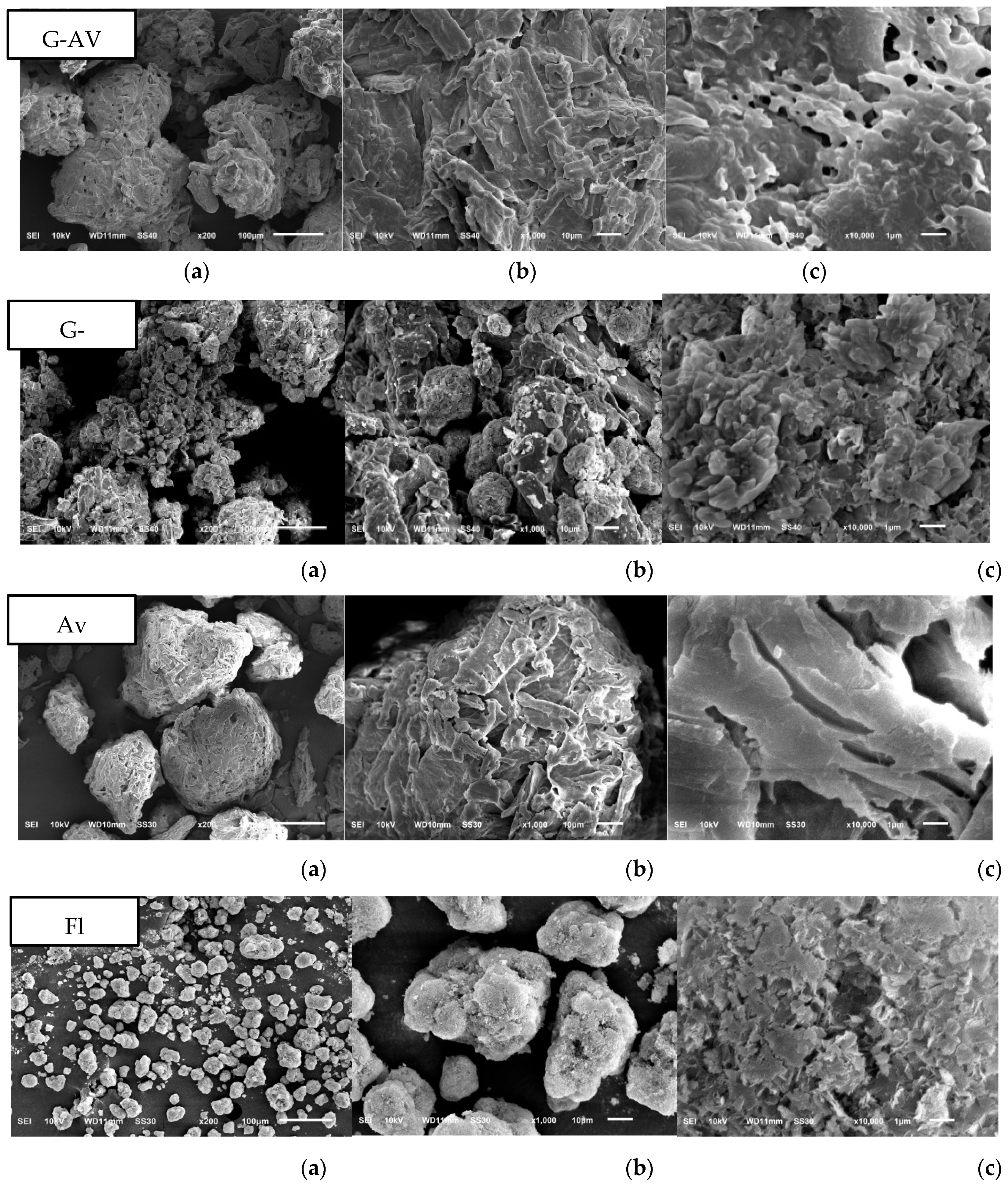

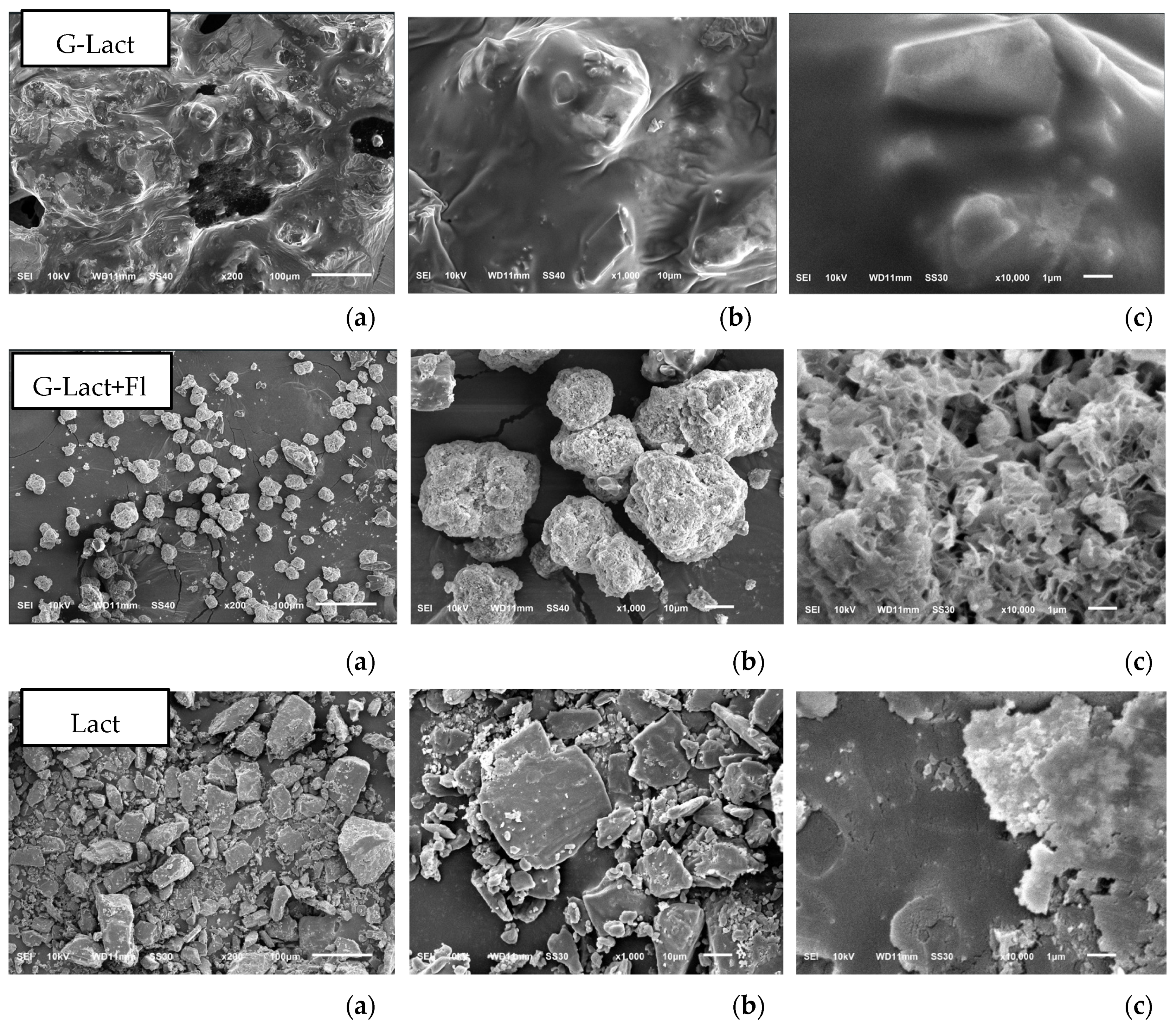

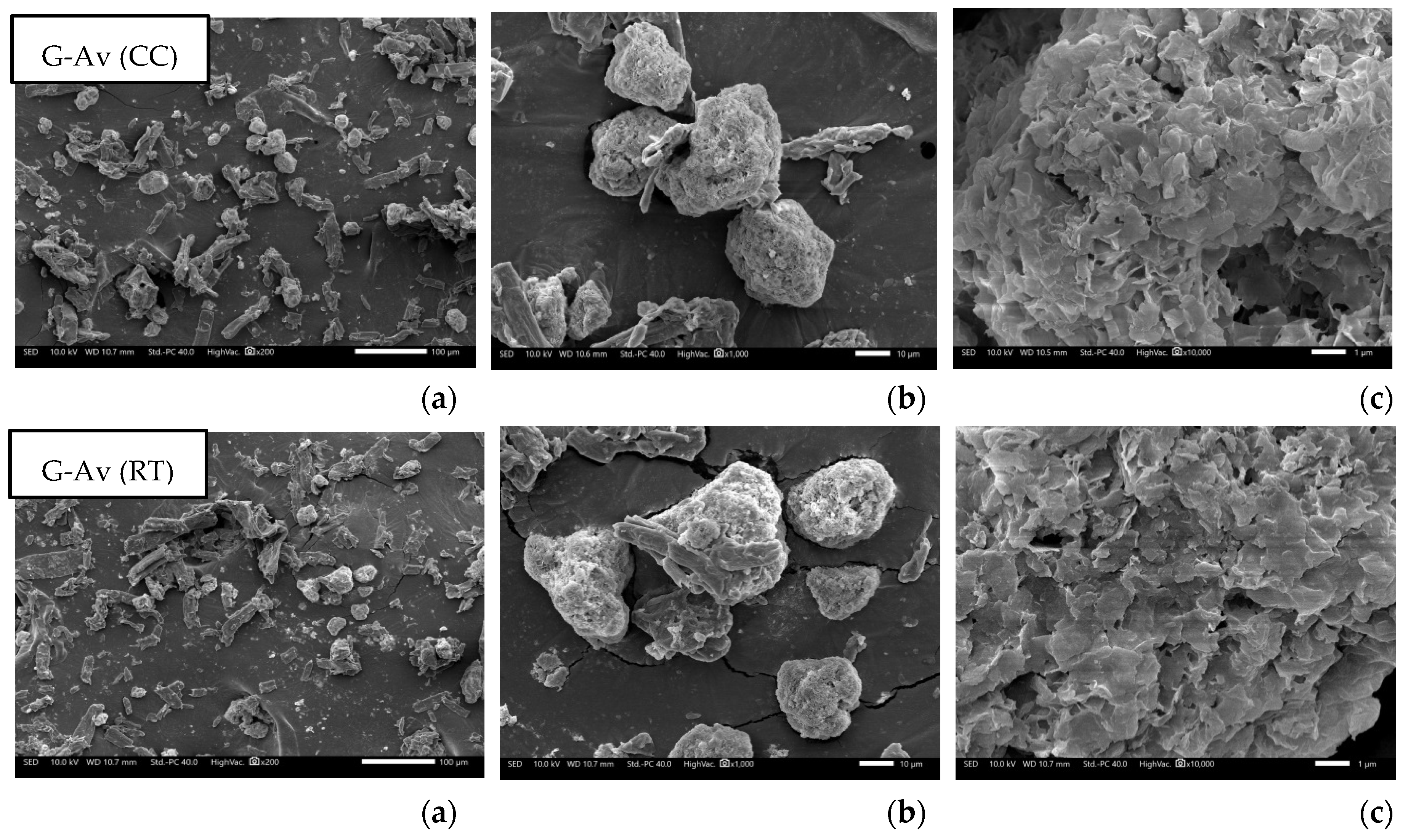

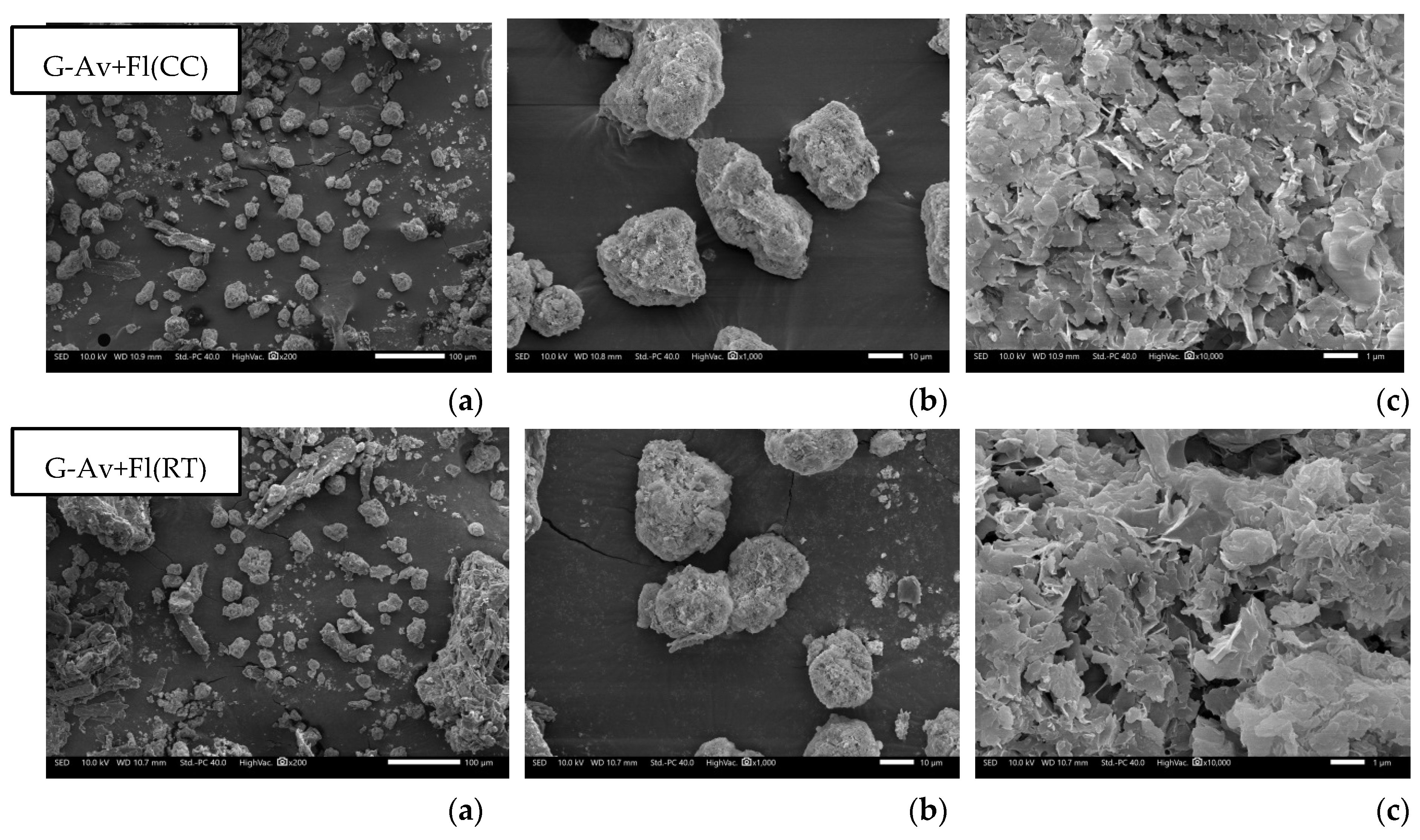

Study on Morphology and Surface Particles by Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

SEM analysis were conducted to characterize the morphology and structure of the deep seawater granules. SEM also aids in determining the structure and homogeneity of particles [

55]. Based on the morphological observations of granules with Avicel® as filler, and Avicel® granules with Florite® 10% addition, it was found that Avicel® granules with addition of Florite exhibited a more porous morphology compared to other formulations (

Figure 7) resulted in increased LoD (

Figure 2a) as well as higher melting points either in Avicel or Lactose filler formulations (

Figure 3).

The morphological analysis of granules with lactose as filler revealed that the granules with Florite® 10% addition were physically improved in morphology compared with that without drying agent. Lactose powder typically appear as heterogeneous flakes, whereas at day of formulation, the granules with lactose filler exhibited a dense, non-porous texture. Few hours after granulation, the stability problem arose and they inherently became hygroscopic (G-lact,

Figure 8), leading to melted particle. With Florite addition as drying agent, the granules were more stable, showing a porous particle morphology. In term of hygroscopicity, porous morphology tends to be more adsorptive due to its larger surface area to interact with surrounding molecules. Materials with porous morphology can absorb and retain moisture more efficiently [

56]. Nevertheless, adsoprtive property of drying agent at 10% concentration was not strong enough to stabilize higroscopic nature of Lactose, thus these formulations failed in stability study which was performed for five months of storage. Based on stability testing, the finding of this study was that deep seawater concentrate can be produced into granules by employing Avicel® as fillers (

Figure 9). The addition of Florite® 10% as drying agent was the most favorable outcomes due to more individualized particle after the study either at room temperature or climatic chamber (

Figure 9).