1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain the leading cause of death among women and men worldwide [

1]. In most clinical trials in cardiology, men dominate, and women are underrepresented. However, in the case of various forms of pulmonary hypertension (PH), the opposite is true: women predominate quantitatively among the participants in clinical trials [

2,

3,

4,

5]. This is due to the fact that women are more susceptible than men to several forms of PH [

6,

7].

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is a condition defined by elevated pressure in pulmonary vascular bed caused by partial occlusion of the pulmonary arteries due to organized persistent thrombi, often accompanied by remodeling of patent resistive pulmonary arterioles [

8]. Based on registry data, the prevalence of CTEPH is approximately 25.8-38.4 per million [

9,

10,

11]. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA) is a minimally invasive procedure that has become an effective treatment option for CTEPH patients who are ineligible for pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) or present with persistent PH after surgery [

8,

12,

13,

14].

Sex-specific differences in CTEPH have been studied, with some evidence suggesting that women may be at higher risk for developing CTEPH.[

15]. Some studies suggest that there may be differences in the clinical presentation, risk factors, and outcomes of CTEPH treated by PEA between males and females [

16]. However, there is limited research on the differences between women and men in CTEPH treated with BPA.

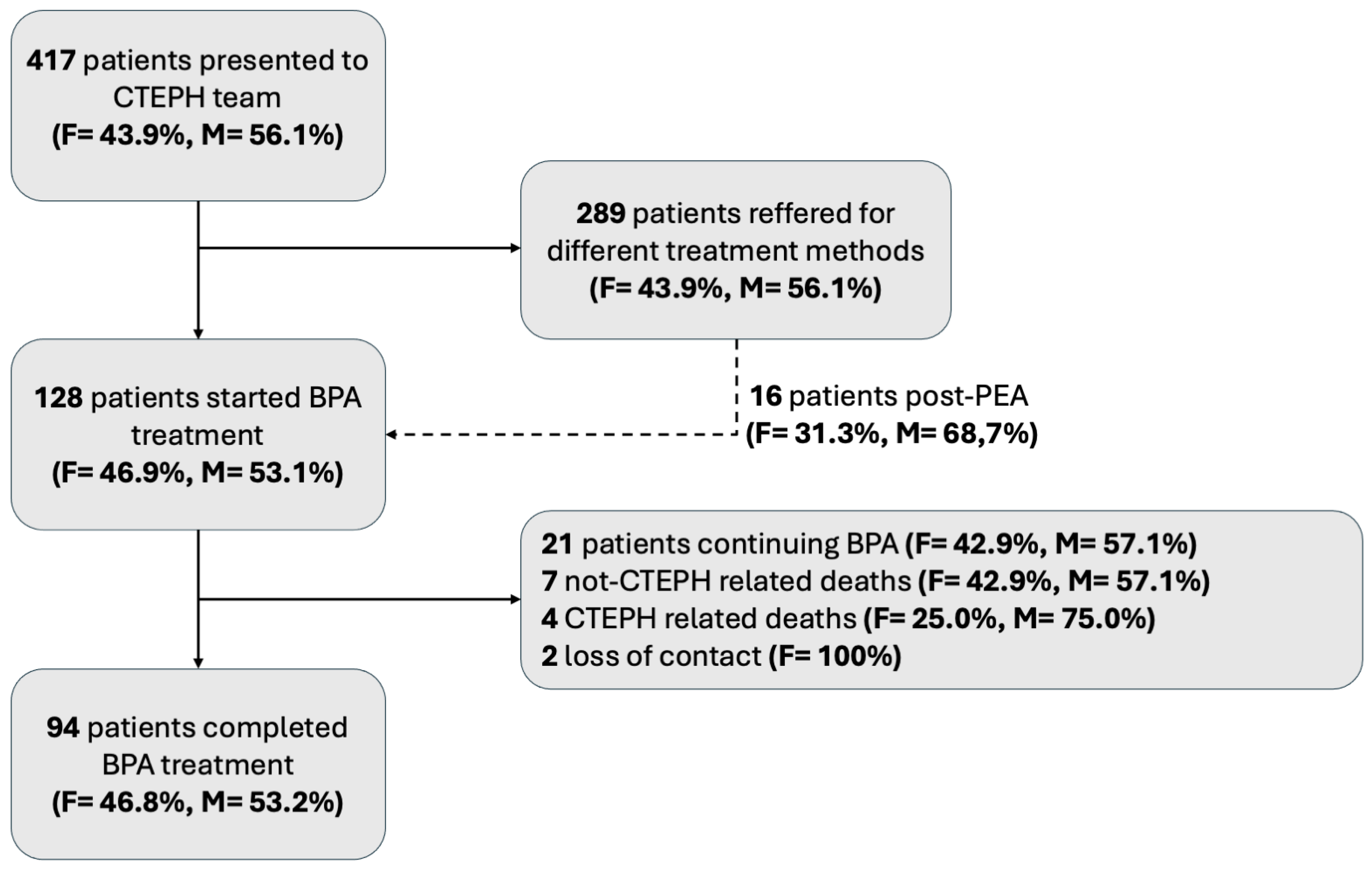

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate sex–specific differences in patients with CTEPH who were treated with BPA procedures.

4. Discussion

CTEPH is a rare condition, but it can lead to right heart failure, multiorgan disfunction, and death if left untreated. The BPA therapy which has been used relatively recently in the treatment of patients with CTEPH [

21,

22], has been upgraded in the recent guidelines for CTEPH treatment, which currently recommended BPA as a part of multimodal approach for patients who have inoperable lesions or have residual PH after PEA and distal obstructions amenable to BPA (class of recommendation IB). This procedure may also be applied to those patients who are operable but have a high proportion of distal disease and a PEA procedure may generate a high risk for them. BPA can also be considered in some symptomatic patients with CTEPD without PH [

8].

The recent study

which analyzed preoperative computed tomography pulmonary angiography of patients who underwent PEA for CTEPH identified sex-specific differences in the surgical cases [

23]. Men had more vessels involved than women (mean 20.3 vs 17.1,

p = 0.004) and had fewer disease-free pulmonary segments (mean 4.9, SD 4.3 vs 7.6, SD 5.5,

p = 0.001). In addition, men had a greater number of webs, eccentric thickening, and occlusions. The distribution of lesion type did not significantly differ between sexes at the main or lobar level, but men had significantly more lesions in the segmental vasculature while women had a higher proportion of subsegmental lesions (p < 0.001) despite no significant differences in baseline hemodynamics [

23]. Although, it was described that after PEA women benefit less in reduction of PVR (437 Dynes∙s∙cm−5 vs 324 Dynes∙s∙cm−5 in males, p < 0.01), the overall 10-years survival after surgical treatment was similar (73% in females vs 84% in males, p = 0.08) [

24]. In multivariate analysis female sex remained an independent factor affecting the need for targeted PH medical therapy after PEA (HR 2.03, 95%CI 1.03–3.98, p = 0.04), which suggests other mechanisms may be responsible for worse response to surgical treatment in females with proximal disease [

24].

There is a lack of data, whether sex affects BPA results. Therefore, we aimed at evaluation whether differences exist between men and women with CTEPH and to evaluate if outcomes of treatment with BPA differs regarding sex/gender. Women are known to be more susceptible to PH than men, and therefore usually among patients with CTEPH, but on the other hand women have also better survival [

16,

25,

26]. In the case of CTEPH, the latest publication based on European registry indicated an equal ratio of affected women and men [

16], similarly as US registry [

27]. Registry developed by International CTEPH Association reported general dominance of women (52.4%), however in Europe they made up slightly less than half (48.7%) of patients with CTEPH [

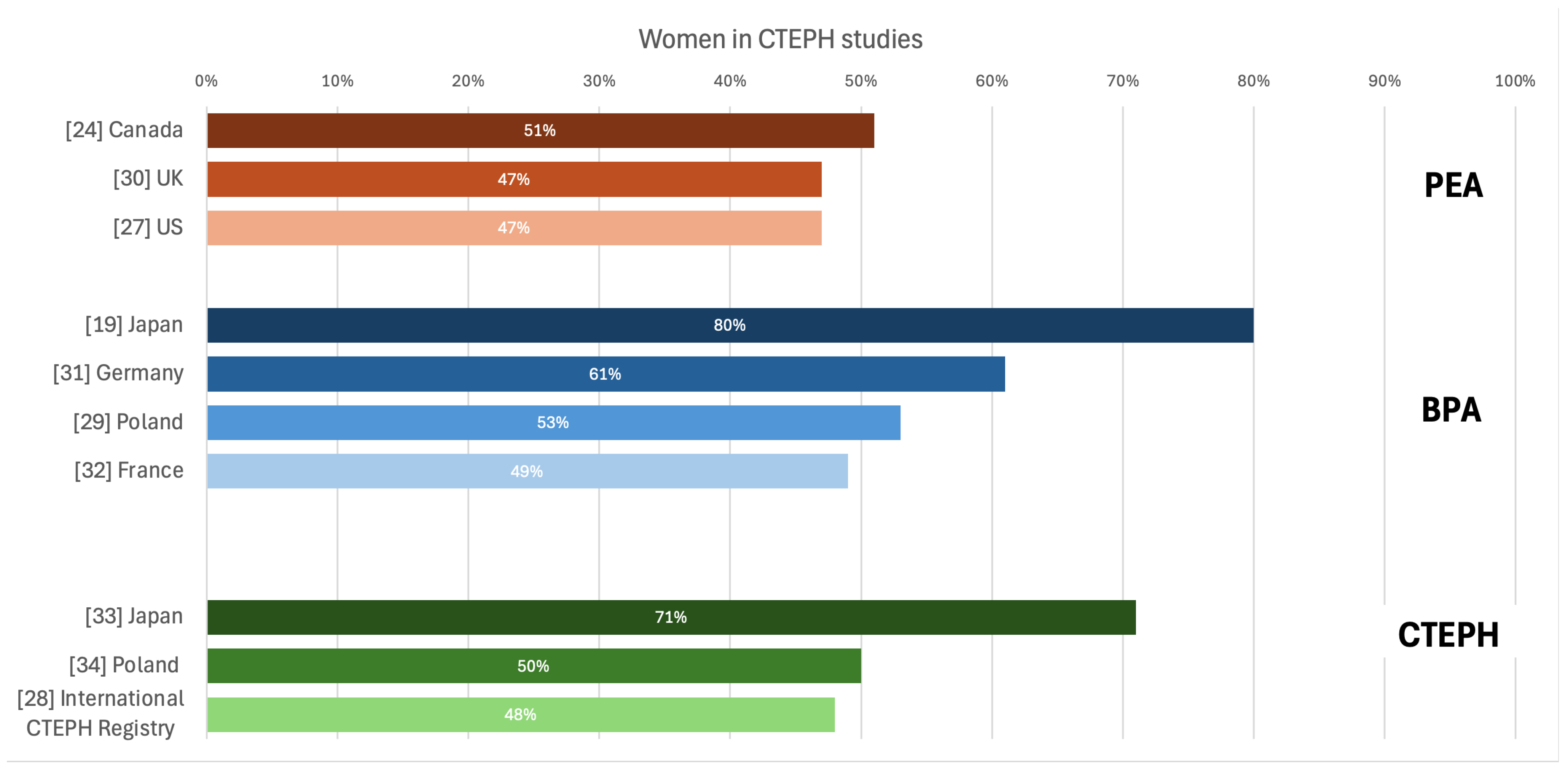

28]. (

Figure 5 [

14,

19,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]).

European registry indicated that women had lower prevalence of some CV risk factors than men, such as previous acute coronary syndrome, smoking and COPD, but more often were obese, and had cancer or thyroid diseases history [

16]. Women and men included in our study did not differ in terms of comorbidities, except for the occurrence of COPD that was much less frequently diagnosed in women.

As the CTEPH is strongly associated with the occurrence of pulmonary embolism and an incomplete thrombus resolution [

35], sex/gender differences related to coagulation should be also considered. Typical thrombogenic factors were not proved to increase in patients with CTEPH in contrast to plasma factor VIII [

36,

37]. This factor physiologically has higher values in women than in men [

38], what may predispose women to developing CTEPH. In the Japanese BPA Registry females represented 80% of included patients, and previous episodes of acute pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis were not frequent (15,3% and 43,7% respectively) [

19], as compared with reports from other Western countries (74.8% and 58.1%, respectively, in a European registry) [

39].

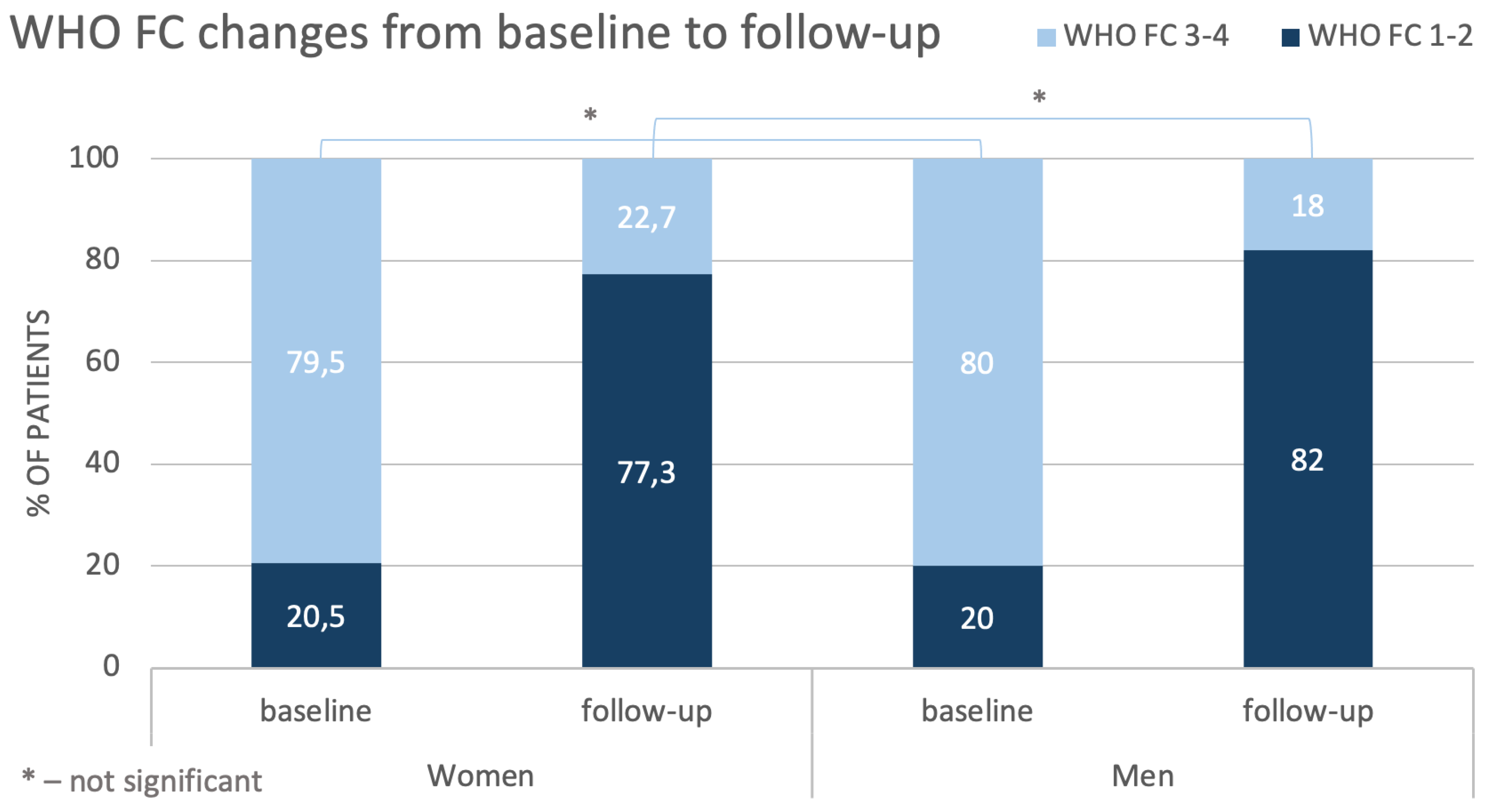

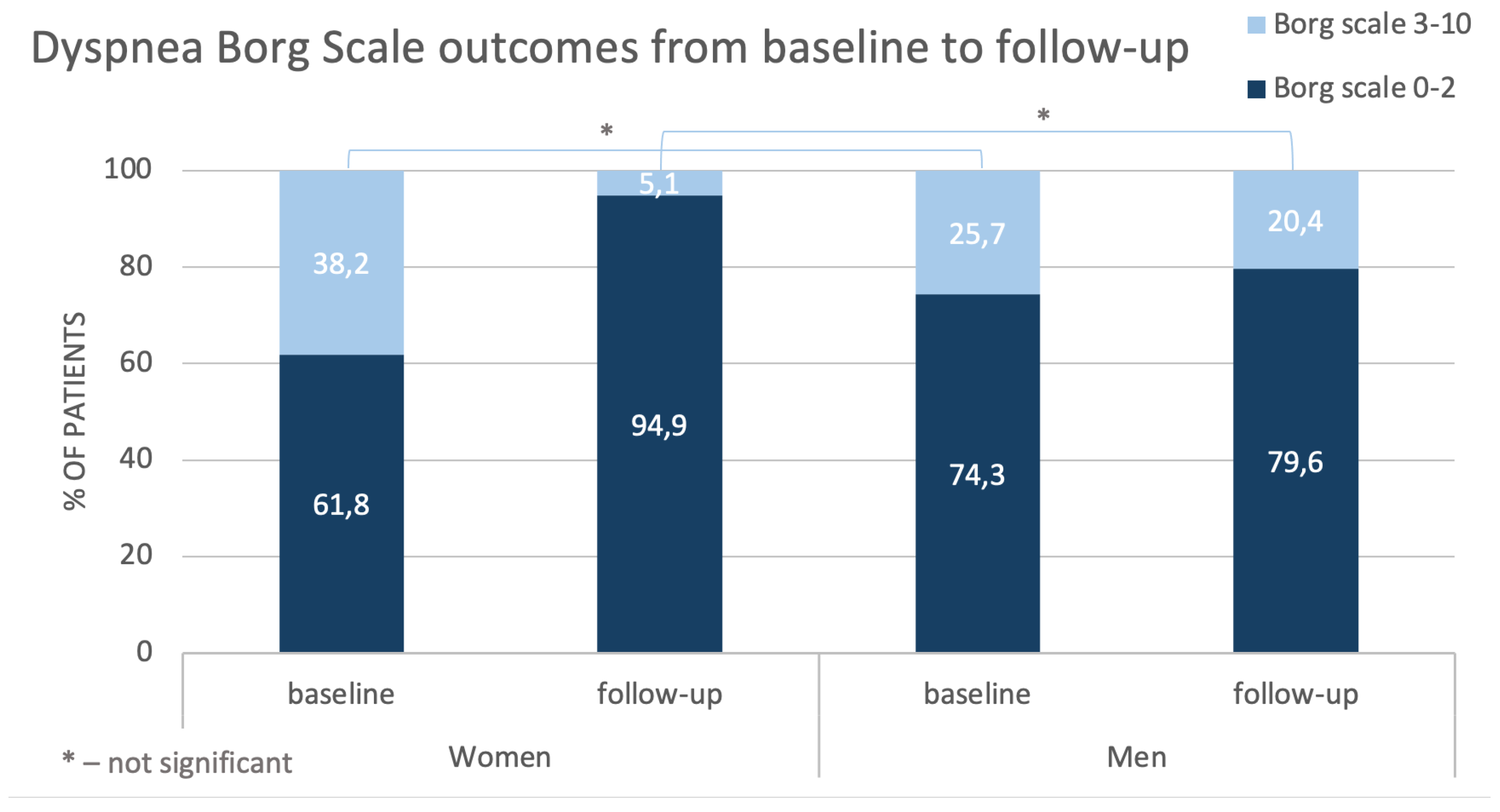

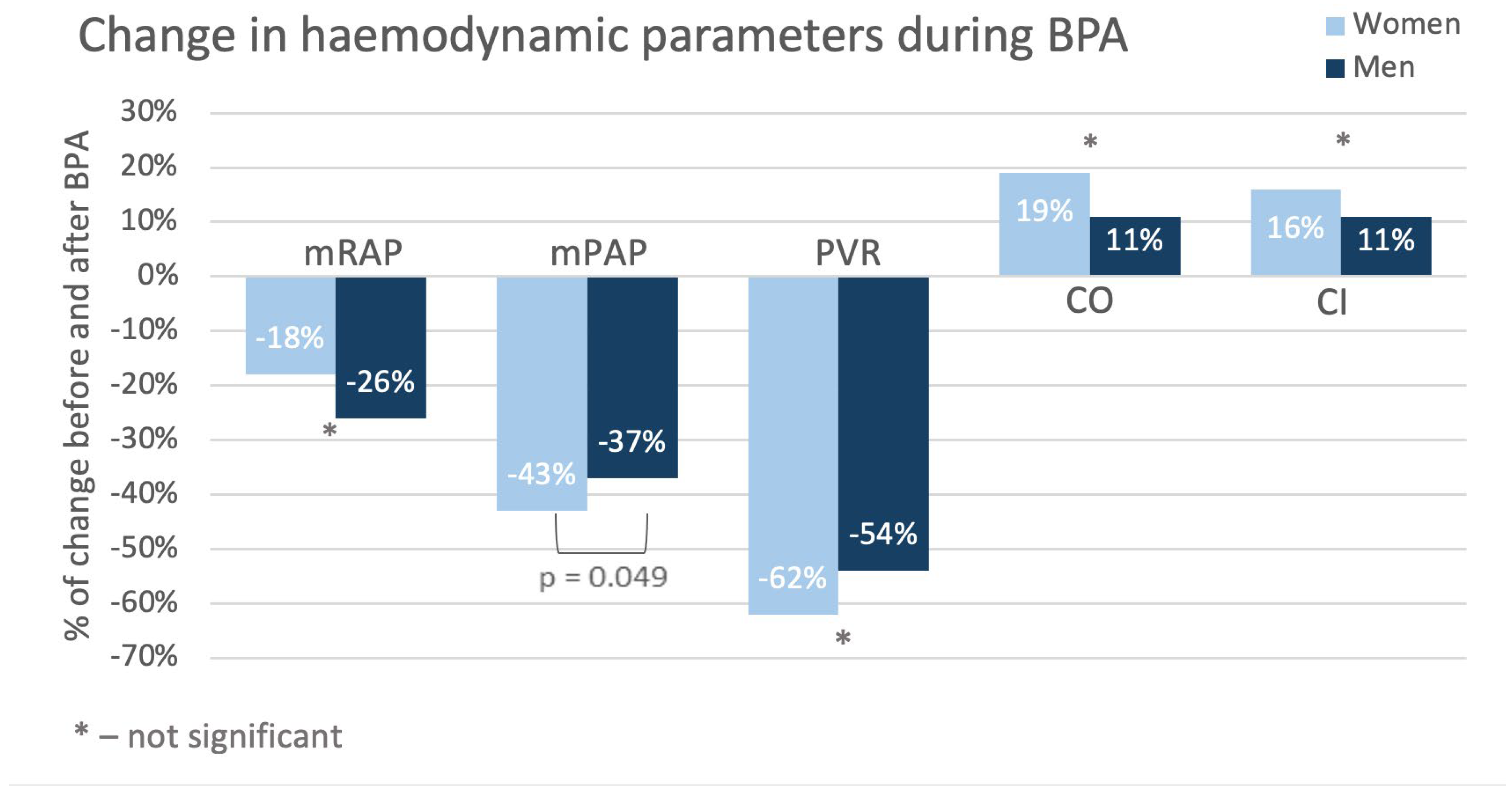

Assessing patients’ status at baseline, we found that woman tended to have worse hemodynamics values than men, as indicated by higher sPAP and PVR and by lower SV. Creatinine levels were slightly higher in men, but this may probably result from physiologically higher muscle mass in men. In turn, clinical presentation in women and men was quite similar – there were no significant differences between sex/gender in results of Dyspnea Borg Scale and also in the distance walked during 6-MWT. Our population also did not differ in terms of WHO FC and most patients were diagnosed with WHO FC class 3. This observation is consistent with results described in other studies [

26,

28,

40] and also with observations from European CTEPH registry [

16], indicating that women slightly more often have functional capacity class III/IV diagnosed than men. More severe courses of the disease in women than men with CTEPH was also reported by Wu et al. [

41].

More severe baseline hemodynamic parameters in women compared with men together with similar clinical symptomatology suggest that at diagnosis women are better adapted to the disease than men. On the other hand, it may be hypothesized that women will require more BPA sessions to achieve similar improvements in hemodynamics as men.

As there are no detailly defined therapeutic targets of BPA treatment in patients with CTEPH, usually achieving a good functional class (WHO-FC I–II) and/or improvement of hemodynamic parameters, as well as improvement in patients’ quality of life [

8]. However, some recent data from ESC Working Group Statement defined BPA treatment goal to achieve final mPAP < 30 mmHg [

42]. Comparing the effects of BPA from two multicenter registries (Japanese and Polish) and from single expert-centers (German and French) it was demonstrated that only Japanese were able to reach defined BPA treatment goal of mPAP below 30 mmHg [

43]. This may be due to the intrinsic differences between European and Japanese patients, with European CTEPH patients having higher serum concentrations of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and myeloperoxidase, and more red thrombus than Japanese CTEPH patients [

44]. However, high-volume women representation in Japanese registry may be also suggestive for gender-related outcome in BPA treatment.

Control tests performed in the studied population after completion of BPA treatment revealed better hemodynamic status (especially regarding mSAP, sPAP, PCWP and CI) in women than in men, although at baseline the situation was opposite. Detailed analysis demonstrated that after treatment many parameters changed more in women than in men with decreases in mPAP and PVR being the most pronounced. These were reflected particularly in outcomes of Dyspnea Borg Scale – compared with baseline at follow-up in about 30% of women ratings shifted towards point 0-2 and such improvement was observed only by about 5% of men. Results of 6-MWT this difference did not achieve statistical significance.

Our results are even more interesting considering that there were no differences in number of the sessions, number of the treated vessels or the required amount of contrast and radiation between men and women. This may suggest that women respond better to CTEPH treatment with BPA than men.

The above observation seems to stay in line with the previously reported better long-term survival in women compared with men. This phenomenon is suggested to be related to better function of right ventricular in females than in males [

45,

46]. Unfortunately, echocardiographic data were unavailable in our study, hence we were unable to assess right ventricular functions in our population. However, that hemodynamic differences exist between different types of CTEPH with a worse condition in central than in peripheral form of disease [

47]. Besides, in some studies, women tended to deteriorate more than males during follow-up [

48].

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

To our knowledge this is the first very detailed study analyzing the impact of patients’ sex/gender on results of BPA therapy in patients with CTEPH. As it was a retrospective (single center, small group) study, we were able to provide valuable data from real clinical practice. However, some assessments are missing which is an inherent limitation to this type of research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., A.T. and S.D.; methodology, S.D; validation, M.K. and M.F.; formal analysis, Paweł Kurzyna; investigation, Paweł Kurzyna and A.W; data curation, Paweł Kurzyna; writing—original draft preparation, A.W. and Paweł Kurzyna; writing—review and editing, M.K, A.T, S.D., Piotr Kędzierski, P.S., M.P., M.B., A.G-vdP and A.P.; visualization, Paweł Kurzyna, A. W.; supervision, M.K and S.D.; project administration, Paweł Kurzyna; S.D.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.