Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

25 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Assessment of Carotenoids

Assessment of Food Security Status

Ascertainment of Mortality

Covariates

Statistical Analysis

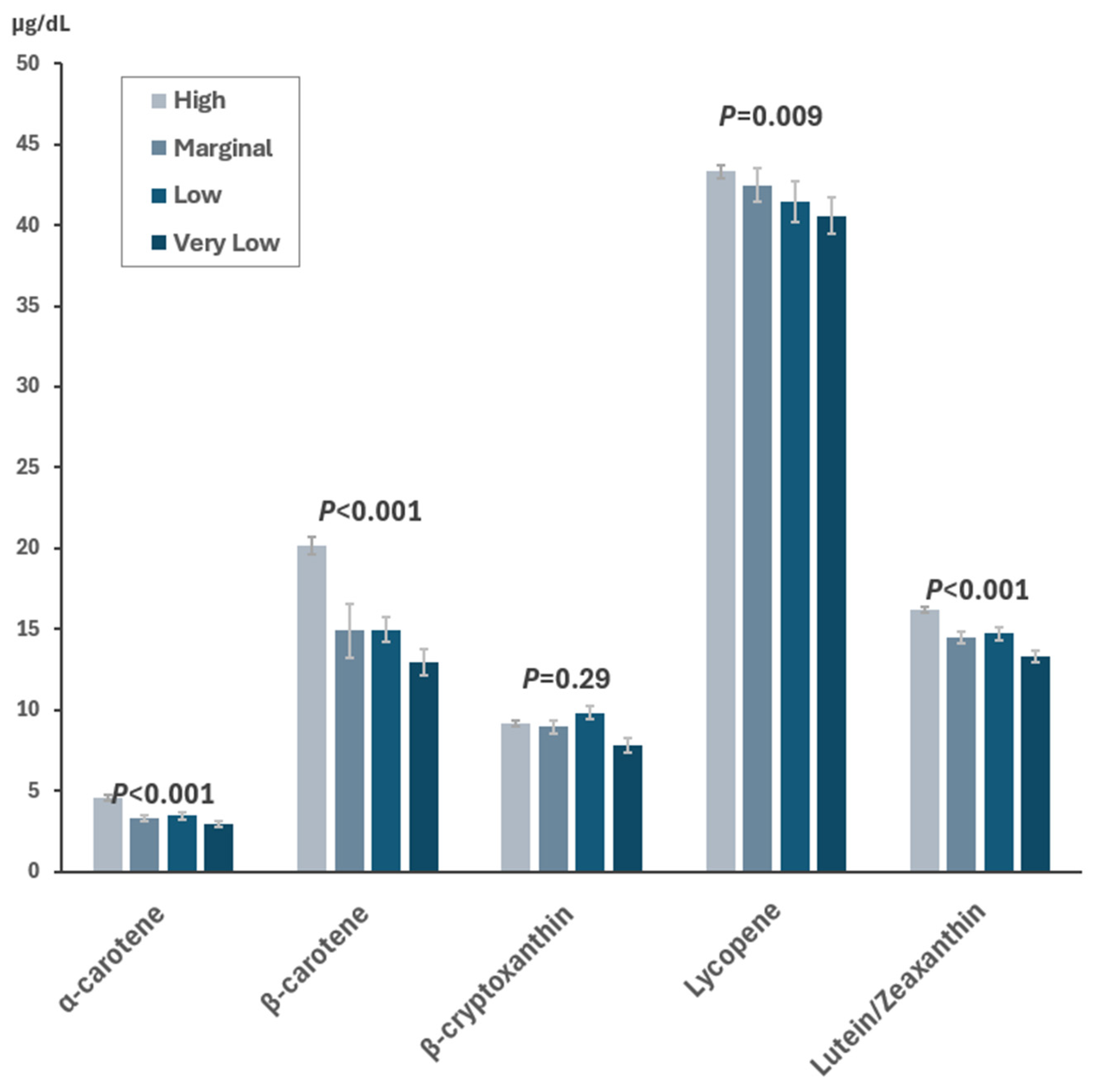

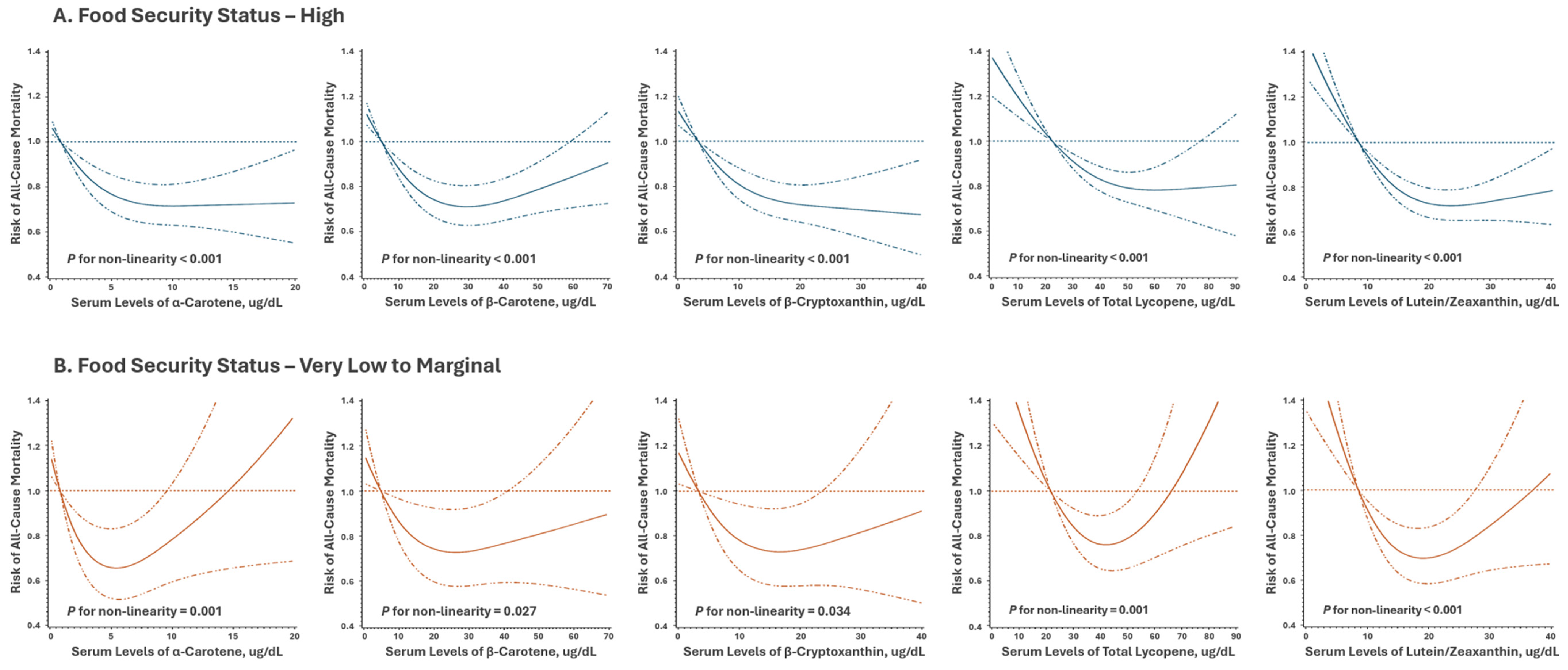

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

References

- Slavin JL, Lloyd B. Health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Adv Nutr Bethesda Md. 2012;3(4):506-516. [CrossRef]

- Wallace TC, Bailey RL, Blumberg JB, et al. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(13):2174-2211. [CrossRef]

- Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):1029-1056. [CrossRef]

- Fiedor J, Burda K. Potential role of carotenoids as antioxidants in human health and disease. Nutrients. 2014;6(2):466-488. [CrossRef]

- Landrum JT, ed. Carotenoids: Physical, Chemical, and Biological Functions and Properties. CRC Press; 2010.

- Huang J, Weinstein SJ, Yu K, Männistö S, Albanes D. Serum Beta Carotene and Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Circ Res. 2018;123(12):1339-1349. [CrossRef]

- Fujii R, Tsuboi Y, Maeda K, Ishihara Y, Suzuki K. Analysis of Repeated Measurements of Serum Carotenoid Levels and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in Japan. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113369. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Li K, Xu SN, Zhang JK, Ma MH, Liu Y. Higher serum carotenoid concentrations were associated with the lower risk of cancer-related death: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr Res. 2024;126:88-98. [CrossRef]

- Leermakers ET, Darweesh SK, Baena CP, et al. The effects of lutein on cardiometabolic health across the life course: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):481-494. [CrossRef]

- Rowles JL, Erdman JW. Carotenoids and their role in cancer prevention. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020;1865(11):158613. [CrossRef]

- Voutilainen S, Nurmi T, Mursu J, Rissanen TH. Carotenoids and cardiovascular health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1265-1271. [CrossRef]

- Mook K, Laraia BA, Oddo VM, Jones-Smith JC. Food Security Status and Barriers to Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Two Economically Deprived Communities of Oakland, California, 2013-2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E21. [CrossRef]

- Pessoa MC, Mendes LL, Gomes CS, Martins PA, Velasquez-Melendez G. Food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in a urban population: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1012. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, Drewnowski A. Does diet cost mediate the relation between socioeconomic position and diet quality? Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(9):1059-1066. [CrossRef]

- Rabbitt MP, Reed-Jones M, Hales LJ, Burke MP, United States. Department of Agriculture. Economic Research Service. Household Food Security in the United States in 2023. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(2):684-692. [CrossRef]

- Jun S, Cowan AE, Dodd KW, et al. Association of food insecurity with dietary intakes and nutritional biomarkers among US children, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011-2016. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(3):1059-1069. [CrossRef]

- Leung CW, Tester JM. The Association between Food Insecurity and Diet Quality Varies by Race/Ethnicity: An Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2014 Results. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(10):1676-1686. [CrossRef]

- Leung CW, Epel ES, Ritchie LD, Crawford PB, Laraia BA. Food Insecurity Is Inversely Associated with Diet Quality of Lower-Income Adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(12):1943-1953.e2. [CrossRef]

- Litton MM, Beavers AW. The Relationship between Food Security Status and Fruit and Vegetable Intake during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):712. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm.

- Rabbitt MP, Reed-Jones M, Hales LJ, Burke MP. Household Food Security in the United States in 2023 (Report No. ERR-337). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Procedure Manual. Vitamin A, Vitamin E, and Carotenoids in Serum NHANES 2001–2002. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2001/labmethods/l06vit_b_met_aecar.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Procedure Manual. A / E / Carotene Vitamin Profile in Serum NHANES 2003–2004. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2003/labmethods/l45vit_c_met_vitae_carotenoids.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Laboratory Procedure Manual. Vitamin A, Vitamin E, and Carotenoids in Serum NHANES 2005–2006. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2005/labmethods/vitaec_d_met_aecar.pdf.

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Definitions of Food Security. Accessed November 11, 2024. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/.

- National Center for Health Statistics. The Linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death Index — 2019 Linked Mortality File (LMF): Linkage Methodology and Analytic Considerations, June 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/public-use-linked-mortality-file-description.pdf.

- Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(9):1591-1602. [CrossRef]

- Bufka J, Vaňková L, Sýkora J, Křížková V. Exploring carotenoids: Metabolism, antioxidants, and impacts on human health. J Funct Foods. 2024;118:106284. [CrossRef]

- Maiani G, Periago Castón MJ, Catasta G, et al. Carotenoids: Actual knowledge on food sources, intakes, stability and bioavailability and their protective role in humans. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009;53(S2). [CrossRef]

- Khachik F, Spangler CJ, Smith JC, Canfield LM, Steck A, Pfander H. Identification, quantification, and relative concentrations of carotenoids and their metabolites in human milk and serum. Anal Chem. 1997;69(10):1873-1881. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium, and Carotenoids. National Academies Press (US); 2000. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225483/.

- Kim JH, Na HJ, Kim CK, et al. The non-provitamin A carotenoid, lutein, inhibits NF-κB-dependent gene expression through redox-based regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/Akt and NF-κB-inducing kinase pathways: Role of H2O2 in NF-κB activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(6):885-896. [CrossRef]

- Murillo AG, Fernandez ML. Potential of Dietary Non-Provitamin A Carotenoids in the Prevention and Treatment of Diabetic Microvascular Complications. Adv Nutr. 2016;7(1):14-24. [CrossRef]

- Kaulmann A, Bohn T. Carotenoids, inflammation, and oxidative stress--implications of cellular signaling pathways and relation to chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res N Y N. 2014;34(11):907-929. [CrossRef]

- Rao AV, Rao LG. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55(3):207-216. [CrossRef]

- Buijsse B, Feskens EJM, Schlettwein-Gsell D, et al. Plasma carotene and alpha-tocopherol in relation to 10-y all-cause and cause-specific mortality in European elderly: the Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly, a Concerted Action (SENECA). Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):879-886. [CrossRef]

- Bates CJ, Hamer M, Mishra GD. Redox-modulatory vitamins and minerals that prospectively predict mortality in older British people: the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(1):123-132. [CrossRef]

- Lauretani F, Semba RD, Dayhoff-Brannigan M, et al. Low total plasma carotenoids are independent predictors of mortality among older persons: the InCHIANTI study. Eur J Nutr. 2008;47(6):335-340. [CrossRef]

- Buijsse B, Feskens EJ, Schlettwein-Gsell D, et al. Plasma carotene and α-tocopherol in relation to 10-y all-cause and cause-specific mortality in European elderly: the Survey in Europe on Nutrition and the Elderly, a Concerted Action (SENECA). Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):879-886. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Cheang I, Tang Y, et al. Associations of Serum Carotenoids With Risk of All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Hypertensive Adults. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12(4):e027568. [CrossRef]

- Lin B, Liu Z, Li D, Zhang T, Yu C. Associations of serum carotenoids with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in adults with MAFLD. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;34(10):2315-2324. [CrossRef]

- Han GM, Meza JL, Soliman GA, Islam KMM, Watanabe-Galloway S. Higher levels of serum lycopene are associated with reduced mortality in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res. 2016;36(5):402-407. [CrossRef]

- Peng X, Zhu J, Lynn HS, Zhang X. Serum Nutritional Biomarkers and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality in U.S. Adults with Metabolic Syndrome: The Results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006. Nutrients. 2023;15(3):553. [CrossRef]

- Qiu Z, Chen X, Geng T, et al. Associations of Serum Carotenoids With Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality Among Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes: Results From NHANES. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(6):1453-1461. [CrossRef]

- Krinsky NI, Mayne ST, Sies H, eds. Carotenoids in Health and Disease. 0 ed. CRC Press; 2004. [CrossRef]

- Wang XD, Russell RM. Procarcinogenic and anticarcinogenic effects of beta-carotene. Nutr Rev. 1999;57(9 Pt 1):263-272. [CrossRef]

- Chang R, Javed Z, Taha M, et al. Food insecurity and cardiovascular disease: Current trends and future directions. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;9:100303. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Wang X, Li X, et al. Food Insecurity and Premature Mortality and Life Expectancy in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184(3):301. [CrossRef]

- Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and Socioeconomic Disparities in Chronic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6-9. [CrossRef]

- Litton MM, Beavers AW. The Relationship between Food Security Status and Fruit and Vegetable Intake during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):712. [CrossRef]

- Hong YR, Wang R, Case S, Jo A, Turner K, Ross KM. Association of food insecurity with overall and disease-specific mortality among cancer survivors in the US. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32(5):309. [CrossRef]

- Odoms-Young A, Brown AGM, Agurs-Collins T, Glanz K. Food Insecurity, Neighborhood Food Environment, and Health Disparities: State of the Science, Research Gaps and Opportunities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;119(3):850-861. [CrossRef]

- Bevel MS, Tsai MH, Parham A, Andrzejak SE, Jones S, Moore JX. Association of Food Deserts and Food Swamps With Obesity-Related Cancer Mortality in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(7):909. [CrossRef]

| Food Security Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High n=9,721 |

Marginal n=945 |

Low n=1,115 |

Very Low n=574 |

P | |

| Age, years | 47.6 ± 0.4 | 42.4 ± 0.8 | 40.2 ± 0.6 | 41.2 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 5,017 (49.6) | 443 (44.7) | 549 (47.2) | 283 (46.2) | 0.004 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| NH-White | 5,709 (77.4) | 311 (52.8) | 301 (46.9) | 205 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| NH-Black | 1,831 (9.1) | 248 (19.4) | 240 (16.3) | 166 (20.1) | |

| Hispanic | 1,806 (8.5) | 361 (23.9) | 543 (32.7) | 175 (23.0) | |

| Others | 375 (5.0) | 25 (3.9) | 31 (4.1) | 28 (6.3) | |

| Educational Attainment | |||||

| Below high school | 2,335 (14.7) | 411 (31.4) | 591 (40.0) | 273 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| High school graduate | 2,353 (25.2) | 245 (29.9) | 244 (26.0) | 141 (29.1) | |

| College or above | 5,033 (60.1) | 289 (38.7) | 280 (34.0) | 160 (32.5) | |

| Family Income-to-Poverty Ratio | |||||

| <1.30 | 1,646 (11.9) | 523 (46.8) | 735 (59.5) | 403 (63.3) | <0.001 |

| 1.30 to <3.50 | 3,971 (63.6) | 372 (45.3) | 351 (36.8) | 166 (35.2) | |

| ≥3.50 | 4,104 (51.5) | 50 (7.8) | 29 (3.7) | 5 (1.5) | |

| Smoking Status | |||||

| Never | 4,987 (51.4) | 444 (43.4) | 522 (42.8) | 235 (38.8) | <0.001 |

| Former | 2,784 (26.4) | 205 (21.0) | 229 (19.7) | 93 (14.4) | |

| Current | 1,950 (22.2) | 296 (35.6) | 364 (37.4) | 246 (46.8) | |

| Leisure-time Physical Activity a | |||||

| Inactive | 3,197 (27.4) | 378 (35.5) | 487 (39.9) | 232 (36.1) | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 3,554 (36.4) | 317 (34.4) | 367 (32.4) | 226 (40.0) | |

| Vigorous | 2,970 (36.2) | 250 (30.2) | 261 (27.7) | 116 (23.9) | |

| Alcohol Consumption b | |||||

| None | 4,067 (36.4) | 478 (45.9) | 528 (43.1) | 266 (44.2) | <0.001 |

| Light-to-moderate | 2,963 (31.4) | 146 (15.5) | 187 (19.2) | 92 (14.6) | |

| Heavy | 2,691 (32.2) | 321 (38.6) | 400 (37.7) | 216 (41.2) | |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 154 (1.6) | 12 (1.6) | 23 (3.1) | 9 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Normal (18.5 to 24.9) | 2,852 (31.7) | 247 (25.1) | 311 (30.3) | 163 (30.2) | |

| Overweight (25.0 to 29.9) | 3,574 (35.2) | 324 (32.5) | 380 (31.4) | 193 (31.6) | |

| Obese (>30) | 3,141 (31.4) | 362 (40.8) | 401 (35.2) | 209 (36.4) | |

| Dietary Supplement Use | 5,238 (56.2) | 360 (39.4) | 354 (36.9) | 188 (35.9) | <0.001 |

| Healthy Eating Index c | 52.8 ± 0.3 | 47.8 ± 0.6 | 48.3 ± 0.5 | 47.1 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Underlying Clinical Conditions | |||||

| Cancer | 981 (8.9) | 70 (8.8) | 58 (4.8) | 27 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 943 (6.8) | 94 (8.3) | 93 (6.9) | 57 (7.4) | 0.57 |

| Diabetes | 994 (7.2) | 118 (9.6) | 134 (8.2) | 77 (11.8) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 3,334 (29.2) | 306 (30.5) | 308 (23.9) | 193 (30.1) | 0.08 |

| All Causes | Cancer | Cardiovascular Disease | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | HR (95% CI) c | No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | HR (95% CI) c | No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | HR (95% CI) c | |||

| Food Security | |||||||||||

| High | 2,663 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 550 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 878 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Marginal | 227 | 1.34 (1.12-1.60) | 1.21 (1.01-1.46) | 55 | 1.12 (0.80-1.55) | 0.98 (0.69-1.38) | 71 | 1.40 (1.01-1.94) | 1.26 (0.90-1.76) | ||

| Low | 205 | 1.24 (1.01-1.53) | 1.07 (0.86-1.33) | 38 | 0.79 (0.56-1.12) | 0.70 (0.48-1.01) | 59 | 1.16 (0.85-1.60) | 0.97 (0.69-1.35) | ||

| Very low | 121 | 1.57 (1.20-2.05) | 1.37 (1.07-1.76) | 22 | 1.26 (0.84-1.88) | 1.13 (0.76-1.69) | 38 | 1.69 (1.20-2.38) | 1.45 (1.03-2.03) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.58 | 0.009 | 0.12 | |||||

| α-Carotene | |||||||||||

| Q1 | 752 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 147 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 262 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Q2 | 834 | 0.72 (0.64-0.81) | 0.82 (0.74-0.92) | 177 | 0.71 (0.54-0.92) | 0.84 (0.64-1.10) | 269 | 0.67 (0.54-0.84) | 0.76 (0.61-0.95) | ||

| Q3 | 805 | 0.58 (0.51-0.66) | 0.75 (0.66-0.86) | 168 | 0.73 (0.55-0.96) | 0.97 (0.72-1.30) | 251 | 0.55 (0.44-0.69) | 0.72 (0.57-0.92) | ||

| Q4 | 824 | 0.48 (0.42-0.56) | 0.70 (0.61-0.81) | 173 | 0.56 (0.43-0.72) | 0.89 (0.66-1.20) | 264 | 0.44 (0.36-0.55) | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |||||

| β -Carotene | |||||||||||

| Q1 | 916 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 173 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 307 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Q2 | 811 | 0.68 (0.59-0.78) | 0.76 (0.66-0.87) | 155 | 0.79 (0.61-1.02) | 0.89 (0.68-1.15) | 276 | 0.70 (0.56-0.86) | 0.78 (0.63-0.97) | ||

| Q3 | 693 | 0.59 (0.52-0.68) | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | 156 | 0.59 (0.46-0.76) | 0.74 (0.55-0.99) | 222 | 0.64 (0.50-0.81) | 0.81 (0.62-1.05) | ||

| Q4 | 717 | 0.53 (0.46-0.61) | 0.74 (0.63-0.87) | 165 | 0.57 (0.45-0.73) | 0.81 (0.60-1.08) | 221 | 0.50 (0.40-0.62) | 0.76 (0.58-0.99) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.09 | <0.001 | 0.08 | |||||

| β -Cryptoxanthin | |||||||||||

| Q1 | 628 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 114 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 228 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Q2 | 763 | 0.81 (0.71-0.92) | 0.90 (0.79-1.03) | 148 | 0.85 (0.66-1.08) | 0.92 (0.71-1.20) | 250 | 0.80 (0.64-0.99) | 0.92 (0.73-1.17) | ||

| Q3 | 808 | 0.68 (0.59-0.78) | 0.82 (0.70-0.96) | 175 | 0.54 (0.40-0.74) | 0.66 (0.48-0.90) | 253 | 0.75 (0.64-0.89) | 0.93 (0.77-1.14) | ||

| Q4 | 1,009 | 0.55 (0.47-0.64) | 0.78 (0.66-0.91) | 226 | 0.40 (0.31-0.52) | 0.56 (0.43-0.74) | 313 | 0.64 (0.50-0.82) | 0.98 (0.75-1.28) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.77 | |||||

| Total Lycopene | |||||||||||

| Q1 | 259 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 55 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 90 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Q2 | 379 | 0.77 (0.67-0.88) | 0.81 (0.72-0.91) | 82 | 0.86 (0.65-1.13) | 0.90 (0.69-1.17) | 124 | 0.75 (0.58-0.96) | 0.81 (0.65-1.01) | ||

| Q3 | 484 | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | 0.79 (0.70-0.89) | 108 | 0.76 (0.57-1.02) | 0.81 (0.61-1.08) | 158 | 0.72 (0.57-0.91) | 0.81 (0.64-1.01) | ||

| Q4 | 880 | 0.56 (0.45-0.69) | 0.65 (0.52-0.81) | 173 | 0.57 (0.36-0.91) | 0.67 (0.42-1.08) | 297 | 0.57 (0.39-0.83) | 0.68 (0.47-1.00) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.03 | |||||

| Lutein/Zeaxanthin | |||||||||||

| Q1 | 814 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 162 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | 282 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) | ||

| Q2 | 731 | 0.65 (0.58-0.72) | 0.71 (0.65-0.79) | 142 | 0.59 (0.48-0.74) | 0.65 (0.52-0.81) | 229 | 0.57 (0.47-0.69) | 0.63 (0.51-0.77) | ||

| Q3 | 768 | 0.58 (0.52-0.65) | 0.68 (0.61-0.77) | 165 | 0.50 (0.36-0.68) | 0.59 (0.43-0.81) | 237 | 0.50 (0.40-0.62) | 0.59 (0.47-0.74) | ||

| Q4 | 901 | 0.54 (0.48-0.61) | 0.70 (0.61-0.79) | 196 | 0.52 (0.42-0.66) | 0.69 (0.54-0.87) | 297 | 0.53 (0.45-0.62) | 0.71 (0.59-0.85) | ||

| P trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Food Security Status | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Marginal | Low | Very Low | |||||||||

| Serum Concentrations a |

No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b | No. of Death |

HR (95% CI) b |

P Interaction |

|||

| α-Carotene | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | 629 | 1 (ref.) | 68 | 1 (ref.) | 74 | 1 (ref.) | 53 | 1 (ref.) | 0.60 | |||

| Q2 | 656 | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | 55 | 0.67 (0.41-1.10) | 60 | 0.87 (0.54-1.41) | 34 | 0.69 (0.43-1.49) | ||||

| Q3 | 721 | 0.78 (0.68-0.90) | 58 | 0.70 (0.43-1.12) | 37 | 0.60 (0.37-0.96) | 18 | 0.52 (0.24-1.13) | ||||

| Q4 | 657 | 0.70 (0.59-0.83) | 46 | 0.62 (0.40-0.97) | 33 | 0.90 (0.48-1.71) | 16 | 1.07 (0.46-2.51) | ||||

| P trend | <0.001 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| β -Carotene | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | 528 | 1 (ref.) | 69 | 1 (ref.) | 67 | 1 (ref.) | 53 | 1 (ref.) | 0.67 | |||

| Q2 | 576 | 0.77 (0.65-0.92) | 49 | 0.67 (0.40-1.12) | 47 | 0.91 (0.50-1.67) | 21 | 0.46 (0.22-0.96) | ||||

| Q3 | 691 | 0.74 (0.62-0.88) | 47 | 0.58 (0.36-0.93) | 47 | 0.82 (0.55-1.22) | 26 | 0.82 (0.49-1.40) | ||||

| Q4 | 807 | 0.75 (0.62-0.90) | 55 | 0.76 (0.52-1.11) | 37 | 0.72 (0.40-1.30) | 17 | 0.82 (0.39-1.75) | ||||

| P trend | 0.004 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.48 | ||||||||

| β -Cryptoxanthin | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | 796 | 1 (ref.) | 72 | 1 (ref.) | 84 | 1 (ref.) | 57 | 1 (ref.) | 0.28 | |||

| Q2 | 666 | 0.92 (0.78-1.08) | 61 | 1.08 (0.67-1.75) | 48 | 1.00 (0.61-1.64) | 33 | 0.64 (0.35-1.16) | ||||

| Q3 | 671 | 0.86 (0.73-1.00) | 44 | 0.70 (0.41-1.20) | 31 | 0.54 (0.27-1.05) | 17 | 0.62 (0.29-1.31) | ||||

| Q4 | 526 | 0.77 (0.66-0.91) | 49 | 0.78 (0.46-1.32) | 40 | 1.00 (0.59-1.70) | 13 | 0.74 (0.35-1.56) | ||||

| P trend | 0.003 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.19 | ||||||||

| Total Lycopene | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | 717 | 1 (ref.) | 70 | 1 (ref.) | 61 | 1 (ref.) | 32 | 1 (ref.) | 0.02 | |||

| Q2 | 412 | 0.84 (0.72-0.96) | 33 | 0.63 (0.37-1.03) | 28 | 0.64 (0.27-1.51) | 11 | 0.75 (0.22-2.63) | ||||

| Q3 | 310 | 0.77 (0.67-0.88) | 30 | 0.66 (0.35-1.23) | 21 | 1.17 (0.46-2.94) | 18 | 0.61 (0.24-1.56) | ||||

| Q4 | 211 | 0.64 (0.50-0.80) | 17 | 0.69 (0.34-1.41) | 20 | 0.88 (0.41-1.90) | 11 | 0.61 (0.28-1.33) | ||||

| P trend | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.17 | ||||||||

| Lutein/Zeaxanthin | ||||||||||||

| Q1 | 711 | 1 (ref.) | 73 | 1 (ref.) | 67 | 1 (ref.) | 50 | 1 (ref.) | 0.08 | |||

| Q2 | 628 | 0.72 (0.65-0.80) | 44 | 0.48 (0.26-0.88) | 54 | 1.17 (0.76-1.82) | 32 | 0.54 (0.29-1.03) | ||||

| Q3 | 612 | 0.70 (0.62-0.80) | 50 | 0.62 (0.40-0.96) | 44 | 0.82 (0.52-1.29) | 25 | 0.46 (0.22-1.00) | ||||

| Q4 | 701 | 0.70 (0.61-0.80) | 60 | 0.75 (0.50-1.13) | 40 | 1.06 (0.63-1.77) | 13 | 0.30 (0.12-0.71) | ||||

| P trend | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.009 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).