1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a significant surge in exploration into the design and fabrication of metal-organic compounds. This is primarily driven by their tuneable and functional properties that bring out wide range of application in the fields of ion-exchange, hydrogen storage, biology, catalysis, non-linear optics, and photoluminescence [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among those metal-organic compounds, coordination polymers stand out as structures formed through the combination of metal centers and various bridging ligands, offering a fascinating array of network architectures and topologies [

6]. Variable coordination modes of bridging organic ligands render them capable of constructing metal-organic compounds with tailored dimensionalities [

7]. However, for achieving desired structural topologies in coordination compounds, the synthetic strategy requires a careful manipulation of reaction parameters such as coordination geometry, pH, solvent temperature, etc., which influence the binding mode of the ligands as well as the self-assemblies of the molecules [

8,

9].

For the synthesis of mononuclear and poly-nuclear coordination compounds, aromatic carboxylates are frequently employed as they possess desirable topologies from a crystal engineering perspective on account of their various coordination motifs, thermal endurance and capability to form bridging compounds with transition metals [

10,

11]. Compounds that contain carboxylate synthons are excellent motifs for obtaining metal-organic hybrid assemblies and find applications in varying domains such as in biology etc. [

12,

13,

14]. Specifically, both

in vitro and

in vivo anti-cancer studies has been performed for such systems with significant efficacy [

15,

16]. Aminopyridine ligands have also been used very extensively in the synthesis of compounds starting from simple mononuclear to polymeric coordination solids (CP’s) holding different dimensionalities [

17]. Another interesting feature possessed by these compounds is their affinity to show different hydrogen bonds, like N‒H∙∙∙O between the amino NH and a coordinated carboxylate, which extends the structure from 1D to a 3D network [

18]. Extra stability also gets generated when π-stacking interactions are formed between the aromatic pyridyl ligands, which play a crucial role in stabilizing the supramolecular assemblies [

19]. 3-Aminopyridine is a simple molecule of the aminopyridine series which can act both as a monodentate ligand via binding through the most basic

N-pyridyl nitrogen, and a bridging ligand connecting two metal ions via the

N-pyridyl and

N-amino donor atoms [

20,

21]. 2-Aminopyridine is largely known for its diverse pharmacological importance, mostly for its usage in the synthesis of anti-inflammatories, antihistamines and the potential of its derivatives to coordinated with transition metals [

22,

23]. Several research groups have highlighted that the metal carboxylates are of significant importance due to their relevance in biological applications, including anticancer, antimicrobial, and antifungal activities [

24,

25,

26]. Moreover, such complexes hold promise for various applications in catalysis, magnetism, optics, and related areas [

27,

28]. Pyridine-based coordination compounds also demonstrate substantial pharmaceutical potential

viz. anti-inflammatory [

29,

30], anticancer [

31,

32], antimicrobial [

33,

34] etc.

The most important criteria for supramolecular association is the non-covalent interactions which efficiently setup the formation of captivating network architectures with befitting potential applications [

35,

36,

37]. The investigation of non-covalent interactions in metal-organic compounds has received substantial attention, with a special focus in illuminating the stability and organization of supramolecular assemblies [

38]. A lot number of experimental techniques have clarified the roles of both intra and intermolecular supramolecular interactions in the synthetic strategies and promotion of functional metal-organic compounds [

39,

40] .Among all types of non-covalent interactions, hydrogen bonding stands out as a powerful device in the creation of molecular solids due to its directional nature, selectivity, and reversible formation at ambient conditions [

41]. Its contribution has been the key in the stabilization of supramolecular architectures [

42]. Beyond the prominent hydrogen bonding networks exemplified by O–H···O and N–H···O, the subtle yet influential non-classical C–H···N interactions also serve pivotal roles in determining the stability of crystal structures [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. Aromatic π-stacking interactions and interactions involving metal-ligand chelate ring(CR) also influence the of supramolecular architectures in coordination compounds, thus emphasizing their vital significance not only in self-assembly but also in the investigation of the properties of functional materials [

49,

50,

51,

52]. In addition, weak, unusual C–H···π interactions with aromatic π systems also hold significant importance in both crystal packing and biological systems [

53].

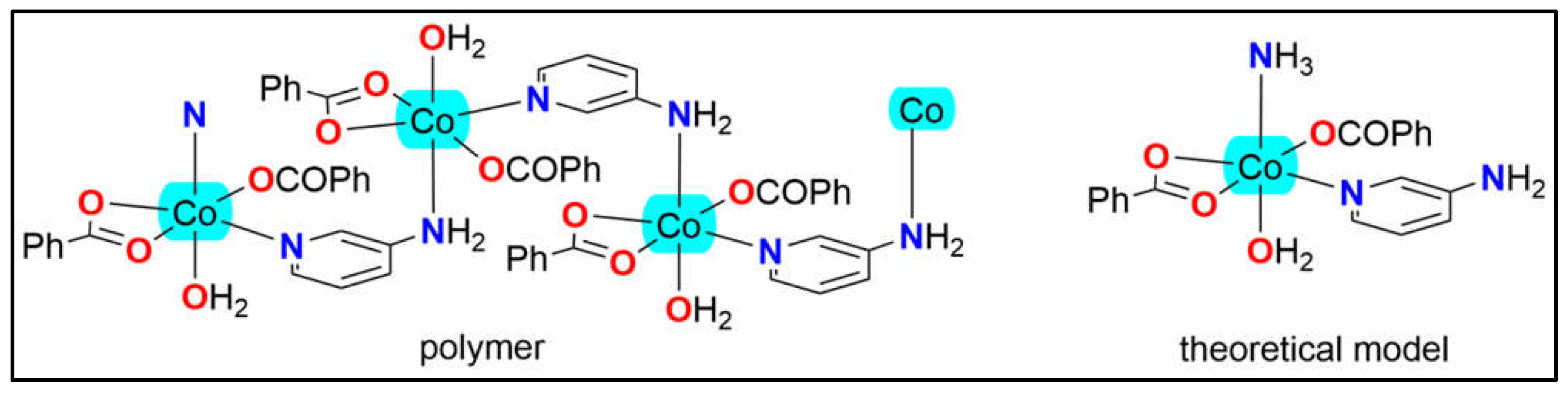

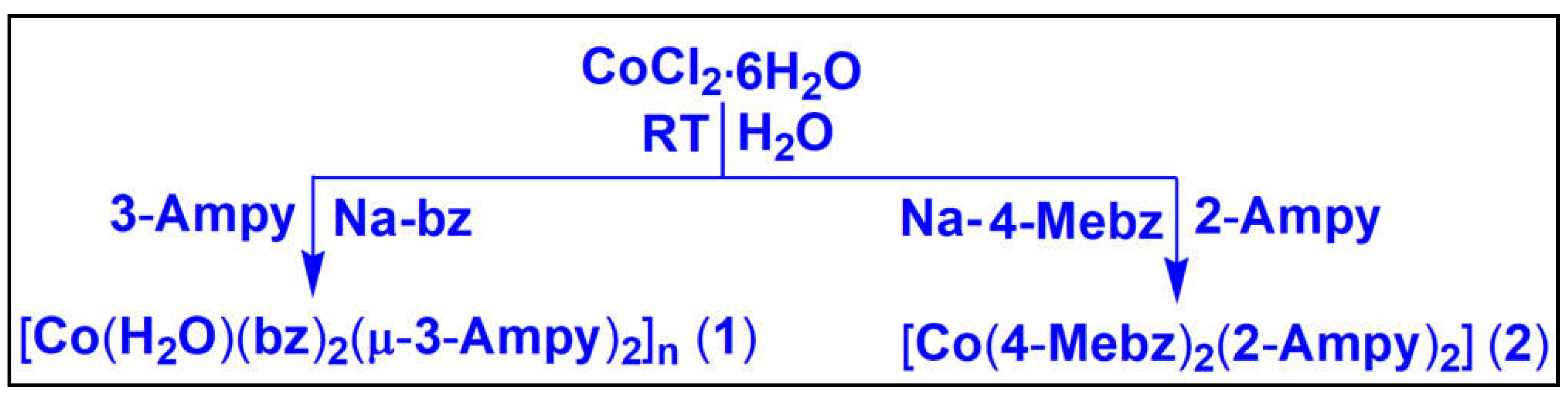

In this study, we devoted our attention to non-covalent interactions in metal-organic compounds by reporting the synthesis and crystal structures of two new Co(II) coordination compounds, viz. [Co(H2O)(bz)2(μ-3-Ampy)2]n (1) and [Co(4-Mebz)2(2-Ampy)2] (2). Compound 1 crystallizes as a 3-Ampy bridged Co(II) polymer; whereas, compound 2 crystallizes as a mononuclear Co(II) compound. Additionally, the synthesized compounds were characterized by single crystal XRD, elemental analysis, spectroscopic (FT-IR and electronic) techniques and TGA. Crystal structure analysis of the compounds reveals the presence of several non-covalent interactions which provide rigidity to the structures. Compound 1 reveals the presence of aromatic π stacking interactions along with some structure guiding hydrogen bonding interactions ( synthon) and intramolecular CR∙∙∙π interaction; whereas compound 2 unfolds the presence of N–H···O, C–H···O, C‒H∙∙∙C, C–H···π and N‒H∙∙∙CR interactions. We have also carried out theoretical studies to analyze the non-covalent H-bonding, π-stacking and C–H···π interactions present in the crystal structures. We have used DFT calculations, MEP surface analysis, NCI plot and QTAIM computational tools to explore the energetic features and the characteristics of the supramolecular assemblies. In this study, the in vitro antiproliferative activity of compounds 1 and 2 was evaluated against Dalton’s lymphoma (DL) malignant cancer cell line. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis assays were used to assess the ability of these compounds to inhibit growth and induce cell death in DL cells. Additionally, molecular docking study was conducted to investigate the structure activity relationship of these compounds. This combined approach aimed at comprehensive evaluation of the potential of compounds 1 and 2 as anticancer agents and identify the key structural features responsible for their activity. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were utilized to assess the potential cytotoxic effects of the tested compounds on normal, non-cancerous cells. Cisplatin, a well-known chemotherapeutic drug, was used as a reference standard in these experiments. By comparing the cytotoxic effects of the tested compounds to those of cisplatin, it is possible to benchmark their efficacy and safety.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Syntheses and General Aspects

Synthesis of [Co(H

2O)(bz)

2(μ-3-Ampy)

2]

n(

1) has been carried out by reacting two equivalents of sodium salt of benzoic acid, one equivalent of CoCl

2·6H

2O and two equivalents of 3-Ampy at room temperature in aqueous medium. However, [Co(4-Mebz)

2(2-Ampy)

2](

2) has been produced by the reaction between one equivalent of CoCl

2·6H

2O, two equivalents of sodium salt of 4-Mebz and two equivalents of 2-Ampy at room temperature in aqueous medium. Both

1 and

2 are well soluble in water and common organic solvents. Room temperature μ

eff values are found to be 3.81 and 3.87 BM respectively, for compound

1 and

2, corresponding to three unpaired electrons per Co(II) centers [

54,

55,

56].

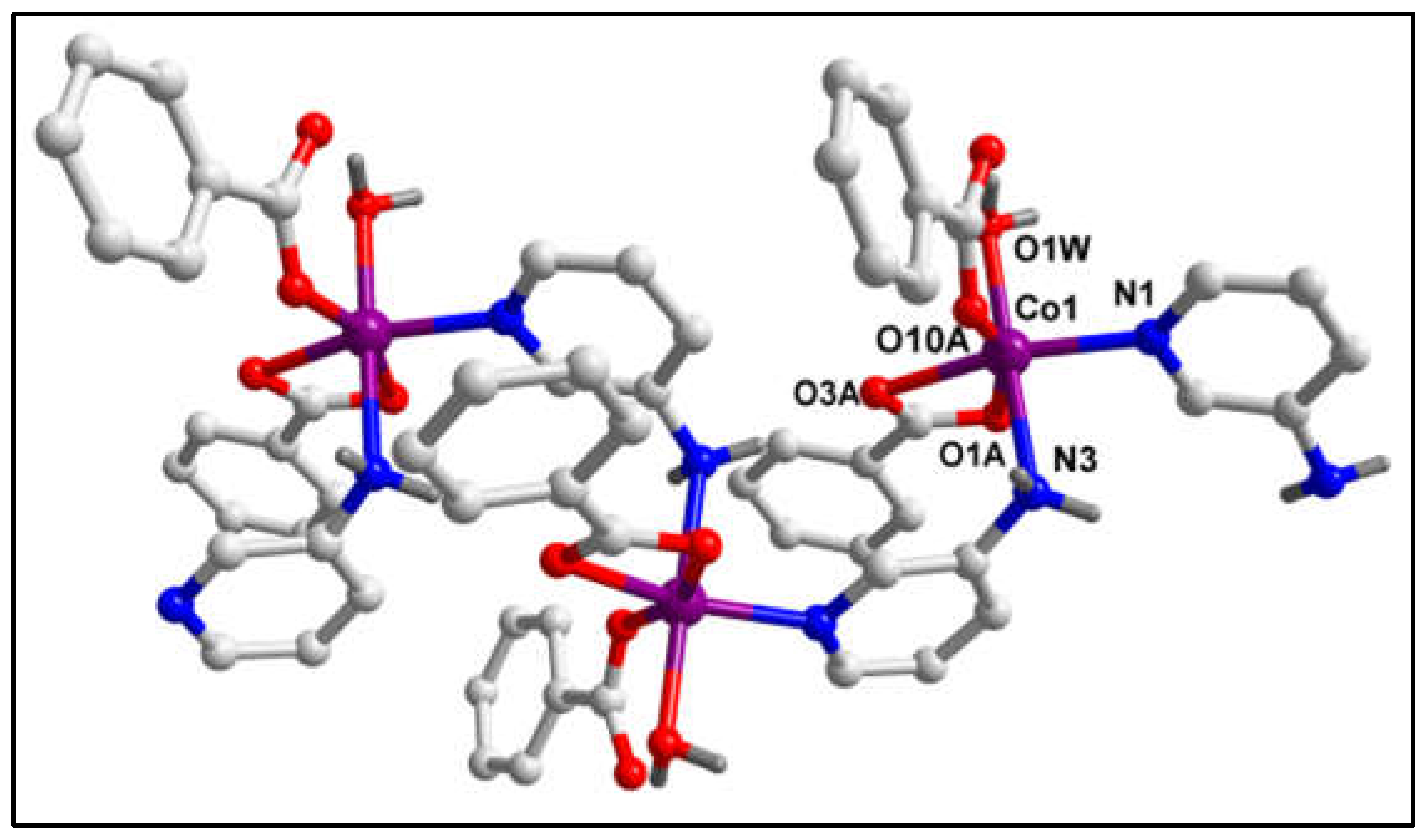

2.2. Crystal Structure Analysis

The molecular structure of polymeric compound

1 is shown in

Figure 1. Selected bond lengths and angles are presented in

Table 1. The single crystal X-ray diffraction study reveals that the compound crystallizes in monoclinic crystal system with P2

1/c space group. In the crystal structure of compound

1, there is a 1D polymeric chain which possesses Co(II) centers bridged by 3-Ampy moieties. Moreover, one water molecule, two bz and an another 3-Ampy moieties are also coordinated to the metal centers. Thus, each Co(II) center is hexa-coordinated with the O atom (O1W) from the water molecule, carboxyl O atom (O10A) from the monodentate bz, carboxyl O atoms (O1A and O3A) from the bidentate bz and N1, N3 atoms from the two coordinated 3-Ampy moieties. The coordination geometry around each Co(II) center is distorted octahedron where the axial sites are occupied by the O1W and N3 atoms while the equatorial sites are occupied by the O1A, O3A, O10A and N1 atoms. Distance between metal centers in compound

1 is found to be 6.05Å. The average Co‒O and Co‒N bond lengths are almost consistent with the previously reported Co(II) complexes [

57].

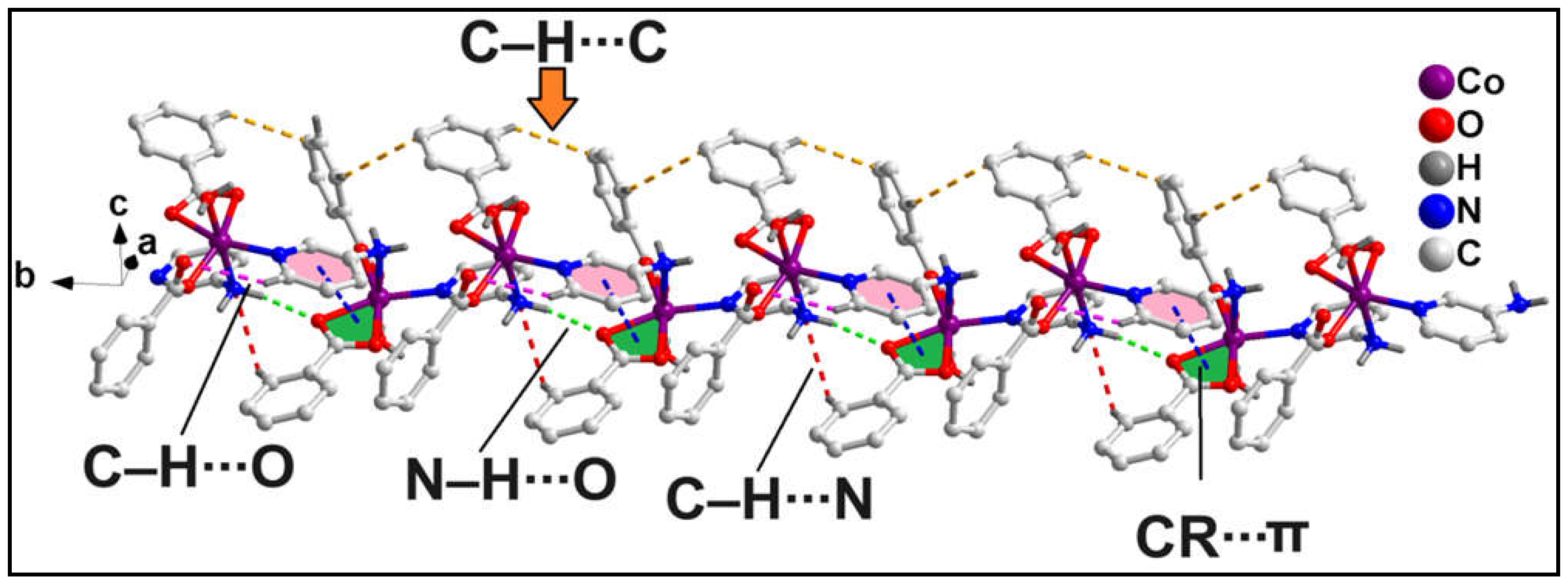

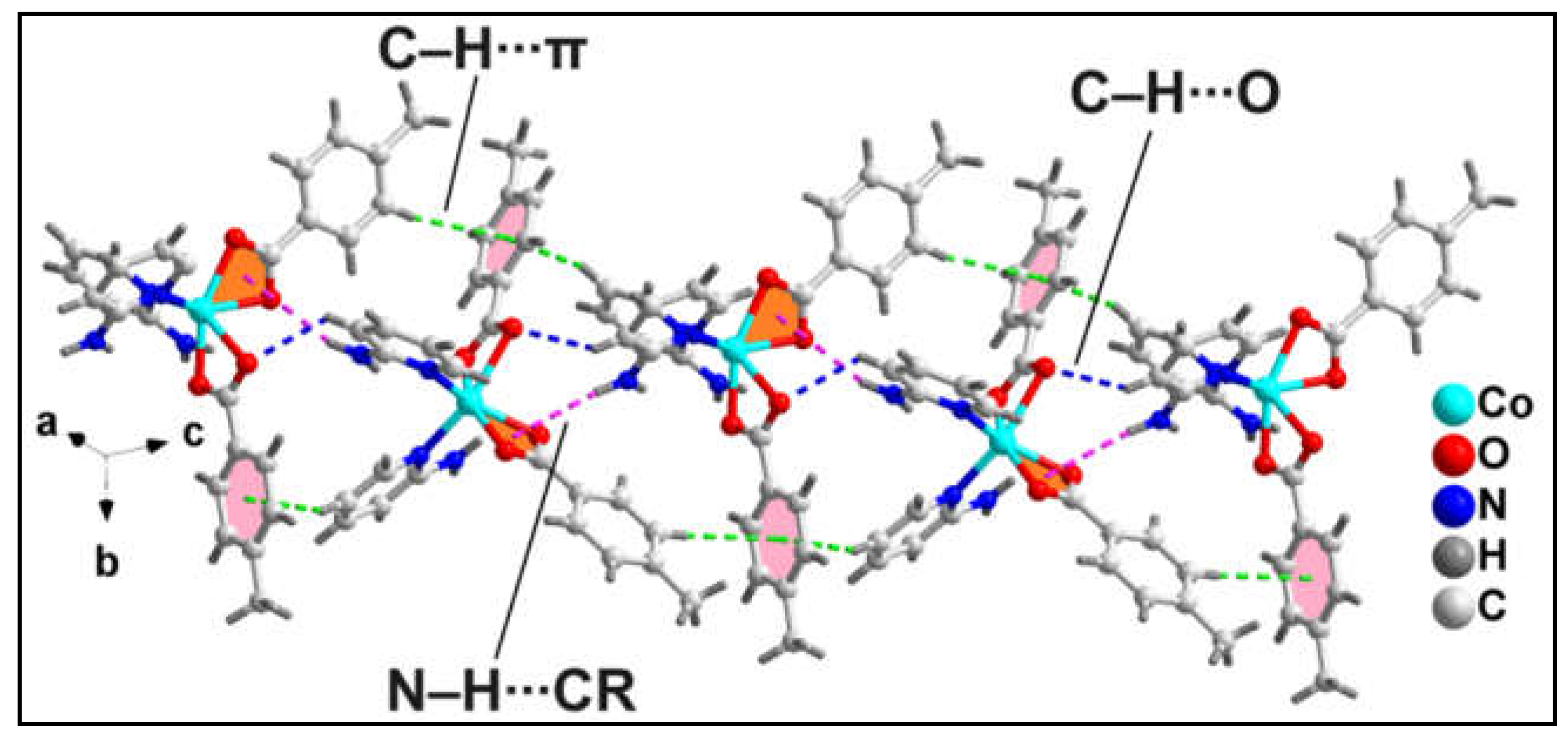

The 1D polymeric chain of compound

1 is stabilized by non-covalent intra-molecular C‒H∙∙∙O, N‒H∙∙∙O, C‒H∙∙∙N hydrogen bonding interactions along with intramolecular non-covalent CR∙∙∙π (CR = Chelate Ring) and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions (

Figure 2). ‒C6H6 fragments of the bridging 3-Ampy moieties are involved in C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding with the O12A atom from the monodentate bz moiety having C6‒H6∙∙∙O12A distance of 2.83 Å. Similarly, the ‒N3H3B fragments from the amino group of the 3-Ampy moieties are involved in N‒H∙∙∙O interactions with the O3A atom from the bidentate bz moieties having N3‒H3A∙∙∙O3A distance of 2.08 Å. C‒H∙∙∙N hydrogen bonding interactions are observed between the ‒C9AH9A fragments from the bidentate bz and N3 atom from the amino group of the 3-Ampy moieties with C9‒H9A∙∙∙N3 separation of 2.87 Å. Intramolecular CR∙∙∙π interaction is observed between the bidentate Co-bz chelate and the π-system of 3-Ampy moiety having centroid-centroid separation of 3.523 Å. Such kind of interaction involving metal-carboxylate(bidentate) chelate is very scarce in the literature. In addition, non-covalent C‒H∙∙∙C interactions are observed between bz moieties from two adjacent monomeric units [C6A‒H6A∙∙∙C16A = 3.17 Å, C(sp

2)-C(sp

2), C6A∙∙∙C16A= 3.96 Å; C14A‒H14A∙∙∙C8A = 3.30 Å; C(sp

2)-C(sp

2), C14A∙∙∙C8A= 3.96 Å].

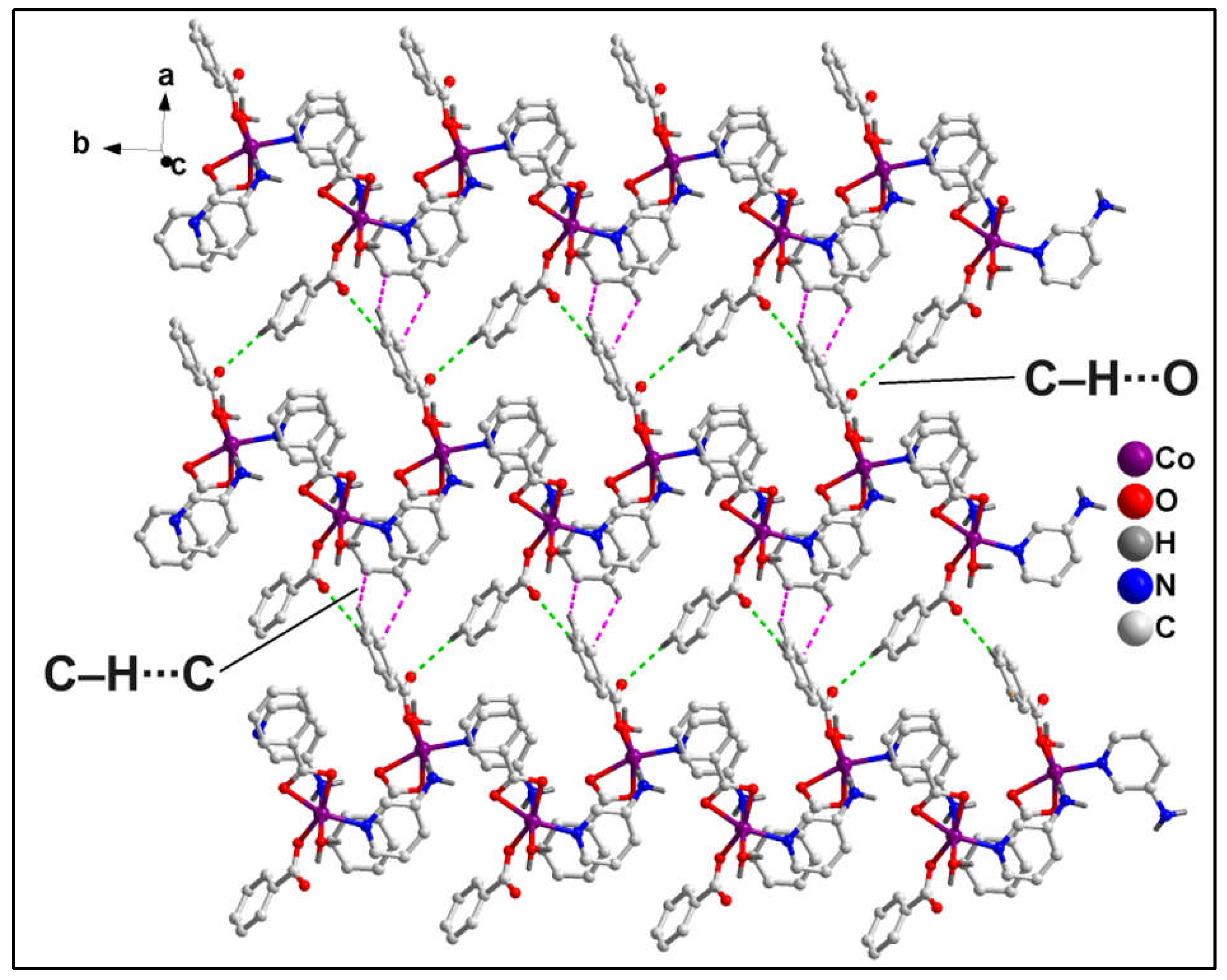

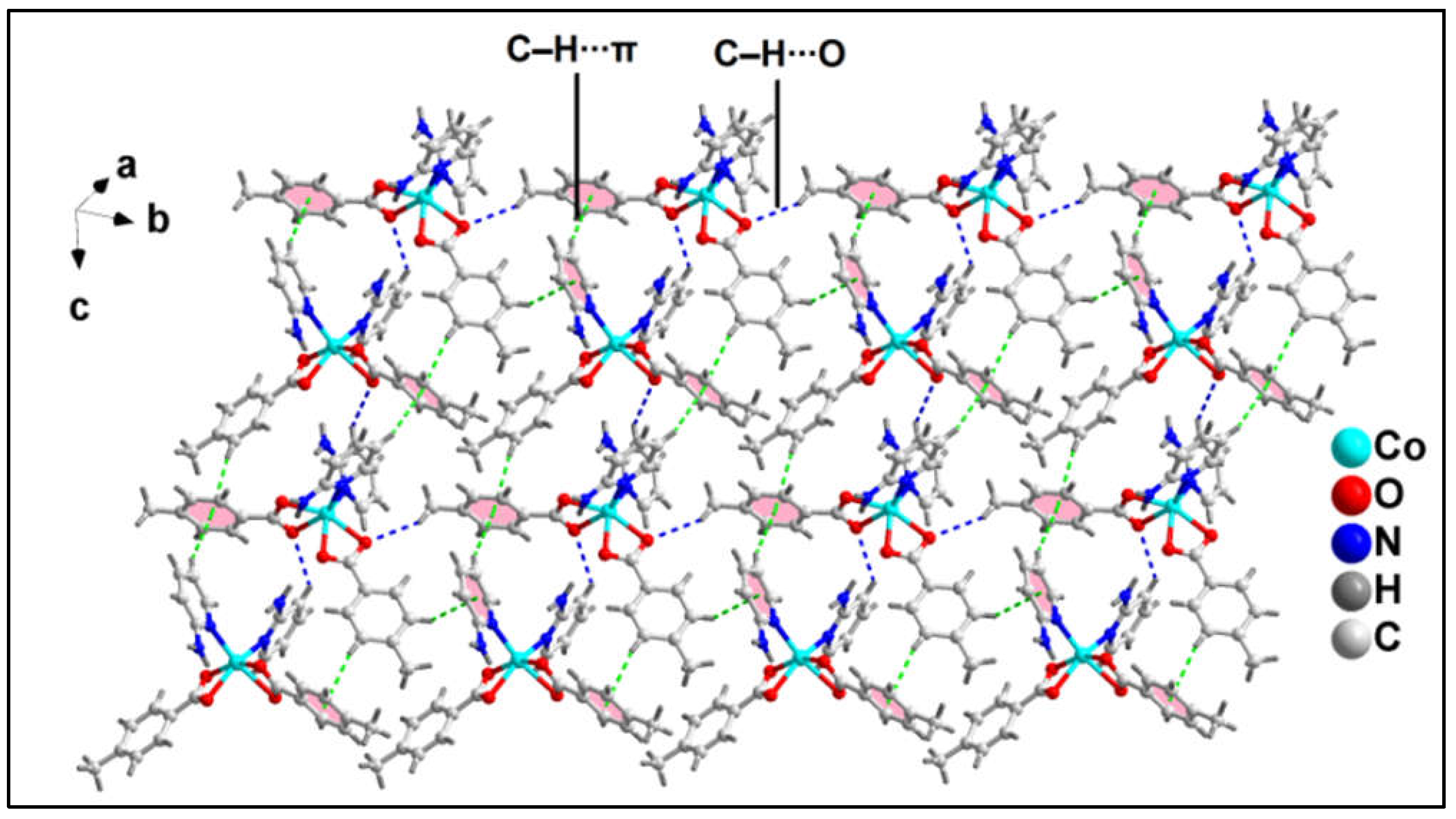

1D polymeric chains of compound

1 propagates along the crystallographic ab plane to form the layered architecture (

Figure 3) of the compound which is stabilized by C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions. The ‒C16AH16A fragments and carboxyl O12A atom of monodentate bz moieties from neighboring polymeric chains are involved in C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding having C16A‒H16A∙∙∙O12A separation of 2.56 Å. Moreover, the coordinated monodentate and bidentate bz moieties from adjacent polymeric chains are also involved in C‒H∙∙∙C interactions [C17A‒H17A∙∙∙C7A = 3.22 Å, C(sp

2)-C(sp

2), C17A∙∙∙C7A= 3.85 Å; C6A‒H6A∙∙∙C18A = 3.28 Å; C(sp

2)-C(sp

2), C6A∙∙∙C17A= 3.68 Å].

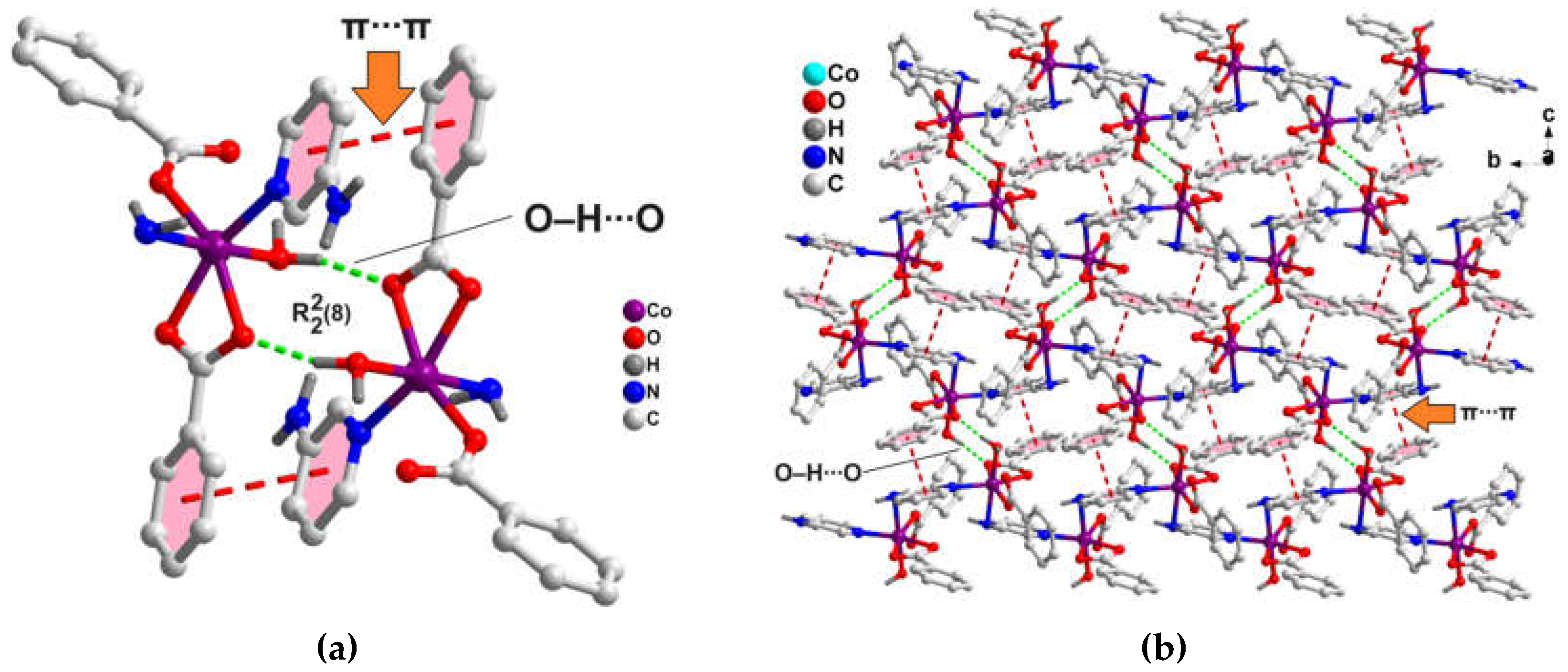

The 1D polymeric chains of the compound also propagates along the crystallographic bc plane to form the supramolecular layered assembly assisted by O‒H∙∙∙O and aromatic π-stacking interactions (

Figure 4b). Coordinated water molecule O1W and carboxyl O1A atom of bidentate bz moieties from two adjacent polymeric chains are involved in O‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding interactions having O1W‒H1WB∙∙∙O1A separation of 1.89 Å. This results in the generation of a

H-bonding synthon (

Figure 4a), as denoted by Etter’s graph set notation [

58]. Aromatic π-stacking interactions are observed between the π-systems of 3-Ampy and bz moieties from two adjacent polymeric chains having centroid(C4A-C9A)-centroid(C2-C6, N1) separation of 3.71 Å and slipped angle of 20.18° [

59]. A dimeric segment of this assembly (

Figure 4a) has been theoretically studied vide infra (see

Figure 11).

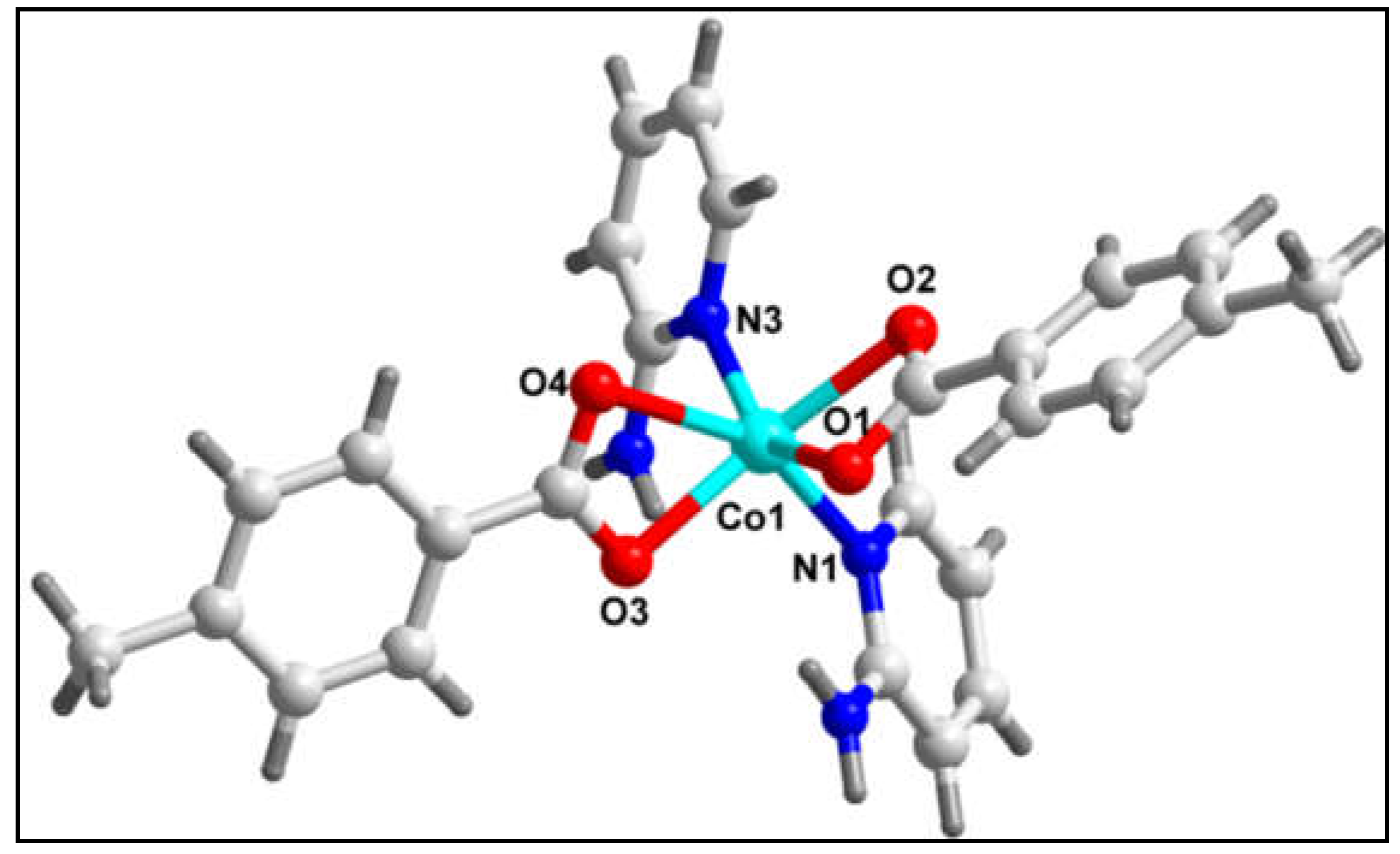

Figure 5 depicts the molecular structure of compound

2. Selected bond lengths and bond angles are summarized in

Table 1. The single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis reveals that the compound crystallizes in monoclinic crystal system with space group Cc. In the crystal structure of compound

2, the Co(II) centre is six coordinated with four O atoms (O1, O2, O3 and O4) from two 4-Mebz moieties and two N atoms (N1 and N3) from two 2-Ampy moieties. The coordination geometry around the Co(II) centre is distorted octahedron where the axial positions are occupied by O2 and O3 atoms whereas the equatorial positions are occupied by O1, O4, N1 and N3 atoms. The Co(II) centre deviates by 0.5199 Å from the mean equatorial plane containing O1, O4, N1 and N3 atoms. The average Co‒O and Co‒N bond distances are almost consistent with the previously reported Co(II) complexes [

60].

Adjacent monomeric units of the compound are interconnected via C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding, C‒H∙∙∙π and N‒H∙∙∙CR interactions, developing 1D supramolecular chain, which grow along the crystallographic c axis (

Figure 6). O4 carboxyl atom of 4-Mebz is involved in C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding interaction with the ‒C12H12 moiety of 2-Ampy of the neighboring monomeric units having C12‒H12∙∙∙O4 separation of 2.58 Å. The ‒C4H4 and ‒C17H17 fragments from 4-Mebz and 2-Ampy respectively, are involved in C‒H∙∙∙π interactions with the π-system of 4-Mebz from neighboring monomeric units having centroid (C20-C23, C25, C26)‒H4 and centroid(C20-C23, C25, C26)‒H17 distances of 2.79 and 2.60 Å, respectively. Unconventional N‒H∙∙∙CR interaction is found between the Co-4-Mebz chelate and the –N4H4B unit of 2-Ampy moiety of adjacent unit having N‒H∙∙∙CR distance of 3.00 Å.

Adjacent 1D chains of compound

2 are interlinked along the crystallographic a-axis by C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding and C‒H∙∙∙π interactions, leading to supramolecular layers, extending in the ac-plane (

Figure 7). C‒H∙∙∙O interactions are established between the ‒C24H24B fragment and O2 atom of 4-Mebz from two neighboring monomeric complex units with C24‒H24B∙∙∙O2 distance of 2.64 Å. Moreover, the ‒C7H7 moiety of 4-Mebz is involved in C‒H∙∙∙π interactions with the π-system of 2-Ampy from two adjacent monomers having centroid(C14-C18, N1)‒H7 separation of 2.73 Å.

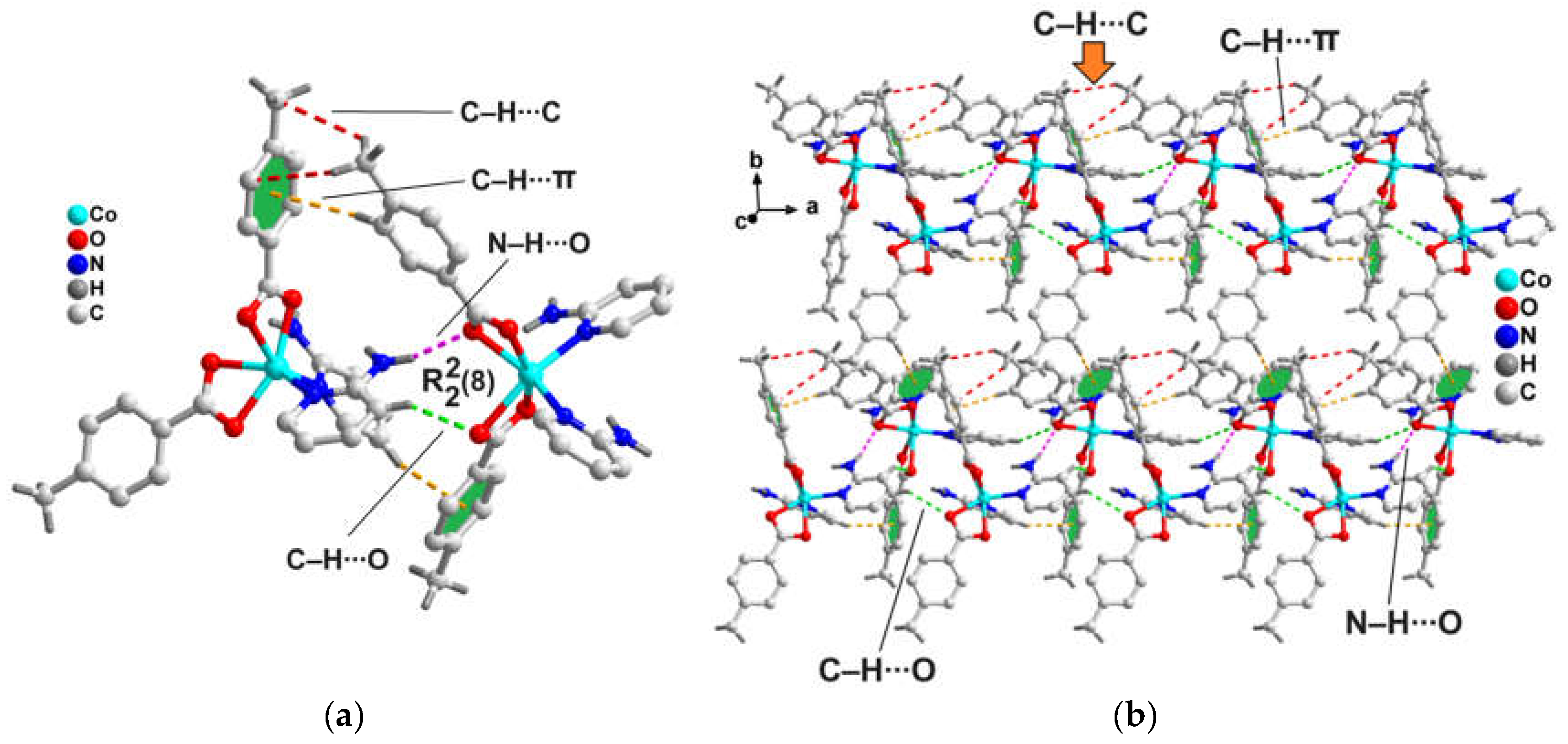

A closer look towards the crystal packing of compound

2 unfolds the presence of an interesting dimeric fragment (

Figure 8a) involving complex moieties and stabilized by C‒H∙∙∙O, N‒H∙∙∙O, C‒H∙∙∙C and C‒H∙∙∙π interactions. The C‒H∙∙∙O and N‒H∙∙∙O interactions results in the formation of a

H-bonding synthon, depicted by Etter’s graph set notation [

58]. C‒H∙∙∙O interactions are observed between the ‒C12H12 fragments of 2-Ampy moieties and O4 atom of 4-Mebz from two neighboring mononuclear complex units with C12‒H12∙∙∙O4 distance of 2.58 Å (

Table 2). Similarly, N‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding interactions are observed between the ‒N4H4B fragments of 2-Ampy and O1 atom of 4-Mebz moieties from two adjacent monomers having N4‒H4B∙∙∙O1 distance of 2.09 Å. Again, the ‒C4H4 moiety of one 4-Mebz is involved in C‒H∙∙∙π interactions with the π-system of 4-Mebz of the adjacent complex moiety in the dimer with centroid(C14-C18, N1)‒H7 separation of 2.79 Å (corresponding C‒H∙∙∙π angle of 163.1°). The C‒H∙∙∙C interactions are observed between the 4-Mebz moieties in the dimer [C6‒H6C∙∙∙C24 = 3.16 Å, C(sp

3)-C(sp

3), C6∙∙∙C24= 3.83 Å; C6‒H6B∙∙∙C25 = 3.22 Å; C(sp

3)-C(sp

2), C6∙∙∙C25 = 3.88 Å]. This dimeric fragment is utilized in the generation of another self-assembled layered architecture along the crystallographic ab plane (

Figure 8b). This supramolecular dimer has been established theoretically vide infra (

Figure 12).

2.3. Spectral Studies

2.3.1. FT-IR Spectroscopy

The FT-InfraRed spectra of

1 and

2 are performed in the frequency range of 4000-500 cm

-1 (

Figure S1). The broad absorption band in the spectrum of

1 in the region of 3200-3600 cm

-1 can be assigned to the O–H stretching vibration of the coordinated water molecule [

61,

62]. The spectrum also exhibits absorption bands corresponding to ρ

r (H

2O) (716 cm

-1) and ρ

w (H

2O) (685 cm

-1) supporting the presence of coordinated water molecule in

1 [

63]. The differences between the asymmetric ν

as(COO

-) and symmetric ν

s(COO

-) stretching vibrations of the carboxylate moieties of compound

1 (204, 176 cm

-1) suggest unidentate [

64] and chelate coordination modes of bz to the Co(II) centers in compound

1 [

65]. However, the difference between the asymmetric ν

as(COO

-) and symmetric ν

s(COO

-) stretching vibration of carboxylate moiety of

2 (191 cm

-1) indicate bidentate coordination of the 4-Mebz ligands present in the compound [

66]. The absence of bands at around 1710 cm

-1 in the spectra of both the compounds corroborates the deprotonation of the carboxyl groups of coordinated bz and 4-Mebz moties [

67]. In the spectra of both the compounds, the ring stretching modes of 3-Ampy and 2-Ampy ligands at 1601, 1507, 1435 and 1333 cm

-1 have shifted to higher wave numbers confirming the coordination via the pyridine ring N atom to the metal centers [

68]. The ring wagging vibrations of pyridine groups are also observed at around 655 and 716 cm

-1 in both the compounds [

69,

70]. The broad peak at 3423 cm

-1 for compound

2 is attributed to the N–H stretching vibration of the coordinated 2-Ampy molecule [

71]. Moreover, –NH

2 stretching and bending vibrations of 3-Ampy in compound

1 have shifted to lower wave numbers, whereas ‒NH

2 wagging mode shifts to higher wave number supporting the binding of amino group to the metal centers [

71].

2.3.2. Electronic spectroscopy

The electronic spectra of the compounds

1 and

2 were recorded in both the solid and aqueous phases and discussed in detail (

Figures S2 and S3). The spectra of the compounds indicate the presence of distorted octahedral Co(II) centers in

1 and

2, respectively [

48,

68,

72]. The absorption peaks for the π→π* transition of the aromatic ligands are obtained at the expected positions [

73,

74].

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis of the crystalline samples of compounds

1 and

2 was conducted between 25 and 800°C under a dinitrogen atmosphere at the heating rate of 10

◦C/min (

Figure S4). From the multistep weight loss process of compound

1, it is clearly evident that the coordinated water molecules are lost first, followed by the loss of the one of the coordinated bz moiety. A loss of 34.57 % (calcd: 33.66%) in the range of 25−269°C corresponds to coordinated water molecule and one of the bz moiety [

75]. The continuous weight loss of

1 between 270 and 550°C corresponds to the removal of the remaining benzoate moiety and 3-Ampy moiety [

76]. The compound

2 exhibits the first weight loss of 34.78% in the range 25-289°C, corresponding to two 2-Ampy ligands (calcd: 36.38%) [

77]. The second weight loss of 51.23% between 290 and 567°C corresponding to the removal of two 4-MeBz moiety(calcd: 52.23%) [

78].

2.5. Theoretical Study

The theoretical analysis is focused on examining the significant non-covalent interactions within both compounds that play a crucial role in determining their solid-state architecture. Theoretical study of compound

1 has been directed towards the π-stacking and O–H···O hydrogen bonds as depicted in

Figure 4a. These interactions are interchain and crucial for the development of the layered structure seen in compound

1 (Figure 4b). In the case of compound

2, our investigation covers the hydrogen bonding and C–H···π interactions, which are pivotal in its X-ray crystal packing as evidenced in

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8. It is important to note that the polymeric chain of compound

1 propagates through Co–N coordination bonds linking the amino group of the 3-Ampy ligand to the Co(II) metal center. For our computational studies, a simplified monomeric model has been employed, as shown in

Figure 9, where the amino group in the apical position is substituted with NH

3. This simplified model facilitates the examination of the interactions presented in

Figure 4a.

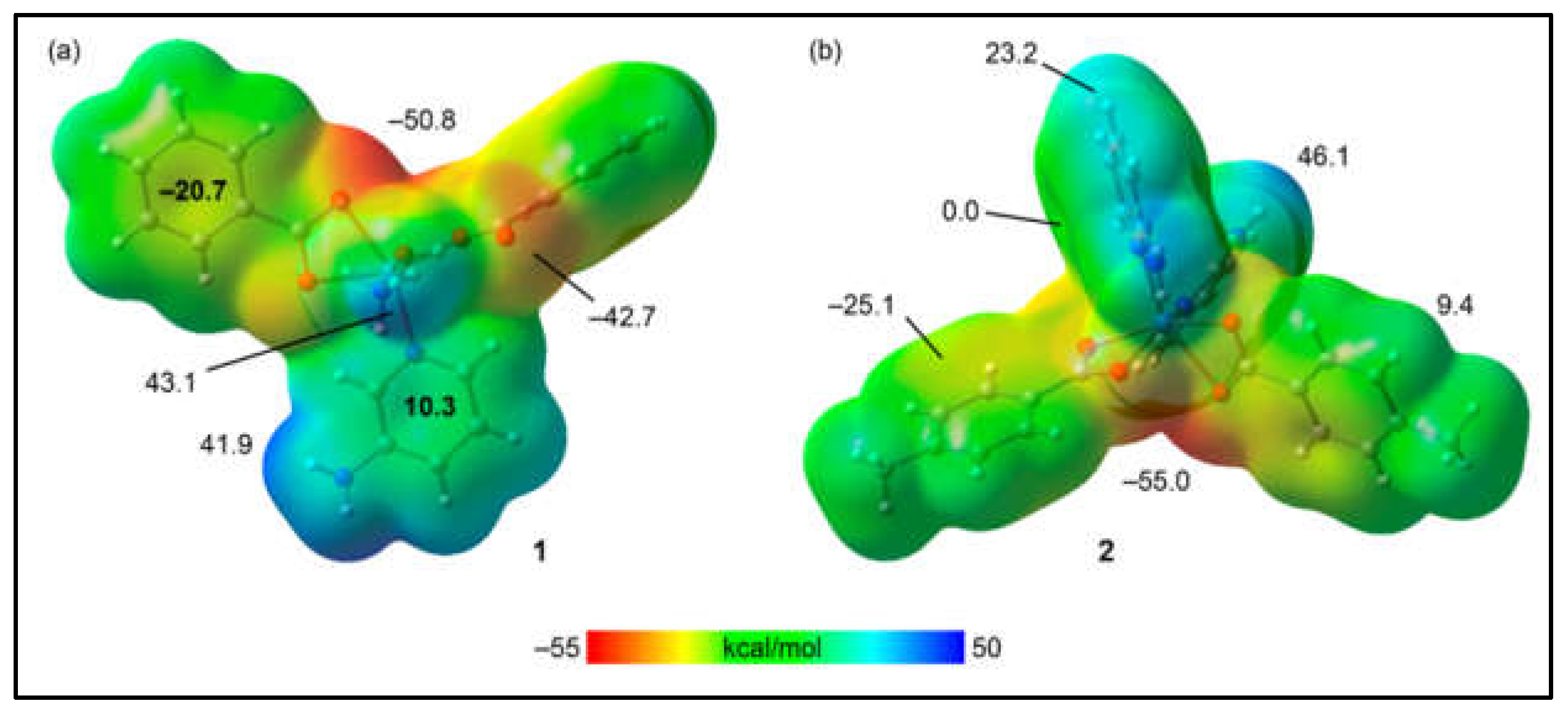

The theoretical investigation began by calculating the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces for models of compounds

1 and

2 to identify their nucleophilic and electrophilic regions. For the model of compound

1, as shown in

Figure 10a, the MEP analysis reveals the MEP minimum near two oxygen atoms of the benzoate ligands at –50.8 kcal/mol, indicating a nucleophilic region. Additionally, a negative MEP value is observed at the oxygen atoms involved in the intramolecular hydrogen bond with the coordinated water molecule, registering at –42.7 kcal/mol. The MEP maximum, indicative of an electrophilic region, is found at the hydrogen atom of the coordinated water molecule not participating in the intramolecular hydrogen bond, with a value of 43.1 kcal/mol. The MEP is also significantly positive at the amino group of the 3-Ampy ligand. Notably, the MEP shows a negative value over the center of the benzoate's aromatic ring and a positive value over the 3-Ampy's center, suggesting the propensity of these rings to engage in electrostatically enhanced π-stacking interactions. For compound

2, as illustrated in

Figure 10b, the MEP minimum is located at the oxygen atoms of the 4-Mebz ligand, with a value of –55.0 kcal/mol, and the MEP maximum at the amino groups of 2-Ampy, with a value of 46.1 kcal/mol. The MEP is negative over the center of the 4-Mebz aromatic ring, at –25.1 kcal/mol, and negligible over the center of 2-Ampy. Positive MEP values are observed at the aromatic hydrogen atoms of both 2-Ampy and 4-Mebz, at 23.2 kcal/mol and 9.4 kcal/mol, respectively, elucidating the role of C–H···π interactions in conjunction with hydrogen bonding between the amino and carboxylato groups in stabilizing the structure of compound

2.

Figure 10.

MEP surfaces of compounds 1 (a) and 2 (b). The MEP values at selected points of the surfaces are given in kcal/mol. Isovalue 0.001 a.u.

Figure 10.

MEP surfaces of compounds 1 (a) and 2 (b). The MEP values at selected points of the surfaces are given in kcal/mol. Isovalue 0.001 a.u.

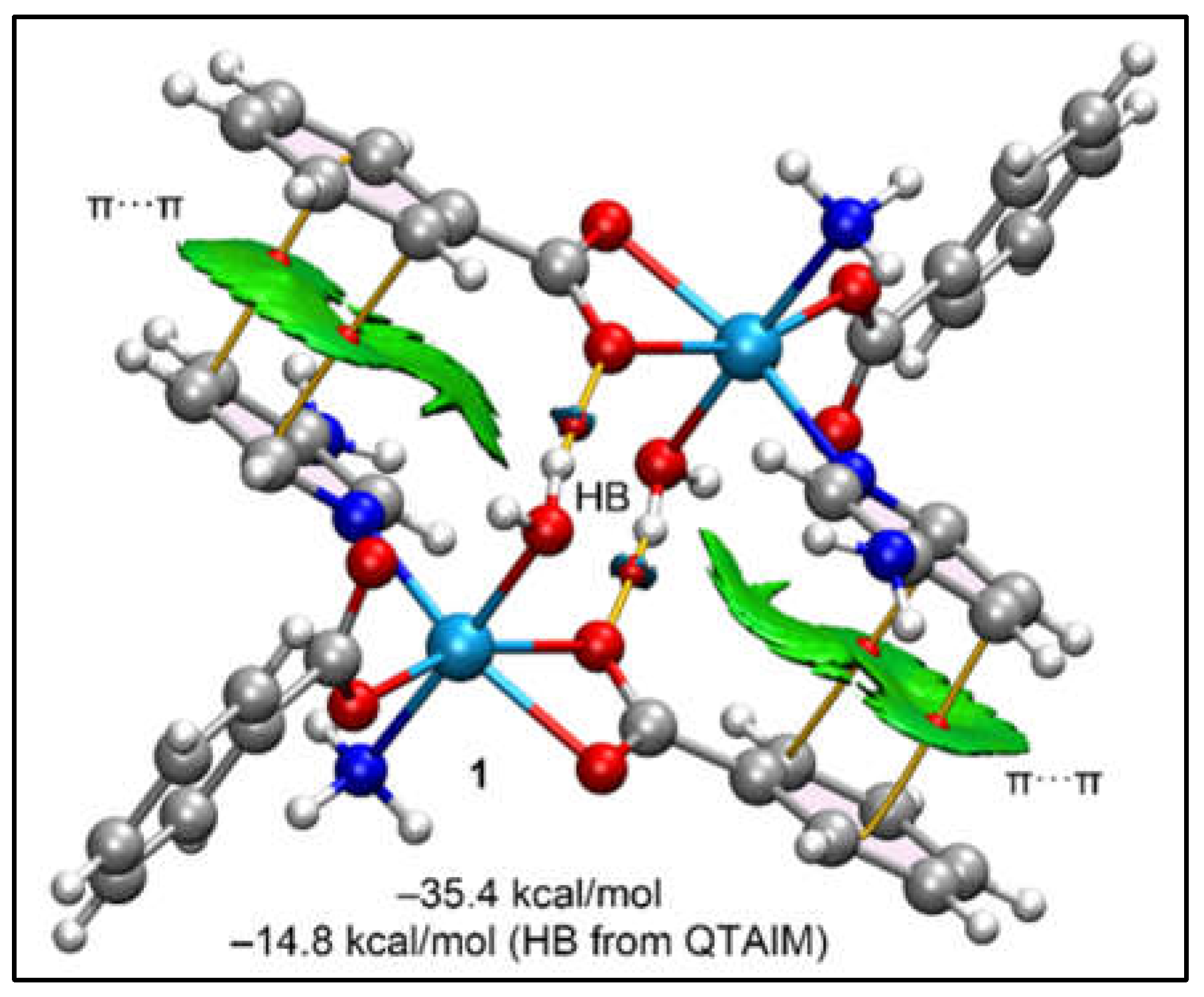

The QTAIM/NCI plot analysis of a self-assembled dimer of the model for compound

1 (

Figure 4a), designed to replicate the interactions seen in the self-assembly of the 1D polymeric chains, is illustrated in

Figure 11. This analysis shows that each π-stacking interaction is characterized by two bond critical points (BCPs, depicted as small red spheres) and bond paths (represented by orange lines) that connect two carbon atoms from the benzoate and 3-Ampy rings. The strong compatibility between the two rings is further underscored by a significant "reduced density gradient" (RDG) isosurface situated between them, corroborating the MEP surface analysis which indicated the strong ability to form π···π stacking due to the opposite electronic nature of the π-systems (one being electron-rich and the other electron-poor). Furthermore, the NCI plot analysis reveals two symmetrically equivalent BCPs and bond paths that characterize the O–H···O hydrogen bonds, each marked by blue RDG isosurfaces that signify the strength of these bonds. The robustness of these hydrogen bonds is verified by the QTAIM parameters, with a calculated strength of –14.8 kcal/mol. The total interaction energy, amounting to –35.4 kcal/mol, affirms the predominance of the π-stacking interactions, which are found to be even more significant than the hydrogen bonds in stabilizing the assembly.

Figure 11.

QTAIM (BCPs in red and bond paths as orange lines) and NCI plot of the dimeric assembly of compound 1 (RDG = 0.5, density cut-off = 0.04, colour range –0.04 a.u. ≤ (signλ2)ρ ≤ 0.04 a.u. The dimerization energy is indicated. The contribution of the H-bonds has been computed using the formula E = 0.5Vg, where Vg is the potential energy density.

Figure 11.

QTAIM (BCPs in red and bond paths as orange lines) and NCI plot of the dimeric assembly of compound 1 (RDG = 0.5, density cut-off = 0.04, colour range –0.04 a.u. ≤ (signλ2)ρ ≤ 0.04 a.u. The dimerization energy is indicated. The contribution of the H-bonds has been computed using the formula E = 0.5Vg, where Vg is the potential energy density.

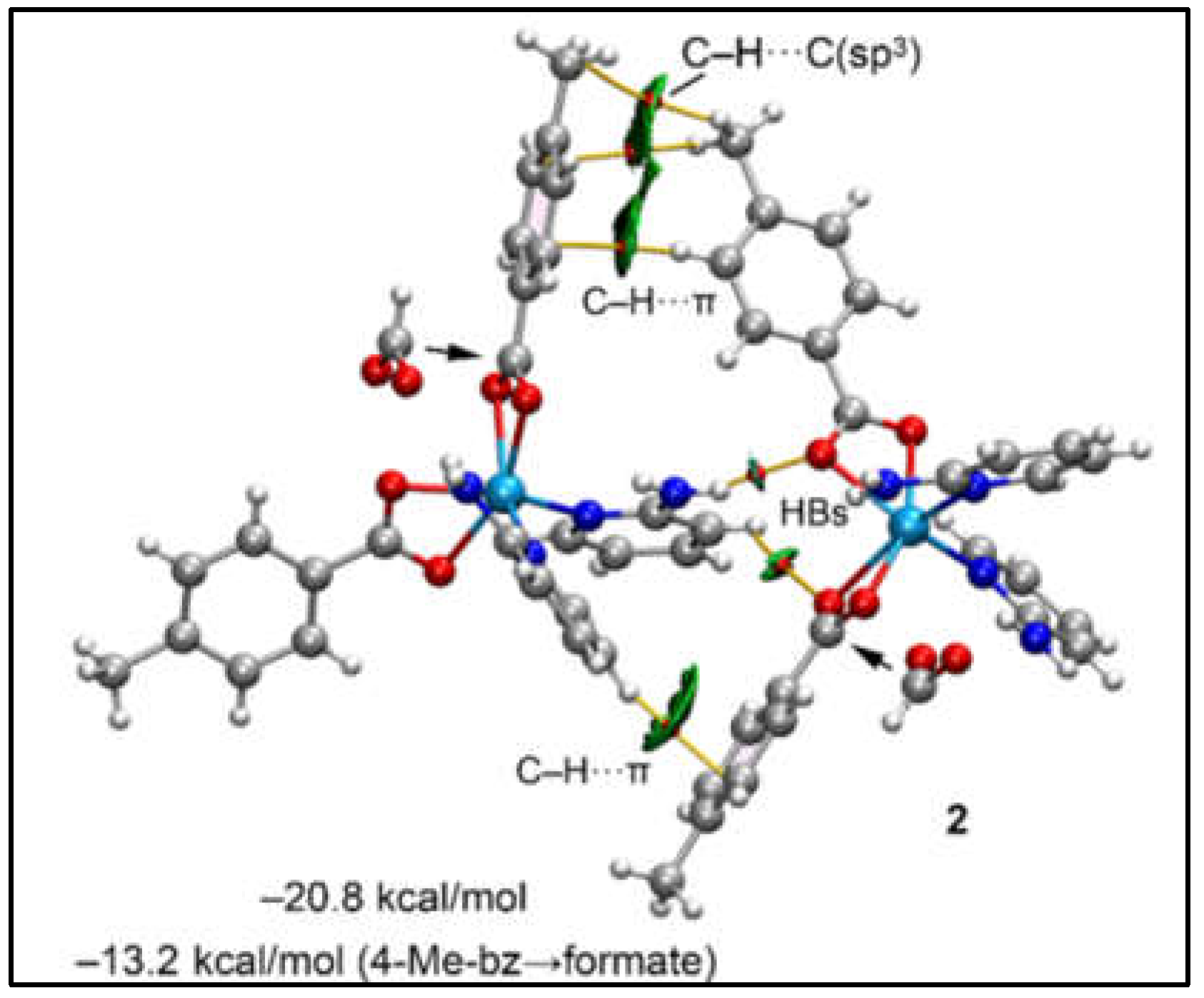

Figure 12 illustrates the dimer of compound

2, utilized to analyse and assess the N–H···O and C–H···π interactions highlighted in

Figure 8a. The QTAIM analysis substantiates the presence of N–H···O, C–H···O, and C–H···π interactions through the identification of their respective bond critical points (BCPs) and bond paths. Specifically, the C–H···π interaction between the 2-Ampy and the 4-Mebz rings is marked by a unique BCP and a bond path that links the hydrogen atom of 2-Ampy to a carbon atom of the 4-Mebz ring. This C–H···π interaction is more distinctly visualized with the RDG surfaces, which encapsulate the entire π-system. Additionally, the interaction involving the 4-Mebz ring showcases two BCPs and bond paths, incorporating the methyl group, with one BCP linking the hydrogen atom of one methyl group to the carbon atom of an adjacent methyl group, thus revealing the role of C–H···C(sp

3) interactions alongside two C–H···C(sp

2) contacts. The total interaction energy of –20.8 kcal/mol underscores the significance of this dimer in the solid-state structure of compound

2.

Figure 12.

QTAIM (BCPs in red and bond paths as orange lines) and NCI plot of the dimeric assembly of compound 2 (RDG = 0.5, density cut-off = 0.04, colour range –0.04 a.u. ≤ (signλ2)ρ ≤ 0.04 a.u. The dimerization energy for the complete assembly and the mutated one is indicated.

Figure 12.

QTAIM (BCPs in red and bond paths as orange lines) and NCI plot of the dimeric assembly of compound 2 (RDG = 0.5, density cut-off = 0.04, colour range –0.04 a.u. ≤ (signλ2)ρ ≤ 0.04 a.u. The dimerization energy for the complete assembly and the mutated one is indicated.

To dissect the contribution of C–H···π interactions, a modified dimer was computed, wherein the 4-Mebz ligands engaged in these interactions were substituted with formate ligands, thereby eliminating the C–H···π interactions. This alteration led to a reduced interaction energy of –13.2 kcal/mol, attributed to the hydrogen bonds. The difference with respect to the total interaction energy, amounting to -7.6 kcal/mol, is ascribed to the C–H···π interactions. Consequently, it is demonstrated that both hydrogen bonding (HBs) and C–H···π interactions are pivotal in stabilizing the dimeric assemblies. Thus, the theoretical study provides an interesting insight into the supramolecular dimers obtained in the crystal structure analysis of compounds 1 and 2.

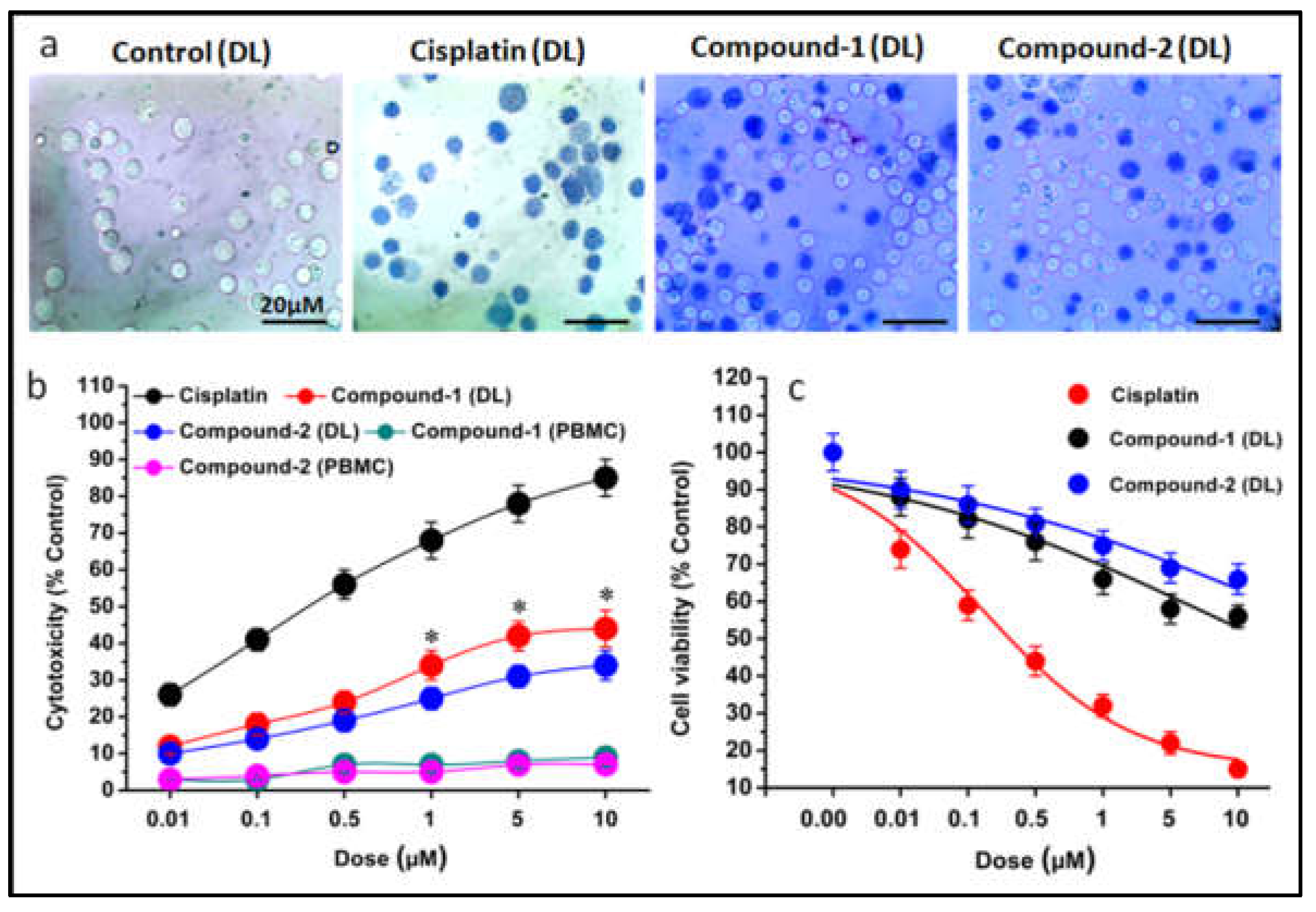

2.6. Trypan Blue Assay

The Trypan Blue assay serves as a crucial tool in anticancer research, based on its ability to assess cell viability through selective staining of non-viable cells. In this context, cancer researchers employ the assay to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of potential anticancer agents on cultured cells [

79]. When cells undergo apoptosis or necrosis upon treatment, their compromised membranes allow Trypan Blue dye entry, staining them. Viable cells, with intact membranes, exclude the dye. Quantifying the number of stained (non-viable) cells provides researchers with insights into the effectiveness of anticancer treatments, facilitating the assessment of cell death induction and overall treatment impact [

80]. In this cytotoxic study of both the compounds, Trypan Blue assay was employed to assess cell viability in the DL cancer cell line.

The results demonstrated a significant dose-dependent increase in cytotoxicity/ decrease in cell viability after a 48-hour period (

Figure 13a–c). Within the context of the Trypan Blue cytotoxicity assay, these findings offer critical insights into the impact of specific treatments on cell morphology and integrity (

Figure 13). The untreated control group (

Figure 13a) exhibited typical morphology under microscopic examination, with cells appearing round and showing no apparent membrane abnormalities, establishing a baseline for comparison. In contrast, the treated group displayed noticeable changes in cellular morphology under high magnification. Trypan Blue staining revealed two distinct alterations: chromatin condensation and membrane damage. Chromatin condensation, characterized by the compacting of genetic material within the nucleus, is commonly associated with processes like apoptosis or programmed cell death [

81,

82]. The detection of membrane damage points to structural compromise, likely induced by the cytotoxic impact of the treatment. These morphological alterations, as evidenced by the Trypan Blue assay, visually affirm the detrimental effects of the treatment on the cells under investigation.

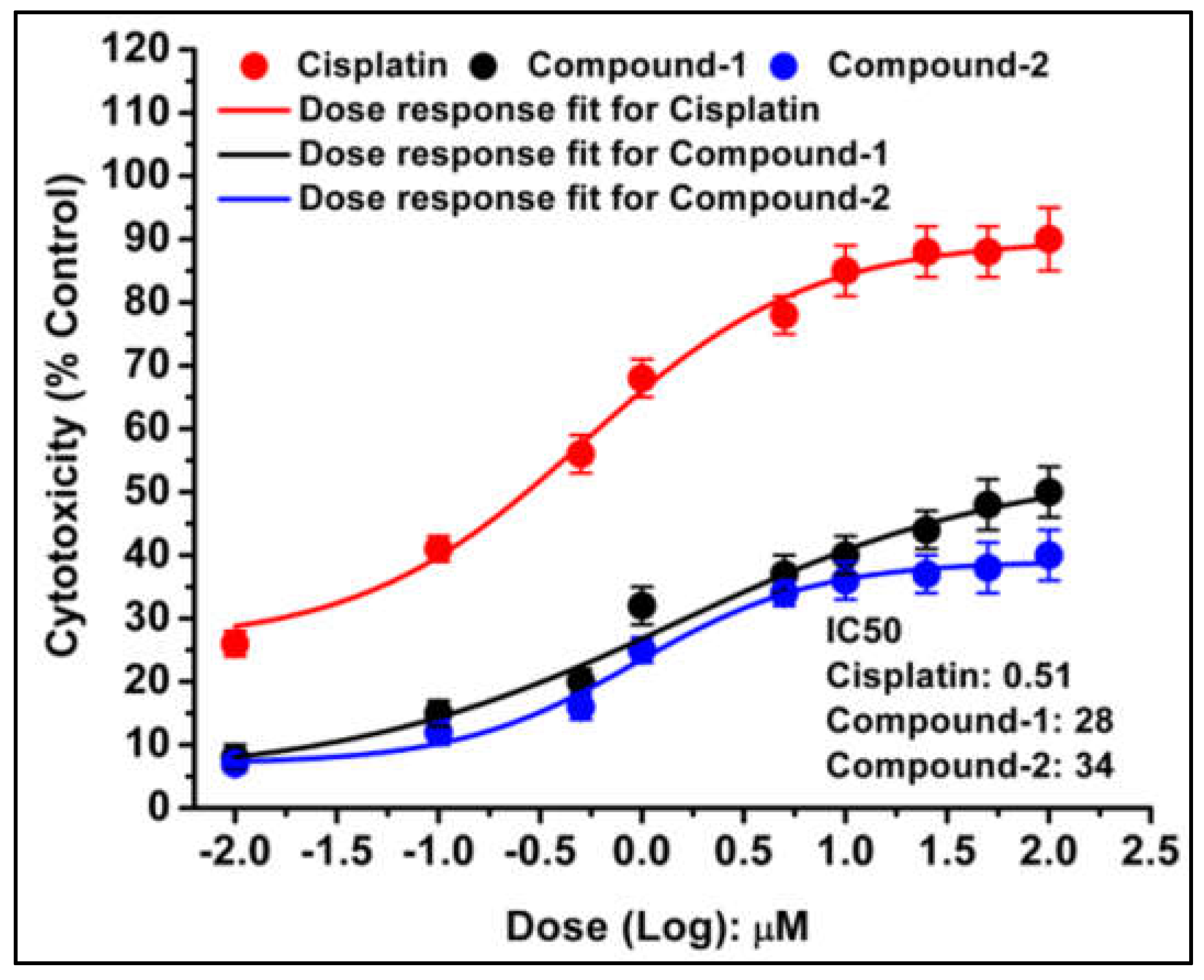

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) values highlighted the potency of the compounds in DL cell line (

Figure 14). The IC

50 values for cisplatin, compound

1, and compound

2 were determined as 0.51 μM, 28 μM, and 34 μM, respectively. This underscores not only the potent cytotoxicity of the tested compounds but also positions them as compelling candidates for further investigation as lead molecules in cancer treatment and research strategies. Comparative analysis showcases higher cytotoxicity of compound

1 over compound

2 in DL cancer cell line. In contrast, minimal cytotoxicity (4-6%) was observed in the normal cell line (PBMC) treated with these compounds, and this difference was found to be statistically non-significant (

Figure 13b). This selective cytotoxicity, sparing normal cells while targeting cancerous ones, represents a promising characteristic for potential therapeutic applications. Furthermore, the free ligand associated with these compounds did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity in the DL cancer cell line (data not shown). This result suggests that the observed cytotoxic effects are predominantly due to the complexes themselves rather than their individual ligands.

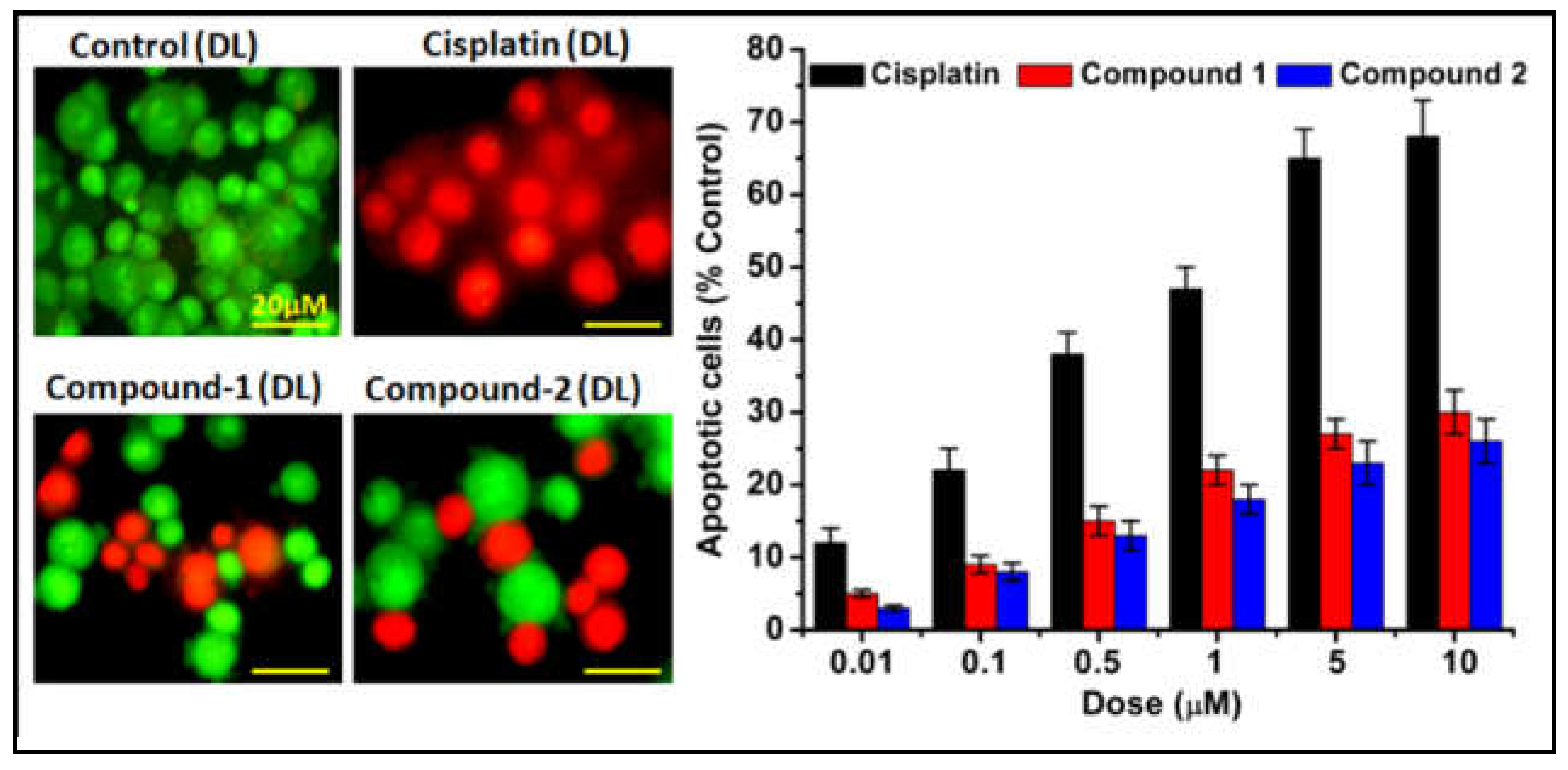

2.7. Apoptosis Assay

To gain deeper insights into the cytotoxic mechanisms of the compounds, an apoptosis study was conducted. This investigation focuses on understanding the biological processes that regulate cell growth and proliferation. Apoptosis, characterized by changes in cell morphology such as increased membrane permeability to ethidium bromide resulting in red staining, contrasts with viable cells that appear green [

83,

84]. Treatment of DL cells with the synthesized compounds induced apoptotic features, including cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, membrane fragmentation, and nuclear condensation (

Figure 15). Cisplatin was used as a reference drug due to its ability to exert cytotoxic effects by inducing DNA damage through the formation of DNA adducts, ultimately leading to irreversible apoptosis. DNA damage recognition proteins play a crucial role in transmitting signals of DNA damage to downstream signaling pathways involving p53, MAPK, and p73, which orchestrate the induction of apoptosis [

85]. Moreover, the findings of several other studies indicated that most of the synthesized complexes had anticancer activity due to the development of a stable DNA adduct and apoptosis [

86]. Again, cancer cells have a higher oxidative stress than the normal cells and therefore suffer more oxidative DNA/protein damage [

87]. Oxidative stress is a physiological condition characterized by elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals. Various signaling pathways involved in carcinogenesis can influence ROS production and regulate downstream oxidative mechanisms, potentially impacting anticancer research [

87]. In the comparative analysis of apoptotic cell death, it was observed that compound 1 exhibited greater cytotoxicity and apoptosis-inducing capabilities than compound 2 after 48 hours of exposure (

Figure 15).

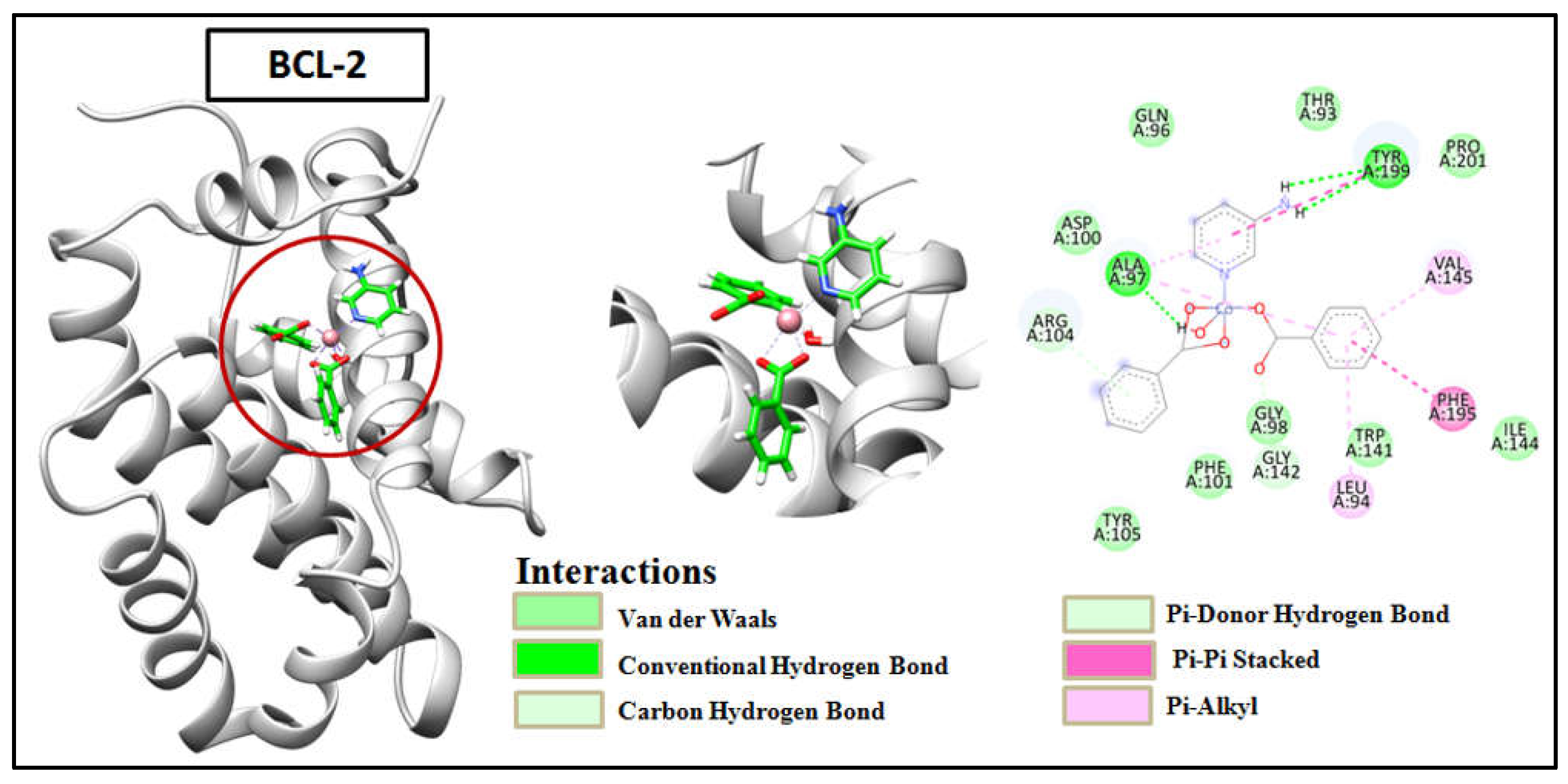

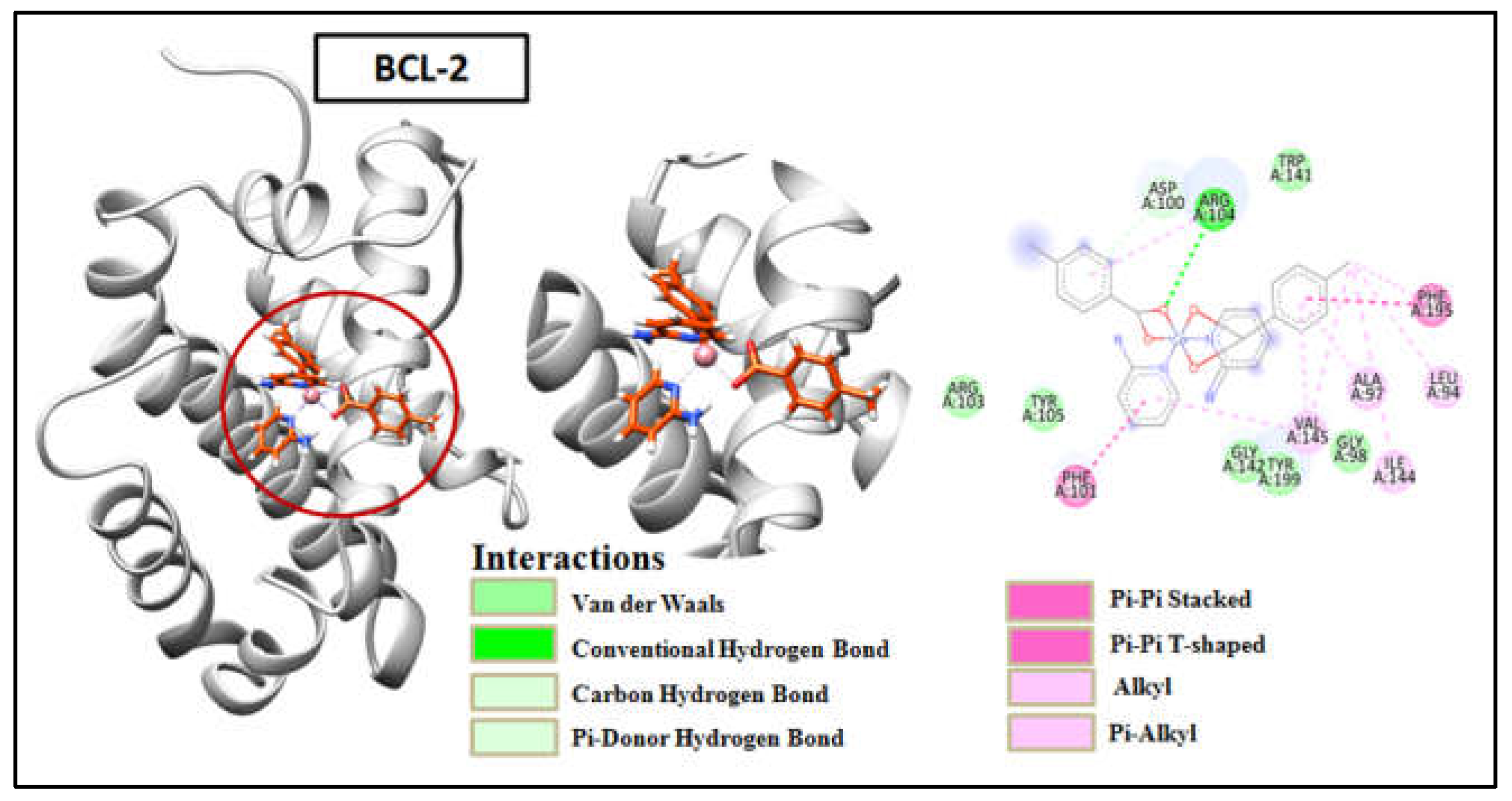

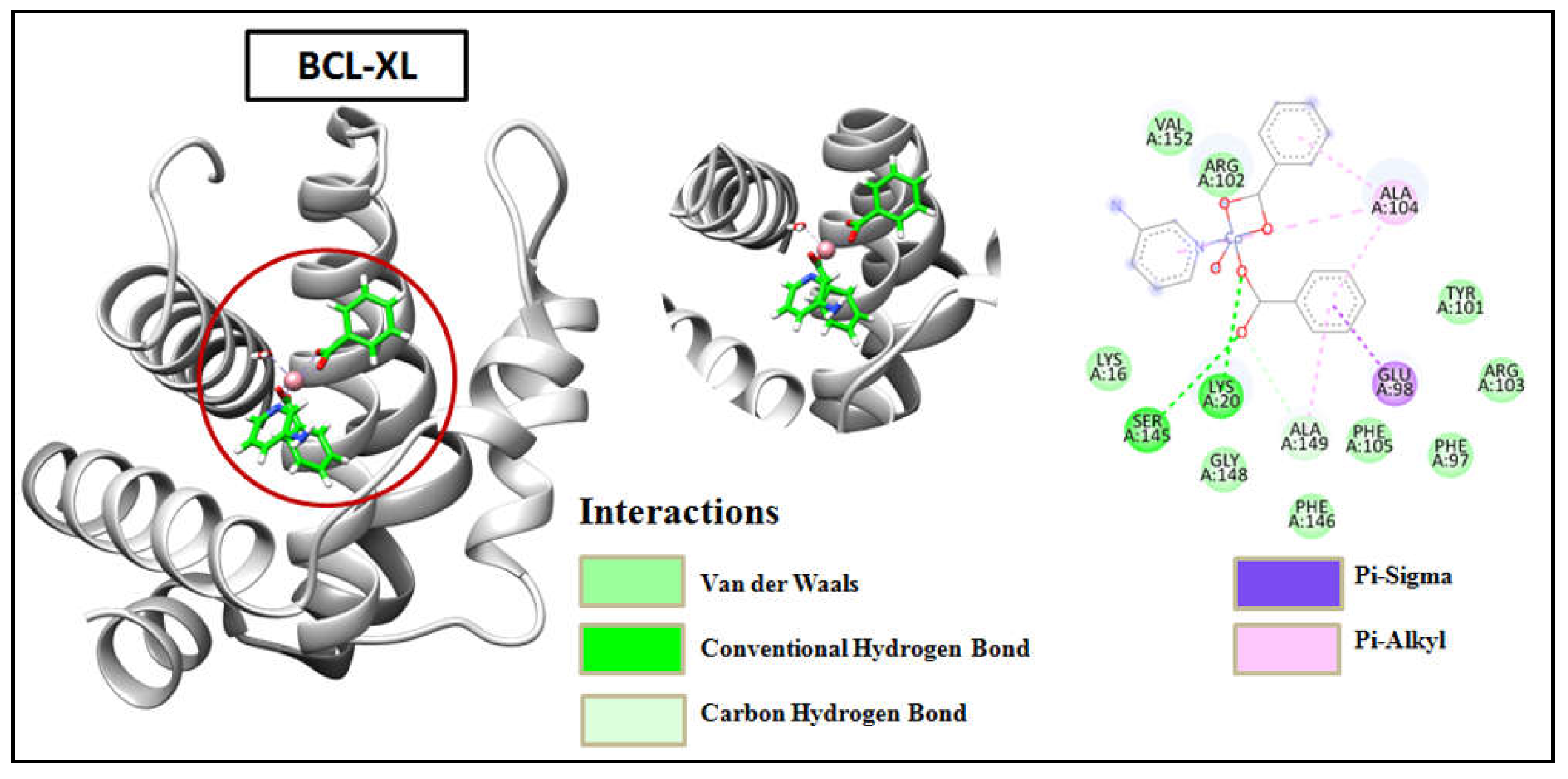

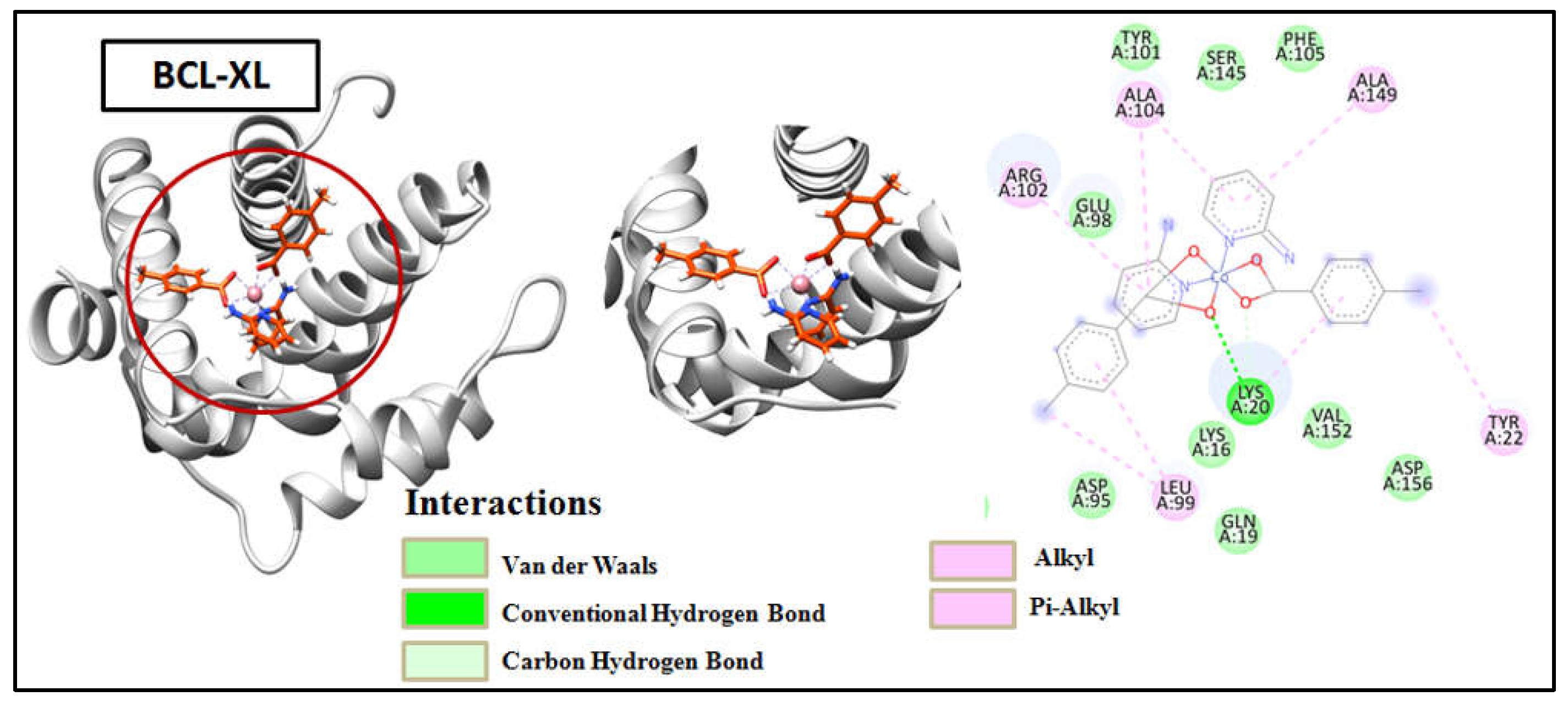

2.8. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking has emerged as an effective drug design method for determining the potency of drugs against specific target proteins [

88]. It is possible to explore the binding affinities and interaction modes between compounds and the binding pocket of target proteins based on energy-based scoring functions [

89]. It aids to rationalize the biological results obtained and identifies the binding mode of the ligands with their receptors [

90]. The target proteins BCL-2 and BCL-XL play important roles in regulating programmed cell death that are over-expressed in a variety of human cancers so targeting their evasion by their selective inhibition would offer effective therapeutic opportunities for cancer treatment [

91]. Therefore, BCL-2 and BCL-XL were chosen as target proteins for docking with the synthetic compounds. The results exhibited significant docking scores which validated the findings of biological activity of the compounds. The chemical interaction analysis suggested that the ligand-receptor complexes were effectively stabilized by specific hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions (

Table S1). Compound 1 was found to interact with active sites of amino acid such as Ala97 and Tyr199 of BCL-2 by three conventional H-bonds besides other hydrophobic and aromatic stacking interactions with the protein (

Figure 16). It suggested that compound 1 revealed higher binding affinity as compared to the other compound due to the presence of extra H-bonds, as compound 2 showed only one hydrogen bond interaction with amino acid Arg104 (

Figure 17). Compound 1 (

Figure 18) showed two H-bond with Lys20 and Ser145 of BCL-XL whereas compound 2 interacted only with Lys20 of BCL-XL via one H-bond besides other interactions of different bond types (

Figure 19). The results obtained from docking revealed that the synthetic compounds binds effectively well with high binding affinities with BCL-2 and BCL-XL where compound 1 excels over compound 2. The above docking study was consistent with the findings obtained from the biological activity screening experiments including cell viability and apoptosis studies. The results of molecular docking, along with the evidence from the biological studies, indicate that the compounds might play significant roles as potential inhibitors of BCL-2 and BCL-XL.

3. Materials and Methods

All the chemicals viz. cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate, benzoic acid, 3-aminopyridine, 2-aminopyridine and 4-methyl benzoic acid that are readily available commercially are employed in the current research work. Perkin Elmer 2400 Series II CHN analyzer was used for elemental analysis (C, H, N). The FT-IR spectra from 500 to 4000 cm-1 were measured using KBr pellets with a Bruker Alpha Infrared spectrophotometer. Electronic spectra were recorded using Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. For solid state spectra, BaSO4 powder was used as reference (100% reflectance). Thermogravimetric analysis was carried out from 25 to 800°C (at a heating rate of 10 °C/min) under a dinitrogen atmosphere on a Mettler Toledo TGA/DSC1 STARe system. Room temperature magnetic moments of the synthesized compounds were calculated at 300 K using Sherwood Mark1 Magnetic Susceptibility balance by Evans method.

3.1. Syntheses

3.1.1. Synthesis of [Co(H2O)(bz)2(μ-3-Ampy)2]n (1)

The compound

1 was prepared by dissolving 0.288g (2 mmol) of sodium salt of benzoic acid in 10 mL of distilled water, to which an aqueous solution (5 mL) of 0.237g (1 mmol) of CoCl

2·6H

2O was added with continuous stirring and then left at room temperature for an hour. To the resulting solution an aqueous solution (5 mL) of 0.188g (2 mmol) of 3-Ampy was added slowly and the mixture kept stirring for another one hour (

Scheme 1). The resulting pink solution was left undisturbed, and pink block shaped single crystals were obtained after few weeks by slow solvent evaporation in a refrigerator below 4°C. Yield: 0.404 g (97.82%). Anal. calcd. For C

19H

18CoN

2O

5: C, 55.22%; H, 4.39%; N, 6.78%; Found: C, 54.87%; H, 4.23%; N, 6.50%. IR (KBr pellet, cm

-1): 3432 (br), 3348 (w), 3251 (sh), 2939 (w), 1899 (w), 1617 (sh), 1605 (s), 1539 (s), 1515 (sh), 1437 (sh), 1429 (s),1381 (s),1335 (w), 1265 (m), 1171 (w), 982 (m), 720 (sh), 716 (s), 685 (m), 655 (w), 640 (w), 552 (sh) (s, strong; m, medium; w, weak; br, broad; sh, shoulder).

3.1.2. Synthesis of [Co(4-Mebz)2(2-Ampy)2] (2)

The compound

2 was prepared by dissolving 0.237g (1 mmol) of CoCl

2·6H

2O in 10 mL of distilled water, to which an aqueous solution (5 mL) of 0.300g (2mmol) of sodium salt of 4-methyl benzoic acid was added with continuous stirring and then left at room temperature for an hour. To the resulting solution an aqueous solution (5 mL) of 0.188g (2 mmol) of 2-Ampy was added slowly and the mixture kept stirring for another one hour (

Scheme 1). Under quiescent conditions, the resulting solution was allowed to undergo slow solvent evaporation in a refrigerator maintained below 4°C, yielding light pink block-shaped single crystals after several weeks. Yield: 0.500 (96.71%). Anal. calcd. for C

26H

26CoN

4O

4: C, 60.35%; H, 5.06%; N, 10.83% Found: C, 60.30%; H, 5.00%; N, 10.79%; IR (KBr pellet, cm

-1): 3423 (br), 1914 (w), 1616 (sh), 1593 (s), 1514 (sh), 1437 (sh), 1399 (s), 1340 (w),1225 (s), 1022 (s), 818 (m), 716 (m), 655 (w), 513 (m) (s, strong; m, medium; w, weak; br, broad; sh, Shoulder).

3.2. Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement

D8 Venture diffractometer was used to determine the structures of the compounds

1 and

2, with a Photon III 14 detector, utilizing an Incoatec high brilliance IμS DIAMOND Cu tube equipped having an Incoatec Helios MX multilayer optics. Data reduction and cell refinements were performed using the Bruker APEX3 program [

92]. SADABS is used for semi-empirical absorption correction, as well as scaling and merging the different datasets for the wavelength [

92]. Crystal structures were solved via direct method and refined via full matrix least squares technique with SHELXL-2018/3 [

93] using WinGX [

94] platform for personal computers. Refinement of all the non-hydrogen atoms were carried out with anisotropic thermal parameters by full-matrix least squares calculations on F2. All hydrogen atoms, except those attached to O-atoms of water molecules, were placed in ideal positions and refined in the isotropic approximation. Diamond 3.2 software was used for drawing the figures [

95]. Crystallographic data of the compounds

1 and

2 are summarized in

Table 3 with CCDC deposition numbers cited in

Appendix A.

3.3. Computational Methods

The single point calculations were carried out using the Turbomole 7.7 program [

96] and the RI-BPE0[

97]-D4[

98]/def2-TZVP [

99] level of theory. The crystallographic coordinates have been used to evaluate the interactions in compounds

1 and

2 since we are interested to study the noncovalent contacts as they stand in the solid state. High spin configuration was used for Co(II). The Bader's “Atoms in molecules” theory (QTAIM) [

100] and noncovalent interaction plot (NCI Plot) [

101] were used to study the interactions discussed herein using the Multiwfn program [

102] and represented using the VMD visualization software [

103]. For the calculation of the binding energies we used the supramolecular approach, where the sum of energies of the monomers was subtracted to the energy of the assembly. For the representation of the MEP surface, the 0.001 a.u. isosurface was used to emulate the van der Waals surface.

3.4. Cell line and Drug Preparation

The anticancer potential of both the compounds were tested in Dalton’s lymphoma (DL) malignant cell line. The DL cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, gentamycin (20 mg/mL-1), streptomycin (100 mg/mL-1) and penicillin (100 IU) in a CO2 incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2; 80% confluent of exponentially growing cells were sub-cultured and used in the present study. The different doses (0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 and 10 μM) of 1 and 2 were prepared by dissolving in conditioned media (pH = 7.4). PBMCs were used in the present study as healthy cells (non-cancerous) to check any toxic effect of synthesized complexes.

3.5. Trypan Blue Cytotoxicity Assay

In this assay, cells were stained with Trypan blue, a dye that selectively penetrates and colors non-viable cells (dead cells) with compromised cell membranes [

104]. To assess the antiproliferative and cytotoxic potential of the cobalt complex and its associated ligand, a Trypan blue exclusion experiment was conducted using DL (cancer) and PBMC (normal) cell lines [

105]. Following 48 hours of in vitro treatment in appropriate culture media, cells were stained with trypan blue dye (4%) for 3 minutes. Subsequently, 1000 cells were counted across multiple fields of view for each experimental group (n = 3) to determine the percentage of cytotoxicity compared to the control.

The following is the non-linear curve fitting function used to get the IC

50:

(Where, A1 = bottom asymptote, A2 = top asymptote, LOGx0 = center and p = hill slope).

Regarding the said free ligands, the observed cytotoxicity was found to be less than 6%, a value that did not reach statistical significance.

3.6. Apoptosis Study

Apoptotic cell death mediated by compounds

1 and

2 was assessed using the acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) double staining method. AO is taken up by both viable and apoptotic cells, emitting green fluorescence under UV light, while EB is taken up only by apoptotic cells, emitting red fluorescence [

106]. In this study, control and treated cancer cells were collected after 48 hours of treatment, washed with PBS, and 20 μL of the AO/EB dye mixture (100 μg/mL of each dye in distilled water) was added to the cell suspension. The mixture was gently mixed and incubated in the dark for 5 minutes. The cells were then thoroughly examined under a fluorescence microscope and photographed. Approximately 1000 cells were analyzed, and the percentage of apoptotic nuclei was determined based on the differential staining pattern of the nuclei in three independent experiments. Viable cells exhibited bright, uniform green nuclei with organized structures, whereas apoptotic cells displayed condensed or fragmented chromatin with red or orange nuclei [

107].

3.7. Molecular Docking Simulation

The results obtained from cell cytotoxicity and apoptosis studies were validated by carrying out molecular docking simulation using fully functional Molegro Virtual Docker (Trial MVD 2010.4.0) software. Anti-apoptotic proteins considered for the study were BCL-2 (PDB: 2O22) and BCL-XL (PDB: 1R2D) and their crystal structures were downloaded from Protein Data Bank. All co-factors and water molecules were removed before running the simulation program. MVD algorithm (MVD 2010 V-3) by default assigns charges to both receptors and ligands during the molecule preparation step. The docking settings used were a 15 Å radius grid, 0.30 in resolution with the number of runs: 10 runs; maximum interactions: 1500; maximum population size: 50; maximum steps: 300; neighbour distance factor: 1.00 and with a maximum of 5 poses returned. The best pose generated was visualized using Discovery Studio Visualization BIOVIA and Chimera software.

3.8. Statistical Analysis

The experimental findings are showcased as mean ± S.D., n = 3 (all measurements done thrice). by An analysis of variance (ANOVA) (*P ≤ 0.05) were used for data analysis, followed by Post hoc, Tukey’s range test wherever necessary.

4. Conclusions

Two new Co(II) coordination compounds viz. polynuclear [Co(H2O)(bz)2(μ-3-Ampy)2]n (1) and mononuclear [Co(4-Mebz)2(2-Ampy)2] (2) (where bz = benzoate, 4-Mebz = 4-methylbenzoate and Ampy = aminopyridine) have been synthesized and characterized using single crystal X-ray diffraction technique, FT-IR, electronic spectroscopy, TGA and elemental analyses. Crystal structure analysis of compound 1 reveals the presence of aromatic π-stacking and intramolecular chelate ring∙∙∙π interactions in combination with several hydrogen bonding interactions, including a synthon, which stabilize the crystal structure. The layered assembly of compound 2 is stabilized by C–H∙∙∙π interactions along with C‒H∙∙∙O, N‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonds forming another Etter’s ring. The studies on compounds 1 and 2 utilizing QTAIM/NCI plot and MEP analyses have elucidated the importance of noncovalent interactions, such as π-stacking, hydrogen bonding (especially the synthons) and C–H···π interactions, that dictate their solid-state structures. For compound 1, π-stacking and O–H···O hydrogen bonds are key to its layered architecture, with MEP analysis highlighting the electronic complementarity between involved rings. In compound 2, the balance of N–H···O and C–H···π interactions, confirmed through QTAIM analysis and a strategic dimer modification, demonstrates that these interactions are important for the dimer's stability. Regarding their antiproliferative evaluation, present findings reveals that compound 1 demonstrated higher cytotoxicity with IC50 = 28 μM and apoptosis-inducing potential compared to compound 2 (IC50 = 34 μM) following a 48-hour exposure period. Remarkably, negligible toxicity was observed in the normal PBMC cell line for both the compounds. Further, in silico docking study for compound 1 showed higher number of interactions in comparison to compound 2 with both the BCL family proteins which aligns well with the experimental findings. These results underscore the promising therapeutic potential of compound 1 in targeted cancer treatments, highlighting its efficacy in inducing cell death specifically in cancerous cells while sparing normal cells. Future studies could focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms underlying both the compounds selective cytotoxicity and further exploring their clinical applications in cancer therapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: FT-IR spectra of compounds

1 and

2;

Figure S2: (a) UV-Vis-NIR spectrum of

1, (b) UV-Vis spectrum of

1;

Figure S3: (a) UV-Vis-NIR spectrum of

2, (b) UV-Vis spectrum of

2;

Figure S4: Thermogravimetric curves of the compounds

1 and

2; Table S1: Analysis of intermolecular interactions between antiapoptotic receptors and compounds

1 and

2. The reference ligands, obtained from the co-crystallized PDB entry files of the respective receptors, were used for comparison. Binding score values are reported in arbitrary units, with lower scores indicating stronger affinity as calculated by the software algorithm. Refs [

48,

68,

72,

73,

74] were cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F., A.K.V. and M.K.B.; methodology, A.F., A.K.V. and M.K.B.; software, A.F., R.M.G. and A.K.V.; formal analysis, A.F.; investigation, K.K.D.; T.B., J.D. and R.M.G.; data curation, M.B.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, K.K.D.; writing—review and editing, M.K.B.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, M.K.B.; project administration, A.F. and M.K.B.; funding acquisition, A.F. and M.K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial supports obtained from SERB-SURE (Grant number: SUR/2022/001262), the In-House Research Project (IHRP), Cotton University [Grant number: CU/Dean/R&D/2019/02/23], ASTEC, DST, Govt. of Assam [Grant number: ASTEC/S&T/192(177)/2020-2021/43)], and the Gobierno de Espana, MICIU/AEI (projects No. EQC2018-004265-P and PID2020-115637GB-I00) are gratefully acknowledged. K.K.D. thanks CSIR [09/1236(16497)/2023-EMR-I], Govt. of India for Junior Research Fellowship (JRF). The authors thank IIT, Guwahati for TG data.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

CCDC 2324863 and 2261047 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for the compounds

1 and

2. These data can be obtained free of charge at

http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: (+44) 1223-336-033; or E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk.

References

- Climova, A.; Pivovarova, E.; Rogalewicz, B.; Raducka, A.; Szczesio, M.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Korga-Plewko, A.; Iwan, M.; Gobis, K.; Czylkowska, A. New Coordination Compounds Based on a Pyrazine Derivative: Design, Characterization, and Biological Study. Molecules 2022, 27, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. -D.; Meng, F. -Q.; Shi, Y.-S.; Xiao, T.; Fang, Y.-H.; Tan, H.-W.; Zheng, X.-J. A Series of Zinc Coordination Compounds Showing Persistent Luminescence and Reversible Photochromic Properties via Charge Transfer. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellei, M.; Del Bello, F.; Porchia, M.; Santini, C. Zinc Coordination Complexes as Anticancer Agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 445, 214088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Z.; Khan, S.; Ullah, S.; Ullah, H.; Khan, M. U.; Ullah, M.; Altaf, A. A. Recent Development in Coordination Compounds as a Sensor for Cyanide Ions in Biological and Environmental Segments. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2024, 54, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yıldırım, A.; Aksoy, M. S. Homoleptic Pyrazinoic Acid Transition Metal Complex as an Efficient Catalyst toward Elegant Three-Component Synthesis of 3,4-Dihydro-2H-1,3-Benzoxazines. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 555, 121583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvarova, M. A.; Lutsenko, I. A.; Babeshkin, K. A.; Sokolov, A. V.; Alexandrov, E. V.; Efimov, N. N.; Shmelev, M. A.; Khoroshilov, A. V.; Eremenko, I. L.; Kiskin, M. A. Solvent Effect in the Chemical Design of Coordination Polymers of Various Topologies with Co2+ and Ni2+ Ions and 2-Furoate Anions. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 6786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateshali, K.; Farahmand, A.; Gholizadeh Dogaheh, S.; Soleimannejad, J.; Blake, A. J. Structural Diversity and Applications of Ce(III)-Based Coordination Polymers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 419, 213392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, V.; Esmaeili, M.; Norouzi, F.; Khavasi, H. R. A Strategy for Obtaining Isostructurality Despite Structural Diversity in Coordination Compounds. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.-Y.; Li, X.-X.; Du, M.-X.; Dong, W.-K.; Ding, Y.-J. Deep Insights into Novel Hexa-Coordinated Phenoxy-Bridged Trinuclear Ni(II) Asymmetric Salamo-like Complexes Affected by Different Types of Combined Solvents. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1298, 137071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilescu, O.; Bulhac, I.; Shova, S.; Novitchi, G.; Bourosh, P. Coordination Compounds of Copper(II) with Schiff Bases Based on Aromatic Carbonyl Compounds and Hydrazides of Carboxylic Acids: Synthesis, Structures, and Properties. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2020, 46, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wan, S.; Kirillova, M. V.; Kirillov, A. M. H-Bonded and Metal(II)–Organic Architectures Assembled from an Unexplored Aromatic Tricarboxylic Acid: Structural Variety and Functional Properties. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boruah, R.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Dutta Purkayastha, R. N.; Modak, S.; Aktar, T.; Maiti, D.; Sieroń, L.; Maniukiewicz, W.; Gomila, R. M.; Frontera, A. Insights into Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Bioactivity and Computational Studies of Cu(II) and Zn(II) Carboxylates Containing Aminopyridine. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202204937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, N.; Rashid, F.; Haider, A.; Tirmizi, S. A.; Raheel, A.; Imran, M.; Zaib, S.; Diaconescu, P. L.; Iqbal, J.; Ali, S. Triorganotin(IV) Carboxylates as Potential Anticancer Agents: Their Synthesis, Physiochemical Characterization, and Cytotoxic Activity against HeLa and MCF-7 Cancer Cells. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, e6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, S.; Ghadermazi, M.; Aliabadi, A. Study on Electrochemical Behavior and In Vitro Anticancer Effect of Co(II) and Zn(II) Complexes Containing Pyridine-2,6-Dicarboxylate. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 527, 120549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štarha, P.; Křikavová, R. Platinum(IV) and Platinum(II) Anticancer Complexes with Biologically Active Releasable Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 501, 215578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhoshani, A.; Sulaiman, A. A.; Sobeai, H. M. A.; Qamar, W.; Alotaibi, M.; Alhazzani, K.; Monim-ul-Mehboob, M.; Ahmad, S.; Isab, A. A. Anticancer Activity and Apoptosis Induction of Gold(III) Complexes Containing 2,2′-Bipyridine-3,3′-Dicarboxylic Acid and Dithiocarbamates. Molecules 2021, 26, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, F. A.; Jantscher, P. V.; Fischer, R. C.; Torvisco, A.; Reichmann, K.; Massoud, S. S. Syntheses, Structural Characterization, and Thermal Behaviour of Metal Complexes with 3-Aminopyridine as Co-Ligands. Transit. Met. Chem. 2021, 46, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtcan, S.; Yolcu, Z. 4-Aminopyridine Containing Metal-2,6-Pyridine Dicarboxylates and Complex Embedded Hydrogels: Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Applications. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2024, 563, 121918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautner, F. A.; Jantscher, P.; Fischer, R. C.; Torvisco, A.; Vicente, R.; Karsili, T. N. V.; Massoud, S. S. Synthesis and Characterization of 1D Coordination Polymers of Metal(II)-Dicyanamido Complexes. Polyhedron 2019, 166, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufanyi, D. M.; Nono, H. J.; Yuoh, A. C. B.; Tabong, C. D.; Judith, W.; Ondoh, A. M. Crystal Packing Studies, Thermal Properties, and Hirshfeld Surface Analysis in the Zn(II) Complex of 3-Aminopyridine with Thiocyanate as Co-Ligand. Open J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, Z.; Şahin, O.; Yavuz, A. The Synthesis of Two New Hofmann-Type M(3-Aminopyridine)2Ni(CN)4 [M = Zn(II) and Cd(II)] Complexes and the Characterization of Their Crystal Structure by Various Spectroscopic Methods. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1171, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddar, K.; Bouchoucha, A.; Bourouai, M. A.; Zaater, S.; Djebbar, S. Transition Metal Complexes of 2-Aminopyridine Derivatives as Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors: Stability, Spectral, and Thermal Characterization, Electrochemical Behavior, DFT Calculations, Molecular Docking, and Biological Activities. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2023, 93, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, W. H.; Mohamed, G. G.; El-Dessouky, M. M. I. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, In Vitro Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activity Studies of Ternary Metal Complexes Containing Glycine Amino Acid and the Anti-Inflammatory Drug Lornoxicam. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1082, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, V.; Anghel, N.; Desiatkina, O.; Felder, T.; Boubaker, G.; Amdouni, Y.; Ramseier, J.; Hungerbühler, M.; Kempf, C.; Heverhagen, J. T.; Hemphill, A.; Ruprecht, N.; Furrer, J.; Păunescu, E. Conjugates Containing Two and Three Trithiolato-Bridged Dinuclear Ruthenium(II)-Arene Units as In Vitro Antiparasitic and Anticancer Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M. S.; Khalid, M.; Khan, M. S.; Shahid, M.; Ahmad, M.; Saeed, H.; Owais, M.; Ashafaq, M. Tuning Biological Activity in Dinuclear Cu(II) Complexes Derived from Pyrazine Ligands: Structure, Magnetism, Catecholase, Antimicrobial, Antibiofilm, and Antibreast Cancer Activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Ali, S.; Tahir, M. N.; Shah, N. A. Dihydroxo-Bridged Dimeric Cu(II) System Containing Sandwiched Non-Coordinating Phenylacetate Anion: Crystal Structure, Spectroscopic, Antibacterial, Antifungal, and DNA-Binding Studies of [(Phen)(H2O)Cu(OH)2Cu(H2O)(Phen)]2L·6H2O (HL = Phenylacetic Acid; Phen = 1,10-Phenanthroline). J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1143, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Swiątkowski, M.; Lanka, S.; Czylkowska, A.; Gas, K.; Sawicki, M. Structural, Spectroscopic, Thermal, and Magnetic Properties of a New Dinuclear Copper Coordination Compound with Tiglic Acid. Materials 2021, 14, 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Das, D.; Ray, P. P.; Banerjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, S. Phenoxo-Bridged Dinuclear Mixed Valence Cobalt(III/II) Complexes with Reduced Schiff Base Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, Band Gap Measurements, and Fabrication of Schottky Barrier Diodes. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkar, A.; Nnabuike, G. G.; Obaleye, J. A.; Harihar, S.; Patil, A. S.; Butcher, R. J.; Salunke-Gawali, S. Manganese(II)-Imidazole Complexes of the Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Mefenamic Acid: Synthesis and Structural Studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 512, 119878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertcelik, M.; Ozbek, F. E. O.; Taslimi, P.; Necefoglu, H.; Hokelek, T. Supramolecular Complexes of Ni(II) and Co(II) 4-Aminobenzoate with 3-Cyanopyridine: Synthesis, Spectroscopic Characterization, Crystal Structure, and Enzyme Inhibitory Properties. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowol, C. R.; Trondl, R.; Arion, V. B.; Jakupec, M. A.; Lichtscheidl, I.; Keppler, B. K. Fluorescence Properties and Cellular Distribution of the Investigational Anticancer Drug Triapine (3-Aminopyridine-2-Carboxaldehyde Thiosemicarbazone) and Its Zinc(II) Complex. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahrovic, E.; Zahirović, A.; Pavelic, S. K.; Turkusic, E.; Harej, A. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Binuclear Ru(II) Complexes with Schiff Bases Derived from 5-Substituted Salicylaldehyde and 2-Aminopyridine with Notably Low IC50 Values. J. Coord. Chem. 2017, 70, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S. M.; Elsilk, S. Synthesis, Structural Analyses, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Water-Soluble 1D Coordination Polymer [Ag(3-Aminopyridine)]ClO4. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1149, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksrichavalit, T.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Nantasenamat, C.; Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya, C.; Prachayasittikul, V. Copper Complexes of Pyridine Derivatives with Superoxide Scavenging and Antimicrobial Activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machura, B.; Jaworska, M.; Kruszynski, R. Synthesis, Crystal, Molecular and Electronic Structure of the [ReBr₃(NO)(AsPh₃)(pzH)] Complex. Polyhedron 2004, 23, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. J.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Unusual Heterotrinuclear Co(III)Ni(II)Co(III)Hydrotris(3,5-Dimethylpyrazolyl)Borate Complex with Mixed 1,1-Azide and Pyrazolate Bridges. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2007, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinari, C.; Tabacaru, A.; Galli, S. Coordination Polymers and Metal–Organic Frameworks Based on Poly(pyrazole)-Containing Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 307, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, G.; Jana, H.; Acharjya, M.; Santra, A.; Bera, P.; Jana, A.; Panja, A.; Bera, P. Synthesis, In Vitro Evaluation of Antibacterial, Antifungal, and Larvicidal Activities of Pyrazole/Pyridine-Based Compounds and Their Nanocrystalline MS (M = Cu and Cd) Derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2017, 26, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajo, D.; Bencini, A.; Mani, F. Anisotropic Exchange in Dinuclear Complexes with Polyatomic Bridges. 2. Crystal and Molecular Structure and EPR Spectra of Tetraphenylphosphonium Bis(µ-pyrazolato)bisdihydrobis(1-pyrazolyl)boratodicuprate(II). Magneto-Structural Correlations in Bis(µ-pyrazolato)-Bridged Copper(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1988, 27, 2437. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, W. H.; Deghadi, R. G.; Mohamed, G. G. Novel Schiff Base Ligand and Its Metal Complexes with Some Transition Elements: Synthesis, Spectroscopic, Thermal Analysis, Antimicrobial and In Vitro Anticancer Activity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 30, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Rajput, L. D.; Desiraju, G. R. Designing Ternary Co-Crystals with Stacking Interactions and Weak Hydrogen Bonds: 4,4′-Bis-Hydroxyazobenzene. Cryst. Growth Des. 2014, 14, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y. J.; Han, L. J. Synthesis, X-ray Structure Analysis, and Spectroscopic Characterization of trans-Aquabis(µ-benzoato-κ²O′)Bis[µ-N,N′-Bis(4-methoxyphenyl)formamidinato-κ²N′] Dimolybdenum(II). J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2017, 47, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A. C.; Watanabe, F. W.; Ananias, S. R.; Mauro, A. E.; Netto, A. V. G.; Lima, A. P. R.; Ferreira, J. G.; Santos, R. H. A. Supramolecular Assemblies of cis-Palladium Complexes Dominated by C-H⋯Cl Interactions. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2006, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, A.; Dutta, D.; Verma, A. K.; Nath, H.; Frontera, A.; Guha, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Energetically Favorable Anti-Electrostatic Hydrogen-Bonded Cationic Clusters in Ni(II) 3,5-Dimethylpyrazole Complexes: Anticancer Evaluation and Theoretical Studies. Polyhedron 2019, 168, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, G. H.; Park, H. M.; Hyun, M. Y.; Jang, S. P.; Kim, C.; Lee, J. H.; Lee, S. J.; Kim, S. J.; Kim, Y. Anion Effects on the Crystal Structures of ZnII Complexes Containing 2,2′-Bipyridine: Their Photoluminescence and Catalytic Activities. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, A.; Islam, S. M. N.; Frontera, A.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Supramolecular Association in Cu(II) and Co(II) Coordination Complexes of 3,5-Dimethylpyrazole: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 484, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Chetry, S.; Gogoi, A.; Choudhury, B.; Guha, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Supramolecular Association Involving Anion–π Interactions in Cu(II) Coordination Solids: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Polyhedron 2018, 151, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Gogoi, A.; Verma, A. K.; Frontera, A.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Charge-Assisted Hydrogen Bond and Nitrile⋯Nitrile Interaction Directed Supramolecular Associations in Cu(II) and Mn(II) Coordination Complexes: Anticancer, Hematotoxicity, and Theoretical Studies. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harit, T.; Malek, F.; El-Bali, B.; Khan, A.; Dalvandi, K.; Marasini, B. P.; Noreen, S.; Malik, R.; Khan, S.; Choudhary, M. I. Synthesis and Enzyme Inhibitory Activities of Some New Pyrazole-Based Heterocyclic Compounds. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunagariya, M. V.; Thakor, K. P.; Varma, R. R.; Waghela, B. N.; Pathak, C.; Patel, M. N. Synthesis, Characterization, and Biological Application of 5-Quinoline 1,3,5-Trisubstituted Pyrazole-Based Platinum(II) Complexes. MedChemComm 2018, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karrouchi, K.; Yousfi, E. B.; Sebbar, N. K.; Ramli, Y.; Taoufik, J.; Ouzidan, Y.; Ansar, M.; Mabkhot, Y. N.; Ghabbour, H. A.; Radi, S. New Pyrazole-Hydrazone Derivatives: X-ray Analysis, Molecular Structure Investigation via Density Functional Theory (DFT), and Their High In-Situ Catecholase Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdya, S.; Roy, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Bauza, A.; Frontera, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Importance of π-Interactions Involving Chelate Rings in Addition to Tetrel Bonds in Crystal Engineering: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study on a Series of Hemi- and Holodirected Nickel(II)/Lead(II) Complexes. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudov, K. T.; Kopylovich, M. N.; Silva, M. F. C. G.; Pombeiro, A. J. L. Non-Covalent Interactions in the Synthesis of Coordination Compounds: Recent Advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 345, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, D.; Sharma, P.; Gomila, R. M.; Frontera, A.; Barcelo-Oliver, M.; Verma, A. K.; Baishya, T.; Bhattacharyyaa, M. K. Supramolecular Assemblies Involving Unconventional Non-Covalent Contacts in Pyrazole-Based Coordination Compounds of Co(II) and Cu(II) Pyridinedicarboxylates: Antiproliferative Evaluation and Theoretical Studies. Polyhedron 2022, 224, 116025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-ghamry, M. A.; Shebl, M.; Saleh, A. A.; Khalil, S. M. E.; Amir, M. D.; Ali, A. M. Spectroscopic Characterization of Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II) Complexes, and Nano Copper Complex Bearing a New S, O, N-Donor Chelating Ligand. 3D Modeling Studies, Antimicrobial, Antitumor, and Catalytic Activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1249, 131587. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiyi, F. S.; Olanrewaju, A. A. Synthesis, Characterization, Thermogravimetric and Antioxidant Studies of New Cu(II), Fe(II), Mn(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), Co(II), and Ni(II) Complexes with Benzoic Acid and 4,4,4-Trifluoro-1-(2-Naphthyl)-1,3-Butanedione. Int. J. Chem. 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rossin, A.; Credico, B. D.; Giambastiani, G.; Peruzzini, M.; Pescitelli, G.; Reginato, G.; Borfecchia, E.; Gianolio, D.; Lamberti, C.; Bordiga, S. Synthesis, Characterization, and CO2 Uptake of a Chiral Co(II) Metal–Organic Framework Containing a Thiazolidine-Based Spacer. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 10335. [Google Scholar]

- Etter, M. C. Encoding and Decoding Hydrogen-Bond Patterns of Organic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Janiak, C. A Critical Account on π–π Stacking in Metal Complexes with Aromatic Nitrogen-Containing Ligands. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 2000, 21, 3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, Y. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Magnetic Properties of a New 1D Cobalt(II) Complex with 1,10-Phenanthroline and 3,5-Dinitrosalicylate Acid Ligands. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2005, 8, 983. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, T. S.; Bauza, A.; Dutta, D.; Mishra, S.; Frontera, A.; Ray, D. Carboxylate Coordination Assisted Aggregation for Quasi-Tetrahedral and Partial-Dicubane [Cu4] Coordination Clusters. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, O.; Colak, A. T.; Emen, F. M.; Kismali, G.; Meral, O.; Sel, T.; Cilgi, G. K.; Tas, M. Syntheses of Crystal Structures and In Vitro Cytotoxic Activities of New Copper(II) Complexes of Pyridine-2,6-Dicarboxylate. J. Coord. Chem. 2015, 68, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S. C.; Mistria, S.; Jana, A. D. A Rare Supramolecular Assembly Involving Ion Pairs of Coordination Complexes with a Host–Guest Relationship: Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Photoluminescence, and Thermal Study. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, M. K.; Dutta, D.; Islam, S. M. N.; Frontera, A.; Sharma, P.; Verma, A. K.; Das, A. Energetically Significant Antiparallel π-Stacking Contacts in Co(II), Ni(II), and Cu(II) Coordination Compounds of Pyridine-2,6-Dicarboxylates: Antiproliferative Evaluation and Theoretical Studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 501, 119233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycan, T. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Spectroscopic (FT-IR, UV–Vis, EPR) and Hirshfeld Surface Analysis Studies of Zn(II)-Benzoate Coordination Dimer. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1223, 128943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, K. Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Dutta, D.; Gomila, R. M.; Frontera, A.; Barcelo-Oliver, M.; Verma, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Benzoato Bridged Dinuclear Mn(II) and Cu(II) Compounds Involving Guest Chlorobenzoates and Dimeric Paddle Wheel Supramolecular Assemblies: Antiproliferative Evaluation and Theoretical Studies. Polyhedron 2021, 208, 115409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Islam, S. M. N.; Saha, U.; Chetry, S.; Guha, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Cu(II) and Co(II) Coordination Solids Involving Unconventional Parallel Nitrile(π)–Nitrile(π) and Energetically Significant Cooperative Hydrogen Bonding Interactions: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1195, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Islam, S. M. N.; Saha, U.; Chetry, S.; Guha, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Structural Topology of Weak Non-Covalent Interactions in a Layered Supramolecular Coordination Solid of Zinc Involving 3-Aminopyridine and Benzoate: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2018, 48, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyüz, S. The FT-IR Spectra of Transition Metal 3-Aminopyridine Tetracyanonickelate Complexes. J. Mol. Struct. 1998, 449, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dojer, B.; Pevec, A.; Jagodic, M.; Kristl, M.; Drofenik, M. Three New Cobalt(II) Carboxylates with 2-, 3-, and 4-Aminopyridine: Syntheses, Structures, and Magnetic Properties. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2012, 383, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bora, S. J.; Das, B. K. Synthesis and Properties of a Few 1-D Cobaltous Fumarates. J. Solid State Chem. 2012, 192, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S. S.; Gilani, S. R.; Tahir, M. N.; Harrison, W. T. A. Z. Syntheses and Structures of Monomeric and Dimeric Ternary Complexes of Copper(II) with 2,2′-Bipyridyl and Carboxylate Ligands. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2016, 642, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, D.; Lal, R. A.; Kumar, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Low- and High-Spin Manganese(II) Complexes of Polyfunctional Adipoyldihydrazone: Effect of Coordination of N-Donor Ligands on Stereo-Redox Chemistry. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1092, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S. M. N.; Dutta, D.; Guha, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. An Unusual Werner-Type Clathrate of Mn(II) Benzoate Involving Energetically Significant Weak C–H⋯C Contacts: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1175, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goher, M. A.; Hafez, A. K.; Abu-Youssef, M. A. M.; Badr, A. M. A.; Gspan, C.; Mautner, F. A. New Metal(II) Complexes Containing Monodentate and Bridging 3-Aminopyridine and Azido Ligands. Polyhedron 2004, 23, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukkumar, M.; Karthikeyan, A.; Kamalesu, S.; Kadri, M.; Jennifer, S. J.; Razak, I. A.; Nehru, S. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Optical and DFT Studies of a Novel Co(II) Complex with the Mixed Ligands 3-Bromothiophene-2-Carboxylate and 2-Aminopyridine. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1270, 133953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, S.; Shi, S.; Zang, J. Crystal Structure and Properties of a Terbium m-Methylbenzoate Complex with 1,10-Phenanthroline. J. Coord. Chem. 2002, 55, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, F.; Tesei, A.; Arienti, C.; Bevilacqua, A. Cell Counting and Viability Assessment of 2D and 3D Cell Cultures: Expected Reliability of the Trypan Blue Assay. Biol. Proced. Online 2017, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, P. F.; Chen, J.; Byun, J. H.; Platko, K.; Austin, R. C. The Trypan Blue Cellular Debris Assay: A Novel Low-Cost Method for the Rapid Quantification of Cell Death. MethodsX 2019, 6, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, M. E.; Manfredi, A. Chromatin and Cell Death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Struct. Expr. 2004, 1677, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, A. H.; Beattie, G. J.; Hargreaves, A. D. Chromatin Changes in Apoptosis. Histochem. J. 1981, 13, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. K.; Prasad, S. B. Antitumor Effect of Blister Beetles: An Ethno-Medicinal Practice in Karbi Community and Its Experimental Evaluation Against a Murine Malignant Tumor Model. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, A.; Das, A.; Frontera, A.; Verma, A. K.; Bhattacharyya, M. K. Energetically Significant Unconventional π–π Contacts Involving Fumarate in a Novel Coordination Polymer of Zn(II): In-Vitro Anticancer Evaluation and Theoretical Studies. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2019, 493, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, S.; Mizoshita, T.; Ozeki, K.; Tsukamoto, H.; Kamiya, T.; Kataoka, H.; Joh, T. Mechanisms of Cisplatin-Induced Apoptosis and of Cisplatin Sensitivity: Potential of BIN1 to Act as a Potent Predictor of Cisplatin Sensitivity in Gastric Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 2012, 862879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A. P.; Pereira, F. C.; Almeida, M. A. P.; Mello, F. M. S.; Pires, W. C.; Pinto, T. M.; Delella, F. K.; Felisbino, S. L.; Moreno, V.; Batista, A. A.; de Paula Silveira-Lacerda, E. PLoS One 2014, 9, 105865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S. K.; Lee, S. B.; Won, J.; Choi, H. Y.; Kim, K.; Yang, G. M.; Cho, S. G. Correlation Between Oxidative Stress, Nutrition, and Cancer Initiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. K.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Goswami, B. C.; Camps, I.; Sekar, A.; Yoon, S.; Lee, S. Repurposing Potential of Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants Derived Active Principles Against SARS-CoV-2 Associated Target Proteins Revealed by Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics, and MM-PBSA Studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, R.; Christensen, M. H. MolDock: A New Technique for High Accuracy Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A. K.; Aggarwal, R. Repurposing Potential of FDA-Approved and Investigational Drugs for COVID-19 Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Main Protease and Validation by Machine Learning Algorithm. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020, 97, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, A.; Fairbrother, W. J.; Leverson, J. D.; Souers, A. J. From Basic Apoptosis Discoveries to Advanced Selective BCL-2 Family Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

SADABS, V2.05; Bruker AXS: Madison, WI, USA, 1999.

- Sheldrick, G. M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L. J. WinGX Suite for Small-Molecule Single-Crystal Crystallography. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1999, 32, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K. Diamond 3.1f, Crystal Impact GbR, Bonn, Germany, 2008.

- Ahlrichs, R.; Bär, M.; Hacer, M.; Horn, H.; Kömel, C. Electronic Structure Calculations on Workstation Computers: The Program System Turbomole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 162, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A. D. Density-Functional Exchange-Energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeweyher, E.; Mewes, J.-M.; Ehlert, S.; Grimme, S. Extension and Evaluation of the D4 London-Dispersion Model for Periodic Systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, R. F. W. A Quantum Theory of Molecular Structure and Its Applications. Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E. R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A. J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, J. W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graphics 1996, 14, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Singh, N. S.; Aggarwal, R.; Verma, A. K. Cordyceps militaris: A Comprehensive Study on Laboratory Cultivation and Anticancer Potential in Dalton's Ascites Lymphoma Tumor Model. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan Blue Exclusion Test of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2015, 111, A3-B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, J.; Fatmi, M. Q.; Devi, M.; Singh, N. S.; Verma, A. K. Antitumor Activity of Cordycepin in Murine Malignant Tumor Cell Line: An In Vitro and In Silico Study. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1297, 136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. K.; Prasad, S. B. Bioactive Component, Cantharidin from Mylabris cichorii and Its Antitumor Activity Against Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2012, 28, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of [Co(H2O)(bz)2(μ-3-Ampy)2]n (1).

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of [Co(H2O)(bz)2(μ-3-Ampy)2]n (1).

Figure 2.

1D polymeric chain of compound 1 involving intra-molecular CR∙∙∙π, C‒H∙∙∙O, N‒H∙∙∙O, C‒H∙∙∙N and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions.

Figure 2.

1D polymeric chain of compound 1 involving intra-molecular CR∙∙∙π, C‒H∙∙∙O, N‒H∙∙∙O, C‒H∙∙∙N and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions.

Figure 3.

Layered assembly of polymeric complex 1 along the crystallographic ab plane assisted by C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions.

Figure 3.

Layered assembly of polymeric complex 1 along the crystallographic ab plane assisted by C‒H∙∙∙O hydrogen bonding and C‒H∙∙∙C interactions.

Figure 4.