Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

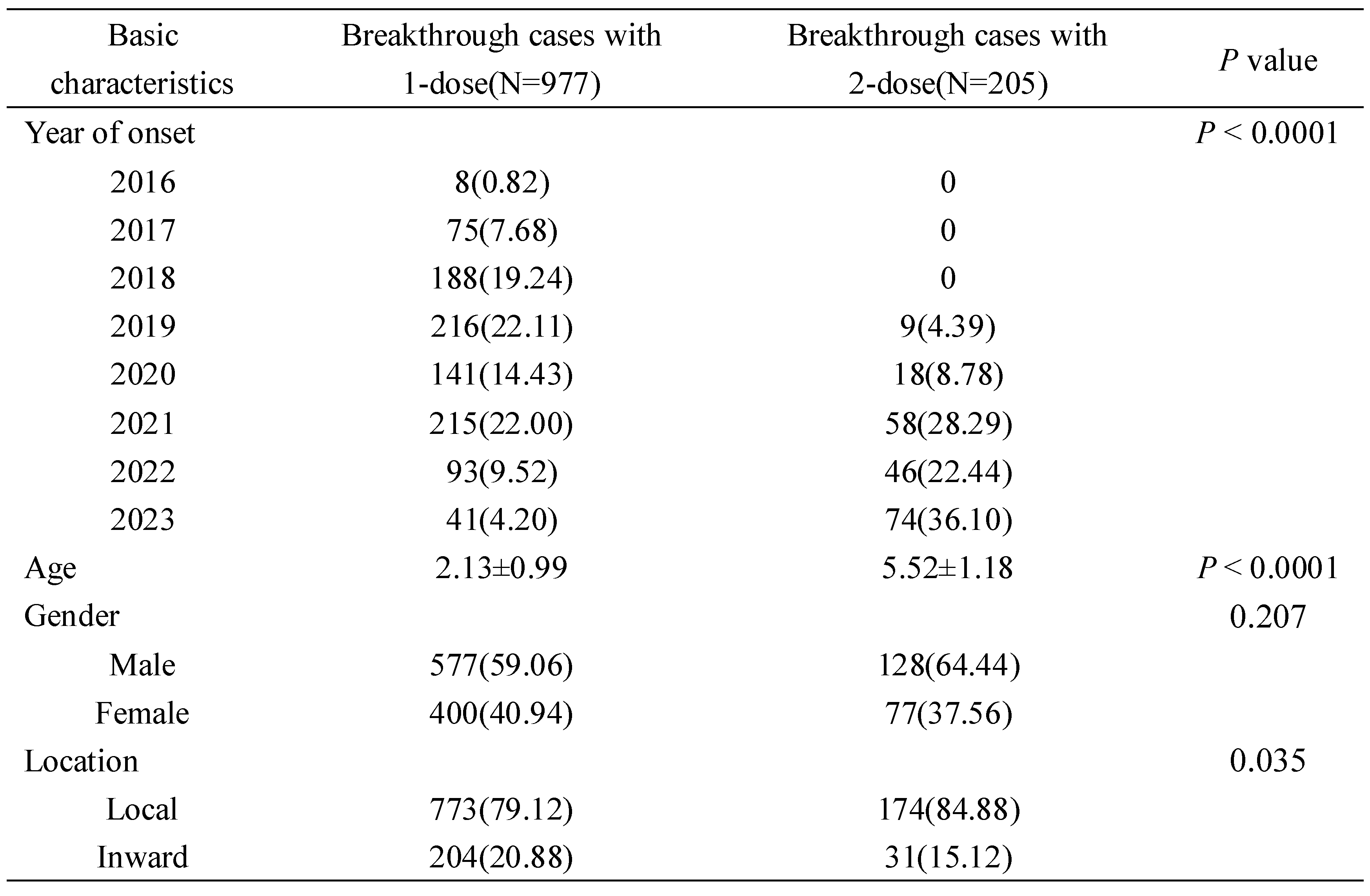

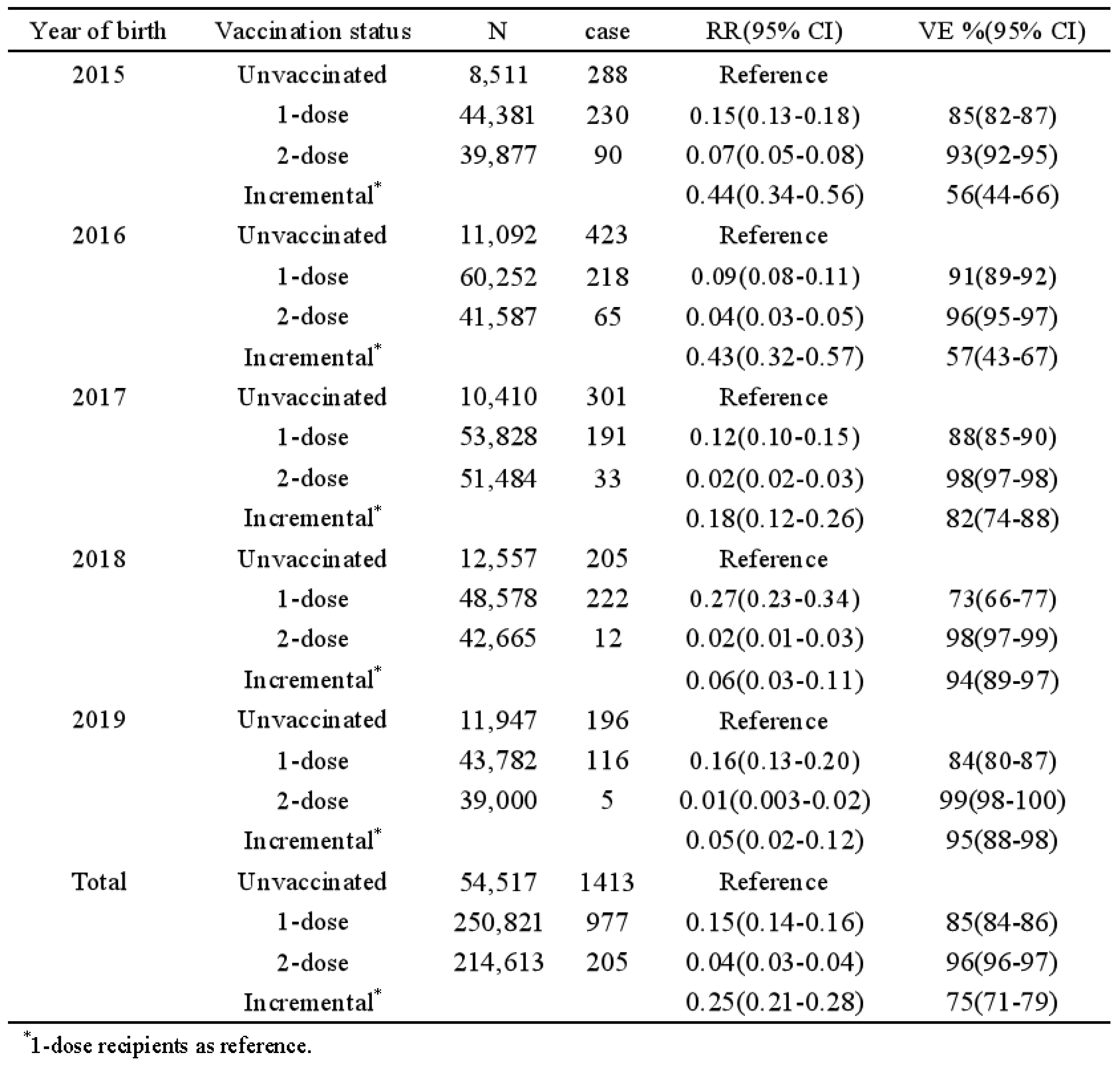

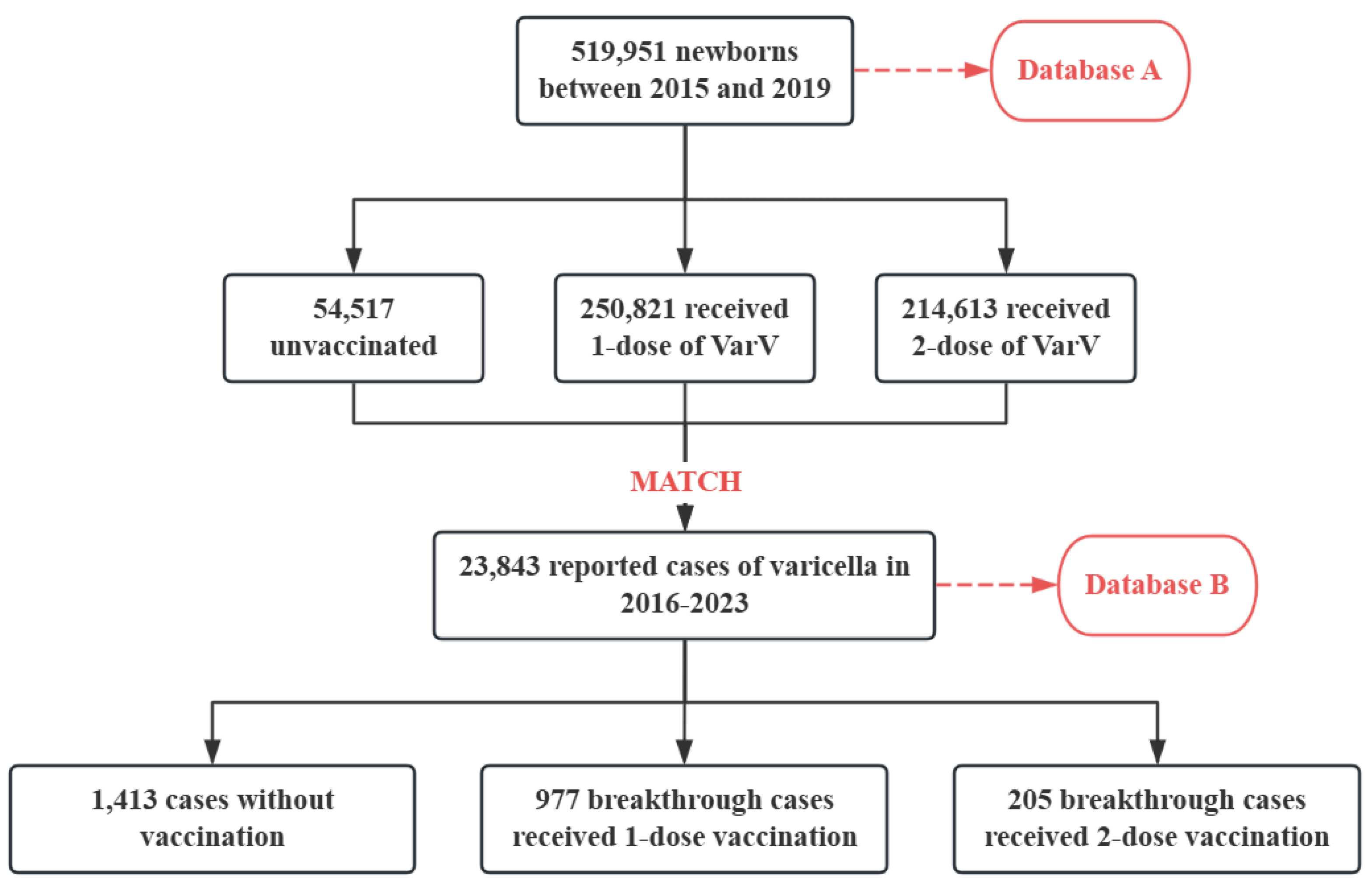

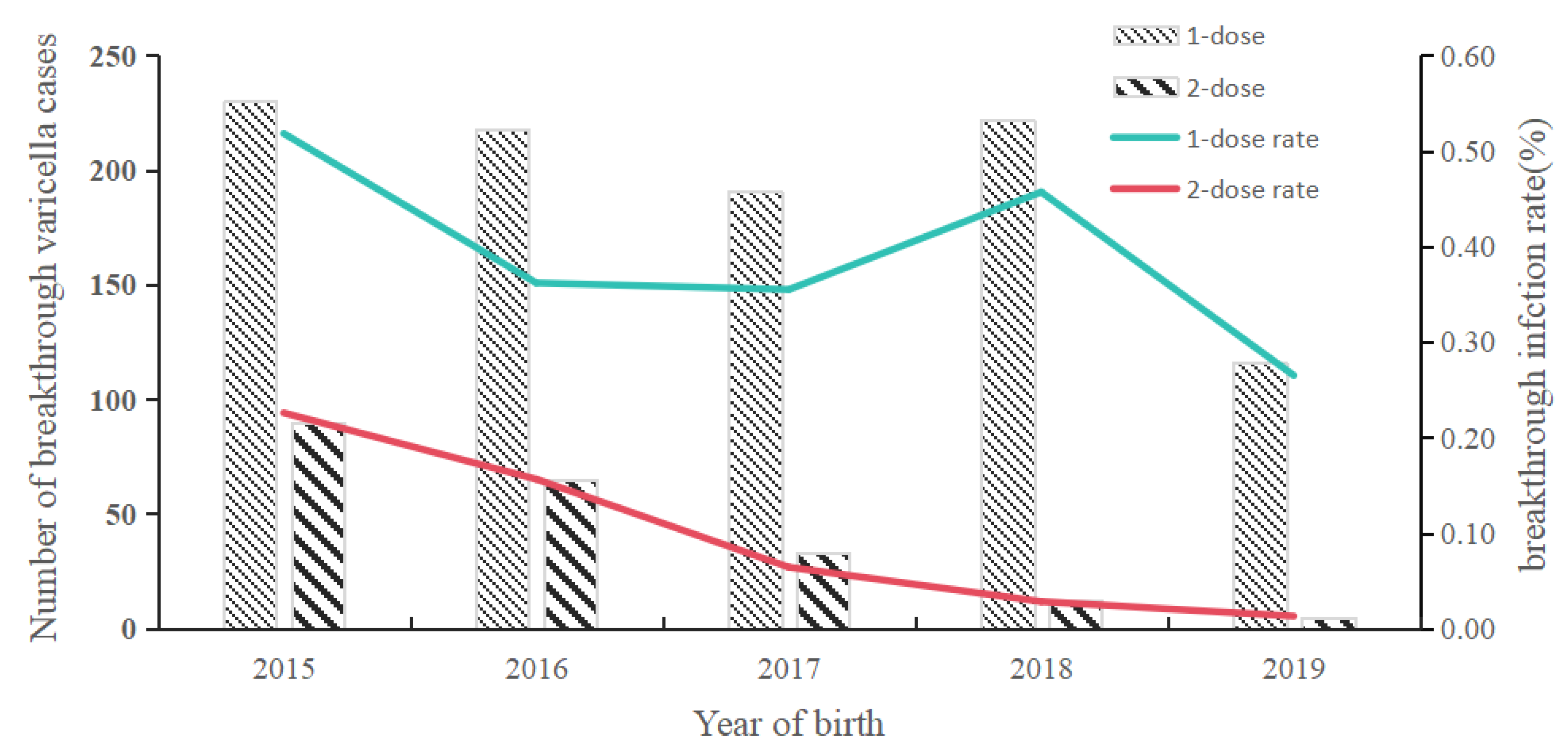

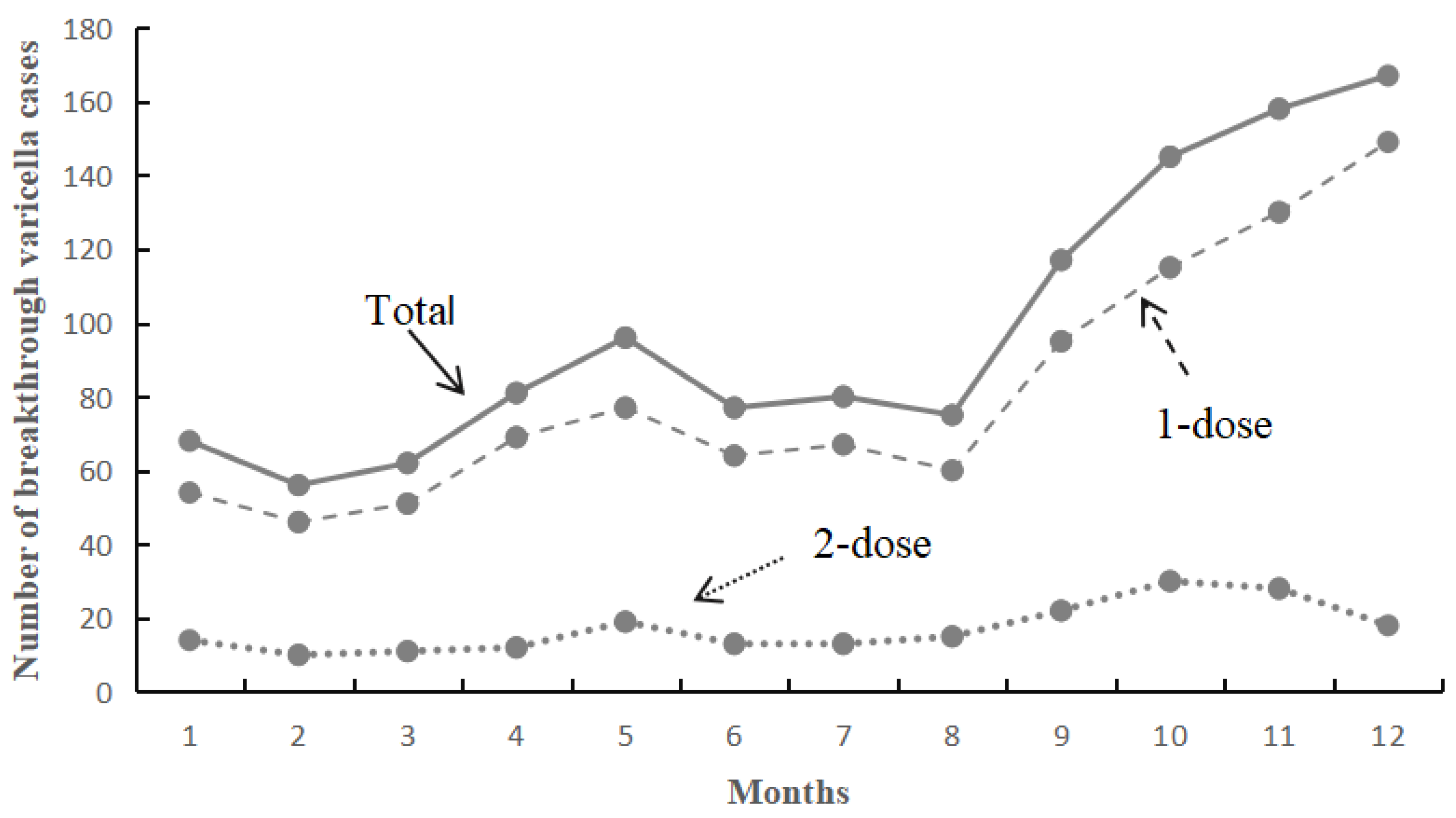

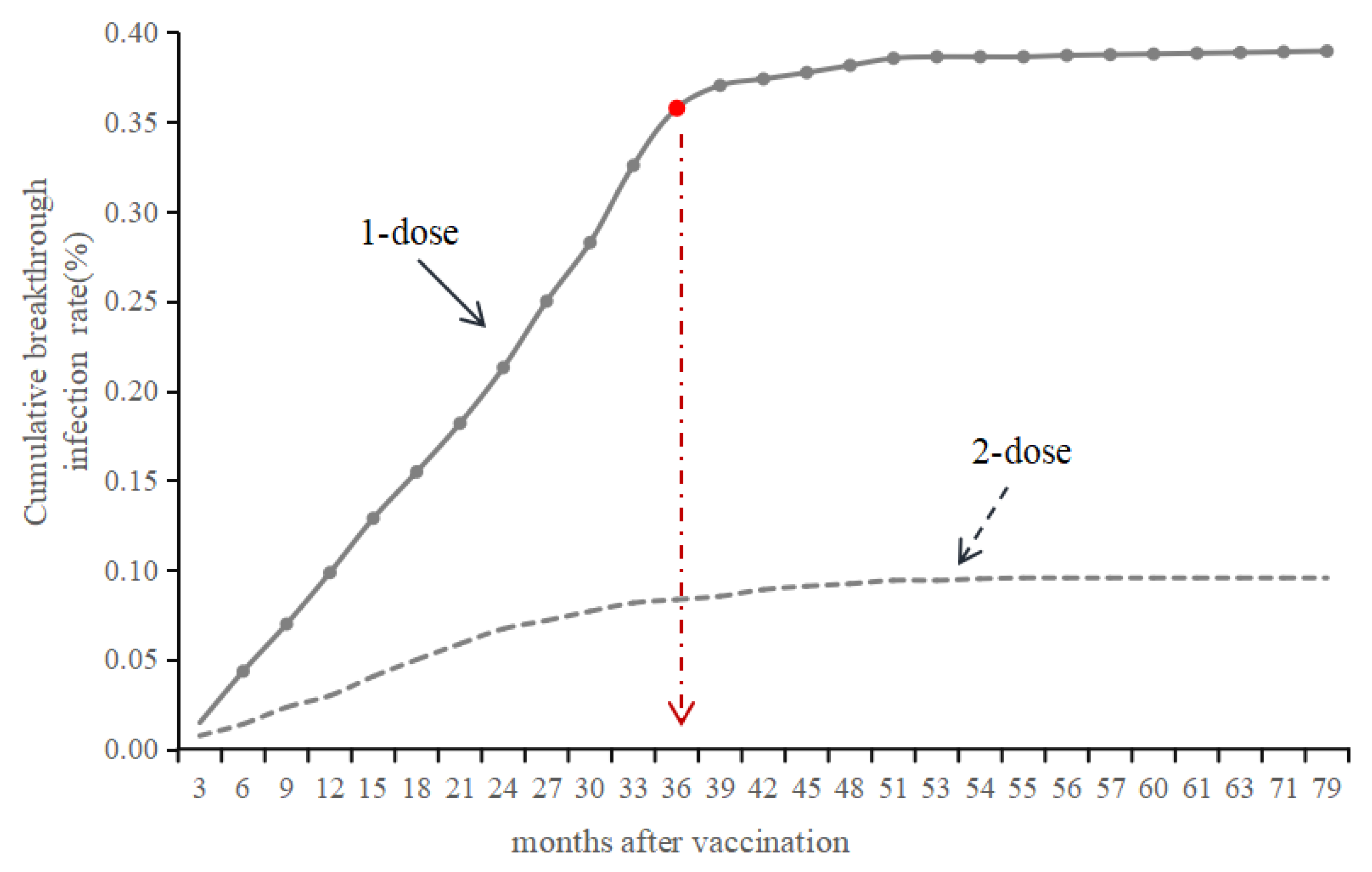

The 2-dose varicella vaccination strategy has been implemented in Shanghai, China since 2018. This study aims to analyze the epidemiological characteristics of breakthrough varicella cases and to evaluate the incremental effectiveness of the 2-dose varicella vaccination among Chinese children. We enrolled children born from 2015 to 2019 who experienced varicella breakthrough infections following the administration of the receiving varicella vaccine (VarV) that occurred on or before December 31, 2023 in Pudong New Area, Shanghai. Demographic information and data regarding varicella vaccination were collected by Shanghai Immunization Information System, while information on varicella infections was obtained from China Information System for Disease Control and Prevention. The incremental vaccine effectiveness (VE) for varicella was defined as (1-relative risk (RR)) *100%, where RRs were calculated based on the rate of breakthrough infections. The overall rate of breakthrough varicella infections was found to be 0.25%, corresponding to 1,182 cases. Specifically, the rates of breakthrough varicella infections for individuals who received 1-dose and 2-dose VarV were 0.39% (977 cases) and 0.10% (205 cases), respectively. The average ages of onset for these infections were 2.13±0.99 years and 5.52±1.18 years, respectively. Furthermore, the breakthrough varicella infection rate among individuals born between 2015 and 2019 exhibited a decline, decreasing from 0.52% to 0.26% for those who received 1-dose of VarV, and from 0.23% to 0.01% for those who received 2-dose. The incremental VE for the two-dose regimen was recorded at 56% and 57% for individuals born in 2015 and 2016, respectively, which was significantly lower than the VE of 94% and 95% observed for those born in 2018 and 2019. The incidence of breakthrough varicella among children in Pudong, Shanghai, has shown an upward trend over time following the implementation of Varicella vaccination. Furthermore, the 2-dose VarV vaccination strategy significantly reduced breakthrough incidence, which should be recommended to prevent the varicella disease among children in other provinces of China.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Varicella Cases Surveillance

2.2. Varicella Vaccination

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Definitions

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Description

3.2. Overall Breakthrough of Varicella Infection

3.3. Comparison of Basic Characteristics

3.4. Time Interval Between VarV Vaccination and Onset

3.5. Vaccine Effectiveness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gershon AA. Is chickenpox so bad, what do we know about immunity to varicella zoster virus, and what does it tell us about the future? J Infect. 2017;74 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S27-S33. [CrossRef]

- Xiu S, Xu Z, Wang X, Zhang L, Wang Q, Yang M, Shen Y. Varicella vaccine effectiveness evaluation in Wuxi, China: A retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Infect. 2024;152:e105. [CrossRef]

- Hu P, Yang F, Li X, Wang Y, Xiao T, Li H, Wang W, Guan J, Li S. Effectiveness of one-dose versus two-dose varicella vaccine in children in Qingdao, China: a matched case-control study. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):5311-5. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhang X, Du J, Cai Y, Wang J, Che X, Gu W, Jiang W, Chen J. Epidemiology of varicella and effectiveness of varicella vaccine in Hangzhou, China, 2019. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(1):211-6. [CrossRef]

- Kawamura Y, Hattori F, Higashimoto Y, Kozawa K, Yoshikawa T. Evaluation of varicella vaccine effectiveness during outbreaks in schools or nurseries by cross-sectional study. Vaccine. 2021;39(21):2901-5. [CrossRef]

- Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: WHO position paper, June 2014. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89(25):265-87.

- Huang J, Wu Y, Wang M, Jiang J, Zhu Y, Kumar R, Lin S. The global disease burden of varicella-zoster virus infection from 1990 to 2019. J Med Virol. 2022;94(6):2736-46. [CrossRef]

- Lieu TA, Cochi SL, Black SB, Halloran ME, Shinefield HR, Holmes SJ, Wharton M, Washington AE. Cost-effectiveness of a routine varicella vaccination program for US children. JAMA. 1994;271(5):375-81.

- Lenne X, Diez Domingo J, Gil A, Ridao M, Lluch JA, Dervaux B. Economic evaluation of varicella vaccination in Spain: results from a dynamic model. Vaccine. 2006;24(47-48):6980-9. [CrossRef]

- Pawaskar M, Meroc E, Samant S, Flem E, Bencina G, Riera-Montes M, Heininger U. Economic burden of varicella in Europe in the absence of universal varicella vaccination. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):2312. [CrossRef]

- Zha WT, Pang FR, Zhou N, Wu B, Liu Y, Du YB, Hong XQ, Lv Y. Research about the optimal strategies for prevention and control of varicella outbreak in a school in a central city of China: based on an SEIR dynamic model. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e56. [CrossRef]

- Leung J, Harpaz R. Impact of the Maturing Varicella Vaccination Program on Varicella and Related Outcomes in the United States: 1994-2012. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5(4):395-402. [CrossRef]

- Scotta MC, Paternina-de la Ossa R, Lumertz MS, Jones MH, Mattiello R, Pinto LA. Early impact of universal varicella vaccination on childhood varicella and herpes zoster hospitalizations in Brazil. Vaccine. 2018;36(2):280-4. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Yang H, Li K, Zhang A, Feng Z, Seward JF, Bialek SR, Wang C. Single-dose varicella vaccine effectiveness in school settings in China. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3834-8. [CrossRef]

- Pan X, Shu M, Ma R, Fang T, Dong H, Sun Y, Xu G. Varicella breakthrough infection and effectiveness of 2-dose varicella vaccine in China. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5665-70. [CrossRef]

- Chaves SS, Gargiullo P, Zhang JX, Civen R, Guris D, Mascola L, Seward JF. Loss of vaccine-induced immunity to varicella over time. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(11):1121-9. [CrossRef]

- Leung J, Broder KR, Marin M. Severe varicella in persons vaccinated with varicella vaccine (breakthrough varicella): a systematic literature review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16(4):391-400. [CrossRef]

- Suo L, Lu L, Wang Q, Yang F, Wang X, Pang X, Marin M, Wang C. Varicella outbreak in a highly-vaccinated school population in Beijing, China during the voluntary two-dose era. Vaccine. 2017;35(34):4368-73. [CrossRef]

- Vitale F, Amodio E. Evaluation of varicella vaccine effectiveness as public health tool for increasing scientific evidence and improving vaccination programs. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2020;96(6):670-2. [CrossRef]

- Azzari C, Baldo V, Giuffrida S, Gani R, O'Brien E, Alimenti C, Daniels VJ, Wolfson LJ. The Cost-Effectiveness of Universal Varicella Vaccination in Italy: A Model-Based Assessment of Vaccination Strategies. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:273-83. [CrossRef]

- Wu QS, Wang X, Liu JY, Chen YF, Zhou Q, Wang Y, Sha JD, Xuan ZL, Zhang LW, Yan L, Hu Y. Varicella outbreak trends in school settings during the voluntary single-dose vaccine era from 2006 to 2017 in Shanghai, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2019;89:72-8. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Li X, Yuan L, Sun Q, Fan J, Jing Y, Meng S. Analysis on the epidemiological characteristics of varicella and breakthrough case from 2014 to 2022 in Qingyang City. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2023;19(2):2224075. [CrossRef]

- Shu M, Zhang D, Ma R, Yang T, Pan X. Long-term vaccine efficacy of a 2-dose varicella vaccine in China from 2011 to 2021: A retrospective observational study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1039537. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S, Zeng F, Xia L, He H, Zhang J. Incidence rate of breakthrough varicella observed in healthy children after 1 or 2 doses of varicella vaccine: Results from a meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46(1):e1-e7. [CrossRef]

- Bonanni P, Zanobini P. Universal and targeted varicella vaccination. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):11-2. [CrossRef]

- Lachiewicz AM, Srinivas ML. Varicella-zoster virus post-exposure management and prophylaxis: A review. Prev Med Rep. 2019;16:101016. [CrossRef]

- Yin M, Xu X, Liang Y, Ni J. Effectiveness, immunogenicity and safety of one vs. two-dose varicella vaccination:a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2018;17(4):351-62. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro ED, Vazquez M, Esposito D, Holabird N, Steinberg SP, Dziura J, LaRussa PS, Gershon AA. Effectiveness of 2 doses of varicella vaccine in children. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(3):312-5. [CrossRef]

- Lopez AS, Zhang J, Marin M. Epidemiology of Varicella During the 2-Dose Varicella Vaccination Program - United States, 2005-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(34):902-5. [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann F, Bechini A, Bonanni P, Casabona G, Wutzler P. Varicella vaccination in Italy and Germany - different routes to success: a systematic review. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2020;19(9):843-69. [CrossRef]

- Iftimi A, Montes F, Santiyan AM, Martinez-Ruiz F. Space-time airborne disease mapping applied to detect specific behaviour of varicella in Valencia, Spain. Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol. 2015;14-15:33-44. [CrossRef]

- Koshy E, Mengting L, Kumar H, Jianbo W. Epidemiology, treatment and prevention of herpes zoster: A comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2018;84(3):251-62. [CrossRef]

- Johnson RW, Wasner G, Saddier P, Baron R. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia: optimizing management in the elderly patient. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):991-1006. [CrossRef]

- Sumi A. Role of temperature in reported chickenpox cases in northern European countries: Denmark and Finland. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):377. [CrossRef]

- Gershon AA, Gershon MD, Breuer J, Levin MJ, Oaklander AL, Griffiths PD. Advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis and epidemiology of herpes zoster. J Clin Virol. 2010;48 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S2-7. [CrossRef]

- Huang WC, Huang LM, Chang IS, Tsai FY, Chang LY. Varicella breakthrough infection and vaccine effectiveness in Taiwan. Vaccine. 2011;29(15):2756-60. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro ED, Marin M. The Effectiveness of Varicella Vaccine: 25 Years of Postlicensure Experience in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(Suppl 4):S425-S30. [CrossRef]

- Shi L, Lu J, Sun X, Li Z, Zhang L, Lu Y, Yao Y. Impact of Varicella Immunization and Public Health and Social Measures on Varicella Incidence: Insights from Surveillance Data in Shanghai, 2013-2022. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(11). [CrossRef]

- Bonanni P, Gershon A, Gershon M, Kulcsar A, Papaevangelou V, Rentier B, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Usonis V, Vesikari T, Weil-Olivier C, de Winter P, Wutzler P. Primary versus secondary failure after varicella vaccination: implications for interval between 2 doses. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(7):e305-13. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).