Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 13A70, 05C25, 05E40

1. Introduction

2. Key Definitions and Notations

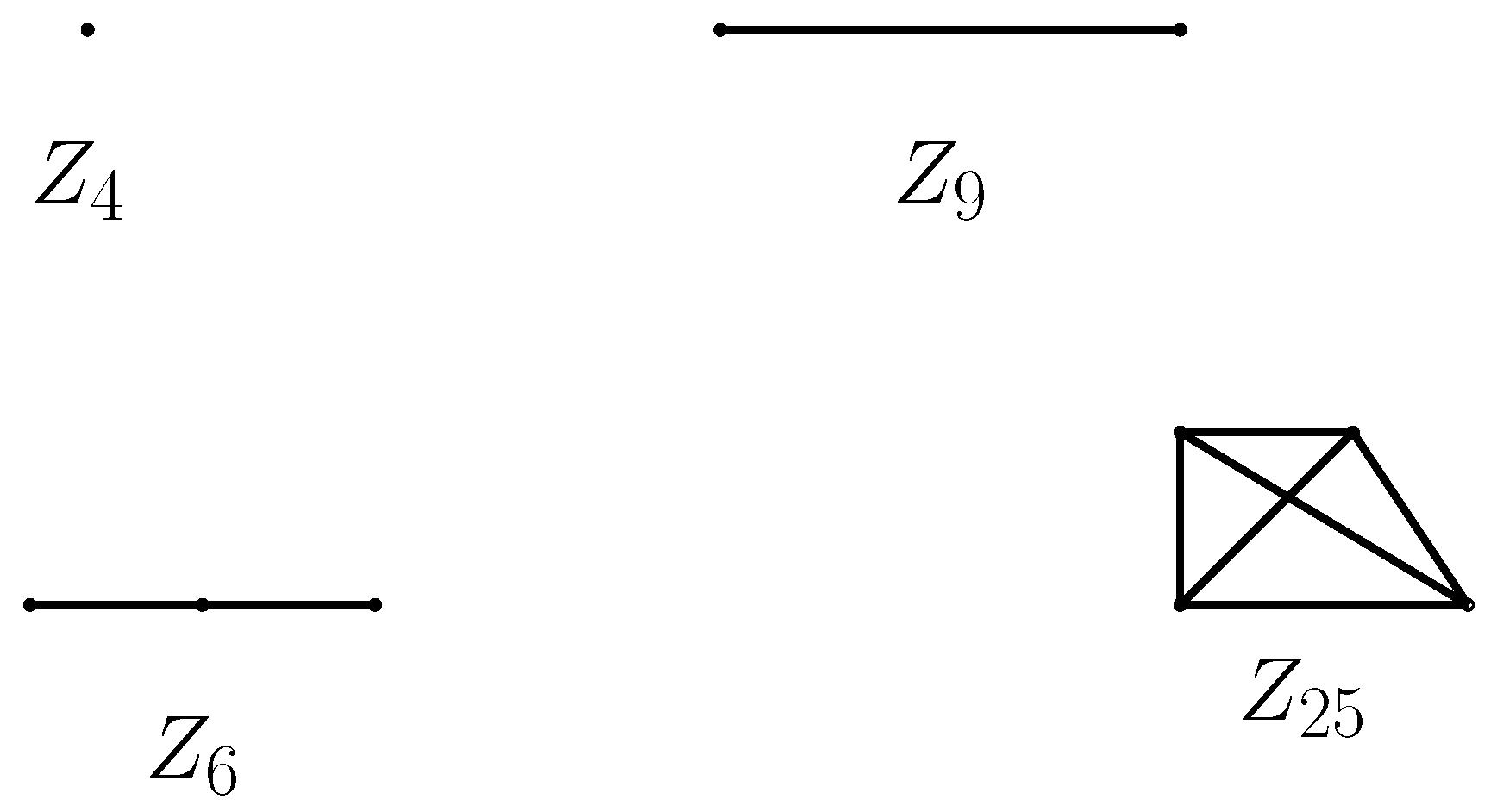

3. Zero Divisor Graph of , for Square Free n

- (1)

- is a complete bi-partite graph. In particular, if, thenis a star graph and the centre of=.

- (2)

- diameter, i.e., diam(.

- (3)

- radius, rad(, ifand otherwise 2.

- 1

-

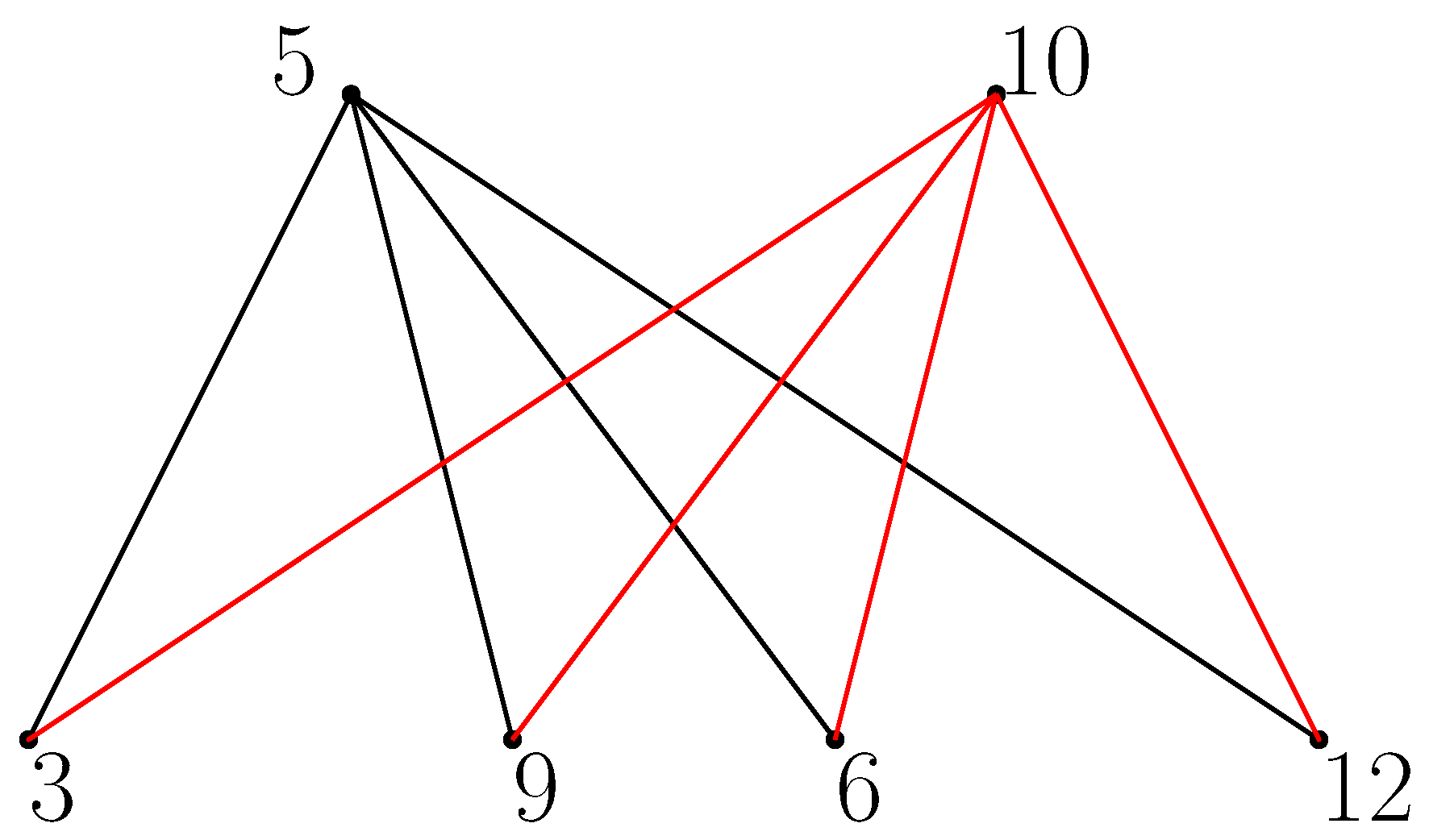

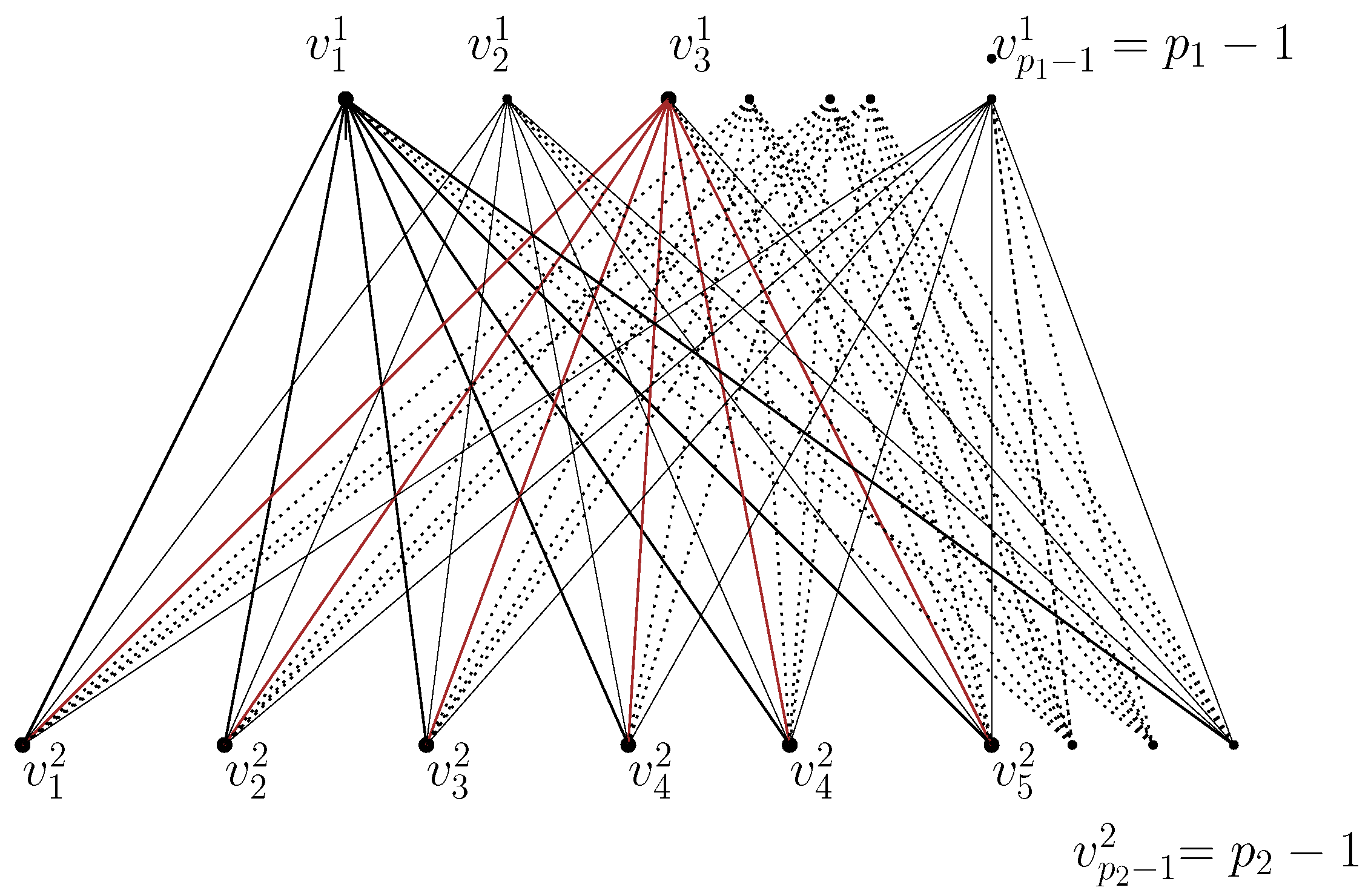

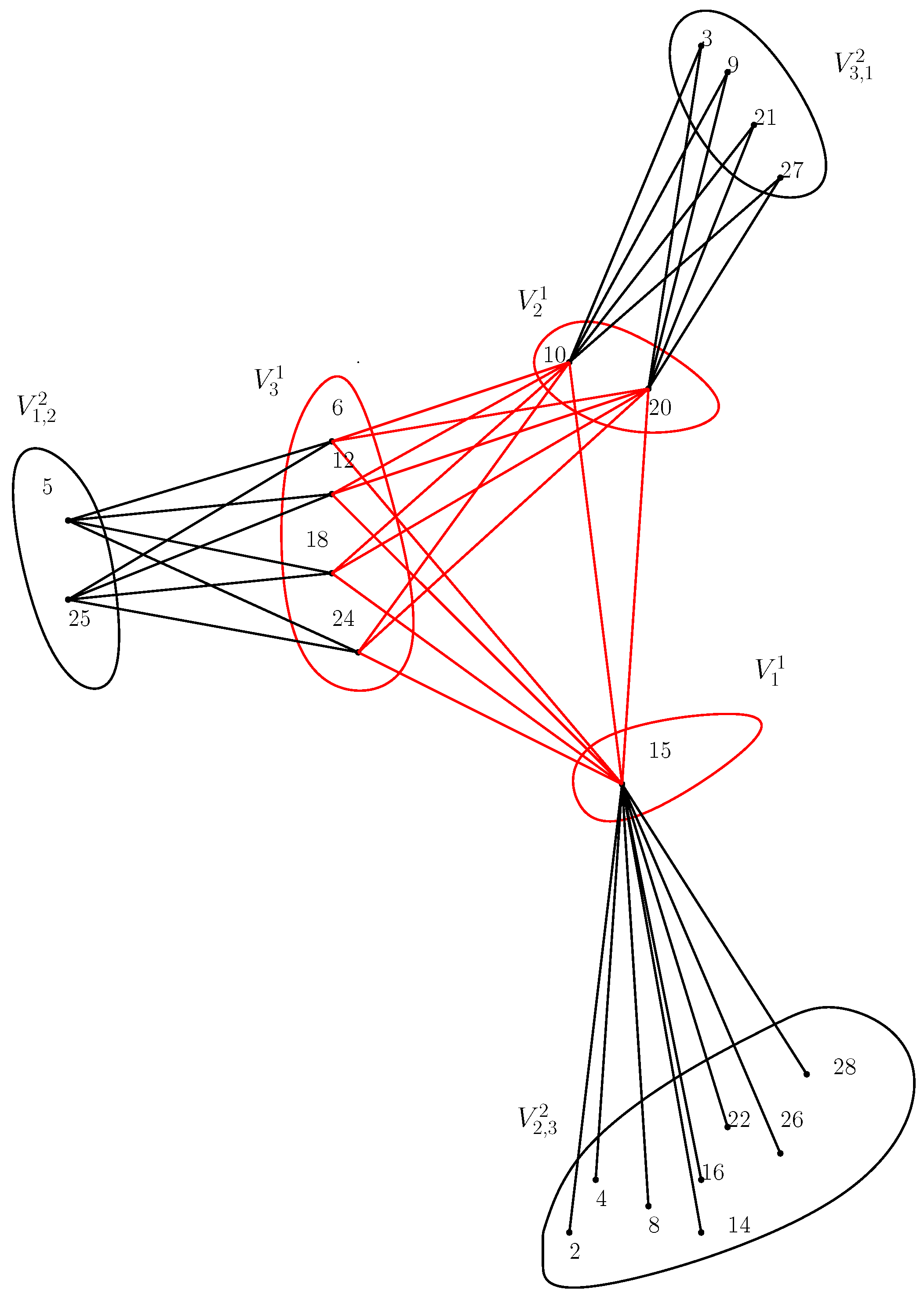

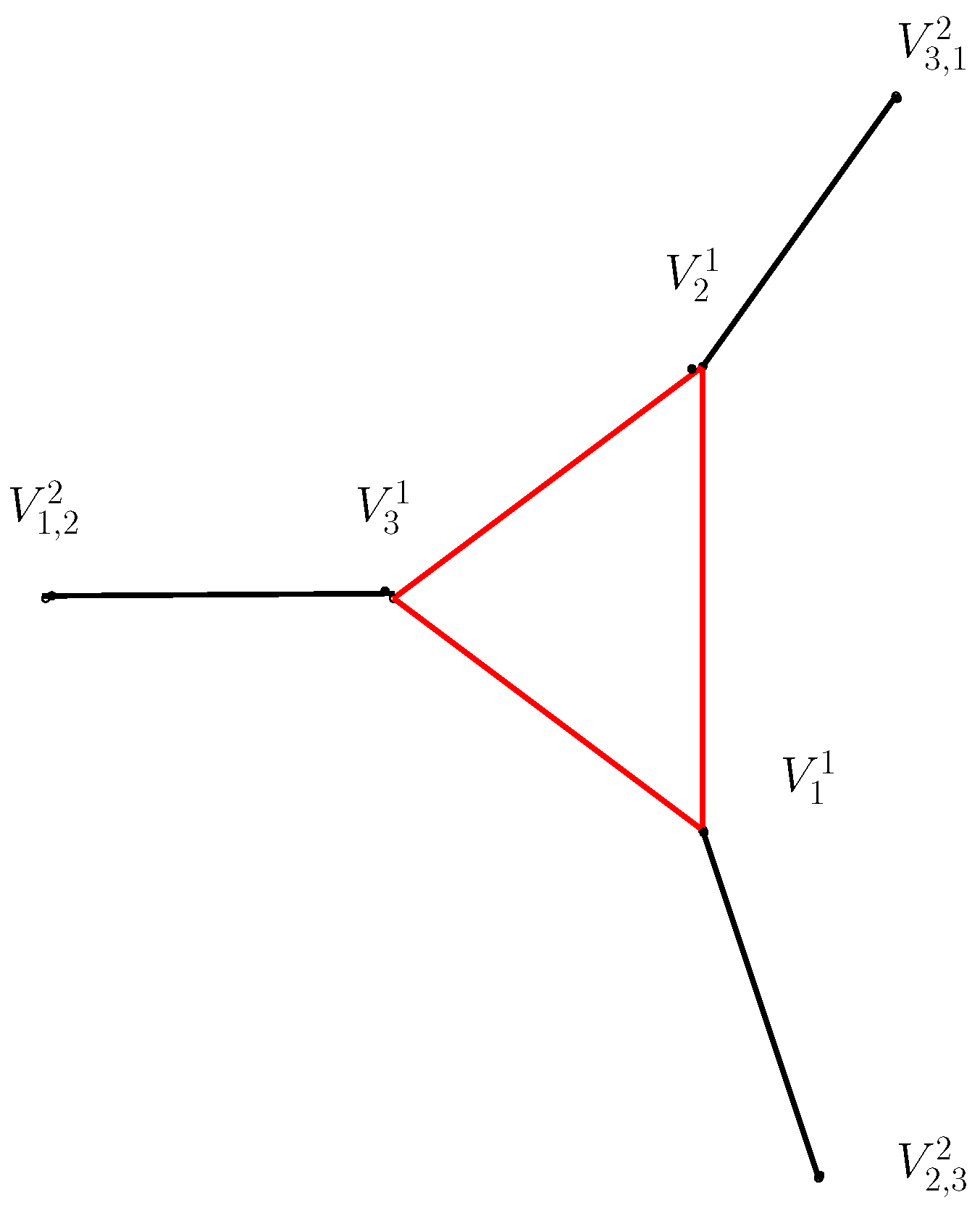

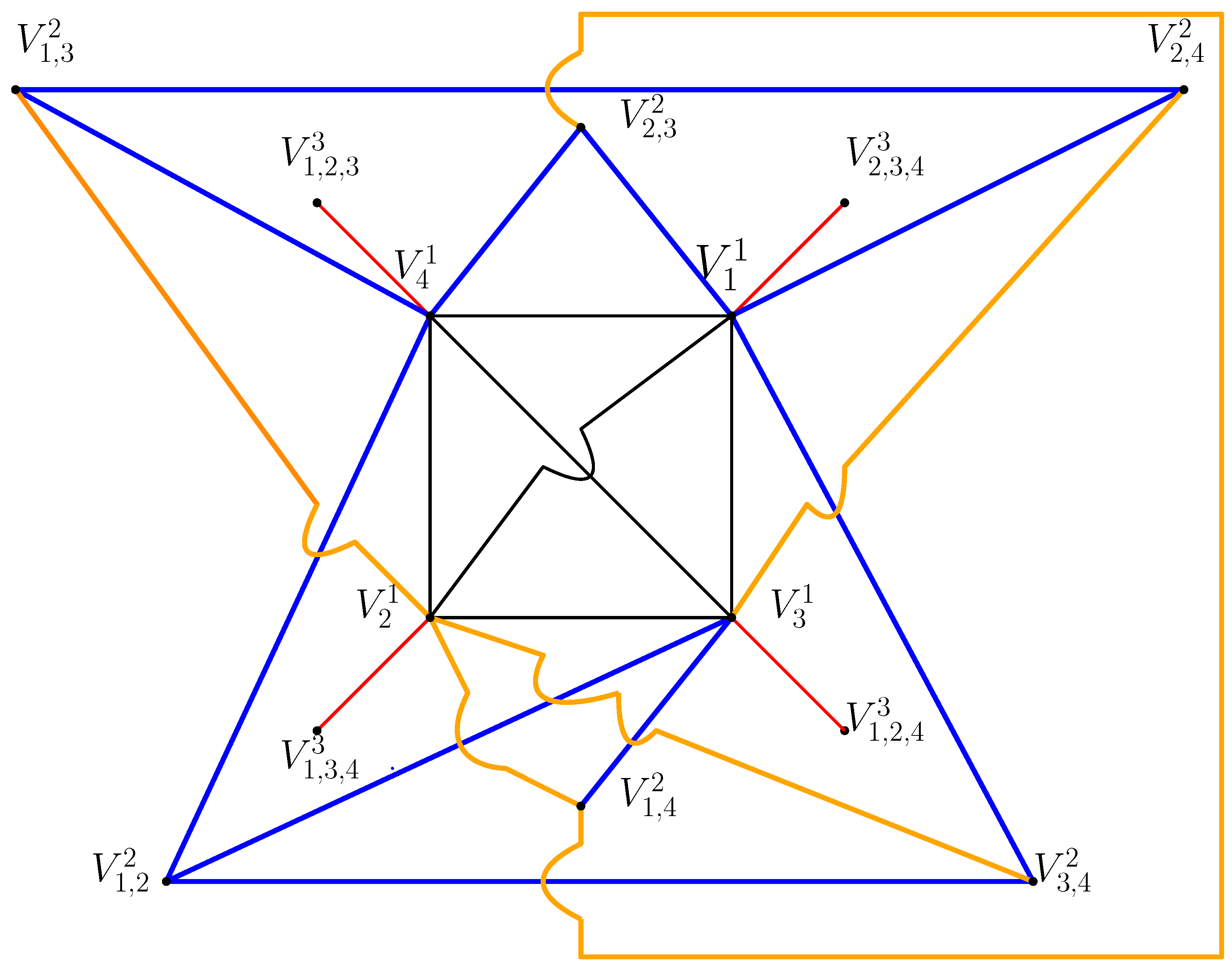

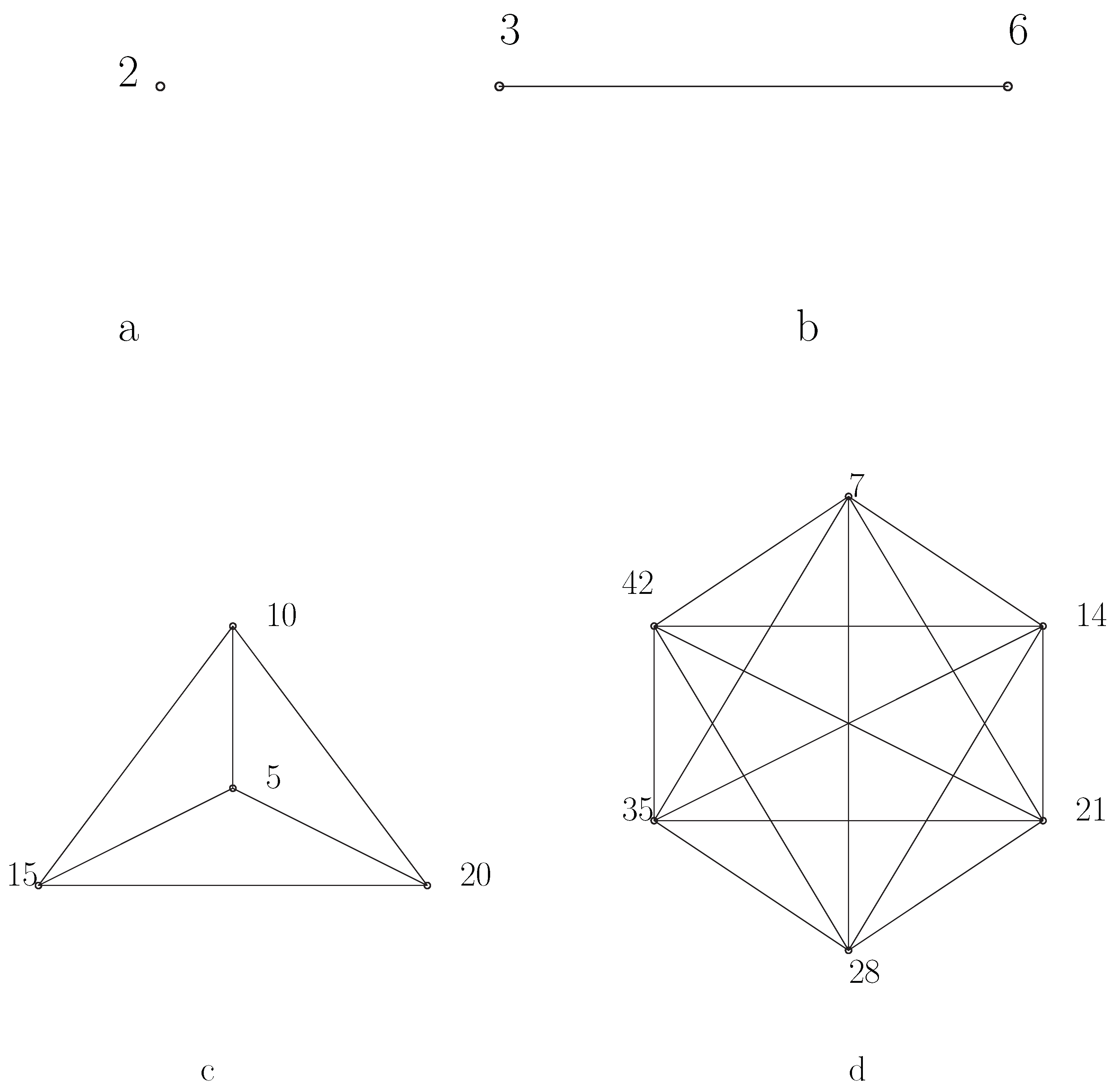

Let us considerbe the set of all non-zero zero divisors of . Then by the properties of zero divisor we know that for each i,Since 0 is always a zero divisor element,where is a Euler’s totient function. It follows thatTherefore,where V is the set of vertices of . Now, one of the way to determine the zero-divisors elements of is to solve for the incongruent solution of the congruent equation.where k is a non-zero zero divisor element of .Now, equation (1) has a solution asWe may assume thatThencan be written asNow, from equation (2)Therefore,for some l. We note that for incongruent solution, l must be less than . It follows thatThus the incongruent solutions of equation (2) are given by those integers which are multiples of and less than . Similarly, the incongruent solutions of equation (3) are given by those integers which are less than and multiples of . For instance, if =3 and =7, then the solutions of these two congruence equations (2) and (3) will be multiples of 7 and 3, i.e., and , respectively. Now, let us consider = all the incongruent solutions of equation (2) and = all the incongruent solutions of equation (3). ThenSince and are distinct primes,Moreover, no two vertices in are connected for each i= and every vertices of are connected to every vertices of . If possible, assumeare connected, then, we haveSincewhere . It follows thatSince is prime and , we have , which is a contradiction that and are distinct primes. Sincewe have is a complete bi-partite graph, i.e.,If any of the prime or is 2, say, , then and the only vertex in must have an edge with every vertex in and so is a star graph.

- 2.

- To prove this we consider an example as shown in the Figure 2. Since = is a bi-partite graph diameter and chromatic number,

- 3.

- Radius, rad( is the minimum eccentricity of all the vertex of which is 2.

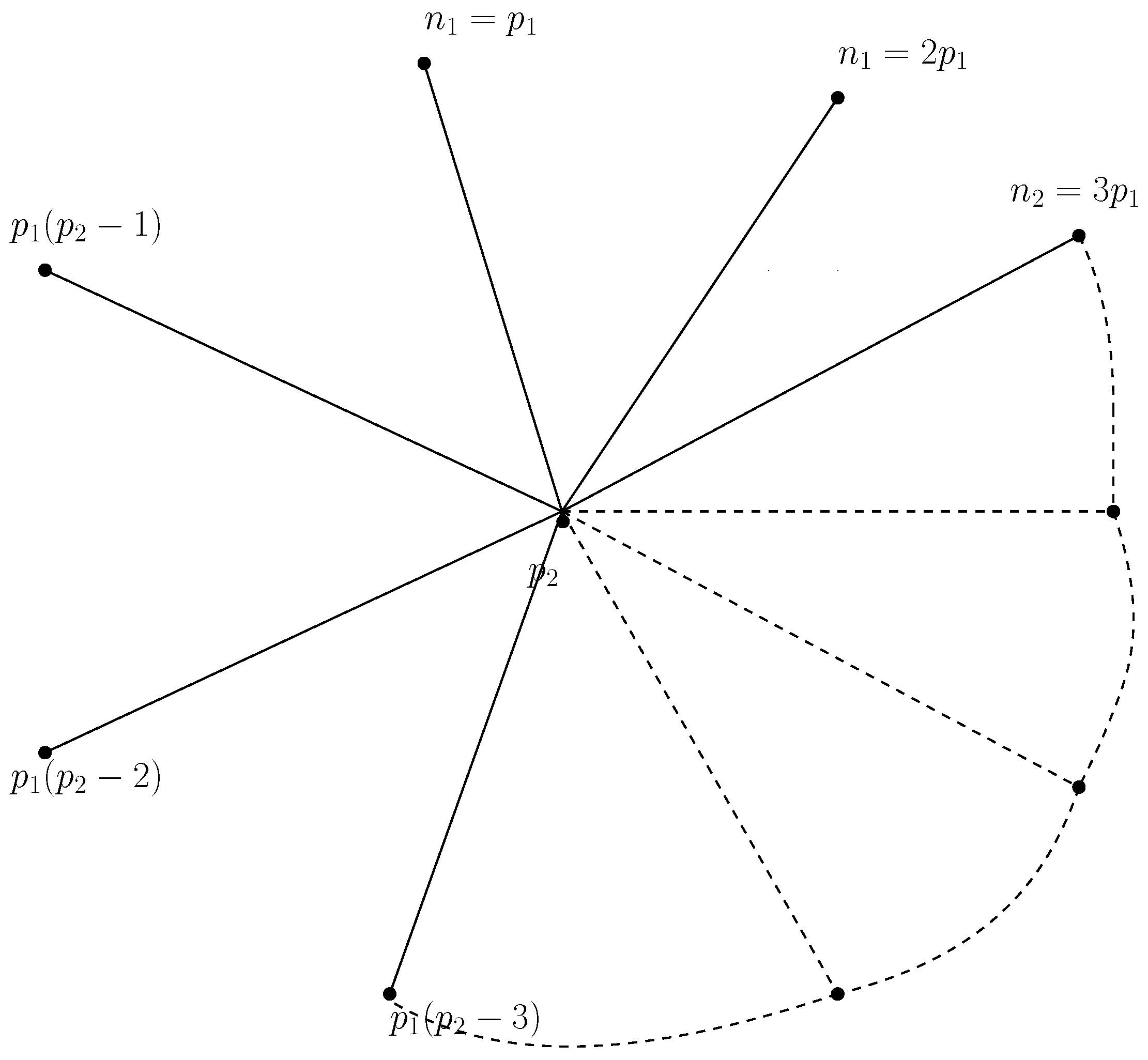

- (1)

- (2)

-

and so on. After steps, we have

- (3)

- .

4. Algorithm to Determine , when n Is Square Free

5. Illustrated Examples

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. O. Aguilar, An Introduction to Algebraic Graph Theory, State University of New York, Geneseo.

- S. Akbari, H. R. Maimani, and S. Yassemi. When a zero-divisor graph is planar or complete r-partite graph. J.Algebra 2004, 274, 847–855. [Google Scholar]

- S. Akbari and A. Mohammadian. Zero-divisor graphs of non-commutative rings. J. Algebra 2006, 296, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. F. Anderson and A. Badawi. On The Zero-Divisor Graph Of A Ring. Communications in Algebra 2008, 36, 3073–3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. F. Anderson, J. Fasteen, and J. D. LaGrange. The subgroup graph of a group. Arabian Journal of Mathematics 2012, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. F. Anderson and P.S. Livingston. The zero-divisor graph of a commutative ring. Journal of algebra 1999, 217, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. F. Anderson and S. B. Mulay. On the diameter and girth of a zero-divisor graph. Journal of pure Applied Algebra 2007, 210, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. D. Anderson and M. Naseer. Beck’s coloring of a commutative ring. J. Algebra 1993, 159, 500–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. Beck. Coloring of commutative Rings. journal of Algebra 1988, 116, 208–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. A. Bondy and U. S. R. Murty, Graph Theory with applications, American Elsevier, New York, 1976.

- F. Buckley and M. lewinter, A Friendly Introduction to Graph Theory, Prentic-Hall, (2003).

- S. Chattopadhyay, K. Lochan Patra and B.K. Sahoo. Laplacian eigenvalues of the zero divisor graph of the ring Zn. Linear Algebra and Its Applications, 2020; 584, 267–286. [Google Scholar]

- T. T. Chelvam, P. Vignesh, and G. Kalaimurugan. On zero-divisor graphs of commutative rings without identity. Journal of Algebra and its Application 2020, 12, 226. [Google Scholar]

- F. Demeyer and K. Schneider. Automorphisms and zero divisor graphs of a commutative rings. International J. Commutative Rings 2002, 1, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- N. Jafari Rad and S. H, Jafari. A Characterization of Bipartite Zero-Divisor Graphs. Canadian Mathematical Society 2014, 57, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- N. Jafari Rad, S. H. Jafari, and D. A. Mojdeh. On Domination in Zero-Divisor Graphs. N. Jafari Rad, S. H. Jafari, and D. A. Mojdeh 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D. Lu and Tongsuo Wu, On bipartite zero-divisor graphs, Elsevier, Discrete mathematics, 309, 755-762, (2009).

- I. Niven, H. S. Zukerman, and H. L. Montgomery. An introduction to the theory of Numbers; Wiley India(p) Ltd, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- S. P. Redmond. The zero-divisor graph of a non commutative ring. Internat. J. Commutative Rings 2002, 1, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- D. Sinha and B. Kaur. Beck’s Zero-Divisor Graph in the Realm of signed Graph. National Academy Science Letters 2020, 3, 263. [Google Scholar]

- D. B. West, Introduction To Graph Theory, Prentice Hall of India Pvt. Ltd, (2003).

| Equations | Solution sets | Partition sets | Edges formations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equations | Solution sets | Partition sets | Edges formations |

|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).