1. Introduction

As living standards have improved, so too has public awareness of health issues. This has led to a corresponding increase in the value of big data research in the medical field. Furthermore, social changes, including population growth and an ageing population, have accelerated the rapid development of the medical industry, resulting in a significant increase in the volume of medical data. Statistical evidence indicates that approximately 30% of global data is derived from the healthcare sector. Projections suggest that the compound annual growth rate of healthcare data will reach 36% by 2025, a rate that is considerably higher than that observed in other major industries, including manufacturing, financial services, and multimedia entertainment [

1]. A series of measures have been implemented by the state and the government with the objective of establishing medical data systems, enhancing citizens' health awareness, promoting related service support, improving the accuracy of testing equipment, promoting the development of emerging medical industries, and popularising smart wearable devices. These measures are contributing to the rapid growth of medical big data. These initiatives and emerging technologies have significantly driven the advancement of medical big data [

2].

The term "medical big data" encompasses a broad range of information pertinent to human health, including data generated by traditional medical institutions and diverse data sets emerging in the realm of novel health domains. As the fundamental element of the electronic medical record, the electronic medical record (EMR) encompasses the comprehensive data accumulated from the patient throughout the medical process [

3]. This includes information such as basic personal details, examination outcomes, disease progression records, medical directives, surgical care documentation, and insurance particulars. This information provides a substantial repository of historical data pertinent to the provision of medical services, thereby offering invaluable support for clinical decision-making.

The National Institutes of Medicine defines an electronic medical record as an electronic patient health record that provides users with real-time access, alerts, prompts, and decision support, thereby enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of medical services. In addition to electronic medical records, clinical research data and laboratory data represent significant sources of medical big data, particularly high-capacity data such as medical imaging and genetic data [

4]. These data not only provide a rich foundation for medical research but also offer substantial support for the optimisation of clinical treatment plans and the translation of medical achievements.

The current research into medical big data has demonstrated considerable potential for providing insights into the medical field and promoting innovation in diagnosis and treatment methods. The effective utilisation of medical data can facilitate a significant enhancement in the precision of disease diagnosis and the calibre of medical services. Nevertheless, the process is not without its challenges, with a number of issues that require immediate attention to ensure the optimal application of data and the efficacy of the model [

5]. Furthermore, there is a paucity of evidence regarding the efficacy of clinically assisted diagnostic models. As the use of medical data becomes more widespread, the inherent complexity of the data itself is increasing, necessitating the development of more sophisticated network models for problem-solving.

In order to address issues such as inadequate feature expression or data dimensionality issues in medical data, researchers must construct intricate deep learning models. However, these complex models frequently necessitate a substantial quantity of data samples and computational resources during the learning process. In the event that the quantity of medical data is insufficient, the model may be unable to adequately capture the intricate relationships between features, which could subsequently impact its performance. It is therefore important to determine how to balance the amount of data and the complexity of the model in order to ensure that the model is able to fully learn and demonstrate good diagnostic ability.

2. Related Work

In a previous study, Kim et al. [

6] proposed a novel multimodal superposition denoising autoencoder method for the purpose of addressing missing data in personal health records (PHRs). The method involved the design of an encoder based on a seven-layer neural network (NN) and training with 146,680 samples. The encoder is capable of effectively interpolating missing data in multimodal scenarios and filtering out a small amount of noise. Upon reaching approximately 25% missing data in the dataset, the proposed method demonstrated an accuracy of 0.9217, which outperformed that of comparable algorithms. J6msten et al. [

7] put forth a LinCmb imputation method for DNA microarrays, which demonstrated efficacy in the imputation of liver DNA microarray and liver cancer DNA microarray deletion data.

Additionally, Dong et al. [

8] proposed the utilisation of generative adversarial networks (GANs) for the imputation of data loss. This approach involved the training of a model using tens of thousands of data samples, with the objective of generating virtual data that exhibited a distribution similar to that of the actual data. This was achieved through the adversarial learning of generators and discriminators. However, the learning process of GANs necessitates a greater quantity of training data than that required by traditional neural networks, thereby rendering the training of the model more challenging.

Wang et al. [

9] put forth a multi-omics graph convolutional network (MOGONET) model for the integration of mRNA expression data, DNA methylation data, and miRNA expression data with the objective of identifying biomarkers that are closely associated with disease. Chen et al. [

10] put forth a prognosis prediction model for breast cancer based on clinical data and gene expression data. This model combined an attention mechanism with a deep neural network for the purpose of feature selection and extraction, thereby enabling the prediction of breast cancer prognosis.

Furthermore, Yang et al. [

11] devised a multimodal diagnostic model for clinical data and breast cancer medical image data. The complexity of the clinical data was reduced through the application of random forest feature selection and logistic regression classification. The model was then combined with a deep neural network to extract medical imaging features, and finally, the risk of recurrence and metastasis of HER2-positive breast cancer was predicted. Alizadeh et al. [

12] employed a multimodal data fusion and diagnostic approach for coronary artery disease, initially extracting features from ultrasound and echo data, then ranking the significance of these features through dimensionality reduction and classifier, and finally inputting a machine learning classifier for disease classification. Golovinkin et al. [

13] investigated prediction of early myocardial infarction complications, developed an intelligent evaluation system, and reduced the dimensionality of high-dimensional cardiovascular detection data through feature selection. They then combined this with a multi-layer deep network classification model to achieve the classification of myocardial infarction complications, with an average accuracy of more than 90%.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Text Encoding and Pre-Training

In this section, we utilise GPT-4 to encode medical texts, thereby enhancing its capacity to comprehend data within the medical domain. GPT-4 functions as an autoregressive generative model, generating a probability distribution for the subsequent word based on the input sequence. Assuming that the input sequence is , where each represents the input text at the -th time step, GPT-4 employs a self-attention mechanism to model the entire sequence. The objective of the model is to generate a probability distribution for the next word, given the input sequence at the current moment and the hidden state at the previous moment.

In the case of medical texts, we employ additional techniques to enhance GPT-4's comprehension of medical terminology and context. These involve pre-trained fine-tuning strategies based on medical domain knowledge. For illustrative purposes, we may consider the use of an embedding layer with a glossary of medical terms in the medical field. For each word, the embedding layer maps it to a vector space, as defined by Equation 1:

where

represents the word embedding matrix. The objective of fine-tuning is to optimise the parameters of the GPT-4 model by minimising the following loss functions, as illustrated in Equation 2:

The model is trained on a substantial corpus of medical texts, thereby acquiring the capacity to comprehend and produce medical-related content in a manner that is consistent with the conventions of the medical field. Through fine-tuning, the model is capable of optimising its weights in accordance with the requirements of a particular domain, thereby enhancing its comprehension of medical terminology. To illustrate, specific medical terms such as "chemotherapy" or "antibiotics" may be encountered with regularity in a generic corpus. However, their meaning and context may diverge in the medical context. Fine-tuning enables the model to adapt to this change and thereby become more accurate in the context of medical applications.

The issue of missing data is a pervasive one in the field of healthcare data. In order to ensure the most effective filling of these missing values, a contextual adaptive filling strategy was designed. Let us consider a scenario in which the missing data to be filled in is a sequence,

, which contains some missing fields. The relevant data from the historical record is then used to populate the missing fields. Let us initially define the similarity measure

between missing records and historical records, which is commonly employed as cosine similarity (as illustrated in Equation 3).

where

represents the missing value recorded on the

feature, while

represents the

-th recorded value on the same feature. By calculating the similarity, it is possible to assign a weight,

, to each history, as expressed in Equation 4:

Subsequently, the populated records are generated through application of a weighted average, as expressed in Equation 5:

The objective of this formula is to facilitate the utilisation of historical data to the greatest extent possible in instances where data is absent. Similarity metrics ensure data consistency and relevance when populating historical records. To illustrate, in the event that the absent data exhibits a high degree of similarity to historical instances, the populated data will be deemed more medically valid.

3.2. Hierarchical Attention Mechanisms

In the context of processing lengthy textual data, GPT-4 may potentially encounter challenges related to information loss or elevated computational complexity. To address this issue, we propose a hierarchical attention mechanism that divides lengthy texts into multiple sub-blocks, each comprising an independent unit of medical information. Let us suppose that the lengthy text is divided into

sub-chunks {

}, each of which is represented by a sub-block. These sub-blocks can be encoded with GPT-4 by Equation 6:

Subsequently, a cross-sub-block attention mechanism is employed for the aggregation of information. Firstly, the similarity between the sub-blocks is calculated, and an attention weight is assigned to each sub-block, as illustrated by Equation 7:

where

represents the matching score between two sub-blocks, while

denotes a matrix of learned parameters. In conclusion, the weighted representation across sub-blocks is given by Equation 8:

In order to enhance the model's capacity to adapt to a diverse range of inputs, we employ data augmentation techniques to expand the training data set. Let us consider a training set,

, which is defined as a sequence of elements

. The objective of data augmentation is to generate training examples that are semantically equivalent. The generation of enhanced data is achieved through the utilisation of a methodology analogous, as illustrated by Equation 9:

The model's enhanced capabilities facilitate greater generalisation in response to a range of input types. The introduction of data augmentation can facilitate the introduction of additional semantic changes, thereby enhancing the robustness of the model.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

The MIMIC-III (Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care) dataset was employed in the experiment, which is a genuine dataset that is frequently utilised in medical data research, particularly for electronic health record (EHR) related analysis and model training. The MIMIC-III dataset comprises clinical data from over 40,000 patients, encompassing basic demographic information, diagnostic records, laboratory test results, medication usage, intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization records, and other crucial medical history data.

In the experiment, the learning rate warm-up strategy was employed to circumvent gradient explosion, and the batch size of the model was set to 64 to guarantee the efficacy and stability of the training process. In regard to the fusion of multi-modal data, we have devised independent processors for the processing of different modal data, with the text data undergoing processing by the GPT-4 encoder. Model was trained for 100 iterations, with each layer utilising 16 attention heads, a 1024-dimensional embedding space, and 4096-dimensional hidden layer.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

To evaluate the performance of the proposed GPT-4 model, we compare it with several benchmark methods, including: the Multimodal Superposition Denoising Autoencoder (MSDA), which uses a seven-layer neural network to process missing data and filter out noise; Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which generate dummy data to fill in missing values; Multi-omics Graph Convolutional Network (MOGONET) for integrating multiple omics data to identify disease-related biomarkers; and the Breast Cancer Prognostic Prediction Model (ADNN), which combines attention mechanisms and deep neural networks for feature extraction and prognostic prediction.

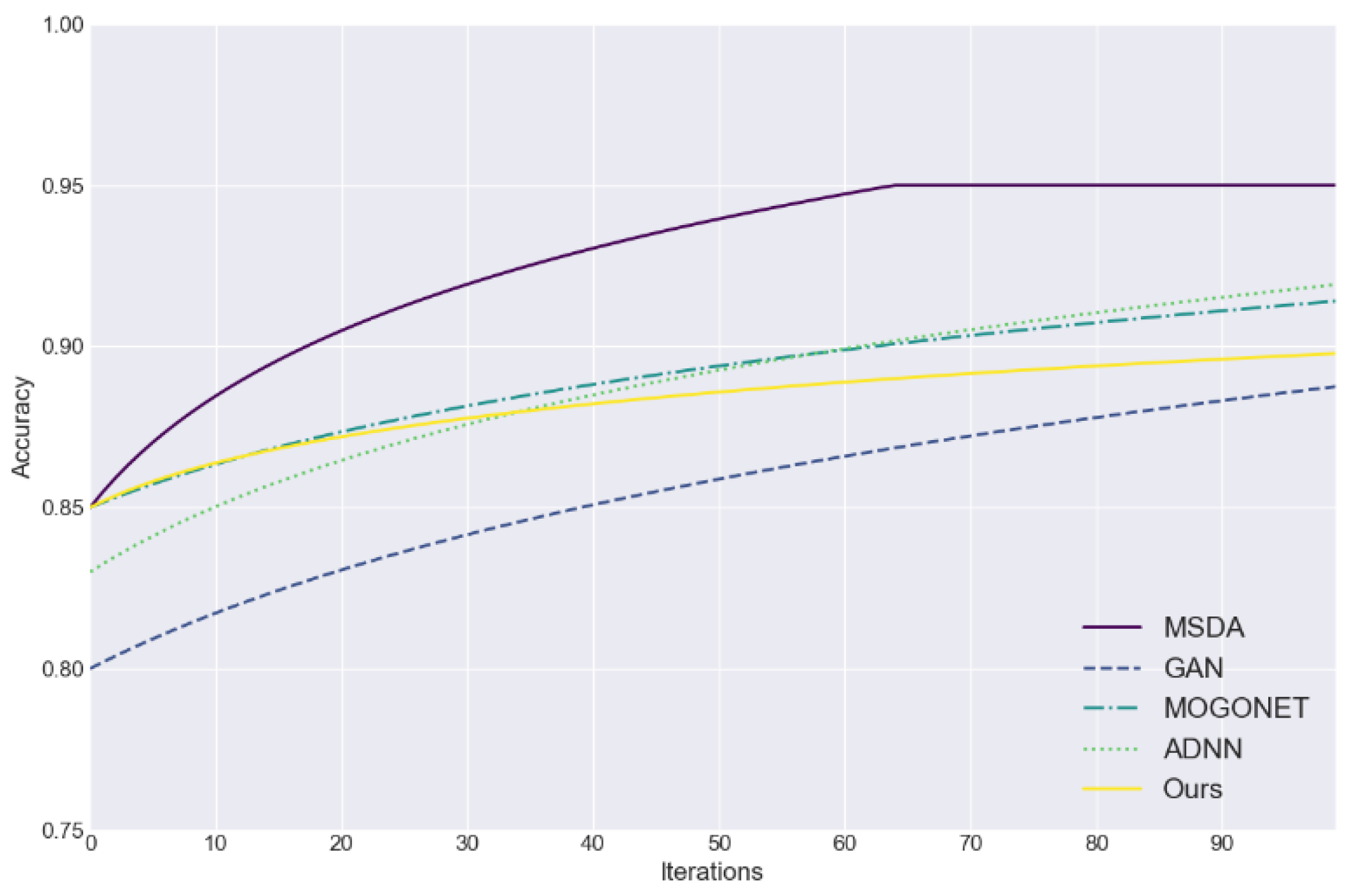

Figure 1 assesses the efficacy of five data imputation methods (MSDA, GAN, MOGONET, ADNN, and the proposed approach) in addressing the challenge of incomplete medical data. The figure plots the accuracy of each method as a function of the number of iterations, providing a visual representation of their performance. The accuracy serves as an effective evaluation index, providing a straightforward means of assessing the efficacy and convergence speed of each method in the process of filling in the missing data.

Figure 1 illustrates that the proposed method rapidly attained an accuracy rate exceeding 85% in the initial iteration and demonstrated consistent performance in subsequent stages.

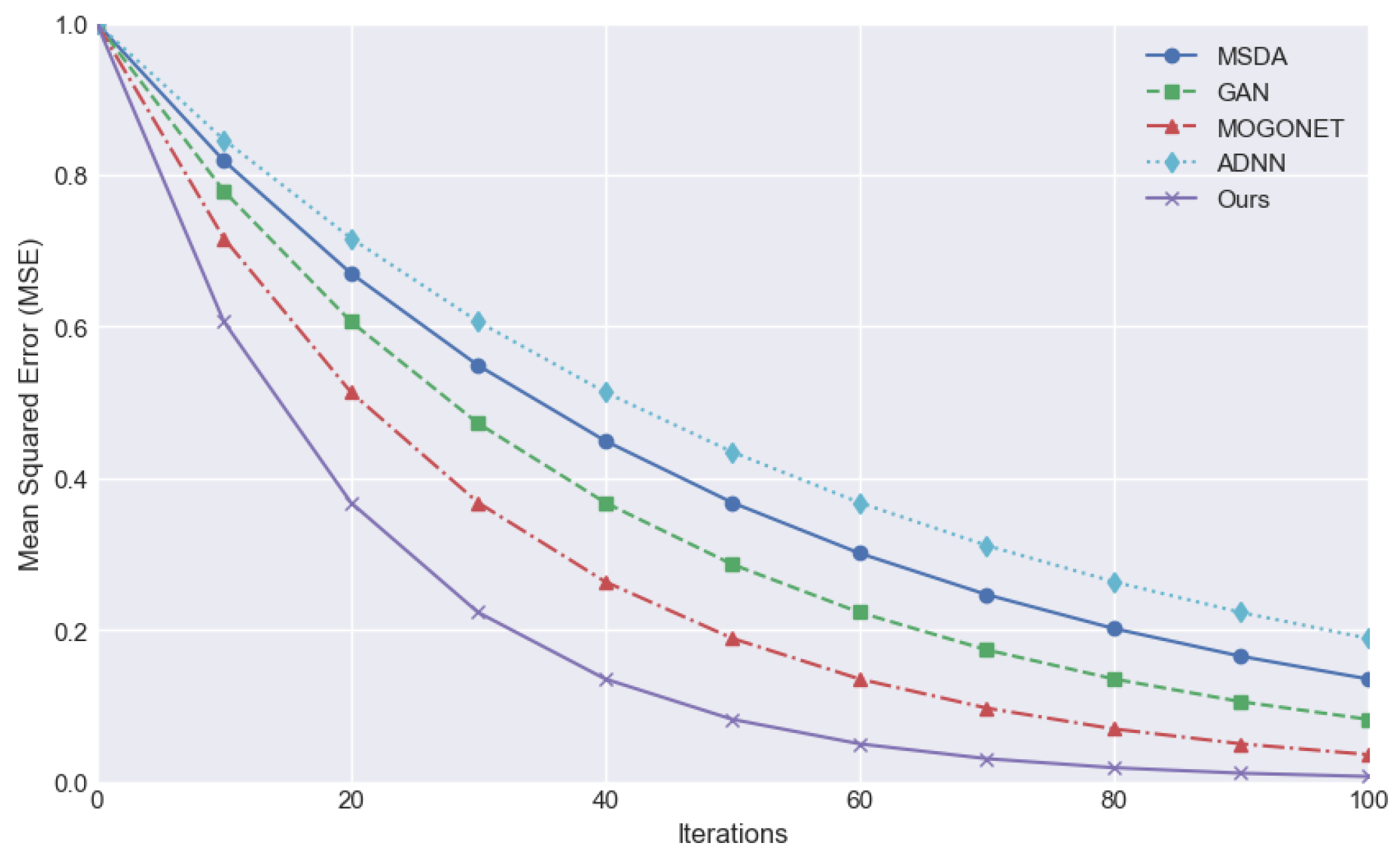

The mean square error (MSE) is employed as an evaluation index to quantify the mean deviation between the predicted value and the true value. A smaller value indicates a superior predictive efficacy of the model, denoting a greater capacity to align with the data.

Figure 2 compares the downward trend of MSE in the iteration process of different methods and demonstrates that the MSE of the proposed method decreases rapidly from the initial stage and converges to the lowest value in the number of earlier iterations, indicating superior training efficiency and stability. In contrast, alternative methodologies may also result in a gradual reduction of MSE. However, the decline rate is typically slower, and the MSE level is frequently higher than that of the proposed method at the same iterations.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the GPT-4-based multimodal medical data processing method proposed in this study is superior to the existing technology in terms of missing data processing, accuracy and mean square error reduction. Experimental results show that the proposed method can converge quickly and maintain high accuracy, and has strong data processing ability. In the future, with the accumulation of more medical data and the development of technology, our method is expected to be further optimized to improve the application effect of electronic health record systems, and support the improvement of medical data analysis and prediction models.

References

- Li, Rui, Fenglong Ma, and Jing Gao. "Integrating multimodal electronic health records for diagnosis prediction." AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 2021. 2022.

- Xu, Zhen, David R. So, and Andrew M. Dai. "Mufasa: Multimodal fusion architecture search for electronic health records." Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 35. No. 12. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Soenksen, Luis R., et al. "Integrated multimodal artificial intelligence framework for healthcare applications." NPJ digital medicine 5.1 (2022): 149. [CrossRef]

- Wornow, Michael, et al. "The shaky foundations of large language models and foundation models for electronic health records." npj Digital Medicine 6.1 (2023): 135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Chaohe, et al. "M3care: Learning with missing modalities in multimodal healthcare data." Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2022.

- Kim, Joo-Chang, and Kyungyong Chung. "Multi-modal stacked denoising autoencoder for handling missing data in healthcare big data." IEEE access 8 (2020): 104933-104943. [CrossRef]

- Jörnsten, Rebecka, et al. "DNA microarray data imputation and significance analysis of differential expression." Bioinformatics 21.22 (2005): 4155-4161. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Weinan, et al. "Generative adversarial networks for imputing missing data for big data clinical research." BMC medical research methodology 21 (2021): 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Tongxin, et al. "MOGONET integrates multi-omics data using graph convolutional networks allowing patient classification and biomarker identification." Nature communications 12.1 (2021): 3445.

- Chen, Hongling, et al. "Attention-Based Multi-NMF Deep Neural Network with Multimodality Data for Breast Cancer Prognosis Model." BioMed research international 2019.1 (2019): 9523719. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jialiang, et al. "Prediction of HER2-positive breast cancer recurrence and metastasis risk from histopathological images and clinical information via multimodal deep learning." Computational and structural biotechnology journal 20 (2022): 333-342. [CrossRef]

- Alizadehsani, Roohallah, et al. "Non-invasive detection of coronary artery disease in high-risk patients based on the stenosis prediction of separate coronary arteries." Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 162 (2018): 119-127. [CrossRef]

- Yavru, İsmail Burak, and Sevcan Yılmaz Gündüz. "PREDICTING MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION COMPLICATIONS AND OUTCOMES WITH DEEP LEARNING." Eskişehir Technical University Journal of Science and Technology A-Applied Sciences and Engineering 23.2 (2022): 184-194.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).