Introduction

According to World Health Organisation (WHO) documents, chronic non-communicable diseases, including physical and mental illnesses, unintentional injuries and violence, and disabilities, are the main burden of disease today. Among the above-mentioned diseases, malignant diseases are in second place in terms of burden and mortality in the Republic of Croatia (Croatia) and in the world, and great efforts are being made to raise public awareness of this issue and to make the response to the National Prevention Programmes (NPP) as good as possible [

1,

2].. The NPPs have been implemented for about 15 years, but unfortunately the response is still unsatisfactory [

2]. Currently, screening for early detection of breast cancer, cervical cancer and colorectal cancer is carried out in Croatia, as these diseases are among the leading causes of death in the Republic of Croatia, and recently the National Screening Programme for early detection of lung cancer was introduced. Screening for cervical cancer has been carried out continuously for several years and is currently being reorganised and opportunistic screening is carried out in January, which is Cervical Cancer Awareness Month [

1]. Breast cancer in women and colorectal cancer in both sexes are the main causes of mortality and disability in the Republic of Croatia [

3]. Although breast cancer can be detected relatively early and therefore treated more successfully, there are a large number of women in whom the disease is detected at an advanced stage, where the treatment results are less successful and the patients' quality of life is lower [

4]. The target group for this programme is women between the ages of 50 and 69. The screening method is mammography, which is carried out every two years and covers at least 70% of the general population [

5]. The first cycle of the programme was carried out between the end of 2006 and the end of 2009. In the first cycle, a total of 720982 women were invited and 331609 women had a mammogram. The participation rate varied depending on the county; in the Republic of Croatia, the overall rate was 63%. The proportion of suspicious findings was 1.03% and the proportion of detected malignant breast diseases was 0.50%. The second cycle of the programme took place from the beginning of 2010 to the end of 2011. 680552 women were invited and 295605 women underwent a mammography examination (&). The turnout was 57 %. 928 cases of cancer were detected. The third cycle began at the end of 2011 and lasted until May 2014, the fourth began in May 2014 and was completed in autumn 2016. So far, six cycles have been completed with women calling, and the seventh is underway. [

2,

7,

8,

9]

One of the most important tasks of health professionals, especially those in primary health care, is the prevention of diseases, i.e. the promotion and maintenance of the health of all citizens of the Republic of Croatia. Their task is also to encourage citizens to participate in the NPP so that coverage is as high as possible. In this way, there is a greater chance that malignant diseases will be detected at an early stage of the disease, when the cure rate is higher. Some of the reasons for lower uptake may include poorer availability of information, unavailability of tests, unclear instructions given to the insured, fear of disease or unpleasant tests that may follow a potentially positive finding.

The aim of this thesis is to investigate whether and to what extent female health personnel of Istria County (IŽ) employed in public health facilities respond to the NPP they promote, more precisely to the National Programme for Early Detection of Breast Cancer (hereafter: NP), or what are the reasons for their lack of response, if any.

The following objectives and associated hypotheses are set:

C1: To determine the response rate of health professionals in Istria County in the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme.

C2: To determine the differences in the response of healthcare professionals in Istria County compared to the response of the general female population to the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme in the Republic of Croatia.

C3: To identify the main reasons for the lack of response of healthcare professionals to the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme.

In accordance with the stated objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1: The response rate of healthcare personnel in Istria County to the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme is less than 65%.

H2: There is no statistically significant difference in the participation of healthcare personnel in the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme in the Republic of Croatia compared to the participation of the general female population.

H3: The expected reason for the lack of response is the fear of an unpleasant examination or malignant breast disease.

Subjects and Methods

This study is a quantitative cross-sectional study conducted on an appropriate sample of respondents. The respondents were medical staff aged between 50 and 72 years employed in public healthcare facilities in Iž. The survey was conducted in March and April 2024. A total of 102 respondents took part in the study.

A questionnaire developed exclusively for the needs of this study was used for the survey. The questionnaire was created via a Google form and sent by e-mail to the public health institutions of IŽ. The questionnaire consists of a total of 13 questions. The first 5 questions relate to the respondent's socio-demographic data, 2 of which are open-ended (age and occupation), 3 questions relate to personal and family history of breast cancer and 5 questions relate to response to NP, 3 of which are mandatory and 2 of which are optional (only if the answer to the previous question is "yes"). The introduction to the survey states that the survey is anonymous and that participation is voluntary. It took about 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

For the statistical analysis, the methods of tabular and graphical representation were used, which show the structure of the answers to the survey questions. Microsoft Excel and the computer programme Statistica 14.0.0.15 (TIBCO Software Inc.) were used for data processing. All tests were performed with a significance level of 0.05.

Subjects participated in the study voluntarily and could withdraw from completing the questionnaire at any time. The research did not jeopardise the integrity and privacy of the respondents as individuals and its conduct was in accordance with basic ethical and bioethical principles – fairness, charity, harmlessness and personal integrity, taking into account the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The sample consists of 102 respondents with an average age of 57.71 years. More than 50 % of the respondents in the sample are nurses (51.0 %), and just over a quarter are doctors (28.4 %). The remainder (21%) of the sample consists of physiotherapists, laboratory technicians, sanitary technicians, radiologists and pharmacists. Most of the respondents have completed higher education, while only 39.2% of respondents have a secondary school education. Within the completed higher education, there are an equal number of respondents with a completed undergraduate degree (15.7%), with a completed graduate degree (17.6%) and with a completed graduate degree (doctor) (16.7%). Some of the respondents who are physicians stated that they have completed a university degree, which explains the disparity between the number of female physicians and those who have completed a university degree for a physician (

Table 1).

In the vast majority of cases, respondents live with their immediate family (spouse and/or children), while very few live in another form of community (2.9 %) or in an extended family (8.8 %). The proportion of respondents who live alone is 16.7%. The majority of respondents live in the city (59.8%), with the fewest, 15.7%, living in the countryside.

Only one in ten respondents in the sample did not breastfeed (10.8%), and only slightly more, 14.7%, did not give birth. Three quarters of the respondents were breastfed. In terms of family history, almost a quarter of respondents (23.5%) had a family history of malignant breast disease. Only 4.9 of the respondents themselves had a history of malignant breast disease

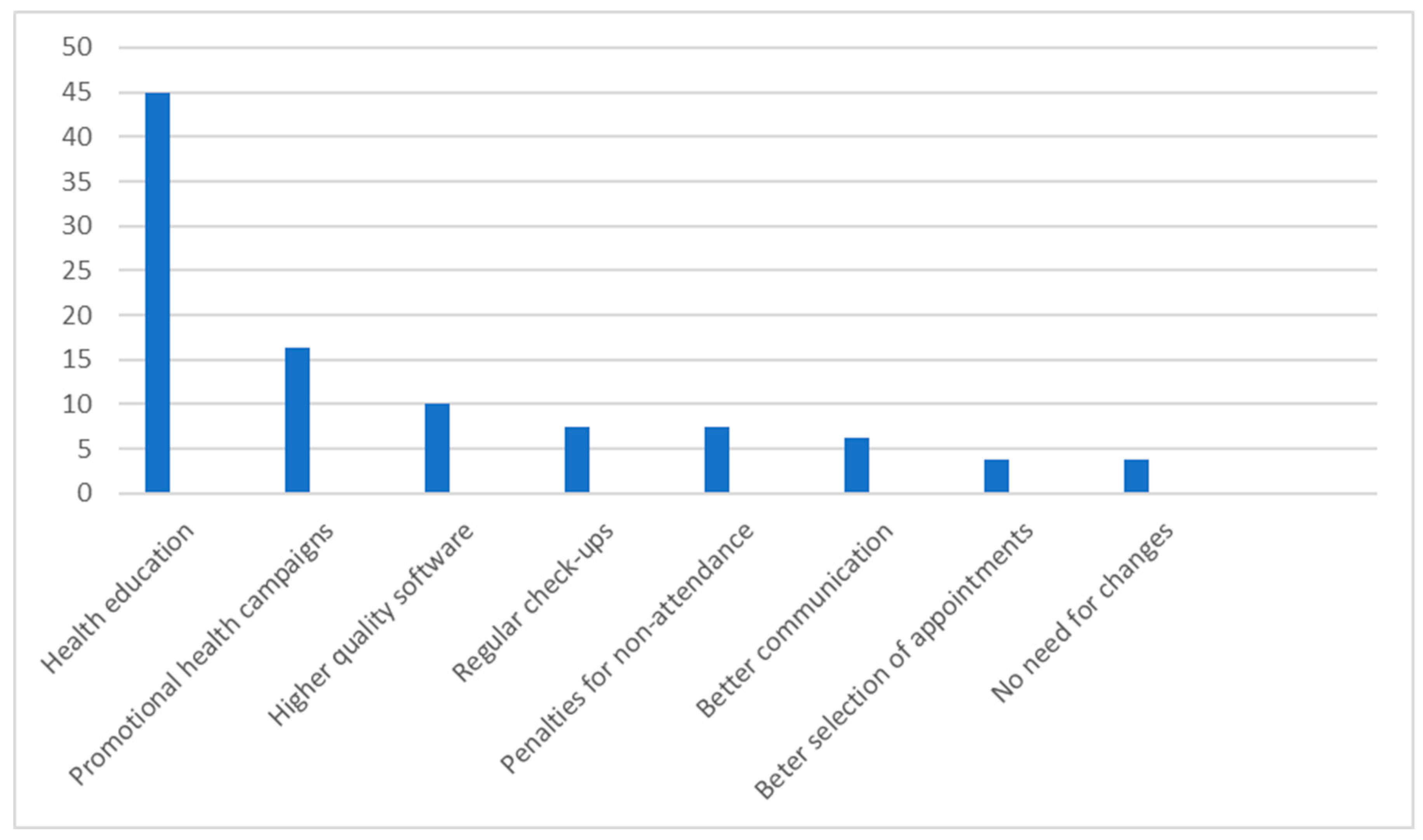

Of the respondents who made their suggestions (

Figure 2), 45.0 % see room for an increasing in response, particularly in long-term work with young people through health education. Greater information and advertising in the public information media of the National Park in the Republic of Croatia would increase the response rate, according to 16.3% of respondents, while 7.5% of them are in favour of mammography being carried out as part of regular systematic examinations, but also of creating a system of sanctions for non-response. Other suggestions include updating the system (10.0%), better communication (6.3%) and a wider choice of terms (3.8%). A fifth of respondents (22.2%) made no other suggestions for improving the response.

Testing the hypotheses

H1: The response rate of the ZD IŽ to the National Breast Cancer Screening Programme is below 65%.

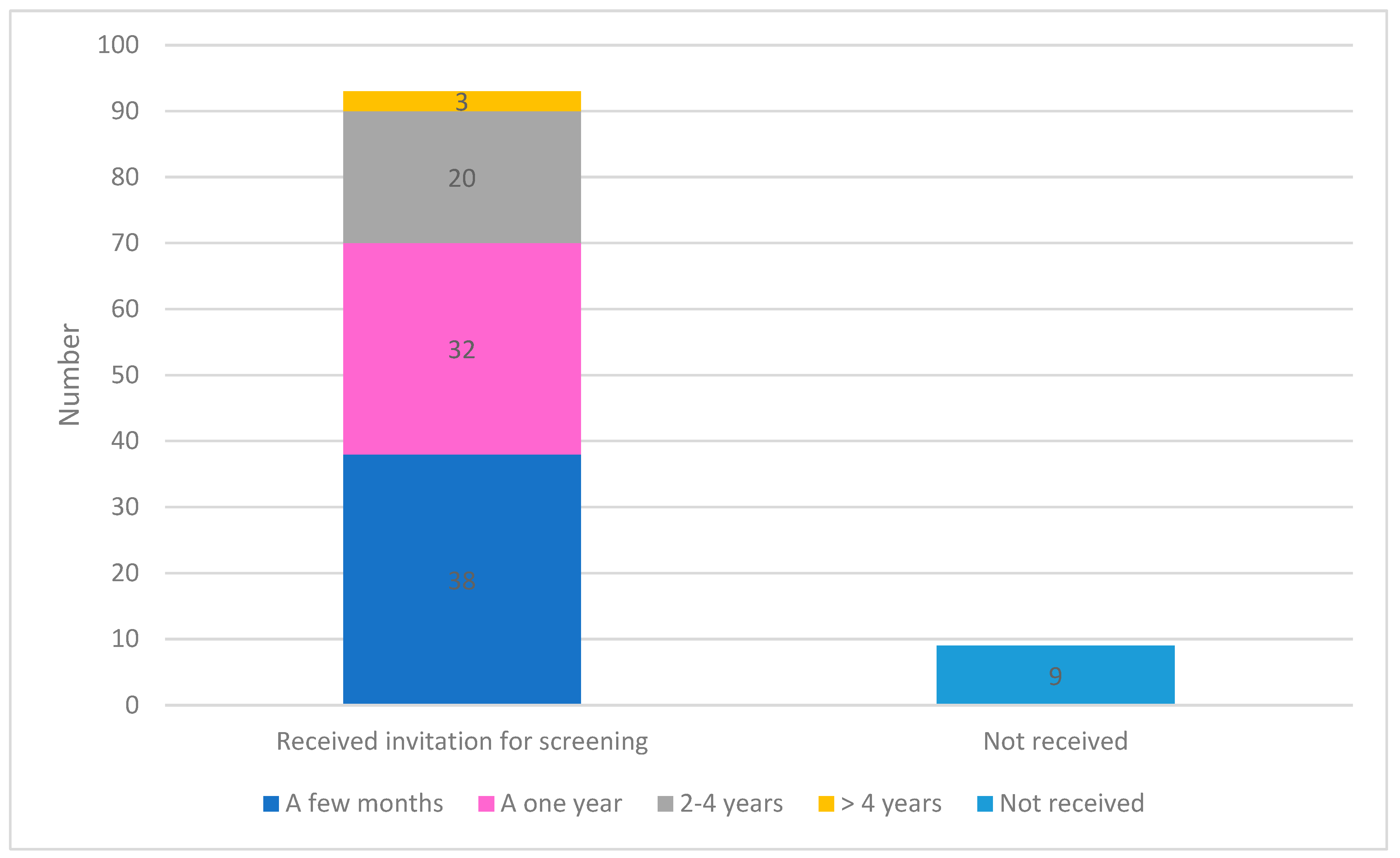

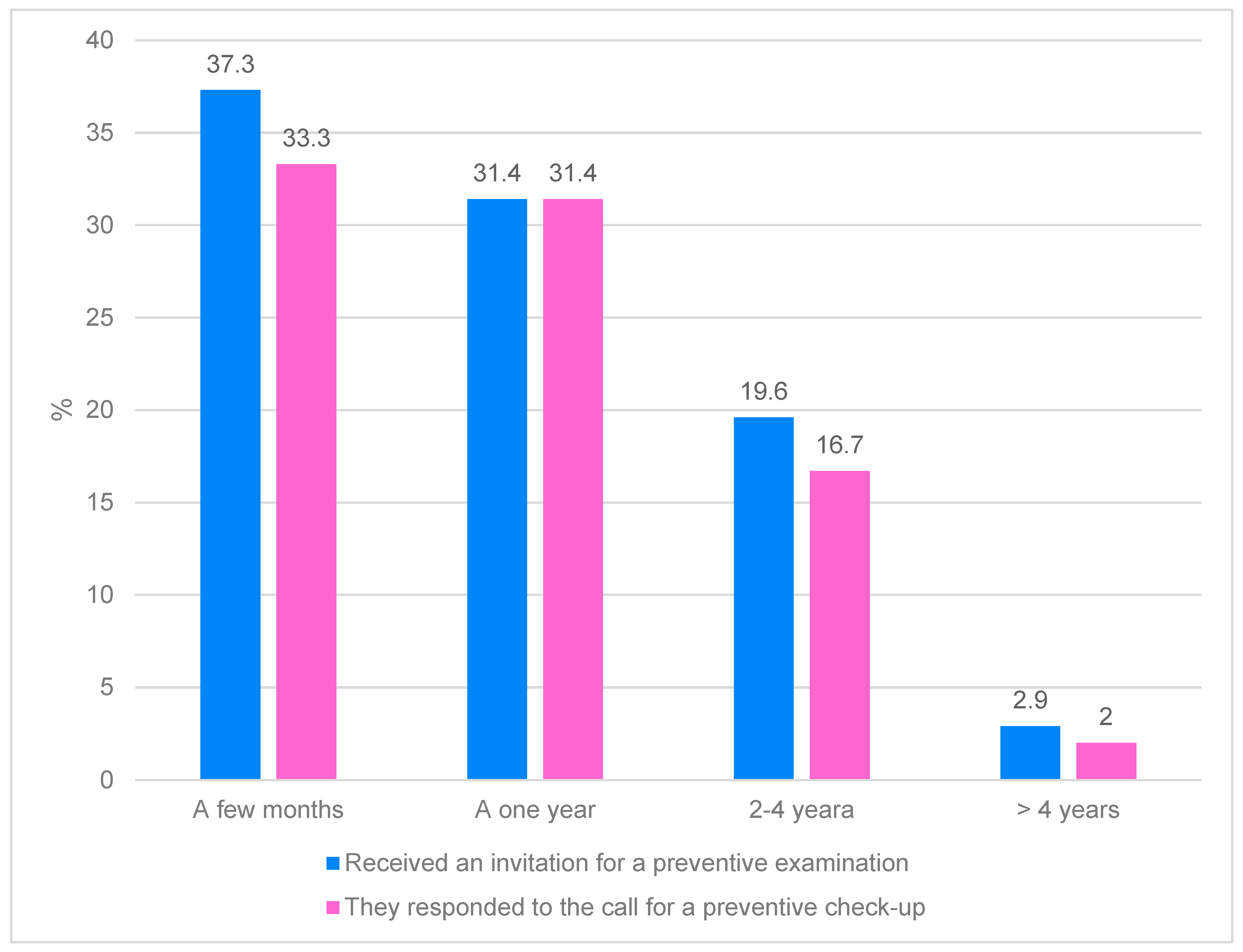

91.2% of respondents received an invitation to the NP. The NP has been carried out more systematically in recent years, so that more than a third of respondents (37.3%) received this invitation a few months ago, a fifth (19.6%) 2 to 4 years ago, while only 2.9% of respondents received the invitation more than 4 years ago (

Figure 3).

Of the respondents who had received an invitation, significantly more (92.5 %) responded to the invitation within almost the same period of time after receiving it (

Figure 4). Figure 11 shows that all respondents who received an invitation a year ago also responded to it. Only 4% of respondents who received the invitation within a few months did not respond, but as this is the current period, it is possible that respondents are responding to this invitation. In the last two or more years, 3.8% of respondents have not responded to the invitation.

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the answer to the question: "What do you think should be done to increase the response to preventive examinations?".

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the answer to the question: "What do you think should be done to increase the response to preventive examinations?".

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the response of respondents to the National Program for Early Detection of Breast Cancer.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the response of respondents to the National Program for Early Detection of Breast Cancer.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the comparison of the time period for receiving and responding to a call.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the comparison of the time period for receiving and responding to a call.

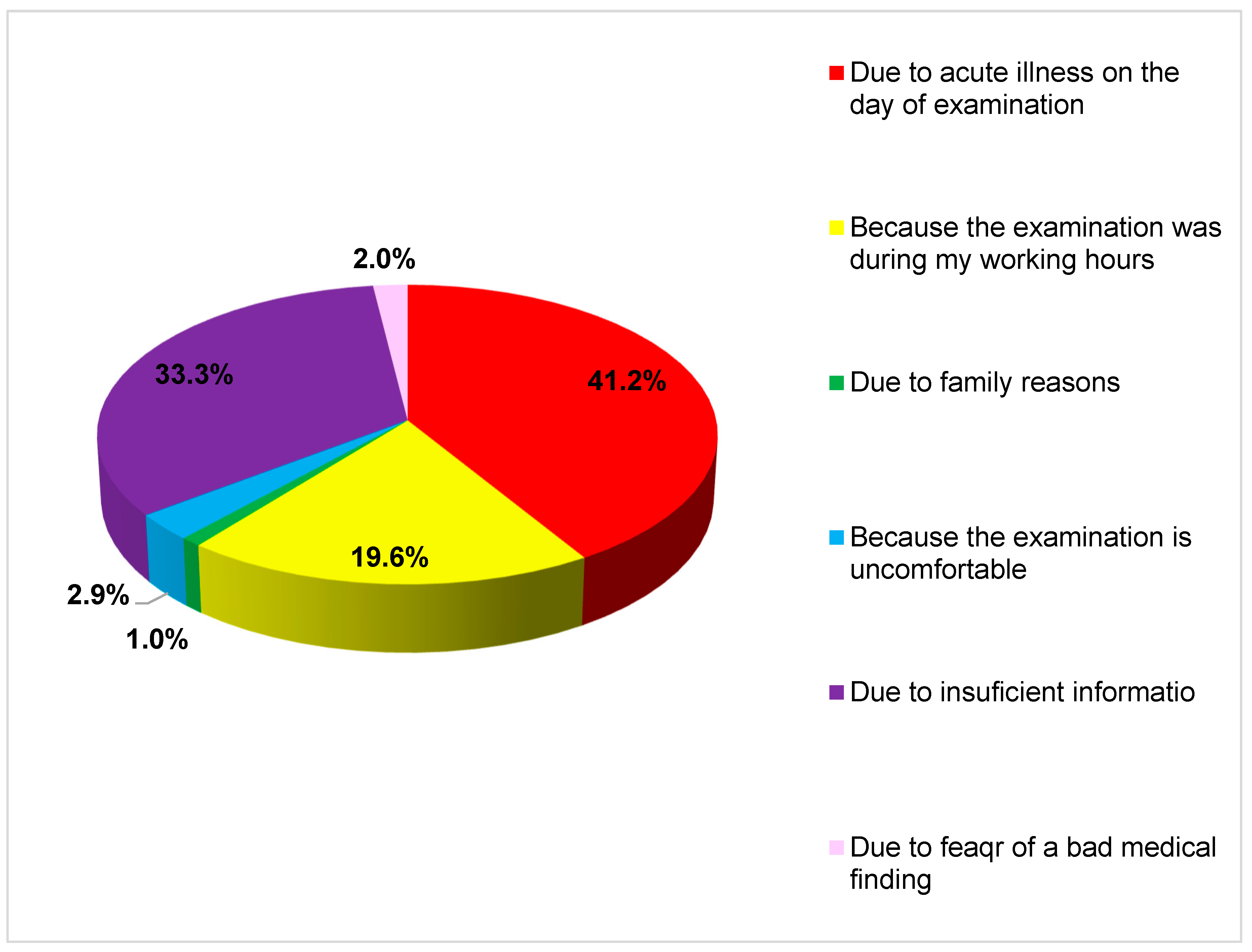

Figure 4.

Graphic representation of the reason why the respondent did not respond to the invitation.

Figure 4.

Graphic representation of the reason why the respondent did not respond to the invitation.

According to this sample, respondents in IŽ are very interested in NP and have a high response rate, so the H1 hypothesis is rejected.

H2: There is no statistically significant difference in the response of ZD compared to the response of the general population of women to the National Programme for Early Detection of Breast Cancer in the Republic of Croatia.

In recent years, several cycles of calls for mammography have been carried out as part of the NP. In the first cycle, the response rate was 63%, in the second cycle 57% and in the third cycle 60%. In the seventh cycle, for example, 34892 women were invited to the IC and the response rate to date has been 60.62%.

As part of this study, 93 people from the healthcare staff of the city of Iž were invited for a mammography examination, and 86 of them accepted the invitation, which corresponds to a rate of 92.5 %. Compared to the average rate in the Republic of Croatia of 60% (which includes a heterogeneous group of respondents, not only healthcare workers), the difference is statistically significant (, so the H2 hypothesis that there is no statistically significant difference in the response of healthcare workers compared to the response of the general population of women to the National Programme for Early Detection of Breast Cancer in the Republic of Croatia cannot be accepted, but this difference is statistically significant. "χ2=5973,45,p=0,001)"

H3: The expected reason for not answering is fear of an unpleasant examination or malignant breast disease.

Most respondents (41.2%) did not take part in the examination for practical reasons because they were acutely ill on the day of the examination. One in three respondents (33.3%) did not attend the examination because they were not sufficiently informed about it. A fifth of respondents (19.6%) did not attend the examination because it fell during working hours. The fewest respondents did not attend the examination because they were afraid of suffering from a malignant breast disease (2.0 %), because the examination was unpleasant (2.9 %) and for family reasons (1.0 %) (Figure 5).

As the dependent variable is a binary variable (response to the examination), a logistic regression analysis was performed with independent variables: categorical variables for non-response and age (

Table 2).

All calculations were performed with reference to an acute illness as the reason for absence. Fear of an unpleasant examination and possible confrontation with breast cancer reduces the probability that the patient will respond to the examination, while this probability increases as the patient's age increases.

The results presented here show that the model fits the data much better than the null model, χ²(6)=19.461, p=0.003. The Hosmer & Lemeshow test for model evaluation shows a good model fit (p=0.315). The model is well classified, the predictive power of the model is 87.3 %.

This study showed that there is a statistically significant relationship between the response to the invitation to the NP and the reason for absence from work (rpb = 0.476 p = 0.001).

Although fear of an unpleasant examination or malignant breast disease are not among the most common reasons for non-response, they are statistically significant, as shown by the regression analysis, so hypothesis H3 is accepted.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the response of female health workers in IŽ to NP. The study found that 91.2% of respondents received an invitation to NP, and of those who received an invitation, 92.5% responded to the invitation. This response rate is significantly higher than the average rate in the Republic of Croatia, which is around 60%, but these results do not relate to the general population, but only to healthcare workers in the county. However, this is precisely the specificity of this work, because a systematic review of databases did not find a single paper or scientific article examining the response of ZD to prevention programmes, regardless of the type of ZD or the type of prevention programmes in question. Most studies examined the role of health professionals, such as physicians, in the promotion of prevention programmes, education, and their knowledge and attitudes towards prevention programmes and self-examination in general [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. For example, studies from the 1990s showed that one of the strongest incentives for women to undergo preventive mammography is a doctor's recommendation [

19,

20]. Even if healthcare professionals are not directly involved in referring patients for breast cancer screening, they play an important role in creating an environment that supports preventive behaviour by providing positive role models. Studies in developed countries show that their attitudes and orientation are important determinants of the use of breast cancer screening prevention programmes [

21,

22,

23]. It was also found that to be effective as educators and promoters of prevention programmes, health girls must have appropriate knowledge, attitudes and beliefs regarding the health behaviour being promoted. In a descriptive cross-sectional study [

24] conducted in 2012, 100 health professionals, including 30 female physicians and 70 male doctors, were interviewed at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital in Sokoto. The aim of the survey was to determine their knowledge of breast cancer and their attitudes towards mammography and its use. Of the total number of respondents, 67% had sufficient knowledge of breast cancer and its risk factors, with doctors showing a better understanding (80%) than nurses. The majority (84%) were aware of mammography as a method of early detection of breast cancer, but only 9% had undergone this examination in the last year. The most common reason for not going for a mammogram was that they did not know it was available at the study centre. The low rate of mammography screening in the study is worrying and emphasises the urgent need for educational measures to improve awareness and participation in mammography screening in the target group. In addition, a cross-sectional study conducted in 2018 involving doctors, nurses and medical support staff in King Fahad Medical City (KFMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, found that knowledge, attitudes and practises related to breast cancer screening were lower than expected. A total of 395 respondents from the healthcare professions took part in the study. The average age of the participants was 34.7 years. Participants included physicians (n=63, 16.0%), nurses (n=261, 66.1%) and allied ZDs (n=71, 18.0%). Only 6 (1.5%) participants had a good level of knowledge about breast cancer, 104 (26.8%) participants had an intermediate level of knowledge. A total of 370 (93.7%), 339 (85.8%) and 368 (93.2%) participants had heard of breast self-examination, clinical breast examination and mammography, respectively. A total of 295 (74.7 %) of the participants stated that they practised breast self-examination, 95 (24.1 %) had undergone a clinical breast examination and 74 (18.7 %) had undergone mammography [

25,

26].

A cross-sectional study conducted among 441 female healthcare professionals (physicians = 88, nurses = 163, midwives = 38, office workers = 68, and others = 84) in three different health centres in Yazd, Iran, found that respondents' health beliefs about perceived susceptibility to breast cancer and perceived benefits of self-examination and mammography significantly influenced their practise of participating in screening programmes. It was found that 41.9% of respondents had performed breast self-examination in the past and 14.9% did so regularly, while only 10.6% underwent mammography [

27].

Breast self-examination is certainly not the most reliable diagnostic tool, but it can contribute to the early detection of breast cancer and at the same time raise awareness of breast care. Judging by the studies mentioned above, this awareness is not sufficiently developed among women working in the healthcare sector. A study investigating the extent of self-examination among nursing students in Aceh and the level of self-efficacy of those who performed it found that 39.5% of students performed breast self-examination and more than half (60.5) did not perform self-examination. The main factors influencing not performing self-examination were the absence of breast cancer in the family history, single status and the absence of breast disease in the personal history. Of the 30 students who performed self-examination, most did not perform it routinely (70%) or at the right time (86.7%), and their overall confidence in performing it was moderate [

28].

Studies that show the attitudes of doctors, especially PHCs, in industrialised countries towards the effectiveness of self-examinations and screening tests such as mammography are also interesting. For example, Women's University Hospital and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, both in Toronto, conducted a cross-sectional study to determine the attitudes and behaviours of primary care physicians towards screening mammography, breast self-examination and breast awareness in women aged 40 to 49 years with an average risk of breast cancer. The survey found that less than half (46%) of GPs regularly screen women aged 40-49 at average risk of breast cancer with mammography. While 40% of doctors believe that screening is unnecessary for this age group, 62% would do it if the patient requested it. The main reasons against screening are the lack of evidence of lower breast cancer mortality (63%), the recommendation to start screening at the age of 50 (25%) and the fact that the potential harm outweighs the benefit (19%). In contrast, reasons for screening included patient preference (55%), personal clinical experience or advice from mentors (27%) and counselling (18%). The majority of physicians (74%) were not in favour of breast self-examination, but the majority (81%) supported the practise of breast awareness [

29].

It should be noted that this study was conducted in 2012 in Canada, whose healthcare system differs significantly from that of Croatia and most European Union countries. Although the Croatian National Park's guidelines for early detection of breast cancer include women aged 50 to 69 years, given the increasing incidence of breast cancer in younger age groups, it is recommended that every woman should have her first mammography examination between the ages of 38 and 40. Accordingly, and in line with the recommendations of the European Commission, it is also being considered to move the age limit for preventive mammography under the NP to between the ages of 45 and 74. [

9]

To summarise the first hypothesis of this research, H1 is rejected and that the both cities have a high response rate to NP and thus a highly developed awareness of the importance of response to NP and contribute to raising awareness in the general population through their own example. This is followed by H2, which is also not accepted as there is a statistically significant difference (p=0.001) in the response of women in health professions compared to the response of the general population of women to NP in the Republic of Croatia. Although neither H1 nor H2 could be confirmed, it can be concluded that the data are very encouraging and positive. Healthcare professionals, and nurses in particular, have a key role to play in promoting early detection of breast cancer through prevention programmes. MS/mt-led interventions can contribute to the early detection of cancer through several methods. Firstly, MS/MT-led counselling and education interventions can help to provide information about cancer symptoms, risks and screening methods to improve awareness of symptoms and knowledge about cancer, perception of its threat and early detection. Such information can help to reduce disease assessment timescales and encourage timely access to healthcare services to enable early diagnosis and participation in prevention programmes. Nurse-led interventions may also facilitate access to services to improve opportunities for early cancer detection.

The third hypothesis related to the reasons why women do not attend NP, and the assumption was based on fear of an unpleasant examination or malignant breast disease. Although most of the respondents did not cite these reasons as the main reasons for not attending NP, the regression analysis showed that these reasons nevertheless had a statistically significant influence on non-attendance at screening.

Research into early detection of breast cancer has uncovered various factors that affect the utilisation or non-utilisation of screening examinations by women. A study conducted in France in 2006 therefore set out to investigate the independent role of socio-demographic factors in the uptake of mammography depending on whether or not an organised breast cancer screening programme exists. In a cross-sectional survey of French households, a sample of 2825 women aged between 40 and 74 was analysed. Of this group, 46% lived in districts with screening programmes and 63% had undergone a mammography in the last two years. Living in districts with screening programmes is associated with a higher uptake of mammography. Socio-demographic factors such as higher household income and higher education levels were associated with higher mammography uptake according to univariate and multivariate analyses. Three factors significantly increased the use of mammography: a recent gynaecological examination, living in a district with a screening programme and age. An interaction was observed between living in a district with a screening programme and age. Between the ages of 40 and 60, the influence of age on the use of mammography remained constant, regardless of the availability of a screening programme in the district. After the age of 60, however, the use of mammography fell sharply in districts without organised screening. Despite the generally high level of screening and the fact that screening programmes ensure continuous uptake among older women, poor women need to be better targeted and the role of general practitioners strengthened, especially among women without gynaecological care [

30].

The study of the target population of 1,208 women from the Požega-Slavonia County area who did not respond to the invitation for preventive mammography and were invited as part of the NP in the period from 2011 to 2014, carried out as part of the dissertation, produced some interesting results. 804 respondents were classified according to age, distance to the mammography unit, type of establishment and availability for screening. Reasons for non-response were provided for half of the respondents, while the distribution by education, information, socioeconomic status (SES) and attitude towards mammography was shown for 32 of respondents. Respondents with a higher level of education were more likely to give objective reasons for non-response than respondents with a lower level of education (81% vs. 77% and 61%, p=0.021). With the increase in education level, the percentage of women who had already undergone mammography outside the programme also increased (31% vs. 46% and 59%, p=0.016), while a lower number of women cited transport problems as a reason (41% vs. 23% and 9%, p<0.001). Subjects who had a mammography outside the programme had a higher average score on the information scale, as did those who did not like the screening appointment, while those who cited a family situation or transport problems as a reason had a lower score. Social status was significantly associated with reasons for non-response, in the sense that type of settlement and proximity to the mammography unit influenced patterns of non-response, but there was no association with the material status of the household. Respondents from rural areas further away from the mammography unit were less likely to give objective reasons for non-response than respondents from urban areas closer to the unit. Respondents in rural areas were more likely to give subjective reasons for non-response than those in urban areas [

31].

Conclusion

The research conducted in Iž shows positive trends in the participation of health professionals in the national programme for the early detection of breast cancer, which is an encouraging sign in the fight against this disease. The high response rate shows that healthcare professionals are aware of the importance of prevention and early detection and are committed to it. However, the research also highlights important factors that contribute to non-response, including practical barriers, lack of information and anxiety around screening itself. Understanding these barriers is key to further developing the programme and increasing the response rate. Addressing practical issues, such as the availability of dates and places to visit, can greatly facilitate access to the programme. Raising awareness through education campaigns and clearly communicating the benefits and safety of screening can also reduce anxiety and encourage more people to participate. Providing emotional support and counselling for those affected can also play a key role in encouraging more people to respond to the call. By taking a comprehensive approach that includes solving logistical problems, improving communication and providing support, it is possible to achieve an even higher response rate and thus contribute to early detection and better treatment outcomes for breast cancer. These findings provide important guidance on how action can be taken at local level and beyond to ensure that national breast cancer screening programmes reach their full potential to save lives.

References

- HZJZ. National Prevention Program for Early Detection of Cervical Cancer [Internet]. Croatian Institute of Public Health. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 21]. https://necurak.hzjz.hr/o-programu/nacionalni-preventivni-program-npp-ranog-otkrivanja-raka-vrata-maternice/ (accessed 2023 Dec 21).

- Capak K, Kralj V, Brkić Biloš I, Silobrčić Radić M, Šekerija mario, Benjak T, et al. Comparison of indicators on leading public health problems in the Republic of Croatia and the European Union [Internet]. Croatian Institute of Public Health. 2017 [cited 2024 Feb 11]. https://www.hzjz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Pokazatelji_RH_EU.pdf (accessed 2024 Feb 11).

- Katicic, M.; Antoljak, N.; Kujundzic, M.; Stamenic, V.; Stimac, D.; Poljak, D.S.; Kramaric, D.; Pesigan, M.S.; Samija, M.; Ebling, Z. Su1464 Results of National Colorectal Cancer Screening Program in Croatia (2007-2011). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012, 75, AB341–AB342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C. Early Detection and Screening for Breast Cancer. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 33, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NZJZ Andrija Štampar. National Cancer Early Detection Programs [Internet]. NZJZ Andrija Štampar. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 21]. https://www.stampar.hr/hr/nacionalni-programi-ranog-otkrivanja-raka (accessed 2023 Dec 21).

- Croatian Institute of Public Health, Cancer Registry of the Republic of Croatia. Croatian Institute of Public Health: Cancer incidence in Croatia. 2013. Bulletin [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Dec 19]; (38).

- Šiško, I.; Šiško, N. Preventivni programi za rano otkrivanje raka dojke u Republici Hrvatskoj Prevention programs for early detection of breast cancer in Croatia. Sestrin. Glas. J. 2017, 22, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, I. Response to the National Program for Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer in Varaždin County [Internet] [Master's thesis]. [Koprivnica]: University North; 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 11].

- HZZJZ. Early detection of breast cancer [Internet]. Croatian Institute of Public Health. 2024 [cited 2024 ]. https://www.hzjz.hr/nacionalni-programi/rano-otkrivanje-raka-dojke/ (accessed 2024 May 18).

- HZZJZ. Department of Breast Cancer Screening Programs [Internet]. Croatian Institute of Public Health. 2020 [cited 2024 ]. https://www.hzjz.hr/sluzba-epidemiologija-prevencija-nezaraznih-bolesti/odjel-za-programe-probira-raka-dojke/ (accessed 2024 May 18).

- Vrdoljak E, Pleština S, Belac-Lovasić I, Katalinić-Janković V, Radić Krišto D, Kusić Z, et al. National Plan Against Cancer 2020-2030 Zagreb; 2020.

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. National Prevention Programs [Internet]. Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. [cited 2024 ]. https://zdravstvo.gov.hr/nacionalni-preventivni-programi/1760 (accessed 2024 May 18).

- upe Parun A, Kovačević J. Epidemiological guidelines for quality assurance of early detection of breast cancer. In: Capak K, Brkljačić B, Šupe Parun A, editors. Croatian Guidelines for Quality Assurance of Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Zagreb: Croatian Institute of Public Health; Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia; 2017. pp. 1–21.

- A Shaheen, N.; Alaskar, A.; Almuflih, A.; Muhanna, N.; Alzomia, S.B.; A Hussein, M. Screening Practices, Knowledge and Adherence Among Health Care Professionals at a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, ume 14, 6975–6989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaren A, Ozkilinc G, Guler A, Oztop I. Awareness of breast and cervical cancer risk factors and screening behaviours among nurses in rural region of Turkey: Original article. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008; 17(3):278–84.

- A Ibrahim, N.; O Odusanya, O. Knowledge of risk factors, beliefs and practices of female healthcare professionals towards breast cancer in a tertiary institution in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 76–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanasekaran, K.; Verma, C.; Sriram, L.; Kumar, V.; Hariprasad, R. Educational intervention on cervical and breast cancer screening: Impact on nursing students involved in primary care. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 2846–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, H.H.; Shallouf, F.; Najim, A.; Alajerami, Y.S.; Abushab, K.M. Knowledge and Practices of Female Nurses at Primary Health Care Clinics in Gaza Strip-Palestine Regarding Early Detection of Breast Cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 3679–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odusanya OO, Tayo OO. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes and practice among nurses in Lagos, Nigeria. Acta Oncol. 2001; 40(7):844–8.

- Bastani, R.; Marcus, A.C.; Hollatz-Brown, A. Screening mammography rates and barriers to use: A Los Angeles county survey. Prev. Med. 1991, 20, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- on behalf of the PROSPR (Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens) consortium; Haas, J. S.; Barlow, W.E.; Schapira, M.M.; MacLean, C.D.; Klabunde, C.N.; Sprague, B.L.; Beaber, E.F.; Chen, J.S.; Bitton, A.; et al. Primary Care Providers’ Beliefs and Recommendations and Use of Screening Mammography by their Patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurie N, Margolis KL, McGovern PG, Mink PJ, Slater JS. Why do patients of female physicians have higher rates of breast and cervical cancer screening? J Gen Intern Med. 1997; 12(1):34–43.

- Bekker H, Morrison L, Marteau TM. Breast screening: GPs’ beliefs, attitudes and practices. Fam Pract. 1999; 16(1):60–5.

- Bastani, R.; E Maxwell, A.; Carbonari, J.; Rozelle, R.; Baxter, J.; Vernon, S. Breast cancer knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors: a comparison of rural health and non-health workers. . 1994, 3, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mo, O.; So, A.; As, U. Breast Cancer and Mammography: Current Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Female Health Workers in a Tertiary Health Institution in Northern Nigeria. Public Heal. Res. 2012, 2, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heena, H.; Durrani, S.; Riaz, M.; AlFayyad, I.; Tabasim, R.; Parvez, G.; Abu-Shaheen, A. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to breast cancer screening among female health care professionals: a cross sectional study. BMC Women's Heal. 2019, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiryazdi, S.M.; Kholasehzadeh, G.; Neamatzadeh, H.; Kargar, S. Health Beliefs and Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors among Iranian Female Health Workers. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 9817–9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanita J, Jittanoon P, Boonyasopun U. BSE Practice and BSE Self-Efficacy among Nursing Students in Aceh, Indonesia. Nurse Media: Journal of Nursing. 2013;3.

- Smith, P.; Hum, S.; Kakzanov, V.; Del Giudice, M.E.; Heisey, R. Physicians' attitudes and behaviour toward screening mammography in women 40 to 49 years of age. . 2012, 58, e508–13. [Google Scholar]

- Duport, N.; Ancelle-Park, R. Do socio-demographic factors influence mammography use of French women? Analysis of a French cross-sectional survey. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 15, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovačević, J. Patterns of Women's Non-Response to Mammography as part of the National Program for Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Požega-Slavonia County [Internet] [Dissertation]. [Zagreb]: University of Zagreb; 2024 [cited 2024 May 21].

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).