Submitted:

22 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Global Trends and Debates on AI and Employment

2.2. Studies Focused on Employment Quality and AI in China

2.3. Theoretical Analysis

2.4. Research Hypotheses

3. Material and Method

3.1. Research Sample and Data Sources

3.2. Definition of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Employment Quality

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable: Artificial Intelligence

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

| the variable names | Variable symbol | average value | standard deviation | maximum | minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Quality | Emp | 0.1636 | 0.0727 | 0.5669 | 0.0622 |

| Artificial Intelligence | Csmd | 88.2098 | 243.1382 | 4848.112 | 1.9951 |

| Urbanization Rate | Urb | 0.5608 | 0.1488 | 1 | 0.21 |

| Fiscal Expenditure Level | Gov | 0.1915 | 0.0941 | 0.7044 | 0.0439 |

| Trade Openness | Ope | 0.2127 | 0.3242 | 2.4913 | 0.0006 |

| Financial Development Level | Tra | 0.6870 | 0.2777 | 6.2050 | 0.0846 |

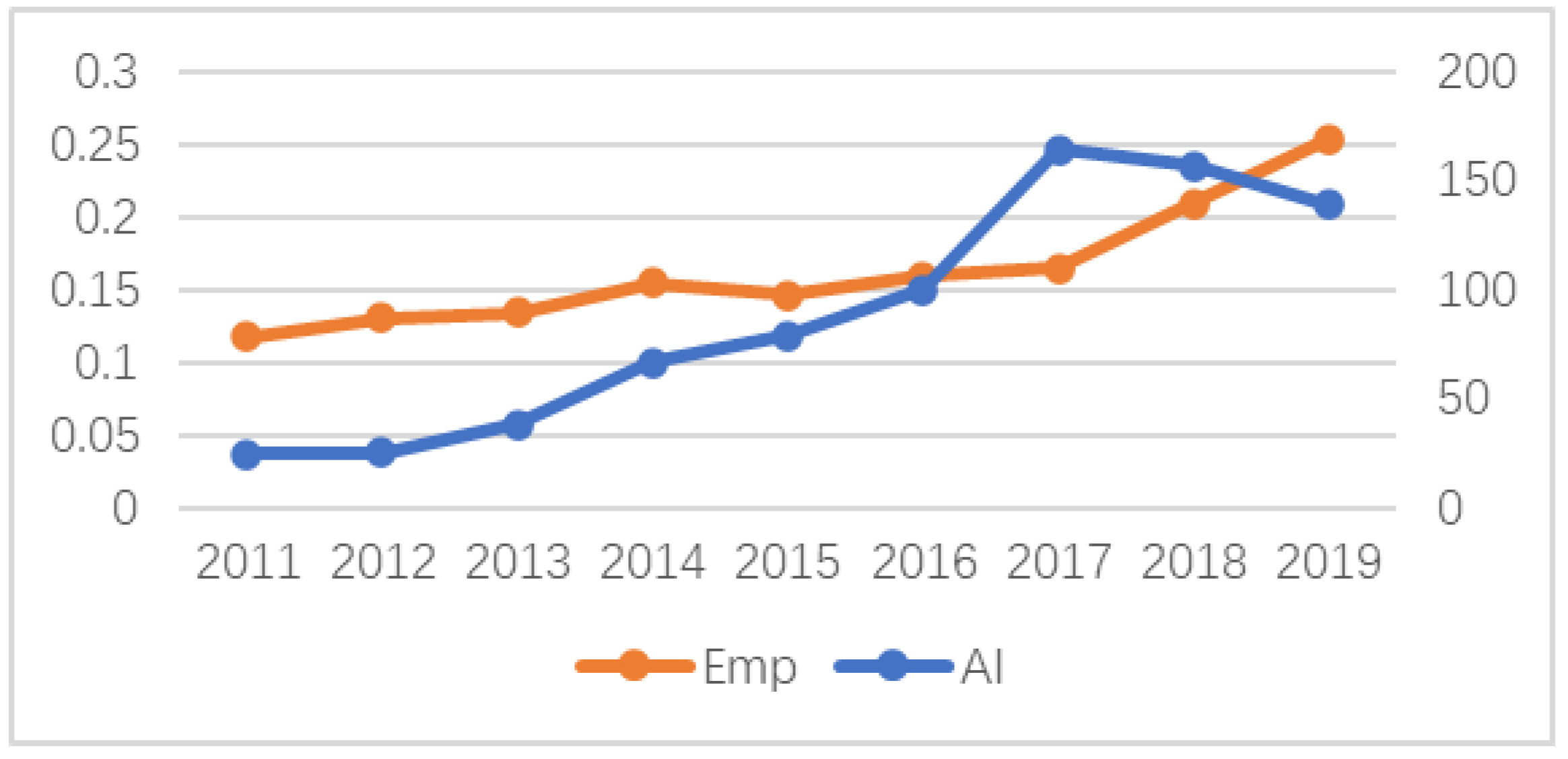

3.4. Trend Analysis

3.4. Model Specification

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

4.2. Heterogeneity Tests

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.4. Subregional Analys

4.5. Interpretation of Result

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Robustness Test

5.3. Comparison with Literature

5.4. Recommendations

5.5. Limitations and Further Research

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U. Awan.; R. Sroufe.; M. Shahbaz. Industry 4.0 and the circular economy: a literature review and recommendations for future research. Bus. Strat. Environ 2021, 30, 2038–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Acemoglu.; P. Restrepo. Robots and jobs: evidence from US labor markets. J. Polit. Econ 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subin Liengpunsakul. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development in China. The Chinese Economy 2021, 54, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Néstor Duch-Brown. ; Estrella Gomez-Herrera.; Frank Mueller-Langer.; Songül Tolan. Market power and artificial intelligence work on online labour markets. Research Policy 2022, 51, 104446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Xu.; Yue Qiu. ; Jingyu Qi. Artificial intelligence and labor demand: An empirical analysis of Chinese small and micro enterprises. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33893. [Google Scholar]

- Ting Wang. ; Shiqing Li.; Di Gao. What factors have an impact on the employment quality of platform-based flexible workers? An evidence from China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasraddin Guliyev. Artificial intelligence and unemployment in high-tech developed countries: New insights from dynamic panel data model. Research in Globalization 2023, 7, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Korinek.; J.E. Stiglitz. Artificial intelligence and its implications for income distribution and unemployment. NBER Working Papers 2018, 24174. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiming Chen. ; Xiaoqian Chen.; Zhan-ao Wang.; Roman Zvarych. Does artificial intelligence promote common prosperity within enterprises? —Evidence from Chinese-listed companies in the service industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 200, 123180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingqing Huo. ; Jing Ruan.; Yan Cui. “Machine replacement” or “job creation”: How does artificial intelligence impact employment patterns in China's manufacturing industry? Frontiers Artif. 2024, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Guangming Cao. ; Yanqing Duan.; John S. Edwards.; Yogesh K. Dwivedi. Understanding managers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions towards using artificial intelligence for organizational decision-making. Technovation 2021, 106, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, Fu. Quantifying the Impact of Artificial Intelligence Technology on High Quality Employment. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Bigdata Blockchain and Economy Management, ICBBEM 2024, Wuhan, China, 29–31 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chengzhang Wang.; Min Zheng.; Xiaoming Bai.; Youwei Li.; Wei Shen. Future of jobs in China under the impact of artificial intelligence. Finance Research Letters 2023, 55 Pt A, 103798. [CrossRef]

- P. Schneider.; F.J. Sting. Employees' perspectives on digitalization-induced change: exploring frames of industry 4.0. Academy of Management Discoveries 2020, 6, 406–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-ting, Gu.; Sanfeng Zhang. ; R. Cai. Can Artificial Intelligence Boost Employment in Service Industries? Empirical Analysis Based on China. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2022, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Yanlin Yang. ; Xu Shao. Understanding industrialization and employment quality changes in China: Development of a qualitative measurement. China Economic Review 2018, 47, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen Van Aerden. ; Guy Moors.; Katia Levecque.; Christophe Vanroelen. The relationship between employment quality and work-related well-being in the European Labor Force. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2015, 86, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianhui, Gu.; Xiaokan Wang. ; Shuang Liang. Employment Quality Evaluation Model Based on Hybrid Intelligent Algorithm. Computers, Materials and Continua 2022, 74, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hasraddin Guliyev. ; Natiq Huseynov.; Nasimi Nuriyev. The relationship between artificial intelligence, big data, and unemployment in G7 countries: New insights from dynamic panel data model. World Development Sustainability 2023, 3, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brougham, D.; Haar, J.; Smart Technology. Artificial Intelligence, Robotics, and Algorithms (STARA): Employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. Journal of Management & Organization 2018, 24, 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Shen. ; Xiuwu Zhang. The impact of artificial intelligence on employment: the role of virtual agglomeration. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinchun Zhang. ; Murong Sun.; Jianxu Liu.; Aijia Xu. The nexus between industrial robot and employment in China: The effects of technology substitution and technology creation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 202, 123341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingxing Chen. ; Xinrong Huang.; Jiafan Cheng.; Zhipeng Tang.; Gengzhi Huang. Urbanization and vulnerable employment: Empirical evidence from 163 countries in 1991–2019. Cities 2023, 135, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanchi Zou. The impact of fiscal stimulus on employment: Evidence from China’s four-trillion RMB package. Economic Modelling 2024, 131, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang Keller. ; Hale Utar. International trade and job polarization: Evidence at the worker level. Journal of International Economics 2023, 145, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzana Brixiová. ; Thierry Kangoye.; Thierry Urbain Yogo. Access to finance among small and medium-sized enterprises and job creation in Africa. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2020, 55, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles Shaaba Saba. ; Nicholas Ngepah. The impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on employment and economic growth in BRICS: Does the moderating role of governance Matter? Research in Globalization 2024, 8, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yu, Ruizhi Chen, and Jing Huang. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Current Social Employment and Structure: Empirical Evidence from Provincial Industrial Robots. International Journal of Global Economics and Management 2024, 2, 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D. , & Restrepo, P. Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and Work. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2018, 33, 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, M. , Bathelt, H., & Li, P. Regional Innovation Systems in Emerging Markets: The Role of Government Support for Industrial Upgrading. Regional Studies 2021, 55, 380–394. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrik, D. New Technologies, Global Value Chains, and Developing Economies." NBER Working Paper No. 25164. 2018.

- Chen, X. , & Zhang, Z. Policy Support and Technological Upgrading: A Study of China's Regional Development. China Economic Review 2022, 73, 101798. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Kim, Y.-G.; Liang, C. The Effect of Digitization on Economic Sustainable Growth in Shandong Province of China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Indicator | Indicator Explanation | Indicator Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Environment | Per capita GDP | Per capita GDP | Positive (+) |

| Regional GDP growth rate | Regional GDP growth rate | Positive (+) | |

| Proportion of employees in the tertiary sector | Proportion of employees in the tertiary industry | Positive (+) | |

| Regional employment rate | Urban unit employees / (urban unit employees + registered urban unemployed) | Positive (+) | |

| Regional unemployment rate | Registered urban unemployed / (urban unit employees + registered urban unemployed) | Negative (-) | |

| Degree of transportation accessibility | Per capita postal service volume | Positive (+) | |

| Labor Compensation | Absolute wage level | Average wage | Positive (+) |

| Relative wage level | Average wage growth rate | Positive (+) | |

| Healthcare insurance coverage | Number of urban employees enrolled in basic medical insurance / permanent population | Positive (+) | |

| Pension insurance coverage | Number of urban employees enrolled in basic pension insurance / permanent population | Positive (+) | |

| Urban-rural income gap | Urban residents’ average disposable income / rural residents’ average disposable income | Negative (-) |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Emp | Emp | |

| AI | -0.0000291** | -0.0000355*** |

| Gov | -0.1195794*** | |

| Ope | -0.0170889*** | |

| Tra | 0.0251705*** | |

| Urb | 0.0036482 | |

| City FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 195 | 195 |

| R2 | 0.9269 | 0.9297 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Emp | Emp | |

| AI | -0.0000583* | 0.0000116*** |

| Gov | -0.3007269*** | -0.0394055 |

| Ope | -0.0324078*** | 0.0069442 |

| Tra | 0.0571042*** | 0.001245 |

| Urb | -0.1025268*** | 0.0656932*** |

| City FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 70 | 100 |

| R2 | 0.9170 | 0.9297 |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Emp | Emp | |

| AI | 0.0000171*** | -0.0000292** |

| Gov | -0.0672*** | -0.0684*** |

| Ope | 0.0071 | -0.0225*** |

| Tra | 0.0220*** | 0.0088 |

| Urb | 0.0378*** | 0.0132 |

| City FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 195 | 195 |

| R2 | 0.9388 | 0.9280 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).