1. Introduction

Melanoma is the skin cancer with the highest mortality, and the number of new cases is still increasing year by year. Most patients with highly malignant melanoma still have metastasis and recurrence after operation. Studies have confirmed that [

1] tumor vaccine could effectively treat patients with advanced or recurrent cancer. It has achieved satisfactory clinical efficacy in clinical trials in the treatment of melanoma and has become an important cancer immunotherapy.

Cancer-testis antigens are not expressed in normal tissues, except immune exempted testicular tissue, but are overexpressed in a variety of cancer cells. As a tumor vaccine antigen, it can significantly enhance CTLs-mediated cytotoxicity and show outstanding tumor therapeutic ability [

2]. As a new CT antigen, HCA587 antigen has strong immunogenicity [

3]. It sensitizes serum lymphocytes in vitro to induce specific CTLs immune responses. In addition, antibodies against HCA587 protein can be detected in the serum of patients with liver cancer [

4], making it a high-quality candidate antigen for tumor vaccines. However, in practical application, when there is no immune adjuvant, the ability of protein antigen to induce CD8

+T cell response is limited. Therefore, in order to overcome this limitation, more protein vaccines are used in combination with immune adjuvants [

5]. Immunostimulatory complexes (ISCOMATRIX) are a class of nanoparticles based on saponins, which can assist in antigen presentation and enhance humoral and cellular immune responses [

6]. Oligodeoxynucleotide CpG ODN is a Toll-like receptor 9 agonist, which can induce Th1 response and enhance vaccine-specific antibody response [

7].

Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that HCA587 protein vaccine combined with commercial ISCOMATRIX and CpG ODN adjuvant had significant tumor therapeutic effect in tumor-bearing mice. It activated the immune system that kills tumor cells to the maximum extent, which was characterized by an increase in the number of tumor infiltrating CD4

+T and CD8

+T cells and a decrease in the number of Foxp3

+CD4

+T cells, the activation of CD4

+T cells secreting granzyme B and interferon-γ and the enhancement of Th1 immune response [

8,

9]. Previously, a large number of studies have been carried out on the anti-tumor mechanism mediated by activating the immune system, and it was clear that HCA587 protein combined with 12 μ g self-made ISCOMATRIX and CpG ODN adjuvant (referred to as "HCA587 protein vaccine") could induce the same strong and specific cellular and humoral immune response in mice, showing significant anti-tumor effect.

Tumors with a diameter of more than 2-3mm will stop growing without blood vessels, which shows that neovascularization in tumor tissue largely determines the growth and metastasis of solid tumors [

10]. Therefore, anti-tumor local neovascularization has become a new idea to develop tumor immunotherapy strategy. Among them, tumor vaccine has attracted wide attention as a highly targeted immune agent. In fact, vaccines based on vascular endothelial cells and their markers and angiogenesis-related molecules have achieved significant efficacy in a variety of tumors [

11,

12]. Obviously, the development of tumor vaccine to block angiogenesis will be beneficial to the treatment of tumor patients. The purpose of this study is to explore the effect and mechanism of immunotherapy with vaccine adjuvant combination on tumor angiogenesis. HCA587 protein vaccine inhibits local neovascularization of mouse melanoma and may be mediated by up-regulation of PEDF-activated p38/Bax/caspase pro-apoptosis pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

All animal studies were conducted in strict accordance with the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the Conservation and use of Experimental Animals. This experimental scheme was approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Nanchang University (NCULAE20221031001). Every effort was made to minimize the pain. When animals suffer too much, they will use the end of humanity.

2.2. Mice

The female mice of 6-8 weeks old C57BL/6J strain were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Zhejiang, China). The mice were fed in a miniature isolator without special pathogen.

2.3. Tumor Cell Line and Culture

As mentioned earlier [

8], B16 melanoma cells were introduced into the vector pEGFP-C1 containing the full-length HCA587cDNA sequence. The selected cells stably expressing HCA587 protein were stored in DMEM medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and cultured in 37 ℃, 5%CO2 humidified incubator.

2.4. Antibody

PEDF (ab180711, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), Angpt2 (ab155106, Abcam), VE-cadherin (ab205336, Abcam) antibodies were used. Antibodies of VEGFA (19003-1-AP), VEGFR2 (26415-1-AP), CD31 (28083-1-AP), HIF-1α (66730-1-Ig), HRP conjugated Affinity purified Goat Anti-Mouse IgG(H+L) (SA00001-1), HRP conjugated affinity purified Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG(H+L) (SA00001-2) were purchased from Proteintech (Wuhan, China).β-Actin antibody was purchased from TransGen Biotech Co., LTD (Beijing, China). Antibodies of p38 MAPK (8690T, CST, USA), p-p38 MAPK (4511T, CST), Cleaved Caspase-3 (9661T, CST), Caspase8 (4790T, CST), Cleaved Caspase-3 (9661T, CST), Caspase9 (9508T, CST), Bax (2772T, CST), Angpt2 (AF5124, Affinity), VE-cadherin (AF6265, Affinity) and PEDF (DF6547, Affinity) were used.

2.5. Preparation of Vaccine

The recombinant Human HCA587 protein was prepared by Crown Bioscience, Inc (Beijing, China) with a purity of >95% and was stored in the refrigerator at -80℃ for a long time. The vaccine was formulated with the addition of all-phosphorothioate modified CpG ODN1826(5'-TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT-3') (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) and self-made ISCOMATRIX adjuvant. The HCA587 protein vaccine was composed of HCA587 protein (10μg), CpG ODN (12μg) and self-made ISCOMATRIX (12μg) with PBS solution as the carrier.

2.6. Tumor Vaccination and Vaccine Immunity

Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 100μl PBS solution containing 1 × 104 B16-HCA587 melanoma cells in the abdomen of the right flank. One week and four weeks later, the mice in the experimental group were injected with 100μl HCA587 protein vaccine containing 12μg self-made ISCOMATRIX and CpG ODN adjuvant through the tail vein, while the mice in the control group were injected with the same volume of sterile PBS solution at the same site. The tumor tissue was obtained aseptically one week after the last vaccine treatment.

2.7. Hematoxylin-Eosin Staining of Tumor Tissue

Mouse melanoma tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin to make a 5 μ m section. The sections were dewaxed with xylene and hydrated with concentration gradient ethanol, then stained the nucleus with hematoxylin, differentiated with differentiation solution, and stained cytoplasm with eosin; Then the sections were dehydrated with concentration gradient ethanol, transparent with xylene and sealed with gelatin. Finally, the stained image was observed under light microscope.

2.8. Alginate-Encapsulate Tumor Cells Assay

Alginate encapsulated tumor cell experiment was used to detect local tumor neovascularization in vivo. The main steps are as follows: On the 0th and 21st day, 100 μl HCA587 protein vaccine or sterile PBS solution was subcutaneously injected into the tail root of C57BL/6J mice. Two weeks after the last immunization, B16-HCA587 melanoma cells were resuscitated with 1.5% sodium alginate solution and dropped into the rotating 250mM CaCL2 solution to form alginate particles containing 1 × 104 cells each. Four microbeads were implanted subcutaneously on the back of immunized mice. 12 days later, 100 μl 1% TRITC-Dextran (100mg/kg) was injected into the tail vein of mice. After 20 min, the alginate particles were taken out and photographed immediately. Then the alginate particles were put into 2ml saline, shredded and ground, and the samples were shredded and ground. The supernatant was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 1 hour away from light at room temperature, and the fluorescence content of the supernatant was determined.

2.9. Immunohistochemical Staining

Mouse melanoma tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin to make 3-5 μm sections. Sections were dewaxed with xylene and then hydrated with ethanol at a concentration gradient, and incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution at room temperature in the dark for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The sections were placed in citrate buffer and boiled to achieve antigen retrieval. After blocking with normal goat serum at room temperature for 30 minutes, Sections were incubated overnight at 4℃ with 1 polyclonal antibody, PEDF polyclonal antibody, 2 monoclonal antibody, VE-cadherin monoclonal antibody, FA polyclonal antibody, VEGFR2 polyclonal antibody and HIF-1α monoclonal antibody primary antibody (All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:200), and then reacted with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 30 minutes. A color reaction was carried out with DAB working solution, and the cell nuclei were restained with hematoxylin, and the stained images were observed and analyzed under a light microscope.

2.10. Immunofluorescence Staining of Tumor Tissue

Mouse melanoma tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin to make 3-5 μm sections. The sections were dewaxed with xylene, then hydrated with ethanol in concentration gradient, and then put into EDTA buffer for heat treatment to achieve antigen repair. After blocking 30min with non-immunized normal goat serum at room temperature, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with anti-CD31 polyclonal antibody (1:200), anti-PEDF polyclonal antibody (1:200) and anti-VEGFA polyclonal antibody (1:200), and then incubated with CY3 Goat Anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:300) at room temperature for 50 min. The cell nuclei were re-stained with DAPI staining solution. The anti-fluorescence quenching and sealing tablets were used to seal the slices, and the slices were observed with a fluorescence microscope. Image J was used for quantitative analysis. Six high-power fields were randomly selected in each slice to detect the integrated optical density (IOD) of each field of view, and the average optical density of target proteins in the slices was compared.

2.11. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Mediated Nick End Labeling

Mouse melanoma tissue was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and made into 3-5μm sections. Sections were dewaxed with xylene and then hydrated with absolute ethanol, and then incubated with 20μg/mL protease K working solution at 37℃ for 22 minutes to repair the sections. Sections incubated with 0.1% triton membrane breaking working solution at room temperature for 20 minutes to break the membranes, and reacted with a mixture of TDT enzyme and dUTP (1:50) at 37℃ for 1-2 hours. The nuclei were re-stained with DAPI and sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching tablets. The red fluorescence of TUNEL positive nuclei was observed by fluorescence microscope, and four equal-sized regions were randomly selected to calculate the average red fluorescence density to compare the apoptosis of tumor tissue.

2.12. Real-Time Fluorescence Quantitative Reverse Transcription-polymerase Chain Reaction

The melanoma tissues of mice frozen with 30-40mg liquid nitrogen were ground to powder. The total RNA was extracted and the concentration and purity were detected. Reverse transcription DNA was synthesized according to the instructions of reverse transcriptase kit, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed on the samples by TBGreen. The amplification procedures were as follows: Stage1 pre-denaturation, Reps:1,95 ℃, 30s stage 2 PCR reaction, Reps:40,95 ℃, 5s centroid 60 ℃, 30s 10s stage 3 dissolution curve analysis, Reps:1,95 ℃, 0s, 20 ℃ / s 65 ℃, 15s, 20 ℃ / s 95 ℃, 0s, 0.1C / s. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal reference for each reaction. The 2-△△CT was calculated by the cycle threshold (Ct) of the reference gene and the target gene, and the relative expression of target gene mRNA was compared between the two groups. The primer was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The sequence is shown in

Table 1.

2.13. Western Blot Analysis

The mouse melanoma tissue frozen with 30-40mg liquid nitrogen was ground to powder, and the tissue was fully lyzed in the RIPA buffer containing protease phosphatase inhibitor for 30min. After centrifugation, the protein supernatant was taken for the next step of analysis. 40μg of protein in each sample was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. The non-specific antibodies on the membrane were blocked with 5% skimmed milk powder or 5% bovine serum albumin, and then the membrane was incubated overnight at 4℃ with anti-CD31 polyclonal antibody, anti-PEDF polyclonal antibody, anti-Angpt2 monoclonal antibody,anti-VE-cadherin monoclonal antibody, anti-VEGFA polyclonal antibody, anti-VEGFR2 polyclonal antibody and anti-HIF-1α monoclonal antibody, anti-p38 MAPK monoclonal antibody, anti-p38 MAPK monoclonal antibody, Anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 polyclonal antibody, anti-Caspase 8 monoclonal antibody, anti-Caspase 9 monoclonal antibody, anti-Bax polyclonal antibody and primary β-actin primary antibody (all antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000), and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase labeled secondary antibody (1:10000) at room temperature for 1 h. The protein bands were visualized using a hypersensitive ECL chemiluminescent kit, and the relative protein content was determined using ImageJ density analysis, and the target protein was homogenized using β-actin as the internal reference gene protein.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

All analysis and graphics were done using GraphPad Prism version 9(GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The experiment was repeated 2-3 times independently. The Students' two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to compare the statistical difference between the two groups. P<0.05, it was considered that the difference was statistically significant.

4. Discussion

In the absence of angiogenesis, the tumor will stop growing. It can be seen that tumor angiogenesis is a necessary condition for maintaining tumor growth, which makes it an important target for tumor therapy [

13]. At present, anti-angiogenesis therapy is mainly divided into chemotherapy and immunotherapy, the former mainly includes angiogenesis inhibitors, Chinese herbal medicine, the latter mainly refers to angiogenesis-related molecular specific antibodies and vaccines. Molecular inhibitors (axitinib [

14], ZINC09875266 [

15], Endostar [

16] and ziv-aflibercept [

17]) that selectively block VEGF/VEGFR signaling pathway can weaken the tubulation ability of endothelial cells and the invasiveness of tumor cells. In addition, Diterpenoid tanshinones, a Chinese herbal medicine with complex components, attenuates the expression of VEGF in gastric cancer through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [

18], while Pileostegia tomentella (TCPT) upregulates the exosome miR-375-3p to regulate the function of endothelial cells [

19]. These herbs achieve tumor regression through anti-tumor angiogenesis. Although chemical drugs bring hope for the treatment of tumors, their side effects and long-term drug resistance limit their clinical application.

Therefore, immune agents with high safety and targeting have attracted wide attention, such as cell, protein, DNA or RNA and peptide vaccines made from vascular endothelial cells, vascular endothelial cell markers or angiogenesis-related molecules. They do not directly target tumor cells, but by inducing the immune system to produce humoral and or cellular immune responses to endothelial cells or angiogenesis-related molecules. Vaccines based on heterologous VEGFR2 [

20], FGFR-1 [

21] and endothelial cell markers (TEM8 [

22], TEM1/CD248 [

23]) strongly block tumor local angiogenesis and produce significant tumor therapeutic effects in a variety of mouse tumor models (melanoma, breast cancer and Meth A fibrosarcoma model). In further clinical studies [

24], oral T cell vaccine (VXM01) targeting VEGFR2 is safe and effective for advanced pancreatic cancer. The above studies show that anti-tumor angiogenesis therapy is a safe and feasible tumor treatment, whether chemical or immune agents will be a good choice for clinical treatment of tumor patients. Therefore, the discovery and development of drugs or vaccines with anti-angiogenic effects will bring hope to cancer patients. In this experiment, after the treatment of HCA587 protein vaccine, the tumor growth was inhibited and the local tumor angiogenesis decreased significantly, indicating that the anti-tumor effect of HCA587 protein vaccine is largely related to its inhibition of tumor angiogenesis.

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor, PEDF) is mainly secreted by endothelial cells, fibroblasts and tumor cells. It interacts with receptors to complete signal transduction [

25], and participates in the regulation of most physiological and pathophysiological processes (such as anti-angiogenesis, neuroprotection, fibrogenesis, etc.) [

26]. It was reported that the growth ability of ovarian cancer cells treated with small interfering RNA or neutralizing PEDF antibody was significantly enhanced [

27], and the melanoma growth of mice treated with recombinant adenovirus-PEDF was inhibited [

28], indicating that PEDF has a strong inhibitory effect on the growth of tumor cells and can promote the occurrence of cancer when it is deleted. Clinical trials have found that low expression of PEDF protein is significantly associated with advanced cancer progression and poor survival and prognosis in patients with solid tumors [

29]. These results highlight the anticancer activity of PEDF and its close relationship with tumor progression. In addition, the proliferation and migration activity of melanoma cells and prostate cancer cells overexpressing PEDF decreased [

30,

31], while the apoptosis rate increased, and the tumor growth slowed down after the cells were transplanted into the body. PEDF treatment of multiple myeloma cells [

32], malignant peripheral schwannoma cells [

33] and glioma cells [

34] showed similar results. Therefore, both endogenous PEDF and exogenous PEDF can promote the apoptosis of tumor cells and negatively regulate the growth of tumor cells. In view of the great differences in the tumor microenvironment of different tumors, PEDF induces tumor cell apoptosis in different ways, including up-regulating the expression of p53 and pro-apoptotic protein Bax and inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 [

34] or inducing FasL-dependent apoptosis [

30].

Currently, the inhibitory effect of PEDF on angiogenesis has been widely recognized. After injecting PEDF protein into the pre-ocular vitreous, it was seen that capillary formation was inhibited [

35]. Anti-oxide ceria nanoparticles (CeO2NPs) eye drops reduced laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in mice by reducing VEGF and increasing PEDF levels [

36]. In addition, the newly discovered PEDF-loaded pegylated nanoparticles (NP-PEG-PEDF) attenuated diabetes-induced proliferation, migration, and tubule formation of HUVEC, and inhibited VEGF secretion [

37]. These reports confirm that PEDF is an effective angiogenesis inhibitor. It is currently believed that PEDF mediates anti-angiogenic effects by regulating the expression of other angiogenesis-related factors or inducing apoptosis of endothelial cells [

38].

On the one hand, the balance of angiogenesis is determined by the levels of pro-angiogenic factors (such as VEGF) and anti-angiogenic factors (such as PEDF), and the two molecules interact. In tumor tissue from PEDF-treated gastric cancer transplanted mice [

39], PEDF reduces HIF-1α expression and nuclear translocation to reduce VEGF protein levels and thereby inhibit tumor angiogenesis. However, VEGF can significantly down-regulate the expression of PEDF protein in retinal capillary endothelial cells [

40]. In addition, PEDF recognizes and binds VEGFR2, which inhibits the binding activity of VEGFR2 to VEGF, thus reducing the signaling of VEGF to promote vascular endothelial cell proliferation and migration, ultimately leading to reduced neovascularization [

41,

42]. In this experiment, the HCA587 protein vaccine significantly enhanced the expression of PEDF in tumor tissue, and is considered to be an important regulatory molecule for its anti-tumor local angiogenesis. Although a decrease in the expression level of VEGFA was observed, it is not clear whether this is a direct effect of the HCA587 protein vaccine or an effect of PEDF, and in-depth research and exploration are needed. On the other hand, vascular endothelial cells are core members of the angiogenesis process. When they undergo apoptosis, angiogenesis will not be completed. The significant pro-apoptosis ability of PEDF is an important reason for its strong anti-angiogenesis effect. Analysis of the mechanism of PEDF promoting apoptosis found that PEDF induces apoptosis through multiple apoptosis signaling pathways. Early studies have shown [

43] that the anti-angiogenic activity of PEDF in vitro and in vivo depends on the dual induction of Fas and FasL and the resulting apoptosis. However, studies have reported that in endothelial cells [

44,

45,

46], PEDF activates JNK and weakens the binding of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) to the caspase-8 inhibitor cellular Fas-associated death domain-like interleukin1-converting enzyme inhibitor protein (c-FLIP) promoter, leading to apoptosis. In addition, studies have also found [

47] that in HUVECs, PEDF activates p38MAPK to up-regulate the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), promotes the transcriptional expression and post-translational modification of p53 gene, induces the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, enhances the expression activities of caspase3, aspase8 and caspase9, and leads to apoptosis to play an anti-angiogenic role. Further studies have shown [

48] that pretreatment of HUVECs with PPARγ antagonists or PPARγ small interfering RNAs (siRNA) can eliminate the activation of p53 and the induction of apoptosis by PEDF, confirming that PEDF promotes apoptosis in HUVECs by continuously inducing overexpression of PPARγ and p53. These studies have revealed different ways in which PEDF promotes apoptosis. These differences may be related to the different PEDF used to treat cells in the study, indicating that the structure and molecular length of the PEDF protein affect the function of the molecule.

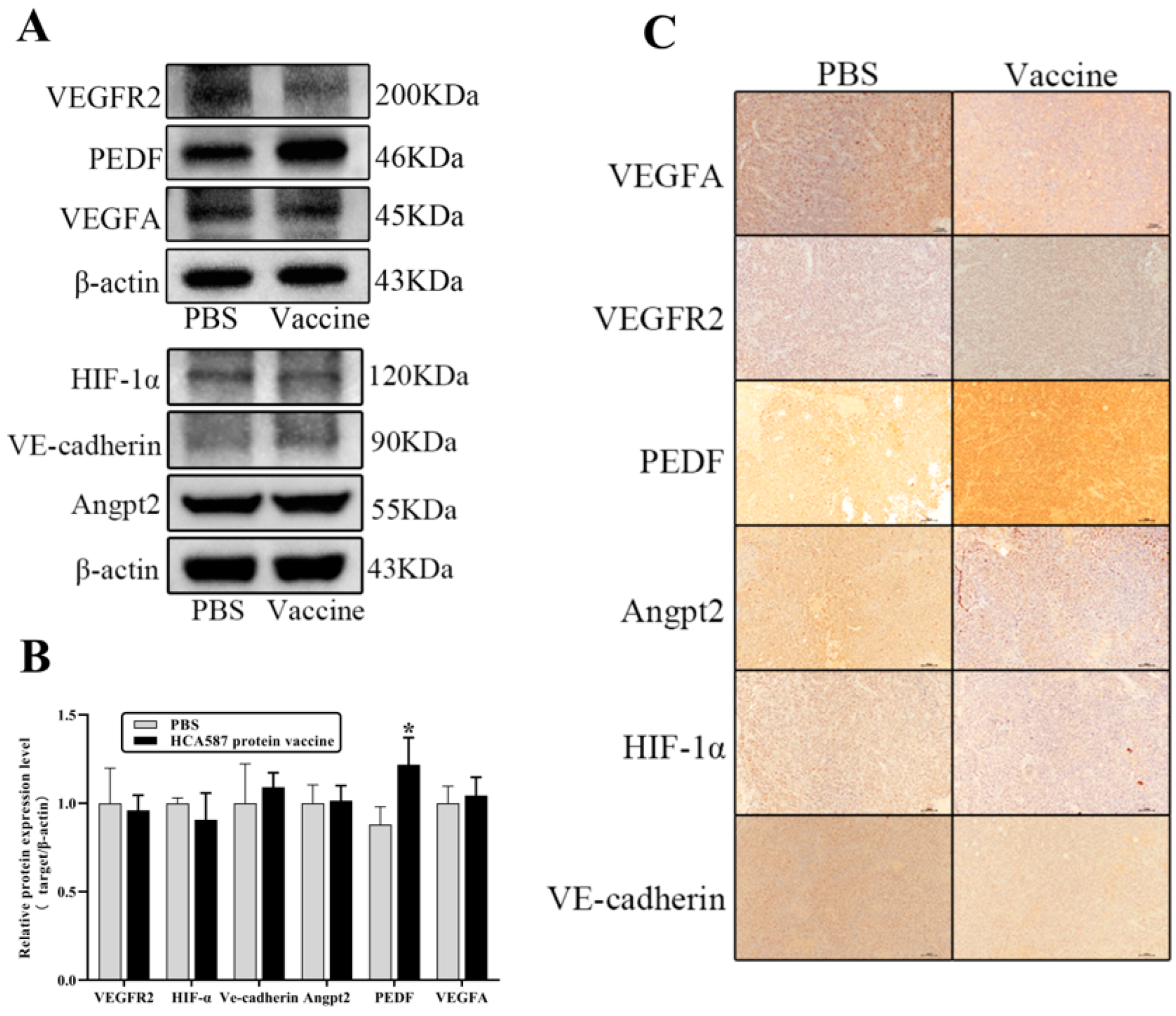

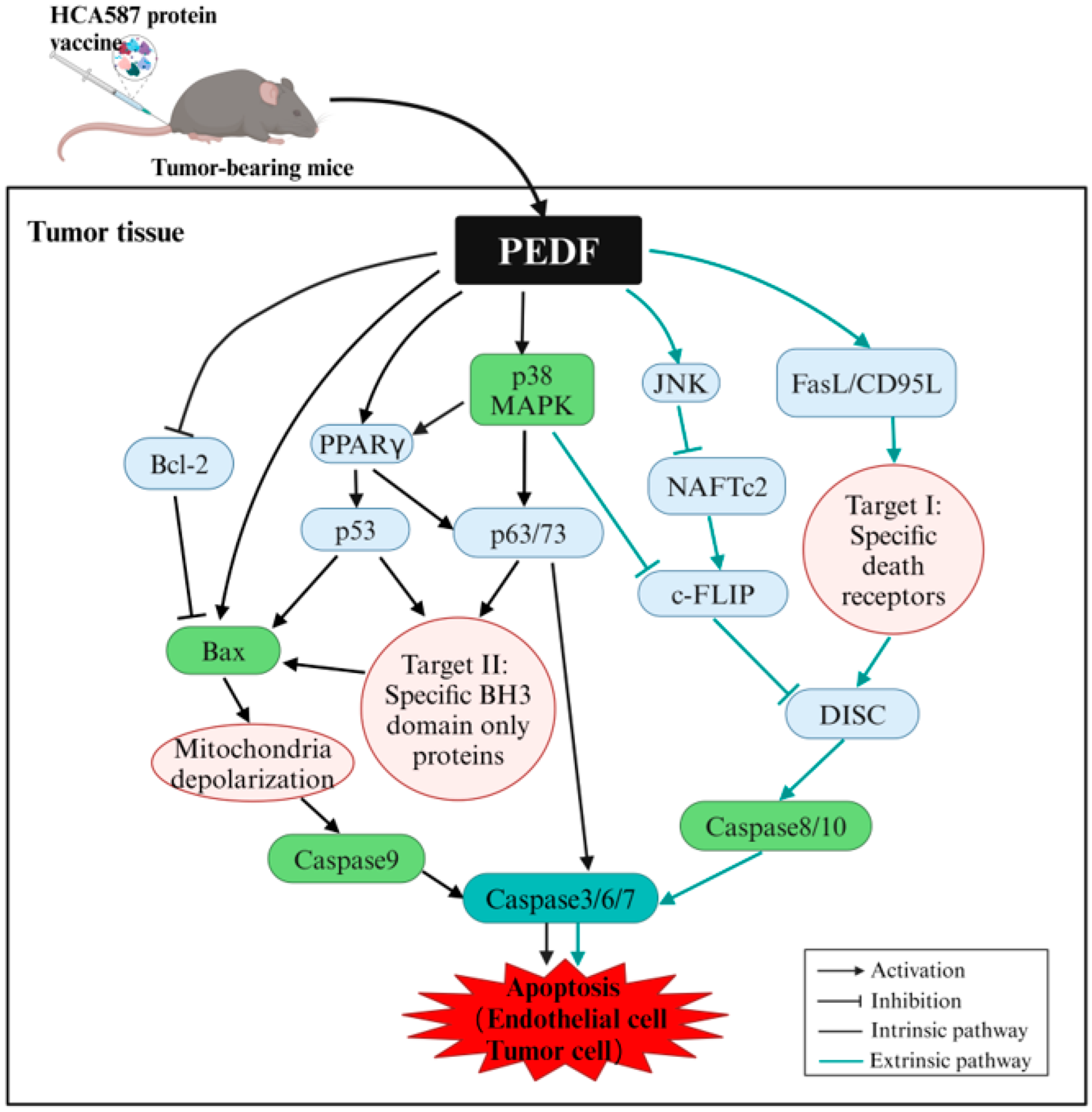

Figure 10 provides a detailed view of the PEDF-mediated pro-apoptotic pathways.

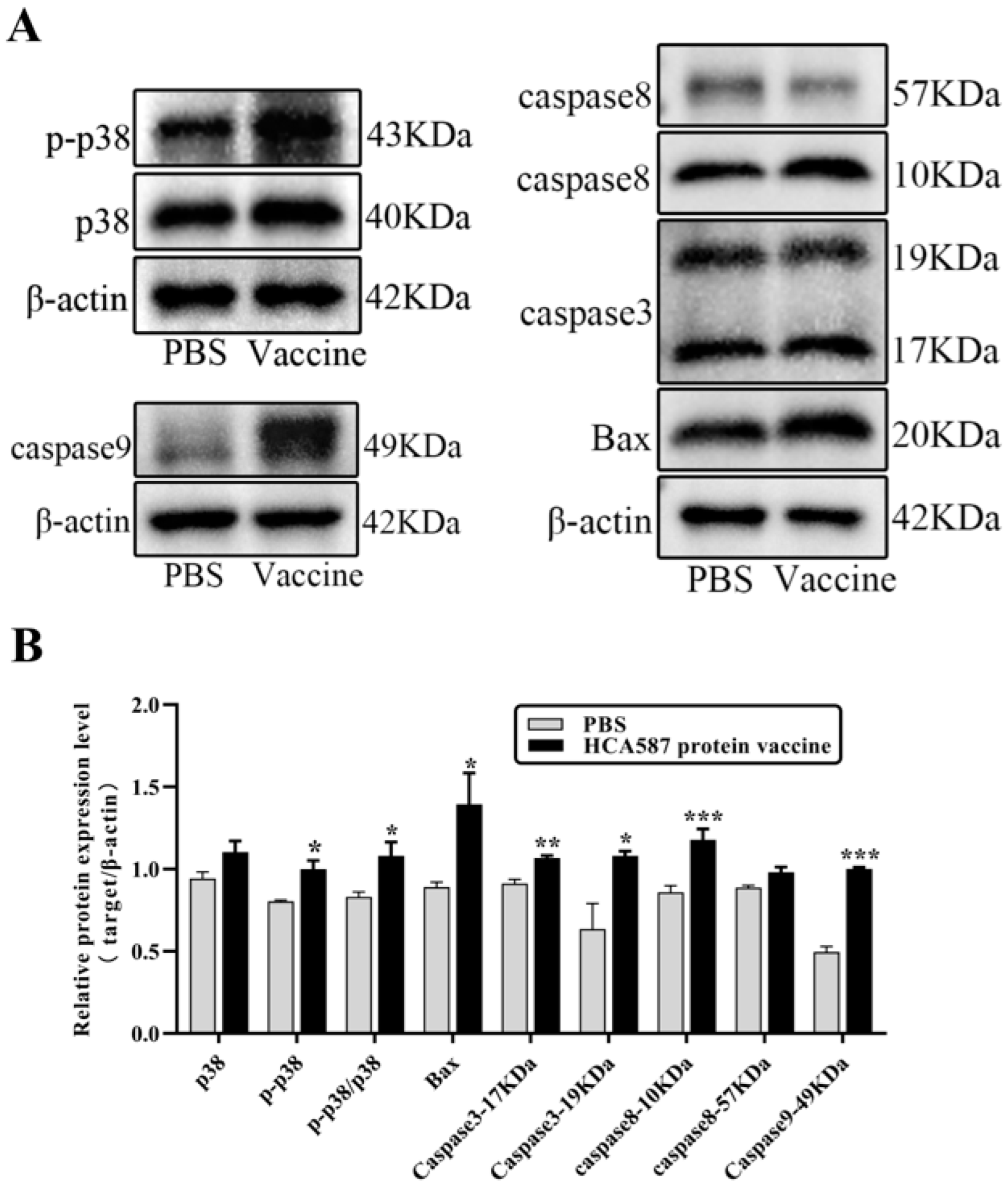

In this study, HCA587 protein vaccine significantly upregulated the transcription and protein expression levels of PEDF in tumor tissue. PEDF is a key member of anti-angiogenic factors. We screened it as an important cytokine for HCA587 protein vaccine to inhibit local neovascularization in melanoma in animals. Based on the pro-apoptosis effect of PEDF, we analyzed the mechanism of HCA587 protein vaccine against local neovascularization in tumors. We found that HCA587 protein vaccine promoted apoptosis in tumor tissue. Further detection of the expression changes of apoptosis-related proteins in tumor tissue showed that the HCA587 protein vaccine activated p38MAPK molecule, induced the expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, and enhanced the expression activities of caspase3, caspase8 and caspase9. These results initially suggest that HCA587 protein vaccine upregulates the expression of PEDF protein in tumor tissues, may promote cell apoptosis through the p38MAPK/Bax/caspase pathway, and ultimately inhibit local neovascularization in the tumor. The apoptosis executor caspase3 is the main executor of the exogenous apoptosis pathway mediated by death receptors (DR) and the endogenous apoptosis pathway in mitochondria. The exogenous apoptosis pathway is activated by the promoter caspase8, and the endogenous apoptosis pathway is activated by the promoter caspase9, respectively representing different apoptosis pathways [

50]. Our research shows that the HCA587 protein vaccine activates the endogenous apoptosis pathway of p38MAPK/Bax/caspase9, but the HCA587 protein vaccine also upregulates the expression of caspase8 and caspase9 proteins in tumor tissue, which suggests that our HCA587 protein vaccine may also initiate an exogenous apoptosis pathway to induce apoptosis. Future research can further analyze the complete pro-endothelial cell apoptosis pathway mediated by the HCA587 protein vaccine to inhibit local tumor neovascularization.

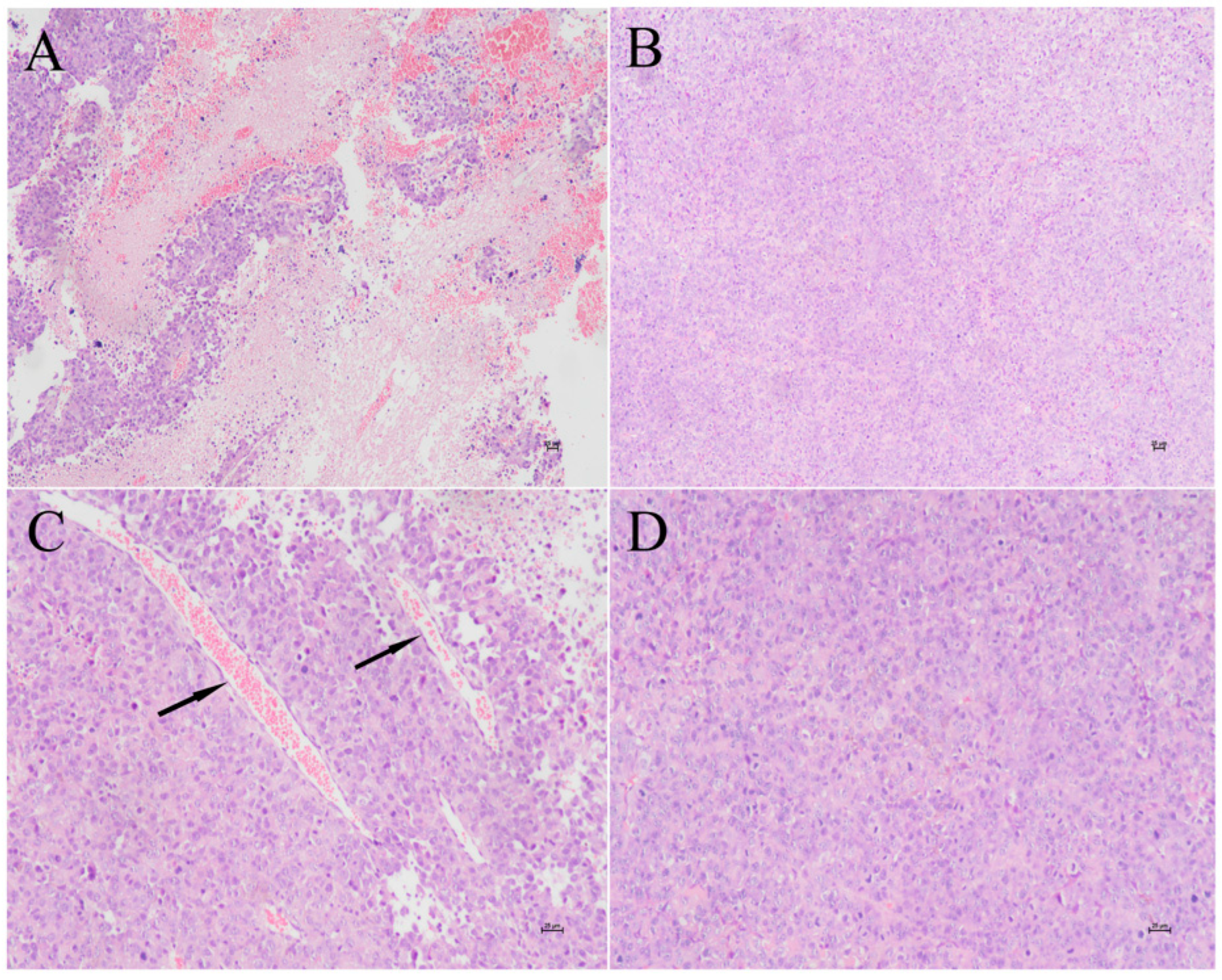

Figure 1.

HCA587 protein vaccine reduces tumor necrosis and angiogenesis. One week after the last vaccination, the tumor-bearing mice were killed and the tumor tissues were stained with HE. The necrosis and the number of blood vessels were compared between the two groups under the high magnification of 100x and 200x. The figure shows the tumor tissue of mice treated with PBS (A,C) and HCA587 protein vaccines (B,D). A and B are 100 ×, C and D are 200 ×.

Figure 1.

HCA587 protein vaccine reduces tumor necrosis and angiogenesis. One week after the last vaccination, the tumor-bearing mice were killed and the tumor tissues were stained with HE. The necrosis and the number of blood vessels were compared between the two groups under the high magnification of 100x and 200x. The figure shows the tumor tissue of mice treated with PBS (A,C) and HCA587 protein vaccines (B,D). A and B are 100 ×, C and D are 200 ×.

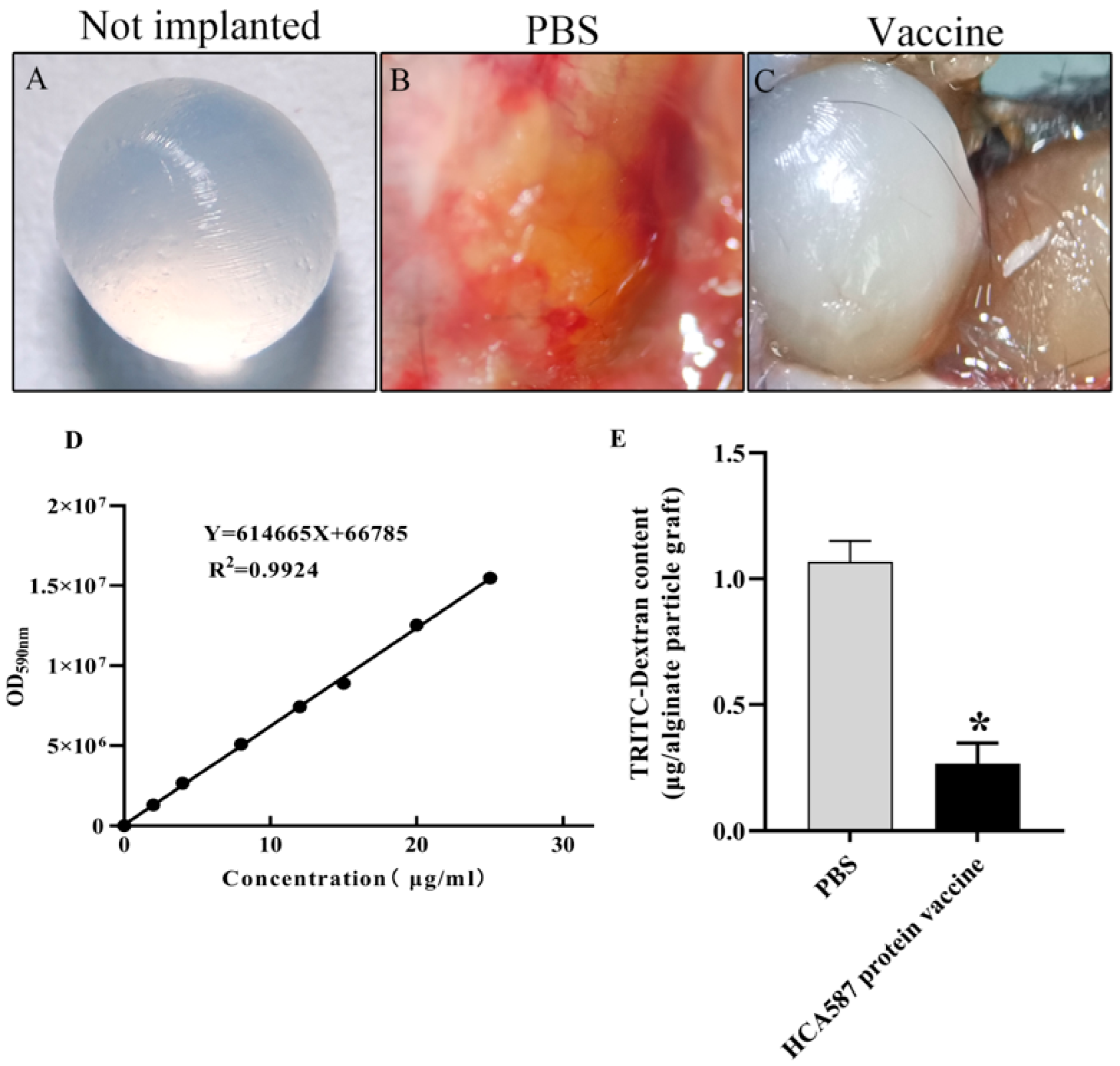

Figure 2.

Vascularization of alginate implants. On days 0 and 21, mice were subcutaneously immunized with sterile PBS solution (B) and HCA587 protein vaccine (C), and then alginate particles containing 1 × 104 tumor cells were implanted subcutaneously into the back of mice. The beads were removed by operation and the intake of TRITC-dextran (E) was measured. The uptake of TRITC-dextran in mice immunized with HCA587 protein vaccine was significantly decreased (P = 0.0205). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

Figure 2.

Vascularization of alginate implants. On days 0 and 21, mice were subcutaneously immunized with sterile PBS solution (B) and HCA587 protein vaccine (C), and then alginate particles containing 1 × 104 tumor cells were implanted subcutaneously into the back of mice. The beads were removed by operation and the intake of TRITC-dextran (E) was measured. The uptake of TRITC-dextran in mice immunized with HCA587 protein vaccine was significantly decreased (P = 0.0205). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

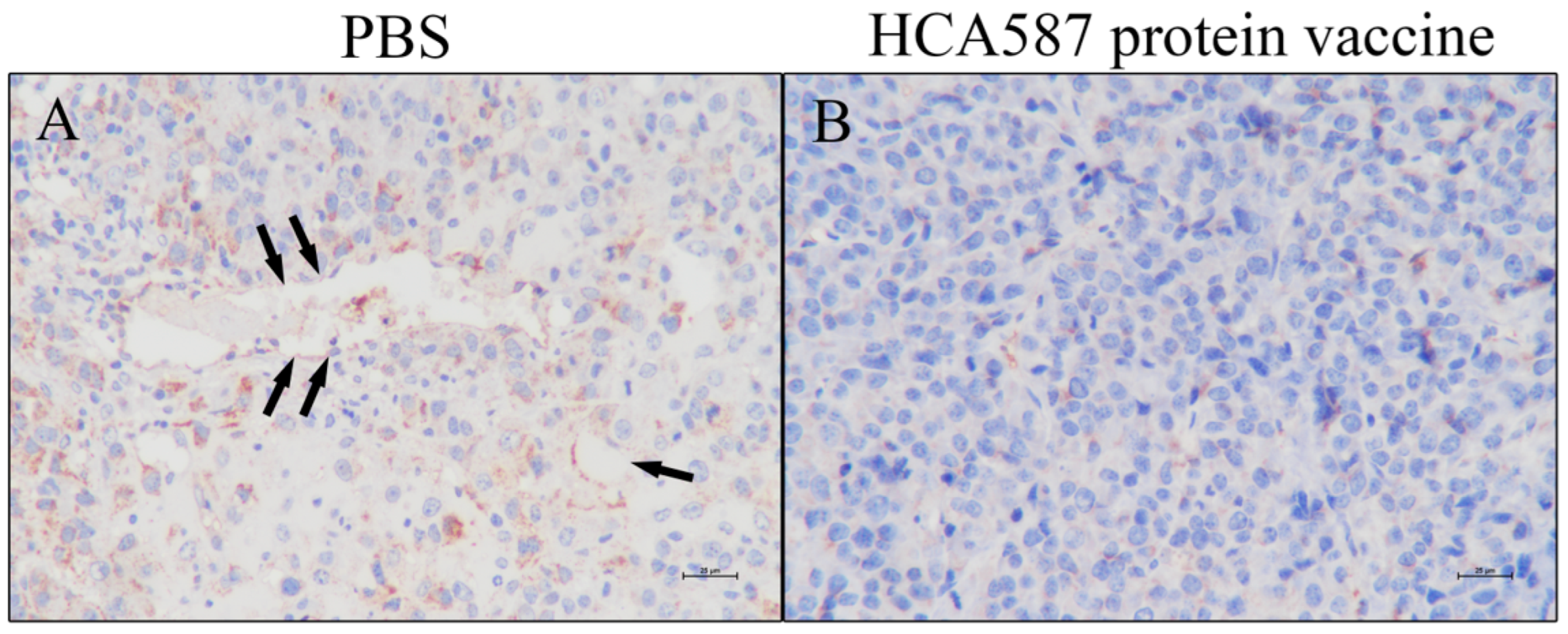

Figure 3.

Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. According to the description in "Materials and methods", the expression of CD31 between the two groups was compared under 400 × magnification. The figure shows the tumor tissue of mice treated with PBS (A) and HCA587 protein vaccine (B). The expression of CD31 protein in vascular endothelium of tumor tissue of mice treated with HCA587 protein vaccine was not obvious.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. According to the description in "Materials and methods", the expression of CD31 between the two groups was compared under 400 × magnification. The figure shows the tumor tissue of mice treated with PBS (A) and HCA587 protein vaccine (B). The expression of CD31 protein in vascular endothelium of tumor tissue of mice treated with HCA587 protein vaccine was not obvious.

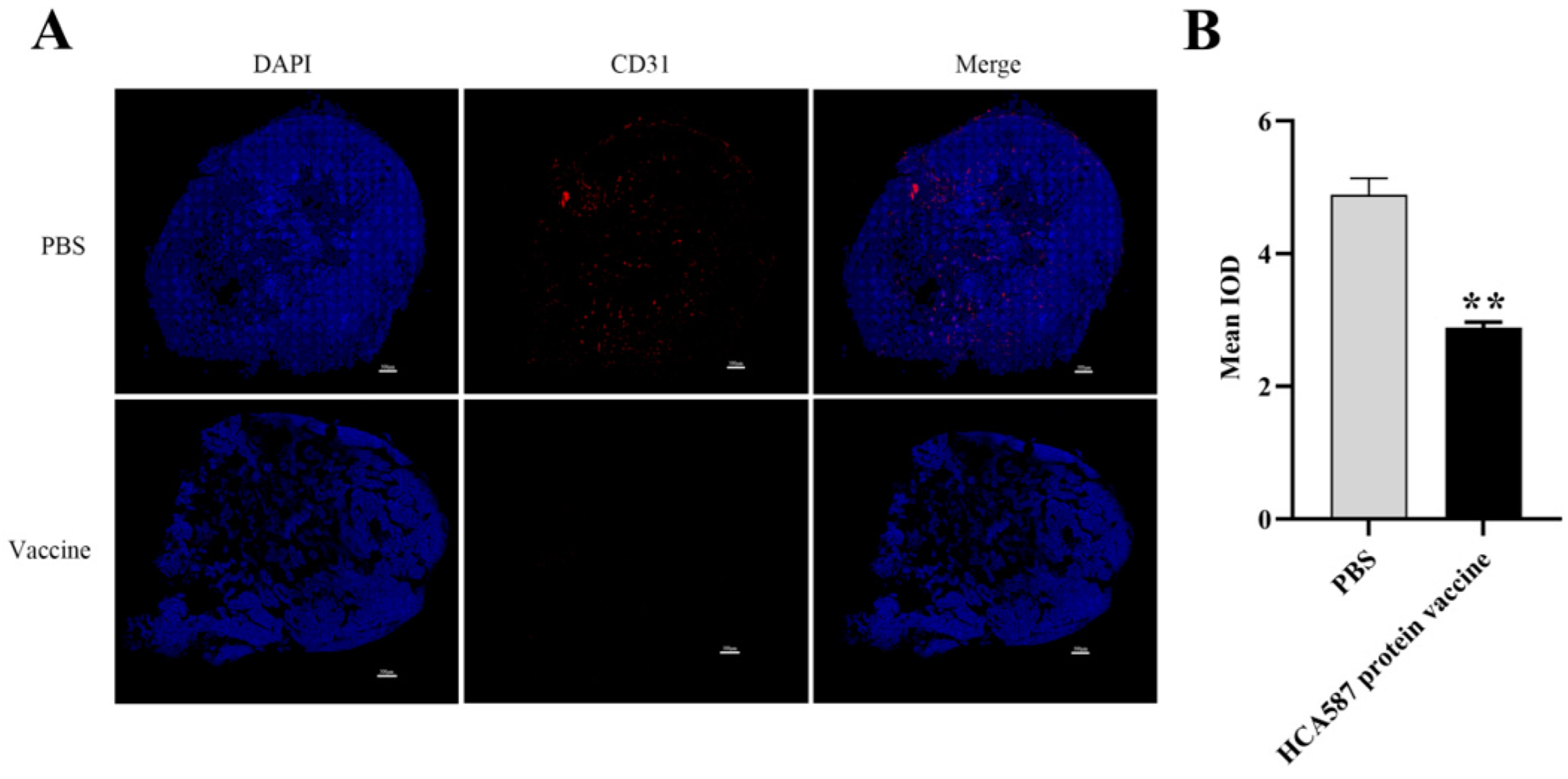

Figure 4.

Reduction of tumor microangiogenesis density. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. As described in Materials and methods, vascular density was determined by the average fluorescence intensity ((Bar= 500 μ m)) in the high power field of sections stained with CD31 antibodies (B). The microvessel density in tumor tissue of mice treated with HCA587 protein vaccine was significantly lower than that of mice treated with protein vaccine (P < 0.0017). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, and ** P < 0.01 compared with those in PBS group.

Figure 4.

Reduction of tumor microangiogenesis density. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. As described in Materials and methods, vascular density was determined by the average fluorescence intensity ((Bar= 500 μ m)) in the high power field of sections stained with CD31 antibodies (B). The microvessel density in tumor tissue of mice treated with HCA587 protein vaccine was significantly lower than that of mice treated with protein vaccine (P < 0.0017). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, and ** P < 0.01 compared with those in PBS group.

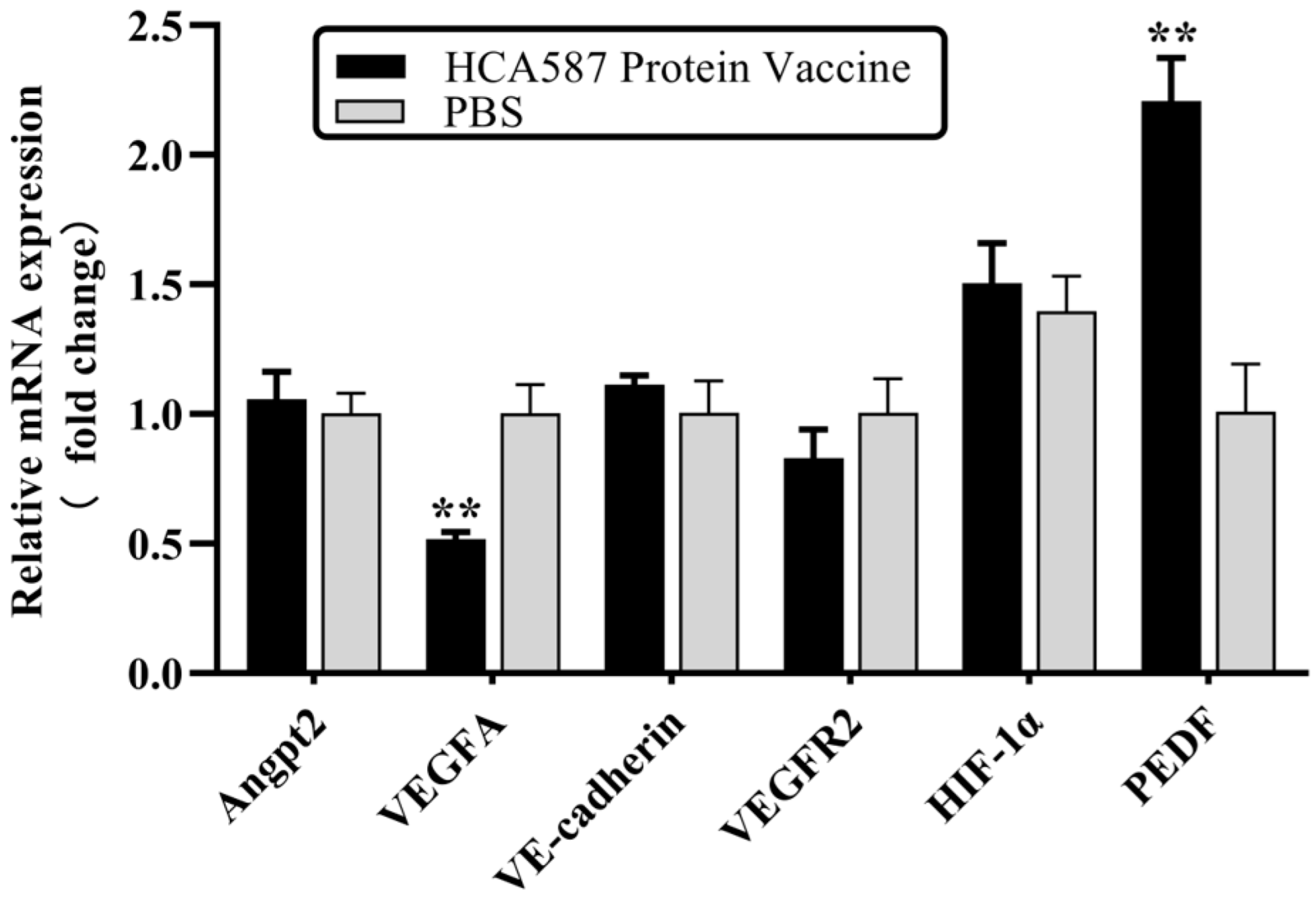

Figure 5.

HCA587 protein vaccine upregulates the transcription level of PEDF. One week after the last vaccine treatment, the mice were killed and RNA was extracted from tumor tissue. The mRNA expression of angiogenesis-related molecules in tumor tissues was detected by RT-qPCR. The transcriptional level of PEDF in HCA587 protein vaccine group was increased (P = 0.0048), and the transcriptional level of VEGFA was down-regulated (P = 0.0018). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, and ** P < 0.01 compared with those in PBS group.

Figure 5.

HCA587 protein vaccine upregulates the transcription level of PEDF. One week after the last vaccine treatment, the mice were killed and RNA was extracted from tumor tissue. The mRNA expression of angiogenesis-related molecules in tumor tissues was detected by RT-qPCR. The transcriptional level of PEDF in HCA587 protein vaccine group was increased (P = 0.0048), and the transcriptional level of VEGFA was down-regulated (P = 0.0018). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, and ** P < 0.01 compared with those in PBS group.

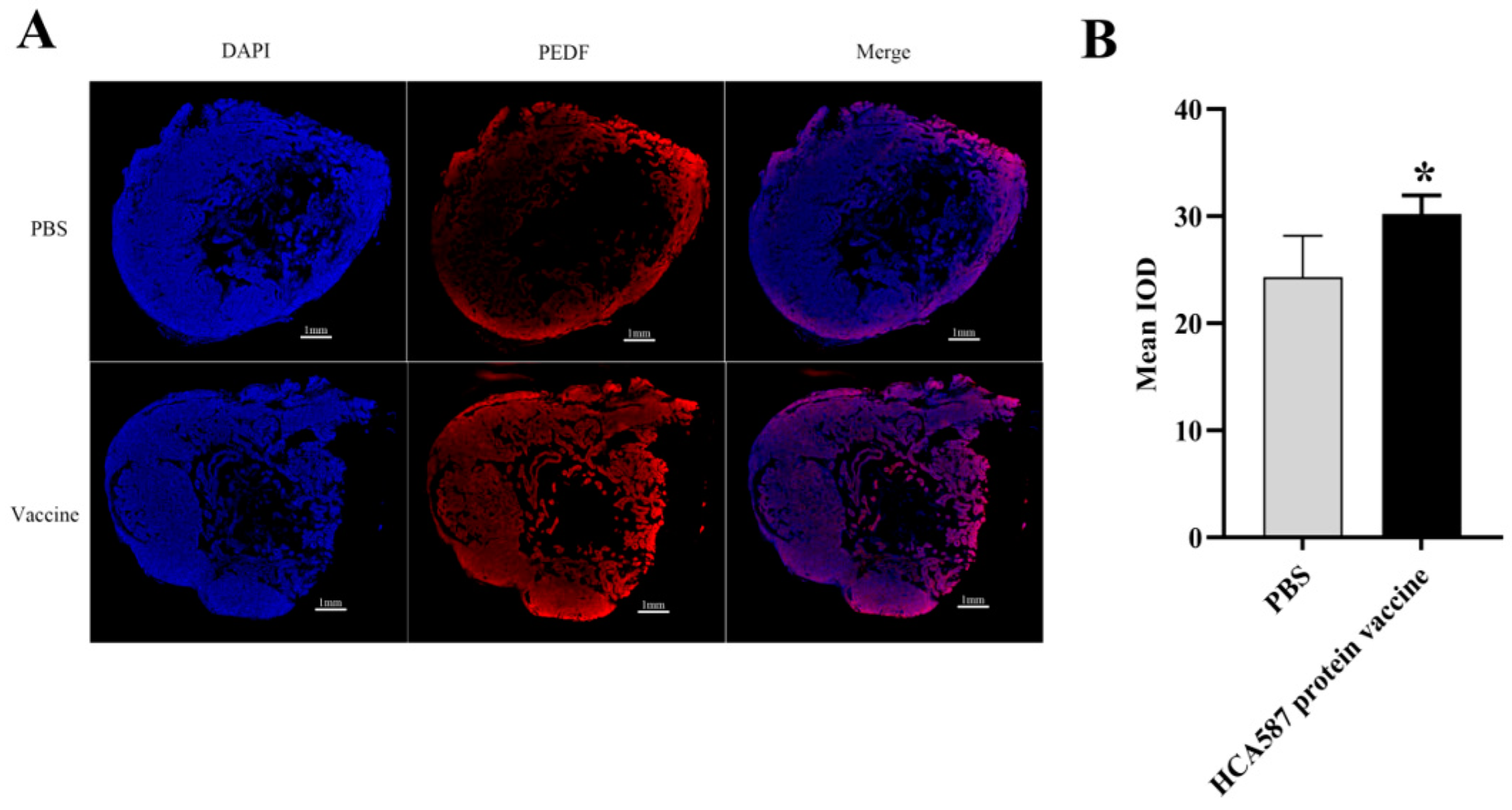

Figure 6.

Enhanced expression of PEDF protein in tumor tissue. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. According to the description in “Materials and methods”, the expression intensity of the protein was determined by the average fluorescence intensity of (Bar=1mm) in the stained section (B,D). The level of PEDF protein increased (P = 0.0179) and the level of VEGFA protein decreased in HCA587 protein vaccine group (P < 0.0001). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 and P < 0.001 compared with PBS group.

Figure 6.

Enhanced expression of PEDF protein in tumor tissue. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment. According to the description in “Materials and methods”, the expression intensity of the protein was determined by the average fluorescence intensity of (Bar=1mm) in the stained section (B,D). The level of PEDF protein increased (P = 0.0179) and the level of VEGFA protein decreased in HCA587 protein vaccine group (P < 0.0001). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 and P < 0.001 compared with PBS group.

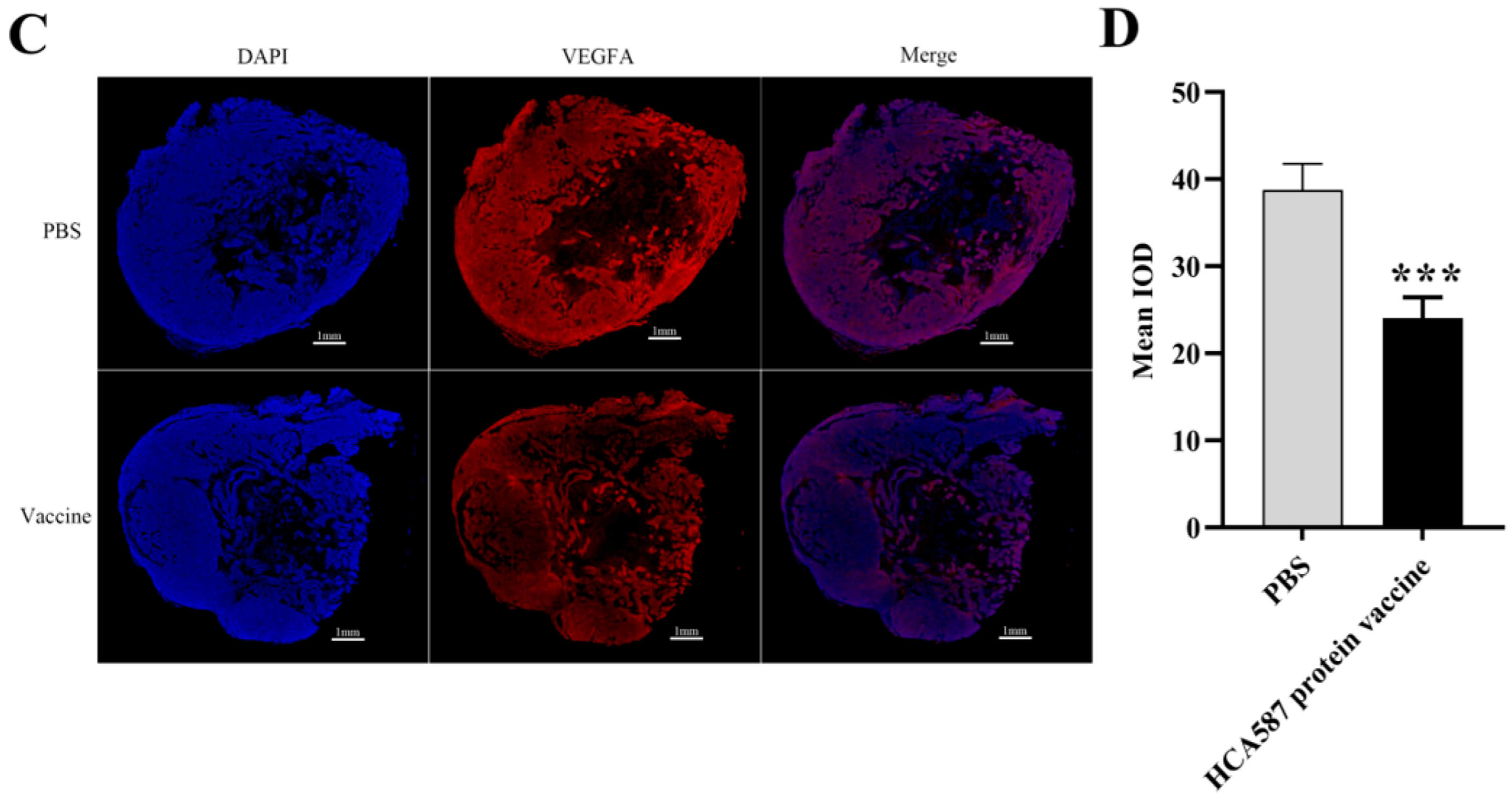

Figure 7.

HCA587 protein vaccine promotes the expression of PEDF protein in tumor tissue. Mice were sacrificed one week after the last vaccine treatment and the tumor tissues were obtained. The protein expression levels of angiogenesis-related molecules in tumor tissues (A,B) were detected by Western-blot, and the expression of different proteins in the two groups were compared by IHC (C). HCA587 protein vaccine upregulated the expression of PEDF protein (P = 0.0333). The data were expressed as mean ±SE, *P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

Figure 7.

HCA587 protein vaccine promotes the expression of PEDF protein in tumor tissue. Mice were sacrificed one week after the last vaccine treatment and the tumor tissues were obtained. The protein expression levels of angiogenesis-related molecules in tumor tissues (A,B) were detected by Western-blot, and the expression of different proteins in the two groups were compared by IHC (C). HCA587 protein vaccine upregulated the expression of PEDF protein (P = 0.0333). The data were expressed as mean ±SE, *P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

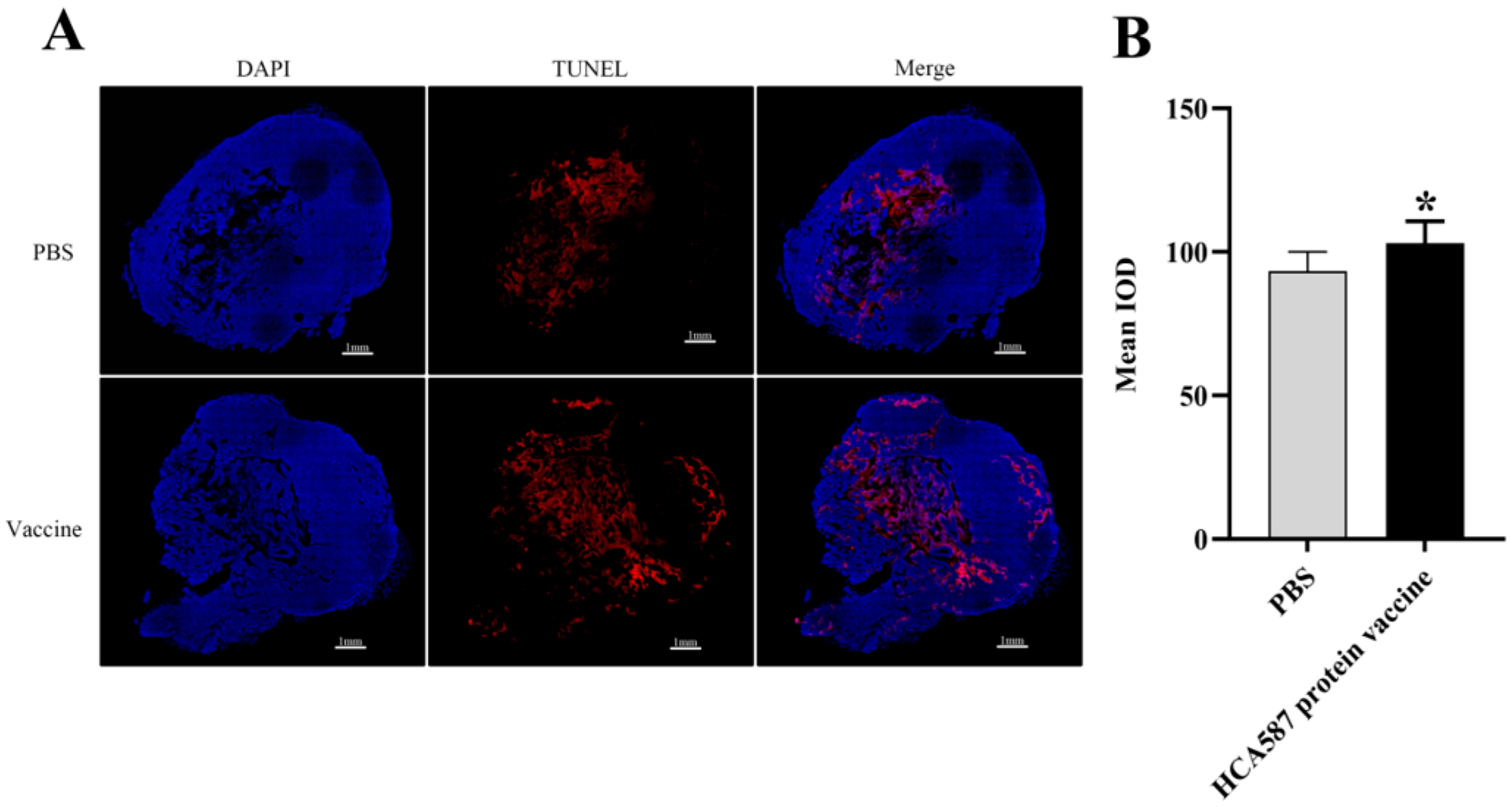

Figure 8.

HCA587 protein vaccine promotes apoptosis in tumor tissue. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment, and the tumor tissue was obtained and made into sections. According to the description in “Materials and methods”, the apoptosis rate of tumor tissue is determined by the average fluorescence intensity of (Bar=1mm) in the stained section (B). The apoptotic area of tumor tissue was significantly increased in HCA587 protein vaccine group (P = 0.0158). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

Figure 8.

HCA587 protein vaccine promotes apoptosis in tumor tissue. The mice were killed a week after the last vaccine treatment, and the tumor tissue was obtained and made into sections. According to the description in “Materials and methods”, the apoptosis rate of tumor tissue is determined by the average fluorescence intensity of (Bar=1mm) in the stained section (B). The apoptotic area of tumor tissue was significantly increased in HCA587 protein vaccine group (P = 0.0158). The data were expressed as mean ± SE, * P < 0.05 compared with PBS group.

Figure 9.

HCA587 protein vaccine activates p38/Bax/caspase3 apoptosis signal transduction pathway in tumor tissue. One week after the last vaccine treatment, the mice were killed and the protein from the tumor tissue was extracted. The protein expression levels of apoptosis-related molecules in tumor tissues were detected by Western-blot (A,B). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 compared with PBS group.

Figure 9.

HCA587 protein vaccine activates p38/Bax/caspase3 apoptosis signal transduction pathway in tumor tissue. One week after the last vaccine treatment, the mice were killed and the protein from the tumor tissue was extracted. The protein expression levels of apoptosis-related molecules in tumor tissues were detected by Western-blot (A,B). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 compared with PBS group.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the PEDF-mediated pro-apoptosis pathway. The figure is reproduced from the literature [

49] and shows concise information from different sources [

34,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48]. PEDF induces apoptosis through FasL and p38 signals, activates c-FLIP through JNK, activates p53 through PPARγ, directly stimulates Bax, and inhibits Bcl-2. DISC: Death-inducing signaling complex.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of the PEDF-mediated pro-apoptosis pathway. The figure is reproduced from the literature [

49] and shows concise information from different sources [

34,

43,

45,

46,

47,

48]. PEDF induces apoptosis through FasL and p38 signals, activates c-FLIP through JNK, activates p53 through PPARγ, directly stimulates Bax, and inhibits Bcl-2. DISC: Death-inducing signaling complex.

Table 1.

Primers used in RT-qPCR experiments (murine-derived).

Table 1.

Primers used in RT-qPCR experiments (murine-derived).

| Primer name |

Primer sequence |

| Angpt2 Forward Primer |

TGACAGCCACGGTCAACAAC |

| Angpt2 Reverse Primer |

ACGGATAGCAACCGAGCTCTT |

| VEGFA Forward Primer |

ACGACAGAAGGAGAGCAGAAG |

| VEGFA Reverse Primer |

ACACAGGACGGCTTGAAGAT |

| VEGFR2 Forward Primer |

GTCCGAATCCCTGCGAAGTACCT |

| VEGFR2 Reverse Primer |

TGGGACATACACAACCAGAGA |

| VE-cadherin Forward Primer |

GCAATGGCAGGCCCTAACTTTC |

| VE-cadherin Reverse Primer |

CAGCAAACTCTCCTTGGAGCAC |

| HIF-1αForward Primer |

ACCTTCATCGGAAACTCCAAAG |

| HIF-1αReverse Primer |

CTGTTAGGCTGGAAAAGTTAGG |

| PEDF Forward Primer |

CCCTTGACAGGAAGTATGAG |

| PEDF Reverse Primer |

TGCTGAAGTCGGGTGATT |

| CD31 Forward Primer |

GAGCCCAATCACGTTTCAGTTT |

| CD31 Reverse Primer |

TCCTTCCTGCTTCTTGCTAGCT |

| GAPDH Forward Primer |

CTGAACGGGAAGCTCACTG |

| GAPDH Reverse Primer |

CATACTTGGCAGGTTTCTCCAG |