1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF), a condition in which the heart is unable to deliver a sufficient amount of blood to peripheral tissues and meet oxygen requirements while maintaining venous inflow, is the leading cause of death in developed countries (North America and Europe) [

1,

2]. More than 64 million people suffer from HF, half of which have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The prevalence in the general population is 1-3%. The 1-year mortality rate is 15-30% [

1]. The clinical presentation of patients with HF is characterized by dyspnea, orthopnea, fatigue and peripheral oedema. They very often suffer from depression and poor quality of life and are often re-hospitalized, and rehabilitation of such patients has not been well studied [

3,

4,

5]. The aim of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is to improve the function of the cardiovascular system (CVS) [

6]. CR is carried out using exercise therapy according to the patient’s capabilities. Programs are administered individually according to intensity, duration and frequency. The rehabilitation of cardiac patients has developed over time, from guidelines for CV rehabilitation to I A recommendations from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association [

7]. According to the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACMS) guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation, the usual treatment consists of short walks with a progressive increase in the distance 3-4 times per day and upper extremity exercises, however, the time and duration of therapy are unknown [

8]. The Early Rehabilitation in Cardiology-Heart Failure (ERIC-HF) approach is safe and feasible [

6], with exercises lasting 5-20 minutes each day, 5 days a week, and is frequently used in the early rehabilitation of hospitalized patients and research. Our rehabilitation program is similar: we start with breathing exercises and peripheral circulation exercises. Then, exercises for the upper and lower extremities are introduced. Gradual verticalization begins in bed, progressing to standing and walking with a therapist or assistance.

Researchers from around the world, Dr. Kitzman et al., have shown that three months of rehabilitation significantly improved physical fitness and quality of life, and reduced depression in elderly HF patients [

5]. In 2021, the German Society of Cardiology and the German Association for Preventive Rehabilitation created an exercise program for patients with heart failure. The research involved 12 patients with LVEF<45%, NYHA functional class II and III, who engaged in a weekly, 1-hour supervised exercise with a physician for one year. Subsequent checks at 4, 8, and 12 months showed a significant rise in LVEF, improvement in quality of life, decrease in total cholesterol and decrease in BNP levels. The rise in exercise capability and 6-minute walk test (6MWT) both displayed upward trends, however, they were not statistically significant. In the rehabilitation process, there were no negative cardiovascular (CV) incidents [

9]. Delgado et al. investigated the effects of an aerobic exercise program (kinesitherapy) on patients with decompensated HF during early rehabilitation. Their study, involved 257 patients with reduced LVEF and NYHA III and IV functional class. While hospitalized, patients participated in a regimen of aerobic activities, including breathing exercises, walking, using an ergo bike, and climbing stairs, twice a day, five times a week, tailored to their individual capacities. The study demonstrated a significant increase in walking distance, as measured by the 6MWT, and an improvement in functional independence, as assessed by the Barthel Index [

10]. In Meta-analysis, Chinese researchers reviewed 6 randomized controlled trials involving 668 patients with acute decompensated HF (LVEF<40%) who underwent early rehabilitation, sourced from PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, and WANFANG databases up to July 2022. They found a significant improvement in exercise capacity, as indicated by higher scores in the 6-minute walk test (6MWT) and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) in the intervention group compared to the control group. Additionally, the rate of readmission was significantly lower in individuals who received early rehabilitation [

11]. Previous studies have confirmed that acupuncture (AP) has an analgesic and immunomodulating impact by activating the nervous system [

12,

13]. AP has been shown to have sympatholytic, vasodilatory, and cardioprotective properties, potentially enhancing heart function in HF patients [

14,

15]. A meta-analysis conducted in October 2019 by Chinese researchers, which involved 32 randomized controlled trials with a total of 2499 patients, outlined the beneficial effects of AP in HF. They contrasted patients who got regular drug treatment with those who got AP alongside drugs. In a study, patients who were given AP showed a significant improvement in LVEF, minute volume, and 6MWT along with a decrease in BNP levels [

16]. BNP is important in predicting and diagnosing heart failure [

17]. There is limited research on the combined effects of kinesitherapy and acupuncture in early rehabilitation for HF patients with cardiac decompensation. In this study, we aim to examine how the combined impact of AP and exercise compares to the impact achieved through exercise alone.

2. Materials and Methods

The intended study is a future, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial with two experimental groups and one control group, using a placebo for comparison. Patients will be followed up for 5-10 days, with the study lasting from January 2022 to May 2024. The study was carried out at the Cardiology Clinic of the Military Medical Academy (MMA).

Eligibility criteria:

Patients admitted for decompensated HF were chosen based on clinical presentation, medical history, and echocardiographic findings within the first 72 hours. They were diagnosed with chronic heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF<40%) and NYHA II or III functional classes [

18,

19]. The minimum LVEF for the research is 15%. Following stabilization of hemodynamics and successful response to diuretics, patients were sorted into 3 groups within 72 hours of being admitted to the hospital.

Control group C of participants: participants receiving standard drug treatment. The optimal therapy which has a class I recommendation as of 2021 includes four groups of medications: beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists or valsartan-sacubitril, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, and SGLT-2 receptor inhibitors [

20,

21].

Experimental patient group E1: in addition to optimal drug therapy, received a standardized daily kinesitherapy program tailored to each individual, similar to that used in early rehabilitation for CV patients following cardiac procedures, acute myocardial infarction, and other heart-related diseases. Kinesitherapy is tailored to each individual, lasting between 5 to 10 days, based on the patient’s health status. Patients completed the exercises while lying down, sitting, or standing based on their overall health and capacity to participate in the activities outlined in the A test. Breathing techniques, exercises for circulation in the extremities, and exercises for the arms and legs were utilized. Patients with compensated heart failure began Kinesitherapy (KTH) within 72 hours of admission, while those with decompensated heart failure started rehabilitation once they became compensated. In the E1 experimental group, patients were given drug therapy and kinesitherapy in addition to placebo acupuncture. Acupuncture placebo involves placing tubes or guides close to, but not directly on, the acupuncture point or channel. The tubes are attached by using double-sided adhesive patches, with shorter acupuncture needles inserted into them to prevent piercing the skin.

Experimental patient group E2: In addition to optimal drug therapy, this group followed a kinesitherapy program based on the same principles as the E1 group combined with classic AP. In our study, we utilized AP points, which are commonly applied in the care of CV patients as per classical theory and prior studies. Neiguan (PC 6), Shenmen (HT 7), Hegu (LI 4), Shanzhong (RN 17), Yinlingquan (Sp 9) on both sides, Zusanli (ST 36), and Baihui (Du 20) are acupuncture points used to boost heart function, enhance urination, and lower stress [

22]. An experienced acupuncturist-physiatrist applied AP after graduating from the School of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) at the II Military University in Shanghai, PR China, in the academic year 2006/07. The needles were left in place for 20 minutes with no extra stimulation. Fresh sterile acupuncture needles were utilized. The needles from the Chinese brand “Hwato” have measurements of 30 mm in length and 0.3 mm in thickness. Every individual patient had a collection of needles. The AP took place within 5-10 business days.

Exclusion criteria for the study:

Patients admitted to the hospital within the last month due to a heart attack and/or myocardial revascularization, scheduled for heart surgery, diagnosed with malignant disease, immobile (excluding certain conditions), anemic with hemoglobin levels below 90 g/l, having other comorbidities hindering physical therapy, uncooperative, and exhibiting a Mini-Mental State score below 24 (which is assessed by a speech therapist specializing in psychological testing). Exclusion criteria included abnormal vital signs: blood pressure above 180/120 mmHg and below 90/60 mmHg, heart rate of 130/min or higher, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation within 72 hours and fever.

The research examines the dependent variables:

1. Parameters for cardiological monitoring included blood pressure, heart rate and BNP (natriuretic peptide type B). BNP levels are measured from venous blood before and after treatment. 2. Physiatric monitoring factors: The A-test monitors and evaluates 10 activities, including those performed while in bed, standing, moving, and walking. The ratings for each task range from 0 (not fully accomplished) to 5 (completely autonomous and secure), with a total possible score of 50. A higher total score indicates a higher level of functionality for the patient. This assessment covers all early rehabilitation activities, including moving in bed, sitting on the bed, using the restroom, standing, and walking with assistance or unassisted. It can be used to assess functional ability, in case of any disability caused by illness or injury [

23].

The 2-minute walking test (2MWT) and 6-minute walking test (6MWT) assessed the examinee’s strength and endurance. This examination was performed on each patient at both the start and conclusion of the follow-up period, which corresponds to the therapy phase. The number of meters walked is calculated either within two minutes or within six minutes, based on the patient’s level of endurance. If the patient cannot finish the 2MWT, the score for walking distance is recorded in the walking endurance section of Test A. A score of 0 indicates the patient is unable to walk, while a score of 1 means they can walk up to 5 m. A score of 2 indicates walking up to 15 m, a score of 3 up to 50 m, a score of 4 up to 100 m, and a score of 5 over 100 m [

24,

25].

Sample Size

The size measurement for three separate samples was determined with a 6% margin of error and an 80% confidence level, for the distribution of individuals among the groups in a 1:1:1 ratio. There are at least 114 respondents in total, split evenly into three groups. All groups consist of 38 units each, which satisfies the requirement for large statistical samples as mentioned by Kovačević-Kostić (2015) [

26]. To confirm the data, the study sample size was determined using the Raosoft online calculator (Raosoft, 2021) [

27]. Additional patients will be included because some patients may not meet the criteria for research inclusion. The formula used to determine the adjusted sample size is n1=n/(1-e), where n is the original sample size, n1 is the adjusted sample size, and e is equal to 10% of the original sample size (Sakpal, 2010) [

28]. The revised sample size is N=127. The document will detail all the factors leading to attrition of the research (fatal consequences, deterioration of the primary condition, additional issues like COVID-19, personal and familial motives for discontinuation, etc.), categorized by patient groups.

Statistical Analysis

Frequencies and percentages are used to describe categorical variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to assess the normality of the distribution of numerical variables. Because the variables didn’t satisfy the normality criterion, the Median and Interquartile ranges were utilized. Kruskal Wallis Test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare differences among groups. The differences between two or more repeated measurements were tested using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test and Friedman Test. The Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between categorical variables. We used a combined analysis of variance (SPANOVA) to see if the change in test outcomes measured at admission and discharge varies by respondent group. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 is available. Data analysis was conducted using IBM Corp. in Armonk, NY, USA.

Ethical Committee of the Military Medical Academy Belgrade approved the study at its meeting (decision number 56/2022), and all patients provided their written consent for the participation.

3. Results

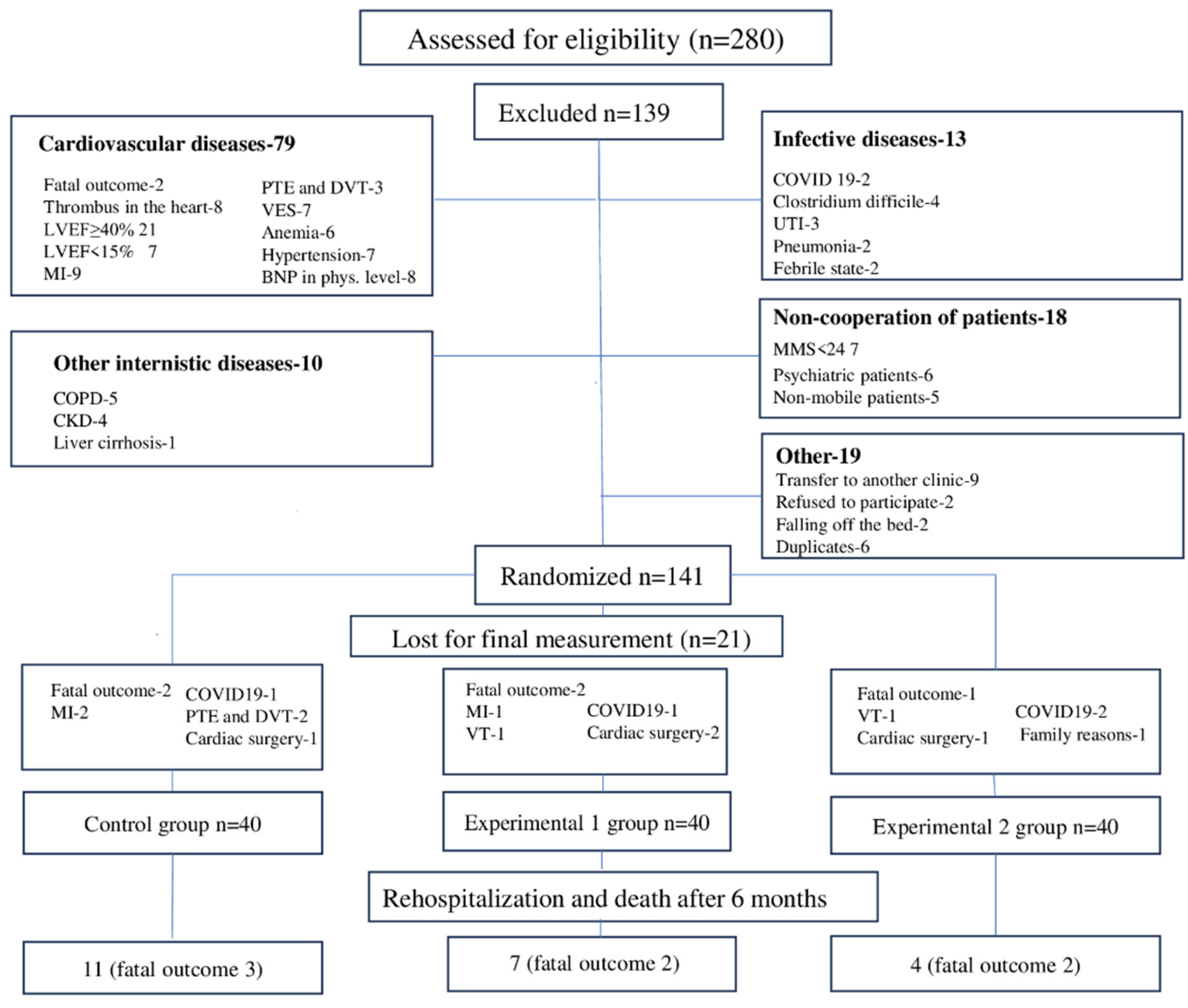

A total of 280 patients were assessed for eligibility. Among them, 139 patients did not meet the criteria to enter the study, primarily due to cardiovascular diseases (56.83%), followed by poor general conditions related to other internal medicine conditions (7.19%), infectious syndromes (9.35%), poor patient cooperation (12.94%), and other reasons (13.67%). Additionally, 21 patients dropped out during the study. The study flow chart is presented in

Figure 1.

A total of 120 participants were involved in the study, among them 40 patients were on medication therapy as well as adapted kinesitherapy and acupuncture. Respondents have an average age of 74.0 years, with an interquartile range of 11.7 years, and 73.3% are men. Arterial hypertension is the most prevalent coexisting medical condition (70.0%). The median LVEF value is 32.0 with an interquartile range of 9.5, while 83.3% of patients are in the NYHA III stage. All the mentioned parameters show that the three groups are similar in terms of uniformity (

Table 1).

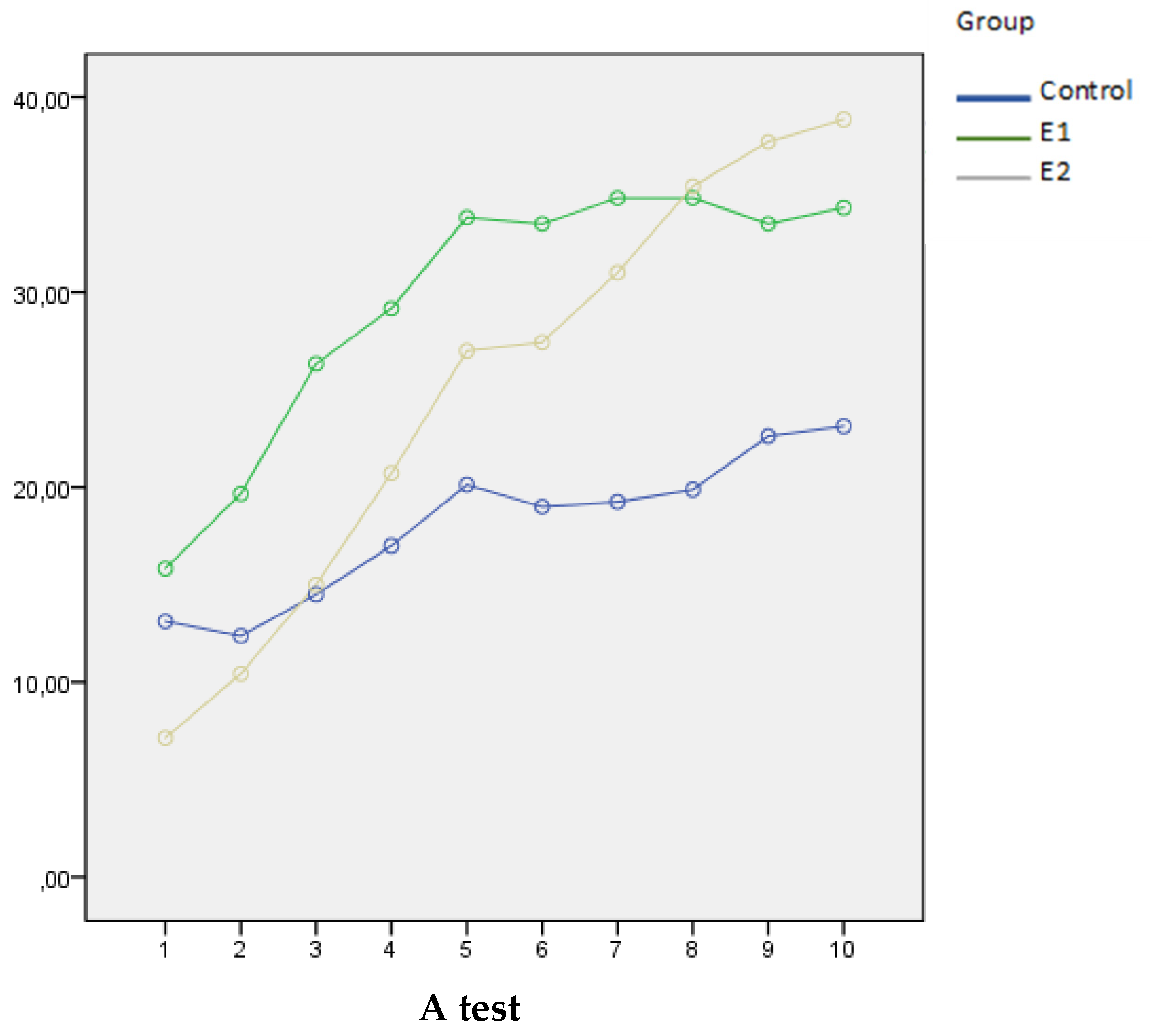

The comparison between the three groups in the functional status measured by the A test during 10 days is presented in

Table 2. There was a significant improvement in the functional status of all groups on the 5th and 10th days of measurement (p< 0.001). The E2 group showed the largest A test score increase in the percentage, both on the 5th and 10th day, compared to the other two groups. Initially, the three groups were all on an equal playing field in terms of their performance on the test, meaning there were no intergroup disparities. On the 5th day, significant variations were observed between groups E1 and E2 (p = 0.022), with the group E2 displaying superior outcomes (Me = 35.5 (IQR = 14.0)) in comparison to the E1 group (Me = 30.5 (IQR = 10.5)). Both groups surpassed the C group by the 5th day, with a significance level of p < 0.001. By day 10, E1 (Me = 35.0 (IQR = 12.0)) and E2 (Me = 41.0 (IQR = 13.0)) groups showed superior results in the A test compared to the C group (Me = 25.0 (IQR = 11.2)), with p values of 0.045 and 0.005, respectively. The E1 and E2 groups had comparable functional status on the 10th day.

After five days, a higher percentage of patients in the E2 group achieved an A test score of 30 or above, compared to the E1 and C groups (80% vs. 50% vs. 10%, respectively; p<0.01), indicating functional independence, the ability to walk, and eligibility for hospital discharge.

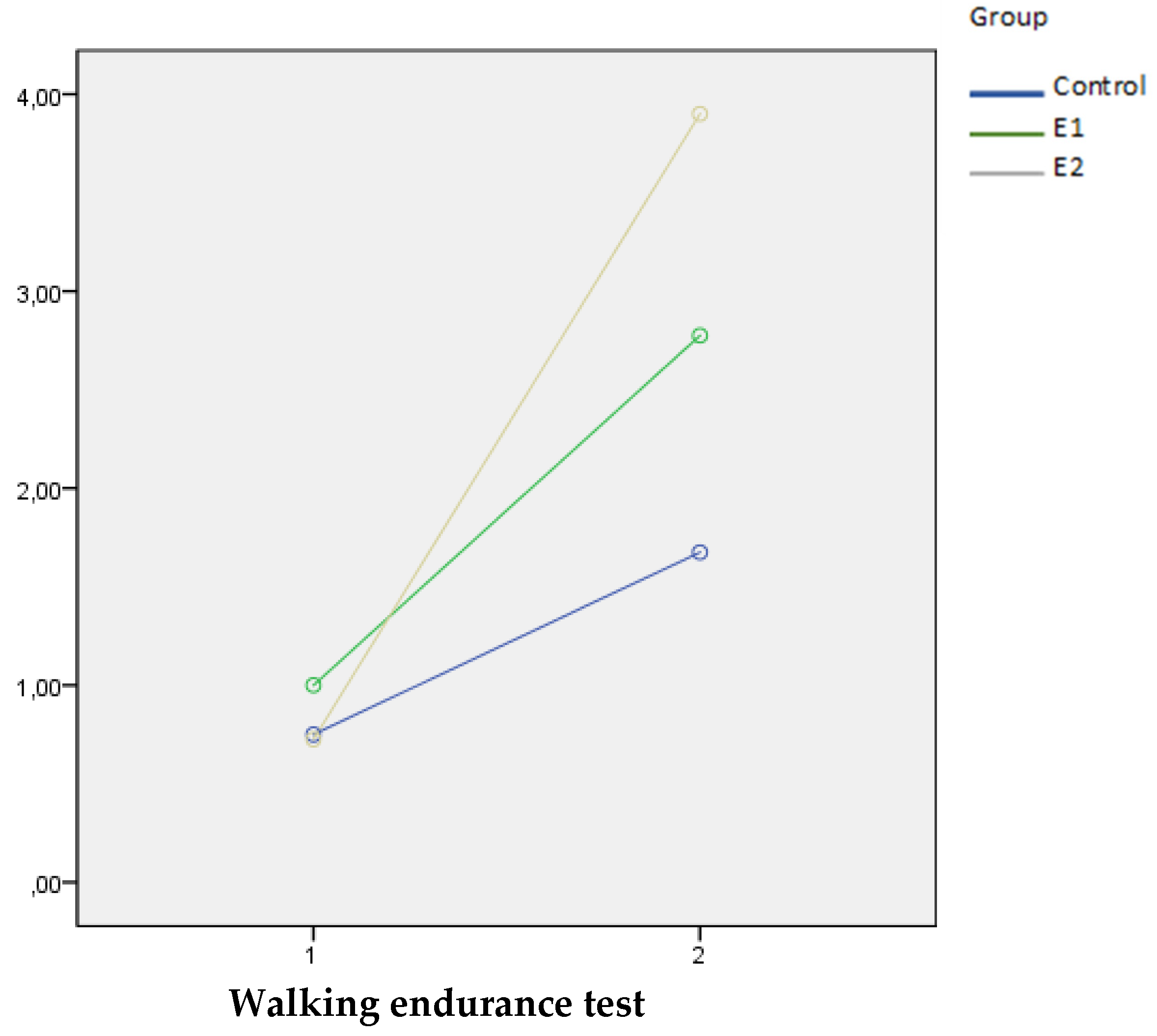

The comparison between the three groups in the 2MWT, 6MWT and endurance walking test between admission and discharge, along with within-group comparisons, is presented in

Table 3.

There wasn’t a significant improvement in 2MWT between admission and discharge within the C group. The E1 group improved from a distance of median = 7.62 (IQR = 6.0) at admission to a median = 50.0m (IQR = 85.0) at discharge (p < 0.001). The E2 group increased from a distance of median = 5.0m (IQR = 0.0) at admission to a median = 120.0m (IQR = 63.0) at discharge (p = 0.001). The distance walked within 2 minutes at discharge differed significantly between the E1 and E2 groups (p ˂ 0.001), indicating that the E2 group performed better. Both experimental groups performed better in 2MWT at discharge than the control group (p < 0.001). There was no difference between the three groups in the 2MWT at admission.

In 6MWT the E1 group improved from a distance of median = 90.0m (IQR = 20.0) at admission to a median = 190.0m (IQR = 85.0) at discharge (p = 0.042). The E2 group improved from a distance of median = 80.0m (IQR = 75.0) at admission to a median = 310.0m (IQR = 40.0) at discharge (p = 0.042). Patients in the E2 group covered longer distances in the 6MWT compared to those in the E1 group, both at admission (p = 0.033) and at discharge (p = 0.016).

Upon admission to the hospital, all groups showed similar endurance walking test results. The endurance walking test demonstrated improvement in all groups from admission to discharge (p < 0.001). After discharge, both experimental groups demonstrated significantly better results in endurance walking test compared to the control group, with the E2 group also showing significantly better results than the E1 group (p < 0.001).

The SPANOVA test showed that combination of KTH and AP in E2 group improves functionality at discharge the most, compared to the other two groups, as assessed by the A test (Wilks’ lambda = 0.035, F = 4.840, p < 0.001, η²=0.813), Graph 1. Also, KTH and AP combined resulted in a significantly greater improvement in the walking endurance test compared to the other two groups (Wilks’ lambda = 0.496, F = 59.50, p < 0.001, η²=0.504), Graph 2. All squared eta (η²) values are high, indicating that the kind of therapy (KTH and AP) has a strong combined effect on the change in results when comparing the values at admission and discharge.

Graph 1.

The mean values of the A test during the study in three examined groups.

Graph 1.

The mean values of the A test during the study in three examined groups.

Graph 2.

The median values of the walking endurance test in admission and discharge in three examined groups.

Graph 2.

The median values of the walking endurance test in admission and discharge in three examined groups.

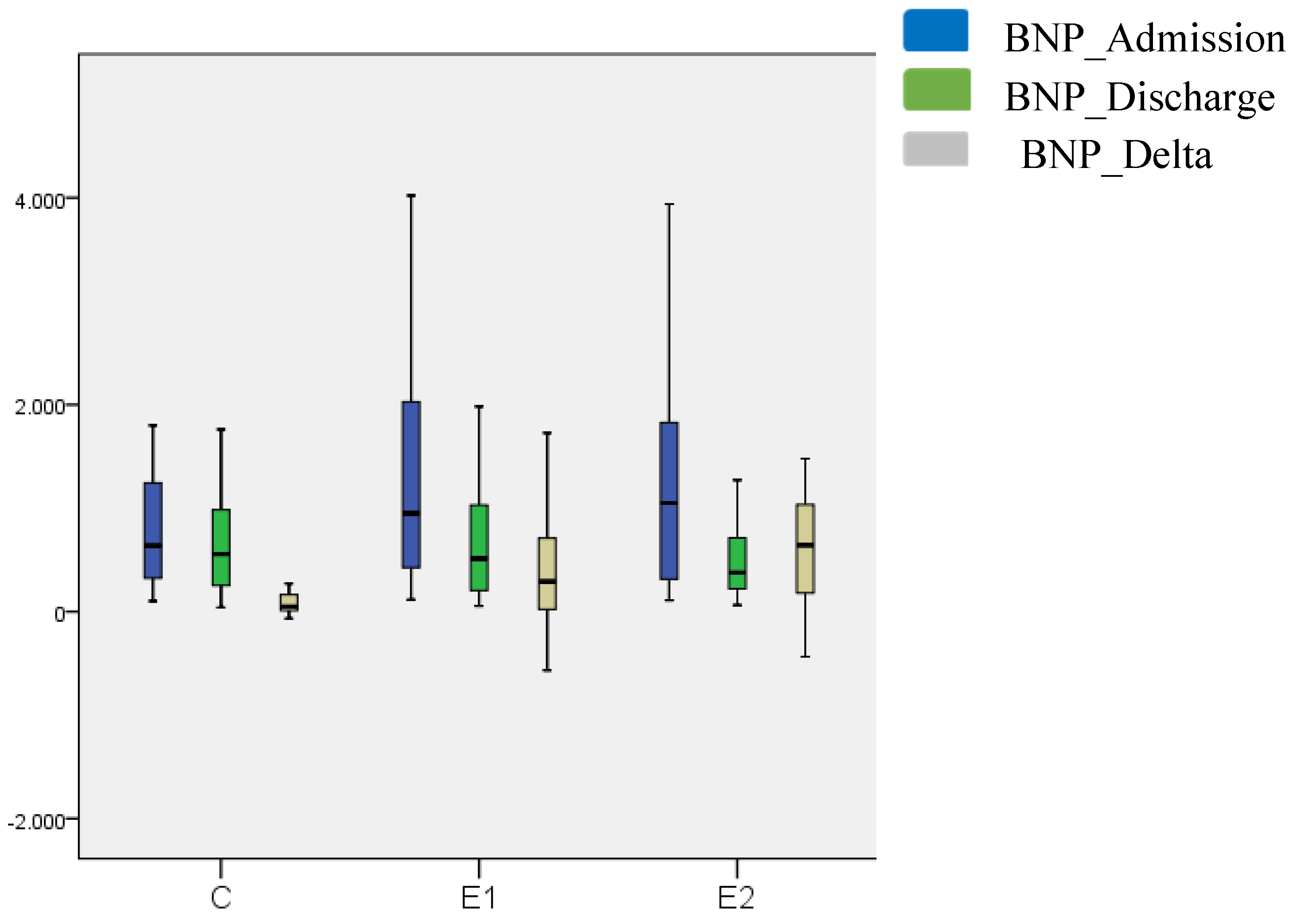

In the E2 group, blood concentrations of BNP decreased more pronouncedly from admission to discharge, compared to E1 and C groups (64.1%, 46.0%, 12.9%, respectively). The groups had the same average BNP upon admission. There were variances in the BNP delta discrepancy in measurements between C vs. E1 (p = 0.001) and C vs. E2 (p < 0.001). There was no difference between the C and E1 groups (

Figure 2).

Differences between the three groups in the duration of hospitalization and follow-up are presented in

Table 4. There was no difference in the average number of hospital days among the three groups. Similarly, there was no significant difference among the groups in the number of days required for monitoring and rehabilitation. Patients in the control group spent an average of 9.00 days in the hospital, compared to 8.00 days in group E1 and 10.00 days in group E2. The mean follow-up days in the C group and the rehabilitation days in the experimental groups are equal to 6.00.

The C group had the highest composite rate of all-cause death and rehospitalization due to worsening heart failure, reaching 27.5% six months after discharge, followed by the E1 group at 17.5% and the E2 group at 10%. Mortality rates showed no significant differences among the groups (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

Our study is the first prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial in patients with HF and reduced LVEF after decompensation, demonstrating the combined effects of AP and KTH in early rehabilitation. Patients receiving combined therapy (AP and KTH) alongside pharmacological treatment exhibited the fastest functional recovery after 5 days of rehabilitation, as shown by improvements in the A test, 2-minute and 6-minute walk tests, and walking endurance test. The E2 group, which received both AP and KTH, achieved functional independence earlier than the other groups, highlighting the additive effect of AP on KTH, which serves as the foundation of rehabilitation.

Functional recovery was evaluated using the Barthel index, a tool for assessing functional independence in daily activities such as eating, dressing, and walking. The Barthel index is commonly used in acute heart diseases [

29] and cardiac rehabilitation [

30], and it is a predictor of mortality in HF. A Barthel index score below 85 at discharge is associated with increased mortality [

31]. While the Barthel index is effective for broad evaluations, prior research revealed that the A test is often superior for detecting daily changes in functional status [

23]. Originally designed for trauma and orthopedic patients, the A test has been adapted for cardiac rehabilitation since 2012. It identifies patients who are progressing or lagging in functional recovery during therapy [

24]. Patients should be assessed based on the type and severity of their functional disability rather than solely on their diagnosis [

25,

32,

33].

By day 4, patients in the E2 group achieved the same functional capacity (A = 30.5) that the E1 group reached on day 5, indicating earlier readiness for discharge (

Table 2). This represents a significant improvement, potentially reducing treatment costs and hospital-acquired infections. After 5 days, the E2 group reached optimal functional recovery (A = 35.5). From day 5 to day 10, functional improvement continued across all groups, albeit at a slower rate. By day 10, the E2 and E1 groups had comparable functional statuses, while the C group lagged significantly. The C group’s A test score increased from 22 on day 5 to 25 on day 10, indicating much slower recovery and uncertain full recovery. These findings emphasize the importance of early rehabilitation for all HF patients, ideally combining exercises with AP where feasible.

Achieving functional independence by day 5 was critical. Patients with A test scores above 30 were considered functionally ready for discharge. In the E2 group, 80% of patients (32/40) could independently get out of bed, use the restroom, and walk. In the E1 group, 50% of patients met these criteria, compared to only 10% in the C group.

The walking endurance test, a component of the A test, showed that at discharge, the E2 group outperformed the E1 group, with an average walking endurance grade of 4 (able to walk up to 100 meters) compared to grade 3 in the E1 group (able to walk up to 50 meters). The C group achieved a grade of 1.5 (5-15 meters), reflecting significant but limited improvement. At admission, most patients in all groups were bedridden or could only walk up to 5 meters within their rooms (grades 0-1).

The 2MWT is well-suited for assessing functional capacity in geriatric patients and those recovering from heart surgery or acute myocardial infarction [

34]. However, it is less sensitive and correlates less strongly with daily living activities compared to the 6MWT [

35]. The 2MWT is particularly useful for NYHA class III and IV patients [

36]. The average distance covered by healthy individuals aged 70–74 in the 2MWT is 172.2 meters for men and 145.9 meters for women [

37]. Similarly, 6MWT distances vary by age and gender, ranging from 400 to 700 meters [

38], with men walking 30 meters farther than women on average [

39].

The E1 group achieved 60 meters more in 6MWT at discharge compared to the C group (

Table 3), which is similar to the results obtained in Bruno Delgado’s study [

10], where the difference between the experimental group that exercises and the control group is 59 meters. However, in our study, no significant difference was observed between the E1 and C groups in the 6MWT, likely due to the small sample size of the C group, which consisted of only two patients. In a study by Dr. Johannes Beck and colleagues at the University Hospital in Heidelberg, 17 subjects undergoing classical AP demonstrated a 32-meter improvement in the 6MWT compared to the placebo AP group [

40]. In our study, the difference between the groups receiving classic AP and KTH and the placebo AP and KTH was 120 meters, a significant result.

The 6MWT was the most demanding test, with only 12 patients completing it upon admission—five from each of the E1 and E2 groups, and just two from the C group. In contrast, 46 patients completed the 2MWT (14 from the E1 group, 13 from the E2 group, and 19 from the C group), while 62 patients were unable to walk upon admission. The endurance walking test was the most comprehensive, administered to all 120 patients at both admission and discharge. A potential modification to improve its accuracy for patients with severe clinical conditions who cannot walk upon hospital admission could involve measuring the distance walked without a time limit for small distances (up to 100 meters), avoiding the graded intervals used in the current method.

The meta-analysis mentioned in the introduction reported a significant increase in the 6MWT (MD = 43.6, 95%CI = [37.43, 49.77], I2 = 0%, p < 0.0001) and a reduction in BNP (MD = −227.99, 95%CI = [−337.30, −118.68], I2 = 96%, p < 0.0001) between patients treated with acupuncture and those receiving only medical therapy [

16]. In a separate meta-analysis of 565 patients with HF, Neil Smart et al. found that kinesitherapy reduced BNP levels by 28.3%, with the greatest reductions observed in patients with an LVEF <34% [

41]. Our study, with a mean EF of 32%, found the E2 group exhibited the highest BNP reduction compared to the E1 and C groups. (

Figure 2).

In a meta-analysis of acute heart failure studies conducted by Chinese authors, acupuncture reduced intensive care unit (ICU) stay by 2.2 days (95% CI 1.26, 3.14) and lowered the probability of rehospitalization to 0.53 (95% CI 0.28, 0.99) [

42]. While our study did not demonstrate a reduction in hospital stays for the experimental groups (

Table 4), we did observe a potential reduction in hospitalization by one day in the E2 group compared to the E1 group. Gordon Reews et al. found that six months post-discharge, patients who had undergone exercise therapy had 29% fewer rehospitalizations than the control group [

43]. Similarly, Dr. Hui Zhong’s study reported a lower rehospitalization rate within six months for the exercise group (12.5%) compared to the control group (23.6%) [

44]. Consistent with these findings, our study showed a reduction in rehospitalization rates six months post-discharge: 5% in the E2 group, significantly lower than 12.5% in the E1 group and 27.5% in the C group (

Table 5). After 6 months of rehabilitation in elderly patients with HF, Kitzman et al. reported nearly twice as many fatalities in the experimental group (15 CV deaths out of 175 patients) compared to 8 CV deaths out of 174 patients in the control group. The total death rate is 6.59% [

5]. In our study, the overall number of deaths after 6 months was 5.83% (7/120), as shown in

Table 5.

Study Limitation

One limitation of this study is the relatively short rehabilitation period, which was limited to 5-10 working days for all patients, including those in the control group. Ideally, the rehabilitation period should have been extended to 10 working days for a more comprehensive evaluation of recovery. The decision to shorten the rehabilitation period was influenced by the constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the circumstances, we opted for a brief early rehabilitation period.

Additionally, during the study, six patients tested positive for COVID-19. Two were diagnosed upon admission and did not participate in the trial, while four were diagnosed during hospitalization and were excluded from the study, falling into the dropout group. All patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection were transferred to the designated COVID hospital for appropriate care.

5. Conclusions

Early kinesitherapy accelerates the functional recovery of patients hospitalized due to decompensated heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Acupuncture synergises with kinesitherapy, and patients undergoing the combination of these two procedures achieve the best early functional recovery. Further research is needed to determine whether the application of combined therapy affects the long-term stability of patients after discharge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and O.S.; methodology I.D. and O.S.; software I.D. and O.S.; validation I.D., K.A. and O.S.; formal analysis, I.D. and O.S.; investigation, I.D., J.Z., M.Z, P.V. and L.B.; resources, I.D., J.Z., M.Z, P.V. and L.B.; data curation, I.D., J.Z., M.Z, P.V. and L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D., K.A. and O.S.; writing—review and editing, K.A. and O.S.; visualization, I.D., K.A. and O.S.; supervision, O.S.; project administration, O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Military Medical Academy Belgrade (decision number 56/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in the present study may be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Savarese, G.; Becher, P.M.; Lund, L.H.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Coats, A.J.S. Global burden of heart failure: a comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res 2023, 118, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.; Brito, D.; Vaqar, S.; Chhabra, L. Congestive Heart Failure; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, Florida, United States, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, I.; Joseph, P.; Balasubramanian, K.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lund, L.H.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Kamath, D.; Alhabib, K.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Budaj, A.; Dans, A.L.L.; Dzudie, A.; Probstfield, J.L.; Fox, K.A.A.; Karaye, K.M.; Makubi, A.; Fukakusa, B.; Teo, K.; Temizhan, A.; Wittlinger, T.; Maggioni, A.P.; Lanas, F.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Silva-Cardoso, J.; Sliwa, K.; Dokainish, H.; Grinvalds, A.; McCready, T.; Yusuf, S. Health-Related Quality of Life and Mortality in Heart Failure: The Global Congestive Heart Failure Study of 23 000 Patients From 40 Countries. Circulation 2021, 143, 2129–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Haehling, S.; Arzt, M.; Doehner, W.; Edelmann, F.; Evertz, R.; Ebner, N.; Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Garfias Macedo, T.; Koziolek, M.; Noutsias, M.; Schulze, P.C.; Wachter, R.; Hasenfuß, G.; Laufs, U. Improving exercise capacity and quality of life using non-invasive heart failure treatments: evidence from clinical trials. Eur J Heart Fail 2021, 23, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzman, D.W.; Whellan, D.J.; Duncan, P.; Pastva, A.M.; Mentz, R.J.; Reeves, G.R.; Nelson, M.B.; Chen, H.; Upadhya, B.; Reed, S.D.; Espeland, M.A.; Hewston, L.; O’Connor, C.M. Physical Rehabilitation for Older Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, B.M.; Lopes, I.; Gomes, B.; Novo, A. Early rehabilitation in cardiology—heart failure: The ERIC-HF protocol, a novel intervention to decompensated heart failure patients rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2020, 19, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.J. Cardiac Rehabilitation—Challenges, Advances, and the Road Ahead. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine. Acsm’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States, 2018; ISBN 9781496339065. [Google Scholar]

- Güder, G.; Wilkesmann, J.; Scholz, N.; Leppich, R.; Düking, P.; Sperlich, B.; Rost, C.; Frantz, S.; Morbach, C.; Sahiti, F.; Stefenelli, U.; Breunig, M.; Störk, S. Establishing a cardiac training group for patients with heart failure: the “HIP-in-Würzburg” study. Clin Res Cardiol 2022, 111, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, B.; Novo, A.; Lopes, I.; Rebelo, C.; Almeida, C.; Pestana, S.; Gomes, B.; Froelicher, E.; Klompstra, L. The effects of early rehabilitation on functional exercise tolerance in decompensated heart failure patients: Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial (ERIC-HF study). Clin Rehabil 2022, 36, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, J.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, L.; Ren, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, P.; Hu, D.; Pang, X.; Jin, Z. Early Exercise-Based Rehabilitation for Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2022, 23, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabýoglu, M.T.; Ergene, N.; Tan, U. The mechanism of acupuncture and clinical applications. Int J Neurosci 2006, 116, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.G.; Kotha, P.; Chen, Y.H. Understandings of acupuncture application and mechanisms. Am J Transl Res 2022, 14, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.M.; Frishman, W.H. Acupuncture and Cardiovascular Disease: Focus on Heart Failure. Cardiol Rev 2018, 26, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, K.J. Neurobiological mechanisms of acupuncture for some common illnesses: a clinician’s perspective. J Acupunct Meridian Stud 2014, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Yan, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Xian, S.; Lu, L. The Effect of Acupuncture and Moxibustion on Heart Function in Heart Failure Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019, 2019, 6074967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, A. B-type natriuretic peptide levels: a potential novel “white count” for congestive heart failure. J Card Fail 2001, 7, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredy, C.; Ministeri, M.; Kempny, A.; Alonso-Gonzalez, R.; Swan, L.; Uebing, A.; Diller, G.P.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Dimopoulos, K. New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification in adults with congenital heart disease: relation to objective measures of exercise and outcome. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2018, 4, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Farmakis, D.; Gilard, M.; Heymans, S.; Hoes, A.W.; Jaarsma, T.; Jankowska, E.A.; Lainscak, M.; Lam, C.S.P.; Lyon, A.R.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Mebazaa, A.; Mindham, R.; Muneretto, C.; Francesco Piepoli, M.; Price, S.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Ruschitzka, F.; Kathrine Skibelund, A.; de Boer, R.A.; Christian Schulze, P.; Abdelhamid, M.; Aboyans, V.; Adamopoulos, S.; Anker, S.D.; Arbelo, E.; Asteggiano, R.; Bauersachs, J.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Borger, M.A.; Budts, W.; Cikes, M.; Damman, K.; Delgado, V.; Dendale, P.; Dilaveris, P.; Drexel, H.; Ezekowitz, J.; Falk, V.; Fauchier, L.; Filippatos, G.; Fraser, A.; Frey, N.; Gale, C.P.; Gustafsson, F.; Harris, J.; Iung, B.; Janssens, S.; Jessup, M.; Konradi, A.; Kotecha, D.; Lambrinou, E.; Lancellotti, P.; Landmesser, U.; Leclercq, C.; Lewis, B.S.; Leyva, F.; Linhart, A.; Løchen, M.L.; Lund, L.H.; Mancini, D.; Masip, J.; Milicic, D.; Mueller, C.; Nef, H.; Nielsen, J.C.; Neubeck, L.; Noutsias, M.; Petersen, S.E.; Sonia Petronio, A.; Ponikowski, P.; Prescott, E.; Rakisheva, A.; Richter, D.J.; Schlyakhto, E.; Seferovic, P.; Senni, M.; Sitges, M.; Sousa-Uva, M.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Touyz, R.M.; Tschoepe, C.; Waltenberger, J.; Krim, M.; Hayrapetyan, H.; Moertl, D.; Mustafayev, I.; Kurlianskaya, A.; Depauw, M.; Kušljugić, Z.; Gatzov, P.; Milicic, D.; Agathangelou, P.; Melenovský, V.; Bridal Løgstrup, B.; Magdy Mostafa, A.; Uuetoa, T.; Lassus, J.; Logeart, D.; Kipiani, Z.; Bauersachs, J.; Chrysohoou, C.; Sepp, R.; Jóna Ingimarsdóttir, I.; O’Neill, J.; Gotsman, I.; Iacoviello, M.; Rakisheva, A.; Bajraktari, G.; Lunegova, O.; Kamzola, G.; Abdel Massih, T.; Benlamin, H.; Žaliaduonytė, D.; Noppe, S.; Moore, A.; Vataman, E.; Boskovic, A.; Bennis, A.; Manintveld, O.C.; Srbinovska Kostovska, E.; Gulati, G.; Straburzyńska-Migaj, E.; Silva-Cardoso, J.; Cristina Rimbaş, R.; Lopatin, Y.; Foscoli, M.; Stojkovic, S.; Goncalvesova, E.; Fras, Z.; Segovia, J.; Lindmark, K.; Maeder, M.T.; Bsata, W.; Abid, L.; Altay, H.; Voronkov, L.; Davies, C.; Abdullaev, T. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauersachs, J. Heart failure drug treatment: the fantastic four. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; Fang, J.C.; Fedson, S.E.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hayek, S.S.; Hernandez, A.F.; Khazanie, P.; Kittleson, M.M.; Lee, C.S.; Link, M.S.; Milano, C.A.; Nnacheta, L.C.; Sandhu, A.T.; Stevenson, L.W.; Vardeny, O.; Vest, A.R.; Yancy, C.W. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, e876–e894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gongwang, L. Clinical Acupuncture & Moxibustion; Huaxia Publishing House: Tiennjin, China; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Vukomanović, A.; Djurović, A.; Popović, Z.; Ilić, D. The A-test--reliability of functional recovery assessment during early rehabilitation of patients in an orthopedic ward. Vojnosanit Pregl 2014, 71, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukomanović, A.; Đurović, A.; Brdareski, Z. Diagnostic accuracy of the A-test and cutoff points for assessing outcomes and planning acute and post-acute rehabilitation of patients surgically treated for hip fractures and osteoarthritis. Vojnosanit Pregl 2016, 73, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vukomanović, A.; Djurović, A.; Popović, Z.; Pejović, V. The A-test: assessment of functional recovery during early rehabilitation of patients in an orthopedic ward--content, criterion and construct validity. Vojnosanit Pregl 2014, 71, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic-Kostic, I. Verovatnoca i statistika; Univerzitet Singidunum: Belgrade, Serbia, 2015; pp. 134–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Size Calculator by Raosoft, Inc. Available online: http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html.

- Sakpal, T.V. Sample size estimation in clinical trial. Perspect Clin Res 2010, 1, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimo, A.; Barison, A.; Mammini, C.; Emdin, M. The Barthel Index in elderly acute heart failure patients. Frailty matters. Int J Cardiol 2018, 254, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoki, H.; Nishimura, M.; Kanai, M.; Kimura, K.; Minamisawa, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Saigusa, T.; Ebisawa, S.; Okada, A.; Kuwahara, K. Impact of inpatient cardiac rehabilitation on Barthel Index score and prognosis in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2019, 293, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katano, S.; Yano, T.; Ohori, K.; Kouzu, H.; Nagaoka, R.; Honma, S.; Shimomura, K.; Inoue, T.; Takamura, Y.; Ishigo, T.; Watanabe, A.; Koyama, M.; Nagano, N.; Fujito, T.; Nishikawa, R.; Ohwada, W.; Hashimoto, A.; Katayose, M.; Ishiai, S.; Miura, T. Barthel Index Score Predicts Mortality in Elderly Heart Failure—A Goal of Comprehensive Cardiac Rehabilitation. Circ J 2021, 86, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, M.; Lee, H.; Kostanjsek, N.; Fornari, A.; Raggi, A.; Martinuzzi, A.; Yáñez, M.; Almborg, A.H.; Fresk, M.; Besstrashnova, Y.; Shoshmin, A.; Castro, S.S.; Cordeiro, E.S.; Cuenot, M.; Haas, C.; Maart, S.; Maribo, T.; Miller, J.; Mukaino, M.; Snyman, S.; Trinks, U.; Anttila, H.; Paltamaa, J.; Saleeby, P.; Frattura, L.; Madden, R.; Sykes, C.; Gool, C.H.V.; Hrkal, J.; Zvolský, M.; Sládková, P.; Vikdal, M.; Harðardóttir, G.A.; Foubert, J.; Jakob, R.; Coenen, M.; Kraus de Camargo, O. 20 Years of ICF-International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: Uses and Applications around the World. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 11321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzoska, C. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) in daily clinical practice: Structure, benefits and limitations. Eur Psychiatry 2021, 64, S63–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, A.L.L.; Santos, L.A.; Oliveira, L.; Almeida, A.C.; Alves, D.; Silva, H.B.M.M.; Souza, F.F.; Guimarães, A.R.F. Feasibility of the Two-Minute Walk Test in Elderly Patients After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Cardiovasc Sci 2024, 37, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J.M.; Hannequin, A.; Besson, D.; Benaïm, S.; Krawcow, C.; Laurent, Y.; Gremeaux, V. Walking tests during the exercise training: specific use for the cardiac rehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2013, 56, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.; Parsons, J.; Tran, D.; Jeng, B.; Gorczyca, B.; Newton, J.; Lo, V.; Dear, C.; Silaj, E.; Hawn, T. The two-minute walk test as a measure of functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Wang, Y.C.; Gershon, R.C. Two-minute walk test performance by adults 18 to 85 years: normative values, reliability, and responsiveness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015, 96, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzoletti, L.; Zanolin, M.E.; Dorelli, G.; Ferrari, P.; Dalle Carbonare, L.G.; Crisafulli, E.; Alemayohu, M.A.; Olivieri, M.; Verlato, G.; Ferrari, M. Six-minute walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from a general population sample. Respir Res 2022, 23, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, C.; Celli, B.R.; Barria, P.; Casas, A.; Cote, C.; de Torres, J.P.; Jardim, J.; Lopez, M.V.; Marin, J.M.; Montes de Oca, M.; Pinto-Plata, V.; Aguirre-Jaime, A.; Abraham, A.; Aguiar, P.; Carrizo, S.; Dordelly, L.; Lakuntza, M.M.; Lisboa, C.; Mamchur, M.; Sifonte, M.; Tuffanin, A.T. The 6-min walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from seven countries. Eur Respir J 2011, 37, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristen, A.V.; Schuhmacher, B.; Strych, K.; Lossnitzer, D.; Friederich, H.C.; Hilbel, T.; Haass, M.; Katus, H.A.; Schneider, A.; Streitberger, K.M.; Backs, J. Acupuncture improves exercise tolerance of patients with heart failure: a placebo-controlled pilot study. Heart 2010, 96, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.A.; Meyer, T.; Butterfield, J.; Passino, C.; Gabriella, M.; Sarullo, F.; Jonsdottir, S.; Wisloff, U.; Giallauria, F. The Effects of Exercise Training on Systemic Brain Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) and N-terminal BNP Expression in Heart Failure Patients: An Individual Patient Meta-analysis. Originally published 23 Mar 2018. Circulation 2010, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Kim, T.H.; Leem, J. Acupuncture for heart failure: A systematic review of clinical studies. Int J Cardiol 2016, 222, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, G.R.; Whellan, D.J.; O’Connor, C.M.; Duncan, P.; Eggebeen, J.D.; Morgan, T.M.; Hewston, L.A.; Pastva, A.; Patel, M.J.; Kitzman, D.W. A Novel Rehabilitation Intervention for Older Patients With Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: The REHAB-HF Pilot Study. JACC Heart Fail 2017, 5, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Zhengfen, Z.; Xiaohong, Z. The intervention effect of transitional rehabilitation training on the clinical outcome of elderly patients with ADHF based on physical function evaluation. Chinese Journal of Practical Nursing 2021, 37, 1628–1634. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).