Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are prevalent in men of all ages and represent a challenge for diagnosing the underlying etiology. [

1] Previous studies have revealed that bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is only present in one third of men with LUTS. [

2] The pathophysiology of BOO in men involves both anatomical and functional disorders, such as benign prostatic obstruction (BPO), bladder neck dysfunction (BND), dysfunctional voiding (DV), poor relaxation of external sphincter (PRES), and urethral stricture. [

2,

3,

4] Additionally, in men with LUTS, common lower urinary tract dysfunctions (LUTDs) include hypersensitive bladder, detrusor overactivity (DO), and detrusor underactivity (DU), even after medical or surgical management of BOO. [

2,

5,

6] A differential diagnosis based on symptoms alone is unreliable; however, adding larger prostatic volume and lower maximum flow rate to form a nomogram may increase the accuracy of BOO diagnoses in men. [

7]

Determining the subtypes of LUTDs associated with BOO in men is pivotal for choosing the optimal medication and correct management. [

8] Previous studies on men with LUTS have revealed that LUTS alone cannot provide accurate diagnoses of LUTDs. [

9] Videourodynamic studies (VUDS) enable a more precise and comprehensive examination of bladder and bladder outlet conditions in both the storage and emptying phases. [

2] VUDS record real-time data of pressure–flow studies and concomitant fluoroscopic imaging during both the storage and emptying phases of the bladder, thereby providing an understanding of the underlying anatomical dysfunction in LUTD patients. [

10] However, VUDS has disadvantages, such as invasiveness and complicated protocols. Thus, VUDS is not routinely used for LUTS patients but is only employed when initial medication has failed to resolve LUTS or invasive surgery is planned. [

11]

First-line examinations of LUTDs in men with LUTS include the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), voiding-to-storage (V/S) ratio, prostatic parameters, uroflowmetry parameters, and prostate-specific antigens, which are mainly used to diagnose BPO. [

12] Cystoscopy or urodynamic studies are usually performed when the treatment based on the initial diagnosis is not effective. Combinations of several office-based examinations that achieve an accurate diagnosis of BPO have been reported. [

7,

13]

To the best of our knowledge, no study to date has developed prediction models using VUDS as the final diagnostic standard, especially for men with suspected medication-refractory BOO. This study investigated the predictive values of BOO risk scores in diagnosing BPO, BND, and other LUTDs in men with LUTS. The results of this study can provide a reference for clinicians to select the appropriate medication and management for BPO in male patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

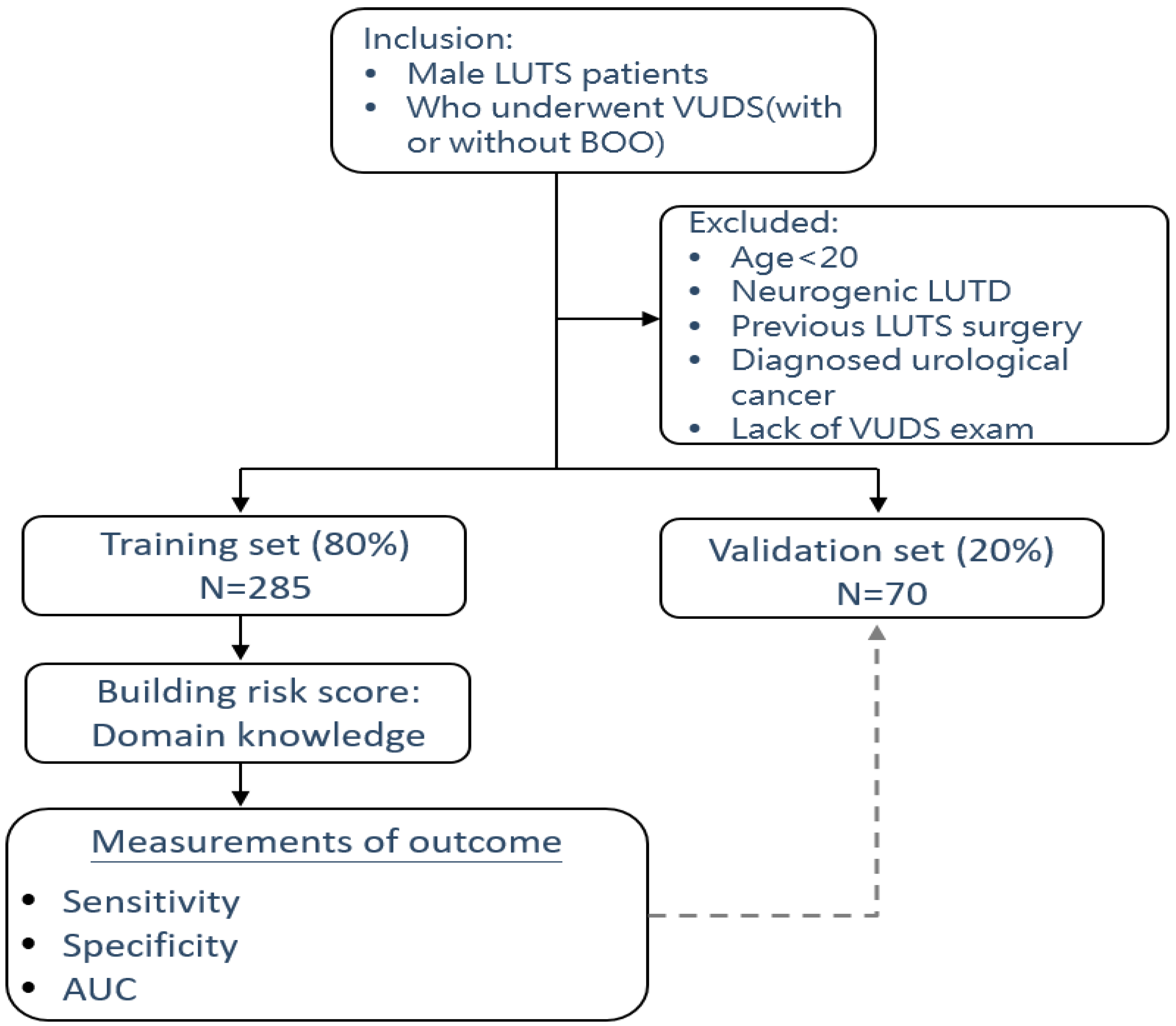

Figure 1 shows the study flow chart for the development of a predictive model for BOO, including initial patient selection based on inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the development and test validation of the algorithm.

This retrospective study included a cohort of male patients with medication-refractory, nonneurogenic LUTS and suspected BOO. All patients underwent VUDS before enrollment at a single medical center from January 2016 to March 2023. The inclusion criteria included men who had been on continuous medication, e.g., alpha-blockers for voiding LUTS and antimuscarinics for storage LUTS, for more than 3 months without a satisfactory response. Exclusion criteria included patients that were under 20 years of age, presented with overt neurogenic LUTDs, had previous lower urinary tract surgery, had any history of urological malignancy, or lacked interpretable VUDS records. This study was approved by the Institution Review Board of the hospital (IRB 111-132-B). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the analysis. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki from 2013.

Noninvasive Examinations and VUDS

For all male LUTS patients, we routinely recorded the following: their history, physical examinations, digital rectal examination of the prostate, IPSS subscores, V/S ratio, serum prostate-specific antigen levels, and transrectal ultrasound of the prostate along with uroflowmetry. The noninvasive clinical parameters used to construct the predictive model were derived from these office examinations. The parameters were categorized as 0, 1, 2, or 3, according to their cutoff values of the specificity of predicting BOO. The BOO risk score was constructed by summing scores of seven variables of symptoms, prostate parameters, and uroflowmetry parameters. The measured parameters included maximum flow rate (Qmax), voided volume, and postvoid residual (PVR) volume. IPSS subscores included IPSS-voiding, IPSS-storage, and IPSS-V/S ratio. [

14] Transrectal ultrasound of the prostate measurements included total prostate volume (TPV), transitional zone index (TZI, defined as the percentage of transitional zone volume to TPV), intravesical prostatic protrusion (IPP, measured in cm), and prostatic urethrovesical (PUV) angle (measured in degrees). [

15]

VUDS was performed on patients in the standing position, as previously reported. [

16] The VUDS parameters included the first sensation of bladder filling, full sensation, urge sensation, bladder compliance, voiding detrusor pressure at Qmax (Pdet.Qmax), Qmax, corrected Qmax (cQmax, defined as Qmax divided by the square root of the bladder volume), voided volume, PVR (measured using bladder sonography), and BOO index. All descriptions and terminologies used in the VUDS were in accordance with the recommendations of the International Continence Society. [

17,

18]

DO was defined as urodynamic evidence of spontaneous detrusor contractions occurring during bladder filling or before uninhibited detrusor contraction voiding upon reaching bladder capacity. DU was defined as having a voiding detrusor contractility of <10 cmH

2O, having the need to void by abdominal straining, or being unable to void. DO with DU (DO-DU) was defined as DO associated with incomplete bladder emptying and a PVR of >100 mL. [

18] BOO was defined as having radiographic evidence of narrowing in voiding cystourethrography at the bladder neck (defined as BND), prostatic urethra (defined as BPO), urethral sphincter, or distal urethra (defined as urethral stricture), with a sustained detrusor contraction of high or low magnitude. [

5,

8,

19] The diagnosis of BND was made based on a narrow bladder neck and open prostatic urethra during voiding with or without an elevated Pdet during voiding. [

20] BPO was diagnosed when the prostatic urethra remained narrow with or without a narrow bladder neck and Pdet was elevated during voiding. [

2,

21] Patients were diagnosed with PRES without true BOO when they exhibited a low Pdet.Qmax, low Qmax, an open bladder neck and prostatic urethra, and a narrow urethral sphincter in the VUDS. [

22] Patients without VUDS-determined BOO were considered non-BOO. All VUDS reports were collected and reviewed by a single urology professor to ensure consistency and reliability in the interpretation of these complex studies.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

Several outcome measures were used to evaluate the effectiveness of our predictive models. Discrimination (the model’s ability to distinguish between the presence and absence of an outcome) was measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The AUC provides a single measurement summarizing the model’s accuracy across all classification thresholds.

Categorical variables are presented as the number of patients (proportion), and continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software for Windows (version 25.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Optimal BOO risk scores for diagnosing BPO, BND, and other LUTDs were identified from the receiver operating characteristic curves using Youden methods. The sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing BOO with the proposed BOO risk scores were also examined in patients with VUDS-determined BPO, BND, or other LUTDs.

Results

Patient Characteristics and VUDS Diagnosis

This cohort included 355 male patients presenting with medication-refractory LUTS and suspected BOO, all of which underwent VUDS before enrollment. Patients with a TPV of >60 mL and acute or chronic urinary retention were not included in this study. The cohort was divided into a training set (n = 285) and a validation set (n = 70). The mean age of the entire cohort was 67.8 ± 9.5 years, which did not significantly differ between the training and validation sets (P = 0.464). Comparisons of the training and validation sets revealed no significant differences in the following clinical parameters: IPSS-voiding, IPSS-storage, IPSS-V/S ratio, Qmax, voided volume, PVR, TPV, TZI, IPP, and PUV angle (

Table 1).

The VUDS diagnoses revealed obstruction-predominant conditions, with BND accounting for 38.3% (n = 136), BPO for 27.6% (n = 98), DV for 7.9% (n = 28), and PRES for 7.3% (n = 26) of cases. Regarding bladder dysfunction, DU without BOO was present in 3.9% (n = 14), DO without BOO in 10.4% (n = 37), hypersensitive bladder in 2% (n = 7), and a normal bladder in 2.5% (n = 9) of cases. The distributions of these LUTDs were similar between the training and validation sets. (

Table 2).

Table 3 shows the clinical symptoms and uroflowmetry and prostate parameters of patients with and without BOO. BOO patients exhibited significantly older age, lower Qmax values, and higher values of TPV, TZI, IPP, and PUV angles.

Based on the sensitivity and specificity of each single variable for BOO, a clinical BOO risk scoring system was established, using the measured parameters obtained from noninvasive examinations, including age, IPSS-V/S, uroflowmetry parameters (Qmax and voided volume), and prostate parameters (TPV, TZI, IPP, and PUV angle). The variables were categorized as 0, 1, 2,3 according to their cutoff values in predicting BOO (

Table 4).

Table 5 shows the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the training and validation sets of patients using the BOO risk score. The predictive model showed that for a BOO risk score of ≥10, the sensitivity and specificity for BPO were 82.2% and 65.6%, respectively, in the training set and 80.0% and 64.0%, respectively, in the validation set. The AUC was 0.800 (confidence interval: 0.741–0.859) for the training set and 0.813 (confidence interval: 0.701–0.925) for the diagnosis of BPO by a BOO risk score of ≥10. The diagnostic accuracy of the other variables was lower than 0.700 using the BOO risk score system. Based on these results, a BOO risk score of ≥10 can predict the presence of BPO in >80% of men with LUTS.

Discussion

This study established a BOO risk score system based on office-based examinations, including IPSS, uroflowmetry, and prostate parameters. A BOO risk score of ≥10 can predict the presence of BPO in >80% of men with LUTS. However, patients with a BOO risk score of <10 may need comprehensive VUDS to identify the LUTD subtype. This study highlights the use of VUDS to identify LUTDs in men. Most previous studies only used pressure–flow studies as the standard method for assessing BOO. [

7,

23] Using the BOO risk score, a predictive model based on office-obtained parameters can be established.

Previous research on factors for predicting BOO in men with LUTS has yielded variable results. Chia et al. reported that the diagnostic accuracy for an IPP of >10 mm had a specificity of 92%, which was similar to the result using a Qmax of <10 mL/s for free-flow rate testing. [

24] Cicione et al. presented a multivariable logistic age-adjusted regression model, which revealed that bladder wall thickness, PVR, and TPV were significant predictors for BOO. The model had an accuracy of 0.82 and a clinical net benefit of 10%–90%. [

25] However, the diagnosis of BOO was based on pressure–flow studies and not VUDS.

Several noninvasive techniques have also been developed for the assessment of BOO in men with LUTS. From the evidence reviewed by Malde et al., penile cuff tests have a sensitivity of 88.9% and specificity of 75.7%, with positive and negative predictive values of 67.7% and 93.0%, respectively. [

26] Detrusor wall thickness and IPP by suprapubic ultrasound have a high predictive value for BPO in men. [

27] Near-infrared spectroscopy can identify men with BOO with a

sensitivity of 68.3%, specificity of 62.5%, and average diagnosis coincidence rate of 66.7%, compared with the gold standard—the Abrams-Griffiths number. [

28] These studies all showed high diagnostic accuracy for BOO in men. However, the diagnoses of BOO and BPO in these studies were not based on VUDS, and thus may have resulted in bias regarding the final definition of BOO.

Most likely, no single test is universally suitable to diagnose all patients with LUTS and suspected BOO. All simple tests other than VUDS have exhibited only limited diagnostic accuracy for BOO, and no single test can definitively identify BND or BPO. [

29] Urination is a dynamic process involving bladder contractions and bladder outlet relaxation, static measurement of the TPV, TZI, or PUV angle might not accurately reflect the voiding condition during urination. [

2,

5,

10] Therefore, it is necessary to combine several parameters from simple tests to achieve satisfactory diagnostic accuracy that is similar to that obtained using VUDS. Kuo has proposed a clinical prostate score in patients with LUTS suggestive of BPH. Parameters with a positive prediction of LUTS due to BPH were scored +1 or +2, whereas those with a negative prediction were scored −1 or 0. The sensitivity and specificity of BPO diagnoses in patients with at least one favorable predictive factor with a total score of ≥3 were 91.6% and 87.3%, respectively. [

30] However, in that study, the author did not divide BOO into BPO and BND. Although a larger TPV indicates higher incidence of BPO in male patients with LUTS, patients with LUTS and BOO might also result from BND or PRES, especially in patients with a TPV of <40 mL. Our current study did not include patients with a TPV of >60 mL and acute or chronic urinary retention. Therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of BPO were lower than those in the previous study [

30]. However, we used VUDS to identify BND, PRES, and other LUTDs, and the results of this study reflect real-life practices in diagnosing BPO.

This study investigated patients with voiding LUTS and moderately enlarged prostate who were refractory to initial medical treatment. Although all patients had LUTS, the LUTDs varied widely and included BOO and bladder dysfunction. These results reveal that LUTS in men cannot be reliably diagnosed with a single test, and thus combining parameters from several noninvasive tests may have a more accurate predictive value. [

9,

29] However, using numerous variables to create a scoring system for predicting BOO may not result in a high predictive value because BOO (diagnosed with VUDS) may be accompanied with BPO, BND, DV, and possible PRES. In this study, the scoring system to predict BPO was satisfactory; approximately 80% of BPO patients could be identified with a BOO risk score of ≥10. However, the specificity was 65%, which is not sufficient for a clinically useful scoring system for predicting BPO for invasive treatment. The results of this study indicate that an accurate diagnosis of BOO subtypes in men cannot rely on a single office-based examination. When the diagnosis of BPO is not definite, VUDS may be necessary to avoid incorrect diagnosis or overtreatment. [

2,

16]

This study has collected several noninvasive parameters obtained from office-based examinations that show promise for assessing BPO in men with LUTS suggestive of BOO. However, several limitations should be reported. First, this is a retrospective analysis, which introduces a potential selection bias due to the inclusion of only those patients who had LUTS refractory to the initial medical treatment and the exclusion of patients with a large TPV, urinary retention, and incomplete data. Second, the study used data from only one medical center, which might limit the generalizability of the findings. For further validation, multicenter data should be pooled together to enhance the robustness of our predictive model. Furthermore, our developed model might not be suitable for patients who require initial diagnoses of LUTDs.

Conclusions

With office-based urological examinations, including IPSS, uroflowmetry, and prostate measurements, a BOO risk score can be established. A BOO risk score of ≥10 can predict the presence of BPO in >80% of men with LUTS. This study demonstrated the accuracy of predicting BPO in men with LUTS, which can be used to guide subsequent treatment or invasive examinations. However, for patients with a BOO risk score of <10, VUDS is still needed for an accurate diagnosis of BND, PRES, or other LUTDs in men with LUTS refractory to initial medical treatment.

References

- Malde S, Umbach R, Wheeler JR, Lytvyn L, Cornu JN, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Mamoulakis C, Rieken M, Speakman MJ, Gravas S, Drake MJ, Guyatt GH, Tikkinen KAO. A Systematic Review of Patients' Values, Preferences, and Expectations for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol. 2021, 79, 796–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.C. Videourodynamic analysis of pathophysiology of men with both storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology 2007, 70, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.T. Pathophysiology of clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J Urol. 2017, 4, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, R.D.; Drain, A.; Brucker, B.M. Primary bladder neck obstruction. Rev Urol. 2019, 21, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.H.; Liao, C.H.; Kuo, H.C. Role of Bladder Dysfunction in Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Refractory to Alpha-blocker Therapy: A Video-urodynamic Analysis. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 2018, 10, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarcan T, Hashim H, Malde S, Sinha S, Sahai A, Acar O, Selai C, Agro EF, Abrams P, Wein A. Can we predict and manage persistent storage and voiding LUTS following bladder outflow resistance reduction surgery in men? ICI-RS 2023. Neurourol Urodyn 2024, 43, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee YJ, Lee JK, Kim JJ, Lee HM, Oh JJ, Lee S, Lee SW, Kim JH, Jeong SJ. Development and validation of a clinical nomogram predicting bladder outlet obstruction via routine clinical parameters in men with refractory nonneurogenic lower urinary tract symptoms. Asian J Androl. 2019, 21, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen JL, Jiang YH, Lee CL, Kuo HC. Precision medicine in the diagnosis and treatment of male lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tzu Chi Med J. 2019, 21, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, H.C. Clinical symptoms are not reliable in the diagnosis of lower urinary tract dysfunction in women. J Formos Med Assoc 2012, 111, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang YH, Chen SF, Kuo HC. Role of videourodynamic study in precision diagnosis and treatment for lower urinary tract dysfunction. Tzu Chi Med J. 2019, 32, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gravas S, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Herrmann TRW, Karavitakis M, Kyriazis I, Malde S, Mamoulakis C, Rieken M, Sakalis VI, Schouten N, Speakman MJ, Tikkinen KAO, Cornu JN. Summary Paper on the 2023 European Association of Urology Guidelines on the Management of Non-neurogenic Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol. 2023, 84, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner LB, McVary KT, Barry MJ, Bixler BR, Dahm P, Das AK, Gandhi MC, Kaplan SA, Kohler TS, Martin L, Parsons JK, Roehrborn CG, Stoffel JT, Welliver C, Wilt TJ. Management of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Attributed to Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: AUA GUIDELINE PART I-Initial Work-up and Medical Management. J Urol. 2021, 206, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt MD, van Venrooij GE, Boon TA. Symptoms, prostate volume, and urodynamic findings in elderly male volunteers without and with LUTS and in patients with LUTS suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology 2001, 58, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang YH, Lin VC, Liao CH, Kuo HC. International Prostatic Symptom Score-voiding/storage subscore ratio in association with total prostatic volume and maximum flow rate is diagnostic of bladder outlet-related lower urinary tract dysfunction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Chen Z, Zeng R, Huang J, Zhuo Y, Wang Y. Bladder Neck Angle Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Urinary Flow Rate in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Urology 2021, 158, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang YH, Wang CC, Kuo HC. Videourodynamic findings of lower urinary tract dysfunctions in men with persistent storage lower urinary tract symptoms after medical treatment. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0190704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewski JB, Schurch B, Hamid R, Averbeck M, Sakakibara R, Agrò EF, Dickinson T, Payne CK, Drake MJ, Haylen BT. An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (ANLUTD). . ;37:-1161. Neurourol Urodyn 2018, 37, 1152–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ancona C, Haylen B, Oelke M, Abranches-Monteiro L, Arnold E, Goldman H, Hamid R, Homma Y, Marcelissen T, Rademakers K, Schizas A, Singla A, Soto I, Tse V, de Wachter S, Herschorn S; Standardisation Steering Committee ICS and the ICS Working Group on Terminology for Male Lower Urinary Tract; Pelvic Floor Symptoms and Dysfunction. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn 2019, 38, 433–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitti VW, Lefkowitz G, Ficazzola M, Dixon CM. Lower urinary tract symptoms in young men: videourodynamic findings and correlation with noninvasive measures. J Urol. 2002, 168, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan P, Nitti VW. Primary bladder neck obstruction in men, women, and children. Sep;(5):-84. Curr Urol Rep. 2007, 8, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke QS, Jiang YH, Kuo HC. Role of Bladder Neck and Urethral Sphincter Dysfunction in Men with Persistent bothersome Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms after alpha-1 Blocker Treatment. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 2015, 7, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao IH, Kuo HC. Role of poor urethral sphincter relaxation in men with voiding dysfunction refractory to alpha-blocker therapy: Clinical characteristics and predictive factors. Low Urin Tract Symptoms 2019, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganpule AP, Batra RS, Shete NB, Singh AG, Sabnis RB, Desai MR. BPH nomogram using IPSS, prostate volume, peak flow rate, PSA and median lobe protrusion for predicting the need for intervention: development and internal validation. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2021, 9, 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chia SJ, Heng CT, Chan SP, Foo KT. Correlation of intravesical prostatic protrusion with bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int 2003, 91, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicione A, Lombardo R, Nacchia A, Turchi B, Gallo G, Zammitti F, Ghezzo N, Guidotti A, Franco A, Rovesti LM, Gravina C, Mancini E, Riolo S, Pastore A, Tema G, Carter S, Vicentini C, Tubaro A, De Nunzio C. Post-voided residual urine ratio as a predictor of bladder outlet obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms: development of a clinical nomogram. World J Urol. 2023, 41, 521–527. [Google Scholar]

- Malde S, Nambiar AK, Umbach R, Lam TB, Bach T, Bachmann A, Drake MJ, Gacci M, Gratzke C, Madersbacher S, Mamoulakis C, Tikkinen KAO, Gravas S; European Association of Urology Non-neurogenic Male LUTS Guidelines Panel. Systematic Review of the Performance of Noninvasive Tests in Diagnosing Bladder Outlet Obstruction in Men with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms. Eur Urol. 2017, 71, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco G, De Nunzio C, Leonardo C, Tubaro A, Ciccariello M, De Dominicis C, Miano L, Laurenti C. Ultrasound assessment of intravesical prostatic protrusion and detrusor wall thickness--new standards for noninvasive bladder outlet obstruction diagnosis? FJ Urol. 2010, 183, 2270–2274. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Yang Y, Wu ZJ, Zhang CH, Zhang XD. Diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction in men using a near-infrared spectroscopy instrument as the noninvasive monitor for bladder function. Urology 2013, 82, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Silva KA, Dahm P, Wong CL. Does this man with lower urinary tract symptoms have bladder outlet obstruction?: The Rational Clinical Examination: a systematic review. JAMA 2014, 312, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.C. Clinical prostate score for diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction by prostate measurements and uroflowmetry. Urology 1999, 54, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).